Beyond the Saddle: Strategies for Robust Molecular Geometry Optimization in Drug Discovery

This article addresses the critical challenge of convergence to saddle points during molecular geometry optimization, a non-convex optimization problem that can hinder the identification of stable, bioactive conformations in computational...

Beyond the Saddle: Strategies for Robust Molecular Geometry Optimization in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of convergence to saddle points during molecular geometry optimization, a non-convex optimization problem that can hinder the identification of stable, bioactive conformations in computational drug discovery. We explore the foundational theory of potential energy surfaces and the nature of saddle points, detail advanced methodological solutions including automated restarts and noisy gradient descent, provide a troubleshooting guide for optimizing convergence criteria, and present a rigorous validation framework incorporating energy evaluation and chemical accuracy checks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to enhance the reliability and efficiency of geometry optimization workflows.

Understanding Saddle Points: The Fundamental Challenge in Non-Convex Molecular Optimization

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Convergence to Saddle Points

FAQ: Why does my geometry optimization sometimes converge to a saddle point instead of a minimum?

A saddle point, or transition state, is a stationary point on the potential energy surface (PES) where the Hessian matrix (matrix of second energy derivatives) has one negative eigenvalue. Optimization algorithms descend the PES based on energy and gradients, and can inadvertently converge to these points if the initial structure is in their vicinity or if the algorithm lacks a mechanism to distinguish them from true minima [1]. This is a common challenge when the starting geometry is guessed or is derived from a similar molecular system.

FAQ: What practical steps can I take to escape a saddle point once it is found?

If your optimization has converged to a saddle point, you can use an automatic restart feature, available in software like AMS. This requires enabling PES point characterization and setting a maximum number of restarts. The system will then be displaced along the imaginary vibrational mode (the mode with the negative force constant) and the optimization will be restarted. For this to work effectively, molecular symmetry should be disabled [2].

- Example Configuration (AMS):

The

RestartDisplacementkeyword can control the size of this displacement [2].

FAQ: How can I ensure my optimization is robust and converges to a local minimum?

Using tighter convergence criteria increases the reliability of your final geometry. While the default settings in most software are reasonable for many applications, they may be inadequate for systems with a very flat or very steep PES around the minimum [2]. The table below compares standard convergence criteria sets.

Table: Comparison of Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria

| Software | Quality Setting | Energy (Hartree/atom) | Max Gradient (Hartree/Bohr) | Max Step (Bohr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMS [2] | Normal (Default) | 1.0 × 10â»âµ | 1.0 × 10â»Â³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 1.0 × 10â»â¶ | 1.0 × 10â»â´ | 0.001 | |

| VeryGood | 1.0 × 10â»â· | 1.0 × 10â»âµ | 0.0001 | |

| NWChem [3] | Default | --- | 0.00045 | 0.00180 |

| Tight | --- | 0.000015 | 0.00006 |

Note: Convergence typically requires satisfying multiple conditions simultaneously, including thresholds for energy change, maximum gradient, RMS gradient, maximum step, and RMS step [2] [3].

FAQ: My optimization is not converging. What should I check?

First, verify that the optimization is not stuck due to overly strict criteria. The maximum number of optimization cycles (MaxIterations in AMS, MAXITER in NWChem, GEOM_MAXITER in Psi4) might need to be increased for complex systems [2] [3] [4]. Second, review the initial geometry and Hessian. A poor initial guess for the Hessian can slow convergence. Some programs allow you to compute an initial Hessian numerically or read it from a previous frequency calculation [3] [4]. Finally, for tricky optimizations, consider using more advanced algorithms like the Berny algorithm in Gaussian, which uses redundant internal coordinates and can be more efficient than Cartesian-based optimizers [5].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Minimum Search

Protocol 1: Minimum Search with Saddle Point Verification and Restart

This protocol is designed to systematically find a local minimum and automatically correct for convergence to a first-order saddle point.

- Initial Optimization: Start a standard geometry optimization (

Task GeometryOptimizationin AMS,optimize('scf')in Psi4) using "Normal" or "Good" convergence criteria [2] [4]. - Stationary Point Characterization: Upon convergence, activate PES point characterization by calculating the lowest few eigenvalues of the Hessian to determine the nature of the stationary point found [2].

- Decision & Restart:

- If the Hessian has no negative eigenvalues, a local minimum has been found. The procedure is complete.

- If the Hessian has one or more negative eigenvalues, a saddle point has been found. Enable the automatic restart feature with a displacement along the lowest frequency mode to guide the system away from the saddle point and back towards a minimum-seeking path [2].

- Final Validation: After the restarted optimization converges, perform a final frequency calculation to confirm all vibrational frequencies are real, verifying a true local minimum.

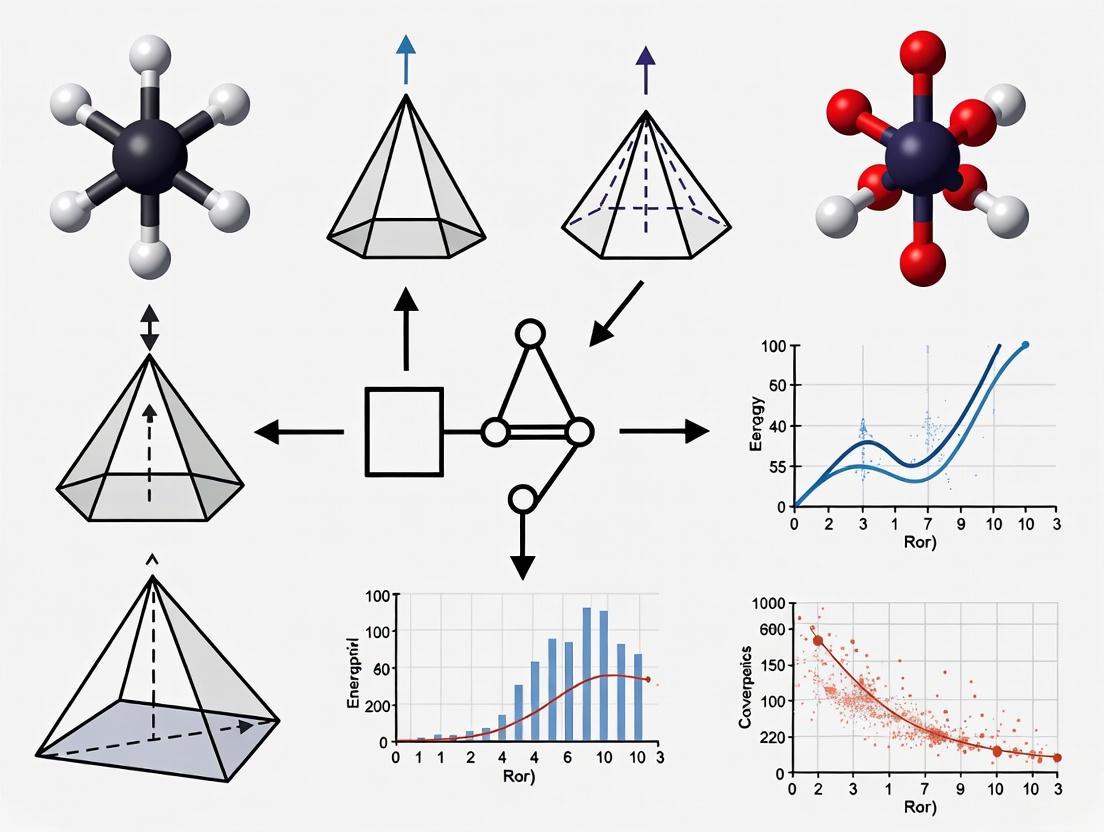

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol.

Protocol 2: Employing Gaussian Process Regression for Accelerated Searches

For computationally expensive calculations, using a machine learning-accelerated approach can significantly reduce the number of energy and force evaluations required to find a minimum.

- Build a Surrogate Model: Use Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) to create a local approximation (surrogate model) of the PES based on initial electronic structure calculations [6] [7].

- Optimize on Surrogate: Perform the geometry optimization steps on the computationally cheap GPR surrogate surface to propose a new geometry.

- Update Model: At the new geometry, run an electronic structure calculation to get the actual energy and forces. Use this data to refine and update the GPR model.

- Iterate to Convergence: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until the optimization converges on the true PES. This method can reduce the number of expensive electronic structure calculations by an order of magnitude [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization Studies

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AMS Software [2] | Performs geometry optimizations with configurable convergence and automatic restart from saddle points. | Implementing "Protocol 1" for robust minimum searches in organometallic catalysts. |

| Gaussian Software [5] | Uses the Berny algorithm in redundant internal coordinates, often efficient for minimum and transition state searches. | Optimizing stable conformers of drug-like molecules and probing reaction pathways (QST2/QST3). |

| Psi4 (with optking) [4] | An open-source quantum chemistry package featuring the optking optimizer for geometry minimization and transition state location. | Conducting constrained optimizations for scanning potential energy surfaces of flexible peptides. |

| GPDimer / OT-GP Algorithm [6] [7] | Accelerates saddle point searches using a Gaussian Process surrogate model, greatly reducing electronic structure calculations. | Efficiently locating transition states and ensuring subsequent minimum searches start from a valid path. |

| CHARMM Force Field [8] | An empirical force field, extended for non-natural peptides, used for geometry optimization in molecular mechanics. | Energy minimization and conformational searching of β-peptide foldamers prior to quantum chemical analysis. |

| Perfluoropentanoic acid | Perfluoropentanoic Acid | High-Purity PFPeA Reagent | Perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA), a high-purity perfluorinated compound for environmental & materials science research. For Research Use Only. |

| 2-Hydroxytricosanoic acid | 2-Hydroxytricosanoic Acid | High-Purity Fatty Acid | RUO | High-purity 2-Hydroxytricosanoic acid for lipidomics & neurological disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Escaping Saddle Points in High-Dimensional Optimization

Problem Statement: Training progress (loss decrease) stagnates for an extended number of iterations, but it is unclear whether the optimizer has found a true local minimum or is trapped in a deceptive saddle point.

| Observation | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Resolution Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss stabilizes at a high value; gradient norm becomes very small [9]. | Trapped in a strict saddle point [10]. | Check for negative eigenvalues in the Hessian (or use power iteration to estimate the minimum eigenvalue) [9]. | Introduce perturbations to gradient descent when gradients are small [10]. |

| Loss plateaus, then suddenly drops after many iterations. | Slow escape from a saddle region due to flat curvature [9]. | Monitor the variance of gradients across mini-batches; high variance may indicate nearby negative curvature [9]. | Use optimizers with momentum (e.g., SGD with Momentum, Adam) to accumulate speed in flat regions [9]. |

| Convergence is slow, even with adaptive learning rates. | The saddle point may be non-strict or the landscape highly ill-conditioned [11]. | Use a Lanczos method to approximate the Hessian's eigen-spectrum for a more complete curvature picture. | Consider stochastic gradient descent (SGD), where inherent noise helps escape saddles [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Perturbed Gradient Descent (PGD)

This protocol is designed to efficiently escape strict saddle points [10].

- Initialization: Initialize parameters ( x0 ) randomly. Choose a step size ( \eta = O(1/\ell) ), where ( \ell ) is the gradient Lipschitz constant. Set a perturbation radius ( r ), and a gradient threshold ( g{\text{thresh}} ).

- Gradient Update: For iteration ( t = 1, 2, ..., T ), perform the core update: ( xt \leftarrow x{t-1} - \eta \nabla f (x_{t-1}) )

- Perturbation Condition: Check if the gradient norm ( \|\nabla f (xt)\| \leq g{\text{thresh}} ).

- Add Perturbation: If the condition in step 3 is met, add a small random perturbation: ( xt \leftarrow xt + \xit ) where ( \xit ) is sampled uniformly from a ball of radius ( r ).

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-4 until convergence to an ( \epsilon )-second-order stationary point.

Visualization of PGD Escape Dynamics

Guide 2: Verifying Convergence to a True Local Minimum

Problem Statement: The optimization has converged (gradient is zero), but you need to verify that the solution is a true local minimum and not a saddle point before proceeding with analysis or deployment.

| Verification Method | Description | Technical Implementation | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hessian Eigenvalue Analysis [10] | Compute the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix ( \nabla^2 f(x) ) at the critical point. | Use direct methods for small models; for large models, use matrix-free Lanczos or power iteration to find the minimum eigenvalue [9]. | Local Minimum: ( \lambda{\min} \ge 0 ). Strict Saddle Point: ( \lambda{\min} < 0 ) [10]. |

| Stochastic Perturbation Test | Apply small random perturbations to the converged parameters and resume training. | After convergence at ( x ), set ( x' = x + \xi ), where ( \xi ) is small random noise, and run a few more optimization steps. | Local Minimum: Loss remains stable or increases. Saddle Point: Loss decreases significantly. |

| Curvature Profiling via SGD Noise | Analyze the covariance of the stochastic gradient noise, which can reveal negative curvature directions. | Track the covariance matrix of gradients over multiple mini-batches during the final stages of training. | Anisotropic noise covariance can indicate directions of negative curvature present in the loss landscape. |

Experimental Protocol: Power Iteration for Minimum Eigenvalue

This protocol estimates the minimum eigenvalue of the Hessian for large-scale models where full computation is infeasible [9].

- Initialization: At the converged point ( x ), initialize a random unit vector ( v_0 \in \mathbb{R}^d ). Set the number of iterations ( K ).

- Iteration: For ( k = 1 ) to ( K ):

a. Hessian-vector Product: Compute ( wk = \nabla^2 f(x) v{k-1} ). This can be done efficiently using differential automatic differentiation without constructing the full Hessian matrix (e.g.,

torch.autograd.grad). b. Rayleigh Quotient: Estimate the eigenvalue ( \lambdak = v{k-1}^\top wk ). c. Vector Update: Normalize the vector ( vk = wk / \| wk \| ). - Output: The final estimate for the smallest eigenvalue is ( \lambda_K ). A significantly negative value confirms a strict saddle point.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In high-dimensional optimization, like training neural networks, which is more common: local minima or saddle points?

A: Saddle points are overwhelmingly more common than local minima in high-dimensional spaces [9]. The combinatorial complexity of the curvature in many directions makes it statistically probable that most critical points will have both positive and negative eigenvalues, making them saddle points. True, problematic local minima that trap the optimizer with high loss are considered rare in practice.

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between a local minimum and a saddle point in terms of their impact on gradient-based optimization?

A: The key difference lies in the curvature:

- Local Minimum: The gradient is zero, and the curvature is non-negative in all directions. Small parameter updates will not decrease the loss [9].

- Saddle Point: The gradient is zero, but there is at least one direction of negative curvature. While the gradient signal is flat, moving in the negative curvature direction would decrease the loss. Gradient descent can become very slow here because the gradient magnitude is small [9].

Q3: How does momentum in optimizers like SGD help in escaping saddle points?

A: Momentum helps escape saddle points by accumulating velocity in consistent directions. In a flat region near a saddle point, stochastic gradient noise may provide small, random gradients. Momentum can average these small gradients, building up a velocity vector that is large enough to push the parameters through the flat region and potentially into a direction of descent [9].

Q4: Are saddle points always a bad thing for training?

A: Not necessarily. While they slow down training, being near a saddle point is not inherently harmful if the optimizer can eventually escape it. The main problem is one of efficiency. Furthermore, some research suggests that flat minima (which can be connected to broad saddle regions) might generalize better to new data [9].

Q5: What are some simple, practical signs that my model might be stuck in a saddle point?

A: Key indicators include [9]:

- The training loss stagnates for many iterations without improvement.

- The norm of the gradient becomes very small, close to zero.

- If you then use an optimizer with momentum or temporarily increase the learning rate, the loss suddenly drops, indicating an escape from the stagnant region.

Table 1: Comparison of Gradient-Based Optimization Methods for Non-Convex Problems

This table summarizes the theoretical properties of different algorithms concerning their ability to escape saddle points and converge to a local minimum. "Dimension-free" means the iteration count does not explicitly depend on the problem dimension ( d ).

| Method | Convergence to First-Order Stationary Point | Convergence to Second-Order Stationary Point | Key Mechanism for Escaping Saddles | Theoretical Runtime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Descent (GD) | ( O(\epsilon^{-2}) ) (dimension-free) [10] | Asymptotically, but can take exponential time in worst case [10] | None (gets stuck at saddle points) | ( O(d \cdot \epsilon^{-2}) ) |

| Perturbed GD (PGD) | ( O(\epsilon^{-2}) ) (dimension-free) [10] | ( \tilde{O}(\epsilon^{-2}) ) (dimension-free up to log factors) [10] | Adding uniform noise when gradient is small [10] | ( O(d \cdot \log^4(d) \cdot \epsilon^{-2}) ) |

| SGD with Momentum | Varies with noise | Heuristically faster escape | Historical gradient averaging [9] | No universal guarantee |

| Accelerated Methods (PAGD) | ( O(\epsilon^{-1.75}) ) for some variants [12] | ( \tilde{O}(\epsilon^{-1.75}) ) for some variants [12] | Perturbations and accelerated dynamics [12] [13] | Faster than PGD in certain regimes [12] |

Table 2: Diagnostic Signals for Critical Points

This table helps distinguish the nature of a critical point (where the gradient is zero) based on different analyses.

| Analysis Method | Local Minimum | Strict Saddle Point | Local Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Norm ( |\nabla f(x)| ) | ~ 0 | ~ 0 | ~ 0 |

| Min Eigenvalue of Hessian ( \lambda_{\min}(\nabla^2 f(x)) ) | ( \ge 0 ) | < 0 [10] | < 0 (all eigenvalues) |

| Effect of Small Perturbation | Loss increases or stays the same | Loss can decrease in specific directions | Loss decreases in all directions |

| Behavior with SGD Noise | Parameters oscillate near point | Parameters can drift away from point | Parameters drift away from point |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Analyzing Optimization Landscapes

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Power Iteration / Lanczos Method | Efficiently estimates the dominant (largest or smallest) eigenvalues of the Hessian without explicitly computing the full matrix [9]. | Diagnosing a suspected saddle point by checking for a negative minimum eigenvalue in a large neural network. |

| Automatic Differentiation (AD) | Precisely computes gradients and Hessian-vector products through backward propagation, enabling the implementation of sophisticated optimization algorithms [9]. | Calculating the gradient ( \nabla f(x) ) for a custom loss function or implementing the Hessian-vector product in the power iteration protocol. |

| Perturbed Gradient Descent (PGD) | An optimization algorithm designed to provably escape strict saddle points efficiently by adding controlled noise when the gradient is small [10]. | Training models where convergence to a true local minimum is critical, and saddle points pose a significant slowdown. |

| Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) | An optimization algorithm that uses mini-batches of data to compute noisy gradient estimates. The inherent noise can help escape saddle points [9]. | The standard workhorse for training deep learning models, where its stochastic nature provides a natural mechanism to avoid getting permanently stuck. |

| Momentum-based Optimizers | Optimization methods (e.g., SGD with Momentum, Adam) that accumulate an exponentially decaying average of past gradients to accelerate movement in consistent directions [9]. | Overcoming flat plateaus and saddle regions where the raw gradient is very small but consistent direction exists. |

| 3-Hydroxy Agomelatine | 3-Hydroxy Agomelatine | High Purity Agomelatine Metabolite | 3-Hydroxy Agomelatine, a key metabolite for agomelatine research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Deramciclane fumarate | Deramciclane Fumarate | High-Purity Research Chemical | Deramciclane fumarate for research. Explore its anxiolytic mechanisms & serotonin receptor activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Core Concepts: Saddle Points and Molecular Systems

What is a saddle point in the context of molecular modeling? A saddle point is a critical point on a potential energy surface where the potential energy is neither at a local maximum nor a local minimum. It represents a transition state configuration in a molecular system that can lead to transitions between different stable states, making it fundamentally important for understanding reaction pathways and molecular stability [14].

Why are saddle points problematic for geometry optimization? Saddle points create significant challenges for optimization algorithms because they represent stationary points where the gradient is zero, but the curvature is negative in at least one direction. This means that while the point appears optimal mathematically, it corresponds to an unstable molecular configuration that can drastically alter predicted molecular properties and behaviors [10]. When optimization converges to a saddle point instead of a true minimum, researchers obtain incorrect molecular configurations that don't represent stable structures, compromising the validity of subsequent property predictions and stability analyses.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Symptoms of Saddle Point Convergence

How can I tell if my geometry optimization has converged to a saddle point?

- Flat Learning Curves: The optimization appears to stall with minimal energy improvement over many iterations [10]

- Unphysical Molecular Geometry: The optimized structure shows bond lengths, angles, or torsions that contradict chemical intuition

- Unexpected Symmetry Breaking: The molecular symmetry is unexpectedly broken in the final optimized structure

- Negative Hessian Eigenvalues: Frequency analysis reveals one or more negative eigenvalues in the Hessian matrix [14]

- Discontinuous Forces: Sudden changes in forces during optimization, often related to terms being included or excluded based on cutoff values [15]

What specific errors indicate saddle point problems in ReaxFF calculations? In ReaxFF simulations, saddle point problems often manifest through:

- Discontinuous changes in energy derivatives between optimization steps [15]

- Convergence failures when bond orders cross cutoff thresholds [15]

- Warnings about inconsistent van der Waals parameters in the forcefield [15]

- Suspicious electronegativity equalization method (EEM) parameters that may indicate polarization catastrophes [15]

Solutions and Workarounds

What immediate steps should I take when I suspect saddle point convergence?

- Verify with Frequency Analysis: Always perform vibrational frequency analysis to confirm all eigenvalues are positive [14]

- Apply Targeted Perturbations: Add small random perturbations to molecular coordinates and reoptimize [10]

- Modify Optimization Parameters: Reduce step sizes or change convergence criteria

- Try Different Initial Conditions: Start from alternative molecular configurations

How can I modify ReaxFF parameters to avoid saddle point issues?

- Decrease Bond Order Cutoff: Reduce

Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoffto minimize discontinuities in valence and torsion angles [15] - Use 2013 Torsion Angles: Set

Engine ReaxFF%Torsionsto 2013 for smoother torsion angle behavior at lower bond orders [15] - Enable Bond Order Tapering: Implement tapered bond orders using

Engine ReaxFF%TaperBOto smooth transitions [15] - Validate EEM Parameters: Ensure eta and gamma parameters satisfy η > 7.2γ to prevent polarization catastrophes [15]

Experimental Protocols for Saddle Point Avoidance

Perturbed Gradient Descent Methodology

For nonconvex optimization problems common in molecular modeling, the following perturbed gradient descent (PGD) protocol has proven effective for escaping saddle points [10]:

Algorithm: Perturbed Gradient Descent (PGD)

- Initialize: Start with initial molecular coordinates (x_0)

- Iterate: For (t = 1, 2, \ldots) do:

- Update coordinates: (xt \leftarrow x{t-1} - \eta \nabla f(x_{t-1}))

- Perturbation Condition: If gradient is suitably small, apply perturbation:

- Add uniform noise: (xt \leftarrow xt + \xit) where (\xit) is sampled from a small ball centered at zero

- Terminate: When an (\epsilon)-second-order stationary point is reached [10]

Key Parameters for Molecular Systems:

- Step size ((\eta)): (O(1/\ell)) where (\ell) is the gradient Lipschitz constant [10]

- Perturbation radius: Sufficiently small to maintain physical molecular geometries

- Convergence criteria: (|\nabla f(x)| \le \epsilon) and (\lambda_{\min}(\nabla^2 f(x)) \ge -\sqrt{\rho \epsilon}) [10]

Climbing Multistring Method for Free Energy Surfaces

For mapping free energy surfaces and identifying true minima, the climbing multistring method provides a robust approach [16]:

Workflow Description: This method uses multiple strings (curves in collective variable space) to simultaneously locate multiple saddle points and their connected minima. Dynamic strings evolve to locate new saddles, while static strings preserve already-identified stationary points [16].

Implementation Details:

- String Evolution: Each image on the string updates according to: (γż(α,t) = -M(z(α,t))∇F(z(α,t)) + λ(α,t)z′(α,t)) [16]

- Climbing Condition: The final image uses modified dynamics to climb uphill: (γż(α=1,t) = -M(z(α=1,t))∇F(z(α=1,t)) + ντ(t)τ(t)·M(z(α=1,t))∇F(z(α=1,t))) [16]

- Metric Tensor: (M(z(α))) accounts for collective variable space curvature [16]

- Reparameterization: Ensures equal spacing between images along the string [16]

Quantitative Analysis of Saddle Point Methods

Comparative Performance of Optimization Algorithms

| Method | Convergence Rate | Saddle Point Escape | Dimension Dependence | Computational Cost per Iteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Descent (GD) | (O(1/ε^2)) [10] | No guarantee | Dimension-free [10] | Low ((O(d))) [10] |

| Perturbed GD (PGD) | (\tilde{O}(1/ε^2)) [10] | Provably efficient | (\log^4(d)) [10] | Low ((O(d))) |

| Hessian-based Methods | (O(1/ε^{1.5})) | Excellent | Exponential | High ((O(d^2))+) |

| Climbing Multistring | Problem-dependent | Designed specifically for | Depends on CV choice | Moderate (scales with images) |

Saddle Point Classification by Hessian Eigenvalues

| Stationary Point Type | (\lambda_{\min}(\nabla^2 f(x))) | Stability | Molecular Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Minimum | > 0 | Stable | Stable molecular configuration |

| Saddle Point | < 0 | Unstable | Transition state between minima |

| Non-strict Saddle Point | = 0 | Meta-stable | Shallow potential region |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Computational Methods for Saddle Point Management

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Analysis | Verify minimum through Hessian eigenvalues | Post-optimization validation |

| Perturbed Gradient Descent | Escape strict saddle points with negligible overhead [10] | General nonconvex optimization |

| Climbing Multistring Method | Locate all saddles and pathways on free energy surfaces [16] | High-dimensional CV spaces |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) | Find minimum energy paths between known minima [16] | Reaction pathway identification |

| Eigenvector Following | Locate transition states from single-ended search [16] | Unknown reaction discovery |

| Hessian-based Stochastic ART | Map minima and saddle points on high-dimensional FES [16] | Complex systems with entropic contributions |

| 2,6-Difluorophenylboronic acid | 2,6-Difluorophenylboronic Acid | High-Purity Reagent | High-purity 2,6-Difluorophenylboronic acid for Suzuki cross-coupling. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 6-Chloro-3-indoxyl butyrate | 6-Chloro-3-indoxyl butyrate | High-Purity Substrate | 6-Chloro-3-indoxyl butyrate is a chromogenic substrate for esterase detection in histochemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't optimization algorithms naturally avoid saddle points? Traditional gradient-based methods move downhill in all directions, which works perfectly for convex problems. However, at saddle points, the gradient is zero in all directions, giving the algorithm no directional information to escape. While saddle points are unstable in at least one direction, the flat curvature makes identifying this direction challenging without second-order information or deliberate perturbations [10].

Are some molecular systems more prone to saddle point problems? Yes, systems with shallow potential energy surfaces, multiple conformational states, or nearly degenerate energy minima are particularly susceptible. Flexible molecules with multiple rotatable bonds, systems with competing non-covalent interactions, and materials near phase transitions often exhibit complex energy landscapes with numerous saddle points [16].

How does the choice of collective variables affect saddle point identification? The selection of collective variables (CVs) is crucial for effective saddle point navigation. Ideal CVs should represent the true slow modes of the system and properly distinguish between different macroscopic configurations. Poor CV choice can create artificial saddle points or mask real ones, leading to incorrect mechanistic interpretations [16].

What is the practical impact of saddle point convergence on drug development? In drug development, saddle point convergence can lead to incorrect binding pose predictions, inaccurate protein-ligand interaction energies, and flawed stability assessments of drug candidates. These errors propagate through the design process, potentially leading to failed synthetic efforts or poor experimental performance of predicted compounds [15].

Can machine learning approaches help with saddle point problems? Emerging approaches combine traditional optimization with machine learning. For instance, the Hessian-based stochastic activation-relaxation technique (START) combines machine learning optimization with the ART approach to map minima and saddle points on high-dimensional free energy surfaces [16]. These methods show promise for complex systems where traditional methods struggle.

The Prevalence of Saddle Points in High-Dimensional Chemical Spaces of Drug-like Molecules

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my molecular geometry optimization keep converging to a saddle point?

Your optimization is likely converging to a saddle point because high-dimensional chemical spaces of drug-like molecules are inherently complex and filled with numerous saddle points [13] [17]. First-order optimizers like L-BFGS and FIRE, which rely solely on gradient information, cannot distinguish between minima and saddle points, as both have near-zero gradients [17]. This is particularly problematic when using Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) as replacements for DFT calculations, as some NNP-optimizer combinations have been shown to yield structures with imaginary frequencies, confirming saddle point convergence [18].

2. What is the most reliable optimizer for avoiding saddle points in drug-like molecule optimization?

Based on recent benchmarks, the choice of optimizer significantly impacts success rates. For drug-like molecules, the Sella optimizer with internal coordinates has demonstrated excellent performance, successfully optimizing 20-25 out of 25 test molecules across different NNPs and finding true local minima in 15-24 cases [18]. The L-BFGS optimizer also shows reasonable performance, successfully optimizing 22-25 molecules, though it finds fewer true minima (16-21 out of 25) [18]. The geomeTRIC optimizer with Cartesian coordinates performs poorly, successfully optimizing only 7-12 molecules across different NNPs [18].

3. How can I verify if my optimized geometry is a true minimum or a saddle point?

You can verify the nature of your stationary point by performing a frequency calculation [18] [2]. A true local minimum will have zero imaginary frequencies, while a saddle point will have one or more imaginary frequencies [18]. The AMS software package includes PES (Potential Energy Surface) point characterization, which automatically calculates the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to determine the type of stationary point found [2]. For a rigorous result, ensure your convergence criteria for the geometry optimization are sufficiently tight, particularly the gradient threshold [2].

4. What convergence criteria should I use for reliable geometry optimizations?

The AMS documentation recommends multiple convergence criteria for a robust optimization [2]. A geometry optimization is considered converged when: the energy change between steps is smaller than the Energy threshold times the number of atoms; the maximum Cartesian nuclear gradient is smaller than the Gradients threshold; the RMS of the gradients is smaller than 2/3 of the Gradients threshold; the maximum Cartesian step is smaller than the Step threshold; and the RMS of the steps is smaller than 2/3 of the Step threshold [2]. The Quality setting provides a convenient way to adjust all thresholds simultaneously, with 'Good' and 'VeryGood' providing tighter convergence [2].

5. My optimization will not converge. What troubleshooting steps should I take?

First, check if the issue is related to the optimizer and potential energy surface combination. Recent benchmarks show that certain NNP-optimizer pairs have high failure rates [18]. Consider switching to a more robust optimizer like Sella (internal coordinates) or L-BFGS [18]. Second, ensure your convergence criteria are appropriate - very tight criteria may require an excessively large number of steps, while loose criteria may not reach a minimum [2]. Third, verify that the numerical accuracy of your computational method (e.g., DFT functional, basis set, or NNP) is sufficient for geometry optimization, as noisy gradients can prevent convergence [2]. Finally, consider enabling automatic restarts in your optimization software, which can help if the optimization converges to a saddle point [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Consistently Converges to Saddle Points

Symptoms: Frequency calculations reveal imaginary frequencies after optimization; optimization history shows oscillatory behavior; multiple starting structures converge to the same saddle point.

Solution Protocol:

- Enable Automatic Restarts: Configure your optimization software to automatically restart when a saddle point is detected. In AMS, this requires setting

MaxRestartsto a value >0, disabling symmetry withUseSymmetry False, and enabling PES point characterization in the Properties block [2]. - Implement Occupation-Time Adapted Perturbations: Use advanced optimization algorithms like Perturbed Gradient Descent Adapted to Occupation Time (PGDOT) or its accelerated version (PAGDOT), which are specifically designed to avoid getting stuck at non-degenerate saddle points [13].

- Apply Dimer-Enhanced Optimization: For neural network potentials, implement Dimer-Enhanced Optimization (DEO), which uses two closely spaced points to probe local curvature and approximate the Hessian's smallest eigenvector, effectively guiding the optimizer away from saddle points [17].

- Optimizer Comparison: Test multiple optimizers with your specific system. Benchmarking studies show significant variation in saddle point avoidance between different optimizer-NNP combinations [18].

Verification: After implementing these solutions, perform a frequency calculation to confirm the absence of imaginary frequencies, indicating a true local minimum has been found [18].

Problem: Molecular Optimization Fails to Converge Within Step Limit

Symptoms: Optimization exceeds maximum step count (typically 250 steps); oscillating energy values; slow or no progress in reducing gradients.

Solution Protocol:

- Optimizer Selection: Switch to an optimizer with better convergence properties for your specific molecular system. Recent benchmarks show Sella with internal coordinates requires significantly fewer steps (13.8-23.3 on average) compared to geomeTRIC with Cartesian coordinates (158.7-195.6 steps on average) [18].

- Adjust Convergence Criteria: Loosen convergence criteria temporarily to achieve initial convergence, then refine with tighter criteria. Use the

Qualitysetting in AMS to quickly switch between 'Basic', 'Normal', or 'Good' convergence levels [2]. - Coordinate System Change: Implement optimization in internal coordinates rather than Cartesian coordinates, as this can significantly reduce the number of steps required for convergence [18].

- Gradient Accuracy Check: Verify the numerical accuracy of gradients from your computational method, as noisy gradients can prevent convergence even with appropriate optimizers [2].

Verification: Monitor the optimization progress, ensuring steady reduction in both energy and gradient norms. The optimization should converge within the step limit with appropriate settings.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Benchmarking Protocol for Optimizer Performance Assessment

Objective: Compare the performance of different geometry optimizers on drug-like molecules to identify the most effective methods for avoiding saddle points.

Materials:

- Set of 25 drug-like molecules with known conformational complexity [18]

- Multiple neural network potentials (OrbMol, OMol25 eSEN, AIMNet2, Egret-1) [18]

- GFN2-xTB method as control [18]

- Optimization software supporting multiple algorithms (Sella, geomeTRIC, FIRE, L-BFGS) [18]

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Obtain or generate initial coordinates for all 25 test molecules, ensuring diversity in size, flexibility, and functional groups [18].

- Optimizer Configuration: Set up each optimizer with consistent convergence criteria: maximum force threshold of 0.01 eV/Ã… (0.231 kcal/mol/Ã…) and maximum of 250 steps [18].

- Execution: Run geometry optimizations for all molecule-optimizer-NNP combinations.

- Analysis: For each completed optimization:

- Record the number of steps to convergence

- Perform frequency calculation to identify imaginary frequencies

- Classify the stationary point as minimum or saddle point

- Performance Metrics Calculation: Determine for each optimizer-NNP pair:

- Percentage of successful optimizations (converged within step limit)

- Average number of steps for successful optimizations

- Percentage of optimized structures that are true minima (zero imaginary frequencies)

- Average number of imaginary frequencies for optimized structures

Expected Outcomes: Quantitative comparison of optimizer performance identifying the most effective algorithms for avoiding saddle points in high-dimensional chemical spaces of drug-like molecules.

Quantitative Comparison of Optimizer Performance with Neural Network Potentials

Table 1: Success Rates of Different Optimizers with Various NNPs (out of 25 drug-like molecules)

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 22 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 24 |

| ASE/FIRE | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Sella | 15 | 24 | 25 | 15 | 25 |

| Sella (internal) | 20 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 25 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 8 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 9 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 25 |

Source: Adapted from Rowan Scientific benchmarking study [18]

Table 2: Quality of Optimization Results (Structures with Zero Imaginary Frequencies)

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 16 | 16 | 21 | 18 | 20 |

| ASE/FIRE | 15 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 12 |

| Sella | 11 | 17 | 21 | 8 | 17 |

| Sella (internal) | 15 | 24 | 21 | 17 | 23 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 6 | 8 | 22 | 5 | 7 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 17 | 13 | 1 | 23 |

Source: Adapted from Rowan Scientific benchmarking study [18]

Table 3: Average Steps to Convergence for Successful Optimizations

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 108.8 | 99.9 | 1.2 | 112.2 | 120.0 |

| ASE/FIRE | 109.4 | 105.0 | 1.5 | 112.6 | 159.3 |

| Sella | 73.1 | 106.5 | 12.9 | 87.1 | 108.0 |

| Sella (internal) | 23.3 | 14.9 | 1.2 | 16.0 | 13.8 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 182.1 | 158.7 | 13.6 | 175.9 | 195.6 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 11.0 | 114.1 | 49.7 | 13.0 | 103.5 |

Source: Adapted from Rowan Scientific benchmarking study [18]

Advanced Saddle Point Escape Protocol

Objective: Implement and validate advanced optimization algorithms specifically designed to escape saddle points in high-dimensional chemical spaces.

Materials:

- PGDOT (Perturbed Gradient Descent Adapted to Occupation Time) algorithm [13]

- PAGDOT (Perturbed Accelerated Gradient Descent Adapted to Occupation Time) algorithm [13]

- DEO (Dimer-Enhanced Optimization) framework [17]

- Test molecules with known saddle point convergence issues

Methodology:

- Algorithm Implementation: Implement or access available code for PGDOT, PAGDOT, and DEO algorithms.

- Baseline Establishment: Run standard optimizers (L-BFGS, FIRE) on test molecules to establish baseline performance and identify saddle point convergence.

- Advanced Algorithm Application: Apply PGDOT, PAGDOT, and DEO to the same test molecules with identical starting conditions.

- Performance Comparison: Compare convergence rates, success in finding true minima, and computational cost between standard and advanced algorithms.

- Hessian Analysis: Perform full Hessian calculations on resulting structures to confirm stationary point character.

Expected Outcomes: Demonstration of improved saddle point escape capabilities with advanced algorithms, providing practical solutions for challenging optimization problems in drug-like molecule geometry optimization.

Optimization Workflows and Pathways

Optimization Workflow with Saddle Point Handling

Saddle Point Challenges in Chemical Space

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Replace DFT calculations for faster geometry optimizations [18] | OrbMol, OMol25 eSEN, AIMNet2, and Egret-1 show varying performance with different optimizers; benchmark for your specific system [18] |

| Sella Optimizer | Geometry optimization using internal coordinates with rational function optimization [18] | Demonstrates excellent performance for drug-like molecules, particularly with internal coordinates (20-25/25 successes) [18] |

| geomeTRIC Library | Optimization using translation-rotation internal coordinates (TRIC) [18] | Performance varies significantly between Cartesian (poor) and TRIC coordinates (good for some NNPs); requires testing [18] |

| L-BFGS Algorithm | Quasi-Newton optimization method using gradient information [18] | Reliable performance across multiple NNPs (22-25/25 successes) though finds fewer true minima than Sella with internal coordinates [18] |

| PESPoint Characterization | Automated stationary point identification via Hessian eigenvalue calculation [2] | Critical for distinguishing true minima from saddle points; enables automatic restart from saddle points [2] |

| PGDOT/PAGDOT Algorithms | Occupation-time adapted optimization for escaping saddle points [13] | Uses self-repelling random walk principles to avoid non-degenerate saddle points; enhances convergence to true minima [13] |

| Dimer-Enhanced Optimization (DEO) | First-order curvature estimation for saddle point escape [17] | Adapts molecular dynamics Dimer method to neural network training; approximates Hessian's smallest eigenvector without full computation [17] |

| Automatic Restart Framework | Automated reoptimization from displaced geometry after saddle point detection [2] | Requires disabled symmetry and PES point characterization; configurable displacement size and maximum restarts [2] |

| DL-Methionine methylsulfonium chloride | DL-Methionine methylsulfonium chloride | High Purity | DL-Methionine methylsulfonium chloride for research. A key methyl donor precursor. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Hydroquinidine hydrochloride | Hydroquinidine Hydrochloride | High-Purity Reagent | Hydroquinidine hydrochloride is a high-purity alkaloid for electrophysiology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Escaping the Trap: Methodologies for Robust Convergence to True Minima

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My geometry optimization converged, but the calculation warns it found a transition state. What does this mean and what should I do? You have likely converged to a saddle point on the potential energy surface (PES), not a minimum. A transition state is characterized by one imaginary frequency (negative eigenvalue in the Hessian matrix) [19]. You should enable the automated restart mechanism. This feature will displace your geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode and restart the optimization, guiding it toward a true minimum [2].

Q2: I've enabled PESPointCharacter and MaxRestarts, but the automatic restart never happens. Why?

The most common reason is that your system has symmetry. The automatic restart mechanism requires symmetry to be disabled to apply effective, symmetry-breaking displacements. Ensure your input includes UseSymmetry False [2]. Additionally, verify that the PESPointCharacter property is set to True within the Properties block, not just the GeometryOptimization block.

Q3: How large is the geometry displacement applied during a restart, and can I control it?

The default displacement for the furthest moving atom is 0.05 Ã… [2]. You can adjust this using the RestartDisplacement keyword in the GeometryOptimization block. A larger value may help escape shallow saddle points but risks moving the geometry too far from the desired minimum.

Q4: What are the specific convergence criteria that define a "converged" optimization? For a geometry optimization to be considered converged, several conditions must be met simultaneously [2]. The following table summarizes the key criteria:

| Criterion | Description | Typical Default Value |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | Change in total energy between steps | < 1.0e-05 Ha × (Number of atoms) [2] |

| Maximum Gradient | Largest force on any nucleus | < 0.001 Ha/Ã… [2] |

| RMS Gradient | Root-mean-square of all nuclear forces | < (2/3) × 0.001 Ha/Å [2] |

| Maximum Step | Largest displacement of any nucleus | < 0.01 Ã… [2] |

| RMS Step | Root-mean-square of all nuclear displacements | < (2/3) × 0.01 Å [2] |

Q5: How do I configure a calculation for multiple automatic restarts?

Use the input block structure shown below. The MaxRestarts keyword is crucial for activating the mechanism [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Consistently Converges to the Wrong Transition State Issue: The automatic restart displaces the geometry but keeps finding a saddle point, often a higher-order one (with more than one imaginary frequency). Solution:

- Tighten Convergence: Use stricter convergence criteria (e.g.,

Convergence%Quality Good) to ensure the optimization does not stop prematurely [2]. - Adjust Initial Guess: The initial geometry may be too close to the saddle point region. Generate a new initial guess using methods like coordinate driving or nudged elastic band [19].

- Manual Intervention: After a failed restart, manually displace the final geometry along a different normal mode before starting a new optimization.

Problem: Optimization Cycle is Stuck or Taking Too Long Issue: The calculation is performing many restarts without making progress. Solution:

- Check Maximum Iterations: Review the

MaxIterationssetting. The default is a large number, but if it's set too low, the optimization may not have enough steps to converge after a restart [2]. - Review Trust Radius: In some software, the trust radius controls the maximum step size. If it's too small, convergence can be slow. For transition state searches, it is often recommended to use a smaller trust radius (e.g., 0.1) compared to minimizations [3].

- Inspect Intermediate Results: Enable

KeepIntermediateResults Yesto save all intermediate steps. Analyzing these can reveal if the geometry is oscillating between states [2].

Problem: "Hessian Eigenvalue Error" or "PES Point Characterization Failed" Issue: The calculation of the Hessian matrix or its eigenvalues failed, preventing the PES point characterization. Solution:

- Improve Numerical Accuracy: For some computational engines, you may need to increase the numerical accuracy (e.g., using a

NumericalQualitykeyword) to generate noise-free gradients, which is essential for a stable Hessian calculation [2]. - Provide an External Hessian: If you have a pre-computed Hessian matrix from a previous calculation, you can provide it as input to skip the initial finite difference calculation [19].

- Simplify the System: If the system is very large or flexible, consider using a smaller model system or applying constraints to stabilize the initial optimization.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Automated Restart

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for setting up a geometry optimization with an automated restart mechanism to escape transition states, based on the functionality in the AMS package [2].

1. Define the System and Basic Task

Start with a standard System block defining your molecular coordinates and a Task for geometry optimization.

2. Configure the GeometryOptimization Block This is the core of the setup. The key is to explicitly request multiple restarts.

3. Disable Symmetry and Request PES Point Characterization The restart requires symmetry to be off and needs the properties block to analyze the result.

4. Execute and Monitor the Calculation Run the job and monitor the output log. A successful activation of the restart mechanism will produce messages indicating that a transition state was found and a restart is being initiated with a displacement along the imaginary mode.

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow of the automated restart mechanism.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key software components and their functions for implementing automated restart mechanisms in computational chemistry experiments.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| PES Point Characterization | A computational "assay" that calculates the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to determine if a structure is a minimum (all positive eigenvalues) or a transition state (one imaginary frequency) [2] [19]. |

| Hessian Matrix | The matrix of second derivatives of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates. Its diagonalization provides the vibrational frequencies essential for characterizing the stationary point [19]. |

| Geometry Optimizer | The algorithm (e.g., Quasi-Newton, L-BFGS) that iteratively adjusts nuclear coordinates to minimize the system's energy, driving it toward a stationary point on the PES [2] [3]. |

| Symmetry Detection | A function that identifies point group symmetry in a molecule. It must be disabled (UseSymmetry False) for the automatic restart to apply effective, symmetry-breaking displacements [2]. |

| Internal Coordinates | A coordinate system (e.g., bonds, angles, dihedrals) used by the optimizer. Its proper setup is critical for efficient optimization, especially when bonds are forming/breaking near a transition state [19]. |

Noisy Gradient Descent to Actively Evade Saddle Regions

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My optimization consistently stalls, showing minimal progress in loss reduction. How can I determine if I am stuck at a saddle point?

A: Stalling convergence often indicates a saddle point issue, common in high-dimensional non-convex problems like geometry optimization. To diagnose this, follow these steps [20]:

- Gradient Norm Analysis: Compute the norm of your gradient vector. At a saddle point, the gradient will be very close to zero, mimicking a true local minimum. Use this in your code to monitor during training.

- Hessian Eigenvalue Calculation: Compute the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix of your loss function with respect to the parameters. If most eigenvalues are positive, you are likely in a convex region. The presence of one or more significant negative eigenvalues confirms a saddle point [20].

- Perturbation Test: Apply a small random perturbation to your parameter vector. If the optimization escapes the region and the loss decreases, you were likely at a saddle point. This is the core idea behind stochastic gradient descent and many evasion strategies.

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Tool: Use an automatic differentiation framework (e.g., JAX, PyTorch) that can compute Hessian-vector products efficiently.

- Procedure:

- When training stalls, save the current model parameters.

- Calculate the gradient norm; a value near zero suggests a critical point.

- Compute the top 5-10 eigenvalues of the Hessian using a power iteration or Lanczos method.

- If negative eigenvalues are found, inject noise (see Q3 for protocols) and observe the loss trajectory.

Q2: How do I differentiate between a saddle point and a local minimum?

A: The key differentiator is the curvature of the loss function, determined by the Hessian matrix [20].

| Feature | Local Minimum | Saddle Point |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient | Zero | Zero |

| Hessian Eigenvalues | All positive | Mixed positive and negative |

| Loss Behavior | Increases in all directions | Decreases in at least one direction |

Diagnostic Methodology: Implement the following checks when your gradient norm is near zero:

- Hessian Analysis: As outlined in Q1, the eigenvalue spectrum of the Hessian provides a definitive diagnosis. A local minimum will have a positive semi-definite Hessian (all eigenvalues ≥ 0), while a saddle point will have an indefinite Hessian [20].

- Random Direction Exploration: Sample a random direction

vand compute the finite difference for a small stepε:(L(θ + εv) - L(θ - εv)) / (2ε). If this value is negative for some directions, it indicates the presence of a downward curvature, characteristic of a saddle point.

Q3: My model training is slow and unstable after adding noise. How can I tune the noise parameters effectively?

A: Ineffective noise scheduling is a common cause of instability. Noise should be adaptive, based on the gradient history, rather than constant. Below is a structured comparison of noise injection strategies and a tuning protocol [21].

Quantitative Comparison of Perturbation Strategies:

| Strategy | Noise Type | Key Parameters | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SGD with Momentum | Gradient-dependent stochasticity | Learning Rate (η), Momentum (β) | General evasion of shallow saddles |

| Annealed Gaussian Noise | Decreasing Gaussian noise | Initial Noise Scale (σ₀), Decay Rate | Controlled exploration in later training |

| Gradient Noise Scale | Adaptive noise proportional to gradient norm | Threshold (Ï„), Clipping Value (C) | High-variance, complex loss landscapes |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Tuning: This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for integrating and optimizing annealed Gaussian noise.

- Establish a Baseline: Begin with a simple architecture and a relatively high learning rate without any added noise. Ensure your model can overfit a small, single batch of data. This verifies that your model is capable of learning and that the initial code is correct [20].

- Initial Noise Introduction: Start with a very small noise standard deviation (e.g., σ = 0.001). Apply this noise to the gradients or parameters at each update step.

- Monitor and Adjust:

- If the optimizer remains stuck, gradually increase the noise scale (e.g., by a factor of 1.5) until you observe an escape from the plateau.

- If training becomes unstable (loss explodes or oscillates wildly), reduce the noise scale and/or lower the learning rate [20].

- Implement Annealing: Once a stable escape noise level is found, introduce a decay schedule (e.g., exponential decay) to reduce the noise over time, allowing for finer convergence as the optimizer settles into a promising region.

Q4: I am getting NaN or Inf values in my loss after implementing gradient perturbations. What is the cause and solution?

A: Numerical instability from perturbation is a common bug, often related to an incorrectly scaled noise distribution or unstable operations [20].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Gradient Clipping: Implement gradient clipping (e.g., clip by norm or value) before adding noise. This prevents excessively large gradients from combining with noise to produce numerical overflows.

- Noise Scaling: Ensure your noise is scaled appropriately relative to your gradient norms. A good heuristic is to set the noise standard deviation to be a small fraction (e.g., 0.1% to 1%) of the average gradient norm.

- Debugging Workflow: Follow a systematic debugging workflow to isolate the issue.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common invisible bugs when implementing noisy gradient descent?

A: The most common and invisible bugs include [20]:

- Incorrect Random Seed or Stream Management: This leads to non-reproducible results and can accidentally couple noise across parameters or steps.

- Silent Shape Misalignment: When adding noise to parameters or gradients, a shape mismatch may cause broadcasting instead of an error, applying noise incorrectly.

- Forgotten Gradient Zeroing: In frameworks like PyTorch, failing to zero the gradients before the backward pass causes gradients from previous steps to accumulate, compounding with the noise incorrectly.

Q2: How does the problem of saddle points specifically impact geometry optimization in drug development?

A: In drug development, molecular geometry optimization aims to find stable low-energy configurations (conformers). The energy landscape is riddled with saddle points that correspond to transition states between stable conformers [21]. Convergence to a saddle point, rather than a true minimum, results in:

- An incorrect prediction of a molecule's stable shape.

- Flawed calculation of its binding affinity to a target protein.

- Ultimately, the failure of in-silico drug design campaigns due to inaccurate models.

Q3: Beyond adding noise, what are other effective strategies to avoid saddle points?

A: Several other strategies can be employed, often in combination with noise injection:

- Using Adaptive Learning Rate Optimizers: Methods like Adam or RMSProp inherently use a form of noise and momentum, which helps navigate flat regions and escape saddle points faster than vanilla SGD.

- Momentum: The historical average of gradients in momentum-based methods helps the optimizer build up speed to travel through flat regions and push past saddle points.

- Stochastic Weight Averaging (SWA): This technique averages multiple points along the optimization trajectory, which can smooth the path and yield a final parameter set that resides in a wider, more robust basin of attraction.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Perturbation Experiments:

| Item | Function | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Automatic Differentiation Framework | Enables efficient computation of gradients and Hessian-vector products for diagnostics and optimization. | PyTorch (with torch.optim), JAX (with jax.grad and jax.hessian) [20] |

| Eigenvalue Computation Library | Calculates the top eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix to diagnose saddle points. | SciPy (scipy.sparse.linalg.eigsh), PyTorch (LobPCG via torch.lobpcg) [20] |

| Parameter Perturbation Module | Injects structured noise into parameters or gradients according to a defined schedule. | Custom class implementing Gaussian noise with exponential decay. |

| Learning Rate Scheduler | Dynamically adjusts the learning rate in concert with noise for stable training. | PyTorch's torch.optim.lr_scheduler.StepLR or CosineAnnealingLR |

| Gradient Clipping Function | Prevents exploding gradients by clipping their norms, crucial for stability when using noise. | torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_ [20] |

| Visualization Toolkit | Plots loss landscapes, gradient norms, and eigenvalue spectra to monitor optimization behavior. | Matplotlib, Plotly |

| Trimethylsilyl-meso-inositol | Trimethylsilyl-meso-inositol | Trimethylsilyl-meso-inositol (C24H60O6Si6) is a high-purity derivative for GC-MS research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 4-(2-(Piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)benzaldehyde | 4-(2-(Piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)benzaldehyde | 4-(2-(Piperidin-1-yl)ethoxy)benzaldehyde is a key reagent for synthesizing active compounds in cancer and Alzheimer's research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary cause of convergence to saddle points in geometry optimization, and how can Active Learning help?

Convergence to saddle points is a fundamental challenge when using intensive energy functions for calculating transition states in computational chemistry. Traditional methods require evaluating the gradients of the energy function at a vast number of locations, which is computationally expensive. Active Learning (AL) addresses this by implementing a statistical surrogate model, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), for the energy function. This surrogate model is combined with saddle-point search dynamics like Gentlest Ascent Dynamics (GAD). An active learning framework sequentially designs the most informative locations and takes evaluations of the original model at these points to train the GPR, significantly reducing the number of expensive energy or force evaluations required and helping to avoid premature convergence to saddle points [22] [23].

Q2: My model is stuck in a cycle of exploring chemically invalid molecules. How can I refine the generation process?

This issue often arises when the generative component of the workflow is not sufficiently constrained by chemical knowledge. Implement a two-tiered active learning cycle with chemoinformatic and molecular modeling oracles. The inner AL cycle should use chemoinformatics predictors (drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility filters) to evaluate generated molecules. Only molecules passing these filters are used to fine-tune the model (e.g., a Variational Autoencoder). The outer AL cycle should then apply more computationally intensive, physics-based oracles (like molecular docking) to the accumulated, chemically valid molecules. This structure ensures that exploration is guided towards regions of chemical space that are both valid and have high potential for target engagement [24].

Q3: How do I balance exploration and exploitation in my Active Learning protocol for virtual screening?

The optimal balance depends on your goal: discovery of novel scaffolds (exploration) versus optimization of known leads (exploitation). Benchmarking studies suggest the following:

- For initial batches, use a larger batch size with an exploration-focused strategy (e.g., selecting diverse, representative samples) to build a robust initial model, especially when dealing with a diverse chemical space [25].

- For subsequent cycles, switch to smaller batch sizes (e.g., 20-30 compounds) and can incorporate more exploitative strategies (e.g., greedy selection based on predicted affinity) to efficiently identify top binders [25].

- Model Choice: Gaussian Process (GP) models often outperform others like Chemprop when training data is sparse, making them suitable for early-stage exploration. Both models can achieve comparable performance in identifying top binders when more data is available [25].

Q4: What is the impact of noisy data (e.g., from docking scores) on my Active Learning campaign?

AL protocols can be robust to a certain level of stochastic noise. Studies show that adding artificial Gaussian noise up to a specific threshold (around 1 standard deviation of the affinity distribution) still allows the model to identify clusters of top-scoring compounds. However, excessive noise can significantly degrade the model's predictive performance and its ability to exploit the chemical space to find the most potent binders. It is crucial to characterize the error of your labeling method (e.g., docking, RBFE) and account for it in your AL design [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance and Failure to Identify Top Binders

Problem: Your AL model is not identifying high-affinity compounds, or its overall predictive power is low.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or non-representative initial data | Check the diversity of your initial batch. Analyze if it covers the major clusters of your chemical space using methods like UMAP. | Increase the size of the initial training batch. Use a diversity-based or exploration-focused sampling method for the initial batch selection to ensure better coverage of the chemical space [25]. |

| Excessive noise in the labeling oracle | Quantify the uncertainty or error associated with your affinity predictions (docking, RBFE). | If noise is high, consider using a model like Gaussian Process regression that naturally handles uncertainty. You may also need to increase batch sizes to average out stochastic errors [25]. |

| Incorrect batch size | Evaluate the recall of top binders after each AL cycle. | For the initial batch, use a larger size. For subsequent cycles, smaller batch sizes (20-30) are often more effective for precise exploitation [25]. |

Issue 2: Computational Bottleneck in High-Dimensional Saddle Point Search

Problem: The calculation of saddle points (transition states) is prohibitively slow due to the high cost of evaluating the true energy function and its derivatives.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent calls to the ab initio or force field calculator | Profile your code to count the number of energy and gradient evaluations. | Implement an Active Learning framework. Use a Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) surrogate model to approximate the energy function. Employ an optimal experimental design criterion to selectively query the true, expensive model only at the most informative points, drastically reducing the number of required evaluations [22] [23]. |

| Inefficient saddle point dynamics | Check if the dynamics method (e.g., GAD) is effectively using surrogate gradient and Hessian information. | Combine the GPR surrogate with a single-walker dynamics method like Gentlest Ascent Dynamics (GAD). The GAD can be applied to the GPR surrogate to locate saddle points efficiently without constant recourse to the original model [22] [23]. |

Workflow for Saddle Point Calculation with Active Learning

The following diagram illustrates the iterative AL cycle for efficiently finding saddle points, which helps overcome convergence issues in geometry optimization.

Workflow for Drug Design with Nested Active Learning

This diagram details the nested AL cycles used in generative AI workflows for drug design, ensuring the creation of valid, high-affinity molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists key computational methods and their roles in developing and deploying Active Learning protocols for optimization and drug discovery.

| Research Reagent / Method | Function in Active Learning Protocol |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A surrogate model used to approximate the expensive-to-evaluate energy function or property predictor. It provides a mean prediction and an uncertainty estimate, which is crucial for selecting the most informative subsequent samples [22] [25] [23]. |

| Gentlest Ascent Dynamics (GAD) | A single-walker dynamics method applied to the surrogate model (e.g., GPR) to locate saddle points on the potential energy surface without the constant need for the true, expensive model [22] [23]. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | A generative model that learns a continuous, lower-dimensional latent representation of molecular structures. It can be sampled to propose novel molecules and is efficiently fine-tuned within AL cycles [24]. |

| Molecular Docking | A physics-based oracle used in the outer AL cycle to predict the binding pose and affinity of a generated molecule against a protein target. It provides a critical filter for target engagement [24]. |

| PELE (Protein Energy Landscape Exploration) | An advanced simulation method used for candidate selection after AL cycles. It provides an in-depth evaluation of binding interactions and stability within protein-ligand complexes by exploring the energy landscape [24]. |

| Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) Simulations | A high-accuracy, computationally intensive method used to validate the binding affinity of final candidate molecules identified through the AL pipeline, providing strong confidence before experimental synthesis [24]. |

| Carbethopendecinium bromide | Septonex (Carbethopendecinium Bromide) for Research |

| (1R)-Chrysanthemolactone | (1R)-Chrysanthemolactone, CAS:14087-70-8, MF:C10H16O2, MW:168.23 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between optimizing nuclear coordinates and optimizing lattice parameters?

Optimizing nuclear coordinates and optimizing lattice parameters are two distinct processes. Minimizing energy with respect to nuclear coordinates determines how atoms and molecules are arranged within a given, fixed crystallographic cell. In contrast, minimizing with respect to lattice parameters (often alongside nuclear coordinates) is used to find the most stable unit cell shape and size for a solid material, which can reveal different crystallographic phases. The choice between them is not about computational advantage but depends entirely on your research goal: whether you are studying atomic arrangement within a known cell or predicting the stable crystal structure itself [26].

FAQ 2: My geometry optimization converged to a saddle point. What should I do?

Your optimization may have found a transition state instead of a local minimum. Modern computational software offers an automatic restart feature for this specific issue. When enabled, if the optimization converges to a saddle point (a structure with imaginary vibrational frequencies), the calculation can automatically restart. It does this by applying a small displacement to the geometry along the direction of the imaginary mode and beginning a new optimization. This symmetry-breaking displacement often guides the system away from the saddle point and toward a true energy minimum [2].

FAQ 3: What are the standard convergence criteria for a geometry optimization, and when should I tighten them?

A geometry optimization is considered converged when several conditions are met simultaneously. The standard (Normal) convergence thresholds in typical software are [2]:

- Energy change: < 10â»âµ Hartree per atom

- Maximum nuclear gradient: < 0.001 Hartree/Ã…ngstrom

- Maximum nuclear step: < 0.01 Ã…ngstrom

Tightening these criteria (e.g., to "Good" or "VeryGood" settings) is recommended when you require highly precise geometries or when performing frequency calculations, as these require the structure to be very close to a true minimum. However, it is good practice to first consider the objectives of your calculation, as stricter criteria will require more computational time and resources [2].

FAQ 4: How can I simultaneously optimize both atomic positions and the unit cell for a periodic system?

To perform a full optimization of a periodic system, you must explicitly enable the lattice optimization feature in your computational software. This instructs the optimizer to vary not only the nuclear coordinates but also the lattice vectors (the cell's size and shape) to minimize the total energy of the system. This is a standard option in many quantum chemistry packages and is crucial for predicting accurate equilibrium structures of crystalline materials from first principles [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Geometry Optimization Failing to Converge

Problem: The optimization exceeds the maximum number of iterations without meeting the convergence criteria.

Solution:

- Verify Initial Geometry: Ensure your starting structure is reasonable and does not contain severely strained bonds or atomic clashes.

- Adjust Convergence Criteria: If the system is large or the potential energy surface is complex, consider using slightly looser convergence criteria (e.g., "Basic" quality) to achieve initial convergence, then refine with tighter settings [2].

- Check Gradient Accuracy: For tight convergence criteria, ensure the computational engine (e.g., the density functional theory code) is configured for high numerical accuracy in its gradient calculations [2].

Issue 2: Convergence to a Saddle Point Instead of a Minimum

Problem: The optimization completes, but a subsequent frequency calculation reveals imaginary frequencies, indicating a transition state structure.

Solution:

- Enable Automatic Restarts: Configure your calculation to allow for automatic restarts (

MaxRestarts > 0) and enable PES (Potential Energy Surface) point characterization (PESPointCharacter True). This will allow the software to detect the saddle point and automatically restart the optimization with a suitable displacement [2]. - Disable Symmetry: The displacement applied during a restart is often symmetry-breaking. Therefore, you must disable the use of symmetry in the calculation (

UseSymmetry False) for this feature to work [2]. - Control Displacement Size: The size of the displacement can be adjusted with the

RestartDisplacementkeyword (default is 0.05 Ã…) [2].

Issue 3: Unrealistic Optimized Lattice Parameters

Problem: After a lattice optimization, the resulting unit cell volume or shape seems physically unrealistic.

Solution:

- Check for External Pressure: Confirm that the simulation is set to a realistic external pressure (often zero for most studies). An incorrect pressure setting can lead to over-compression or expansion of the cell.

- Review Computational Method: The choice of the exchange-correlation functional in DFT is critical. Some functionals are known to systematically over- or under-bind, leading to inaccurate lattice constants. Consult literature for a functional known to work well for your specific class of material.

- Ensure Sufficient K-points: Verify that the k-point grid used for Brillouin zone sampling is dense enough to achieve convergence in the stresses on the unit cell.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Unified Optimization of Nuclear Coordinates and Lattice Vectors

This protocol details the steps for a full geometry optimization of a periodic system.

- System Preparation: Construct an initial atomic structure and unit cell based on experimental data or a reasonable model.

- Software Configuration: In the input file, set the task to

GeometryOptimizationand enableOptimizeLattice Yes[2]. - Convergence Settings: Select appropriate convergence thresholds for your desired accuracy (e.g.,

Quality Normal) [2]. The following table summarizes standard criteria:

| Convergence Metric | Normal Quality Threshold | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | 1.0 × 10â»âµ | Hartree / atom |

| Maximum Gradient | 0.001 | Hartree / Ã…ngstrom |

| Maximum Step | 0.01 | Ã…ngstrom |

| Stress Energy | 5.0 × 10â»â´ | Hartree / atom |

Table: Standard convergence criteria for geometry optimization [2].

- Saddle Point Handling: To avoid convergence to saddle points, enable

PESPointCharacterin the properties block and setMaxRestartsto 3-5 withUseSymmetry False[2]. - Execution and Monitoring: Run the job and monitor the output for the steady reduction of energy, gradients, and stresses until convergence is reached.

Protocol 2: Data-Driven Lattice Customization and Optimization

This protocol outlines a advanced, generative approach for designing lattice materials with desired properties [27].

- Parametric Modeling: Use subdivision (SubD) modeling to digitally define the lattice skeleton and morphology. Parametrize key geometric features (e.g., strut nodes, profile shapes) [27].

- Dataset Generation: Generate a series of Representative Volume Elements (RVEs) by sampling the geometric parameters. Use a numerical homogenization method to compute their effective mechanical properties (e.g., Young's modulus) and build a dataset [27].

- Machine Learning Model Training: Train a two-tiered machine learning model. The first tier predicts the relative density, which is then fed as an input to the second-tier model (e.g., a Random Forest) that predicts the target elastic property [27].

- Inverse Design: Use a genetic algorithm to explore the geometric parameter space. The algorithm uses the trained ML model to find parameter combinations that produce a lattice structure matching your target mechanical properties [27].