Benchmarking Machine Learning Potentials Against Ab Initio Methods: A Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) against high-fidelity ab initio methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Benchmarking Machine Learning Potentials Against Ab Initio Methods: A Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) against high-fidelity ab initio methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT). It covers the foundational principles of MLIPs, explores current methodological advances and their applications in biomolecular simulation, addresses key challenges in model robustness and data generation, and establishes a framework for rigorous validation. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively leverage MLIPs for accelerating drug discovery, from target identification to lead optimization, while understanding the critical trade-offs between computational speed and quantum-mechanical accuracy.

Bridging the Gap: How MLIPs Achieve Quantum Accuracy at Molecular Dynamics Scale

Computational quantum chemistry is indispensable for modern scientific discovery, enabling researchers to predict molecular properties, simulate chemical reactions, and accelerate drug development—all without traditional wet-lab experiments. At the heart of these simulations lie ab initio quantum chemistry methods, computational techniques based on quantum mechanics that aim to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation using only physical constants and the positions and number of electrons in the system as input [1]. The term "ab initio" means "from first principles" or "from the beginning," reflecting that these methods avoid empirical parameters or approximations in favor of fundamental physical laws [1]. While these methods provide the gold standard for accuracy in predicting chemical properties, they share a fundamental limitation: computational costs that scale prohibitively with system size, typically following a polynomial scaling of at least O(N³), where N represents a measure of the system size such as the number of electrons or basis functions [1].

This scaling relationship presents a critical bottleneck for research applications. As molecular systems grow in complexity—from simple organic molecules to biologically relevant drug targets—the computational resources required for ab initio calculations increase dramatically. For example, a calculation that takes one hour for a small molecule might require days or weeks for a moderately sized protein [2]. This scalability challenge has forced researchers to make difficult trade-offs between accuracy and feasibility, particularly in fields like drug discovery where rapid iteration is essential. The situation is particularly problematic for molecular dynamics simulations, where thousands of consecutive energy and force calculations are needed to model atomic movements over time [3]. This fundamental limitation has stimulated the search for alternative approaches that can achieve near-ab initio accuracy without the crippling computational overhead.

Quantifying the Computational Scaling of Electronic Structure Methods

The computational scaling of quantum chemistry methods is not monolithic; different theoretical approaches carry distinct computational burdens. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting appropriate methods for specific research applications. The following table systematically compares the scaling relationships of major ab initio methods:

Table 1: Computational Scaling of Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | O(N⁴) [nominally], ~O(N³) [practical] [1] | Mean-field approximation; variational; tends to Hartree-Fock limit with basis set increase |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Similar to HF (larger proportionality) [1] | Models electron density rather than wavefunction; hybrid functionals increase cost |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2) | O(N⁵) [1] | Includes electron correlation; post-Hartree-Fock method |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP4) | O(N⁷) [1] | Higher-order correlation treatment |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD) | O(N⁶) [1] | High accuracy for single-reference systems |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | O(N⁷) [1] | "Gold standard" for chemical accuracy; non-iterative step |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | ~O(N) [after training] [3] | Near-DFT accuracy; trained on ab initio data; enables large-scale simulations |

These scaling relationships translate directly to practical limitations. For instance, doubling the system size in an MP2 calculation would increase the computational time by a factor of 32 (2⁵), while the same change for a CCSD(T) calculation would increase time by a factor of 128 (2⁷) [1]. This explains why high-accuracy coupled cluster methods are typically restricted to small molecules, while less expensive methods like DFT are applied to larger systems, despite potential accuracy compromises.

The impact of these scaling relationships becomes evident when examining specific research scenarios. A quantum chemistry calculation that might take merely seconds for a diatomic molecule could require days for a moderate-sized organic molecule, and become essentially impossible for large biomolecules or complex materials using conventional computational resources [2]. This scalability challenge has driven the development of linear scaling approaches ("L-" methods) and density fitting schemes ("df-" methods) that reduce the prefactor and effective scaling of these calculations, though the fundamental polynomial scaling relationship remains [1].

Machine Learning Potentials as Accelerated Alternatives

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as powerful surrogate models that aim to achieve ab initio-level accuracy while dramatically reducing computational cost. These models learn the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energy from quantum mechanical reference data, then use this learned relationship to predict energies and forces for new configurations [3]. Under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the potential energy surface (PES) of a molecular system is governed by the spatial arrangement and types of atomic nuclei. MLIPs provide an efficient alternative to direct quantum mechanical approaches by learning from ab initio-generated data to predict the total energy based on atomic coordinates and atomic numbers [3].

The architecture of these models typically expresses the total energy as a sum of atom-wise contributions, ( E = \sumi Ei ), where each ( Ei ) is inferred from the final embedding of atom ( i ). To ensure energy conservation, atomic forces are calculated as the negative gradient of the predicted energy with respect to the atomic positions, ( \bm{f}i = -\nabla{\bm{x}i}E ) [3]. This formulation allows MLIPs to achieve near-ab initio accuracy while reducing computational cost by orders of magnitude, making them widely applicable in atomistic simulations for molecular dynamics and materials modeling [3].

Table 2: Representative Machine Learning Approaches for Quantum Chemistry

| Method | Approach | Reported Speedup | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrbNet | Graph neural network [2] | 1,000x faster [2] | Nodes represent electron orbitals rather than atoms; naturally connected to Schrödinger equation |

| sGDML | Kernel regression [4] | Not specified (enables ab initio-quality trajectories) [4] | Achieves remarkable agreement with experimental results |

| General MLIPs | Various architectures (NNs, kernel methods) [3] | Enables large-scale simulations [3] | Trained on DFT data; predicts energy/forces from atomic positions |

A key innovation in advanced MLIPs like OrbNet is their departure from conventional atom-based representations. Instead of organizing atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, OrbNet constructs a graph where the nodes are electron orbitals and the edges represent interactions between orbitals [2]. This approach has "a much more natural connection to the Schrödinger equation," according to Caltech's Tom Miller, one of OrbNet's developers [2]. This domain-specific feature enables the model to extrapolate to molecules up to 10 times larger than those present in training data—capability that Anima Anandkumar notes is "impossible" for standard deep-learning models that only learn to interpolate on training data [2].

Benchmarking Methodologies and Performance Comparisons

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for validating the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning potentials against established ab initio methods. These benchmarks typically evaluate both static errors (energy and force prediction accuracy) and dynamic errors (performance in molecular simulations) [4]. The following experimental protocol outlines a comprehensive benchmarking approach:

Experimental Protocol for MLP Benchmarking

Training Set Curation: Assemble diverse molecular configurations covering relevant regions of chemical space. For example, the PubChemQCR dataset provides approximately 3.5 million relaxation trajectories and over 300 million molecular conformations computed at various levels of theory [3].

Reference Calculations: Perform high-level ab initio calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) or DFT with appropriate functionals) to generate reference energies and forces for training and test sets [4] [3].

Model Training: Train MLIPs on subsets of reference data, typically using energy and force labels. The force information is particularly valuable as it provides rich gradient information about the potential energy surface [3].

Static Property Validation: Evaluate trained models on held-out test configurations by comparing predicted energies and forces to reference ab initio values using metrics like mean absolute error (MAE) or root mean square error (RMSE) [4].

Dynamic Simulation Validation: Perform molecular dynamics or geometry optimization simulations using both the MLIP and reference ab initio method, then compare ensemble-average properties, reaction rates, or free energy profiles [4].

Experimental Comparison: Where possible, validate simulations against experimental observables such as spectroscopic data or thermodynamic measurements [4].

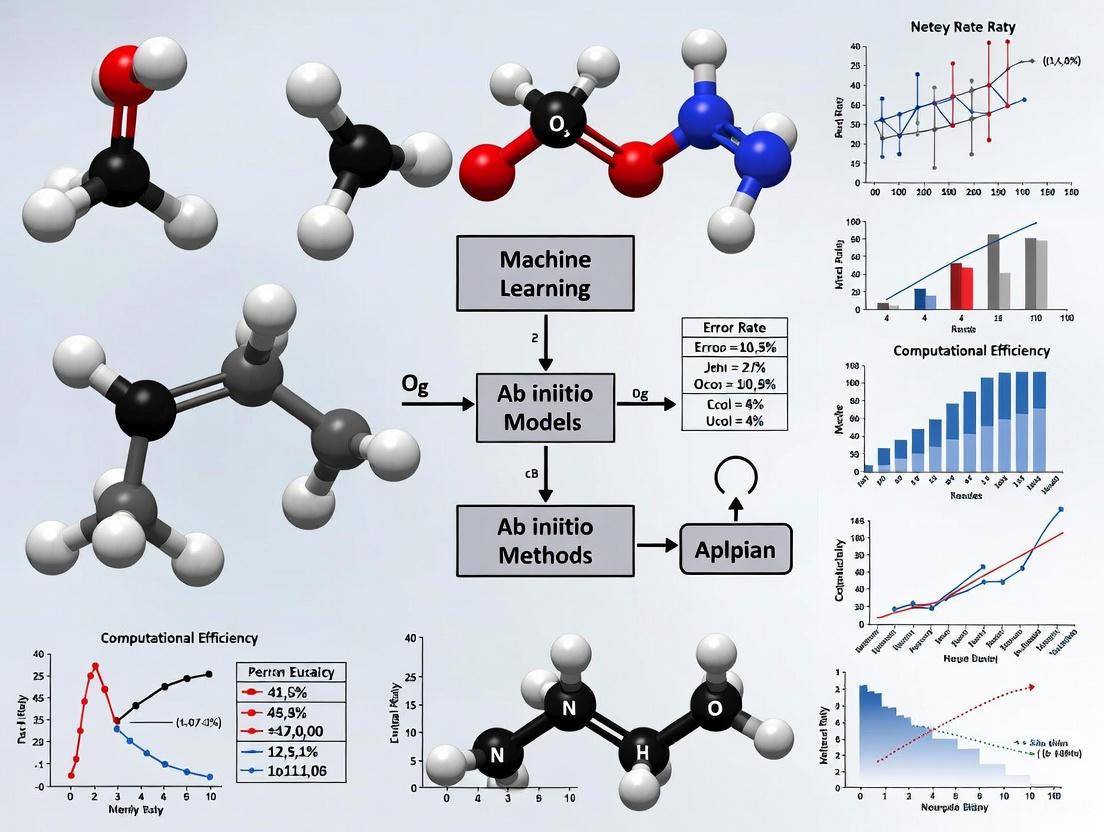

Diagram: MLIP Benchmarking Workflow. This workflow outlines the systematic process for validating machine learning interatomic potentials against ab initio methods and experimental data.

Quantitative Benchmarking Results

In a novel comparison for the HBr⁺ + HCl system, both neural networks and kernel regression methods were benchmarked for a global potential energy surface covering multiple dissociation channels [4]. Comparison with ab initio molecular dynamics simulations enabled one of the first direct comparisons of dynamic, ensemble-average properties, with results showing "remarkable agreement for the sGDML method for training sets of thousands to tens of thousands of molecular configurations" [4].

The PubChemQCR benchmarking study evaluated nine representative MLIP models on a massive dataset containing over 300 million molecular conformations [3]. This comprehensive evaluation highlighted that MLIPs must generalize not only to stable geometries but also to intermediate, non-equilibrium conformations encountered during atomistic simulations—a critical requirement for their practical utility as ab initio surrogates [3].

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Computational Chemistry Methods

| Method Type | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Typical Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-level Ab Initio (CCSD(T)) | Extremely high (O(N⁷)) [1] | Very high (chemical accuracy) [1] | Small molecules (<20 atoms) |

| Medium-level Ab Initio (DFT) | High (O(N³)-O(N⁴)) [1] | High (depends on functional) [1] | Medium molecules (hundreds of atoms) |

| Machine Learning (OrbNet) | 1,000x faster than QC [2] | Near-ab initio [2] | Molecules 10x larger than training [2] |

| Machine Learning (sGDML) | Fast predictive power [4] | Remarkable experimental agreement [4] | Reaction dynamics |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Advancing research at the intersection of machine learning and quantum chemistry requires specialized computational tools and datasets. The following table details key resources that enable this work:

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for MLIP Development and Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChemQCR [3] | Dataset | Training/evaluating MLIPs | 3.5M relaxation trajectories, 300M+ conformations with energy/force labels |

| OrbNet [2] | Software/model | Quantum chemistry calculations | Graph neural network using orbital features; 1000x speedup |

| sGDML [4] | Software/model | Constructing PES | Kernel regression; good experimental agreement |

| QM9 [3] | Dataset | Method development | ~130k small molecules with 19 quantum properties |

| ANI-1x [3] | Dataset | Training MLIPs | 20M+ conformations across 57k molecules |

| MPTrj [3] | Dataset | Materials optimization | ~1.5M conformations for materials |

These resources have been instrumental in advancing the field. For example, the development of OrbNet was enabled by training on approximately 100,000 molecules, allowing it to "predict the structure of molecules, the way in which they will react, whether they are soluble in water, or how they will bind to a protein" according to Miller [2]. Similarly, the creation of the PubChemQCR dataset addressed critical limitations of prior datasets, including "restricted element coverage, limited conformational diversity, or the absence of force information" [3].

Diagram: MLIP Development Cycle. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of developing machine learning interatomic potentials, from data collection to application deployment.

The O(N³) computational cost of traditional ab initio methods represents a fundamental challenge that has constrained computational chemistry for decades. While these methods provide essential accuracy benchmarks, their steep scaling with system size has limited their application to realistically complex systems relevant to drug discovery and materials science. Machine learning interatomic potentials have emerged as powerful alternatives that combine near-ab initio accuracy with dramatically reduced computational cost, often achieving speedups of 1000x or more [2].

The benchmarking studies and methodologies reviewed here demonstrate that MLIPs can achieve remarkable accuracy while enabling simulations at previously inaccessible scales. However, important challenges remain, including improving transferability to diverse chemical environments, integrating better physical constraints, and expanding to more complex molecular systems including biomolecules and functional materials. Future developments will likely focus on creating more data-efficient training approaches, developing uncertainty quantification methods, and expanding the range of physical properties that can be predicted accurately.

As these machine learning approaches continue to mature, they promise to redefine the boundaries of computational quantum chemistry, making high-accuracy simulations routine for systems of biologically and technologically relevant complexity. This progress will ultimately accelerate scientific discovery across fields from drug development to renewable energy materials, finally overcoming the fundamental challenge of computational scaling that has long limited ab initio methods.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a fundamental tool for revealing microscopic dynamical behavior of matter, playing a key role in materials design, drug discovery, and analysis of chemical reaction mechanisms. Traditional MD simulations rely on classical force fields—parameterized potential functions inspired by physical principles—to describe interatomic interactions. While these empirical potentials enable efficient computation, their fixed functional forms struggle to capture complex quantum effects, limiting their predictive accuracy. In contrast, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) provides more accurate potential energy surfaces using first-principles calculations but suffers from prohibitive computational complexity that hinders application to large systems and long timescales. This intrinsic trade-off between accuracy and efficiency has remained a fundamental bottleneck in the advancement of atomistic simulation techniques.

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative approach that bridges this divide. By leveraging data-driven models to fit the results of first-principles calculations, MLIPs offer greater flexibility in capturing complex atomic interactions while achieving an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. This review provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis of modern MLIP architectures against classical force fields and ab initio methods, highlighting their transformative potential across diverse scientific domains, with particular emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

Methodological Framework: Benchmarking MLIP Performance

Performance Metrics and Evaluation Protocols

The benchmarking of MLIPs against classical force fields and ab initio methods follows standardized protocols focusing on key quantitative metrics:

- Accuracy Validation: Root mean square errors (RMSEs) of energy and force predictions compared to density functional theory (DFT) calculations, typically measured in meV/atom for energy and meV/Å for forces.

- Computational Efficiency: Simulation speed relative to ab initio methods, measured as orders of magnitude improvement while maintaining near-ab initio accuracy.

- Data Efficiency: The number of reference structures required to achieve chemical accuracy (conventionally ∼4 kJ mol⁻¹ or ~40 meV/atom) for target systems.

- Thermodynamic Properties: Accuracy in predicting phase stability, sublimation enthalpies, and other temperature-dependent properties against experimental data.

Experimental Workflow for MLIP Benchmarking

The following workflow illustrates the standardized methodology for evaluating and comparing MLIP performance:

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparison of Modern MLIPs

Accuracy and Efficiency Metrics for Tobermorite Systems

Recent systematic comparisons between NequIP (a contemporary equivariant graph neural network) and DPMD (a previously established descriptor-based MLIP) on tobermorite minerals—structural analogs of cementitious calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H)—reveal substantial advancements in MLIP capabilities [5].

Table 1: Performance comparison of NequIP and DPMD for tobermorite systems benchmarked against DFT

| Performance Metric | NequIP | DPMD | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy RMSE (meV/atom) | < 0.5 | 1-2 orders higher | 10-100× |

| Force RMSE (meV/Å) | < 50 | 1-2 orders higher | 10-100× |

| Computational Speed | ~4 orders faster than DFT | ~3 orders faster than DFT | ~10× faster than DPMD |

| Bulk Modulus Prediction | Closer to DFT values | Larger deviation from DFT | >50% improvement |

| Data Efficiency | High (lower training data requirements) | Moderate | Significant improvement |

The exceptional performance of NequIP is attributed to its rotation-equivariant representations implemented through a directional message passing scheme, which extends each atom's feature vector into higher-order tensors through irreducible representations [5]. This architectural advancement enables more accurate capturing of complex atomic interactions while maintaining computational efficiency.

Performance Under Extreme Conditions

The accuracy of universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) under high-pressure conditions (0-150 GPa) reveals both the capabilities and limitations of current approaches, highlighting the critical importance of training data composition [6].

Table 2: Energy RMSE (meV/atom) of universal MLIPs across pressure ranges

| Model | 0 GPa | 25 GPa | 50 GPa | 75 GPa | 100 GPa | 125 GPa | 150 GPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet | 0.42 | 1.28 | 1.56 | 1.58 | 1.50 | 1.44 | 1.39 |

| MACE-MPA-0 | 0.35 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 1.16 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 1.15 |

| Fine-tuned Models | < 0.30 | < 0.50 | < 0.60 | < 0.65 | < 0.70 | < 0.75 | < 0.80 |

The performance degradation observed in general-purpose uMLIPs under high pressure originates from fundamental limitations in training data distribution rather than algorithmic constraints. Notably, targeted fine-tuning on high-pressure configurations can significantly restore model robustness, reducing prediction errors by >80% compared to general-purpose force fields while maintaining a 4× speedup in MD simulations [6].

Data Efficiency in Molecular Crystal Applications

The application of foundation MLIPs to molecular crystals demonstrates remarkable improvements in data efficiency. Fine-tuned MACE-MP-0 models achieve sub-chemical accuracy for molecular crystals with respect to the underlying DFT potential energy surface using as few as ~200 data points—an order of magnitude improvement over previous state-of-the-art approaches [7].

This enhanced data efficiency enables accurate calculation of sublimation enthalpies for pharmaceutical compounds including paracetamol and aspirin, accounting for anharmonicity and nuclear quantum effects with average errors <4 kJ mol⁻¹ compared to experimental values [7]. Such accuracy at computationally feasible costs establishes MLIPs as viable tools for routine screening of molecular crystal stabilities in pharmaceutical development.

Table 3: Essential resources for MLIP development and application

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| MLIP Architectures | NequIP, DPMD, MACE, M3GNet | Core model architectures with varying efficiency-accuracy trade-offs |

| Benchmarking Datasets | Tobermorite (9, 11, 14 Å), X23 molecular crystals, High-pressure Alexandria | Standardized systems for MLIP validation and comparison |

| Simulation Packages | LAMMPS, VASP | MD simulation execution and ab initio reference calculations |

| Training Frameworks | IPIP, PhaseForge | Iterative training and fine-tuning of specialized MLIPs |

| Property Prediction | ATAT, Phonopy | Thermodynamic property calculation and phase diagram construction |

Advanced Training Methodologies: Overcoming Data Scarcity

Iterative Pretraining Frameworks

The Iterative Pretraining for Interatomic Potentials (IPIP) framework addresses critical challenges in MLIP development through a cyclic optimization approach that systematically enhances model performance without introducing additional quantum calculations [8]. The methodology employs a forgetting mechanism to prevent iterative training from converging to suboptimal local minima.

This iterative framework achieves over 80% reduction in prediction error and up to 4× speedup in challenging multi-element systems like Mo-S-O, enabling fast and accurate simulations where conventional force fields typically fail [8]. Unlike general-purpose foundation models that often sacrifice specialized accuracy for breadth, IPIP maintains high efficiency through lightweight architectures while achieving superior domain-specific performance.

Foundation Model Fine-tuning for Specialized Applications

The paradigm of fine-tuning foundation MLIPs pre-trained on large DFT datasets has emerged as a powerful strategy for achieving high accuracy with minimal specialized data. The MACE-MP-0 foundation model, pre-trained on MPtrj (a subset of optimized inorganic crystals from the Materials Project database), can be fine-tuned to reproduce potential energy surfaces of molecular crystals with sub-chemical accuracy using only ~200 specialized data structures [7].

This approach demonstrates that foundation models qualitatively reproduce underlying potential energy surfaces for wide ranges of materials, serving as optimal starting points for specialization. The fine-tuning process involves:

- Generating minimal training sets by sampling molecular crystal phase space around equilibrium volumes at low temperatures using the foundation model for initial MD simulations.

- Randomly sampling limited structures (~10 per volume) from MD trajectories as training data.

- Fine-tuning foundation model parameters to minimize errors on energy, forces, and stress for the target system.

- Validating model performance on equation of state and vibrational energy properties.

Application in Pharmaceutical Development: Accelerating Drug Discovery

The transformative impact of MLIPs extends significantly to pharmaceutical development, where they enable accurate modeling of molecular crystals crucial for drug stability, solubility, and bioavailability. Traditional force fields often lack the precision required for predicting sublimation enthalpies and polymorph stability, while AIMD remains computationally prohibitive for routine screening [7].

MLIPs fine-tuned from foundation models now facilitate the calculation of finite-temperature thermodynamic properties with sub-chemical accuracy, incorporating essential anharmonicity and nuclear quantum effects that are critical for pharmaceutical applications. This capability is particularly valuable for predicting relative stability of competing polymorphs, where small energy differences dictate stability but require exceptional accuracy to resolve [7].

The integration of MLIPs into pharmaceutical development pipelines represents a significant advancement over traditional drug discovery approaches, which face enormous economic challenges with costs exceeding $2 billion per approved drug and timelines spanning 10-15 years [9]. By enabling accurate in silico prediction of molecular crystal properties, MLIPs contribute to the paradigm shift from "make-then-test" to "predict-then-make" approaches, potentially slashing years and billions of dollars from the development lifecycle.

Benchmarking analyses conclusively demonstrate that modern MLIP architectures—particularly equivariant graph neural networks like NequIP and MACE—consistently outperform classical force fields in prediction accuracy while maintaining computational efficiencies several orders of magnitude greater than ab initio methods. The iterative pretraining and foundation model fine-tuning paradigms further address data scarcity challenges, enabling high-fidelity modeling of complex systems with minimal specialized training data.

Future development trajectories will likely focus on several critical frontiers: (1) enhancing model robustness under extreme conditions through targeted training data strategies; (2) expanding applications to reactive systems and complex molecular interactions prevalent in pharmaceutical contexts; and (3) improving accessibility through integrated workflows and standardized benchmarking protocols. As these advancements mature, MLIPs are positioned to fundamentally transform computational materials science and drug development, enabling predictive simulations at unprecedented scales and accuracies.

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) represent a transformative advancement in computational materials science and chemistry, bridging the critical gap between accurate but computationally expensive ab initio methods and efficient but often inaccurate classical force fields [10]. By learning the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies from quantum mechanical reference data, MLIPs enable molecular dynamics simulations of large systems over extended timescales with near-ab initio accuracy [11]. This capability is revolutionizing fields ranging from drug discovery to materials design, where understanding atomic-scale interactions is paramount [12] [13]. The performance and applicability of any MLIP are determined by three foundational pillars: the strategies employed for data generation, the descriptors used to represent atomic environments, and the learning algorithms that map these descriptors to potential energies and forces. This guide examines these core components through the lens of benchmarking against ab initio methods, providing researchers with a structured framework for evaluating and selecting MLIP approaches for their specific scientific applications.

Core Component I: Data Generation and Training Protocols

The accuracy and transferability of any MLIP are fundamentally constrained by the quality and diversity of the training data. Data generation strategies have evolved from system-specific approaches to the development of universal foundation models, with fine-tuning emerging as a critical technique for achieving chemical accuracy on specialized tasks.

Foundational Datasets for Pre-training

Large-scale MLIP foundation models are typically pre-trained on extensive datasets derived from high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations. These datasets encompass diverse chemical spaces to ensure broad transferability:

- Materials Project (MPtrj): Contains DFT calculations for over 200,000 materials, often subsampled to approximately 146,000 structures with 1.5 million DFT calculations using PBE+U functionals [11].

- Alexandria Database: Comprises DFT structure relaxation trajectories of 3 million materials with 30 million DFT calculations, with a commonly used subset (sAlex) containing 10 million calculations [11].

- Open Materials 2024 (OMat24) and Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25): From Meta's FAIRchem, each containing over 100 million DFT calculations with different exchange-correlation functionals (PBE+U and B97M-V, respectively) [11].

These foundational datasets enable the development of potentials like MACE-MP, GRACE, MatterSim, and ORB that demonstrate remarkable zero-shot capabilities across diverse chemical systems [14].

Fine-tuning for System-Specific Accuracy

While foundation models provide broad coverage, achieving chemical accuracy for specific systems often requires fine-tuning with targeted data. Recent research demonstrates that fine-tuning transforms foundational MLIPs to achieve consistent, near-ab initio accuracy across diverse architectures [11].

Fine-tuning Protocol:

- Data Generation: Short ab initio molecular dynamics trajectories are run for the target system, with frames equidistantly sampled to capture representative atomic configurations [11].

- Dataset Size: Typically hundreds of data points (structures with associated energies and forces) are sufficient, representing 10-20% of what would be required to train a model from scratch [14].

- Training Approach: Frozen transfer learning, where only a subset of model parameters are updated, has proven particularly effective for maximizing data efficiency while maintaining transferability [14].

Table 1: Fine-tuning Performance Across MLIP Architectures

| MLIP Architecture | Force Error Reduction | Energy Error Improvement | Training Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | 5-15× | 2-4 orders of magnitude | ~20% of from-scratch data |

| GRACE | 5-15× | 2-4 orders of magnitude | ~20% of from-scratch data |

| SevenNet | 5-15× | 2-4 orders of magnitude | ~20% of from-scratch data |

| MatterSim | 5-15× | 2-4 orders of magnitude | ~20% of from-scratch data |

| ORB | 5-15× | 2-4 orders of magnitude | ~20% of from-scratch data |

Experimental benchmarking across seven chemically diverse systems including CsH₂PO₄, organic crystals, and solvated phenol demonstrates that fine-tuning universally enhances force predictions by factors of 5-15 and improves energy accuracy by 2-4 orders of magnitude, regardless of the underlying architecture (equivariant/invariant, conservative/non-conservative) [11].

Diagram 1: Fine-tuning workflow for MLIP foundation models. This process typically reduces force errors by 5-15× and energy errors by 2-4 orders of magnitude with only 10-20% of the data required for from-scratch training [11] [14].

Core Component II: Atomic Environment Descriptors

The descriptor framework determines how atomic configurations are transformed into mathematical representations suitable for machine learning. Descriptors encode the fundamental symmetries of interatomic interactions and critically impact model accuracy and data efficiency.

Descriptor Types and Their Properties

MLIP descriptors fall into two primary categories: explicit featurization approaches that hand-craft representations preserving physical symmetries, and implicit approaches that leverage graph neural networks to learn representations directly from atomic configurations [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Major MLIP Descriptor Types

| Descriptor Type | Key Examples | Symmetry Handling | Data Efficiency | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Featurization | Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) [10], Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [10] | Built-in translational, rotational, and permutational invariance | High (uses physical prior knowledge) | Moderate to high (descriptor calculation scales with system size) |

| Implicit (GNN-based) | MACE [11], GRACE [11], Allegro [10] | Learned through equivariant operations | Moderate to high (requires sufficient training data) | Varies by architecture; optimized GNNs can be highly efficient |

| Behler-Parrinello | ANI [10] | Built-in invariance through symmetry functions | High for organic molecules | Low to moderate |

Equivariant vs. Invariant Architectures

A critical distinction in modern MLIP descriptors is between equivariant and invariant architectures:

- Equivariant descriptors (e.g., in MACE, SevenNet) transform predictably under rotational operations, explicitly preserving vectorial relationships essential for modeling directional interactions like covalent bonds [11].

- Invariant descriptors (e.g., in MatterSim, ORB) produce the same output regardless of rotational transformations, simplifying the learning problem but potentially losing directional information [11].

Recent benchmarking reveals that both architectures can achieve comparable accuracy after fine-tuning, suggesting that the training strategy may be as important as the architectural choice for system-specific applications [11].

Core Component III: Learning Algorithms and Model Architectures

The learning algorithm defines the functional mapping from atomic descriptors to potential energies and forces. Modern MLIP architectures have evolved from simple neural networks to sophisticated graph-based models that naturally capture many-body interactions.

Taxonomy of MLIP Architectures

Table 3: Classification of Major MLIP Learning Architectures

| Architecture Category | Key Representatives | Energy Conservation | Long-Range Interactions | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equivariant Message Passing | MACE [11] [14], GRACE [11] | Conservative (forces as energy gradients) | Limited without enhancements | Complex molecules, materials with directional bonding |

| Invariant Graph Networks | MatterSim [11], CHGNet [14] | Conservative (forces as energy gradients) | Limited without enhancements | Bulk materials, crystalline systems |

| Non-Conservative Force Predictors | ORB [11] | Non-conservative (direct force prediction) | Can be incorporated | Specialized applications where energy conservation is secondary |

| Atomic Cluster Expansion | ACE [10] | Conservative (forces as energy gradients) | Can be incorporated | Data-efficient learning for materials families |

Performance Benchmarking AgainstAb InitioMethods

Rigorous validation against ab initio reference calculations is essential for establishing MLIP reliability. Standard benchmarking protocols assess multiple accuracy metrics:

- Force Errors: Typically reported as root mean square error (RMSE) in meV/Å, with fine-tuned models achieving 5-15× improvement over foundation models [11].

- Energy Errors: Reported as RMSE in meV/atom, with fine-tuning improving accuracy by 2-4 orders of magnitude [11].

- Property Predictions: Validation against experimental or ab initio properties such as diffusion coefficients, vibrational spectra, and phase stability [14].

For the H₂/Cu surface adsorption system, frozen transfer learning with MACE (MACE-MP-f4) achieved accuracy comparable to from-scratch models using only 20% of the training data (664 configurations vs. 3376 configurations) [14]. This demonstrates the remarkable data efficiency of modern fine-tuning approaches.

Diagram 2: MLIP architecture and benchmarking workflow. Models are trained to reproduce ab initio reference energies and forces, with performance validated on held-out configurations and experimental observables [11] [14] [10].

Integrated Workflow: From Data Generation to Validated MLIP

Implementing a robust MLIP requires careful integration of all three components. The following workflow represents current best practices for developing system-specific potentials:

Unified MLIP Development Protocol

- Foundation Model Selection: Choose a pre-trained model (MACE, GRACE, SevenNet, MatterSim, or ORB) based on the target system's characteristics and available computational resources [11].

- Target Data Generation: Perform short ab initio molecular dynamics simulations (10-100 ps), sampling frames equidistantly to capture relevant configurations [11].

- Frozen Fine-tuning: Implement transfer learning with partially frozen weights (typically 40-80% of parameters fixed) to maximize data efficiency [14].

- Validation Against Ab Initio: Quantify force and energy errors on held-out configurations from the target system [11].

- Property Validation: Validate against experimental observables or specialized ab initio calculations not included in training [14].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for MLIP Development

Table 4: Essential Software and Resources for MLIP Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLIP Frameworks | MACE [11] [14], GRACE [11], SevenNet [11] | Core architecture implementation | Open source |

| Fine-tuning Toolkits | aMACEing Toolkit [11], mace-freeze patch [14] | Unified interfaces for model adaptation | Open source |

| Ab Initio Codes | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian | Reference data generation | Mixed (open source and commercial) |

| Training Datasets | Materials Project [11], Alexandria [11], OMat24/OMol25 [11] | Foundation model pre-training | Open access |

| Validation Tools | MLIP Arena [11], Matbench Discovery [11] | Performance benchmarking | Open source |

Machine learning interatomic potentials have matured into powerful tools that successfully bridge the accuracy-efficiency gap in atomistic simulation. The core components—data generation strategies, descriptor design, and learning algorithms—have evolved toward integrated frameworks where foundation models provide starting points for efficient system-specific refinement. Current evidence demonstrates that fine-tuning universal models with frozen transfer learning achieves chemical accuracy with dramatically reduced data requirements, making high-fidelity molecular dynamics accessible for increasingly complex systems [11] [14].

The convergence of architectural innovations—particularly equivariant graph neural networks—with sophisticated transfer learning strategies represents the current state-of-the-art. While differences persist between alternative approaches, benchmarking reveals that fine-tuning can harmonize performance across diverse architectures, making the choice of training strategy as critical as the selection of the underlying model [11]. As MLIP methodologies continue to advance, they are poised to expand the frontiers of computational molecular science, enabling predictive simulations of complex phenomena across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) have revolutionized atomistic simulations by offering a transformative pathway to bridge the gap between the accuracy of quantum mechanical methods and the computational efficiency of classical molecular dynamics [15]. By leveraging high-fidelity ab initio data to construct surrogate models, MLIPs implicitly encode electronic effects, enabling faithful recreation of the potential energy surface (PES) across diverse chemical environments without explicitly propagating electronic degrees of freedom [15]. Their robustness hinges on accurately learning the mapping from atomic coordinates to energies and forces, thereby achieving near-ab initio accuracy across extended time and length scales that were previously inaccessible [15]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of key MLIP architectures, including DeePMD, Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP), and modern equivariant Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), focusing on their algorithmic approaches, performance characteristics, and applications in computational materials science and drug development.

DeePMD and the Deep Potential Scheme

The DeePMD framework formulates the total potential energy as a sum of atomic contributions, each represented by a fully nonlinear function of local environment descriptors defined within a prescribed cutoff radius [15]. Implemented in the widely used DeePMD-kit package, this approach preserves translational, rotational, and permutational symmetries through an embedding network [16]. The framework encodes smooth neighboring density functions to characterize atomic surroundings and maps these descriptors through deep neural networks, enabling quantum mechanical accuracy with computational efficiency comparable to classical molecular dynamics [15].

Computational Procedure: The computation involves two primary components: a descriptor ((\mathcal{D})) and a fitting net ((\mathcal{N})) [17]. The descriptor calculates symmetry-preserving features from the input environment matrix, while the fitting net learns the relationship between these local environment features and the atomic energy [17]. The potential energy of the whole system is expressed as the sum of atomic energy contributions: (E=\sumi Ei) [17]. To reduce computational burden, DeePMD-kit employs a tabulation method that approximates the embedding network using fifth-order polynomials through the Weierstrass approximation [17].

Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP)

The Gaussian Approximation Potential represents a different philosophical approach to MLIPs, based on kernel-based learning and Gaussian process regression. GAP-20, a specific implementation, has demonstrated remarkable accuracy for carbon nanomaterials [18]. In benchmark studies on C₆₀ fullerenes, GAP-20 attained a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of merely 0.014 Å over a set of 29 unique C–C bond distances, significantly outperforming traditional empirical force fields which showed RMSDs ranging between 0.023 (LCBOP-I) and 0.073 (EDIP) Å [19]. This performance was on par with semiempirical quantum methods PM6 and AM1, while being computationally more efficient [19].

Equivariant Graph Neural Networks

Equivariant GNNs represent the cutting edge in MLIP architecture, explicitly embedding the inherent symmetries of physical systems directly into their network layers [15]. Unlike approaches that rely on data augmentation to approximate symmetry, equivariant architectures integrate group actions from the Euclidean groups SO(3) (rotations), SE(3) (rotations and translations), and E(3) (including reflections) directly into their internal feature transformations [15]. This ensures that each layer preserves physical consistency under relevant symmetry operations, guaranteeing that scalar predictions (e.g., total energy) remain invariant while vector and tensor targets (e.g., forces, dipole moments) exhibit the correct equivariant behavior [15].

Key Architectures:

- NequIP: Explores higher-order tensor contributions to performance through equivariant layers [15].

- Allegro: Adapts a model decoupling approach and has demonstrated capability to simulate 100 million atoms on 5120 A100 GPUs [16].

- MACE: Employs a message passing mechanism with rotational symmetry orders [20].

- DPA-2: Utilizes representation-transformer layers with gated self-attention mechanisms [20].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Accuracy Comparison Across MLIP Architectures

Table 1: Accuracy Benchmarks Across MLIP Architectures

| MLIP Architecture | System Tested | Accuracy Metric | Performance Result | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAP-20 | C₆₀ fullerene | Bond distance RMSD | 0.014 Å | B3LYP-D3BJ/def2-TZVPPD |

| Deep Potential (DeePMD) | Water | Energy MAE | <1 meV/atom | DFT (explicit) |

| Deep Potential (DeePMD) | Water | Force MAE | <20 meV/Å | DFT (explicit) |

| DPA-2, MACE, NequIP | QDπ dataset (15 elements) | Force RMSE | ~25-35 meV/Å | ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD |

The benchmarking data reveals distinctive performance characteristics across MLIP architectures. GAP-20 demonstrates exceptional accuracy for specific material systems like fullerenes, achieving near-density functional theory (DFT) level precision for bond distances [19]. DeePMD shows remarkable consistency across diverse systems, maintaining high accuracy for both energies and forces in complex molecular systems like water [15]. Modern equivariant GNNs, including DPA-2, MACE, and NequIP, demonstrate robust performance across broad chemical spaces, with force errors typically in the 25-35 meV/Å range when evaluated against high-level quantum chemical references [20].

Computational Performance and Scaling

Table 2: Computational Performance and Scaling of MLIP Frameworks

| MLIP Framework | Hardware Setup | System Size | Simulation Speed | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD-kit (optimized) | 12,000 Fugaku nodes | 0.5M atoms | 149 ns/day (Cu), 68.5 ns/day (H₂O) | 31.7× faster than previous SOTA [16] |

| Allegro | 5,120 A100 GPUs | 100M atoms | Not specified | Model decoupling enables extreme scaling [16] |

| DeePMD-kit (baseline) | 218,800 Fugaku cores | 2.1M atoms | 4.7 ns/day | Previous SOTA performance [16] |

| SNAP ML-IAP | 204,600 Summit cores + 27,300 GPUs | 1B atoms | 1.03 ns/day | Classical ML-IAP for comparison [16] |

Computational performance varies significantly across MLIP frameworks, with recent optimizations delivering remarkable improvements. The optimized DeePMD-kit demonstrates unprecedented simulation speeds, reaching 149 nanoseconds per day for a copper system of 0.54 million atoms on 12,000 Fugaku nodes [16]. This represents a 31.7× improvement over previous state-of-the-art performance [16]. Key optimizations enabling these gains include a node-based parallelization scheme that reduces communication by 81%, kernel optimization with SVE-GEMM and mixed precision, and intra-node load balancing that reduces atomic dispersion between MPI ranks by 79.7% [16].

Performance Modeling with DP-perf

The DP-perf performance model provides an interpretable framework for predicting DeePMD-kit performance across emerging supercomputers [17]. By leveraging characteristics of molecular systems and machine configurations, DP-perf can accurately predict execution time with mean absolute percentage errors of 5.7%/8.1%/14.3%/13.1% on Tianhe-3F, new Sunway, Fugaku, and Summit supercomputers, respectively [17]. This enables researchers to select optimal computing resources and configurations for various objectives without requiring real runs [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Training and Validation Protocols

Data Requirements and Preparation: MLIP training requires extensive, high-quality quantum mechanical datasets [15]. Publicly accessible materials datasets are orders of magnitude smaller than those in image or language domains, presenting a fundamental limitation for universal transferability [15]. DFT datasets with meta-generalized gradient approximation (meta-GGA) exchange-correlation functionals offer markedly improved generalizability compared to semi-local approximations [15].

Consistent Benchmarking Framework: The DeePMD-GNN plugin enables consistent training and benchmarking of different GNN potentials by providing a unified interface [20]. This addresses challenges arising from separate software ecosystems that can lead to inconsistent benchmarking practices due to differences in optimization algorithms, loss function definitions, learning rate treatments, and training step implementations [20].

Cross-Architecture Validation: For the QDπ dataset benchmark, models are trained consistently against over 1.5 million structures with energies and forces calculated at the ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD level, split into training and test sets with a 19:1 ratio [20]. This comprehensive dataset covers 15 elements collected from subsets of SPICE and ANI datasets [20].

Δ-MLP Correction Protocols

The range-corrected ΔMLP formalism provides a sophisticated approach for multi-fidelity modeling, particularly in QM/MM applications [20]. The total energy is expressed as:

[E = E{\text{QM}} + E{\text{QM/MM}} + E{\text{MM}} + \Delta E{\text{MLP}}]

Where the MLP corrects both the QM and nearby QM/MM interactions, producing a smooth potential energy surface as MM atoms enter and exit the vicinity of the QM region [20]. For GNN potentials adapted to this approach, the MM atom energy bias is set to zero and the GNN topology excludes edges connecting pairs of MM atoms [20].

Interoperability and Ecosystem Integration

The current MLIP landscape presents significant interoperability challenges due to limited interoperability between packages [20]. The DeePMD-GNN plugin addresses this by extending DeePMD-kit capabilities to support external GNN potentials, enabling seamless integration of popular GNN-based models like NequIP and MACE within the DeePMD-kit ecosystem [20]. This unified approach allows GNN models to be used within combined quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) applications using the range-corrected ΔMLP formalism [20].

Table 3: MLIP Software Ecosystems and Capabilities

| Software Package | Primary MLIPs Supported | Key Features | Interoperability Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD-kit | Deep Potential models | High-performance MD, billion-atom simulations | Base framework for plugins |

| SchNetPack | SchNet | Molecular property prediction | Separate ecosystem |

| TorchANI | ANI models | Drug discovery applications | Separate ecosystem |

| NequIP/MACE packages | NequIP, MACE | Equivariant message passing | Integrated via DeePMD-GNN |

| DeePMD-GNN plugin | NequIP, MACE, DPA-2 | Unified training/benchmarking | Interoperability layer |

Visualization of MLIP Architecture Relationships

MLIP Architecture Evolution and Relationships: This diagram illustrates the historical development and relationships between major MLIP architectures, from traditional empirical potentials to modern equivariant graph neural networks, highlighting their progressive improvements in accuracy, transferability, and computational efficiency.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for MLIP Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | QM9 [15] | Molecular property prediction | 134k small organic molecules (~1M atoms) |

| MD17/MD22 [15] | Energy and force prediction | MD trajectories for organic molecules | |

| QDπ dataset [20] | Cross-architecture benchmarking | 1.5M structures, 15 elements, SPICE/ANI subsets | |

| Software Frameworks | DeePMD-kit [17] [16] | Deep Potential implementation | High-performance, proven scalability to billions of atoms |

| DeePMD-GNN plugin [20] | Interoperability layer | Unified training/inference for GNN potentials | |

| DP-GEN [20] | Automated training | Active learning with query-by-committee strategy | |

| Computational Resources | Fugaku supercomputer [16] | Large-scale MD simulation | ARM V8, 48 CPU cores/node, 6D torus network |

| Summit supercomputer [16] | GPU-accelerated simulation | CPU-GPU heterogeneous architecture | |

| Reference Methods | ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD [20] | High-accuracy reference | Gold standard for energy/force calculations |

| GFN2-xTB [20] | Semiempirical base method | Efficient QM for ΔMLP corrections |

The MLIP landscape has evolved dramatically from specialized single-purpose potentials to sophisticated, scalable frameworks capable of simulating billions of atoms with ab initio accuracy. DeePMD demonstrates exceptional performance in extreme-scale simulations, GAP provides remarkable accuracy for specific material systems, and equivariant GNNs offer cutting-edge performance across broad chemical spaces. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing interpretability, improving data efficiency through active learning, developing multi-fidelity frameworks that seamlessly integrate quantum mechanics with machine learning potentials, and creating more scalable message-passing architectures [15]. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate materials discovery and provide deeper mechanistic insights into complex material and physical systems, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where accurate molecular simulations can dramatically impact drug development pipelines.

From Theory to Therapy: Methodological Advances and Drug Discovery Applications

Automating Potential Energy Surface Exploration with Frameworks like autoplex

Machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have become indispensable tools in computational materials science, enabling large-scale atomistic simulations with quantum-mechanical accuracy where direct ab initio methods would be computationally prohibitive [21] [15]. These surrogate models are trained on reference data derived from quantum mechanical calculations, typically density functional theory (DFT), and can capture complex atomic interactions across diverse chemical environments [15]. However, a significant bottleneck persists in their development: the manual generation and curation of high-quality training datasets remains a time-consuming and expertise-dependent process [21] [22].

The emergence of automated frameworks represents a paradigm shift in this field. This guide objectively compares the performance and capabilities of one such framework, autoplex ("automatic potential-landscape explorer"), against other prevalent approaches for exploring potential energy surfaces (PES) and developing MLIPs [21]. We frame this comparison within the broader context of benchmarking machine learning potentials against ab initio methods, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed for informed tool selection.

Comparative Analysis of PES Exploration Methodologies

The core challenge in MLIP development is the thorough exploration of the potential-energy surface—sampling not just stable minima but also transition states and high-energy configurations—to create a robust and generalizable model [21]. The table below compares the primary methodologies used for this task.

Table 1: Comparison of Methodologies for PES Exploration and MLIP Development

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Typical Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Dataset Curation [21] | Domain expert selects specific configurations (e.g., for fracture or phase change). | High relevance for a specific task or property. | Labor-intensive; lacks transferability; prone to human bias. | Highly variable; often insufficient for general-purpose potentials. |

| Active Learning [21] [15] | Iterative model refinement by identifying and adding the most informative new data points via uncertainty estimates. | High data efficiency; targets exploration of rare events and transition states. | Often relies on costly ab initio MD for initial sampling; can be complex to set up. | Focused on "missing" data; size depends on system complexity. |

| Foundational Models [21] | Large-scale pre-training on diverse datasets (e.g., from the Materials Project), followed by fine-tuning. | Broad foundational knowledge; good starting point for many systems. | Dataset bias towards stable crystals; may perform poorly on out-of-distribution configurations. | Very large (>million structures); requires fine-tuning data. |

| Random Structure Searching (RSS) [21] [22] | Stochastic generation of random atomic configurations, which are relaxed and used for training. | High structural diversity; discovers unknown stable/metastable phases; no prior structural knowledge needed. | Computationally expensive without smart sampling; can be inefficient. | Can be large; depends on search space breadth. |

| Automated Frameworks (autoplex) [21] [22] | Unifies RSS with iterative MLIP fitting in an automated workflow, using improved potentials to drive further searches. | Automation reduces human effort; systematic exploration; leverages efficient GAP-RSS protocol [22]. | Relatively new ecosystem; may require HPC and workflow management expertise. | Grows iteratively; often requires 1000s of single-point DFT calculations [21]. |

Performance Benchmarking: autoplex in Action

To objectively evaluate its performance, the autoplex framework has been tested on several material systems, with results quantified against ab initio reference data. The core metric is the energy prediction error (Root Mean Square Error, RMSE) for key crystalline phases as the training dataset grows iteratively.

Elemental and Binary Oxide Systems

Table 2: Performance of autoplex-GAP Models on Test Structures [21] [22]

The following table shows the final energy prediction errors (RMSE in meV/atom) for different material systems after iterative training with autoplex.

| Material System | Structure / Phase | Final RMSE (meV/atom) | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (Elemental) | Diamond-type | ~0.1 | High-symmetry phases are learned rapidly. |

| β-tin-type | ~1-10 | Higher-pressure phase is more challenging than diamond-type [21]. | |

| oS24 | ~10 | Metastable, low-symmetry phase requires more training data [21]. | |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Rutile, Anatase | < 1 - 10 | Common polymorphs are accurately captured. |

| TiO₂-B | ~20-24 | Complex bronze-type polymorph is "distinctly more difficult to learn" [21]. | |

| Full Ti-O System | Ti₂O, TiO, Ti₂O₃, Ti₃O₅ | < 0.6 - 23 | A single model can describe multiple stoichiometries accurately. |

| (Trained on TiO₂ only) | > 100 - >1000 | Critical Finding: Models trained on a single stoichiometry fail catastrophically for others [21]. |

The data shows that autoplex can achieve high accuracy (errors on the order of 0.01 eV/atom, or 10 meV/atom, which is a common accuracy target) for a wide range of structures [21]. The learning curves demonstrate that while simple phases are captured quickly, complex or metastable phases require more iterations and a larger volume of training data [21]. A key conclusion from the benchmarking is the importance of compositional diversity in the training set; a model trained only on TiO₂ is not transferable to other titanium oxide stoichiometries [21].

Benchmarking Against Other MLIP Formalities

While the search results do not provide a direct, quantitative comparison between autoplex-generated potentials and other modern MLIP architectures (like NequIP [15] or DeePMD [15]), the performance of the underlying Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) framework used in the autoplex demonstrations is state-of-the-art. For reference, DeePMD has been shown to achieve energy mean absolute errors (MAE) below 1 meV/atom and force MAE under 20 meV/Å on large-scale water simulations [15]. The errors reported for autoplex-GAP models in Table 2 are comparable, falling within a few meV/atom for most stable phases.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Understanding the experimental methodology is crucial for reproducing and validating the presented benchmarks.

The autoplex Automated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the automated, iterative workflow implemented by the autoplex framework.

Diagram 1: The autoplex Automated Workflow. This iterative loop combines Random Structure Searching (RSS) with MLIP fitting. Key to its efficiency is the use of the MLIP for computationally cheap structure relaxations, with only selective single-point DFT calculations used for validation and training [21] [22]. This minimizes the number of expensive DFT calculations, which is the computational bottleneck.

Key Methodological Details

- Software Interoperability: Autoplex is designed as a modular framework that interfaces with existing computational infrastructure. It builds upon the atomate2 workflow system, which underpins the Materials Project, ensuring compatibility with a vast ecosystem of materials science codes [21] [22].

- MLIP Formalism: The demonstrated autoplex workflows primarily use the Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) framework [21]. GAP is based on Gaussian process regression and is known for its data efficiency, making it suitable for an iterative exploration-fitting loop where the dataset grows gradually [21] [22]. The framework is also designed to accommodate other MLIP architectures.

- DFT Reference Calculations: The "ground truth" data for training and validation comes from DFT. The benchmark studies for silicon and titanium oxides used specific exchange-correlation functionals consistent with earlier work to ensure valid comparisons [21]. The protocol requires only DFT single-point evaluations on relaxed structures, not full ab initio molecular dynamics, which is a significant computational saving [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details the key computational "reagents" and tools that constitute the core of automated PES exploration.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Automated MLIP Development

| Item / Solution | Function in the Workflow | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| autoplex Software | The core automation framework that manages the iterative workflow of structure generation, DFT task submission, and MLIP fitting [21]. | The primary subject of this guide; enables reproducible and high-throughput MLIP development. |

| GAP (Gaussian Approximation Potential) | A data-efficient machine learning interatomic potential formalism based on Gaussian process regression [21] [22]. | Used as the primary MLIP engine in the demonstrated autoplex workflows. Its performance is benchmarked. |

| atomate2 Workflow Manager | A widely adopted Python library for designing, executing, and managing computational materials science workflows [21]. | Provides the robust automation infrastructure upon which autoplex is built, ensuring reliability and scalability. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Code | Software (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) that provides the quantum-mechanical reference data (energies, forces) for training the MLIPs. | Serves as the "gold standard" for benchmarking the accuracy of the resulting MLIPs. |

| Random Structure Searching (RSS) | A computational algorithm for generating random, chemically sensible atomic configurations to broadly explore the PES [21]. | The primary exploration engine within autoplex, responsible for generating structural diversity in the training set. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A computing environment with thousands of CPUs/GPUs necessary for running thousands of DFT calculations and MLIP training jobs. | An essential resource for executing the automated, high-throughput workflows in a practical timeframe. |

The benchmarking data and comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrate that automated frameworks like autoplex significantly accelerate and systematize the development of machine-learned interatomic potentials. By unifying random structure searching with iterative model fitting, autoplex addresses the critical data bottleneck in MLIP creation, enabling the generation of robust potentials from scratch with minimal manual intervention [21].

The key takeaways for researchers are:

- Performance: autoplex-generated GAP models achieve quantum-mechanical accuracy (errors ~1-10 meV/atom) for diverse systems, from simple elements to complex binary oxides [21] [22].

- Critical Consideration: Training data must encompass the full range of compositions and phases of interest; a model trained on a single stoichiometry lacks transferability [21].

- Automation Advantage: The automated, high-throughput nature of frameworks like autoplex represents the future of MLIP development, lowering the barrier to entry and making high-quality atomistic simulations more accessible to the wider research community [21].

As the field progresses, future developments will likely focus on integrating a wider variety of MLIP architectures, improving exploration strategies for surfaces and reaction pathways, and further tightening the integration with foundational model fine-tuning. For now, autoplex stands as a powerful and validated tool for any research team aiming to build reliable MLIPs for computational materials science and drug development.

Leveraging Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) for Broad-Spectrum Materials Modeling

Universal Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (uMLIPs) represent a transformative advancement in computational materials science, offering a powerful surrogate for expensive ab initio methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT). These models are trained on vast datasets of quantum mechanical calculations and can predict energies, forces, and stresses with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost [15]. The development of uMLIPs has shifted the paradigm from system-specific potentials to foundational models capable of handling diverse chemistries and crystal structures across the periodic table [23] [6]. This guide provides a comprehensive benchmark of state-of-the-art uMLIPs, evaluating their performance across critical materials properties to inform model selection for broad-spectrum materials modeling.

Comparative Performance of uMLIPs Across Material Properties

The predictive accuracy of uMLIPs varies significantly across different physical properties and conditions. Below, we synthesize recent benchmarking studies to compare model performance on phonon, elastic, and high-pressure properties.

Performance on Phonon Properties

Phonon properties, derived from the second derivatives of the potential energy surface, are critical for understanding vibrational and thermal behavior. A benchmark study evaluated seven uMLIPs on approximately 10,000 ab initio phonon calculations [23].

Table 1: Performance of uMLIPs on Phonon and Elastic Properties

| Model | Phonon Benchmark Performance [23] | Elastic Properties MAE (GPa) [24] | Key Architectural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet | Moderate accuracy | Not top performer (data NA) | Pioneering universal model with three-body interactions [23] |

| CHGNet | Lower accuracy | ~40 (Bulk Modulus) | Small architecture (~400k parameters), includes charge information [23] [24] |

| MACE-MP-0 | High accuracy | ~15 (Bulk Modulus) | Uses atomic cluster expansion; high data efficiency [23] [24] |

| SevenNet-0 | High accuracy | ~10 (Bulk Modulus) | Built on NequIP; focuses on parallelizing message-passing [23] [24] |

| MatterSim-v1 | High reliability (0.10% failure) | ~15 (Bulk Modulus) | Based on M3GNet, uses active learning for broad chemical space sampling [23] [24] |

| ORB | Lower accuracy (high failure rate) | Data NA | Combines smooth atomic positions with graph network simulator [23] |

| eqV2-M | Lower accuracy (highest failure rate) | Data NA | Uses equivariant transformers for higher-order representations [23] |

The study revealed that while some models like MACE-MP-0 and SevenNet-0 achieved high accuracy, others exhibited substantial inaccuracies, even if they performed well on energy and force predictions near equilibrium [23]. Models that predicted forces as a separate output, rather than as exact derivatives of the energy (e.g., ORB and eqV2-M), showed significantly higher failure rates in geometry relaxation, which precedes phonon calculation [23].

Performance on Elastic Properties

Elastic constants are highly sensitive to the curvature of the potential energy surface, presenting a strict test for uMLIPs. A systematic benchmark of four models on nearly 11,000 elastically stable materials from the Materials Project database revealed clear performance differences [24].

Table 2: Comprehensive Elastic Property Benchmark (Mean Absolute Error) [24]

| Model | Bulk Modulus (GPa) | Shear Modulus (GPa) | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Poisson's Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SevenNet | ~10 | ~20 | ~25 | ~0.03 |

| MACE | ~15 | ~25 | ~35 | ~0.04 |

| MatterSim | ~15 | ~30 | ~40 | ~0.05 |

| CHGNet | ~40 | ~50 | ~60 | ~0.07 |

The benchmark established that SevenNet achieved the highest overall accuracy, while MACE and MatterSim offered a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. CHGNet performed less effectively for elastic property prediction in this evaluation [24].

Performance Under Extreme Conditions

The performance of uMLIPs can degrade under conditions not well-represented in their training data, such as extreme pressures. A study benchmarking uMLIPs from 0 to 150 GPa found that predictive accuracy deteriorated considerably with increasing pressure [6]. For instance, the energy MAE for M3GNet increased from 0.42 meV/atom at 0 GPa to 1.39 meV/atom at 150 GPa. This decline was attributed to a fundamental limitation in the training data, which lacks sufficient high-pressure configurations [6]. The study also demonstrated that targeted fine-tuning on high-pressure data could easily restore model robustness, highlighting a key strategy for adapting uMLIPs to specialized regimes [6].

Experimental Protocols for uMLIP Benchmarking

Understanding the methodologies behind these benchmarks is crucial for interpreting results and designing new validation experiments.

Workflow for Phonon and Elastic Property Calculation

The process for calculating second-order properties like phonons and elastic constants is methodologically similar and involves a strict sequence of steps. The following diagram outlines the core workflow used in benchmark studies [23] [24].

The critical first step is geometry relaxation, where the atomic positions and cell vectors are optimized until the forces on all atoms are minimized below a threshold (e.g., 0.005 eV/Å) [23]. Failure at this stage, which was higher for models like ORB and eqV2-M, prevents further analysis [23]. The subsequent evaluation of forces and stresses, followed by the calculation of second derivatives, tests the model's ability to capture the subtle curvature of the potential energy surface [23] [24].

uMLIP Performance Decision Logic

With varying model performance, selecting the appropriate uMLIP depends on the specific application and material conditions. The logic below synthesizes findings from multiple benchmarks to guide researchers [23] [6] [24].

Successful application of uMLIPs relies on a ecosystem of software, data, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for uMLIP Applications

| Resource Category | Example | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | MDR Phonon Database [23] | Provides ~10,000 phonon calculations for validating predictive performance on vibrational properties. |

| High-Pressure Data | Extended Alexandria Database [6] | Contains 32 million single-point DFT calculations under pressure (0-150 GPa) for fine-tuning and benchmarking. |

| Elastic Properties Data | Materials Project [24] | Source of DFT-calculated elastic constants for over 10,000 structures, enabling systematic validation. |

| Software & Frameworks | DeePMD-kit [15] | Open-source implementation for training and running MLIPs, supporting large-scale molecular dynamics. |

| Universal MLIP Models | MACE, SevenNet, MatterSim [23] [24] | Pre-trained, ready-to-use foundation models for broad materials discovery and property prediction. |

Benchmarking studies conclusively demonstrate that uMLIP performance is highly property-dependent. While uMLIPs have reached a level of maturity where they can reliably predict energies and forces for many systems near equilibrium, their accuracy on second-order properties like phonons and elastic constants varies significantly between architectures [23] [24]. Furthermore, these models face challenges in extrapolating to regimes underrepresented in training data, such as high-pressure environments [6]. The emerging paradigm is that while universal models like MACE, MatterSim, and SevenNet offer a powerful starting point for broad-spectrum materials modeling, targeted fine-tuning on specific classes of materials or conditions remains a crucial strategy for achieving high-fidelity results in specialized applications. This combination of foundational models and focused refinement is poised to significantly accelerate the discovery and design of complex materials.

The accurate simulation of biomolecular systems is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and drug design. Understanding protein-ligand interactions and solvation effects at an atomic level is critical for predicting binding affinity, a key parameter in therapeutic development. For decades, a trade-off has existed between the chemical accuracy of quantum mechanical methods and the computational tractability of classical force fields. The emergence of machine learning potentials (MLPs) promises to bridge this gap, offering a route to perform large-scale, complex simulations with ab initio fidelity. This guide benchmarks the performance of these novel MLPs against traditional ab initio and classical methods, providing a comparative analysis grounded in recent experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance Benchmarking: MLPs vs. Traditional Methods

Accuracy in Energy and Force Prediction

The primary metric for evaluating any potential is its accuracy in predicting energies and atomic forces compared to high-level ab initio calculations. The following table summarizes the performance of various methods across different biological systems.

Table 1: Accuracy Benchmarks for Energy and Force Predictions

| Method | System Type | Energy MAE/RMSE | Force MAE/RMSE | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI2BMD (MLP) | Proteins (175-13,728 atoms) | 0.038 kcal mol⁻¹ per atom (avg.) | 1.056 - 1.974 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ (avg.) | DFT [25] |

| MM Force Field (Classical) | Proteins (175-13,728 atoms) | 0.214 kcal mol⁻¹ per atom (avg.) | 8.094 - 8.392 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ (avg.) | DFT [25] |

| MTP/GM-NN (MLP) | Ta-V-Cr-W Alloys | A few meV/atom (RMSE) | ~0.15 eV/Å (RMSE) | DFT [26] |

| g-xTB (Semiempirical) | Protein-Ligand (PLA15) | Mean Abs. % Error: 6.1% | N/A | DLPNO-CCSD(T) [27] |

| UMA-m (MLP) | Protein-Ligand (PLA15) | Mean Abs. % Error: 9.57% | N/A | DLPNO-CCSD(T) [27] |

| AIMNet2 (MLP) | Protein-Ligand (PLA15) | Mean Abs. % Error: 22.05-27.42% | N/A | DLPNO-CCSD(T) [27] |

The data demonstrates that modern MLPs like AI2BMD can surpass classical force fields by approximately an order of magnitude in accuracy for both energy and force calculations in proteins [25]. Furthermore, specialized MLPs like MTP and GM-NN show remarkably low errors even for chemically complex systems, achieving force RMSEs competitive with ab initio quality [26]. In protein-ligand binding affinity prediction, the semiempirical method g-xTB currently leads in accuracy on the PLA15 benchmark, with MLPs like UMA-m showing promising but slightly less accurate results [27].

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

While accuracy is crucial, the practical utility of a method is determined by its computational cost and ability to simulate large systems over relevant timescales.

Table 2: Computational Efficiency and Scaling of Simulation Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Simulation Speed | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Ab Initio) | O(N³) | 21 min/step (281 atoms) | High intrinsic accuracy [25] |

| AI2BMD (MLP) | Near-linear | 0.072 s/step (281 atoms) | >10,000x speedup vs. DFT [25] |

| ML-MTS/RPC | N/A | 100x acceleration vs. direct PIMD | Efficient nuclear quantum effects [28] |

| Classical MD | O(N) to O(N²) | Fastest for large systems | High throughput, well-established [25] |

| g-xTB | Semiempirical | Fast, CPU-efficient | Good accuracy/speed balance [27] |

The efficiency gains of MLPs are transformative. AI2BMD reduces the computational time for a simulation step from 21 minutes (DFT) to 0.072 seconds for a 281-atom system, an acceleration of over four orders of magnitude, while maintaining ab initio accuracy [25]. This makes it feasible to simulate proteins with over 10,000 atoms, a task prohibitive for routine DFT calculation [25]. Hybrid approaches like ML-MTS/RPC (Machine Learning-Multiple Time Stepping/Ring-Polymer Contraction) further leverage MLPs to accelerate path integral simulations, crucial for capturing nuclear quantum effects, by two orders of magnitude [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow for MLP Validation

A rigorous, multi-stage protocol is essential for validating the performance of MLPs against established computational and experimental benchmarks.

Diagram 1: MLP Benchmarking and Validation Workflow