Balancing Computational Cost and Accuracy in DFT Methods: AI-Driven Strategies for Drug Discovery

This article explores the critical challenge of balancing computational expense with predictive accuracy in Density Functional Theory (DFT), a cornerstone of computational chemistry.

Balancing Computational Cost and Accuracy in DFT Methods: AI-Driven Strategies for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical challenge of balancing computational expense with predictive accuracy in Density Functional Theory (DFT), a cornerstone of computational chemistry. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational principles to the latest breakthroughs. We delve into how machine learning is revolutionizing the development of more universal exchange-correlation functionals, offer practical strategies for optimizing calculations, and outline robust frameworks for validating results against experimental data. The synthesis of these areas provides a actionable guide for leveraging DFT to accelerate and improve the reliability of in-silico drug and materials design.

The DFT Accuracy-Cost Dilemma: Why This Fundamental Challenge Limits Predictive Chemistry

Foundational Knowledge Base

What is the fundamental principle of Density Functional Theory (DFT)?

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical method used to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems. Its fundamental principle, based on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, is that the ground-state energy of an interacting electron system is uniquely determined by its electron density, ρ(r), rather than the complex many-electron wavefunction. This makes DFT computationally less expensive than wavefunction-based methods. The total energy in the Kohn-Sham DFT framework is expressed as: E[ρ] = Ts[ρ] + Vext[ρ] + J[ρ] + EXC[ρ], where Ts[ρ] is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, Vext[ρ] is the external potential energy, J[ρ] is the classical Coulomb repulsion energy, and EXC[ρ] is the exchange-correlation energy, which encompasses all non-trivial many-body effects [1].

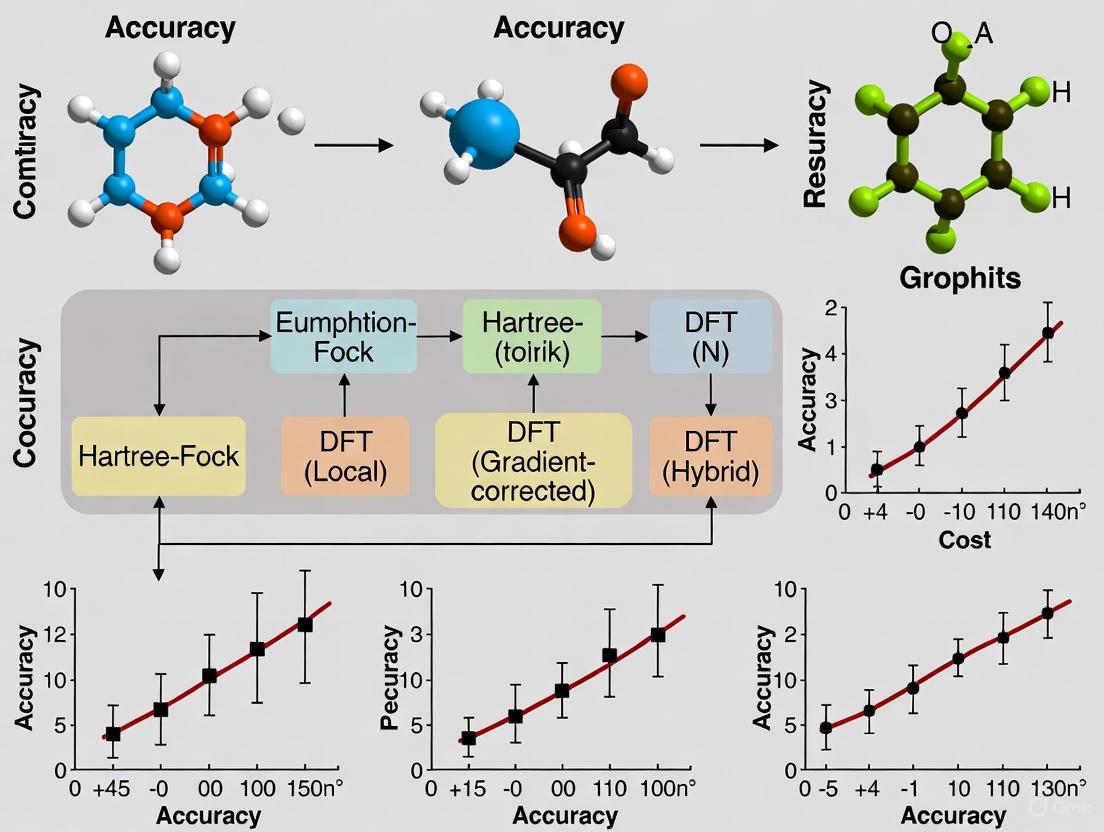

What is the "Jacob's Ladder" of DFT functionals?

"Jacob's Ladder" is a metaphor for the hierarchy of DFT exchange-correlation functionals, which are approximations for the unknown EXC[ρ]. Climbing the ladder involves adding more physical ingredients to the functional, generally improving accuracy but also increasing computational cost [1]. The common rungs are:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Uses only the local electron density, ρ(r). It often overbinds, predicting bond lengths that are too short [1].

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates both the density and its gradient, ∇ρ(r). Examples include BLYP and PBE, which offer better geometries than LDA but can be poor for energetics [1].

- meta-GGA (mGGA): Adds the kinetic energy density, τ(r), or the Laplacian of the density. Examples are TPSS and SCAN, providing more accurate energetics [1].

- Global Hybrid: Mixes a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange with DFT exchange. A famous example is B3LYP, which uses 20% HF exchange [1].

- Range-Separated Hybrid (RSH): Uses DFT exchange for short-range electron interactions and HF exchange for long-range interactions. This is beneficial for properties like charge-transfer excitations. CAM-B3LYP and ωB97X are prominent examples [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and evolution of these functional types, from the simplest to the most complex.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Can you provide a detailed protocol for calculating a vibrationally-resolved UV-Vis spectrum?

Yes, calculating a vibrationally-resolved electronic spectrum using software like Gaussian 16 typically involves a three-step protocol, as demonstrated for an anisole molecule [2].

Objective: Simulate the vibrationally-resolved UV-Vis absorption spectrum of a molecule. Software: Gaussian 16, GaussView, and a visualization/plotting tool (e.g., Origin). Methodology:

- Initial State Optimization & Frequencies: Optimize the geometry of the ground state (S₀) and calculate its vibrational frequencies. The keyword

Freq=SaveNMis used to save the normal mode information to a checkpoint file (anisole_S0.chk).- Input Route:

#p opt Freq=SaveNM B3LYP/6-31G(d) geom=connectivity

- Input Route:

Final State Optimization & Frequencies: Optimize the geometry of the excited state (e.g., the first excited state S₁) and calculate its vibrational frequencies, also saving them with

Freq=SaveNM.- Input Route:

#p TD(nstates=6, root=1) B3LYP/6-31G(d) opt Freq=saveNM geom=connectivity

- Input Route:

Spectra Generation: Use the Franck-Condon method to generate the spectrum by combining the frequency data from both states.

- Input File Content:

Data Processing: The output file (spectra.log) contains the "Final Spectrum" data with energy (cm⁻¹) and molar absorption coefficients. Convert energy to wavelength (nm) using Wavelength (nm) = 10⁷ / Energy (cm⁻¹) and plot the data [2].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram.

What is a standard workflow for ΔSCF calculations of excited-state defects in VASP?

The ΔSCF (delta Self-Consistent Field) method in VASP is used to investigate excited-state properties of defects in solids, such as the silicon vacancy (SiV⁰) in diamond [3].

Objective: Perform a ΔSCF calculation with a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06) to model excited states of a defect. Key INCAR Settings:

ALGO = AllorALGO = Damp(for better electronic convergence).LDIAG = .FALSE.(Critical to prevent orbital reordering and ensure convergence to the correct excited state).ISMEAR = -2(For fixed occupations).FERWEandFERDO(To specify the electron occupancy of the Kohn-Sham orbitals for spin-up and spin-down channels, constraining the system into the desired excited state).

Pitfalls and Version Control: This is a non-trivial calculation with several pitfalls [3]:

- Orbital Reordering: Electron promotion can cause occupied and unoccupied orbitals to change order during the calculation, leading to convergence issues or incorrect states. Using

LDIAG = .FALSE.is essential to mitigate this. - VASP Version: Calculations are most reliable with VASP.5.4.4 (or a specific patched version). Later versions (e.g., 6.2.1, 6.4.2/6.4.3) have known issues with occupation constraints and convergence when

LDIAG = .FALSE.[3]. - Restart Strategy: Starting the calculation "from scratch" can be challenging. A more robust strategy is to restart from a pre-converged wavefunction, such as one from a PBE calculation [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How do I resolve common errors in implicit solvent model calculations in CP2K?

Problem: CPASSERT failed error when using the SCRF (Self-Consistent Reaction Field) implicit solvent model.

Solution: The SCRF method in CP2K is likely unmaintained and may not be fully functional. It is recommended to switch to the more modern SCCS (Surface and Volume Carbon-Surface Continuum Solvent) model instead [4].

Problem: Slow SCF convergence when using the SCCS implicit solvent model.

Solution: The SCCS model introduces an additional self-consistency cycle for the polarization potential, which increases computational cost and can slow convergence. While loosening the EPS_SCCS parameter might help, this can increase noise in atomic forces, making geometry optimizations less stable. There is no perfect solution, and some trade-off between speed and stability must be accepted [5] [4].

FAQ: My hybrid functional calculation runs out of memory. What alternatives do I have?

Problem: Out-of-memory issues in hybrid DFT or TDDFT calculations, especially when using k-point sampling in CP2K for systems with around 200 atoms.

Solution: The RI-HFXk method for k-points is optimized for small unit cells and does not scale well with system size. For large systems, it is recommended to use supercell calculations with gamma-only sampling instead. The standard HFX implementation in CP2K for supercells scales linearly with system size and will use fewer computational resources [6].

FAQ: My ΔSCF calculation converges to the wrong state or fails to converge. What should I check?

This is a common issue in advanced electronic structure calculations. The following table summarizes the key items to check and their functions in resolving the problem.

Table: Troubleshooting ΔSCF Calculations in VASP

| Item to Check | Function & Purpose | Recommended Setting / Solution |

|---|---|---|

LDIAG Tag |

Controls diagonalization and orbital ordering. Must be disabled to maintain desired orbital occupations during electronic minimization. | Set LDIAG = .FALSE. [3] |

| VASP Version | Correct behavior of occupation constraints (ISMEAR = -2) and LDIAG is version-dependent. |

Use VASP.5.4.4 or a specifically patched version [3] |

| Initial Guess | Starting from scratch can lead to incorrect states due to orbital reordering. | Restart from a pre-converged wavefunction (e.g., from a PBE calculation) [3] |

| Orbital Occupations | Manually specifying occupations via FERWE/FERDO is required to define the target excited state. |

Verify occupations are correctly set for the specific defect orbitals involved in the excitation [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Spectroscopy

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for simulating vibrationally-resolved electronic spectra [2].

Table: Essential Components for Vibrationally-Resolved Spectra Calculation

| Item | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Gaussian 16 Software | Primary quantum chemistry software package for performing geometry optimizations, frequency calculations, and spectral simulation. |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d) | A specific hybrid DFT functional and basis set combination providing a balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for organic molecules. |

| Freq=SaveNM Keyword | Saves the normal mode (vibrational) information from a frequency calculation to a checkpoint file for later use in spectrum generation. |

| geom=AllCheck Keyword | Instructs the calculation to read all data (geometry, basis set, normal modes) from the specified checkpoint file(s). |

| Freq=(ReadFC, FC) Keywords | ReadFC reads force constants, and FC invokes the Franck-Condon method for calculating the vibronic structure of electronic transitions. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental challenge with the Exchange-Correlation (XC) functional in Density Functional Theory (DFT)?

The fundamental challenge is that the exact form of the universal XC functional, a crucial term in the DFT formulation, is unknown. While DFT reformulates the exponentially complex many-electron problem into a tractable one with cubic computational cost, this exact reformulation contains the XC functional. For decades, scientists have had to design hundreds of approximations for this functional. The limited accuracy and scope of these existing functionals mean that DFT is often used to interpret experimental results rather than to predict them with high confidence. [7]

FAQ 2: My calculations with the popular B3LYP/6-31G* method give poor results. What are more robust modern alternatives?

The B3LYP/6-31G* combination is known to have severe inherent errors, including missing London dispersion effects and a strong basis set superposition error (BSSE). Today, more accurate, robust, and sometimes computationally cheaper composite methods are recommended. These include: [8]

- B3LYP-3c and r2SCAN-3c: Efficient composite methods that correct for systematic errors.

- B97M-V/def2-SVPD/DFT-C: A modern meta-generalized gradient approximation (meta-GGA) with specific corrections. These alternatives eliminate the systematic errors of B3LYP/6-31G* without significantly increasing computational cost.

FAQ 3: How can I determine if my chemical system is suitable for standard DFT methods?

The key is to determine if your system has a single-reference or multi-reference electronic structure. Standard DFT excels with single-reference systems, which are described by a single-determinant wavefunction. This category includes most diamagnetic closed-shell organic molecules. You should suspect multi-reference character and proceed with caution for systems such as: [8]

- Radicals

- Systems with low band gaps

- Certain transition states For closed-shell molecules, you can check for low-lying triplet states using an unrestricted broken-symmetry DFT calculation.

FAQ 4: What does "chemical accuracy" mean, and why is it important?

"Chemical accuracy" refers to an error margin of about 1 kcal/mol for most chemical processes, such as reaction energies and barrier heights. This is the level of accuracy required to reliably predict experimental outcomes. Currently, the errors of standard DFT approximations are typically 3 to 30 times larger than this threshold, creating a fundamental barrier to predictive simulation. [7]

FAQ 5: How is artificial intelligence (AI) being used to improve DFT?

AI, specifically deep learning, is being used to learn the XC functional directly from vast amounts of highly accurate data. This approach bypasses the traditional "Jacob's ladder" paradigm of hand-designed density descriptors. The process involves: [7]

- Generating Data: Using high-accuracy (but expensive) wavefunction methods to compute reference data for a large and diverse set of small molecules.

- Training Models: Designing deep-learning architectures that learn meaningful representations from electron densities to predict the XC energy accurately. This has led to functionals like Skala, which can reach experimental accuracy for main group molecules while retaining a favorable computational cost.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unrealistically low reaction energies or barrier heights.

- Potential Cause: Missing dispersion interactions. Many older functionals do not account for long-range London dispersion forces.

- Solution: Use a modern functional that includes dispersion corrections, such as those with an empirical -D3 or -D4 correction. When using composite methods like B3LYP-3c, ensure they include an inherent dispersion correction. [8]

Problem: Large errors when comparing computed energies of systems of different sizes.

- Potential Cause: Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE). This error artificially stabilizes fragmented systems because basis functions on one fragment can be used to describe another.

- Solution: Apply an empirical correction for BSSE, such as the counterpoise correction. Alternatively, use composite methods like B3LYP-D3-DCP or B97M-V/def2-SVPD/DFT-C, which are designed to mitigate this error. [8]

Problem: Calculation fails to converge or yields nonsensical results for radicals or metal complexes.

- Potential Cause: Underlying multi-reference character. Standard DFT is a single-reference method and can fail for systems that require multiple determinants for a correct description.

- Solution: First, verify the multi-reference character. If confirmed, consider using multi-reference methods instead of DFT. For experts, a broken-symmetry DFT approach might be applicable, but this requires careful analysis. [8]

Problem: Choosing a functional and basis set for a new project.

- Guidance: Follow a structured decision-making process. The flowchart below outlines a step-by-step protocol for selecting a computational method that balances accuracy, robustness, and efficiency. This includes defining the chemical model, selecting an appropriate functional and basis set, and considering multi-level approaches. [8]

Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Selected Density Functionals and Protocols

This table summarizes the characteristics of several recommended computational approaches.

| Functional / Protocol | Type / Class | Key Features | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G* | Hybrid GGA | Outdated; known for missing dispersion and strong BSSE. | Not recommended; provided as a historical reference. [8] |

| B3LYP-3c | Composite Hybrid GGA | Includes DFT-D3 dispersion and gCP BSSE correction; efficient. | Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations for large systems. [8] |

| r2SCAN-3c | Composite Meta-GGA | Modern, robust meta-GGA base; includes corrections. | General-purpose chemistry; good balance of cost and accuracy. [8] |

| B97M-V | Meta-GGA | High-quality, modern functional with VV10 non-local correlation. | Accurate energies for main-group chemistry. [8] |

| Skala | Machine-Learned | Deep-learning model; trained on big data to reach chemical accuracy. | Predictive calculations for main-group molecules (emerging technology). [7] |

Table 2: Glossary of Key Computational "Reagents"

In computational chemistry, the choice of method is as critical as the choice of physical reagent in an experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Density Functional | The "recipe" that approximates the exchange-correlation energy. It determines the fundamental accuracy of the electron glue calculation. [8] |

| Basis Set | A set of mathematical functions (atomic orbitals) used to construct the molecular orbitals. A larger basis provides more flexibility but increases cost. [8] |

| Dispersion Correction (e.g., D3) | An add-on that empirically accounts for long-range van der Waals (dispersion) interactions, which are missing in many older functionals. [8] |

| Broken-Symmetry DFT | A technique used within unrestricted DFT calculations to probe systems with potential multi-reference character, such as biradicals. [8] |

| High-Accuracy Wavefunction Data | Reference data from expensive, highly accurate methods (e.g., coupled-cluster) used to train and benchmark new DFT functionals. [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Best-Practice Protocol for Routine Single-Reference Systems This protocol is designed for robust and efficient calculations on typical organic molecules. [8]

- Geometry Optimization & Frequencies: Use a composite method like r2SCAN-3c or B3LYP-3c. These methods include necessary corrections and are efficient for optimizing molecular structures and calculating vibrational frequencies to confirm minima or transition states.

- Single-Point Energy Refinement: For higher accuracy in energy-dependent properties (reaction energies, barriers), take the optimized geometry and perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set and a more advanced functional like B97M-V/def2-QZVP. This two-step process balances cost and accuracy.

Protocol 2: Protocol for Assessing Multi-Reference Character Before investing in expensive multi-reference calculations, use this screening protocol. [8]

- Stability Check: Perform a stability analysis of the restricted DFT solution. An unstable solution indicates possible multi-reference character.

- Unbroken vs. Broken-Symmetry: For open-shell systems, compare the energies of the standard unrestricted (unbroken-symmetry) solution and a broken-symmetry solution. A small energy difference suggests significant multi-reference character.

- Inspection of Orbitals: Check for low-lying unoccupied orbitals or small HOMO-LUMO gaps, which can be indicative of multi-reference systems.

Protocol 3: Data Generation for Machine-Learned Functionals This outlines the pipeline used to create high-quality training data for functionals like Skala. [7]

- Diverse Structure Generation: Generate a large and structurally diverse set of small molecular structures (e.g., main-group molecules) using automated, scalable pipelines.

- High-Accuracy Reference Calculation: Use substantial computational resources to calculate the reference energies for these structures with a highly accurate wavefunction method (e.g., CCSD(T)) with a large basis set. This step requires expert knowledge to ensure methodological choices do not compromise accuracy.

- Model Training and Validation: Train the deep-learning model (the functional) on the generated structures and energy labels. Crucially, validate its performance on a separate, diverse benchmark dataset that was not used during training (e.g., W4-17).

Workflow Visualizations

DFT Method Selection Guide

This diagram provides a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate computational method based on the chemical system and task, ensuring a balance between cost and accuracy. [8]

The DFT Accuracy-Cost Landscape

This diagram illustrates the relationship between the computational cost and the typical accuracy of various quantum chemical methods, highlighting the position of DFT. [8]

AI-Enhanced Functional Development

This workflow outlines the process of using deep learning and high-accuracy data to develop next-generation XC functionals, as demonstrated by projects like the Skala functional. [7]

In computational chemistry and drug design, the concept of "chemical accuracy"—defined as an error margin of 1 kilocalorie per mole (kcal/mol)—serves as a critical benchmark for predictive simulations. This threshold is not arbitrary; it represents the energy scale of non-covalent interactions that determine molecular binding, reactivity, and stability. Achieving this level of accuracy is essential for reliably predicting experimental outcomes, as errors exceeding 1 kcal/mol can lead to erroneous conclusions about relative binding affinities and reaction pathways [7] [9].

The pursuit of chemical accuracy now intersects with the rapid development of machine learning (ML) approaches, creating new possibilities for balancing computational cost with precision. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and methodologies for researchers navigating this evolving landscape, with a specific focus on density functional theory (DFT) and machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs).

Understanding the Stakes: FAQs on Chemical Accuracy

Q1: Why is 1 kcal/mol considered the "gold standard" for chemical accuracy?

This energy scale corresponds to the strength of key non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds) that govern molecular recognition and binding. In drug design, an error of 1 kcal/mol in binding affinity prediction can translate to a substantial error in binding constant estimation, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about a compound's efficacy [9]. Furthermore, this precision is necessary to shift the balance of molecule and material design from being driven by laboratory experiments to being driven by computational simulations [7].

Q2: My DFT calculations are computationally expensive. How can I reduce costs without sacrificing accuracy?

Significant reductions in computational cost are possible through strategic trade-offs. Research demonstrates that utilizing reduced-precision DFT training sets can be sufficient when energy and force contributions are appropriately weighted during the training of machine-learned interatomic potentials [10]. Systematic sub-sampling techniques can also identify the most informative configurations, drastically reducing the required training set size. The key is to perform a joint Pareto analysis that balances model complexity, training set precision, and training set size to meet your specific application requirements [10].

Q3: What are the advantages of MLIPs over traditional force fields and ab initio methods?

Machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) aim to offer a "best-of-both-worlds" solution. They promise near-quantum mechanical accuracy while scaling linearly with the number of atoms, unlike ab initio methods which scale cubically with the number of electrons [10]. Compared to traditional force fields, which often treat non-covalent interactions using effective pairwise approximations that can lack transferability, MLIPs can learn complex interactions directly from high-accuracy data, resulting in improved accuracy and robustness [9].

Q4: What is a "universal" atomistic model, and how does it differ from application-specific potentials?

Large Atomistic Models (LAMs), or "universal" models, are foundational machine learning models pre-trained on vast and diverse datasets of atomic structures to approximate a universal potential energy surface [11]. Examples include Meta's Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) [12] and other foundation models. In contrast, application-specific potentials are tailored for a narrower chemical space or specific material system. While universal models offer broad knowledge, they often require fine-tuning for specific applications and can have higher computational costs than simpler, optimized MLIPs [10]. The choice depends on the required trade-off between generality, accuracy, and computational budget.

Troubleshooting Common Computational Workflow Issues

Problem: Inaccurate Energy Predictions in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Symptoms: Unphysical molecular behavior, energy drift, or failure to maintain stable structures during simulations.

Solutions:

- Verify Model Conservativeness: Ensure you are using a conservative-force model, where forces are derived as the gradient of the energy. Non-conservative models that directly predict forces can exhibit high apparent accuracy on static tests but fail to conserve energy in dynamics simulations [11]. For instance, the eSEN architecture offers conservative-force variants specifically for this reason [12].

- Check Training Data Fidelity: Inaccuracies can propagate from the reference data. For robust biomolecular simulations, ensure your model or training data accounts for diverse non-covalent interactions. Benchmarks like the QUID dataset, which provides robust interaction energies for ligand-pocket motifs, can be used for validation [9].

- Validate with Practical Tasks: Use benchmarks that assess practical applicability, such as molecular dynamics stability and property prediction. The LAMBench and MOFSimBench frameworks evaluate these capabilities [11] [13].

Problem: High Computational Cost of Training or Inference

Symptoms: Training MLIPs is prohibitively slow; running simulations with large models takes too long.

Solutions:

- Optimize Model Complexity: For applications demanding speed, consider less complex MLIPs like the linear Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) or qSNAP. These can offer a superior accuracy/cost ratio for specific applications compared to massive foundation models [10].

- Leverage Reduced-Precision Training Data: Explore whether a lower-precision DFT training set (e.g., using a smaller k-point mesh or lower plane-wave cut-off) is sufficient for your accuracy needs, as this can drastically reduce data generation costs [10].

- Utilize Efficient Architectures and Hardware: For inference, model choice greatly impacts speed. Benchmarking shows that models like PFP can be several times faster than similarly accurate but larger models like eSEN-OAM [13]. Also, ensure you are using optimized inference engines and appropriate GPU hardware.

Problem: Poor Transferability to Unseen Chemical Systems

Symptoms: A model performs well on its training data but poorly on new molecules or configurations.

Solutions:

- Expand Training Data Diversity: The model may lack coverage of the chemical space you are applying it to. Use datasets with unprecedented variety, such as the OMol25 dataset, which covers biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes to improve generalizability [12].

- Employ Multi-Task Learning: Architectures like the Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) used in UMA models enable knowledge transfer across datasets computed at different levels of theory, improving performance and transferability [12].

- Perform Rigorous OOD Benchmarking: Evaluate your model on out-of-distribution (OOD) test sets that represent your target applications. Benchmarks like LAMBench are designed specifically to assess this kind of generalizability [11].

Performance Benchmarking and Cost Analysis

Accuracy Benchmarks for MLIPs on MOF Systems

The following table summarizes the performance of various machine learning interatomic potentials on the MOFSimBench benchmark, which evaluates models on key tasks for Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [13].

Table 1: Performance of MLIPs on MOFSimBench Tasks (Based on data from [13])

| Model | Structure Optimization (Success Count/100) | MD Stability (Success Count/100) | Bulk Modulus MAE (GPa) | Heat Capacity MAE (J/mol·K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFP v8.0.0 | 92 | 89 | 1.7 | 5.1 |

| eSEN-OAM | ~84 | 91 | 1.4 | ~7.5 |

| orb-v3-omat+D3 | ~88 | 88 | ~2.3 | 4.6 |

| uma-s-1p1 (odac) | ~87 | Not Tested | ~2.1 | 4.8 |

| MACE-MP-0 | ~70 | 83 | ~4.1 | ~11.5 |

Computational Cost and Error Trade-Off

The trade-off between computational cost and precision is a fundamental consideration. The table below conceptualizes this relationship based on a Pareto analysis, where the optimal surface represents the best possible accuracy for a given computational budget [10].

Table 2: Factors in the Pareto Optimization of MLIPs (Based on [10])

| Factor | Impact on Cost | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Precision Level | Higher precision (finer k-points, larger basis sets) increases data generation cost exponentially. | Reduces inherent error in training labels, but diminishing returns may set in. |

| Training Set Size | Larger sets increase data generation and training time. Can be optimized via active learning. | Improves model robustness and transferability up to a point. |

| MLIP Model Complexity | More complex models (e.g., larger neural networks) increase training and inference cost. | Generally increases accuracy on complex systems, but not always efficiently. |

| Energy vs. Force Weighting | Minimal direct impact on computational cost. | Proper weighting can significantly improve force and energy accuracy, especially with lower-precision data. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Validating MLIP Performance for Biomolecular Interactions

Objective: To assess the accuracy of a machine-learned interatomic potential in predicting interaction energies in ligand-pocket systems, crucial for drug design.

Methodology:

- Benchmark Dataset: Utilize the "QUantum Interacting Dimer" (QUID) benchmark framework. QUID contains 170 non-covalent dimers modeling chemically diverse ligand-pocket motifs, with robust interaction energies established by achieving agreement of 0.5 kcal/mol between complementary Coupled Cluster (CC) and Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) methods—a "platinum standard" [9].

- Model Evaluation: Compute the interaction energy (Eint) for each dimer in the QUID set using your MLIP. The interaction energy is calculated as: Eint = Edimer - (EmonomerA + Emonomer_B).

- Accuracy Assessment: Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the MLIP-predicted E_int and the QUID benchmark values. An MAE close to or below 1 kcal/mol indicates the model has achieved chemical accuracy for this critical property.

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol: Benchmarking Molecular Dynamics Stability

Objective: To evaluate the stability and practical usability of an MLIP in molecular dynamics simulations, a common application.

Methodology (as per MOFSimBench):

- System Preparation: Select a diverse set of structures (e.g., 100 MOFs). Optimize each initial structure.

- Equilibration: Perform an NVT simulation to equilibrate the structure at the target temperature (e.g., 300K).

- Production Run: Conduct an NPT simulation for a defined period (e.g., 50 ps) at the target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

- Stability Metric: Calculate the volume change (ΔV = 1 – Vfinal / Vinitial) between the initial and final structures. A model is considered stable for a given structure if the absolute volume change is less than 10% [13]. The number of structures that remain stable across the test set is a key performance indicator.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Software and Datasets for High-Accuracy Atomistic Simulation

| Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [12] | Dataset | Massive dataset of high-accuracy computational chemistry calculations for training generalizable MLIPs. Covers biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes. |

| QUID Framework [9] | Benchmark | Provides "platinum standard" interaction energies for ligand-pocket systems to validate chemical accuracy for drug discovery applications. |

| LAMBench [11] | Benchmarking System | Evaluates Large Atomistic Models (LAMs) on generalizability, adaptability, and applicability across diverse scientific domains. |

| eSEN / UMA Models [12] | MLIP Architecture | State-of-the-art neural network potentials offering high accuracy; UMA uses a Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) to unify multiple datasets. |

| DeePEST-OS [14] | Specialized MLIP | A generic machine learning potential specifically designed for accelerating transition state searches in organic synthesis with high barrier accuracy. |

| PFP (on Matlantis) [13] | MLIP / Platform | A commercial MLIP noted for its strong balance of accuracy and high computational speed across various material simulation tasks. |

| torch-dftd [13] | Software Library | An open-source package for including dispersion corrections in MLIP predictions, critical for accurate modeling of non-covalent interactions. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Jacob's Ladder in Density Functional Theory? Jacob's Ladder is a conceptual framework for classifying density functional approximations, organized by their increasing complexity, accuracy, and computational cost. Each rung on the ladder adds more sophisticated ingredients to the exchange-correlation functional, with the goal of achieving higher accuracy for chemical predictions [15] [16]. The ladder is intended to lead users from simpler, less accurate methods toward the "heaven of chemical accuracy" [15].

Which rung of Jacob's Ladder should I choose for my project? The choice involves a trade-off. Lower rungs like LDA or GGA are computationally inexpensive but often lack the accuracy for complex chemical properties. Higher rungs like hybrid functionals are more accurate but significantly more expensive [15] [8]. Your choice should balance the required accuracy with available computational resources. For many day-to-day applications in chemistry, robust GGA or hybrid functionals offer a good compromise [15] [8].

My calculations are too slow with a hybrid functional. What can I do? Consider a multi-level approach. You can perform geometry optimizations using a faster, lower-rung functional (like a GGA) with a moderate basis set, and then execute a more accurate single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry using a higher-rung functional [17]. Studies show that reaction energies and barriers are often surprisingly insensitive to the level of theory used for geometry optimization, due to systematic error cancellation [17].

I get poor results for non-covalent interactions with my standard functional. What is wrong? This is a known limitation of many lower-rung functionals. Non-covalent interactions, such as van der Waals forces, are often poorly described by standard GGA or hybrid functionals. The solution is to use a functional that includes an empirical dispersion correction (often denoted as "-D" or "-D3") [8] [18]. For example, the r2SCAN-D4 meta-GGA functional has been developed and validated for studies of weakly interacting systems [18].

How can I be sure my DFT results are reliable? Always be skeptical of your setup. The accuracy of Kohn-Sham DFT is determined by the quality of the exchange-correlation functional approximation [15]. Furthermore, ensure your calculations are numerically converged. A clear indicator of numerical errors is a nonzero net force on a molecule; this is a symptom of unconverged electron densities or numerical approximations, which can degrade the quality of your results and any machine-learning models trained on them [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Reaction Energies or Barrier Heights

- Potential Cause 1: Outdated Functional/Basis Set Combination. Using outdated methods like B3LYP/6-31G* is a common pitfall. This combination suffers from severe inherent errors, including missing London dispersion effects and a strong basis set superposition error (BSSE) [8].

- Solution: Switch to a modern, robust functional and basis set. The table below provides recommended alternatives. Composite methods like r2SCAN-3c or B97M-V/def2-SVPD are designed to eliminate systematic errors without a high computational cost [8].

- Potential Cause 2: Insufficient Functional for the Chemical Problem. The chosen functional on Jacob's Ladder may be too low to accurately describe the electronic structure of your system.

- Solution: Climb Jacob's Ladder. If a GGA fails, try a meta-GGA or a hybrid functional. For properties like non-covalent interactions, ensure your functional includes a dispersion correction [8] [18].

Problem: Unacceptably Long Computation Times

- Potential Cause: Using a High-Rung Functional for All Calculation Steps. Applying a computationally expensive hybrid or double-hybrid functional for every step, such as geometry optimization and frequency calculation, can be prohibitively slow for large systems [8].

- Solution: Implement a multi-level protocol (a "cheap/expensive" strategy).

- Geometry Optimization: Use a cost-effective functional (e.g., a GGA or meta-GGA) with a medium-sized basis set (e.g., def2-SVP or cc-pVDZ) to find the molecular structure [17].

- High-Level Single-Point Energy Calculation: Use the optimized geometry and perform a single energy calculation with a more accurate, higher-rung functional and a larger basis set to obtain the final energy [17]. This protocol is effective because the molecular geometry is often well-described at lower levels of theory.

Problem: Non-Zero Net Forces in Datasets

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal DFT Settings and Numerical Approximations. Non-zero net forces on a molecule indicate numerical errors in the force components. This is a critical issue when generating data for training machine-learning interatomic potentials. Sources of error can include the use of the RIJCOSX approximation for evaluating integrals or DFT grids that are not tight enough [19].

- Solution: Use tightly converged computational settings.

- Disable approximations like RIJCOSX in older versions of codes like ORCA, or ensure you are using a recent version where this issue is fixed [19].

- Use the tightest grid settings available, such as DEFGRID3 in ORCA [19].

- Always check the magnitude of the net force as a sanity test for your DFT calculations.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: The Rungs of Jacob's Ladder - A Functional Comparison [15] [8] [16]

| Rung | Functional Type | Key Ingredients | Cost | Accuracy | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Density Approximation (LDA) | Local electron density only | Very Low | Low; often qualitative | Simple metals; solid-state physics |

| 2 | Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | Electron density + its gradient | Low | Moderate | Standard for solids; starting point for molecules |

| 3 | Meta-GGA | Density, gradient, kinetic energy density | Moderate | Good | Improved thermochemistry; some materials |

| 4 | Hybrid | Mix of GGA/meta-GGA + exact Hartree-Fock exchange | High | High | Mainstream for molecular chemistry |

| 5 | Double-Hybrid | Hybrid functional + non-local correlation perturbation | Very High | Very High | High-accuracy thermochemistry |

Table 2: Cost-Effective Protocol for Ion-Solvent Binding Energies [17]

| Calculation Step | Recommended Method | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | B3LYP/cc-pVTZ or B3LYP/(aug-)cc-pVDZ | Delivers reliable geometries. The smaller DZ basis offers a good speed/accuracy balance. |

| High-Level Single-Point Energy | revDSD-PBEP86-D4/def2-TZVPPD | A robust double-hybrid DFA that provides accuracy close to the gold-standard DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS benchmark. |

Visual Guide: Jacob's Ladder of DFT The following diagram illustrates the path from basic to advanced functionals, where each step upward adds computational cost but also increases potential accuracy by incorporating more physical ingredients.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for DFT Calculations

| Item | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates quantum mechanical effects of exchange and correlation energy. The core choice in any DFT calculation. | GGA: PBE [16]. Hybrid: PBE0 [16]. Range-Separated Hybrid: ωB97M-V [19]. Double-Hybrid: revDSD-PBEP86-D4 [17]. |

| Atomic Orbital Basis Set | Set of mathematical functions used to represent the electronic wavefunction. | Pople: 6-31G(d), 6-311G(2d,p) [17]. Dunning: cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ [17]. Karlsruhe: def2-SVP, def2-TZVPP [19] [17]. |

| Dispersion Correction | Empirically accounts for long-range van der Waals (dispersion) interactions, which are missing in standard functionals. | -D3, -D4 schemes [8]. Crucial for non-covalent interactions, molecular crystals, and molecule-surface interactions [18]. |

| Density-Fitting (DF) Basis | An auxiliary basis set used to expand the electron density, reducing computational cost, especially for large systems. | Required for efficient integral computation. Larger than the primary orbital basis set [20]. |

| Numerical Integration Grid | A grid of points in space for numerically evaluating the exchange-correlation potential and energy. | Tight grids (e.g., DEFGRID3) are essential for accurate forces and properties. Loose grids are a source of numerical error [19]. |

Emerging Solutions: Beyond the Traditional Ladder

Machine learning is creating new paths that circumvent the traditional cost-accuracy trade-off of Jacob's Ladder. Microsoft researchers have developed a deep-learning-powered DFT model trained on over 100,000 data points. This model learns which features are relevant for accuracy, rather than relying on the pre-defined ingredients of Jacob's Ladder, increasing accuracy without a corresponding increase in computational cost [15]. Other approaches involve creating pure, non-local, and transferable machine-learned density functionals (KDFA) that can be trained on high-level reference data like CCSD(T), offering gold-standard accuracy at a mean-field computational cost [20]. In the field of optical properties, transfer learning allows models pre-trained on thousands of inexpensive calculations to be fine-tuned with a few hundred high-fidelity calculations, effectively climbing the ladder without the prohibitive cost [21].

Fundamental DFT Concepts and Their Role in Drug Discovery

What is Density Functional Theory (DFT) and why is it used in drug discovery?

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical method used to model the electronic structure of atoms, molecules, and materials. In pharmaceutical research, DFT provides crucial insights into molecular properties that determine drug behavior, including molecular stability, reaction energies, barrier heights, and spectroscopic properties [8]. Its importance stems from an exceptional effort-to-insight and cost-to-accuracy ratio compared to alternative quantum chemical approaches, making it feasible for studying biologically relevant molecules [8].

DFT addresses what scientists call the "electron glue" - how electrons determine the stability and properties of chemical structures [7]. This capability is fundamental to predicting whether a drug candidate will bind to its target protein, how metabolic processes might transform a compound, and what electronic properties influence absorption and distribution. While more accurate wavefunction-based methods exist, they are computationally prohibitive for drug-sized molecules, whereas DFT reduces the computational cost from exponential to polynomial scaling [7].

What is the fundamental challenge with DFT's predictive power in pharmaceutical applications?

The fundamental challenge lies in the exchange-correlation (XC) functional - a small but crucial term that is universal for all molecules but for which no exact expression is known [7]. Despite being formally exact, DFT relies on practical approximations of the XC functional, creating a critical limitation for drug discovery applications.

The accuracy limitations of current XC functionals present a significant barrier to predictive drug design. Present approximations typically have errors that are 3 to 30 times larger than the chemical accuracy of 1 kcal/mol required to reliably predict experimental outcomes [7]. This accuracy gap means that instead of using computational simulations to identify the most promising drug candidates, researchers must still synthesize and test thousands of compounds in the laboratory, mirrorring the traditional trial-and-error approach in drug development [7].

Table: Comparison of Computational Methods in Drug Discovery

| Method | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Typical Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-empirical QM | Low | Very Low | Initial screening of very large compound libraries |

| Density Functional Theory | Medium | Medium | Structure optimization, reaction mechanism studies, property prediction |

| Coupled-Cluster Theory | High (Gold standard) | Very High | Final validation of key compounds, benchmark studies |

Troubleshooting Common DFT Calculation Issues

How do I resolve electron number warnings in DFT calculations?

Electron number warnings indicate a discrepancy between the expected and numerically integrated electron count, often appearing as: "WARNING: error in the number of electrons is larger than 1.0d-3" [22].

Solution: This warning signals potential numerical integration grid issues. Implement the following troubleshooting protocol:

- Select a finer integration grid (in Gaussian, use a (99,590) grid instead of smaller defaults) [23]

- Tighten the screening threshold (.SCREENING in DIRAC) [22]

- Verify result convergence by testing different grid parameters, especially when using modern functionals like SCAN, M06, or wB97 families that show high grid sensitivity [23]

Note: If the warning appears only during the first iterations when restarting from a different geometry, it may resolve itself as the calculation proceeds [22].

My DFT calculation won't converge. What strategies can help?

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures represent common challenges in DFT workflows. Implement this systematic approach:

Protocol for SCF Convergence Issues:

- Initial strategy: First perform a standard SCF calculation (not DFT), save the molecular orbital coefficients, and use them as starting points for your DFT calculation [22]. The larger HOMO-LUMO gap in SCF often facilitates convergence.

Advanced technical settings:

System-specific adjustments:

- For metallic systems or those with an odd number of electrons, specify

occupations='smearing'instead of the default fixed occupations [24] - Reduce

mixing_ndimfrom the default value of 8 to 4 to decrease memory usage and improve stability [24] - Set

diago_david_ndim=2to minimize Davidson diagonalization workspace [24]

- For metallic systems or those with an odd number of electrons, specify

Why are my free energy calculations giving inconsistent results?

Inconsistent free energy predictions often stem from three technical issues that require careful attention:

Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Grid sensitivity in modern functionals: Even functionals with low grid sensitivity for energies show significant variations in free energy calculations. Some functionals, particularly the Minnesota family (M06, M06-2X) and SCAN functionals, exhibit poor performance on smaller grids [23].

- Solution: Use a (99,590) grid or larger for all free energy calculations [23]

Rotational variance of integration grids: DFT integration grids are not perfectly rotationally invariant, meaning molecular orientation can affect results by up to 5 kcal/mol [23].

- Solution: Use larger grids (minimum (99,590)) to dramatically reduce this effect [23]

Low-frequency vibrational modes: Quasi-translational or quasi-rotational modes below 100 cm⁻¹ can artificially inflate entropy contributions [23].

- Solution: Apply the Cramer-Truhlar correction, raising all non-transition state modes below 100 cm⁻¹ to 100 cm⁻¹ for entropy calculations [23]

Symmetry number neglect: High-symmetry molecules have fewer microstates, lowering entropy. Neglecting symmetry numbers creates systematic errors [23].

- Solution: Automatically detect point groups and apply appropriate entropy corrections (e.g., RTln(2) for water vs. hydroxide, = 0.41 kcal/mol at room temperature) [23]

Advanced DFT Applications in Drug Discovery Workflows

How is machine learning transforming DFT in pharmaceutical research?

Machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing DFT applications in drug discovery through two primary approaches:

ML-Augmented DFT: ML models are being used to learn the exchange-correlation functional directly from high-accuracy data, addressing DFT's fundamental limitation [7]. Microsoft's "Skala" functional demonstrates this approach, using deep learning to extract meaningful features from electron densities and predict accurate energies without computationally expensive hand-designed features [7]. This has reached the accuracy required to reliably predict experimental outcomes for specific regions of chemical space.

ML-Accelerated Materials Modeling: Frameworks like the Materials Learning Algorithms (MALA) package replace direct DFT calculations with ML models that predict key electronic observables (local density of states, electronic density, total energy) [25]. This enables simulations at scales far beyond standard DFT, making large-scale atomistic simulations feasible for drug delivery systems and biomaterials.

Table: Machine Learning Approaches in Computational Chemistry

| Approach | Key Innovation | Demonstrated Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Deep-learned XC functionals | Learns exchange-correlation mapping from electron density using neural networks | Reaches experimental accuracy within trained chemical space; generalizes to unseen molecules [7] |

| Scalable ML frameworks (MALA) | Predicts electronic observables using local atomic environment descriptors | Enables simulations of thousands of atoms beyond standard DFT limits [25] |

| Quantum-classical hybrid workflows | Combines quantum processor data with classical supercomputing | Approximates electronic structure of complex systems like iron-sulfur clusters [26] |

What are the best-practice DFT protocols for drug discovery applications?

Implement these validated protocols to balance accuracy and computational cost:

Protocol Selection Framework:

Specific Recommendations:

- Avoid outdated defaults: The popular B3LYP/6-31G* combination suffers from severe inherent errors, including missing London dispersion effects and strong basis set superposition error [8].

Modern composite methods: Use robust, modern alternatives like:

Multi-level approaches: Combine different theory levels - cheaper methods for structure optimization, higher-level methods for energy calculations - to optimize the accuracy-efficiency balance [8].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table: Key Software and Computational Tools for DFT in Drug Discovery

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skala | Deep-learned functional | Exchange-correlation energy prediction | High-accuracy energy calculations for ligand-target interactions [7] |

| MALA | Machine learning framework | Electronic structure prediction | Large-scale simulation of drug delivery systems and biomaterials [25] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT software | First-principles electronic structure | Materials modeling for drug delivery systems [25] |

| LAMMPS | Molecular dynamics | Particle-based modeling | Large-scale simulation of drug-polymer systems [25] |

| pymsym | Symmetry analysis | Automatic symmetry detection | Correct entropy calculations for symmetric molecules [23] |

What emerging technologies will shape the future of computational drug discovery?

Several cutting-edge approaches are pushing the boundaries of computational drug discovery:

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Workflows: Integration of quantum processors with classical supercomputing enables investigation of complex electronic structures that challenge conventional methods [26]. This approach has been applied to iron-sulfur clusters (essential in metabolic proteins) using active spaces of 50-54 electrons in 36 orbitals - problems several orders of magnitude beyond exact diagonalization [26].

Closed-loop Automation: Advanced workflows now enable seamless iteration between quantum calculations and classical data analysis, as demonstrated in the integration of Heron quantum processors with 152,064 classical nodes of the Fugaku supercomputer [26].

Ultra-large Virtual Screening: Structure-based virtual screening of gigascale chemical spaces containing billions of compounds allows researchers to rapidly identify diverse, potent, and drug-like ligands [27]. These approaches dramatically increase efficiency, with some platforms reporting identification of clinical candidates after synthesizing only 78 molecules from an initial screen of 8.2 billion compounds [27].

This emerging paradigm represents a fundamental shift from computation as an interpretive tool to a predictive engine in drug discovery, potentially reducing the need for large-scale experimental screening while increasing the success rate of candidate identification [27]. As these technologies mature, they promise to rebalance the cost-accuracy equation in pharmaceutical development, making computational prediction increasingly central to therapeutic discovery.

AI and Machine Learning in DFT: Pioneering Methods for Enhanced Accuracy and Efficiency

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is the most widely used electronic structure method for predicting the properties of molecules and materials, serving as a fundamental tool for researchers in drug development and materials science [28]. In principle, DFT is an exact reformulation of the Schrödinger equation, but in practice, all applications rely on approximations of the unknown exchange-correlation (XC) functional. For decades, the development of XC functionals has followed the paradigm of "Jacob's Ladder," where increasingly complex, hand-designed features improve accuracy at the expense of computational efficiency [7]. Despite these efforts, no traditional approximation has consistently achieved chemical accuracy—typically defined as errors below 1 kcal/mol—which is essential for reliably predicting experimental outcomes [28]. This fundamental limitation has prevented computational chemistry from fulfilling its potential as a truly predictive tool, forcing researchers to continue relying heavily on laboratory experiments for molecule and material design [7].

The emergence of deep learning offers a transformative approach to this long-standing challenge. By leveraging modern machine learning architectures and unprecedented volumes of high-accuracy reference data, researchers can now bypass the limitations of hand-crafted functional design. These new approaches learn meaningful representations of the electron density directly from data, potentially achieving the elusive balance between computational efficiency and chemical accuracy [28] [7]. This technical support document provides troubleshooting guidance and best practices for researchers implementing these cutting-edge deep learning approaches for XC functional development, with particular attention to balancing computational cost and accuracy—the central challenge in DFT methods research.

Key Machine-Learned XC Functionals and Frameworks

The table below summarizes the major deep-learning-based XC functionals and frameworks discussed in this guide, highlighting their distinctive approaches and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Machine-Learned XC Functional Approaches

| Functional/Framework | Development Team | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Computational Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skala [28] [7] | Microsoft Research & Academic Partners | Deep learning model learning directly from electron density data; trained on ~150,000 high-accuracy energy differences. | Reaches chemical accuracy (~1 kcal/mol) for atomization energies of main-group molecules. | Cost of semi-local DFT; ~10% of standard hybrid functional cost. |

| NeuralXC [29] | Academic Research Consortium | Machine-learned correction built on top of a baseline functional (e.g., PBE); uses atom-centered density descriptors. | Lifts baseline functional accuracy toward coupled-cluster (CCSD(T)) level for specific systems (e.g., water). | Similar to the underlying baseline functional during SCF. |

| MALA [30] | Academic Research Team | Predicts the local density of states (LDOS) via neural networks using bispectrum descriptors, enabling large-scale electronic structure prediction. | Demonstrates up to 3-order-of-magnitude speedup on tractable systems; enables 100,000+ atom simulations. | Linear scaling with system size, circumventing cubic scaling of conventional DFT. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What fundamentally differentiates a deep learning approach to the XC functional from traditional methods?

Traditional XC functionals are constructed using a limited set of hand-crafted mathematical forms and descriptors based on physical intuition (e.g., the electron density and its derivatives) [7]. This process is methodical but has seen diminishing returns. Deep learning approaches, such as Skala, bypass this manual design by using neural networks to learn the complex mapping between the electron density and the XC energy directly from vast datasets [28]. This data-driven approach avoids human bias in feature selection and can capture complex patterns that are difficult to encode in explicit mathematical formulas.

Q2: What type and volume of training data are required to develop a functional like Skala?

Successfully training a functional like Skala requires an unprecedented volume of high-accuracy reference data. The development involved generating a dataset two orders of magnitude larger than previous efforts, comprising approximately 150,000 highly accurate energy differences for atoms and sp molecules [28] [7]. This data is typically generated using computationally intensive wavefunction-based methods (e.g., CCSD(T)) which are considered the "gold standard" for accuracy but are too costly for routine application. The key is that DFT, and the learned functional, can then generalize from this high-accuracy data for small systems to larger, more complex molecules [7].

Q3: How does the computational cost of a deep-learned functional compare to traditional semi-local or hybrid functionals?

A primary advantage of deep-learned functionals like Skala is that they retain the favorable computational scaling of semi-local functionals while achieving an accuracy that is competitive with, or even surpasses, more expensive hybrid functionals [28]. It is reported that Skala's computational cost is only about 10% of the cost of standard hybrid functionals and about 1% of the cost of local hybrids [7]. This favorable cost profile is maintained for larger systems, making it a scalable solution for practical research applications.

Q4: Are machine-learned functionals transferable beyond their specific training domain?

This is a critical area of ongoing research. Evidence suggests that with a sufficiently diverse and large training set, these functionals can demonstrate significant transferability. For instance, Skala was initially trained on atomization energies but showed competitive accuracy across general main-group chemistry when a modest amount of additional, diverse data was incorporated [28]. Similarly, NeuralXC functionals have shown promising transferability from small molecules to the condensed phase and within similar types of chemical bonding [29]. However, performance may degrade far outside the training domain, so careful validation is necessary for new application areas.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor Convergence or Instability in Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Discontinuities or Non-Smoothness in the ML Functional. The learned functional may introduce numerical instabilities that are not present in traditional, smoother functionals.

- Solution: Tweak SCF convergence algorithms. Consider using damping, DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace), or other advanced convergence helpers that are standard in your DFT code. Start calculations from a well-converged density obtained from a standard functional before switching to the ML functional.

- Cause: Inadequate Functional Derivative. The potential VML is obtained via the functional derivative of the learned energy EML. If this derivative is approximated or implemented imperfectly, it can cause SCF instability [29].

- Solution: Consult the functional's documentation to understand how the potential is calculated. Ensure you are using the correct, intended version of the functional and its corresponding potential implementation.

Problem: The Functional Fails to Generalize to New Molecular Systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Data Mismatch Between Training and Application. The functional was trained on a specific region of chemical space (e.g., main-group molecules) and is being applied to a different one (e.g., transition metal complexes or strongly correlated systems) [28] [29].

- Solution: Always validate the functional's performance on a set of molecules relevant to your research before full deployment. If performance is poor, the functional may not be suitable for your specific chemical space without further retraining. Consider using a multi-level approach, falling back on a more robust traditional functional for certain system types.

- Cause: Insufficient Training Data Diversity. The model may have learned spurious correlations specific to its limited training set.

- Solution: This is a fundamental limitation that can only be addressed by the functional developers by expanding the training dataset to cover a broader swath of chemical space. As a user, you should be aware of the published scope and limitations of the functional.

Problem: High Computational Overhead During Training or Inference

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Large and Complex Neural Network Architecture. The model may be inherently computationally expensive to evaluate.

- Solution: For inference, ensure you are using optimized code and, if available, GPU acceleration. The cost, while potentially higher than a simple GGA, should still be significantly lower than a hybrid functional [7]. For training, this is a development-phase challenge, but leveraging distributed computing on cloud platforms (as done for Skala's data generation) is often necessary [7].

- Cause: Inefficient Descriptor Calculation. Frameworks like NeuralXC and MALA rely on the calculation of atomic descriptors (e.g., atom-centered basis projections or bispectrum components) [30] [29].

- Solution: Profile your code to identify bottlenecks. Utilize highly optimized and parallelized libraries for descriptor calculation where possible.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking a New ML Functional Against Standard Methods

Purpose: To validate the accuracy and establish the performance boundaries of a new machine-learned functional for your specific research domain.

Methodology:

- Select a Benchmark Set: Choose a well-established set of molecules and properties relevant to your work (e.g., the W4-17 dataset for thermochemistry [7]).

- Define Comparison Methods: Select a range of standard DFT functionals for comparison (e.g., a GGA like PBE, a meta-GGA like SCAN, and a hybrid like PBE0).

- Calculate Target Properties: Compute the target properties (e.g., atomization energies, reaction barriers, bond lengths) using the ML functional and all comparison methods.

- Establish Ground Truth: Compare all results against high-accuracy reference data, either from experimental results or high-level wavefunction calculations (e.g., CCSD(T)).

- Analyze Statistics: Calculate mean absolute errors (MAE), root-mean-square errors (RMSE), and maximum deviations for each method.

Table 2: Example Benchmarking Results for Atomization Energies (Hypothetical Data)

| Functional | MAE (kcal/mol) | RMSE (kcal/mol) | Max Error (kcal/mol) | Relative Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | 8.5 | 10.2 | 25.3 | 1.0 |

| PBE0 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 12.1 | 10.0 |

| Skala (ML) | 1.1 | 1.5 | 4.2 | ~1.5 |

| Target: Chemical Accuracy | < 1.0 |

Protocol: Generating High-Accuracy Training Data via Wavefunction Methods

Purpose: To create a dataset of molecular energies and structures accurate enough to train a machine-learned XC functional.

Methodology (as implemented for Skala [7]):

- Structure Generation: Build a scalable pipeline to produce a highly diverse set of molecular structures covering the target chemical space (e.g., main-group elements).

- Level of Theory Selection: In consultation with a domain expert, select an appropriate high-accuracy wavefunction method (e.g., CCSD(T)) with a large, correlation-consistent basis set. This step requires significant expertise as methodological choices profoundly impact the final accuracy.

- High-Performance Computing (HPC): Execute the wavefunction calculations on a large-scale HPC cluster. The Microsoft team, for example, leveraged substantial Azure compute resources.

- Curation and Storage: Collect the resulting energies (and optionally forces) into a structured database, ensuring consistency and metadata integrity. A large part of such datasets is often released to the public to foster further research [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Computational "Reagents" for ML-XC Functional Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to ML-XC Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO [31] [30] | DFT Software | Open-source suite for electronic-structure calculations using plane waves and pseudopotentials. | Often used to generate baseline data and for post-processing of electronic structure information in workflows like MALA. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow [32] | Machine Learning Framework | Open-source libraries for building and training deep neural networks. | The foundation for building and training the neural network models that represent the XC functional (e.g., Skala, NeuralXC). |

| LAMMPS [30] | Molecular Dynamics | Classical molecular dynamics simulator with extensive support for material modeling. | Used in workflows like MALA for calculating atomic environment descriptors (bispectrum components). |

| GPUs (NVIDIA) [32] | Hardware | Graphics Processing Units for parallel computation. | Crucial for accelerating both the training of large neural network functionals and the inference (evaluation) during SCF cycles. |

| Cloud HPC (e.g., Azure) [7] | Computing Infrastructure | On-demand high-performance computing resources. | Enables the massive, scalable wavefunction calculations required to generate training datasets of sufficient size and diversity. |

Workflow and System Architecture Diagrams

High-Level Workflow for Developing an ML-Based XC Functional

Diagram Title: ML-XC Functional Development Workflow

Data Generation and Training Pipeline Architecture

Diagram Title: ML-XC Data and Training Pipeline

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of a highly accurate deep learning model failing when applied to new, real-world data?

This failure, known as poor generalization, often stems from overfitting and data mismatch [33]. Overfitting occurs when a model learns the patterns of the training data too well, including its noise, but fails to capture the underlying universal truth. Data mismatch happens when the training data (e.g., clean, simulated data) is not representative of the real-world data (e.g., noisy experimental data) the model encounters later [34]. To prevent this, ensure your training set has sufficient volume, variety, and balance, and employ techniques like regularization and cross-validation [33].

FAQ 2: My model's training is unacceptably slow. What are the first steps to diagnose and fix this?

First, profile your code to identify the bottleneck. The issue could be related to:

- Data Pipeline: Inefficient data loading or pre-processing can slow down the entire workflow. Optimize these steps and ensure they run asynchronously [34].

- Model Architecture: An overly complex model with too many parameters demands more computation. Consider designing a more lightweight network or applying model compression techniques like pruning [34] [33].

- Hardware Utilization: Check if the process is efficiently using available GPU and CPU resources, ensuring high utilization without one constantly waiting for the other [34].

FAQ 3: How can I improve my model's performance when I have very limited experimental data?

A promising approach is Deep Active Optimization, which iteratively finds optimal solutions with minimal data [35]. Frameworks like DANTE use a deep neural surrogate model and a guided tree search to select the most informative data points to sample next, dramatically reducing the required number of experiments or costly simulations [35]. This is particularly effective for high-dimensional problems where traditional methods struggle.

FAQ 4: Are there specific deep learning optimization techniques that can reduce model size without a major drop in accuracy?

Yes, two key techniques are pruning and quantization [33].

- Pruning identifies and removes unnecessary connections or weights in a neural network that contribute little to the output.

- Quantization reduces the numerical precision of the model's parameters (e.g., from 32-bit floating-point to 8-bit integers), which can shrink model size by 75% or more. Using quantization-aware training during the learning process, rather than applying it after, typically preserves more accuracy [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model fails to converge during training.

- Check Your Learning Rate: A learning rate that is too high can cause the model to overshoot the optimal solution, while one that is too low can make training impossibly slow. Use hyperparameter optimization tools like Optuna to find an optimal value [33].

- Inspect and Preprocess Data: Look for and properly treat missing values and outliers, as they can destabilize training and lead to a biased model [36]. Normalize or scale your input features to a consistent range.

- Review Model Architecture: Ensure the architecture is suitable for your problem. A model that is too simple may not capture the necessary patterns.

Issue: High computational cost makes the project infeasible.

- Adopt a Lightweight Network: Design your network for efficiency from the start. The LiteLoc framework, for example, uses dilated convolutions and a simplified U-Net to achieve high precision with low computational overhead, requiring far fewer operations than comparable models [34].

- Implement Parallel Processing: Maximize your hardware by running data pre-/post-processing on the CPU asynchronously while the GPU handles network inference [34]. Frameworks like LiteLoc are designed for parallel processing across multiple GPUs without communication overhead.

- Use Model Compression: Apply the pruning and quantization strategies mentioned in the FAQs to reduce the final model's computational demands [33].

Issue: Model is stuck in a local optimum and cannot find a better solution.

- Implement Guided Exploration: The DANTE pipeline addresses this with mechanisms like conditional selection and local backpropagation [35]. Conditional selection encourages the search to move towards higher-value candidates, while local backpropagation helps the algorithm escape local optima by updating visitation data in a way that prevents it from repeatedly visiting the same dead ends [35].

Quantitative Data on Model Performance and Cost

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models in Scientific Applications

| Model / Framework | Application Area | Key Performance Metric | Result | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DANTE [35] | General High-Dimensional Optimization | Success Rate (Global Optimum) | 80-100% on synthetic functions (up to 2000D) | Requires only ~500 data points |

| Skala XC Functional [37] | Quantum Chemistry (DFT) | Prediction Error (Molecular Energies) | ~50% lower than ωB97M-V functional | Training data: ~150,000 reactions |

| LiteLoc Network [34] | Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy | Localization Precision | Approaches theoretical limit (Cramér-Rao Lower Bound) | 1.33M parameters, 71.08 GFLOPs |

| ScaleDL [38] | Distributed DL Workloads | Runtime Prediction Error | 6x lower MRE vs. baselines | Not Specified |

Table 2: AI Model Training Cost Benchmarks (Compute-Only Expenses) [39]

| Model | Organization | Year | Training Cost (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-3 | OpenAI | 2020 | $4.6 million |

| GPT-4 | OpenAI | 2023 | $78 million |

| DeepSeek-V3 | DeepSeek AI | 2024 | $5.576 million |

| Gemini Ultra | 2024 | $191 million |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Active Optimization with DANTE for Limited-Data Scenarios [35]

Objective: To find superior solutions to complex, high-dimensional problems where data from experiments or simulations is severely limited. Methodology:

- Initialization: Start with a small initial dataset (e.g., ~200 data points).

- Surrogate Model Training: Train a deep neural network (DNN) as a surrogate model to approximate the complex system's solution space.

- Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (NTE): a. Conditional Selection: From a root node, generate new candidate solutions (leaf nodes). A leaf node becomes the new root only if its Data-driven Upper Confidence Bound (DUCB) is higher than the root's, preventing value deterioration. b. Stochastic Rollout: Expand the new root node stochastically and perform a local backpropagation, which updates only the nodes between the root and the selected leaf to avoid local optima.

- Validation & Iteration: The top candidate solutions from NTE are evaluated using the validation source (e.g., a real experiment or simulation). The newly labeled data is fed back into the database, and the process repeats.

Protocol 2: Developing a Machine-Learned Exchange-Correlation Functional (Skala XC) [37]

Objective: To create a more accurate Density Functional Theory (DFT) model for calculating molecular properties of small molecules. Methodology:

- Data Curation: Create a large, high-quality database of reference calculations. For Skala XC, this involved about 150,000 reaction energies for molecules with five or fewer non-carbon atoms.

- Model Selection and Training: Employ a complex deep learning algorithm, incorporating tools from large language models, to infer the exchange-correlation functional from the training data.

- Validation: Benchmark the new functional's performance against established, high-performing functionals (like ωB97M-V) on a test set of molecules. Key metrics include prediction error for reaction energies and performance on molecules containing metal atoms, which were not in the training set.

Workflow and System Diagrams

DANTE's Active Optimization Pipeline [35]

Scalable & Parallel SMLM Analysis [34]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for AI-Accelerated Electrocatalyst Design [40]

| Item / Concept | Type | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Statistical Descriptors | Data Input | Low-cost, system-agnostic descriptors (e.g., elemental properties from Magpie) for rapid, wide-angle screening of chemical space. |

| Electronic-Structure Descriptors | Data Input | Descriptors (e.g., d-band center, orbital occupancy) from DFT that encode essential catalytic reactivity, used for finer screening. |

| Geometric/Microenvironment Descriptors | Data Input | Descriptors (e.g., interatomic distances, coordination numbers) that capture local structure-function relationships in complex materials. |

| Customized Composite Descriptors | Data Input | Physically meaningful, low-dimensional descriptors (e.g., ARSC, FCSSI) that combine multiple factors to improve accuracy and interpretability. |

| Tree Ensemble Models (GBR, XGBoost) | ML Algorithm | Powerful for medium-to-large datasets with highly nonlinear structure-property relationships; automatically captures complex interactions. |

| Kernel Methods (SVR) | ML Algorithm | Particularly effective and robust in small-data settings, especially when used with compact, physics-informed feature sets. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub