A Practical Guide to Basis Set Convergence: Achieving Accuracy in Quantum Chemistry for Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating and ensuring basis set convergence in quantum chemical calculations.

A Practical Guide to Basis Set Convergence: Achieving Accuracy in Quantum Chemistry for Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating and ensuring basis set convergence in quantum chemical calculations. It covers the fundamental principles of systematic convergence to the complete basis set (CBS) limit, explores practical methodologies and extrapolation techniques for accelerating convergence, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for complex systems like biomolecules and metal complexes, and discusses validation through high-accuracy benchmarks and uncertainty quantification. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to empower scientists to achieve reliable, chemically accurate results crucial for applications in biomedical research and clinical development.

Understanding Basis Set Convergence: The Path to the Complete Basis Set Limit

Defining the Complete Basis Set (CBS) Limit and Its Critical Importance

In theoretical and computational chemistry, solving the electronic Schrödinger equation accurately requires representing the electronic wave function using a set of mathematical functions known as a basis set [1]. The exact solution for any quantum chemical method is defined by the complete basis set (CBS) limit—the theoretical point where an infinite number of basis functions are employed, thus completely spanning the one-electron space [2]. In practical computation, however, scientists must work with finite basis sets, which introduces a significant source of error known as basis set truncation error [3]. The systematic approach to estimating the CBS limit without performing computationally prohibitive calculations with extremely large basis sets is called CBS extrapolation [4] [5]. This technique has revolutionized the field of computational chemistry by providing a controlled, systematic pathway to approach the accuracy of the CBS limit, which is particularly vital for highly correlated electronic structure methods where basis set effects are both substantial and systematic [4] [3].

The Core Problem: Why the CBS Limit Matters

The Twofold Challenge of Quantum Chemical Calculations

Quantum chemical calculations face two major, interconnected sources of error when solving the electronic Schrödinger equation. The first concerns the expansion of the many-electron wavefunction in terms of Slater determinants (the "method"), and the second involves the representation of 1-particle orbitals by a finite basis set [3]. These errors are often strongly coupled, sometimes leading to fortuitous error cancellations where low-level methods with small basis sets might produce better agreement with experiment than more sophisticated approaches [3]. While such cancellations might seem beneficial, they undermine the transferability and predictive power of computational models. The true accuracy of a chosen method is only revealed at the CBS limit, which removes all errors due to the basis set approximation and provides results indicative of the method's intrinsic capabilities [3].

Practical Consequences of Basis Set Incompleteness

The practical implications of basis set incompleteness are profound across computational chemistry applications:

- Molecular Energies: Convergence of total energies is slow, requiring very large basis sets to achieve chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol or 1.6 mHa) [2].

- Reaction Barriers: Activation energies and reaction enthalpies show significant basis set dependence, potentially altering mechanistic interpretations [4].

- Molecular Properties: Properties such as dipole moments converge more slowly with basis set size than total energies [2].

- Non-Covalent Interactions: Weak interactions like hydrogen bonding and dispersion are particularly sensitive to basis set quality.

- Drug Design Applications: Inaccurate energy calculations can mislead structure-activity relationships and binding affinity predictions.

The computational cost of correlated electronic structure methods such as CCSD(T) scales unfavorably with system size and basis set size, making direct calculations near the CBS limit prohibitively expensive for all but the smallest molecules [4]. This cost-quality tradeoff presents a fundamental challenge that CBS extrapolation methodologies aim to resolve.

Methodological Approaches: Pathways to the CBS Limit

Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets

The development of correlation-consistent basis sets by Dunning and coworkers (cc-pVnZ, where n = D, T, Q, 5, 6 representing double-, triple-, quadruple-zeta, etc.) represented a breakthrough in systematic basis set development [4] [3]. These basis sets are specifically designed with several key characteristics:

- Systematic Construction: Each increase in the cardinal number n adds higher angular momentum functions important for electron correlation.

- Hierarchical Convergence: Properties converge regularly toward the CBS limit as n increases.

- Adaptability: Available in standard, augmented (diffuse functions), and core-valence correlated versions for different applications.

These basis sets form the foundation for most modern CBS extrapolation schemes because their systematic construction enables the development of mathematical models for the convergence behavior of energies and properties [3] [6].

Mathematical Foundations of CBS Extrapolation

CBS extrapolation relies on mathematical models that describe how energies approach the CBS limit as basis set quality improves. These models enable two-point or three-point extrapolations using results from moderately-sized basis sets to estimate the CBS limit [4] [6].

Hartree-Fock Energy Extrapolation

The Hartree-Fock (or SCF) component of the total energy displays exponential convergence with basis set size. A commonly used extrapolation scheme for the SCF energy employs the formula [4]:

[ E{\text{SCF}}(n) = E{\text{SCF}}(\text{CBS}) + A e^{-zn} ]

where ( n ) is the cardinal number, ( E_{\text{SCF}}(\text{CBS}) ) is the CBS limit SCF energy, and ( A ) and ( z ) are fitting parameters. For two-point extrapolation between calculations with cardinal numbers ( n ) and ( m ) (where ( m = n+1 )), this leads to the practical formula [4]:

[ E{\text{SCF}}(\text{CBS}) = \frac{E{\text{SCF}}(n) e^{-zn} - E_{\text{SCF}}(m) e^{-zm}}{e^{-zn} - e^{-zm}} ]

For cc-pVnZ basis sets, optimized parameters have been determined, such as ( z = 5.4 ) for n=3/m=4 extrapolations [4].

Correlation Energy Extrapolation

The correlation energy component converges differently, typically following an inverse power law with respect to the cardinal number n. A common expression is [4] [6]:

[ E{\text{corr}}(n) = E{\text{corr}}(\text{CBS}) + B n^{-y} ]

where ( E_{\text{corr}}(\text{CBS}) ) is the CBS limit correlation energy, and ( B ) and ( y ) are fitting parameters. For two-point extrapolation, this becomes [4]:

[ E{\text{corr}}(\text{CBS}) = \frac{E{\text{corr}}(n) n^{-y} - E_{\text{corr}}(m) m^{-y}}{n^{-y} - m^{-y}} ]

For the cc-pVnZ basis set family, an optimum value of ( y = 3.05 ) has been found for 3/4 extrapolation [4]. Alternative forms include exponential and mixed Gaussian/exponential functions, with the choice depending on the specific method and basis sets employed [6].

Workflow for Complete Basis Set Extrapolation

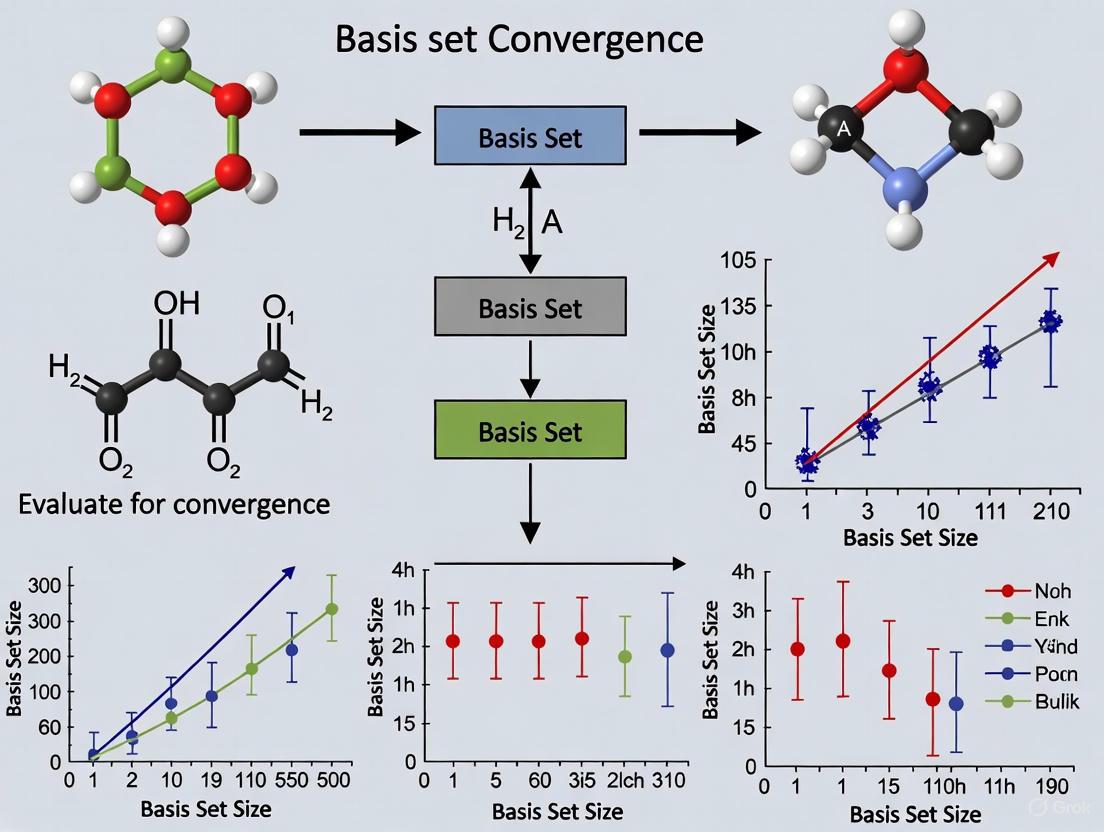

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for performing CBS extrapolation in quantum chemical calculations:

Figure 1: Complete Basis Set Extrapolation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process for obtaining CBS limit energies through extrapolation, from initial geometry optimization to the final combined CBS energy.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Convergence Behavior of Different Methods

The effectiveness of CBS extrapolation varies significantly across different quantum chemical methods. The following table compares the performance and characteristics of CBS extrapolation for selected methods:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CBS Extrapolation for Quantum Chemical Methods

| Method | Cost Scaling | Extrapolation Efficiency | Typical Accuracy | Recommended Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/SCF | N^3-N^4 | High - Exponential convergence | 0.1-1 mHa | Exponential: E(n)=E_CBS+Ae^(-zn) [4] |

| MP2 | N^5 | High - Systematic correlation convergence | 0.1-0.5 mHa | Inverse power: E(n)=E_CBS+Bn^-3 [4] [6] |

| CCSD(T) | N^7 | High - Well-behaved convergence | 0.01-0.1 mHa | Separate SCF/Correlation extrapolation [4] |

| DFT | N^3-N^4 | Moderate - Depends on functional | 0.5-2 mHa | Specialized schemes or direct large basis |

Quantitative Comparison of Extrapolation Schemes

Different mathematical forms for CBS extrapolation yield varying results depending on the basis sets employed. The table below compares total energies for a water molecule at the CCSD(T) level using different extrapolation approaches:

Table 2: Water Molecule CCSD(T) Energies (Hartree) with Different Basis Set Combinations [4]

| Basis Set Combination | Extrapolation Scheme | Total Energy (Hartree) | Deviation from CBS (mHa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cc-pVDZ | None (direct calculation) | -76.241204592 | ~135.0 |

| cc-pVTZ | None (direct calculation) | -76.332050910 | ~44.2 |

| cc-pVQZ | None (direct calculation) | -76.359580863 | ~16.6 |

| cc-pV5Z | None (direct calculation) | -76.368829406 | ~7.4 |

| cc-pVTZ/QZ | Two-point (y=3.05) | -76.3760523 | ~0.0 (reference) |

| cc-pVQZ/5Z | Two-point (y=3.05) | -76.3761 (estimated) | ~0.05 |

The data demonstrates that CBS extrapolation using moderate-sized basis sets (TZ/QZ) can achieve accuracy comparable to or better than direct calculation with much larger basis sets (5Z), at substantially reduced computational cost.

Domain-Based Localized Methods for Large Systems

For larger molecular systems where conventional CCSD(T) becomes prohibitively expensive, local correlation methods such as Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital (DLPNO)-CCSD(T) offer a scalable alternative while maintaining compatibility with CBS extrapolation [4]. Comparative data for water molecule calculations shows:

- Canonical CCSD(T)/CBS energy: -76.3760523 Hartree

- DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS energy: -76.375890 Hartree

- Difference: 0.000162 Hartree (0.1 mHa)

This remarkable agreement demonstrates that DLPNO methods combined with CBS extrapolation can provide near-CCSD(T) quality results for systems where canonical calculations are infeasible [4].

Implementation in Computational Chemistry Software

Automated CBS Methods in Popular Packages

Modern quantum chemistry packages have implemented sophisticated, automated CBS extrapolation capabilities:

PSI4 features a comprehensive CBS framework accessible through both concise and detailed input syntax [7]. Examples include:

energy('mp2/cc-pv[dt]z')for simple MP2 DT extrapolationoptimize('mp2/cc-pv[tq]z + d:ccsd(t)/cc-pvdz')for composite methods with counterpoise correction

ORCA provides dedicated keywords for CBS extrapolation, such as ! METHOD EXTRAPOLATE(n/n+1,cc) which automates the process of performing calculations with consecutive basis sets and extrapolating to the CBS limit [5].

Specialized Tools and Calculators

Dedicated CBS extrapolation calculators are available online, implementing multiple mathematical schemes including exponential, power function, mixed Gaussian/exponential, and inverse power approaches [6]. These tools facilitate parameter determination and can handle various basis set families and cardinal number combinations.

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Drug Development Research

Role in Accurate Energetics for Molecular Interactions

While quantum chemical calculations might seem distant from practical drug development, CBS-accurate methods provide the fundamental reference data critical for:

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Accurate intermolecular interaction energies for protein-ligand complexes

- Reaction Mechanism Elucidation: Precise activation barriers for enzyme-catalyzed reactions

- Solvation Modeling: Reliable solute-solvent interaction energies

- pKa Prediction: Accurate proton affinities and deprotonation energies

The demanding accuracy requirements of drug design (often < 1 kcal/mol for meaningful predictions) necessitates methods that approach chemical accuracy, which is precisely the target of CBS extrapolation techniques [2].

Emerging Integration with Quantum Computing

Recent advances propose embedding quantum computing ansatzes into density-functional theory via density-based basis-set corrections (DBBSC) to approach the CBS limit with minimal quantum resources [2]. This integration is particularly promising for pharmaceutical applications involving:

- Large Molecular Systems: Beyond the capacity of classical computation at high accuracy

- Transition Metal Complexes: Important for metalloenzyme drug targets

- Non-Covalent Interactions: Critical for protein-ligand binding

This approach demonstrates that reaching chemical accuracy for molecules that would otherwise require hundreds of logical qubits is feasible by accelerating basis-set convergence [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Complete Basis Set Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets | Systematic basis sets designed for CBS extrapolation | cc-pVnZ, aug-cc-pVnZ, cc-pCVnZ (core-valence) [3] |

| CBS Extrapolation Calculators | Automated parameter determination and limit estimation | Online CBS calculators [6], PSI4 [7], ORCA [4] [5] |

| Composite Energy Methods | Multi-level schemes combining different theoretical levels | CBS-APNO, G3, G4, W1, W2 theory |

| Local Correlation Methods | Scalable electron correlation for larger systems | DLPNO-CCSD(T) [4], local MP2 |

| Reference Data Sets | Benchmarking and validation of new methods | S22, S66, non-covalent interaction databases |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Implementation of CBS extrapolation protocols | PSI4 [7], ORCA [5], Gaussian, CFOUR |

The pursuit of the complete basis set limit represents a fundamental endeavor in theoretical chemistry to achieve results untainted by basis set truncation error. Through systematic extrapolation techniques employing correlation-consistent basis sets, computational chemists can now approach this limit at a fraction of the computational cost of direct calculation with massive basis sets. The critical importance of these methods extends from fundamental studies of molecular structure and reactivity to practical applications in pharmaceutical research and drug design, where quantitative prediction of molecular interactions demands the highest achievable accuracy. As computational methodologies continue to evolve, particularly with the emergence of quantum computing and advanced density-based correction schemes, the principles of CBS extrapolation will remain essential for extracting maximum accuracy from limited computational resources.

In quantum chemical calculations, the wave function of a molecule is typically constructed as a linear combination of one-electron functions known as atomic orbitals. However, since the exact forms of these orbitals are unknown for many-electron systems, they are approximated using mathematical functions, most commonly Gaussian-type orbitals. A basis set is a collection of these functions used to describe the electronic structure of atoms and molecules. The choice of basis set profoundly impacts both the accuracy and computational cost of quantum chemistry calculations, making the selection of an appropriate basis set a critical consideration in computational chemistry research and drug development.

Two systematically constructed basis set families have emerged as particularly important for high-accuracy calculations: the correlation-consistent (cc) basis sets pioneered by Dunning and coworkers, and the polarization-consistent (pc) basis sets developed by Jensen. These families are designed with different philosophical approaches and optimization criteria, leading to distinct performance characteristics across various chemical applications. The correlation-consistent sets are primarily energy-optimized and generally contracted for functions describing occupied orbitals, making them particularly suitable for correlated wavefunction methods. The polarization-consistent sets were initially developed for density functional theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock calculations but have since been extended to correlated methods. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two systematic basis set families, focusing on their convergence behavior, performance across different chemical properties, and appropriateness for specific research applications in computational chemistry and drug development.

Basis Set Philosophy and Design Principles

Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets

The correlation-consistent basis sets follow a well-defined design philosophy centered on systematic convergence toward the complete basis set (CBS) limit. These basis sets are energy-optimized, meaning they are not fitted to experimental data but rather designed to recover correlation energy efficiently. They employ a general contraction scheme for the functions describing the occupied orbitals in the Hartree-Fock wavefunction and are based on spherical harmonics rather than Cartesian functions [8]. This family is highly modular, allowing additional functions to be added to address specific chemical problems.

The naming convention follows a logical pattern: cc-pVnZ denotes "correlation-consistent polarized valence n-zeta" basis sets, where n represents the cardinal number (D=2, T=3, Q=4, 5, 6). Various augmented versions exist for specialized applications: aug-cc-pVnZ adds diffuse functions for electron affinities and intermolecular interactions; cc-pCVnZ includes core-valence functions for correlating core electrons; and cc-pV(n+d)Z incorporates tight d functions crucial for second-row elements (Al-Ar) [8] [9]. The systematic construction of these basis sets enables the use of extrapolation techniques to estimate the CBS limit, which is particularly valuable for high-accuracy thermochemical calculations.

Polarization-Consistent Basis Sets

The polarization-consistent basis sets were developed with a different optimization strategy, initially focusing on DFT and Hartree-Fock calculations. While correlation-consistent sets are optimized to recover correlation energy, polarization-consistent sets are designed to describe the polarization of the atomic orbitals in a molecular environment effectively. These basis sets have been extended to various specialized versions: pc-n and aug-pc-n for general applications, pcS-n for nuclear magnetic shielding tensors, and pcJ-n for indirect spin-spin coupling constants in NMR spectroscopy [10].

Unlike the generally contracted correlation-consistent sets, segmented polarization-consistent basis sets (pcs-n) have also been developed, which may offer computational advantages in certain electronic structure codes. These segmented sets have demonstrated excellent performance for molecular structures, rotational constants, and vibrational spectroscopic properties when combined with density functionals like B3LYP and B2PLYP [11]. The polarization-consistent family typically shows faster initial convergence for molecular properties compared to correlation-consistent sets, though both families ultimately converge to the same CBS limit.

Performance Comparison Across Chemical Applications

Convergence of Energetic Properties

Table 1: Performance of Basis Sets for Water Dimer Interaction Energy at CCSD(T) Level

| Basis Set Family | Raw Interaction Energy (kcal/mol) | Deviation from Reference | CP-Corrected Energy (kcal/mol) | Deviation from Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aug-cc-pVXZ | -4.845 | 0.136 | -4.980 | 0.001 |

| pc-n | -4.845 | 0.136 | -4.969 | 0.012 |

| Reference Value | -4.98065 | - | -4.98065 | - |

Data adapted from [12]

The performance of basis sets for predicting interaction energies in non-covalent complexes represents a critical test of their completeness and balance. As shown in Table 1, both correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent basis sets underestimate the raw interaction energy of the water dimer by 0.136 kcal/mol with respect to the reference value of -4.98065 kcal/mol at the CCSD(T) level [12]. The application of counterpoise (CP) correction to account for basis set superposition error (BSSE) significantly improves the results for both families. The CP-corrected interaction energy obtained with Dunning's aug-cc-pVXZ sets shows exceptional agreement with the reference value (deviation of 0.001 kcal/mol), while Jensen's polarization-consistent basis sets perform slightly worse (deviation of 0.012 kcal/mol) [12].

For total energies and extrapolation to the complete basis set limit, separate fitting of Hartree-Fock and correlation energies using a three-parameter exponential formula provides the most accurate results. The Hartree-Fock component typically converges exponentially with the cardinal number, while the correlation energy converges more slowly, following an inverse power law [12]. The CBS limit can be approached through systematic basis set extension or using specialized correction schemes like the density-based basis-set correction (DBBSC) method, which has shown promise in accelerating convergence while minimizing quantum resources in quantum computing applications [2].

Molecular Properties and Spectroscopic Constants

Table 2: Performance for Molecular Structures and Spectroscopic Properties

| Property | Method | cc-pVnZ Performance | pc-n Performance | Recommended Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Geometries | B3LYP, B2PLYP | Good | Comparable to cc-pVnZ | pcs-2 or aug-pcs-2 |

| Rotational Constants | B3LYP, B2PLYP | Good | Excellent | pcs-2 or aug-pcs-2 |

| Centrifugal Distortion | B3LYP, B2PLYP | Satisfactory | Good | pcs-2 or aug-pcs-2 |

| Harmonic Frequencies | B3LYP, B2PLYP | Good | Comparable to cc-pVnZ | pcs-2 or aug-pcs-2 |

| Anharmonic Frequencies | B3LYP, B2PLYP | Satisfactory | Good | pcs-2 or aug-pcs-2 |

| NMR Shielding Constants | B3LYP | Slow convergence | Faster convergence | pcS-2 or pcS-3 |

| Spin-Spin Coupling Constants | B3LYP | Irregular convergence | Smooth convergence | pcJ-2 or pcJ-3 |

For predicting molecular structures and spectroscopic properties, both basis set families demonstrate excellent performance when paired with appropriate density functionals. The segmentation of polarization-consistent basis sets (pcs-n) shows particular promise for spectroscopic applications, with the pcs-2 and aug-pcs-2 sets providing an optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost for equilibrium geometries, rotational constants, and vibrational frequencies [11]. The performance of these basis sets with double-hybrid functionals like B2PLYP is notably impressive, often rivaling the accuracy of more computationally expensive coupled-cluster calculations with triple-zeta basis sets.

For NMR parameters, polarization-consistent basis sets specifically designed for property calculations (pcS-n and pcJ-n) demonstrate superior convergence behavior compared to standard correlation-consistent sets. The pcJ-n sets show particularly smooth convergence for spin-spin coupling constants, while correlation-consistent sets often exhibit irregular convergence patterns that require careful selection of data points for CBS extrapolation [10]. This makes polarization-consistent sets particularly valuable for computational NMR spectroscopy in drug development applications where accurate prediction of spectroscopic parameters is essential for structure elucidation.

Electronic Properties and Response Functions

The accurate computation of frequency-dependent polarizabilities represents a challenging test for basis sets due to the need to describe both ground and response states accurately. Correlation-consistent basis sets augmented with diffuse functions (aug-cc-pVnZ and d-aug-cc-pVnZ) are essential for obtaining quantitatively accurate polarizabilities, with the doubly-augmented sets providing significant improvements for systems with diffuse electron densities [13]. Benchmark studies against reference values obtained using multiresolution analysis (MRA) show that augmented correlation-consistent basis sets systematically converge toward the CBS limit for this property, though the convergence rate depends on the elemental composition and bonding pattern of the molecule [13].

The use of core-polarization functions (cc-pCVnZ) generally has a minimal effect on polarizability calculations, as this property is primarily determined by the valence electrons. However, for high-oxidation-state compounds involving second-row elements, the inclusion of tight d functions in the cc-pV(n+d)Z basis sets is crucial for accurate results [9]. The polarization-consistent basis sets also demonstrate good performance for electronic properties, though comprehensive benchmarking against MRA reference data is less extensive compared to correlation-consistent sets.

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Complete Basis Set Extrapolation Techniques

The systematic construction of both correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent basis sets enables the use of mathematical extrapolation to estimate the complete basis set limit, which is essential for achieving high accuracy in quantum chemical calculations. The most common extrapolation schemes include:

- Exponential Formula: ( Y(X) = Y(\infty) + B \times \exp(-C/X) ) - Particularly suitable for Hartree-Fock energies [12]

- Inverse Power Formula: ( Y(X) = Y(\infty) + B/X^3 ) - Recommended for correlation energy components [12]

- Mixed Schemes: Separate extrapolation of Hartree-Fock and correlation components using different formulas followed by summation

For the water dimer interaction energy at the CCSD(T) level, separate fits of Hartree-Fock and correlation interaction energies using a three-parameter exponential formula provide the most accurate results, with the smallest CBS deviation from the reference value being about 0.001 kcal/mol for aug-cc-pVXZ calculations [12]. The two-parameter inverse-power fit also performs well and requires fewer data points, making it computationally more efficient.

Counterpoise Correction for Non-Covalent Interactions

The accurate computation of interaction energies for weakly bound complexes requires careful treatment of basis set superposition error (BSSE), which arises from the artificial lowering of energy due to the use of incomplete basis sets. The standard approach for correcting BSSE is the counterpoise (CP) correction proposed by Boys and Bernardi [12]. The protocol involves:

- Calculation of the energy of monomer A in the full dimer basis set

- Calculation of the energy of monomer B in the full dimer basis set

- Computation of the interaction energy as: ( \Delta E{CP} = E{AB}^{AB} - E{A}^{AB} - E{B}^{AB} )

For the water dimer, CP-corrected interaction energies show improved agreement with reference values compared to raw interaction energies for both correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent basis sets [12]. The impact of BSSE diminishes systematically with increasing basis set size, becoming negligible in the CBS limit.

Diagram 1: Basis set selection workflow for quantum chemical calculations, showing the decision process for choosing between correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent families based on computational method and target properties.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Computational Resources for Basis Set Applications

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Codes | Gaussian, Dalton, NWChem, Quantum Package 2.0 | Perform electronic structure calculations | Commercial and academic licenses |

| Basis Set Repositories | EMSL Basis Set Exchange, Basis Set Library | Provide basis sets in standardized formats | https://www.basissetexchange.org/ |

| Extrapolation Tools | Custom scripts, CBS-1, CBS-QB3 | Implement CBS extrapolation formulas | Built into major packages or custom |

| Reference Data | ATcT, NIST databases, MRA benchmarks | Provide benchmark values for validation | Public databases and literature |

| Visualization Software | GaussView, Avogadro, Molden | Analyze molecular structures and properties | Various licensing models |

The effective application of systematic basis set families requires access to specialized computational resources and reference data. The EMSL Basis Set Exchange represents a particularly valuable resource, providing comprehensive collections of both correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent basis sets in standardized formats compatible with most quantum chemistry packages [10]. For high-accuracy thermochemical calculations, the Active Thermochemical Tables (ATcT) provide reference data with exceptionally low error bars, enabling rigorous benchmarking of computational procedures [14].

When implementing CBS extrapolations, careful attention must be paid to the selection of appropriate mathematical formulas and the exclusion of potentially problematic data points. For NMR properties, the smallest basis sets in each family (cc-pVDZ and pc-0) often show significant deviations from the convergence trend and should be excluded from CBS fits [10]. Similarly, for interaction energies, separate extrapolation of Hartree-Fock and correlation components typically provides more accurate results than combined extrapolation of total energies.

Both correlation-consistent and polarization-consistent basis sets provide systematic pathways to the complete basis set limit, but their optimal application depends on the specific computational context and target properties. Correlation-consistent basis sets generally show superior performance for high-accuracy wavefunction methods like CCSD(T), particularly for energetic properties and non-covalent interactions when properly extrapolated to the CBS limit. The availability of specialized augmented sets makes them particularly valuable for properties requiring a good description of diffuse electron densities.

Polarization-consistent basis sets demonstrate excellent performance for density functional theory calculations and typically show faster convergence for molecular properties, including geometrical parameters, spectroscopic constants, and NMR parameters. The specialized pcS-n and pcJ-n sets are particularly recommended for computational NMR spectroscopy, while the segmented pcs-n sets offer an attractive balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for routine spectroscopic applications.

For researchers in drug development and medicinal chemistry, the selection between these basis set families should be guided by the primary computational methods employed and the specific properties of interest. For DFT-based studies of molecular structure and spectra, polarization-consistent sets provide excellent performance with moderate computational requirements. For highest-accuracy energetics of non-covalent interactions relevant to drug-receptor binding, correlation-consistent sets with CBS extrapolation remain the gold standard. Both families continue to evolve with new specialized versions and extensions, further expanding their utility across the diverse landscape of quantum chemical applications.

The Impact of Basis Set Incompleteness on Energy and Molecular Properties

Basis set incompleteness is a fundamental source of error in quantum chemical calculations, directly impacting the accuracy of computed energies and molecular properties. This error arises when the finite set of basis functions used to expand molecular orbitals provides an inadequate description of the true electron wavefunction. The choice of basis set represents a critical compromise between computational cost and accuracy, particularly for researchers studying large systems such as drug molecules.

This guide provides an objective comparison of basis set performance, examining how different basis sets manage the trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy across various chemical properties. We present experimental data from recent studies to illustrate the tangible effects of basis set incompleteness and the strategies employed to mitigate them, providing a practical framework for selecting appropriate basis sets in research applications.

Understanding Basis Set Incompleteness and Error Manifestation

Basis set incompleteness error (BSIE) occurs when a limited basis set cannot fully represent the electron density, particularly in regions close to the nucleus and at long ranges. This deficiency systematically affects computed molecular properties. A related phenomenon, basis set superposition error (BSSE), artificially lowers interaction energies as fragments in molecular complexes "borrow" basis functions from adjacent atoms [15] [16].

The severity of BSIE depends heavily on basis set construction. Minimal basis sets (single-ζ) contain only one basis function per atomic orbital, while double-ζ (DZ) and triple-ζ (TZ) basis sets provide two and three functions per orbital respectively, offering progressively better flexibility to describe electron distribution. The inclusion of polarization functions (adding angular momentum quantum numbers) describes orbital deformation during bond formation, while diffuse functions (with small exponents) better capture long-range electron behavior important for anions and weak interactions [16].

Conventional wisdom suggests that triple-ζ basis sets represent the minimum for high-quality energy calculations, as double-ζ basis sets often retain substantial BSIE and BSSE even with counterpoise corrections [15]. However, this guidance must be balanced against computational reality: increasing basis set size from double-ζ to triple-ζ can increase calculation runtimes more than five-fold, creating significant practical constraints for large systems [16].

Comparative Performance of Basis Sets

Quantitative Assessment of Thermochemical Accuracy

The GMTKN55 database, encompassing 55 benchmark sets of main-group thermochemistry, provides a comprehensive standard for evaluating quantum chemical methods. Recent research has quantified the performance of various basis sets across this diverse chemical space, with results summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Weighted Total Mean Absolute Deviations (WTMAD2) for Various Functionals and Basis Sets on GMTKN55 [16]

| Functional | Basis Set | WTMAD2 | Basic Properties | Barrier Heights | Non-Covalent Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-D3BJ | def2-QZVP | 8.42 | 5.43 | 13.13 | 5.11–8.60 |

| B97-D3BJ | vDZP | 9.56 | 7.70 | 13.25 | 7.27–8.60 |

| r2SCAN-D4 | def2-QZVP | 7.45 | 5.23 | 14.27 | 5.74–6.84 |

| r2SCAN-D4 | vDZP | 8.34 | 7.28 | 13.04 | 8.91–9.02 |

| B3LYP-D4 | def2-QZVP | 6.42 | 4.39 | 9.07 | 5.19–6.18 |

| B3LYP-D4 | vDZP | 7.87 | 6.20 | 9.09 | 7.88–8.21 |

| M06-2X | def2-QZVP | 5.68 | 2.61 | 4.97 | 4.44–11.10 |

| M06-2X | vDZP | 7.13 | 4.45 | 4.68 | 8.45–10.53 |

The data reveals that the vDZP basis set maintains competitive accuracy across multiple functionals compared to the much larger def2-QZVP basis. While the quadruple-ζ reference consistently delivers superior performance, the vDZP basis achieves this at a substantially reduced computational cost, with the performance gap being remarkably small for certain functionals like M06-2X for barrier heights.

Specialized Property Requirements

Different molecular properties exhibit distinct basis set convergence behaviors, necessitating specialized basis sets for optimal performance:

Optical Rotation Calculations: For chiroptical properties like optical rotation, which are crucial for determining absolute configurations of chiral molecules, the inclusion of diffuse functions is essential for achieving origin-independent results. Studies show that the augmented ADZP basis set provides the smallest deviation from complete basis set limit estimates for GIAO-B3LYP calculations of specific rotations [17].

Core-Dependent Properties: Magnetic properties including J-coupling constants, hyperfine coupling constants, and chemical shifts (derived from magnetic shielding constants) require specialized core-optimized basis sets. These properties demand basis functions with high exponents to accurately capture core electron behavior and decontracted basis functions for wavefunction flexibility. Research demonstrates significant error reduction when using purpose-built basis sets (pcJ-1, EPR-II, pcSseg-1) compared to general-purpose basis sets like 6-31G, often with only marginal computational cost increases [18].

Excited-State Properties: For excited-state calculations using methods such as GW and Bethe-Salpeter equation, newly developed augmented MOLOPT basis sets achieve rapid convergence of excitation energies and band gaps while maintaining numerical stability through low condition numbers of the overlap matrix. The double-zeta augmented MOLOPT basis yields a mean absolute deviation of just 60 meV for GW HOMO-LUMO gaps compared to the complete basis set limit [19].

Experimental Protocols for Basis Set Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Methodologies

The quantitative comparisons presented in this guide are derived from rigorous benchmarking protocols established in computational chemistry:

Table 2: Common Benchmark Sets for Evaluating Basis Set Performance

| Benchmark Set | Chemical Properties Assessed | System Size | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMTKN55 | Main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, non-covalent interactions | Small to medium molecules | (aug)-def2-QZVP or CCSD(T) |

| ROT34 | Conformational energies | Flexible molecules with 4-13 atoms | Higher-level theory |

| S66 | Non-covalent interactions | 66 dimer complexes | CCSD(T)/CBS |

The GMTKN55 protocol involves single-point energy calculations on geometries optimized at the PBEh-3c/def2-mSVP level, with energies evaluated using various functional/basis set combinations. The overall accuracy is summarized through the weighted total mean absolute deviation (WTMAD2), which aggregates errors across all 55 subsets with appropriate weighting based on chemical importance [16].

For optical rotation benchmarks, calculations typically employ gauge-invariant atomic orbitals (GIAO) to ensure origin independence, with specific rotations computed at the sodium D-line wavelength. Geometries are generally optimized at the B3LYP/6-311G level, with property calculations using progressively larger augmented basis sets (ADZP, ATZP, AQZP) to extrapolate to the complete basis set limit [17].

Workflow for Basis Set Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic decision process for selecting appropriate basis sets based on target properties and computational constraints:

This workflow emphasizes that the optimal basis set choice depends significantly on the specific chemical property of interest, with specialized basis sets often providing superior performance for core-dependent and response properties compared to general-purpose alternatives.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Basis Set Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Basis Set Applications

| Basis Set | Type | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| vDZP | Double-ζ | General purpose thermochemistry | Minimized BSSE, deeply contracted valence functions, effective core potentials [16] |

| def2-TZVP | Triple-ζ | High-accuracy energy calculations | Balanced performance for diverse properties, good convergence to CBS limit [15] |

| aug-cc-pVXZ | Augmented correlation-consistent | Response properties, anions, weak interactions | Systematic hierarchy (X=D,T,Q), diffuse functions, CBS extrapolation [17] |

| pcSseg-1/2 | Core-specialized | Magnetic shielding constants | High exponents, decontracted functions for core flexibility [18] |

| EPR-II/III | Radical-specialized | Hyperfine coupling constants | Optimized for radical systems, core-valence balance [18] |

| pcJ-1/2 | Coupling-optimized | J-coupling constants | Tailored for NMR spin-spin coupling [18] |

| aug-MOLOPT | Excited-state optimized | GW/BSE calculations | Low condition numbers, rapid convergence for excitation energies [19] |

Basis set incompleteness remains a fundamental consideration in quantum chemical calculations, with its impact varying significantly across different molecular properties. While general-purpose triple-ζ basis sets provide robust performance for energy-related properties, specialized basis sets offer distinct advantages for specific applications including optical activity, magnetic properties, and excited states.

The development of modern double-ζ basis sets like vDZP demonstrates that careful optimization can achieve accuracy approaching triple-ζ quality at substantially reduced computational cost. For researchers studying large systems such as drug molecules, these efficient basis sets enable the application of high-level theory to biologically relevant systems while maintaining acceptable accuracy. The continuing evolution of property-specific basis sets promises further improvements in the efficiency and reliability of computational chemistry across diverse research applications.

Identifying and Quantifying Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE)

Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) is a fundamental computational artifact encountered in quantum chemical calculations of molecular interactions using incomplete basis sets. This error arises when calculating the interaction energy between molecular fragments (a molecule A and a molecule B) according to the supermolecular method: ΔE = E(AB) - E(A) - E(B), where E(AB) is the energy of the complex, and E(A) and E(B) are the energies of the isolated monomers [20]. The core issue stems from the finite size of the atomic orbital basis sets used in practical computations. When fragments A and B are calculated in isolation, each uses only its own basis functions. However, in the complex AB, each fragment can "borrow" or "use" the basis functions of the other fragment to achieve a lower, more favorable energy state. This artificial lowering of the complex's energy leads to an overestimation of the binding energy [21] [20].

The significance of BSSE correction extends across multiple domains of computational chemistry, particularly in the accurate prediction of intermolecular interaction energies, which are crucial for understanding molecular recognition in drug design, supramolecular chemistry, and materials science. Without proper correction, BSSE can lead to qualitatively wrong conclusions about binding affinity and molecular stability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of methodologies for identifying and quantifying BSSE, supported by experimental data and practical protocols.

Theoretical Foundation and the Counterpoise (CP) Method

The most widely adopted technique for correcting BSSE is the Counterpoise (CP) method, introduced by Boys and Bernardi [20]. The CP method provides a systematic approach to estimate and subtract the BSSE from the computed interaction energy. The fundamental insight of this method is that the energy of each isolated monomer should be calculated using the full basis set of the complex to provide a fair comparison.

The BSSE is quantified by the following equation [20]: EBSSE = EA(A) - EA(AB) + EB(B) - E_B(AB)

Here:

- E_A(A) is the energy of monomer A computed with only its own basis set.

- E_A(AB) is the energy of monomer A computed with the full basis set of the complex AB (i.e., its own basis functions plus the basis functions of monomer B, the latter acting as "ghost" orbitals without atoms or electrons).

- The terms for monomer B are defined analogously.

The CP-corrected interaction energy is then calculated as [20]: ΔECP = EAB(AB) - EAB(A) - EAB(B)

In this formulation, all three energies—EAB(AB), EAB(A), and EAB(B)—are computed using the full, combined basis set of the complex AB. The terms EAB(A) and E_AB(B) represent the energies of the isolated monomers A and B, respectively, each calculated in the geometry they adopt within the complex but with the full superset of basis functions available.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a standard Counterpoise correction calculation:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Counterpoise (CP) Correction. The process involves calculating the energy of the complex and each monomer using the full basis set of the complex, with ghost atoms used for monomer calculations.

Comparative Analysis of BSSE Correction Methodologies

This section objectively compares the primary strategies for mitigating BSSE, evaluating their performance, computational cost, and suitability for different research scenarios.

The Counterpoise Method in Practice

The CP method is directly implemented in major computational chemistry packages. For example, in the ADF software, the process involves creating ghost atoms with zero mass and nuclear charge but possessing their normal basis functions [21]. The required steps are:

- Fragment Definition: The complex is defined as composed of fragments A and B.

- Ghost Basis Generation: For each atom involved, basis set files are copied and modified to remove the frozen core.

- Single-Point Calculations: The bonding energy of a pseudo-molecule composed of A plus a ghost B, and vice versa, is calculated to determine the BSSE [21].

The efficacy of CP correction is highly dependent on the choice of basis set. Systematic evaluations suggest that CP correction is mandatory for reliable results with double-ζ basis sets. For triple-ζ basis sets lacking diffuse functions, the correction remains beneficial. However, with larger quadruple-ζ basis sets, the influence of BSSE and thus the CP correction becomes negligible [20].

Basis Set Extrapolation to the Complete Basis Set (CBS) Limit

An alternative to the CP method is basis set extrapolation, a strategy that aims to approximate the energy at the Complete Basis Set (CBS) limit, where BSSE would be absent. This approach is particularly valuable for wavefunction-based methods like Coupled-Cluster theory but is also applicable in Density Functional Theory (DFT) [20].

A common extrapolation formula for the Hartree-Fock (HF) and DFT energies is the exponential-square-root (expsqrt) function [20]: EX^∞ = EX - A · exp(-αX)

Here, ( EX^∞ ) is the estimated CBS limit energy, ( EX ) is the energy computed with a basis set of cardinal number X (e.g., 2 for double-ζ, 3 for triple-ζ), and A and α are parameters. A key advantage is that with a pre-optimized α parameter, only two energy points (e.g., from def2-SVP and def2-TZVPP basis sets) are needed for accurate extrapolation [20].

Recent research on supramolecular systems has demonstrated that an optimized basis set extrapolation scheme can achieve accuracy comparable to CP-corrected calculations with very large basis sets, but at a significantly reduced computational cost [20].

Direct Comparison of Method Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Primary BSSE Mitigation Strategies

| Method | Underlying Principle | Computational Cost | Best-Suited Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Counterpoise (CP) | Calculates monomers using the full complex basis set to isolate BSSE [20]. | Moderate (requires 3-5 additional single-point calculations per complex). | Routine DFT calculations with double- or triple-ζ basis sets; benchmarking studies [20]. | Can over-correct in wavefunction methods; controversy over application to geometry optimization [20]. |

| Basis Set Extrapolation | Uses a mathematical model to estimate the energy at the infinite (complete) basis set limit [20]. | Low to Moderate (requires 2-3 calculations with different basis sets and extrapolation). | High-accuracy post-HF methods (CCSD(T)); DFT for supramolecular systems; when CBS limit is desired [20]. | Extrapolation parameters (e.g., α=5.674 for B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2) may be functional-dependent [20]. |

| Using Very Large Basis Sets | Reduces BSSE to negligible levels by minimizing basis set incompleteness. | Very High (often prohibitively expensive for large systems). | Final, high-accuracy single-point energy calculations on pre-optimized geometries of small complexes. | Computationally intractable for systems >200 atoms; inclusion of diffuse functions can cause SCF convergence issues [20]. |

Table 2: Performance of B3LYP-D3(BJ) with Different BSSE Treatments on Weak Interaction Energies (Mean Absolute Error, kcal/mol)

| BSSE Treatment | Basis Set(s) Used | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected | def2-SVP | >2.0 (estimated) | Significant error, unreliable for quantitative work [20]. |

| CP-Corrected | ma-TZVPP | 0.24 | Considered a robust reference in this study [20]. |

| Extrapolated (α=5.674) | def2-SVP & def2-TZVPP | 0.25 | Accuracy matches CP-corrected large-basis calculation at lower cost [20]. |

The data in Table 2, derived from a benchmark study of 57 weakly interacting complexes, highlights that an optimized extrapolation scheme can be as accurate as a high-level CP-corrected calculation. This provides a powerful and efficient alternative for large-scale DFT studies [20].

Experimental Protocols for BSSE Quantification

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step guide for researchers to implement these methodologies in their computational workflows.

Standard Protocol for Counterpoise Correction

The following protocol is recommended for a robust CP-corrected interaction energy calculation using a typical quantum chemistry package.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the complex AB at your chosen level of theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP). It is common practice to use a modest basis set for geometry optimization due to computational cost, followed by a higher-level single-point energy calculation.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation on the Complex: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized complex AB using a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVPP) to obtain E_AB(AB).

- Generate Inputs for Monomers in Complex Geometry: Extract the coordinates of monomer A and monomer B directly from the optimized complex AB. Do not re-optimize the monomers individually, as this would break the supermolecular formalism.

- Single-Point Energy with Ghost Atoms:

- For monomer A, perform a single-point calculation at the same level of theory as in Step 2, but use the entire basis set of complex AB. This is typically done by specifying the atoms of fragment B as "ghost" atoms (zero charge, no electrons) that contribute their basis functions.

- Repeat this process for monomer B, specifying the atoms of fragment A as ghost atoms.

- These calculations yield EAB(A) and EAB(B).

- Calculate Interaction Energy and BSSE: Use the energies from Steps 2 and 4 to compute the CP-corrected interaction energy: ΔECP = EAB(AB) - EAB(A) - EAB(B). The raw BSSE can also be quantified as the difference between the uncorrected and CP-corrected interaction energies.

Protocol for Basis Set Extrapolation

For a two-point extrapolation to the CBS limit using the expsqrt formula:

- Geometry Selection: Use a pre-optimized geometry for the complex and its constituent monomers.

- Single-Point Calculations with Two Basis Sets: For the complex and each monomer, perform two separate single-point energy calculations:

- One with a smaller basis set (e.g., def2-SVP).

- One with a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVPP).

- Compute Interaction Energies: Calculate the uncorrected interaction energy, ΔE, for both basis sets: ΔESVP and ΔETZVPP.

- Apply Extrapolation Formula: Use the expsqrt formula with a pre-optimized parameter (e.g., α = 5.674 for B3LYP-D3(BJ)) to extrapolate the interaction energy from ΔESVP and ΔETZVPP to the CBS limit. This can be done by solving the two equations with two unknowns (E_X^∞ and A).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for BSSE Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in BSSE Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Counterpoise Procedure | Algorithmic Correction | The standard method for calculating the BSSE and obtaining corrected interaction energies [20]. |

| Dunning's cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5) | Basis Set Family | Correlation-consistent basis sets designed for systematic convergence to the CBS limit; central to extrapolation schemes [20]. |

| Ahlrichs' def2-SVP/TZVPP | Basis Set Family | Popular, efficient basis sets for preliminary scans and two-point extrapolation protocols [20]. |

| Minimally Augmented (ma-) Basis Sets | Basis Set Family | Basis sets like ma-TZVPP, which add a minimal set of diffuse functions to improve description of weak interactions without severe SCF issues [20]. |

| S22, S30L, CIM5 Benchmark Sets | Data Set | Curated databases of weakly interacting complexes with reference interaction energies for validating new methods and parameters [20]. |

| B3LYP-D3(BJ)/ωB97X-D | Density Functional | Example of modern DFT functionals empirically parameterized with dispersion corrections to accurately model weak intermolecular interactions. |

The identification and quantification of Basis Set Superposition Error is a critical step in achieving predictive accuracy in quantum chemical calculations of molecular interactions. This guide has compared the two dominant paradigms: the widely used Counterpoise correction and the increasingly robust basis set extrapolation techniques. The Counterpoise method remains the workhorse for routine applications, especially with medium-sized basis sets. However, evidence demonstrates that optimized basis set extrapolation, with parameters like α=5.674 for B3LYP-D3(BJ), can achieve reference-quality results more efficiently. The choice between methods ultimately depends on the system size, desired accuracy, and computational resources. For the practicing computational chemist engaged in drug development, a robust protocol involving CP-corrected energies with triple-ζ basis sets or a carefully validated extrapolation scheme is recommended for reporting reliable intermolecular interaction energies.

In computational chemistry, the accuracy of quantum chemical calculations depends on two fundamental approximations: the electronic structure method (e.g., Hartree-Fock, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T)) and the basis set used to represent molecular orbitals. A pervasive challenge arises from the phenomenon of fortuitous error cancellation, where errors from an incomplete method and errors from a limited basis set cancel each other, producing deceptively accurate results [3]. While this might appear beneficial initially, it undermines the transferability and predictive power of computational models, as the cancellation is not systematic and fails for molecular systems with different electronic characteristics [22] [3].

The core of the problem lies in the strongly coupled nature of these error sources. Apparent errors arising from a given method with a finite basis set can be much different than their intrinsic errors, which are obtained at the complete basis set (CBS) limit [3]. This coupling means that a combination of a low-level method with a small basis set can sometimes produce better agreement with experimental properties than more sophisticated, expensive combinations. This guide provides a systematic comparison of method/basis set combinations, presents experimental protocols for proper evaluation, and offers strategies to avoid the pitfalls of fortuitous error cancellation in research and development.

The Two Approximations in Quantum Chemistry

Every electronic structure calculation involves two primary expansions. First, the method approximation deals with how electron correlation is treated. Wavefunction-based methods like Hartree-Fock, MP2, and CCSD(T) represent a hierarchy of increasing accuracy and computational cost in capturing electron correlation. Density Functional Theory (DFT) employs various exchange-correlation functionals with different accuracy trade-offs [3]. Second, the basis set approximation involves representing molecular orbitals as linear combinations of basis functions, typically Gaussian-type orbitals. The incompleteness of this representation introduces basis set error [1].

The Mechanism of Error Cancellation

Error cancellation occurs when the inherent deficiencies of a particular method coincidentally compensate for the limitations imposed by a finite basis set. Mathematically, if a method captures interactions X, Y, and Z, but misses interaction A, while a basis set incompletely represents these interactions, the combined error may be small if (Method_Error + Basis_Error) ≈ 0, even though both errors are significant [22]. This cancellation is "fortuitous" because it depends on the specific chemical system and property being calculated and is not transferable across different molecular environments.

The problem becomes particularly evident when molecular systems involve different types of interactions. For example, if an approximate method correctly captures interactions X, Y, and Z, error cancellation may hold for systems dominated by these interactions but will fail for systems where an additional interaction A becomes significant [22]. This explains why method/basis set combinations that perform well for organic molecules may fail dramatically for transition metal complexes or systems with significant dispersion interactions.

Comparative Analysis of Method/Basis Set Performance

Systematic Basis Set Families and Their Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Major Basis Set Families and Their Properties

| Basis Set Family | Design Principle | Systematic Convergence | Optimal Use Case | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G, 6-311+G*) [1] | Split-valence with polarization/diffuse functions | Limited hierarchical progression | HF and DFT calculations on main-group elements; initial geometry optimizations | Less efficient for correlated methods; limited element coverage |

| Dunning's cc-pVnZ (n=D,T,Q,5,6) [1] [3] | Correlation-consistent for CBS extrapolation | Excellent systematic convergence | High-accuracy correlated methods (MP2, CCSD(T)); benchmark studies | Larger sets needed for chemical accuracy; computationally demanding |

| Ahlrichs def2- (SVP, TZVP, QZVP) [23] | Balanced polarized basis sets | Good for DFT methods | General-purpose DFT calculations across periodic table | Not optimized for systematic CBS extrapolation in correlated methods |

| Jensen's PC-n [3] | Polarization-consistent | Systematic for HF and DFT | DFT and HF calculations with controlled convergence | Less common than Dunning sets for correlated methods |

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Chemical Systems

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Method/Basis Set Combinations for Different Chemical Properties

| Method/Basis Set Combination | Organic Molecule Geometries (RMSD Å) | Redox Potential Prediction (RMSE V) | Transition Metal Complexes | Relative Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G* | 0.02-0.05 [23] | 0.07-0.10 (with solvation) [24] | Poor for many systems | 1x (reference) |

| B3LYP/def2-TZVP | 0.01-0.03 [23] | 0.05-0.08 (with solvation) [24] | Moderate accuracy | 3-5x |

| PBE/def2-TZVP | 0.02-0.04 | 0.06-0.09 (with solvation) [24] | Variable performance | 3-5x |

| MP2/cc-pVDZ | 0.02-0.05 | Not recommended [23] | Poor without correction | 10-20x |

| MP2/cc-pVTZ | 0.01-0.03 | Good with CBS extrapolation [23] | Moderate with core correlation | 50-100x |

| CCSD(T)/cc-pVQZ | ~0.005 (near CBS) [3] | Benchmark quality | Good with relativistic corrections | 1000x+ |

The data in Table 2 reveals several critical patterns. For DFT methods, adding polarization functions (e.g., 6-31G* vs. 6-31G) significantly improves accuracy with modest computational cost. For post-Hartree-Fock methods, the basis set requirement is more stringent - double-zeta basis sets like cc-pVDZ are generally insufficient, and triple-zeta or higher is recommended [23]. The prediction of redox potentials illustrates how method/basis set combinations perform for chemically relevant properties, with the best approaches achieving errors of 0.05-0.08 V compared to experiment [24].

Case Study: Redox Potential Prediction for Quinone-Based Electroactive Compounds

A systematic study on predicting redox potentials of quinones revealed how method and basis set choices impact accuracy [24]. The research compared DFT, DFTB, and semi-empirical methods with various basis sets, finding that geometry optimizations at lower levels of theory followed by single-point energy calculations at the DFT level with implicit solvation could achieve accuracy comparable to high-level DFT at significantly reduced computational cost.

Notably, this study found that including solvation effects through an implicit model during single-point energy calculations significantly improved redox potential predictions (reducing RMSE by 23-30% across functionals), while full geometry optimization in implicit solvation offered no real improvement over gas-phase optimized geometries [24]. This highlights the importance of strategic allocation of computational resources rather than uniformly applying the highest possible level of theory to all calculation steps.

Diagram 1: Computational workflow for redox potential prediction showing optimal path (green) identified through systematic comparison [24].

Protocols for Controlled Method/Basis Set Evaluation

Systematic Convergence Protocol for CBS Extrapolation

The most rigorous approach to avoid fortuitous error cancellation involves systematically converging both method and basis set toward their respective complete limits [3]. For the basis set, this requires using a family of correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVnZ) with increasing n (D, T, Q, 5, 6) and extrapolating to the CBS limit. For the method, one should employ a hierarchy such as HF → MP2 → CCSD → CCSD(T). The recommended protocol involves:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize molecular geometry at DFT level with polarized triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) [23]

- Single-Point Energy Hierarchy: Perform single-point calculations with cc-pVnZ basis sets (n = D, T, Q) at the target level of theory

- CBS Extrapolation: Apply appropriate extrapolation formulas (e.g., exponential or mixed exponential/Gaussian) to estimate CBS limit [3]

- Method Hierarchy: Compare results across method hierarchy (e.g., MP2, CCSD, CCSD(T)) at each basis set level

- Core-Correlation Evaluation: For highest accuracy, include core-valence correlation effects using cc-pCVnZ basis sets

This protocol ensures that method errors and basis set errors are separately characterized and minimized, rather than allowing their fortuitous cancellation.

Practical Protocol for Large-Scale Screening

For high-throughput screening where CBS extrapolation is computationally prohibitive, a balanced approach can minimize error cancellation while maintaining feasibility:

- Initial Geometry Optimization: Use DFT with polarized double-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) for initial structure sampling [23]

- Refined Geometry Optimization: Employ DFT with polarized triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) for final structures [23]

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Use target DFT functional with larger basis set including diffuse functions (e.g., 6-311+G) or apply composite method

- Implicit Solvation: Include solvation effects at single-point stage for solution-phase properties [24]

- Benchmarking: Validate approach against CBS-extrapolated results for representative molecular systems

This workflow was successfully applied in screening quinone-based electroactive compounds, where geometries optimized at lower levels of theory combined with single-point DFT calculations including implicit solvation provided the best trade-off between accuracy and computational cost [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Controlled Electronic Structure Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dunning's cc-pVnZ Basis Sets [1] [3] | Systematic convergence to CBS limit | High-accuracy benchmark studies; method development | Use cc-pVTZ as minimum for correlated methods; employ n=D,T,Q for extrapolation |

| Ahlrichs def2 Basis Sets [23] | Balanced polarized basis sets for general use | DFT calculations across periodic table; geometry optimizations | Use def2-TZVP for production DFT calculations; def2-SVP for initial optimizations |

| Pople-style Basis Sets [1] | Split-valence with flexible valence description | Initial scans; educational applications; HF/DFT on main-group elements | 6-31G* for preliminary work; 6-311+G for anions/diffuse systems |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) [23] | Replace core electrons with potentials | Heavy elements (beyond Kr); relativistic effects | Use appropriate ECPs for elements beyond 4th period; combine with def2 basis |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets (RI/JK) [23] | Accelerate integral evaluation | Resolution-of-Identity approximation in DFT and correlated methods | Use matched auxiliary sets for primary basis (e.g., def2/J for def2-SVP) |

| Implicit Solvation Models (PBF, COSMO) [24] | Approximate solvent effects | Solution-phase properties; redox potentials; pKa predictions | Include at single-point stage after gas-phase optimization for efficiency |

Diagram 2: Strategic framework for mitigating fortuitous error cancellation through systematic approaches.

The interplay between method and basis set in quantum chemical calculations presents both challenges and opportunities for computational chemists. While fortuitous error cancellation can produce deceptively accurate results for specific systems, relying on such cancellation undermines the transferability and predictive power of computational models. Through systematic approaches including CBS extrapolation, method hierarchy assessments, and balanced protocol design, researchers can develop computational strategies with controlled errors and well-understood limitations.

The future of reliable computational chemistry lies in moving beyond fortuitous error cancellation toward systematically improvable methods and basis sets. As computational power increases and methods refine, the approach of separately minimizing method and basis set errors will become increasingly standard, transforming computational chemistry from a tool that sometimes works for mysterious reasons to a truly predictive science with quantified uncertainty.

Practical Strategies and Extrapolation Techniques for Efficient Convergence

Step-by-Step Protocol for Performing a Convergence Study

In quantum chemistry, the predictive power of a calculation hinges on its numerical accuracy. A convergence study is a systematic process to ensure that computed properties stabilize as key computational parameters are refined. This process verifies that results are not artifacts of the numerical setup but reliable approximations of the physical truth. In the context of basis set convergence, the study confirms that the expansion of the electronic wave function in terms of one-electron basis functions is sufficiently complete for the desired accuracy [25]. Without this critical step, researchers risk basing conclusions on imprecise data, wasting computational resources, and generating non-reproducible results [26].

The core challenge addressed by convergence studies is the inherent trade-off between accuracy and computational cost. Modern quantum chemistry methods, including those deployed on emerging quantum hardware, are profoundly affected by the choice of the basis set and the exchange-correlation functional in Density Functional Theory (DFT) [26] [25]. This guide provides a standardized, step-by-step protocol for performing a convergence study, offering a rigorous framework for researchers and development professionals to ensure the credibility of their computational work.

Core Concepts and the Necessity of Convergence Studies

The Basis Set Convergence Problem

The accuracy of most quantum chemistry calculations is intrinsically linked to the quality of the basis set—a set of mathematical functions used to describe the orbitals of electrons. Smooth Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) are commonly used because they yield tractable integrals, but they fail to capture the sharp electron-cusp condition. This condition arises from the divergence of the Coulomb potential when two electrons coalesce and is a sharp feature of the exact electronic wave function [25]. Consequently, large basis sets are often required to approximate this behavior, leading to a combinatorial increase in computational resource requirements, including the number of qubits needed for simulations on quantum computers [25]. A convergence study determines the point at which enlarging the basis set further yields diminishing returns, thus identifying the most efficient basis for a target precision.

Consequences of Non-Convergence

Skipping convergence studies can lead to severe inaccuracies with real-world costs:

- Misleading Conclusions: Unconverged results for properties like bond lengths or reaction barriers can lead to incorrect predictions of chemical reactivity or molecular stability [26].

- Wasted Resources: Computational time on classical clusters and expensive quantum hardware is squandered on calculations that are either inaccurately coarse or inefficiently fine [26].

- Irreproducible Science: Results that are dependent on an arbitrary or default computational setup cannot be reliably reproduced by other research groups.

The practice is not merely a technical formality but a cornerstone of robust computational science, akin to calibration in wet-lab experiments.

Step-by-Step Convergence Study Protocol

This protocol is designed to be systematic and repeatable. The core workflow involves an initial setup, followed by two interconnected convergence cycles for the basis set and the functional, culminating in a final documentation and validation step.

Figure 1: A systematic workflow for performing a convergence study in quantum chemical calculations.

Step 1: Define the Objective and Initial Setup

- Identify the Target Property: Determine the primary property of interest (e.g., total energy, bond dissociation energy, reaction barrier, vibrational frequency, or bond length). The choice of property can influence the convergence behavior.

- Select a Representative Molecular System: Choose a molecule or model system that is representative of the full series of compounds you plan to study. This balances the cost of the convergence study with its broader applicability.

- Choose a Starting Functional and Basis Set: Begin with a well-established, moderately sized combination.

Step 2: Basis Set Convergence

This step determines the minimum basis set size that yields a stable target property.

- Run a Series of Calculations: Using the initial functional, perform calculations while progressively increasing the basis set size. A typical hierarchy is:

cc-pVDZ→cc-pVTZ→cc-pVQZ[26]. - Monitor and Record Properties: For each calculation, record the target property and the total energy.

- Analyze for Stability: Plot the target property against the basis set level or the number of basis functions. Convergence is achieved when the change in the property between two successive basis set levels falls below a predefined threshold (e.g., a change in energy of less than 1 kcal/mol).

- Select the Converged Basis Set: The basis set immediately before the point where the property stabilizes is your converged choice for subsequent steps.

Step 3: Functional Convergence

With the converged basis set from Step 2, you now test the sensitivity of your results to the exchange-correlation functional.

- Run Calculations with Different Functionals: Perform calculations using a panel of functionals of increasing complexity and theoretical rigor. A recommended progression is:

- GGA (e.g., PBE)

- Meta-GGA (e.g., SCAN)

- Hybrid (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0)

- Range-Separated Hybrid (e.g., ωB97X-V) [26].

- Compare to Benchmark Data: Compare the computed target properties against reliable experimental data or high-level ab initio calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) at the complete basis set limit).

- Select the Optimal Functional: The functional that provides the best agreement with the benchmark data for your specific property and system type, while remaining computationally tractable, should be selected.

Step 4: Final Analysis and Documentation

- Verify with a Final Calculation: Run a single-point calculation on your system of interest using the fully converged parameter set (functional and basis set).

- Document the Entire Process: Maintain a detailed record of all tested parameters, the resulting properties, and the analysis that led to the final choice. This is critical for reproducibility and peer review.

- Report Computational Details: In any publication or report, explicitly state the converged basis set and functional used.

Data Presentation: Comparative Analysis of Computational Parameters

Table 1: Comparison of Standard Basis Sets and Their Properties

| Basis Set | Zeta Quality | Approx. Number of Functions (for C atom) | Common Use Case | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cc-pVDZ | Double-Zeta | 14 | Initial scans, large systems | Low |

| cc-pVTZ | Triple-Zeta | 30 | Standard accuracy for most properties | Medium |

| cc-pVQZ | Quadruple-Zeta | 55 | High-accuracy, final results | High |

| def2-SVP | Double-Zeta | 14 | Quick geometry optimizations | Low |

| def2-TZVP | Triple-Zeta | 32 | Good balance of accuracy and cost | Medium |

| 6-31G(d) | Double-Zeta | 15 | Legacy, educational purposes | Low |

Table 2: Comparison of DFT Functional Performance

| Functional | Type | Typical Accuracy for Thermochemistry | Computational Cost | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | Moderate | Low | Robust, good for solids |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Good | Medium | Historically popular, general-purpose |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | Good | Medium | Modern, improving on B3LYP |

| SCAN | Meta-GGA | Very Good | Medium-High | Accurate for diverse bonding |

| ωB97X-V | Range-Separated Hybrid | High | High | High-accuracy, includes dispersion |

| M06-2X | Hybrid Meta-GGA | High (for main group) | High | Parametrized for non-metals |

Advanced Methods and Protocol Adaptations

Explicitly Correlated Methods for Accelerated Convergence

A powerful strategy to circumvent the slow convergence of traditional basis sets is to use explicitly correlated methods. These approaches incorporate a direct dependence on the inter-electronic distance into the wave function, which satisfies the electron-cusp condition and dramatically accelerates convergence with basis set size.

The Transcorrelated (TC) method is a leading explicitly correlated approach. It uses a similarity transformation to incorporate correlation directly into the Hamiltonian [25]. The primary benefit is that it enables highly accurate results with very small basis sets, significantly reducing the number of qubits required for simulations on quantum computers and yielding more compact ground states that can be represented with shallower quantum circuits [25]. This makes the TC method exceptionally well-suited for both classical computation and the constraints of current and near-term quantum hardware.

Protocol Adaptation for Explicitly Correlated Calculations

When using explicitly correlated methods like TC or F12, the convergence study protocol is streamlined:

- Focus on Functional Convergence: The basis set convergence cycle (Step 2) is greatly compressed. Often, results close to the complete basis set (CBS) limit can be achieved with a triple-zeta basis, or even a double-zeta basis in some cases [25].

- Reduced Qubit Count: The primary resource saving on quantum hardware is a reduction in the number of required qubits, as fewer orbitals are needed to achieve the same accuracy [25].

- Algorithm Consideration: Note that the TC Hamiltonian is non-Hermitian. Its implementation on quantum computers requires algorithms like Variational Quantum Imaginary Time Evolution (VarQITE) that can handle non-Hermitian operators [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Convergence Studies

| Item | Function in the Protocol | Example Tools / Software |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Package | The core software for performing electronic structure calculations. | ORCA, Gaussian, Q-Chem, PySCF, Psi4 |

| Basis Set Library | A source for the mathematical basis functions. | Basis Set Exchange (BSE) website & database |

| Molecular Visualizer | To set up, visualize, and check molecular systems. | Avogadro, GaussView, ChemCraft |

| Scripting Environment | To automate the series of calculations and analyze results. | Python with NumPy/Matplotlib, Jupyter Notebooks, Bash |

| Reference Data Source | Experimental or high-level computational data for benchmarking. | NIST Chemistry WebBook, computational databases (e.g., GMTKN55) |