Beyond DFT: A Practical Guide to GW-BSE for Accurate Excited-State Calculations in Materials and Molecules

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter equation (GW-BSE), a state-of-the-art many-body perturbation theory approach for predicting excited-state properties.

Beyond DFT: A Practical Guide to GW-BSE for Accurate Excited-State Calculations in Materials and Molecules

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter equation (GW-BSE), a state-of-the-art many-body perturbation theory approach for predicting excited-state properties. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we cover foundational theory, practical methodologies, troubleshooting for accuracy, and rigorous validation against established quantum chemistry methods. The guide explores applications from molecular crystals to drug-like compounds, highlighting how GW-BSE overcomes limitations of density functional theory (DFT) for charged and neutral excitations, including band gaps, optical spectra, and excitonic effects, with direct implications for photovoltaics, OLEDs, and biomedical research.

Understanding GW-BSE: The Theoretical Foundation for Excited-State Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has long served as the workhorse of computational materials science and quantum chemistry, providing insights into electronic structures and material properties at relatively low computational cost. However, as a ground-state theory, DFT suffers from fundamental limitations in accurately describing excited electronic states and quasiparticle energies, which are essential for understanding optical properties, electronic excitations, and transport phenomena. The most recognized shortcoming is the systematic underestimation of band gaps in semiconductors and insulators—by up to a factor of 2 for common materials like Si, Ge, GaAs, SiO₂, and HfO₂ [1]. This band gap problem stems from DFT's inherent inability to properly capture electron-electron interactions, particularly in localized states and strongly correlated systems [1].

The GW approximation, named for the notation used for the electron propagator (G) and screened Coulomb interaction (W), emerges from Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT) as a powerful approach to overcome these limitations. By calculating the electron self-energy through a rigorous diagrammatic expansion, GW provides a more physically accurate description of electron correlation effects, enabling precise predictions of ionization potentials, electron affinities, and excited state properties that align closely with experimental measurements [1] [2]. For researchers investigating excited states, particularly in the context of optical spectroscopy and electronic device behavior, bridging the gap between DFT and GW represents an essential step toward predictive computational design.

Theoretical Foundation: From DFT to theGWApproximation

The Fundamental Limitations of Standard DFT

While DFT successfully describes ground-state properties of many materials, its approximations for exchange and correlation lead to significant errors in excited-state properties. The local density approximation (LDA) and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals typically yield band gaps that are 30-50% smaller than experimental values [2]. For instance, in monolayer MoS₂—a promising transition metal dichalcogenide for electronic and optoelectronic applications—standard DFT functionals like PBE severely underestimate the band gap, necessitating empirical corrections such as the Hubbard U parameter or hybrid functionals for even qualitatively correct results [3].

These limitations extend beyond simple band gap underestimation. DFT provides an incomplete picture of band alignments between different compounds, fails to describe Auger processes, and cannot capture excitonic effects that dominate optical spectra in low-dimensional materials [1]. These shortcomings present critical barriers to the computational design of materials for photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, and advanced electronic devices.

TheGWFormalism: A Many-Body Perturbation Theory Approach

The GW approximation implements the first-order term in Hedin's expansion of the electron self-energy (Σ) in terms of the screened Coulomb interaction (W) [1]. In this approach, the self-energy is calculated as the product of the one-electron Green's function (G) and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W), giving the method its name. The GW self-energy corrects the DFT eigenvalues through a more physically rigorous treatment of electron correlation and screening effects.

The fundamental equation for calculating quasiparticle energies in the GW approximation is:

$$ \epsiloni^{QP} = \epsiloni^{KS} + Zi \langle \phii^{KS} | \Sigma(\epsiloni^{KS}) - V{xc}^{KS} | \phi_i^{KS} \rangle $$

where $\epsiloni^{QP}$ represents the quasiparticle energy, $\epsiloni^{KS}$ is the Kohn-Sham eigenvalue, $Zi$ is the renormalization factor, $\Sigma$ is the *GW* self-energy, and $V{xc}^{KS}$ is the DFT exchange-correlation potential [2]. This equation illustrates how GW provides a perturbative correction to DFT eigenvalues, effectively bridging the gap between the approximate Kohn-Sham system and the true many-body electronic structure.

Table: Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for Band Gap Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Band Gap Accuracy | Computational Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/GGA | DFT with local/semi-local XC | Severely underestimated (30-50%) | Low | Band gap problem, no excitonic effects |

| Hybrid Functionals | Mix of DFT and Hartree-Fock exchange | Improved but empirical | Medium | Parameter dependence, limited transferability |

| Gâ‚€Wâ‚€@LDA | One-shot GW on LDA starting point | Moderate improvement | High | Starting point dependence |

| Gâ‚€Wâ‚€@PBE | One-shot GW on PBE starting point | Good improvement | High | Starting point dependence |

| QPGâ‚€Wâ‚€ | Full-frequency Gâ‚€Wâ‚€ | Very good | Very High | Computational expense |

| QSGW | Quasiparticle self-consistent GW | Excellent but ~15% overestimated | Very High | Systematic overestimation |

| QSGWÌ‚ | QSGW with vertex corrections | State-of-the-art | Extremely High | Prohibitive for large systems |

Computational Protocols and Methodological Approaches

1GWMethod Flavors and Implementation Choices

The GW approximation encompasses several distinct methodological approaches that represent different trade-offs between computational cost and physical accuracy:

Gâ‚€Wâ‚€: This "one-shot" approach calculates quasiparticle corrections using a single iteration based on a DFT starting point. It is computationally efficient but exhibits notable starting-point dependence. When implemented with the plasmon-pole approximation (PPA) for the frequency dependence of dielectric screening, Gâ‚€Wâ‚€ offers only marginal improvement over the best DFT functionals [2].

QPG₀W₀: This full-frequency quasiparticle G₀W₀ method replaces the PPA with numerical integration of the exact frequency dependence of dielectric screening, dramatically improving predictive accuracy—almost matching the accuracy of the more sophisticated QSGŴ approach [2].

QSGW: The quasiparticle self-consistent GW method constructs a static, Hermitian potential from the energy-dependent self-energy and solves the resulting effective Kohn-Sham equations iteratively. This approach eliminates starting-point bias but systematically overestimates experimental band gaps by approximately 15% [2].

QSGŴ: This state-of-the-art approach incorporates vertex corrections into the screened Coulomb interaction (W), effectively eliminating the systematic overestimation found in QSGW and producing band gaps of exceptional accuracy—sufficient to identify questionable experimental measurements [2].

Workflow forGWCalculations: From DFT to Bethe-Salpeter Equation

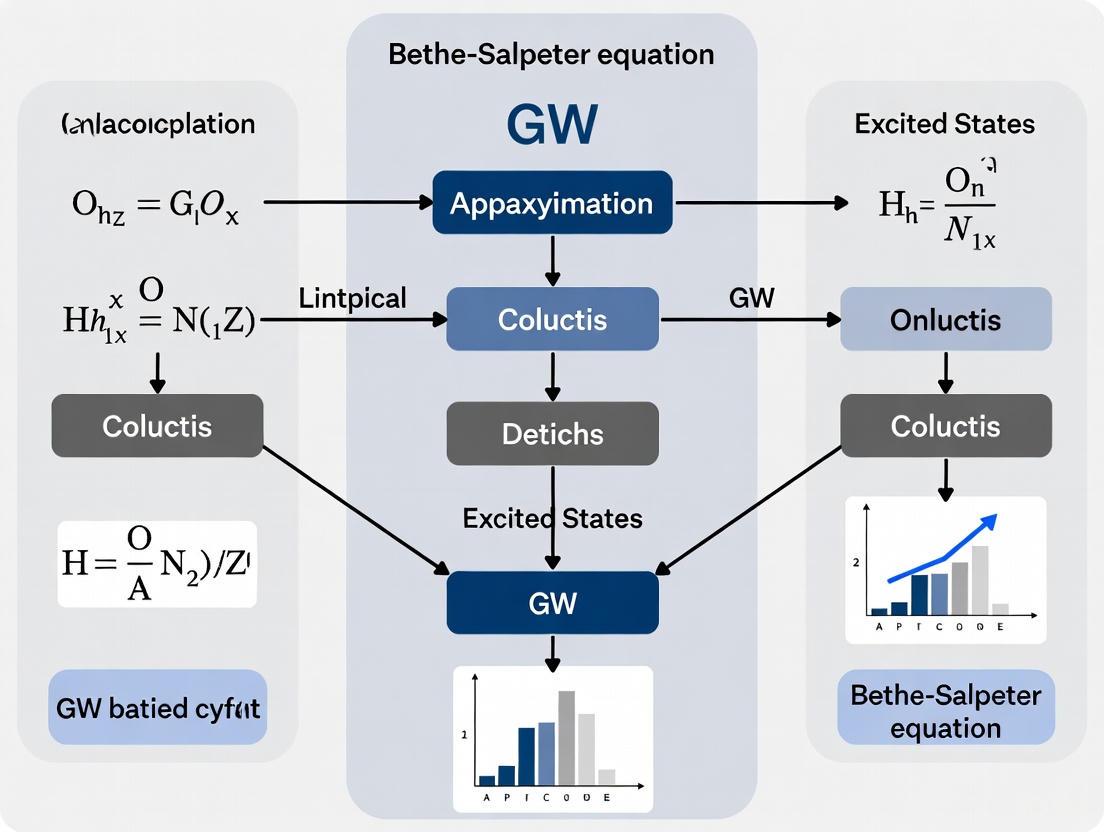

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for advanced electronic structure calculations, spanning from DFT fundamentals to the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter equation for excited states:

Diagram Title: Computational Workflow from DFT to GW and BSE

AdvancedGWImplementation for Large-Scale Systems

Recent breakthroughs in GW implementations have dramatically expanded the scope of systems accessible to first-principles simulation. The QuaTrEx package demonstrates the capability to perform GW calculations on systems containing up to 84,480 atoms, achieving exascale computational performance (1.15 Eflop/s) on supercomputers like Alps and Frontier [1]. These advances rely on several key innovations:

- Spatial domain decomposition: Novel distributed linear solvers enable computation of selected entries of the Green's function and screened Coulomb interaction matrices [1]

- Memory management optimization: Exploitation of symmetry in physical quantities and memoization techniques reduce memory footprint [1]

- High-performance computing: Python-orchestrated code running on up to 37,600 GPUs enables simulation of realistic nanoribbon field-effect transistors (NRFETs) with dimensions comparable to experimental devices [1]

Performance Assessment and Benchmarking

Quantitative Benchmarking ofGWMethods vs. DFT

Recent systematic benchmarking of 472 non-magnetic materials provides comprehensive insights into the performance of various GW approaches compared to state-of-the-art DFT functionals [2]. The results demonstrate a clear hierarchy of accuracy and computational expense:

Table: Accuracy Comparison of Electronic Structure Methods for 472 Materials

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (eV) | Systematic Error Trend | Computational Cost Relative to DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | ~1.0 (estimated) | Severe underestimation | 1x |

| PBE | ~0.8 (estimated) | Severe underestimation | 1x |

| HSE06 | 0.38 | Moderate underestimation | 10-100x |

| mBJ | 0.36 | Moderate underestimation | 1-2x |

| Gâ‚€Wâ‚€@LDA-PPA | 0.34 | Slight underestimation | 100-1,000x |

| Gâ‚€Wâ‚€@PBE-PPA | 0.32 | Slight underestimation | 100-1,000x |

| QPGâ‚€Wâ‚€ | 0.19 | Slight underestimation | 1,000-5,000x |

| QSGW | 0.24 | ~15% overestimation | 5,000-10,000x |

| QSGWÌ‚ | 0.14 | Minimal systematic error | 10,000-20,000x |

These results indicate that while basic G₀W₀ with plasmon-pole approximation offers only modest improvements over the best DFT functionals (mBJ and HSE06), more sophisticated GW implementations deliver substantially enhanced accuracy—with QSGŴ producing band gaps so accurate they can reliably identify questionable experimental measurements [2].

Case Study: MoSâ‚‚ Band Gap Correction

The application of GW methods to transition metal dichalcogenides provides a compelling case study in overcoming DFT limitations. For bulk MoSâ‚‚, standard DFT functionals (PBE, LDA) significantly underestimate the band gap, while hybrid functionals like HSE06 with empirical Hubbard U corrections yield improved but still imperfect results [3]. GW calculations successfully predict the quasiparticle band gap without empirical parameters, demonstrating the method's fundamental physical accuracy. This capability is particularly valuable for predicting properties of novel two-dimensional materials before experimental characterization.

Table: Computational Tools for GW and Bethe-Salpeter Equation Calculations

| Software Package | Methodology Implementation | Basis Set | Key Features | Target Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QuaTrEx [1] | NEGF+scGW | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWF) | 84,480 atoms, exascale performance | Nanoscale devices, quantum transport |

| YAMBO [4] | Gâ‚€Wâ‚€, BSE | Plane Waves | GPU acceleration, workflow automation | Optical spectra, excited states |

| BerkeleyGW [1] | Gâ‚€Wâ‚€ | Plane Waves | High performance on GPUs | Nanostructures, 2D materials |

| Questaal [2] | QPGâ‚€Wâ‚€, QSGW, QSGWÌ‚ | Linear Muffin-Tin Orbital (LMTO) | All-electron, full-frequency integration | Accurate band gaps, benchmark studies |

| VASP [1] | Gâ‚€Wâ‚€ | Projector Augmented Waves (PAW) | User-friendly, widely adopted | General materials science |

| NanoGW [1] | Gâ‚€Wâ‚€ | Real-Space Grids (RSG) | Efficient for medium systems | Nanostructures, molecules |

Application Notes:GWfor Excited States and the Bethe-Salpeter Equation

Integration with the Bethe-Salpeter Equation

For predicting optical properties and excited states, the GW approximation is typically coupled with the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) to account for electron-hole interactions (excitonic effects). This GW+BSE approach has proven highly successful for calculating optical absorption spectra, exciton binding energies, and excited-state properties across a wide range of materials [5]. The combination effectively addresses both aspects of DFT's limitations: GW corrects the single-particle band structure, while BSE incorporates the electron-hole correlations that dominate optical excitations.

Recent advances in GW+BSE methodology have revealed systematic variations in the accuracy of different classes of excited states. Calculations on the Quest-3 database of organic molecules show that excitation energies for ππ states are generally more accurate than those for nπ and nR (Rydberg) states, reflecting differences in self-energy corrections between nonbonding and π bonding states [5]. Specifically, nitrogen or oxygen lone pair states require larger self-energy corrections due to strong orbital relaxation in the localized hole state, while π states exhibit smaller corrections.

Protocol for AccurateGW+BSE Calculations

- DFT Starting Point: Perform well-converged DFT calculation using PBE or LDA functional with high-quality basis set

- * convergence Tests*: Systematically converge basis set size, k-point sampling, and dielectric matrix energy cutoff

- GW Calculation:

- Compute dielectric function with full-frequency integration (avoid plasmon-pole approximation when possible)

- Calculate screened Coulomb interaction W

- Compute GW self-energy and quasiparticle corrections

- Consider self-consistent GW for highest accuracy

- BSE Solution:

- Construct electron-hole interaction kernel from GW results

- Solve Bethe-Salpeter Equation for excitonic states

- Calculate optical absorption spectrum

- Validation: Compare with available experimental data (optical spectra, photoemission)

The development of efficient, accurate, and scalable GW implementations represents an ongoing frontier in computational materials science and quantum chemistry. Recent achievements in exascale GW computing demonstrate the potential for simulating realistically sized nanoscale devices with first-principles accuracy [1]. Meanwhile, systematic benchmarking establishes that advanced GW flavors—particularly full-frequency QPG₀W₀ and QSGŴ—deliver superior accuracy for band gap prediction compared to any DFT functional [2].

For researchers investigating excited states, the GW approximation and its extension to the Bethe-Salpeter Equation provide a powerful framework that fundamentally addresses the limitations of standard DFT. While the computational cost remains substantial, the systematic improvability and first-principles nature of these methods make them invaluable for predictive materials design, particularly when combined with emerging machine learning approaches that can leverage high-accuracy GW data for broader materials screening [2].

As computational resources continue to grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, the accessibility and application scope of GW-based methods will undoubtedly expand, further solidifying their role as essential tools for understanding and designing the electronic and optical properties of complex materials and molecular systems.

In quantum mechanics, the concept of a quasiparticle is fundamental to understanding the behavior of electrons in materials. Whereas density-functional theory (DFT) provides a powerful framework for calculating ground-state properties, its one-particle eigenvalues lack formal justification for describing excitation energies, leading to the well-known band-gap problem where DFT typically underestimates experimental band gaps by 30-50% or more [6]. A quasiparticle represents an electron plus its screening cloud—the surrounding charge cloud of other electrons that screens the strong Coulomb forces. This description allows the response of strongly interacting particles to be described in terms of weakly interacting quasiparticles [6]. Mathematically, quasiparticles are described through the single-particle Green's function G(r,t,r',t'), also called a propagator, which describes the probability amplitude for an electron to propagate from position r' at time t' to position r at time t [6].

The quasiparticle energy corresponds to the energy required to add or remove an electron from a many-body system and is observable through photoemission experiments [6]. Within the GW approximation, the quasiparticle energies are obtained by solving a non-linear equation that corrects the Kohn-Sham eigenvalues from DFT calculations. The standard quasiparticle equation reads:

[E{n \mathbf{k}}^{\mathrm{QP}} = \epsilon{n \mathbf{k}} + Z{n \mathbf{k}} \cdot \mathrm{Re}\left[\Sigma{n \mathbf{k}}(\epsilon{n \mathbf{k}}) + \epsilon^{\mathrm{EXX}}{n \mathbf{k}} - V^{\mathrm{XC}}_{n \mathbf{k}}\right]]

where (E{n \mathbf{k}}^{\mathrm{QP}}) is the quasiparticle energy, (\epsilon{n \mathbf{k}}) is the Kohn-Sham eigenvalue, (\Sigma{n \mathbf{k}}) is the GW self-energy, (\epsilon^{\mathrm{EXX}}{n \mathbf{k}}) is the exact exchange contribution, (V^{\mathrm{XC}}{n \mathbf{k}}) is the DFT exchange-correlation potential, and (Z{n \mathbf{k}}) is the renormalization factor that accounts for the energy dependence of the self-energy [7].

Mathematical Foundations of the Self-Energy

The GW Self-Energy Operator

The self-energy operator (Σ) is a non-Hermitian, energy-dependent, and non-local operator that describes exchange and correlation effects beyond the Hartree approximation [6]. In the GW approximation, the self-energy is approximated as the product of the single-particle Green's function (G) and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W), giving rise to the name "GW" [6]. The self-energy can be separated into two components: a static, gap-opening term called the exchange self-energy (Σˣ), and an energy-dependent, usually gap-closing term called the correlation self-energy (Σᶜ) [8].

The full GW self-energy in the plane-wave representation is given by:

[ \Sigma{n \mathbf{k}}(\omega) = \frac{1}{\Omega} \sum{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'} \sum{\mathbf{q}}^{1. \text{BZ}} \sum{m}^{\text{all}} \frac{i}{2 \pi} \int{-\infty}^\infty d\omega' W{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega') \cdot \frac{\rho^{n \mathbf{k}}{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}}(\mathbf{G}) \rho^{n \mathbf{k}*}{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}}(\mathbf{G}')}{\omega + \omega' - \epsilon{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}} + i \eta \text{sgn}(\epsilon{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}} - \mu)} ]

where (W{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega)) are matrix elements of the screened Coulomb interaction, (\rho^{n \mathbf{k}}{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}}(\mathbf{G}) \equiv \langle n \mathbf{k} | e^{i(\mathbf{q} + \mathbf{G})\mathbf{r}} | m \mathbf{k} !-! \mathbf{q} \rangle) are the pair density matrix elements, (m) runs over all bands (occupied and unoccupied), (\mathbf{q}) covers differences between all k-points in the first Brillouin zone, (\Omega) is the volume, and (\eta) is an artificial broadening parameter [7].

Renormalization Factor and Quasiparticle Strength

The renormalization factor (Z_{n \mathbf{k}}) quantifies the quasiparticle strength and is defined as:

[ Z{n \mathbf{k}} = \left(1 - \text{Re}\langle n \mathbf{k}| \frac{\partial}{\partial\omega} \Sigma(\omega){|\omega = \epsilon_{n \mathbf{k}}}| n \mathbf{k}\rangle\right)^{-1} ]

This factor accounts for the energy dependence of the self-energy and is crucial for solving the quasiparticle equation through linearization [7]. Typical values of (Z_{n \mathbf{k}}) range from 0.7 to 0.9 for most materials, indicating that quasiparticles have finite lifetimes and are not perfect single-particle excitations.

Table 1: Key Components of the GW Self-Energy

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | Computational Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange Self-Energy (Σˣ) | (\Sigma^x = i G \cdot v) | Static, gap-opening term | Treated similarly to Hartree-Fock exchange |

| Correlation Self-Energy (Σᶜ) | (\Sigma^c = i G \cdot W^p) | Dynamical, gap-closing term | Requires evaluation of screened interaction W |

| Renormalization Factor (Z) | (Z = (1 - \partial\Sigma/\partial\omega)^{-1}) | Quasiparticle strength and lifetime | Calculated through energy derivatives |

| Screened Interaction (W) | (W = v \cdot \varepsilon^{-1}) | Dynamically screened Coulomb potential | Computed via dielectric matrix inversion |

Dynamical Screening and Dielectric Response

The Screened Coulomb Interaction

The dynamically screened Coulomb interaction W is a central quantity in GW calculations that captures how the bare Coulomb interaction is modified by the electronic environment. It is computed from the dielectric matrix in the Random Phase Approximation (RPA):

[ W{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega) = \frac{4 \pi}{|\mathbf{q} + \mathbf{G}|} \left( (\varepsilon^{\mathrm{RPA}})^{-1}{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega) - \delta_{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'} \right) \frac{1}{|\mathbf{q} + \mathbf{G}'|} ]

where (\varepsilon^{\mathrm{RPA}}_{\mathbf{G} \mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega)) is the RPA dielectric function, and (\mathbf{G}) and (\mathbf{G}') are reciprocal lattice vectors [7]. The dielectric function describes how the electron cloud screens an external perturbation, and its inversion yields the effective interaction between electrons.

Treatment of Coulomb Divergence

A critical technical issue in GW calculations is the handling of the Coulomb divergence that occurs at small q vectors. The head of the screened potential ((\mathbf{G} = \mathbf{G}' = 0)) diverges as (1/q^2) for (\mathbf{q} \rightarrow 0), but this divergence is removed for infinitesimally fine k-point sampling since the integration measure (d^3\mathbf{q}) cancels the (1/q^2) divergence [7]. For the (\mathbf{q} = 0) term, specialized analytical treatments are employed:

[ W{\mathbf{00}}(\mathbf{q}=0, \omega) = \frac{2\Omega}{\pi} \left(\frac{6\pi^2}{\Omega}\right)^{1/3} \varepsilon^{-1}{\mathbf{00}}(\mathbf{q} \rightarrow 0, \omega) ]

for the head, and similarly for the wings [7]. This treatment is only relevant for terms with (n = m), as otherwise the pair density matrix elements vanish.

Computational Approaches for Frequency Integration

Plasmon Pole Approximation

The Plasmon Pole Approximation (PPA) is a widely used method to model the frequency dependence of the dielectric function with a single peak at the main plasmon frequency. It offers significant computational advantages by requiring calculation of the dielectric matrix at only two frequencies while providing an analytical expression for the frequency integral of the correlation self-energy [7] [9]. Within PPA, the dielectric function is modeled as:

[ \varepsilon^{-1}{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}, \omega) = R{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}) \left(\frac{1}{\omega - \tilde{\omega}{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}) + i\eta} - \frac{1}{\omega + \tilde{\omega}{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q}) - i\eta}\right) ]

The parameters (R{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q})) and (\tilde{\omega}{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}(\mathbf{q})) are determined by fitting to the full dielectric function at (\omega = 0) and (\omega = i E0), where (E0) is a fitting parameter typically set to 1 Hartree [7]. While computationally efficient, PPA can introduce errors of about 0.1-0.3 eV compared to full-frequency treatments [10].

Full-Frequency and Multipole Methods

For higher accuracy, full-frequency approaches numerically integrate the frequency dependence without approximations. The frequency integration is performed on a user-defined grid for positive values only, exploiting the symmetry (W(\omega') = W(-\omega')) [7]:

[ \int{-\infty}^\infty d\omega' \frac{W(\omega')}{\omega + \omega' - \epsilon{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}} \pm i \eta} = \int{0}^\infty d\omega' W(\omega') \left(\frac{1}{\omega + \omega' - \epsilon{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}} \pm i \eta} + \frac{1}{\omega - \omega' - \epsilon_{m \mathbf{k} - \mathbf{q}} \pm i \eta}\right) ]

The Multipole Approximation (MPA) represents an intermediate approach, providing full-frequency accuracy at a lower computational cost than numerical full-frequency integration [11]. MPA uses a sampling in the complex frequency plane and can be thought of as a generalization of PPA with multiple poles. Key parameters include ETStpsXm (number of frequency points, equivalent to twice the number of poles), EnRngeXm (energy range along the real frequency axis), and ImRngeXm (energy range along the imaginary axis) [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Frequency Integration Methods in GW Calculations

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | Key Parameters | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmon Pole Approximation (PPA) | Low | Moderate (0.1-0.3 eV error) | PPAPntXp (imaginary energy) |

Initial studies, large systems |

| Multipole Approximation (MPA) | Medium | High | ETStpsXm, EnRngeXm, ImRngeXm |

Balanced accuracy and efficiency |

| Full-Frequency Real Axis (FF-RA) | High | Very High | ETStpsXd, DmRngeXd |

Benchmark calculations |

| Full-Frequency with Double Excitations | Very High | Highest | Density fitting basis sets | Systems with important double excitations |

Connection to the Bethe-Salpeter Equation

The GW formalism provides the foundation for calculating excited states through the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE), which builds upon the quasiparticle energies and screened interaction to describe neutral excitations [12] [10]. The BSE is an exact relation between the two-particle Green's function and the one-particle self-energy, and when using the GW approximation to the self-energy, it provides neutral excitation energies and spectra [10].

The BSE modifies the GW energy gaps due to electron-hole interactions, with the primary difference compared to time-dependent Hartree-Fock theory being that the electron-hole attraction in the BSE is screened [10]. In terms of spatial molecular orbitals, the BSE is a frequency-dependent eigenvalue problem:

[ A(\Omega)X = \Omega X ]

where

[ A{ia,jb}(\Omega) = (Ea - Ei)\delta{ij}\delta{ab} + \kappa(ia|jb) - (ab|ij) - K{abij}^{(p)}(\Omega) ]

Here, (Ep) are GW quasiparticle energies, ((pq|rs)) are electron repulsion integrals, (\kappa = 2) for a singlet excited state and 0 for a triplet, and (K{abij}^{(p)}(\Omega)) is the polarizable part of the direct electron-hole interaction [10].

A significant advancement in BSE methodology is the reformulation of the full-frequency dynamical BSE as a frequency-independent eigenvalue problem in an expanded space of single and double excitations [10] [13]. This approach reduces the computational scaling from O(Nâ¶) to O(Nâµ) when combined with iterative eigensolvers and density fitting approximations, while also providing direct access to excited states with dominant double excitation character that are completely absent in the statically screened BSE [10].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Workflows

Standard GW Calculation Protocol

A typical GW calculation follows a well-defined workflow, as implemented in codes like Yambo [8] [9]:

DFT Ground State Calculation: Perform a self-consistent DFT calculation to obtain Kohn-Sham wavefunctions and eigenvalues. For materials with weak interlayer interactions, include van der Waals corrections. Export the wavefunctions with

calc.write('groundstate.gpw', 'all')in GPAW or similar commands in other codes [7].Initialization: Convert the DFT output to a format suitable for GW calculations using utilities like

p2yin Yambo [8]. Initialize the GW calculation, which determines G-vector shells and k- and q-point grids based on the DFT calculation.Exchange Self-Energy: Calculate the static exchange self-energy (Σˣ) using Hartree-Fock theory. Converge parameters such as

EXXRLvcs(exchange reciprocal lattice vectors) [9].Dielectric Function: Compute the dielectric matrix within the RPA. Key parameters to converge include

NGsBlkXp(response block size),BndsRnXp(polarization function bands), andLongDrXp(electric field direction) [9].Correlation Self-Energy: Evaluate the correlation part of the self-energy (Σᶜ) using either PPA, MPA, or full-frequency methods. For PPA, set

PPAPntXpto an appropriate value (typically around 1 Ha) [9].Quasiparticle Equation: Solve the quasiparticle equation using a Newton solver (

DysSolver="n") or other methods. Specify the bands and k-points of interest usingQPkrange[9].Convergence Testing: Systematically test convergence with respect to k-point sampling, number of bands (

GbndRnge), energy cutoff (NGsBlkXp), and other parameters [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete GW calculation process:

Advanced BSE Protocol with Dynamical Screening

For high-accuracy excited-state calculations including dynamical screening effects:

GW Preparation: Perform a well-converged GW calculation to obtain quasiparticle energies and the screened interaction W [10].

BSE Matrix Construction: Build the BSE matrix in the space of single excitations, including the dynamically screened electron-hole interaction [10].

Double Excitation Expansion: Reformulate the frequency-dependent BSE as a frequency-independent problem in an expanded space of single and double excitations [10] [13].

Iterative Diagonalization: Use the Davidson algorithm or similar iterative methods to find the lowest eigenvalues of the expanded BSE matrix. The matrix-vector multiplication is implemented with O(Nâµ) scaling using density fitting [10].

Spectral Analysis: Analyze the resulting eigenvectors to identify states with significant double excitation character, which are completely absent in static screening approximations [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Parameters and Convergence

Successful GW-BSE calculations require careful convergence of several computational parameters. The following table summarizes the essential "research reagents" for GW-BSE calculations:

Table 3: Essential Computational Parameters for GW-BSE Calculations

| Parameter | Symbol/Variable | Physical Meaning | Convergence Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-point Sampling | kmesh |

Brillouin zone integration density | Increase until QP energies change < 0.05 eV |

| Energy Cutoff | NGsBlkXp |

Number of G-vectors in response | Increase until band gap converges |

| Band Number | GbndRnge, BndsRnXp |

Number of bands in self-energy/polarization | Include more unoccupied states until convergence |

| Plasmon Pole Frequency | PPAPntXp |

Imaginary energy for PPA fit | Typical value: 1 Ha (27.21138 eV) |

| Frequency Grid | ETStpsXd, domega0 |

Number of frequency points | Increase until spectral features stabilize |

| Broadening Parameter | eta, GDamping |

Artificial broadening | Use small value (0.1 eV) for convergence study |

| Coulomb Truncation | rim_cut |

Treatment of long-range Coulomb | Essential for 2D systems and surfaces |

| Methyl 15-Hydroxypentadecanoate | Methyl 15-Hydroxypentadecanoate, CAS:76529-42-5, MF:C16H32O3, MW:272.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| DMT-dA(PAc) Phosphoramidite | DMT-dA(PAc) Phosphoramidite|DNA/RNA Synthesis | DMT-dA(PAc) Phosphoramidite is a high-purity building block for oligonucleotide synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The renormalization factor Z must be carefully monitored during calculations, as it affects the quasiparticle energy correction. Typical values should be between 0.7-0.9; values outside this range may indicate convergence issues or problems with the starting wavefunctions [9].

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between key GW approximations and their physical interpretations:

Applications and Case Studies

Fragment-based GW and BSE methods enable excited-state calculations for large molecular systems. Accuracy can be systematically improved by including two-body correction terms, with fragment-based calculations reproducing unfragmented results with relative errors of less than 100 meV [12]. Studies of the 2¹Ag state of butadiene, hexatriene, and octatetraene reveal that GW/BSE overestimates excitation energies by about 1.5-2 eV and significantly underestimates double excitation character [10] [13]. This highlights the importance of dynamical screening and double excitations for accurate prediction of excited states in molecular systems.

Extended Systems: h-BN and MoSâ‚‚

For extended systems like hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) and molybdenum disulfide (MoSâ‚‚), GW calculations provide significantly improved band gaps compared to DFT. In h-BN, typical GW corrections increase the Kohn-Sham band gap by 2-3 eV, bringing it closer to experimental values [9]. For 2D materials like MoSâ‚‚ monolayers, special attention must be paid to Coulomb truncation to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images [8].

The protocol for these systems includes: using a fine k-point grid (e.g., 12×12×1 for 2D materials), converging the number of bands to at least 100-200, using a Coulomb truncation technique for 2D systems, and carefully testing the sensitivity to the dielectric function energy cutoff [8] [9].

The GW approximation provides a powerful framework for describing quasiparticle excitations in materials by incorporating many-body effects through the self-energy operator and dynamical screening. The physics behind GW involves fundamental concepts of quasiparticles, self-energy, and dynamical screening that address the limitations of DFT for excited states. Through various approximations like the plasmon pole model, multipole approximation, or full-frequency integration, GW calculations balance computational efficiency with accuracy.

The connection to the Bethe-Salpeter equation extends this methodology to neutral excitations, enabling prediction of optical spectra and excited-state properties. Recent methodological advances, such as the reformulation of the dynamical BSE as a frequency-independent eigenvalue problem, have improved computational efficiency while providing access to important double excitations. As implementations continue to advance and computational resources grow, GW-BSE methods are becoming increasingly accessible for studying complex materials and molecular systems across physics, chemistry, and materials science.

Theoretical Foundation and Significance

The Bethe-Salpeter equation (BSE) is a fundamental formalism in many-body perturbation theory designed to accurately describe the neutral, optical excitations of materials and molecules. It serves as a critical bridge between single-particle calculations and the experimental observation of optical spectra, which are fundamentally two-particle processes [14]. While approximations like the GW method provide accurate quasiparticle energies for single-particle excitations, they fail to capture the key physics of optical absorption, where an incoming photon creates a correlated electron-hole pair, known as an exciton [14]. The BSE explicitly accounts for this interaction, allowing for the prediction of optical spectra that are in excellent agreement with experimental data, a feat unattainable by independent-particle models [14].

The electron-hole correlation function is the central quantity, obeying a Dyson-like equation—the BSE—that incorporates an electron-hole interaction kernel [14]. This equation can be reformulated as an effective eigenvalue problem. In the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA), which is often employed, the BSE Hamiltonian (H_BSE) for spin-singlet excitations takes the form [14]:

H_BSE = (A B; B A)

where the A block contains the resonant transitions, and the B block contains the coupling to anti-resonant transitions. Within the TDA, the off-diagonal B blocks are neglected, simplifying the Hamiltonian. The matrix elements in the basis of electron-hole pairs (vck, v'c'k') are [14]:

A_{vck, v'c'k'} = (E_{ck} - E_{vk}) δ_{vv'}δ_{cc'}δ_{kk'} + 2 v_{vck, v'c'k'} - W_{vck, v'c'k'}

Here, (E_ck - E_vk) is the energy difference between the quasi-electron and quasi-hole states from a prior GW calculation. The term v represents the repulsive bare exchange Coulomb interaction, while W is the attractive screened direct Coulomb interaction. The delicate balance between these two terms is responsible for forming bound excitonic states [14]. The eigenvalues of this Hamiltonian yield the excitonic excitation energies, and the eigenvectors represent the excitonic wavefunctions.

Table 1: Key Components of the Bethe-Salpeter Equation Hamiltonian.

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Role |

|---|---|---|

| Quasiparticle Energy | (E_ck - E_vk) |

Energy of a non-interacting electron-hole pair [14]. |

| Exchange Kernel | 2 v_{vck, v'c'k'} |

Repulsive, short-range interaction stemming from the bare Coulomb potential [14]. |

| Direct Kernel | - W_{vck, v'c'k'} |

Attractive, screened electron-hole interaction responsible for binding excitons [14]. |

Computational Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for BSE Calculations in Periodic Codes

Implementing the BSE in modern computational codes like BerkeleyGW or VASP follows a structured, multi-step workflow. The following diagram outlines the key stages, from obtaining the ground state to calculating the final optical spectrum:

The specific computational steps, as implemented in codes like VASP and BerkeleyGW, are detailed below [14] [15]:

Ground-State Calculation:

- Objective: Generate a self-consistent mean-field starting point.

- Protocol: Perform a Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculation with a plane-wave basis set to obtain the Kohn-Sham orbitals and energies. This step produces the

WAVECARfile in VASP [15].

GW Quasiparticle Calculation:

- Objective: Compute quantitatively accurate single-particle energies to form the diagonal part of the BSE Hamiltonian.

- Protocol: Run a one-shot (Gâ‚€Wâ‚€) or self-consistent GW calculation using the DFT wavefunctions as a starting point. This step yields the quasiparticle energies (Eck, Evk) and, crucially, the static screened Coulomb interaction

W(ω→0), which is written to files likeWxxxx.tmporWFULLxxxx.tmp[15].

BSE Kernel Construction:

- Objective: Build the electron-hole interaction matrix.

- Protocol: Using the quasiparticle energies and the screened Coulomb interaction

W, the BSE kernel is constructed. This involves calculating the matrix elements of the direct (W) and exchange (v) kernels. In BerkeleyGW, this is done in thekernelexecutable, which outputs absematfile [14]. The number of occupied (NBANDSO) and unoccupied (NBANDSV) bands included in the construction of the Hamiltonian must be carefully chosen to ensure convergence [15].

BSE Hamiltonian Solution:

- Objective: Solve for the excitonic eigenstates.

- Protocol: The BSE Hamiltonian is diagonalized to obtain excitonic energies and wavefunctions. This can be done via full diagonalization for small systems, or more efficiently using iterative methods like the Davidson or Lanczos-Haydock algorithms for larger systems [14] [16]. In BerkeleyGW, this is handled by the

absorptionexecutable [14].

Optical Spectrum Calculation:

- Objective: Compute the frequency-dependent dielectric function including excitonic effects.

- Protocol: The macroscopic dielectric function

ε_M(ω)is constructed from the solved excitonic states and their corresponding oscillator strengths. The imaginary part,Im[ε_M(ω)], is directly proportional to the optical absorption spectrum [14].

Advanced Methodologies and Convergence

Several advanced techniques have been developed to address the significant computational cost of BSE calculations, particularly concerning k-point convergence and dynamical screening.

- k-point Convergence: The excitonic wavefunction can be spatially extended, requiring very dense k-point grids for convergence. This is a major computational bottleneck. The double k-grid method tackles this by using a coarse k-grid for the expensive kernel calculation and a fine k-grid to expand the excitonic states, all within an iterative solver framework, dramatically improving efficiency [16].

- Dynamical Screening: The standard BSE uses a statically screened interaction

W(ω=0). The full-frequency dynamical BSE includes the frequency dependence ofW, which is computationally demanding but can be reformulated as a larger frequency-independent eigenvalue problem in an expanded space of single and double excitations, reducing the scaling and providing access to states with double excitation character [10]. - Energy-Specific Calculations: For high-lying excitations (e.g., core-level X-ray absorption spectra), conventional diagonalization is inefficient. The energy-specific BSE approach modifies the Davidson algorithm to target specific energy windows, making such calculations feasible [17].

Table 2: Comparison of BSE Solvers and Their Applications.

| Solver Method | Computational Scaling | Key Features | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Diagonalization | O(N³) | Provides all excitonic states and wavefunctions; becomes prohibitive for large systems [16]. | Small molecules and systems with few electron-hole pairs. |

| Iterative (Davidson) | O(N²) per iteration | Efficient for calculating a limited number of low-lying excited states; widely used in molecular codes [17]. | Valence and core excitations in molecules and nanoclusters [17]. |

| Lanczos-Haydock | O(N²) per iteration | Avoids explicit storage of the Hamiltonian; ideal for sparse systems; yields spectrum but not all individual states [16]. | Large periodic systems for obtaining full optical spectra. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Successful BSE calculations rely on a set of well-defined "research reagents" or computational components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BSE Calculations.

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quasiparticle Energies | Forms the diagonal of the BSE Hamiltonian; provides the single-particle energy gap [14]. | Input from a prior GW calculation (e.g., G0W0 or evGW) [18]. |

| Screened Coulomb Interaction (W) | The direct kernel mediating the attractive electron-hole interaction; accounts for dielectric screening [14] [15]. | Calculated within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA) in a GW step; stored in files like WFULLxxxx.tmp in VASP [15]. |

| Static Dielectric Matrix | Used to build the screened Coulomb interaction W [14]. |

Computed in the epsilon step of BerkeleyGW; required input files are epsmat and eps0mat [14]. |

| Mean-Field Wavefunctions | Serve as the basis set for constructing the electron-hole pair space [14]. | Kohn-Sham orbitals from DFT (e.g., WAVECAR in VASP, WFN_co in BerkeleyGW) [14] [15]. |

| Model Dielectric Function | Approximates the screened Coulomb potential without an explicit GW calculation, reducing cost [15]. | In VASP, activated with LMODELHF and parameterized with AEXX and HFSCREEN [15]. |

| 4-Nitro-3-(trifluoromethyl)aniline | 4-Nitro-3-(trifluoromethyl)aniline, CAS:393-11-3, MF:C7H5F3N2O2, MW:206.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N,N'-Dinitrosopiperazine | 1,4-Dinitrosopiperazine | High Purity Reagent | High-purity 1,4-Dinitrosopiperazine for nitrosamine & alkylating agent research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter equation (GW-BSE) framework has emerged as a cornerstone of modern first-principles computational physics and chemistry for investigating excited states in materials and molecules. This many-body perturbation theory approach provides accurate descriptions of quasiparticle excitations and electron-hole interactions, which are fundamental to interpreting experimental spectroscopic data. While traditional applications focused on predicting optical absorption spectra, recent methodological advances have significantly expanded its experimental connections, particularly in the realm of photoemission spectroscopy. This protocol details the practical application of GW-BSE for bridging theoretical computations with experimental observables, enabling researchers to decipher complex excited-state phenomena in molecular systems and solid-state materials.

Computational Framework and Theoretical Foundations

The GW-BSE Methodology

The GW-BSE approach is a two-step procedure for computing neutral excitations. Initially, the GW approximation corrects the underestimation of band gaps in Density Functional Theory (DFT) by computing quasiparticle energies through electron self-energy corrections. Subsequently, the Bethe-Salpeter equation solves the effective two-particle Hamiltonian to describe interacting electron-hole pairs (excitons), which dominate the optical response in many systems.

The excitonic Hamiltonian in the Tamm-Dancoff approximation can be expressed as:

[H{exciton} = (Ec - Ev) + K{direct} + K_{exchange}]

where (Ec) and (Ev) are the quasiparticle energies of conduction and valence states, respectively, while (K{direct}) and (K{exchange}) represent the electron-hole interaction kernels. The accuracy of this method rivals sophisticated quantum chemistry wavefunction approaches while offering superior scalability for larger systems [19].

Connecting to Experimental Observables

The GW-BSE framework provides direct connections to multiple experimental techniques:

- Optical absorption spectra from the imaginary part of the dielectric function

- Photoemission spectra through one-particle spectral functions

- Exciton dispersion relations via center-of-mass momentum dependence

- Structural relaxation patterns in excited states through force calculations

Advanced Application: Exciton Photoemission Orbital Tomography (exPOT)

Theoretical Framework

The recently developed exciton photoemission orbital tomography (exPOT) framework provides a direct bridge between GW-BSE calculations and momentum-resolved photoemission spectroscopy [20]. This approach simulates and interprets time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy experiments by explicitly incorporating probe pulse effects on photoemission matrix elements and capturing correlated electron-hole behavior within many-body perturbation theory.

The method formulates the photoemission signal using Fourier-transformed single-particle Bloch functions, weighted by BSE eigenvectors to reflect the entangled many-body character of electron-hole correlations. Crucially, it extends to excitons with finite center-of-mass momentum, enabling the study of optically dark excitons prevalent in transition metal dichalcogenides and other layered materials [20].

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Ground State Calculation

- Perform DFT calculation with appropriate exchange-correlation functional

- Use planewave basis sets with optimized pseudopotentials

- Ensure sufficient k-point sampling for Brillouin zone integration

Step 2: Quasiparticle Energy Correction

- Compute GW corrections to DFT band structure

- Implement efficient algorithms to handle empty state summations

- Utilize plasmon-pole models or full-frequency integration

Step 3: BSE Exciton Calculation

- Construct electron-hole Hamiltonian using GW quasiparticle energies

- Include both direct and exchange electron-hole interactions

- Solve eigenvalue problem for exciton states and wavefunctions

Step 4: exPOT Simulation

- Implement photoemission matrix elements using exciton wavefunctions

- Incorporate pump pulse polarization effects

- Calculate photoelectron angular distributions for comparison with experiment

Case Study: Hexagonal Boron Nitride

Application to monolayer hexagonal boron nitride reveals that photoelectron angular distributions depend on both the exciton character and the pump pulse polarization. The exPOT framework successfully predicts momentum-space signatures of correlated electron-hole wave functions, providing insights into normally invisible momentum-dark excitons [20].

Calculating Excited-State Forces and Structural Relaxation

Theoretical Approach

The calculation of atomic forces in excited states enables the prediction of structural relaxation following photoexcitation. The force acting on atom (I) is defined as:

[FI = -\frac{\partial E{exc}}{\partial R_I}]

where (E{exc}) is the excited state energy and (RI) is the atomic coordinate. Two primary methods implement this within GW-BSE:

- Finite Difference Approach: Computes forces through atomic displacements requiring (6N) BSE calculations for (N) atoms [19]

- Hellmann-Feynman Theorem: Calculates forces as expectation values of the derivative of the excitonic Hamiltonian with respect to atomic displacement [19]

The Hellmann-Feynman approach offers significant computational advantages, particularly for systems with multiple excited states or complex potential energy surfaces where level crossing complicates finite difference methods.

Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Ground State Preparation

- Optimize ground state geometry using DFT

- Select appropriate exchange-correlation functional (e.g., PBE)

- Use sufficient planewave cutoff energy (e.g., 70 Ry)

- Place molecules in sufficiently large simulation cells to prevent spurious interactions

Step 2: GW-BSE Calculation

- Compute quasiparticle energies for relevant occupied and unoccupied states

- Construct and diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian

- Identify excited states of interest through symmetry analysis

Step 3: Force Calculation via Hellmann-Feynman Theorem

- Implement derivative of excitonic Hamiltonian using finite differences

- Apply suitable projectors to handle displaced atomic configurations

- Use moderate atomic displacements (e.g., Δλ = 0.1 Bohr)

- Compute forces as expectation values for targeted excited states

Step 4: Geometry Optimization

- Utilize optimization algorithms (steepest descent or BFGS)

- Implement convergence criteria for forces (e.g., < 10â»Â² Ry/Bohr)

- Monitor excited state energy during optimization

- Account for possible symmetry breaking in excited states

Validation Case Studies

Table 1: Validation of GW-BSE Force Methodology for Carbon Monoxide [19]

| State | Bond Length (GW-BSE) | Bond Length (Reference) | Force Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| X¹Σ⺠| ~1.13 Å | ~1.13 Å (Expt) | N/A |

| A¹Π| ~1.23 Å | ~1.24 Å (Expt) | < 0.01 Ry/Bohr |

| I¹Σ⻠| ~1.33 Å | ~1.34 Å (Theory) | < 0.01 Ry/Bohr |

| D¹Δ | ~1.29 Å | ~1.30 Å (Theory) | < 0.01 Ry/Bohr |

Table 2: Formaldehyde Excited State Structural Changes [19]

| Parameter | Ground State (Câ‚‚áµ¥) | Excited State (Câ‚›) | Notable Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-O bond | ~1.21 Ã… | ~1.32 Ã… | Significant elongation |

| C-H bond | ~1.10 Ã… | ~1.11 Ã… | Minor change |

| H-C-H angle | ~116° | ~115° | Slight narrowing |

| Molecular planarity | Planar | Non-planar | Symmetry breaking |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GW-BSE Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT ground state calculation | Provides plane-wave pseudopotential framework |

| GWL Code | GW-BSE implementation | Avoids empty state sums; enables large systems |

| Plane-wave Basis Sets | Electronic wavefunction representation | 70 Ry cutoff typically sufficient for molecules |

| Norm-conserving Pseudopotentials | Ion-electron interaction modeling | Balance between accuracy and computational cost |

| Optimal Basis Set | Polarizability operator representation | ~50 elements sufficient for molecular systems |

| BSE Exciton Solver | Electron-hole pair calculation | Tamm-Dancoff approximation typically employed |

| Hellmann-Feynman Module | Excited-state force computation | Requires finite difference of excitonic Hamiltonian |

| exPOT Framework | Photoemission tomography simulation | Connects BSE to momentum-resolved photoemission |

The integration of GW-BSE methodology with advanced experimental techniques through frameworks like exPOT and excited-state force calculations represents a powerful paradigm for materials characterization. These protocols enable researchers to not only predict spectroscopic signatures but also understand the structural consequences of electronic excitation. As computational resources expand and methodologies refine, the bridge between many-body theory and experimental observables will continue to strengthen, providing unprecedented insights into the excited-state properties of complex materials and molecular systems.

Implementing GW-BSE: Methodologies, Workflows, and Real-World Applications

The accurate prediction of excited-state properties is a central challenge in computational materials science and chemistry, with critical applications in photovoltaics, optoelectronics, and photocatalysis. While Density Functional Theory (DFT) has proven highly successful for modeling ground-state properties, it suffers from a well-documented bandgap underestimation problem and limited capacity for describing excitonic effects. Within the context of broader research on excited states, many-body perturbation theory within the GW approximation and the Bethe-Salpeter equation (BSE) has emerged as a leading methodology for calculating quantitatively accurate quasiparticle (QP) energies and optical spectra, directly comparable with experimental observations [21]. This framework rigorously addresses electron-electron interactions beyond DFT and incorporates crucial electron-hole correlations that dominate the optical response of many materials. The implementation of this multi-step computational workflow, however, presents significant challenges, including the management of numerous interdependent convergence parameters and substantial computational costs. This protocol details a robust, systematic procedure for performing GW-BSE calculations, enabling researchers to reliably predict excited-state properties.

Theoretical Foundation: The GW-BSE Framework

The GW-BSE approach is a first-principles method based on many-body perturbation theory. Its power lies in systematically correcting the deficiencies of standard DFT.

The GW Approximation: The GW method provides a rigorous framework for calculating quasiparticle (QP) energies, which represent the energies associated with adding or removing an electron from a many-electron system. It achieves this by approximating the electron self-energy (Σ) as the product of the one-particle Green's function (G) and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W). The QP energies are obtained by solving a QP equation that corrects the Kohn-Sham eigenvalues from DFT [21]. This correction successfully overcomes DFT's bandgap underestimation for a wide range of semiconductors and insulators without requiring empirical parameters [22].

The Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE): While GW yields accurate bandgaps, the optical spectra calculated within the resulting independent-particle picture often remain inadequate. The BSE formalism addresses this by solving an effective two-particle equation for the electron-hole pair (exciton). It explicitly includes the electron-hole interaction, which is essential for accurately describing bound exciton states and producing optical absorption spectra that match experiments, including peak positions and oscillator strengths [21]. The BSE Hamiltonian is built upon the GW-corrected electronic structure.

The following diagram illustrates the logical structure and data flow of this multi-step process.

Computational Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow

This section provides a detailed, sequential guide for performing GW-BSE calculations using plane-wave codes like VASP [23]. The procedure assumes a converged DFT ground state as the starting point.

Step 1: Ground-State DFT Calculation

Objective: To obtain a well-converged ground-state charge density and wavefunctions, which serve as the foundational input for all subsequent steps.

- System:

Material Name - Key INCAR Parameters:

PREC = Normal(Balances accuracy and computational speed)ENCUT = [Value](Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff; typically set to 1.3 × the maximumENMAXfound in thePOTCARfiles)ISMEAR = 0(Gaussian smearing method; use for insulators)SIGMA = 0.01(Small smearing width for insulators)KPAR = 2(Divides k-points over 2 compute nodes for parallelization)EDIFF = 1.E-8(Tight convergence criterion for electronic steps)

- Output Files:

WAVECAR,CHGCAR

Step 2: Calculation with a Large Number of Bands

Objective: To generate a large set of empty states (unoccupied bands), which are essential for constructing the polarizability and self-energy in the GW calculation.

- System:

Material Name - Key INCAR Parameters:

ALGO = Exact(Performs exact diagonalization to compute many bands)NELM = 1(Runs a single step; no self-consistent iteration needed)NBANDS = [Large Number](Critical parameter; must be significantly larger than the number of occupied bands. A common starting point is the number of atoms in the system multiplied by 50-100 [21])LOPTICS = .TRUE.(Calculates frequency-dependent dielectric matrix)LPEAD = .TRUE.(Computes derivatives of the wavefunctions)OMEGAMAX = 40(Maximum energy for dielectric calculation, in eV)

- Output Files: Updated

WAVECAR(with many bands),WAVEDER

Step 3: GW Calculation

Objective: To compute the quasiparticle energies and the screened Coulomb interaction (W).

- System:

Material Name - Key INCAR Parameters:

ALGO = GW0(Performs single-shot G0W0 calculation. For higher accuracy, useALGO = EVGW0withNELMGW > 1for partially self-consistent calculations)ENCUTGW = [Value](Cutoff energy for the response function; often set toENCUT/2to fullENCUTfrom Step 1 to balance cost and accuracy [24])NOMEGA = 50(Number of frequency points for screening; must be converged)NBANDSGW = [Value](Number of bands used in the GW self-energy calculation; typically includes all occupied bands plus a subset of empty bands from Step 2)LWAVE = .TRUE.(Writes wavefunctions to file)

- Output Files:

Wxxxx.tmp(screened Coulomb interaction), UpdatedWAVECAR

Step 4: BSE Calculation

Objective: To solve the Bethe-Salpeter equation and obtain the optical absorption spectrum, including excitonic effects.

- System:

Material Name - Key INCAR Parameters:

ALGO = BSE(Activates the BSE calculation)ANTIRES = 0(Uses the Tamm-Dancoff approximation, a common simplification)NBANDSO = [Value](Number of occupied bands included in the excitonic Hamiltonian)NBANDSV = [Value](Number of virtual (unoccupied) bands included in the excitonic Hamiltonian)OMEGAMAX = 20(Maximum energy for the output spectrum, in eV)

- Output Files:

vasprun.xml(contains the dielectric function and exciton energies/oscillator strengths)

Critical Convergence Tests

GW-BSE calculations are highly sensitive to several computational parameters. A systematic convergence study is mandatory for obtaining physically meaningful results. The table below summarizes the key parameters and convergence strategies.

Table 1: Key Convergence Parameters and Strategies for GW-BSE Calculations

| Parameter | Description | Convergence Strategy | Target Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBANDS | Number of empty states for GW [23] | Test series: NBANDS = N_occ × (2, 4, 6, 8, 10) |

Band gap change < 0.05 eV |

| ENCUTGW | Cutoff for response function [24] | Test series: ENCUTGW = (2/3, 3/4, 1, 5/4) × ENCUT |

QP energy change < 0.1 eV |

| NOMEGA | Frequency points for screening [23] | Test series: NOMEGA = 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 |

QP energy change < 0.05 eV |

| k-point grid | Sampling of the Brillouin Zone [21] | Systematically increase k-point density from DFT-converged mesh | Band gap change < 0.1 eV |

| NBANDSO/V | Bands in BSE Hamiltonian [23] | Increase until absorption spectrum features stabilize | Visual inspection of spectrum |

A recent study analyzing over 7000 GW calculations recommends a 'cheap first, expensive later' coordinate search for efficiently converging the interdependent parameters ENCUTGW and NOMEGA, and confirms the practical independence of the k-point grid from these parameters, which can dramatically speed up the convergence workflow [24].

Essential Computational Tools and Databases

The complexity of the GW-BSE workflow has spurred the development of automated software packages and databases to facilitate high-throughput computations.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GW-BSE Calculations

| Tool/Solution | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [21] [23] | Software Package | First-principles electronic structure calculation. | Core engine for performing DFT, GW, and BSE calculations. |

| pyGWBSE [21] [22] | Python Workflow | Automation of multi-step GW-BSE computations. | Manages parameter convergence, job submission, and data storage. |

| Wannier90 [21] | Software Tool | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWF). | Generates accurate QP bandstructures with reduced cost. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO [19] | Software Suite | Open-source first-principles modeling. | Alternative platform for GW-BSE (e.g., via the GWL code). |

The pyGWBSE package is particularly notable for achieving complete automation of the entire workflow, including convergence tests, and is integrated with Wannier90 for generating QP bandstructures. It also supports the creation of databases of metadata and results, which are invaluable for large-scale materials screening and machine learning [21] [22].

Advanced Applications and Extensions

The foundational GW-BSE workflow is being extended to tackle increasingly complex scientific problems.

- Calculation of Excited-State Forces: A recent implementation allows for the calculation of atomic forces in excited states via the Hellmann-Feynman theorem, enabling geometry relaxation in excited states. This is crucial for predicting phenomena like photoluminescence and photo-induced structural changes [19].

- Embedding Techniques (GW/BSE-in-DFT): For large or complex systems like defects in solids, a cluster-in-periodic embedding method can be used. This approach treats a small region of interest at the GW/BSE level while embedding it in a larger environment treated with less expensive DFT, significantly reducing computational cost while maintaining accuracy [25].

- Magnetic Fields and Molecular Systems: The GW/BSE method has been adapted to handle molecules in strong, finite magnetic fields using complex-valued London orbitals, enabling the study of novel magneto-optical phenomena [26].

The step-by-step computational workflow from DFT to GW to BSE provides a powerful and predictive framework for investigating the excited-state properties of materials and molecules. While computationally demanding, a rigorous approach involving careful convergence of key parameters, as outlined in this protocol, is essential for obtaining reliable, quantitatively accurate results. The ongoing development of automated workflows like pyGWBSE and advanced methods for calculating excited-state forces and embedding schemes is making this sophisticated methodology more robust and accessible. This empowers researchers to explore a vast design space for next-generation technological applications in optoelectronics, photovoltaics, and photocatalysis.

The GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) represent advanced computational frameworks in many-body perturbation theory that have become indispensable for predicting excited-state properties and accurate electronic structures of materials. The GW approximation effectively overcomes the fundamental bandgap underestimation problem inherent in standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) by calculating the electron self-energy (Σ) as the product of the one-particle Green's function (G) and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W), expressed as Σ ≈ iGW [21] [27]. This approach provides highly accurate quasiparticle (QP) energies, which are crucial for understanding electronic and transport properties.

Building upon GW-corrected electronic structures, the Bethe-Salpeter Equation introduces the critical effect of electron-hole interactions (excitonic effects) to model optical properties. The BSE formalism operates on a two-particle Hamiltonian and is essential for computing absorption spectra and exciton binding energies that are directly comparable with experimental observations, particularly in semiconductors, insulators, and molecular systems [21] [28]. This GW-BSE framework provides a powerful pathway for investigating materials for photovoltaics, photocatalysis, and optoelectronic applications.

The transition from conventional, isolated GW-BSE calculations to high-throughput computational screening presents significant challenges, including the management of numerous interdependent convergence parameters and substantial computational costs. Automated workflow packages like pyGWBSE are specifically designed to overcome these barriers, enabling the systematic and efficient computation of electronic and optical properties across vast material databases [21]. This automation is pivotal for accelerating the discovery of new materials with tailored excited-state characteristics.

pyGWBSE Workflow Architecture and Components

The pyGWBSE package is an open-source Python-based workflow system designed for high-throughput first-principles calculations within the GW-BSE framework. Its primary design objective is to achieve complete automation of the entire multi-step computation, which includes sophisticated convergence tests for parameters critical for accuracy [21]. The package is constructed upon well-established open-source Python libraries such as pymatgen, Fireworks, and atomate, ensuring robustness and integration with existing materials science computational ecosystems [21].

A central feature of pyGWBSE is its integration with Wannier90, a program for generating maximally-localized Wannier functions (MLWFs). This integration allows for the computationally efficient interpolation of quasiparticle bandstructures, making it feasible to obtain detailed electronic structures at the GW level of theory without prohibitive cost [21]. The workflow is directly interfaced with the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP), a widely used platform for atomic-scale materials modeling that implements the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method [21].

Key Computational Methodologies Integrated

The pyGWBSE workflow seamlessly integrates several computational methodologies to deliver a comprehensive property analysis:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Provides the initial ground-state electronic structure, including bandstructures, orbital-resolved density of states (DOS), effective masses, and the independent-particle dielectric function [21].

- GW Formalism: Computes quasiparticle energies, which can be performed at either the one-shot

G0W0or the more accurate, partially self-consistentGW0level of theory. This step corrects the DFT bandgaps [21]. - Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) Solver: Calculates the frequency-dependent dielectric function

ϵ(ω)that includes electron-hole interactions, yielding optical absorption spectra, exciton energies, and their corresponding oscillator strengths [21].

Table 1: Key Software Components in the pyGWBSE Workflow

| Software Component | Role in Workflow | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Primary First-Principles Engine | Performs DFT, GW, and BSE calculations using the PAW method [21]. |

| Wannier90 | Band Structure Interpolation | Generates Maximally Localized Wannier Functions for efficient QP bandstructure calculation [21]. |

| Fireworks | Workflow Management | Manages job submission, scheduling, and monitoring on supercomputing platforms [21]. |

| pymatgen | Materials Analysis | Provides robust tools for analyzing and manipulating structural and electronic data [21]. |

| MongoDB | Data Storage | Serves as the database for storing computed metadata and material properties [21]. |

Application Notes: High-Throughput Screening for Material Discovery

Target Applications and Properties

The automated high-throughput capabilities of pyGWBSE are poised to revolutionize the discovery and optimization of materials for several cutting-edge technological fields. Key application areas include:

- Ultra-Wide Bandgap Semiconductors: Accurate GW-predicted bandgaps are critical for developing next-generation power electronics and high-frequency devices [21].

- Photovoltaics and Photocatalysis: The BSE-derived optical absorption spectra, which include excitonic effects, are essential for identifying materials with high light-harvesting efficiency for solar cells and water-splitting catalysts [21].

- Optoelectronics and Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs): The framework can predict Auger recombination rates and exciton binding energies, which are key parameters affecting the efficiency of LEDs and lasers [21].

- Drug Discovery and Biomaterials: While more common in materials science, the principles of high-throughput screening of electronic properties are increasingly relevant for understanding biomolecular interactions and photoactive drugs. Computational target prediction tools are becoming standard in drug development pipelines [29] [30].

Benchmarking and Validation

The predictive quality of the GW-BSE method implemented in pyGWBSE has been rigorously benchmarked against experimental data. For instance, GW calculations have been successfully used to compute crucial point defect properties such as charge transition levels and F-center photoluminescence spectra in semiconductors, showing remarkable agreement with experiments [21]. Furthermore, BSE calculations have demonstrated the ability to correct not just the absorption energies but also the oscillator strengths of peaks, which often deviate significantly from experiment when calculated within an independent-particle picture [21].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Quasiparticle Bandgap Screening

This protocol details the steps for automated high-throughput calculation of accurate quasiparticle bandgaps using the pyGWBSE workflow.

1. Workflow Initialization and Input Generation

- Prepare a structured input file or database containing the crystal structures (in POSCAR or CIF format) of all materials to be screened.

- Initialize the pyGWBSE workflow, which will automatically generate all necessary VASP input files (INCAR, KPOINTS, POTCAR) for the initial DFT calculation for each structure [21].

2. Ground-State DFT Calculation

- Execute a DFT calculation to obtain the converged electronic ground state. This typically uses the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional.

- Key parameters to set in the input: plane-wave energy cutoff (ENMAX), k-point mesh for Brillouin Zone sampling, and the number of empty bands (NBANDS) to be included in subsequent GW steps [21].

3. Convergence of Critical GW Parameters

- The workflow automatically launches a series of calculations to converge parameters essential for GW accuracy. This is a core feature of pyGWBSE.

- Number of Bands (NBANDS): Run

G0W0calculations with increasing NBANDS until the QP bandgap energy change is below a threshold (e.g., 0.1 eV) [21]. - Dielectric Screening (Number of PDEP modes): Converge the number of projective dielectric eigenpotential (PDEP) modes used to represent the screened Coulomb interaction

W[21] [31]. - Frequency Grid: Ensure the frequency grid for evaluating

Wis sufficiently dense.

4. G0W0 Quasip Calculation

- Once parameters are converged, perform a full

G0W0calculation on the entire system. This step computes the QP energies via first-order perturbation correction to the Kohn-Sham eigenvalues [21]. - The output includes the QP bandgap and other band edge positions.

5. Data Extraction and Database Storage

- The workflow automatically parses the output files to extract the QP bandgap and other relevant electronic properties.

- The computed data and associated metadata (convergence parameters, computational settings) are stored in a MongoDB database for future querying and analysis [21].

Protocol 2: Bethe-Salpeter Equation for Optical Absorption Spectra

This protocol describes the procedure for computing excitonic properties and optical absorption spectra using the BSE solver within the pyGWBSE framework.

1. Prerequisite: Converged GW Calculation

- A successfully completed and converged

G0W0orGW0calculation (from Protocol 1) is a mandatory prerequisite. The QP energies from this step are used as input for the BSE [21].

2. BSE Convergence and Setup

- The workflow automatically determines the optimal parameters for the BSE calculation.

- k-point Grid: The k-point grid used in the DFT/GW calculation must be sufficiently dense to sample excitonic wavefunctions. A convergence test with respect to k-point density may be required [21].

- Number of Valence and Conduction Bands: A specific number of bands around the Fermi level (valence and conduction) must be included in the BSE Hamiltonian. The workflow tests the convergence of the lowest exciton energy with respect to this number [21].

3. BSE Hamiltonian Construction and Diagonalization

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian, which includes the electron-hole direct interaction (screened by the static dielectric function) and the unscreened exchange interaction [21] [28].

- Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian to obtain the exciton eigenvalues (exciton energies) and eigenvectors (exciton wavefunctions). For large systems, iterative diagonalization techniques are employed [31].

4. Optical Property Calculation

- Compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function

ϵ₂(ω)from the solved exciton states and their oscillator strengths. This gives the optical absorption spectrum [21]. - The real part

ϵâ‚(ω)is obtained via the Kramers-Kronig transformation. - The workflow can also output the binding energy of the lowest bright exciton and the spatial distribution of specific excitonic states.

5. Data Storage and Analysis

- The final optical spectra, exciton energies, oscillator strengths, and other excitonic properties are parsed and stored in the database.

- Results can be directly compared to experimental absorption spectra for validation [21].

Table 2: Key Convergence Parameters in pyGWBSE Protocols

| Parameter | Protocol | Physical Significance | Convergence Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBANDS | GW | Number of unoccupied states used in self-energy | Change in QP bandgap < 0.1 eV [21] |

| N_PDEP | GW/BSE | Modes for screened interaction (W) | Change in QP bandgap / exciton energy < threshold [21] [31] |

| K-point Mesh | DFT/GW/BSE | Sampling density of Brillouin Zone | Change in total energy & bandgap < threshold [21] |

| BSE Bands | BSE | Valence/Conduction bands in exciton Hamiltonian | Lowest exciton energy converged [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for High-Throughput GW-BSE Screening

| Tool/Solution | Function/Description | Role in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| pyGWBSE Python Package | Open-source workflow automation package. | Core engine that orchestrates the entire high-throughput process, from input generation to data storage [21]. |

| VASP Software License | Proprietary first-principles simulation software. | Performs the core DFT, GW, and BSE numerical computations [21]. |

| Wannier90 Code | Program for generating Maximally Localized Wannier Functions. | Enables efficient interpolation of quasiparticle bandstructures, reducing computational cost [21]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Access to supercomputing resources with MPI parallelization. | Provides the necessary computational power to run hundreds of calculations in parallel [21]. |

| MongoDB Database | A NoSQL database system. | Stores structured data and metadata from thousands of calculations for easy retrieval and analysis [21]. |

| Projective Dielectric Eigenpotential (PDEP) Method | Algorithm for low-rank representation of the dielectric matrix. | Accelerates the computation of the screened Coulomb interaction W in GW and BSE [31]. |

| 5-Bromo-2-chloropyrimidine | 5-Bromo-2-chloropyrimidine, CAS:32779-36-5, MF:C4H2BrClN2, MW:193.43 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,4-Dimethoxyphenylboronic acid | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenylboronic acid, CAS:122775-35-3, MF:C8H11BO4, MW:181.98 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |