Beyond the Similarity Principle: A Critical Assessment of Molecular Similarity Metrics for Machine Learning in Drug Discovery

Molecular similarity, the foundational principle that similar structures confer similar properties, is the backbone of modern machine learning (ML) in chemistry and drug discovery.

Beyond the Similarity Principle: A Critical Assessment of Molecular Similarity Metrics for Machine Learning in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Molecular similarity, the foundational principle that similar structures confer similar properties, is the backbone of modern machine learning (ML) in chemistry and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive assessment of molecular similarity metrics, exploring their theoretical foundations, diverse methodological implementations, and critical applications in predictive modeling. We delve into significant challenges, including the pervasive issue of activity cliffs that cause model failures and the coverage biases in public datasets that limit model generalizability. By comparing traditional fingerprint-based methods with advanced approaches and presenting established validation frameworks like MoleculeACE, this review equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select, optimize, and critically evaluate similarity metrics for robust and reliable ML-driven innovation.

The Bedrock of Cheminformatics: Deconstructing the Principles and Paradoxes of Molecular Similarity

The concept of similarity serves as a foundational pillar across scientific disciplines, from organizing historical knowledge to powering modern machine learning (ML) systems. In the history of science, similarity assessments allowed scholars to categorize astronomical tables and track the dissemination of mathematical knowledge across early modern Europe [1]. Today, this principle has evolved into sophisticated computational approaches that measure similarity between molecules, texts, and user preferences, forming the core of recommendation systems, drug discovery pipelines, and data curation frameworks [2] [3] [4].

The evaluation of molecular similarity metrics represents a particularly critical application in machine learning research for drug development. These metrics serve as the backbone for both supervised and unsupervised ML procedures in chemistry, enabling researchers to navigate vast chemical spaces, predict compound properties, and identify promising drug candidates [4]. As pharmaceutical research enters a data-intensive paradigm, the choice of appropriate similarity measures has become increasingly consequential for reducing drug discovery timelines and improving success rates [5] [6] [7].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of molecular similarity metrics and their applications in modern ML-driven drug discovery, offering experimental insights and methodological protocols to inform researchers' selection of appropriate similarity frameworks for specific research contexts.

Theoretical Foundations of Similarity Measurement

Similarity learning encompasses a family of machine learning approaches dedicated to learning a similarity function that quantifies how similar or related two objects are [2]. In the context of molecular science, this translates to developing metrics that can accurately capture chemical relationships that correlate with biological activity, pharmacokinetic properties, or synthetic accessibility.

Key Similarity Learning Frameworks

The theoretical underpinnings of similarity measurement can be categorized into several distinct paradigms, each with specific characteristics and applications relevant to drug discovery:

Classification Similarity Learning: This approach utilizes pairs of similar objects $(xi, xi^+)$ and dissimilar objects $(xi, xi^-)$ to learn a similarity function, effectively framing similarity as a classification problem where the model learns to distinguish between similar and dissimilar pairs [2].

Regression Similarity Learning: In this framework, pairs of objects $(xi^1, xi^2)$ are presented with continuous similarity scores $yi ∈ R$, allowing the model to learn a function $f(xi^1, xi^2) ∼ yi$ that approximates these similarity ratings [2].

Ranking Similarity Learning: Given triplets of objects $(xi, xi^+, xi^-)$, where $xi$ is more similar to $xi^+$ than to $xi^-$, the model learns a similarity function $f$ that satisfies $f(x, x^+) > f(x, x^-)$ for all triplets [2].

Metric Learning: A specialized form of similarity learning that focuses on learning distance metrics obeying specific mathematical properties, particularly the triangle inequality. Mahalanobis distance learning represents a common approach in this category, where a matrix $W$ parameterizes the distance function $DW(x1, x2)^2 = (x1-x2)^⊤ W(x1-x_2)$ [2].

Table 1: Similarity Learning Frameworks and Their Drug Discovery Applications

| Framework | Mathematical Formulation | Primary Drug Discovery Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Classification Similarity | Learns from similar/dissimilar pairs | Compound clustering, activity prediction |

| Regression Similarity | $f(xi^1, xi^2) ∼ y_i$ | Quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR) |

| Ranking Similarity | $f(x, x^+) > f(x, x^-)$ | Lead optimization, virtual screening |

| Metric Learning | $DW(x1, x2)^2 = (x1-x2)^⊤ W(x1-x_2)$ | Chemical space navigation, library design |

Molecular Representations for Similarity Assessment

The effectiveness of any similarity metric depends heavily on the molecular representation employed. Different representations capture distinct aspects of chemical structure and properties, making them suitable for different stages of the drug discovery pipeline:

Structural Fingerprints: Binary vectors indicating the presence or absence of specific substructures or chemical patterns, such as ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints) or MACCS keys, enabling rapid similarity computation through Tanimoto coefficients [4].

Physicochemical Descriptors: Continuous vectors encoding molecular properties like logP, molecular weight, polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and topological indices, which capture property-based relationships beyond structural similarity.

3D Pharmacophore Features: Spatial representations of functional groups and their relative orientations, critical for measuring similarity in structure-based drug design where molecular shape and electrostatic complementarity determine biological activity.

Learned Representations: Embeddings generated by deep learning models such as graph neural networks or autoencoders, which automatically discover relevant features from molecular structures or bioactivity data [6] [7].

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Similarity Metrics

The selection of an appropriate similarity metric significantly impacts the success of virtual screening campaigns, compound prioritization, and scaffold hopping initiatives. The following comparison synthesizes experimental findings from multiple studies to guide metric selection.

Performance Comparison Across Metric Classes

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Molecular Similarity Metrics on Benchmark Datasets

| Similarity Metric | Molecule Representation | Virtual Screening EF₁% | Scaffold Hopping Success Rate | Computational Complexity | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanimoto Coefficient | ECFP4 fingerprints | 32.5 ± 4.2 | 28.7 ± 3.5 | O(n) | High |

| Cosine Similarity | Physicochemical descriptors | 28.3 ± 3.8 | 22.4 ± 3.1 | O(n) | Medium |

| Mahalanobis Distance | Learned representations | 35.2 ± 4.5 | 31.8 ± 4.0 | O(n²) | Low |

| Neural Similarity | Graph embeddings | 37.8 ± 4.7 | 34.2 ± 4.3 | O(n) | Low |

| Tversky Index | ECFP4 fingerprints | 30.1 ± 4.0 | 29.5 ± 3.8 | O(n) | High |

Experimental data compiled from published studies reveals that neural embedding-based similarity metrics generally outperform traditional fingerprint-based approaches in both virtual screening enrichment factors (EF₁%) and scaffold hopping success rates, though at the cost of interpretability [4] [7]. The Tanimoto coefficient maintains competitive performance with high interpretability, making it suitable for initial screening phases where understanding structural relationships is crucial.

Context-Dependent Metric Performance

The relative performance of similarity metrics varies significantly across different drug discovery contexts and target classes:

GPCR-Targeted Compounds: Neural embedding approaches demonstrated 15.3% higher enrichment factors compared to Tanimoto similarity in retrospective screening studies, likely due to their ability to capture complex pharmacophoric relationships beyond structural similarity [7].

Kinase Inhibitors: Tversky-index-based similarity with asymmetric parameters (α=0.7, β=0.3) outperformed symmetric similarity measures by 12.7% in scaffold hopping experiments, effectively identifying structurally diverse compounds with conserved binding motifs.

CNS-Targeted Compounds: Property-weighted similarity metrics incorporating physicochemical descriptors showed superior performance in predicting blood-brain barrier penetration, with a 22.4% improvement over structure-only similarity measures.

Experimental Protocols for Similarity Metric Evaluation

Robust evaluation methodologies are essential for assessing the performance of similarity metrics in drug discovery applications. The following protocols provide standardized frameworks for metric comparison.

Virtual Screening Validation Protocol

This protocol evaluates the ability of similarity metrics to identify active compounds through retrospective screening simulations:

Data Curation: Compile a benchmark dataset containing known active compounds and decoy molecules with verified inactivity against the target of interest. The Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) and DUD-E datasets provide standardized resources for this purpose.

Similarity Calculation: For each active compound (query), compute similarity scores against all other actives and decoys using the metric under evaluation.

Enrichment Analysis: Rank the database compounds by decreasing similarity to each query and calculate enrichment factors (EF) at specific percentiles of the screened database (typically EF₁% and EF₅%).

Statistical Analysis: Perform significance testing across multiple query compounds to determine metric performance, using paired t-tests or non-parametric alternatives to compare different metrics.

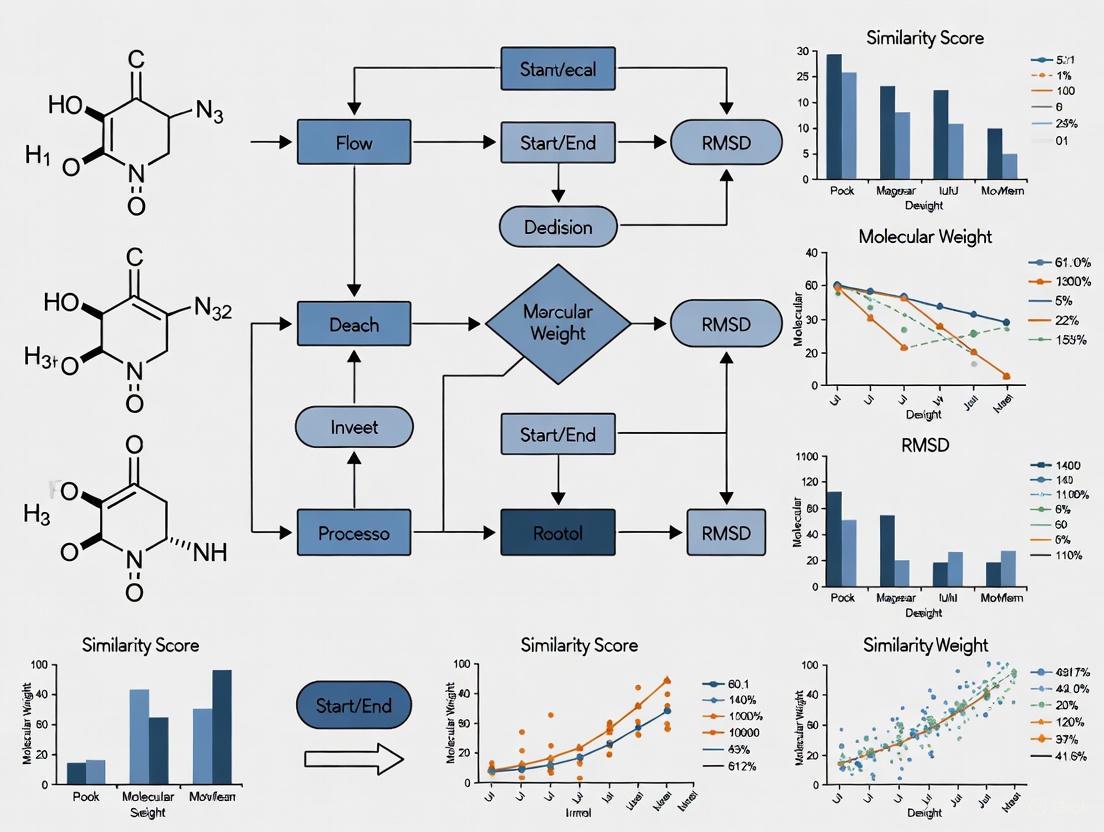

Virtual Screening Validation Workflow

Scaffold Hopping Evaluation Protocol

This protocol assesses a similarity metric's ability to identify structurally diverse compounds with similar biological activity:

Scaffold Definition: Apply the Bemis-Murcko method to decompose compounds into core scaffolds and side chains.

Query Selection: Select query compounds representing distinct scaffold classes with verified activity against the target.

Similarity Search: For each query, perform similarity searches against a database containing multiple scaffold classes.

Success Assessment: Calculate the scaffold hopping success rate as the percentage of queries for which the top-k most similar compounds contain at least one different scaffold with confirmed activity.

Scaffold Hopping Evaluation Workflow

Data Curation Similarity Assessment

Recent advances in language model pretraining have demonstrated that specialized similarity metrics tailored to specific data distributions outperform generic off-the-shelf embeddings [8]. This principle translates directly to molecular data curation, where task-specific similarity measures improve compound selection for targeted screening libraries:

Embedding Generation: Compute molecular embeddings using both generic chemical representation models and task-specific models trained on relevant bioactivity data.

Similarity Correlation: Assess how well distances in embedding space correlate with bioactivity similarity using Pearson correlation coefficients.

Cluster Validation: Apply balanced K-means clustering in embedding space and measure within-cluster variance of bioactivity values.

Performance Benchmark: Evaluate embedding quality by training predictive models on clusters and measuring extrapolation accuracy to unseen structural classes.

Successful implementation of similarity-based drug discovery requires carefully selected computational tools and databases. The following table catalogues essential resources for constructing and evaluating molecular similarity pipelines.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Molecular Similarity Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC | Source of compound structures and bioactivity data | Publicly available |

| Fingerprint Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, CDK | Generation of molecular fingerprints and descriptors | Open source |

| Similarity Algorithms | metric-learn, OpenMetricLearning | Implementation of metric learning algorithms | Open source Python libraries |

| Benchmark Datasets | DUD-E, MUV, LIT-PCBA | Validated datasets for virtual screening evaluation | Publicly available |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | DeepChem, PyTorch Geometric | Neural similarity learning implementation | Open source |

| Visualization Tools | ChemPlot, TMAP, RDKit | Visualization of chemical space and similarity relationships | Open source |

Future Perspectives in Molecular Similarity Research

The field of molecular similarity continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in artificial intelligence and the increasing availability of high-quality chemical and biological data. Several emerging trends are poised to shape the next generation of similarity metrics and their applications in drug discovery:

Multi-scale Similarity Integration: Future metrics will likely incorporate similarity across biological scales, combining molecular structure with phenotypic readouts, gene expression profiles, and clinical outcomes to create more predictive similarity frameworks [5] [6].

Transferable Metric Learning: Approaches that learn similarity metrics transferable across target classes and therapeutic areas will reduce the data requirements for successful implementation in novel drug discovery programs.

Explainable Similarity Assessment: As deep learning-based similarity metrics gain adoption, methods for interpreting and explaining similarity assessments will become increasingly important for building trust and extracting chemical insights [6].

Federated Similarity Learning: Privacy-preserving approaches that learn effective similarity metrics across distributed data sources without centralization will enable collaboration while protecting proprietary chemical information.

The similarity principle, though ancient in its conceptual roots, continues to find new expressions in data-intensive machine learning paradigms. As drug discovery confronts increasing complexity and escalating data volumes, sophisticated similarity assessment frameworks will play an ever more central role in translating chemical information into therapeutic breakthroughs.

In modern chemical research and drug development, quantifying molecular structures into computer-readable formats is a fundamental prerequisite for the application of machine learning (ML). Molecular fingerprints and descriptors serve as the foundational language that enables machines to "understand" chemical structures, transforming molecules into numerical vectors that capture key structural and physicochemical characteristics. Within the broader thesis of assessing molecular similarity metrics in ML research, these representations form the computational backbone for tasks ranging from virtual screening and property prediction to chemical space mapping [4].

The critical distinction in this domain lies between molecular fingerprints, which are typically binary bit strings indicating the presence or absence of specific substructures or patterns, and molecular descriptors, which are numerical values representing quantifiable physicochemical properties. While both aim to encode molecular information, their underlying philosophies and applications differ significantly. Fingerprints excel at capturing structural similarities through pattern matching, whereas descriptors provide a more direct representation of physicochemical properties that influence molecular behavior and interactions [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform selection criteria for research applications.

Molecular Fingerprints: Structural Keys for Similarity Search

Core Concepts and Typology

Molecular fingerprints function as structural keys that encode molecular topology into fixed-length vectors. Three predominant fingerprint types emerge from the literature:

- Circular Fingerprints (Morgan/ECFP): Generate atom environments by iteratively applying a circular neighborhood around each atom, capturing increasing radial diameters. ECFP4 (with a radius of 2 bonds) is considered the gold standard for small molecule applications [10] [9].

- Substructure Key-Based Fingerprints (MACCS): Employ predefined dictionaries of chemical substructures (typically 166 or 960 keys), where each bit represents the presence or absence of a specific functional group or structural pattern [9].

- Atom-Pair Fingerprints: Encode the topological distance between all atom pairs in a molecule, providing superior perception of molecular shape and global features, making them particularly suitable for larger molecules like peptides [11].

Advanced and Hybrid Fingerprints

Recent research has developed next-generation fingerprints that address limitations of traditional approaches:

- MAP4 (MinHashed Atom-Pair fingerprint): A hybrid fingerprint that combines substructure and atom-pair concepts by representing atom pairs with their circular substructures up to a diameter of four bonds. MAP4 significantly outperforms other fingerprints on an extended benchmark combining small molecules and peptides, achieving what the developers term a "universal fingerprint" suitable for drugs, biomolecules, and the metabolome [11].

- MHFP6 (MinHashed Fingerprint): Uses the MinHashing technique from natural language processing to create a fingerprint that enables fast similarity searches in very large databases through locality-sensitive hashing [11].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Molecular Fingerprint Types

| Fingerprint Type | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Cases | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan (ECFP4) | Circular structure, radius-based atom environments | Small molecule virtual screening, QSAR | AUROC 0.828 for odor prediction [10] |

| MACCS | Predefined structural keys, interpretable | Rapid similarity screening, functional group detection | -- |

| Atom-Pair | Topological distances, shape-aware | Scaffold hopping, peptide analysis | Superior for biomolecules [11] |

| MAP4 | Hybrid atom-pair + substructure, MinHashed | Cross-domain applications (drugs to biomolecules) | Outperforms ECFP4 on small molecules & peptides [11] |

Molecular Descriptors: Quantifying Physicochemical Properties

Descriptor Classes and Applications

Molecular descriptors provide a more direct quantification of physicochemical properties, typically categorized by dimensionality:

- 1D Descriptors: Bulk properties including molecular weight, heavy atom count, number of rotatable bonds, and hydrogen bond donors/acceptors.

- 2D Descriptors: Topological descriptors derived from molecular graph representation, such as molecular connectivity indices, topological polar surface area (TPSA), and molecular refractivity.

- 3D Descriptors: Geometrical descriptors requiring 3D molecular structure, including solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), principal moments of inertia, and dipole moments [9].

Experimental comparisons consistently demonstrate that traditional 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors can produce superior models for specific ADME-Tox prediction tasks compared to fingerprint-based approaches, with 2D descriptors showing particularly strong performance across multiple targets [9].

Dynamic Properties from Molecular Simulations

Beyond static descriptors, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide dynamic properties that offer profound insights into molecular behavior:

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Quantifies the surface area of a molecule accessible to a solvent probe.

- Coulombic and Lennard-Jones Interaction Energies: Capture electrostatic and van der Waals interactions between solutes and solvents.

- Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv): Measure the energy change associated with solvation.

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Quantifies conformational flexibility and stability [12].

Research demonstrates that MD-derived properties combined with traditional descriptors like logP can achieve exceptional predictive performance for aqueous solubility (R² = 0.87 using Gradient Boosting algorithms) [12].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Benchmarks

Odor Prediction Benchmark

A comprehensive 2025 study compared molecular representations for odor prediction using a curated dataset of 8,681 compounds. The research benchmarked functional group (FG) fingerprints, classical molecular descriptors (MD), and Morgan structural fingerprints (ST) across Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) algorithms [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Odor Prediction (AUROC/AUPRC) [10]

| Model Configuration | Random Forest | XGBoost | LightGBM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Group (FG) | 0.753 / 0.088 | 0.753 / 0.088 | -- |

| Molecular Descriptors (MD) | 0.802 / 0.200 | 0.802 / 0.200 | -- |

| Morgan Fingerprint (ST) | 0.784 / 0.216 | 0.828 / 0.237 | 0.810 / 0.228 |

The Morgan-fingerprint-based XGBoost model achieved the highest discrimination, demonstrating the superior representational capacity of topological fingerprints to capture olfactory cues. Five-fold cross-validation confirmed the robustness of these findings, with ST-XGB maintaining superior performance (mean AUROC 0.816, AUPRC 0.226) [10].

ADME-Tox Prediction Benchmark

A detailed 2022 comparison examined descriptor and fingerprint performance across six ADME-Tox targets: Ames mutagenicity, P-glycoprotein inhibition, hERG inhibition, hepatotoxicity, blood-brain-barrier permeability, and cytochrome P450 2C9 inhibition. The study evaluated Morgan, AtomPair, and MACCS fingerprints alongside traditional 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors using XGBoost and RPropMLP neural networks [9].

The results demonstrated that traditional 2D descriptors consistently produced superior models for almost every dataset, even outperforming the combination of all examined descriptor sets. This surprising finding challenges the assumption that more complex representations necessarily yield better performance and highlights the importance of representation selection based on specific prediction targets [9].

Methodology: Experimental Protocols for Representation Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

The experimental methodology for comparing molecular representations follows a rigorous, standardized protocol:

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

Robust evaluation requires carefully curated datasets with standardized preprocessing:

- Data Sources: Unified datasets from multiple expert sources (e.g., 10 sources for odor study yielding 8,681 compounds) [10]

- Structure Standardization: Canonicalization of SMILES representations, removal of salts, neutralization of charges, and generation of canonical tautomers

- Descriptor Standardization: Elimination of constant and highly correlated descriptors to reduce dimensionality and avoid model bias [9]

- Data Splitting: Stratified train/test splits (typically 80:20) maintaining class distribution, with cross-validation (5-fold common) for robust performance estimation [10]

Molecular Representation Generation

Fingerprint Generation:

- Morgan fingerprints computed using RDKit with specified radius (typically radius=2 for ECFP4) [10]

- Atom-pair fingerprints encoding topological distances between all atom pairs

- MACCS fingerprints using predefined structural keys

- Advanced fingerprints like MAP4 combining atom-pair approach with circular substructures [11]

Descriptor Calculation:

- 1D/2D descriptors computed using cheminformatics toolkits (RDKit, CDK)

- 3D descriptors requiring geometry optimization (e.g., with Schrödinger Macromodel) [9]

- MD-derived properties extracted from molecular dynamics simulations using packages like GROMACS [12]

Model Training and Evaluation Metrics

Consistent evaluation employs multiple algorithms with comprehensive metrics:

- Algorithms: Tree-based methods (Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM) particularly effective for structural data [10] [9]

- Evaluation Metrics: AUROC (Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic), AUPRC (Area Under Precision-Recall Curve), accuracy, specificity, precision, recall [10]

- Validation: Stratified k-fold cross-validation with maintenance of positive:negative ratios within each fold [10]

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Representation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation, molecular manipulation | Standard workflow for molecular representation [10] [9] |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial Software | 3D structure optimization, molecular dynamics simulations | High-quality 3D descriptor generation [9] |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Engine | MD simulation for dynamic property calculation | Deriving solvation and interaction properties [12] |

| PubChem | Chemical Database | Compound structures, bioactivity data, CID to SMILES conversion | Data source for benchmarking datasets [10] |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting implementation for structured data | Primary algorithm for QSPR model development [10] [9] |

The experimental evidence demonstrates that molecular representation selection significantly impacts model performance, with no universal "best" approach across all applications. Strategic selection should consider:

- Small Molecule Drug Discovery: Morgan fingerprints (ECFP4) generally excel for typical small molecules within Lipinski space, particularly combined with XGBoost algorithms [10].

- ADME-Tox Prediction: Traditional 2D descriptors frequently outperform fingerprints for specific physiological property predictions [9].

- Biomolecules and Peptides: Atom-pair fingerprints or hybrid approaches like MAP4 provide superior performance for larger molecules [11].

- Solubility and Physicochemical Properties: MD-derived properties combined with traditional descriptors offer enhanced predictive power for complex physicochemical properties [12].

The evolving landscape of molecular representation continues to advance with hybrid approaches like MAP4 and learned representations from graph neural networks showing promise for universal application across chemical domains. As molecular similarity metrics remain fundamental to chemical AI, thoughtful selection of appropriate representations based on specific research contexts will continue to be essential for maximizing predictive performance in drug discovery and materials science.

In the field of computational chemistry and drug discovery, the concept of molecular similarity serves as a fundamental principle underpinning various workflows, from virtual screening to structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis. The Similarity Property Principle—which posits that structurally similar molecules tend to have similar properties—is a cornerstone of rational drug design [13] [14]. However, the computational implementation of this principle heavily depends on how molecules are represented and compared. Molecular fingerprints, which encode structural or chemical features as fixed-length vectors, provide a systematic approach for quantifying similarity [13]. These representations primarily fall into two categories with distinct philosophical and practical differences: substructure-preserving fingerprints and feature-based fingerprints.

Substructure-preserving methodologies prioritize the explicit conservation of molecular topology and fragment information, making them ideal for applications where structural integrity and chemical interpretability are paramount. In contrast, feature-based fingerprints employ abstraction to capture higher-level chemical patterns and pharmacophoric properties that often correlate more strongly with biological activity [13] [15]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and practical implementation protocols, to assist researchers in selecting appropriate molecular representations for their specific applications in machine learning and drug development.

Fundamental Principles: Characteristics of Fingerprint Methodologies

Substructure-Preserving Fingerprints

Substructure-preserving fingerprints are dictionary-based representations that use a predefined library of structural patterns, assigning binary bits to represent the presence or absence of these specific patterns [13]. These methodologies explicitly conserve molecular topology, making them inherently interpretable and valuable for substructure searches.

- Linear Path-Based Hashed Fingerprints: These exhaustively identify all linear paths in a molecule up to a predefined length (typically 5-7 bond paths), with ring systems represented by type and size attributes. The Chemical Hashed Fingerprint (CFP) is a prominent example, generating patterns through a hashing process that maps structural features to bit positions [13].

- Common Implementations: Popular structural fingerprints include PubChem (PC), Molecular ACCess System (MACCS), Barnard Chemistry Information (BCI) fingerprints, and SMILES FingerPrint (SMIFP) [13].

- Key Characteristics: These fingerprints maintain a direct correspondence between bit positions and specific structural features, providing clear chemical interpretability. However, this explicit representation may limit their ability to capture activity-relevant similarities between structurally distinct compounds.

Feature-Based Fingerprints

Feature-based fingerprints sacrifice explicit structural preservation to encode higher-level chemical characteristics that correspond to key structure-activity properties in known compounds [13]. These representations are non-substructure preserving but often provide better vectors for machine learning and activity-based virtual screening.

- Radial (Circular) Fingerprints: The Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) represents the most common radial fingerprint. It starts from each heavy atom and expands outward to a given diameter, generating patterns hashed using a modified Morgan algorithm [13]. These fingerprints capture local atomic environments progressively, creating increasingly larger circular substructures.

- Topological Fingerprints: These represent graph distance within a molecule, with Atom Pair fingerprints encoding the shortest topological distance between two atoms [13]. Topological Torsions represent linear sequences of connected atoms and bonds, capturing local stereochemical environments.

- Specialized Variants: Advanced feature fingerprints include Pharmacophore fingerprints that incorporate physchem properties to predict molecular interactions, and Shape-based fingerprints that describe 3D molecular surfaces [13].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Fingerprint Methodologies

| Characteristic | Substructure-Preserving Fingerprints | Feature-Based Fingerprints |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Explicit structural conservation | Activity-relevant pattern recognition |

| Representation Basis | Predefined structural keys/linear paths | Atomic environments/topological patterns |

| Chemical Interpretability | Direct structure-bit correspondence | Abstract feature-bit relationship |

| Optimal Application | Substructure search, SAR analysis | Virtual screening, ML model building |

| Common Examples | MACCS, PubChem, CFP | ECFP, FCFP, Atom Pairs, Topological Torsions |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmark Results

Quantitative Performance Across Similarity Tasks

Experimental benchmarks reveal that fingerprint performance varies significantly depending on the similarity task, particularly when distinguishing between close structural analogs versus more diverse compounds. A comprehensive evaluation of 28 different fingerprints using literature-based similarity benchmarks demonstrated these contextual performance patterns [14].

- Close Analog Ranking: When ranking very similar structures within congeneric series, the Atom Pair fingerprint demonstrated superior performance, outperforming circular fingerprints in identifying minimal structural variations that maintain core scaffold similarity [14].

- Diverse Structure Ranking: For ranking more structurally diverse compounds, Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP4 and ECFP6) and Topological Torsion fingerprints consistently ranked among the best performers, effectively capturing broader chemical similarities beyond close analogs [14].

- Virtual Screening Applications: In ligand-based virtual screening benchmarks, ECFP4 fingerprints demonstrated strong performance, though their effectiveness significantly improved when bit-vector length was increased from 1,024 to 16,384 bits, reducing the impact of bit collisions on similarity calculations [14].

Table 2: Fingerprint Performance Across Different Similarity Tasks

| Fingerprint Type | Close Analog Ranking | Diverse Structure Ranking | Virtual Screening | Optimal Bit Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | Moderate | Excellent | Excellent | 16,384 |

| ECFP6 | Moderate | Excellent | Good | 16,384 |

| Atom Pairs | Excellent | Good | Moderate | 1,024 |

| Topological Torsions | Good | Excellent | Good | 1,024 |

| MACCS | Good | Moderate | Moderate | 166-960 |

| CFP (Path-based) | Good | Good | Moderate | 1,024-16,384 |

Impact on Machine Learning and Explainability

The choice of molecular representation significantly influences both model performance and interpretability in machine learning applications for drug discovery. Recent research has demonstrated that integrating multiple graph representations—including atom-level, pharmacophore, and functional group graphs—can enhance both prediction accuracy and model explainability [15].

- Model Performance: Studies using the MMGX (Multiple Molecular Graph eXplainable discovery) framework have shown that employing multiple molecular graph representations relatively improves model performance, though the degree of improvement varies depending on the specific dataset and task [15].

- Interpretation Quality: Interpretation from multiple graph representations provides more comprehensive features and identifies potential substructures consistent with background knowledge, offering valuable insights for subsequent drug discovery tasks [15].

- Explainability Challenges: Standard Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have demonstrated limitations in explainability performance compared to simpler methods like Random Forests with atom masking. Incorporating scaffold-aware loss functions that explicitly consider common core structures between molecular pairs has shown promise in improving GNN explainability for lead optimization applications [16].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Fingerprint Evaluation

Benchmark Dataset Construction

Robust evaluation of fingerprint performance requires carefully constructed benchmark datasets that reflect real-world application scenarios. The following protocols represent established methodologies for generating meaningful performance assessments.

Literature-Based Similarity Benchmark: This approach creates benchmark datasets from medicinal chemistry literature by assuming that molecules appearing in the same compound activity table were considered structurally similar by medicinal chemists [14]. The protocol involves:

- Extracting compounds from the same activity table in ChEMBL as similar pairs

- Creating a "single-assay" benchmark with very similar structures from the same assay

- Generating a "multi-assay" benchmark with more diverse structures linked through common molecules across different papers

- Assuming that similarity decreases through series linkages (M1→M3→M5→M7→M9) due to chemical space expansion

Activity Cliff-Based Explainability Benchmark: This methodology evaluates feature attribution accuracy using activity cliffs—pairs of compounds sharing a molecular scaffold with significant activity differences [16]:

- Identify compound pairs with maximum common substructure (MCS) exceeding a threshold (e.g., 50%)

- Select pairs with activity differences >1 log unit

- Use the uncommon structural motifs as ground truth for feature importance

- Evaluate attribution methods on their ability to identify these key substructures

Performance Quantification Methods

Standardized evaluation metrics enable direct comparison between different fingerprint methodologies across various applications.

Similarity Search Metrics: For benchmarking similarity ranking performance:

- Use a reference molecule and rank others by similarity using Tanimoto coefficient

- Compare against ground truth similarity ordering from benchmark datasets

- Calculate Spearman correlation between computational and ground truth rankings

- Assess statistical significance of performance differences using appropriate tests

Virtual Screening Metrics: For evaluating actives retrieval efficiency [14]:

- Use single active compound as query against database containing actives and decoys

- Calculate enrichment factors (EF) at early recovery levels (e.g., EF1%, EF5%)

- Compute area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC)

- Employ significance testing to distinguish performance between fingerprints

Explainability Evaluation: For assessing interpretation accuracy [16]:

- Compare feature attributions against ground truth important substructures

- Calculate precision and recall for important atom identification

- Use F1-score as balanced metric of explanation accuracy

- Evaluate across multiple targets and activity cliff types

Decision Framework: Selecting Appropriate Fingerprint Methodologies

The optimal fingerprint choice depends on the specific research objective, chemical space characteristics, and desired outcome. The following decision framework provides guidance for selecting appropriate molecular representations.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementation of fingerprint-based similarity analysis requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key research reagents and their applications in molecular similarity assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Fingerprint generation, similarity calculation | General-purpose cheminformatics, method development |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity Database | Benchmark dataset source, activity data | Validation, ground truth establishment |

| ChemAxon JChem | Commercial Cheminformatics | Fingerprint generation, chemical representation | Pharmaceutical research, proprietary databases |

| BindingDB | Binding Affinity Database | Protein-ligand activity data | Explainability benchmarking, activity cliffs |

| MACCS Keys | Structural Fingerprint | 166-960 predefined structural fragments | Substructure search, rapid similarity assessment |

| ECFP/FCFP | Feature Fingerprint | Circular atomic environments | Virtual screening, ML feature engineering |

| Atom Pair | Topological Fingerprint | Atom-type pairs with distances | Close analog searching, scaffold hopping |

| Topological Torsions | Topological Fingerprint | Bond sequences with torsion angles | 3D similarity, conformational analysis |

The comparative analysis of structural versus feature-based fingerprints reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological advantages are strongly context-dependent. Substructure-preserving fingerprints provide superior performance for applications requiring explicit structural conservation and interpretability, such as SAR analysis and close analog searching. Conversely, feature-based fingerprints excel in virtual screening and machine learning applications where activity-relevant pattern recognition outweighs the need for structural interpretability.

Emerging methodologies point toward hybrid approaches that leverage multiple molecular representations simultaneously. The MMGX framework demonstrates that combining atom-level, pharmacophore, and functional group graphs can enhance both prediction accuracy and model interpretation [15]. Similarly, scaffold-aware loss functions for GNNs address explainability limitations while maintaining predictive performance for lead optimization applications [16].

Future developments in molecular similarity assessment will likely focus on task-adaptive representations that dynamically optimize fingerprint selection based on specific research objectives and chemical space characteristics. As artificial intelligence continues transforming drug discovery, the integration of sophisticated molecular representations with explainable AI frameworks will be crucial for building researcher trust and facilitating scientific discovery.

Similarity, Distance, and Dissimilarity: Defining Key Metrics (Tanimoto, Dice, Euclidean, Tversky)

The assessment of molecular similarity is a cornerstone of modern cheminformatics and machine learning research, underpinning critical tasks from virtual screening to the prediction of activity cliffs. This guide provides an objective comparison of four fundamental metrics—Tanimoto, Dice, Euclidean, and Tversky—equipping researchers with the data and methodologies needed to inform their selection for drug development projects.

Mathematical Definitions and Properties

At their core, molecular similarity metrics quantify the resemblance between molecules, which are typically represented as fixed-length vectors known as molecular fingerprints [13]. These fingerprints encode structural features as a series of bits (often binary), where the presence or absence of a particular feature is indicated by a 1 or 0, respectively [13]. The choice of metric directly influences the quantitative similarity and, consequently, the outcome of the research [13].

The table below summarizes the formulas, core concepts, and key properties of the four key metrics.

Table 1: Mathematical Definitions and Properties of Key Similarity and Distance Metrics

| Metric Name | Formula (Fingerprint-based) | Core Concept | Value Range | Metric Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanimoto (Jaccard) | ( \frac{c}{a + b - c} ) [13] [17] | Ratio of shared "on" bits to the total unique "on" bits from both molecules. [13] | [0.0, 1.0] [17] | Symmetric; not a true metric for all data types [18]. |

| Dice (Sørensen-Dice) | ( \frac{2c}{a + b} ) [13] [17] | Ratio of shared "on" bits to the average number of "on" bits. Gives more weight to common features than Tanimoto [17]. | [0.0, 1.0] [17] | Symmetric. |

| Euclidean Distance | ( \sqrt{\frac{(a - c) + (b - c) + (c - a)}{fpsize}} ) or ( \sqrt{\frac{onlyA + onlyB}{fpsize}} ) (as a similarity) [13] [17] | Geometric distance in the fingerprint vector space. | [0.0, 1.0] (normalized) [17] | A true metric; satisfies triangle inequality. |

| Tversky | ( \frac{c}{\alpha \cdot (a - c) + \beta \cdot (b - c) + c} ) [13] [17] | An asymmetric similarity measure weighted by parameters ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ). | [0.0, 1.0] [17] | Asymmetric (unless ( \alpha = \beta )). |

Legend for formula variables:

- ( a ): Number of "on" bits in molecule A.

- ( b ): Number of "on" bits in molecule B.

- ( c ) (or ( bothAB )): Number of "on" bits common to both A and B.

- ( onlyA ): Bits on in A but not in B (( = a - c )).

- ( onlyB ): Bits on in B but not in A (( = b - c )).

- ( fpsize ): Total length of the fingerprint in bits.

- ( \alpha, \beta ): Tversky weighting parameters.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Theoretical definitions alone are insufficient for metric selection. Experimental benchmarking using real-world chemical datasets is essential to understand how these metrics behave in practice. A typical benchmarking workflow involves calculating pairwise similarities for a diverse set of molecules using different metrics and fingerprints, then analyzing the resulting distributions and performance in specific tasks like activity prediction.

Diagram 1: Experimental benchmarking workflow for molecular similarity metrics.

Similarity Distribution and Comparative Ranking

To illustrate the practical differences between metrics, consider three example molecules (A, B, and C) from a cheminformatics toolkit demonstration [17]. Using MACCS keys fingerprints, the calculated Tanimoto similarities were:

- Tanimoto(A,B) = 0.618

- Tanimoto(A,C) = 0.709

- Tanimoto(B,C) = 0.889 [17]

This shows that molecules B and C are judged as the most similar pair, sharing the largest number of common structural features [17]. However, the same molecules can be ranked differently by other metrics due to their unique mathematical properties.

Table 2: Comparative Ranking of Example Molecules Using Different Metrics

| Molecule Pair | Tanimoto | Dice | Euclidean (Similarity) | Tversky (α=0.5, β=1.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A, B) | 0.618 [17] | Higher than Tanimoto | Lower than Tanimoto | Highly dependent on parameters |

| (A, C) | 0.709 [17] | Higher than Tanimoto | Lower than Tanimoto | Highly dependent on parameters |

| (B, C) | 0.889 [17] | Higher than Tanimoto | Lower than Tanimoto | Highly dependent on parameters |

Note: The values in this table are for illustrative purposes. Dice typically returns higher values than Tanimoto for the same molecule pair, while Euclidean distance as a similarity measure often provides a different ranking profile [13] [17].

Furthermore, the choice of molecular fingerprint has a significant influence on the resulting similarity space. Research using randomly selected structures from the ChEMBL database has shown that for the same set of molecules, MACCS key-based similarity spaces can identify structures as more similar compared to chemical hashed linear fingerprints (CFP), while extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFP) may identify the same structures as the least similar [13]. This highlights the critical need to select a fingerprint that aligns with the type of structural or feature similarity being investigated [13].

Experimental Protocol for Metric Benchmarking

To ensure reproducible and meaningful results, follow this detailed experimental protocol:

- Dataset Curation: Select a relevant, publicly available dataset of drug-like molecules with associated bioactivity data. Common choices include:

- Fingerprint Generation: Generate multiple fingerprint types for all molecules in the dataset. Standard types include:

- Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP): A circular fingerprint that captures atom environments [13].

- MACCS Keys: A dictionary-based fingerprint using a predefined set of structural fragments [13].

- Path-based Hashed Fingerprints (e.g., CFP): Encodes linear paths within the molecule up to a predefined length [13].

- Similarity Calculation: For every pair of molecules in the dataset, compute the similarity using each metric (Tanimoto, Dice, etc.) for every fingerprint type generated. This creates a multi-dimensional similarity matrix.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: Order compounds by their similarity to a reference molecule and inspect trends in the measured activity. Identify "activity cliffs," where structurally similar compounds have drastically different properties, to understand the influence of specific structural moieties [13].

- Virtual Screening Power: Use a known active compound as a reference. Rank the entire library by similarity and measure the early enrichment of other known actives (e.g., using ROC curves or enrichment factors).

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of computational tools and datasets.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Molecular Similarity Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Computational Representation | Encodes molecular structure as a fixed-length vector for quantitative comparison. | ECFP, MACCS, Path-based [13] |

| Curated Bioactivity Dataset | Data | Provides molecular structures and experimental data for benchmarking and model training. | ChEMBL [13], ZINC250k [19] |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Software Library | Provides algorithms for fingerprint generation, similarity calculation, and molecular manipulation. | OEChem Toolkits [17], RDKit, ChemAxon [13] |

| Similarity/Distance Metric | Algorithm | The function that quantifies the resemblance or distance between two molecular fingerprints. | Tanimoto, Dice, Euclidean, Tversky [13] [17] |

Selecting an appropriate molecular similarity metric is not a one-size-fits-all decision. The Tanimoto coefficient remains the most popular and robust choice for general-purpose similarity searching with binary fingerprints. The Dice coefficient serves as a close alternative that places greater emphasis on common features. For applications requiring a true geometric distance that obeys the triangle inequality, the Euclidean distance is mathematically sound. Finally, the Tversky index offers a powerful, asymmetric approach for targeted queries, such as identifying structural analogs of a lead compound that contain specific, desirable substructures.

The most critical insight is that the fingerprint and metric form an interdependent pair. Researchers should empirically benchmark several fingerprint-metric combinations against their specific biological data and research objectives—be it virtual screening, SAR analysis, or training machine learning models—to identify the optimal strategy for their work in computational drug discovery.

In computational drug discovery, the Similarity Principle is a foundational tenet, positing that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activity [20]. The Similarity Paradox arises from the frequent violation of this principle, where minute structural changes lead to dramatic shifts in compound potency [20]. These specific instances are known as Activity Cliffs (ACs), defined as pairs or groups of structurally similar compounds that are active against the same target but have large differences in potency [21].

Initially considered detrimental to predictive quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, activity cliffs are now recognized as highly informative sources of structure-activity relationship (SAR) knowledge [21]. They pinpoint precise chemical modifications that profoundly influence biological activity, making them focal points for lead optimization in medicinal chemistry [21]. This guide provides a comparative assessment of the computational methods and molecular representation strategies used to identify, analyze, and predict these critical phenomena.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Methods

The accurate identification of activity cliffs hinges on how molecular "similarity" is defined and quantified. The core challenge lies in the fact that different molecular representations can yield different, and sometimes conflicting, assessments of similarity [21] [22]. The following table summarizes the performance of key representation methods in the context of similarity and cliff prediction.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Representation Methods for Similarity and Activity Cliff Analysis

| Representation Method | Basis of Similarity | Advantages | Limitations in Cliff Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS) [21] [23] | Topological structure (atomic connectivity) | Computationally efficient; interpretable (substructures); widely used in QSAR [10] [23]. | Whole-molecule similarity can miss critical local differences; threshold for "similar" is subjective [21]. |

| Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) [21] | Single, localized chemical modification | Chemically intuitive; directly identifies analog pairs; pinpoints modification sites [21]. | Limited to single-site changes; cannot capture cliffs from multi-point substitutions [21]. |

| 3D & Interaction Fingerprints (IFPs) [21] | Ligand geometry & protein-ligand interactions | Explains cliffs via binding mode differences; invaluable for structure-based design [21]. | Requires experimental protein-ligand complex structures; computationally intensive [21]. |

| AI-Driven Representations (GNNs, Transformers) [22] [24] | Learned features from data | Captures complex, non-linear structure-property relationships; potential for superior generalization [22]. | "Black box" nature reduces interpretability; performance depends on data quality and quantity [22]. |

| Similarity-Quantified Relative Learning (SQRL) [24] | Relative difference between similar pairs | Reformulates prediction to focus on potency differences; excels in low-data regimes common in drug discovery [24]. | Novel framework requiring specialized implementation; performance depends on similarity threshold choice [24]. |

Experimental Protocols for Activity Cliff Analysis

Protocol 1: Systematic Identification of 2D Activity Cliffs

This methodology outlines a standard cheminformatics pipeline for identifying activity cliffs from large compound databases [21].

- Objective: To systematically identify pairs of structurally similar compounds with large potency differences from a public repository like ChEMBL [21].

- Materials:

- Compound & Bioactivity Data: A curated dataset from a source like ChEMBL, containing compound structures and corresponding bioactivity measurements (e.g., IC50, Ki) for a specific target [21] [23].

- Fingerprinting Software: A cheminformatics toolkit such as RDKit to compute molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) [23].

- Similarity Calculator: Code to compute the Tanimoto similarity coefficient from fingerprint bit-strings [21].

- Procedure:

- Data Curation: Filter the bioactivity data for a single target, retaining only high-confidence potency measurements.

- Fingerprint Generation: Encode all compounds in the dataset using a chosen fingerprint method (e.g., ECFP4 with a 1024-bit length) [23].

- Similarity & Potency Difference Calculation: For every unique pair of compounds, calculate the Tanimoto similarity and the absolute difference in their potency values (typically log-scaled).

- Cliff Identification: Apply threshold criteria to define an activity cliff. A common definition is a Tanimoto similarity ≥ 0.85 and a potency difference ≥ 100-fold (2 log units) [21].

- Network Analysis (Optional): Represent compounds as nodes and activity cliff relationships as edges in a network to visualize coordinated cliff formation and identify "AC generator" compounds [21].

Protocol 2: A Machine Learning Framework for Cliff-Informed Prediction

This protocol describes a modern ML approach that leverages the concept of activity cliffs to improve predictive models [24].

- Objective: To train a machine learning model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) using a relative difference learning strategy to enhance predictive accuracy on structurally similar compounds [24].

- Materials:

- Dataset: A dataset ( \mathcal{D} = {(xi, yi)} ) of molecular structures ( xi ) and their potency values ( yi ) [24].

- Model Architecture: A graph neural network (e.g., D-MPNN) or other feature encoder ( g: \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^d ), and a predictor network ( f: \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R }) [24].

- Similarity Metric: A predefined metric like Tanimoto similarity on ECFP4 fingerprints [24].

- Procedure:

- Dataset Matching: Construct a relative dataset ( \mathcal{D}{\text{rel}} ) by pairing molecules that exceed a structural similarity threshold ( \alpha ). Each data point is ( ((xi, xj), \Delta y{ij}) ), where ( \Delta y{ij} = yi - yj ) [24].

- Model Training: Instead of learning to predict absolute potency ( yi ), the model is trained to predict the relative potency difference ( \Delta y{ij} ). The loss function is: ( \min\theta \sum \ell(f(g(xi) - g(xj)), \Delta y{ij}) ) [24].

- Inference: For a new molecule ( x{\text{new}} ), its potency is predicted by averaging over its nearest neighbors in the training set: ( \hat{y}{\text{new}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum{xi \in \text{NN}n(x{\text{new}})} [yi + f(g(xi) - g(x{\text{new}})) ]) [24].

Graph 1: Workflow for a Relative Difference Machine Learning Model

Visualizing Complex Activity Landscapes

Activity cliffs are rarely isolated events. They often form coordinated networks where a single potent compound can form cliffs with multiple less potent analogs, creating "clusters" in the activity landscape [21]. Understanding these relationships is key to extracting maximum SAR information.

Graph 2: Network Representation of Coordinated Activity Cliffs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Molecular Similarity and Activity Cliff Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [23] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, generates fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4), and performs standard cheminformatics operations. |

| ChEMBL [21] | Public Bioactivity Database | Provides a vast, curated source of compound structures and associated bioactivity data for benchmarking and analysis. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [23] | Explainable AI (xAI) Library | Interprets ML model predictions by quantifying the contribution of each input feature (e.g., a fingerprint bit) to the output. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [22] [24] | Machine Learning Architecture | Learns complex molecular representations directly from graph-structured data (atoms and bonds). |

| Tanimoto Coefficient [21] | Similarity Metric | The standard measure for calculating similarity between two molecular fingerprints, ranging from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical). |

| Matched Molecular Pair (MMP) Algorithms [21] | Chemical Fragmentation Tool | Systematically identifies pairs of compounds that differ only at a single site to isolate the effect of specific chemical transformations. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Similarity Metrics for Predictive Modeling and Virtual Screening

Molecular fingerprinting, the process of representing chemical structures as numerical vectors, serves as the foundation for quantifying similarity in machine learning applications within chemical and biological sciences. The performance of these similarity metrics directly influences the success of tasks ranging from drug discovery to diagnostic development. This guide provides a comparative analysis of molecular fingerprint performance across three distinct domains: olfaction-based disease diagnosis, toxicity prediction via solubility, and anti-tuberculosis activity profiling. By examining experimental protocols, performance benchmarks, and technical requirements, we aim to equip researchers with practical insights for selecting appropriate fingerprinting strategies in their molecular similarity assessments.

The evaluation of molecular similarity metrics remains challenging due to the context-dependent nature of "similarity" across different applications. In olfaction, fingerprints capture volatile organic compound (VOC) profiles that serve as disease biomarkers. For toxicity assessment, molecular dynamics-derived properties function as fingerprints predicting solubility. In tuberculosis research, both host-response proteins and pathogen-specific lipids serve as fingerprint bases for diagnostic applications. Understanding the performance characteristics across these domains enables more informed experimental design in machine learning-driven molecular research.

Case Study I: Olfaction-Based Diagnostic Fingerprints

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Breath analysis leverages volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as olfactory fingerprints for disease detection. The fundamental protocol involves sample collection, VOC analysis, and pattern recognition using machine learning. Sample collection typically uses Tedlar bags, glass canisters, or solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers to capture exhaled breath [25]. For analytical separation and identification, gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) serves as the gold standard, enabling the identification of hundreds of VOCs in a single sample [26] [25]. Advanced techniques like two-dimensional GC×GC-MS provide enhanced resolution for complex mixtures [25].

Proton Transfer Reaction Mass Spectrometry (PTR-MS) and Selected Ion Flow Tube Mass Spectrometry (SIFT-MS) enable real-time, sensitive detection of VOCs at parts-per-trillion levels without pre-concentration [25]. These techniques utilize soft ionization, preserving molecular information while minimizing fragmentation. Electronic noses (e-noses) employing chemical sensor arrays offer portable alternatives, generating response patterns that serve as olfactory fingerprints without identifying individual VOCs [26] [25]. For urine-based olfaction diagnostics, colorimetric sensor arrays (CSAs) with 73 different chemical indicators capture spatiotemporal signatures of volatile compounds under various pretreatment conditions (neat, acidified, basified, salted, pre-oxidized) [27].

Machine learning workflows for olfaction fingerprint analysis typically involve feature selection (e.g., Principal Component Analysis) followed by classification algorithms including Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, and increasingly, deep learning models like CNNs and LSTMs [25]. The large dimensionality of VOC data (often hundreds to thousands of features) makes feature reduction critical for model performance.

Performance Benchmarking

The diagnostic performance of olfaction-based fingerprints varies by disease target and analytical method. In tuberculosis detection, urine headspace analysis using colorimetric sensor arrays achieved 85.5% sensitivity and 79.5% specificity under optimized (basified) conditions [27]. For breath analysis across various diseases, machine learning models have demonstrated promising but variable performance, with the best-performing models achieving accuracies exceeding 90% for specific conditions like lung cancer and asthma [25].

Electronic nose systems show particular promise for respiratory disease detection, though performance depends heavily on the sensor technology and pattern recognition algorithms employed. A critical challenge across all olfaction-based methods is the influence of confounding factors including diet, age, medications, and environmental exposures, which can substantially impact VOC profiles [26] [25]. Large-scale validation studies are needed to establish robust clinical performance benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Olfaction-Based Diagnostic Methods

| Analytical Method | Disease Target | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sample Type | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric Sensor Array | Tuberculosis | 85.5% | 79.5% | Urine headspace | Confounding clinical variables |

| GC-MS with ML | Various cancers | 74-96%* | 78-94%* | Exhaled breath | Standardization challenges |

| Electronic Nose | Respiratory diseases | 70-92%* | 75-90%* | Exhaled breath | Limited compound identification |

| PTR-MS/SIFT-MS | Metabolic disorders | 65-89%* | 72-91%* | Exhaled breath | Equipment cost and expertise |

*Performance ranges across multiple studies as summarized in the literature [25]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Olfaction-Based Fingerprinting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tedlar Bags | Sample collection and storage | Breath VOC sampling |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | VOC pre-concentration | GC-MS sample preparation |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Systems | VOC separation and identification | Compound identification in breath |

| Chemical Sensor Arrays (Electronic Noses) | Pattern-based VOC detection | Rapid disease screening |

| Colorimetric Sensor Arrays (CSAs) | Visual VOC pattern detection | Urine headspace analysis for TB |

Case Study II: Toxicity Prediction via Solubility Fingerprints

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Solubility serves as a critical fingerprint for toxicity prediction in drug development, with machine learning models leveraging molecular dynamics (MD) properties as feature vectors. The standard experimental protocol for thermodynamic solubility measurement involves the shake-flask method, where compounds are agitated in aqueous solution until equilibrium is reached, followed by concentration measurement of the saturated solution using HPLC-UV, nephelometry, or quantitative NMR [12]. For kinetic solubility assessment, high-throughput methods measure compound precipitation from supersaturated solutions using turbidimetry or static light scattering.

Computational protocols employ molecular dynamics simulations using software packages like GROMACS with force fields (e.g., GROMOS 54a7) to calculate physicochemical properties that serve as solubility fingerprints [12]. Simulations are typically conducted in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble with explicit water molecules to model aqueous environments. Key MD-derived properties include Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, estimated solvation free energies (DGSolv), and structural dynamics parameters (RMSD) [12].

Machine learning workflows for solubility-based toxicity prediction typically incorporate both MD-derived properties and traditional descriptors like octanol-water partition coefficient (logP). Ensemble methods including Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Extreme Gradient Boosting have demonstrated superior performance for modeling the non-linear relationships between molecular fingerprints and solubility [12]. Feature selection techniques are critical for optimizing model performance and interpretability.

Performance Benchmarking

The predictive performance of solubility fingerprints varies based on the descriptor set and machine learning algorithm employed. In benchmark studies using a dataset of 211 diverse drugs, MD-derived properties (SASA, Coulombic interactions, LJ energies, DGSolv, RMSD) combined with logP achieved predictive performance comparable to structural fingerprint-based models, with Gradient Boosting regression achieving R² = 0.87 and RMSE = 0.537 on test sets [12].

The seven most influential properties for solubility prediction were identified as logP, SASA, Coulombic interactions, Lennard-Jones potentials, solvation free energy, RMSD, and average solvation shell occupancy [12]. This MD-based approach demonstrated particular value in capturing molecular interactions and dynamics relevant to dissolution behavior, providing advantages over static structural fingerprints alone. However, MD simulations require substantial computational resources, creating trade-offs between model accuracy and practical implementation.

Table 3: Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms for Solubility Prediction

| Algorithm | R² | RMSE | Key Advantages | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting | 0.87 | 0.537 | Handles non-linear relationships | Moderate |

| Random Forest | 0.85 | 0.562 | Robust to overfitting | Moderate |

| Extra Trees | 0.84 | 0.571 | Reduced variance | Moderate |

| XGBoost | 0.86 | 0.548 | Optimization capabilities | High |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Solubility Fingerprinting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | MD property calculation |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Concentration measurement | Thermodynamic solubility |

| Nephelometry/Turbidimetry | Precipitation detection | Kinetic solubility assessment |

| 1-Octanol/Water System | Partition coefficient measurement | logP determination |

Case Study III: Anti-Tuberculosis Activity Fingerprints

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Tuberculosis diagnostics employ diverse fingerprinting strategies targeting both host responses and pathogen-specific markers. For host-response fingerprinting, the Xpert-HR test utilizes a 3-gene signature (GBP5, DUSP3, KLF2) from finger-stick blood samples, measuring host mRNA transcripts via quantitative PCR in cartridge-based formats [28]. The multibiomarker test (MBT) detects three host proteins (serum amyloid A, C-reactive protein, interferon-γ-inducible protein 10) using lateral flow technology with up-converting reporter particles [28].

For pathogen-directed fingerprinting, lipid-based MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identifies species-specific glycolipids and sulfolipids that distinguish Mycobacterium tuberculosis within the complex [29]. The protocol involves culturing mycobacteria, heat inactivation, and direct analysis using negative ion mode MS to detect characteristic lipid profiles [29]. Urine-based volatile organic compound analysis employs colorimetric sensor arrays under various pretreatment conditions to detect TB-specific metabolic signatures [27].

Study protocols for TB diagnostic validation typically employ a composite reference standard incorporating sputum microbiology (culture, Xpert Ultra), chest radiography, and treatment response [28]. This comprehensive approach accounts for limitations in individual diagnostic methods and provides more reliable classification of TB status for model training and validation.

Performance Benchmarking

Host-response fingerprints demonstrate strong triage performance for pulmonary tuberculosis. The Xpert-HR test achieved 92.8% sensitivity and 62.5% specificity at its optimal cutoff, while the multibiomarker test showed 91.4% sensitivity and 73.2% specificity, meeting WHO target product profile criteria for triage tests [28]. The MBT particularly demonstrated balanced performance with negative predictive values exceeding 96%, making it suitable for ruling out tuberculosis in symptomatic patients.

Pathogen-directed fingerprints offer complementary advantages. Lipid-based MALDI-TOF MS directly identified M. tuberculosis within the complex with 86.7% sensitivity and 93.7% specificity based on sulfolipid biomarkers [29]. This method provides species-level identification without requiring lengthy growth-based characterization. Urine VOC analysis using colorimetric sensor arrays achieved 85.5% sensitivity and 79.5% specificity under basified conditions, offering a completely non-invasive alternative [27].

Table 5: Performance Comparison of Tuberculosis Diagnostic Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Method | Target | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sample Type | WHO TPP Met? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xpert-HR (3-gene signature) | Host mRNA | 92.8% | 62.5% | Finger-stick blood | Sensitivity only |

| Multibiomarker Test (3 proteins) | Host proteins | 91.4% | 73.2% | Finger-stick blood | Yes |

| MALDI-TOF (lipid profiling) | Pathogen lipids | 86.7% | 93.7% | Bacterial culture | N/A |

| Colorimetric Sensor Array | Urine VOCs | 85.5% | 79.5% | Urine headspace | N/A |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Research Reagents for TB Activity Fingerprinting

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Xpert-HR Cartridge | Host mRNA measurement | Gene expression fingerprinting |

| Lateral Flow Strips (MBT) | Protein detection | Host protein fingerprinting |

| MALDI-TOF MS System | Lipid profiling | Pathogen identification |

| Colorimetric Sensor Array | VOC pattern detection | Urine-based TB diagnosis |

| BACTEC MGIT Culture System | Reference standard | TB culture confirmation |

Cross-Domain Comparative Analysis

The three case studies reveal fundamental differences in fingerprinting strategies based on application requirements. Olfaction-based diagnostics prioritize high-dimensional pattern recognition of complex VOC mixtures, requiring sophisticated separation science and multivariate analysis. Solubility prediction for toxicity assessment employs physics-based molecular dynamics properties to capture fundamental intermolecular interactions. Tuberculosis diagnostics utilize either host-response patterns or pathogen-specific markers, each with distinct advantages in speed versus specificity.

Machine learning approaches similarly vary across domains. For olfaction, both traditional ML (SVM, Random Forest) and deep learning (CNNs, LSTMs) are employed to handle complex VOC patterns [25]. Solubility prediction benefits from ensemble methods (Gradient Boosting, Random Forest) that capture non-linear structure-property relationships [12]. TB diagnostics primarily utilize predefined biomarker panels with optimized cutoffs, though ML approaches are emerging for pattern recognition in host-response and VOC-based methods.

Data standardization emerges as a universal challenge across all domains. In olfaction, variability in sample collection, instrumentation, and data processing complicates cross-study comparisons [25]. For solubility prediction, inconsistencies in experimental measurements hinder model training [12]. In TB diagnostics, heterogeneous reference standards impact performance evaluation [28]. Community-wide standards for data collection, reporting, and benchmarking are critical for advancing molecular fingerprinting applications.

Methodological Workflows

Diagram 1: Molecular Similarity Assessment Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the iterative process for developing and validating molecular fingerprinting strategies across application domains.

This comparative analysis demonstrates that optimal fingerprint performance depends critically on alignment between molecular representation, analytical methodology, and application context. Olfaction-based diagnostics excel in non-invasive screening but require careful control of confounding variables. Solubility fingerprints provide robust toxicity prediction but demand substantial computational resources. Tuberculosis diagnostics balance speed and accuracy through either host-response or pathogen-directed approaches. Across all domains, machine learning enhances fingerprint performance by capturing complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data. Future advances will likely involve hybrid fingerprinting strategies that combine multiple molecular representations, along with improved standardization to facilitate cross-domain comparisons and clinical implementation.

The concept that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities lies at the very foundation of modern drug discovery [30]. This principle of molecular similarity enables computational approaches to efficiently navigate the vast chemical space and identify promising candidate compounds during the early stages of drug development [4]. Similarity-driven workflows have become indispensable tools in virtual screening (VS), where they dramatically reduce the time and costs associated with experimental high-throughput screening by prioritizing compounds with the highest potential for desired biological activity [31] [32]. At the core of these workflows are molecular representations and similarity metrics that quantify the degree of resemblance between compounds, forming the basis for predicting molecular behavior and target interactions [22] [4].

The rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has significantly advanced molecular representation methods, moving beyond traditional rule-based approaches to more sophisticated data-driven techniques [22]. These advancements have enhanced our ability to characterize molecules and explore broader chemical spaces, particularly for applications such as scaffold hopping—where the goal is to discover new core structures while retaining biological activity [22]. As drug discovery tasks grow more complex, the limitations of traditional string-based representations like Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) have become more apparent, spurring the development of AI-driven approaches that can capture intricate relationships between molecular structure and function [22]. This review examines the current landscape of similarity-driven workflows, comparing traditional and modern approaches through experimental data and practical applications in virtual screening and hit identification.

Molecular Representations and Similarity Metrics

Fundamental Molecular Representations