Strategic Basis Set Selection: Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Quantum Chemical Calculations

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing basis sets for quantum chemical calculations.

Strategic Basis Set Selection: Balancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Quantum Chemical Calculations

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing basis sets for quantum chemical calculations. It covers foundational concepts, from minimal Slater-type orbitals to extended correlation-consistent sets, and details methodological strategies for specific applications like drug design and materials science. The guide addresses common challenges such as basis set superposition error (BSSE) and offers advanced optimization techniques, including the promising vDZP basis set and density-based corrections for quantum computing. Finally, it establishes a framework for validating basis set performance against gold-standard benchmarks and high-accuracy datasets, empowering scientists to make informed decisions that maximize computational efficiency without sacrificing chemical accuracy.

Understanding Basis Sets: From Core Concepts to Complete Basis Set Limits

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a basis set in quantum chemistry? A basis set is a set of mathematical functions, called basis functions, which are combined in linear combinations to represent the electronic wave function of a molecule or atom in a quantum mechanical calculation [1] [2]. Since the exact wave function is typically unknown and cannot be calculated directly, the wave function is approximated by a linear combination of these basis functions, with the coefficients determined by solving the Schrödinger equation [3] [2].

2. What are the main types of basis functions used? The two primary types are Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs) and Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs). STOs more accurately describe electron density, particularly near the nucleus, but are computationally expensive [1] [4]. GTOs are computationally more efficient and are the modern standard because the product of two GTOs can be written as a linear combination of other GTOs, enabling huge computational savings [1] [4].

3. What does the "minimal" in a minimal basis set mean? A minimal basis set contains the minimum number of basis functions required to describe the electrons in an atom, using one basis function for each atomic orbital in the ground state configuration [1] [4]. A common example is the STO-3G basis set, which approximates each Slater-type orbital with 3 Gaussian-type orbitals [1].

4. Why would I use a polarized or diffuse basis set?

- Polarization functions (e.g., denoted by

*in Pople basis sets) add higher angular momentum functions (like d-functions on carbon) to the basis. This allows the electron density to distort from its atomic shape, which is crucial for accurately describing chemical bonding [1] [5]. - Diffuse functions (e.g., denoted by

+in Pople basis sets) are Gaussian functions with very small exponents, giving them a large spatial extent. They are essential for accurately modeling anions, excited states, dipole moments, and long-range interactions like van der Waals forces [1] [4] [5].

5. What is Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)? BSSE is an error that arises in calculations of molecular complexes or interaction energies. It occurs when the basis functions of one molecule artificially improve the description of the electron density of a neighboring molecule. This leads to an overestimation of the interaction energy [4]. BSSE can be mitigated by using larger basis sets or applying a counterpoise correction [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Energy Calculations

Problem: Your calculated energies (e.g., reaction energies, binding energies) are inconsistent with benchmark data or experimental results.

Diagnosis: This is often caused by Basis Set Incompleteness Error (BSIE), where the basis set is too small to represent the electron correlation energy adequately [6].

Solution:

- Systematically increase the basis set size. Move from double-zeta to triple-zeta or larger [6].

- Use correlation-consistent basis sets. For high-accuracy energy calculations, employ a hierarchy like Dunning's cc-pVXZ sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ) and extrapolate to the complete basis set (CBS) limit [1] [4].

- Consider modern, efficient basis sets. For Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, the

vDZPbasis set has been shown to provide accuracy close to larger triple-zeta basis sets at a much lower computational cost, making it an excellent compromise [6].

Issue 2: Poor Description of Anions or Weak Interactions

Problem: Calculations for anions fail to converge, or intermolecular interaction energies (e.g., hydrogen bonding) are significantly underestimated.

Diagnosis: The basis set lacks diffuse functions, which are necessary to describe the loosely bound electrons that reside far from the nucleus [1] [5].

Solution:

- Add diffuse functions to your basis set. For example, switch from

6-31Gto6-31+Gfor first-row atoms, or to6-31++Gto also include diffuse functions on hydrogen atoms [1]. - Use basis sets designed for these properties. The "aug-" (augmented) series, such as

aug-cc-pVDZ, come with built-in diffuse functions [7].

Issue 3: Optimized Geometries Do Not Match Experimental Structures

Problem: The bond lengths and angles from your geometry optimization are systematically too long or too short.

Diagnosis: The basis set lacks the flexibility to properly describe the polarization of electron density around atoms as bonds are formed. This is typically due to missing polarization functions [4].

Solution:

- Always use a polarized basis set for geometry optimizations. A minimal basis set like STO-3G is insufficient. Start with at least a polarized double-zeta basis set, such as

6-31G*orcc-pVDZ[1] [4]. - Ensure polarization on all atoms. The

6-31Gbasis set adds polarization functions to hydrogen atoms, which can be critical for accurate geometries of molecules like water or ammonia [1].

Basis Set Selection and Performance

Table 1: Hierarchy of Common Gaussian Basis Sets

| Basis Set Type | Key Features | Common Examples | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | One basis function per atomic orbital; fast but inaccurate. | STO-3G [1] | Very preliminary calculations on large systems. |

| Split-Valence | Multiple functions for valence electrons; good cost/accuracy balance. | 3-21G, 6-31G [1] [7] | Routine calculations on medium-sized molecules. |

| Polarized | Adds higher angular momentum functions (d, f). | 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ [1] [4] | Standard for molecular geometries and vibrations. |

| Diffuse | Adds spatially extended functions for "electron tails". | 6-31+G*, aug-cc-pVDZ [1] [7] | Anions, excited states, weak interactions. |

| Correlation-Consistent | Systematically designed to converge to the CBS limit. | cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5...) [1] [7] | High-accuracy energy calculations with extrapolation. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Double-Zeta Basis Sets in DFT Calculations [6]

| Basis Set | Overall WTMAD2 Error (kcal/mol) | Relative Speed | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| vDZP | 7.13 - 9.56 | Fastest | Modern, efficient; minimizes BSIE/BSSE. |

| 6-31G(d) | ~Higher than vDZP | Fast | Classic polarized double-zeta. |

| def2-SVP | ~Higher than vDZP | Fast | Popular general-purpose double-zeta. |

| (aug)-def2-QZVP | 3.73 - 8.42 | Slowest | Large reference basis; near the CBS limit. |

Experimental Protocol: Basis Set Optimization for Quantum Phase Estimation

Objective: To reduce the computational cost of Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) by optimizing the orbital basis to lower the Hamiltonian 1-norm (λ) without compromising energy accuracy [8].

Background: The cost of QPE scales with λ, which typically grows with the number of orbitals. This protocol uses the Frozen Natural Orbital (FNO) approach to truncate the virtual space from a large initial basis set, effectively capturing dynamic correlation with fewer orbitals [8].

Methodology:

- Initial Calculation: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock or DFT calculation on the target molecule using a large, dense basis set (e.g.,

cc-pVQZ). - Generate MP2 Natural Orbitals: Perform a second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) calculation. From this, derive the natural orbitals and their occupation numbers.

- Truncate Virtual Space: Analyze the occupation numbers of the virtual natural orbitals. Discard orbitals with occupation numbers below a defined threshold (e.g., below 0.002).

- Form Active Space: The retained occupied and virtual orbitals form a smaller, more efficient active space for the subsequent quantum computation.

- Run QPE: Use the Hamiltonian constructed from this FNO active space to run the QPE algorithm.

Conclusion from Recent Research: Employing FNOs derived from a large basis set can lead to a reduction of up to 80% in the 1-norm λ and a 55% reduction in the number of orbitals, compared to using the full, untruncated basis set. This strategy is significantly more effective than directly optimizing the exponents of a small basis set [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Basis Sets for Quantum Chemical Research

| Item / Basis Set | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| STO-3G | A minimal basis set for initial geometry optimizations or qualitative studies on very large systems [4]. |

| 6-31G / 6-31G* | A family of split-valence (and polarized) basis sets; a classic, widely-used workhorse for routine molecular calculations [1] [7]. |

| cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5) | Correlation-consistent basis sets designed for systematic convergence to the complete basis set limit in post-Hartree-Fock calculations [1] [4]. |

| def2-SVP / def2-TZVP | Popular split-valence and triple-zeta basis sets from the Ahlrichs group, often used in DFT calculations [7]. |

| vDZP | A modern double-zeta polarized basis set optimized for use with density functionals, offering near triple-zeta accuracy at a lower cost [6]. |

| Augmented Functions (+, aug-) | "Reagents" to add to standard basis sets to describe anions, excited states, and long-range interactions accurately [1] [7]. |

| Acremine I | Acremine I, MF:C12H16O5, MW:240.25 g/mol |

| Actiketal | Actiketal, MF:C15H15NO5, MW:289.28 g/mol |

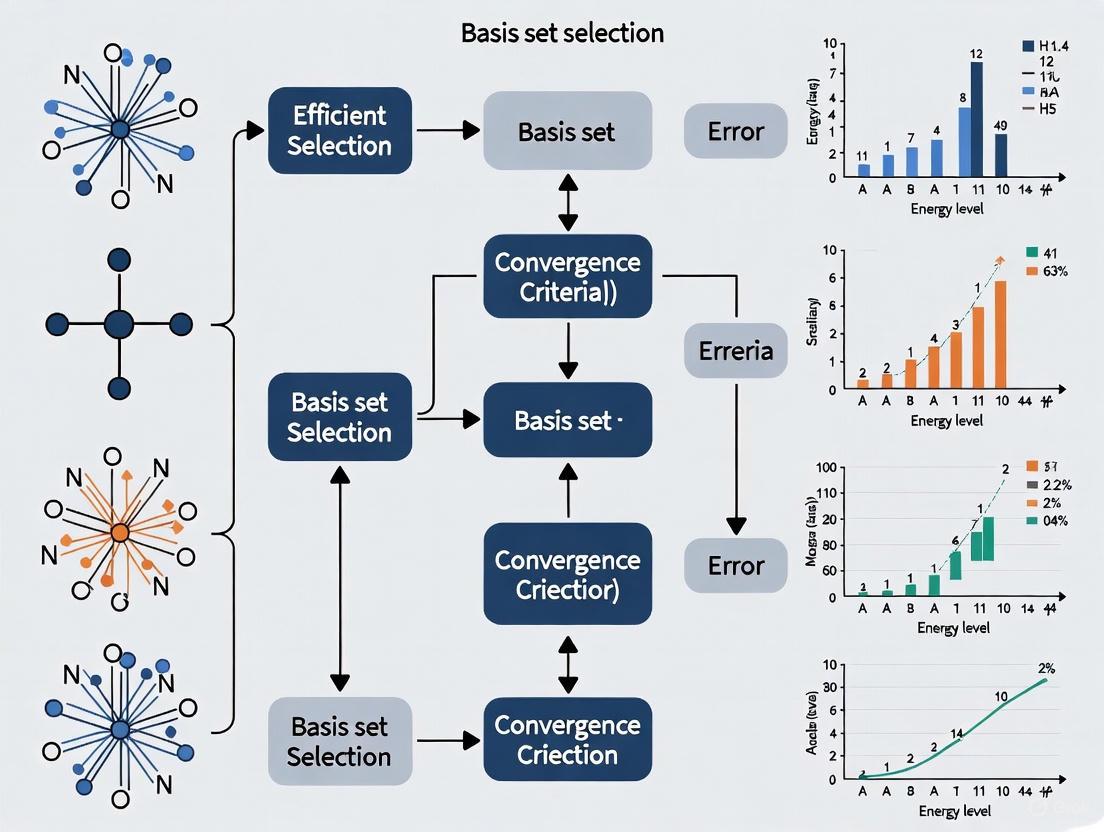

Basis Set Selection Workflow

Core Concepts and Quantitative Comparison

Fundamental Definitions

In quantum chemical calculations, a basis set is a set of functions, called basis functions, used to represent the electronic wave function. These functions are combined linearly to construct molecular orbitals, turning complex partial differential equations into algebraic equations that can be solved computationally [9] [1]. The two primary types of atomic orbitals used are Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs) and Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs).

Direct Comparison: STOs vs. GTOs

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and trade-offs between Slater-Type and Gaussian-Type Orbitals.

| Feature | Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs) | Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs) |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | (\chi{STO} = Nr^{n-1}e^{-\zeta r}Y{lm}(\theta,\phi)) [10] | (\chi{GTO} = Nr^{l}e^{-\alpha r^2}Y{lm}(\theta,\phi)) [10] |

| Radial Decay | Exponential ((e^{-r})) [10] | Gaussian ((e^{-r^2})) [10] |

| Cusp Condition | Satisfied (accurate electron behavior near nucleus) [10] | Not satisfied (poor core electron representation) [10] |

| Long-Range Behavior | Accurate (matches actual atomic orbitals) [10] | Less accurate (decays too rapidly) [10] |

| Computational Efficiency | Low (integral calculation is difficult) [1] | High (product of two GTOs is another GTO) [1] |

| Primary Use Case | Physically motivated, high-accuracy benchmarks [1] | Standard for most practical computations [1] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

How do I choose between a minimal and a polarized basis set for my drug molecule calculation?

Answer: The choice depends on the property you wish to calculate and the required accuracy level.

- Minimal Basis Sets (e.g., STO-3G): These are the smallest possible sets, using one basis function for each orbital in the atom [1]. They are computationally cheap but provide rough results that are generally insufficient for research-quality publications, especially for analyzing electronic properties or subtle bonding interactions [1].

- Polarized Basis Sets (e.g., 6-31G*): These add functions with higher angular momentum (e.g., p-functions on hydrogen, d-functions on carbon) to provide flexibility for the electron density to polarize in response to the molecular environment [1]. This is crucial for accurately modeling chemical bonding, molecular properties, and reactivity in drug development.

Recommendation: For most research applications in pharmaceutical development, start with at least a split-valence polarized basis set like 6-31G*.

My calculations on an anionic molecule are unstable or inaccurate. What basis set feature is likely missing?

Answer: This issue commonly arises from the lack of diffuse functions. Diffuse functions are Gaussian functions with small exponents, which extend far from the nucleus and provide flexibility to the "tail" of the electron cloud [1]. They are essential for correctly describing anions, molecules with large dipole moments, and intra- or inter-molecular bonding.

Solution: Add diffuse functions to your basis set. In the Pople basis set notation, this is indicated by a "+" symbol. For example:

- Use 6-31+G* for diffuse functions on heavy atoms (like C, N, O) and polarization.

- Use 6-31++G* for diffuse functions on both heavy atoms and hydrogen [1].

For high-accuracy energy calculations, how can I systematically improve my results toward the exact value?

Answer: To systematically converge results to the complete basis set (CBS) limit, especially for post-Hartree-Fock (correlated) methods, use correlation-consistent basis sets developed by Dunning and coworkers [1].

Protocol:

- Select a hierarchy of basis sets, such as cc-pVDZ → cc-pVTZ → cc-pVQZ, where D (double-ζ), T (triple-ζ), and Q (quadruple-ζ) indicate increasing levels of completeness [1].

- Perform your calculation at each level of the hierarchy.

- Use empirical extrapolation techniques on the results (e.g., energies) to estimate the value at the complete basis set limit. This provides a controlled and systematic path to high accuracy.

The "cusp condition" is often cited as a weakness of GTOs. What is its practical impact on my calculation?

Answer: The cusp condition refers to the correct, discontinuous behavior of the wavefunction's derivative precisely at the atomic nucleus [10]. STOs satisfy this condition, accurately representing electron density near the nucleus. GTOs, however, fail to meet this condition, leading to a less accurate description of core electrons [10].

Practical Impact: For properties that depend heavily on electron density very close to the nucleus (e.g., hyperfine coupling constants in magnetic resonance spectroscopy), this can introduce inaccuracies. However, for many chemical properties (like reaction energies, conformational energies, and frontier orbital energies), the effect is less critical. The computational advantage of GTOs often outweighs this drawback, which is mitigated by using multiple contracted Gaussian functions to approximate a single STO [1].

Are plane waves a type of basis set, and when would I use them instead of atomic orbitals?

Answer: Yes, plane waves are another type of basis set frequently used in computational chemistry, particularly in solid-state and materials physics calculations [11] [1]. While Gaussian-type atomic orbitals are the standard for molecular quantum chemistry, plane waves offer advantages for periodic systems.

Selection Guideline:

- Use Atomic Orbitals (GTOs): For isolated molecules, cluster models, and most molecular properties in pharmaceutical research [11] [1].

- Use Plane Waves: For calculations involving infinite crystalline solids, surfaces, and materials with periodic boundary conditions [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Basis Set Types

The table below catalogs key basis set types used in computational research, providing a quick reference for selection.

| Basis Set Type | Key Example(s) | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal | STO-3G, STO-4G [1] | Provides a low-cost, low-accuracy starting point for very large systems. |

| Split-Valence | 3-21G, 6-31G, 6-311G [1] | Offers improved accuracy over minimal sets by describing valence electrons with multiple functions; good for geometry optimizations. |

| Polarized | 6-31G, 6-31G(d,p) [1] | Adds angular momentum flexibility for bonding accuracy; essential for property prediction. |

| Diffuse | 6-31+G, 6-31++G [1] | Extends the electron density "tail" for anions, excited states, and weak interactions. |

| Correlation-Consistent | cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ [1] | Enables systematic convergence to the CBS limit for high-accuracy energy calculations. |

| Enacyloxin IIa | Enacyloxin IIa, MF:C33H45Cl2NO11, MW:702.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cypemycin | Cypemycin, MF:C99H154N24O24S, MW:2096.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow for Efficient Basis Set Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate basis set, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals working on molecular systems.

In quantum chemical calculations, a basis set is a collection of mathematical functions that serves as the fundamental building blocks for representing molecular orbitals and electron densities [1]. The careful selection of an appropriate basis set represents one of the most critical decisions in computational chemistry, directly determining the accuracy, reliability, and computational cost of simulations aimed at predicting molecular properties, reaction mechanisms, and spectroscopic behavior [5]. This technical resource center provides a comprehensive framework for researchers navigating the complex hierarchy of basis sets, from minimal to extended sets, with particular emphasis on efficient selection strategies for drug discovery and materials research.

The fundamental challenge in basis set development stems from the trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy. While larger basis sets typically provide more precise results, they demand substantially greater computational resources—a crucial consideration when studying large pharmaceutical compounds or conducting high-throughput virtual screening [6]. Understanding this balance is essential for designing computationally feasible yet scientifically rigorous research protocols.

Basis Set Fundamentals and Theoretical Background

Mathematical Foundation

Basis sets transform the partial differential equations of quantum mechanical models into algebraic equations suitable for computational implementation [1]. In modern computational chemistry, electronic wavefunctions are represented as linear combinations of basis functions:

[ |\psii\rangle \approx \sum{\mu} c_{\mu i} |\mu\rangle ]

where (|\mu\rangle) represents the basis functions and (c_{\mu i}) are the expansion coefficients determined through self-consistent field procedures [1]. This mathematical formalism allows researchers to approximate the complex behavior of electrons in molecules and materials.

Types of Basis Functions

The quantum chemistry community primarily employs three distinct types of basis functions, each with unique mathematical properties and computational advantages:

Slater-type orbitals (STOs): These exponential functions, represented as (N \cdot e^{-\alpha r}), closely resemble the exact solutions for hydrogen-like atoms and satisfy Kato's cusp condition at atomic nuclei [1] [5]. Despite their mathematical accuracy, STOs present significant computational challenges for integral evaluation in molecular systems.

Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs): Following Frank Boys' pioneering work, these functions of the form (N \cdot e^{-\alpha r^2}) have become the standard in computational chemistry [1] [5]. The product of two GTOs can be expressed as another Gaussian, enabling efficient computation of molecular integrals through closed-form solutions.

Contractured Gaussians: To balance accuracy and efficiency, most modern basis sets employ fixed linear combinations of primitive Gaussian functions designed to approximate Slater-type orbitals while maintaining computational tractability [6].

Table: Comparison of Basis Function Types

| Function Type | Mathematical Form | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slater-type Orbitals (STOs) | (N \cdot e^{-\alpha r}) | Accurate representation, satisfies cusp condition | Computationally expensive integrals |

| Gaussian-type Orbitals (GTOs) | (N \cdot e^{-\alpha r^2}) | Efficient integral computation | Less accurate per function |

| Contracted Gaussians | (\sumi di \cdot N \cdot e^{-\alpha_i r^2}) | Balance of accuracy and efficiency | Limited flexibility in core regions |

The Basis Set Hierarchy: From Minimal to Extended Sets

Minimal Basis Sets

Minimal basis sets represent the simplest starting point for quantum chemical calculations, containing exactly one basis function for each atomic orbital in a Hartree-Fock calculation on the constituent atoms [1] [12]. For atoms in the second period of the periodic table (Li-Ne), this translates to five basis functions per atom (two s-type and three p-type functions) [12]. The most common minimal basis sets follow the STO-nG scheme, where 'n' indicates the number of Gaussian primitive functions used to approximate each Slater-type orbital [1].

While computationally efficient, minimal basis sets suffer from limited flexibility as they cannot adjust to different molecular environments [1]. They typically produce rough results insufficient for research-quality publications but serve as valuable tools for preliminary investigations or extremely large systems where computational cost prohibits more sophisticated approaches [12].

Table: Common Minimal Basis Sets

| Basis Set | Description | Typical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| STO-3G | 3 Gaussians per STO | Preliminary geometry optimizations, very large systems | Poor description of electron distribution |

| STO-4G | 4 Gaussians per STO | Initial molecular scans | Limited accuracy for properties |

| STO-6G | 6 Gaussians per STO | Educational purposes, conceptual studies | Inadequate for publication-quality results |

Split-Valence Basis Sets

Recognizing that valence electrons primarily participate in chemical bonding, split-valence basis sets introduce multiple basis functions to describe each valence atomic orbital while maintaining a minimal representation for core orbitals [1] [5]. This approach provides the flexibility for electron density to adjust its spatial extent according to the molecular environment—a critical capability for accurate bonding description [1].

The Pople-style notation X-YZg provides key information about basis set composition, where X indicates the number of primitive Gaussians comprising each core atomic orbital basis function, while Y and Z specify the number of primitive Gaussians in the two basis functions describing valence orbitals [1]. For example, the widely used 6-31G basis set uses six primitive Gaussians for core orbitals, with valence orbitals described by one basis function composed of three primitives and another composed of one primitive Gaussian [1] [5].

Table: Common Split-Valence Basis Sets and Their Applications

| Basis Set | Type | Notable Features | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-21G | Double-zeta | Moderate cost | Medium-sized organic molecules |

| 6-31G | Double-zeta | Balanced accuracy/speed | General purpose organic chemistry |

| 6-31G* | Polarized | d-functions on heavy atoms | Bond breaking, conformational analysis |

| 6-31+G | Diffuse | Additional diffuse functions | Anions, excited states, weak interactions |

| 6-311G | Triple-zeta | Improved valence description | High-accuracy thermochemistry |

| 6-311+G* | Polarized & diffuse | Comprehensive features | General high-accuracy applications |

Extended Basis Sets

Extended basis sets incorporate additional mathematical functions to address specific electronic phenomena and systematically approach the complete basis set (CBS) limit [1] [12]. These enhancements include polarization functions, diffuse functions, and higher-zeta representations, providing increasingly accurate descriptions of molecular electronic structure.

Polarization Functions

Polarization functions introduce angular momentum flexibility beyond the atomic ground state configuration, allowing orbitals to distort in response to molecular bonding environments [1] [5]. For example, adding d-type functions to carbon atoms or p-type functions to hydrogen atoms enables more accurate modeling of electron density deformation during bond formation [1]. In Pople basis set notation, a single asterisk () indicates polarization functions on heavy atoms, while double asterisks (*) signify additional polarization on hydrogen and helium atoms [1].

Diffuse Functions

Diffuse functions employ Gaussian basis functions with small exponents to extend the spatial range of atomic orbitals, better describing electron density far from atomic nuclei [1] [5]. These functions prove essential for modeling anions, Rydberg states, dipole moments, and non-covalent interactions where electron density extends significant distances from molecular cores [1]. In standard notation, "+" indicates diffuse functions on heavy atoms, while "++" extends these to hydrogen and helium atoms [1].

Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets

Developed by Dunning and coworkers, correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVNZ, where N=D,T,Q,5,6) provide systematic pathways to the complete basis set limit for post-Hartree-Fock calculations [1]. These sets are specifically optimized for electron correlation effects and enable empirical extrapolation techniques to estimate CBS limit properties through careful calculations at multiple basis set levels [1].

Research Reagents: Computational Tools for Basis Set Applications

Table: Essential Computational Resources for Basis Set Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function/Purpose | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Set Libraries | Basis Set Exchange, EMSL | Centralized repository for basis set specifications | Web portal, API |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Psi4, Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Implementation of basis sets in electronic structure calculations | Academic licensing, open source |

| Quantum Algorithms | QPE with Qubitization | First-quantized Hamiltonian simulation with arbitrary basis sets | Research implementations [13] |

| Composite Methods | ωB97X-3c, B97-3c | Optimized combinations of functionals and basis sets | Integrated in major packages |

| Analysis & Visualization | GaussView, ChemCraft, Jmol | Visualization of molecular orbitals and electron densities | Standalone or package-integrated |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Basis Set Selection Issues

Basis Set Incompleteness Error (BSIE)

Problem: Inaccurate energy predictions due to insufficient basis set flexibility, particularly for correlation energy [6].

Symptoms:

- Systematic underestimation of binding energies

- Poor convergence of molecular properties with basis set size

- Inconsistent thermochemical predictions

Solutions:

- Employ hierarchical convergence studies (DZ → TZ → QZ)

- Use correlation-consistent basis sets for post-Hartree-Fock methods [1]

- Consider composite methods with specifically optimized basis sets [6]

Recommended Protocol: For systematic BSIE reduction, perform calculations with cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, and cc-pVQZ basis sets, then extrapolate to the complete basis set limit using established protocols.

Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)

Problem: Artificial lowering of interaction energies due to "borrowing" of basis functions from adjacent molecules [6].

Symptoms:

- Overestimation of binding energies in intermolecular complexes

- Unphysical long-range interactions

- Size-dependent errors in cluster calculations

Solutions:

- Apply Counterpoise Correction (CP) methodology

- Use specifically optimized basis sets with reduced BSSE (e.g., vDZP) [6]

- Employ triple-zeta basis sets or larger where computationally feasible

Recommended Protocol: For accurate non-covalent interaction energies, use the vDZP basis set with B97-D3BJ or r2SCAN-D3(BJ) functionals, which demonstrate reduced BSSE while maintaining computational efficiency [6].

Computational Resource Limitations

Problem: Prohibitive computational costs when applying high-accuracy basis sets to large systems.

Symptoms:

- Excessive computation times for routine calculations

- Memory limitations during integral evaluation

- Disk space exhaustion for wavefunction storage

Solutions:

- Implement density fitting or resolution-of-identity approximations

- Use effective core potentials for heavy elements

- Employ fragmented or embedding methodologies

- Select Pareto-efficient basis sets like vDZP that balance cost and accuracy [6]

Recommended Protocol: For large systems (>100 atoms), begin with a double-zeta polarized basis set like 6-31G* or vDZP, then apply single-point energy corrections with larger basis sets on optimized geometries.

Frequently Asked Questions: Basis Set Selection Strategies

Q1: What basis set should I use for initial geometry optimizations of drug-like molecules?

For initial geometry optimizations of pharmaceutical compounds, we recommend the 6-31G* or vDZP basis sets. The 6-31G* provides balanced performance for organic molecules, while vDZP offers particularly low basis set superposition error and has demonstrated excellent performance across multiple density functionals without requiring reparameterization [6]. These sets provide sufficient flexibility for bond length and angle optimization while remaining computationally tractable for molecules containing 50-100 atoms.

Q2: When are diffuse functions absolutely necessary in basis set selection?

Diffuse functions become essential when studying: (1) Anionic systems, where electron density is more spatially extended; (2) Non-covalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, and dispersion interactions; (3) Rydberg states and spectroscopic properties involving excited states with diffuse character; (4) Systems with significant dipole moments or charge separation; (5) Halogen-containing compounds where lone pairs require extended description [1] [5]. For these applications, basis sets like 6-31+G* or aug-cc-pVDZ provide substantial improvements over their non-diffuse counterparts.

Q3: How does the vDZP basis set achieve triple-zeta quality at double-zeta cost?

The vDZP basis set employs several innovative strategies to enhance efficiency: (1) Extensive use of effective core potentials to remove core electrons from explicit calculation; (2) Deeply contracted valence basis functions optimized specifically for molecular environments; (3) Careful balancing of primitive composition to minimize BSSE nearly to triple-zeta levels [6]. Benchmark studies demonstrate that vDZP with various density functionals produces accuracy approaching conventional triple-zeta basis sets while maintaining the computational cost characteristic of double-zeta sets [6].

Q4: What represents the best practice for basis set selection in high-accuracy thermochemical calculations?

For publication-quality thermochemical predictions, we recommend a hierarchical approach: (1) Begin with geometry optimization at the double-zeta polarized level (6-31G* or def2-SVP); (2) Perform frequency calculations at the same level to characterize stationary points and obtain thermal corrections; (3) Execute single-point energy calculations using a triple-zeta basis set (cc-pVTZ or def2-TZVP) with electron correlation methods (MP2, CCSD(T), or double-hybrid DFT); (4) When possible, extrapolate to the complete basis set limit using correlation-consistent basis sets of increasing quality [1] [6].

Q5: How do basis set requirements differ between wavefunction-based and DFT methods?

Wavefunction-based electron correlation methods (MP2, CCSD, CCSD(T)) typically demand higher-level basis sets with polarization and diffuse functions to accurately capture correlation energies. In contrast, many density functionals exhibit faster convergence with basis set size, often providing reasonable results with double-zeta polarized sets [1] [6]. The vDZP basis set has demonstrated particular efficiency with DFT methods, delivering near-triple-zeta accuracy across multiple functional classes without method-specific reparameterization [6].

Q6: What recent advances in basis set development impact drug discovery applications?

Recent progress includes: (1) Composite methods with specially optimized basis sets (e.g., ωB97X-3c) that deliver high accuracy with reduced computational cost [6]; (2) General-purpose double-zeta basis sets like vDZP that show exceptional performance across multiple property types [6]; (3) Implementation of novel algorithms enabling first-quantized quantum chemical calculations with arbitrary basis sets [13]; (4) Systematic optimization of basis sets for specific molecular properties like NMR shielding constants or optical spectra.

Advanced Protocols: Basis Set Implementation Strategies

Protocol for Systematic Basis Set Convergence Studies

Purpose: To establish the convergence behavior of molecular properties with respect to basis set size and extrapolate to the complete basis set limit.

Procedure:

- Select a hierarchy of correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ)

- Perform identical calculations with each basis set level

- Plot the target property (energy, frequency, etc.) versus basis set cardinal number

- Apply appropriate extrapolation formulae to estimate CBS limit values

- Calculate differences between consecutive levels to assess convergence

Application Notes: This protocol proves particularly valuable for benchmarking new methodologies or establishing reference data for specific molecular systems.

Protocol for Balanced Basis Set Selection in Drug Discovery

Purpose: To select computationally efficient yet accurate basis sets for high-throughput screening of pharmaceutical compounds.

Procedure:

- For geometry optimizations of organic molecules: Use 6-31G* or vDZP basis sets

- For conformational analysis: Employ 6-31G* with empirical dispersion corrections

- For non-covalent interaction assessment: Implement 6-31+G* or def2-SVPD with counterpoise correction

- For final single-point energy evaluations: Apply cc-pVTZ or def2-TZVP basis sets

- For excited state properties: Utilize aug-cc-pVDZ or similar diffuse-containing sets

Application Notes: The vDZP basis set demonstrates exceptional performance across multiple stages of this protocol when paired with modern density functionals [6].

Emerging Methodologies and Future Directions

The development of novel basis sets continues to evolve, with several promising directions impacting computational drug discovery. Recent work demonstrates that first-quantized quantum chemical calculations can now employ arbitrary basis sets, potentially enabling more efficient quantum algorithms for molecular electronic structure problems [13]. Additionally, the systematic optimization of problem-specific basis sets for pharmaceutical applications represents an active research frontier.

Composite methodologies that integrate specialized basis sets with modern density functionals and empirical dispersions corrections continue to narrow the gap between computational cost and chemical accuracy [6]. These approaches particularly benefit drug discovery applications where balanced treatment of diverse chemical environments and interaction types proves essential for predictive simulations.

The Role of Polarization and Diffuse Functions in Capturing Electron Density

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Why is my calculated molecular polarizability significantly lower than reference values?

This often indicates missing diffuse functions in your basis set [4]. Diffuse functions are large-sized Gaussian functions with small exponents that improve the description of electron density far from the nuclei [4].

Recommended Solution:

- Add diffuse functions: Switch from a standard basis set to its augmented version (e.g., from 6-31G(d) to 6-31++G(d)) [1] [4].

- Application context: Essential for properties involving long-range interactions such as molecular polarizabilities, electron affinities, and intermolecular interactions [4].

Methodology for Verification:

- Calculate the polarizability using your current basis set (e.g., 6-31G(d)).

- Recalculate the property using a basis set with diffuse functions (e.g., 6-31++G(d) or aug-cc-pVDZ).

- Compare the results with reference data or higher-level calculations. A significant increase toward the reference value confirms the issue.

Why are my computed intermolecular interaction energies too attractive?

This typically signals Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE), where basis functions of one molecule artificially improve the electron density description of another, overestimating binding [4] [14].

Recommended Solution:

- Apply Counterpoise (CP) Correction: Calculate the energy of each monomer using the entire basis set of the complex [14].

- Use larger basis sets: BSSE is more pronounced in smaller basis sets. For more reliable results, use at least triple-ζ basis sets, for which CP correction is still beneficial [14].

Methodology for Counterpoise Correction:

- Compute the energy of the complex (AB) with its full basis set:

E_AB(AB). - Compute the energy of monomer A within the complex's full basis set:

E_A(AB). - Compute the energy of monomer B within the complex's full basis set:

E_B(AB). - The CP-corrected interaction energy is:

ΔE_CP = E_AB(AB) - E_A(AB) - E_B(AB)[14].

My geometry optimization predicts incorrect molecular shapes. What's wrong?

This problem frequently arises from insufficient flexibility in the basis set to accurately describe electron density distortion during bond formation [4].

Recommended Solution:

- Add polarization functions: These higher angular momentum functions (e.g., d-functions on carbon, p-functions on hydrogen) allow orbitals to change shape and are crucial for accurate molecular geometries and barrier heights [1] [4].

Methodology for Testing:

- Optimize the geometry with a standard double-zeta basis set (e.g., 6-31G).

- Re-optimize with a polarized basis set (e.g., 6-31G(d) or cc-pVDZ).

- Compare the resulting geometries. Improvements in bond lengths and angles with the polarized set indicate its necessity.

How can I achieve high accuracy without the cost of very large basis sets?

For systematic improvement, correlation-consistent basis sets are designed to converge toward the complete basis set (CBS) limit [1] [4].

Recommended Solution:

- Use a composite method: Methods like ωB97X-3c use specially designed, efficient double-zeta basis sets (e.g., vDZP) that minimize BSSE and offer accuracy接近 triple-ζ levels at lower cost [6].

- Basis set extrapolation: For the highest accuracy, perform calculations with two consecutive basis set sizes (e.g., cc-pVTZ and cc-pVQZ) and extrapolate to the CBS limit [14].

Extrapolation Methodology (Example):

The exponential-square-root function can be used for extrapolation [14]:

E_CBS ≈ E_X - A * exp(-α * X)

where E_X is the energy calculated with a basis set of cardinal number X (2 for double-ζ, 3 for triple-ζ, etc.), and α is an optimized parameter (e.g., 5.674 for B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP-TZVPP extrapolation) [14].

Basis Set Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the capabilities of different basis set types and recommendations for specific chemical problems.

Table 1: Basis Set Capabilities and Recommendations

| Basis Set Type | Key Features | Recommended For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (e.g., STO-3G) [4] | Minimum number of functions; computationally inexpensive. | Initial geometry optimizations; very large systems for qualitative study. | Low accuracy; poor description of bonding and electronic properties [4]. |

| Split-Valence (e.g., 6-31G) [1] | Multiple functions for valence orbitals; improved bonding description. | Routine calculations of molecular geometry and energies. | Lacks flexibility for electron distortion and long-range effects. |

| Polarized (e.g., 6-31G(d)) [1] | Adds higher angular momentum functions (d, f). | Accurate molecular geometries, vibrational frequencies, and reaction barrier heights [1] [4]. | Increased computational cost. |

| Diffuse (e.g., 6-31+G(d)) [1] [4] | Adds large, sparse functions for "electron tail." | Anions, excited states, weak interactions (H-bonding, van der Waals), and polarizabilities [1] [4]. | Higher cost; potential SCF convergence issues [14]. |

| Correlation-Consistent (e.g., cc-pVXZ) [1] [4] | Systematic hierarchy for converging to CBS limit. | High-accuracy benchmark studies; extrapolations to CBS limit [1] [4]. | High computational cost for larger X values. |

Table 2: Performance of Different Double-Zeta Basis Sets with Various Functionals This table, inspired by a 2024 study, shows that the vDZP basis set can be used broadly to achieve good accuracy with low computational cost. The values are weighted total mean absolute deviations (WTMAD2) from the GMTKN55 benchmark suite; lower is better [6].

| Functional | def2-QZVP (Large Ref.) | vDZP | 6-31G(d) | def2-SVP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-D3BJ | 8.42 | 9.56 | Data Missing | Data Missing |

| r2SCAN-D4 | 7.45 | 8.34 | Data Missing | Data Missing |

| B3LYP-D4 | 6.42 | 7.87 | Data Missing | Data Missing |

| M06-2X | 5.68 | 7.13 | Data Missing | Data Missing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Basis Sets for Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Reagent (Basis Set) | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| 6-31G(d) (Pople-style) | A balanced double-zeta polarized basis set. | A common default for optimizing molecular structures and calculating vibrational frequencies for medium-sized organic molecules [1]. |

| cc-pVDZ (Dunning-style) | A double-zeta correlation-consistent basis set. | The starting point in the correlation-consistent hierarchy for post-Hartree-Fock methods like MP2 or CCSD(T) [1] [4]. |

| 6-311++G(2df,2pd) | A triple-zeta basis with multiple polarization and diffuse functions. | High-accuracy calculations of molecular properties, including energies and spectroscopic constants, for small to medium molecules [1]. |

| vDZP | A modern, efficient double-zeta polarized basis set. | Designed for composite methods (e.g., ωB97X-3c); provides near triple-ζ accuracy at double-ζ cost for various density functionals [6]. |

| aug-cc-pVTZ | A triple-zeta correlation-consistent basis with diffuse functions. | The gold standard for high-accuracy calculations of properties sensitive to electron density, such as weak intermolecular interactions and electron affinities [4]. |

| Pyralomicin 2b | Pyralomicin 2b, MF:C19H19Cl2NO8, MW:460.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DCN-83 | DCN-83, MF:C20H18BrN3S, MW:412.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Basis Set Selection Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the Complete Basis Set (CBS) limit and why is it a theoretical goal? The Complete Basis Set (CBS) limit is the exact solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation that would be obtained using an infinitely large, complete basis set. In practice, this is unattainable, so the goal is to approach this limit through calculations with progressively larger basis sets and subsequent extrapolation. Reaching the CBS limit is crucial for obtaining chemically accurate results (typically within ~1 kcal/mol) that are independent of the one-electron basis set used in the calculation [15].

FAQ 2: My computational resources are limited. What is the most efficient way to approach the CBS limit? For high-accuracy methods like CCSD(T), a highly efficient strategy is the combined FNO-NAF-NAB approach (Frozen Natural Orbitals - Natural Auxiliary Functions - Natural Auxiliary Basis). This method can achieve speedups of 7, 5, and 3 times for double-, triple-, and quadruple-ζ basis sets, respectively, without any loss of accuracy. This allows for the calculation of reaction energies and barrier heights well within chemical accuracy for molecules with more than 40 atoms [16].

FAQ 3: How does the choice of basis set affect my results in Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) calculations? The cost of QPE, dominated by the Hamiltonian 1-norm, scales at least quadratically with the number of molecular orbitals. Employing a Frozen Natural Orbital (FNO) strategy starting from a large basis set can substantially reduce QPE resources. This approach can yield up to an 80% reduction in the 1-norm (λ) and a 55% reduction in the number of orbitals needed, while still effectively capturing dynamic correlation effects [8].

FAQ 4: I have computed energies with different basis set sizes. How do I extrapolate to the CBS limit? The two most common schemes are the exponential and power function extrapolations. For example, with correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ), you can use the following formulas [15]:

- Exponential: ( EX = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha X} )

- Power Function: ( EX = E{\infty} + B X^{-\alpha} ) Here, ( X ) is the basis set cardinal number (2 for DZ, 3 for TZ, etc.), ( EX ) is the energy computed with that basis set, ( E{\infty} ) is the CBS limit energy, and ( B ), ( \alpha ) are fitting parameters.

FAQ 5: I am getting inconsistent results for properties like Raman intensities and J-couplings. Could this be related to my basis set? Yes. The normalization of Atomic Orbitals (AOs) in your basis set can physically impact computed molecular properties. Studies show that different normalization procedures can lead to non-negligible shifts—over 50 units in Raman activity and up to 6 Hz for phosphorus J-coupling constants. Ensure you are aware of and consistently apply the same normalization scheme, especially when using contracted Gaussian-type orbitals [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Computational Cost for CCSD(T) CBS Limit Calculations

Problem: CCSD(T) calculations with large basis sets are computationally prohibitive. Solution:

- Implement the FNO-NAF-NAB approach:

- FNO (Frozen Natural Orbitals): Reduce the molecular orbital space by diagonalizing a lower-level (e.g., MP2) one-particle density matrix and retaining only the natural orbitals with the highest occupation numbers [16].

- NAF (Natural Auxiliary Function): Use this data compression technique to reduce the size of the auxiliary basis set required for the density fitting (DF) approximation [16].

- NAB (Natural Auxiliary Basis): Apply this newer approach to decrease the size of the auxiliary basis needed for the expansion of explicitly correlated geminals (F12 methods) [16].

- Combine these approximations for a cumulative speedup, making near basis-set-limit computations feasible for molecules with 50+ atoms [16].

Issue 2: Inefficient Resource Scaling in Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

Problem: The resource requirements (Hamiltonian 1-norm, qubit count) for QPE grow too quickly when expanding the active space to include dynamic correlation. Solution:

- Avoid using small, coarse basis sets directly. Instead, generate your active space from Frozen Natural Orbitals (FNOs) derived from a large, high-quality parent basis set [8].

- This strategy focuses on improving the quality of the orbital basis, not just its size. It has been shown to reduce the number of orbitals by 55% and the Hamiltonian 1-norm by up to 80% compared to using a smaller parent basis, while maintaining accuracy [8].

Issue 3: Inconsistent CBS Extrapolation Results

Problem: Extrapolated CBS energies vary significantly depending on the formula or basis sets used. Solution:

- Use a consistent set of basis sets from a family designed for systematic convergence, such as Dunning's correlation-consistent (cc-pVXZ) series [15].

- Employ a multi-point extrapolation scheme (e.g., 3-point) for greater reliability than a 2-point one [15].

- Compare multiple extrapolation formulas. If results differ, consider the system's nature:

Issue 4: Unintended Basis Set Reduction and Normalization Errors

Problem: Quantum chemistry packages may automatically and silently apply basis set reduction or normalization, leading to irreproducible results. Solution:

- Identify the default behavior of your software (e.g., Gaussian) regarding basis set internal reduction [17].

- Use explicit keywords to prevent automatic reduction (e.g., in Gaussian, the keyword that prevents basis set reduction for approach

A2) [17]. - Source basis sets consistently from a reliable database like the Basis Set Exchange (BSE) and document this in your methodology (approach

A3Exc) [17]. - For the highest precision, consider using a tool like BasisSculpt to explicitly control and document the normalization procedure, retaining both positive and negative contraction coefficients (approach

A4BS) [17].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Performance of Efficiency Strategies for High-Level Electronic Structure Methods

| Method / Strategy | System Type Tested | Typical Speedup | Accuracy Preservation | Key Metric Improved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined FNO-NAF-NAB for CCSD(F12*)(T+) [16] | Molecules with >40 atoms (closed & open-shell) | 7x (DZ), 5x (TZ), 3x (QZ) | Within chemical accuracy (~1 kcal/mol) | Wall time / Feasibility |

| FNO for Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) [8] | Dataset of 58 small organic molecules, N₂ dissociation | N/A (Resource Reduction) | Chemically accurate ground state energies | 55% fewer orbitals, 80% lower 1-norm (λ) |

| Direct Exponent Optimization [8] | Small molecules | Up to 10% 1-norm reduction | System-dependent, diminishes with molecular size | Hamiltonian 1-norm (λ) |

| Extrapolation Scheme | Functional Form | Typical Application | Number of Data Points Required | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential | ( EX = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha X} ) | Correlation energies | 2 or 3 | Found to be better than power form for correlation energies [15]. |

| Power Function | ( EX = E{\infty} + B X^{-\alpha} ) | Correlation energies | 2 or 3 | A commonly used, simple model. |

| Mixed Gaussian/Exponential | ( EX = E{\infty} + B e^{-(X-1)} + C e^{-(X-1)^2} ) | Total energies | 3 | Found to fit total energies through cc-pV5Z better than pure exponential [15]. |

| Inverse Power (Schwartz) | ( EX = E{\infty} + B (X + \frac{1}{2})^{-4} ) | Two-electron systems | 2 or 3 | Motivated by perturbation theory for He-like systems [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Three-Point CBS Extrapolation for Correlation Energy

Purpose: To obtain a correlation energy close to the CBS limit using a series of correlation-consistent basis sets. Materials: Access to a quantum chemistry program (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, CFOUR); molecular geometry. Steps:

- Compute: Perform energy calculations (e.g., at the MP2 or CCSD(T) level) using three basis sets of increasing size, such as cc-pVTZ (X=3), cc-pVQZ (X=4), and cc-pV5Z (X=5).

- Select Model: Choose an extrapolation formula. The exponential form is often recommended for correlation energies [15]: ( EX = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha X} )

- Solve the System: For cardinal numbers ( n1, n2, n3 ) (e.g., 3, 4, 5) and their corresponding energies ( E1, E2, E3 ), solve for the CBS limit energy ( E{\infty} ) and parameters ( B ), ( \alpha ). This can be done by numerically solving the system of equations [15]: ( E1 = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha n1} ) ( E2 = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha n2} ) ( E3 = E{\infty} + B e^{-\alpha n3} )

- Validate: If possible, compare the extrapolated result with a calculation using an even larger basis set (e.g., cc-pV6Z) to assess convergence.

Protocol 2: Generating an Efficient Active Space via Frozen Natural Orbitals (FNOs)

Purpose: To create a compact and accurate active space for expensive quantum algorithms like QPE, capturing dynamic correlation with fewer resources. Materials: A pre-computed Hartree-Fock reference using a large parent basis set (e.g., aug-cc-pVQZ). Steps:

- Compute Density Matrix: Perform a lower-level, inexpensive correlation calculation (e.g., MP2) using the large parent basis set to obtain a one-particle density matrix [8] [16].

- Diagonalize: Diagonalize this density matrix to obtain Natural Orbitals (NOs) and their corresponding occupation numbers [8] [16].

- Truncate: Discard the virtual NOs with the lowest occupation numbers, as these contribute least to the correlation energy. The remaining set of orbitals constitutes the FNO active space [8] [16].

- Proceed: Use this reduced FNO active space in the subsequent high-level calculation (e.g., QPE, CCSD(T)). The significant reduction in orbitals drastically lowers the computational cost [8].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Decision Workflow for Efficient CBS Limit Approaches

FNO Active Space Construction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for CBS Limit Research

| Item / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose | Example(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets | Systematically improvable basis sets for extrapolation. | cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5,6); aug-cc-pVXZ (with diffuse functions) [15] [17] | The foundation for reliable CBS extrapolation. |

| Frozen Natural Orbitals (FNOs) | Reduces orbital space for high-level methods, capturing dynamic correlation efficiently. | Used in CCSD(T) and QPE [8] [16] | Critical for reducing cost in QPE and CCSD(T). Parent basis set quality is key. |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | Used in Density Fitting (DF) to approximate 4-center electron repulsion integrals. | Various sets tailored to specific orbital basis sets. | The NAF and NAB approximations compress these further [16]. |

| Explicitly Correlated (F12) Methods | Improves basis set convergence by explicitly including the electron-electron distance (râ‚â‚‚) in the wavefunction. | CCSD(F12*)(T+) [16] | Reduces the need for very large orbital basis sets. |

| Extrapolation Calculators | Automates the application of CBS extrapolation formulas. | Jamberoo CBS Calculator [15] | Solves complex equations for E∞, B, and α. |

| Basis Set Normalization Tools | Ensures control and reproducibility of basis set definitions. | BasisSculpt tool [17] | Prevents silent errors from automatic internal reduction in software. |

| Norselic acid B | Norselic acid B, MF:C29H44O4, MW:456.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Milbemycin A4 oxime | Milbemycin A4 oxime, MF:C32H45NO7, MW:555.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Selecting the Right Tool: A Practical Guide to Basis Sets for Biomolecular and Materials Research

Pople vs. Dunning Basis Sets for HF, DFT, and Correlated Methods

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My NMR calculations for phosphorus (³¹P) show irregular, non-converging results with the aug-cc-pVXZ basis sets. What is the issue and how can I fix it?

This is a known issue specifically for third-row elements (Na-Cl) when using standard correlation-consistent valence basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVXZ). The scatter in results, where shieldings do not converge regularly as you increase the basis set size (e.g., from DZ to TZ), occurs because these basis sets lack sufficient flexibility in the core-electron region [18].

Recommended Solution:

- Switch to a core-valence basis set: Use the Dunning aug-cc-pCVXZ family instead. These are specifically designed to correlate core and core-valence electrons and have been shown to restore exponential convergence for NMR properties of third-row elements [18].

- Alternative Basis Sets: The Jensen aug-pcSseg-n or the compact Karlsruhe x2c-Def2 basis sets are also excellent alternatives that provide regular convergence for NMR shieldings [18].

Q2: For high-accuracy energy calculations aiming for the Complete Basis Set (CBS) limit, which basis set family is more suitable and how is it implemented?

The Dunning correlation-consistent family (cc-pVXZ) is the definitive choice for systematically approaching the CBS limit through extrapolation techniques [19]. Its design allows for a regular, exponential improvement in calculated energies with increasing cardinal number X (DZ, TZ, QZ, etc.) [18].

Experimental Protocol for CBS Extrapolation: A common composite method for reaching a high-accuracy CBS energy involves a multi-stage approach. The following workflow illustrates a typical protocol for a CCSD(T) calculation using basis set extrapolation [19]:

The total energy is constructed as:

- Reference Energy: The SCF energy is computed with a large basis, typically aug-cc-pVQZ [19].

- Correlation Energy: The MP2 correlation energy is obtained by a two-point Helgaker extrapolation using the large triple- and quadruple-zeta (TQ) basis sets [19].

- High-Level Correction: A delta correction is added, which is the difference between the CCSD(T) and MP2 correlation energies, extrapolated using double- and triple-zeta (DT) basis sets [19].

Q3: How do I choose between a Pople-style basis set and a Dunning-style basis set for routine DFT calculations on medium-sized organic molecules?

The choice involves a trade-off between computational cost and accuracy.

- Pople Basis Sets (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311G): These are a good choice for initial screening and routine calculations due to their compact size and computational efficiency. They often provide reasonable results for geometry optimizations and vibrational frequency calculations [20].

- Dunning Basis Sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ): These are the preferred choice for higher-accuracy benchmark calculations, especially for properties like interaction energies, reaction barriers, and spectroscopic constants, due to their systematic convergence towards the CBS limit [18].

Quantitative Comparison in Band Gap Prediction: The table below summarizes a benchmark study on predicting the band gaps of conjugated polymers, showing the performance of different functionals and basis sets [20].

| Functional | Basis Set | Performance for Band Gap Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| B3PW91 | cc-pVDZ | Best performance in the study |

| B3PW91 | 6-31G(d,p) | Also gives good results |

| B3PW91 | 6-311G(d,p) | Also gives good results |

| B3PW91 | DGDZVP | Also gives good results |

| B3LYP | Various | Less accurate than B3PW91 for this property |

Q4: What are the essential "research reagents" – the standard basis sets and methodologies – I should have in my computational toolkit?

Every computational chemist's toolkit should include a selection of standard basis sets and protocols for different tasks. The table below lists key solutions.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Pople 6-31G(d,p) | A robust double-zeta polarized basis for initial geometry optimizations and frequency calculations on organic molecules [20]. |

| Dunning cc-pVXZ | The standard for correlated methods (MP2, CCSD(T)) and high-accuracy energy calculations via CBS extrapolation [18] [19]. |

| Dunning aug-cc-pCVXZ | Essential for accurate property calculations (e.g., NMR shieldings) of elements in the third row of the periodic table and beyond [18]. |

| Jensen aug-pcSseg-n | Designed for efficient and accurate calculation of molecular properties, including NMR shieldings [18]. |

| Karlsruhe def2-SVP | A compact, efficient basis set from the Ahlrichs family, suitable for DFT calculations on larger systems [21]. |

| CBS Extrapolation | A methodology to approximate the complete basis set result, crucial for obtaining benchmark-quality energies [19]. |

| Core-Valence Correction | A protocol using specific basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pCVXZ) to correct for core-electron effects on molecular properties [18]. |

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Unphysical or Erratic Results for Third-Row Elements

- Symptoms: NMR shieldings, polarizabilities, or other electronic properties do not converge regularly as you increase the basis set size in a Dunning cc-pVXZ series [18].

- Root Cause: Inadequate description of core and core-valence electrons by the standard valence-only basis sets [18].

- Solution: As outlined in FAQ #1, switch to a basis set that includes core-correlating functions, such as aug-cc-pCVXZ or aug-pcSseg-n [18].

Problem 2: Prohibitively Long Computation Times for High-Accuracy Methods

- Symptoms: CCSD(T) or MP2 calculations with large basis sets like cc-pVQZ or cc-pV5Z are too costly.

- Root Cause: The computational cost of correlated methods scales steeply with the number of basis functions.

- Solution: Use a CBS extrapolation strategy. Perform calculations with smaller, more affordable basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ and cc-pVTZ) and mathematically extrapolate to the CBS limit, which is often more accurate than a single calculation with a medium-sized basis [19].

Problem 3: Selecting a Basis Set for a New Project

- Question: How do I systematically choose a basis set for a method I haven't used before?

- Guidance: Follow the decision logic below to select an appropriate basis set based on your target system, method, and desired accuracy.

FAQs on Basis Set Selection for Molecular Properties

1. Which basis set and functional are recommended for accurate dipole moment calculations of conjugated organic molecules? For accurate dipole moments of conjugated donor-acceptor (push-pull) molecules, the B3LYP functional with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set, including anharmonic correction, provides results that align well with experimental data [22]. This combination has been shown to reproduce experimental dipole moments with high accuracy, particularly when the experiments were conducted at temperatures where rotation of substituents is hindered [22]. The APFD functional also yields similar results, while the M062X functional tends to produce larger deviations from experimental values [22].

2. What is a good general-purpose basis set that offers a balance of speed and accuracy for geometry optimizations? The 6-31G* basis set is widely considered the best compromise between computational cost and accuracy for routine calculations, including geometry optimizations [23]. It is a split-valence double-zeta basis set that includes polarization functions on all non-hydrogen atoms, which improves the modeling of core electrons and yields reasonable molecular geometries and energies [1] [23].

3. How do I select a basis set for calculating weak intermolecular interaction energies? Accurate calculation of weak intermolecular interaction energies requires careful basis set selection to minimize Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) [14].

- Using Counterpoise Correction: For calculations employing density functional theory (DFT), counterpoise (CP) correction is recommended when using double-zeta basis sets. For triple-zeta basis sets without diffuse functions, CP correction remains beneficial [14].

- Role of Diffuse Functions: Diffuse functions are important for spanning the intermolecular interaction region and describing fragment polarizabilities. They are often essential with double-zeta basis sets, but may become less critical with triple-zeta basis sets, especially when CP correction is applied [14].

- Efficient Alternative: A practical and simplified approach involves using a basis set extrapolation scheme with the def2-SVP and def2-TZVPP basis sets, which can achieve accuracy comparable to larger, CP-corrected calculations while reducing computational cost and improving SCF convergence [14].

4. When should I use diffuse functions in a basis set? Diffuse functions (denoted by '+' in Pople basis sets or the 'aug-' prefix in Dunning basis sets) are crucial for systems with significant electron density far from the nucleus [1]. You should consider using them for:

- Anions and systems with lone pairs [23].

- Calculating dipole moments and other electric response properties [1].

- Studying weak intermolecular interactions, such as van der Waals complexes [14].

- Rydberg states and other properties where the "tail" of the electron distribution is important [1].

5. What is the difference between the 6-31G* and 6-311G basis sets?* The primary difference lies in the description of the valence electrons. The 6-31G basis set is a double-zeta basis set, meaning valence orbitals are represented by two basis functions [1]. The 6-311G* basis set is a triple-zeta basis set, meaning valence orbitals are represented by three basis functions, providing greater flexibility and potentially higher accuracy at a higher computational cost [1] [23].

6. Are there more modern or efficient alternatives to the traditional Pople-style basis sets? Yes, several modern basis sets offer excellent performance.

- Jensen's pcseg-n: For density-functional theory (DFT) calculations, the

pcsegfamily (e.g.,pcseg-1for double-zeta) often outperforms Pople basis sets like 6-31G* without a significant increase in computational cost [24]. - Ahlrichs's def2: The

def2series (e.g.,def2-SVP,def2-TZVP) are well-optimized, general-purpose basis sets available for a wide range of elements [23] [24]. - Dunning's cc-pVnZ: The correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g.,

cc-pVTZ) are designed for high-accuracy post-Hartree-Fock calculations and for systematically converging to the complete basis set (CBS) limit [1] [24]. For efficiency in DFT, use the segmented variants (e.g.,cc-pVTZ(seg-opt)) [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Calculated dipole moments are overestimated for push-pull conjugated molecules.

- Potential Cause 1: The use of conventional exchange-correlation functionals (like standard B3LYP) with inadequate basis sets can overestimate the degree of intramolecular charge transfer [22].

- Solution: Switch to the B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ model chemistry. Verify the temperature conditions of the experimental data you are comparing against, as internal rotation of substituents can affect the measured dipole moment [22].

- Potential Cause 2: Solvent effects or specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding) in the experimental measurement can lower the observed dipole moment relative to a gas-phase calculation [22].

- Solution: Employ a polarizable continuum model (PCM) to simulate solvent effects in your calculation for a more direct comparison with solution-phase experimental data [22].

Problem: Calculation of interaction energies for a supramolecular complex is inaccurate and computationally expensive.

- Potential Cause: The basis set is too small, leading to a large Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE), or it lacks the necessary features (like diffuse functions) to describe the weak interaction [14].

- Solution 1: Use a triple-zeta basis set with diffuse functions (e.g.,

aug-cc-pVTZ) and apply counterpoise (CP) correction to account for BSSE [14]. - Solution 2 (Efficient): Use a basis set extrapolation scheme. Perform single-point energy calculations with def2-SVP and def2-TZVPP basis sets, then extrapolate to the complete basis set (CBS) limit using the exponential-square-root function with an optimized parameter (α = 5.674 for B3LYP-D3(BJ)) [14]. This approach can yield accuracy comparable to CP-corrected calculations on larger basis sets at a lower cost.

Problem: The SCF procedure fails to converge when using a large, augmented basis set.

- Potential Cause: The inclusion of diffuse functions can make the basis set almost linearly dependent and challenge the SCF convergence [24] [14].

- Solution 1: Use "minimally augmented" basis sets (e.g.,

ma-TZVPP) which include a minimal set of diffuse functions necessary for good performance, reducing convergence problems [14]. - Solution 2: Start the calculation from a reasonable initial guess (e.g., a core Hamiltonian or the orbitals from a smaller basis set calculation). You can also use the

SCFTOLERANCE=HIGHkeyword to tighten the convergence criteria [23].

Basis Set Performance and Computational Cost

The table below summarizes the properties, strengths, and relative computational cost of commonly used basis sets, using Hartree-Fock energy calculations for acetone as an example [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Basis Sets for Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Basis Set | Type | Polarization Functions | Diffuse Functions | # Basis Functions (Acetone) | Relative Time | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STO-3G [1] | Minimal | No | No | 26 | 0.05 | Quick preliminary scans, very large systems. |

| 3-21G* [23] | Split-Valence | On atoms >Ne | No | 48 | 0.2 | Initial geometry optimizations. |

| 6-31G* [1] [23] | Split-Valence | On all heavy atoms | No | 72 | 1 | Best compromise; geometry optimizations, frequency calculations. |

| 6-31+G* [1] [23] | Split-Valence | On all heavy atoms | On heavy atoms | 106 | 6 | Anions, excited states, weak interactions. |

| 6-311+G* [23] | Triple-Split-Valence | On all heavy atoms | On heavy atoms | 106 | 6 | Higher accuracy single-point energies. |

| aug-cc-pVTZ [1] [22] | Correlation-Consistent | Yes (multiple) | Yes | 204 | 82 | High-accuracy property calculations (e.g., dipoles). |

| def2-TZVPP [23] [14] | Triple-Zeta | Yes | No* | Similar to cc-pVTZ | Similar to cc-pVTZ | General-purpose, high-accuracy calculations. |

*Minimally augmented versions (ma-def2-TZVPP) are available for weak interactions [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Accurate Dipole Moments for Conjugated Molecules This protocol is derived from research on conjugated donor-acceptor systems [22].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometry using the

B3LYP/6-31G*model chemistry. - Frequency Calculation: Perform a frequency calculation at the same level of theory to confirm the structure is a minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain thermal corrections.

- High-Level Single Point: Calculate the single-point energy and properties (including the dipole moment) using the B3LYP functional and the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set [22].

- Anharmonic Correction (Optional): For the highest accuracy, especially when comparing to gas-phase experimental data at low temperatures, apply anharmonic correction in the frequency calculation [22].

- Consider Internal Rotation: If the molecule has flexible substituents, confirm whether the experimental data was collected under conditions of hindered or free rotation. For high-temperature/free-rotation conditions, the dipole moment may need to be calculated as a Boltzmann average over all low-energy rotamers [22].

Protocol 2: Calculating Weak Intermolecular Interaction Energies with BSSE Correction This protocol uses the counterpoise method to correct for Basis Set Superposition Error [14].

- Geometry Preparation: Obtain the geometry of the dimer complex (AB) and the isolated monomers (A and B). It is best if these are optimized at a consistent level of theory.

- Single Point Calculations: Perform a series of single-point energy calculations using a suitable method (e.g.,

B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPP) [14]:E_AB(AB): Energy of the complex with its own basis set.E_A(AB): Energy of monomer A in the geometry and basis set of the complex.E_B(AB): Energy of monomer B in the geometry and basis set of the complex.E_A(A): Energy of monomer A with its own basis set.E_B(B): Energy of monomer B with its own basis set.

- Calculate BSSE and CP-Corrected Energy:

BSSE = [E_A(AB) - E_A(A)] + [E_B(AB) - E_B(B)]ΔE_CP = E_AB(AB) - E_A(AB) - E_B(AB)

Protocol 3: Basis Set Extrapolation to the Complete Basis Set (CBS) Limit for Interaction Energies This protocol provides an efficient and accurate alternative to direct calculation with very large basis sets [14].

- Geometry Preparation: Use a well-optimized geometry for the complex and monomers.

- Single Point Calculations: Perform single-point energy calculations for the complex and each monomer using two different basis sets: def2-SVP and def2-TZVPP [14].

- Calculate Interaction Energies: Compute the raw (uncorrected) interaction energy,

ΔE_X, for each basis setXusing the supermolecular approach:ΔE_X = E_AB,X - E_A,X - E_B,X. - Extrapolate to CBS Limit: Use the exponential-square-root (expsqrt) formula to extrapolate the interaction energies obtained from the two basis sets to the CBS limit [14]:

ΔE_CBS = ΔE_TZ - (ΔE_TZ - ΔE_DZ) / (e^(-5.674/√(3)) - e^(-5.674/√(2))) * e^(-5.674/√(3))- Where

ΔE_DZis the interaction energy with def2-SVP,ΔE_TZis the interaction energy with def2-TZVPP, and the exponent parameterα = 5.674is optimized for B3LYP-D3(BJ) [14].

Workflow for Basis Set Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate basis set based on the target molecular property and available computational resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 2: Key Software, Functionals, and Basis Sets for Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 16 [22] | Software Suite | Performs a wide variety of quantum chemical calculations. | Used in cited research for geometry optimization, frequency, and anharmonic calculations [22]. |

| B3LYP [22] | Density Functional | A hybrid functional for general-purpose calculations of energies, structures, and properties. | Recommended for accurate dipole moments of conjugated molecules [22]. |

| aug-cc-pVTZ [22] | Basis Set | A correlation-consistent basis set with diffuse functions. | Used for high-accuracy dipole moment and property calculations [22]. |

| def2-SVP / def2-TZVPP [14] | Basis Set Series | A family of efficient, modern basis sets. | Used in basis set extrapolation protocols for weak interaction energies [14]. |

| Counterpoise (CP) Correction [14] | Computational Method | Corrects for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE). | Essential for accurate weak interaction energies with small-to-medium basis sets [14]. |

| D3 Dispersion Correction [14] | Empirical Correction | Adds long-range dispersion interactions to DFT. | Often used with the B3LYP functional (B3LYP-D3) for improved modeling of weak forces [14]. |

| Mureidomycin D | Mureidomycin D, MF:C40H53N9O13S, MW:900.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Maridomycin I | Maridomycin I, CAS:35908-44-2, MF:C43H71NO16, MW:858.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the vDZP basis set and when should I consider using it? The vDZP is a specially developed double-zeta polarized basis set that extensively uses effective core potentials (ECPs) to remove core electrons and relies on deeply contracted valence basis functions optimized on molecular systems. You should consider using it for rapid quantum chemical calculations with a variety of density functionals when you need to balance computational cost and accuracy, particularly for main-group thermochemistry, non-covalent interactions, and barrier heights. It minimizes basis-set superposition error (BSSE) almost down to the triple-zeta level, making it effective despite its relatively small size. [6] [25]

How does the performance of vDZP compare to conventional double- and triple-zeta basis sets? The vDZP basis set substantially outperforms conventional double-zeta basis sets like 6-31G(d) and def2-SVP in accuracy, often delivering results comparable to triple-zeta basis sets but at a lower computational cost than standard triple-zeta sets. However, its computational cost is approximately 40% higher than a typical triple-zeta basis set for organic molecules due to a higher number of primitive Gaussian functions, positioning it somewhere between triple-zeta and quadruple-zeta in cost. For molecules with heavy atoms (beyond the second row), vDZP can be faster than triple-zeta basis sets because it uses ECPs. [6] [26]

Can I use the vDZP basis set with density functionals other than ωB97X? Yes, the vDZP basis set demonstrates general applicability across a wide variety of density functionals without requiring method-specific reparameterization. Research has shown it produces efficient and accurate results with functionals including B3LYP-D4, M06-2X, B97-D3BJ, and r2SCAN-D4, performing well on comprehensive benchmarks like the GMTKN55 database. [6] [27] [25]