Sequential Simplex Method: A Practical Guide for Optimizing Multi-Factor Experiments in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive guide explores the sequential simplex method, a powerful model-agnostic optimization technique ideal for researchers and drug development professionals navigating complex experimental spaces with multiple interacting factors.

Sequential Simplex Method: A Practical Guide for Optimizing Multi-Factor Experiments in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the sequential simplex method, a powerful model-agnostic optimization technique ideal for researchers and drug development professionals navigating complex experimental spaces with multiple interacting factors. The article covers foundational principles, from the algorithm's origins in George Dantzig's work to its geometric interpretation of navigating response surfaces. It provides detailed methodological guidance on implementing both basic and modified simplex procedures, illustrated with real-world applications from analytical chemistry and biopharmaceutical production. The guide also addresses critical troubleshooting considerations for managing experimental noise and step size selection, while offering comparative analysis against alternative optimization approaches like Evolutionary Operation and Response Surface Methodology. Designed for practical implementation, this resource enables scientists to efficiently optimize processes ranging from analytical method development to recombinant protein production and drug formulation.

The Geometry of Optimization: Understanding Sequential Simplex Fundamentals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core connection between George Dantzig's Linear Programming and modern experimental optimization?

George Dantzig's Simplex Algorithm, developed in 1947, provides the mathematical foundation for optimizing a linear objective function subject to linear constraints [1] [2]. Modern experimental optimization builds upon this by applying the same core principle—systematically moving toward an optimum—to the real-world process of experimentation. While Dantzig optimized mathematical models, researchers now use methods like the sequential simplex to optimize experimental factors themselves, efficiently navigating multi-factor spaces to find the best combinations for desired outcomes [3].

FAQ 2: Why should I move beyond one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) experiments?

One-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) experimentation is inefficient and can lead to misleading conclusions [4]. Crucially, OFAT cannot detect interactions between factors—situations where the effect of one factor depends on the level of another [3] [4]. For example, in the corn cultivation case, the effect of fertilizer was different for basic corn versus MegaCorn Pro [4]. Multi-factor factorial designs, in contrast, allow you to efficiently explore many variables simultaneously and discover these critical interactions, leading to more robust and optimal results [3].

FAQ 3: How does the Sequential Simplex Method improve the efficiency of my experiments?

The Sequential Simplex Method is an iterative, "hill-climbing" optimization procedure [5]. It improves efficiency by using the results from one experimental run to determine the most promising conditions for the next run. This creates a direct, adaptive path towards optimal factor settings, avoiding the wasted effort of testing non-informative conditions. It systematically moves from an initial basic feasible solution to adjacent solutions with better objective function values until the optimum is found [1] [5].

FAQ 4: What are the common signs that my experimental optimization is failing to converge?

- Cycling: The simplex repeats a sequence of points without progressing to a new, better solution [5].

- Oscillation: The results fluctuate between similar values without stabilizing.

- Lack of Improvement: The objective function (e.g., yield, purity) shows no significant improvement over multiple iterations.

- Violation of Constraints: Proposed experimental conditions are infeasible or violate safety or practical limits.

FAQ 5: How do I validate the optimal conditions found by a sequential simplex procedure?

- Replication: Perform multiple experimental runs at the purported optimal conditions to confirm reproducibility and estimate variability.

- Confirmation Run: Execute a final, controlled experiment using the optimal factor settings to verify that the predicted performance is achieved.

- Model Validation: If a predictive model was used, validate it with a new set of data not used in the optimization process [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: The Simplex Algorithm Fails to Find an Improved Solution

Symptoms:

- The algorithm cycles through the same solutions.

- The objective function value does not improve after an iteration.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Degeneracy [5] | Check if a basic variable has a value of zero in the feasible solution. | Apply an anti-cycling rule (e.g., Bland's rule) to perturb the solution slightly and break the cycle [1]. |

| Incorrect Pivot Selection | Verify the calculations for the reduced cost coefficients (entering variable) and the minimum ratio test (leaving variable) [1] [7]. | Recalculate the simplex tableau. Ensure the most negative reduced cost is chosen for maximization and the minimum ratio is correctly identified. |

| Local Optimum | The solution may be a local, not global, optimum. This is less common in pure LP but possible in non-linear response surfaces. | Restart the algorithm from a different initial basic feasible solution to explore other regions of the feasible space. |

Problem 2: Poor Optimization Performance in Multi-Factor Experiments

Symptoms:

- High variability in responses.

- Inability to identify significant factors.

- The predicted optimum does not perform well in validation.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ignored Factor Interactions [4] | Analyze the data for two-factor interactions. A significant interaction means the effect of one factor depends on the level of another. | Shift from a OFAT design to a full or fractional factorial design that can estimate interactions [3] [4]. |

| Uncontrolled Noise | Review the experimental setup for sources of uncontrolled variability (e.g., environmental conditions, operator differences). | Introduce blocking into the experimental design to account for known sources of noise and reduce background variation [4]. |

| Incorrect Region of Experimentation | The initial range of factors being tested may be far from the true optimum. | Perform a screening design first to identify important factors, then use a response surface method (like simplex) to hone in on the optimum. |

Problem 3: Infeasible or Unrealistic Solutions from the Model

Symptoms:

- The algorithm indicates no feasible solution exists.

- The proposed optimal factor settings are impractical or dangerous to implement.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-constrained System | Check all constraints for consistency. Even a single contradictory constraint can make the entire problem infeasible [1]. | Re-examine the necessity and values of each constraint. Relax constraints if possible and scientifically justified. |

| Incorrectly Formulated Constraints | Verify that all variable bounds (e.g., temperature > 0, concentration ≤ 100%) are correctly specified. | Reformulate the constraints and variable bounds to accurately reflect the physical and practical limits of the experiment [1]. |

| Model does not reflect reality | The linear or simplified model may be inadequate for the complex system under study. | Consider using a more complex, non-linear model or incorporating domain expertise to refine the experimental setup and constraints. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Initial Simplex for a New Experiment

Purpose: To create a starting simplex for optimizing multiple factors.

- Select Factors: Choose the

kcontinuous factors you wish to optimize. - Define Range: Establish a feasible operating range for each factor.

- Create Initial Simplex: Generate

k+1experimental runs that form the initial simplex in thek-dimensional factor space. For example, for 2 factors, a triangle is formed. - Run Experiments: Execute the

k+1experiments in a randomized order to minimize the effect of lurking variables. - Measure Response: Record the objective function value (e.g., yield, efficiency) for each run.

Protocol 2: Executing a Sequential Simplex Iteration

Purpose: To move the simplex towards a more optimal region.

- Evaluate Vertices: Rank the responses of all current simplex vertices.

- Identify Worst: Identify the vertex with the worst response.

- Reflect: Reflect the worst point through the centroid of the opposite face to generate a new candidate point.

- Test New Point: Run the experiment at the new candidate point.

- Compare & Decide:

- If the new point is better than the worst, replace the worst point with it.

- If the new point is the best so far, consider a further expansion step.

- If the new point is worse than the second-worst, consider a contraction step.

- Check Termination: Continue iterating until the simplex converges around an optimum or a predefined number of runs is completed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experimental Optimization |

|---|---|

| Slack Variables [1] [7] | Convert inequality constraints (e.g., "resource use ≤ budget") into equalities, making them usable in the simplex algorithm. They represent "unused" resources. |

| Simplex Tableau [1] [7] | A tabular format used to perform the algebraic manipulations of the simplex algorithm efficiently. It organizes the coefficients of the objective function and constraints. |

| Factorial Design [3] [4] | An experimental design that studies the effects of two or more factors, each with multiple levels. It is used to screen for important factors and estimate interactions before detailed optimization. |

| Fractional Factorial Design [3] | A more efficient version of a full factorial design that tests only a carefully chosen subset of all possible combinations. It is used when the number of factors is large, trading some interaction detail for speed and lower cost. |

| Objective Function | The single quantitative measure (e.g., process yield, product purity, cost) that the experiment is designed to optimize. |

| 2-Iodoadenosine | 2-Iodoadenosine, CAS:35109-88-7, MF:C10H12IN5O4, MW:393.14 g/mol |

| Fenticonazole | Fenticonazole | Antifungal Agent for Research (RUO) |

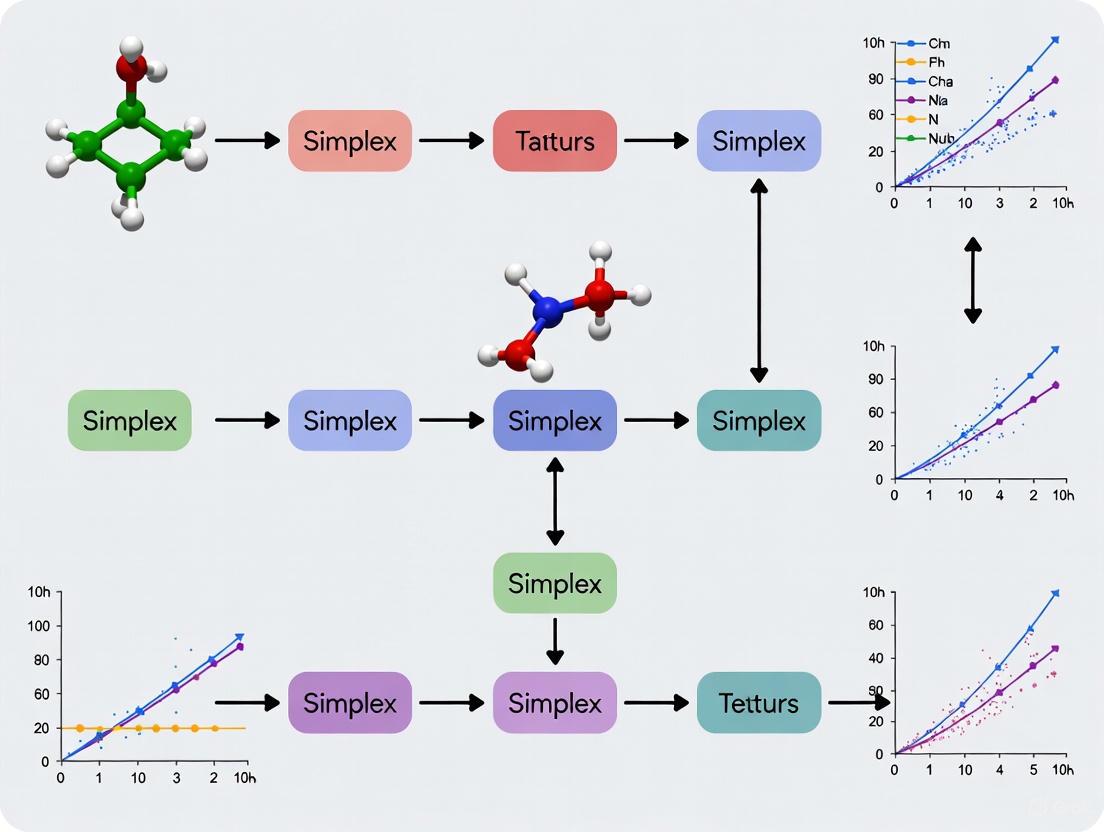

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Sequential Simplex Optimization Flow

Multi-Factor Experiment Design Logic

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What does it mean if my simplex is oscillating between the same few vertices? This typically indicates that the simplex is circling a potential optimum. According to Rule 2 of the sequential simplex method, when a new vertex yields the worst result, you should reject the vertex with the second-worst response instead to change the direction of progression [8] [9]. This helps the simplex navigate more effectively in the region of the optimum.

Q2: How do I handle a situation where the new experimental conditions fall outside feasible boundaries? Rule 4 of the method provides a solution: assign an artificially worst response to any vertex that falls outside the experimental boundaries [8]. This forces the simplex to reject this point and move back into the feasible experimental domain on the next iteration.

Q3: My optimization progress has become very slow. How can I improve convergence? The basic simplex method maintains a fixed size, which can lead to slow progress. Consider switching to the modified simplex method by Nelder and Mead, which allows for expansion and contraction steps [8] [9]. An expansion move is performed if the reflected vertex yields a much better response, rapidly accelerating progress toward the optimum.

Q4: A single vertex remains in many successive simplexes. What does this signify? When a point is retained in f+1 successive simplexes (e.g., 4 simplexes for 3 factors), it suggests a possible optimum. Apply Rule 3: re-run the experiment at this vertex [8]. If it confirms the best response, it is likely the optimum. If not, the simplex may be stuck at a false optimum, and a restart with a different initial simplex may be necessary.

Common Error Scenarios and Solutions

| Error Scenario | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex Oscillation | Simplex circling near optimum [8]. | Apply Rule 2: Reflect second-worst vertex. |

| Slow Convergence | Fixed simplex size is too small for the region [9]. | Use modified method with expansion/contraction. |

| Boundary Violation | New vertex coordinates are outside feasible domain [8]. | Apply Rule 4: Assign artifical worst response. |

| False Optimum | Vertex retained but not truly optimal [8]. | Apply Rule 3: Re-test vertex; consider re-start. |

| High Dimensionality | Number of factors (f) is large, increasing complexity [8]. | Eliminate linear parameters first to reduce dimensions [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sequential Simplex Method

Objective

To systematically optimize multiple experimental factors by navigating the multi-dimensional factor space using a sequential simplex algorithm to find the combination that yields the optimal response.

Methodology

1. Initial Simplex Construction

- For an experiment with

ffactors, construct an initial simplex withf+1vertices [8] [9]. - Each vertex represents a unique set of experimental conditions (e.g., specific concentrations, temperatures).

- The size of the initial simplex should be chosen arbitrarily based on the experimental domain [8].

2. Experiment Execution and Evaluation

- Run the experiment at each vertex of the current simplex.

- Measure the response for each vertex (e.g., yield, purity, activity).

3. Vertex Ranking and Movement

- Rank all vertices from Best (B) to Worst (W), with N representing the next-to-best [8] [9].

- Calculate the Centroid: Compute the centroid (P) of all vertices except the worst (W). For

ffactors, the centroid's coordinates are the average of the coordinates of the retained vertices [8]. - Reflect the Worst Vertex: Generate a new vertex (R) by reflecting the worst vertex through the centroid. The vector formula is: R = 2P - W [8].

4. Decision Logic for Simplex Progression The following workflow outlines the core logic for moving from one simplex to the next, including the reflection, expansion, and contraction operations.

5. Iteration and Termination

- Repeat steps 2-4, using the decision logic above, until the simplex converges on the optimum region.

- Convergence is typically signaled when the simplex tightly circles a point with little improvement in response over multiple iterations [8] [9].

- The vertex with the best observed response is reported as the optimal set of conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item or Concept | Function in Sequential Simplex Optimization |

|---|---|

| Initial Simplex | The starting geometric figure in factor space; its size and location set the initial scope of the investigation [8]. |

| Factor Space | The n-dimensional coordinate system defined by the n factors being optimized; the "landscape" being navigated [8]. |

| Response Surface | The often-unknown multidimensional surface representing the outcome (response) for every combination of factors; the simplex method navigates this surface without requiring its explicit mapping [9]. |

| Centroid (P) | The geometric center of the face opposite the worst vertex (W); the pivot point for reflection, expansion, and contraction moves [8]. |

| Reflection | The core operation that projects the worst vertex through the centroid to explore a new, potentially better region of the factor space [8] [9]. |

| Expansion | (Modified Method) An operation following a successful reflection, which extends the simplex further in that direction to accelerate progress if the reflection was much better [9]. |

| Contraction | (Modified Method) An operation used when a reflection is poor, which shrinks the simplex to hone in on a promising area [9]. |

| Linear Optimization Oracle | In advanced geometric methods, an efficient algorithm used to optimize a linear function over the feasible set polytope, aiding in decomposition for neural combinatorial optimization [10]. |

| Perospirone | Perospirone, CAS:150915-41-6, MF:C23H30N4O2S, MW:426.6 g/mol |

| Fmoc-Glu(OAll)-OH | Fmoc-Glu(OAll)-OH, CAS:133464-46-7, MF:C23H23NO6, MW:409.4 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental geometric concept behind the Basic Simplex Algorithm?

The Basic Simplex Algorithm uses a regular geometric figure called a simplex to navigate the experimental domain [11] [9]. For an optimization involving k factors or variables, the simplex is defined by k+1 vertices [12] [9]. In two dimensions, this simplex is a triangle; in three dimensions, it is a tetrahedron; and for higher dimensions, it is a hyperpolyhedron or simplicial cone [1] [11] [12]. The algorithm proceeds by moving this fixed-size figure through the experimental space toward the optimal region.

Q2: What does "fixed-size" mean in the context of the Basic Simplex method?

"Fixed-size" means that the geometric figure (the simplex) does not change in size during the optimization process [12] [9]. The initial simplex, defined by the researcher, remains a regular figure with constant edge lengths as it is reflected across its faces. This is a key difference from the Modified Simplex method, where the simplex can expand or contract [12] [9].

Q3: What are the primary moves or operations in the Basic Simplex Algorithm?

The core operation in the Basic Simplex method is reflection [9]. At each step, the vertex yielding the worst response is identified and rejected. This worst vertex is then reflected through the opposite face (or line, in two dimensions) of the simplex to generate a new vertex. The new vertex and the remaining vertices from the previous simplex form the new simplex [9]. This reflection process is repeated sequentially.

Q4: What rules govern the movement of the simplex?

The algorithm is governed by two main rules [9]:

- Rule 1: The new simplex is formed by reflecting the worst vertex through the face defined by the remaining vertices. This is the standard move.

- Rule 2: If the newly reflected vertex is again the worst in the new simplex, the vertex with the second-worst response is reflected instead. This rule prevents the simplex from oscillating between two points and helps change direction, particularly when near the optimum.

Q5: What is a critical step for the researcher when using the Basic Simplex method?

Choosing the size of the initial simplex is a crucial and often difficult step [12]. Because the simplex size remains fixed, an initial simplex that is too large may miss fine details of the response surface, while one that is too small will make the progression toward the optimum very slow. This decision often relies on the researcher's experience and prior knowledge of the system being studied [12].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Convergence | The initial simplex size is too small. | Use prior knowledge of the system to choose a larger, more appropriate initial simplex size [12]. |

| Oscillation (Simplex moves back and forth between two points) | The simplex is reflecting the worst vertex back to its original position (a violation of Rule 1) [9]. | Apply Rule 2: Identify and reflect the vertex with the second-worst response instead of the worst one to change direction [9]. |

| Missing the Optimal Region | The initial simplex size is too large, making it difficult to locate the precise optimum [12]. | Restart the optimization with a smaller initial simplex focused on the most promising area found in the initial broad search. |

| Circling Around a Point | The simplex is likely in the vicinity of the optimum. Subsequent moves keep one vertex (the best one) constant [9]. | The retained vertex is likely near the optimum. Terminate the procedure or use the final simplex to define a new, smaller simplex for a more precise location. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines the essential conceptual "reagents" or components needed to set up a Basic Simplex experiment.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Initial Simplex | The regular geometric starting figure (e.g., a triangle for 2 variables) defined by k+1 experimental points. It sets the scope and direction of the optimization [12] [9]. |

Objective Function (f(x)) |

The measurable response (e.g., yield, sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio) that the algorithm seeks to minimize or maximize [11]. |

Experimental Variables (x1, x2,... xk) |

The independent factors (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration) that are adjusted to optimize the objective function [12]. |

| Reflection Operation | The computational procedure that generates a new candidate vertex by mirroring the worst vertex, enabling the simplex to move through the experimental domain [9]. |

| Stopping Criterion | A pre-defined rule (e.g., no significant improvement after several steps, or circling behavior) to halt the optimization process [9]. |

Basic Simplex Movement Protocol

The diagram below visualizes the logic and rules governing the movement of a fixed-size simplex.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the movements in the Basic Simplex Algorithm.

| Aspect | Description in Basic Simplex |

|---|---|

| Figure Dimensionality | k dimensions, defined by k+1 vertices, where k is the number of experimental variables [12] [9]. |

| Primary Move | Reflection [9]. |

| Figure Size | Fixed throughout the procedure [12] [9]. |

| Rules for Direction Change | Rule 2 (Reflect the second-worst vertex) is applied when reflection of the worst vertex fails [9]. |

| Typical Termination Signal | The simplex begins to circle around a single, retained vertex [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the Nelder-Mead method and the traditional simplex algorithm for linear programming?

The Nelder-Mead method is a direct search heuristic for nonlinear optimization problems where derivatives may not be known, and it uses a geometric simplex of n+1 points in n dimensions [13]. In contrast, the traditional simplex algorithm developed by Dantzig is designed exclusively for linear programming problems and operates by moving along the edges of the feasible region defined by linear constraints to find the optimal solution [1]. The two methods are distinct and should not be confused.

Q2: During an iteration, my reflected point is better than the current best point. What operation does the algorithm perform next, and what is the purpose?

This scenario triggers an Expansion operation [13] [14]. The algorithm has found a highly promising direction, so it tests an expansion point further out along the reflection direction. The purpose is to accelerate progress downhill by taking a larger step in this promising direction. If the expansion point is better than the reflection point, it is accepted; otherwise, the reflected point is accepted [15].

Q3: What does the algorithm do when the reflection point is worse than the worst point in the simplex?

When the reflection point is worse than the worst point, the algorithm attempts a Contraction Inside operation [13] [14]. It tests a point between the worst point and the centroid. If this inside contraction point is better than the worst point, it is accepted. If not, the algorithm performs a Shrink operation, moving all points (except the best) towards the best point to refine the search area [15].

Q4: How should I initialize the simplex, and what are common termination criteria?

A common initialization strategy, used in implementations like MATLAB's fminsearch, starts from a user-given point xâ‚€. The other n vertices are set to xâ‚€ + Ï„áµ¢eáµ¢, where eáµ¢ is a unit vector, and Ï„áµ¢ is a small step (e.g., 0.05 if the component is non-zero, 0.00025 if it is zero) [16]. Termination is often based on the simplex becoming small enough or the function values at the vertices becoming sufficiently close [14] [16].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: The optimization converges to a non-stationary point or gets stuck.

- Potential Cause: The Nelder-Mead method is a heuristic and can converge to points that are not true minima, especially on problems that do not meet stronger conditions required for modern methods [13].

- Solution: Restart the algorithm from different initial points and compare the results. Empirical evidence suggests that multiple shorter runs can yield better overall performance than a single long run [15].

Problem 2: The algorithm is making very slow progress in later iterations.

- Potential Cause: The simplex has shrunk very small and is oozing down a shallow valley [13], or it is trying to "pass through the eye of a needle" [13].

- Solution: This is part of the expected behavior as the algorithm contracts around a suspected minimum. Check the termination criteria; if the standard deviation of the function values or the size of the simplex is below your tolerance, the algorithm can be stopped [16].

Problem 3: The algorithm fails to improve the worst point after reflection, expansion, and contraction attempts.

- Potential Cause: This is a known rare situation where the simplex is on the face of a "valley" or the problem is highly irregular [15].

- Solution: The algorithm handles this by default with a Shrink operation. Shrinking the simplex towards the best point helps the algorithm to reorient itself and can be crucial for escaping these stuck configurations [13] [15].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Nelder-Mead Algorithm

This protocol outlines the core iterative procedure of the Nelder-Mead method, focusing on the expansion and contraction operations.

1. Initialization

- Define the objective function

f(x)to be minimized and the number of dimensionsn. - Construct an initial simplex of

n+1vertices. For a given starting pointx₀, a common approach is to create the other vertices asx₀ + τᵢeᵢ, whereeᵢare unit vectors andτᵢare small step sizes [16].

2. Algorithm Iteration Repeat the following steps until a termination criterion is met:

- Step 1: Ordering. Evaluate

f(x)at each vertex and order the points so thatf(xâ‚) ≤ f(xâ‚‚) ≤ ... ≤ f(xₙ₊â‚). Identify the best (xâ‚), worst (xₙ₊â‚), and second-worst (xâ‚™) points [13]. - Step 2: Calculate Centroid. Calculate the centroid

xâ‚’of thenbest points (excludingxₙ₊â‚) [13]. - Step 3: Reflection.

- Step 4: Expansion.

- Step 5: Contraction.

- This step is reached if

f(x_r) ≥ f(xₙ). - Outside Contraction: If

f(x_r) < f(xₙ₊â‚), compute the outside contraction point:x_c = xâ‚’ + Ï(x_r - xâ‚’)where0 < Ï â‰¤ 0.5(typicallyÏ=0.5). Iff(x_c) ≤ f(x_r), acceptx_c; otherwise, go to Step 6: Shrink [13]. - Inside Contraction: If

f(x_r) ≥ f(xₙ₊â‚), compute the inside contraction point:x_c = xâ‚’ + Ï(xₙ₊₠- xâ‚’). Iff(x_c) < f(xₙ₊â‚), acceptx_c; otherwise, go to Step 6: Shrink [13].

- This step is reached if

- Step 6: Shrink. If no improvement was found via reflection or contraction, perform a shrink. Replace all points except the best (

xâ‚) withx_i = xâ‚ + σ(x_i - xâ‚)for alli, where0 < σ < 1is the shrink coefficient (typicallyσ=0.5) [13]. Begin the next iteration with the new simplex.

3. Termination

- Common termination criteria include: the function values at all vertices are within a specified tolerance (

TolFun), or the simplex vertices themselves are within a specified distance (TolX) of each other [16].

Nelder-Mead Algorithm Coefficients

The following table summarizes the standard coefficients used in the Nelder-Mead operations [13].

| Operation | Symbol | Standard Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | α (alpha) |

1.0 | Moves the worst point through the centroid of the opposite face. |

| Expansion | γ (gamma) |

2.0 | Pushes further in a promising direction beyond the reflection point. |

| Contraction | Ï (rho) |

0.5 | Pulls the worst point closer to the centroid, either inside or outside. |

| Shrink | σ (sigma) |

0.5 | Reduces the size of the entire simplex towards the best point. |

Nelder-Mead Algorithm Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of decisions and operations in a single iteration of the Nelder-Mead method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key conceptual "reagents" or components essential for conducting an optimization experiment using the Nelder-Mead method.

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Objective Function | The function f(x) to be minimized. It is the central metric defining the quality of a candidate solution. |

| Initial Simplex | The starting set of n+1 points in n-dimensional space. Its quality can significantly impact convergence [13] [16]. |

| Reflection Coefficient (α) | Controls the distance the worst point is reflected through the centroid. A value of 1.0 maintains the simplex volume [13]. |

| Expansion Coefficient (γ) | Allows the algorithm to take larger, accelerating steps down a promising valley [13] [15]. |

| Contraction Coefficient (Ï) | Enables the simplex to contract and narrow in on a potential minimum [13]. |

| Termination Tolerance | A predefined threshold for the standard deviation of function values or simplex size that signals the search is complete [16]. |

| Phaseic acid-d4 | Phaseic acid-d4 Stable Isotope|ABA Metabolite |

| L-Biotin-NH-5MP | L-Biotin-NH-5MP, MF:C15H20N4O3S, MW:336.4 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Sequential Simplex Method Issues

Q1: Why is my optimization process stagnating or cycling between the same solutions? This occurs when the simplex collapses or cannot find an improved vertex. To resolve:

- Recalculate all vertices: Ensure objective function values are current.

- Implement a restart: Shrink the simplex towards the current best vertex and restart the search [11].

- Check for tolerance criteria: The process may have converged; define a tolerance for the minimum simplex size or objective function change to terminate correctly [11].

Q2: How do I handle an experiment where one or more factors have natural lower bounds of zero? The sequential simplex method inherently requires all factors (variables) to be non-negative [17].

- No action needed for non-negativity: If your factors are naturally positive (e.g., concentration, temperature in Kelvin), proceed directly.

- Handling bounded variables: For factors with other lower bounds, apply a simple transformation. For a factor ( x ) with a lower bound ( L ), define a new variable ( x' = x - L ). Now, ( x' \geq 0 ) and the simplex method can proceed [17].

Q3: What should I do if the suggested new experiment is practically infeasible or dangerous? The simplex method is a mathematical guide and suggestions must be tempered with practical knowledge.

- Constrain the move: Do not perform the experiment as calculated. Instead, move the new vertex to the nearest feasible point on the boundary of your experimental region.

- Reflect from the second-worst point: Modify the algorithm to reflect away from the second-worst vertex instead of the worst one to propose an alternative point [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How does the sequential simplex method handle multiple factors without complex statistics?

It uses a geometric approach. For n factors, a simplex with n+1 vertices is constructed in the experimental space. The method then proceeds by moving away from the point with the worst performance through a series of reflections, expansions, and contractions, navigating the factor space based solely on the observed responses without requiring assumptions about the underlying functional form or interactions [11].

Q: What is the main advantage of this method over traditional Design of Experiments (DOE)? Traditional DOE often requires a predefined model (e.g., linear, quadratic) to fit the data and estimate interaction effects. The sequential simplex method is model-free; it does not assume a specific relationship between factors. It efficiently guides the experimenter towards an optimum by reacting to the observed data at the vertices of the simplex, making it highly effective for rapid empirical optimization [11].

Q: When should I not use the sequential simplex method?

- When the objective is to build a predictive model for the entire response surface.

- When the system has a high degree of experimental noise, as this can mislead the simplex moves.

- When you need to understand the precise contribution and interaction of each factor (system understanding vs. empirical optimization) [11].

Q: How do I set up the initial simplex? The initial simplex should be a regular geometric figure. For two factors, it is an equilateral triangle; for three, a tetrahedron. The size of the initial simplex determines the initial step size. A larger simplex coarsely finds the optimum region, while a smaller one performs a finer local search [11].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Sequential Simplex Method

The following workflow details the core operational steps of the sequential simplex method for optimizing a process with n factors.

Core Simplex Operations and Rules

The table below defines the key operations used to manipulate the simplex and the rules for accepting new points.

| Operation | Mathematical Calculation | Acceptance Rule |

|---|---|---|

| Reflection | ( R = C + \alpha(C - W) ), where ( C ) is the centroid (excluding W) and ( \alpha > 0 ) (typically 1) [11]. | Accept if ( R ) is better than ( W ) but not better than ( B ). |

| Expansion | ( E = C + \gamma(R - C) ), where ( \gamma > 1 ) (typically 2) [11]. | If ( R ) is better than ( B ), expand to ( E ). Accept ( E ) if it is better than ( R ); otherwise, accept ( R ). |

| Contraction | ( T = C + \beta(W - C) ) or ( T = C + \beta(R - C) ), where ( 0 < \beta < 1 ) (typically 0.5) [11]. | If ( R ) is worse than ( W ), contract to ( T ). If ( T ) is better than ( W ), accept it. Otherwise, proceed to shrinkage. |

| Shrinkage | All vertices except ( B ) are moved: ( Vi^{new} = B + \delta(Vi - B) ), where ( 0 < \delta < 1 ) (typically 0.5) [11]. | Perform if contraction fails. Effectively restarts the search with a smaller simplex around the current best point. |

Key Simplex Parameters

The following table summarizes typical values for the coefficients used in the operations above.

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | ( \alpha ) | 1.0 | Moves away from the worst-performing region. |

| Expansion | ( \gamma ) | 2.0 | Accelerates progress in a promising direction. |

| Contraction | ( \beta ) | 0.5 | Shrinks the simplex when a reflection fails. |

| Shrinkage | ( \delta ) | 0.5 | Resets the search around the best point to escape a non-productive region. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The sequential simplex method is a mathematical procedure and does not require specific chemical reagents. Its "toolkit" consists of the computational parameters and experimental components required for execution.

| Item / Concept | Function in the Sequential Simplex Method |

|---|---|

| Initial Vertex Matrix | The set of n+1 initial experimental points that define the starting simplex in the n-dimensional factor space [11]. |

| Objective Function | The measurable response (e.g., yield, purity, activity) that the method is designed to maximize or minimize [11]. |

| Reflection Coefficient ((\alpha)) | The multiplicative factor that determines how far the simplex reflects away from the worst vertex. A value of 1.0 is standard [11]. |

| Expansion Coefficient ((\gamma)) | The multiplicative factor that determines how far the simplex expands beyond a successful reflection point to accelerate progress [11]. |

| Contraction Coefficient ((\beta)) | The multiplicative factor that determines how much the simplex contracts towards the centroid when a reflection fails to improve the result [11]. |

| Convergence Tolerance | A pre-defined threshold (for simplex size or objective function change) that signals the optimization is complete [11]. |

| Estriol-d3 | Estriol-d3, MF:C18H24O3, MW:291.4 g/mol |

| Creticoside C | Creticoside C, MF:C26H44O8, MW:484.6 g/mol |

Logical Decision Pathway for a New Experimental Point

The following diagram illustrates the precise logic used to decide whether to accept a reflected point or to trigger an expansion or contraction.

Implementing Sequential Simplex: Step-by-Step Protocols and Real-World Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is an Initial Simplex Design and when should I use it?

An initial simplex design is a structured set of experimental runs that serves as the starting point for optimization algorithms, particularly the sequential simplex method. You should use it when you need to efficiently locate optimal conditions ("sweet spots") in multi-factor experiments, especially during scouting studies in fields like bioprocess development or drug formulation. This approach is particularly valuable when you want to reduce experimental costs while still obtaining well-defined operating boundaries compared to traditional Design of Experiments (DoE) methods [18].

How do I determine the starting point and size for a k-factor experiment?

For a k-factor experiment (with k components or factors), the initial simplex is a geometric figure defined by k+1 points. In mixture experiments, these factors are components whose proportions sum to a constant, usually 1 [19] [20].

- Starting Point Selection: The starting point should be within your experimental region of interest. If you have preliminary knowledge suggesting a promising area, start there. Otherwise, a centroid or evenly distributed point is a reasonable default.

- Size Determination: The size determines how much of the experimental space you initially explore. A larger simplex is more exploratory, while a smaller one provides more refined local search. Your choice should balance between broad exploration and resource constraints.

The total number of design points in a {q, m} simplex-lattice design is given by the formula: (q + m - 1)! / (m!(q-1)!) where 'q' is the number of components and 'm' is the number of equally spaced levels for each component [20].

Table: Initial Simplex Design Parameters for Different Factor Counts

| Number of Factors (k) | Geometric Form | Minimum Number of Initial Runs | Design Notation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Triangle | 3 | {3,2} design with 6 points [20] |

| 3 | Tetrahedron | 4 | {3,3} design with 10 points [20] |

| 4 | 5-cell | 5 | {4,2} design |

What is the step-by-step protocol for creating a simplex lattice design?

Protocol: Creating a Three-Factor Simplex Lattice Design [19]

- Define Factors and Constraints: Identify all mixture components. The total proportion of all components must sum to 1 (or 100%).

- Set Factor Levels: Determine the number of equally spaced levels (m) for each component. The proportions for each component will be xi = 0, 1/m, 2/m, ..., 1.

- Generate Design Points: Create all possible combinations of the factors where their proportions follow the levels from step 2 and sum to 1.

- Build Design Table: Assemble the coordinate settings for each experimental run.

- Randomize Run Order: Minimize the effect of unknown nuisance factors by randomizing the order in which you will execute the experimental runs [21].

Example: A {3,2} Simplex Lattice Design [20] This design for three components (q=3) with two levels (m=2) generates the following 6 design points, though the number of experimental observations can be increased with replication.

Table: Design Matrix for a {3,2} Simplex-Lattice

| X1 (Component 1) | X2 (Component 2) | X3 (Component 3) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

How do I incorporate process variables into a mixture design?

Many real-world experiments involve both mixture components (which sum to a constant) and process factors (which are independent). You can study them together in a combined design [21].

Protocol: Creating a Design with Process Variables [21]

- Create the Mixture Design: First, generate the simplex lattice design for your mixture components (e.g., a {3,2} simplex lattice).

- Add Process Factors: Specify your process variables (e.g., Temperature, Rate of Extrusion) and their levels (e.g., Low: 10, High: 20).

- Cross the Designs: Conduct the entire mixture design (Step 1) under every possible combination of the process factor levels. For example, with 6 mixture blends and 2 process factors at 2 levels each (4 combinations), your total number of experimental runs would be 6 x 4 = 24.

- Analyze with a Combined Model: Fit a model that includes terms for the mixture components, the process factors, and their interactions.

What are the essential reagent solutions for a simplex-related experiment?

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Simplex Optimization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example from Analytical Chemistry [22] |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Stock Solutions | Primary components for creating mixture blends; used as standards for calibration. | 1000 mg L−1 solutions of heavy metals (e.g., Zn(II), Cd(II)) for electrode optimization. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic strength and controls the chemical environment for electrochemical measurements. | 0.1 M acetate buffer solution (pH 4.5). |

| Film Forming Ions | Used to modify and optimize the working electrode surface in electroanalysis. | Bi(III), Sn(II), and Sb(III) ions for forming in-situ film electrodes. |

| Polishing Material | For preparing and maintaining a consistent, clean surface on solid working electrodes. | 0.05 μm Al₂O₃ suspension for polishing glassy carbon electrodes. |

| Real Sample Matrix | Used for method validation and demonstrating applicability to real-world problems. | Tap water prepared in 0.1 M acetate buffer for testing optimized methods. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The sequential simplex algorithm is not converging to an optimum.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Poorly chosen initial simplex size.

- Solution: If the simplex is too large, it may miss fine-grained optimums. If it's too small, progress may be slow. Restart the sequence with a differently sized initial simplex that is appropriate for your expected optimum region [11].

- Cause 2: The initial simplex is located on a flat region of the response surface.

- Solution: If possible, use preliminary knowledge to start in a more responsive region. Alternatively, incorporate curvature into your model if you are using a simplex lattice design for response surface modeling [18].

- Cause 3: The simplex is collapsing or degenerating, losing its volume in the factor space.

- Solution: This is a known issue with the basic sequential simplex method. Implement the modified algorithm by Nelder and Mead, which includes reflection, expansion, contraction, and shrinkage steps to maintain the simplex's geometric properties and prevent collapse [11].

Problem: My analysis shows insignificant model terms or poor model fit.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: The model is overparameterized for the data collected.

- Solution: Use a model selection procedure. Start by including all linear effects and 2-way interactions, then remove terms with high p-values (e.g., above 0.1) or coefficients with an absolute value less than or equal to 1. Recalculate the model after removing insignificant terms [21].

- Cause 2: The design does not include enough points to estimate the desired model.

- Solution: Ensure your initial design has a sufficient number of runs. A {q, m} simplex-lattice has (q + m - 1)! / (m!(q-1)!) points. For a quadratic model, you need at least enough points to estimate the linear and binary interaction terms [20].

- Cause 3: Important process variables were not considered.

- Solution: If your system is influenced by independent factors like temperature or time, use a combined design that crosses your mixture design with a factorial design for the process variables [21].

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Simplex Experiment Initiation Workflow

Mixture Model Interpretation Logic

Troubleshooting Guide: Sequential Simplex Method

This guide addresses common issues you might encounter while using the sequential simplex method to optimize multiple experimental factors.

Q1: The simplex is not moving toward an optimum and seems to be "stagnating" in a suboptimal region. What should I do?

A: This behavior often indicates that the simplex has become stuck on a ridge or is navigating a poorly conditioned response surface.

- Check for Simplex Degeneracy: Ensure that the simplex has not collapsed into a lower-dimensional space. Re-initialize the simplex with a new set of starting points if necessary.

- Verify Movement Logic: Confirm that the reflection, expansion, and contraction operations are correctly implemented. The reflection coefficient (α) is typically 1.0, expansion (γ) is 2.0, and contraction (Ï) is 0.5 [23].

- Consider a Restart: If the simplex has undergone many contractions without significant improvement, halt the current run and restart the procedure from the current best vertex.

Q2: The simplex oscillates between two points instead of converging. How can I resolve this?

A: Oscillation typically occurs when the simplex repeatedly reflects over the same centroid.

- Implement a "Move Rule": Introduce logic to prevent the simplex from returning to a vertex it has just visited. This can break the cycle of reflection between the same points.

- Review Contraction Logic: Ensure that the contraction step is being triggered correctly when a reflected point yields the worst response. A proper contraction should move the simplex away from the oscillatory path [23].

Q3: After a contraction step, the new vertex does not show improvement. What is the next step?

A: Standard contraction might be insufficient if the response surface is complex.

- Perform a "Shrink" or "Total Contraction": If even the contracted vertex does not yield an improvement, a more radical reduction of the simplex size may be necessary. Shrinking involves moving all vertices toward the best-performing vertex, effectively resetting the search on a finer scale around the most promising region [1] [23].

Q4: How do I handle constraints on experimental factors (e.g., pH cannot exceed 14)?

A: The basic simplex method requires modification to handle constrained factors.

- Incorporate Constraint Checks: Before evaluating the response at a new vertex, check if it violates any experimental constraints.

- Apply a Penalty Function: If a proposed vertex violates a constraint, assign it a deliberately poor (e.g., very high for minimization) response value. This will force the simplex to reject this point and trigger a contraction, steering the search back into the feasible region [1].

Q5: The experimental noise is high, leading to unreliable response measurements. How can I make the method more robust?

A: High noise can cause the simplex to move in the wrong direction.

- Replicate Measurements: Instead of a single measurement per vertex, run multiple replicates and use the average response to guide the simplex movements. This reduces the impact of random noise.

- Adjust the Step Size: Use a larger initial simplex size relative to the noise level. This makes the signal from factor changes more detectable compared to the background noise.

Experimental Protocol: Sequential Simplex Optimization

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for conducting an optimization experiment using the sequential simplex method.

1. Objective Definition Define the response variable to be optimized (e.g., yield, purity, activity) and specify whether the goal is to maximize or minimize it. Clearly identify all independent factors (e.g., temperature, concentration, pressure) that will be adjusted.

2. Initial Simplex Construction The initial simplex is a geometric figure with k+1 vertices, where k is the number of factors being optimized.

- Starting Point: Select a feasible starting point (vertex) based on prior knowledge, designated as Vâ‚.

- Factor Scaling: Ensure all factors are on a comparable scale (e.g., by normalizing) to prevent one factor from dominating the movement.

- Generate Remaining Vertices: The other k vertices are generated based on a specified step size for each factor. A common approach is to use the variable-size matrix to construct the initial simplex [23].

3. The Optimization Cycle The following workflow is repeated until a termination criterion is met (e.g., the simplex size becomes smaller than a pre-defined threshold, or the response improvement plateaus).

4. Decision Rules and Movement Logic The response at the reflected vertex (R_reflect) determines the next action, according to the logic in the table below.

| New Vertex | Condition Check | Outcome & Action |

|---|---|---|

| Reflect | Always the first step after ranking and finding the centroid. | Base case for decision-making [23]. |

| Expand | If Rreflect is better than the current best response (Vbest). | The direction is highly favorable. Calculate Vexpand = Vcentroid + γ*(Vreflect - Vcentroid). Evaluate Rexpand. If Rexpand > Rreflect, replace Vworst with Vexpard. Otherwise, use Vreflect [23]. |

| Contract | If Rreflect is worse than or equal to the response at Vsecondworst (or another vertex besides Vworst). | The reflection went too far. Calculate Vcontract = Vcentroid + Ï*(Vworst - Vcentroid). Evaluate Rcontract. If Rcontract > Rworst, replace Vworst with V_contract. Otherwise, proceed to a shrink step [23]. |

| Shrink | If the point from contraction (Vcontract) is not better than Vworst. | The entire simplex must be reduced. Move all vertices (Vi) toward the best vertex (Vbest) according to the rule: Vinew = Vbest + σ*(Viold - Vbest), where σ is the shrink coefficient (typically 0.5) [1] [23]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Role in Optimization |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay Kits | Provides a reliable, standardized method for rapidly measuring the biological response (e.g., enzyme activity, cell viability) at each experimental vertex. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python with SciPy) | Used to implement the simplex algorithm's logic, perform calculations (e.g., centroid), and visualize the path of the simplex across the response surface [24]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Platforms like Ax or other custom solutions can help manage the sequential experiments, track responses, and sometimes directly implement optimization algorithms [24]. |

| Central Composite Design (CCD) | Though a classical method, a CCD can be used in later stages to build a precise local model of the response surface around the optimum found by the simplex, confirming the result [23]. |

| Parameter Tuning Platform (e.g., Ax) | An adaptive experimentation platform that can be used to validate simplex results or handle optimization problems with a very high number of factors where Bayesian optimization might be more efficient [24]. |

| Hypericin (Standard) | Hypericin (Standard), MF:C30H16O8, MW:504.4 g/mol |

| Sibiricine | Sibiricine, CAS:24181-66-6, MF:C20H17NO6, MW:367.4 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How is the sequential simplex method different from other optimization approaches like Bayesian optimization?

A: The sequential simplex is a direct search method that uses simple geometric rules (reflect, expand, contract) and does not require building a statistical model of the entire response surface. It is conceptually straightforward and efficient with a small number of factors. In contrast, Bayesian optimization is a model-based method that uses a probabilistic surrogate model (like a Gaussian Process) and an acquisition function to guide experiments. It is often more efficient in high-dimensional spaces or when experiments are extremely expensive [24] [23].

Q: What are the typical values for the reflection (α), expansion (γ), and contraction (Ï) coefficients?

A: The most standard set of coefficients is α = 1.0, γ = 2.0, and Ï = 0.5. These values have been found to provide a robust balance between aggressive movement toward an optimum (expansion) and cautious refinement (contraction) [23].

Q: When should I terminate a simplex optimization run?

A: Termination is usually based on one or more of the following criteria:

- The difference in response values between the best and worst vertices falls below a pre-set tolerance.

- The simplex has become very small (the distance between vertices is below a threshold).

- A predetermined maximum number of experiments has been conducted.

Q: Can the simplex method handle more than three factors effectively?

A: Yes, the simplex method can be applied to k factors, forming a k+1 vertex polytope in k-dimensional space. However, as the number of factors increases, the number of experiments required can grow, and the method may become less efficient compared to some model-based techniques. It is generally most practical for optimizing up to about five or six factors [1] [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Protein Yield

- Problem: Insufficient production of the target recombinant protein.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Toxic protein to host cells | SDS-PAGE analysis post-induction; monitor cell growth arrest. [25] | Use specialized E. coli strains like C41(DE3) or C43(DE3) designed for toxic proteins. [25] |

| Inefficient transcription/translation | Check plasmid sequence for errors and codon usage. [25] | Use codon-plus strains like Rosetta; optimize induction conditions (IPTG concentration, temperature, timing). [25] |

| Protein degradation | Western blot showing smeared or disappearing bands. [25] | Use protease-deficient host strains (e.g., BL21); lower induction temperature; add protease inhibitors during lysis. [25] |

| Insufficient culture aeration/nutrient depletion | Monitor OD600 and growth curve. [25] | Increase shaking speed; reduce culture volume; scale up culture volume; use rich media like Terrific Broth. [25] |

Poor or Inefficient Biotinylation

- Problem: The target protein is expressed but is not biotinylated, or biotinylation efficiency is low.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| BirA biotin ligase activity or concentration is limiting | Use streptavidin-AP Western blot to detect biotinylation. [26] | Co-express BirA ligase with your target protein; ensure adequate biotin and ATP in the culture medium. [27] |

| Inaccessible biotin acceptor peptide (AviTag) | Confirm protein sequence and AviTag placement. | Ensure the AviTag is located in a flexible, solvent-accessible region of your protein, often at the N- or C-terminus. |

| Sub-optimal in vivo reaction conditions | Measure biotinylation efficiency in vitro. [26] | Supplement culture media with excess biotin (e.g., 50 μM); induce BirA expression before target protein induction; use a mutant BirA (R118G) with promiscuous activity (use with caution). [26] |

Low Protein Solubility

- Problem: The target protein is produced but forms inclusion bodies (insoluble aggregates).

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation during high-level expression | Solubility analysis via centrifugation and SDS-PAGE of soluble vs. insoluble fractions. [25] | Lower induction temperature (e.g., 16-25°C); reduce inducer (IPTG) concentration; use fusion tags like MBP or SUMO to enhance solubility. [25] |

| Lack of proper folding partners | Compare solubility in different E. coli strains. [25] | Use strains engineered for disulfide bond formation (e.g., Shuffle T7) or co-express molecular chaperones. [25] |

| Incorrect or harsh lysis conditions | Visualize protein localization. [25] | Use gentle lysis methods; screen different lysis buffers with varying salt, pH, and detergent concentrations. [25] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most suitable E. coli strain for producing a biotinylated protein that requires disulfide bonds for activity? The Shuffle strain series is an excellent choice. These strains are engineered to promote the correct formation of disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm by expressing disulfide bond isomerase (DsbC) and are deficient in proteases, enhancing the stability of your recombinant protein. [25]

Q2: My biotinylated protein is expressed in inclusion bodies. Should I attempt to refold it or change my strategy? You can do either, but a strategy change is often more efficient. First, attempt to refold the protein from inclusion bodies using denaturing agents like urea or guanidine hydrochloride, followed by gradual dialysis into a native buffer. Alternatively, optimize expression for solubility by switching to a lower induction temperature (18-25°C), using a solubility-enhancing fusion tag (like MBP or SUMO), or trying a different E. coli host strain. [25]

Q3: How can I confirm that my protein is successfully biotinylated? The most common and reliable method is a Western blot. [26] After separating your protein samples via SDS-PAGE, transfer them to a membrane and probe with streptavidin conjugated to a detection molecule (e.g., horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase). Streptavidin binds with extremely high affinity to biotin, allowing you to visualize only the biotinylated proteins. [26]

Q4: Can I perform high-throughput screening for optimizing biotinylated protein production? Yes, high-throughput screening (HTS) is feasible and recommended for multi-factor optimization. You can perform cloning, expression, and initial screening in 96-well or 384-well microplates. [28] For the expression step, technologies like the Vesicle Nucleating peptide (VNp) can be used to export functional proteins into the culture medium in a multi-well format, simplifying purification and analysis. [28] This setup is ideal for testing many different conditions in parallel.

Q5: What is the role of the sequential simplex method in this optimization process? The sequential simplex method is a powerful statistical optimization tool for experiments with multiple variables. [29] In the context of optimizing protein production, you can use it to efficiently navigate factors like temperature, inducer concentration, media composition, and biotin concentration. [29] Unlike testing one factor at a time, the simplex method moves towards an optimum based on the results of previous experiments, often requiring fewer total experiments to find the ideal condition combination. [29]

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for the experiments described in this case study.

| Item | Function/Application in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| E. coli Strains (BL21(DE3), Shuffle, Rosetta) | Engineered host organisms for recombinant protein expression, offering benefits like protease deficiency, enhanced disulfide bond formation, or supplementation of rare tRNAs. [25] |

| pET Expression Vectors | Plasmid vectors containing a strong T7 promoter, used to clone the gene of interest and drive high-level protein expression in E. coli. [25] |

| BirA Biotin Ligase | The enzyme that catalyzes the attachment of biotin to a specific lysine residue within the AviTag sequence on the target protein. [26] [27] |

| Biotin | The essential co-factor and substrate for the BirA enzyme. Must be supplemented in the culture medium for in vivo biotinylation. [26] |

| Ni-NTA Affinity Resin | For purifying recombinant proteins that have been fused with a hexahistidine (6xHis) tag. The resin binds the His-tag with high specificity. [25] |

| Strep-Tactin Magnetic Beads | Beads that bind with high affinity to biotin. Used to rapidly and efficiently purify biotinylated proteins, ideal for automated or high-throughput workflows. [27] |

| VNp (Vesicle Nucleating Peptide) Tag | A peptide tag that, when fused to a recombinant protein, promotes its export from E. coli into extracellular vesicles, simplifying purification and enhancing stability. [28] |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Workflow for Standard Production and Optimization

High-Throughput Screening Workflow

The sequential simplex method is a powerful, practical multivariate optimization technique used in analytical method development to efficiently find the optimal conditions for a process by considering multiple variables simultaneously. Unlike univariate optimization, which changes one factor at a time, the simplex method evaluates all factors concurrently, allowing researchers to identify interactions between variables and reach optimum conditions with fewer experiments [12].

In this case study, we demonstrate how the sequential simplex method was successfully employed to optimize chromatographic and spectroscopic methods for pharmaceutical analysis. This approach is particularly valuable in analytical chemistry for optimizing instrumental parameters, developing robust analytical procedures, and ensuring good analytical characteristics such as higher sensitivity and accuracy [12]. The method works by displacing a geometric figure with k + 1 vertexes (where k equals the number of variables) through an experimental field toward an optimal region, with movements including reflection, expansion, and contraction to navigate the response surface efficiently [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Sequential Simplex Optimization: A Step-by-Step Protocol

The following workflow illustrates the core decision-making process of the sequential simplex method:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Simplex Optimization

Materials: Standard analytical reagents, chromatographic reference standards, appropriate instrumentation (HPLC, GC, or spectrophotometer), data collection software.

Procedure:

- Define Variables and Responses: Select critical factors to optimize (e.g., mobile phase composition, pH, temperature, flow rate) and measurable responses (e.g., resolution, peak symmetry, sensitivity) [12].

- Establish Initial Simplex: Create an initial geometric figure with k+1 vertexes, where k is the number of variables being optimized. For two variables, this forms a triangle; for three variables, a tetrahedron [12].

- Run Experiments: Conduct experiments at each vertex of the initial simplex and measure the responses.

- Calculate New Vertex:

- Reflection: Calculate the reflection point (R) of the worst vertex (W) through the centroid of the remaining vertexes using the formula: R = P + α(P - W), where P is the centroid and α is the reflection coefficient (typically 1.0) [12].

- Expansion: If the reflection point yields better results than the current best vertex, calculate an expansion point (E) using: E = P + γ(P - W), where γ is the expansion coefficient (typically >1.0) [12].

- Contraction: If the reflection point is worse than the second-worst vertex, calculate a contraction point (C) using: C = P + β(P - W), where β is the contraction coefficient (typically 0.5) [12].

- Iterate: Replace the worst vertex with the new vertex and repeat the process until the simplex converges on the optimum conditions [12].

- Verify: Confirm optimal conditions with replicate experiments and validate the method according to regulatory guidelines [30].

Case Study: Fast-Dissolving Tablet Formulation Development

In a practical application from pharmaceutical research, the sequential simplex method was employed to develop fast-dissolving tablets of clozapine [31]. Researchers selected microcrystalline cellulose and polyplasdone as the two critical formulation variables and evaluated responses including disintegration time, hardness, and friability. The success of formulations was evaluated using a total response equation generated in accordance with the priority of the response parameters [31]. Based on response rankings, the simplex sequence continued through reflection, expansion, or contraction operations until a desirable disintegration time of less than 10 seconds with adequate hardness was achieved [31].

Chromatographic Method Development Compliance with USP <621>

When developing chromatographic methods for pharmaceutical applications, compliance with regulatory standards is essential. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) General Chapter <621> Chromatography provides mandatory requirements for chromatographic analysis in regulated Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) laboratories [30]. Key considerations include:

System Suitability Testing (SST) Requirements:

- System Sensitivity: Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio measurements are required when determining impurities, with the limit of quantification (LOQ) based on a S/N of 10 [30].

- Peak Symmetry: A general requirement for peak symmetry between 0.8-1.8 has been added to the updated USP <621> chapter [32].

- Resolution Calculation: The definition and calculation of resolution is now based on peak width at half height rather than at the baseline [32].

Allowed Adjustments: The harmonized USP <621> standard allows certain adjustments to chromatographic systems without requiring full revalidation, including changes to injection volume, mobile phase composition, pH, and concentration of salts in buffers, provided system suitability requirements are met [32] [30].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Chromatography Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Chromatography Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Steps | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| No peaks or only solvent peak [33] | - Column installed incorrectly- Split ratio too high (capillary GC)- Large leak (septum, column connections, detector)- Detector settings incorrect- Sample issues | 1. Verify column installation and connections2. Check split ratio settings3. Perform leak check4. Verify detector configuration5. Test with known standard mixture | - Follow manufacturer's column installation guidelines- Regularly change septa and check fittings- Use retention gaps where appropriate |

| Peak fronting [33] | - Column overload- Inappropriate injector liner- Incorrect injection technique | 1. Reduce injection volume or sample concentration2. Change inlet liner3. Verify injection technique and parameters | - Ensure sample concentration is within linear range- Select proper liner for application- Follow established injection protocols |

| Peak tailing [33] | - Active sites in column or system- Column contamination- Incorrect mobile phase pH- Sample interaction with system components | 1. Condition column properly2. Use peak tailing reagents in mobile phase3. Adjust mobile phase pH4. Replace column if severely degraded | - Use appropriate guard columns- Filter samples and mobile phases- Regular column maintenance and cleaning |

| Poor resolution [32] [30] | - Incorrect mobile phase composition- Column deterioration- Temperature inappropriate- Flow rate too high | 1. Optimize mobile phase composition2. Evaluate column performance with test mix3. Adjust temperature parameters4. Reduce flow rate | - Monitor system suitability parameters regularly- Establish column performance tracking- Follow manufacturer's recommended conditions |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When should I use sequential simplex optimization instead of other optimization methods? A: Sequential simplex is particularly valuable when you need to optimize multiple factors simultaneously without requiring complex mathematical-statistical expertise [12]. It's especially useful for optimizing automated analytical systems and when dealing with systems where variable interactions are significant. The method provides a practical approach that can be easily implemented and understood by researchers with varying levels of statistical background.

Q: What are the most critical changes in the updated USP <621> chromatography chapter? A: The most significant changes include: (1) New requirements for system sensitivity (signal-to-noise ratio) with LOQ based on S/N of 10; (2) General peak symmetry requirements between 0.8-1.8; (3) Resolution calculation based on peak width at half height; (4) Expanded allowed adjustments for gradient elution methods; and (5) Replacement of "disregard limit" with "reporting thresholds" [32] [30]. These changes became fully effective May 1, 2025.

Q: Why do I see only solvent peaks after installing a new GC column? A: This common issue can have multiple causes [33]. First, verify proper column installation and check for leaks at injector septa and column connections. Second, confirm your split ratio isn't set too high for capillary columns. Third, check detector settings and ensure they're configured correctly. Finally, test with a known standard mixture to verify system performance. Always condition new columns according to manufacturer specifications before use.

Q: How do I calculate resolution according to the updated USP <621> guidelines? A: The updated USP <621> chapter has modified the resolution calculation to be based on peak width at half height rather than at the baseline [32]. This provides a more consistent measurement, particularly for peaks of different shapes or those with tailing. Ensure your chromatography data system software is updated to use the current calculation method to maintain compliance.

Q: Can I adjust my chromatographic method parameters without revalidation? A: Yes, within specific limits outlined in USP <621> [32] [30]. The harmonized standard allows adjustments including mobile phase composition, pH, concentration of salts in buffers, application volume (TLC), and injection volume, provided system suitability requirements are met. For gradient elution methods, adjustments to particle size and injection volume are now permitted. However, any adjustments must be documented and verified to ensure they don't compromise method validity.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Analytical Method Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystalline Cellulose [31] | Pharmaceutical excipient used in formulation development | Used as a variable in simplex optimization of fast-dissolving tablets; provides bulk and compression properties |

| Polyplasdone [31] | Superdisintegrant in tablet formulations | Critical factor in optimizing disintegration time in pharmaceutical formulations |

| FAMEs Standard [33] | Fatty Acid Methyl Esters mixture for GC calibration and column testing | Used for testing GC system performance; particularly important after column installation or maintenance |

| Chromatographic Reference Standards [30] | Qualified materials for system suitability testing | Essential for verifying chromatographic system performance and compliance with USP <621> requirements |

| Appropriate Buffer Systems [32] [30] | Mobile phase components for pH control | Critical for maintaining consistent retention times and peak shapes; pH adjustments allowed under USP <621> within limits |

Method Validation & Regulatory Compliance

The following workflow illustrates the relationship between optimization, method development, and regulatory compliance:

Implementing Updated USP <621> Requirements

The updated USP <621> chromatography chapter introduces specific requirements that laboratories must implement for regulatory compliance [32] [30]:

System Sensitivity Requirements:

- Signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio measurements are required when determining impurities at or near limits of quantification

- The Limit of Quantification (LOQ) is based on a S/N of 10 and is related to the monograph specifications

- S/N ratio should be measured using pharmacopoeial reference standards, not samples

- This requirement applies specifically to impurity determination, not main peak analysis

Peak Symmetry Specifications:

- General requirement for peak symmetry between 0.8-1.8

- Must be measured during system suitability testing

- Provides indication of column performance and appropriate mobile phase conditions

Documentation and Adjustment Protocols:

- Laboratories must document all adjustments made to chromatographic conditions

- Allowed adjustments include changes to injection volume, mobile phase composition, pH, and concentration of salts in buffers

- Changes to gradient elution methods are now permitted without full revalidation, provided system suitability requirements are met

The sequential simplex method provides an efficient, practical approach for optimizing multiple experimental factors in analytical method development. By systematically navigating the experimental response surface, researchers can identify optimal conditions for chromatographic and spectroscopic methods while considering variable interactions. When combined with understanding of regulatory requirements such as USP <621>, this optimization strategy supports the development of robust, reliable analytical methods suitable for pharmaceutical applications and other regulated environments. The troubleshooting guides and FAQs presented in this technical support center address common practical challenges encountered during method development and implementation, providing researchers with actionable solutions to maintain analytical system performance and regulatory compliance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the default values for reflection, expansion, and contraction coefficients in the simplex method, and when should I deviate from them? The widely accepted default coefficients for the sequential simplex method are a reflection coefficient of 1.0, a contraction coefficient of 0.5, and an expansion coefficient between 2.0 and 2.5 [34]. These values are nearly optimal for many test functions. You should consider using a larger expansion coefficient (e.g., 2.2–2.5) when you need the simplex to search a larger area of the response surface, as this can resemble the effect of repetitive expansion and potentially increase the speed of optimization [34]. However, unlimited repetitive expansion can be less successful for complex functions and must be managed with constraints on degeneracy [34].

2. My simplex optimization keeps failing to converge. What are the primary convergence criteria, and how can I adjust them? Convergence is typically checked by comparing the function value between the points of the current simplex and the corresponding points from the previous iteration [35]. The algorithm often uses two main criteria: an absolute difference threshold and a relative difference threshold [35]. Convergence is achieved when the change in the objective function value between iterations falls below one of these thresholds. If your simplex is failing to converge, you can adjust the convergence checker by specifying custom absolute and relative threshold values. Tighter thresholds will require more iterations but may yield a more precise optimum, whereas looser thresholds may stop prematurely [35].

3. What is simplex degeneracy, and how can I prevent it from causing false convergence? Degeneracy occurs when the simplex vertices become computationally dependent, often due to repeated failed contractions, which can prevent the simplex from progressing toward the true optimum [34]. A key sign is the simplex failing to move or converging to a non-optimal point. To prevent this, implement a constraint on the degeneracy of the simplex, typically by monitoring and controlling the angles between its edges [34]. Furthermore, combining this constraint with a translation of the repeated failed contracted simplex has proven to be a more reliable method for finding the optimum region [34].

4. How should I handle experimental points that fall outside my predefined variable boundaries? A robust approach is to correct the vertex located outside the boundary back to the boundary itself [34]. Simply assigning an unfavorable response value to points outside the boundaries, as done in the basic and modified simplex methods, can be inefficient, especially when the optimum is near a boundary. The correction method improves both the speed and the reliability of locating the optimum [34].