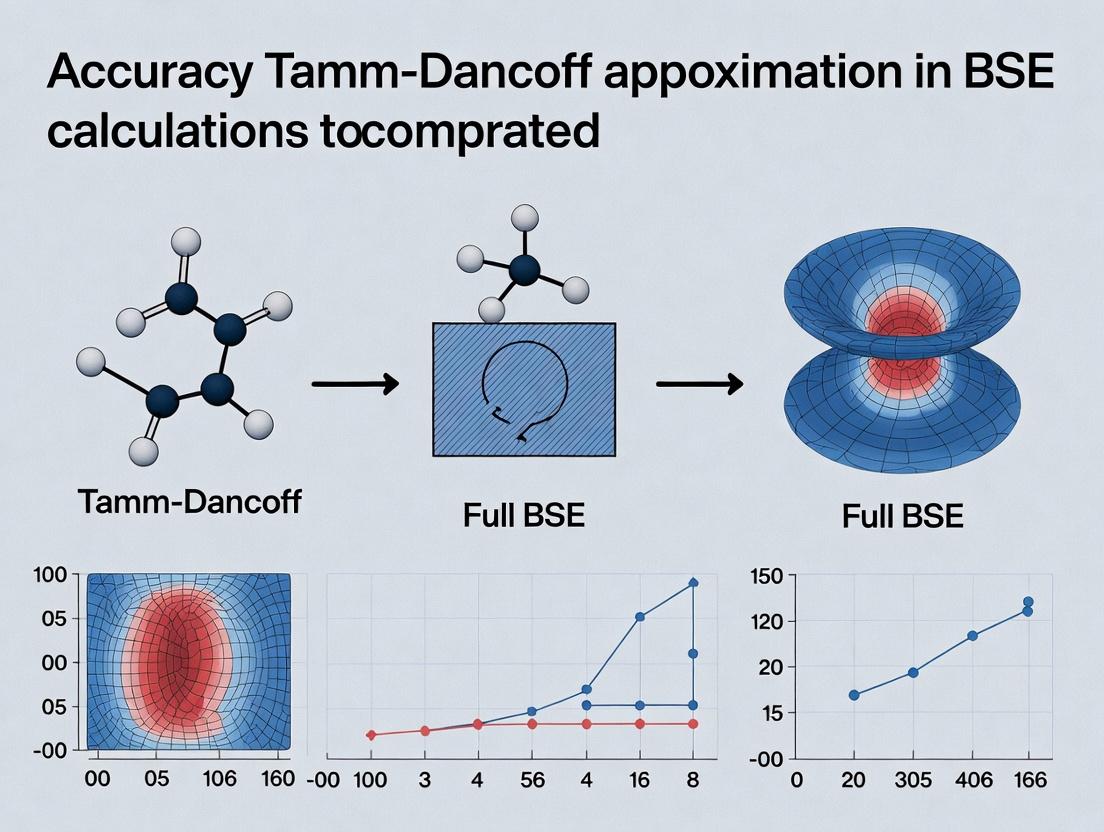

BSE Tamm-Dancoff vs. Full BSE: Accuracy Benchmarks for Excited States in Biomolecular & Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) within the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) versus the full BSE framework.

BSE Tamm-Dancoff vs. Full BSE: Accuracy Benchmarks for Excited States in Biomolecular & Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) within the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) versus the full BSE framework. Targeted at computational researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental theory, practical computational workflows, and systematic benchmarks for predicting optical absorption spectra and excitation energies. Key focus areas include accuracy trade-offs, computational cost, troubleshooting common convergence issues, and validation strategies for biomolecular systems like photosynthetic complexes and pharmaceutical chromophores. The analysis synthesizes current best practices for selecting the appropriate BSE approach to enhance reliability in predicting photophysical properties critical to materials design and drug discovery.

Understanding BSE and the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation: Core Theory for Excited-State Calculations

Technical Support Center: BSE Implementation & Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My BSE calculation in the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) yields exciton energies but no oscillator strengths. What is wrong?

A: This typically indicates a missing or incorrect post-processing step. The TDA solves for exciton eigenvectors but oscillator strengths require the computation of the transition dipole moments between the ground state and the excitonic state. Ensure your code correctly calculates:

f_n ∝ | Σ_{v,c,k} A_{v,c,k}^n * ⟨v,k| r |c,k⟩ |²

where A_{v,c,k}^n are the exciton amplitudes. Verify that the dipole matrix elements ⟨v,k| r |c,k⟩ are being read or calculated correctly from the underlying DFT/GW step.

Q2: When comparing Full BSE vs. BSE-TDA for organic molecules, I find large discrepancies in triplet excitation energies. Is this expected? A: Yes, this is a known systematic error. The TDA neglects the coupling between resonant (electron-hole creation) and anti-resonant (hole-electron creation) transitions. For triplet excitons, where exchange effects dominate, this coupling is significant. The Full BSE includes this coupling, leading to more accurate triplet energies. The error in TDA can be quantitatively assessed (see Table 1).

Q3: My BSE optical spectrum for a 2D material shows an unphysical "red shift" with improved k-point sampling. How do I fix this? A: This is often a sign of an insufficiently converged screening calculation (GW or model dielectric function) used to build the BSE kernel. The screening must be converged independently with respect to k-points and band counts before BSE convergence. Follow this protocol:

- Converge the quasi-particle bandgap (GW) with k-points.

- Converge the static dielectric screening matrix (

W(ω=0)) with k-points and a high number of empty bands. - Only then converge the BSE Hamiltonian with k-points and electron-hole pairs.

Q4: How do I diagnose if my Full BSE solver is stuck in a "charge-transfer" exciton artifact?

A: Inspect the exciton wavefunction (electron-hole correlation). A true artifact often shows pathological delocalization. Calculate the electron-hole separation √⟨r_e - r_h⟩² for the suspect state. Compare it to the system's physical size. An improbably large separation (> system size) may indicate a numerical instability, often tied to an under-converged Coulomb truncation (for slabs) or insufficient basis set. Switch to a larger, more diffuse basis and ensure proper Coulomb truncation techniques are applied.

Table 1: Representative Error Analysis of BSE-TDA vs. Full BSE for Benchmark Systems Data synthesized from recent literature on molecular and solid-state benchmarks.

| System Class | Excitation Type | Mean Absolute Error (TDA vs. Exp/Full BSE) [eV] | Key Deficiency of TDA | Recommended Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Organic Molecules (e.g., Thiel set) | Singlet (low-lying) | 0.05 - 0.15 | Minor | TDA (for speed) |

| Small Organic Molecules | Triplet | 0.2 - 0.5 | Severe, misses coupling | Full BSE |

| Extended π-Conjugated Polymers | Low-energy Singlet | 0.1 - 0.3 | Overestimates binding energy | Full BSE |

| 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides | Bright A Exciton | < 0.05 | Negligible for this state | TDA acceptable |

| Charge-Transfer Systems | CT Exciton | 0.3 - 0.8 | Poor description of screening | Full BSE with accurate W |

Table 2: Computational Cost Comparison: TDA vs. Full BSE Solver Relative scaling for a system with N electron-hole pair basis functions.

| Operation | TDA Scaling | Full BSE Scaling | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian Diagonalization | ~O(N³) | ~O(8N³) | Full BSE is ~8x heavier in core step. |

| Matrix Element Storage | ~O(N²) | ~O(4N²) | Full BSE requires 4x memory for Hamiltonian. |

| Kernel Construction | ~O(N²) | ~O(N²) | Similar cost for building interaction terms. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating BSE-TDA Accuracy for a New Organic Semiconductor Objective: Determine if the faster BSE-TDA is sufficient for screening the optical gap of novel donor molecules.

- System Preparation: Optimize ground-state geometry using DFT (PBE0/def2-SVP).

- Quasi-Particle Correction: Perform a single-shot G0W0 calculation on the DFT topology using a converged planewave basis or large Gaussian basis set (def2-QZVP).

- BSE Kernel Setup: Construct the static screening kernel (

W(ω=0)) using the Godby-Needs plasmon-pole model or full-frequency integration. - Parallel Calculation: Run both BSE-TDA and Full BSE solvers using the identical kernel and transition space (include at least 5x the number of valence and conduction bands relative to the bandgap).

- Analysis: Extract the energy and oscillator strength of the first bright singlet exciton (S1). If the TDA vs. Full BSE discrepancy is > 0.1 eV or the oscillator strength ratio differs by >20%, Full BSE is required for this class.

Protocol 2: Diagnosing Solver Convergence in Full BSE Objective: Ensure the Full BSE eigenvalues are physically meaningful and converged.

- Basis Truncation Test: Increase the number of included valence (v) and conduction (c) bands in the electron-hole basis in steps (e.g., 5, 10, 15 bands above/below gap). Plot the target exciton energy vs. basis size.

- K-Point Convergence: Repeat the calculation on successively finer k-meshes (e.g., 4x4x1, 8x8x1, 12x12x1 for 2D). The exciton energy should plateau.

- Positive-Definiteness Check: For the Full BSE Hamiltonian in the form

[[A, B], [-B*, -A*]], verify that the matrix(A - B)is positive definite. If not, it indicates instability, often requiring more accurate initial quasi-particle energies or a larger basis. - Convergence Criteria: The calculation is converged when the exciton energy changes by less than 10 meV for both basis size and k-point increase.

Visualizations

Title: BSE Implementation Workflow & Solver Decision Tree

Title: Structure of the Full BSE Hamiltonian Matrix

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Software Code | Function in BSE Experiments | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| GW Pseudopotential/Basis Set | Provides starting quasi-particle energies and wavefunctions. | Accuracy of dielectric screening depends heavily on this. Use hybrid-starting points or self-consistent GW for difficult systems. |

| Static Screening Kernel (W) | Forms the attractive electron-hole interaction in the BSE kernel. | Convergence with empty bands is crucial. Model dielectric functions (e.g., RPA) can be a bottleneck. |

| BSE Solver (TDA/Full) | Diagonalizes the excitonic Hamiltonian to obtain excited states. | Choice dictates accuracy for triplets/CT states. Full BSE requires stable diagonalization of non-Hermitian form. |

| Transition Space Truncation | Defines the number of valence (v) and conduction (c) bands included. | Systematic convergence required. Too small → inaccurate binding energies. Too large → prohibitive cost. |

| Coulomb Truncation Scheme | Removes spurious long-range interactions in periodic simulations of low-D systems. | Essential for 2D materials and slabs. Incorrect truncation leads to wrong exciton sizes and energies. |

| Excitonic Wavefunction Analyzer | Calculates spatial extent, electron-hole distance, and charge density. | Key for diagnosing exciton character (Frenkel, CT, Wannier) and validating results against physical intuition. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My TDA-BSE calculation for an organic semiconductor shows a significant underestimation of the S1 excitation energy compared to experiment. The full BSE result is much closer. What could be the cause and how can I diagnose it?

A: This is a common issue when charge-transfer (CT) excitations are involved. The TDA neglects the resonant-anti-resonant coupling, which can be crucial for CT states. To diagnose:

- Check the spatial overlap of the hole and electron orbitals for the S1 state. Low overlap indicates a CT character.

- Compare the TDA and full BSE eigenvectors for the state. Large differences confirm the TDA's inadequacy.

- Protocol: Run a full BSE calculation (if computationally feasible) and compare the energy and oscillator strength. Use the following analysis workflow.

Diagram Title: CT Excitation Diagnosis Workflow

Q2: I am getting numerical instability or a non-Hermitian error when setting up the full BSE Hamiltonian, but the TDA works fine. How do I resolve this?

A: This often stems from an inadequate basis set or incomplete spectral sampling in the Green's function. The coupling blocks (B) in the full BSE are sensitive to these factors.

- Solution: Ensure you are using a well-converged number of empty (conduction) states. The number needed for full BSE is typically larger than for TDA.

- Protocol: Systematically increase the number of bands (

NBANDSor equivalent) in your underlying DFT or GW calculation until the problematic matrix elements converge.

Q3: When should I definitively choose full BSE over TDA in my research on dye molecules for photovoltaics?

A: The choice is system- and property-dependent. Use the following decision table based on quantitative benchmarks from recent literature.

| System Property / Excitation Type | Recommended Method (TDA vs. Full BSE) | Typical Error Range (TDA vs. Exp.) | Typical Error Range (Full BSE vs. Exp.) | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-lying Frenkel (localized) excitons | TDA is often sufficient | ±0.1 - 0.3 eV | ±0.1 - 0.2 eV | Coupling (B) block is small. TDA is stable and fast. |

| Charge-Transfer (CT) Excitations | Require Full BSE | Can be > 0.5 eV underestimation | ±0.1 - 0.3 eV | Resonant-anti-resonant coupling is essential. |

| Optical Spectrum (Oscillator Strengths) | Full BSE is preferred | May distort relative peak intensities | More accurate lineshape | TDA violates the oscillator strength sum rule. |

| Triplet Excitation Energies | TDA is commonly used | Comparable to full BSE | Comparable to TDA | Exchange-driven, less affected by coupling. |

Table: Decision Guide: TDA vs. Full BSE for Molecular Systems

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking TDA vs. Full BSE Accuracy

Objective: To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation against the full Bethe-Salpeter equation for vertical excitation energies in a test set of molecules.

Computational Methodology:

- Ground-State Calculation: Perform DFT geometry optimization using a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0) and a tier-2 basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) to obtain the ground-state structure.

- Quasiparticle Corrections: Perform a one-shot GW (G0W0) calculation on the DFT orbitals to obtain corrected eigenvalues. Use a plasmon-pole model and a minimum of 500-1000 empty states for convergence.

- BSE Hamiltonian Construction:

- Build the full BSE Hamiltonian in the transition space:

H_BSE = [ A B; -B* -A* ]. - Construct the TDA Hamiltonian by setting the coupling block

B = 0, resulting inH_TDA = A. - Use the same set of occupied and unoccupied states (typically 5-10 highest occupied and 5-10 lowest unoccupied) for both.

- Build the full BSE Hamiltonian in the transition space:

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize

H_BSEandH_TDAto obtain excitation energies and eigenvectors. - Analysis: For the first 3-5 singlet excitations, compare energies (TDA vs. full BSE) and oscillator strengths against high-accuracy experimental reference data.

Diagram Title: TDA vs Full BSE Benchmark Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in BSE/TDA Calculations |

|---|---|

| Hybrid DFT Functional (e.g., PBE0, B3LYP) | Provides a reasonable starting point for orbitals and eigenvalues, reducing the GW starting point dependence. |

| Plasmon-Pole Model (PPM) | Approximates the frequency dependence of the dielectric function, making the GW and BSE calculations computationally feasible. |

| Def2-TZVP Basis Set | A triple-zeta quality basis with polarization functions. Offers a good balance between accuracy and cost for molecular systems. |

| Coulomb Kernel Truncation | Essential for low-dimensional systems (e.g., 2D layers, nanotubes) to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images. |

| ScaLAPACK/BLACS Libraries | Enable parallel diagonalization of the large BSE Hamiltonian matrix, which is critical for full BSE on systems with many transition states. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for BSE (Bethe-Salpeter Equation) Computations

This technical support center addresses common issues encountered when performing BSE calculations to model electron-hole interactions, screening, and excitons, with a specific focus on the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) versus the full BSE.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: In my absorption spectrum calculation using BSE@TDA, I am missing the low-energy excitonic peak that experimental literature reports. What could be the cause?

A: This is a common issue. The likely cause is an insufficient k-point grid used in the preceding DFT and GW calculations. Excitons, especially those with a large Bohr radius (Wannier-Mott type), require a very dense sampling of the Brillouin zone to be captured correctly. A coarse k-grid can artificially destabilize these bound states.

- Troubleshooting Step: Systematically increase the k-point density (e.g., from 6x6x6 to 12x12x12) and monitor the convergence of the lowest exciton energy. The exciton binding energy is sensitive to this parameter.

Q2: When I switch from the Tamm-Dancoff approximation to the full BSE solver, my calculation fails with a memory error. How can I resolve this?

A: The full BSE includes the resonant and anti-resonant coupling terms, effectively doubling the Hamiltonian size compared to the TDA. This escalates memory usage quadratically.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce the Number of Bands: Carefully check the number of valence and conduction bands included in the construction of the electron-hole basis. Use only the bands relevant to your energy window of interest.

- Increase Parallelization: Distribute the Hamiltonian construction and diagonalization across more CPU cores and nodes if your code supports it.

- Use Iterative Solvers: If available, switch from direct diagonalization to iterative (e.g., Haydock or Lanczos) methods for solving the BSE eigenvalue problem, as they are less memory-intensive.

Q3: How sensitive are exciton binding energies to the choice of the static dielectric screening model (e.g., RPA vs. model dielectric function)?

A: They are highly sensitive. The screening function directly governs the strength of the effective electron-hole attraction. The Random Phase Approximation (RPA) is standard but can be computationally expensive. Model dielectrics (e.g., Godby-Needs) are faster but may lack material-specific details.

- Troubleshooting Step: For a systematic study (as required for a thesis on accuracy), perform a comparison. Calculate the binding energy of the first exciton using both a full RPA

ε(ω=0)and a common model dielectric function. The difference quantifies the error introduced by the screening approximation.

Q4: My BSE@TDA results for a charge-transfer exciton show a much larger deviation from experimental spectra than for Frenkel excitons. Is this expected within the TDA framework?

A: Yes, this is a known limitation discussed in research on BSE accuracy. The TDA, which neglects dynamical electron-hole coupling, is generally less reliable for charge-transfer excitons where the electron and hole are spatially separated. The full BSE includes non-adiabatic effects that can be crucial for these states.

- Troubleshooting Step: For systems with suspected charge-transfer character, running the full BSE (even for a small number of k-points and bands as a test) is essential to gauge the TDA's error for your specific system.

The following table summarizes typical quantitative findings from recent literature comparing BSE@TDA and full BSE.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metrics for BSE@TDA vs. Full BSE

| Metric | Typical Trend (TDA vs. Full BSE) | Notes / Physical Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | TDA overestimates Eb by 10-30% for Wannier excitons. | Neglect of screening from anti-resonant terms reduces effective screening, making attraction stronger. |

| Lowest Excitation Energy (E1) | TDA typically blue-shifts E1 by 0.1-0.3 eV. | Systematic overbinding pushes excitonic states to higher energies. |

| Oscillator Strength | TDA often overestimates for bright Frenkel excitons. | Changes in eigenvector composition due to omitted coupling. |

| Charge-Transfer Exciton Energy | Significant error (can be >0.5 eV); TDA performs poorly. | Dynamical coupling is critical for spatially separated e-h pairs. |

| Computational Cost | TDA is ~4-8x faster and uses ~4x less memory. | Hamiltonian is half the size (only resonant block). |

| Triplet Excitations | TDA is usually sufficiently accurate. | Anti-resonant couplings are smaller for triplets. |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking BSE Accuracy for Organic Photovoltaic Molecules

- DFT Ground State: Perform geometry optimization using a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0).

- Quasiparticle Energies: Compute GW corrections (G0W0) on top of the DFT eigenvalues to establish the single-particle gap.

- Screening: Calculate the static screening matrix (

W(ω=0)) within the RPA. - BSE Setup: Construct the electron-hole Hamiltonian using a consistent number of valence and conduction bands.

- Dual Calculation: Solve the BSE with and without the Tamm-Dancoff approximation.

- Analysis: Extract the first 5-10 excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and analyze the electron-hole wavefunction for the lowest state to characterize exciton type.

Protocol 2: Convergence Study for Excitonic Peaks in 2D Materials

- K-point Convergence: Perform steps 1-4 from Protocol 1 using a series of increasingly dense k-grids (e.g., 8x8, 16x16, 24x24, 32x32).

- Monitor: Track the energy of the first bright exciton (A peak) and its binding energy (defined as GW gap - BSE energy).

- Criterion: Consider the exciton energy converged when the change is < 0.05 eV between successive k-grids. This is critical before any TDA vs. full BSE comparison.

Visualizations

Title: BSE Workflow: TDA vs. Full BSE Comparison

Title: Key Physical Effects in BSE

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for BSE Exciton Modeling

| Item / Software | Primary Function | Notes for Users |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ABINIT) | Provides ground-state wavefunctions and eigenvalues. | Choice of functional (hybrid vs. GGA) influences starting point for GW/BSE. |

| GW/BSE Code (e.g., BerkeleyGW, YAMBO, VASP) | Computes quasiparticle corrections and solves the BSE. | Core software for the protocol. Check support for full BSE vs. TDA. |

| Post-Processing Tools (e.g., wannier90, excitonplot) | Analyzes exciton wavefunctions, spatial extent, and character. | Crucial for diagnosing Frenkel vs. charge-transfer excitons. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides CPU/GPU resources and massive parallelization. | Full BSE calculations are computationally demanding. |

| Convergence Scripts (Python/Bash) | Automates convergence tests over k-points, bands, and cutoffs. | Essential for ensuring results are physically meaningful and reproducible. |

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: During optogenetic manipulation using Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), I observe inconsistent neuronal firing. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent firing is often related to insufficient or unstable expression of the photosensitive protein or inadequate light delivery. First, verify the transfection/transduction efficiency via a fluorescence marker. Ensure your light source (typically 470 nm blue light) has a stable output intensity (common range: 1-10 mW/mm²). Check for photobleaching by reducing exposure frequency; if firing stabilizes, consider using a more photostable variant like ChR2(H134R). Also, confirm that your cell culture or tissue bath does not contain light-absorbing components that attenuate the activating wavelength.

Q2: My drug chromophore conjugate shows unexpected aggregation in aqueous buffer, affecting its absorption spectrum. How can I mitigate this? A: Aggregation of planar chromophores (e.g., porphyrins, cyanines) is common. Troubleshoot by: 1) Switching from phosphate buffer to HEPES or Tris, as phosphate ions can promote stacking. 2) Adding a low concentration (0.01-0.1% w/v) of a biocompatible surfactant like Tween-80 or pluronic F-127. 3) Increasing the ionic strength gradually to screen electrostatic interactions. 4) If the conjugate design allows, introduce bulky hydrophilic groups (e.g., PEG chains) in the next synthesis iteration. Monitor the monomer peak intensity (e.g., for ICG, ~780 nm) spectrophotometrically before and after changes.

Q3: For live-cell bio-imaging with a GFP-tagged protein, I experience rapid photobleaching and high background. What are the key optimization steps? A: This indicates excessive excitation intensity. Implement the following protocol: 1) Lower the excitation light power to the minimum that yields a detectable signal. 2) Use a narrower emission filter to reduce autofluorescence background. 3) Consider using an oxygen-scavenging system (e.g., glucose oxidase/catalase) in the imaging medium to reduce phototoxicity. 4) Replace GFP with a more photostable variant like mNeonGreen or sfGFP. 5) For confocal microscopy, increase the pinhole size slightly and use line scanning instead of point scanning if possible to reduce photon flux.

Q4: How does the accuracy of the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) impact the computational design of new drug chromophores? A: Within the thesis context comparing BSE@TDA vs. full BSE, the TDA (which neglects resonant-antiresonant coupling) is computationally cheaper and often adequate for calculating low-lying excited states of many organic chromophores. However, if your chromophore exhibits strong excitonic coupling or charge-transfer states (common in photodynamic therapy agents), full BSE may be necessary for accurate prediction of absorption maxima and oscillator strengths. An error > 0.2 eV between TDA and experimental lambda_max suggests you should switch to full BSE. This accuracy is critical for in silico screening of chromophores for targeted phototherapy.

Q5: My FRET-based biosensor shows a low dynamic range. What experimental parameters should I re-examine? A: Low FRET efficiency (dynamic range) can stem from multiple factors. Systematically check: 1) Linker length: The donor (e.g., CFP) and acceptor (e.g., YFP) should be connected by a flexible linker of optimal length (typically 5-10 amino acids). 2) Orientation factor: Ensure the fusion protein does not force an unfavorable relative orientation of the dipoles; try a different linker sequence (e.g., (GGGGS)n). 3) Spectral crosstalk: Perform careful control experiments to calculate and subtract bleed-through. 4) Protein maturity: Allow sufficient time after transfection (24-48 hrs) for proper folding and chromophore maturation at 37°C.

Table 1: Common Photosensitive Proteins for Optogenetics

| Protein | Peak Activation Wavelength (nm) | Typical Activation Light Intensity (mW/mm²) | Key Application | Off-kinetics (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChR2 (H134R) | 470 | 1-5 | Neuronal depolarization | ~10-20 |

| NpHR (Halorhodopsin) | 589 | 5-10 | Neuronal hyperpolarization | ~10 |

| ArchT | 566 | 5-10 | Neuronal hyperpolarization | <10 |

| CheRiff | 460 | 0.1-1 | Cardiomyocyte stimulation | ~7 |

Table 2: Common Drug Chromophores and Their Photophysical Properties

| Chromophore Class | Typical Absorption Max (nm) | Molar Extinction Coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | Primary Biomedical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porphyrin (e.g., Photofrin) | ~630 | ~3,000 | Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) |

| Phthalocyanine | ~670 | >200,000 | PDT, Imaging |

| Indocyanine Green (ICG) | ~780 | ~130,000 | Angiography, Liver function |

| BODIPY dyes | 500-650 | 80,000-100,000 | Bioimaging, Sensing |

| Cyanine dyes (Cy5) | ~649 | 250,000 | Fluorescence labeling |

Table 3: Comparison of BSE@TDA vs. Full BSE for Biomolecular Chromophores

| Computational Metric | BSE@TDA | Full BSE | Notes for Biomedical Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost (Relative) | 1x | 2-3x | TDA enables screening of larger chromophore libraries. |

| Accuracy for Charge-Transfer States | Lower (Error ~0.3-0.5 eV) | Higher (Error ~0.1-0.2 eV) | Critical for designing donor-acceptor systems for phototherapy. |

| Description of Double Excitations | Missing | Included | May be important for UV-absorbing protein chromophores. |

| Typical System Size Limit (atoms) | ~500 | ~200 | TDA is practical for protein-chromophore embedded systems. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Photosensitive Protein Function in Cultured Neurons

- Transfection: Transfect primary neurons at DIV 5-7 with plasmid encoding ChR2-(H134R)-EYFP using calcium phosphate or lipofection.

- Expression: Incubate for 7-10 days to allow sufficient protein expression and trafficking.

- Preparation: Prior to experiment, replace culture medium with extracellular recording solution (e.g., ACSF).

- Stimulation: Using a 470 nm LED system, deliver 5 ms light pulses. Begin at 0.1 mW/mm², increasing until action potentials are reliably evoked (typically 1-5 mW/mm²). Use a TTL pulse to synchronize light delivery and electrophysiology recording.

- Recording: Perform whole-cell patch-clamp in current-clamp mode to record evoked action potentials. Maintain cells at -70 mV holding potential.

- Control: Include non-transfected neurons exposed to the same light regimen to check for light-induced artifacts.

Protocol 2: Conjugating a Drug Molecule to a Cyanine5 (Cy5) Chromophore for Imaging

- Materials: Drug molecule with primary amine, Cy5 NHS ester, anhydrous DMF, triethylamine, PBS (pH 7.4), desalting column.

- Reaction: Dissolve the amine-containing drug (1 equiv) and Cy5 NHS ester (1.2 equiv) in anhydrous DMF to a final concentration of 5-10 mM. Add triethylamine (2 equiv) as a catalyst. Protect from light.

- Incubation: Stir reaction mixture at room temperature for 4-6 hours.

- Purification: Quench reaction by adding 10 vol% of 1M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Purify the conjugate using a PD-10 desalting column equilibrated with PBS. Collect the colored fraction.

- Characterization: Determine concentration via Cy5 absorbance at 649 nm (ε ~250,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹). Verify conjugation via HPLC-MS. Store at -20°C in aliquots, protected from light.

Protocol 3: Measuring Photobleaching Quantum Yield of a Bio-imaging Agent

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a dilute solution of the imaging agent (OD ~0.1 at the excitation peak) in the desired buffer. Degas with nitrogen for 10 minutes to reduce oxygen.

- Reference Standard: Prepare a matched solution of a standard with known photobleaching quantum yield (e.g., fluorescein in 0.1M NaOH, Φ_bleach ~3x10⁻⁵).

- Irradiation: In a spectrofluorometer cuvette, continuously irradiate the sample at the excitation wavelength while stirring. Use a low, calibrated light intensity (measured with a power meter).

- Monitoring: Record the absorption spectrum at regular time intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds for 10 minutes).

- Calculation: Plot the decrease in absorbance at lambdamax versus cumulative photon flux. The slope relative to the standard gives the relative photobleaching quantum yield using the formula: Φsample = Φstandard * (slopesample / slope_standard).

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Optogenetic Experiment Setup and Troubleshooting Flow

Diagram Title: Computational-Experimental Chromophore Development Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Biomedicine Experiments with Light-Activated Agents

| Item | Function | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Photosensitive Protein Plasmid | Genetic material for optogenetic control. | pLenti-CaMKIIα-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP (Addgene #26969) |

| Cell/Tissue Culture Medium (Phenol Red-free) | Supports cell health during imaging; phenol red absorbs light. | Gibco FluoroBrite DMEM |

| NHS-Ester Reactive Dyes | For covalent conjugation of chromophores to drugs/antibodies. | Cyanine5 NHS ester (Lumiprobe) |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Reduces photobleaching & phototoxicity in live-cell imaging. | Oxyrase (Oxyrase, Inc.) or GLOX solution |

| Calibrated Light Source | Provides precise, reproducible light doses for activation/PDT. | Lumencor Spectra X Light Engine |

| Neutral Density Filter Set | Allows fine adjustment of light intensity without changing wavelength. | Thorlabs ND filters |

| Quantum Yield Standard | Essential for quantifying fluorescence efficiency of new agents. | Quinine sulfate in 0.1M H₂SO₄ (Φ=0.577) |

| Anti-fading Mounting Medium | Preserves fluorescence signal in fixed samples. | ProLong Gold (Thermo Fisher) |

| Singlet Oxygen Sensor | Detects and quantifies singlet oxygen production in PDT studies. | Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG, Thermo Fisher) |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Performs BSE/TDA calculations for chromophore design. | VASP, BerkeleyGW, Gaussian |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do my GW-calculated bandgaps remain systematically underestimated compared to experiment, even with a seemingly converged basis set?

- Answer: This often points to insufficient convergence in the polarizability calculation or the dielectric function. The core issue is typically an underconverged number of empty states in the irreducible polarizability (

NbndorNemptyin many codes). Increase this parameter significantly. Also, ensure the frequency grid for the dielectric function is appropriate. For accurate quasiparticle energies, full-frequency integration methods are generally more reliable than plasmon-pole approximations, though computationally heavier.

FAQ 2: During a GW-BSE calculation, I encounter instability or non-physical exciton energies. What could be the cause?

- Answer: This is frequently traced back to the quality of the starting Kohn-Sham (KS) eigenvalues and orbitals used for the GW step. The GW approximation is formally a correction to the KS system. Using a DFT functional with a poor bandgap (e.g., LDA, GGA) can sometimes lead to challenges in the subsequent BSE step. A hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0, HSE) starting point can provide a more stable input. Additionally, ensure the

GWcalculation itself is well-converged, as inaccurate quasiparticle energies directly feed into the BSE Hamiltonian.

FAQ 3: How do I decide between using the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) and the full Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) for my system of interest?

- Answer: The choice is critical for accuracy within the thesis context of comparing TDA vs. full BSE. The TDA neglects the coupling between resonant (excitation) and anti-resonant (de-excitation) transitions, simplifying the BSE. For singlet excitations in many organic molecules and insulating solids, TDA is often an excellent approximation and reduces computational cost. However, for systems where exchange effects are less dominant or where triplet states are of interest, the full BSE may be necessary. A key diagnostic is to run both for a test system: if the difference in low-lying excitation energies is minimal (<0.1 eV), TDA may be sufficient for your study. For metals or systems with strong spin-orbit coupling, full BSE is generally recommended.

FAQ 4: My BSE optical absorption spectrum shows incorrect peak ordering or missing peaks when compared to experimental UV-Vis data. How should I troubleshoot?

- Answer: First, verify the convergence of the BSE Hamiltonian construction. Key parameters are:

- Number of occupied and unoccupied bands in the transition space: This must be large enough to capture the relevant excitations.

- k-point grid: Must be dense enough, especially for low-dimensional systems.

- GW consistency: The BSE should be solved using quasiparticle energies and orbitals from the GW step. Using DFT eigenvalues in the BSE kernel but GW corrections elsewhere is a common source of error. The workflow logic for diagnosing this is shown in Diagram 1.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Standard One-Shot G0W0 Calculation Workflow

- DFT Ground State: Perform a well-converged DFT calculation (using a plane-wave/pseudopotential or localized basis code) to obtain Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and orbitals. Use a hybrid functional (HSE06) if possible for a better starting point.

- Dielectric Matrix Calculation: Compute the irreducible polarizability χ0(iω) over a frequency grid. Converge the number of empty states (often 2-4 times the number of occupied states).

- GW Computation: Construct the screened Coulomb interaction W(iω) = ε^-1(iω) * v. Perform the contour deformation or analytic continuation to compute the GW self-energy Σ(E) = iG * W.

- Quasiparticle Equation: Solve the quasiparticle equation iteratively: Enk^QP = εnk^DFT + Znk * Re⟨ψnk^DFT| Σ(Enk^QP) - Vxc^DFT | ψ_nk^DFT⟩, where Z is the renormalization factor.

Protocol: BSE Optical Spectrum Calculation (TDA vs. Full)

- Prerequisite: Obtain accurate quasiparticle energies (E^QP) and orbitals from a converged GW calculation.

- Build Exciton Hamiltonian: Construct the BSE Hamiltonian in the transition space between valence (v,v') and conduction (c,c') bands: H^(exc) = (Ec^QP - Ev^QP) * δvv'δcc' + K^(dir) - ξK^(xch). ξ=2 for singlets, 0 for triplets. Within TDA, the coupling block between resonant and anti-resonant parts is set to zero.

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian (full or TDA) to obtain exciton eigenvalues (ΩS) and eigenvectors (Avc^S).

- Compute Spectrum: Calculate the imaginary part of the dielectric function ε2(ω) from the exciton weights and energies.

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of TDA vs. Full BSE for Low-Lying Excitations (Example Data)

| System Type | Excitation Energy (TDA) [eV] | Excitation Energy (Full BSE) [eV] | Experimental Ref. [eV] | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Molecule (e.g., Pentacene) S1 | 2.12 | 2.10 | 2.10 | TDA sufficient |

| Inorganic Semiconductor (e.g., MoS2 monolayer) A exciton | 2.02 | 1.95 | 1.90-1.95 | Full BSE |

| Triplet State (T1) in TiO2 | 2.45 | 2.45 | N/A | TDA mandated (ξ=0) |

Table 2: Key Convergence Parameters for GW-BSE Calculations

| Parameter | Symbol (Typical) | Purpose | Convergence Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty States for Polarizability | Nbnd, Nempty |

Build χ0 and ε | Increase until change in QP gap < 0.05 eV |

| k-point Grid | Nkx, Nky, Nkz |

Sampling Brillouin Zone | Increase until optical spectrum features stabilize |

| Frequency Grid Points | Nomega |

Represent ε(iω) | Use ~10-20 points for plasmon-pole, >100 for full-frequency |

| Bands in BSE | Nv, Nc |

Size of exciton Hamiltonian | Include all bands within ~2-3 eV of Fermi level for low-energy spectrum |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Code | Function in GW-BSE Calculations |

|---|---|

| DFT Functional (HSE06/PBE0) | Provides improved starting eigenvalues/orbitals versus LDA/GGA, leading to more stable GW convergence. |

| Plane-Wave Basis Set & Pseudopotentials | Standard framework for periodic systems. Use high-quality, high-cutoff potentials to avoid ghost states. |

| Godby-Needs Plasmon-Pole Model | Approximates the frequency dependence of ε^-1(ω), reducing computational cost versus full-frequency. Can introduce error for systems with complex dielectric functions. |

| Hybertsen-Louie Generalized Plasmon-Pole Model | Another common plasmon-pole approximation, often used in BerkeleyGW suite. |

| Contour Deformation Integration | A full-frequency method to compute Σ(E) accurately by integrating along the real and imaginary axes. More robust but costly than plasmon-pole. |

| Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) | Neglects the coupling between excitations and de-excitations in BSE, simplifying diagonalization. Valid for many insulating systems. |

| Lanczos Diagonalization Algorithm | Efficiently solves for low-lying eigenstates of the large BSE Hamiltonian without full diagonalization. |

Visualization

Diagram 1: BSE Spectrum Error Diagnosis Workflow

Diagram 2: GW Approximation as a Prerequisite for BSE

Computational Workflow: Implementing BSE@GW for Biomolecular Systems Step-by-Step

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting BSE/TDA Calculations

FAQs on Accuracy & Performance

Q1: When using Yambo's BSE solver, I encounter the error "BSE kernel not positive definite." What does this mean in the context of TDA vs. full BSE?

A: This error often arises when the dielectric matrix (screening) is not accurately converged. Within the thesis context, this is critical as it directly impacts the comparison of TDA and full BSE accuracy. The Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) often tolerates slightly less converged screening due to its simplified exciton Hamiltonian (neglecting resonant-antiresonant coupling). For full BSE, which includes these couplings, a more precise and positive definite kernel is required.

- Protocol: Systematically increase the number of G-vectors in the screening (

NGsBlkXd/BndsRnXdin Yambo,nemptyin BerkeleyGW) and the k-point grid. First, converge the screening independently using a simpler GW or RPA calculation before proceeding to the BSE.

Q2: My BSE calculation in BerkeleyGW (epsilon.x/sigma.x/kernel.x workflow) runs out of memory. Does using the TDA offer a memory advantage?

A: Yes, significantly. The full BSE Hamiltonian scales as ~(2NvNcNk)^2, while the TDA Hamiltonian scales as ~(NvNcNk)^2. For large systems, TDA can reduce memory by approximately a factor of 4.

- Protocol: For a memory estimate, use BerkeleyGW's

mbtoolutility. If memory is limiting, adopt TDA as a necessary first step (TDA=Trueinkernel.inp). Document this constraint in your thesis as a practical limitation that may necessitate TDA use for large systems.

Q3: In VASP with ALGO = TDHF, how do I control the use of TDA versus full BSE, and what is the typical accuracy trade-off for optical spectra?

A: In VASP, TDA is invoked by setting LADDER = .FALSE. in the INCAR file. Full BSE (with ladder diagrams) uses LADDER = .TRUE.. The trade-off is computational cost versus accuracy for dark states. TDA often yields accurate optical absorption peaks (bright states) but can introduce larger errors for energetically lower dark excitons, which are crucial for charge transfer processes in photovoltaic materials.

- Protocol: For a comparative study, run identical systems with both settings. Use a well-converged

NBANDSand a sufficient number of occupied (NOMEGA) and virtual (NOMEGAR) frequency points. Compare the first 5-10 exciton energies and oscillator strengths.

Q4: When comparing Yambo (open-source) and VASP (commercial) BSE results for the same system, I see small discrepancies. What are the primary sources?

A: Discrepancies stem from foundational differences:

- Pseudopotentials/PAW Potentials: The underlying ground-state calculation (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO for Yambo vs. VASP) uses different potentials.

- Implementation Details: Form of the exchange-correlation kernel, treatment of the Coulomb truncation, and basis sets (plane-waves vs. projector-augmented waves).

- Default Parameters: Default convergence criteria for screening, k-point interpolation, and solver algorithms (e.g., Haydock vs. diagonalization) differ.

- Protocol: To isolate the BSE implementation difference, use the same ground-state wavefunctions (e.g., from Quantum ESPRESSO) as input for both Yambo and BerkeleyGW, which are more directly comparable. For VASP comparisons, ensure consistent k-points, energy cutoffs, and number of bands in the BSE Hamiltonian.

The following table summarizes typical performance and accuracy metrics based on recent studies and community benchmarks.

Table 1: Comparative Metrics for BSE Solvers (Idealized System: ~50 Atoms)

| Metric | Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) | Full BSE | Notes for Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical CPU Time | 1x (Baseline) | 1.5x - 2.5x | Full BSE cost increase is system-dependent. |

| Peak Memory Use | 1x (Baseline) | ~4x | Critical limiting factor for large unit cells. |

| Optical Gap Error | +0.05 to +0.15 eV | ±0.01 to 0.05 eV (vs. experiment) | TDA systematically overestimates the gap. |

| Bright Exciton Error | Low (< 0.1 eV) | Very Low | TDA is often sufficient for absorption spectra. |

| Dark Exciton Error | Can be High (> 0.2 eV) | Low | Full BSE is essential for correct exciton ordering. |

| Binding Energy (Eb) | Overestimated | Accurate | TDA's overestimation is proportional to Eb. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Convergence for BSE Calculations

- Ground-State: Converge DFT total energy w.r.t. k-points and plane-wave cutoff.

- Quasiparticle Levels: Perform a GW calculation (e.g.,

gw0in Yambo,sigma.xin BGW). Converge parameters:NGsBlkXp(screening cutoff),BndsRnXp(bands in screening), andGbndRnge(bands in self-energy). - BSE Kernel: Converge the BSE specific parameters:

BSENGexx/BSENGBlk(exchange and screening cutoffs), number of valence (BSEBands.v) and conduction (BSEBands.c) bands in the kernel. - BSE Diagonalization: Choose solver (

haydock/davidson/cg). For full spectra,haydockis efficient. For individual excitons,davidsonis required. ConvergeBSEEhEny(energy range) andBDM/BSS(iterations/steps).

Protocol 2: Direct Comparison of TDA vs. Full BSE Accuracy

- Select a benchmark system (e.g., monolayer MoS₂, benzene molecule).

- Using a fully converged set of parameters from Protocol 1, run two identical BSE calculations: one with TDA enabled (

BSSMod= "tda"in Yambo,TDA=Truein BGW,LADDER=.FALSE.in VASP) and one with full BSE. - Extract and compare: a) Optical absorption spectrum, b) Energies and oscillator strengths of the lowest 10 excitons, c) Exciton binding energy (Eb = GW Gap - BSE Gap).

- Correlate the energy differences with the character of the excitons (bright vs. dark, Frenkel vs. charge-transfer).

Visualization: BSE/TDA Workflow & Hamiltonian Structure

BSE/TDA Calculation Decision Workflow

TDA as a Subset of the Full BSE Hamiltonian

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials for BSE Studies

| Item (Software/Code) | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Thesis |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Provides converged DFT wavefunctions and energies as input for Yambo/BerkeleyGW. | Open-source standard ensures reproducibility for Yambo/BGW workflow. |

| VASP | Integrated, all-in-one suite for DFT, GW, and BSE calculations. | Proprietary but robust; excellent for direct A/B testing of TDA vs. full BSE using identical potentials. |

| Yambo | Open-source code specializing in many-body perturbation theory (GW-BSE). | Highly modular; ideal for dissecting individual contributions (Hx, Hdirect) to the BSE Hamiltonian. |

| BerkeleyGW | Open-source code for GW and BSE calculations. | Highly parallelized; efficient for large-scale systems; clear separation of kernel build and solve steps. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions. | Used to interpolate k-points and analyze exciton wavefunction character (bonding vs. charge-transfer). |

| VESTA/XCrySDen | Visualization software for structure and charge densities. | Critical for visualizing exciton wavefunctions to identify bright/dark character and spatial extent. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My DFT ground-state calculation (e.g., using VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) completes, but the subsequent GW step immediately fails with a "Could not find WAVEDER" or similar file error. What is the issue? A: This error typically indicates missing or incorrect pre-requisite files from the DFT step. GW calculations require specific output beyond the standard electronic structure.

- Cause: The DFT run did not calculate or save the unoccupied conduction states or the wavefunction derivative information necessary for constructing the dielectric matrix.

- Solution: Ensure your DFT input file explicitly requests the correct output. For example:

- In VASP, set

LOPTICS = .TRUE.andALGO = ExactorALGO = Normalin theINCARfile of the final DFT iteration. Also, use a sufficientNBANDSto include plenty of unoccupied states. - In Quantum ESPRESSO, use

input_phor setdisk_io='high'and ensure the wavefunctions are properly saved for thepw2gwpost-processing step.

- In VASP, set

- Protocol: Run a verification DFT step with these tags, then proceed to the GW input.

Q2: During the GW calculation, I encounter warnings about "slow GW convergence with empty states" or the band gap oscillates wildly with NBANDS. How do I converge the basis set for unoccupied states?

A: This is a fundamental convergence challenge in GW. The sum over empty states must be carefully checked.

- Cause: The number of empty bands (

NBANDSin VASP,nbndin QE) used to expand the polarizability and self-energy is insufficient. - Solution: Perform a dedicated convergence study. Do not rely on DFT convergence criteria.

- Protocol:

- Start from your fully converged DFT ground state (with a high

ENCUTand densek-mesh). - Run a series of single-shot G0W0 calculations, increasing the

NBANDSparameter systematically (e.g., 1.5x, 2x, 3x the number of occupied bands). - Monitor the quasiparticle HOMO-LUMO gap or a specific band edge energy.

- Plot the result vs.

1/NBANDSand extrapolate to the infinite limit. Use this converged value for production runs.

- Start from your fully converged DFT ground state (with a high

Table 1: Example G0W0 Convergence Study for Silicon (Primitive Cell, 8 atoms)

| NBANDS | Valence Bands | Conduction Bands | GW Band Gap (eV) | Relative Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 32 | 224 | 1.15 eV | - |

| 384 | 32 | 352 | 1.22 eV | +6.1% |

| 512 | 32 | 480 | 1.25 eV | +2.5% |

| 768 | 32 | 736 | 1.26 eV | +0.8% |

| Extrapolated (∞) | 32 | ∞ | ~1.28 eV | - |

Q3: My GW-corrected band structure appears noisy or unphysical. What went wrong in the input preparation? A: This is often due to an inadequate k-point mesh or issues with frequency integration.

- Cause 1: The k-point density used for GW, often taken directly from DFT, is too coarse for accurate integration in the dielectric function.

- Solution: Converge the GW gap with respect to the k-grid. Use a homogeneous mesh. For isolated molecules, a single Γ-point may suffice, but for solids, a dense grid is critical.

- Cause 2: Improper treatment of the frequency dependence of the dielectric function (e.g., using a static approximation or too few frequencies in a contour deformation approach).

- Solution: For codes like VASP, ensure

NOMEGAis sufficiently high (e.g., 50-200) for the frequency grid method. For Berkeley GW, carefully select the integration contour parameters.

Q4: How do I ensure my DFT starting point is appropriate for GW, especially for systems with strong correlation? A: The choice of DFT functional is a critical input preparation step, particularly in the context of BSE research where GW provides the quasiparticle energies.

- Cause: Standard LDA/GGA functionals often have severe band gap underestimation and can misrepresent orbital ordering in correlated systems.

- Solution: Consider using a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06) or even DFT+U for the initial ground state to obtain a better starting wavefunction. However, note that this "pre-scissors" the gap—the final GW correction will be smaller. The best practice is to compare.

- Protocol for Thesis Context (BSE Accuracy):

- Prepare two sets of quasiparticle inputs: one from GGA-DFT and one from HSE06-DFT.

- Perform identical G0W0@GGA and G0W0@HSE06 calculations.

- Use both sets of quasiparticle energies as input for the subsequent BSE (Tamm-Dancoff vs. full) optical spectrum calculation.

- Analyze how the initial functional choice propagates through to the final exciton energies and oscillator strengths, comparing the sensitivity of Tamm-Dancoff vs. full BSE to this starting point.

Table 2: Impact of DFT Starting Point on GW/BSE Results for a Prototype Molecule (e.g., Pentacene)

| DFT Functional | DFT Gap (eV) | G0W0 Gap (eV) | BSE-TD First Exciton (eV) | BSE-Full First Exciton (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | 0.5 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| HSE06 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Experiment | - | ~2.2 | ~1.8 | ~1.8 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: End-to-End Workflow for GW-BSE Calculation (VASP Example) Objective: Calculate the quasiparticle band structure and optical absorption spectrum.

- DFT Ground State: Perform a fully converged DFT run with

ISMEAR=0; SIGMA=0.05; LOPTICS=.TRUE.; ALGO=Exact; NBANDS=[High Value]. - GW Calculation: Copy the

WAVECARandWAVEDERfiles. Run a one-shot G0W0 calculation withALGO=GW; NOMEGA=64; NBANDS=[Converged Value]. Monitor convergence inOUTCAR. - Quasiparticle Extraction: Use tools like

vaspkitor parsevasprun.xmlto extract thek-dependent quasiparticle energies (EnkQP). - BSE Input Preparation: Create a new calculation directory. Copy the ground-state

WAVECAR. Prepare anINCARwithALGO=BSE; NBANDSBSE=[Val+Cond Bands]; NBANDSO=BSE Bands];ANTIRES=0(Tamm-Dancoff) or2(full BSE). TheKPOINTSfile should be dense. - BSE Execution: Run the BSE calculation. The optical spectrum is in

vasprun.xml(dielectric function).

Protocol 2: Convergence Testing for GW Plasmon-Pole Models Objective: Assess the accuracy of the plasmon-pole model (PPM) approximation vs. full-frequency integration for your system.

- Prepare identical inputs from a converged DFT run.

- Run two GW calculations: one using the Godby-Needs PPM (

LSPECTRAL=.TRUE.) and one using the contour deformation method (LSPECTRAL=.FALSE.; NOMEGA=128). - Compare the resulting quasiparticle gaps and, crucially, the screened potential W(ω) at relevant frequencies.

- Document the computational cost difference. This is vital for justifying method choice in a thesis comparing BSE approximations, as the accuracy of W directly impacts the Bethe-Salpeter kernel.

Visualizations

Title: End-to-End GW-BSE Calculation Workflow and Validation

Title: Thesis Framework: Input Dependence of BSE Solver Accuracy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for GW-BSE Calculations

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Key Consideration for Input Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Performs DFT, GW, and BSE calculations in an integrated suite. | Ensure version compatibility (e.g., v.6.x has improved BSE). Correct INCAR tags for file generation are critical. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source suite for DFT (pw.x) and post-processing for GW (Yambo). | Requires careful workflow scripting (pw.x -> pw2gw.x -> yambo). Wavefunction conversion is a key step. |

| BerkeleyGW | High-accuracy GW and BSE package, often used with QE. | Demands stringent convergence tests. The epsilon executable for the dielectric matrix is computationally intensive. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally-localized Wannier functions. | Used for interpolating GW band structures to very dense k-meshes. The initial projection guess is an important input. |

| VASPKIT | A post-processing toolkit for VASP. | Used to extract quasiparticle band structures, density of states, and help construct BSE k-point grids from GW output. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary CPU/GPU cores and memory. | GW-BSE jobs are massively parallel. Queue settings (walltime, cores) must match the calculation size. Storage for large temporary files (e.g., WFN, W*) is essential. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) absorption spectrum shows unphysical spikes or oscillations. What key parameters should I check? A: This is often a k-point convergence issue. First, systematically increase the k-point grid density (e.g., from 4x4x4 to 8x8x8 to 12x12x12) while monitoring the exciton energy and oscillator strength. Ensure the total energy of the underlying DFT calculation is converged with respect to k-points first. Second, check the number of bands included in the BSE Hamiltonian. If too few conduction bands are included, the spectral shape will be incorrect. A convergence test on the number of bands (both valence and conduction) is mandatory.

Q2: How do I choose the dielectric matrix cutoff (for the screening in BSE) and how does it relate to the NBANDS parameter in the underlying GW calculation?

A: The dielectric matrix cutoff (ENCUTGW or ENCUTEPS in VASP) controls the plane-wave basis set for the reciprocal-space representation of the dielectric function ε. A value too low leads to an inaccurate screening and thus incorrect exciton binding energies. It should typically be equal to or slightly lower than the ENMAX of the pseudopotential. Crucially, the number of bands (NBANDS) in the preceding GW calculation must be high enough to achieve convergence for this chosen cutoff. A rule of thumb is NBANDS ≈ 2-3 times the number of plane-waves determined by ENCUTGW. Failure to converge NBARDS for a given ENCUTGW is a common source of error.

Q3: When using the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA), my low-energy exciton binding energy is overestimated compared to experimental results. Is this a parameter issue? A: Not necessarily. The TDA, which neglects the resonant-antiresonant coupling in BSE, systematically increases exciton binding energies, particularly for strongly bound excitons. Before attributing discrepancy to TDA, you must ensure full parameter convergence. Perform a triple-convergence test for: 1) k-points, 2) number of bands in BSE, and 3) dielectric matrix cutoff. Only after confirming these are converged can you attribute the overbinding to the TDA's inherent approximation, a key point of comparison in TDA vs. full-BSE research.

Q4: My BSE calculation is computationally prohibitively expensive. What is the most effective parameter to reduce for a preliminary test? A: For a preliminary, qualitative test, you can first reduce the k-point grid (using a Γ-centered, even grid) and the number of bands in the BSE kernel. However, note that this will give non-quantitative results. The dielectric matrix cutoff should not be reduced drastically as it can lead to severe inaccuracies. The most rigorous approach to reduce cost is to use a well-converged coarse k-grid and then apply k-point interpolation (Wannier interpolation) to achieve a denser sampling.

Table 1: Convergence Test for a Prototype Semiconductor (e.g., Bulk Silicon)

| Parameter | Tested Values | Convergence Criterion (ΔE < 0.05 eV) | Impact on Exciton Binding Energy (eV) | Computational Cost Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-point Grid | 4x4x4, 6x6x6, 8x8x8, 10x10x10 | Achieved at 8x8x8 | 2.10, 2.05, 2.01, 2.00 | ~Nₖ³ |

| BSE Bands | 4v/4c, 8v/8c, 12v/12c, 16v/16c | Achieved at 12v/12c | 1.50, 1.95, 2.01, 2.01 | ~Nbands² |

| Dielectric Cutoff (eV) | 150, 200, 250, 300 | Achieved at 250 | 1.88, 2.00, 2.01, 2.01 | ~ENCUTGW³ |

Table 2: TDA vs. Full BSE Comparison (Converged Parameters)

| System (Example) | TDA Exciton Energy (eV) | Full BSE Exciton Energy (eV) | Δ (TDA - BSE) (eV) | Binding Energy Overestimation by TDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Silicon | 3.35 | 3.32 | +0.03 | ~5% |

| MoS₂ Monolayer | 2.10 | 2.05 | +0.05 | ~10% |

| Organic Molecule (Crystal) | 4.80 | 4.75 | +0.05 | ~8% |

Experimental Protocol: BSE/TDA Convergence Workflow

Protocol 1: Systematic Convergence of Key Parameters

- DFT Ground State: Perform a well-converged DFT calculation. Converge total energy with respect to k-points and plane-wave cutoff (

ENCUT). - GW Quasiparticle Band Structure: Compute the electronic screening (GW) with a coarse k-grid and band number. Then, converge:

ENCUTGW(Dielectric cutoff): Increase until the band gap changes by < 0.05 eV.NBANDSin GW: For your chosenENCUTGW, increaseNBANDSuntil the band gap converges.

- BSE/TDA Exciton Calculation:

- K-points: Using a fixed, sufficient number of bands and converged

ENCUTGW, increase the k-grid until the lowest exciton energy converges. - Bands in BSE Kernel: Using the converged k-grid and

ENCUTGW, increase the number of valence and conduction bands in the BSE Hamiltonian until the exciton energy converges. - Final Check: Re-check k-point convergence with the final, large number of BSE bands.

- K-points: Using a fixed, sufficient number of bands and converged

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Materials

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Relevance to BSE/TDA Research |

|---|---|---|

| VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, BerkeleyGW | Primary ab initio software packages for performing DFT, GW, and BSE calculations. | Core engines for generating all data. Understanding their input parameters (e.g., ENCUTGW, NBANDS) is critical. |

| Wannier90 | Tool for generating maximally localized Wannier functions. | Enables k-point interpolation, drastically reducing the cost of obtaining converged BSE spectra on dense k-grids. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary CPU/GPU cores and memory for large-scale many-body perturbation theory calculations. | BSE calculations are O(N⁴) scaling; essential for convergence testing. |

| Python (NumPy, Matplotlib, ASE) | Scripting and data analysis environment. | Used to automate convergence loops, parse output files, and visualize spectra and convergence trends. |

| Pseudopotential Library | Curated set of projector-augmented wave (PAW) or norm-conserving pseudopotentials. | The foundational "reagent" defining the ionic cores. Accuracy of the GW/BSE result depends strongly on pseudopotential quality. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My BSE/TDA calculation yields negative excitation energies. What is the cause and how can I resolve this? A: Negative excitation energies typically indicate a violation of the adiabatic approximation or an instability in the reference ground state, often due to an inadequate starting point (e.g., DFT functional with a low exact exchange fraction). To resolve this: 1) Verify the quality of your ground-state DFT calculation by checking for orbital instabilities. 2) For molecules, try using a hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) with a tuned exact exchange percentage. 3) For extended systems, ensure your k-point sampling is sufficiently dense. 4) As a diagnostic, run a full BSE calculation (without TDA); if the issue persists, the problem is likely with the ground state.

Q2: The oscillator strength for my first excited state is zero. Is this an error? A: Not necessarily. A zero oscillator strength indicates a symmetry-forbidden or dark transition. First, check the symmetry of the initial and final states. In molecules with high symmetry (e.g., centrosymmetric), transitions between states of the same parity may be dipole-forbidden. You can verify by analyzing the transition density matrix. If the state is meant to be bright, check for possible errors in the orientation of the molecule or the system's dipole operator implementation in your code.

Q3: My computed BSE/TDA absorption spectrum shows a significant blue or red shift compared to experiment. What parameters should I adjust? A: Systematic shifts are common and require careful calibration.

- Blue Shift: Often due to overestimation of the quasiparticle band gap in the underlying GW calculation. Consider using a more sophisticated GW approach (e.g., partially self-consistent GW0) or empirically scissor-adjust the gap based on experiment.

- Red Shift: Can arise from insufficient electron-hole correlation. Ensure you are including a sufficient number of valence and conduction bands in the BSE Hamiltonian construction. Increasing the number of bands can redshift the spectrum.

Q4: How do I choose between the BSE/Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) and the full BSE for my system? A: The choice depends on system type and computational resources.

- Use BSE/TDA for large systems (nanoparticles, polymers) where computational cost is prohibitive. It is generally accurate for spin-singlet excitations in organic systems and for calculating optical absorption spectra.

- Use full BSE for systems where electron-hole coupling to de-excitations is critical: for molecules requiring high accuracy in transition energies, for triplet excitations, or when analyzing energy transfer processes. Full BSE is essential for a rigorous assessment of TDA's accuracy within your thesis research.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of BSE/TDA and Full BSE Performance for Prototypical Systems

| System (Example) | Excitation Energy (BSE/TDA) [eV] | Excitation Energy (Full BSE) [eV] | Oscillator Strength (BSE/TDA) | Oscillator Strength (Full BSE) | Experimental λ_max [eV] | Key Takeaway for Thesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentacene (Singlet) | 2.12 | 2.10 | 0.45 | 0.48 | ~2.10 | TDA excellent for low-lying bright singlet; minor redshift from full BSE. |

| TiO2 Cluster (S0→S1) | 3.85 | 3.78 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ~3.80 | TDA reliable for inorganic semiconductor gaps; dark state character preserved. |

| Chlorophyll a (Qy band) | 1.88 | 1.82 | 0.076 | 0.081 | 1.83 | Full BSE provides better agreement, suggesting de-excitation coupling is non-negligible. |

| [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (MLCT) | 2.95 | 2.85 | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | 2.90 | TDA can overestimate energy for charge-transfer states; full BSE critical for accuracy. |

Table 2: Impact of Computational Parameters on BSE/TDA Output

| Parameter | Typical Value Range | Effect on Excitation Energy | Effect on Oscillator Strength | Recommended Protocol for Thesis Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW Band Gap (Scissor) | ±0.5 eV | Linear shift (~1:1) | Minimal | Always report the GW gap used. Perform a sensitivity analysis. |

| Number of Bands (Nv, Nc) | 50-500 bands | Converges, may redshift | Converges, can change shape | Perform convergence for each new system class. |

| k-point Sampling | 3x3x3 to 12x12x12 | Critical for solids; coarser grids blue-shift | Affects intensity distribution | Always test k-point convergence for periodic systems. |

| Dielectric Screening | RPA vs. Model | Affects electron-hole interaction strength | Can modify relative peak intensities | Document the screening model (e.g., Godby-Needs). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking BSE/TDA Accuracy vs. Full BSE Objective: To quantify the error introduced by the Tamm-Dancoff approximation for a set of molecules with known high-accuracy experimental or theoretical reference data.

- System Selection: Curate a set of 10-20 molecules spanning small organics (e.g., benzene), charge-transfer complexes (e.g., TCNE-tetracene), and metal-organic complexes.

- Computational Setup:

- Perform ground-state DFT with a hybrid functional (PBE0) and a triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) using a quantum chemistry code (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA).

- Generate input files for a GW-BSE code (e.g., BerkeleyGW, VASP, Turbomole).

- Run GW@PBE0 to obtain quasiparticle energies. Use an identical plane-wave cutoff or basis for all systems.

- Construct and diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian with and without the TDA.

- Data Collection: Extract the first 5-10 singlet excitation energies and their corresponding oscillator strengths from both calculations.

- Analysis: Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) and maximum deviation for BSE/TDA versus full BSE. Correlate deviations with physical properties (e.g., exciton binding energy, charge-transfer distance).

Protocol 2: Generating an Absorption Spectrum from BSE Output Objective: To convert a discrete set of excitations into a broadened spectrum comparable to experiment.

- Run BSE Calculation: Execute a BSE/TDA or full BSE calculation to obtain a dense list of excited states (energies E_i and oscillator strengths f_i).

- Apply Broadening: Broaden each discrete peak using a lineshape function, typically a Gaussian or Lorentzian. The absorption spectrum A(E) is computed as: A(E) = Σ_i f_i * L(E - E_i, η) where L is the lineshape function and η is the broadening parameter (0.05-0.15 eV for room-temperature solids/liquids).

- Plotting: Plot A(E) vs. E (in eV) or wavelength (nm). Ensure the broadening does not obscure distinct spectral features. Compare directly to experimental UV-Vis data, aligning the energy scale (often the first major peak).

Mandatory Visualization

Title: BSE/TDA vs Full BSE Computational Workflow

Title: Troubleshooting Spectral Shifts in BSE Calculations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for GW-BSE Studies

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Notes for Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code (e.g., ORCA, Gaussian, Q-Chem) | Performs initial ground-state DFT calculation, generates molecular orbitals and basis set data. | Essential for preparing input. Use consistent functional/basis for benchmarking. |

| GW-BSE Software (e.g., BerkeleyGW, VASP, TURBOMOLE, ABINIT) | Solves the GW equations for quasiparticle energies and the Bethe-Salpeter equation for excitons. | Core tool. Document version and key input flags (e.g., TDA=.TRUE./.FALSE.). |

| Pseudopotential Library (e.g., PseudoDojo, GBRV) | Represents core electrons, defining the electron-ion interaction in plane-wave codes. | Critical for solids/nanostructures. Must be consistent between DFT, GW, and BSE steps. |

| Visualization Suite (e.g., VMD, VESTA, Matplotlib, Grace) | Analyzes orbitals, transition densities, and plots absorption spectra. | For analyzing exciton wavefunction spatial extent (key for CT states). |

| Benchmark Database (e.g., NIST Computational Chemistry, TheoChem) | Provides high-quality experimental and theoretical reference excitation energies. | Used to validate and quantify the accuracy of BSE/TDA vs. full BSE. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My BSE@Tamm-Dancoff calculation yields an absorption peak that is significantly blue-shifted compared to experimental data for a GFP chromophore model. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: This is a common issue. The primary causes and mitigation strategies are:

- Cause 1: Inadequate treatment of the protein environment (dielectric screening) and geometrical constraints.

- Solution: Employ an implicit solvation model (e.g., C-PCM, SMD) with a tuned dielectric constant (ε > 4). Consider a QM/MM approach for higher accuracy.

- Cause 2: The underlying DFT functional (e.g., PBE, B3LYP) underestimates the HOMO-LUMO gap.

- Solution: Use a range-separated or tuned hybrid functional (e.g., CAM-B3LYP, ωB97XD) for more accurate excitation energies. Validate with a higher-level method (e.g., CC2) on a smaller model.

- Cause 3: The chromophore geometry from ground-state optimization is not representative of the experimental Franck-Condon point.

- Solution: Confirm geometry with a method that accounts for dynamic electron correlation. Consider constrained optimizations based on crystal structure data.

Q2: When should I use the full Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) instead of the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) for fluorescent protein chromophores?

A: Use the full BSE when:

- You are studying systems where excitonic coupling and electron-hole correlation beyond the TDA are critical.

- You require absolute accuracy for oscillator strengths and for states with significant double-excitation character.

- Your research thesis involves benchmarking TDA accuracy against the full BSE for biochromophores.

- Note: For most fluorescent protein chromophores (like GFP), TDA is often sufficient for the primary absorption peak and is computationally cheaper. The full BSE is more important for charge-transfer excitations or detailed lineshape analysis.

Q3: I encounter convergence issues in the GW step for calculating the quasiparticle bandgap. How can I stabilize this calculation?

A: Convergence problems in the GW step often stem from the frequency integration and the dielectric matrix.

- Action 1: Increase the number of empty states (

NBANDSin VASP,nemptyin Yambo) by at least a factor of 3-4 relative to the DFT calculation. - Action 2: Use a plasmon-pole model (e.g., Godby-Needs) instead of full frequency integration for initial scans.

- Action 3: Ensure your DFT ground state is well-converged regarding k-points and plane-wave cutoff energy. A poor starting point hinders GW convergence.

Experimental Protocols for Cited Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Benchmarking BSE@TDA vs. Full BSE for a Model Chromophore (in vacuo)

- System Preparation: Obtain the gas-phase geometry of the anionic form of the p-hydroxybenzylidene-2,3-dimethylimidazolinone (HBDI) chromophore from a benchmark database (e.g., WEBS database) or optimize using CAM-B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) with tight convergence criteria.

- Ground-State DFT: Perform a DFT calculation using the PBE0 functional and a def2-TZVP basis set. Compute the ground-state electron density and Kohn-Sham orbitals.

- GW Calculation: Compute quasiparticle energies via a one-shot G0W0 calculation on top of the PBE0 starting point. Use a plasmon-pole approximation. Confirm convergence with respect to empty states (~500-1000).

- BSE Setup: Construct the Bethe-Salpeter Hamiltonian using the GW-corrected energies and the static DFT screening.

- Spectral Calculation:

- a. Solve the BSE within the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA).

- b. Solve the full BSE (coupling resonant and anti-resonant parts).

- Analysis: Extract the lowest 5 singlet excitation energies and oscillator strengths. Broadening: Apply a Gaussian lineshape with a 0.1 eV FWHM to generate spectra.

Protocol 2: Calculating the Solvated Chromophore Absorption with Implicit Solvation

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the chromophore structure using the range-separated functional ωB97XD and the 6-31+G* basis set, embedded in an implicit solvent model (e.g., IEF-PCM with ε=4.0 to mimic protein environment).

- GW-BSE Workflow: Use the optimized geometry to run a combined G0W0-BSE calculation. Employ the same functional (ωB97XD) as the starting point for GW.

- Screening Model: For the BSE, use a static screening model derived from the random-phase approximation (RPA) within the same implicit solvent cavity.

- Validation: Compare the calculated lowest excitation energy (S0→S1) with the experimentally known 0-0 absorption energy for the specific fluorescent protein (e.g., ~2.5 eV for GFP).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Benchmark of Calculated S0→S1 Excitation Energy (eV) for HBDI Chromophore (in vacuo)

| Method / Approximation | Excitation Energy (eV) | Oscillator Strength (f) | Deviation from Exp.* |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBE0/TDA | 2.85 | 1.12 | +0.35 |

| CAM-B3LYP/TDA | 2.58 | 1.08 | +0.08 |

| G0W0@PBE0 + BSE (TDA) | 2.65 | 0.98 | +0.15 |

| G0W0@PBE0 + full BSE | 2.52 | 1.05 | +0.02 |

| Experimental Reference* | ~2.50 | - | - |

*Experimental estimate from gas-phase or low-temperature matrix studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Role / Function | Typical Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Code (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Performs ground-state DFT geometry optimizations and TD-DFT reference calculations. | Required for initial structure preparation and low-cost benchmarks. |

| GW-BSE Software (e.g., VASP, Yambo, BerkeleyGW) | Solves the GW approximation for quasiparticle energies and the Bethe-Salpeter Equation for excitons. | Core tool for the case study workflow. Check for solvent model compatibility. |

| Implicit Solvation Model | Mimics the electrostatic effect of the protein pocket and solvent on the chromophore. | Critical for accurate peak position. Use a dielectric constant ε between 4 (protein) and 80 (water). |

| Basis Set Library (e.g., def2-TZVP, 6-311+G(d,p)) | Set of mathematical functions describing electron orbitals. | Larger, polarized, and diffuse-augmented basis sets improve accuracy but increase cost. |

| Visualization Tool (e.g., VMD, ChemCraft) | Analyzes molecular orbitals, electron density differences, and excitation character. | Essential for interpreting the nature of the excited state (e.g., π→π*). |

Mandatory Visualization

Title: GW-BSE Computational Workflow for Absorption Spectra

Title: TDA vs Full BSE Decision Factors in Thesis Context

Solving Convergence Challenges & Optimizing BSE/TDA Calculations for Large Systems

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) calculation in the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) fails to converge for the exciton binding energy when I reduce the k-point mesh spacing below 0.15 Å⁻¹. Why does this happen?

A: This is a common pitfall where improved k-sampling exposes a pathological interaction between the dielectric screening model and the Coulomb truncation scheme. In the TDA, the exciton Hamiltonian is sensitive to long-range interactions. When using a crude k-mesh, the numerical inaccuracies can accidentally dampen this sensitivity. Finer sampling more accurately captures the divergence of the unscreened Coulomb kernel (v) at Γ, which can destabilize convergence if the static dielectric matrix (ε⁻¹) is not treated with consistent precision. This is particularly acute when using a model dielectric function (e.g., RPA) that has not fully converged in reciprocal space.

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Isolate the Variable: Run a series of single-shot BSE@TDA calculations (no self-consistency) on a fixed set of GW quasiparticle energies.

- Systematic Variation: Vary only the

Nk(k-points) for the BSE kernel, while keeping the k-grid for the preceding GW and the dielectric function ε(ω=0) calculation constant and coarse (e.g., 6x6x6). - Monitor: Track the eigenvalue of the lowest bright exciton as a function of BSE

Nk. Observe the point of divergence. - Solution: Recalculate the static dielectric matrix

ε⁻¹(q→0,G,G')on the same fine k-point grid used for the BSE. Ensure the Coulomb truncation (e.g., for 2D materials) is applied after the dielectric matrix is built.

Q2: I am comparing TDA vs. full BSE results. The exciton binding energy differs by >30% for a charge-transfer exciton, but the screening layer thickness parameter seems arbitrary. How do I determine it rigorously?

A: This discrepancy highlights a key thesis context: the full BSE, which includes resonant-antiresonant coupling, is more sensitive to the long-range spatial decay of the screened Coulomb interaction W(r,r') for charge-transfer states. The common pitfall is using a bulk-like or default screening model for low-dimensional or heterogeneous systems. The "screening layer thickness" is not a free parameter but should be derived from the electronic decay length of your system's environment.

Experimental Protocol for Determining Screening:

- Compute Projected DOS: Calculate the layer- or fragment-projected density of states for your system (e.g., donor/acceptor molecules, substrate/adsorbate).

- Fit Dielectric Profile: From the macroscopic component of the calculated dielectric function

ε_M(q→0,ω=0), extract the screening length λ viaε(q) ~ 1 + (4πλ²)/q²for 2D/embedded systems. - Benchmark with Full BSE: Use this λ as an initial constraint in a model screening function (e.g., Keldysh, Rytova-Keldysh). Perform full BSE calculations (with exchange and direct screened terms) for a known charge-transfer exciton in your system.