Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry for Electron Correlation: From Theoretical Foundations to Drug Discovery Applications

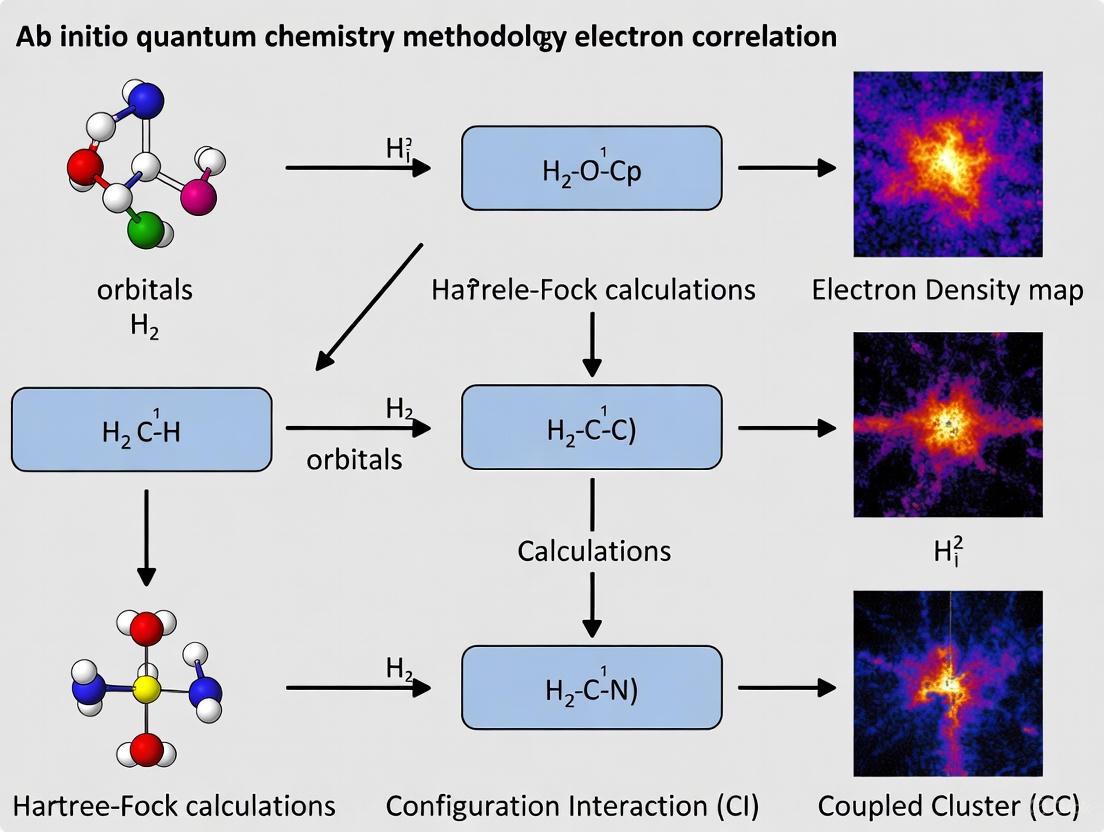

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ab initio quantum chemistry methodologies for treating electron correlation, a critical challenge in predicting molecular behavior with high accuracy.

Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry for Electron Correlation: From Theoretical Foundations to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ab initio quantum chemistry methodologies for treating electron correlation, a critical challenge in predicting molecular behavior with high accuracy. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational theories behind electron correlation, detail key computational methods from post-Hartree-Fock to modern quantum-inspired techniques, and address practical challenges in implementation and optimization. The discussion extends to validation strategies and comparative analysis of method performance, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical research, including drug-target interactions, solvation effects, and reaction profiling. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this work serves as a guide for selecting and applying these powerful computational tools to real-world biomedical problems.

The Electron Correlation Problem: Understanding the Quantum Mechanical Basis

In the pursuit of predicting molecular properties solely from fundamental physical constants and system composition, ab initio quantum chemistry aims to replace convenience-driven classical approximations with rigorous, unified physical theories [1]. At the heart of this endeavor lies the electron correlation problem, a fundamental challenge originating from the approximate treatment of electron-electron interactions in the Hartree-Fock (HF) method. The HF framework provides the foundational wavefunction for most quantum chemical approaches but incorporates electron correlation only incompletely by accounting for the fermionic nature of electrons through antisymmetrized wavefunctions while neglecting the instantaneous Coulomb repulsion between electrons [2]. This limitation manifests mathematically in the relationship between one- and two-electron densities, where HF incorrectly assumes complete independence between electron motions: ( n(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}') = n(\mathbf{r}) n(\mathbf{r}') ) [2].

The correlation energy is formally defined as the difference between the exact non-relativistic energy of a system and its HF energy: ( E{\textrm{corr}} = E{\textrm{exact}} - E{\textrm{HF}} ) [2]. For practical applications with approximate methods, this becomes ( E{\textrm{corr}} = E{\textrm{WF}} - E{\textrm{HF}} ), where ( E_{\textrm{WF}} ) is the energy computed by a selected wavefunction model [2]. This missing correlation energy, though small compared to the total absolute energy, proves crucial for achieving quantitative accuracy in computational chemistry predictions. For instance, in the Hâ‚‚ molecule, the correlation energy calculated using full configuration interaction (FCI) methods amounts to -0.03468928 atomic units, a significant value considering the chemical accuracy target of 1 kcal/mol (approximately 0.0016 atomic units) [2].

Table: Correlation Energy Calculation for Hâ‚‚ Molecule

| Method | Energy (Atomic Units) | Correlation Energy (Atomic Units) |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | -1.12870945 | 0 |

| Full CI | -1.16339873 | -0.03468928 |

This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundation of electron correlation, presents computational methodologies for its capture, provides illustrative case studies, and discusses emerging frontiers within the context of ab initio quantum chemistry methodology. The systematic treatment of electron correlation, in conjunction with other physical effects like relativity and quantum electrodynamics, represents the central trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational feasibility in modern quantum chemistry [1] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: The Physical Origin and Mathematical Definition

Electron correlation arises from two interrelated physical phenomena: the Coulomb repulsion between negatively charged electrons and their fermionic nature requiring antisymmetric wavefunctions. In the HF approximation, each electron moves in an average static field created by all other electrons, effectively smearing out their discrete particle nature. This mean-field approach fails to capture the instantaneous correlation of electron motions, leading to an overestimation of electron density in regions where electrons approach one another closely [2].

The mathematical manifestation of this deficiency appears most clearly in the two-particle density. For a system accurately described by quantum mechanics, the probability of finding two electrons at specific positions is not simply the product of finding each electron independently. The HF method fails to describe the asymmetry in the two-particle density, particularly the reduced probability of finding two electrons positioned at the same nucleus compared to electrons positioned at different nuclei [2]. This fundamental limitation has profound implications for predicting molecular properties, including bond dissociation energies, reaction barriers, and excited state behavior.

The electron cusp, representing the discontinuity in wavefunction derivatives at electron-electron coalescence points, presents particular challenges for standard quantum chemistry methods. As these methods typically do not introduce explicit dependence on interelectronic distances, the electron-electron cusp displays slow convergence with basis set expansion [2]. This slow convergence necessitates sophisticated computational strategies for accurate correlation energy recovery.

Computational Methodologies: Capturing Correlation Effects

The quantum chemistry community has developed numerous theoretical frameworks for capturing electron correlation effects beyond the HF approximation. These methods can be broadly classified into single-reference and multi-reference approaches, each with distinct strengths and computational complexities.

Single-Reference Methods

Single-reference methods build upon the HF wavefunction, making them suitable for systems where a single determinant dominates the wavefunction.

Coupled Cluster (CC) Theory: This highly accurate approach incorporates electron correlation through the exponential ansatz ( \Psi{CC} = e^{T} \Phi0 ), where ( T ) is the cluster operator that generates excitations from the reference wavefunction ( \Phi_0 ). The Fock-space coupled cluster (FS-RCC) method extends this framework to excited states and open-shell systems, with recent applications achieving remarkable accuracy of ≥99.64% for excitation energies in heavy molecules like radium monofluoride [3]. The inclusion of triple excitations (FS-RCCSDT) captures higher-order electron correlation effects crucial for quantitative accuracy [3].

Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: This approach treats electron correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. While second-order MP2 theory provides a cost-effective improvement, its perturbative nature limits accuracy for strongly correlated systems.

Multi-Reference Methods

For systems with significant degeneracy or near-degeneracy, where multiple determinants contribute substantially to the wavefunction, multi-reference methods become essential.

Multi-Reference Configuration Interaction (MRCI): This approach generates excitations from multiple reference determinants, providing a robust description of static correlation. The recently developed nuclear-electronic orbital multireference configuration interaction (NEO-MRCI) extends this capability to include quantum nuclear effects, producing high-quality excitation energies and tunneling probabilities for systems where select nuclei (typically hydrogen) are treated quantum mechanically [4].

Complete Active Space (CAS) Methods: CAS approaches select an active space of orbitals and electrons and perform full CI within this space, providing a balanced treatment of static correlation. The significant challenge lies in incorporating dynamic correlation beyond large active spaces, with recent methodological advances categorizing seven distinct approaches to address this computational bottleneck [5].

Table: Classification of Electron Correlation Methods

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Reference | Coupled Cluster (CCSD, CCSD(T)), MP2 | High accuracy for single-reference systems, systematic improvability | Computational cost, fails for strongly correlated systems |

| Multi-Reference | CASSCF, MRCI, NEO-MRCI | Handles static correlation, degenerate states | Active space selection, computational scaling |

| Perturbative | MP2, CASPT2 | Cost-effective improvement over reference | Convergence issues, dependent on reference quality |

| Quantum Embedding | DMET, DMRG | Handles large systems, strong correlation | Implementation complexity, transferability |

Advanced Technical Implementation: Protocols and Workflows

Relativistic Coupled Cluster Protocol for Heavy Elements

For molecules containing heavy elements, where relativistic effects become significant, the following protocol exemplifies state-of-the-art treatment of electron correlation:

Reference Wavefunction Generation: Perform a four-component Dirac-Hartree-Fock calculation incorporating relativistic effects at the mean-field level [3].

Basis Set Selection: Employ correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., aug-Dyall CV4Z) specifically designed for relativistic calculations. For highest accuracy, extend to larger basis sets (AE3Z, AE4Z) and apply complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation techniques [3].

Electron Correlation Treatment: Implement Fock-space coupled cluster with single, double, and triple excitations (FS-RCCSDT). Correlate at least the valence and outer-core electrons (e.g., 69 electrons in RaF), with verification of convergence by including all electrons [3].

Hamiltonian Refinement: Incorporate the Gaunt interaction for magnetic relativistic effects and quantum electrodynamics (QED) corrections, particularly important for heavy elements [3].

Property Calculation: Compute molecular properties including excitation energies, bond lengths, and spectroscopic constants, comparing with experimental measurements where available.

This protocol achieved exceptional agreement (within ~12 meV) with experimental excitation energies for all 14 lowest excited states in radium monofluoride, demonstrating the power of sophisticated correlation treatment combined with relativistic methodology [3].

Dynamic Correlation Beyond Large Active Spaces

For strongly correlated systems requiring large active spaces, capturing residual dynamic correlation presents significant computational challenges. The following workflow addresses this bottleneck [5]:

Active Space Selection: Identify the strongly correlated orbitals and electrons through chemical intuition or automated procedures.

Reference Calculation: Perform a CASSCF calculation to obtain the reference wavefunction capturing static correlation.

Dynamic Correlation Treatment: Apply one of seven categorized approaches to capture dynamic correlation from the external space, with particular emphasis on methods avoiding high-order reduced density matrices:

- Multi-reference perturbation theory (e.g., CASPT2)

- Multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI)

- Density matrix renormalization group (DMRG)

- Quantum embedding techniques

Benchmarking: Validate methodology using challenging systems such as neodymium oxide (NdO) potential energy curves [5].

Diagram: Electron Correlation Method Selection Workflow. The decision pathway guides researchers in selecting appropriate electron correlation methods based on system characteristics.

Case Studies and Quantitative Analysis

Radium Monofluoride: Precision Spectroscopy

The radioactive molecule radium monofluoride (RaF) represents a rigorous test case for state-of-the-art electron correlation methods. Recent experimental and theoretical investigations of the 14 lowest excited electronic states demonstrate the critical importance of high-order electron correlation and relativistic effects [3].

FS-RCC calculations with increasing levels of sophistication reveal the quantitative impact of various correlation effects on excitation energies. The inclusion of triple excitations (27e-T correction) through the FS-RCCSDT approach provides corrections on the order of tens of cmâ»Â¹, while Gaunt interaction and QED effects contribute smaller but non-negligible corrections [3]. The systematic treatment of these effects enables agreement with experimental excitation energies exceeding 99.64% accuracy.

Table: Impact of Correlation Effects on RaF Excitation Energies

| Correction Type | Typical Energy Contribution | Computational Cost | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triple Excitations (T) | Up to tens of cmâ»Â¹ | Very High | High-order electron correlation |

| Gaunt Interaction | Few cmâ»Â¹ | Moderate | Magnetic relativistic effects |

| QED Effects | Few cmâ»Â¹ | Moderate | Quantum electrodynamics |

| Basis Set (CBS) | Variable | Moderate to High | Basis set completeness |

Hydrogen Molecule: Correlation Visualization

The Hâ‚‚ molecule provides the simplest system for visualizing electron correlation effects. Comparative analysis of one- and two-particle densities at HF and FCI levels reveals subtle but important differences [2]:

One-particle density shows minimal differences between HF and FCI, with only a slight decrease in electron density in the bond midpoint compensated by minor increases around nuclei [2].

Two-particle density demonstrates dramatic deficiencies in the HF approximation. When one electron is fixed at a hydrogen nucleus position, the HF method fails to capture the asymmetry in the probability distribution for the second electron, overestimating the probability of both electrons residing at the same nucleus [2].

These visualizations underscore that electron correlation manifests primarily in the joint probability distribution of electron pairs rather than in the one-electron density.

Implementing advanced electron correlation methods requires specialized computational tools and theoretical components:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Electron Correlation Studies

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets | Systematic basis sets for convergent correlation energy recovery | cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, aug-Dyall CV4Z for relativistic calculations [3] |

| Relativistic Effective Core Potentials | Replace core electrons with potentials for heavy elements | GRECP for 2-component relativistic calculations [3] |

| Coupled Cluster Implementations | High-accuracy single-reference correlation methods | FS-RCC for excited states of open-shell systems [3] |

| Multi-Reference Codes | Handle static correlation in degenerate systems | NEO-MRCI for nuclear-electronic systems [4] |

| Quantum Electrodyamics Corrections | Include QED effects in molecular calculations | Lamb shift calculations for heavy elements [3] |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Frontiers

The ongoing evolution of electron correlation methodology focuses on several key frontiers:

Strongly Correlated Systems: A central challenge in modern condensed matter physics and quantum chemistry remains the understanding of materials with strong electron correlations, where theories based on non-interacting particles fail qualitatively [6]. The "Anna Karenina Principle" may apply—all non-interacting systems are alike; each strongly correlated system is strongly correlated in its own way [6].

Quantum Computing Applications: Emerging quantum algorithms offer potential breakthroughs for electron correlation problems, particularly for strongly correlated systems where classical computational costs become prohibitive.

Machine Learning Enhancements: Data-driven approaches and machine learning techniques show promise for approximating potential energy surfaces and correlation energies with reduced computational expense while maintaining quantum accuracy [7].

Nuclear Quantum Effects: The nuclear-electronic orbital (NEO) approach treats select nuclei (typically hydrogen) quantum mechanically on the same level as electrons, with recent developments in NEO coupled cluster (NEO-CC) theory providing a path to "gold standard" reference calculations that accurately capture nuclear delocalization and anharmonic zero-point energy [4].

Diagram: Theoretical Hierarchy in Ab Initio Chemistry. Electron correlation represents one essential component in the comprehensive hierarchy of physical theories underlying modern quantum chemistry.

Electron correlation represents both a fundamental challenge and opportunity in ab initio quantum chemistry. Moving beyond the Hartree-Fock mean-field approximation requires sophisticated theoretical frameworks and computational methodologies that balance accuracy with feasibility. The hierarchical approach of progressively incorporating physical effects—from electron correlation to relativistic and QED corrections—systematically extends the domain of first-principles prediction [1]. As methodological advances continue to push the boundaries of correlated electron structure theory, the integration of physical principles with computational innovation promises to unlock new frontiers in predictive quantum chemistry across diverse scientific domains, from drug development to materials design. The ongoing refinement of electron correlation methods remains essential for achieving the ultimate goal of ab initio quantum chemistry: quantitative property prediction based solely on fundamental constants and system composition.

The Physical Significance of Electron Correlation for Molecular Properties

Electron correlation represents a cornerstone challenge in ab initio quantum chemistry, describing the deviation from the mean-field approximation where the instantaneous, correlated motion of electrons is neglected. This in-depth technical guide elucidates the profound physical significance of electron correlation for the accurate prediction of molecular properties. Framed within the broader context of ab initio methodology development, this review synthesizes current theoretical frameworks and computational approaches designed to capture correlation effects. It further provides a detailed analysis of their application in predicting key molecular observables—from bond dissociation energies and electronic excitations to properties of heavy-element systems and supramolecular assemblies. The discussion is supported by structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and specialized toolkits, offering researchers and drug development professionals a comprehensive resource for navigating this complex yet indispensable domain of electronic structure theory.

The pursuit of predicting molecular properties solely from fundamental physical constants and system composition, the core tenet of ab initio quantum chemistry, is built upon an interdependent hierarchy of physical theories [1]. Within this framework, the treatment of electron-electron interactions presents a central challenge. The independent-electron model, exemplified by the Hartree-Fock method, treats these interactions in an average way, neglecting the instantaneous correlation in electron motions. The energy difference between this approximate model and the exact solution of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation is defined as the electron correlation energy.

The physical significance of this energy is immense; it is comparable in magnitude to the energy of making or breaking chemical bonds [8]. Consequently, ignoring electron correlation leads to qualitatively and quantitatively incorrect predictions for a vast array of molecular properties, including reaction energies, bond dissociation profiles, electronic spectra, and magnetic interactions. The ongoing evolution of ab initio methods constitutes a systematic effort to replace convenience-driven approximations with rigorous, unified physical theories, with the accurate treatment of electron correlation being a primary frontier [1].

This guide details the physical manifestations of electron correlation, surveys state-of-the-art methodologies for its description, and provides a quantitative overview of its impact on molecular properties through curated data and protocols.

Theoretical Frameworks and Physical Manifestations

Static vs. Dynamic Correlation

Electron correlation manifests in two primary forms, each with distinct physical origins and methodological requirements:

Static (or Strong) Correlation: This occurs in systems with degenerate or near-degenerate electronic configurations, such as bond-breaking processes, transition metal complexes, and open-shell radicals. It necessitates a multi-reference description, where the wavefunction is expressed as a combination of several Slater determinants. The pursuit of accurate calculations for large, strongly correlated systems presents significant challenges, stemming from the complexity of treating static correlations within extensive active spaces [5].

Dynamic Correlation: This refers to the correlated motion of electrons due to their instantaneous Coulomb repulsion, which avoids the mean-field description. It is ubiquitous in all electronic systems. The challenge lies in efficiently incorporating these effects from the vast external space of unoccupied orbitals beyond a chosen active space [5].

The Multi-Reference Challenge and Advanced Formalisms

Quantitatively accurate calculations for realistic, strongly correlated systems require addressing both static and dynamic correlation. Methods are often organized based on how they circumvent the computational burden associated with high-order reduced density matrices [5]. Furthermore, for heavy elements, the interplay between electron correlation and relativistic effects becomes critical and cannot be treated perturbatively. State-of-the-art approaches like the Fock-space coupled cluster (FS-RCC) method are designed to handle this interplay, even capturing quantum electrodynamics (QED) corrections for the highest precision [3].

The physical implications of correlation are also profound in nanoscale systems. For instance, in supramolecular assemblies of radical molecules on surfaces, electron correlation can lead to emergent phenomena like Coulomb rings and cascade discharging events, which are foundational for developing high-density spin networks for quantum technologies [9].

Quantitative Impact on Molecular Properties

The following tables summarize the critical influence of electron correlation on specific molecular properties, as revealed by advanced ab initio calculations.

Table 1: Impact of Electron Correlation on Diatomic Molecule Energetics and Structure

| Molecule | Property | Method (Correlation Treatment) | Value | Key Finding / Role of Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ScH⺠[10] | Bond Dissociation Energy (D₀) | MRCI+Q / CCSD(T) | ~55.45 kcal/mol | Core electron correlation is vital for accurate prediction. |

| YH⺠[10] | Bond Dissociation Energy (D₀) | MRCI+Q / CCSD(T) | ~60.54 kcal/mol | Spin-orbit coupling effects become substantial. |

| LaH⺠[10] | Bond Dissociation Energy (D₀) | MRCI+Q / CCSD(T) | ~62.34 kcal/mol | Strong correlation in 4f/5d shells necessitates high-level methods. |

| NdO [5] | Potential Energy Curves | Multi-reference methods | N/A | Critical for describing static & dynamic correlation in lanthanides. |

Table 2: Role of Correlation and Relativity in Heavy Element Spectroscopy

| Molecule | Property | Method | Agreement with Experiment | Correlation/Relativity Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RaF [3] | 14 Lowest Excited States | FS-RCCSDT with Gaunt & QED | ≥99.64% (within ~12 meV) | High-order correlation (Triples) and QED are important for all states. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Reference Calculation for Potential Energy Curves

This protocol is used for mapping potential energy curves of strongly correlated systems like NdO [5].

- Active Space Selection: Define an active space comprising molecular orbitals that are energetically close to the frontier orbitals and relevant to the correlation effect under study. This space must be large enough to capture static correlation.

- Reference Wavefunction Generation: Perform a Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) calculation to optimize the orbitals and configuration coefficients within the active space for each geometry along the bond dissociation coordinate.

- Dynamic Correlation Treatment: Apply a post-CASSCF method to account for dynamic correlation from electrons outside the active space. This can include:

- Multi-Reference Configuration Interaction (MRCI)

- Second-order Perturbation Theory (CASPT2) . Other methods that avoid high-order density matrices.

- Property Calculation: Use the converged multi-reference wavefunction to compute the total energy at each geometry and plot the potential energy curve. Analyze the wavefunction composition (e.g., dominant configurations) at critical points.

Protocol 2: Orbital Entropy and Correlation Analysis on a Quantum Computer

This protocol quantifies orbital-wise correlation and entanglement, as demonstrated for the vinylene carbonate + Oâ‚‚ reaction system [11].

- Classical Pre-processing:

- Use DFT (e.g., PBE/def2-SVP) with the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method to locate reaction pathway and transition state geometries.

- Perform an Atomic Valence Active Space (AVAS) projection to identify strongly correlated molecular orbitals localized on key atoms (e.g., oxygen p orbitals).

- Run CASSCF calculations within the selected active space to obtain the classical reference wavefunction and configuration interaction (CI) coefficients.

- Quantum State Preparation:

- Encode the fermionic Hamiltonian into qubits using a transformation (e.g., Jordan-Wigner).

- Prepare the ground state wavefunction on the quantum computer using a variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) ansatz, optimized offline based on the CASSCF results.

- Quantum Measurement and Analysis:

- Construct orbital reduced density matrices (ORDMs) by measuring relevant Pauli operator sets on the quantum hardware.

- Account for fermionic superselection rules (SSRs) to reduce the number of measurements and avoid overestimating entanglement.

- Apply noise-mitigation techniques (e.g., singular value thresholding) to the measured ORDMs.

- Compute the von Neumann entropy from the eigenvalues of the noise-corrected 1- and 2-ORDMs to quantify orbital correlation and entanglement.

The workflow for this multi-reference treatment and analysis is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Methods and Their Functions in Electron Correlation Research

| Tool / Method | Category | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASSCF [11] | Wavefunction | Treats static correlation by optimizing orbitals and CI coefficients in an active space. | Scaling with active space size is a major limitation. |

| MRCI [10] | Wavefunction | Adds dynamic correlation on top of a multi-reference wavefunction; high accuracy. | Computationally expensive; size-extensivity error exists but can be corrected (e.g., +Q). |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T), FS-RCC) [3] [10] | Wavefunction | "Gold standard" for single-reference systems; FS-RCC extends to multi-reference and relativistic regimes. | High computational cost; FS-RCC is complex to implement but powerful for heavy elements. |

| Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) [12] | Wavefunction | Uses stochastic methods to solve the Schrödinger equation, directly handling electron correlation. | Computationally demanding; success depends on the quality of the trial wavefunction. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [8] | Density Functional | Approximates correlation via a functional; offers a unique balance of speed and reliability. | Accuracy depends on the functional; systematic improvement is challenging. |

| AVAS Projection [11] | Active Space Selection | Automatically generates a compact, chemically relevant active space by projecting onto atomic orbitals. | Reduces human bias; produces localized orbitals that help avoid overestimation of correlation. |

| 2,4,4-Trimethyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-CoA | 2,4,4-Trimethyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-CoA, MF:C29H50N7O18P3S, MW:909.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 10-hydroxyheptadecanoyl-CoA | 10-hydroxyheptadecanoyl-CoA, MF:C38H68N7O18P3S, MW:1036.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The physical significance of electron correlation is unequivocal; it is a fundamental interaction that dictates the accuracy of predictive computational chemistry. As this guide has detailed, its rigorous treatment requires sophisticated, and often computationally demanding, ab initio methodologies. The field is continuously evolving, with current research pushing several frontiers:

- Integration of Machine Learning: New data-driven quantum chemistry methodologies are being developed to "learn" complex molecular wavefunctions, offering the promise of accurate and transferable computations for larger, more complex molecules [13].

- Advances in Quantum Computing: As demonstrated, quantum computers are emerging as a platform for directly probing correlation and entanglement in molecular orbitals, providing new insights that are prohibitive for classical computation [11].

- Development of Efficient Multi-Reference Methods: There is a concerted effort to create new methods that systematically treat dynamic correlation beyond large active spaces without the prohibitive cost of high-order density matrices [5].

- Synergy with Relativity and QED: For heavy elements, the combined, non-perturbative treatment of correlation, relativity, and even quantum electrodynamics effects is becoming the new standard for achieving high-precision predictions [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging these advanced tools and understanding the physical implications of electron correlation is no longer optional but essential for achieving predictive accuracy in molecular design and property evaluation.

The goal of ab initio quantum chemistry is to predict molecular properties solely from fundamental physical constants and system composition, without empirical parameterization. This endeavor is built upon an interdependent hierarchy of physical theories, each contributing essential concepts and introducing inherent approximations. The entire field is framed by a central trade-off: the rigorous inclusion of physical effects—from electron correlation to relativistic corrections—versus the associated computational cost [1].

At the heart of this challenge lies the electron correlation problem. Electron correlation represents the interaction between electrons that is not captured via the mean-field approximation, arising due to their mutual electrostatic repulsion. This correlation leads to complex quantum effects that cannot be represented by simple mathematical models [14]. The ongoing evolution of ab initio methods represents a systematic effort to replace convenience-driven classical approximations with rigorous, unified physical theories, thereby extending the domain of first-principles prediction [1].

Wavefunction-Based Methods

Theoretical Foundation

Wavefunction-based methods explicitly solve for the electronic wavefunction, which contains all information about a quantum system. Unlike density functional theory, which focuses on electron density, these methods attempt to directly solve or approximate the many-electron Schrödinger equation [15].

The fundamental challenge is the exponential growth of computational complexity with system size. As Pauli Dirac noted, while the underlying physical laws for chemistry are completely known, "the exact application of these laws leads to equations that are much too complicated to solve" [16]. This makes exact solutions of the electronic Schrödinger equation for more than a few atoms impossible.

Key Methodologies and Hierarchies

A hierarchy of increasingly accurate wavefunction-based methods has emerged to address the electron correlation problem:

Hartree-Fock (HF) Theory: The foundational wavefunction method that employs a mean-field approximation where each electron experiences the average field of the others. While it accounts for electron exchange via the antisymmetry of the wavefunction, it completely neglects electron correlation [14] [15].

Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: These methods introduce electron correlation on top of the HF reference:

- Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory: Adds electron correlation via Rayleigh-Schrödinger perturbation theory. MP2 (second-order) is widely used for its favorable cost-accuracy balance, but can overestimate interaction energies in systems with large polarizabilities [16].

- Coupled-Cluster (CC) Theory: A high-accuracy method that uses an exponential wavefunction ansatz. CCSD(T), which includes single, double, and perturbative triple excitations, is often considered the "gold standard" for molecular quantum chemistry of weakly correlated systems [16].

- Configuration Interaction (CI): Approaches the exact solution by expressing the wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants with different electron configurations [17].

Recent research has revealed limitations in the widely-used CCSD(T) method. For large, polarizable molecules, the (T) approximation can cause "overcorrelation," leading to significantly overestimated interaction energies. Modified approaches like CCSD(cT) that include selected higher-order terms show improved performance for such systems [16].

Multiconfigurational Methods

For systems with significant static correlation (where multiple electronic configurations contribute substantially to ground or excited states), single-reference methods like CCSD(T) face challenges. Examples include transition metal complexes, bond-breaking processes, and molecules with near-degenerate electronic states [18].

Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) methods address this by performing a full CI within a carefully selected active space of orbitals and electrons, providing a balanced treatment of static correlation but becoming computationally prohibitive for large active spaces.

Density Functional Theory

Theoretical Foundations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a paradigm shift from wavefunction-based approaches. Instead of working with the complex many-electron wavefunction, DFT focuses on the electron density, a function describing the probability of finding electrons in space [19].

The theoretical foundation rests on two fundamental theorems by Hohenberg and Kohn:

- The ground-state energy of an interacting electron system is uniquely determined by the electron density (Ï).

- The functional that provides the ground-state energy achieves its minimum value for the true ground-state density [15].

The Kohn-Sham framework introduced a practical approach by postulating a system of non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the interacting system. The total energy functional in Kohn-Sham DFT is expressed as:

[ E[\rho] = T\text{s}[\rho] + V\text{ext}[\rho] + J[\rho] + E_\text{xc}[\rho] ]

where:

- ( T_\text{s}[\rho] ) is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons

- ( V_\text{ext}[\rho] ) is the external potential energy

- ( J[\rho] ) is the classical Coulomb energy

- ( E_\text{xc}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation energy, incorporating all quantum many-body effects [15]

The success of DFT hinges on ( E_\text{xc}[\rho] ), which must be approximated since its exact form is unknown.

The Exchange-Correlation Functional: Jacob's Ladder

The accuracy of DFT calculations depends critically on the choice of exchange-correlation functional. These functionals have evolved through multiple generations, often visualized as "Jacob's Ladder" of DFT, ascending toward "chemical accuracy" [15].

Table 1: Hierarchy of Exchange-Correlation Functionals in DFT

| Functional Type | Description | Key Ingredients | Representative Examples | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/LSDA | Local (Spin) Density Approximation | Local density ( \rho(r) ) | VWN, VWN5 | Early solids; overbinds molecules |

| GGA | Generalized Gradient Approximation | Density + gradient ( \nabla\rho(r) ) | PBE, BLYP, PW91 | Geometry optimizations |

| meta-GGA | meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation | Density + gradient + kinetic energy density ( \tau(r) ) | TPSS, M06-L, SCAN | Improved energetics |

| Hybrid | Mixes DFT exchange with HF exchange | GGA/mGGA + Hartree-Fock exchange | B3LYP, PBE0 | General-purpose chemistry |

| Range-Separated Hybrids | Distance-dependent HF/DFT mixing | Screened Coulomb operators | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X | Charge-transfer, excited states |

Advanced DFT Formulations

Recent years have seen the development of sophisticated DFT approaches that address specific limitations:

Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT) combines wavefunction and DFT approaches by calculating the total energy using a multiconfigurational wavefunction for the classical energy and a density functional for the nonclassical energy. The recently developed MC23 functional incorporates kinetic energy density for more accurate description of electron correlation, particularly for systems with strong static correlation [18].

Quantum Electroynamical DFT (QED-DFT) extends traditional DFT to describe strongly coupled light-matter interactions in optical cavities using the Pauli-Fierz nonrelativistic QED Hamiltonian. This framework bridges quantum optics and electronic structure theory, enabling the study of polaritonic chemistry [17].

Comparative Analysis: Accuracy vs. Computational Cost

Performance Across Chemical Problems

The choice between wavefunction methods and DFT involves balancing computational cost against required accuracy. The following table provides a comparative overview of key methodologies:

Table 2: Method Comparison for Electron Correlation Treatment

| Method | Computational Scaling | System Size Limit | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | ( N^4 ) | ~100 atoms | No self-interaction error; reference for correlated methods | Neglects electron correlation |

| MP2 | ( N^5 ) | ~100 atoms | Accounts for dynamic correlation; relatively inexpensive | Overbinds; fails for metallic systems |

| CCSD(T) | ( N^7 ) | ~10-20 atoms | "Gold standard" for small molecules | Prohibitively expensive for large systems |

| DFT (GGA) | ( N^3 ) | ~1000 atoms | Good cost-accuracy balance; widely applicable | Self-interaction error; depends on functional |

| DFT (Hybrid) | ( N^4 ) | ~100-500 atoms | Improved accuracy for diverse properties | Higher cost than pure DFT |

| MC-PDFT | Varies | ~100 atoms | Handles strong correlation; better than KS-DFT for multiconfigurational systems | Depends on active space selection |

Addressing the Accuracy Challenge

Recent investigations have revealed concerning discrepancies between high-accuracy methods for large molecules. Significant differences have been observed between diffusion quantum Monte Carlo (DMC) and CCSD(T) predictions for noncovalent interaction energies in large molecules on the hundred-atom scale. These discrepancies appear to stem from the truncation of the triple particle-hole excitation operator in CCSD(T), particularly problematic for systems with large polarizabilities [16].

Such findings highlight the importance of method selection based on specific chemical problems and system sizes. They also underscore the ongoing need for method development and careful benchmarking, especially as quantum chemistry applications expand to larger and more complex systems relevant to drug design and materials science.

Computational Protocols and Implementation

Practical Implementation of Electronic Structure Calculations

Successful application of theoretical methods requires careful attention to computational protocols:

Basis Sets: Electronic structure calculations typically expand molecular orbitals as linear combinations of basis functions. Common choices include:

- Gaussian-type orbitals: Standard for molecular calculations (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, aug-cc-pVXZ series)

- Plane waves: Preferred for periodic systems

- Numerical atomic orbitals: Used in various codes for efficiency

Geometry Optimization: Most electronic structure calculations require optimized molecular geometries, obtained by minimizing energy with respect to nuclear coordinates until forces fall below a threshold (typically 0.001 eV/Ã… or similar).

Energy Calculations: Single-point energy calculations on optimized structures provide thermodynamic information, while frequency calculations confirm stationary points and provide vibrational data.

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources

| Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Software package | Molecular quantum chemistry | Molecular systems in vacuum/solution |

| VASP | Software package | Periodic DFT | Solids, surfaces, interfaces |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Software package | Periodic DFT | Materials science; open-source |

| Plane Wave Basis Sets | Computational resource | Basis for periodic systems | Solid-state calculations |

| Gaussian Basis Sets | Computational resource | Basis for molecular systems | Molecular quantum chemistry |

| Pseudopotentials | Computational resource | Replace core electrons | Reduce computational cost for heavy elements |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Methodological Innovations

The field of electronic structure theory continues to evolve rapidly with several promising directions:

Machine Learning Enhancements: Machine learning models are being trained on DFT-calculated datasets to predict properties faster, while AI is helping improve exchange-correlation functionals. Deep learning approaches are enabling large-scale hybrid functional calculations with reduced computational cost [20].

Quantum Computing: Quantum algorithms offer potential advantages for certain electronic structure problems, though recent evidence suggests exponential quantum advantage is unlikely for generic problems of interest [20].

Embedding Methods: Multi-scale quantum embedding schemes allow accurate simulation of complex systems like catalytic surfaces by combining high-level theory for the active region with lower-level methods for the environment [20].

Expanding Domains of Application

Novel theoretical frameworks are extending the reach of quantum chemistry:

Fractional Quantum Hall Systems: Surprisingly, DFT has found application in strongly correlated topological systems like fractional quantum Hall effects through composite fermion theory, demonstrating the method's expanding applicability [21].

Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics: QED-DFT frameworks enable the study of molecules strongly coupled to quantized electromagnetic fields in optical cavities, providing insights into polaritonic chemistry and modified reaction dynamics [17].

The theoretical frameworks for electron correlation in ab initio quantum chemistry present a rich landscape of complementary approaches. Wavefunction-based methods offer systematic improvability and high accuracy for small systems, while DFT provides the best compromise between accuracy and computational cost for many practical applications. The ongoing methodological developments—from improved functionals and wavefunction approximations to machine learning enhancements—continue to extend the frontiers of what is computationally feasible while maintaining quantum accuracy.

As these methods evolve, they empower researchers across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery to tackle increasingly complex challenges, from catalyst design to understanding biological systems. The choice of method ultimately depends on the specific scientific question, system size, property of interest, and available computational resources, with the optimal approach often involving multiple complementary techniques.

In the field of ab initio quantum chemistry, the pursuit of accurate electron correlation treatments confronts a fundamental constraint: computational cost. Ab initio quantum chemistry methods, which compute molecular properties by solving the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles using only physical constants and the positions of electrons, represent the cornerstone of predictive electronic structure theory [22]. The accuracy of these methods is paramount for reliable predictions in drug design and materials science, yet this accuracy comes at a steep computational price that scales dramatically with system size. This scaling problem forms the critical balancing act that theoretical chemists must manage—weighing the need for chemical accuracy against available computational resources.

The computational scaling of quantum chemistry methods is quantified by how their resource demands increase with a relative measure of system size (N). Electron correlation methods beyond the mean-field approximation are particularly expensive, with costs ranging from Nⴠfor second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) to Nⷠfor the highly accurate coupled-cluster with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples (CCSD(T)) method [22]. As molecular systems of interest in pharmaceutical research grow increasingly complex—from small drug candidates to protein-ligand complexes—this computational scaling becomes the primary bottleneck for predictive modeling. Understanding, managing, and ultimately overcoming this scaling problem is thus essential for advancing electron correlation research in practical applications.

Computational Scaling of Ab Initio Methods: A Quantitative Analysis

Theoretical Scaling Relationships

The computational scaling of quantum chemical methods arises from the mathematical structure of the electronic Schrödinger equation and the need to approximate its solution. Hartree-Fock (HF) theory, which serves as the starting point for most correlated methods, has a nominal scaling of Nⴠdue to the two-electron integrals required [22]. In practice, this can be reduced to approximately N³ through the identification and neglect of negligible integrals. However, the HF method fails to account for the correlated motion of electrons, necessitating more sophisticated—and expensive—post-Hartree-Fock approaches.

Table 1: Computational Scaling of Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Key Characteristics | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Nⴠ(reducible to ~N³) | Neglects electron correlation; variational | Reference for correlated methods |

| MP2 | Nâ´ | Accounts for ~80-90% of correlation energy | Moderate accuracy; large systems |

| MP3 | Nⶠ| Improvement over MP2 | Moderate accuracy |

| MP4 | Nâ· | Includes more excitations | Higher accuracy |

| CCSD | Nⶠ| Highly accurate for single-reference systems | Benchmark quality |

| CCSD(T) | Nâ· | "Gold standard" for single-reference systems | Highest accuracy; small to medium systems |

| Local MP2 | ~N (asymptotically) | Exploits spatial decay of correlations | Large molecules |

| DFT | N³-Nⴠ| Includes correlation via functionals | Balance of efficiency/accuracy |

The scaling behavior illustrated in Table 1 presents a severe limitation for applications to biologically relevant systems. For example, while CCSD(T) provides exceptional accuracy for molecular properties and reaction energies, its Nâ· scaling restricts its routine application to systems with approximately 10-20 non-hydrogen atoms. This limitation is particularly problematic in drug discovery contexts where molecular systems of interest often contain hundreds of atoms.

Accuracy versus Cost Trade-offs

The relationship between computational cost and accuracy is not linear, creating diminishing returns as one moves toward higher-level methods. As recent research notes, "The computational workload of our method is similar to the Hartree-Fock approach while the results are comparable to high-level quantum chemistry calculations" [23]. This highlights the ongoing pursuit of methods that can achieve high accuracy without the prohibitive cost of traditional approaches.

Table 2: Accuracy and Resource Requirements for Correlation Methods

| Method | Relative Energy Error | Memory Requirements | Disk Space | System Size Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | 10-50% (varies widely) | Low | Moderate | ~1000 atoms |

| MP2 | 5-10% | Moderate | High | ~500 atoms |

| CCSD | 1-3% | High | Very High | ~50 atoms |

| CCSD(T) | 0.5-1% | Very High | Extreme | ~20 atoms |

| Local MP2 | 5-10% | Moderate | Moderate | ~1000 atoms |

| CMR | 1-3% (estimated) | Moderate | Moderate | ~200 atoms |

The accuracy limitations of standard methods become particularly pronounced for challenging chemical systems. As demonstrated in studies of hydrogen and nitrogen clusters, "the HF results show large systematic errors, especially at large separations where the electron correlation effect becomes prominent" [23]. This underscores the necessity of electron correlation methods for quantitatively accurate predictions, especially in systems with strong correlation effects or bond-breaking processes.

Methodological Advances for Scalable Electron Correlation

Local Correlation Approaches

Local correlation methods address the scaling problem by exploiting the nearsightedness of electronic correlations—the physical principle that electron correlation effects decay with distance. These approaches "significantly reduce memory and improve compute efficiency, without affecting accuracy control" [24]. The key insight is that for large molecules, most electron correlation is local, with only minor contributions from distant electrons.

Recent optimizations in local correlation algorithms have demonstrated substantial improvements. As noted in a 2025 study, "a novel embedding correction to the right-hand-side of the linear equations for the retained MP2 amplitudes, which includes the effect of integrals that are evaluated but discarded as below threshold" provided "roughly an order of magnitude improvement in accuracy" [24]. This embedding approach, combined with "modified set of occupied orbitals that increases diagonal dominance in the occupied-occupied Fock operator," represents the cutting edge in local correlation methodology.

Diagram 1: Traditional vs Local Correlation Approaches

Density Fitting and Linear Scaling Methods

The density fitting (DF) approximation, also known as the resolution of the identity (RI) approach, reduces the scaling prefactor and memory requirements by representing the electronic density in an auxiliary basis. In this scheme, "the four-index integrals used to describe the interaction between electron pairs are reduced to simpler two- or three-index integrals" [22]. When combined with local correlation methods, the resulting df-LMP2 and df-LCCSD(T0) methods can achieve near-linear scaling for large systems.

A 2025 benchmark study demonstrated that these optimized local methods can outperform alternative approaches: "Detailed comparisons against the domain-localized pair natural orbital, DLPNO-MP2, algorithm in the ORCA 6.0.1 package demonstrate significant improvements in accuracy for given time-to-solution" [24]. The benchmarks included conformational energies of the ACONF20 set, non-covalent interactions in S12L and ExL8 datasets, C60 isomerization energies, and transition metal complex energetics from the MME55 set—comprehensive testing across diverse chemical problems.

Emerging Approaches: Correlation Matrix Renormalization

The Correlation Matrix Renormalization (CMR) theory represents an alternative approach that "is free of adjustable Coulomb parameters and has no double counting issues in the calculation of total energy and has the correct atomic limit" [23]. This method extends the traditional Gutzwiller approximation for one-particle operators to the evaluation of expectation values of two-particle operators in the many-electron Hamiltonian.

In tests on hydrogen clusters, "the bonding and dissociation behavior of the hydrogen clusters calculated from the CMR method agrees very well with the exact CI results" [23]. Notably, the computational cost of CMR is similar to the Hartree-Fock approach while delivering accuracy comparable to high-level quantum chemistry calculations. This makes it particularly promising for large systems where conventional correlated methods become prohibitively expensive.

Experimental Protocols for Scalable Electron Correlation

Local MP2 with Embedding Correction Protocol

The following protocol details the optimized local MP2 approach with embedding correction as described in recent literature [24]:

System Preparation

- Obtain molecular geometry and define atomic basis set

- Perform Hartree-Fock calculation to obtain reference wavefunction

- Localize molecular orbitals using Pipek-Mezey or Boys localization

Orbital Transformation and Domain Construction

- Transform the virtual orbital space to a local basis (e.g, PAO, RI)

- Construct orbital domains for each electron pair based on spatial proximity

- Generate pair lists and classify as strong, weak, or distant pairs

Integral Evaluation and Screening

- Compute electron repulsion integrals using density fitting

- Apply numerical thresholds to neglect small integrals (controlled by ε)

- Screen distant pair correlations using distance-based criteria

Amplitude Equations with Embedding Correction

- Set up the system of linear equations for MP2 amplitudes

- Apply the novel embedding correction to include effects of discarded integrals

- Use modified occupied orbitals to enhance diagonal dominance

Iterative Solution and Energy Evaluation

- Solve amplitude equations using conjugate gradient method

- Employ on-the-fly selection of BLAS-2 vs BLAS-3 matrix operations

- Compute the local MP2 correlation energy from converged amplitudes

This protocol has been shown to provide "roughly an order of magnitude improvement in accuracy" while maintaining computational efficiency [24].

Correlation Matrix Renormalization Protocol

For the CMR method, the following protocol has been established [23]:

Hamiltonian Setup

- Construct the full many-electron Hamiltonian in second quantization

- Identify local correlated orbitals for explicit treatment

Gutzwiller Wavefunction Initialization

- Prepare the non-interacting wavefunction (single Slater determinant)

- Initialize Gutzwiller variational parameters giΓ for local configurations

Correlation Matrix Evaluation

- Extend the Gutzwiller approximation to two-particle operators

- Evaluate the renormalized one-particle density matrix

- Compute the two-particle correlation matrix using CMR approximation

Total Energy Functional Construction

- Apply the Levy-Lieb constrained search method for the total energy

- Include the residual correlation energy functional f(z)

- Determine f(z) by fitting to exact CI results for reference systems

Self-Consistent Solution

- Solve the renormalized HF-like equations

- Optimize local configuration weights {piΓ}

- Iterate until convergence in total energy and density matrix

This approach has been successfully applied to hydrogen clusters, nitrogen clusters, and ammonia molecules, demonstrating "good transferability" of the method [23].

Diagram 2: Local MP2 with Embedding Correction Workflow

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Electron Correlation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Packages | PySCF, ORCA, CFOUR, Molpro | Implement quantum chemistry methods | General quantum chemistry calculations |

| Local Correlation Methods | df-LMP2, DLPNO-CCSD(T), CMR | Enable large-system correlated calculations | Biomolecules, extended systems |

| Basis Sets | cc-pVXZ, aug-cc-pVXZ, def2-XZVPP | Describe spatial distribution of orbitals | Systematic improvement of accuracy |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | cc-pVXZ-RI, def2-XZVPP/C | Density fitting for integral evaluation | Acceleration of two-electron integrals |

| Analysis Tools | Multiwfn, ChemTools Wavefunction analysis | Interpret computational results | Bonding analysis, property calculation |

| High-Performance Computing | MPI, OpenMP, CUDA | Parallelize computations across nodes | Large-scale calculations |

The toolkit for electron correlation research continues to evolve with methodological advances. Recent developments include "non-robust local fitting, sharper occupied/virtual sparse maps, and on-the-fly selection of locally BLAS-2 and BLAS-3 evaluation of matrix-vector products in the conjugate gradient iterations" [24]. These technical improvements, while conceptually specialized, provide critical performance enhancements for production calculations.

The computational scaling problem in electron correlation research remains a central challenge in computational chemistry, particularly for applications in drug development and materials science. While methodological advances in local correlation, density fitting, and novel approaches like CMR have significantly extended the reach of accurate quantum chemistry, fundamental limitations persist for very large systems or those requiring high-level treatment of electron correlation.

Future progress will likely come from multiple directions, including continued algorithmic refinements, hardware advances, and possibly quantum computing. As noted in recent reviews, "Advances in quantum computing are opening new possibilities for chemical modeling. Algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) are being developed to address electronic structure problems more efficiently than is possible with classical computing" [25]. While still in early stages, these approaches may eventually overcome the scaling bottlenecks that limit current methods.

The integration of machine learning with quantum chemistry also shows promise for addressing the accuracy-cost balance. "The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has enabled the development of data-driven tools capable of identifying molecular features correlated with target properties" [25]. These hybrid approaches may provide a path to maintaining accuracy while dramatically reducing computational cost through learned approximations.

For researchers in drug development and molecular sciences, the ongoing advances in scalable electron correlation methods continue to extend the boundaries of systems amenable to accurate quantum chemical treatment. By understanding the scaling relationships and methodological options detailed in this review, scientists can make informed decisions about the appropriate level of theory for their specific applications, balancing the competing demands of accuracy and computational cost.

The Role of Basis Sets in Converging to Accurate Correlation Energies

In ab initio quantum chemistry, the accurate computation of electron correlation energy is fundamental to predicting molecular properties, reaction energies, and spectroscopic behavior with chemical accuracy. The choice of the basis set—a set of mathematical functions used to represent the molecular orbitals—is a critical determinant in the success of these calculations. A basis set must provide a sufficiently flexible and complete expansion to capture the complex electron correlations without rendering computations prohibitively expensive [26]. This guide details the central role of basis sets in converging toward the complete basis set (CBS) limit for correlation energies, a pursuit central to modern electron correlation research for applications ranging from fundamental chemical studies to rational drug design.

The challenge resides in the fact that the exact wavefunction for a many-electron system requires an infinite, complete set of basis functions. In practice, calculations employ a finite basis, introducing a basis set error that must be systematically controlled [26]. The development of correlation-consistent basis sets has provided a systematic pathway for such control, enabling researchers to approach the CBS limit through a hierarchy of basis sets of increasing size and quality. Furthermore, the combination of these basis sets with effective core potentials (ECPs) and core polarization potentials (CPPs) offers a computationally efficient strategy for high-accuracy calculations on systems containing heavier elements [27].

Fundamental Concepts: Basis Sets and Electron Correlation

What is a Basis Set?

A basis set is a set of functions, termed basis functions, used to represent the electronic wave function in methods like Hartree-Fock (HF) and density-functional theory (DFT). This representation turns the partial differential equations of the quantum chemical model into algebraic equations suitable for computational implementation [26]. In the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) approach, molecular orbitals ( \psii ) are constructed as linear combinations of basis functions ( \varphij ): [ \psii = \sumj c{ij} \varphij ] where ( c_{ij} ) are the molecular orbital coefficients determined by solving the Schrödinger equation for the molecule [28].

While Slater-type orbitals (STOs) are physically better motivated and exhibit the correct exponential decay, modern quantum chemistry predominantly uses Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) for computational efficiency, as the product of two GTOs can be expressed as another GTO, simplifying integral evaluation [26] [28]. The smallest basis sets are minimal basis sets (e.g., STO-3G), which use a single basis function for each atomic orbital in a Hartree-Fock calculation on the free atom. These are typically insufficient for research-quality correlation energy calculations [26].

The Challenge of Capturing Correlation Energy

Electron correlation energy is defined as the difference between the exact, non-relativistic energy of a system and its Hartree-Fock energy. Post-Hartree-Fock methods—such as Configuration Interaction (CI), Coupled Cluster (CC), and Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC)—are designed to recover this correlation energy. However, the efficacy of these advanced methods is entirely dependent on the quality of the underlying basis set.

The basis set must be flexible enough to describe the subtle changes in electron distribution that constitute correlation effects. This requires basis functions that can describe:

- Radial Flexibility: The ability of an electron to adjust its average distance from the nucleus.

- Angular Flexibility: The ability to describe changes in the shape of electron clouds, which is achieved by adding functions with higher angular momentum (polarization functions).

- Diffuse Electron Density: The "tails" of electron distributions, particularly important for anions, excited states, and weak intermolecular interactions, which require diffuse functions with small exponents [26] [29].

Without a sufficient number of functions of the correct types, the basis set itself becomes the limiting factor in accuracy, no matter how sophisticated the electron correlation method employed.

Systematic Pathways to the Complete Basis Set Limit

The Correlation-Consistent Basis Set Hierarchy

The most widely used systematic approach for converging to the CBS limit for correlation energies is the family of correlation-consistent basis sets developed by Dunning and coworkers [26] [27]. These are denoted as cc-pVnZ, where n stands for the level of zeta (D, T, Q, 5, 6). The key design principle is that functions are added in sets (or "tiers") that contribute similar amounts to the correlation energy, ensuring a systematic and monotonic convergence of the energy as n increases [27].

Table 1: Composition of Standard Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets (cc-pVnZ) for First-Row Atoms (B-Ne) [30]

| Basis Set | Zeta Level | s-Functions | p-Functions | d-Functions | f-Functions | Total Functions (H) | Total Functions (C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cc-pVDZ | Double-Zeta (DZ) | 2s | 2p | 1d | - | 5 | 14 |

| cc-pVTZ | Triple-Zeta (TZ) | 3s | 3p | 2d | 1f | 14 | 30 |

| cc-pVQZ | Quadruple-Zeta (QZ) | 4s | 4p | 3d | 2f | 30 | 55 |

| cc-pV5Z | Quintuple-Zeta (5Z) | 5s | 5p | 4d | 3f | 55 | 91 |

For second-row atoms (Al-Ar), it was discovered that standard correlation-consistent basis sets exhibited deficiencies, particularly for molecules with atoms in high oxidation states. This led to the development of the cc-pV(n+d)Z basis sets, which include additional tight (large-exponent) d-functions that act as "inner polarization functions" to improve the description of electron correlation [27]. It is now recommended that for second-row p-block elements, only these "plus d" sets should be used, as the minor increase in basis function count is offset by a significant gain in accuracy [27].

To accurately model anions, dipole moments, polarizabilities, and Rydberg states, the standard cc-pVnZ basis sets can be augmented with diffuse functions, forming the aug-cc-pVnZ basis sets [26] [29]. For properties like hyperpolarizabilities or high-lying excitation energies, even more diffuse functions may be necessary [29].

Effective Core Potentials and Accompanying Basis Sets

To reduce computational cost, particularly for heavier elements, the core electrons can be replaced with an Effective Core Potential (ECP) or Pseudopotential (PP). This removes the need for basis functions to describe core electrons and can incorporate scalar relativistic effects [27]. Recent work has focused on developing new correlation-consistent ECPs (ccECPs) using full many-body approaches for superior accuracy in correlated methods [31] [27].

These ccECPs require specially optimized basis sets. For example, the newly developed cc-pV(n+d)Z-ccECP basis sets for Al-Ar atoms paired with the neon-core ccECPs have been shown to produce results in close agreement with all-electron calculations, providing a computationally efficient and accurate alternative [27].

Core-Correlation and Core Polarization

For the highest levels of accuracy (e.g., within 1 kJ/mol), the correlation effects of core electrons (core-valence correlation) must be considered. Specialized core-valence basis sets (cc-pCVnZ) are optimized to capture these effects by including additional tight basis functions [27].

A computationally efficient alternative to explicitly correlating all electrons is the use of a Core Polarization Potential (CPP). This approach accounts for the dynamic polarization of the atomic core by the valence electrons. The CPP is an additive potential that depends on the core dipole polarizability and the electric field generated by valence electrons and other cores [27]. The combination of ccECPs and CPPs has been demonstrated as an accurate and efficient strategy for high-level quantum chemistry [27].

Methodologies for Practical Convergence

Complete Basis Set (CBS) Extrapolation

It is often computationally infeasible to perform calculations with a basis set large enough to reach the true CBS limit. A powerful and widely used technique is CBS extrapolation, where calculations are performed with two or more basis sets in the cc-pVnZ hierarchy (e.g., TZ and QZ), and their energies are used to estimate the energy at the CBS limit using empirical mathematical formulas [31] [32]. This allows for a significant reduction in computational cost while achieving accuracy comparable to that of the next larger basis set.

Mixed Basis Sets

In large molecules, it is common and acceptable practice to use a higher-level basis set on the chemically active region (e.g., the reaction center in a catalyst or the chromophore in a spectroscopy calculation) and a smaller, more efficient basis set on the surrounding atoms [32]. For instance, a triple-zeta basis might be used on a metal center and its immediate ligands, while a double-zeta basis is used on the peripheral atoms.

This strategy is supported by the concept of "basis set sharing," where each atom benefits from the basis functions on its neighbors, mitigating the error from using a smaller basis set on individual atoms [29]. The primary drawback of this approach is that it complicates or prevents the use of systematic CBS extrapolation for the entire molecule [32].

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting a basis set strategy, balancing accuracy and computational cost.

Protocols for High-Accuracy Energy Calculations

The following protocols outline detailed methodologies for achieving highly accurate correlation energies, as cited in recent literature.

Protocol for Atomic Correlation Energy Benchmarks

This protocol, based on the work generating reference data for ccECPs, aims to establish exact or near-exact total energies for atoms [31].

- Method Hierarchy: Employ a hierarchy of high-level correlated wavefunction methods. A typical sequence is:

- Coupled-Cluster with Singles, Doubles, and perturbative Triples (CCSD(T))

- Coupled-Cluster with Singles, Doubles, and Triples (CCSDT)

- Coupled-Cluster with Singles, Doubles, Triples, and perturbative Quadruples (CCSDT(Q))

- Basis Set Progression: Perform calculations with the

cc-pVnZbasis sets, typically from n=D (double-zeta) to n=6 (sextuple-zeta). - CBS Estimation: Use the results from the largest feasible basis sets (e.g., n=5 and n=6) to estimate the complete basis set limit energy.

- Cross-Validation: Validate the coupled-cluster energies against highly accurate results from an independent method, such as Fixed-Node Diffusion Monte Carlo (FN-DMC), to quantify potential biases like the fixed-node error [31].

Using such a combination of methods, researchers have achieved benchmark total energies with an accuracy of approximately 0.1-0.3 milliHartree for light elements and 1-10 milliHartree for transition metals (K-Zn), representing about 1% or better of the total correlation energy [31].

Protocol for Molecular Energy Calculations using ccECPs and CPPs

This protocol is adapted from recent work on second-row elements (Al-Ar) and is designed for efficient and accurate molecular property calculations [27].

- Hamiltonian Selection: Choose the appropriate correlation-consistent Effective Core Potential (

ccECP) to replace the core electrons (e.g., a neon-coreccECPfor Al-Ar). - Basis Set Selection: Use the corresponding

cc-pV(n+d)Z-ccECPbasis set, which includes the crucial tight d-functions for second-row elements. - Core Polarization: If core-valence correlation effects are significant for the target property, add a Core Polarization Potential (CPP). The CPP parameters (core polarizability

α_λand cutoff parameterγ) are typically pre-optimized for the specificccECP[27]. - Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform the calculation at the Coupled-Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) level of theory.

- Benchmarking: Compare the obtained molecular properties (e.g., atomization energies, bond lengths) against reliable all-electron reference data to validate the accuracy of the

ccECP/basis set/CPP combination [27].

Table 2: Essential Research "Reagents" for Accurate Correlation Energy Calculations

| Item / Basis Set | Type | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| cc-pVnZ [26] | All-Electron Basis Set | Systematic convergence to CBS limit for main-group elements. | Hierarchical, correlation-consistent design. Includes polarization functions. |

| aug-cc-pVnZ [26] [29] | Diffuse-Augmented Basis Set | Accurate description of anions, excited states, and weak interactions. | Standard cc-pVnZ set with added diffuse functions of each angular momentum. |

| cc-pCVnZ [27] | Core-Valence Basis Set | Capturing core-valence electron correlation effects. | Includes extra tight functions to correlate core electrons. |

| ccECP [31] [27] | Effective Core Potential | Replaces core electrons, reducing cost and adding relativistic effects. | Developed using many-body methods for accuracy in correlated calculations. |

| cc-pV(n+d)Z-ccECP [27] | ECP-Optimized Basis Set | Used with ccECPs for accurate valence calculations. |

Includes tight d-functions vital for second-row elements. |

| Core Polarization Potential (CPP) [27] | Additive Potential | Accounts for core-valence correlation effects efficiently. | Models polarization of the core by valence electrons; avoids full core correlation. |

Diagram 2: The methodology of Complete Basis Set (CBS) extrapolation. Energies calculated with a sequence of basis sets are used as input to an empirical mathematical function to estimate the energy at the CBS limit.

Current Research and Outlook

The field of basis set development continues to evolve, driven by the demands of new scientific applications and computational hardware. Current research directions include:

- Refinement of ccECPs and Basis Sets: Ongoing work focuses on expanding and refining correlation-consistent ECPs and their accompanying basis sets across the periodic table, ensuring high accuracy for heavy elements at a reduced computational cost [31] [27].

- High-Accuracy Benchmark Databases: There is a push to create large, publicly available datasets of high-accuracy molecular properties computed with robust methods and large basis sets. These datasets, like the OE62 database of molecular orbital energies, serve as invaluable benchmarks for developing new methods, including machine learning potentials [33].

- Optimal Balance for Large Systems: Research continues into finding the optimal balance between basis set size, the use of mixed schemes, and the incorporation of ECPs for application in large, biologically relevant molecules and materials, which is of direct interest to drug development professionals [29] [32].

In conclusion, the strategic selection and use of basis sets remain a cornerstone of ab initio quantum chemistry. The systematic correlation-consistent hierarchy provides a clear pathway to converge to accurate correlation energies, while modern approaches involving ECPs and CPPs extend the reach of high-accuracy calculations to larger and more complex systems, directly impacting research in catalysis, materials science, and pharmaceutical development.

Computational Methods for Electron Correlation: From Theory to Drug Design Practice

The Hartree-Fock (HF) method provides the foundational wavefunction approximation in quantum chemistry, but it fails to capture electron correlation, the instantaneous repulsive interactions between electrons that are neglected in its mean-field approach. This missing correlation energy, typically around 1.1 eV per electron pair, is chemically significant and crucial for accurate predictions [34]. Post-Hartree-Fock methods systematically address this limitation by adding electron correlation effects to the HF reference, enabling more accurate computational predictions of molecular properties, reaction energies, and spectroscopic behavior [22] [35].

The correlation energy is formally defined as the difference between the exact solution of the non-relativistic electronic Schrödinger equation and the Hartree-Fock energy: (E{\text{corr}} = E{\text{exact}} - E_{\text{HF}}) [34]. This missing energy component can be partitioned into dynamic correlation, arising from the correlated motion of electrons avoiding each other, and static correlation, which occurs in systems with significant multi-reference character where a single determinant provides a qualitatively incorrect description [35]. Different post-HF methods address these correlation types with varying effectiveness and computational cost.

This technical guide examines three cornerstone families of post-Hartree-Fock ab initio methods: Configuration Interaction (CI), which constructs the wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants; Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MPn), which treats electron correlation as a perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian; and Coupled-Cluster (CC), which uses an exponential ansatz to ensure size consistency and systematic improvability [36] [37] [38]. These methods represent the essential toolkit for accurate electron correlation treatment in computational chemistry, each with distinct theoretical foundations, computational characteristics, and application domains relevant to chemical research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations

Configuration Interaction (CI)

The Configuration Interaction method approaches the electron correlation problem by constructing a multi-determinant wavefunction. The CI wavefunction, ( \Psi{\text{CI}} ), is expressed as a linear combination of the Hartree-Fock reference determinant, ( \Phi0 ), and various excited determinants generated by promoting electrons from occupied to virtual orbitals [36]:

[

\Psi{\text{CI}} = c0 \Phi0 + \sum{i,a} ci^a \Phii^a + \sum{i