Automating Restart Procedures for Failed Geometry Optimizations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to automatic restart procedures for failed geometry optimizations in computational chemistry.

Automating Restart Procedures for Failed Geometry Optimizations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to automatic restart procedures for failed geometry optimizations in computational chemistry. Covering both theoretical foundations and practical implementations, we explore how automated restart protocols can rescue stalled calculations, improve computational efficiency, and enhance research productivity for scientists in drug development and materials research. The content addresses key methodologies across popular computational packages, troubleshooting common failure scenarios, validation techniques for restarted calculations, and comparative analysis of restart strategies—enabling researchers to implement robust, automated workflows that minimize manual intervention and computational waste.

Understanding Geometry Optimization Failures and the Restart Imperative

Common Failure Modes in Geometry Optimization Calculations

## Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why does my geometry optimization not converge? Non-convergence can stem from several issues. If the energy changes consistently in one direction over many iterations, your starting geometry may simply be far from the minimum, and you likely need to increase the maximum number of iterations and restart from the latest geometry [1]. If the energy oscillates or the gradients stop improving, the problem is often related to the accuracy of the calculated forces or instabilities in the electronic structure [1].

2. My optimization converged to a saddle point. What should I do? Some modern computational packages offer automatic restart procedures for this scenario. If your optimization converges to a transition state (a saddle point), you can configure it to automatically distort the geometry along the lowest frequency mode (which is imaginary for a transition state) and restart the optimization. This typically requires enabling PES point characterization and setting a maximum number of restarts [2].

3. How can I restart a failed geometry optimization?

The correct method depends on your software. A common and robust approach is to use the final coordinates from the previous job as the starting point for a new calculation [3]. Critically, you must use the correct keyword in your input file; using restart instead of start is often essential to prevent the program from wiping the previous results [4]. For some programs, this involves specifying a dedicated Restart keyword and ensuring necessary files (like read-write files or checkpoint files) are preserved [5].

4. I am getting unreasonably short bond lengths. What is wrong? This is a classic symptom of basis set problems, particularly when using Pauli relativistic methods. The issue can be a "variational collapse" or problems related to the frozen core approximation becoming invalid as atomic cores overlap. The recommended solution is to switch from the Pauli method to the ZORA relativistic approach [1].

## Troubleshooting Guide

### Diagnosing and Resolving Common Failures

The table below summarizes frequent issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Failure Mode | Symptoms | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Convergence [1] | Energy oscillates or fails to meet criteria after many cycles. | Inaccurate forces (gradients), small HOMO-LUMO gap, electronic state changes, or optimizer stuck. | Tighten SCF convergence, improve numerical quality (e.g., NumericalQuality Good), use ExactDensity, check for correct spin state, switch to delocalized internal coordinates [1]. |

| Convergence to Saddle Point [2] | Optimization meets stopping criteria, but frequency calculation reveals imaginary modes. | Optimization algorithm converged to a transition state instead of a minimum. | Use automatic restart with PES point characterization (PESPointCharacter True and MaxRestarts > 0), distort geometry along imaginary mode [2]. |

| Unphysical Short Bonds [1] | Optimized bond lengths are significantly too short. | Basis set error, often "Pauli variational collapse," or large frozen cores overlapping. | Use ZORA relativistic method instead of Pauli; if using Pauli, increase frozen core size or reduce basis set flexibility [1]. |

| Unstable Restart [6] | Restarting from a previously converged geometry leads to many more optimization cycles and a different final energy. | Inconsistent electronic state; the new calculation converged to a different electronic state than the original. | Restart from previous wavefunction, not just the geometry. For DFT+U systems, manually check different spin states and orbital occupations [6]. |

| Problematic Angles [1] | Optimization becomes unstable when angles approach 180 degrees. | Special treatment for linear angles is not activated if the angle started far from 180° and evolved during optimization. | Restart optimization from the latest geometry. As a last resort, constrain the angle close to, but not equal to, 180 degrees [1]. |

### Experimental Protocols for Recovery

Protocol 1: Increasing Numerical Accuracy for Convergence If your optimization oscillates or fails to converge due to noisy gradients, follow this protocol to increase the numerical accuracy in an ADF calculation [1]:

- Set the

NumericalQualitytoGood. - In the

SCFblock, tighten the convergence criteria, e.g.,converge 1e-8. - (Optional but effective) Add the

ExactDensitykeyword or select "Exact" for the density in the XC-potential. Note this will significantly increase computation time. - Use a high-quality basis set like TZ2P.

Example input block:

Protocol 2: Implementing an Automatic Restart in AMS To configure an AMS calculation to automatically restart if a saddle point is found [2]:

- Disable symmetry using

UseSymmetry False. - In the

Propertiesblock, enable PES point characterization withPESPointCharacter True. - In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, set the maximum number of restarts (e.g.,MaxRestarts 5).

Example input configuration:

Protocol 3: Manual Restart Using Final Geometry (ORCA) For a failed optimization in ORCA, the most straightforward method is to start a new job from the last known coordinates [3]:

- Locate the final coordinates from the output file by searching for "CARTESIAN COORDINATES" from the bottom of the file, or find the generated

.xyzfile. - Use these coordinates in the input file for a new optimization calculation.

- (Optional) To read the orbitals from the previous job for a potentially faster SCF convergence, use the

MOREADkeyword and specify the path to the previous.gbwfile in a%moinpblock.

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and their functions for managing geometry optimizations.

| Item | Function in Geometry Optimization |

|---|---|

| Checkpoint File (.chk) | Saves critical calculation data (e.g., wavefunction, orbitals) for restarting jobs. Essential for continuing failed calculations in programs like Gaussian [5]. |

| Read-Write File (.rwf) | A large file in Gaussian holding intermediate data. Proper management (with %RWF and %NoSave) allows restarting very large jobs that exceed the capacity of the standard checkpoint file [5]. |

| Orbital File (.gbw) | In ORCA, this file contains the molecular orbitals. Using MOREAD and %moinp to read this file can provide a good initial guess for the SCF procedure in a restarted job [3]. |

| Hessian File (.hess) | Stores second derivative information. Its presence allows a restarted optimization to "remember" the curvature of the potential energy surface, leading to faster convergence. It is also mandatory for restarting numerical frequency calculations in ORCA [3]. |

| PES Point Characterization | A computational analysis that determines the nature of a located stationary point (minimum, transition state). When enabled, it can trigger automatic restarts from saddle points [2]. |

| BRD9 Degrader-3 | BRD9 Degrader-3, MF:C39H46FN5O4, MW:667.8 g/mol |

| Catadegbrutinib | Catadegbrutinib, CAS:2736508-60-2, MF:C47H54N12O4, MW:851.0 g/mol |

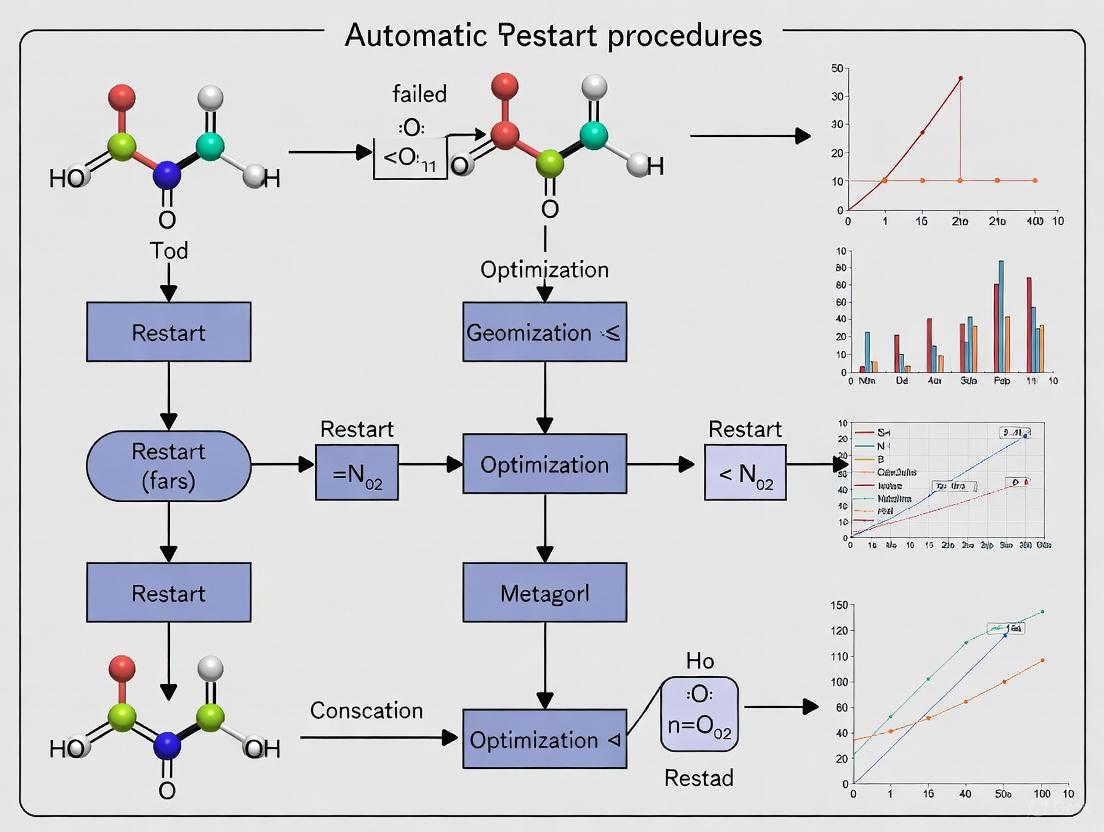

## Workflow Diagrams

### Geometry Optimization Troubleshooting Logic

### Restart Procedure Decision Guide

The Computational Cost of Failed Optimizations in Drug Discovery

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers and scientists addressing the challenge of failed geometry optimizations in computational drug discovery. The guidance below is framed within ongoing research into automatic restart procedures, designed to recover from common failures, minimize computational waste, and accelerate project timelines.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a 'failed' geometry optimization in computational chemistry?

A geometry optimization fails when the calculation does not reach a converged structure within the allowed number of iterations (MaxIterations). A converged structure is a local minimum on the potential energy surface (PES), determined by meeting specific thresholds for energy change, nuclear gradients, and step size [2]. Non-convergence wastes computational resources and halts virtual screening pipelines.

Q2: How can an optimization converge to an incorrect structure, like a transition state? Optimizations converge to the nearest stationary point on the PES from the starting geometry. If this point is a saddle point (e.g., a transition state) rather than a minimum, you have an incorrect result for ground-state drug design. This occurs because optimizers move "downhill" until forces are zero, without inherently knowing if the structure is a minimum or saddle point [2].

Q3: What are automatic restart procedures? Automatic restart procedures are algorithms that detect a failed optimization—such as convergence to a saddle point—and automatically restart the calculation from a strategically modified geometry. This is a core focus of modern research to reduce manual intervention and computational cost [2].

Q4: My optimization converged to a transition state. Can I salvage the calculation?

Yes. Enable the PESPointCharacter property to calculate the lowest Hessian eigenvalues and confirm the stationary point type. If a transition state is found, you can use automatic restarts (MaxRestarts > 0) to displace the geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode and restart the optimization [2].

Q5: Why did my optimization fail to converge even after hundreds of steps?

Extremely slow convergence often stems from overly strict convergence criteria or inaccurate gradients from the computational engine. Loosening convergence Quality settings (e.g., from VeryGood to Normal) or increasing the engine's numerical accuracy can help. It's also advisable to check if the system is near a flat or complex region of the PES [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Converged to a Saddle Point

Description The geometry optimization completes and meets convergence criteria, but frequency analysis reveals imaginary frequencies, indicating a transition state or higher-order saddle point instead of a local energy minimum. This is a common failure in drug discovery when simulating flexible molecules or complex molecular interactions.

Solution Implement an automatic restart procedure to find the nearest local minimum.

Step-by-Step Instructions

- Verify the Saddle Point: In your next calculation, enable the

PESPointCharacterproperty in thePropertiesblock to confirm the nature of the stationary point [2]. - Configure Automatic Restart: In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setMaxRestartsto a value between 3 and 5. This allows the system multiple attempts to find a minimum [2]. - Disable Symmetry: Add

UseSymmetry Falseto the input. Symmetry constraints can prevent the necessary geometry distortion to escape the saddle point [2]. - Set Displacement Size: Optionally, adjust the

RestartDisplacementkeyword (default is 0.05 Ã…) to control the magnitude of the initial push away from the saddle point [2].

Example Input Code Block

Workflow Diagram

Problem: Optimization Exceeds Maximum Number of Iterations

Description

The optimization stops before convergence because it hits the MaxIterations limit. This is computationally expensive and fails to produce a usable result.

Solution Systematically loosen convergence criteria and inspect the optimization history.

Step-by-Step Instructions

- First, check the optimization history. Plot the energy and maximum gradient versus optimization step. A slowly decreasing gradient suggests the criteria may be too strict.

- Adjust convergence quality. Set

Convergence QualitytoBasicorNormalto loosen the thresholds [2]. - Increase iteration limit cautiously. As a secondary step, you can increase

MaxIterations, but this is not a substitute for diagnosing the underlying cause [2].

Summary of Convergence Settings Table: Standard Convergence Quality Settings in AMS [2]

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Ã…) | Step (Ã…) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10â»Â³ | 10â»Â¹ | 1 |

| Basic | 10â»â´ | 10â»Â² | 0.1 |

| Normal | 10â»âµ | 10â»Â³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 10â»â¶ | 10â»â´ | 0.001 |

| VeryGood | 10â»â· | 10â»âµ | 0.0001 |

Problem: Noisy Gradients Causing Unstable Optimization

Description In certain computational methods (e.g., DFT with complex functionals or QM/MM), gradients may have numerical noise. This causes the optimizer to "bounce" around the minimum without achieving tight convergence.

Solution Ensure gradient accuracy and select a robust optimizer.

Step-by-Step Instructions

- Increase engine numerical quality. Consult your engine's documentation (e.g., in BAND, use the

NumericalQualitykeyword) to compute more accurate gradients and energies [2]. - Use a resilient optimizer. The Berny algorithm with GEDIIS is a good default. For difficult cases, the L-BFGS optimizer can be more stable with noisy gradients [7].

Table: Essential Tools for Robust Geometry Optimizations

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Specific Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| PES Point Characterization | Calculates Hessian eigenvalues to classify stationary points (minima, transition states). | Critical for validating that a proposed drug-like molecule is in a stable ground-state configuration, not a saddle point [2]. |

| Berny Optimization Algorithm | A quasi-Newton optimizer using GEDIIS and redundant internal coordinates. | The default, efficient algorithm for locating local minima and transition states in molecular systems [7]. |

| Automatic Restart Protocol | Automatically restarts failed optimizations from displaced geometries. | Core procedure for recovering from saddle point convergence without manual intervention, saving researcher time and computational cycles [2]. |

| Convergence Quality Presets | Predefined sets of thresholds (Energy, Gradient, Step) for convergence. | Allows researchers to quickly balance accuracy and computational cost during high-throughput virtual screening of compound libraries [2]. |

| ModRedundant Internal Coordinates | Allows manual definition and freezing of specific bonds, angles, or dihedrals. | Used to constrain parts of a molecule during optimization, such as freezing a protein backbone while optimizing a ligand pose [7]. |

Fundamental Principles of Restart Mechanisms Across Platforms

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does it mean for a geometry optimization to "fail" and require a restart?

A geometry optimization fails when it does not meet the predefined convergence criteria within the allowed number of steps (MaxIterations) [2]. Convergence is typically assessed based on thresholds for energy changes, nuclear gradients, and step sizes [2]. An optimization might also fail by converging to a saddle point (transition state) instead of the desired local minimum [2].

What are the main automatic restart procedures for a failed optimization? Modern computational chemistry platforms support sophisticated restart mechanisms. The two primary procedures are:

- Trajectory Restart: You can restart the optimization from the last calculated geometry and, crucially, reuse the historical force and coordinate data to continue building the Hessian matrix. This is done by specifying a

restartfile or replaying atrajectoryfile [8]. - Saddle Point Restart: If an optimization converges to a transition state, the calculation can be automatically restarted. The system is displaced along the imaginary vibrational mode, and the optimization is run again to search for a true minimum. This requires enabling

PESPointCharacterand settingMaxRestartsto a value greater than 0 [2].

My optimization is stuck. Should I just increase the maximum number of iterations?

While you can increase MaxIterations, the default is usually a large number. A failure to converge often indicates a deeper issue, such as an overly stiff potential energy surface, noisy gradients, or a poor initial geometry. It is often better to investigate the cause rather than simply increasing the iteration limit [2].

How can I ensure my restarted calculation is stable and efficient?

The key is to transfer as much information as possible from the previous run. Always use the restart functionality to save and reload the Hessian matrix. For tricky optimizations, use the KeepIntermediateResults Yes option to save all intermediate steps for detailed analysis [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Failed to Converge

This occurs when the MaxIterations limit is reached before all convergence criteria are satisfied [2].

- Diagnosis: Check the logfile for a clear warning that the optimization did not converge. The final energies and forces will likely still be fluctuating.

- Solution:

- Restart from Trajectory: The most common and effective method. Use the last geometry from the trajectory file to restart the job, allowing the optimizer to continue from where it left off.

- Example Protocol (AMS): Your new input file should use the final system from the old results file and set

Task GeometryOptimizationagain. The optimizer will automatically use the history from therestartfile if one was specified [2]. - Example Protocol (ASE): Use the

restartparameter when initializing the optimizer to reload the Hessian.

- Example Protocol (AMS): Your new input file should use the final system from the old results file and set

- Weaken Convergence Criteria: If you are close to convergence, slightly increasing the

Convergence%Energy,Convergence%Gradients, orConvergence%Stepthresholds (e.g., fromGoodtoNormal) [2] may allow the job to finish, though this results in a less precise geometry.

- Restart from Trajectory: The most common and effective method. Use the last geometry from the trajectory file to restart the job, allowing the optimizer to continue from where it left off.

Problem: Optimization Converged to a Saddle Point

The optimization finished successfully but a frequency calculation or PESPointCharacter analysis reveals one or more imaginary frequencies, indicating a transition state [2].

- Diagnosis: Enable

PESPointCharacterin thePropertiesblock. If a negative eigenvalue (imaginary frequency) is found, the optimization has found a saddle point. - Solution:

- Enable Automatic Restart: Configure the input to automatically handle this.

- Experimental Protocol (AMS):

When the optimizer detects a saddle point, it will displace the geometry by

RestartDisplacementalong the imaginary mode and restart the optimization [2].

- Experimental Protocol (AMS):

When the optimizer detects a saddle point, it will displace the geometry by

- Manual Displacement: If automatic restart is not available, manually calculate the vibrational mode, displace the geometry along the imaginary mode, and use this new geometry as the starting point for a fresh optimization.

- Enable Automatic Restart: Configure the input to automatically handle this.

Problem: Noisy Gradients or Oscillatory Behavior

This is common with certain computational methods and can prevent stable convergence.

- Diagnosis: The optimization history in the logfile or trajectory shows energies and forces that oscillate without settling into a clear minimum.

- Solution:

- Tighten Numerical Quality: In your engine settings (e.g., for ADF/BAND), increase the

NumericalQualityto obtain more precise gradients and energies [2]. - Change Optimizer: Switch to a different optimization algorithm. MDMin or FIRE can be more effective than quasi-Newton methods like BFGS for navigating rough potential energy surfaces [8].

- Use a Smoother Model: Consider whether a different basis set, functional, or convergence accelerator could provide a smoother path to the minimum.

- Tighten Numerical Quality: In your engine settings (e.g., for ADF/BAND), increase the

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standard Protocol: Restarting a Failed Geometry Optimization

This protocol details how to restart a geometry optimization from a previous calculation using the ASE package [8].

- Initial Setup: Begin with your initial

atomsobject and a chosen calculator (e.g., EMT, GPAW). - Initial Optimization Run: Start the optimizer, specifying both a

trajectoryand arestartfile. - Diagnosis of Failure: If the job fails or is stopped, check the last entry in

optimization.traj. - Restart:

- Read the last system state:

atoms = read('optimization.traj', index=-1) - The calculator state must be restored onto the atoms.

- Re-initialize the optimizer with the

restartfile. TheBFGSobject will read the saved Hessian frombfgs_restart.pckl.

- Read the last system state:

Advanced Protocol: Automatic Saddle Point Restart

This protocol uses the AMS platform to automatically detect a saddle point and restart the optimization [2].

- Configuration: In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setMaxRestartsto a positive integer and ensureUseSymmetryisFalseif the system has no symmetry. - Enable Characterization: In the

Propertiesblock, setPESPointCharactertoYes. - Execution: Run the job. Upon completion, the program will check the nature of the stationary point.

- Automatic Action: If a saddle point is identified, the geometry is distorted, and the optimization is restarted. This process repeats until a minimum is found or the maximum number of restarts is exceeded.

Quantitative Data: Convergence Quality Settings

The table below summarizes the standard convergence criteria in the AMS software, which can be set via the Convergence%Quality keyword [2]. These define the strictness of the convergence thresholds.

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Ã…) | Step (Ã…) | Stress/Atom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10â»Â³ | 10â»Â¹ | 1 | 5×10â»Â² |

| Basic | 10â»â´ | 10â»Â² | 0.1 | 5×10â»Â³ |

| Normal | 10â»âµ | 10â»Â³ | 0.01 | 5×10â»â´ |

| Good | 10â»â¶ | 10â»â´ | 0.001 | 5×10â»âµ |

| VeryGood | 10â»â· | 10â»âµ | 0.0001 | 5×10â»â¶ |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Software Tools

| Item/Module Name | Function in Restart Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| AMS GeometryOptimizer | Implements advanced restart logic, including saddle point characterization and automatic displacement via PESPointCharacter and MaxRestarts [2]. |

| ASE Optimizers | Provides a unified interface for optimizers (BFGS, FIRE, etc.) with core restart functionality via restart and trajectory parameters [8]. |

| ASE Trajectory Module | Handles reading and writing of optimization history, enabling manual restart and analysis of intermediate geometries and energies [8]. |

| SIMPATY Algorithm | An optimization algorithm that combines topology optimization with anisotropic mesh adaptation, useful for complex free-form structure design [9]. |

Workflow Visualization

Geometry Optimization Restart Logic

Researcher's Troubleshooting Decision Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary criteria for determining if a geometry optimization has converged? Geometry optimization is considered converged when specific thresholds for energy changes, gradient magnitudes, and coordinate step sizes are simultaneously met. Typically, this requires the change in total energy between optimization cycles to fall below a set value, the maximum and root-mean-square (RMS) gradients to drop below a threshold, and the maximum and RMS coordinate steps to become sufficiently small [10] [2]. For example, in the AMS software, convergence is achieved when the energy change, maximum gradient, RMS gradient, maximum step, and RMS step all meet their respective criteria [2].

My optimization is oscillating and will not converge. What are the most common causes? Common causes for oscillating or non-converging optimizations include [11] [12] [6]:

- An inaccurate or poor initial Hessian: The initial guess of the second derivatives can lead the optimizer astray.

- An unreasonable starting geometry: The initial molecular structure may be too far from a stable configuration.

- SCF convergence failures: The self-consistent field procedure failing to converge at one or more geometry steps can prevent the optimizer from progressing reliably [12].

- Electronic state changes: The calculation may be jumping between different potential energy surfaces, confusing the optimizer [6].

What should I check first when an optimization fails to converge? First, inspect the optimization output to identify the specific non-converged criteria (energy, gradient, or step). Then, verify that your initial molecular geometry is reasonable and check for any SCF convergence warnings in the output log [12]. Ensuring that the initial guess for the wavefunction is stable can also prevent many common issues [13].

How do I choose appropriate convergence thresholds for my system?

The choice of thresholds depends on the desired accuracy and the computational cost. Looser criteria (e.g., LOOSE in NWChem) are suitable for pre-optimization or large systems, while tighter criteria (e.g., TIGHT) are necessary for frequency calculations or high-precision results [10]. The tables below provide standard values from different software packages to guide your selection.

Standard Convergence Criteria

Different computational chemistry packages use similar, but not identical, sets of criteria. The following tables summarize standard convergence thresholds.

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria in NWChem [10]

| Criterion | LOOSE | DEFAULT | TIGHT | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMAX (Max Gradient) | 0.00450 | 0.00045 | 0.000015 | Hartree/Bohr |

| GRMS (RMS Gradient) | 0.00300 | 0.00030 | 0.00001 | Hartree/Bohr |

| XMAX (Max Step) | 0.01800 | 0.00180 | 0.00006 | Bohr |

| XRMS (RMS Step) | 0.01200 | 0.00120 | 0.00004 | Bohr |

Table 2: Optimization Levels and Criteria in xtb [14]

| Level | Econv (Energy) | Gconv (Gradient) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| crude | 5 × 10â»â´ | 1 × 10â»Â² | Hartree |

| sloppy | 1 × 10â»â´ | 6 × 10â»Â³ | Hartree |

| loose | 5 × 10â»âµ | 4 × 10â»Â³ | Hartree |

| normal | 5 × 10â»â¶ | 1 × 10â»Â³ | Hartree |

| tight | 1 × 10â»â¶ | 8 × 10â»â´ | Hartree |

| vtight | 1 × 10â»â· | 2 × 10â»â´ | Hartree |

Table 3: Convergence Quality Settings in AMS [2]

| Quality | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Ã…) | Step (Ã…) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10â»Â³ | 10â»Â¹ | 1 |

| Basic | 10â»â´ | 10â»Â² | 0.1 |

| Normal | 10â»âµ | 10â»Â³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 10â»â¶ | 10â»â´ | 0.001 |

| VeryGood | 10â»â· | 10â»âµ | 0.0001 |

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Workflow

This workflow provides a structured approach to diagnosing and resolving common geometry optimization convergence problems.

Detailed Corrective Actions

Based on the diagnostic workflow, here are specific protocols to address convergence failures.

1. Addressing Gradient and Step Convergence Failures When the maximum or RMS gradients and steps fail to converge, the problem often lies with the optimization path or initial conditions.

- Improve the Initial Hessian: The Hessian (matrix of second derivatives) guides the optimization direction. You can specify a more accurate initial Hessian instead of a diagonal guess. For example, in NWChem, use

INHESS 2to read a Cartesian Hessian from a previous frequency calculation [10]. - Change the Optimization Algorithm: Different algorithms have different strengths.

- Steepest Descents: Very robust for poorly conditioned starting structures far from the minimum, but converges slowly near the minimum [15].

- Conjugate Gradient: More efficient than steepest descents for larger systems and converges well near the minimum [15] [16].

- Newton-Raphson: Uses second derivatives and can converge very quickly, but is more computationally expensive per step [15].

- Use a Pre-optimization Protocol: For a very poor starting structure, perform a initial optimization with loose criteria (e.g.,

LOOSEin NWChem) and the robust Steepest Descents algorithm. Then, use the resulting geometry as input for a high-precision optimization with tighter criteria and a Conjugate Gradient or Newton-Raphson algorithm [10] [15]. - Regenerate Internal Coordinates: If the geometry has changed significantly, the defined internal coordinates may become non-optimal. Using a directive like

REDOAUTOZcan clear the old Hessian and regenerate a better coordinate system at the current geometry [10].

2. Addressing Underlying SCF Convergence Failures Geometry optimization requires consistent and accurate energies and gradients. If the SCF procedure fails to converge at any point, it will derail the optimization [12].

- Increase SCF Iterations: Use a directive like

%scf MaxIter 500 endto allow more iterations for convergence [12]. - Employ Damping or Level Shifting: For oscillating SCF cycles, use keywords like

SlowConvor manually introduce a levelshift to stabilize the process [12]. - Improve the Initial Guess: Instead of a default guess, use

SCF_GUESS RESTARTto read orbitals from a previous, well-converged calculation of a similar structure [13]. Alternatively, converge a simpler method (e.g., BP86) and use its orbitals as a starting point withMORead[12]. - Change the SCF Solver: Switching between algorithms like DIIS, KDIIS, or a second-order converger (e.g., TRAH in ORCA) can resolve tricky convergence issues [12].

3. Protocol for Automatic Restart After Saddle Point Detection A robust automatic restart procedure is crucial for fully automated workflows. If an optimization converges to a saddle point (transition state) instead of a minimum, the system can be automatically displaced and the optimization restarted.

Experimental Protocol:

- Enable Saddle Point Characterization: After each optimization cycle, perform a quick frequency calculation or Hessian analysis to determine the nature of the stationary point found. This is enabled by properties like

PESPointCharacterin AMS [2]. - Check for Imaginary Frequencies: If one or more imaginary frequencies (negative eigenvalues) are found, the structure is a transition state or higher-order saddle point.

- Displace Geometry: Automatically distort the molecular geometry along the eigenvector corresponding to the largest-magnitude imaginary frequency. The displacement should be symmetry-breaking if symmetry is not used [2].

- Restart Optimization: Use the displaced geometry as the new starting point for a subsequent geometry optimization. The

MaxRestartskeyword controls how many times this process can be repeated automatically [2].

Example Input Snippet (AMS-style):

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Initial Hessian Guess | Provides the initial estimate of the second derivatives of energy, critically guiding the early optimization steps. Can be diagonal, read from file, or computed [10]. |

| Line Search Algorithm | A one-dimensional minimization performed along a search direction to find the optimal step size. Critical for the efficiency of methods like conjugate gradient [15]. |

| Internal Coordinates | A set of coordinates (bonds, angles, dihedrals) that can be more efficient for optimization than Cartesian coordinates. Can be regenerated (e.g., REDOAUTOZ) if the geometry changes significantly [10]. |

| SCF Convergers (DIIS, TRAH) | Algorithms that ensure the electronic structure calculation reaches a self-consistent solution. A stable SCF is a prerequisite for reliable geometry steps [12]. |

| PES Point Characterizer | A tool that calculates the lowest few Hessian eigenvalues to determine if an optimized structure is a minimum (all positive eigenvalues) or a saddle point (imaginary frequencies) [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Geometry Optimization Failures

Geometry optimization is an iterative process that can fail for various reasons. This guide helps you diagnose and remedy the most common failure modes.

1.1 How do I know if my optimization has failed?

An optimization can be considered failed if it terminates with an error message or produces unrealistic results. Key indicators include:

- Explicit Error Messages: The output log terminates with errors such as

ERROR: GEOMETRY NOT CONVERGED[17] orERROR: More cycles needed. Geometry NOT CONVERGED[17], indicating the calculation did not find a stationary point within the allowed number of steps. - Non-Convergence Warnings: Warnings like

Geometry optimization did not converge - frequencies are not calculated[17] signal that subsequent properties based on the optimized geometry cannot be reliably computed. - Unphysical Geometry: The final molecular structure contains impossibly long or short bond lengths, unrealistic angles, or other stereochemical impossibilities, even if the job finished without an explicit error.

1.2 My optimization did not converge. What are the first parameters to check?

If your optimization fails to converge, the first step is to investigate the convergence criteria and the optimization path itself.

- Review Convergence Criteria: Most software defines convergence based on thresholds for energy change, gradients (forces), and the step size. The default settings, labeled with a

Qualitysuch asNormal, may not be sufficient for your system [2]. You can systematically adjust these thresholds using pre-definedQualitylevels or custom values [2]. Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization (AMS) [2]Quality Setting Energy (Ha/atom) Gradients (Ha/Ã…) Step (Ã…) VeryBasic10â»Â³ 10â»Â¹ 1 Basic10â»â´ 10â»Â² 0.1 Normal10â»âµ 10â»Â³ 0.01 Good10â»â¶ 10â»â´ 0.001 VeryGood10â»â· 10â»âµ 0.0001 - Inspect the Optimization Path: Examine the intermediate geometries and energy changes reported in the output file. A "zig-zag" path or oscillations in the energy can indicate an issue with the initial Hessian (force constant matrix) or the optimizer's ability to navigate the potential energy surface.

1.3 What should I do if my optimization converges to a saddle point instead of a minimum?

Converging to a transition state (a first-order saddle point) is a common issue. Advanced strategies can automatically detect and correct for this.

- PES Point Characterization: Enable the calculation of the lowest Hessian eigenvalues (

PESPointCharacterin AMS) at the end of the optimization to determine the nature of the stationary point found [2]. - Automatic Restart: If a saddle point is detected, you can configure the software to automatically restart the optimization. It will displace the geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode (the mode with a negative frequency) and begin a new optimization run. This requires disabling symmetry (

UseSymmetry False) and setting a maximum number of restarts (MaxRestarts> 0) [2].

1.4 How can I handle difficult optimizations involving linear angles or soft modes?

Specific molecular features can cause numerical instability in the optimizer.

- Linear Angles: If a bond angle approaches 180°, the optimizer may generate a

GRADIENT ILL-DEFINEDwarning [17]. A solution is to reformulate the internal coordinates or, in some cases, introduce dummy atoms to redefine the coordinate space and avoid the singular region. - Soft Modes and Shallow Minima: For systems with very flat potential energy surfaces (e.g., weak intermolecular complexes), the default convergence criteria might be too strict relative to the energy changes. In such cases, loosening the energy convergence criterion (e.g., using

Basicquality) can be more effective than tightening it.

Advanced Restart Protocols and Configuration

Moving beyond simple restarts involves leveraging checkpoint files and sophisticated algorithms designed to escape flawed regions of the potential energy surface.

2.1 What is the most robust way to restart a failed optimization?

A simple restart using the last geometry is a good first step, but a more robust approach ensures the calculation has the best possible starting information.

- Restart from Final Geometry and Orbitals: For a single-point calculation restart, the process is often automated (

Autostart) to read the previous wavefunction (orbitals) from a.gbwor similar checkpoint file [3]. For geometry optimizations, you typically need to explicitly provide the last set of coordinates (from the output or a.xyzfile) and can optionally instruct the program to read the old orbitals using keywords likeMOREADand%moinp[3]. - Reuse the Hessian: If available, reading the Hessian from the previous job can significantly improve the convergence of the restarted optimization, as it provides the optimizer with curvature information about the potential energy surface.

2.2 What advanced algorithms can help find the correct minimum?

When standard optimizers fail, alternative algorithms can be employed.

- Quadratic Synchronous Transit (QST): Methods like QST2 and QST3 are designed specifically for locating transition states. They use reactant and product structures (QST2) or a guessed transition state as well (QST3) to navigate to the saddle point [7].

- Partial Optimizations: You can freeze parts of the molecule to focus the optimization on a specific region of interest. This is useful for large systems like enzymes or crystals. Using the

ReadOptimizekeyword, you can define a list of atoms to optimize while keeping others fixed [18].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for handling a failed geometry optimization, integrating both basic and advanced recovery strategies.

Advanced Recovery Workflow for Failed Optimizations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My job failed with an "SCF NOT CONVERGED" error, which aborted the geometry optimization. How do I proceed? [17]

A1: This is an electronic structure problem that cascades into a geometry failure. You must first address the SCF convergence. Strategies include tightening the SCF convergence criteria, using a better initial guess for the wavefunction, changing the SCF algorithm (e.g., to DIIS), or using the Stable keyword to check for and correct wavefunction instability. Once the SCF converges reliably, the geometry optimization can proceed.

Q2: When should I tighten the convergence criteria for a geometry optimization?

A2: Tightening criteria (e.g., to Good or VeryGood) is crucial when you need a highly precise geometry for subsequent property calculations, such as vibrational frequencies, bond orders, or high-level energy single-point calculations. However, be aware that "tight convergence criteria require accurate and noise-free gradients from the engine," and you may need to increase the numerical accuracy of your quantum chemistry code accordingly [2].

Q3: Is it possible to restart a numerical frequency calculation if it fails?

A3: Yes, numerical frequency calculations, which often involve multiple single-point calculations at displaced geometries, can be restarted. You typically need to ensure that the .hess or other intermediate files from the previous calculation are present and use a keyword like restart true in the frequency block [3]. This allows the job to continue from where it left off, saving significant computational time.

Q4: What is the "bent forward, hands on knees" posture best for? A4: While not related to computational chemistry, this posture has been studied in sports medicine as the most effective position for an athlete's physiological recovery between bouts of high-intensity exercise [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key software commands and input options that function as essential "reagents" for configuring and troubleshooting geometry optimizations.

| Item/Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

PESPointCharacter |

Calculates the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to determine if the optimized structure is a minimum or saddle point, enabling automated recovery protocols [2]. |

MaxRestarts |

Configures the maximum number of automatic restarts after converging to a saddle point. Essential for robust, unsupervised convergence to a true minimum [2]. |

ModRedundant / ReadOptimize |

Allows fine-grained control over the optimization process by letting you freeze, scan, or apply constraints to specific internal coordinates (Gaussian) [7] [18]. |

Convergence Quality |

A quick-setting parameter (Basic to VeryGood) to uniformly tighten or loosen convergence thresholds for energy, gradients, and step size [2]. |

.gbw / .chk Files |

Checkpoint files that store molecular orbitals and other wavefunction data. Critical for restarting jobs and providing a good initial guess to the SCF procedure [3]. |

OptimizeLattice |

A Boolean command (Yes/No) that, when set to Yes, allows for the optimization of both atomic positions and unit cell parameters for periodic systems [2]. |

| R4K1 | R4K1, MF:C82H146N34O19, MW:1912.3 g/mol |

| Biotin-PEG10-Acid | Biotin-PEG10-Acid, MF:C33H61N3O14S, MW:755.9 g/mol |

Implementing Automated Restart Protocols in Computational Workflows

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of the MaxRestarts option in a geometry optimization?

The MaxRestarts option enables an automatic restart procedure if a geometry optimization converges to a transition state (or a higher-order saddle point) instead of a local minimum. This is particularly useful when calculating properties like vibrational frequencies, which require a true minimum on the potential energy surface (PES). The optimizer will displace the geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode and restart the optimization, repeating this process until a minimum is found or the maximum number of restarts is reached [2] [20].

What does the PESPointCharacter property do?

The PESPointCharacter property performs a quick characterization of the stationary point found by the geometry optimizer. It calculates the lowest few Hessian eigenvalues to determine whether the structure is a local minimum (all real, positive frequencies) or a saddle point (one or more imaginary frequencies) [21]. When used together with MaxRestarts, it provides the critical information needed to trigger the automatic restart mechanism [2].

Why is my optimization not restarting automatically even though MaxRestarts is set?

The automatic restart feature has two key prerequisites:

- Symmetry must be disabled: The system must have no symmetry operators, or you must explicitly set

UseSymmetry Falsein your input. The displacement applied during a restart is often symmetry-breaking [2]. - PES point characterization must be active: You must enable the

PESPointCharacterproperty in thePropertiesblock of your input file to determine the nature of the converged structure [2].

What are the default convergence criteria for a geometry optimization?

A geometry optimization in AMS is considered converged when multiple conditions are met simultaneously. The default thresholds are defined in the table below [2]:

| Criterion | Threshold (Default) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1e-05 Ha | Change in energy is smaller than this value × number of atoms. |

| Gradients | 0.001 Ha/Ã… | Maximum Cartesian nuclear gradient. |

| Step | 0.01 Ã… | Maximum Cartesian step size. |

Configuration and Troubleshooting Guide

How to Configure Automatic Restarts

To set up an automatic restart for a geometry optimization, you need to configure both the GeometryOptimization block and the Properties block in your AMS input file.

Explanation of Key Settings:

MaxRestarts 5: This allows the optimization to be restarted a maximum of 5 times if a transition state is found [2].RestartDisplacement 0.05: This optional parameter sets the size of the displacement (in Ångströms) for the atom that moves the farthest during the restart [2].UseSymmetry False: This is a crucial requirement, as the displacement applied during a restart often breaks symmetry [2].PESPointCharacter Yes: This enables the calculation that identifies if the structure is a transition state, triggering the restart [21].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization stops at a transition state. | MaxRestarts is 0 (default) or PESPointCharacter is not enabled. |

Enable PESPointCharacter and set MaxRestarts to a value >0 [2]. |

| Restarts do not occur even when a TS is found. | Symmetry is enabled in the system. | Add UseSymmetry False to the input file [2]. |

| Optimization takes too long or uses too many restarts. | The RestartDisplacement is too large, pushing the system too far. |

Reduce the RestartDisplacement value [2]. |

| "Noisy" gradients from the engine lead to mischaracterization. | The engine's numerical accuracy is insufficient for tight convergence. | Increase the numerical accuracy in the engine's settings (e.g., NumericalQuality in BAND) [2]. |

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a geometry optimization with automatic restarts enabled.

Workflow Explanation:

- The geometry optimization runs until its convergence criteria are met [2].

- The

PESPointCharacterproperty is invoked to compute the Hessian and classify the stationary point [21]. - The logic checks if the structure is a local minimum. If yes, the calculation proceeds successfully.

- If imaginary frequencies are found (a transition state), the algorithm checks if the

MaxRestartslimit has not been exceeded. - If restarts are available, the geometry is displaced along the imaginary mode, and the optimization restarts from this new point [2].

- If the maximum number of restarts is reached, the calculation stops, and the final structure may still be a transition state.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists the essential "ingredients" or components for setting up a robust geometry optimization with automatic restart capabilities in AMS.

| Item | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

MaxRestarts |

The core parameter that defines the maximum number of automatic restart attempts after finding a saddle point [2]. |

PESPointCharacter |

The diagnostic tool that determines the nature (minimum or saddle point) of the optimized geometry [21]. |

UseSymmetry False |

A critical environmental setting that disables symmetry constraints, allowing for the symmetry-breaking displacements required for restarts [2]. |

RestartDisplacement |

A tunable parameter that controls the magnitude of the geometry displacement applied during a restart, with a default of 0.05 Ã… [2]. |

Convergence Criteria (Energy, Gradients, Step) |

Define the quality and precision of the final optimized geometry. Tighter criteria (e.g., "Good" or "VeryGood") are often needed for accurate frequency calculations [2]. |

| Computational Engine (e.g., ADF, DFTB, ForceField) | Defines the potential energy surface by calculating the energies and forces. Its accuracy is paramount for a correct PES characterization [22]. |

| SR1664 | SR1664, MF:C33H29N3O5, MW:547.6 g/mol |

| Timonacic-d4 | Timonacic-d4, MF:C4H7NO2S, MW:137.20 g/mol |

Stochastic resetting (SR) is the procedure of stopping a random process at random or predetermined times and restarting it from its initial condition. This simple concept has emerged as a powerful tool to accelerate processes ranging from computer algorithms to molecular simulations by mitigating the deleterious effects of long-tailed first-passage time distributions [23]. In the context of computational chemistry and molecular dynamics (MD), SR provides a collective variable-free approach to enhanced sampling, overcoming a significant limitation of other methods like Metadynamics that require identification of slow mode variables [23] [24].

The fundamental principle behind stochastic resetting's effectiveness lies in its ability to eliminate long trajectories that wander into unproductive regions of phase space. For molecular dynamics simulations, which are inherently limited to microsecond timescales, this approach enables the study of rare events that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive [23]. By periodically restarting simulations, SR effectively reduces the mean first-passage time (MFPT) for transitions between metastable states, providing acceleration factors that can reach an order of magnitude when used as a standalone method, and even greater when combined with other enhanced sampling techniques [24].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Stochastic Resetting

| Property | Without Resetting | With Resetting |

|---|---|---|

| First-Passage Time | Can diverge for diffusion processes | Always finite at finite resetting rates |

| Position Distribution | Broadens continuously with time (e.g., Gaussian) | Reaches a non-equilibrium steady state (e.g., Laplace) |

| Energetic Cost | None for free diffusion | Fundamental minimum cost exists |

| Implementation Complexity | N/A | Simple, requires only restart capability |

Theoretical Foundation and Mechanisms

The theoretical underpinnings of stochastic resetting were established in the seminal work of Evans and Majumdar, who studied a particle diffusing in one dimension while being returned to its initial position at random times sampled from an exponential distribution with rate (r) [25] [23]. For a Brownian particle undergoing free diffusion, the probability distribution without resetting is a Gaussian with variance that grows linearly with time, meaning the particle spreads indefinitely. With resetting, however, the system reaches a non-equilibrium steady state characterized by a Laplace distribution that remains localized around the resetting position [25] [26].

The mechanism for acceleration can be understood by examining the first-passage time (FPT) distribution. Many stochastic processes, including molecular transitions, exhibit FPT distributions with slowly decaying tails - while there is high probability of sampling short FPTs, the distribution has a very broad tail [23]. Resetting eliminates trajectories with extremely long FPTs, resulting in a modified FPT distribution that decays much faster and consequently has a smaller mean [23].

A crucial result for practitioners is the sufficient condition for acceleration: resetting is guaranteed to reduce the MFPT when the coefficient of variation (COV) - the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of the FPT distribution - is greater than one [24]. This condition indicates a broad distribution where resetting can effectively eliminate the detrimental effect of long trajectories while preserving the beneficial short ones.

Implementation Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Resetting Protocol

The implementation of stochastic resetting in molecular dynamics simulations follows a straightforward procedure [23]:

- Initialize the system in a state of interest (e.g., a metastable basin)

- Draw a random resetting time (t) from an exponential distribution with rate (r)

- Propagate the simulation until either:

- The event of interest occurs (first-passage), or

- Time (t) is reached without the event occurring

- If resetting occurs, return the system to its initial state and repeat from step 2

- Continue until the event of interest is observed, keeping cumulative time

This protocol can be implemented with almost any MD code, as it requires only the ability to stop and restart simulations while continuing to monitor the overall simulation time [23]. The resetting rate (r) is a crucial parameter that must be carefully chosen - too low provides minimal acceleration, while too high prevents the system from making progress toward the target state.

Adaptive Resetting Protocol

Recent advances have introduced adaptive resetting, where the resetting rate depends on the system state and history, allowing for more sophisticated protocols [27]. This approach enables "informed search strategies" where the resetting probability decreases when the system is near the target, preventing undesirable resetting events that would occur with standard resetting [27].

The implementation of adaptive resetting uses a state- and time-dependent resetting rate (r(\mathbf{X}, t)), where the probability of resetting before time (t) for a given trajectory ({\mathbf{X}(t'), 0 \le t' \le t}) is:

[ \text{Pr}(R \le t) = 1 - \exp\left(-\int_0^t r(\mathbf{X}(t'), t') dt'\right) ]

This formulation allows the resetting protocol to incorporate information about reaction progress, leading to substantially greater acceleration compared to standard resetting [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Resetting Protocols

| Protocol Type | Resetting Rate | Implementation Complexity | Typical Acceleration | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Constant (r) | Low | ~4x (standalone) | Systems with unknown CVs |

| Adaptive | (r(\mathbf{X}, t)) | Moderate | >10x | Systems with partial knowledge |

| MetaD Combined | Constant or adaptive | High | >100x | Complex systems with suboptimal CVs |

Integration with Existing Enhanced Sampling Methods

Combination with Metadynamics

Stochastic resetting can be effectively combined with Metadynamics (MetaD), with each method compensating for the drawbacks of the other [24]. When applied together, the two methods can produce greater acceleration than either method separately, even when using optimal collective variables in MetaD [24].

The combined protocol works as follows [24]:

- Initialize the system and set up MetaD with chosen collective variables

- Draw a random resetting time from an exponential distribution

- Run MetaD simulation until either:

- The transition occurs, or

- The resetting time is reached

- Upon resetting:

- Return the system to its initial state

- Reset the MetaD bias to zero

- Continue the process, accumulating total simulation time

This approach is particularly valuable when only suboptimal collective variables are available. Resetting MetaD simulations performed with suboptimal CVs can lead to speedups comparable to those obtained with optimal CVs, providing an alternative to the challenging task of improving CV quality [24].

Resetting in Laboratory Experiments

Experimental realization of diffusion with stochastic resetting has been achieved using colloidal particles and holographic optical tweezers [26]. This experimental platform has confirmed key theoretical predictions, including:

- Formation of non-equilibrium steady states

- Reduction of mean first-passage times

- Existence of a fundamental minimal energetic cost for resetting

The experimental work has also explored practical considerations like non-instantaneous returns, where finite velocities for returning particles to the origin affect the steady-state distribution and energetic costs [26].

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I determine if stochastic resetting will accelerate my simulations? A: A sufficient condition for acceleration is that the coefficient of variation (COV) of your first-passage time distribution is greater than 1 [24]. The COV is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of the FPT distribution. If this condition is met, introducing a small finite resetting rate is guaranteed to reduce the MFPT.

Q2: How do I choose the optimal resetting rate? A: The optimal resetting rate typically shows a non-monotonic relationship with the MFPT [23]. At low rates, acceleration increases with rate until reaching an optimum, after which further increases degrade performance. The optimal rate can be estimated from a set of trajectories without resetting using reweighing procedures [27], or through iterative testing across a range of rates.

Q3: Why does my simulation show no acceleration with resetting? A: Possible causes include:

- The FPT distribution has COV < 1 (not amenable to standard resetting)

- The resetting rate is too high, preventing system progression

- The initial state is poorly chosen, not representing a true metastable state

- The return protocol after resetting is too slow, dominating the simulation time

Q4: Can I use resetting with already-biased simulations? A: Yes, resetting can be combined with other enhanced sampling methods like Metadynamics [24]. When doing so, remember to reset both the system configuration and any time-dependent biases (e.g., set the Metadynamics bias to zero upon resetting).

Q5: How does resetting affect the estimation of kinetic properties? A: Properly implemented, resetting enables inference of unbiased kinetics from accelerated simulations [23] [24]. Methods have been developed to extract unbiased mean first-passage times from simulations with resetting, with and without Metadynamics.

Common Error Conditions and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Issues with Stochastic Resetting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No speedup observed | COV of FPT < 1 | Use adaptive resetting or combine with other methods |

| Overly aggressive resetting | Reduce resetting rate | |

| Poor initial state selection | Choose robust metastable state as initial condition | |

| Poor sampling of transition paths | Resetting too frequent | Lower resetting rate to allow path development |

| Incomplete resetting protocol | Ensure complete reinitialization of velocities | |

| High computational overhead | Slow resetting implementation | Optimize restart procedures in simulation code |

| Excessive saving/loading | Use in-memory restart when possible | |

| Unphysical results | Incorrect time accounting | Ensure cumulative time tracking across resets |

| Inadequate equilibration | Include brief equilibration after each reset |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Computational Components for Resetting Experiments

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Resetting Time Generator | Generates random resetting times from chosen distribution | Typically exponential distribution for standard resetting |

| State Monitor | Tracks system state and detects resetting conditions | Must efficiently identify when to reset |

| System Reinitializer | Returns system to initial state upon resetting | Can include partial equilibration if needed |

| Bias Resetter | Resets external biases in combined methods | Essential when using with MetaD |

| Time Accumulator | Tracks cumulative simulation time | Critical for proper kinetics estimation |

| Path Sampling Module | Stores trajectory segments between resets | Enables analysis of transition mechanisms |

Applications and Case Studies

Biomolecular Systems

Stochastic resetting has been successfully applied to biomolecular systems, including conformational transitions in alanine tetrapeptide and folding of the mini-protein chignolin in explicit water [24]. In these applications, resetting provided significant acceleration while enabling extraction of unbiased kinetic information.

For the chignolin system, adaptive resetting protocols using neural network representations of state-dependent resetting probabilities were able to minimize the MFPT for conformational transitions [27]. This demonstrates how machine learning can be integrated with resetting to develop optimized protocols for complex systems.

Pharmaceutical Applications

In drug development, resetting approaches have been proposed as "antiviral therapies" that prevent drug resistance development [28]. In these models, the efficacy of a therapy is described by a one-dimensional stochastic resetting process, where optimal therapy resetting rates can maximize the time until complete drug resistance develops.

The application of resetting concepts to population dynamics of viral infections represents an innovative extension of the method beyond molecular simulations, demonstrating the breadth of potential applications for this approach [28].

Limitations and Future Directions

While powerful, stochastic resetting has limitations. The method introduces a fundamental energetic cost that cannot be made arbitrarily small due to constraints on realistic resetting protocols [26]. Additionally, not all processes benefit from resetting - those with narrow FPT distributions (COV < 1) may experience increased MFPT with resetting [24].

Future developments in the field include:

- Improved adaptive resetting protocols that more intelligently use system state information

- Machine learning optimized resetting strategies for complex systems

- Multi-scale resetting approaches that operate at different time and length scales

- Experimental applications beyond colloidal systems to biological and chemical processes

As the theoretical understanding of resetting deepens and computational implementations become more sophisticated, stochastic resetting is poised to become an increasingly valuable tool in the computational scientist's toolkit, particularly for accelerating sampling of rare events in complex molecular systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the first signs that my geometry optimization is failing and might need a restart? Look at the energy changes over the last ten iterations. If the energy is consistently increasing or decreasing, possibly with occasional jumps, and the starting geometry was far from a minimum, the optimization is likely proceeding but needs more time; you should simply increase the number of allowed iterations and restart from the latest geometry [1]. However, if the energy is oscillating around a value and the energy gradient is hardly changing, this indicates a potential problem with the calculation setup that needs to be addressed before restarting [1].

2. My optimization fails due to a very small HOMO-LUMO gap. What should I do?

A small HOMO-LUMO gap can cause the electronic structure to change between optimization steps, leading to non-convergence [1]. First, verify that you have a correct ground state from a single-point calculation and check that the spin-polarization value is correct [1]. You can also try freezing the number of electrons per symmetry using an OCCUPATIONS block to prevent repopulation between molecular orbitals of different symmetry [1].

3. What should I check if my optimized bond lengths are unrealistically short? Overly short bond lengths can indicate a basis set problem, especially if you are using the Pauli relativistic method [1]. The recommended solution is to abandon the Pauli method and use the ZORA relativistic approach instead [1]. If you must use the Pauli formalism, try applying bigger frozen cores or reducing the flexibility of the basis set's s- and p-functions [1].

4. How can I adjust the convergence criteria for a tighter optimization? You can control the convergence using predefined sets or individual parameters. The following table summarizes the standard criteria in atomic units [10]:

| Criterion | Loose | Default | Tight |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMAX (Max gradient) | 0.00450 | 0.00045 | 0.000015 |

| GRMS (RMS gradient) | 0.00300 | 0.00030 | 0.00001 |

| XMAX (Max Cartesian step) | 0.01800 | 0.00180 | 0.00006 |

| XRMS (RMS Cartesian step) | 0.01200 | 0.00120 | 0.00004 |

5. What is the purpose of the CLEAR and REDOAUTOZ directives when restarting?

The CLEAR directive discards saved Hessian information from a previous optimization, forcing a fresh restart [10]. The REDOAUTOZ directive is useful if the geometry has changed significantly; it deletes the old Hessian and regenerates the internal coordinates based on the current geometry, which can be vital if the previous set of coordinates became invalid or non-optimal [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Does Not Converge (Oscillations)

Diagnosis: If the energy oscillates and the gradient stops improving, the calculated forces may be insufficiently accurate [1].

Resolution Protocol:

- Increase Calculation Accuracy:

- Change Optimization Coordinates: If you are using Cartesian coordinates, switch to delocalized internal coordinates, as they typically require fewer steps to converge [1].

- Restart from Latest Geometry: Simply continue the optimization from the most recent geometry with an increased iteration limit [1].

Problem: Handling Angles Close to 180 Degrees

Diagnosis: Optimization can become unstable if a valence angle becomes close to 180 degrees during the process, particularly if it connects large fragments [1].

Resolution Protocol:

- Restart: Restart the geometry optimization from the latest geometry. ADF handles angles initially larger than 175 degrees or terminal bond angles automatically, but angles that evolve during optimization may need a restart [1].

- Constraint as Last Resort: If restarting does not work, constrain the angle to a value close to, but not equal to, 180 degrees and optimize the rest of the structure [1].

Problem: Transition State Search Follows the Wrong Mode

Diagnosis: During a saddle-point (transition state) search, the optimizer might start following an incorrect negative mode, for example, one transverse to the desired reaction coordinate [10].

Resolution Protocol:

- Specify Initial Direction: You can force the initial search direction along a specific internal variable (

VARDIR) or a specific eigen-mode (MODDIR) [10]. - Prevent Automatic Switching: Use the

NOFIRSTNEGdirective to prevent the code from automatically latching onto the first negative mode it finds. This forces it to continue mode-following based on overlap until your mode of interest turns negative [10].

Experimental Restart Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for diagnosing and restarting a failed geometry optimization.

Automatic Restart Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below details key computational parameters and their functions for controlling geometry optimizations and restarts.

| Item/Reagent | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Convergence Criteria (GMAX, GRMS) | Control the maximum and root-mean-square gradients in the chosen coordinate system; primary targets for optimization completion [10]. |

Initial Hessian (INHESS) |

Defines the initial guess for the second energy derivative. A good guess (e.g., from a frequency calculation) can dramatically speed up convergence [10]. |

Trust Radius (TRUST) |

Controls the maximum allowed step size during minimization, preventing overly large steps in unstable regions of the potential energy surface [10]. |

SCF Convergence (converge) |

Sets the threshold for the self-consistent field cycle. Tighter values (e.g., 1e-8) provide more accurate forces and can resolve oscillation issues [1]. |

| Basis Set Scaling | Diagonal elements of the initial Hessian can be scaled separately for bonds (BSCALE), angles (ASCALE), and torsions (TSCALE) to improve optimization efficiency [10]. |

Forced Color Adjust (forced-color-adjust) |

A CSS property used in visualization tools to ensure that user-enforced color palettes (e.g., high contrast mode) do not break the legibility of diagrams and output [29]. |

| Arachidyl linoleate | Arachidyl linoleate, MF:C38H72O2, MW:561.0 g/mol |

| Mordant Blue 29 | Mordant Blue 29, MF:C23H13Cl2Na3O9S, MW:605.3 g/mol |

Handling Lattice Vector Optimization and Periodic System Restarts

Troubleshooting Guides

SCF Convergence Failure During Optimization

Problem: The Self-Consistent Field (SCF procedure fails to converge during geometry optimization of a periodic system, halting the entire process.

Solution:

- Conservative Mixing Parameters: Decrease the mixing parameters to improve stability [30]:

- Alternative SCF Methods: Switch to the MultiSecant method, which comes at no extra computational cost per cycle [30]:

- Finite Electronic Temperature: Use a higher electronic temperature at the start of the optimization when gradients are large, automatically reducing it as the geometry converges [30]. This can be implemented via engine automations:

- Basis Set Strategy: For difficult systems, first converge the SCF with a smaller basis set (e.g., SZ), then restart the calculation with the target basis set [30].

Lattice Optimization Not Converging for GGA Functionals

Problem: The lattice vector optimization fails to converge when using Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functionals.

Solution:

- Analytical Stress: Enable analytical stress calculations instead of numerical stress [30]:

- Fixed Confinement Radius: Set

SoftConfinementto a fixed value (default is 10.0) rather than allowing it to depend on lattice vectors [30]. - libxc Library: Use the libxc library for the exchange-correlation functional, as it provides the derivatives required for analytical stress [30].

Geometry Optimization Converging to Saddle Points

Problem: The optimization converges to a transition state (saddle point) rather than a local minimum.

Solution:

- Automatic Restart with PES Point Characterization: Enable automatic restart when a saddle point is detected [2]:

- Symmetry Handling: Disable symmetry using

UseSymmetry Falseas automatic restarts often involve symmetry-breaking displacements [2]. - Displacement Control: Set

RestartDisplacementto control the magnitude of displacement along the imaginary mode (default: 0.05 Ã…) [2].

Handling Dependent Basis Set Errors

Problem: Calculation aborts due to linear dependency in the basis set for periodic systems.

Solution:

- Basis Set Confinement: Apply confinement to reduce the range of diffuse basis functions, particularly for highly coordinated atoms [30]:

- Selective Confinement: In slab systems, use normal basis sets for surface atoms (to properly describe vacuum decay) and confined basis functions for inner layers [30].

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the default convergence criteria for geometry optimization in periodic systems?

The optimization is considered converged when all these criteria are met [2]:

| Criterion | Threshold | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | < 1.0e-05 Ha × number of atoms | Difference in bond energy between steps |

| Maximum Gradient | < 0.001 Ha/Ã… | Largest Cartesian nuclear gradient |

| RMS Gradient | < 0.00067 Ha/Ã… | Root-mean-square of gradients |

| Maximum Step | < 0.01 Ã… | Largest Cartesian step size |

| RMS Step | < 0.0067 Ã… | Root-mean-square of step sizes |

Note: If maximum and RMS gradients are 10 times smaller than the Convergence%Gradient criterion, the step criteria are ignored [2].

How can I adjust optimization accuracy for different research needs?

Use the Convergence%Quality setting to quickly adjust all thresholds [2]:

| Quality | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Ã…) | Step (Ã…) | Stress/Atom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10â»Â³ | 10â»Â¹ | 1 | 5×10â»Â² |

| Basic | 10â»â´ | 10â»Â² | 0.1 | 5×10â»Â³ |

| Normal | 10â»âµ | 10â»Â³ | 0.01 | 5×10â»â´ |

| Good | 10â»â¶ | 10â»â´ | 0.001 | 5×10â»âµ |

| VeryGood | 10â»â· | 10â»âµ | 0.0001 | 5×10â»â¶ |

How do I enable lattice vector optimization in my calculation?

Set the OptimizeLattice parameter to Yes in the GeometryOptimization block [2]:

Note: This is supported with Quasi-Newton, FIRE, and L-BFGS optimizers [2].

What should I check if my phonon calculation shows negative frequencies?

Negative frequencies indicate unphysical results with two likely causes [30]:

- Incomplete Geometry Optimization: Ensure the geometry is fully converged to a minimum.

- Insufficient Numerical Accuracy: Increase the step size in the Phonon run or improve general accuracy settings (numerical integration, k-space sampling).

Experimental Protocols

Automated Restart Procedure for Failed Geometry Optimizations

Purpose: Automatically detect and recover from optimization failures in periodic systems, particularly those converging to saddle points or failing due to numerical issues.

Methodology:

- Enable PES Point Characterization: Configure the calculation to analyze the nature of stationary points after optimization [2]:

Configure Restart Parameters: Set up the optimization block to handle automatic restarts [2]:

Disable Symmetry: Allow symmetry-breaking displacements during restarts [2]:

Implementation Logic:

- After each geometry convergence, the PES point character is evaluated

- If a saddle point is detected (imaginary frequencies present), the structure is displaced along the lowest frequency mode

- The displacement magnitude is controlled by

RestartDisplacement(default: 0.05 Ã…) - The optimization restarts with the displaced geometry

- This process repeats up to

MaxRestartstimes or until a true minimum is found

Adaptive Convergence Protocol for Difficult Systems

Purpose: Balance computational efficiency and accuracy by dynamically adjusting convergence criteria during optimization.

Methodology:

- Initial Setup: Configure the GeometryOptimization block with engine automations [30]:

Progressive Tightening:

- Electronic Temperature: Starts at 0.01 Hartree for initial steps, decreases to 0.001 Hartree as gradients reduce

- SCF Convergence: Looser criteria (1.0e-3) initially, tightening to 1.0e-6 in later iterations

- SCF Iterations: Maximum SCF cycles increase from 30 to 300 as optimization progresses

Gradient-Based Triggers:

- When nuclear gradients exceed

HighGradient(0.1), less strict settings are applied - When gradients fall below

LowGradient(0.001), tighter convergence criteria are used - Intermediate values are linearly interpolated on a logarithmic scale

- When nuclear gradients exceed

Workflow Visualization

Automatic Restart Logic for Failed Optimizations

Periodic System Optimization Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| SCF Convergence Accelerators | Improve Self-Consistent Field convergence in difficult metallic/slab systems | SCF Method MultiSecant or DIIS Variant LISTi [30] |

| Analytical Stress Tools | Enable efficient lattice optimization with GGA functionals | StrainDerivatives Analytical=yes with libxc [30] |

| Automatic Restart Framework | Recover from saddle point convergence automatically | MaxRestarts 5 with PESPointCharacter True [2] |

| Adaptive Convergence Control | Balance accuracy and efficiency during optimization | EngineAutomations with gradient-based triggers [30] |

| Basis Set Stability Tools | Resolve linear dependency issues in periodic basis sets | Confinement of diffuse functions for inner slab atoms [30] |

| Numerical Quality Presets | Ensure sufficient accuracy for forces and stresses | NumericalQuality Good or custom radial grid settings [30] |

| Myristoleyl behenate | Myristoleyl behenate, MF:C36H70O2, MW:534.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Vat Blue 6 | Vat Blue 6, CAS:39456-82-1, MF:C28H12Cl2N2O4, MW:511.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This technical support guide provides researchers with protocols for diagnosing and resolving failed frequency calculations, a critical step in ensuring the reliability of optimized molecular structures in computational drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. My geometry optimization completed successfully, but my subsequent frequency calculation says the structure is not converged. Is my optimized structure reliable?