Advanced Strategies for Lattice Parameter Optimization in Periodic Systems: From Quantum Computing to Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review explores cutting-edge strategies for optimizing lattice parameters in periodic systems, addressing critical challenges in materials science and biomedical engineering.

Advanced Strategies for Lattice Parameter Optimization in Periodic Systems: From Quantum Computing to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores cutting-edge strategies for optimizing lattice parameters in periodic systems, addressing critical challenges in materials science and biomedical engineering. We examine foundational principles of periodic and stochastic lattice structures, methodological advances including quantum annealing-assisted optimization and evolutionary algorithms, practical troubleshooting for manufacturing constraints, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs in conformal optimization frameworks, quantum computing applications, and shape optimization for triply periodic minimal surfaces, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a multidisciplinary toolkit for enhancing structural performance, energy absorption, and biomimetic properties in engineered materials and biomedical implants.

Fundamental Principles of Lattice Structures and Periodic System Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a periodic and a stochastic lattice structure?

A1: A periodic lattice structure consists of a single, repeating unit cell (e.g., cubic, TPMS) arranged in a regular, predictable pattern throughout the volume. In contrast, a stochastic lattice structure (e.g., Voronoi, spinodoid) features a random, non-repeating distribution of struts or cells, more closely mimicking the irregular architecture of natural materials like bone or foam [1] [2] [3].

Q2: For a biomedical implant aimed at promoting bone ingrowth, which lattice type is generally more suitable?

A2: Stochastic lattices are often favored for bone-matching mechanical properties and enhancing osseointegration. Their random pore distribution can better mimic the structure of natural trabecular bone, promoting biological fixation. Furthermore, a single stochastic design can be tuned to achieve a broad range of stiffness and strength, simplifying the design process for implants that require property gradients [2] [4].

Q3: My application requires high specific energy absorption. What should I consider when choosing a lattice type?

A3: The choice depends on the performance priorities. Stochastic Voronoi lattices can achieve high specific energy absorption (SEA), with studies showing an optimal relative density of around 25% for polymer-based structures under impact [3]. However, certain periodic lattices, like the Primitive TPMS, can exhibit superior perforation resistance and peak load capacity due to high out-of-plane shear strength, which may be critical for sandwich panel applications [1].

Q4: How does the manufacturing process influence the choice between periodic and stochastic lattices?

A4: Additive manufacturing (AM) is essential for fabricating both types, but considerations differ. Periodic TPMS lattices have continuous, smooth surfaces that minimize stress concentrations and are often more self-supporting during metal AM, reducing the need for supports [5]. For stochastic lattices manufactured via polymer Powder Bed Fusion (PBF), a key limitation is depowdering; the relative density must be controlled to ensure loose powder can be removed from the intricate, random internal channels [3].

Q5: Can the mechanical properties of a stochastic lattice be predicted and controlled as reliably as those of a periodic lattice?

A5: While periodic lattices have well-defined structure-property relationships, stochastic lattices can also be systematically controlled. Key parameters like strut density, strut thickness, and nodal connectivity directly influence mechanical behavior. For example, increasing connectivity in a stochastic titanium lattice can shift deformation from bend-dominated to stretch-dominated and increase fatigue strength by up to 60% [4]. Unified models can predict properties based on these parameters [4] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Mechanical Performance in Stochastic Lattice Specimens

Problem: Test results show high variability between stochastically lattice specimens that were designed to be identical.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled random seed. | Verify if the algorithm uses a fixed seed for point generation. | Use a fixed random seed during the Voronoi or other stochastic generation process to ensure consistency across all designs [3]. |

| Low node connectivity. | Analyze the nodal connectivity of the generated structure. | Increase the average connectivity of the lattice. Structures with higher connectivity (e.g., from 4 to 14) demonstrate more stretch-dominated, predictable behavior and higher fatigue strength [4]. |

| Manufacturing defects in thin struts. | Inspect struts via microscopy for porosity or incomplete fusion. | Increase the minimum strut diameter above the printer's reliable capability (e.g., > 0.7 mm for SLS with PA12) and optimize process parameters for the specific material [3]. |

Issue: Periodic Lattice Structure Failing at Sharp Joints

Problem: Failure analysis reveals cracks initiating at the junctions between unit cells in a strut-based periodic lattice.

Solution: Transition to a Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) lattice design. TPMS structures, such as Gyroid or Primitive, are composed of smooth, continuous surfaces with no sharp corners or abrupt transitions. This inherent geometry eliminates stress concentrations at joints, leading to enhanced structural integrity and a reduced risk of premature fatigue failure [5].

Issue: Poor Osseointegration with a Stiff, Periodic Lattice Implant

Problem: A patient-specific orthopedic implant with a periodic lattice is causing stress shielding and shows limited bone ingrowth.

Action Plan:

- Re-evaluate Lattice Type: Consider switching to a stochastic trabecular lattice design that more closely mimics the random, interconnected porosity of natural cancellous bone, which is proven to enhance bone ingrowth and biological fixation [2].

- Optimize Mechanical Properties: Use a stochastic lattice model where a single relationship between design parameters (connectivity, strut density, thickness) and mechanical properties exists. This allows for precise tuning of the stiffness and strength gradient within the implant to match the surrounding bone, thereby reducing stress shielding [4].

- Consider a Hybrid Approach: Explore a functionally graded structure that uses a stochastic lattice at the bone-implant interface to promote osseointegration and a stronger, more predictable periodic lattice in the core for load-bearing [2] [7].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies on periodic and stochastic lattice structures.

Table 1: Comparative Mechanical Properties under Impact and Static Loading

| Lattice Type | Key Finding | Test Conditions | Performance Data | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodic Primitive TPMS | Highest perforation limit | Low-velocity impact on sandwich structures with composite skins | Excellent perforation resistance due to high out-of-plane shearing strength [1] | |

| Stochastic GRF Spinodoid | Highest peak load | Low-velocity impact on sandwich structures with composite skins | High peak load due to anisotropic properties [1] | |

| Stochastic Voronoi (Polymer) | Optimal Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) | Drop tower impact test at 5 m/s (PA12 material) | Highest SEA at 25% relative density; best performance with small strut diameter & high number of struts [3] | |

| Stochastic (Titanium) | Fatigue strength increase | Quasi-static and fatigue compression testing | Increasing connectivity from 4 to 14 increased fatigue strength by 60% for a fixed relative density [4] | |

| Shape-Optimized TPMS | Stiffness & Strength Enhancement | Uniaxial compression test (Ti-42Nb alloy) | Stiffness increase up to 80% and strength increase up to 61% [8] |

Table 2: Design and Manufacturing Considerations

| Aspect | Periodic Lattices | Stochastic Lattices |

|---|---|---|

| Property Predictability | High; defined by unit cell type [9] | Moderate; requires control of density, connectivity, and strut thickness [4] |

| Typical Relative Density Control | Varying cell size and/or beam/surface thickness [3] | Varying strut diameter and density of seed points [3] |

| Biomimicry | Ordered structures (e.g., honeycombs) | Excellent for trabecular bone and natural foams [2] |

| Stress Concentration | Can be high at sharp cell junctions | More evenly distributed, damage-tolerant [1] |

| Key Manufacturing Challenge | Support structures for overhangs in strut-based designs [5] | Depowdering in PBF processes; max density is limited [3] |

| Design Flexibility | Different unit cells needed for different properties [4] | A single design can achieve a wide property range by tuning parameters [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quasi-Static Compression Testing for Lattice Property Characterization

Objective: To determine the effective stiffness, strength, and deformation behavior of lattice structures.

Specimen Fabrication:

- Manufacturing Method: Utilize Laser Powder Bed Fusion (PBF) for metals or Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) for polymers to manufacture lattice specimens [3] [4].

- Specimen Geometry: Design cubic or cylindrical specimens with a sufficient number of unit cells or stochastic cells (e.g., 5x5x5) to mitigate boundary effect issues. A common size is 30x30x30 mm³ [3].

- Post-Processing: Condition polymer specimens in a standard climate (e.g., 22°C and 50% relative humidity) for at least one week [3]. For metal parts, stress relief annealing may be necessary.

Test Setup:

- Equipment: Use a standard universal testing machine.

- Fixturing: Place the specimen between two parallel, rigid platens. Ensure the top and bottom surfaces of the lattice are flat and parallel to the platens.

- Data Acquisition: Fit the machine with a calibrated load cell and an extensometer or use the machine's crosshead displacement (with compensation for machine compliance) to measure strain.

Procedure:

- Load the specimen at a constant crosshead displacement rate to achieve a quasi-static strain rate (e.g., 0.01 mm/mm/min).

- Record the load and displacement data continuously until the specimen is fully densified.

- Perform a minimum of three replicates for each lattice design to ensure statistical significance.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate engineering stress by dividing the load by the original cross-sectional area of the specimen.

- Calculate engineering strain by dividing the displacement by the original height.

- From the stress-strain curve, determine the effective elastic modulus (slope in the initial linear region), yield strength (via offset method), and energy absorption (area under the curve up to densification strain).

Protocol 2: Drop Tower Impact Test for Energy Absorption Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the energy absorption capabilities of lattice structures under dynamic loading conditions representative of real-world impacts.

Specimen Design & Fabrication: Follow the same steps as Protocol 1.

Test Setup:

- Equipment: Use a drop tower test rig. A self-built unit is acceptable if properly instrumented [3].

- Instrumentation: Instrument the rig with a force sensor (e.g., Kistler 9041) at the base and an accelerometer (e.g., B&J type 4375) on the impactor.

- Impact Velocity: Set the drop height to achieve the desired impact velocity (e.g., 5 m/s, as used in bicycle helmet standards) [3].

Procedure:

- Secure the lattice specimen on the anvil of the drop tower.

- Release the impactor from the predetermined height.

- Use data acquisition hardware (e.g., Kistler 5011 charge amplifier) to record the force-time and acceleration-time histories during the impact event.

Data Analysis:

- Integrate the acceleration signal to obtain velocity and displacement.

- Calculate the energy absorbed by the specimen as the area under the force-displacement curve.

- Calculate the Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) by dividing the total absorbed energy by the mass of the lattice specimen [3].

Research Workflow and Decision Pathway

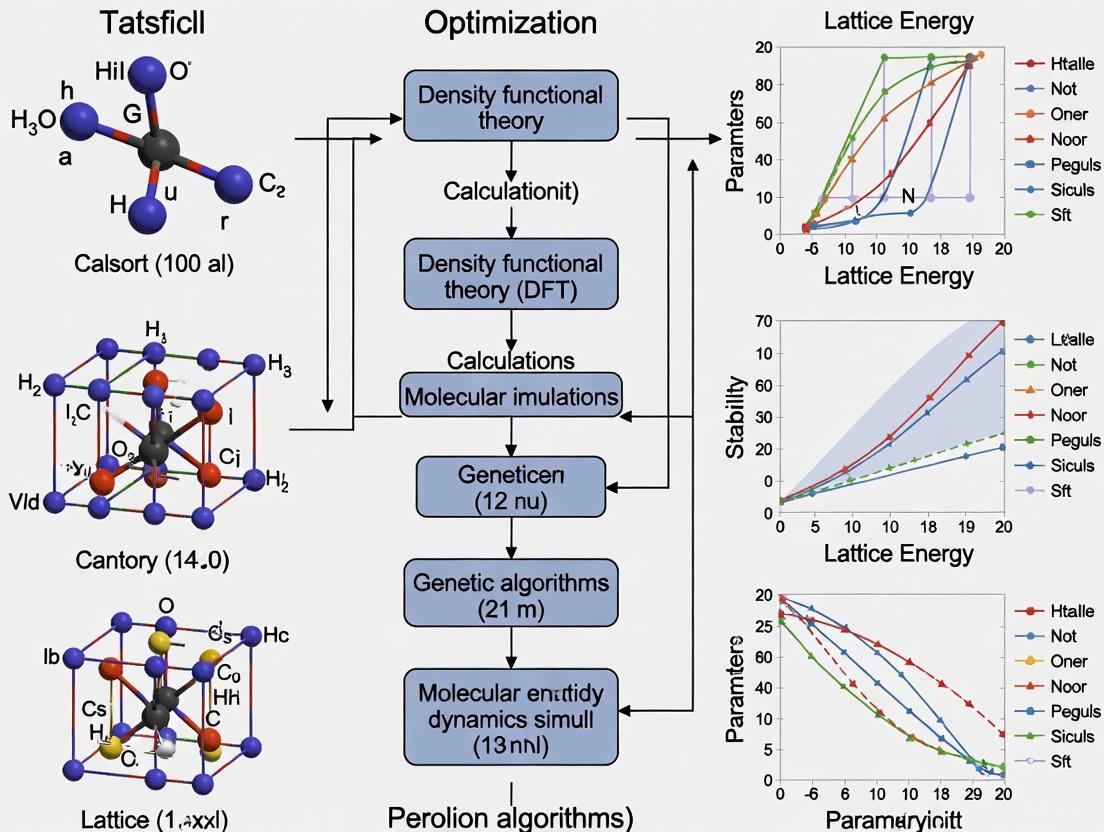

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and optimizing a lattice structure for a specific application, based on performance requirements and constraints.

Lattice Structure Selection and Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials, Software, and Equipment for Lattice Research

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Modeling Tools | ||

| Rhino 3D with Grasshopper | A versatile CAD and algorithmic modeling environment for generating both stochastic (e.g., Voronoi) and periodic lattice structures [3] [6]. | The "Dendro" plugin is used to thicken struts. The pseudo-random point distribution tool generates stochastic seeds [3]. |

| nTopology | An advanced engineering design platform for generating and working with complex lattice structures and TPMS, enabling field-driven design and optimization [9]. | Well-suited for creating property-graded lattices and handling large, complex models efficiently [9]. |

| Additive Manufacturing Equipment | ||

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | A powder bed fusion process ideal for fabricating complex polymer lattice structures without support [3]. | Commonly used material: Polyamide 12 (PA12/Nylon 12). A key limitation is depowdering for dense stochastic lattices [3]. |

| Laser Powder Bed Fusion (L-PBF) | A metal AM process for creating high-strength, dense metal lattice structures from alloys like Ti-6Al-4V, Ti-42Nb, and pure Titanium [4] [8] [5]. | Enables fabrication of intricate TPMS and stochastic lattices for biomedical and aerospace applications. |

| Characterization & Testing Equipment | ||

| Universal Testing Machine | For conducting quasi-static compression and tensile tests to determine fundamental mechanical properties [4]. | Used to establish stress-strain curves, elastic modulus, yield strength, and collapse strength. |

| Drop Tower Test Rig | For evaluating the energy absorption and dynamic impact response of lattice structures at high strain rates [3]. | Should be instrumented with a force sensor (e.g., Kistler) and accelerometer. |

| Research Materials | ||

| Polyamide 12 (PA2200) | A common polymer for SLS printing, offering good mechanical properties and accuracy for lattice research [3]. | Material used in establishing specific energy absorption (SEA) benchmarks for stochastic Voronoi lattices [3]. |

| Titanium Alloys (Ti-6Al-4V, Ti-42Nb) | Biocompatible metals with excellent mechanical properties for load-bearing biomedical implants and aerospace components [2] [8]. | Ti-42Nb is a beta-type alloy with a low elastic modulus, making it particularly suitable for bone implants [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers working on the optimization of lattice parameters in periodic systems. The following guides and FAQs address common experimental challenges related to characterizing and improving energy absorption, thermal, and acoustic properties.

Energy Absorption

Problem: Inconsistent or Low Energy Absorption Results

- Symptom: Lattice structures exhibit catastrophic failure instead of stable, progressive collapse, leading to low specific energy absorption (SEA) values.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Suboptimal Cell Geometry. The selected lattice cell type (e.g., BCC, FCC, IsoTruss) may not be suited for energy absorption.

- Solution: Re-evaluate cell geometry. Research shows that IsoTruss configurations with linear density gradients can achieve energy absorption up to 15 MJ/m³ before 44% strain, significantly outperforming basic FCC structures [10]. Consider bioinspired designs, like those with asymmetric cambered cell walls, which have shown a 558.4% increase in specific energy absorption over straight-wall designs [11].

- Cause 2: Inadequate Density Gradient.

- Solution: Implement a graded density design. Uniform density often leads to simultaneous failure. Linear or quadratic density variations from the center to the outer diameter of a sample can promote sequential collapse and higher energy absorption [10].

- Cause 3: Manufacturing Defects. Pores and surface defects from additive manufacturing act as stress concentrators.

- Solution: Optimize laser processing parameters. For LPBF of Ti6Al4V, parameters like 250W laser power and 1000-1200 mm/s scan speed have been shown to minimize porosity to below 0.01% [12]. Conduct micro-CT scanning to characterize defects and validate printer settings.

- Cause 1: Suboptimal Cell Geometry. The selected lattice cell type (e.g., BCC, FCC, IsoTruss) may not be suited for energy absorption.

Problem: Difficulty in Predicting Mechanical Performance

- Symptom: Experimental results for modulus of elasticity and yield stress deviate significantly from initial simulations.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Simulation Model Does Not Account for Defects.

- Solution: Utilize advanced material models in simulations. The Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman (GTN) model, which incorporates porosity, has been demonstrated to accurately predict damage evolution and final fracture locations in Ti6Al4V lattice structures [12].

- Cause: Simulation Model Does Not Account for Defects.

Acoustic Characteristics

Problem: Poor Low-Frequency Sound Absorption

- Symptom: Material performs well at high frequencies but fails to absorb sound below 1000 Hz.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Material is Too Thin. The thickness of the sound-absorbing structure is a key factor determining its low-frequency limit.

- Solution: Consider cavity-type metamaterials. For example, a design with a 60mm thickness can achieve continuous near-perfect absorption from 450–1360 Hz [13]. For stricter thickness constraints, ultra-thin metasurfaces (23mm) using phase-coherent cancellation can achieve an average absorption coefficient of 0.8 between 600-1300 Hz [13].

- Cause 2: Reliance on Porous Materials Alone.

- Solution: Integrate resonant structures. Designs incorporating heterogeneous multilayered resonators, inspired by biological structures like cuttlebone, have demonstrated an average absorption coefficient of 0.80 from 1.0 to 6.0 kHz with a compact 21mm thickness [11]. Helmholtz resonators and Fabry-Pérot cavities can be tuned to target specific low-frequency bands.

- Cause 1: Material is Too Thin. The thickness of the sound-absorbing structure is a key factor determining its low-frequency limit.

Problem: Trade-off Between Acoustic Absorption and Mechanical Strength

- Symptom: A material with excellent sound absorption is mechanically weak, and vice versa.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Monofunctional Design Approach.

- Solution: Employ a decoupled or multifunctional design strategy. Bioinspired architected metamaterials (MBAMs) use a "weakly-coupled design" where acoustic elements feature heterogeneous resonators, and mechanical responses are based on asymmetric cambered cell walls. This allows for simultaneous high sound absorption and specific energy absorption of 50.7 J/g [11].

- Cause: Monofunctional Design Approach.

Thermal Characteristics

Problem: High Thermal Conductivity in Insulation Materials

- Symptom: Lattice or composite insulation panels do not achieve target thermal resistance.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Material Selection and Density.

- Solution: Utilize sustainable materials with naturally low thermal conductivity. Panels made from recycled cardboard have shown thermal conductivity coefficients between 0.049 and 0.054 W/m·K [14]. Other natural materials like hemp, sheep's wool, and flax also offer competitive thermal performance [15].

- Cause: Material Selection and Density.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key lattice parameters I should focus on optimizing for multifunctional performance? A1: The most critical parameters are cell topology (e.g., IsoTruss, Diamond, FCC), relative density, and density gradient. The optimal combination is application-dependent. For energy absorption, IsoTruss with a linear density gradient is promising [10]. For coupled acoustic-mechanical performance, bioinspired topologies with cambered walls are superior [11].

Q2: My acoustic metamaterial design is complex and simulation is time-consuming. How can I accelerate the design process? A2: Machine learning (ML) offers a solution. Trained neural networks can replace slow simulations by discovering non-intuitive relationships between geometric parameters and performance [13]. For instance, autoencoder-like neural networks (ALNN) can enable non-iterative, customized design of structural parameters based on a target sound absorption curve [13].

Q3: Are sustainable materials a viable alternative for high-performance acoustic and thermal insulation? A3: Yes. Materials such as recycled cotton, sheep's wool, cork, and recycled cardboard offer excellent thermal and acoustic properties, often comparable to conventional materials [16] [15] [14]. They provide the added benefits of low embodied carbon, renewability, and contribution to a circular economy.

Q4: How can I accurately model the relaxation of crystal structures in my material simulations? A4: Traditional DFT is computationally intensive. Emerging end-to-end equivariant graph neural networks like E3Relax can directly map an unrelaxed crystal to its relaxed structure, simultaneously modeling atomic displacements and lattice deformations with high accuracy and efficiency [17].

Table 1: Mechanical and Acoustic Performance of Selected Lattice Structures and Metamaterials

| Material / Structure | Fabrication Method | Key Mechanical Property | Key Acoustic Property | Density | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti6Al4V FCCZ Lattice | Laser Powder Bed Fusion | Ultimate Tensile Strength: 140.71 MPa | N/A | N/A | [12] |

| Bioinspired Architected Metamaterial (MBAM) | Selective Laser Melting (Ti6Al4V) | Specific Energy Absorption: 50.7 J/g | Avg. Absorption Coeff. (1-6 kHz): 0.80 | 1.53 g/cm³ | [11] |

| IsoTruss Configuration (Linear Density) | Stereolithography | Energy Absorption: ~15 MJ/m³ (at 44% strain) | N/A | N/A | [10] |

Table 2: Performance of Sustainable Insulation Materials

| Material | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | Sound Absorption Performance | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled Corrugated Cardboard Panels | 0.049 - 0.054 | Low-frequency peak at 1000 Hz; can be improved with perforations [14] | Interior wall panels, sustainable construction [14] |

| Recycled Cotton Insulation | Competitive R-value with fiberglass | Excellent sound absorption [16] | Interior walls, ceilings, floors [16] |

| Sheep's Wool Insulation | Effective thermal insulator | Effective across a broad frequency range [16] | Residential homes, historic buildings [16] |

| Hempcrete | Good thermal insulation | Moderate soundproofing benefits [16] | Wall construction, insulation panels [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Compression Testing and Energy Absorption Analysis for Lattice Structures

Objective: To determine the modulus of elasticity, yield stress, and specific energy absorption (SEA) of additively manufactured lattice structures.

- Specimen Fabrication: Fabricate lattice specimens using the chosen AM process (e.g., SLA, SLM). Record all parameters: laser power, scan speed, layer thickness, and build orientation [12] [10].

- Specimen Preparation: Measure the exact dimensions and mass of each specimen. Calculate the apparent density.

- Micro-CT Scanning (Optional but Recommended): Characterize the as-built structure for pore defects and dimensional accuracy using X-ray tomography [12].

- Mechanical Testing: Perform a quasi-static compression test using a universal testing machine according to ASTM D1621-16.

- Data Analysis:

- From the stress-strain curve, calculate the modulus of elasticity (slope of the initial linear region) and yield stress.

- Calculate the Specific Energy Absorption (SEA) by integrating the stress-strain curve up to a designated strain (e.g., 50% strain): ( SEA = \frac{\int_{0}^{\epsilon} \sigma d\epsilon}{\rho} ), where ( \sigma ) is stress, ( \epsilon ) is strain, and ( \rho ) is density.

Protocol 2: Impedance Tube Measurement for Sound Absorption Coefficient

Objective: To measure the normal incidence sound absorption coefficient of a material sample according to the ASTM E1050 standard.

- Specimen Preparation: Cut the test material to the precise diameter required by the impedance tube.

- Setup Calibration: Mount the specimen firmly in the tube. Perform system calibration using the standard method (e.g., transfer function method between two microphones).

- Acoustic Measurement: A loudspeaker generates broadband white noise. Microphones measure the incident and reflected sound pressure levels.

- Data Processing: Software calculates the sound absorption coefficient (( \alpha )) as a function of frequency, where ( \alpha = 1 - |r|^2 ), and ( r ) is the complex reflection coefficient.

- Validation: For large-scale samples or irregular incidence, validate results in a reverberation chamber [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Lattice and Metamaterial Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ti6Al4V Alloy Powder | Raw material for high-strength, corrosion-resistant metal lattice structures via LPBF. | Used in fabricating lattice structures for aerospace and biomedical implants [12] [11]. |

| Photopolymer Resin | Raw material for creating high-resolution polymer lattice structures via Stereolithography (SLA). | Used for rapid prototyping and testing of complex lattice geometries [10]. |

| Selective Laser Melting (SLM) System | Additive manufacturing equipment for fabricating full-density metal parts from powder. | Enables creation of complex, high-strength metal lattices [12] [11]. |

| Stereolithography (SLA) Printer | Additive manufacturing equipment using UV light to cure liquid resin into solid polymer. | Ideal for fabricating detailed polymeric lattice structures for mechanical testing [10]. |

| Universal Testing Machine | Used for determining mechanical properties under tension, compression, and bending. | Critical for generating stress-strain curves and calculating energy absorption [12] [10]. |

| Impedance Tube | Measures the normal incidence sound absorption coefficient of materials. | Standard tool for acoustic characterization of metamaterials and porous absorbers [13] [11]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Provides high-resolution microstructural imaging and surface defect analysis. | Used to examine strut surfaces, fracture modes, and manufacturing quality [12] [10]. |

Methodology and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Lattice Parameter Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Multifunctional Performance Relationship Map

Design for Additive Manufacturing (DFAM) Paradigm for Complex Geometries

FAQ: DFAM Fundamentals for Lattice Structures

This section addresses frequently asked questions about the core principles of designing lattice structures for Additive Manufacturing, framed within a research context focused on periodic systems.

Q1: What is DFAM, and why is it critical for manufacturing lattice structures in research? Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) is the methodology of creating, optimizing, or adapting a part to take full advantage of the benefits of additive manufacturing processes [18]. For lattice structures, which are a class of architected materials with tailored mechanical, thermal, or biological responses, DfAM is essential. It provides a framework to ensure these highly complex geometries are not only designed for performance but are also manufacturable, functionally validated, and stable [19] [18]. This is paramount in research to ensure that experimental results reflect the designed properties of the lattice and not manufacturing artifacts.

Q2: What are the key phases in a DFAM framework for developing new lattice parameters? A robust DfAM process for lattice development can be broken down into three iterative phases [19]:

- Fabrication: Characterizing the AM process and material to understand printability constraints, such as minimum feature size and the effect of orientation on properties.

- Generation: Creating the lattice design through conceptualization, configuration, and optimization (e.g., using topology optimization) to meet specific stiffness, stability, or other functional targets.

- Assessment: Validating the printed lattice through computational modeling (e.g., Finite Element Analysis), mechanical testing, and microscopy to verify performance and inform design iterations.

Q3: How can topology optimization be used to design lightweight periodic lattices? Topology optimization is a computational design process that seeks to produce an optimal material distribution within a given design space based on a set of constraints [18]. For lightweight lattices, it can be used to minimize relative density while constraining for performance targets like stiffness and stability to prevent buckling [20]. This allows researchers to generate novel, high-performance unit cell designs that go beyond conventional geometries like Kagomé or tetrahedral lattices.

Q4: What are the advantages of part consolidation in assemblies using lattices? A key advantage of AM is the ability to consolidate multiple components into a single, complex part. Integrating lattices enables this by replacing solid sections with lightweight, functional structures. This can lead to weight reduction (by eliminating fasteners), reduced assembly costs, and increased reliability by minimizing potential points of failure [18].

Q5: Which software tools are commonly used for advanced DFAM? Traditional CAD programs can struggle with the complex geometries of lattices. Advanced engineering software like nTop, built on implicit modeling, is specifically designed to overcome these bottlenecks. It provides capabilities for field-driven design (granular control over lattice properties) and workflow automation, which is essential for mass customization and parametric studies [18].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Lattice Printing Issues

The following table outlines common problems encountered when 3D printing lattice structures, their likely causes, and detailed solutions for researchers.

| Issue & Image | Issue Details | Cause & Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failed Lattice Struts | Thin struts are missing, broken, or incomplete. The lattice appears distorted or has holes. | Cause 1: Insufficient Minimum Feature Size. Strut diameter is below the printer's reliable resolution.Solution: 1. Characterize Fabrication Limits: Perform test prints to determine the minimum viable strut diameter for your specific AM machine and material [19].2. Adjust Generation Parameters: In your design software, increase the minimum strut diameter based on empirical data.Cause 2: Incorrect Print Orientation. Struts are oriented at an unsustainable overhang angle [18].Solution: 1. Reorient the Part: Rotate the lattice structure so that most struts are self-supporting or require minimal supports.2. Use Lattice-Specific Supports: Implement specialized support structures that are easier to remove without damaging delicate features. |

| Warping or Corner Lifting | The edges of the lattice structure, particularly those adjacent to the build plate, curl upward and detach. | Cause 1: High Residual Stresses. Internal stresses from the layer-by-layer fusion process exceed the part's adhesion to the build plate. This is common with materials like ABS and Nylon [21].Solution: 1. Use a Heated Build Chamber: Print in an enclosed environment to control cooling and minimize thermal gradients.2. Apply Adhesives: Use a dedicated adhesive (e.g., glue stick, hairspray) on the build plate to improve adhesion [21].3. Optimize Bed Temperature: Calibrate the build plate temperature for your specific material.Cause 2: Sharp Corners in the Base. The design of the part's base or enclosure has sharp corners that concentrate stress [21].Solution: 1. Design "Lily Pads": Integrate small, sacrificial rounded pads at the base of the lattice to distribute stress and improve adhesion. |

| Support Material Difficult to Remove | Support structures are fused to the lattice, making removal difficult and risking damage to the delicate lattice members. | Cause: Excessive Support Contact. Supports are too dense or have too much surface area contact with the lattice nodes and struts.Solution: 1. Design Self-Supporting Lattices: Configure lattice parameters (like node placement and strut angles) to maximize self-supporting angles (typically > 45 degrees) [18].2. Adjust Support Settings: In your slicing software, increase the support Z-distance (gap to the part) and use a less dense support pattern (e.g., lines or zig-zag instead of grid). |

| Infill Showing on Exterior | The internal lattice or infill structure is visible on the top or side surfaces of a solid enclosure, creating an uneven surface finish. | Cause 1: Insufficient Shell Thickness. The number of perimeter walls or solid top/bottom layers is too low to fully encapsulate the internal lattice [21].Solution: 1. Increase Surface Layers: In your slicer, increase the number of "top solid layers" and "bottom solid layers" to create a thicker skin over the lattice core.Cause 2: Excessive Infill Overlap. The lattice or infill is extending too far into the perimeter walls.Solution: 1. Reduce Infill Overlap: Slightly decrease the "infill overlap" percentage in your slicer settings. |

Experimental Protocols for Lattice Characterization

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in DfAM and lattice optimization research.

Protocol: Topology Optimization of Lightweight Lattices

Aim: To minimize the relative density of a periodic lattice material under simultaneous stiffness and stability constraints [20].

Workflow:

Topology Optimization Workflow

Methodology:

- Input Definition: Select the constituent material properties, design cell dimensions, applied strain fields (e.g., axial, shear), and optimization parameters (e.g., penalty factors, move limits) [20].

- Domain Discretization: Model the design domain using a ground structure, which is a highly interconnected network of potential struts (e.g., an 11x11 node grid with 320 frame elements of tubular cross-section) [20].

- Finite Element Modeling: Use Timoshenko beam elements to accurately capture shear deformations in the lattice members, which are non-negligible for thicker struts [20].

- Optimization Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function: Minimize the weighted relative density of the lattice.

- Constraints: Enforce stiffness (effective elastic moduli) and stability (buckling strain) targets. A stability constraint pushes the instability triggering strain beyond a predefined threshold [20].

- Sensitivity Analysis & Iteration: Derive analytical sensitivities for the objective and constraints. Use a gradient-based optimization algorithm to iteratively update the design variables (strut cross-sections) until convergence is achieved [20].

Protocol: Mechanical Testing and Validation of Printed Lattices

Aim: To experimentally validate the mechanical performance (stiffness, strength, and stability) of an additively manufactured lattice structure and compare it to computational models.

Workflow:

Lattice Validation Workflow

Methodology:

- Specimen Fabrication: Print lattice specimens according to the optimized design, adhering to DfAM guidelines for orientation and support to minimize defects [19].

- Dimensional Assessment: Use microscopy (e.g., SEM) or 3D scanning to measure the as-printed dimensions, including strut diameters and any deviations from the intended design. This is critical for correlating with model predictions [19] [22].

- Computational Model Update: Update the finite element (FE) model with the measured geometry to create a more accurate prediction, accounting for manufacturing imperfections [19].

- Mechanical Testing: Perform quasi-static uniaxial compression tests on the printed lattice specimens using a universal testing machine.

- Data Analysis: From the stress-strain curve, extract key performance metrics:

- Effective Stiffness: The slope of the initial linear elastic region.

- Peak Strength: The maximum stress before collapse.

- Energy Absorption: The area under the curve up to a specific strain.

- Buckling Strain: The strain at which a sudden load drop or visible deformation occurs, indicating instability [20].

- Model Validation: Compare the experimental results with the predictions from the original and updated FE models. The discrepancy informs the reliability of the computational design process and guides future design iterations [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and software solutions used in advanced DfAM research for lattice structures.

| Item Name | Function / Rationale | Application in Lattice Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Based Superalloys | High-performance metals offering excellent strength and crack resistance at elevated temperatures. AM processes like binder-jetting can create hollow/lattice architectures with reduced residual stress compared to casting [19] [23]. | Lightweight aerospace components and high-temperature heat exchangers [19]. |

| Biocompatible Polymers (PEEK, PLA, TPU) | A range of polymers suitable for medical applications. PEEK offers high strength and biocompatibility, while TPU provides elasticity. AM enables personalization of lattice geometries [19] [23]. | 3D printed tissue scaffolds and patient-specific medical implants that promote bone ingrowth [19] [18]. |

| Advanced Design Software (e.g., nTop) | Engineering software based on implicit modeling, which is not limited by traditional CAD bottlenecks. It allows for the creation and manipulation of highly complex lattice structures and automated workflow generation [18]. | Generating and optimizing stochastic or field-driven lattice designs, and automating the customization of lattice parameters for mass personalization [18]. |

| Ground Structure Modeling | A computational method for discrete topology optimization that begins with a highly interconnected network of nodes and struts. The optimization algorithm then finds the optimal material distribution within this network [20]. | The foundational starting point for topology optimization algorithms to generate novel, high-performance lattice unit cells under stiffness and stability constraints [20]. |

| Timoshenko Beam Elements | A type of finite element used in structural analysis that accounts for shear deformation, which is significant for shorter and thicker beams. This provides greater accuracy than Euler-Bernoulli beam elements [20]. | Used in the FE analysis step of lattice optimization to more accurately predict the mechanical response (stiffness and buckling) of lattice struts [20]. |

Microstructure Analysis and Homogenization Techniques for Material Properties

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Computational Homogenization Issues

Problem: Inaccurate homogenized properties in periodic microstructures

- Symptoms: Non-representative effective material properties, unrealistic stress concentrations at boundaries, failure to converge to expected isotropic behavior.

- Causes: Incorrect application of periodic boundary conditions, using Representative Volume Element (RVE) for a periodic microstructure, or an RVE that is too small to be statistically representative [24].

- Solutions:

- For periodic microstructures, use a Repeating Unit Cell (RUC) and apply periodic boundary conditions [24]. The Cell Periodicity feature in some software can automate this setup [24].

- For non-periodic, statistically homogeneous microstructures, use an RVE with homogeneous displacement or traction boundary conditions [24].

- Ensure the RVE size is sufficient. Accuracy for periodic materials using an RVE depends on the subvolume size [24].

Problem: Failure in numerical homogenization of composites

- Symptoms: Large dispersion in computed effective properties, poor convergence, inability to replicate analytical model results.

- Causes: Inadequate mesh resolution, improper choice of homogenization method for the composite type [24] [25].

- Solutions:

- Perform a mesh sensitivity study to ensure results are mesh-independent.

- Validate your numerical method against established analytical models (e.g., Voigt-Reuss, Halpin-Tsai) for your composite type [24] [25]. For unidirectional fiber composites, the Halpin-Tsai-Nielsen model often shows good agreement with numerical results for small to medium fiber volume fractions [24].

- For composites with continuous orthotropic fibers in an isotropic matrix, start with the Voigt-Reuss model as a benchmark [24].

Common Experimental Microstructure Analysis Issues

Problem: Surface scratches persist after final polishing

- Symptoms: Visible scratches under the microscope that can be mistaken for microstructural features like cracks [26] [27].

- Causes: Skipping grit sizes during grinding, using contaminated or worn polishing cloths, or inadequate cleaning between steps [26].

- Solutions:

- Follow a strict sequential grinding and polishing regimen without skipping grit sizes (e.g., 120 → 240 → 320 → 400 → 600 grit) [26] [27].

- Clean the sample ultrasonically or rinse thoroughly between each step to prevent abrasive carry-over [26].

- Replace polishing cloths and suspensions regularly. Inspect the sample under a microscope after each step to ensure all scratches from the previous step are removed [26].

Problem: Edge rounding or relief

- Symptoms: Rounded edges or elevated phases on the sample, leading to misinterpretation of structural relationships [26].

- Causes: Excessive pressure during polishing, using soft cloths too early, or poor mounting technique that fails to support edges [26].

- Solutions:

- Apply light-to-moderate force, especially during final polishing [26].

- Use harder woven cloths for initial polishing stages and reserve soft nap cloths only for the final step [26] [27].

- Use a mounting medium with low shrinkage and excellent adhesion, such as slow-curing epoxy, to provide firm edge retention [26].

Problem: Smearing of soft phases

- Symptoms: Obscured microstructural features and inaccurate phase boundaries in materials like cast iron (graphite) or brass (lead) [26].

- Causes: Polishing with excessively high pressure or speed, which plastically deforms and smears soft phases over harder ones [26].

- Solutions:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an RVE and an RUC? A1: An RVE (Representative Volume Element) is a subvolume of a material that is statistically representative of the whole heterogeneous microstructure, which may or may not be periodic. It is a "top-down" approach where homogeneous displacement or traction boundary conditions are applied. An RUC (Repeating Unit Cell) describes a material that is truly periodic at the micro-scale. It is a "bottom-up" approach that requires periodic boundary conditions to determine effective properties [24].

Q2: When should I use analytical versus numerical homogenization methods? A2: Analytical methods (or "rule of mixtures"), such as Voigt, Reuss, or Halpin-Tsai, are best for quick estimates, initial design phases, or for validating numerical models. They are particularly suitable for composites with simple, well-defined microstructures (e.g., unidirectional fibers) [24]. Numerical methods, like finite element homogenization, are necessary for complex microstructures, analyzing the local stress and strain fields, and when high accuracy is required for composites with arbitrary phase geometry and distribution [24] [28].

Q3: My homogenized elastic properties are not converging. What should I check? A3:

- Boundary Conditions: Verify you are applying the correct boundary conditions (periodic for RUC, homogeneous for RVE) [24].

- RVE/RUC Size: Ensure your volume element is large enough to be representative. Conduct a convergence study by increasing the size of the RVE and monitoring the change in effective properties [24].

- Load Cases: For linear elasticity, all six components of the homogenized elasticity tensor must be determined by solving six separate load cases, each prescribing a unit macroscopic strain [24].

Q4: What is the recommended workflow to achieve a deformation-free mirror finish for EBSD? A4: A robust metallographic polishing workflow consists of three key stages [27]:

- Planar Grinding: Use sequential SiC abrasive papers (e.g., 120, 240, 320, 400, 600, 800 grit) with moderate pressure and water lubrication to establish a flat, scratch-free surface.

- Intermediate Polishing: Use diamond suspensions (e.g., 9μm, 6μm, 3μm) on hard or medium-hard cloths to remove grinding scratches while maintaining flatness.

- Final Polishing: Use a soft nap cloth with a chemico-mechanical suspension like colloidal silica (0.05-0.04μm) for 2-5 minutes with low pressure to remove fine scratches and produce a deformation-free, mirror-like surface ideal for EBSD [27].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Homogenized Elastic Properties of a Unidirectional Fiber Composite

The table below compares the effective Young's moduli and shear moduli obtained from various analytical models and numerical homogenization for a unidirectional fiber composite, as a function of fiber volume fraction [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical and Numerical Homogenization Methods

| Material Property | Fiber Volume Fraction | Voigt-Reuss Model | Halpin-Tsai Model | Halpin-Tsai-Nielsen Model | Numerical Homogenization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Young's Modulus (E₁) | 60% | ~105 GPa | ~108 GPa | ~107 GPa | ~107 GPa |

| Transverse Young's Modulus (E₂) | 60% | ~12 GPa | ~9.5 GPa | ~8.5 GPa | ~8.2 GPa |

| In-Plane Shear Modulus (G₁₂) | 40% | ~5.1 GPa | ~4.9 GPa | ~4.8 GPa | ~4.8 GPa |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Numerical Homogenization of Elastic Properties

This protocol outlines the process for computing the homogenized elasticity tensor using finite element analysis and periodic boundary conditions [24].

- Geometry Definition: Create a 3D model of your RVE or RUC, ensuring it accurately represents the composite's microstructure (e.g., fiber placement, particle distribution).

- Material Assignment: Assign linear elastic properties to each constituent phase (e.g., fiber and matrix).

- Apply Periodic Boundary Conditions: Use a dedicated "Cell Periodicity" or similar feature to enforce periodic constraints on opposite faces of the RUC. This involves defining source and destination boundary pairs.

- Apply Six Unit Strain Load Cases: Solve six separate static analyses. In each case, prescribe a unit value for one macroscopic strain component (εₓₓ, εᵧᵧ, ε𝔃𝔃, γₓᵧ, γₓ𝔃, γᵧ𝔃) while setting the others to zero.

- Compute Volume-Averaged Stresses: For each load case, compute the volume-average of the stress field over the RUC/RVE.

- Construct the Homogenized Elasticity Tensor: The components of the homogenized elasticity tensor, C, are determined by the relationship between the applied unit strains and the resulting volume-averaged stresses. Each column in C is populated by the stress responses from a corresponding unit strain load case.

Metallographic Polishing Parameters for a Mirror Finish

The following table provides detailed parameters for a standard three-step polishing procedure to achieve a mirror finish on a metallic sample [27].

Table 2: Metallographic Polishing Parameters for Mirror Finish

| Stage | Abrasive / Suspension | Cloth Type | Time (Minutes) | Speed (RPM) | Force (N) | Lubricant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Polish 1 | 9μm Diamond | Hard (e.g., Nylon) | 5 - 7 | 150 | 25 | As per suspension |

| Intermediate Polish 2 | 6μm Diamond | Hard (e.g., Nylon) | 4 - 6 | 150 | 20 | As per suspension |

| Intermediate Polish 3 | 3μm Diamond | Medium-Hard (e.g., Silk) | 3 - 5 | 150 | 15 | As per suspension |

| Final Polish | 0.05μm Colloidal Silica | Soft Nap (e.g., Wool) | 2 - 5 | 120 - 150 | 10 - 15 | Increased lubricant flow |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Homogenization in Material Analysis

Metallographic Sample Prep Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Microstructure Analysis and Homogenization

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Colloidal Silica Suspension | A chemico-mechanical polishing suspension used in the final polishing step to produce a deformation-free, mirror-like surface ideal for high-magnification analysis and EBSD [27]. |

| Diamond Suspensions (9μm, 6μm, 3μm) | Standard abrasive suspensions used for intermediate polishing steps to efficiently remove scratches from grinding and prepare the surface for final polishing [27]. |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Abrasive Papers | Used for the initial planar grinding stages to rapidly remove material, flatten the specimen surface, and introduce a uniform, progressively finer scratch pattern [27]. |

| Vero White Plus Photosensitive Resin | A 3D printing material used to create simulated "hard rock" or rigid phases in composite material models for experimental mechanical testing, offering high consistency and repeatability [25]. |

| Representative Volume Element (RVE) | A digital or physical subvolume of a material that is statistically representative of the whole microstructure, used for computational or analytical homogenization [24]. |

This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers working on the optimization of lattice parameters in periodic systems. The content is framed within a broader thesis on computational and experimental strategies for designing advanced materials, with a specific focus on the distinctions and synergies between microscale and macroscale modeling approaches. The following sections address common challenges through FAQs and detailed experimental protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between microscale and macroscale models in the context of lattice optimization?

Microscale and macroscale models represent two ends of the computational modeling spectrum for understanding periodic structures [29].

- Macroscale Models treat a structure as a continuous material with effective, homogenized properties. They use categories and flows between them to determine dynamics, often described by ordinary, partial, or integro-differential equations [29]. In lattice optimization, a macroscale approach might treat an entire lattice block as a solid material with a specific, averaged stiffness or density [30] [31].

- Microscale Models simulate fine-scale details, such as individual struts, plates, or pores within a lattice's unit cell. They can capture interactions between these discrete elements, which determines the overall structural dynamics [29]. These are often discrete-event, individual-based, or agent-based models.

2. My simulation results do not match my experimental data for a 3D-printed lattice structure. What could be wrong?

This common issue often arises from a disconnect between the model's assumptions and physical reality. Key areas to investigate include:

- Scale Separation Assumption: Homogenization theories used in multi-scale modeling assume a clear separation between the micro and macro scales [30] [31]. If the size of your unit cell is too large relative to the overall structure, this assumption is violated, and predictions will be inaccurate. Ensure your representative volume element (RVE) is significantly smaller than the macro-structure.

- Model Fidelity vs. Manufacturing Defects: Your simulation might assume perfect geometry, but additive manufacturing can introduce imperfections such as variations in strut thickness, surface roughness, or partially fused material [32]. Consider incorporating statistical data on manufacturing tolerances into your microscale model or using CT scans of the printed structure for simulation.

- Material Property Definition: The base material properties used in your simulation (e.g., for the polymer or metal powder) might not accurately reflect the properties of the material after it has been processed by your specific 3D printer [32]. Validate the simulated base material properties against simple tensile tests of printed samples.

3. The computational cost of my multiscale topology optimization is prohibitively high. How can I reduce it?

Prohibitive computational cost is a major challenge in concurrent multiscale optimization [31]. The following strategies can help manage this:

- Database-Assisted Strategy: A highly effective method is to pre-compute a database (or "catalog") of micro-architectured materials with a wide range of homogenized properties in an offline step [31]. During the macroscale optimization (online step), the algorithm simply selects the best-performing material from this pre-computed database, reducing the problem to a single-scale optimization and drastically cutting computation time.

- Surrogate Models: Replace the computationally expensive finite element analysis (FEA) with a machine learning-based surrogate model. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) or other regression model can be trained to predict mechanical performance (e.g., Young's modulus) directly from geometric parameters, which is orders of magnitude faster than simulation [32] [33].

- Active Learning: When using surrogate models, employ active learning methods like Bayesian Optimization to intelligently and iteratively select the most informative design points to simulate, rather than relying on a brute-force grid search. This can reduce the number of required simulations by over 80% [33].

4. How do I choose an objective function for optimizing an energy-absorbing lattice structure?

For energy absorption, the goal is often to maximize specific energy absorption (SEA) while controlling the Peak Crushing Force (PCF). A common formulation is to use a multi-objective optimization framework [32].

You can define the objective as a weighted sum:

Objective = Maximize(SEA) + Minimize(PCF)

Alternatively, you can treat it as a constrainted problem:

Maximize(SEA) subject to PCF < [maximum allowable force]

The specific energy absorption (SEA) is calculated as the total energy absorbed divided by the mass of the structure. The energy absorbed is the area under the force-displacement curve from a compression test [32].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Concurrent Two-Scale Topology Optimization for 3D Structures

This protocol outlines a database-assisted strategy for designing stiff, lightweight structures incorporating porous micro-architectured materials [31].

1. Objective: To minimize the compliance (maximize stiffness) and weight of a macroscopic structure by concurrently optimizing its topology and the topology of its constituent micro-architectured material.

2. Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the core two-stage, database-assisted workflow for efficient multiscale optimization.

3. Materials and Computational Tools:

- Software: Finite Element Analysis (FEA) software (e.g., Abaqus, COMSOL); Topology Optimization code (e.g., with level-set or SIMP methods).

- Hardware: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster for offline database generation.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Offline Step: Building the Microstructure Database

- Define the Design Domain: Select a base unit cell (e.g., a cubic volume) that will be tessellated to form the micro-architecture.

- Formulate the Micro-Optimization Problem: Set the objective to find the material distribution within the unit cell that minimizes its homogenized compliance for a given volume fraction. The design variable is the density of each finite element in the unit cell mesh.

- Homogenization: For a given micro-topology, use asymptotic homogenization theory to compute its effective elastic properties (the homogenized elasticity tensor) [30] [31]. This involves solving a set of linear elastic problems on the unit cell with periodic boundary conditions.

- Solve and Store: Run the topology optimization for a wide range of target volume fractions (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.9). For each optimized microstructure, store its homogenized elasticity tensor and its volume fraction in a database.

- Online Step: Macroscale Optimization

- Define the Macro-Problem: Set up the design domain, boundary conditions, and loads for the macroscopic object (e.g., a bridge or bone implant).

- Finite Element Analysis: Perform FEA on the macro-structure. At each integration point, the material properties are not fixed but are drawn from the database.

- Material Selection: For each element in the macro-structure, select the material from the pre-computed database that gives the best performance (e.g., lowest compliance for a given weight).

- Topology Update: Update the macroscale topology using a level-set method guided by shape derivatives. This changes the material distribution at the macro-scale.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 2-4 until the design converges and no significant improvement is made.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Accelerated Design of Lattice Structures

This protocol uses surrogate modeling and active learning to rapidly navigate the design space of triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) lattices [33].

1. Objective: To efficiently find the geometric parameters of a lattice unit cell that yield a target Young's Modulus.

2. Workflow Overview: The workflow combines dataset creation, surrogate model training, and iterative optimization to efficiently explore the design space.

3. Materials and Computational Tools:

- Software: FEA software (e.g., nTopology, Abaqus); Python with scikit-learn or TensorFlow for ML; Bayesian Optimization libraries (e.g., scikit-optimize).

- Hardware: Standard workstation.

4. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Parametrize the Lattice: Select a lattice family (e.g., Gyroid, Schwarz, Diamond) and define the geometric parameters. These typically include:

t: Strut/plate thickness.UC_x,UC_y,UC_z: Unit cell size in each spatial direction.

- Generate Initial Dataset: Perform an initial grid-based search of the parameter space. For each unique combination of parameters, use an automated FEA pipeline to simulate a uniaxial compression test and calculate the effective Young's Modulus,

E[33]. This creates the initial data for training. - Train Surrogate Model: Train a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) regression model. The input features are the geometric parameters, and the target value is the Young's Modulus from FEA. Aim for a high coefficient of determination (R² > 0.95) [33].

- Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- The trained surrogate model is used by a Bayesian Optimizer, which proposes new, promising design parameters expected to improve the objective (e.g., higher Young's Modulus).

- Run FEA on these proposed designs to get the true mechanical performance.

- Add this new data point (parameters and result) to the training dataset.

- Re-train or update the surrogate model with the augmented dataset.

- Convergence: Repeat step 4 until the performance improvement between iterations falls below a predefined threshold, indicating that an optimal design has been found.

Data Presentation

| Feature | Microscale Models | Macroscale Models |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Simulates fine-scale details and discrete interactions | Uses homogenized properties and continuous equations |

| Typical Time Scale | Nanoseconds to Microseconds | Seconds and beyond |

| Typical Length Scale | Nanometers to hundreds of Nanometers | Meters |

| Representative Applications | Molecular diffusion in hydrogel meshes; individual strut stress analysis [34] | Overall stiffness of a bone implant; crashworthiness of a lattice-filled panel [32] |

| Computational Cost | High to very high | Low to moderate |

| Key Advantage | High detail and accuracy for local phenomena | Computational efficiency for large-scale systems |

| Method | Key Principle | Best Suited For | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concurrent Multiscale Topology Optimization [31] | Simultaneously optimizes material micro-structure and structural macro-scale. | Designing novel, high-performance micro-architectures for specific macro-scale applications. | Potentially superior performance by fully exploiting the design freedom at both scales. |

| Database-Assisted Strategy [31] | Uses a pre-computed catalog of optimized microstructures during macro-scale optimization. | Problems where computational cost of full concurrent optimization is prohibitive. | Drastically reduced online computation time; the database is reusable. |

| Surrogate Model-Based Optimization [32] [33] | Replaces expensive FEA with a fast ML model to predict performance from parameters. | Rapid exploration and optimization within a pre-defined lattice family and parameter space. | Speed; can reduce required FEA simulations by over 80% using active learning [33]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II) [32] | A population-based search algorithm inspired by natural selection. | Multi-objective problems (e.g., maximizing SEA while minimizing PCF). | Effectively searches complex parameter spaces and finds a Pareto front of optimal solutions. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental "Reagents" for Lattice Structure Research

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software | A computational tool used to simulate physical phenomena (e.g., stress, heat transfer) to predict the performance of a digital model. |

| Homogenization Theory | A mathematical framework used to compute the effective properties of a periodic composite material (like a lattice) by analyzing its representative unit cell [30] [31]. |

| Triply Periodic Minimal Surfaces (TPMS) | A class of lattice structures (e.g., Gyroid, Schwarz, Diamond) known for their superior mechanical properties and smooth, self-supporting surfaces [33]. |

| Level-Set Method | A numerical technique used in topology optimization to implicitly represent and evolve structural boundaries, enabling topological changes like hole creation [31]. |

| Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) | An additive manufacturing technology that uses a laser to fuse fine metal or polymer powder particles, enabling the precise fabrication of complex lattice structures [32]. |

| Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) | A type of artificial neural network used as a surrogate model to learn the mapping between a lattice's geometric parameters and its mechanical performance [32] [33]. |

Computational Methods and Practical Implementation Frameworks

Quantum Annealing-Assisted Lattice Optimization (QALO) for High-Entropy Alloys

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concept and Workflow

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind using Quantum Annealing for HEA lattice optimization?

A1: The QALO algorithm leverages quantum annealing (QA) to find the ground-state energy configuration of a High-Entropy Alloy lattice by treating it as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) problem. QA is a quantum analogue of classical simulated annealing that exploits quantum tunneling effects to explore low-energy solutions and escape local minima, ultimately finding the global minimum energy state of the corresponding quantum system. This is particularly advantageous for navigating the extremely large search space of possible atomic configurations in HEAs [35].

Q2: How does the QALO algorithm integrate machine learning with quantum computing?

A2: QALO operates on an active learning framework that integrates three key components:

- Field-aware Factorization Machine (FFM) acts as a surrogate model for predicting lattice energy without expensive DFT calculations at every step.

- Quantum Annealer serves as the optimizer that solves the QUBO-formulated configuration problem.

- Machine Learning Potential (MLP) provides the ground truth energy calculation for validation and iterative improvement [35] [36].

This hybrid approach combines the computational efficiency of machine learning with the global optimization capability of quantum annealing.

Implementation and Formulation

Q3: How is the HEA lattice optimization problem mapped to a QUBO formulation?

A3: The mapping involves two critical steps:

- Binary Representation: For an M-element, N-site HEA system, a binary variable x with M × N dimensions represents occupation status, where xij = 1 indicates an atom of type i occupies site j [35].

- Energy Model: The total lattice energy is expressed as E = ∑{i,j,k,l} U{ijkl} x{ij} x{kl}, where the quadratic term U{ijkl} x{ij} x_{kl} represents energy contribution when atom type i and k occupy sites j and l, respectively [35].

This formulation naturally fits the QUBO structure required for quantum annealing.

Q4: How does configurational entropy factor into the optimization process?

A4: Configurational entropy is incorporated as a constraint to ensure the optimized structure remains in the high-entropy region of the phase diagram. Using Boltzmann's entropy formula, ΔSconf = -R ∑{i=1}^M (1/N ∑{j=1}^N xij) ln(1/N ∑{j=1}^N xij), this constraint controls the composition to favor equiatomic or near-equiatomic distributions that maximize entropy while minimizing energy [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

QUBO Formulation Issues

Problem: Inaccurate energy mapping between physical system and QUBO representation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized configurations have higher energy than expected | Incomplete cluster expansion in energy model | Expand the pair interaction model to include higher-order terms (triplets, quadruplets) |

| Quantum annealer returns infeasible solutions | Weak constraint weighting in QUBO formulation | Increase penalty terms for constraint violations and validate constraint satisfaction |

| Solutions violate composition constraints | Improper implementation of configurational entropy | Adjust Lagrange multipliers for entropy constraints and verify boundary conditions |

Implementation Note: When establishing the QUBO mapping, ensure the effective pair interaction (EPI) model properly captures the dominant interactions in your specific HEA system. The energy should be expressible as E(σ) = NJ₀ + N∑_{X,Y} J^{XY}σ^{XY}, where J^{XY} is the pair-wise interatomic potential and σ^{XY} is the percentage of XY pairs [35].

Surrogate Model Performance

Problem: Field-aware Factorization Machine (FFM) provides inaccurate energy predictions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large discrepancy between FFM predictions and MLP/DFT validation | Insufficient training data or poor feature representation | Increase diversity of training configurations; incorporate domain knowledge in feature engineering |

| Model fails to generalize to new configuration spaces | Overfitting to limited configuration types | Implement cross-validation; apply regularization techniques; expand training set diversity |

| Prediction accuracy degrades for non-equiatomic compositions | Training data bias toward specific compositions | Ensure training data covers target composition space uniformly |

Protocol for Surrogate Model Training:

- Generate initial training data using DFT calculations on diverse HEA configurations

- Train FFM model using cross-validation to prevent overfitting

- Validate predictions against MLP calculations for select configurations

- Iteratively improve model by incorporating new data from quantum annealing results [35]

Quantum Hardware Limitations

Problem: Constraints in current quantum annealing technology

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Limited lattice size that can be optimized | QUBO problem size exceeds qubit count | Implement lattice segmentation; use hybrid quantum-classical approaches |

| Suboptimal solutions despite sufficient run time | Analog control errors or noise | Employ multiple anneals; use error mitigation techniques; verify with classical solvers |

| Inability to embed full problem graph on quantum processor | Limited qubit connectivity | Reformulate QUBO to match hardware graph; use minor embedding techniques |

Experimental Consideration: When applying QALO to the NbMoTaW alloy system, researchers successfully reproduced Nb depletion and W enrichment phenomena observed in bulk HEA, demonstrating the method's practical effectiveness despite current hardware limitations [35].

Validation and Result Interpretation

Problem: Discrepancy between predicted and experimentally observed properties

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized structures show different properties than predicted | Neglect of lattice distortion effects | Perform additional lattice relaxation after quantum annealing optimization |

| Mechanical properties don't match predictions | Insufficient accuracy in energy model | Incorporate lattice distortion parameters into the QUBO formulation |

| Phase stability issues in experimental validation | Overlooking kinetic factors in synthesis | Complement with thermodynamic parameters (Ω, Λ) for phase stability assessment [37] |

Validation Protocol:

- Compare QALO-optimized structures with known experimental results (e.g., Nb depletion/W enrichment in NbMoTaW)

- Calculate mechanical properties (yield strength, plasticity) and compare with randomly generated configurations

- Validate thermodynamic stability using additional indicators (ΔHmix, ΔSmix, δ, VEC) [37] [38]

- Perform experimental verification where possible

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for QALO Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solution | Function in QALO Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software | D-Wave Ocean SDK | Provides tools for QUBO formulation and quantum annealing execution | Use for minor embedding and quantum-classical hybrid algorithms |

| Surrogate Models | Field-aware Factorization Machine (FFM) | Predicts lattice energy for configuration evaluation | Train on DFT data; implement active learning for continuous improvement |

| Validation Potentials | Machine Learning Potentials (MLP) | Provides ground truth energy calculation | Use for validating quantum annealing results without full DFT cost |

| DFT Codes | VASP | Generates training data and validates critical configurations | Set with 500 eV kinetic energy cutoff; use PBE-GGA for exchange-correlation [38] |

| Classical Force Fields | Spectral Neighbor Analysis Potential (SNAP) | Provides efficient energy calculations for larger systems | Useful for pre-screening configurations before quantum annealing |

Workflow Visualization

QALO Active Learning Workflow

QUBO Problem Mapping Process

Key Parameter Reference Tables

Table: Thermodynamic Parameters for HEA Optimization [35] [37] [38]

| Parameter | Mathematical Form | Optimization Target | Role in QALO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing Enthalpy (ΔH_mix) | ΔHmix = ∑{i |

Minimization | Primary optimization target in energy function | ||

| Configurational Entropy (ΔS_conf) | ΔSconf = -R ∑{i=1}^M Xi ln Xi | Maximization/Constraint | Ensures high-entropy character is maintained | ||

| Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG_mix) | ΔGmix = ΔHmix - T·ΔS_conf | Minimization | Overall thermodynamic stability target | ||

| Atomic Size Difference (δ) | δ = √[∑xi(1 - ri/ṛ)²] | δ ≤ 6.6% | Constraint for solid-solution formation | ||

| Ω Parameter | Ω = (Tm ΔSmix)/ | ΔH_mix | Ω ≥ 1.1 | Phase stability indicator |

Table: Mechanical Property Enhancement in Optimized HEAs [35] [39]

| Property | Conventional Alloys | QALO-Optimized HEAs | Improvement Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield Strength | Moderate (varies by alloy) | Superior to random configurations | Optimal atomic configuration reducing energy |

| Plasticity | Limited in intermetallics | Enhanced in B2 HEIAs | Severe lattice distortion enabling multiple slip systems |

| High-Temperature Strength | Rapid softening above 0.5T_m | Maintained strength up to 0.7T_m | Dynamic hardening mechanism from dislocation gliding |

| Lattice Distortion | Minimal | Severe, heterogeneous | Atomic size mismatch and electronic property variations |

Conformal Optimization Frameworks for Functionally Graded Stochastic Lattices

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of using Stochastic Lattice Structures (SLS) over Periodic Lattice Structures (PLS) in conformal design?

Stochastic Lattice Structures (SLS) offer two significant advantages for conformal design of complex components. First, their random strut arrangement provides closer conformation to original model surfaces, enabling more accurate replication of complex geometries, including intricate or irregular boundaries [40]. Second, SLS exhibit lower sensitivity to defects due to their near isotropy, making them more reliable in applications where defect tolerance is critical [40] [41]. This contrasts with Periodic Lattice Structures (PLS) which have regular, repeating patterns that may not conform as effectively to complex surfaces [40].

FAQ 2: What are the main computational challenges in implementing 3D-Functionally Graded Stochastic Lattice Structure (3D-FGSLS) frameworks?

Implementing 3D-FGSLS frameworks presents two significant computational challenges. First, mechanical parameter calculation is difficult because SLS consist of random lattices without clear boundaries, unlike PLS where specific mechanical parameters can be calculated for each regular lattice unit [40]. Second, geometric modeling complexity arises since representing 3D-SLS with variable radii through functional expressions is nearly impossible, unlike PLS which can be modeled based on functional expressions [40]. These challenges necessitate specialized approaches like vertex-based density mapping and node-enhanced geometric kernels [40] [41].

FAQ 3: What density mapping method is recommended for 3D-FGSLS and how does it differ from PLS approaches?

For 3D-FGSLS, the recommended approach is the Vertex-Based Density Mapping (VBDM) method, which transforms the density field into geometric information for each vertex [40] [41]. This differs fundamentally from PLS methods like Size Matching and Scaling (SMS) and the Relative Density Mapping Method (RDM), which are based on modeling periodic lattice structures [40]. The VBDM method is specifically designed to handle the random nature of SLS and enables efficient material utilization while conforming to complex geometries [40].

FAQ 4: What mechanical testing protocols are essential for validating functionally graded lattice structures?

For comprehensive validation, both compression testing and flexural testing should be performed. While lattice structures are typically evaluated under compression, their flexural properties remain largely underexplored yet critical for many applications [42]. Specifically, three-point and four-point bending tests provide valuable data on flexural rigidity, which is particularly important for biomedical applications like bone scaffolds [42]. Non-linear finite element (FE) models can simulate these bending tests to compare results with bone surrogates or other reference standards [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Conformal Structures at Complex Boundaries

Problem: Generated lattice structures do not properly conform to intricate or irregular component boundaries.

Solution:

- Implement convex hull-based geometric algorithms: Specifically designed for node-enhanced lattice structures to ensure proper boundary conformation [40].

- Apply boolean operation-based methods: Alternative approach for generating final 3D-FGSLS suitable for printing complex domains [41].

- Verify vertex distribution: Ensure proper vertex density at complex boundaries using the vertex-based data structure (W = 〈V,E〉) where V represents vertices and E represents edges [40].

Prevention:

- Utilize the complete 3D-FGSLS framework spanning from optimization to geometric modeling specifically designed for additive manufacturing [40].

- Conduct preliminary analysis of stochastic microstructures to establish proper conformation parameters before full implementation [40].