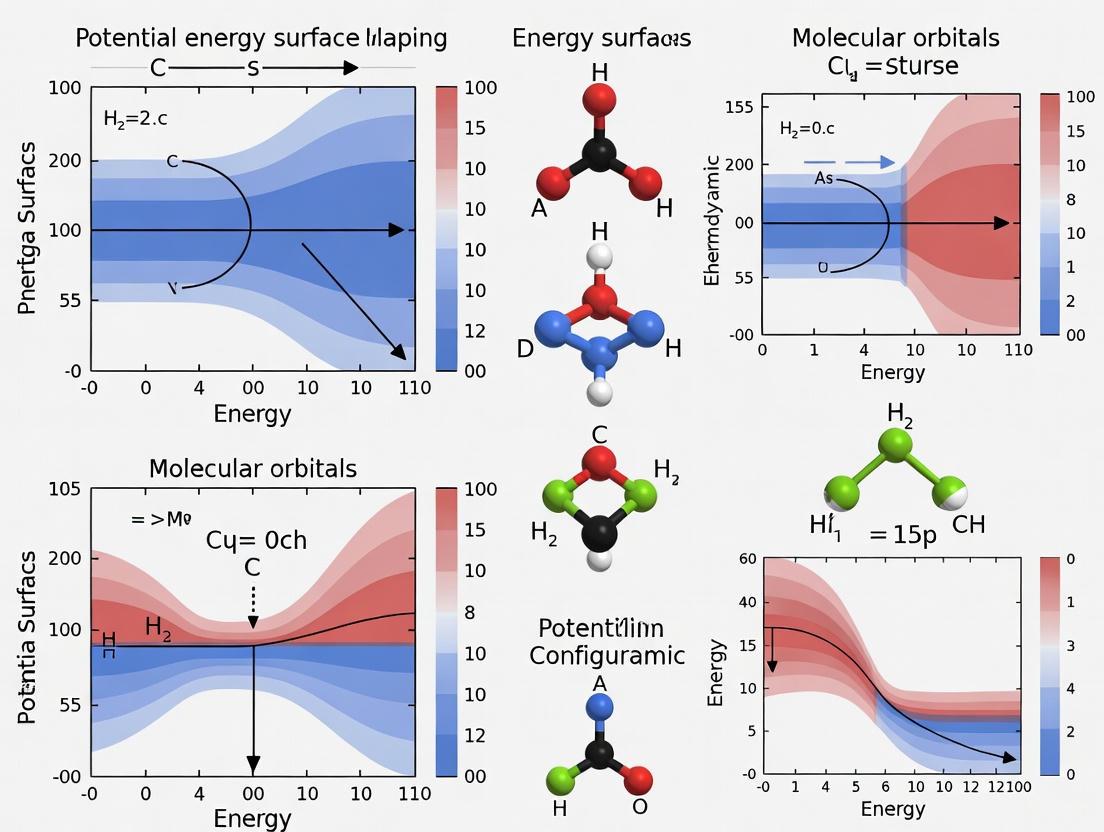

Mapping Potential Energy Surfaces for Equilibrium Structures: From Fundamental Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of potential energy surface (PES) mapping in determining molecular equilibrium structures, with special emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Mapping Potential Energy Surfaces for Equilibrium Structures: From Fundamental Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of potential energy surface (PES) mapping in determining molecular equilibrium structures, with special emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development. We examine foundational PES concepts including energy landscapes, stationary points, and conformational selection mechanisms that govern molecular stability. The article surveys cutting-edge computational methodologies from automated machine learning frameworks to quantum hybrid algorithms, while addressing significant challenges in sampling complexity and uncertainty quantification. Through rigorous validation approaches and comparative analyses across biological systems, we demonstrate how robust PES mapping enables accurate prediction of protein-ligand complexes and facilitates structure-based drug design against flexible targets. This synthesis provides researchers with both theoretical understanding and practical guidance for implementing PES mapping techniques in biomedical discovery pipelines.

Understanding Potential Energy Surfaces: The Fundamental Landscape of Molecular Equilibrium

Defining Potential Energy Surfaces and Their Role in Molecular Stability

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) is a multidimensional representation of the energy of a molecular system as a function of the positions of its atomic nuclei [1] [2]. In essence, it describes how the potential energy changes with molecular geometry, creating a conceptual "landscape" where elevations correspond to energy levels [3]. This landscape metaphor helps visualize key features: minima represent stable molecular structures, valleys correspond to reaction pathways, and mountain passes or saddle points represent transition states that must be overcome for a chemical reaction to occur [3] [2].

The mathematical definition describes the PES by the function ( V(\mathbf{r}) ), where ( \mathbf{r} ) is a vector containing the positions of all atoms [1]. For a system with ( N ) atoms, this surface exists in ( 3N-6 ) dimensions (or ( 3N-5 ) for linear molecules), after subtracting translational and rotational degrees of freedom [1]. The most well-understood region of any PES is typically the area near the minimum, which can be described using a Taylor series expansion about this point [3]:

[ U(q) = Ue + \frac{1}{2} \sumi \sumj k{ij} qi qj + \frac{1}{2} \sumi \sumj \sumk k{ijk} qi qj q_k + \cdots ]

where ( Ue ) is the energy at the minimum, ( k{ij} ) and ( k{ijk} ) are force constants, and ( qi ) are internal coordinates displacement from equilibrium [3]. The quadratic terms represent the harmonic approximation, while higher-order terms account for anharmonicity [3].

Computational Methodologies for PES Mapping

Quantum Mechanical Foundations

Calculating a PES typically requires quantum mechanical methods because classical mechanics cannot adequately describe atomic interactions at this level [1] [2]. Electronic structure methods, particularly those based on Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (DFT), provide the most accurate descriptions but scale poorly with system size (typically with the number of electrons cubed), making them prohibitively expensive for large systems or long time scales [4].

Table 1: Electronic Structure Methods for PES Development

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Medium | Medium | Large systems, materials science [4] |

| CCSD(T) | Very High | High | Accurate barrier heights, reaction energies [5] |

| CASSCF | High | Medium-High | Systems with strong correlation [5] |

| Hartree-Fock | Low | Low | Low-level reference in Δ-ML [5] |

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged recently to bridge the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and computational efficiency [6] [4]. These methods use machine learning models to approximate the DFT PES, enabling large-scale simulations with quantum-mechanical fidelity [4].

The autoplex framework represents an automated approach to PES exploration and MLIP fitting, implementing iterative exploration through data-driven random structure searching [6]. This framework gradually improves potential models to drive structural searches, requiring only DFT single-point evaluations rather than costly full relaxations [6].

Delta-Machine Learning (Δ-ML) provides a particularly cost-effective approach for developing high-level PESs [5]. This method corrects a low-level (LL) PES using a small number of high-level (HL) calculations:

[ V^{\text{HL}} = V^{\text{LL}} + \Delta V^{\text{HL-LL}} ]

where the correction term ( \Delta V^{\text{HL-LL}} ) is machine-learned from a limited set of high-level data points [5]. This approach has been successfully applied to systems like the H + CH₄ hydrogen abstraction reaction, achieving chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal mol⁻¹) with significantly reduced computational cost [5].

Workflow Automation in PES Exploration

Recent advances have focused on automating the entire MLIP development pipeline. The autoplex framework exemplifies this trend, providing modular software that interfaces with existing computational infrastructure to enable high-throughput PES exploration [6]. This automation is crucial for handling the tens of thousands of individual tasks required for comprehensive configurational space sampling, which would be practically impossible to monitor manually [6].

Table 2: Performance of Automated PES Exploration for Selected Systems

| System | Target Accuracy (eV/atom) | Structures Required | Key Polymorphs Captured |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (Elemental) | 0.01 | ~500 | Diamond, β-tin [6] |

| TiO₂ | 0.01 | ~2,000 | Rutile, Anatase, TiO₂-B [6] |

| Ti-O Binary System | 0.01 | ~5,000 | Ti₂O₃, TiO, Ti₂O [6] |

| H + CH₄ Reaction | ~0.001 ( chemical accuracy) | N/A | Reactants, TS, Products [5] |

Experimental Protocols for PES Mapping

Automated Random Structure Searching Protocol

The following protocol outlines the automated random structure searching (RSS) methodology implemented in the autoplex framework for robust PES exploration [6]:

Initialization: Define the chemical system (elements, composition ranges) and computational parameters (exchange-correlation functional, basis set, k-point mesh).

Initial Dataset Generation: Perform ab initio random structure searching (AIRSS) to create diverse initial configurations, including both near-equilibrium and high-energy structures [6].

Active Learning Loop:

- Train an initial MLIP (e.g., Gaussian Approximation Potential) on the current dataset.

- Use the MLIP to drive molecular dynamics simulations and structure searches.

- Identify regions of configuration space where the MLIP prediction uncertainty is high.

- Select the most informative new structures for DFT single-point calculations.

- Augment the training dataset with these new points.

Model Validation: Evaluate the performance of the MLIP on known stable polymorphs and physical properties (lattice parameters, elastic constants, phonon spectra).

Iterative Refinement: Repeat the active learning loop until target accuracy (e.g., 0.01 eV/atom) is achieved across relevant polymorphs and properties [6].

Δ-Machine Learning Protocol for High-Accuracy PES

This protocol details the Δ-ML approach for constructing high-accuracy PESs with reduced computational cost, as demonstrated for the H + CH₄ reaction system [5]:

Low-Level Reference Selection: Choose a previously developed analytical PES or force field that provides reasonable but not chemically accurate representation of the full system. For H + CH₄, the PES-2008 analytical surface served this purpose [5].

High-Level Reference Data Acquisition: Extract energies from a highly accurate reference PES (e.g., the PIP-NN surface by Li et al. for H + CH₄) for a judiciously selected set of configurations [5].

Correction Term Calculation: For each configuration ( i ) in the dataset, compute the energy correction: [ \Delta Vi^{\text{HL-LL}} = Vi^{\text{HL}} - V_i^{\text{LL}} ]

Machine Learning Model Training: Train a machine learning model (neural networks, Gaussian process regression, etc.) to learn the mapping from molecular geometry to ( \Delta V^{\text{HL-LL}} ).

Final PES Construction: Combine the low-level PES with the learned correction term: [ V^{\text{HL}} = V^{\text{LL}} + \text{ML}_{\Delta V} ]

Kinetic and Dynamic Validation: Perform rigorous validation using variational transition state theory with multidimensional tunneling corrections and quasiclassical trajectory calculations to ensure the PES reproduces experimental observables [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Computational Tools for PES Mapping and Analysis

| Tool/Category | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | Provide reference quantum mechanical data for PES | VASP, Gaussian, NWChem, Q-Chem [6] [5] |

| MLIP Frameworks | Machine learning models for PES fitting | GAP (Gaussian Approximation Potential), PIP-NN, NequIP [6] [5] |

| Automation Workflows | High-throughput structure searching and sampling | autoplex, AIRSS, atomate2 [6] |

| Reference Datasets | Curated PES data for MLIP training | MatPES, Materials Project [4] |

| Reaction Path Analysis | Locate minima and transition states | NEB (Nudged Elastic Band), Dimer, GROW [3] |

| Molecular Dynamics | Simulate dynamics on the PES | LAMMPS, ASE, AMBER [6] [4] |

Potential Energy Surfaces provide the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding molecular stability, chemical reactivity, and materials properties. The minima on these surfaces directly correspond to equilibrium structures, while the pathways connecting them describe transformation mechanisms [3] [2]. Recent advances in machine learning interatomic potentials, particularly automated exploration frameworks and Δ-machine learning approaches, have dramatically accelerated our ability to map these surfaces with quantum-mechanical accuracy [6] [5].

For researchers focused on equilibrium structures, these methodological innovations enable the systematic discovery of stable polymorphs, prediction of thermodynamic stability, and characterization of transformation pathways between different structural motifs. The integration of automation, active learning, and multi-fidelity modeling represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and drug development, making comprehensive PES mapping accessible for increasingly complex systems across chemistry, materials science, and pharmaceutical research.

The concept of the Potential Energy Surface (PES) is fundamental to computational chemistry and molecular modeling, providing a mathematical framework for understanding molecular stability and reactivity. A PES describes the potential energy of a system, particularly a collection of atoms, as a function of their nuclear positions [1]. Within this energy landscape, stationary points represent geometries where the energy gradient vanishes, meaning the first derivative of the energy with respect to all nuclear coordinates is zero [7] [8]. These points are critically important because they correspond to stable molecular structures and transition states that define chemical reactivity and properties.

In the context of potential energy surface mapping for equilibrium structures research, stationary points serve as the key targets for computational characterization. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation makes the concept of a PES possible by separating the fast electronic motion from the slow nuclear motion, allowing the energy to be calculated as a function of nuclear coordinates only [8]. For a system of N atoms, the PES exists in 3N-6 dimensions (3N-5 for linear molecules), where the reduction accounts for translational and rotational degrees of freedom that do not affect the internal energy [8]. The mapping and accurate identification of stationary points on this multidimensional surface enable researchers to predict molecular geometry, stability, and reaction pathways with quantum mechanical accuracy.

Mathematical Foundation of Stationary Points

Fundamental Definitions and Calculus Basis

Mathematically, stationary points occur where the gradient of the potential energy function equals zero. For a function (E(\mathbf{R})) representing the energy as a function of nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{R}), stationary points satisfy the condition [7]: [ \nabla E(\mathbf{R}) = \mathbf{0} ] This means that all components of the gradient vector, (\frac{\partial E}{\partial R_i}), must simultaneously be zero. In simpler terms, at a stationary point, the function "stops" increasing or decreasing—it becomes momentarily flat in all directions [7] [9].

The mathematical classification of stationary points depends on the second derivatives of the energy, contained in the Hessian matrix [10] [11]. The Hessian (H{ij}) is defined as: [ H{ij} = \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial Ri \partial Rj} ] The eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix determine the nature of each stationary point [10]. For a true local minimum (equilibrium geometry), all eigenvalues must be positive, indicating positive curvature in all directions. For a first-order saddle point (transition state), exactly one eigenvalue must be negative, representing the reaction path direction, while all other eigenvalues remain positive [10].

Classification of Stationary Points

Stationary points on potential energy surfaces can be systematically classified based on their mathematical properties and physical significance:

Local Minima (Equilibrium Structures): These points represent stable or metastable molecular structures where all eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix are positive [10] [8]. At these geometries, the energy increases with any small displacement of the atomic positions. A molecule may have multiple local minima corresponding to different conformers, isomers, or protonation states, with the global minimum representing the most thermodynamically stable structure [11].

First-order Saddle Points (Transition States): These stationary points possess exactly one negative eigenvalue in the Hessian matrix [10]. They represent the highest energy point along the minimum energy path connecting two local minima and correspond to transition states in chemical reactions. The eigenvector associated with the negative eigenvalue indicates the nuclear motion corresponding to the reaction coordinate [10].

Higher-order Saddle Points: These points with multiple negative eigenvalues in the Hessian are less chemically relevant but may appear in complex, multidimensional systems.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between different types of stationary points on a potential energy surface and their key identifying characteristics:

Computational Characterization of Stationary Points

Geometry Optimization Methods

Locating stationary points on potential energy surfaces requires sophisticated geometry optimization algorithms that iteratively adjust nuclear coordinates to minimize the energy gradient [10] [8]. The optimization process follows this general procedure:

Initial Structure Selection: The calculation begins with a user-provided starting geometry, which should be as close as possible to the expected final structure to minimize optimization steps [10].

Gradient Calculation: The energy gradient (first derivative) is computed at the current geometry, either analytically or through finite difference methods [10] [8].

Structure Update: The atoms are displaced in the direction of steepest descent (opposite to the gradient) to lower the energy [8]. More advanced algorithms use second derivative information (Hessian) to make more intelligent steps toward the minimum [10].

Convergence Check: The process repeats until the convergence criteria are met, typically based on maximum force components, root-mean-square forces, displacements, and energy changes between iterations [10].

The efficiency of geometry optimization depends critically on several factors: the quality of the starting geometry, the optimization algorithm employed, the coordinate system used (Cartesian, Z-matrix, or internal coordinates), and the quality of the Hessian matrix [10]. Modern computational chemistry packages like Q-Chem implement advanced optimization algorithms including Eigenvector Following (EF) and GDIIS (Geometry Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) to efficiently locate both minima and transition states [10].

Convergence Criteria and Thresholds

Successful identification of stationary points requires well-defined convergence criteria. The following table summarizes typical thresholds used in computational chemistry packages:

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization [10]

| Criterion | Threshold | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Force Component | 0.00045 au | Largest component of the gradient vector |

| RMS Force | 0.00030 au | Root-mean-square of gradient components |

| Maximum Displacement | 0.00180 au | Largest change in nuclear coordinates |

| RMS Displacement | 0.00120 au | Root-mean-square of coordinate changes |

These convergence thresholds ensure that the optimized geometry truly represents a stationary point where the energy gradient is effectively zero within chemical accuracy requirements [10].

Frequency Analysis and Stationary Point Characterization

After locating a stationary point through geometry optimization, frequency calculations are essential to determine its nature [11]. The second derivative matrix (Hessian) is computed and diagonalized to obtain vibrational frequencies, which are related to the square roots of the Hessian eigenvalues [10] [11].

The number of imaginary frequencies (negative eigenvalues) definitively characterizes the stationary point:

- Equilibrium structures (local minima): Zero imaginary frequencies [11]

- Transition states (first-order saddle points): Exactly one imaginary frequency [10] [11]

- Higher-order saddle points: Multiple imaginary frequencies

Frequency calculations also provide thermodynamic properties through statistical mechanics and enable the characterization of vibrational normal modes, including the reaction coordinate mode for transition states [11].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Transition State Optimization Protocols

Locating transition states presents unique challenges compared to minima optimization due to the saddle point nature of these stationary points. Specialized algorithms are required, with the Eigenvector Following method being particularly effective [10]. This approach maximizes the energy along one direction (the reaction coordinate) while minimizing in all other directions.

A robust protocol for transition state optimization includes:

Initial Guess Generation: Creating a structure that resembles the expected transition state, often through interpolation between reactant and product minima or using chemical intuition.

Hessian Calculation: Computing or approximating the initial Hessian matrix, which should have exactly one negative eigenvalue corresponding to the reaction coordinate [10].

Mode Following: Optimizing the geometry while following the eigenvector associated with the negative eigenvalue [10].

Verification: Confirming the optimized structure has exactly one imaginary frequency and connects the correct reactant and product minima through intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process for characterizing stationary points, from initial setup to final verification:

Automated Potential Energy Surface Exploration

Recent advances in machine learning and automation have revolutionized PES exploration. The autoplex framework represents a cutting-edge approach that automates the exploration and fitting of potential energy surfaces [6]. This method combines random structure searching (RSS) with machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) to efficiently map complex PESs with minimal human intervention.

The autoplex workflow operates through iterative cycles:

- Initial Sampling: Generating diverse initial structures through random structure searching [6]

- Quantum Mechanical Evaluation: Performing DFT single-point calculations on selected structures [6]

- Model Training: Fitting machine learning potentials to the quantum mechanical data [6]

- Exploration and Refinement: Using the MLIP to drive further exploration of the PES, focusing on uncertain regions through active learning [6]

This automated approach has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, achieving chemical accuracy (≈0.01 eV/atom) for systems like silicon allotropes with only a few hundred DFT single-point evaluations [6]. For more complex binary systems like titanium-oxygen compounds, the method remains effective though requiring more iterations to explore the greater configurational complexity [6].

Machine Learning Approaches for PES Mapping

Machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as powerful tools for PES mapping, combining near-quantum mechanical accuracy with computational efficiency sufficient for large-scale simulations [6] [12]. Several architectures have been developed:

Neural Network Potentials (NNPs): Such as the EMFF-2025 model for energetic materials, which achieves DFT-level accuracy in predicting structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics [12].

Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP): Used in the autoplex framework for their data efficiency and successful application across diverse materials systems [6].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Architectures like ViSNet and Equiformer that incorporate physical symmetries to enhance accuracy and extrapolation capabilities [12].

These MLIPs enable extensive sampling of configuration space, including both low-energy minima and high-energy transition regions, providing a more complete mapping of PESs than previously possible with direct quantum mechanical methods alone [6] [12].

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

The computational characterization of stationary points requires specialized software tools and methodologies. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" in computational chemistry:

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Stationary Point Characterization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-Chem [10] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Ab initio calculations, geometry optimization, frequency analysis | High-accuracy stationary point location with advanced algorithms |

| Gaussian [11] | Quantum Chemistry Package | Electronic structure calculations, geometry optimization | Industry-standard for organic molecule characterization |

| autoplex [6] | Automated Workflow | Machine learning-driven PES exploration | High-throughput discovery of minima and transition states |

| GFN2-xTB [8] | Semiempirical Method | Fast geometry optimization | Initial structure optimization and conformational searching |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials [6] [12] | ML Force Fields | High-accuracy, efficient PES sampling | Large-scale molecular dynamics and transition state searching |

Practical Considerations for Computational Experiments

Successful characterization of stationary points requires careful attention to computational methodology:

Level of Theory Selection: The choice of electronic structure method (DFT, HF, MP2, etc.) and basis set must balance accuracy and computational cost [10]. Density functional theory with hybrid functionals often provides the best compromise for organic molecules.

Coordinate System: Optimization in internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals) typically converges faster than Cartesian coordinates as it naturally excludes rotational and translational degrees of freedom [10] [8].

Hessian Treatment: For difficult optimizations, especially transition states, computing an initial analytical Hessian significantly improves convergence, though at increased computational cost [10].

Solvation Effects: For biological and catalytic applications, implicit or explicit solvation models are essential to accurately represent the experimental environment.

The field continues to advance with automated workflow systems like autoplex making sophisticated PES exploration accessible to non-specialists, potentially transforming how researchers approach complex problems in catalyst design, drug development, and materials discovery [6].

The process of molecular recognition, wherein biomolecules such as proteins and ligands identify and bind to one another, is fundamental to biological function and drug discovery. This process is governed by the conformational landscape—the spectrum of three-dimensional shapes a molecule can adopt—and can be visualized through the framework of the potential energy surface (PES). The PES is a multidimensional hypersurface that maps the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates, where each point represents a specific molecular geometry [13]. Within this landscape, local minima represent energetically stable structures, while saddle points correspond to transition states between them [13]. Understanding how binding partners navigate this landscape has evolved through several key models, from the early rigid lock-and-key hypothesis to the more dynamic induced-fit and conformational selection paradigms [14]. These models are not merely abstract concepts but are essential for interpreting experimental data and developing computational methods that accurately predict binding modes in structure-based drug design [15].

Historical Evolution of Binding Models

The conceptual framework for understanding enzyme-substrate interactions has progressed significantly from a static to a dynamic view of molecular recognition.

The Lock-and-Key Model

The earliest model, proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, suggested that enzymes and substrates possess rigid, complementary structures that fit together perfectly, much like a key fits into a lock [14] [16]. This model effectively explained enzyme specificity but failed to account for the structural flexibility observed in many enzymes and the stabilization of the transition state during catalysis [16].

The Induced-Fit Model

To address the limitations of the lock-and-key model, Daniel Koshland proposed the induced-fit hypothesis in 1958 [14]. This model posits that the enzyme's active site is flexible and undergoes a conformational change upon substrate binding to achieve optimal complementarity [16]. This adaptability allows enzymes to accommodate slightly varied substrates and explains how binding can stabilize the transition state, thereby lowering the activation energy of the reaction [16]. The induced-fit scenario is often viewed as a binding trajectory where the interaction between a protein and a rigid partner induces a conformational change in the protein [14].

The Conformational Selection Model

A significant paradigm shift occurred with the formulation of the conformational selection model (also known as population selection or fluctuation fit) [14]. This model proposes that an unliganded protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple conformational states. The ligand does not induce a new shape but rather selectively binds to a pre-existing conformation that is compatible with binding, thereby shifting the conformational ensemble toward this bound state [14]. This model is conceptually aligned with the Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model for allosteric interactions [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Binding Models

| Model | Mechanism | View of Protein Structure | Role of Ligand | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lock-and-Key [14] [16] | Rigid, pre-formed complementarity | Static and rigid | Passive; binds only if shape matches | Does not account for protein flexibility or transition state stabilization |

| Induced-Fit [14] [16] | Binding induces conformational change | Flexible and adaptable | Active; causes protein to change shape | Portrays the protein as largely passive before binding |

| Conformational Selection [14] | Ligand selects from pre-existing conformations | Dynamic ensemble of states | Selective; shifts equilibrium | Can be difficult to distinguish experimentally from induced-fit |

The Extended Conformational Selection Model and the Energy Landscape

Recent advances, particularly from single-molecule and NMR studies, reveal that binding mechanisms are more complex and integrated than the original models suggest. An extended conformational selection model has been proposed, which embraces a repertoire of selection and adjustment processes [14].

In this extended model, the binding process is an "interdependent protein dance" [14]. The mutual encounter involves a series of conditional steps where the next conformational change by one partner depends on the preceding change by the other. This process can be visualized as a trajectory across the PES, where not only do the partners' conformations change, but their mutual encounter also alters the shape of the energy landscape itself for both partners [14]. Electrostatic and water-mediated hydrogen-bonding signals that emerge as the partners approach change their environment and thus their energy landscape [14].

The lock-and-key, induced-fit, and original conformational selection models can all be viewed as special cases of this extended model [14]. The mechanism can shift along a spectrum toward induced-fit behavior under certain conditions, including: (i) strong, long-range ionic interactions or directed hydrogen-bond interactions; (ii) high partner concentration; and (iii) large differences in size or cooperativity between the binding partners [14].

Computational Mapping of the Conformational Landscape

Computational methods are indispensable for probing the PES and distinguishing between binding mechanisms. These methods can be broadly categorized into quantum mechanical (QM) approaches and force field methods [17].

Quantum Mechanical and Force Field Methods

QM methods, such as density functional theory (DFT), solve the Schrödinger equation to determine a system's electronic structure and energy. While highly accurate, they are computationally expensive and typically limited to small systems [17]. In contrast, force field methods use simpler functional relationships to map the system's energy to atomic positions and charges, making them more efficient for large-scale systems like proteins [17]. Force fields are critical for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which integrate Newton's equations of motion to simulate atomic movements over time [13].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Potential Energy Surface Mapping

| Method Category | Key Principle | Representative Applications | Computational Cost | Key Limitation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanical (QM) [17] | Solves Schrödinger equation for electrons | Accurate PES for small molecules; reaction mechanism studies | Very High (e.g., CCSD(T) scales ∝ N⁷) | Intractable for large biological systems | |

| Classical Force Fields [17] | Empirical potentials for bonds, angles, non-bonded terms | MD simulations of protein dynamics; adsorption; diffusion | Low | Cannot model bond breaking/formation | |

| Reactive Force Fields (ReaxFF) [17] | Bond-order potentials allow bond formation/breaking | Reactive processes in complex systems (e.g., catalysis) | Medium | Parameterization is complex | |

| Machine Learning Force Fields [17] | ML models trained on QM data for energy/forces | High-accuracy MD at near-QM speed | Low (after training) | High (for training) | Requires large QM datasets for training |

Global Optimization for Locating Minima

The conformational landscape is characterized by a vast number of local minima. Global optimization (GO) methods are used to locate the global minimum—the most stable configuration—on this complex PES [13]. These methods typically combine a global search with local refinement and are classified as stochastic or deterministic [13].

Stochastic methods incorporate randomness and are powerful for broadly exploring complex landscapes. Key algorithms include:

- Genetic Algorithms (GAs): Apply evolutionary principles (selection, crossover, mutation) to a population of structures [13].

- Basin Hopping (BH): Transforms the PES into a set of interwoven local minima, simplifying the landscape for more efficient exploration [13].

- Simulated Annealing (SA): Uses a stochastic temperature-cooling scheme to help the system escape local minima [13].

Deterministic methods rely on analytical information (e.g., energy gradients) to guide the search. These include methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Single-Ended methods that follow defined rules based on physical principles [13]. A major challenge is the exponential scaling in the number of local minima with system size, making GO a demanding computational task [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Induced-Fit Docking Molecular Dynamics (IFD-MD)

The IFD-MD protocol from Schrödinger is a modern computational solution designed to predict accurate protein-ligand binding modes when significant conformational changes are involved [15]. This method was developed to address the limitations of rigid-receptor docking and earlier induced-fit docking algorithms, which had limited sampling and sometimes failed to identify native-like poses [15].

Detailed IFD-MD Workflow [15]:

- Initial Pose Generation: Pharmacophore docking is performed using the Phase software to generate initial ligand poses.

- Structure Refinement: The protein structure is refined around each ligand pose using the Prime protein modeling program.

- Re-docking: The refined structures are re-docked with the Glide docking software in an iterative process.

- Hydration Site Analysis: Thermodynamic properties of water molecules in the binding pocket are calculated using WaterMap to inform water placement.

- System Equilibration: A short molecular dynamics simulation is run to equilibrate the system.

- Pose Stability Assessment: The stability of the ligand poses is evaluated using metadynamics (MtD) simulations, and the poses are scored.

IFD-MD is reported to be computationally much more efficient than brute-force MD simulations and has demonstrated a high success rate (90% or better) in reproducing key features of crystal structures in test cases [15].

A Representative Study: Exploring Interactions with Tyr48

A combined computational study on aldose reductase (ALR) illustrates the application of induced-fit methodologies to probe specific interactions [18]:

- Objective: To explore key hydrogen bond interactions with Tyr48 in the polyol pathway.

- Methods:

- Homology Modeling: A stereo-chemically valid model of the ALR-NADP+ complex was developed.

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A statistically significant five-point pharmacophore model was designed based on a set of 54 thiazolidinedione derivatives.

- Induced-Fit Docking: Docking protocols were applied to the ALR protein with and without its NADP+ cofactor to identify binding modes that facilitate hydrogen bonds with Tyr48.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations were used to analyze structural changes in Tyr48 and Asp43 during binding, confirming the role of Tyr48 in maintaining critical hydrogen bonds.

- Outcome: The protocol helped design new molecules with improved predicted inhibitory activity, demonstrating the utility of such methods in drug design [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Conformational Landscape Research

| Tool/Solution Name | Type/Provider | Primary Function in Research | Key Application in Binding Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFD-MD [15] | Integrated Workflow (Schrödinger) | Predicts protein-ligand binding modes with receptor flexibility | Solves the induced-fit docking problem for drug discovery projects where backbone motion is moderate. |

| Glide [15] | Docking Software (Schrödinger) | Performs high-throughput molecular docking | Used within IFD-MD for pose generation and scoring. |

| Prime [15] | Protein Modeling Software (Schrödinger) | Models loop conformations and refines protein structure | Refines the protein binding site around the ligand pose in IFD-MD. |

| WaterMap [15] | Solvation Analysis Tool (Schrödinger) | Calculates thermodynamic properties of hydration sites | Informs the placement of water molecules in the binding pocket during IFD-MD. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) [15] | Simulation Method | Simulates physical movements of atoms over time | Used for system equilibration and pose stability assessment in IFD-MD; fundamental for sampling conformational ensembles. |

| Metadynamics (MtD) [15] | Enhanced Sampling Method | Accelerates rare events in MD simulations | Assesses the stability of ligand poses in IFD-MD by efficiently exploring free energy landscapes. |

| Global Reaction Route Mapping (GRRM) [13] | Global Optimization Algorithm | Explores reaction pathways and PES | An automated method to locate transition states and minima, enabling comprehensive PES mapping. |

The understanding of molecular recognition has evolved from simplistic, static models to a sophisticated view grounded in the statistical thermodynamics of the conformational landscape. The extended conformational selection model, which integrates both selection and adjustment processes, provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting how proteins and ligands find each other on a complex, multi-dimensional PES [14]. Computational methods are crucial for exploring this landscape, with techniques like IFD-MD and global optimization algorithms enabling researchers to predict binding modes and reaction pathways with increasing reliability [13] [15]. As force field methods, including those powered by machine learning, continue to advance, they promise to unlock even deeper insights into conformational dynamics and accelerate the rational design of therapeutics and catalysts [17].

Allosteric Regulation and Population Shifts in Protein Energy Landscapes

Allostery is a fundamental biological phenomenon characterized by the transmission of signals between distal sites within a macromolecule to modulate its function. Traditionally, models of allostery focused on discrete conformational changes between "tense" (T) and "relaxed" (R) states as the primary mechanism through which ligand binding alters protein activity [19]. The modern understanding, however, has evolved to recognize that allosteric regulation involves sophisticated shifts across protein energy landscapes, where proteins exist as ensembles of conformations rather than single rigid structures [20]. This paradigm shift acknowledges the crucial role of protein dynamics and population shifts in facilitating allosteric communication, moving beyond purely structural models to incorporate the statistical nature of conformational ensembles and their energetic distributions.

The investigation of allosteric mechanisms now increasingly relies on mapping potential energy surfaces (PESs) that describe the energetic relationships between these conformational states [5]. Understanding these landscapes provides the foundation for deciphering how proteins regulate activity through long-range communications, offering unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention in diseases ranging from cancer to viral infections [21]. This whitepaper examines the current state of research into allosteric regulation through the lens of energy landscape theory, highlighting experimental and computational approaches that illuminate population shifts and their functional consequences.

Fundamental Principles of Allosteric Energy Landscapes

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Context

The conceptual framework for understanding allostery has undergone significant evolution since the original Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) and Koshland-Némethy-Filmer (KNF) models [19]. These classical models established the fundamental principle that proteins can exist in multiple equilibrium states, with ligand binding shifting this equilibrium. Contemporary research has expanded this view to recognize that allosteric proteins sample a broad ensemble of conformations along complex energy landscapes, with allosteric effectors stabilizing specific subsets of these conformations [20].

The energy landscape perspective conceptualizes proteins as navigating a multidimensional potential energy surface, where local minima represent metastable conformational states and barriers between them determine transition rates. Allosteric modulators reshape this landscape by altering the relative energies of different basins, thereby changing the population distribution across the conformational ensemble [22]. This population shift model explains how binding at one site can influence structure and dynamics at distant functional sites without requiring substantial structural rearrangements.

Key Components of Allosteric Networks

Allosteric communication in proteins relies on specific structural and dynamic elements that transmit information between distal sites. Research has identified several conserved features that facilitate these long-range interactions:

- Flexible loops and linkers: Intrinsically disordered regions often serve as dynamic allosteric regulators, as exemplified by loop 11-12 in chorismate mutase, which transmits allosteric signals over 20 Å despite its structural flexibility [19].

- Switch regions: Defined structural elements that undergo conformational changes, such as the switch I and switch II regions in KRAS that modulate effector binding through mutation-induced stabilization of active conformations [23].

- Central structural cores: Secondary structure elements like β-sheets often serve as hubs for allosteric communication, transmitting conformational changes between distant functional sites, as observed in KRAS where the central β-sheet links the core to the RAF1 binding interface [23].

- Allosteric networks: Residue networks that communicate through correlated motions, with specific "hotspot" residues mediating long-range interactions, such as residues L6, E37, D57, and R97 in KRAS [23].

Table 1: Key Elements of Allosteric Communication Networks

| Element Type | Structural Characteristics | Functional Role | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Loops | Dynamic, often partially disordered | Transient interactions, electrostatic modulation | Chorismate mutase loop 11-12 [19] |

| Switch Regions | Defined secondary structure elements | Conformational switching between states | KRAS switch I/II [23] |

| Central β-Sheets | Stable structural core | Information transmission hub | KRAS central sheet [23] |

| Hydrophobic Cores | Packed hydrophobic residues | Stability maintenance, coupling motions | GPCR transmembrane domains [22] |

Experimental Approaches for Mapping Allosteric Landscapes

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides powerful insights into protein dynamics and allosteric mechanisms at atomic resolution. The application of NMR to chorismate mutase (CM) revealed how a flexible, distal loop (loop 11-12) regulates activity despite being located over 20 Å from the active site [19].

Experimental Protocol: NMR Analysis of Allosteric Mechanisms

Sample Preparation: Prepare uniformly 15N- and 13C-labeled CM protein (≈60 kDa homodimer) in appropriate buffer systems. Generate mutant constructs (e.g., D215A, E219A, T226I) through site-directed mutagenesis to probe specific residue functions.

Backbone Assignment: Conduct triple-resonance experiments (HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCACB, CBCACONH) to assign backbone amide resonances. Note that significant signal broadening for residues 214-220 in loop 11-12 indicates extensive dynamics on the μs-ms timescale.

Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE):

- Introduce a paramagnetic label (e.g., MTSL) at specific positions in loop 11-12

- Measure PRE effects on active site residues to detect transient interactions

- Compare PRE profiles in Trp-bound (activator) vs. Tyr-bound (inhibitor) states

- Results demonstrate loop 11-12 excursions toward the active site only occur with Trp bound, despite identical ground state structures

Electrostatic Analysis: Employ novel NMR approaches to map changes in chemical shifts that report on alterations in charge distribution around the active site mediated by loop dynamics.

This methodology revealed that the D215A mutation in loop 11-12 dramatically reduces CM activity at pH 7.5 but not pH 6.5, indicating electrostatic regulation, while the conformational equilibrium between T and R states remains largely unchanged [19].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Markov State Modeling

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level temporal resolution of allosteric processes, complementing experimental approaches. Recent work on KRAS demonstrates the power of integrating MD with Markov State Modeling (MSM) to elucidate allosteric mechanisms [23].

Experimental Protocol: MD/MSM Analysis of KRAS Allostery

System Setup:

- Construct simulation systems for KRAS wild-type and oncogenic mutants (G12V, G13D, Q61R) in complex with RAF1

- Solvate in explicit water with appropriate ion concentration for physiological conditions

- Employ AMBER or CHARMM force fields with parameters for GTP/GDP

Enhanced Sampling Simulations:

- Perform microsecond-scale MD simulations using GPUs or specialized hardware

- Utilize replica-exchange or metadynamics to improve conformational sampling

- Focus on switch I (residues 25-40) and switch II (residues 57-75) dynamics

Markov State Modeling:

- Cluster simulation trajectories into microstates based on structural similarity

- Construct transition probability matrices between microstates

- Identify macrostates through Perron cluster analysis

- Calculate transition pathways and rates between functional states

Mutational Scanning & Binding Analysis:

- Perform in silico alanine scanning of binding interface residues

- Calculate binding free energies using MM-GBSA/PBSA methods

- Identify affinity hotspots (e.g., Y40, E37, D38, D33 in KRAS-RAF1)

This approach revealed that oncogenic mutations stabilize open active conformations of KRAS by differentially modulating switch region flexibility: G12V rigidifies both switches, G13D moderately reduces switch I flexibility while increasing switch II dynamics, and Q61R increases switch II flexibility and expands functional macrostates [23].

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for mapping allosteric energy landscapes

Advanced Computational Methods for Energy Landscape Characterization

Delta-Machine Learning for Potential Energy Surfaces

The development of accurate potential energy surfaces (PESs) has been revolutionized by machine learning approaches, particularly Δ-machine learning (Δ-ML) [5]. This method enables the construction of high-level PESs with significantly reduced computational cost by combining large numbers of low-level calculations with selective high-level corrections.

Methodology: Δ-ML for Protein Energy Surfaces

Low-Level Data Generation:

- Generate extensive conformational sampling using molecular dynamics with analytical force fields or semi-empirical quantum methods

- For the H + CH4 reaction system, use analytical VB-MM-type PES as low-level reference [5]

High-Level Correction:

- Select judiciously chosen configurations for high-level ab initio calculation (e.g., UCCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ)

- Calculate energy differences: ΔVHL-LL = VHL - VLL

- Train machine learning model (neural networks, GPR) on correction term

Combined PES Construction:

- Construct final PES: VHL = VLL + ΔVHL-LL

- Validate against experimental kinetics and dynamics data

- Achieve chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal mol⁻¹) with dramatically reduced computational cost

This approach has been successfully applied to model reaction dynamics, such as the H + CH4 hydrogen abstraction reaction, and can be extended to characterize allosteric conformational changes in proteins [5].

Allosteric Network Analysis

Network-based analysis of allosteric communication identifies pathways and residues critical for long-range information transfer in proteins [23] [21].

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Residue Network Analysis

Trajectory Processing:

- Collect conformational ensembles from MD simulations

- Align trajectories to reference structure

- Calculate pairwise correlations between residue motions

Network Construction:

- Represent protein as graph with residues as nodes

- Define edges based on inter-residue contacts or correlations

- Weight edges by interaction strength or correlation magnitude

Pathway Analysis:

- Identify shortest/suboptimal paths between allosteric and active sites

- Calculate betweenness centrality to identify key relay residues

- Detect communities of strongly correlated residues

Experimental Validation:

- Design mutations to perturb predicted hotspot residues

- Measure effects on allosteric coupling using functional assays

- Compare with computational predictions

Application to KRAS identified critical residues (L6, E37, D57, R97) mediating long-range interactions between the protein core and RAF1 binding interface [23]. Similarly, analysis of hACE2 revealed transmission pathways from allosteric sites to the spike RBD interface [21].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Allosteric Landscape Mapping

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Application | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microsecond MD Simulations | Newtonian mechanics with empirical force fields | Conformational sampling, dynamics | Atomic-level trajectory of allosteric transitions [23] |

| Markov State Modeling | Stochastic process theory, eigenvalue decomposition | State decomposition, kinetics | Identifies metastable states and transition pathways [23] |

| Δ-Machine Learning | Machine learning correction of low-level PES | High-accuracy energy surfaces | Chemical accuracy with reduced computational cost [5] |

| Dynamic Network Analysis | Graph theory, correlation analysis | Allosteric pathways | Identifies communication routes and hotspot residues [23] [21] |

| MM-GBSA/PBSA | Thermodynamic integration, continuum solvation | Binding affinity calculation | Quantifies energetic contributions of residues [23] |

Case Studies in Allosteric Regulation

Flexible Loop-Mediated Allostery in Chorismate Mutase

Chorismate mutase represents a paradigm for understanding how flexible, distal structural elements regulate enzyme activity through allosteric mechanisms. This homodimeric enzyme, critical for aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, is regulated by tryptophan (activator) and tyrosine (inhibitor) binding at a site over 25 Å from the active site [19].

Despite nearly identical NMR spectra for Trp-bound and Tyr-bound states, CM exhibits markedly different activity profiles, suggesting alternative mechanisms beyond classical conformational changes. Research reveals that loop 11-12 (residues 212-226), while structurally invisible in crystal structures due to flexibility, plays a crucial regulatory role. Key findings include:

- The D215A mutation within loop 11-12 dramatically reduces activity at pH 7.5 but not pH 6.5, indicating electrostatic regulation

- Paramagnetic labeling shows loop 11-12 undergoes transient excursions toward the active site only when activator (Trp) is bound

- The loop modulates active site electrostatics, providing another control mechanism for enzymatic activity

- This represents a sophisticated allosteric process where a flexible, distal loop couples functionally to both effector binding region and active site

This case demonstrates that allosteric regulation can occur through dynamic and electrostatic mechanisms without major conformational rearrangements, expanding our understanding of allosteric mechanisms beyond classical models [19].

Intracellular Allosteric Modulation of GPCR G Protein Selectivity

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest family of drug targets, and recent research demonstrates how intracellular allosteric modulators can reprogram their G protein selectivity [22]. The neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1) study reveals fundamental principles of allosteric control:

Experimental Protocol: GPCR Allosteric Modulation Studies

TRUPATH BRET Assays:

- Express NTSR1 with 14 different Gα protein BRET sensors in HEK293T cells

- Treat with ligands: endogenous neurotensin (NT), PD149163, SBI-553, SR142948A

- Measure ligand-induced G protein activation through BRET signals

Intracellular Allosteric Modulation:

- Characterize SBI-553 binding at intracellular GPCR-transducer interface

- Test combination treatments: SBI-553 + NT to assess allosteric modulation

- Analyze effects on G protein subtype selectivity and bias

Structure-Based Drug Design:

- Use structural models of NTSR1-transducer complexes

- Design modified SBI-553 compounds with varied steric and electronic properties

- Test for probe-independent, species-conserved selectivity profiles

Results demonstrated that SBI-553, binding intracellularly, switches NTSR1 G protein preference through direct intermolecular interactions, functioning as both "molecular bumper" (sterically preventing interactions) and "molecular glue" (stabilizing interactions) [22]. Modifications to the SBI-553 scaffold produced allosteric modulators with distinct G protein selectivity profiles, demonstrating the rational design potential of this approach.

Diagram 2: Intracellular allosteric modulation of GPCR signaling

Therapeutic Targeting of Host Receptor Allostery in Viral Entry

Targeting allosteric sites on host receptors presents a promising strategy for developing variant-agnostic antiviral therapeutics. Research on human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2), the host receptor for SARS-CoV-2 viral entry, demonstrates this approach [21].

Experimental Protocol: Allosteric Inhibition of hACE2–RBD Interaction

Allosteric Site Identification:

- Perform blind docking of reference molecule SB27012 to hACE2 surface

- Identify novel allosteric site distant from peptidase domain

- Validate site conservation across species and variants

Molecular Dynamics Validation:

- Run microsecond-scale unbiased MD simulations of hACE2–RBD complexes

- Compare systems with/without allosteric modulator bound

- Analyze effects on RBD binding interface and angiotensin II (AngII) substrate binding

Pharmacophore Modeling & Virtual Screening:

- Develop structure-based pharmacophore from critical modulator interactions

- Perform high-throughput virtual screening of ≈0.35 billion compounds

- Filter hits by docking score (<-9.5 kcal/mol) and ADMET properties

Dynamic Network Analysis:

- Construct dynamic residue networks from simulation trajectories

- Identify shortest suboptimal pathways for allosteric communication

- Validate mechanism of allosteric signal transmission

This approach identified allosteric modulators that disrupt hACE2–RBD interaction across SARS-CoV-2 variants (Beta, Delta, Omicron) while stabilizing hACE2 binding to its natural substrate AngII, preserving physiological function [21]. The dynamic network analysis revealed the pathway through which the allosteric signal propagates from the modulator site to the RBD interface.

Table 3: Allosteric Therapeutic Case Studies

| System | Allosteric Mechanism | Experimental Approaches | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chorismate Mutase | Flexible loop electrostatics and dynamics | NMR, PRE, mutagenesis | Understanding fundamental allosteric principles [19] |

| KRAS Oncoprotein | Switch region stabilization | MD/MSM, mutational scanning | Cancer therapy through allosteric inhibition [23] |

| NTSR1 GPCR | Intracellular transducer interface modulation | BRET assays, structural biology | Pathway-selective drug design [22] |

| hACE2 Receptor | Distant site perturbation of RBD interface | Docking, MD, network analysis | Variant-agnostic antiviral therapeutics [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Allosteric Studies

| Reagent/Method | Specific Application | Function/Purpose | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15N/13C-labeled proteins | NMR spectroscopy | Enables residue-specific dynamics measurement | Backbone assignment of chorismate mutase [19] |

| Paramagnetic labels (MTSL) | PRE NMR | Measures transient long-range interactions | Detecting loop 11-12 excursions in CM [19] |

| TRUPATH BRET sensors | GPCR signaling profiling | Measures G protein activation specificity | Characterizing NTSR1 G protein selectivity [22] |

| TGFα shedding assay | G protein coupling assessment | Alternative G protein activation measurement | Validating TRUPATH findings for NTSR1 [22] |

| AMBER/CHARMM force fields | Molecular dynamics simulations | Provides empirical energy functions | MD simulations of KRAS and hACE2 [23] [21] |

| Markov State Modeling | Conformational ensemble analysis | Identifies metastable states and kinetics | KRAS macrostate identification [23] |

| MM-GBSA/PBSA | Binding free energy calculation | Computes interaction energetics | KRAS-RAF1 hotspot identification [23] |

| Dynamic Network Analysis | Allosteric pathway mapping | Identifies communication routes | hACE2 allosteric signal transmission [21] |

| Δ-Machine Learning | Potential energy surface refinement | Achieves accuracy with efficiency | H + CH4 reaction PES development [5] |

The study of allosteric regulation through the lens of energy landscapes and population shifts has transformed our understanding of protein function and regulation. The cases examined herein demonstrate that allosteric mechanisms extend far beyond classical conformational selection models to include dynamic, electrostatic, and entropy-driven processes that reshape the energetic topography of protein landscapes.

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating experimental and computational approaches to achieve predictive understanding of allosteric systems. Machine learning methods, particularly Δ-ML approaches, show promise for accurately mapping complex energy landscapes with feasible computational resources [5]. The ability to rationally design allosteric modulators with specific signaling biases, as demonstrated for GPCRs [22], opens new avenues for therapeutic development with enhanced specificity and reduced side effects.

Furthermore, targeting allosteric sites on host proteins rather than rapidly mutating viral proteins represents a promising strategy for developing variant-resistant antivirals [21]. Similarly, identifying allosteric hotspots in oncoproteins like KRAS provides opportunities for addressing previously "undruggable" targets in cancer therapy [23].

As methods for characterizing energy landscapes continue to advance, particularly through integration of structural biology, spectroscopy, simulation, and machine learning, our capacity to understand and manipulate allosteric regulation will expand dramatically. This progress promises not only fundamental insights into protein function but also transformative approaches to therapeutic intervention across human diseases.

Dimensionality Challenges in Complex Biological Systems

Complex biological systems, from intracellular signaling pathways to tissue-level phenomena, are inherently high-dimensional. The proliferation of high-throughput technologies like next-generation sequencing has led to an explosion in biological data, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for analysis [24]. Dimensionality reduction (DR) has emerged as an essential tool for addressing the "curse of dimensionality" in computational biology, where the number of variables (e.g., genes, proteins) far exceeds the number of samples [25]. This technical guide examines these challenges within the specific context of potential energy surface (PES) mapping for equilibrium structures research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with methodologies to extract meaningful biological insights from complex, high-dimensional data while maintaining scientific rigor.

The fundamental challenge lies in the exponential scaling of computational resources required to characterize biological systems accurately. As noted in research on molecular systems, obtaining accurate PESs is "limited by the exponential scaling of Hilbert space, restricting quantitative predictions of experimental observables from first principles to small molecules with just a few electrons" [26]. This limitation becomes particularly acute when moving from simple molecular systems to biologically relevant complexes and cellular environments, where multiple spatial, temporal, and functional scales interact simultaneously [27].

Core Dimensionality Challenges in Biological Data

Biological systems exhibit several unique characteristics that exacerbate dimensionality challenges and distinguish them from more straightforward physical systems.

The Curse of Dimensionality in Biological Contexts

In biological data analysis, the curse of dimensionality manifests through several specific problems:

- Data sparsity and multicollinearity: Omics data are high-resolution, with the number of samples often much smaller than the number of variables due to costs or available sources, leading to data sparsity, multicollinearity, multiple testing, and overfitting [24].

- Hidden biological factors: Biological datasets contain confounders such as population structure among samples or evolutionary relationships among genes that must be carefully accounted for to avoid overfitting and false-positive discovery [24].

- Heterogeneous data integration: Biological phenomena involve multiple aspects (genetic variation, gene expression, epigenetic modifications) that cannot be fully explained using a single data type, creating challenges for integrating heterogeneous data structures [24].

Multiscale Complexity

Biological systems operate across divergent scales—from amino acid substitutions altering protein function to multicellular signaling cascades regulating physiological processes [27]. This multiscale nature introduces dimensionality challenges that extend beyond mere variable count:

- Cross-scale interactions: Perturbations to fine-grained parameters (e.g., protein modifications) can generate observable changes to coarse-grained outputs (e.g., tissue patterning), and vice versa [27].

- Scale-specific dynamics: Molecular binding, conformational switching, and diffusion occur over very small time scales, while cellular and tissue-level phenomena operate at much longer time scales, complicating unified analysis [27].

Table 1: Key Dimensionality-Related Challenges in Biological Systems

| Challenge Category | Specific Manifestations | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Generation | High-throughput sequencing, microarrays, imaging technologies | Produces vast amounts of data where features >> samples [25] |

| Multiscale Integration | Spatial, temporal, and functional scales interacting simultaneously | Prevents comprehensive "gene-to-organism" modeling [27] |

| Analytical Limitations | Exponential scaling of computational requirements | Restricts quantitative predictions to small molecular systems [26] |

| Interpretation Complexities | Non-linear relationships, higher-order interactions | Creates "black box" interpretations that obscure biological meaning [28] [24] |

Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Biological Applications

Selecting an appropriate dimensionality reduction technique is pivotal for revealing meaningful structure in high-dimensional biological data. Each method encodes specific assumptions about data geometry that must align with research objectives.

Linear Dimensionality Reduction Approaches

Linear techniques project data onto low-dimensional subspaces and offer advantages in speed and interpretability:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies orthogonal directions of maximal variance, offering speed and interpretability for exploratory plots, gene-expression compression, and sensor decorrelation [28]. PCA works by transforming a dataset into principal components, which are linear combinations of the original variables ordered by their variance [25].

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): Optimizes between- and within-class scatter for supervised tasks such as biomarker discovery, yet assumes class homoscedasticity and balanced priors [28].

- Factor Analysis (FA): Decomposes observed variables into latent factors plus noise—valuable in psychometrics and behavioral biology—but is restricted to linear signal models [28].

Nonlinear and Manifold Learning Techniques

Nonlinear methods uncover curved manifolds or high-order relations that linear projections overlook:

- t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE): Preserves local similarities and has become standard for single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. It works by constructing probability distributions over pairs of high-dimensional points and minimizing the Kullback-Leibler divergence between distributions in high- and low-dimensional spaces [25].

- Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP): Often used to visualize gene expression data and protein-protein interaction networks, effectively capturing nonlinear relationships in biological data [28] [25].

- Autoencoders: Deep learning-based DR methods that extend the field to support generative modeling and complex representation learning, particularly valuable for capturing hierarchical biological features [28].

Table 2: Dimensionality Reduction Techniques in Computational Biology

| Method | Category | Key Advantages | Biological Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Computational efficiency, interpretability | Gene expression visualization, identifying variation drivers [25] | Fails on nonlinear manifolds, sensitive to scaling [28] |

| t-SNE | Nonlinear | Effective cluster visualization, preserves local structure | Single-cell RNA-seq, identifying disease subtypes [25] | Interpretability challenges, computational intensity [28] |

| UMAP | Nonlinear | Preserves global and local structure, computational efficiency | Protein-protein interaction networks, tissue patterning [28] | Parameter sensitivity, potential false structure [29] |

| Autoencoders | Deep Learning | Handles complex nonlinearities, feature learning | Multi-omics integration, biomarker discovery [28] | "Black box" interpretation, data hunger [24] |

| Multilinear PCA | Tensor-based | Captures multi-modal structure | Imaging data, spatial transcriptomics [28] | High computational cost, sensitive to tensor shape [28] |

Potential Energy Surface Mapping and Dimensionality

Potential energy surface mapping represents a specialized application of dimensionality principles to molecular systems, with direct relevance to biological structure and drug discovery.

PES Fundamentals in Biological Context

The PES represents the total energy of a molecular system as a function of nuclear coordinates, governing structure and dynamics [26]. With high-quality PESs, computation of experimental observables becomes possible with predictive power at a quantitative level. However, the PES itself cannot be directly observed, creating a fundamental dimensionality challenge in moving from experimental measurements to energy landscapes [26].

In complex biological systems, the high-dimensional nature of PES mapping becomes computationally prohibitive. For example, full configuration interaction (FCI) calculations with large basis sets provide the highest quality for total energies but prevent "routine use for constructing full-dimensional PESs for any molecule consisting of more than a few light atoms" [26].

Machine Learning Approaches for PES Construction

Machine learning methods have emerged to address dimensionality challenges in PES development:

- Δ-Machine Learning (Δ-ML): This approach, as demonstrated in the development of a full-dimensional interaction PES for CO₂ + N₂, significantly reduces computational costs while maintaining accuracy. In one implementation, the method reduced required basis set superposition error (BSSE) calculations by approximately 97.2% while achieving a fitting error of merely 0.026 kcal/mol [30].

- PES Morphing: This technique improves PES quality by applying linear coordinate transformations based on experimental data. It "capitalizes on the correct overall topology of the reference PES and transmutes it into a new PES by stretching or compressing internal coordinates and the energy scale" [26].

- Permutation Invariant Polynomial-Neural Networks (PIP-NN): This architecture enables efficient sampling within existing datasets, allowing construction of accurate PESs with limited data points for error correction [30].

Diagram 1: PES Development and Refinement Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of potential energy surface construction, validation, and refinement using dimensionality-aware techniques.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: High-Dimensional Biological Data Processing Pipeline

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for handling high-dimensional biological data, incorporating robustness checks to mitigate dimensionality-related artifacts:

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Perform normalization to account for technical variance (e.g., batch effects, library size)

- Apply quality metrics to identify outliers and technical artifacts

- Implement feature selection to reduce dimensionality prior to downstream analysis

Dimensionality Reduction and Validation

- Apply multiple DR techniques (both linear and nonlinear) to assess consistency

- Use intrinsic dimensionality estimation to guide parameter selection

- Validate DR results through robustness testing (e.g., subsampling, parameter perturbation)

Interpretation and Biological Validation

- Identify loadings or feature contributions to principal components or embeddings

- Correlate reduced-dimensional representations with known biological covariates

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on features driving major axes of variation

Protocol: PES Mapping for Biomolecular Complexes

This specialized protocol adapts PES construction techniques for biological molecular systems:

Configuration Space Sampling

- Sample data points within the full-dimensional configuration space of the molecular complex

- Perform quantum calculations at appropriate theory level (e.g., CCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ)

- Employ active learning approaches to focus sampling on chemically relevant regions

Efficient PES Construction with Δ-ML

- Select limited data points for accurate BSSE calculations (e.g., ~1100 points from 40,930)

- Construct BSSE correction PES using PIP-NN framework

- Predict BSSE corrections for all data points using the correction PES [30]

PES Refinement via Experimental Morphing

- Compare computed observables (e.g., Feshbach resonance positions) with experimental data

- Apply morphing transformations to improve agreement with experimental measurements

- Assess sensitivity of different observables to various PES regions [26]

Diagram 2: Multiscale Biological Modeling Information Flow. This diagram illustrates how information propagates across scales in biological modeling, from quantum-level calculations to observable phenotypes.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Dimensionality-Challenged Biological Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing Clusters | Enables computationally intensive DR and PES calculations | Processing large omics datasets, quantum chemistry calculations [26] |

| Δ-ML Frameworks | Reduces computational costs of accurate quantum calculations | Constructing high-precision PES with minimal BSSE calculations [30] |

| PIP-NN Architectures | Provides permutationally invariant function approximation | Developing molecular PES without arbitrary coordinate choices [30] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Platforms | Generates high-dimensional gene expression data at cellular resolution | Identifying cell subtypes, developmental trajectories [25] |

| DR Visualization Software | Enables intuitive exploration of high-dimensional data | Interactive analysis of omics data, cluster identification [29] |

| Multiscale Modeling Environments | Integrates across temporal and spatial biological scales | Connecting molecular interactions to tissue-level phenotypes [27] |

Dimensionality challenges present significant but surmountable obstacles in the study of complex biological systems and the mapping of potential energy surfaces for equilibrium structures research. By employing appropriate dimensionality reduction techniques matched to specific biological questions, and leveraging emerging machine learning approaches for PES construction, researchers can extract meaningful patterns from high-dimensional data while maintaining physical rigor. The integration of multiscale computational approaches with experimental validation provides a pathway to overcome the current limitations in "gene-to-organism" modeling, ultimately enabling more predictive biological simulations and accelerating drug discovery efforts. As biological datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, the development of dimensionality-aware methodologies will remain essential for advancing our understanding of biological systems at molecular resolution.

Computational Approaches for PES Mapping: From Quantum Methods to Machine Learning Potentials

SA-OO-VQE for Ground and Excited States

The accurate calculation of ground and excited states is a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry, crucial for understanding photophysical properties, reaction mechanisms, and electronic processes in molecules and materials. The potential energy surface (PES), which represents the total energy of a system as a function of atomic positions, provides the foundation for exploring these properties [17]. For processes involving photoexcitation, non-radiative decay, or conical intersections, a balanced description of both ground and excited states is essential [31] [32].

Quantum computing offers a promising pathway for electronic structure calculations, with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerging as a leading algorithm for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [31]. However, conventional VQE and its excited-state extension, the Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD), face limitations when dealing with near-degenerate states and require careful selection of hyperparameters [31] [32].

The State-Averaged Orbital-Optimized Variational Quantum Eigensolver (SA-OO-VQE) addresses these limitations by combining state-averaged orbital optimization with a variational quantum algorithm, enabling a democratic description of ground and excited states [32]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, methodological framework, and implementation protocols of SA-OO-VQE within the context of PES mapping for equilibrium structures research.

Theoretical Foundations

Potential Energy Surfaces in Electronic Structure Theory

The PES is constructed under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates electronic and nuclear motions [17]. From a geometric perspective, the energy landscape plots the energy function over the configuration space of the system, enabling exploration of atomic structure properties, including minimum energy configurations and reaction rates [17]. Key features include:

- Minima: Stable equilibrium structures of reactants, products, or intermediates

- Saddle points: Transition states representing peak energy points along reaction coordinates

- Conical intersections: Points of degeneracy between electronic states crucial for photochemical processes [31] [32]

The force on each atom, derived as ( Fi = -\partial E/\partial ri ), is essential for molecular dynamics simulations and geometry optimization [17].

Quantum Computing for Electronic Structure

Quantum computers can potentially solve electronic structure problems with polynomial scaling, unlike the exponential scaling of classical methods [31]. The VQE algorithm leverages the variational principle to find ground-state energies:

[ \langle \Psi(\theta) | \hat{H} | \Psi(\theta) \rangle \ge E_0 ]