Benchmarking Bond Energy Accuracy: A Practical Guide to Electronic Structure Methods for Research and Drug Development

Accurately predicting bond dissociation enthalpies (BDEs) and interaction energies is critical for advancing research in catalysis, material science, and rational drug design.

Benchmarking Bond Energy Accuracy: A Practical Guide to Electronic Structure Methods for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

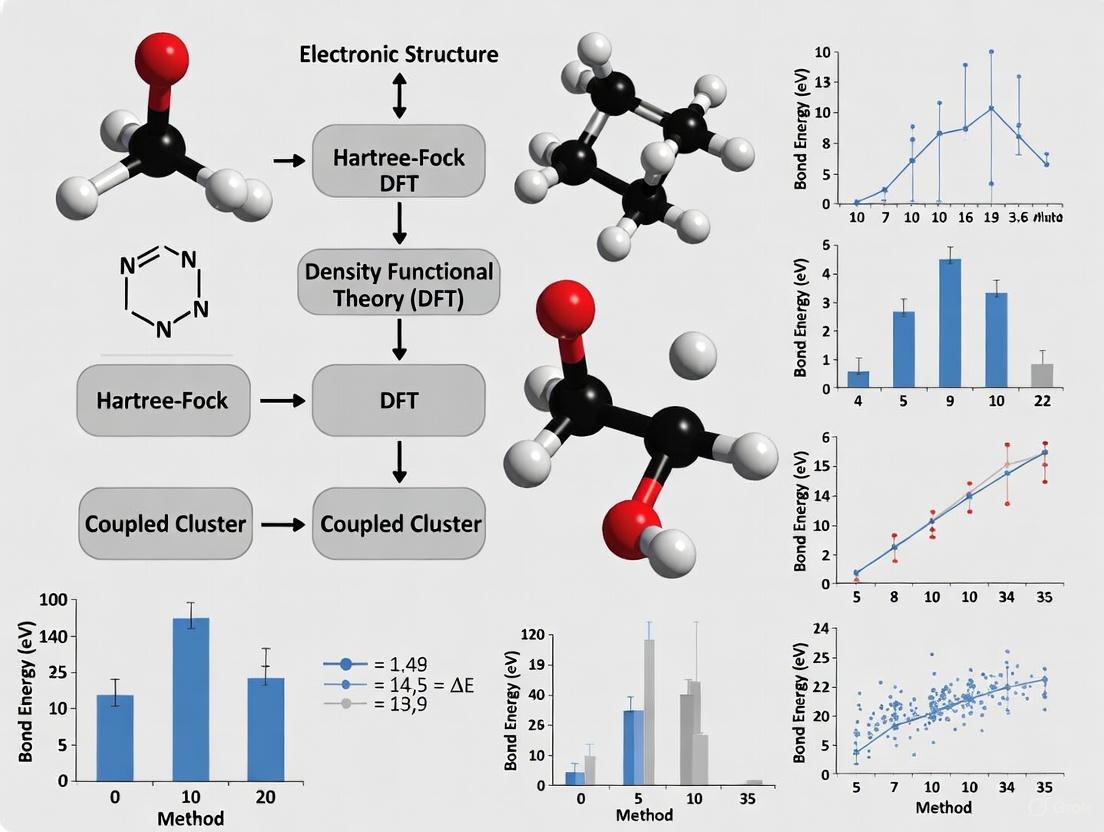

Accurately predicting bond dissociation enthalpies (BDEs) and interaction energies is critical for advancing research in catalysis, material science, and rational drug design. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of bond energy calculation, from basic thermodynamic definitions to advanced quantum mechanical models. We survey the current landscape of computational methods—including density functional theory (DFT), semiempirical approaches, and neural network potentials—benchmarking their accuracy and computational cost against experimental data. The content further delivers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing calculations, validates methods through comparative analysis of modern benchmark sets like ExpBDE54, and concludes with actionable insights for selecting the most efficient computational workflow for specific biomedical applications.

The Fundamentals of Bond Energy: From Theoretical Concepts to Experimental Benchmarks

Defining Bond Energy, Enthalpy, and Cohesive Energy in Chemical Systems

In computational chemistry and materials science, accurately predicting the energy associated with forming and breaking bonds is fundamental to understanding stability, reactivity, and properties of molecules and materials. The accuracy of these predictions hinges on the choice of electronic structure method. This guide compares the performance of different computational approaches for determining bond energy, enthalpy, and cohesive energy, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies.

Bond Energy (or Bond Dissociation Energy, BDE) is defined as the energy required to break a specific chemical bond in a molecule via homolytic cleavage in the gaseous state, resulting in two radical fragments [1] [2]. It is a measure of bond strength; a higher bond energy indicates a stronger, more stable bond. For example, the C-H bond in methane (CH₄) has a bond energy of approximately 104 kcal/mol [2]. Bond energies are correlated with the stability of the resulting radical species; low bond energies often reflect the formation of stable free radicals [2].

Bond Enthalpy is typically used interchangeably with bond energy in many contexts, representing the average energy required to break one mole of a specific type of bond in the gaseous state [1].

Cohesive Energy is the energy required to decompose a solid material or nanocluster into its constituent isolated atoms [3] [4]. It represents the total binding energy of the material and is a crucial parameter for predicting thermodynamic stability. For nanoparticles and nanoclusters, cohesive energy exhibits strong size dependence, decreasing with particle size due to the increased surface-to-volume ratio and quantum confinement effects [3] [4].

Performance Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods

The accuracy of predicting these energy quantities varies significantly across computational methods. The following table summarizes the key characteristics, accuracy, and computational cost of prominent electronic structure techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for Energy Calculations

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Typical Accuracy | Computational Cost | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled-Cluster (CCSD(T)) | Gold-standard wavefunction theory [5] | Chemical Accuracy (< 1 kcal/mol) [5] | Very High (O(N⁷)) [5] | Small molecules (tens of atoms) [5] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron density functionals [6] [5] | Variable; can be good but not uniform [5] | Moderate (O(N³)) [5] | Medium/large systems (hundreds of atoms) [5] |

| Machine Learning (e.g., MEHnet) | Trained on high-level data (e.g., CCSD(T)) [5] | Near-CCSD(T) accuracy [5] | Low (after training) | High-throughput screening of large systems [5] |

| Bond Energy Model (BEM) | Empirical model based on bond counting [3] [4] | Lower; depends on parameterization [4] | Very Low | Large nanoparticles for trend analysis [3] |

The performance comparison reveals a direct trade-off between accuracy and computational scalability. CCSD(T) is the undisputed benchmark for accuracy on small systems. DFT provides the best balance of accuracy and system size for many materials science applications, though its performance depends heavily on the chosen exchange-correlation functional [6]. Emerging machine learning potentials, like MEHnet, show promise in bridging this gap by offering CCSD(T)-level accuracy at a fraction of the cost, enabling the study of thousands of atoms [5].

Table 2: Illustrative Bond Energy Data from Different Methodologies

| Bond / System | Experimental / Reference Value | CCSD(T) Prediction | GGA-DFT Prediction | Empirical Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-H (in CH₄) | 104 kcal/mol [2] | Near exact [5] | ~100-105 kcal/mol (functional dependent) | - |

| H⁺·N₂ Bond Energy | 113.7 kcal/mol [7] | - | - | 141.5 kcal/mol (STO-3G) [7] |

| Cohesive Energy of Pt Nanocluster | - | -2.95 eV/atom (3-layer) [4] | -2.5 eV/atom (Bond Energy Model) [4] | - |

| Band Gap of BaZrO₃ | 4.7-4.9 eV (indirect) [6] | - | ~3.1-3.2 eV (GGA/LDA) [6] | - |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol for Calculating Cohesive Energy via First-Principles DFT

This protocol is widely used for determining the cohesive energy of nanoclusters and solid-state materials [4].

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full structural relaxation of the nanoparticle or crystal system using DFT (e.g., VASP, CASTEP) until the forces on atoms are minimized (e.g., below 0.01 eV/Å) [4] [6].

- Total Energy Calculation: Calculate the total energy (E_tot) of the fully optimized system.

- Atomic Energy Calculation: Calculate the energy of an isolated, single constituent atom (E_atom) of the material.

- Cohesive Energy Computation: Calculate the cohesive energy per atom (Ecoh) using the formula: *Ecoh = Eatom - Etot / n* where n is the number of atoms in the system [4].

Protocol for Bond Energy Decomposition Analysis (ADF)

This protocol, as implemented in the ADF software, decomposes the bond energy into chemically meaningful components [8].

- Fragment Definition: Define the molecular system as two or more interacting fragments (e.g., a base and a substrate).

- Preparation Energy: Calculate the energy required (ΔE_prep) to deform the isolated fragments from their equilibrium geometry to the geometry they adopt in the final molecule.

- Interaction Energy Decomposition: Calculate the interaction energy (ΔEint) between the prepared fragments and decompose it as follows:

- Electrostatic Interaction (ΔVelst): The classical attraction between the unperturbed charge distributions of the fragments.

- Pauli Repulsion (ΔEPauli): The destabilizing energy arising from the antisymmetrization of the fragment wavefunctions, responsible for steric repulsion.

- Orbital Interaction (ΔEoi): The energy from electron pair bonding, charge transfer, and polarization [8].

Workflow for High-Throughput Screening with Machine Learning

This modern workflow accelerates the prediction of bond-related energies with high accuracy [5].

- Training Set Generation: Perform CCSD(T) calculations on a diverse set of small molecules (typically up to 10 atoms) to generate a reference dataset.

- Neural Network Training: Train a specialized equivariant graph neural network (e.g., MEHnet) on this dataset. The model learns to map molecular structures to electronic properties.

- Property Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the total energy, cohesive energy, bond energies, and other electronic properties (dipole moment, polarizability, excitation gaps) for new, larger molecules (thousands of atoms) at near-CCSD(T) accuracy and low computational cost [5].

Diagram 1: Method selection workflow for accurate energy prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Energy Calculations

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | First-principles DFT code using PAW pseudopotentials [4]. | Calculating size-dependent cohesive energies of transition-metal nanoclusters [4]. |

| ADF | DFT software specializing in chemical bonding analysis [8]. | Performing bond energy decomposition analysis (Morokuma-type) [8]. |

| CASTEP | First-principles DFT code for solid-state materials [6]. | Studying cohesive energies and phase stability of perovskites like BaZrO₃ [6]. |

| Gaussian | Versatile quantum chemistry package [7]. | Calculating sequential bond energies in molecular clusters (e.g., H⁺·N₂) [7]. |

| LAMMPS | Classical molecular dynamics simulator [9]. | Calculating cohesive energy density in molecular systems using force fields [9]. |

| MEHnet | Multi-task equivariant graph neural network [5]. | High-throughput screening of molecular properties with CCSD(T)-level accuracy [5]. |

The accuracy of bond energy, enthalpy, and cohesive energy predictions is intrinsically linked to the chosen electronic structure method. While CCSD(T) remains the gold standard for small systems, its computational cost is prohibitive for larger molecules and materials. DFT offers a practical balance for many applications but suffers from functional-dependent accuracy. The emerging paradigm of machine-learning potentials trained on high-level quantum chemical data represents a transformative advance, promising to deliver benchmark accuracy across previously inaccessible length scales, thereby accelerating the discovery of new molecules and materials in fields ranging from drug development to energy storage.

Lattice energy, the energy associated with the formation of an ionic lattice from its gaseous ions, is a fundamental property that dictates the stability, solubility, and overall thermodynamics of ionic compounds [10] [11]. A precise understanding of this parameter is crucial for researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development where the salt forms of active pharmaceutical ingredients can significantly impact stability and bioavailability. However, determining a single, definitive value for lattice energy is not straightforward, as it sits at the intersection of theoretical calculation and experimental derivation. This guide objectively explores the two primary approaches for determining lattice energy—the theoretical electrostatic model and the experimental Born-Haber cycle—and compares their underlying assumptions, protocols, and resulting values. Framed within a broader thesis on the accuracy of electronic structure methods for bond energies, this analysis highlights how the divergence between these values provides profound insight into the true nature of chemical bonding, often revealing significant covalent character in seemingly ionic compounds [12].

Fundamental Concepts: Defining Lattice Energy

The term "lattice energy" itself requires careful definition, as it is used in two contradictory ways in the literature. To avoid confusion, it is essential to qualify the term based on the direction of the process [10] [13].

- Lattice Dissociation Energy: The energy required to convert one mole of a solid ionic crystal into its separated gaseous ions. This process is always endothermic (positive value) [13]. For example, the lattice dissociation energy for NaCl is +787 kJ mol⁻¹ [10].

- Lattice Formation Energy: The energy released when one mole of a solid ionic crystal is formed from its separated gaseous ions. This process is always exothermic (negative value) [13]. For NaCl, this is -787 kJ mol⁻¹ [10].

For the remainder of this article, "lattice energy" will refer to the lattice formation energy, consistent with its use in many thermodynamic cycles. The magnitude of lattice energy is primarily governed by two factors [10] [13]:

- Ionic Charges: Higher charges on the ions lead to stronger electrostatic attraction. For instance, MgO (with Mg²⁺ and O²⁻) has a much larger lattice energy than NaCl (with Na⁺ and Cl⁻) [10].

- Ionic Radii: Smaller ions can get closer together, increasing the electrostatic attraction and thus the lattice energy. This is observed down groups in the periodic table, where lattice energies decrease as the ions become larger [10].

Methodological Approaches: A Comparative Framework

The determination of lattice energy follows two distinct philosophical and methodological pathways. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and key differences between these two primary approaches.

The Born-Haber Cycle: Experimental Derivation

The Born-Haber cycle is an application of Hess's Law that allows for the indirect determination of lattice energy from other, measurable thermochemical quantities [11] [14]. It is considered the source of the "experimental" or "actual" lattice energy value [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for deriving the lattice energy of a generic ionic compound, MX, where M is a metal and X is a non-metal.

To calculate the lattice energy, the sum of the enthalpy changes for the indirect path (Steps 1-5) is set equal to the direct enthalpy of formation, leading to the following equation [14]:

LE = ΔHf - [ΔHsub(M) + IE(M) + 1/2D(X-X) + EA(X)]

- Example Calculation for NaCl [13]:

- ΔHf (NaCl) = -411 kJ mol⁻¹

- ΔHsub (Na) = +108 kJ mol⁻¹

- IE (Na) = +496 kJ mol⁻¹

- 1/2D (Cl-Cl) = +122 kJ mol⁻¹

- EA (Cl) = -349 kJ mol⁻¹

- LE = -411 - (108 + 496 + 122 - 349) = -788 kJ mol⁻¹

The accuracy of the final lattice energy is entirely dependent on the precision of the input thermochemical data [14].

Theoretical Calculations: Electrostatic Models

Theoretical lattice energy is calculated from first principles using a physics-based approach that models the ionic crystal as a collection of point charges interacting through electrostatic forces [13] [12]. The most refined of these models is the Born-Landé equation [14]:

ΔHlattice = (NA * M * z⁺ * z⁻ * e²) / (4 * π * ε₀ * r₀) * (1 - 1/n)

Where:

- N_A = Avogadro's number

- M = Madelung constant (depends on the crystal structure)

- z⁺, z⁻ = Charges of the cation and anion

- e = Elementary charge

- ε₀ = Permittivity of free space

- r₀ = Distance between ion centers

- n = Born exponent (related to the compressibility of the solid)

This method assumes a perfectly ionic compound with no covalent character, only electrostatic interactions between ions, and a perfect crystal lattice [12].

Data Comparison: Theoretical vs. Experimental Lattice Energies

The comparison between theoretical (calculated) and experimental (Born-Haber) lattice energies is not merely a check for accuracy, but a powerful diagnostic tool for understanding chemical bonding.

Table 1: Comparison of Theoretical and Experimental Lattice Energies for Selected Halides [12]

| Compound | Theoretical Lattice Energy (kJ mol⁻¹) | Experimental Lattice Energy (kJ mol⁻¹) | Difference (kJ mol⁻¹) | Implied Covalent Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgF | ~High | ~High | Small | Low |

| AgI | ~High | Lower | Large | High |

Interpreting the Data

- Small Difference: If the experimental value is very close to the theoretical value, the assumption of a highly ionic compound is valid. This is typical for compounds with cations of low charge density/polarizing power and anions that are small and non-polarizable (e.g., AgF, NaCl) [12].

- Large Difference: A significant discrepancy, where the experimental lattice energy is more negative (or less positive) than the theoretical value, indicates a failure of the purely ionic model. This signals significant covalent character in the bonding. This occurs with cations of high charge density/polarizing power that distort the electron cloud of large, easily polarizable anions (e.g., AgI) [12].

The Computational Chemistry Perspective: Benchmarking Electronic Structure Methods

The accuracy of computational chemistry methods for predicting bond energies can be benchmarked against experimental datasets like ExpBDE54, a benchmark of 54 experimental homolytic bond dissociation enthalpies (BDEs) for small molecules [15]. This is directly analogous to using Born-Haber cycles to benchmark theoretical lattice energies.

Table 2: Performance of Selected Computational Methods for BDE Prediction (ExpBDE54 Benchmark) [15]

| Computational Method | Class | Speed (Relative) | Accuracy (RMSE, kcal mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| g-xTB//GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical | Fastest | 4.7 |

| OMol25's eSEN | Neural Network Potential | Fast | 3.6 |

| r²SCAN-3c//GFN2-xTB | Meta-GGA DFT | Medium | ~4.0 |

| r²SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD | Meta-GGA DFT | Slow | 3.6 |

| ωB97M-D3BJ/def2-TZVPPD | Hybrid DFT | Slow | 3.7 |

Key Insights from Computational Benchmarking

- Linear Regression Corrections: Raw electronic bond dissociation energies (eBDEs) from computational methods show a strong linear relationship with experimental BDEs but require empirical correction for zero-point energy, enthalpy, and relativistic effects to achieve high accuracy [15].

- Pareto Frontier of Methods: The benchmarking identifies a "Pareto frontier" of methods that offer the best trade-off between speed and accuracy. For rapid screening on CPU, semiempirical methods like g-xTB//GFN2-xTB are optimal, while for higher accuracy, neural network potentials like eSEN or composite DFT methods like r²SCAN-3c represent the best choices [15].

- Basis Set Convergence: For density functional theory (DFT) methods, moving to larger basis sets beyond def2-TZVPPD offers negligible improvement in BDE accuracy while significantly increasing computational cost, suggesting the limit of a purely electronic energy approach has been nearly reached [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key solutions and materials essential for research in experimental thermochemistry and computational modeling of bond energies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal & Gas Samples | Essential for accurate calorimetric measurements of standard enthalpies of formation (ΔH_f). Impurities lead to significant errors in Born-Haber cycles. |

| Calorimetry Apparatus | The primary experimental setup for directly measuring heat changes (e.g., enthalpy of formation, sublimation, and solution) required for Born-Haber cycles. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Used in conjunction with Knudsen effusion cells for vapor pressure measurements, crucial for determining accurate sublimation enthalpies. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Platforms like PSI4 and Gaussian are used for computational determination of bond energies and theoretical lattice energies via electronic structure methods [15]. |

| Semiempirical & Neural Network Codes | Software such as xtb (for GFNn-xTB methods) and implementations for neural network potentials (eSEN, UMA) enable high-throughput screening of bond strengths [15]. |

| Benchmark Datasets (e.g., ExpBDE54) | Curated sets of reliable experimental data serve as the essential ground truth for validating and refining the accuracy of computational methods [15]. |

Applications and Implications in Materials Science and Drug Development

The principles of lattice energy and bond strength quantification extend far beyond simple salts, providing a foundation for understanding and designing complex materials.

- Predicting Ionic Compound Stability and Properties: Lattice energy directly correlates with key physical properties. A high lattice energy generally results in high melting and boiling points, low solubility in polar solvents, and increased hardness and brittleness [14]. This understanding is critical for selecting appropriate salt forms in pharmaceutical development to optimize stability and bioavailability.

- From Atomic Bonding to Macroscopic Strength in Metals: Recent research demonstrates a direct correlation between bond strength, quantified by cohesive energy (Ecoh), and the macroscopic mechanical properties of metals and multi-principal-element alloys (MPEAs) [16]. Models have been developed that use Ecoh and atomic radius to predict grain-boundary energies, which in turn control the material's strength according to the Hall-Petch relationship [16]. This provides a physical picture linking atomic-scale bond strength to macro-scale properties for materials design.

The interplay between theoretical and experimental lattice energy, mediated by the Born-Haber cycle, remains a cornerstone of quantitative chemistry. The divergence between these values is not a failure of theory, but a successful diagnostic that reveals the nuanced reality of chemical bonding, where pure ionic character is often an idealization. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative framework is indispensable. It provides a rigorous method for validating computational models against experimental benchmarks, ensures the accurate prediction of material properties, and guides the rational selection of compounds with desired stability and performance characteristics. As computational methods advance, the synergy between high-accuracy quantum chemistry and reliable experimental thermochemical cycles will continue to deepen our understanding of bond energies and accelerate the design of novel materials and pharmaceuticals.

The chemisorption energy, representing the bond strength between an adsorbate and a material surface, serves as a fundamental determinant in numerous chemical processes ranging from heterogeneous catalysis to corrosion and nanotechnology [17]. Accurate prediction of this property enables researchers to design surfaces with optimal characteristics, thereby accelerating the development of efficient catalysts, durable materials, and novel functional interfaces. Electronic-structure-based models have emerged as indispensable tools for this purpose, providing a physical framework to interpret and predict adsorption strengths without resorting to exhaustive experimental testing. Among these, the d-band model pioneered by Hammer and Nørskov has achieved notable success, establishing the d-band center (the average energy of d-states relative to the Fermi level) as a central descriptor for trends in chemisorption strength across transition metal surfaces [17]. This model effectively correlates electronic structure features obtained before interaction with the resulting chemisorption energy, offering a powerful simplifying principle for surface science.

However, the increasing complexity of modern materials—including multi-metallic alloys, intermetallics, and high-entropy alloys—has revealed limitations in conventional d-band center approaches [17]. These shortcomings primarily arise because the d-band center alone carries no information about band dispersion, asymmetries, or distortions in the electronic structure introduced by alloying, and fails to fully account for perturbations in the surface electronic states induced by the adsorbate itself. Consequently, researchers have developed enhanced models that incorporate additional electronic factors beyond the d-band center, such as d-band width, higher moments of the d-band, and coordination effects, to achieve improved accuracy across broader ranges of material systems. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these electronic structure factors, evaluating their predictive performance, methodological requirements, and applicability for contemporary challenges in surface chemistry and catalysis research.

Theoretical Framework: From d-Band Center to Advanced Descriptors

Foundations of the d-Band Model

The conventional d-band model operates on the principle that chemisorption energy (ΔE) can be decomposed into contributions from interaction with the metal sp-electrons and the d-electrons: ΔE = ΔEsp + ΔEd [17]. The sp-electron contribution is typically large and attractive but approximately constant across transition metals, while the d-electron contribution varies systematically and primarily governs trends in adsorption strength. In this framework, the d-band center (ε_d) serves as the principal descriptor, where a higher-lying d-band center (closer to the Fermi level) generally correlates with stronger bonding. This occurs because a higher d-band center enhances coupling with adsorbate states and shifts the antibonding states to higher energies, potentially above the Fermi level, resulting in increased occupancy of bonding states and stronger adsorption [17]. The model has demonstrated remarkable success in explaining trends across pure transition metals and some simple alloys, establishing itself as a foundational concept in surface chemistry.

The physical basis for this model originates from the Newns-Anderson approach, which describes the interaction between a single adsorbate energy level and the continuum of surface electronic states [17]. In transition metals, the localized d-states with their narrow energy distribution interact with the adsorbate level to produce bonding and antibonding states, while the broad, delocalized sp-states produce a single renormalized resonance. The simplicity and intuitive nature of the d-band model have contributed to its widespread adoption, though its limitations in treating complex alloys have motivated the development of more sophisticated approaches that capture additional electronic structure features beyond the d-band center alone.

Advanced Electronic Structure Descriptors

Recent research has identified several electronic structure factors that enhance predictive capability beyond the basic d-band center approach. These advanced descriptors address specific limitations of the conventional model, particularly for multi-metallic systems:

d-Band Width and Higher Moments: The d-band width, derived from the second moment of the d-band density of states, provides information about the dispersion and coordination environment of surface atoms [18]. Incorporating this descriptor helps account for variations in local coordination geometry that significantly impact chemisorption behavior. Some advanced models also utilize the d-band skewness (third moment) and kurtosis (fourth moment) to capture asymmetries and peak shapes in the d-band density of states that influence bonding interactions [17].

d-Band Filling: The occupation of d-states plays a critical role in determining chemisorption strength, as it affects the electron transfer capabilities and the position of antibonding states relative to the Fermi level [17] [19]. Systems with high d-band filling typically exhibit weaker adsorption due to increased occupation of antibonding states, while lower d-band filling often correlates with stronger bonding.

Adsorbate-Induced Effects: Advanced models recognize that adsorbates not only perturb surface electronic states but also induce changes in the adsorption site that interact with the chemical environment [17]. This leads to a second-order response in chemisorption energy with the d-filling of neighboring atoms, explaining deviations from simple linear behavior observed in complex alloys.

Non-ab Initio Descriptors: For large-scale screening, researchers have developed descriptors that do not require density functional theory calculations, such as combining d-band width from muffin-tin orbital theory with electronegativity to account for adsorbate renormalization [18]. These enable rapid first-pass screening of materials while maintaining reasonable accuracy.

Table 1: Key Electronic Structure Descriptors in Chemisorption Models

| Descriptor | Physical Significance | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-Band Center | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | Intuitive; good for trend prediction across pure metals | Neglects band shape and width; inadequate for complex alloys |

| d-Band Width | Measure of d-band dispersion related to coordination | Accounts for local coordination environment | Requires additional calculation; interpretation less straightforward |

| d-Band Filling | Occupation of d-states | Captives electron transfer capabilities; affects antibonding occupancy | Interplays with other factors in complex ways |

| Higher Moments | Shape and asymmetry of d-band distribution | Captures nuanced features of electronic structure | Computationally intensive; complex interpretation |

| Electronegativity | Tendency to attract electrons in chemical bonds | Simple descriptor for adsorbate effects | Oversimplifies complex charge transfer processes |

Performance Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods

Accuracy Assessment Across Methodologies

The predictive accuracy of electronic structure methods varies significantly based on the complexity of the descriptors employed and the material systems under investigation. Quantitative comparisons reveal distinct performance patterns across different approaches:

Traditional d-band center models typically achieve mean absolute errors (MAEs) of approximately 0.15-0.25 eV for adsorption energies on pure transition metals, but these errors increase substantially for bimetallic and multi-component systems, sometimes exceeding 0.5 eV [17]. This degradation in performance highlights the fundamental limitations of relying solely on the d-band center for complex alloys. In contrast, advanced models incorporating multiple electronic factors demonstrate markedly improved accuracy. For instance, models employing d-band width plus electronegativity as descriptors have achieved MAEs of 0.05 eV for CO adsorption on 263 alloy systems when combined with active learning algorithms [18]. Without active learning, the accuracy decreased to 0.18 eV, underscoring the importance of sampling strategy in addition to descriptor selection.

Recent physics-based models employing first and second moments of the d-band along with d-band filling have demonstrated robust performance across diverse systems, reporting MAEs of 0.13 eV versus density functional theory reference values for O, N, CH, and Li chemisorption on bi- and tri-metallic surface and subsurface alloys [17]. This represents a significant improvement over conventional d-band center approaches while maintaining physical interpretability. The integration of machine learning methods with electronic structure descriptors has further enhanced predictive capability, with neural network (NN) and kernel ridge regression (KRR) approaches successfully mapping descriptors to adsorption energies while preserving computational efficiency compared to direct quantum calculations [18].

Application-Specific Performance Considerations

The optimal choice of electronic structure model depends critically on the specific application requirements, including material complexity, desired accuracy, and computational constraints:

For high-throughput screening of bimetallic catalysts, models combining d-band features with coordination numbers or electronegativity often provide the best balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy [18] [19]. These approaches have successfully identified promising catalyst formulations, such as Cu₃Y@Cu for electrochemical CO₂ reduction with an overpotential approximately 1 V lower than gold catalysts [18]. For fundamental studies of adsorption mechanisms on well-defined surfaces, more sophisticated approaches incorporating higher moments of the d-band may be justified despite their increased computational demands, as they provide deeper physical insight into bonding interactions [17].

In applications requiring extreme accuracy for small systems, high-level quantum chemistry methods like CCSD(T) remain the gold standard, though they are computationally prohibitive for most practical catalyst screening applications [20] [21]. For example, CCSD(T) calculations have demonstrated remarkable accuracy for bond dissociation energies in small molecules, with errors potentially below 1 kcal/mol (0.043 eV) when using appropriate basis sets and accounting for core-valence correlation effects [20]. However, such methods remain impractical for surface systems of meaningful size, necessitating the continued development and use of descriptor-based models.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for Bond Energy Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Typical MAE Range | Computational Cost | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic d-Band Center | Hammer-Nørskov model | 0.15-0.25 eV (higher for alloys) | Low | Trend analysis on pure metals; educational contexts |

| Multi-Descriptor d-Band | d-band center + width + filling | 0.05-0.15 eV | Moderate | Alloy catalyst screening; surface design |

| Machine Learning Enhanced | NN/KRR with electronic descriptors | 0.05-0.10 eV (with active learning) | Low (after training) | High-throughput screening of complex materials |

| High-Level Quantum Chemistry | CCSD(T), (RO)CBS-QB3 | <0.05 eV for small molecules | Very High | Benchmark calculations; method validation |

| Density Functional Theory | Various functionals (e.g., B3LYP, PBE, r²SCAN) | 0.03-0.20 eV (functional-dependent) | Moderate to High | Direct adsorption energy calculation; training data generation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Computational Workflows for Descriptor Evaluation

The reliable calculation of electronic structure descriptors requires carefully designed computational protocols. For surface slab models, standard approaches typically employ density functional theory with generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals such as PBE, which provide reasonable accuracy for metallic systems at manageable computational cost [19]. The d-band center is calculated as the first moment of the projected d-band density of states: εd = ∫{-∞}^{EF} ε nd(ε)dε / ∫{-∞}^{EF} nd(ε)dε, where nd(ε) represents the density of d-states at energy ε, and E_F is the Fermi energy [19]. For magnetic systems, separate d-band centers must be computed for spin-up and spin-down channels, as significant differences can dramatically influence adsorption behavior [19].

Higher moments of the d-band follow analogous definitions: the width (second moment) is calculated as Wd = [∫{-∞}^{EF} (ε-εd)² nd(ε)dε / ∫{-∞}^{EF} nd(ε)dε]^{1/2}, while the skewness (third moment) and kurtosis (fourth moment) provide information about distribution asymmetry and peak sharpness, respectively [17]. These calculations typically employ specialized codes such as VASP with post-processing tools like VASPKIT for electronic structure analysis [19]. For high-quality results, computational parameters must be carefully controlled, including using appropriate k-point meshes for Brillouin zone sampling (e.g., 8×8×1 for surface calculations), sufficient plane-wave cutoff energy (typically 400-520 eV), and proper treatment of core electrons using the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method [19].

Figure 1: Computational workflow for descriptor-based chemisorption prediction

Benchmarking and Validation Approaches

Rigorous validation of chemisorption models requires comparison against high-quality reference data, typically obtained from carefully converged DFT calculations or experimental measurements where available. Standard benchmarking protocols involve calculating adsorption energies for a diverse set of adsorbate-surface combinations and comparing predictions against reference values using statistical metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and correlation coefficients [17] [21].

For method development, established benchmark datasets like BSE49 (comprising 4,502 bond-separation energy values computed at the (RO)CBS-QB3 level) provide valuable references for assessing performance across diverse chemical systems [21]. Similarly, experimental benchmark sets such as ExpBDE54 offer gas-phase bond dissociation enthalpies for validation, though appropriate corrections must be applied to account for zero-point energy, enthalpy, and relativistic effects when comparing with computational results [15]. Active learning approaches significantly enhance validation efficiency by strategically selecting training points that maximize information gain, thereby reducing the number of expensive reference calculations required to achieve target accuracy levels [18].

When validating models for surface adsorption, it is essential to consider various potential error sources, including basis set superposition error (BSSE), which can be corrected using the counterpoise method of Boys and Bernardi [22]. For systems with potential multireference character, such as those involving bond dissociation, methods beyond single-reference DFT may be necessary, including complete active space SCF (CASSCF) or multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI) approaches [22]. These considerations ensure robust validation and prevent overestimation of model performance due to systematic computational errors.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Software Solutions for Electronic Structure Analysis

The computational study of electronic structure factors in chemisorption relies on specialized software tools spanning from ab initio calculation to descriptor analysis and machine learning:

VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package): A widely used package for DFT calculations employing the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method [19]. Essential for calculating surface electronic structures, optimizing adsorption geometries, and computing d-band properties using GGA functionals like PBE.

Gaussian: A comprehensive quantum chemistry package supporting various methods from Hartree-Fock to coupled cluster theory and density functional theory [21]. Particularly valuable for benchmarking studies on cluster models and calculating accurate reference data using composite methods like CBS-QB3.

MOLPRO: A specialized quantum chemistry software with strengths in high-accuracy multireference methods, including CASSCF, MRCI, and coupled cluster techniques [22]. Useful for studying systems with strong electron correlation or multireference character where standard DFT fails.

VASPKIT: A post-processing toolkit for VASP that automates the calculation of electronic structure descriptors, including d-band centers, widths, and higher moments [19]. Streamlines the extraction of chemisorption-relevant properties from DFT calculations.

xtb: A semiempirical quantum chemistry program providing fast calculations using the GFNn-xTB methods [15]. Enables rapid geometry optimizations and preliminary screening studies at a fraction of the cost of DFT.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Chemisorption Studies

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | DFT Calculations | PAW method; surface modeling; DOS analysis | First-principles surface and adsorption studies |

| Gaussian | Quantum Chemistry | Composite methods; molecular calculations | Benchmarking; cluster model studies |

| psi4 | Quantum Chemistry | Efficient DFT implementation; various wavefunction methods | Method development; testing new functionals |

| VASPKIT | Post-processing | Automated descriptor calculation; data extraction | Streamlining analysis of VASP results |

| xtb | Semiempirical Methods | Fast geometry optimization; large systems | Preliminary screening; conformational analysis |

High-quality reference data is essential for developing and validating new chemisorption models. Several curated datasets serve as valuable resources for the research community:

BSE49 Dataset: A comprehensive collection of 4,502 bond-separation energies for 49 unique bond types calculated at the (RO)CBS-QB3 level of theory [21]. Provides non-relativistic ground-state energy differences without zero-point corrections, ideal for testing electronic structure methods.

ExpBDE54: A curated set of experimental homolytic bond-dissociation enthalpies for 54 small molecules, focusing on carbon-hydrogen and carbon-halogen bonds most relevant to organic and medicinal chemistry [15]. Useful for validating methods against experimental measurements.

Catalyst Datasets: Specialized collections of adsorption energies on various metal and alloy surfaces, typically computed using DFT [18] [17]. Enable direct testing of chemisorption models for catalytic applications.

These resources facilitate standardized comparisons between different electronic structure methods and ensure that performance claims are based on consistent, reproducible benchmarks. When using these datasets, researchers should adhere to the intended applications—for instance, BSE49 is designed for testing electronic energy calculations rather than direct comparison with experimental bond dissociation enthalpies, which require additional corrections for zero-point energy and thermal effects [21].

Electronic structure factors governing chemisorption have evolved significantly beyond the conventional d-band center model, with advanced descriptors incorporating d-band width, filling, and higher moments demonstrating markedly improved accuracy for complex material systems. The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals a clear trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance, with multi-descriptor approaches achieving mean absolute errors as low as 0.05-0.13 eV for diverse adsorbates on alloy surfaces [18] [17]. These developments address critical limitations of traditional models while maintaining physical interpretability—an essential consideration for guiding materials design.

Future advancements in this field will likely emerge from several promising directions. The integration of machine learning with electronic structure descriptors represents a particularly powerful approach, combining physical insight with data-driven pattern recognition to navigate complex materials spaces [18] [21]. Additionally, increasing attention to adsorbate-induced surface perturbations and their interaction with the local chemical environment will further refine our understanding of bonding interactions in complex systems [17]. The development of efficient non-ab initio descriptors will continue to enable high-throughput screening, while benchmark datasets and active learning strategies will optimize the use of computational resources for model training and validation [18] [21] [15].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these methodological advances translate to increasingly reliable tools for predicting surface interactions and designing optimized materials. As electronic structure methods continue to evolve, their capacity to guide experimental efforts will further strengthen, accelerating the discovery of next-generation catalysts, functional materials, and therapeutic agents through computationally driven design.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, accurately predicting the strength of chemical bonds is not an academic exercise—it is a fundamental prerequisite for understanding stability, reactivity, and metabolic fate. Experimental gas-phase measurements provide the indispensable foundation for this understanding, serving as the highest standard for benchmarking the computational methods used in molecular design [23]. By isolating molecules from the complicating effects of solvents and counter-ions, these measurements yield precise dissociation energies that reflect the true, unperturbed intermolecular interaction strengths [23].

This guide objectively compares key experimental benchmarks and the electronic structure methods they validate. It provides researchers with the data needed to select the most appropriate computational workflow for predicting bond energies, a critical task in applications ranging from predicting sites of drug metabolism to designing new catalysts.

Key Experimental Benchmark Datasets

Several high-quality datasets serve as standardized references for validating computational chemistry methods. The table below summarizes two prominent benchmarks for bond energy data.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Experimental and Computational Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset Name | ExpBDE54 [15] | BSE49 [21] |

|---|---|---|

| Data Origin | Experimental gas-phase measurements | High-level theoretical computations ((RO)CBS-QB3) |

| Data Content | 54 experimental homolytic Bond-Dissociation Enthalpies (BDEs) | 4,502 Bond Separation Energies (BSEs) for 49 unique bond types |

| Primary Utility | External validation of computational methods | Training and parametrization of lower-cost methods |

| Key Features | Covers C-H and C-halogen bonds relevant to organic & medicinal chemistry | Extensive and diverse, includes "Existing" and "Hypothetical" molecules |

| Direct Experimental Comparison | Yes, provides benchmark BDE values | No, values are not directly comparable to experimental BDEs |

The ExpBDE54 dataset is a "slim" benchmark curated from experimental gas-phase studies, ideal for quickly testing a method's performance on chemically relevant bonds [15]. In contrast, the BSE49 dataset is a large, computationally derived resource ideal for training machine learning potentials or parameterizing semi-empirical methods, though its energies lack zero-point and thermal corrections [21].

Benchmarking Electronic Structure Methods

The true value of experimental benchmarks lies in their ability to evaluate the accuracy and efficiency of computational workflows. A 2025 study leveraged the ExpBDE54 dataset to map the Pareto frontier of bond-dissociation-enthalpy-prediction methods, balancing speed against accuracy [15].

Table 2: Performance of Selected Computational Methods on the ExpBDE54 Benchmark (Root-Mean-Square Error in kcal·mol⁻¹) [15]

| Methodology Class | Specific Method | Reported RMSE | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potential | OMol25's eSEN Conserving Small | 3.6 | Medium-sized systems where accuracy is prioritized [15] |

| Semiempirical (GFN2-xTB optimized) | g-xTB//GFN2-xTB | 4.7 | CPU-based calculations where speed is critical [15] |

| Density-Functional Theory (DFT) | r2SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD | 3.6 | High-accuracy reference standard [15] |

| DFT with Semiempirical Optimization | r2SCAN-3c//GFN2-xTB | Best speed/accuracy tradeoff for a QM-based method [15] |

The benchmarking reveals that suitably corrected semiempirical and machine-learning approaches can rival the accuracy of more expensive DFT methods at a fraction of the computational cost. For instance, g-xTB//GFN2-xTB offers a rapid solution on CPU hardware, while OMol25's eSEN Conserving Small neural network potential achieves top-tier accuracy for medium-sized systems [15]. The composite DFT method r2SCAN-3c provides an excellent balance of speed and accuracy, especially when paired with a GFN2-xTB geometry optimization [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The SEP-R2PI Method for Intermolecular Dissociation Energies

A premier experimental technique for obtaining gas-phase ground-state dissociation energies (D₀(S₀)) of cold, isolated bimolecular complexes is the SEP-R2PI (Stimulated Emission Pumping-Resonant Two-Photon Ionization) method [23]. This laser-based approach allows for the precise measurement of the dissociation energy for noncovalent complexes (e.g., M⋅S, where M is an aromatic molecule and S is a solvent atom/molecule) with bracketing accuracies of ≤1.0 kJ/mol [23].

The workflow involves a triply resonant process that deposits energy directly into the ground-state vibrational modes of the complex to induce dissociation.

Diagram 1: SEP-R2PI Method Workflow. This laser technique precisely measures gas-phase dissociation energies.

This protocol has been successfully applied to characterize 55 different M⋅S complexes, creating a large experimental database for understanding noncovalent interactions like hydrogen bonding and London dispersion [23].

Workflow for Computational Benchmarking

To validate a computational method against a benchmark like ExpBDE54, a standardized workflow is followed to calculate electronic bond-dissociation energies (eBDEs) and compare them to experimental enthalpies.

Diagram 2: Computational BDE Benchmarking Workflow. This process calculates theoretical bond dissociation energies for comparison with experimental benchmarks.

The linear regression correction in the final step is crucial, as it accounts for systematic errors and missing contributions like zero-point energy and enthalpic effects, enabling a fair comparison between computed electronic energies and experimental enthalpies [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details key resources and methodologies essential for work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SEP-R2PI Laser Spectroscopy [23] | Experimental Apparatus | Provides gold-standard gas-phase intermolecular dissociation energies (D₀) for benchmark complexes. |

| ExpBDE54 Dataset [15] [24] | Experimental Benchmark Data | Serves as a "slim" external benchmark for validating BDE-prediction methods on 54 small molecules. |

| BSE49 Dataset [21] | Computational Reference Data | Provides 4,502 high-quality theoretical Bond Separation Energies for method training and development. |

| GFN2-xTB [15] | Semiempirical Quantum Method | Used for fast geometry optimizations of parent molecules and radical fragments in computational workflows. |

| r2SCAN-3c [15] | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A "Swiss-army knife" DFT method offering a strong balance of accuracy and computational speed for BDE prediction. |

| g-xTB [15] | Semiempirical Quantum Method | A low-cost method suitable for rapid BDE calculations, especially when on CPU and speed is a premium. |

Gas-phase experimental measurements provide the non-negotiable standard for accuracy in bond energy research. Datasets like ExpBDE54 offer a critical foundation for objectively comparing and improving computational methods, from fast semiempirical approaches to high-level DFT and neural network potentials [15]. For researchers in drug development, leveraging these benchmarks enables more reliable predictions of metabolic stability and reactivity, ultimately informing the design of safer and more effective therapeutics. As computational power grows and methods evolve, the role of precise, gas-phase experimental data will only become more vital in pushing the frontiers of accuracy in electronic structure theory.

Computational Toolkit: A Practical Guide to DFT, Semiempirical, and Machine Learning Methods

Within computational chemistry, predicting bond dissociation energies (BDEs) with high accuracy is fundamental to understanding reaction mechanisms, catalyst design, and predicting metabolic sites in drug development. While highly accurate wavefunction methods exist, their computational cost often precludes their use for large, chemically relevant systems. Consequently, Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KS-DFT) remains the workhorse for such applications, with its accuracy critically dependent on the chosen exchange-correlation functional. This guide objectively compares the performance of three popular density functional approximations—r2SCAN-D4, ωB97M-D3BJ, and B3LYP-D4—in the context of bond energy calculations, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to make an informed selection.

Theoretical Background and Functional Profiles

The selected functionals represent different rungs on Perdew's "Jacob's Ladder" of DFT approximations, each with a distinct approach to incorporating physical constraints and empirical data.

r2SCAN-D4: A meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation (meta-GGA) that is "regularized" to restore the formal constraints of its predecessor, SCAN, while achieving superior numerical stability. It is typically combined with the modern D4 dispersion correction [25] [26]. Its key strength is its non-empirical design, offering high transferability without fitting parameters, and it approaches the accuracy of hybrid functionals while retaining the speed of a semi-local functional [25].

ωB97M-D3BJ: A range-separated hybrid meta-GGA, meaning it uses exact Hartree-Fock exchange at long interelectronic ranges and a meta-GGA at short ranges. It is routinely paired with the D3(BJ) empirical dispersion correction. This functional is known for its high performance across a wide range of properties, including thermochemistry and non-covalent interactions [27].

B3LYP-D4: A global hybrid GGA, one of the most widely used functionals in computational chemistry. It mixes a fixed percentage of exact exchange with GGA exchange and correlation. The addition of the latest D4 dispersion correction modernizes this classic functional, improving its description of non-covalent interactions [28].

Performance Benchmarking on Bond Dissociation Energies

The accuracy of these functionals for bond energy predictions is quantitatively assessed using the ExpBDE54 dataset, a compilation of 54 experimental homolytic bond-dissociation enthalpies for carbon-hydrogen and carbon-halogen bonds [15].

Table 1: Performance of DFT Functionals on the ExpBDE54 Benchmark Set (RMSE in kcal/mol)

| Functional | Basis Set | RMSE (ExpBDE54) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| r2SCAN-D4 | def2-TZVPPD | 3.6 | Benchmark |

| ωB97M-D3BJ | def2-TZVPPD | 3.7 | Comparable to r2SCAN-D4 |

| B3LYP-D4 | def2-TZVPPD | 4.1 | ~2x Faster than r2SCAN-D4 |

| r2SCAN-D4 | vDZP | ~5.1 | ~2x Faster than def2-TZVPPD |

| ωB97M-D3BJ | vDZP | ~4.8 (Most Accurate with vDZP) | ~2x Faster than def2-TZVPPD |

The data reveals several key trends [15]:

- r2SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD is the most accurate combination overall, achieving an RMSE of 3.6 kcal/mol.

- Moving to the more efficient vDZP basis set, ωB97M-D3BJ becomes the most accurate functional, demonstrating its robustness with smaller basis sets.

- B3LYP-D4 offers a attractive balance, providing respectable accuracy (4.1 kcal/mol) with a significant speed advantage, calculated to be approximately twice as fast as the r2SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD workflow.

Performance Across Diverse Chemical Properties

Beyond BDEs, the overall utility of a functional depends on its performance across various chemical properties. The extensive GMTKN55 database, which encompasses main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and non-covalent interactions, provides a broad view of functional reliability.

Table 2: Generalized Performance on the GMTKN55 Database (WTMAD2 in kcal/mol)

| Functional | Overall WTMAD2 (GMTKN55) | Barrier Heights | Non-Covalent Interactions | Transition Metal Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r2SCAN-D4 | 7.5 [25] | Good | Good | Excellent [29] [30] |

| ωB97M-D3BJ | Not Explicitly Reported | Excellent [27] | Excellent [31] [27] | Good |

| B3LYP-D4 | 6.4 (with vDZP) [28] | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate [29] |

Key insights from this broader benchmarking include [29] [30] [31]:

- r2SCAN-D4 shows exceptional versatility, particularly in transition metal chemistry. It is a top performer for the geometry of spin-coupled iron-sulfur clusters like the nitrogenase FeMoco cluster, with errors for metal-metal distances of just 0.8% [30] [25].

- ωB97M-D3BJ excels in kinetics and non-covalent interactions. It is a top-tier range-separated hybrid for calculating barrier heights and reaction energies and performs exceptionally well for hydrogen-bonding energies in supramolecular complexes [31] [27].

- B3LYP-D4, while less specialized, delivers solid all-around performance, especially when paired with an efficient basis set like vDZP [28].

Detailed Computational Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines the standard computational protocols used in the benchmark studies cited herein.

Bond Dissociation Enthalpy (BDE) Calculation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for computing accurate BDEs, adapted from benchmark studies [15].

Key Steps in the BDE Calculation Protocol [15]:

- Initial Geometry Optimization: Molecular geometries are generated from SMILES strings and optimized. For efficiency, the semi-empirical GFN2-xTB method is often used, though DFT optimization can also be employed.

- Single-Point Energy on Intact Molecule: A high-level DFT single-point energy calculation is performed on the optimized geometry.

- Bond Cleavage and Fragment Optimization: The target bond is broken homolytically, generating two doublet radical fragments. These fragments are then geometry-optimized.

- Single-Point Energy on Fragments: High-level DFT single-point energy calculations are performed on the optimized fragments.

- Electronic BDE (eBDE) Calculation: The eBDE is computed as the energy difference between the fragments and the parent molecule.

- Empirical Correction: A linear regression correction is applied to the eBDEs to account for the lack of zero-point energy, enthalpic, and relativistic effects, bringing the values into agreement with experimental BDEs.

General DFT Single-Point Energy Protocol

The following settings represent a robust standard for obtaining accurate DFT energies, as used in modern benchmarks [28] [15] [31].

- Software: Calculations are typically performed with quantum chemistry packages like Psi4 or ORCA.

- Integration Grid: A dense integration grid is crucial for meta-GGA and hybrid functionals. Common choices include a (99,590) grid or the

DEFGRID3setting in ORCA [28] [26]. - Dispersion Correction: Empirical dispersion corrections (D3(BJ) or D4) must be included, as they are essential for non-covalent interactions and accurate thermochemistry [31] [25].

- Basis Set Selection:

- SCF Convergence: Techniques like a level shift (e.g., 0.10 Hartree) and tight integral tolerances (e.g., 10⁻¹⁴) are used to ensure robust self-consistent field convergence [28].

Table 3: Key Software, Basis Sets, and Benchmarks for DFT Studies

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Psi4/ORCA | Software | Open-source quantum chemistry packages for running DFT, HF, and correlated calculations. |

| def2-TZVPPD | Basis Set | Triple-zeta quality basis with diffuse functions; used for highly accurate single-point energies. |

| vDZP | Basis Set | Pareto-efficient double-zeta basis for rapid calculations with low basis-set error [28]. |

| GMTKN55 | Benchmark | Database of 55 main-group chemical problems for general functional benchmarking [25] [26]. |

| ExpBDE54 | Benchmark | A "slim" benchmark of 54 experimental BDEs for validating bond-strength prediction methods [15]. |

| GFN2-xTB | Software | Semi-empirical method for fast geometry optimizations, often used as a precursor to DFT single-points [15]. |

| D4/D3(BJ) | Correction | Empirical dispersion corrections that must be added to functionals for physical interaction energies. |

The experimental data clearly indicates that there is no single "best" functional for all scenarios; the optimal choice depends on the specific chemical problem, system size, and required accuracy.

- For Maximum BDE Accuracy: The r2SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD combination is the top performer, making it the ideal choice for definitive studies on bond strengths where computational cost is secondary to accuracy.

- For a Balance of Speed and Accuracy: ωB97M-D3BJ/vDZP provides an excellent compromise, being the most accurate functional with the efficient vDZP basis set for BDEs. It is also the preferred choice for reactions involving significant non-covalent interactions or complex barrier heights.

- For Large Systems and Routine Screening: B3LYP-D4/vDZP offers a reliable and computationally efficient option for screening large libraries of compounds, such as in drug discovery for predicting metabolic sites, while still providing good quantitative accuracy.

For systems containing transition metals or complex spin-coupled clusters like iron-sulfur cofactors, r2SCAN-D4 and its hybrid variants are particularly recommended due to their superior description of metal-ligand covalency and geometric structure [29] [30]. Researchers are encouraged to use the provided protocols and benchmarks to validate these functionals for their specific applications.

In the field of computational chemistry, the demand for efficient electronic structure methods that can balance speed with accuracy is a central research focus, particularly for applications in high-throughput screening and bond energies research. Semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods, which are based on the Hartree-Fock formalism but incorporate approximations and empirical parameters, have emerged as crucial tools for treating large molecules where more accurate ab initio methods become prohibitively expensive [32]. These methods obtain some parameters from empirical data, which allows for a partial inclusion of electron correlation effects [32].

The GFN-xTB (Geometry, Frequency, Noncovalent interactions, eXtended Tight Binding) family of methods, developed by Grimme's group, represents a significant advancement in this domain. These methods are designed to provide a compelling balance between computational efficiency and accuracy across a broad spectrum of molecular properties [33]. This guide provides an objective comparison between two key members of this family—the established GFN2-xTB and the newer general-purpose g-xTB—evaluating their performance specifically for high-throughput screening applications within the context of bond energy research.

The GFN-xTB Framework

GFN-xTB methods are semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods that utilize a tight-binding approximation to density functional theory (DFT) [33]. They belong to a broader category of semiempirical methods that also includes the DFTB (Density Functional Tight-Binding) family [32]. The GFN framework encompasses several levels of theory, including GFN1-xTB, GFN2-xTB, GFN0-xTB, and the force-field method GFN-FF [33]. These methods have rapidly gained traction for efficient computational investigations across diverse chemical systems, from large transition-metal complexes to complex biomolecular assemblies [33].

GFN2-xTB: Capabilities and Limitations

GFN2-xTB has established itself as a valuable tool in computational chemistry, occupying "an odd niche" as noted in the literature [34]. It is described as "a parameterized tight-binding method that produces molecular geometries and noncovalent interactions fast enough for large-scale conformer searches, implicit solvent calculations, or molecular dynamics runs where DFT would be prohibitive" [34]. However, its limitations are well-documented: "reaction barriers come out too low, orbital gaps are compressed, and transition-metal complexes can sometimes distort into unphysical geometries" [34]. Despite these shortcomings, its speed and black-box nature maintain its popularity in many applications.

g-xTB: A General Replacement

The new g-xTB method from Grimme's group is explicitly intended as a general replacement for the GFN-xTB family [34]. The "g" stands for "general," and the development addresses three structural problems identified in GFN-xTB:

- No Hartree-Fock exchange: GFN2-xTB emulates a GGA functional, which works for geometries but is systematically weak for thermochemistry and barrier heights [34].

- Minimal basis sets: The traditional STO-nG-like bases don't adapt to molecular environments and lack polarization functions on key elements [34].

- Narrow training scope: Parameterization focused on a few property types rather than broad coverage of chemical space [34].

g-xTB maintains the tight-binding framework but introduces significant improvements including a charge-dependent, polarization-capable basis; an extended Hamiltonian with range-separated approximate Fock exchange; higher-order charge terms in the density-fluctuation expansion; atomic correction potentials; and a charge-dependent repulsion term [34].

Performance Comparison

The performance of electronic structure methods is typically evaluated using standardized benchmark sets like GMTKN55, which contains approximately 32,000 relative energies covering thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interactions [34]. On this benchmark, g-xTB demonstrates a weighted total mean absolute deviation (WTMAD-2) of 9.3 kcal/mol, roughly half that of GFN2-xTB and comparable to some "cheap" DFT methods [34]. This represents a substantial advancement in accuracy while maintaining the speed advantages of semiempirical methods.

Table 1: Overall Performance Comparison on GMTKN55 Benchmark

| Method | WTMAD-2 (kcal/mol) | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | ~18.6 | Baseline |

| g-xTB | 9.3 | ~50% improvement |

Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) Prediction

For bond energy research—a critical aspect of the broader thesis on the accuracy of electronic structure methods—g-xTB shows remarkable improvement. On a recent set of experimental C-H and C-X bond dissociation energy benchmarks, g-xTB achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 3.96 kcal/mol after linear correction, far superior to GFN2-xTB's MAE of 7.88 kcal/mol [34]. This level of accuracy makes g-xTB comparable to top DFT methods or neural network potentials for this specific property [34]. The g-xTB//GFN2-xTB approach (single-point g-xTB calculations on GFN2-xTB geometries) emerged as one of the "two Pareto-dominant methods" and is recommended for production usage when efficiency is paramount [34].

Table 2: Bond Dissociation Energy Prediction Accuracy

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | 7.88 | Significant scatter in predictions [34] |

| g-xTB | 3.96 | Strong correlation to experimental BDE [34] |

| g-xTB//GFN2-xTB | ~3.96 | Recommended for production use [34] |

Reaction Barrier Prediction

The inclusion of range-separated approximate Fock exchange in g-xTB directly addresses one of GFN2-xTB's key weaknesses: the systematic underestimation of reaction barriers. Literature confirms that "g-xTB is much better at predicting barrier heights" owing to this methodological improvement [34]. This advancement is particularly valuable for reaction mechanism studies and catalytic cycle analysis in high-throughput screening applications.

Geometrical and Electronic Properties

For geometry optimization of small organic semiconductor molecules, GFN2-xTB demonstrates high structural fidelity according to benchmarking studies [33]. However, g-xTB shows further improvements, particularly for transition-metal complexes, providing "more reliable and accurate geometries" [34]. For electronic properties, g-xTB "fixes the HOMO-LUMO gap issues exhibited by previous xTB methods and outperforms r2SCAN- or B3LYP-based methods at this task," a testament to the importance of range separation in the method [34].

Computational Efficiency

Computational efficiency is paramount for high-throughput screening applications. GFN2-xTB is recognized for its speed, enabling applications like conformer searches for transition-metal complexes through tools like CREST (Conformer-Rotamer Ensemble Sampling Tool) [35]. g-xTB maintains this practical advantage, being "only a little slower than GFN2-xTB (30% or less), making it essentially a drop-in replacement for any routine usage" [34]. It's important to note that the current release of g-xTB lacks analytical gradients, making geometry optimizations and frequency calculations significantly slower than GFN2-xTB [34].

Table 3: Computational Efficiency Comparison

| Method | Speed Relative to DFT | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | Orders of magnitude faster [34] | Fast geometry optimizations [35] |

| g-xTB | Similar to GFN2-xTB (≤30% slower) [34] | Lacks analytical gradients (slower optimizations) [34] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

High-Throughput Conformer Screening for Transition-Metal Complexes

The protocol below is adapted from studies analyzing Rh-based catalysts featuring bisphosphine ligands, which are widely employed in hydrogenation reactions [35]:

- Initial Conformer Generation: Perform conformer exploration using CREST (Conformer-Rotamer Ensemble Sampling Tool) with the GFN2-xTB//GFN-FF hybrid potential. This leverages the speed of GFN2-xTB for initial sampling [35].

- Conformer Filtering: Apply DBSCAN clustering using RMSD and energy parameters to eliminate redundancies while preserving key configurations. Studies show energy-based filtering is ineffective, while RMSD-based filtering improves selection [35].

- Geometry Refinement: Refine the filtered conformer ensembles via DFT geometry optimization using Gaussian 16 at the PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-SVPP level of theory [35].

- Frequency Analysis: Confirm the nature of each stationary point via frequency analysis and compute thermochemical parameters at 298.15 K and 1 atm [35].

- Final Energy Evaluation: For production-level bond energies, perform single-point g-xTB calculations on the optimized GFN2-xTB or DFT geometries to leverage g-xTB's superior accuracy for bond dissociation energies [34].

Diagram 1: High-Throughput Conformer Screening Workflow

Protein-Ligand Interaction Energy Screening

For large systems beyond conventional DFT capabilities, such as protein-ligand interactions, the following protocol is recommended:

- System Preparation: Prepare protein and ligand structures, ensuring proper protonation states.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize ligand geometry using GFN2-xTB (or g-xTB if analytical gradients become available).

- Interaction Energy Calculation: Perform single-point g-xTB calculations on the optimized structures to determine interaction energies. Benchmark results on the PLA15 dataset show g-xTB "outperforms other low-cost methods, including state-of-the-art neural network potentials" [34].

- Validation: For critical hits, validate with higher-level DFT calculations when computationally feasible.

Essential Computational Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Semi-Empirical Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| CREST | Conformer-Rotamer Ensemble Sampling Tool for automated conformer search [35] | Uses GFN2-xTB//GFN-FF potential; overestimates ligand flexibility but efficient for initial sampling [35] |

| xTB Program | Main package for GFN-xTB calculations (GFN2-xTB and g-xTB) [35] | Current g-xTB release lacks analytical gradients [34] |

| GMTKN55 Database | Benchmark set with ~32,000 relative energies for method validation [34] | Contains thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interaction datasets [34] |

| DBSCAN Clustering | Density-based clustering algorithm for conformer filtering [35] | More effective than energy-based or PCA-based filtering; eliminates redundancies [35] |

| MORFEUS Python Package | Preprocessing and analysis of CREST output ensembles [35] | Facilitates filtering and analysis of conformer ensembles [35] |

The comparative analysis of GFN2-xTB and g-xTB reveals a clear trajectory of improvement in semiempirical quantum chemistry methods. While GFN2-xTB remains a valuable tool for rapid geometry optimization and initial conformer sampling—particularly when integrated into workflows like CREST—g-xTB represents a significant advancement in accuracy for key properties like bond dissociation energies, reaction barriers, and electronic properties.

For high-throughput screening applications in bond energy research, the evidence supports the following recommendations:

- For maximum throughput in geometry optimization and conformer sampling, GFN2-xTB remains the preferred choice.

- For accurate bond energy predictions and reaction barrier assessments, g-xTB single-point calculations on GFN2-xTB geometries provide an optimal balance of efficiency and accuracy.

- For protein-ligand interaction screening and other applications involving large systems, g-xTB offers superior performance compared to other low-cost methods.

The integration of these methods into computational screening pipelines demonstrates how semiempirical quantum chemistry continues to evolve, providing researchers with increasingly powerful tools for accelerating drug discovery and materials design while maintaining computational feasibility.

The accurate prediction of molecular properties, including bond dissociation energies (BDEs), is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, with profound implications for drug design, materials science, and energy storage research. The reliability of these predictions hinges on a foundational two-step workflow: geometry optimization to locate stable molecular structures on the potential energy surface, followed by single-point energy (SPE) calculations on these optimized geometries to compute highly accurate energies [36] [37]. This sequence balances computational cost with accuracy, as performing high-level theory calculations directly during geometry optimization is often prohibitively expensive for all but the smallest systems. The choice of methods for each step represents a series of trade-offs, creating a complex landscape that researchers must navigate. This guide provides an objective comparison of prevalent electronic structure methods, supported by experimental data, to inform best practices within the broader context of research on the accuracy of methods for calculating bond energies.

Method Comparison: Accuracy vs. Computational Cost

A hierarchical approach is widely recommended, where a lower-level (and faster) method is used for geometry optimization, and a higher-level (more accurate) method is used for the final single-point energy calculation [36] [37]. The following tables summarize the performance of various methods based on benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Geometry Optimization Methods

| Method Class | Specific Methods | Typical Heavy-Atom RMSD (Å) vs. DFT | Relative Speed | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-empirical (GFN family) | GFN1-xTB, GFN2-xTB [33] | ~0.1 - 0.3 (for organic semiconductors) | 10⁴ - 10⁵ | High-throughput screening of organic molecules; pre-optimization [33]. |

| Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) | DFTB [36] | Similar to SEQM | ~10⁴ | Large systems where semi-empirical methods are insufficient. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | PBE, B3LYP, r²SCAN-3c [37] [38] | Benchmark (0.0) | 1 - 100 (depends on functional/basis set) | Final, high-accuracy optimization; systems < 100 atoms [37]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | AIMNet2, OMol25 eSEN [39] | N/A (Data not provided in search results) | Varies (highly dependent on model and optimizer) | Promising as DFT replacements; performance depends heavily on optimizer choice [39]. |

Table 2: Performance of DFT Functionals for Single-Point Energy Calculations (for predicting redox potentials of quinones)

| DFT Functional | Level of Theory | RMSE (V) | R² | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE [36] | OPT(gas) + SPE(SOL) | 0.072 | 0.954 | Good balance of speed and accuracy for large-scale screening. |

| PBE [36] | OPT(gas) + SPE(SOL) | 0.051 | 0.977 | With implicit solvation, accuracy improves significantly. |

| B3LYP [36] | OPT(gas) + SPE(SOL) | ~0.055 | ~0.970 (estimated from graph) | Widely used; requires dispersion corrections for modern use [37]. |

| M08-HX [36] | OPT(gas) + SPE(SOL) | ~0.055 | ~0.970 (estimated from graph) | High-accuracy meta-GGA hybrid functional. |

| PBE0-D3 [36] | OPT(gas) + SPE(SOL) | ~0.050 (lowest error) | High | One of the most accurate functionals tested for redox potentials. |

Table 3: Optimizer Performance with Neural Network Potentials (Success rate for 25 drug-like molecules)

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB (Control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 22 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 24 |

| ASE/FIRE | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Sella (internal) | 20 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 25 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 25 |

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies for Key Workflows

A Standard Protocol for High-Throughput Screening

A systematic workflow for the discovery of quinone-based electroactive compounds demonstrates a robust hierarchical protocol [36].

- Initial Structure Generation: The molecular structure begins as a SMILES string, which is converted to a 3D geometry.

- Geometry Optimization: The 3D structure is optimized using a force field (e.g., OPLS3e) or a fast semi-empirical method (e.g., GFN-xTB) to locate a reasonable low-energy conformation.

- Higher-Level Optimization (Optional): The geometry may be refined further using a more accurate method, such as DFT. Notably, the study found that optimizing geometries in the gas phase, rather than with an implicit solvation model, was sufficient and computationally cheaper [36].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: The key energetic properties are calculated by performing a single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry using a higher-level DFT functional (e.g., PBE0-D3) and including an implicit solvation model (e.g., Poisson-Boltzmann) to account for solvent effects.

- Property Prediction: The reaction energy (ΔEᵣₓₙ) computed from the SPE is then calibrated against experimental data (e.g., redox potentials) to validate the protocol.

Achieving Chemical Accuracy for Bond Dissociation Energies (BDEs)