Beyond Static Nuclei: How the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Powers Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, a foundational pillar in quantum chemistry that enables the computational modeling of molecular systems by separating nuclear and electronic...

Beyond Static Nuclei: How the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Powers Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, a foundational pillar in quantum chemistry that enables the computational modeling of molecular systems by separating nuclear and electronic motions. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the approximation's physical basis and historical significance, detail its critical implementation in methods like QM/MM and DFT for modeling drug-target interactions and reaction mechanisms, and address its limitations and the advanced non-adiabatic methods that move beyond it. Finally, we present a comparative evaluation of its performance against emerging quantum computing approaches and machine learning potentials, synthesizing key takeaways to project its evolving role in targeting undruggable proteins and advancing personalized medicine.

The Quantum Bedrock: Deconstructing the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation for Molecular Systems

The many-body problem in quantum mechanics represents one of the most significant fundamental challenges in modern theoretical chemistry and molecular physics. At its core, this problem stems from the exponential complexity of solving the complete molecular Schrödinger equation for systems containing more than a few interacting particles. The Schrödinger equation serves as the fundamental governing equation for non-relativistic quantum mechanical systems, providing a mathematical framework that determines the wave function and energy states of molecular systems [1]. For molecular systems consisting of N nuclei and M electrons, the full wave function depends on 3(N+M) spatial coordinates, creating a mathematical problem of staggering proportions that becomes computationally intractable for all but the simplest molecular systems [2] [3].

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation, introduced in 1927 by Max Born and J. Robert Oppenheimer, provides the essential theoretical foundation that makes computational quantum chemistry possible by introducing a critical hierarchy in the treatment of nuclear and electronic motions [2]. This approximation recognizes the significant mass disparity between electrons and atomic nuclei, allowing for the separation of their motions and thereby reducing the complexity of the quantum mechanical treatment of molecules. Despite its tremendous utility, this approximation has well-defined limitations and does not fundamentally eliminate the exponential scaling of the many-body problem—it merely makes it computationally manageable for practical applications while acknowledging that the exact solution remains beyond reach for multi-electron systems [2] [4].

Mathematical Foundations of the Molecular Many-Body Problem

The Molecular Schrödinger Equation

The time-independent molecular Schrödinger equation takes the form:

ĤΨ = EΨ

where Ĥ represents the molecular Hamiltonian operator, Ψ denotes the complete molecular wave function, and E corresponds to the total energy of the system. The full Hamiltonian for a molecular system containing multiple nuclei and electrons can be expressed as [2]:

Ĥ = -∑i(ℏ²/2me)∇i² - ∑A(ℏ²/2mA)∇A² - ∑i,A(ZAe²/|ri - RA|) + ∑i>j(e²/|ri - rj|) + ∑B>A(ZAZBe²/|RA - RB|)

This operator includes, in sequential order: the kinetic energy of electrons, the kinetic energy of nuclei, the attractive electron-nucleus Coulomb interactions, the repulsive electron-electron Coulomb interactions, and the repulsive nucleus-nucleus Coulomb interactions. The complexity arises from the coupled nature of these interactions, particularly the electron-electron repulsion terms that create an inseparable many-body problem [2] [5].

The Exponential Scaling Problem

Table: Computational Complexity for Exact Solution of Molecular Schrödinger Equation

| System Size | Number of Variables | Computational Cost | Example System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diatomic molecule (2 nuclei, 2 electrons) | 12 spatial coordinates | ~10³-10⁴ operations | H₂ molecule |

| Small polyatomic (5 nuclei, 10 electrons) | 45 spatial coordinates | ~10¹⁵ operations | CH₄ molecule |

| Medium molecule (20 nuclei, 40 electrons) | 180 spatial coordinates | ~10⁶⁰ operations | Caffeine molecule |

| Small protein (500 nuclei, 1000 electrons) | 4500 spatial coordinates | ~10¹⁵⁰⁰ operations | Insulin fragment |

The computational complexity increases exponentially with system size. For a molecule with N particles, the wave function must be described in a Hilbert space of 3N dimensions. The basis set required to represent the wave function grows exponentially with the number of electrons, making exact diagonalization of the Hamiltonian matrix computationally prohibitive for systems with more than approximately 10-15 electrons [2] [5].

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Foundation and Implementation

Theoretical Basis and Separation of Motions

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation leverages the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei to separate their motions. Since atomic nuclei are thousands of times more massive than electrons (e.g., a proton is approximately 1836 times more massive than an electron), their dynamics occur on vastly different time scales [2] [6]. This temporal separation allows for a two-step approach to solving the molecular quantum mechanics problem:

- Electronic Structure Problem: For fixed nuclear positions {R}, solve the electronic Schrödinger equation:

He(r, R)χ(r, R) = Ee(R)χ(r, R)

where He includes the electronic kinetic energy and all Coulomb interactions, with nuclear positions appearing as parameters rather than dynamic variables [2].

- Nuclear Structure Problem: Using the electronic energy Ee(R) as a potential energy surface, solve the nuclear Schrödinger equation:

[Tn + Ee(R)]ϕ(R) = Eϕ(R)

where Tn represents the nuclear kinetic energy operator [2].

Computational Workflow in Modern Quantum Chemistry

The practical implementation of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation follows a systematic computational workflow that enables the calculation of molecular properties with controlled approximation:

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Studies

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Born-Oppenheimer-Based Molecular Simulations

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Theoretical Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Gaussian-type Orbitals, Slater-type Orbitals, Plane Waves | Represent spatial distribution of electronic orbitals | Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) |

| Electronic Structure Methods | Hartree-Fock, Density Functional Theory, Coupled Cluster | Approximate electron correlation effects | Mean-field theory, Density functional formalism, Wavefunction expansion |

| Potential Energy Surface Scanners | Gaussian, Q-Chem, NWChem | Map electronic energy across nuclear configurations | Born-Oppenheimer approximation with geometry optimization |

| Nuclear Dynamics Codes | MOLPRO, OpenMolcas, FMS90 | Simulate nuclear motion on potential surfaces | Wavepacket propagation, Surface hopping algorithms |

| Non-Adiabatic Coupling Calculators | SHARC, PYXAID, ANT | Compute electronic-nuclear coupling terms | Born-Huang expansion, Time-dependent perturbation theory |

Limitations and Breakdown of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Non-Adiabatic Effects and Vibronic Coupling

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation encounters significant limitations when electronic and nuclear motions become strongly coupled, leading to non-adiabatic effects that cannot be captured within the standard framework [4]. These effects become particularly important when:

- Electronic energy gaps become small or vanish (conical intersections)

- Nuclear velocities approach electronic transition timescales

- Spin-orbit coupling introduces significant interstate mixing

- Light atoms (especially hydrogen) exhibit significant quantum tunneling

Vibronic coupling describes the interaction between electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom that arises when the adiabatic separation assumed in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down [4]. This coupling enables radiationless transitions between electronic states and plays a crucial role in photochemical reactions and spectroscopic phenomena.

The Jahn-Teller and Renner-Teller Effects

Two particularly important manifestations of Born-Oppenheimer breakdown are the Jahn-Teller and Renner-Teller effects:

Jahn-Teller Effect: Occurs in nonlinear molecules with electronically degenerate states (e.g., certain transition metal complexes), leading to spontaneous symmetry breaking and geometric distortion that lifts the degeneracy [4].

Renner-Teller Effect: Applies to linear molecules with degenerate electronic states, resulting in vibronic coupling between electronic and bending vibrational modes that splits potential energy surfaces [4].

Conical Intersections and Avoided Crossings

Conical intersections represent points in nuclear configuration space where two electronic potential energy surfaces become degenerate, creating funnels that facilitate rapid non-adiabatic transitions between electronic states [4]. These intersections play a crucial role in photochemical processes such as vision, photosynthesis, and photostability mechanisms in biological molecules. Avoided crossings occur when electronic states of the same symmetry approach but do not intersect due to coupling terms, leading to regions of strong non-adiabaticity where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation fails [4].

Advanced Methodologies Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics Methods

Table: Computational Methods for Non-Adiabatic Processes

| Method | Theoretical Approach | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Hopping | Stochastic trajectory jumps between surfaces | Computationally efficient for large systems | Inconsistent treatment of quantum coherence |

| Multiple Spawning | Basis set expansion along trajectories | Accurate quantum dynamics | Exponential scaling with system size |

| Ehrenfest Dynamics | Mean-field approach on averaged potential | Continuous electronic evolution | Violates detailed balance principles |

| Density Matrix Propagation | Quantum master equation approaches | Proper treatment of decoherence | High computational cost for many states |

| MCTDH | Multi-configurational time-dependent Hartree | Accurate quantum dynamics for moderate systems | Limited by mode combination restrictions |

Experimental Probes of Non-Adiabatic Phenomena

Modern experimental techniques provide critical validation for theoretical methods addressing Born-Oppenheimer breakdown:

Ultrafast Spectroscopy: Femtosecond and attosecond laser techniques track electronic and vibrational evolution in real-time, revealing non-adiabatic dynamics [4].

Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Measures electronic structure changes during molecular dynamics through kinetic energy distributions of ejected electrons [4].

Coincidence Measurements: Correlate electronic and nuclear motions in dissociation processes using advanced detection systems [4].

Multidimensional Spectroscopy: Reveals coupling between electronic and vibrational states through coherent multi-pulse experiments [4].

Computational Strategies for the Many-Body Problem

Hierarchical Approximation Methods

The computational intractability of the exact many-body problem has led to the development of hierarchical approximation methods that systematically approach the exact solution while maintaining computational feasibility:

Emerging Approaches: Machine Learning and Quantum Computing

Recent advances in computational technology have introduced novel approaches to the molecular many-body problem:

Machine Learning-Augmented Strategies: Neural network potentials trained on high-level quantum chemistry calculations enable accurate molecular dynamics simulations at significantly reduced computational cost [3].

Quantum Computing: Quantum algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) offer potentially exponential speedup for electronic structure calculations, though current hardware limitations restrict application to small model systems [3].

Tensor Network Methods: Efficient representations of many-body wavefunctions using matrix product states and tensor trains that capture essential correlation effects while reducing computational scaling [3].

The fundamental impossibility of exactly solving the full molecular Schrödinger equation for multi-electron systems has profound implications for computational chemistry and drug development. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provides an essential conceptual and computational framework that enables practical calculations of molecular structure, dynamics, and properties, but its limitations must be recognized and addressed through sophisticated methodological developments [2] [4].

For pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these fundamental limitations is crucial for interpreting computational predictions and designing effective strategies. The hierarchical approximation approach, combined with emerging machine learning and quantum computing methods, continues to extend the boundaries of computational tractability while acknowledging that the exact solution remains theoretically and practically inaccessible for biologically relevant systems [3]. This understanding fosters appropriate caution in interpreting computational results while driving innovation in methodological development that pushes the boundaries of what is computationally achievable in molecular quantum mechanics.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation represents one of the most fundamental concepts in molecular quantum mechanics, enabling the modern understanding of chemical structure, dynamics, and reactivity. Proposed by Max Born and J. Robert Oppenheimer in 1927, this approximation forms the foundational framework upon which much of computational chemistry and molecular physics is built [2] [6]. At its core, the BO approximation leverages the profound mass disparity between atomic nuclei and electrons—a physical reality that creates a natural separation of time scales in molecular dynamics [7]. This separation allows researchers to treat the motions of nuclei and electrons as distinct yet interconnected problems, dramatically simplifying the mathematical complexity of molecular Schrödinger equations [8] [2].

The significance of this approximation extends far beyond theoretical interest; it provides the conceptual basis for potential energy surfaces, molecular geometry optimization, transition state theory, and spectroscopic interpretation [7] [6]. Within pharmaceutical research and drug development, the BO approximation enables computational predictions of molecular properties, reaction pathways, and intermolecular interactions that would be otherwise intractable [9] [10]. Despite its central importance, the approximation is often misunderstood as either freezing nuclear positions or treating nuclei classically, both of which represent misinterpretations of the original framework [6]. This whitepaper examines the physical principles underlying the BO approximation, its mathematical formulation, breaking conditions, and contemporary applications in molecular systems research, particularly within drug discovery contexts.

The Physical Basis: Mass Disparity and Time Scale Separation

The Mass Ratio Argument

The fundamental insight behind the Born-Oppenheimer approximation stems from the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei. A proton, the nucleus of a hydrogen atom, has a mass approximately 1,836 times greater than that of an electron [7]. For heavier elements, this mass ratio increases substantially, with carbon nuclei being over 22,000 times heavier than electrons. This mass disparity has profound implications for molecular dynamics, as the same force acting on particles of different masses produces dramatically different accelerations according to Newton's second law (a = F/m) [8].

In practical terms, this mass difference means electrons respond almost instantaneously to changes in nuclear configuration. From the perspective of the electrons, the nuclei appear nearly stationary, while from the nuclear perspective, the electrons form a continuous, rapidly adjusting charge cloud [7] [6]. This physical picture enables the central approximation: we can separate the complete molecular wavefunction into electronic and nuclear components, treating the electronic motion as if the nuclei were fixed in space, then solving for nuclear motion in the resulting averaged electronic potential [2].

Table 1: Mass and Velocity Comparisons Between Subatomic Particles

| Particle Type | Mass (kg) | Mass (atomic units) | Mass Ratio (relative to electron) | Characteristic Velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron | 9.11 × 10⁻³¹ | 1 | 1 | ~10⁶ m/s |

| Proton | 1.67 × 10⁻²⁷ | 1836 | 1836 | ~10³ m/s |

| Carbon-12 nucleus | 2.00 × 10⁻²⁶ | 21894 | 21894 | ~10² m/s |

Mathematical Formulation of the Approximation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provides a systematic approach to simplify the molecular Schrödinger equation. The complete molecular Hamiltonian can be expressed as:

[ H{\text{total}} = Te + Tn + V{ee} + V{nn} + V{en} ]

where (Te) and (Tn) represent the kinetic energy operators for electrons and nuclei respectively, while (V{ee}), (V{nn}), and (V_{en}) correspond to electron-electron, nucleus-nucleus, and electron-nucleus potential energy operators [2].

The BO approximation proceeds in two key steps:

- Clamped-nuclei electronic Schrödinger equation: The nuclear kinetic energy term ((T_n)) is initially neglected, with nuclear positions treated as fixed parameters rather than dynamic variables. For each nuclear configuration ( \mathbf{R} ), we solve the electronic Schrödinger equation:

[ He(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = Ek(\mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ]

where (He = Te + V{ee} + V{en} + V{nn}), (\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) represents the electronic wavefunction for the k-th state, and (E_k(\mathbf{R})) is the corresponding electronic energy [2].

- Nuclear Schrödinger equation: The computed electronic energy (E_k(\mathbf{R})) serves as a potential energy surface for nuclear motion, leading to the nuclear Schrödinger equation:

[ [Tn + Ek(\mathbf{R})] \phi(\mathbf{R}) = E \phi(\mathbf{R}) ]

where (\phi(\mathbf{R})) describes the nuclear wavefunction, and (E) represents the total molecular energy [2].

This separation reduces the original 3(Nₑ + Nₙ)-dimensional problem (where Nₑ and Nₙ represent the number of electrons and nuclei respectively) into a 3Nₑ-dimensional electronic problem solved multiple times for different nuclear configurations, followed by a 3Nₙ-dimensional nuclear problem [2]. For a benzene molecule (12 nuclei and 42 electrons), this reduces the problem from 162 coupled coordinates to more manageable components: 126 electronic coordinates solved repeatedly across a grid of nuclear positions, followed by 36 nuclear coordinates [2].

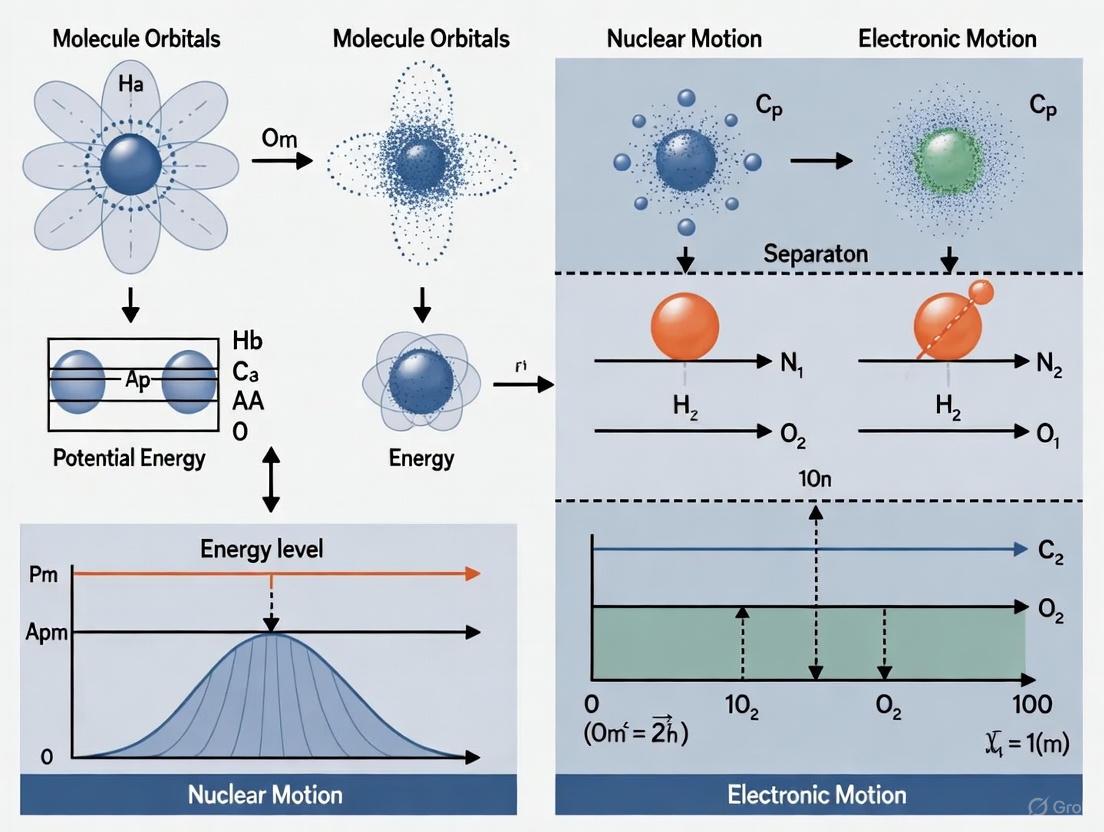

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual separation and energy flow in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation:

Diagram 1: Born-Oppenheimer approximation workflow showing the separation of electronic and nuclear motions.

When the Approximation Breaks Down: Limitations and Breakdown Conditions

Conditions for BO Validity and Vibronic Coupling

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation remains valid when electronic potential energy surfaces are well-separated, satisfying the condition:

[ E0(\mathbf{R}) \ll E1(\mathbf{R}) \ll E_2(\mathbf{R}) \ll \cdots \quad \text{for all } \mathbf{R} ]

Under these conditions, nuclear motion occurs predominantly on a single electronic surface without significant transitions between surfaces [2]. However, this approximation fails when electronic states become degenerate or nearly degenerate, leading to what is known as "vibronic coupling" [6].

Breakdown occurs specifically when:

- Surface crossings or avoided crossings: Electronic states become close in energy, typically at specific nuclear configurations

- Conical intersections: Points where electronic states are exactly degenerate, creating a funnel for rapid non-adiabatic transitions

- Significant non-adiabatic coupling: When the nuclear kinetic energy operator creates substantial mixing between electronic states

The mathematical manifestation of breakdown appears in the form of non-adiabatic coupling terms:

[ \Lambda{kl} = \langle \chik | Tn | \chil \rangle + \sum{A} \frac{1}{MA} \langle \chik | \nablaA \chil \rangle \cdot \nablaA ]

These terms are typically neglected in the BO approximation but become significant when electronic states are close in energy [2]. In such cases, the complete wavefunction must be expressed as a sum of products:

[ \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \sum{k=1}^K \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \phi_k(\mathbf{R}) ]

where the summation includes multiple electronic states, and the nuclear wavefunctions (\phi_k(\mathbf{R})) are coupled through the non-adiabatic operators [2].

Table 2: Conditions for Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Validity and Breakdown

| Scenario | Electronic Structure | Nuclear Dynamics | BO Approximation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-separated ground state | (E0 \ll E1) | Adiabatic on ground PES | Valid | Stable organic molecules at room temperature |

| Low-energy excited states | (E1 ) slightly > (E0) | Possible weak coupling | Mostly valid | Fluorescent dyes, some photochemical processes |

| Near-degenerate states | (E1 \approx E0) at some R | Strong non-adiabatic coupling | Breaks down | Conical intersections in photoisomerization |

| Exact degeneracy | (E1 = E0) at point R | Ultrafast transitions | Completely fails | Conical intersections, Jahn-Teller systems |

Experimental and Computational Detection of Breakdown

The breakdown of the BO approximation manifests in several experimental and computational contexts:

- Spectroscopic signatures: Unexpected band shapes, anomalous vibrational progressions, or forbidden transitions appearing in electronic spectra

- Reactivity anomalies: Reaction products or rates that deviate significantly from single-surface predictions

- Ultrafast dynamics: Femtosecond to picosecond timescale processes indicating rapid transitions between electronic states

Computationally, breakdown is detected through:

- Significant magnitude of non-adiabatic coupling vectors

- Small energy gaps between electronic states during dynamics simulations

- Failure of single-reference electronic structure methods

The following diagram illustrates the key differences between the Born-Oppenheimer regime and its breakdown:

Diagram 2: Conditions leading to Born-Oppenheimer approximation validity versus breakdown.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Computational Verification Protocols

Electronic Structure Calculations for Potential Energy Surfaces

Computational verification of the BO approximation's validity involves detailed mapping of potential energy surfaces and their couplings:

Multi-reference electronic structure methods: Utilize complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) or multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI) calculations to properly describe near-degenerate electronic states [6]

Non-adiabatic coupling elements: Compute the derivative coupling vectors ( \langle \chik | \nablaR \chi_l \rangle ) between electronic states using response theory or finite difference methods

Dynamics simulations: Implement either:

Conical intersection optimization: Locate and characterize points of exact degeneracy between electronic states using gradient-based search algorithms

Protocol for Assessing BO Approximation Validity:

- Perform geometry optimization on ground and excited states

- Calculate energy gaps between electronic states along relevant nuclear coordinates

- Compute non-adiabatic coupling strengths at geometries where energy gaps are small

- Estimate coupling magnitudes relative to nuclear kinetic energy

- For small gaps and strong couplings, employ beyond-BO dynamics methods

Spectroscopic Detection Methods

Experimental verification of BO breakdown employs advanced spectroscopic techniques:

Time-Resolved Photoelectron Spectroscopy (TRPES)

- Pump-probe methodology with femtosecond time resolution

- Maps electronic population transfer following photoexcitation

- Directly observes non-adiabatic transitions through changing electron kinetic energy distributions

Two-Dimensional Electronic Spectroscopy (2DES)

- Reveals couplings between electronic states through cross-peaks

- Tracks energy flow between states on ultrafast timescales

- Provides both frequency and time resolution for complete dynamical picture

Vibronic Spectroscopy in Jet-Cooled Molecules

- High-resolution spectroscopy of cold molecules eliminates thermal broadening

- Direct observation of vibrational-electronic (vibronic) coupling patterns

- Quantifies Herzberg-Teller coupling contributions through intensity borrowing

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Born-Oppenheimer and Beyond-BO Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Methods | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Packages | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, Q-Chem | PES calculation, geometry optimization | BO validity assessment, ground state dynamics |

| Multi-reference Methods | MOLPRO, MOLCAS, COLUMBUS | Diabatic representation, conical intersection search | Near-degeneracy regions, photochemical reactions |

| Non-adiabatic Dynamics | SHARC, Newton-X, Tully's FSSH | Trajectory surface hopping simulations | BO breakdown regimes, ultrafast photodynamics |

| Wavepacket Propagation | MCTDH, Wavepacket | Quantum nuclear dynamics | Vibronic spectroscopy, light-induced processes |

| Vibronic Coupling Models | VCHAM, Vibronic | Model Hamiltonian parameterization | Systematic studies of BO breakdown patterns |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Mass Spectrometry and Molecular Imaging

The principles underlying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation find practical application in pharmaceutical research through advanced analytical techniques. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has emerged as a powerful tool for untargeted investigation of spatial distribution of molecular species in biological samples [12]. This technique enables imaging of thousands of molecules—including metabolites, lipids, peptides, proteins, and glycans—in a single experiment without labeling [12].

In MSI experiments, the mass spectrometer ionizes molecules on a sample surface and collects a mass spectrum at each pixel, with spatial resolution defined by pixel size [12]. The resulting data allows researchers to extract intensity information for specific mass-to-charge (m/z) values and create heat map images depicting molecular distributions throughout the sample [12]. This application implicitly relies on the BO framework through its dependence on molecular ionization potentials and fragmentation patterns that are interpreted through computational chemistry methods grounded in the BO approximation.

High-Throughput Screening in Drug Discovery

Recent technological developments have revolutionized the application of mass spectrometry for high-throughput (HT) screening in early drug discovery pipelines [9]. HT-MS platforms enable label-free detection of biomolecules in screening assays, expanding the breadth of targets for which HT assays can be developed compared to traditional approaches [9].

These MS-based screening methods include:

- Affinity selection mass spectrometry: Identifies target binders from complex mixtures

- Biochemical activity screening: Directly measures enzyme substrates and products

- Cellular phenotypic screening: Detects compound-induced changes in cellular metabolism

The BO approximation facilitates the computational drug design component of these efforts by enabling efficient prediction of drug-target interactions, binding affinities, and metabolic stability through quantum mechanical calculations that would be prohibitively expensive without the separation of electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation remains one of the most successful and widely applied concepts in molecular quantum mechanics, with its core physical insight—leveraging the mass disparity between nuclei and electrons—continuing to enable advances across chemical physics, materials science, and pharmaceutical research. While modern computational methods have developed sophisticated approaches to handle cases where the approximation breaks down, the BO framework provides the essential foundation upon which our understanding of molecular structure and dynamics is built.

In pharmaceutical contexts, the BO approximation enables everything from molecular property prediction to drug-receptor interaction modeling, while its limitations in describing non-adiabatic processes inform research in photodynamic therapy and radiation-induced damage. As computational power increases and experimental techniques achieve greater temporal and spatial resolution, the fundamental insight of separated electronic and nuclear motions continues to guide both theoretical development and practical applications in molecular systems research.

In quantum chemistry, the description of molecular systems begins with the molecular Hamiltonian, which encapsulates the total energy of all electrons and nuclei. For a molecule with multiple electrons and nuclei, the complete, non-relativistic Coulomb Hamiltonian is expressed as follows [13]: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} = \hat{T}n + \hat{T}e + \hat{U}{en} + \hat{U}{ee} + \hat{U}{nn} ] where the terms respectively represent the nuclear kinetic energy, the electronic kinetic energy, the electron-nucleus attraction, the electron-electron repulsion, and the nucleus-nucleus repulsion [13]. The challenge in solving the corresponding Schrödinger equation arises from the coupled nature of the nuclear and electronic coordinates. The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation provides the foundational framework for decoupling these motions, thereby simplifying the problem into more tractable parts. This separation is justified by the significant disparity in mass between nuclei and electrons, which causes nuclei to move on a much slower timescale, allowing electrons to be treated as moving within a field of effectively stationary nuclei [2] [14] [15]. This whitepaper details the mathematical formalism of separating the Hamiltonian and derives the central equation for electronic structure theory: the electronic Schrödinger equation.

Mathematical Decomposition of the Molecular Hamiltonian

The Full Coulomb Hamiltonian

The Coulomb Hamiltonian is written explicitly in atomic units as [2] [13]: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} = -\sum{A} \frac{1}{2MA}\nabla{A}^{2} - \sum{i} \frac{1}{2}\nabla{i}^{2} - \sum{i,A} \frac{ZA}{r{iA}} + \sum{i>j} \frac{1}{r{ij}} + \sum{B>A} \frac{ZA ZB}{R{AB}} ] Here, the indices ( A, B ) refer to nuclei, and ( i, j ) refer to electrons. The terms ( MA ) and ( ZA ) are the mass and atomic number of nucleus ( A ), while ( r{iA} ), ( r{ij} ), and ( R{AB} ) denote electron-nucleus, electron-electron, and nucleus-nucleus distances, respectively [2]. The Laplacian operators ( \nabla{A}^{2} ) and ( \nabla{i}^{2} ) represent the kinetic energy of nuclei and electrons.

Table 1: Components of the Full Molecular Coulomb Hamiltonian

| Term Symbol | Mathematical Expression | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|

| ( \hat{T}_n ) | ( -\sum{A} \frac{1}{2MA}\nabla_{A}^{2} ) | Kinetic energy of the nuclei |

| ( \hat{T}_e ) | ( -\sum{i} \frac{1}{2}\nabla{i}^{2} ) | Kinetic energy of the electrons |

| ( \hat{U}_{en} ) | ( -\sum{i,A} \frac{ZA}{r_{iA}} ) | Attractive potential between electrons and nuclei |

| ( \hat{U}_{ee} ) | ( \sum{i>j} \frac{1}{r{ij}} ) | Repulsive potential between electrons |

| ( \hat{U}_{nn} ) | ( \sum{B>A} \frac{ZA ZB}{R{AB}} ) | Repulsive potential between nuclei |

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation and Hamiltonian Separation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation states that the total wavefunction can be separated into a product of a nuclear wavefunction and an electronic wavefunction [2]: [ \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \psi{\text{nuclear}}(\mathbf{R}) \cdot \psi{\text{electronic}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ] A critical step is recognizing that the nuclear kinetic energy term ( \hat{T}n ) is negligible when solving for the electronic wavefunction. This is because the mass of a nucleus is thousands of times greater than that of an electron, leading to much smaller accelerations for a given force [14] [15]. Consequently, the nuclei can be treated as fixed, classical point charges when determining the electronic state. This leads to the so-called clamped-nuclei Hamiltonian or electronic Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}e ) [2] [13], obtained by omitting ( \hat{T}n ) from the full Hamiltonian: [ \hat{H}e(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \hat{T}e + \hat{U}{en} + \hat{U}{ee} + \hat{U}{nn} ] It is crucial to note that the electronic Hamiltonian ( \hat{H}e ) depends parametrically on the nuclear coordinates ( \mathbf{R} ). This means ( \mathbf{R} ) is not a quantum mechanical variable in the electronic equation but a set of fixed parameters. The nuclear repulsion term ( \hat{U}_{nn} ) is a constant for a fixed nuclear configuration [2].

Diagram 1: Workflow for separating the Hamiltonian via the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, showing the derivation of the electronic Schrödinger equation and the potential energy surface.

The Electronic Schrödinger Equation

Definition and Eigenvalue Problem

With the electronic Hamiltonian defined, the electronic Schrödinger equation is formulated as follows [2] [15]: [ \hat{H}e(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = E{e,k}(\mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ] Here, ( \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ) is the electronic wavefunction for the ( k )-th electronic state, and ( E{e,k}(\mathbf{R}) ) is the corresponding electronic energy eigenvalue. Both quantities depend parametrically on the nuclear coordinates ( \mathbf{R} ). The electronic energy includes contributions from electron kinetics, all Coulomb interactions, and crucially, the constant nuclear repulsion term ( U{nn} ). The total energy for a given electronic state at a fixed nuclear configuration is ( E{e,k}(\mathbf{R}) ) [2].

The Potential Energy Surface (PES)

By solving the electronic Schrödinger equation for a range of nuclear configurations, one maps out a Potential Energy Surface (PES), ( E_{e,k}(\mathbf{R}) ). This surface governs the motion of the nuclei [2] [14]. The PES is a central concept in quantum chemistry, as it allows for the subsequent treatment of nuclear motion (vibrations, rotations) and the analysis of molecular geometry, stability, and reaction pathways [14].

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Workflow for Electronic Structure Calculation

The theoretical separation described above translates into a standard computational workflow in quantum chemistry.

- Define Molecular Geometry: Specify the atomic symbols ( {Z_A} ) and nuclear coordinates ( \mathbf{R} ) for the system [16].

- Select Atomic Basis Set: Choose a set of basis functions (e.g., Gaussian-type orbitals) to represent the molecular orbitals [16].

- Solve the Electronic Problem: For the fixed nuclear configuration, compute the electronic wavefunction ( \chik ) and energy ( E{e,k} ). This is typically done at the Hartree-Fock (HF) level or with post-HF methods to account for electron correlation [16].

- Construct the PES: Repeat the electronic structure calculation over a grid of nuclear coordinates to build the PES [2].

- Solve Nuclear Dynamics: Use the PES ( E_{e,k}(\mathbf{R}) ) in a nuclear Schrödinger equation to study vibrations and rotations, or in classical molecular dynamics simulations [14].

Advanced Implementation: Second Quantization and Quantum Computing

For advanced simulations, particularly on quantum computers, the electronic Hamiltonian is often transformed into the second quantization formalism [16]: [ \hat{H}e = \sum{pq} h{pq} cp^\dagger cq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} cp^\dagger cq^\dagger cr cs ] Here, ( cp^\dagger ) and ( cq ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators, and ( h{pq} ) and ( h_{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals computed in a molecular orbital basis. This fermionic Hamiltonian can then be mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian using transformations like the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev encoding, enabling quantum algorithm deployment [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electronic Structure Calculations

| Reagent / Computational Tool | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|

| Atomic Orbital Basis Sets | Serve as basis functions for expanding molecular orbitals, critical for representing the electronic wavefunction. |

| Hartree-Fock Solver | Computes the mean-field approximation of the electronic wavefunction and optimizes molecular orbital coefficients. |

| Electronic Integral Packages | Calculate the one- and two-electron integrals ( (h{pq}, h{pqrs}) ) over the chosen basis set, which are the building blocks of the Hamiltonian. |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mappers (e.g., Jordan-Wigner) | Transform the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian into a Pauli spin operator form executable on a quantum processor. |

| Classical Quantum Chemistry Packages (e.g., PySCF, Q-Chem) | Perform the complete workflow from molecular structure to PES construction using high-performance computing resources. |

Diagram 2: Detailed protocol for building the electronic Hamiltonian in a form suitable for quantum simulations, from molecular structure to a solvable qubit Hamiltonian.

Limitations and Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Formalism

The BO approximation is highly successful but fails when electronic states become nearly degenerate, such as at conical intersections. In these regions, the coupling terms involving nuclear momentum operators ( \hat{P}{A\alpha} = -i \frac{\partial}{\partial R{A\alpha}} ) acting on the electronic wavefunction can no longer be ignored [2] [17]. This breakdown necessitates beyond-BO methods. One advanced approach is the exact factorization framework, which expresses the total wavefunction as a single product ( \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}, t) = \chi(\mathbf{R}, t) \Phi_{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}, t) ) without approximation [17]. This leads to coupled equations for the nuclear and conditional electronic wavefunctions, introducing time-dependent vector and scalar potentials that mediate the exact electron-nuclear coupling, providing a formally exact path for simulating coupled dynamics [17].

The mathematical formalism of separating the full molecular Hamiltonian via the Born-Oppenheimer approximation is a cornerstone of modern molecular quantum mechanics. It reduces the intractable coupled problem into a sequence of manageable steps: defining an electronic Hamiltonian that depends parametrically on nuclear coordinates, solving the electronic Schrödinger equation to generate a potential energy surface, and finally treating nuclear motion on this surface. This formalism enables the computational prediction of molecular structure, properties, and reactivity, forming the theoretical foundation for a vast range of applications in drug discovery, materials science, and chemical physics. While the BO approximation is remarkably effective, ongoing research into non-adiabatic processes and beyond-BO methods like the exact factorization framework continues to expand the frontiers of simulating coupled electron-nuclear dynamics.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, introduced in 1927 by Max Born and J. Robert Oppenheimer, represents one of the most foundational concepts in quantum chemistry and molecular physics [2] [18]. This approximation exploits the significant mass disparity between atomic nuclei and electrons to separate their motions, thereby transforming the intractable many-body molecular Schrödinger equation into a solvable problem [19]. This whitepaper traces the historical development of the BO approximation from its theoretical origins to its modern status as an indispensable tool in computational chemistry, with a specific focus on its applications and limitations in molecular systems research and drug discovery. We provide a detailed analysis of its theoretical underpinnings, quantitative performance across computational methods, and protocols for its application in contemporary research, framing this discussion within a broader thesis on its enduring impact on molecular sciences.

The year 1927 was a period of intense development in quantum mechanics, just one year after Erwin Schrödinger published his famous wave equation [20]. In this fertile environment, the 23-year-old J. Robert Oppenheimer, working under the guidance of Max Born, proposed the approximation that would bear their names [2] [18]. Although the theory is jointly attributed, most historians recognize that the majority of the work was carried out by Oppenheimer himself [18].

The fundamental challenge addressed by the BO approximation was the quantum mechanical description of molecules, which requires defining the positions and movements of all atomic nuclei and electrons and computing the complex charge interactions between these particles [18]. Solving the molecular Schrödinger equation presented a formidable challenge—it could not be solved exactly even for the simplest molecule, H₂⁺, consisting of just two protons and one electron [18].

Oppenheimer's key insight was recognizing that atomic nuclei are much heavier than electrons, with a single proton weighing nearly 2,000 times more than an electron [18]. This mass disparity, on the order of ~10³, meant that nuclei move significantly slower than electrons [20] [21]. Consequently, electrons effectively instantaneously adjust to nuclear motion, allowing scientists to treat nuclei as nearly stationary while solving the Schrödinger equation exclusively for electrons [2] [19]. This conceptual separation dramatically simplified the complexity of quantum mechanical calculations for molecules.

Theoretical Framework and Computational Workflow

Mathematical Formulation

The BO approximation begins with the complete molecular Hamiltonian, which includes all kinetic and potential energy terms for nuclei and electrons [2] [21]. The approximation recognizes the large difference between electron mass and the masses of atomic nuclei, and correspondingly the time scales of their motion [2].

The total wave function is expressed as a product of electronic and nuclear wave functions [2] [21]:

Ψ_total(r,R) = ψ_electronic(r; R) ψ_nuclear(R)

Here, r represents all electronic coordinates and R represents all nuclear coordinates [21]. The electronic wave function ψ_electronic depends parametrically on the nuclear positions R [2] [21]. This parametric dependence is continuous and differentiable, though the derivatives are generally non-zero and lead to coupling terms [2].

The molecular Schrödinger equation is separated into two coupled equations [2] [21]:

The Electronic Schrödinger Equation: For fixed nuclear positions, one solves:

H_e χ_k(r; R) = E_k(R) χ_k(r; R)whereH_eis the electronic Hamiltonian,χ_kis the electronic wavefunction for state k, andE_k(R)is the electronic energy as a function of nuclear configuration [2].The Nuclear Schrödinger Equation: Using the electronic energy as a potential, one solves:

[T_n + E_e(R)] ϕ(R) = E ϕ(R)whereT_nis the nuclear kinetic energy operator [2].

Computational Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard computational workflow enabled by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation:

This computational workflow demonstrates how the BO approximation enables practical quantum chemistry calculations. The electronic structure calculation forms the foundation, repeated for various nuclear arrangements to map out a Potential Energy Surface (PES) [19]. This surface then dictates how the nuclei move, vibrate, and rotate [19]. Minima on this surface correspond to stable molecular structures (equilibrium geometries), saddle points represent transition states for chemical reactions, and the overall topography governs molecular vibrations and reaction pathways [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Methods

Table 1: Quantum Chemical Methods Relying on the BO Approximation

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Key Features | Computational Scaling | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wavefunction theory using single Slater determinant [22] [23] | Neglects electron correlation; self-consistent field (SCF) approach [22] | O(N⁴) with basis set size [23] | Baseline electronic structures; starting point for correlated methods [23] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density rather than wavefunction [22] [23] | Includes approximate exchange-correlation functional; good accuracy/efficiency balance [22] | O(N³) to O(N⁴) [22] | Most widely used QM method; molecular structures, properties, reaction pathways [23] |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2) | Post-HF electron correlation treatment [22] | Accounts for electron correlation via perturbation theory [22] | O(N⁵) [22] | More accurate binding energies; dispersion interactions [22] |

| Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Post-HF using exponential cluster operator [22] | "Gold standard" for molecular energy calculations [22] | O(N⁷) or higher [22] | High-accuracy reference calculations; benchmark studies [22] |

The computational methods summarized in Table 1 all fundamentally rely on the BO approximation, demonstrating its pervasive influence across quantum chemistry. The choice of method involves a trade-off between accuracy and computational cost, with more accurate methods typically requiring significantly more resources [22].

Quantitative Performance and Methodological Comparisons

Computational Efficiency Gains

The BO approximation provides dramatic reductions in computational complexity. For illustration, consider the benzene molecule (C₆H₆), which consists of 12 nuclei and 42 electrons [2]. The full Schrödinger equation requires solving for 3 × 12 = 36 nuclear plus 3 × 42 = 126 electronic coordinates, totaling 162 variables [2]. Since computational complexity increases faster than the square of the number of coordinates, the full problem would require solving at least 162² = 26,244 variables [2].

Using the BO approximation, this problem is separated into [2]:

- Electronic problem: 126 electronic coordinates, solved multiple times for different nuclear configurations

- Nuclear problem: 36 nuclear coordinates, solved once on the pre-computed potential energy surface

This separation reduces the computational complexity from a single O(162²) problem to multiple O(126²) problems plus one O(36²) problem, representing a substantial reduction in computational demand [2].

Accuracy Comparison Across Methods

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method | Bond Length Accuracy | Binding Energy Error | Computational Time (Relative) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mechanics (MM) | Poor for unusual bonding features [22] | Very poor at conformational prediction [22] | Fraction of a second [22] | Cannot model polarizability, charge transfer, or bond breaking/formation [22] |

| Semiempirical Methods | Moderate [22] | Moderate [22] | Seconds to minutes [22] | Parameter-dependent; limited transferability [22] |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Bonds typically too long and weak [22] | Underestimates by 20-30% for non-covalent interactions [22] | Minutes to hours [22] | Neglects electron correlation; poor for dispersion forces [23] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Good with appropriate functional [22] [23] | ~1-3 kcal/mol error with modern functionals [23] | Hours to days [22] | Exchange-correlation functional choice critical; delocalization errors [23] |

| MP2 and Coupled Cluster | Excellent [22] | <1 kcal/mol for CCSD(T) [22] | Days to weeks [22] | Computationally prohibitive for large systems [22] |

The data in Table 2 illustrates the Pareto frontier of quantum chemistry methods, where increasing accuracy comes at the cost of greater computational resources [22]. Molecular mechanics methods (force fields) are fast but lack quantum mechanical accuracy, while high-level wavefunction methods provide exceptional accuracy but at extreme computational cost [22].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Molecular Design

Key Application Areas

The BO approximation enables numerous critical applications in drug discovery and molecular design:

- Equilibrium Geometry Prediction: Finding the lowest energy structure on the potential energy surface, which corresponds to stable molecular conformations [19].

- Vibrational Frequency Analysis: Analyzing the curvature of the PES around a minimum to predict molecular vibrational spectra, which aids in structure validation and characterization [19].

- Reaction Pathway Studies: Identifying transition states and activation barriers on the PES to understand and predict chemical reactivity and reaction mechanisms [19].

- Binding Affinity Calculations: Modeling protein-ligand interactions and computing binding energies to optimize drug candidate potency [23].

Experimental Protocol: DFT Calculation for Drug Design

For researchers applying these methods, here is a detailed protocol for a typical DFT calculation in drug discovery:

System Preparation

- Obtain initial molecular coordinates from crystallography, molecular docking, or molecular mechanics optimization

- Define the molecular system including protonation states relevant to physiological conditions

- For large systems, consider QM/MM approaches where the active site is treated with QM and the protein environment with molecular mechanics [23]

Method Selection

Calculation Execution

- Perform geometry optimization to locate minima on the PES

- Confirm stationary points with frequency calculations (no imaginary frequencies for minima, one for transition states)

- Compute single-point energies with higher-level methods if needed

Analysis

- Analyze molecular orbitals, electrostatic potentials, and electron densities

- Calculate binding energies using appropriate counterpoise corrections for basis set superposition error

- Compare with experimental data (spectra, binding affinities, reaction rates) for validation

This protocol enables researchers to predict molecular properties, binding modes, and reactivities that inform drug design decisions [23].

Limitations and Breakdown of the Approximation

When the BO Approximation Fails

Despite its widespread success, the BO approximation has well-established limitations. It may break down in specific scenarios, such as light-driven chemical reactions or processes enabling vision in animals [18]. The breakdown occurs when the central assumption of separable electronic and nuclear motion becomes invalid [21].

The most dramatic failures occur at conical intersections, points in nuclear configuration space where two or more electronic potential energy surfaces touch or become degenerate [19] [21]. Near these points, non-adiabatic coupling terms become large, and the assumption of separate electronic and nuclear motion is entirely invalid [19]. Dynamics passing through conical intersections are ultrafast and play a crucial role in determining reaction outcomes, photostability, and energy relaxation pathways [19].

The formal breakdown can be understood mathematically through the nuclear derivative couplings that are neglected in the standard BO approximation [21]. The complete molecular wavefunction including multiple electronic states is:

Ψ(r,R) = Σ ψ_j(r; R) χ_j(R)

Substituting this into the full Schrödinger equation reveals coupling terms of the form [21]:

⟨ψ_i|T_N|ψ_j⟩- kinetic coupling between electronic statesΣ_α -ℏ²/2m_α ⟨ψ_i|∇_R_α|ψ_j⟩·∇_R_α- non-adiabatic coupling operators

These terms are responsible for transitions between electronic states and become significant when electronic energy levels become close or degenerate [21].

Advanced Methods Beyond BO

Table 3: Methods for Handling BO Breakdown

| Method | Approach | Applications | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Surface Hopping | Classical nuclei with stochastic hops between PESs [19] | Photochemical reactions, electron transfer [19] | Moderate to high |

| Multi-Configuration Time-Dependent Hartree (MCTDH) | Quantum dynamics for nuclei on multiple PESs [19] | Accurate quantum dynamics in small systems [19] | Very high |

| Nuclear-Electronic Orbital (NEO) Theory | Treats specified nuclei (e.g., protons) quantum mechanically alongside electrons [24] | Proton transfer, hydrogen bonding [24] | High |

| Multi-Component Unitary Coupled Cluster (mcUCC) | Quantum computing approach treating electrons and nuclei simultaneously [24] | Small model systems; proof of concept [24] | Extremely high |

For systems where the BO approximation fails, the methods in Table 3 provide more accurate treatments. Recent advances include multicomponent quantum simulations that treat both electronic and nuclear quantum effects simultaneously, implemented on quantum hardware with error mitigation techniques [24].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between different computational approaches for molecular systems:

Emerging Directions

The future of the BO approximation in molecular research involves both pushing its boundaries and developing methods for its limitations:

Quantum Computing: Quantum computers hold promise for enhancing computational quantum chemistry by enabling faster calculations on increasingly complex molecular systems [18] [24]. Recent demonstrations of error-mitigated multicomponent simulations on quantum hardware represent early steps toward this future [24].

Machine Learning Force Fields: Machine learning approaches are being developed to learn potential energy surfaces from quantum mechanical data, maintaining accuracy while dramatically reducing computational cost [22].

Non-Adiabatic Dynamics: Methods for simulating dynamics beyond the BO approximation continue to advance, enabling more accurate modeling of photochemical processes, charge transfer, and other electronically non-adiabatic phenomena [19].

From its inception in 1927 to the present day, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation has evolved from a theoretical concept to a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and molecular design. Its simplicity—separating electronic and nuclear motion based on mass disparity—belies its transformative impact, enabling the practical application of quantum mechanics to molecular systems of biological and technological relevance.

While the approximation has limitations, particularly in photochemistry and processes involving multiple electronic states, it remains the foundation upon which most quantum chemical methods are built. Its enduring legacy is reflected in its pervasive use across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, where it continues to enable researchers to understand and predict molecular structure, properties, and reactivity. As computational power grows and new theoretical approaches emerge, the BO approximation will continue to serve as both a practical tool and a conceptual framework for understanding the quantum nature of molecules.

From Theory to Therapy: Applying Born-Oppenheimer Methods in Computational Drug Design

Computational chemistry plays a critical role in advancing molecular science by bridging theoretical frameworks and experimental observations, providing detailed insight into the structural, electronic, and reactive properties of molecules and materials [25]. The field relies on a hierarchical approach to modeling, employing methods of varying computational cost and accuracy to address different scientific questions. At the core of this hierarchy lies the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, which serves as the fundamental tenet enabling most practical computational chemistry applications [6] [26]. This approximation introduces a hierarchy in electron-nuclear interactions by separating the motion of electrons from that of the nuclei, allowing chemists to picture molecules as nuclei connected by electrons rather than as a homogeneous "soup" of interacting particles [6].

Despite its central importance, the BO approximation is often misinterpreted. Widespread claims within the chemistry community incorrectly imply that this approximation enforces nuclei to be frozen or treated as classical particles [6]. In reality, the BO approximation does not require frozen nuclei; rather, it provides a mathematical framework for separating electronic and nuclear motions, forming the basis for potential energy surfaces on which nuclei move [6] [26]. When this approximation breaks down—as in photochemical processes or systems involving proton tunneling—more sophisticated methods beyond BO become necessary [27] [28]. This review examines the computational hierarchy from quantum mechanics to multi-scale QM/MM methods, framed within the foundational context of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation in molecular systems research.

Theoretical Framework: The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation finds its roots in solving the molecular Schrödinger equation, which describes the quantum mechanical behavior of a molecule comprising multiple electrons and nuclei [6]. The full molecular Hamiltonian operator, as defined in atomic units, includes kinetic energy terms for all nuclei and electrons, as well as potential energy terms for all interparticle interactions [26]. Solving this equation directly is mathematically intractable for all but the simplest systems due to the coupled nature of all particles.

The BO approximation addresses this challenge by exploiting the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei. Since nuclei are thousands of times heavier than electrons, their motion is considerably slower [26]. This separation of time scales allows for the approximation that electrons instantaneously adjust their distribution to any new configuration of the nuclei. Mathematically, this enables the separation of the total molecular wavefunction into electronic and nuclear components [26]. The electronic Schrödinger equation is solved for fixed nuclear positions, generating a potential energy surface on which the nuclei subsequently move [6] [23].

This theoretical framework enables the concept of molecular geometry, bonding, and potential energy surfaces that underpin modern computational chemistry. However, in systems where electronic and nuclear motions become strongly coupled—such as in conical intersections, proton-coupled electron transfer, or systems with significant hydrogen tunneling—the BO approximation breaks down, necessitating more sophisticated treatments that explicitly account for non-adiabatic effects [27] [28]. For most chemical applications, including drug discovery and materials design, the BO approximation remains the essential starting point that makes computational modeling feasible [23].

Quantum Mechanical Methods

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Spectrum

Quantum mechanical (QM) methods serve as the theoretical bedrock of computational chemistry, providing a rigorous framework for understanding molecular structure, reactivity, and properties at the atomic level [25]. These methods solve the electronic Schrödinger equation under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, calculating the electronic structure of molecules for fixed nuclear positions. The fundamental goal is to determine molecular wavefunctions and energies, from which all other molecular properties can be derived.

The methodological spectrum of quantum chemistry encompasses various approaches with distinct trade-offs between computational efficiency and accuracy. Ab initio (first-principles) methods derive molecular properties directly from physical principles without empirical parameters [25]. These include:

- Hartree-Fock (HF) method: One of the earliest quantum chemical models that approximates electrons as independent particles moving in an averaged electrostatic field [25]. While widely used as a reference for more sophisticated techniques, its neglect of electron correlation limits predictive accuracy for interaction energies and bond dissociation [25] [23].

- Post-Hartree-Fock methods: Include Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2), Configuration Interaction (CI), and Coupled Cluster (CC) theory, which address electron correlation directly and offer greater accuracy [25]. The Coupled Cluster with Single, Double, and perturbative Triple excitations (CCSD(T)) method is widely regarded as the benchmark for precision in quantum chemistry [25].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Shifts the focus from wavefunctions to electron density, reducing computational demands while incorporating electron correlation through exchange-correlation functionals [25] [23]. This balance of cost and accuracy has led to DFT's widespread use for calculating ground-state properties of medium to large molecular systems [25].

Semiempirical quantum chemical methods occupy a middle ground, incorporating approximate integrals and parameterized elements to achieve significantly reduced computational cost, making them valuable for large-scale screening and geometry optimization [25].

Key Developments and Applications

Recent advances in quantum chemistry have enhanced the accuracy and applicability of these methods across chemical research. Improvements to DFT have addressed many of its shortcomings through the development of range-separated and double-hybrid functionals, along with empirical dispersion corrections such as DFT-D3 and DFT-D4 [25]. These refinements have extended DFT's applicability to non-covalent systems, transition states, and electronically excited configurations relevant to catalysis, photochemistry, and materials design [25].

The integration of machine learning with quantum methods has gained significant traction, enabling hybrid models that leverage physics-based approximations and data-driven corrections [25]. Recent developments such as GFN2-xTB offer broad applicability with significantly reduced computational cost [25]. Fragment-based and multi-scale quantum mechanical techniques like the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) approach and ONIOM provide practical strategies for handling large systems by enabling localized quantum treatments of subsystems within broader classical environments [25].

Quantum mechanical methods excel in determining electronic structure of complex molecules, studying photochemistry and excited states, and mapping chemical reaction mechanisms [25]. Techniques including time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT), complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF), and equation-of-motion coupled-cluster (EOM-CC) approaches offer detailed understanding of light-induced phenomena, electronic excitations, and relaxation processes [25]. These capabilities are central to materials development for applications in photovoltaics, photodynamic therapy, and molecular electronics.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Quantum Mechanical Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Computational Scaling | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Wavefunction theory, single Slater determinant | O(N⁴) | Fundamental reference method, physically meaningful orbitals | Neglects electron correlation, poor for dispersion |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron density, Hohenberg-Kohn theorems | O(N³) | Favourable cost/accuracy balance, good for geometries and frequencies | Functional dependence, challenges with dispersion and strong correlation |

| MP2 | Wavefunction theory, perturbation theory | O(N⁵) | Accounts for electron correlation, good for non-covalent interactions | Can overbind, sensitive to basis set |

| CCSD(T) | Wavefunction theory, coupled cluster | O(N⁷) | "Gold standard" for chemical accuracy | Prohibitive cost for large systems |

| Semiempirical Methods | Empirical parameterization, simplified integrals | O(N²-N³) | Very fast, applicable to very large systems | Parameter-dependent, transferability issues |

Molecular Mechanics Methods

Force Fields and Parametrization

Molecular mechanics (MM) provides a classical alternative to quantum mechanics by representing molecules as collections of atoms connected by springs, employing empirical potential functions known as force fields to describe the potential energy surface [25]. Unlike QM methods that explicitly treat electrons, MM methods describe molecular systems using a ball-and-spring model based on classical physics, making them computationally efficient for large systems but incapable of modeling bond formation or breaking.

The basic functional form of a typical molecular mechanics force field includes:

- Bond stretching: Described by harmonic potentials that model the energy required to stretch or compress bonds from their equilibrium values

- Angle bending: Represented by harmonic potentials for deviations from equilibrium bond angles

- Torsional potentials: Periodic functions that describe the energy associated with rotation around bonds

- Non-bonded interactions: Include van der Waals interactions (typically modeled by Lennard-Jones potentials) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law with partial atomic charges) [25]

Parameterization of force fields involves optimizing these potential functions and their parameters to reproduce experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations [25]. Popular force fields such as AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA are specifically parameterized for biomolecular simulations and have become standards in the field [23].

Applications and Limitations

Molecular mechanics methods, particularly when coupled with simulation techniques like molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo, provide efficient large-scale modeling of structural and energetic properties across diverse environments [25]. They enable the simulation of biomolecular systems with hundreds of thousands of atoms over microsecond to millisecond timescales, capturing essential conformational dynamics, ligand binding, and protein folding events that remain inaccessible to quantum methods.

Classical MD simulations provide crucial insights into dynamic processes, offering perspectives that complement experimental observations [29]. However, the accuracy of MM simulations is fundamentally limited by the quality of the force field and its inherent inability to describe electronic phenomena such as charge transfer, polarization effects, and chemical reactions [30]. These limitations restrict MM to applications where the electronic structure remains largely invariant, making them unsuitable for studying chemical reactivity, excitation processes, or systems where explicit electron effects are paramount.

Hybrid QM/MM Methodologies

Theoretical Foundations and Embedding Schemes

Hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methodologies represent a powerful multiscale approach that combines the strengths of both QM and MM methods [29]. These techniques partition the system into a small, chemically active region treated quantum mechanically (where bond formation/breaking or electronic excitations occur) and a larger environment described using molecular mechanics, thereby achieving quantum accuracy for the reactive center while maintaining computational efficiency for the full system [29].

The total energy in a QM/MM calculation is typically expressed as:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{QM}} + E{\text{MM}} + E{\text{QM/MM}} ]

where (E{\text{QM}}) is the energy of the quantum region, (E{\text{MM}}) is the energy of the classical region, and (E_{\text{QM/MM}}) represents the interaction between the two regions [29].

Three primary embedding schemes define how the QM and MM regions interact:

- Mechanical Embedding: The simplest approach where the QM region interacts with fixed MM charges via classical electrostatics, but the MM charges do not polarize the QM wavefunction [31]

- Electrostatic Embedding: The most common approach where the external potential from MM point charges acts on the QM subsystem and polarizes it, though typically without back-polarization of the MM subsystem [29]

- Polarized Embedding: More sophisticated approaches that allow mutual polarization between QM and MM regions, though these require polarizable force fields and are computationally more demanding

The selection of the QM/MM boundary in covalently bonded systems presents a significant challenge, often addressed through the use of link atoms or localized orbitals to saturate valencies [29].

Implementation and Accelerated Sampling

Implementing efficient QM/MM simulations requires addressing the significant computational cost of solving the QM problem at each MD step [29]. Several strategies have been developed to overcome this limitation:

- Enhanced Sampling Approaches: Techniques such as metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and replica-exchange MD accelerate rare-event observation by applying controlled biases to the system [29]

- Multiple Time Step (MTS) MD: Algorithms that propagate the more expensive QM calculations at larger time steps while treating faster MM motions with shorter steps [29]

- Performance-Optimized Frameworks: Simulation frameworks like MiMiC designed for computational performance and flexibility across diverse computing architectures [29]

Recent methodological advances include the development of adaptive QM/MM-NN MD methods that combine neural network predictions with iterative protocols to achieve ab initio QM/MM accuracy with significantly reduced computational cost [30]. These methods perform direct MD simulations on a neural network-predicted potential energy surface that approximates the ab initio QM/MM potential, with adaptive updates to the network when new configurations are encountered during sampling [30].

Adaptive QM/MM-NN MD Workflow: This iterative protocol combines neural network predictions with high-level QM calculations to achieve accurate sampling at reduced cost [30].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Approaches

ML Potentials and Hierarchical Learning

Machine learning has emerged as a transformative element in computational chemistry, enabling the development of data-driven tools that identify molecular features correlated with target properties, thereby accelerating discovery while minimizing trial-and-error experimentation [25] [32]. ML potentials trained on quantum mechanical data can achieve near-quantum accuracy at significantly reduced computational cost, addressing the sampling limitations of direct QM/MM simulations.

A particularly powerful approach involves hierarchical machine learning frameworks that systematically distill knowledge from high-fidelity quantum calculations into increasingly efficient, machine-learned quantum Hamiltonians [32]. This hierarchical structure typically follows three stages:

- High-Level Wavefunction Data Generation: Using accurate methods like local coupled cluster theory (LNO-CCSD(T)) to generate reference energies and forces for a limited set of configurations [32]

- Intermediate-Level DFT Parametrization: Training a custom-parameterized density functional to reproduce the high-level reference data [32]

- Efficient ML Potential Development: Using the DFT data to train highly efficient machine-learned semi-empirical quantum models that retain explicit electronic degrees of freedom [32]

By retaining explicit electronic degrees of freedom, this approach enables faithful embedding of quantum and classical degrees of freedom that captures long-range electrostatics and the quantum response to a classical environment [32].

ML/MM Paradigm and Emerging Directions

The integration of machine learning with multiscale modeling has given rise to the ML/MM paradigm, which extends the classical QM/MM approach by replacing the quantum description with neural network potentials trained to reproduce quantum-mechanical results [31]. This approach achieves near-QM/MM fidelity at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling routine simulation of reaction mechanisms, vibrational spectra, and binding free energies in complex biological or condensed-phase environments [31].

Three primary strategies have emerged for coupling ML and MM regions:

- Mechanical Embedding (ME): ML regions interact with fixed MM charges via classical electrostatics [31]

- Polarization-Corrected Mechanical Embedding (PCME): A vacuum-trained ML potential supplemented with electrostatic corrections, preserving transferability while approximating environment effects [31]

- Environment-Integrated Embedding (EIE): ML potentials trained with explicit inclusion of MM-derived fields, enhancing accuracy but requiring specialized data [31]

Table 2: ML-Enhanced Computational Methods and Applications

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Key Innovations | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials | Behler-Parrinello, ANI, MACE | High-dimensional NN with symmetry functions | Reactive processes in condensed phase, nanoparticle catalysis |

| Δ-Machine Learning | Kernel-based Δ-learning, transfer learning | Learning difference between low and high-level QM | Reaction barrier refinement, spectroscopy prediction |

| Hierarchical Hamiltonian Learning | Differentiable SEQM, ML-xTB | Systematic coarse-graining of quantum Hamiltonians | pKa prediction, enzymatic reaction kinetics [32] |

| ML/MM Frameworks | Polarization-corrected embedding, environment-integrated models | Neural potentials with embedded MM electrostatics | Binding free energies, vibrational spectra in proteins [31] |

Quantum computing represents another frontier for computational chemistry, with algorithms such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) being developed to address electronic structure problems more efficiently than classical computing [25] [27]. Recent demonstrations include multicomponent quantum simulations beyond the Born-Oppenheimer approximation using the nuclear-electronic orbital framework, enabling correlated treatment of both electronic and nuclear quantum effects [27].

Research Applications and Protocols

Case Study: Enzyme Catalysis and Drug Design

QM/MM methodologies have provided transformative insights into enzymatic reaction mechanisms and drug design strategies. In biomedical applications, these approaches have elucidated the covalent binding mechanisms of transition metal-based anticancer drugs targeting biological systems [29]. For instance, QM/MM MD simulations have revealed the activation pathways and binding modes of ruthenium-based compounds, informing the rational design of targeted cancer therapeutics with reduced side effects [29].

In industrial biocatalysis, QM/MM simulations guide the design of artificial enzymes for environmentally significant reactions. The development of artificial metalloenzymes often involves QM/MM investigation of reaction pathways and barrier heights, enabling computational screening of protein scaffolds and metal cofactors before experimental validation [29]. These approaches have successfully predicted mutation effects on catalytic efficiency and selectivity, accelerating the engineering of biocatalysts for chemical manufacturing.

Experimental Protocol: QM/MM Free Energy Simulation

The following protocol outlines a typical workflow for conducting QM/MM free energy simulations of chemical reactions in condensed phase or enzymatic environments:

System Preparation

- Obtain initial coordinates from crystallographic data or homology modeling

- Solvate the system in appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add counterions to neutralize charge

- Employ MM force fields (e.g., AMBER ff14SB for proteins, GAFF for small molecules) for classical regions

- Partition the system into QM and MM regions, selecting the chemically active core (typically 50-200 atoms) for QM treatment

Equilibration and Sampling

- Perform classical MD equilibration with positional restraints on reactive core

- Conduct enhanced sampling simulations (e.g., umbrella sampling, metadynamics) along predefined reaction coordinates using semiempirical QM/MM or ML/MM potentials

- Collect 20-50 configurations from the reaction path for high-level single-point calculations

High-Level Refinement

- Execute single-point energy calculations at each sampled configuration using high-level QM/MM (e.g., DFT/CCSD(T) with electrostatic embedding)

- Apply free energy perturbation or umbrella integration to compute potential of mean force

- Validate convergence through block averaging and statistical error analysis