Bridging Quantum Realms: A Modern Theoretical Framework for Electron-Nuclear Motion Coupling in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary theoretical frameworks describing the coupled dynamics of electronic and nuclear motion, a cornerstone for understanding photochemical processes and biochemical reactions.

Bridging Quantum Realms: A Modern Theoretical Framework for Electron-Nuclear Motion Coupling in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary theoretical frameworks describing the coupled dynamics of electronic and nuclear motion, a cornerstone for understanding photochemical processes and biochemical reactions. We explore foundational concepts moving beyond the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, including the Exact Factorization (XF) method and reactive orbital theories. The review covers cutting-edge methodological advances, from on-the-fly quantum dynamics for small molecules to pre-Born-Oppenheimer analog quantum simulation, which promises exponential computational savings. We address critical challenges in numerical implementation and model optimization, and discuss validation through experimental techniques like molecular orbital imaging. Finally, we synthesize how these integrated frameworks are revolutionizing the precision of drug design, from enzyme inhibitor development to personalized radiopharmaceutical therapy, offering a roadmap for future computational oncology.

Beyond Born-Oppenheimer: Foundational Theories of Electron-Nuclear Coupling

The Limits of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation and the Nonadiabatic Coupling Problem

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation represents a cornerstone of quantum chemistry, enabling the separate treatment of electronic and nuclear motions by exploiting the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei. This separation permits the construction of potential energy surfaces (PESs) upon which nuclear motion occurs. However, this approximation breaks down decisively in numerous chemically and physically important scenarios, giving rise to the nonadiabatic coupling problem. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundations of these limitations, details the computational methodologies developed to address them, and explores implications for research in molecular spectroscopy and photochemistry, particularly in the context of drug development where nonadiabatic processes often govern photostability and radiationless decay pathways.

In quantum chemistry and molecular physics, the Born–Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is the fundamental assumption that the wavefunctions of atomic nuclei and electrons in a molecule can be treated separately. This approach is justified by the substantial mass disparity between nuclei and electrons, which results in dramatically different timescales for their motion [1]. The approximation manifests mathematically by expressing the total molecular wavefunction as a product of separate electronic and nuclear components: Ψ_total ≈ ψ_electronic * ψ_nuclear [2].

The computational advantages of this separation are profound. For a molecule like benzene (12 nuclei, 42 electrons), the full Schrödinger equation involves 162 combined variables. Using the BO approximation, this simplifies to consecutive problems: first solving an electronic problem with 126 electronic coordinates for fixed nuclear positions, then using the resulting potential energy surface to solve a nuclear problem with only 36 coordinates [1]. This separation forms the basis for most modern computational chemistry methods, including Hartree-Fock theory and Density Functional Theory (DFT).

The BO approximation enables the conceptual framework of potential energy surfaces (PESs), which represent electronic energy as a function of nuclear coordinates. These surfaces provide the foundation for understanding molecular geometry, vibrational frequencies, and reaction pathways [2]. However, this very framework contains inherent limitations that become critically important in numerous chemical phenomena.

Theoretical Foundations: Where the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Breaks Down

Mathematical Derivation of the Breakdown Terms

The BO approximation originates from the total molecular Hamiltonian:

H = H_e + T_n

where H_e is the electronic Hamiltonian and T_n is the nuclear kinetic energy operator [3]. The approximation assumes that the electronic wavefunction depends parametrically on nuclear coordinates (R), meaning it adjusts instantaneously to nuclear motion.

The breakdown occurs when terms neglected in the BO approximation become significant. Specifically, when applying the nuclear kinetic energy operator to the product wavefunction:

T_n[Φ_k(r;R)χ(R)] = -Σ_{l=1}^{N_a} 1/(2M_l) ∇_l^2[Φ_k(r;R)χ(R)]

The resulting expression contains three key terms [4]:

- Term A:

Φ_k(r;R) ∇_l^2 χ(R)(kept in BO approximation) - Term B:

χ(R) ∇_l^2 Φ_k(r;R)(neglected in BO) - Term C:

[∇_l χ(R)] [∇_l Φ_k(r;R)](neglected in BO)

The BO approximation assumes Terms B and C are negligible because ∇_l Φ_k(r;R) ≈ ∇_e Φ_k(r;R) and m_e ≪ M_l [4]. This assumption fails when the electronic wavefunction changes rapidly with nuclear coordinates, making these nonadiabatic coupling terms significant.

Physical Scenarios for BO Breakdown

Table 1: Scenarios Where the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Fails

| Scenario | Physical Mechanism | Chemical Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Conical Intersections | Degeneracy between electronic potential energy surfaces [5] | Ultrafast radiationless decay in photochemistry |

| Avoided Crossings | Close approach of potential energy surfaces without full degeneracy [6] | Enhanced nonadiabatic transition probabilities |

| Jahn-Teller Systems | Symmetry-breaking distortions lifting electronic degeneracy [2] | Geometric distortions in symmetric complexes |

| Light Atom Dynamics | Significant zero-point energy and quantum delocalization [4] | Anomalous isotope effects in hydrogen bonding |

| Charge Transfer Processes | Electronic state changes during nuclear motion [4] | Electron transfer reactions in biological systems |

| Polarons | Slow electronic response to rapid nuclear motion [4] | Conductivity in organic semiconductors |

The BO approximation is least reliable for excited states, where energy separations between electronic states are smaller and nonadiabatic effects are more pronounced [2]. This is particularly relevant in photochemical processes fundamental to drug development, where excited-state dynamics often determine phototoxicity and degradation pathways.

The Computational Challenge: Quantifying Nonadiabatic Couplings

Defining Nonadiabatic Coupling Terms

Nonadiabatic couplings mathematically represent the interaction between electronic and nuclear vibrational motions [6]. The key quantity is the nonadiabatic coupling vector (also called derivative coupling):

d_{JK} = ⟨Ψ_J | (∂/∂R) | Ψ_K⟩ = h_{JK}/(E_J - E_K) [5]

where h_{JK} = ⟨Ψ_J | (∂H/∂R) | Ψ_K⟩ is the non-adiabatic coupling vector, and E_J and E_K are the energies of electronic states J and K [5]. This expression reveals the critical insight that the coupling between states becomes large when their energy difference is small, formally diverging at conical intersections where E_J = E_K.

The branching space around conical intersections is defined by two vectors: (1) the gradient difference vector g_{JK} = ∂E_J/∂R - ∂E_K/∂R, and (2) the nonadiabatic coupling vector h_{JK} [5]. These two vectors define the two-dimensional space in which the degeneracy between electronic states is lifted.

Methodologies for Computing Nonadiabatic Couplings

Table 2: Computational Methods for Nonadiabatic Coupling Evaluation

| Method | Key Features | Accuracy & Limitations | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Differentiation | Finite difference of wavefunction overlaps [6] | Numerically unstable; accuracy depends on displacement size | High (requires 2N calculations for second-order accuracy) |

| Analytic Gradient Methods | Direct analytic computation of derivatives [6] | High accuracy; mathematically complex to implement | Low (cheaper than single-point calculations) |

| TDDFT-Based Approaches | Uses reduced transition density matrices [6] [7] | Good for large systems; accuracy depends on functional | Moderate (comparable to SCF/TDDFT gradients) |

| Coupled Cluster Theory | High-level electron correlation treatment [8] | Very accurate but can have artifacts at intersections | Very High (especially for nonadiabatic couplings) |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Neural network prediction from PES information [7] | Fast evaluation after training; data-dependent accuracy | Low (after training) |

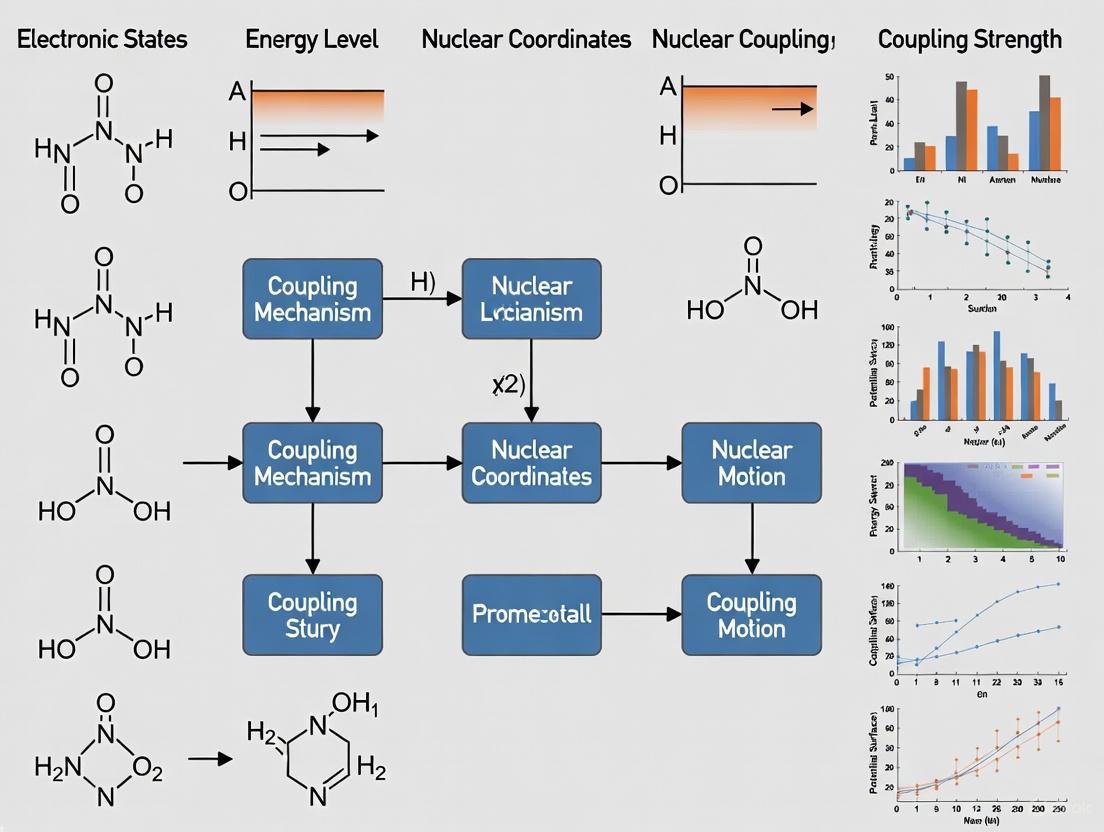

The following diagram illustrates the mathematical and physical relationships in nonadiabatic coupling:

Figure 1: Logical relationships showing the mathematical foundations of Born-Oppenheimer approximation breakdown and the emergence of nonadiabatic couplings and conical intersections.

Advanced Computational Approaches and Protocols

Wavefunction-Based Methods

Traditional wavefunction methods offer rigorous approaches to computing nonadiabatic couplings but at significant computational expense. Multi-configurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) and multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI) methods can properly describe regions where electronic states are strongly coupled [6]. These methods are particularly important for conical intersections, where single-reference methods often fail.

Coupled cluster (CC) theory represents one of the most accurate electronic structure methods but has historically faced challenges with conical intersections, where numerical artifacts including complex-valued energies can occur [8]. Recent advances in similarity constrained coupled cluster (SCC) theory enforce orthogonality between electronic states, restoring proper description of conical intersections while maintaining the high accuracy of coupled cluster theory [8].

Density-Based and Machine Learning Approaches

Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TDDFT) provides a more computationally efficient approach for computing nonadiabatic couplings, though with important limitations. Standard linear-response TDDFT fails for conical intersections involving the ground state due to incorrect topology [5]. Spin-flip TDDFT (SF-TDDFT) addresses this limitation by treating the ground state as an excitation from a higher-spin reference, enabling correct description of conical intersections involving the ground state [5].

Machine learning approaches represent a promising new direction. Recent work has demonstrated that nonadiabatic couplings can be computed using only potential energy surface information (energies, gradients, and Hessians) without explicit wavefunctions [7]. Embedding Atom Neural Network (EANN) methods can provide analytical Hessian matrix elements efficiently, enabling nonadiabatic molecular dynamics simulations of larger systems [7].

The following workflow illustrates a protocol for computing nonadiabatic couplings:

Figure 2: Computational workflow for calculating nonadiabatic coupling elements using different electronic structure methodologies.

Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

Rigorous benchmarking of nonadiabatic coupling methods is essential. Studies comparing wavefunction-based and PES-based algorithms show that PES-based approaches provide accurate results except at truly degenerate conical intersections where both methods diverge [7]. For the CH₂NH molecule, PES-based nonadiabatic coupling elements showed excellent agreement with wavefunction-based results for energy gaps >1 kcal/mol, with relative deviations of ~3-4% [7].

Table 3: Computational Tools for Nonadiabatic Dynamics Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Key Features | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Chem | Nonadiabatic coupling calculations | CIS, TDDFT, SF-TDDFT derivative couplings [5] | BH&HLYP functional (50% HF exchange) recommended for SF-TDDFT |

| COLUMBUS | Analytic MRCI gradients & couplings | Full configuration interaction capabilities [6] | High accuracy but computationally demanding |

| MOLPRO | Numerical differentiation of NACME | Wavefunction overlaps at displaced geometries [6] | Computationally expensive due to multiple single-point calculations |

| EANN Models | Machine learning potential | Analytical Hessian matrix elements [7] | Requires training data but enables fast NAC evaluation |

| SCCSD Theory | Coupled cluster with conical intersections | Correct topology at intersections [8] | Removes numerical artifacts of standard CC methods |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Nonadiabatic processes play crucial roles in photobiological phenomena relevant to drug development. Many pharmaceutical compounds become phototoxic when exposed to light, initiating photochemical reactions that can cause cellular damage. The radiationless decay pathways mediated by conical intersections often determine whether a molecule remains in an excited electronic state long enough to undergo photoreactions or efficiently returns to the ground state.

Understanding these processes at the quantum mechanical level enables rational design of photostable drugs with reduced phototoxicity risks. Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics simulations can predict the lifetime of excited states and identify molecular modifications that steer photophysical pathways toward harmless energy dissipation. For example, introducing specific functional groups can create "molecular shuttles" that guide the system through desired conical intersections, controlling photochemical outcomes.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provides an essential foundation for computational chemistry, but its limitations in describing nonadiabatic phenomena are increasingly relevant as we tackle more complex chemical systems. The nonadiabatic coupling problem represents both a theoretical challenge and a computational bottleneck in quantum chemistry.

Future progress will likely come from several directions: (1) improved electronic structure methods that accurately describe conical intersections with lower computational cost, (2) machine learning approaches that bypass explicit coupling calculations, and (3) efficient dynamical methods that handle the quantum nature of nuclear motion near intersections. The integration of these approaches will enable predictive simulation of nonadiabatic processes in increasingly complex molecular systems, with significant implications for materials science, photochemistry, and pharmaceutical development.

As computational power increases and algorithms improve, the treatment of phenomena beyond the Born-Oppenheimer approximation will transition from specialized research topics to standard tools in computational chemistry, enabling more accurate prediction and design of molecular systems across chemical and biological domains.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation has long served as the cornerstone for understanding molecular systems by separating the slow motion of nuclei from the fast motion of electrons. However, this framework becomes impractical when nuclear and electronic motions occur on comparable timescales, such as in photodissociation, strong-field ionization, or non-adiabatic processes involving multiple electronic states. The Exact Factorization (XF) approach has emerged as a fundamental alternative that provides a unique perspective on electron-nuclear coupling by recasting the molecular wavefunction into an exactly factorized form [9]. This theoretical framework offers distinctive advantages for interpreting correlated electron-ion dynamics, particularly in scenarios where the conventional BO picture fails or becomes computationally prohibitive.

Within the XF approach, the molecular wavefunction is factored into a single correlated product of marginal and conditional factors, providing unique time-dependent potentials that drive the motion of each subsystem while accounting for complete coupling to the others [9]. This review explores the XF formalism with particular emphasis on its conceptual foundation, mathematical structure, and practical implementation challenges, positioning it within the broader context of theoretical frameworks for electronic and nuclear motion coupling research.

Theoretical Foundations of the Exact Factorization

Core Formalismo of XF

The Exact Factorization approach fundamentally reconsiders the time-dependent molecular wavefunction Ψ(r,R,t), where r and R collectively represent electronic and nuclear coordinates, respectively. The XF formalism expresses this wavefunction as an exact product of two components [9]:

Ψ(r,R,t) = χ(R,t) Φ_R(r,t)

This factorization is unique up to a R- and t-dependent phase factor, with the partial normalization condition requiring that ⟨ΦR(t)|ΦR(t)⟩r = 1 for all R and t [9]. In this framework, χ(R,t) represents the nuclear wavefunction, while ΦR(r,t) is the electronic wavefunction that depends parametrically on the nuclear coordinates. This stands in contrast to the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, where the electronic wavefunction is typically associated with a single electronic state or a simple linear combination of states.

The resulting equations of motion

Applying the Dirac-Frenkel variational principle to the factored wavefunction leads to a set of coupled equations governing the evolution of each component. For the electronic factor, the equation takes the form [9]:

[Ĥel(r,R,t) - ε(R,t)] ΦR(r,t) = i∂t ΦR(r,t)

where Ĥ_el represents the electronic Hamiltonian, while for the nuclear component:

∑ν [1/(2Mν)] [-i∇ν + Aν(R,t)]^2 + V̂next(R,t) + ε(R,t)] χ(R,t) = i∂t χ(R,t)

In these equations, two key potentials emerge: the time-dependent potential energy surface (TDPES) ε(R,t) and the time-dependent vector potential A_ν(R,t) [9]. These potentials contain the complete electron-nuclear coupling and are defined as:

ε(R,t) = ⟨ΦR(t)| Ĥel(R,t) - i∂t |ΦR(t)⟩r Aν(R,t) = ⟨ΦR(t)| -i∇ν ΦR(t)⟩r

The TDPES acts as a scalar potential driving nuclear motion, while the vector potential incorporates geometric phase effects [9]. The electron-nuclear coupling term Ûen[ΦR,χ] appearing in the electronic equation ensures bidirectional correlation between the subsystems.

Table 1: Key Components of the Exact Factorization Framework

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Wavefunction | Φ_R(r,t) | Parametrically dependent on nuclear coordinates; contains conditional electronic information | ||

| Nuclear Wavefunction | χ(R,t) | Marginal nuclear probability amplitude | ||

| Time-Dependent Potential Energy Surface (TDPES) | ε(R,t) = ⟨Φ_R(t) | Ĥel-i∂t | ΦR(t)⟩r | Exact potential driving nuclear motion |

| Time-Dependent Vector Potential | Aν(R,t) = ⟨ΦR(t) | -i∇νΦR(t)⟩_r | Incorporates geometric phase effects | |

| Electron-Nuclear Coupling | Ûen[ΦR,χ] | Couples electronic and nuclear subsystems |

The Exact Factorization Potentials: A Detailed Analysis

The Time-Dependent Potential Energy Surface (TDPES)

The TDPES represents one of the most significant conceptual advances offered by the XF approach. Unlike Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surfaces, which are static and depend solely on nuclear configuration, the TDPES evolves in time and captures the exact interplay between electronic and nuclear dynamics [9]. This potential contains contributions from the electronic energy, as well as terms involving the time derivative of the electronic wavefunction, effectively encoding how electronic evolution influences nuclear motion.

In strong-field processes such as laser-induced dissociation, the TDPES has been shown to exhibit distinctive features that provide interpretive power beyond what is available in the BO picture. For instance, in the dissociation of H₂⁺, the TDPES demonstrates steps and plateaus that correlate with electronic transitions and nuclear wavepacket bifurcation [9]. These features offer a unique window into the correlated dynamics of the electron-nuclear system.

The Time-Dependent Vector Potential

The time-dependent vector potential A_ν(R,t) embodies the momentum coupling between electronic and nuclear subsystems. This potential is directly related to the Berry connection familiar from adiabatic quantum mechanics but extends this concept into the time-dependent, non-adiabatic regime [9]. The vector potential captures how electronic motion generates effective magnetic fields that influence nuclear dynamics, particularly in systems with complex geometric phases or spin-orbit couplings.

In practical implementations, the vector potential plays a crucial role in ensuring energy conservation and proper momentum transfer between electrons and nuclei. Its curl gives rise to an effective magnetic field that can significantly alter nuclear trajectories in regions of strong non-adiabatic coupling.

Computational Implementation and Challenges

Numerical Instabilities in XF Simulations

Despite its theoretical elegance, practical implementation of the exact factorization presents formidable challenges. The most significant issue arises from the structure of the coupling terms in the XF equations, which involve division by the nuclear probability density |χ(R,t)|² [10]. In regions where the nuclear density becomes small, these terms lead to severe numerical instabilities, limiting direct quantum dynamical simulations to simple model systems.

Recent analytical work has precisely identified the origin of these instabilities. As the nuclear wavefunction bifurcates – for instance, during photodissociation – the XF components can diverge even without explicit coupling between Born-Oppenheimer states [10]. This problematic behavior persists across different representations, including both stationary and moving frames of reference, and in atomic basis set representations of the electronic wavefunction.

Mixed Quantum-Classical Approximations

To overcome the limitations of fully quantum implementations, several mixed quantum-classical (MQC) methods have been developed based on the XF framework. These include the Coupled-Trajectory Mixed Quantum-Classical (CTMQC) approach and various surface-hopping methods incorporating XF concepts (SHXF) [9]. These methods approximate the nuclear quantum momentum, a key quantity in the exact electron-nuclear coupling, using either coupled trajectories or auxiliary trajectories.

Table 2: Comparison of XF-Based Mixed Quantum-Classical Methods

| Method | Approximation Scheme | Quantum Momentum Treatment | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTMQC | Coupled classical trajectories | Computed from ensemble of coupled trajectories | Rigorously derived from XF; includes quantum decoherence effects |

| CTSH | Surface-hopping with coupled trajectories | Computed from ensemble of coupled trajectories | Combines trajectory coupling with surface hopping algorithm |

| SHXF | Surface-hopping with auxiliary trajectories | Approximated using auxiliary trajectories | Uses auxiliary trajectories to estimate nuclear density evolution |

The quantum momentum term, which measures spatial variations in the nuclear density during non-adiabatic dynamics, couples strongly to the electronic evolution and provides significant corrections to mean-field approximations [9]. Different schemes have proposed alternative approaches to calculating this term, with some implementations modifying the definition to ensure zero population transfer in regions of negligible non-adiabatic coupling.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Computational Framework for XF Simulations

Implementing exact factorization calculations requires careful attention to both electronic structure methods and nuclear propagation techniques. The following protocol outlines a typical workflow for studying molecular dynamics within the XF framework:

System Preparation: Define the molecular system, including nuclear coordinates, initial conditions, and external fields if present. For the photodissociation case studies referenced in the search results, initial wavepackets are typically prepared in excited electronic states [10] [9].

Electronic Structure Calculation: Compute the electronic Hamiltonian Ĥ_el(r,R) for relevant nuclear configurations. This may employ various quantum chemistry methods such as configuration interaction or density functional theory, depending on system size and accuracy requirements [11].

Wavefunction Initialization: Prepare the initial factored wavefunction Ψ(r,R,0) = χ(R,0)Φ_R(r,0), where the electronic component is often initialized as a BO electronic state or a superposition thereof [9].

Time Propagation: Propagate the coupled electronic and nuclear equations using appropriate numerical methods. For fully quantum simulations, this may involve split-operator or Chebyshev propagators, while MQC methods employ classical trajectory ensembles [9].

Analysis: Extract observable quantities such as nuclear probability densities, electronic populations, and the TDPES and vector potentials throughout the dynamics.

A "Minimal" Model for XF Analysis

Recent investigations have employed simplified model systems to analytically identify the origins of numerical instabilities in XF implementations. One such "minimal" model examines photodissociation in a one-dimensional system, deriving exact expressions for the XF dynamics and precisely locating the source of the XF-specific challenges [10]. This approach has demonstrated that the divergence problem arises from nuclear wavefunction bifurcation and persists in both stationary and moving reference frames.

These model studies provide crucial insight into the fundamental limitations of current XF implementations and guide the development of more robust computational schemes. The analytical understanding gained from simple systems informs the treatment of more complex molecular applications.

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for Exact Factorization simulations, highlighting key steps and methodological challenges.

Research Applications and Case Studies

Strong-Field Dissociation and Ionization

The XF approach has demonstrated particular utility in interpreting strong-field molecular processes, where multiple electronic states contribute significantly to the dynamics. Studies on prototype systems like H₂⁺ have revealed how the TDPES evolves during laser-driven dissociation, providing insights into correlation mechanisms that are obscured in the BO picture [9]. In these strong-field scenarios, the nuclear wavepacket typically spans many BO states, including continuum states beyond the ionization threshold.

For ionization processes, the XF framework offers a unique perspective by providing a time-dependent potential that drives electron dynamics. This has been applied to analyze strong-field ionization in H₂⁺, where the correlated electron-nuclear dynamics lead to characteristic features in both the TDPES and the electronic current [9]. The XF interpretation helps disentangle the complex interplay between electronic excitation, ionization, and nuclear motion.

Non-Bound States and Reactive Scattering

The exact factorization formalism naturally accommodates non-bound states, making it well-suited for studying reactive scattering processes. While traditional approaches to reactions like X + F₂ → XF + F (X = Mu, H, D) rely on quantum reactive scattering calculations on accurate ab initio potential energy surfaces [12], the XF offers an alternative perspective that may provide additional interpretive power for understanding tunneling and isotope effects in these systems.

The vector potential in the XF framework particularly captures non-adiabatic effects that are crucial in reactive encounters, such as geometric phase contributions in systems involving conical intersections. This makes XF a promising approach for understanding fine details of reaction dynamics that may be challenging to extract from conventional simulations.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Exact Factorization Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in XF Research |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | MOLPRO, Gaussian | Compute potential energy surfaces and electronic structure properties [11] [12] |

| Wavefunction Propagation | Custom MATLAB/Python implementations, ABC code [12] | Numerical solution of time-dependent Schrödinger equation for nuclear and electronic components |

| Mixed Quantum-Classical Dynamics | CTMQC, CTSH, SHXF implementations [9] | Approximate quantum dynamics using trajectory ensembles |

| Basis Sets | aug-cc-pVQZ (AVQZ), 6-311G(d,p) [12] [13] | Represent molecular orbitals in electronic structure calculations |

| Quantum Chemistry Methods | MRCI, DFT, CASSCF [14] [12] | Calculate accurate electronic wavefunctions and potentials |

Diagram 2: Relationship between Exact Factorization framework, its computational methodologies, and research applications.

Future Perspectives and Development Directions

The exact factorization approach continues to evolve as researchers address its implementation challenges and expand its application domains. Current development focuses particularly on stabilizing the numerical integration of the XF equations, with promising approaches including regularization schemes for low-density regions and improved treatments of the quantum momentum in mixed quantum-classical methods [10] [9].

As these technical hurdles are overcome, XF is poised to make significant contributions to our understanding of complex molecular processes in photochemistry, materials science, and biochemistry. The unique interpretive power of the TDPES and the rigorous account of electron-nuclear correlation offer opportunities for gaining fundamental insights that bridge traditional theoretical frameworks. The continued development of efficient computational implementations will determine how broadly this powerful theoretical approach can be applied to realistic molecular systems.

Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) represents a paradigm shift in chemical reactivity analysis by establishing a direct, quantitative connection between specific electron motions in molecular orbitals and the resulting nuclear motions that constitute chemical reactions. By identifying the occupied and unoccupied molecular orbitals that undergo the largest energy changes during a reaction, ROET moves beyond conventional frontier molecular orbital theory to provide a physics-based framework for understanding reaction mechanisms. This whitepaper details the theoretical foundations, computational protocols, and key applications of ROET, with particular emphasis on its integration with electrostatic force theory to bridge the historical divide between electronic and nuclear motion theories. The framework demonstrates that electrostatic forces generated by reactive orbitals—termed reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces (ROEF)—create distinct pathways on potential energy surfaces, effectively carving the grooves along which reactions proceed.

The fundamental question "What drives chemical reactions: electron motion or nuclear motion?" has historically produced two divergent theoretical perspectives in chemistry. Electronic theories, including frontier orbital theory and organic reaction mechanism theory, emphasize the primacy of electron motion in orchestrating molecular transformations. In contrast, nuclear motion theories, rooted in the potential energy surface (PES) framework, focus predominantly on atomic nuclear motions and have become the dominant paradigm for predicting reaction rates [15] [16].

Despite addressing the same chemical phenomena, the interrelation between these perspectives has remained largely unexplored, with electronic theories often lacking rigorous quantitative validation [16]. Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) emerges as a unifying framework that reconciles these historically separate domains by identifying the specific molecular orbitals—termed "reactive orbitals"—whose energy changes primarily drive chemical transformations [15] [17].

Theoretical Foundations of ROET

Basic Principles and Conceptual Framework

ROET operates on the fundamental premise that chemical reactions are driven by specific electron transfers between molecular orbitals, and that these transfers can be identified by monitoring orbital energy variations throughout the reaction pathway. The theory leverages a statistical mechanical framework to identify the molecular orbitals with the largest energy changes before and after the reaction as the reactive orbitals [15].

Unlike conventional analysis methods that rely on localized orbitals (e.g., natural bond orbitals), ROET examines canonical orbitals, which possess clear physical significance as described by generalized Koopmans' theorem [16]. According to this theorem, occupied and unoccupied orbital energies correspond theoretically to ionization potentials and electron affinities, respectively—both experimentally measurable quantities via photoelectron spectroscopy [16].

Distinction from Conventional Orbital Theories

ROET represents a significant departure from traditional frontier molecular orbital (FMO) theory, which primarily focuses on the highest occupied (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied (LUMO) molecular orbitals. In practice, reactive orbitals identified by ROET are often neither the HOMO nor the LUMO [15] [16]. This distinction becomes particularly pronounced in catalytic reactions involving transition metals, where low-energy valence orbitals with high electron densities frequently serve as the reactive orbitals [16].

The development of ROET was enabled by advancements in long-range corrected (LC) density functional theory (DFT), which allows for accurate and quantitative orbital energy calculations [16]. Recent comparative studies have demonstrated the exceptional fidelity of LC-DFT in replicating both orbital shapes and energies when compared to Dyson orbitals derived from coupled-cluster methods [15].

Methodological Framework and Computational Protocols

Identifying Reactive Orbitals

The computational protocol for identifying reactive orbitals through ROET involves several methodical steps:

Geometry Optimization and Reaction Pathway Calculation

- Optimize structures of reactants, products, and potential transition states

- Calculate the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) to map the complete reaction pathway

- Perform calculations using long-range corrected density functionals (e.g., LC-ωPBE, LC-BLYP)

- Utilize sufficiently large basis sets with diffuse functions for accurate orbital energy determination

Orbital Energy Tracking

- Compute canonical molecular orbitals along the reaction coordinate

- Track orbital energy changes (Δε) for all molecular orbitals

- Identify orbitals with largest energy changes between reactants and products

- Normalize energy changes to account for systematic shifts

Reactive Orbital Validation

- Verify orbital continuity along the reaction coordinate

- Analyze electron density changes associated with reactive orbitals

- Correlate orbital energy changes with reaction barrier heights

- Compare with experimental spectroscopic data where available

Calculating Electrostatic Forces from Reactive Orbitals

The connection between orbital energy changes and nuclear motion is established through electrostatic force theory, which quantifies the forces exerted by electronic configurations on molecular nuclei via Hellmann-Feynman forces [15] [17]. The fundamental equations are:

The Hamiltonian governing the system of electrons and nuclei is given by:

The Hellmann-Feynman force on nucleus A is expressed as:

Within the independent electron approximation, the force contribution from the i-th orbital on nucleus A is:

The specific force contribution from an occupied reactive orbital (ORO) is then:

The reactive orbital-based electrostatic force (ROEF) vector is finally obtained as:

This formulation isolates the contribution of ORO variations along the reaction pathway, enabling direct assessment of how changes in reactive orbitals influence nuclear motions during chemical reactions [15].

Relationship Between Orbital Energies and Electrostatic Forces

A crucial insight provided by ROET is the direct relationship between ROEF and Kohn-Sham orbital energies. The derivative of orbital energy with respect to nuclear coordinates can be expressed as:

where h_i represents the one-electron Hamiltonian [15]. This establishes that electrostatic forces arising from reactive orbitals are governed by the negative gradient of orbital energy, creating a fundamental connection between molecular orbital energy variations and nuclear motion [17].

Key Research Findings and Experimental Validation

Systematic Analysis of Diverse Reaction Classes

Comprehensive analysis of 48 representative reactions using the ROET framework has revealed distinct patterns in how reactive orbitals drive chemical transformations [15] [17]. The systematic investigation across different reaction classes provides quantitative insights into the electronic basis of reaction mechanisms.

Table 1: Classification of Reaction Types Based on ROEF Behavior

| Reaction Type | ROEF Onset | ROEF Magnitude | Barrier Correlation | Representative Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Early in reaction coordinate | Strong, sustained | High correlation | Nucleophilic substitutions, Cycloadditions |

| Type II | Pre-transition state | Sharp increase near TS | Moderate correlation | Proton transfers, Tautomerizations |

| Type III | Post-transition state | Weak, variable | Poor correlation | Simple bond dissociations |

| Type IV | Oscillatory along pathway | Multiple maxima | Complex relationship | Multi-step catalytic cycles |

Connection to Curly Arrow Representations

A significant finding from ROET analysis is the direct correspondence between reactive orbital transitions and the conventional curly arrow representations used in organic chemistry [15] [17]. Analysis of organic reactions reveals that electron transfers between identified reactive orbitals align closely with the directions of curly arrows used to represent reaction mechanisms [16].

This connection provides rigorous theoretical foundation for empirical electron-pushing formalism widely used in mechanistic chemistry, bridging qualitative electron-transfer representations with quantitative computational analysis.

Molecular Orbital Imaging Validation

Recent advancements in molecular orbital imaging techniques have provided experimental validation for ROET predictions. Valence electron densities of glycine and cytidine visualized using synchrotron X-ray diffraction show remarkable agreement with those obtained through LC-DFT calculations [16]. Furthermore, subtraction of LC-DFT molecular orbital densities from total electron densities has enabled reconstruction of 2pπ orbital density images, allowing direct experimental analysis of electron motions that drive chemical reactions [16].

Visualization of ROET Framework

Figure 1: ROET Computational Workflow. The diagram illustrates the integration of molecular orbital energy analysis with nuclear motion through reactive orbital-based electrostatic forces (ROEF), bridging electronic structure changes with reaction pathway evolution on the potential energy surface.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ROET Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Functions | Key Applications in ROET | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Methods | LC-DFT, TD-DFT, CASSCF | Orbital energy calculation, Reaction pathway mapping | Long-range correction essential for accuracy |

| Orbital Analysis | Canonical orbital tracking, Density difference plots | Reactive orbital identification, Electron transfer visualization | Avoid localized orbital transformations |

| Force Calculation | Hellmann-Feynman force implementation, Gradient analysis | ROEF computation, Force decomposition | Numerical stability at near-degeneracies |

| Pathway Mapping | Intrinsic reaction coordinate, Potential energy surface | Reaction pathway characterization, Transition state location | Dense points near transition state |

| Visualization | Orbital rendering, Density isosurfaces | Reactive orbital visualization, Communication of results | Consistent isovalues for comparison |

Applications in Chemical Research

Organic Reaction Mechanisms

ROET analysis of organic reactions has provided quantitative justification for conventional curly arrow representations, demonstrating that electron transfers between identified reactive orbitals correspond closely to the directions of arrows used to represent reaction mechanisms [16]. This offers a rigorous theoretical foundation for empirical electron-pushing formalism in organic chemistry.

Transition Metal Catalysis

In catalytic reactions involving transition metals, ROET reveals that reactive orbitals are frequently low-energy valence orbitals with high electron densities rather than frontier orbitals [16]. This insight helps explain the distinctive reactivity patterns of transition metal complexes and provides guidance for catalyst design.

Enzymatic Reaction Analysis

The application of ROET to enzymatic processes enables comprehensive elucidation of electronic roles played by protein environments, offering insights into their contributions to reaction mechanisms and catalytic efficiency [16].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The integration of ROET with emerging experimental techniques in molecular orbital imaging presents promising avenues for future research. Direct experimental observation of orbital density changes during reactions could provide unprecedented validation of ROET predictions [16]. Additionally, the application of ROET to materials science, particularly in understanding interfacial reactions and catalytic processes, represents a fertile area for investigation.

Further methodological developments should focus on improving computational efficiency for larger systems, extending the theory to excited-state reactions, and incorporating environmental effects for condensed-phase applications. The continued refinement of long-range corrected functionals will also enhance the quantitative accuracy of ROET analyses.

Reactive Orbital Energy Theory provides a unifying framework that bridges the historical divide between electronic and nuclear motion theories in chemistry. By identifying specific molecular orbitals that drive chemical transformations and quantifying their electrostatic effects on nuclear motions, ROET offers a physics-based foundation for understanding and predicting chemical reactivity. The theory's ability to connect qualitative electron-pushing formalism with quantitative potential energy surface analysis represents a significant advance in theoretical chemistry, with broad applications across organic, inorganic, and biological chemistry.

This technical guide elucidates the theoretical framework connecting electron density dynamics to nuclear motion in chemical systems through the application of the Hellmann-Feynman theorem. We present a physics-based paradigm that reconciles historically divergent electronic and nuclear motion theories by quantifying how electrostatic forces from specific reactive molecular orbitals direct reaction pathways. By integrating Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) with electrostatic force analysis, this work establishes that the most stabilized occupied orbital during a reaction generates electrostatic forces that guide atomic nuclei along intrinsic reaction coordinates. The framework demonstrates that variations in orbital energy directly correlate with nuclear motion, creating distinct grooves on potential energy surfaces that shape chemical transformation pathways. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a unified perspective on electron-nuclear coupling, offering quantitative methodologies for predicting reaction mechanisms and designing targeted molecular interventions.

The fundamental question of what drives chemical reactions has historically produced two divergent theoretical perspectives: electronic theories that emphasize electron motion as the orchestrator of molecular transformations, and nuclear motion theories that focus on atomic nuclei dynamics within the potential energy surface (PES) framework [16] [17]. While both address the same chemical phenomena, their interrelationship has remained largely unexplored, creating a conceptual gap in our understanding of chemical reactivity.

Electronic theories, including frontier orbital theory and organic reaction mechanism theory, propose that electron motion directs molecular structural changes during chemical reactions. However, this assertion has lacked rigorous quantitative validation. Conversely, nuclear motion theories, which quantitatively describe energetic changes related to nuclear motions, have become the dominant paradigm for predicting reaction rates despite providing limited insight into electronic origins [16]. This division is particularly relevant for drug development professionals seeking to understand molecular interactions at fundamental levels.

The integration of these perspectives represents a paradigm shift in chemical reactivity analysis. By examining the specific electron motions that dictate reaction pathways through Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) and connecting them to nuclear motions via electrostatic force theory, we establish a unified framework that clarifies the electronic basis of reaction mechanisms [16] [17]. This approach demonstrates that occupied reactive orbitals—the most stabilized occupied molecular orbitals during reactions—generate electrostatic forces that guide atomic nuclei along reaction pathways, effectively carving grooves along intrinsic reaction coordinates on potential energy surfaces.

Theoretical Foundations

The Hellmann-Feynman Theorem: Basic Principles and Formulations

The Hellmann-Feynman theorem provides the fundamental connection between electronic structure and forces acting on atomic nuclei. This theorem relates the derivative of the total energy with respect to a parameter to the expectation value of the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to that same parameter [18]. Formally, the theorem states:

$$\frac{\mathrm{d}E{\lambda}}{\mathrm{d}{\lambda}} = \bigg\langle \psi{\lambda} \bigg| \frac{\mathrm{d}{\hat{H}}{\lambda}}{\mathrm{d} \lambda} \bigg| \psi{\lambda} \bigg\rangle$$

where $\hat{H}{\lambda}$ is the Hamiltonian dependent on parameter $\lambda$, $|\psi{\lambda}\rangle$ is the corresponding wavefunction, and $E{\lambda}$ is the energy eigenvalue satisfying $\hat{H}{\lambda}|\psi{\lambda}\rangle = E{\lambda}|\psi_{\lambda}\rangle$ [18].

The profound implication of this theorem is that once the spatial distribution of electrons has been determined by solving the Schrödinger equation, all forces in the system can be calculated using classical electrostatics [18]. For molecular systems, the parameter $\lambda$ corresponds to nuclear coordinates, enabling the calculation of intramolecular forces that determine equilibrium geometries and reaction pathways.

Hamiltonian Formulation for Molecular Systems

The Hamiltonian governing a system of electrons and nuclei is given by:

$$\hat{H} = \sum\limits{i}^{n{\text{elec}}} \left(-\frac{1}{2}\nabla{i}^{2} - \sum\limits{A}^{n{\text{nuc}}} \frac{Z{A}}{r{iA}}\right) + \sum\limits{i

where $\nabla{i}^{2}$ denotes the Laplacian with respect to electron $i$, $r{iA}$ is the electron-nucleus distance, $r{ij}$ is the interelectronic distance, $R{AB}$ represents the internuclear distance, $Z{A}$ is the nuclear charge, and $n{\text{elec}}$ and $n_{\text{nuc}}$ represent the numbers of electrons and nuclei, respectively [16] [17]. All expressions use atomic units ($\hbar = e^{2} = m = 1$).

Electrostatic Force Derivation

Building upon electrostatic theory, the Hellmann-Feynman force exerted by electrons and nuclei on nucleus $A$ is derived as:

$$\mathbf{F}{A} = -\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{R}{A}}\langle \Psi | \hat{H} | \Psi \rangle = -\langle \Psi | \frac{\partial \hat{H}}{\partial \mathbf{R}_{A}} | \Psi \rangle$$

This expression simplifies to:

$$\mathbf{F}{A} = Z{A}\int d\mathbf{r} \rho(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}|^{3}} - Z{A}\sum\limits{B(\neq A)}^{n{\text{nuc}}} Z{B} \frac{\mathbf{R}{AB}}{{R{AB}}^{3}}$$

where $\rho(\mathbf{r})$ represents the electron density at position $\mathbf{r}$, $\mathbf{R}{A}$ is the position vector of nucleus $A$, and $\mathbf{R}{AB}$ is the vector from nucleus $A$ to nucleus $B$ [16] [17]. According to the Hellmann-Feynman theorem, these forces represent classical electrostatic forces when the electron distribution is determined variationally [18].

Table 1: Components of Hellmann-Feynman Forces in Molecular Systems

| Force Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic | $Z{A}\int d\mathbf{r} \rho(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}_{A}|^{3}}$ | Force exerted by electron density on nucleus A |

| Nuclear-Nuclear | $-Z{A}\sum\limits{B(\neq A)}^{n{\text{nuc}}} Z{B} \frac{\mathbf{R}{AB}}{{R{AB}}^{3}}$ | Repulsive force from other nuclei on nucleus A |

| Total Force | $\mathbf{F}{A} = \mathbf{F}{A}^{\text{elec}} + \mathbf{F}_{A}^{\text{nuc}}$ | Net force determining nuclear acceleration |

Independent Electron Approximation

Within independent electron approximations, such as the Kohn-Sham density functional theory, the electron density simplifies to:

$$\rho(\mathbf{r}) = \sum\limits{i}^{n{\text{elec}}} \rho{i}(\mathbf{r}) = \sum\limits{i}^{n{\text{elec}}} \phi{i}^{*}(\mathbf{r})\phi_{i}(\mathbf{r})$$

where $\phi_{i}$ is the $i$-th spin orbital wavefunction. The total electrostatic force on nucleus $A$ can then be expressed as the sum of contributions from individual orbitals:

$$\mathbf{F}{A} = \mathbf{F}{A}^{\text{elec}} + \mathbf{F}{A}^{\text{nuc}} \simeq Z{A}\sum\limits{i}^{n{\text{elec}}} \mathbf{f}{iA} - Z{A}\sum\limits{B(\neq A)}^{n{\text{nuc}}} Z{B} \frac{\mathbf{R}{AB}}{{R_{AB}}^{3}}$$

where the force contribution from the $i$-th orbital on nucleus $A$ is:

$$\mathbf{f}{iA} = \int d\mathbf{r} \phi{i}^{*}(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}|^{3}} \phi_{i}(\mathbf{r})$$

This orbital decomposition enables the identification of specific molecular orbitals that contribute most significantly to forces driving chemical reactions [16].

Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) Framework

Fundamental Principles

Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) addresses the challenge of identifying specific electron motions that dictate reaction pathways by leveraging a statistical mechanical framework to identify molecular orbitals with the largest orbital energy variations during reactions [16] [17]. Unlike conventional electronic analysis methods that rely on localized orbitals, ROET examines canonical orbitals, which possess clear physical significance as described by generalized Koopmans' theorem.

The theoretical foundation of ROET rests on the principle that occupied and unoccupied orbital energies correspond to ionization potentials and electron affinities, respectively, both experimentally measurable via photoelectron spectroscopy [16]. This approach enables comprehensive elucidation of electronic roles played by catalysts, auxiliary reagents in metal-catalyzed reactions, and proteins in enzymatic processes.

Identification of Reactive Orbitals

Reactive orbitals are identified as those molecular orbitals, both occupied and unoccupied, that exhibit the largest orbital energy variations before and after a reaction [17]. Interestingly, reactive orbitals identified by ROET are often neither the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) nor the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). This distinction becomes particularly pronounced in catalytic reactions involving transition metals, where low-energy valence orbitals with high electron densities frequently serve as reactive orbitals [16].

The development of ROET was enabled by advancements in long-range corrected (LC) density functional theory (DFT), which permits accurate and quantitative orbital energy calculations [16]. Comparative studies of molecular orbital densities obtained from LC-DFT canonical orbitals and Dyson orbitals derived from the coupled-cluster method have demonstrated exceptional fidelity of LC-DFT in replicating both orbital shapes and energies [16] [17].

Connection to Curly Arrow Representations

ROET analysis of organic reactions has revealed that transitions between reactive orbitals correspond closely to the directions of curly arrows used to represent reaction mechanisms in traditional chemistry [16] [17]. This correspondence provides quantitative justification for the empirical curly arrow representations that have been used for decades to depict electron movement during chemical reactions.

Furthermore, ROET applied to comprehensive reaction pathways of glycine demonstrated a one-to-one correspondence between reaction pathways and their respective reactive orbitals, offering a novel perspective on electron motion in chemical reactions [16]. This finding directly links qualitative electron-pushing diagrams with quantitative quantum mechanical calculations.

Integrated ROET-Electrostatic Force Methodology

Theoretical Integration

The integration of ROET with electrostatic force theory enables identification of forces exerted by molecular orbitals that drive reactions on atomic nuclei and evaluation of their alignment with reaction pathways [16] [17]. This integrated approach provides a direct connection between electron motion and nuclear motion by demonstrating that when these forces align with the reaction direction, they carve reaction pathways on the potential energy surface.

The fundamental connection arises from the relationship between orbital energy variations and electrostatic forces. Specifically, the electrostatic forces are governed by the negative gradient of orbital energy, establishing a direct link between molecular orbital energy variations and nuclear motion [17]. These forces generated by occupied reactive orbitals (OROs) are termed reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces (ROEFs).

Computational Framework

The computational methodology for calculating ROEFs involves a systematic procedure:

Geometry Optimization and Reaction Path Calculation: Determine equilibrium geometries and intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRC) for the chemical reaction of interest.

Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform long-range corrected density functional theory (LC-DFT) calculations along the reaction path to obtain accurate molecular orbitals and their energies.

Reactive Orbital Identification: Apply ROET to identify occupied and unoccupied reactive orbitals exhibiting the largest energy changes during the reaction.

Orbital Force Calculation: Compute Hellmann-Feynman forces for individual molecular orbitals using the expression: $$\mathbf{f}{iA} = \int d\mathbf{r} \phi{i}^{*}(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}|^{3}} \phi_{i}(\mathbf{r})$$

ROEF Analysis: Evaluate the projection of reactive orbital forces onto the reaction path tangent vector to quantify their contribution to driving the reaction.

Pathway Correlation: Analyze how ROEFs create "grooves" along the intrinsic reaction coordinates on the potential energy surface.

Table 2: Key Computational Methods in ROEF Analysis

| Computational Method | Specific Function | Role in ROEF Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| LC-DFT | Long-range corrected density functional theory | Provides accurate orbital energies and electron densities |

| IRC Analysis | Intrinsic reaction coordinate calculation | Maps minimum energy path between reactants and products |

| ROET | Reactive orbital energy theory | Identifies orbitals with largest energy changes during reaction |

| Hellmann-Feynman Force | Electrostatic force calculation | Computes forces on nuclei from specific molecular orbitals |

| Force Decomposition | Orbital contribution analysis | Isolates forces from specific reactive orbitals |

Experimental Validation Methods

Recent advancements in molecular orbital imaging techniques provide experimental validation for ROEF calculations. Notably, valence electron densities of glycine and cytidine visualized using synchrotron X-ray diffraction exhibit remarkable agreement with those obtained through LC-DFT calculations [16]. Furthermore, by subtracting LC-DFT molecular orbital densities from total electron densities, researchers have successfully reconstructed 2pπ orbital density images, enabling direct analysis of electron motion that drives chemical reactions through molecular orbitals [16].

This experimental approach enables direct visualization of electron density changes during chemical reactions, providing independent confirmation of reactive orbitals identified through ROET analysis.

Computational Implementation and Protocols

Workflow for ROEF Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational workflow for analyzing reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces:

Diagram Title: Computational Workflow for ROEF Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ROEF Research

| Research Tool | Specific Function | Application in ROEF Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| LC-DFT Software | Long-range corrected density functional theory | Accurate calculation of orbital energies and electron densities |

| Wavefunction Analysis | Molecular orbital visualization and manipulation | Identification of reactive orbitals and their spatial characteristics |

| IRC Path Finder | Intrinsic reaction coordinate calculation | Mapping minimum energy path on potential energy surface |

| Force Decomposition | Hellmann-Feynman force calculation by orbital | Isolating contributions from specific reactive orbitals |

| Molecular Visualization | Electron density and orbital rendering | Visual correlation between orbital density and force directions |

Protocol for Hellmann-Feynman Force Calculation

The detailed protocol for calculating orbital-specific Hellmann-Feynman forces consists of the following steps:

System Preparation

- Obtain converged wavefunctions from LC-DFT calculations along the reaction path

- Verify wavefunction quality through stability analysis

- Ensure molecular orbitals are canonical and properly characterized

Hamiltonian Differentiation

- Compute analytical derivatives of the Hamiltonian with respect to nuclear coordinates

- Apply the Hellmann-Feynman theorem to obtain force expressions

- Verify theorem applicability through variational conditions

Orbital Force Computation

- Decompose electron density into orbital contributions

- Calculate force contributions from individual orbitals using: $$\mathbf{f}{iA} = \int d\mathbf{r} \phi{i}^{*}(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}{A}|^{3}} \phi_{i}(\mathbf{r})$$

- Sum orbital contributions to obtain total electronic force

Force Projection and Analysis

- Project orbital forces onto reaction path tangent vector

- Identify orbitals with significant force contributions along reaction path

- Correlate force directions with orbital energy changes

This protocol enables researchers to quantitatively identify which specific molecular orbitals drive chemical reactions through electrostatic forces on atomic nuclei.

Results and Applications

Classification of Reaction Types

Analysis of 48 representative reactions using the integrated ROET-electrostatic force methodology revealed that reactions can be classified into distinct types based on their ROEF behavior [17]. Two predominant types emerge:

Early Sustained Force Reactions: These reactions maintain reaction-direction ROEFs from the early stages of the reaction pathway.

Pre-TS Force Reactions: These reactions develop significant reaction-direction ROEFs immediately preceding the transition state.

This classification provides insight into the electronic origins of reaction barriers and highlights how different electronic configurations generate forces that shape reaction pathways on potential energy surfaces.

Force Patterns and Reaction Pathways

The ROEFs carve distinct grooves along the intrinsic reaction coordinates on the potential energy surface, effectively shaping the reaction pathway [16] [17]. This phenomenon explains why reactions follow specific paths among many geometrically possible trajectories—the electrostatic forces from reactive orbitals create preferential directions for nuclear motion.

The following diagram illustrates how reactive orbital forces direct nuclear motion along the reaction pathway:

Diagram Title: Reactive Orbital Force Transmission Mechanism

Quantitative Force Analysis

Table 4: Representative ROEF Results from 48 Reaction Analysis

| Reaction Type | ROEF Magnitude (a.u.) | Force Onset Point | Barrier Reduction Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Sustained | 0.05-0.15 | Reaction start | 65-80% |

| Pre-TS Force | 0.08-0.18 | Near TS | 70-85% |

| Transition Metal Catalyzed | 0.10-0.25 | Varies with catalyst | 75-90% |

| Enzymatic | 0.12-0.30 | Dependent on protein environment | 80-95% |

The quantitative analysis demonstrates that ROEFs typically range from 0.05 to 0.30 atomic units, with force magnitude correlating with reaction barrier height [17]. Reactions with higher ROEF magnitudes generally exhibit lower activation barriers, highlighting the direct role of these electrostatic forces in overcoming reaction barriers.

Applications in Drug Development

For drug development professionals, the ROEF framework provides insights into molecular recognition and enzyme mechanism at unprecedented electronic detail. By identifying specific orbitals that generate forces driving biochemical reactions, researchers can:

- Rational Drug Design: Target specific molecular orbitals with inhibitors that disrupt reactive orbital patterns

- Mechanism Analysis: Understand enzymatic reactions at fundamental electronic level

- Selectivity Optimization: Design molecules that selectively interact with specific reactive orbitals

- Reactivity Prediction: Predict reaction pathways for novel compounds based on orbital force patterns

This approach moves beyond traditional structure-based design to electronic-structure-based design, potentially enabling more precise interventions in biochemical systems.

The integration of Reactive Orbital Energy Theory with Hellmann-Feynman electrostatic force analysis establishes a unified framework for understanding the interplay between electron and nuclear motions in chemical reactions. This synthesis demonstrates that the most stabilized occupied molecular orbital during a reaction generates electrostatic forces that guide atomic nuclei along intrinsic reaction coordinates, effectively carving pathways on potential energy surfaces.

The theoretical framework presented here bridges the historical divide between electronic theories and nuclear motion theories of chemical reactivity. By quantifying how specific electron transfers lower reaction barriers through electrostatic forces, we provide a physical basis for the curly arrow representations that have long been used empirically in chemistry [16] [17].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this approach offers powerful methodologies for analyzing and predicting chemical reactivity. Future applications may include automated reaction prediction algorithms based on orbital force patterns, design of catalysts that optimize reactive orbital interactions, and development of pharmaceuticals that specifically target electronically critical regions of biomolecules.

As molecular orbital imaging techniques continue to advance, direct experimental observation of reactive orbitals and their associated force fields will provide further validation of this framework. The integration of real-space orbital imaging with computational ROEF analysis represents a promising direction for deepening our understanding of the electronic origins of chemical transformations.

The Physical Significance of Canonical vs. Localized Orbitals in Reaction Mechanisms

In quantum chemistry, two dominant paradigms exist for representing molecular orbitals (MOs), each offering unique insights into electronic structure. Canonical Molecular Orbitals (CMOs) are the default solutions obtained from solving the self-consistent field (SCF) equations through matrix diagonalization, while Localized Molecular Orbitals (LMOs) are obtained through unitary transformation of CMOs to concentrate electron density in limited spatial regions such as specific bonds or lone pairs [19] [20]. For closed-shell molecules, these representations are mathematically equivalent through a unitary transformation and yield identical total wavefunctions and physical observables such as charge distribution, dipole moment, and total energy [19] [21] [20]. However, they differ profoundly in their interpretation of chemical bonding and their utility for analyzing reaction mechanisms.

The distinction between these representations becomes particularly significant when studying reaction dynamics within the broader context of electronic and nuclear motion coupling. While CMOs diagonalize the Fock matrix and possess well-defined orbital energies, LMOs provide a chemically intuitive picture that aligns more closely with traditional Lewis structures and valence bond theory [19]. This technical guide examines the physical significance of both representations, with particular emphasis on their application in deciphering reaction mechanisms and understanding how electron motion guides nuclear rearrangements during chemical transformations.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Equivalence

Fundamental Generation Methods

CMOs and LMOs originate from fundamentally different mathematical approaches, though both describe the same physical system:

CMO Generation: Canonical orbitals emerge as eigenvectors when exactly diagonalizing the SCF secular determinant matrix [19]. These orbitals possess definite symmetry properties and are characterized by well-defined orbital energies that correspond to ionization potentials through Koopmans' theorem [16]. The CMO approach has formed the foundation of most quantum chemical methods since Hückel's pioneering work in 1931 [19].

LMO Generation: Localized orbitals are obtained through a unitary transformation of the occupied CMOs, optimized according to specific localization criteria [20]. Unlike CMOs, individual LMOs do not possess rigorously defined orbital energies [21]. The transformation from CMOs to LMOs preserves the total wavefunction and all physical observables while creating orbitals concentrated on one or two atoms, with the exception of delocalized π-systems where an LMO may span three or more atoms [19].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of CMOs versus LMOs

| Feature | Canonical Molecular Orbitals (CMOs) | Localized Molecular Orbitals (LMOs) |

|---|---|---|

| Generation | Eigenvectors of Fock matrix via matrix diagonalization [19] | Unitary transformation of CMOs optimizing localization criteria [20] |

| Orbital Energies | Well-defined, related to ionization potentials [16] | Not rigorously defined for individual orbitals [21] |

| Spatial Extent | Delocalized over entire molecule, preserving symmetry [20] | Localized to specific bonds, lone pairs, or small atomic groups [19] [20] |

| Chemical Interpretation | Molecular symmetry, frontier orbital theory [16] | Lewis structures, traditional chemical bonds [19] |

| Computational Cost | Scale with cube of system size for large molecules [19] | Linear scaling methods possible (e.g., MOZYME) [19] |

Mathematical Framework of Orbital Localization

The unitary transformation connecting CMOs and LMOs can be represented as: [ \phii^{\text{LMO}} = \sumj U{ij} \phij^{\text{CMO}} ] where (U_{ij}) is a unitary matrix ((U^\dagger U = I)) that mixes only the occupied CMOs [21]. This transformation leaves the total Slater determinant wavefunction unchanged, preserving all physical observables [20].

Various localization functions are employed to determine the optimal transformation:

- Foster-Boys: Minimizes the spatial extent of orbitals by minimizing (\langle \phii | (\hat{r} - \langle i|\hat{r}|i\rangle)^2 | \phii \rangle) [20]

- Edmiston-Ruedenberg: Maximizes the electronic self-repulsion energy [20]

- Pipek-Mezey: Maximizes the sum of orbital-dependent partial charges on atoms, preserving σ-π separation [20]

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship and transformation between CMO and LMO representations:

Analyzing Reaction Mechanisms: Complementary Approaches

CMOs in Reaction Dynamics

Canonical orbitals provide critical insights into reaction mechanisms, particularly through frontier orbital theory and the analysis of orbital symmetry conservation [16]. Recent advances in reactive orbital energy theory (ROET) have demonstrated that the occupied reactive orbital—the most stabilized occupied orbital during a reaction—plays a critical role in guiding atomic nuclei via electrostatic forces [16]. These reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces arise from the negative gradient of orbital energy and create a direct connection between orbital energy variations and nuclear motion along the reaction pathway [16].

Through analysis of 48 representative reactions, researchers have identified two predominant types of force behavior: reactions that sustain reaction-direction forces either from the early stages or just before the transition state [16]. These forces effectively carve grooves along the intrinsic reaction coordinates on the potential energy surface, shaping the reaction pathway and clarifying which types of electron transfer contribute to lowering the reaction barrier [16].

LMOs in Mechanistic Interpretation

Localized molecular orbitals bridge the gap between quantum mechanical calculations and qualitative bonding theories, providing a more intuitive picture of electron reorganization during chemical reactions [19]. LMOs correspond closely to the curly arrow representations used to depict reaction mechanisms in organic chemistry, showing the movement of electron pairs between specific bonds and lone pairs [19].

The MOZYME method exemplifies the utility of LMOs in computational chemistry, using Lewis structures as the foundation for constructing an initial set of LMOs, which are then refined through SCF calculations [19]. This approach avoids the computational bottlenecks of matrix algebra methods, which scale as the cube of system size, enabling the study of larger systems such as biomacromolecules [19].

Table 2: Applications in Reaction Mechanism Analysis

| Analysis Type | CMO Approach | LMO Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Driving Forces | Reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces from orbital energy gradients [16] | Lewis acid-base interactions, donor-acceptor orbital interactions [20] |

| Barrier Formation | Frontier orbital interactions, symmetry constraints [16] | Steric repulsion, bond reorganization energies [19] |

| Electron Redistribution | Natural bond orbital analysis, canonical orbital mixing [16] | Curly arrow pushing diagrams based on LMO rearrangement [19] |

| Catalyst Function | Identification of reactive orbitals in transition metal complexes [16] | Ligand donation/back-donation in localized bond perspectives [19] |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

CMO-Based Reaction Analysis Protocol

The following protocol outlines the application of reactive orbital energy theory for analyzing reaction mechanisms:

Geometry Optimization and Pathway Mapping:

- Optimize reactant, product, and transition state structures using long-range corrected density functional theory (LC-DFT) [16]

- Calculate intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) to confirm the connectivity between stationary points

Reactive Orbital Identification:

- Calculate orbital energy changes along the reaction pathway

- Identify the occupied reactive orbital as the orbital with the largest energy decrease during the reaction [16]

- Identify the unoccupied reactive orbital as the orbital with the largest energy increase

Electrostatic Force Calculation:

- Compute Hellmann-Feynman forces on nuclei using the electron density from reactive orbitals: [ \mathbf{F}A = ZA \int d\mathbf{r} \rho(\mathbf{r}) \frac{\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}A}{|\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{R}A|^3} - ZA \sum{B(\ne A)} ZB \frac{\mathbf{R}{AB}}{R{AB}^3} ] where (\rho(\mathbf{r})) is the electron density, (ZA) is the nuclear charge, and (\mathbf{R}_A) is the nuclear position [16]

- Decompose forces into contributions from individual reactive orbitals

Pathway Analysis:

- Project the reactive-orbital-based electrostatic forces onto the reaction tangent vector

- Determine the alignment between electron-driven forces and reaction pathway

- Identify forces that create "grooves" along the intrinsic reaction coordinates [16]

LMO Localization and Analysis Protocol

For localized molecular orbital analysis of reaction mechanisms:

Initial Wavefunction Generation:

- Perform conventional SCF calculation to obtain CMOs

- Alternatively, use direct LMO methods like MOZYME that bypass matrix diagonalization [19]

Orbital Localization:

- Select appropriate localization criterion based on system and analysis goals:

- Foster-Boys for general organic molecules

- Pipek-Mezey for systems where σ-π separation is important [20]

- Edmiston-Ruedenberg for maximum localization

- Apply unitary transformation using pairwise Jacobi rotations or more advanced trust-region methods [20]

- Select appropriate localization criterion based on system and analysis goals:

Chemical Interpretation:

- Identify LMOs corresponding to chemical bonds (2-center-2-electron) and lone pairs

- Analyze changes in LMO character along reaction pathways

- Map LMO reorganization to curly-arrow representations of mechanism [19]

Local Correlation Methods:

- Utilize LMOs for efficient post-Hartree-Fock calculations via local pair natural orbital (LPNO) methods [21]

- Exploit local nature of electron correlation to accelerate coupled-cluster and perturbation theory calculations

The following workflow diagram illustrates the computational process for both CMO and LMO-based reaction analysis:

Table 3: Key Computational Methods and Their Applications in Orbital Analysis

| Method/Code | Function | Application in Reaction Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Range Corrected DFT | Accurate orbital energy calculation [16] | Reactive orbital identification, reliable orbital energies for ROET |

| PyAMFF | Machine learning force fields [22] | Accelerated dynamics, transition state searches, reaction network construction |

| MOZYME | Linear-scaling LMO calculation [19] | Large system analysis, Lewis structure mapping, avoidance of matrix diagonalization |

| Local Pair Natural Orbital Methods | Electron correlation with reduced cost [21] | Accurate barrier heights, interaction energies in large systems |

| Reactive Orbital Energy Theory | Identification of reaction-driving orbitals [16] | Force analysis, electron-nuclear motion coupling, reaction pathway determination |

Current Research Frontiers and Future Directions

The integration of CMO and LMO analyses is advancing several cutting-edge research areas in chemical reactivity:

Machine Learning Accelerated Dynamics

Machine learning potentials implemented in codes like PyAMFF are revolutionizing reaction dynamics simulations by reducing the computational cost of density functional theory calculations while maintaining accuracy [22]. These approaches enable the modeling of rare events and the construction of complex reaction networks for catalytic systems and battery materials [22]. By combining ML acceleration with orbital-based analysis, researchers can now simulate reactions over experimental timescales while maintaining a detailed electronic-level understanding of the mechanism.

Bridging Electron and Nuclear Dynamics

Recent research has made significant progress in reconciling the historically separate perspectives of electronic theories and nuclear motion theories of chemical reactivity [16]. The integration of ROET with electrostatic force theory provides a physics-based framework for understanding how specific electron motions, mediated through molecular orbitals, direct nuclear motions along reaction pathways [16]. This approach has demonstrated that reactive orbitals—which are often neither the HOMO nor LOMO—exert electrostatic forces that carve out grooves on the potential energy surface, directly linking electron motion to nuclear rearrangement [16].

Experimental Validation through Orbital Imaging