CCSD(T) vs DFT: Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions for Drug Development

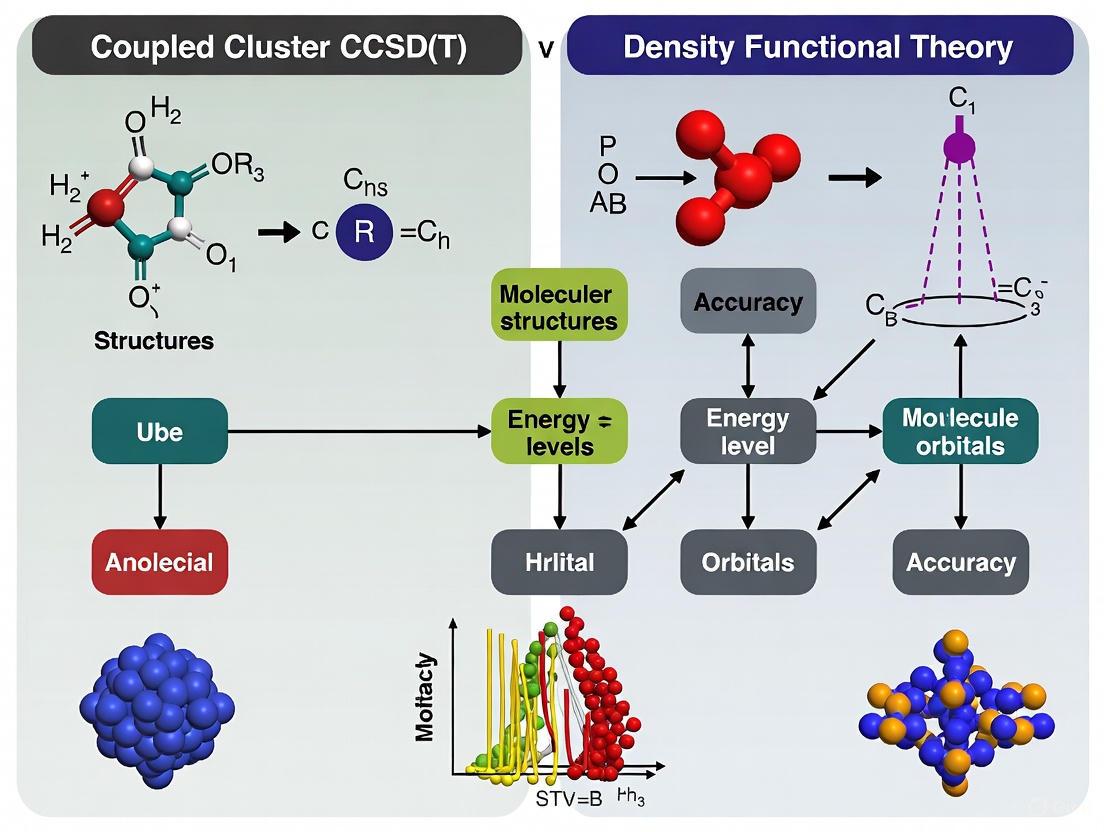

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the coupled-cluster CCSD(T) method and Density Functional Theory (DFT) for researchers and drug development professionals.

CCSD(T) vs DFT: Accuracy, Applications, and Future Directions for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the coupled-cluster CCSD(T) method and Density Functional Theory (DFT) for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of both methods, with CCSD(T) established as the gold standard for quantum chemical accuracy and DFT praised for its computational efficiency. The content covers cutting-edge methodological advancements, including machine learning acceleration and automated multiconfigurational approaches, that are bridging the accuracy-efficiency gap. Practical guidance for troubleshooting common errors and selecting appropriate methods for specific applications in biomolecular systems is provided. Finally, we validate these approaches through comparative benchmarking studies and discuss the transformative implications of these computational techniques for accelerating drug discovery and materials design.

Quantum Chemistry Foundations: Understanding the CCSD(T) Gold Standard and DFT Workhorse

The evolution of materials science from the mystical practices of alchemy to today's sophisticated computational methods represents one of the most significant transformations in scientific history. For over a millennium, investigators attempted to create valuable materials through trial and error, mixing substances like lead, mercury, and sulfur in hopes of producing gold—a pursuit that engaged even renowned scientists like Tycho Brahe, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton [1]. The development of the periodic table provided a fundamental framework, but true predictive capability remained elusive until the advent of quantum mechanics and computational chemistry.

In contemporary research, two computational methodologies dominate the landscape of electronic structure determination: Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Coupled Cluster Theory (CCSD(T)). These approaches represent different trade-offs between computational accuracy and efficiency, with DFT serving as a versatile workhorse for large systems, and CCSD(T) providing the gold standard for accuracy in quantum chemistry [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, examining their performance across various chemical systems and applications relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations: Mapping the Electronic Structure Problem

Density Functional Theory (DFT)

DFT is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems, particularly atoms, molecules, and condensed phases [2]. Its foundation rests on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which demonstrate that all properties of a many-electron system can be determined through functionals of the electron density—functions that take another function as input and produce a real number as output [2].

In practice, DFT reduces the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons to a tractable problem of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential [2]. The key advantage lies in using the electron density n(r)—which depends on only three spatial coordinates—rather than dealing with the many-body wavefunction that depends on 3N coordinates for N electrons [2]. The total energy functional in DFT can be expressed as:

Where T[n] represents the kinetic energy functional, U[n] accounts for electron-electron interactions, and the final term describes the interaction with the external potential [2]. The difficulty in DFT lies in accurately modeling the exchange and correlation interactions, which must be approximated.

Coupled Cluster Theory (CCSD(T))

Coupled cluster theory, particularly the CCSD(T) variant that considers single, double, and perturbative triple excitations, systematically approaches the exact solution to the Schrödinger equation [3]. This method is considered the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry due to its high accuracy, but comes with significantly higher computational cost [1]. The scaling is notoriously unfavorable: doubling the number of electrons in a system makes computations approximately 100 times more expensive, traditionally limiting CCSD(T) applications to molecules with about 10 atoms or fewer [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of DFT and CCSD(T) Methodologies

| Feature | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Coupled Cluster CCSD(T) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Electron density functionals [2] | Wavefunction expansion [3] |

| Computational Scaling | Favorable (N³ typically) | Unfavorable (N⁷ or worse) [1] |

| Key Approximation | Exchange-correlation functional [2] | Excitation truncation [3] |

| System Size Limit | Thousands of atoms [1] | Dozens of atoms (traditionally) [1] |

| Primary Application | Ground-state properties of large systems [2] | High-accuracy benchmark calculations [3] |

Comparative Accuracy Across Chemical Systems

Main-Group Element Clusters

Studies on aluminum clusters (Alₙ, where n = 2-9) reveal telling differences between DFT and CCSD(T) performance. When calculating electron affinities and ionization potentials, the PBE0 functional with aug-cc-pVTZ basis set shows average error differences of 0.14 eV and 0.15 eV respectively compared to experimental data [4]. The CCSD(T) calculations with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation, however, achieve even better agreement with experimental values, with errors of only 0.11 eV and 0.13 eV respectively [4].

Transition Metal Complexes

For zirconocene complexes relevant to ethylene polymerization catalysis, DFT generally reproduces atomic ionization potentials and redox potentials with good accuracy [5]. However, significant deviations emerge for bond dissociation energies (BDEs), suggesting that experimental values for these complexes may need reevaluation based on CCSD(T) calculations, which provide more reliable benchmarks [5]. This performance pattern highlights DFT's adequacy for certain electronic properties while revealing limitations in describing precise energy landscapes for catalytic processes.

Organic Molecules and Drug-like Compounds

The development of the ANI-1ccx neural network potential, trained to approach CCSD(T)/CBS accuracy, provides valuable insights into DFT limitations for organic systems [3]. When benchmarked against CCSD(T)/CBS references for reaction thermochemistry, isomerization, and drug-like molecular torsions, DFT methods show systematic deviations that machine learning approaches can mitigate while maintaining computational efficiency [3].

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison Across Chemical Systems (Mean Absolute Deviations)

| System Type | Property | DFT Performance | CCSD(T) Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Clusters [4] | Ionization Potential | 0.15 eV (PBE0) | 0.13 eV (CBS) |

| Aluminum Clusters [4] | Electron Affinity | 0.14 eV (PBE0) | 0.11 eV (CBS) |

| Organic Molecules [3] | Isomerization Energy | 5.0 kcal/mol (ωB97X) | Benchmark (ANI-1ccx: 1.3 kcal/mol) |

| Organic Molecules [3] | Reaction Thermochemistry | Varies by functional | Benchmark (ANI-1ccx: ~1.0 kcal/mol) |

| Zirconocene Catalysts [5] | Bond Dissociation Enthalpies | Large deviations | Most accurate values |

Computational Cost and Scalability

The computational expense of these methods represents a critical practical consideration for researchers. CCSD(T) calculations scale so steeply that doubling the number of electrons increases computational cost by approximately two orders of magnitude, creating an effective limit of about 10 atoms for traditional applications [1]. In contrast, DFT calculations scale more favorably, typically with the cube of system size, enabling applications to systems containing thousands of atoms [1].

This dramatic difference has historically created a stark choice for researchers: rapid computation with moderate accuracy (DFT) or high accuracy with extreme computational cost (CCSD(T)). However, recent advances are blurring these boundaries. Machine learning approaches like the MEHnet architecture developed at MIT can perform CCSD(T)-equivalent calculations much faster by leveraging neural networks trained on high-quality quantum chemical data [1]. Similarly, the ANI-1ccx potential achieves CCSD(T)/CBS accuracy while being "billions of times faster" than direct CCSD(T) calculations [3].

Computational Method Applicability

Emerging Hybrid and Machine Learning Approaches

Neural Network Architectures

The "Multi-task Electronic Hamiltonian network" (MEHnet) developed by MIT researchers represents a significant advancement in computational chemistry [1]. This E(3)-equivariant graph neural network utilizes nodes to represent atoms and edges to represent bonds, incorporating physics principles directly into the model architecture [1]. Unlike traditional DFT, which primarily provides total energy, MEHnet can evaluate multiple electronic properties simultaneously, including dipole and quadrupole moments, electronic polarizability, optical excitation gaps, and infrared absorption spectra [1].

Transfer Learning Paradigms

The ANI-1ccx potential demonstrates how transfer learning can bridge the accuracy-efficiency gap [3]. This approach begins by training a neural network on large quantities of lower-accuracy DFT data (5 million molecular conformations), then retrains on a much smaller set of intelligently selected conformations with CCSD(T)/CBS level accuracy [3]. The resulting potential exceeds DFT accuracy for isomerization energies, reaction energies, and molecular torsion profiles while maintaining computational efficiency [3].

Functional Development

New exchange-correlation functionals continue to emerge, addressing specific limitations of traditional DFT. Microsoft Research's "Skala" functional applies deep learning to achieve near-chemical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, potentially enabling molecular and materials design through simulation rather than extensive laboratory experimentation [6].

Table 3: Machine Learning Approaches in Quantum Chemistry

| Method | Architecture | Training Data | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEHnet [1] | E(3)-equivariant graph neural network | CCSD(T) on small molecules | Multi-property prediction, excited states |

| ANI-1ccx [3] | Ensemble neural network | Transfer learning: DFT then CCSD(T) | CCSD(T) accuracy with DFT cost |

| Skala Functional [6] | Deep learning for XC functional | Not specified | Near chemical accuracy, low cost |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Accuracy Validation Protocols

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental data and high-level theoretical references is essential for method validation. For aluminum clusters, researchers compared DFT (PBE0, M05-class, M06-class) and CCSD(T) results for geometries, vibrational frequencies, binding energies, and electronic properties against experimental measurements where available [4]. Similarly, zirconocene catalyst studies evaluated DFT performance against experimental redox potentials and bond dissociation enthalpies, with CCSD(T) serving as an authoritative reference [5].

Cost-Effectiveness Assessment

For practical applications, researchers have developed frameworks for cost-effective computational analysis. Studies on equilibrium isotopic fractionation in large organic molecules evaluated multiple DFT functionals against experimental datasets, identifying O3LYP/def2-TZVP as having the lowest mean absolute deviation (21‰ for H, 3.9‰ for heavy atoms) [7]. Such systematic assessments enable researchers to select appropriate methods based on their specific accuracy requirements and computational resources.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Electronic Structure

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools in Quantum Chemistry

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PySCF [8] | Python-based quantum chemistry package | DFT, CCSD(T), and post-Hartree-Fock calculations |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [3] | Python package for atomistic simulations | Interface for ML potentials like ANI-1ccx |

| ANI-1ccx Potential [3] | ML potential approaching CCSD(T) accuracy | High-accuracy calculations for organic molecules |

| MEHnet Architecture [1] | Multi-task neural network for electronic properties | Simultaneous prediction of multiple molecular properties |

| def2-TZVP Basis Set [7] | Triple-zeta quality basis set with polarization | Balanced accuracy/cost for DFT calculations |

The quantum chemistry landscape continues evolving from its alchemical roots toward increasingly predictive computation. DFT remains indispensable for large systems due to its favorable scaling, while CCSD(T) provides the accuracy benchmark for smaller molecules [1] [3]. The most promising developments emerge at the intersection of these approaches, where machine learning architectures leverage the strengths of both methods [1] [3].

Future research directions likely include extending CCSD(T)-level accuracy to broader regions of the periodic table, further reducing computational costs for large systems, and improving the description of challenging electronic phenomena like strong correlation and dispersion interactions [1]. As these methods mature, computational prediction will play an increasingly central role in materials design, drug development, and sustainable energy technologies, potentially transforming the traditional trial-and-error experimental paradigm into a more rational, prediction-driven endeavor.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as one of the most widely used computational quantum mechanical methods in physics, chemistry, and materials science. Its popularity stems from its ability to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems while maintaining a favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy. The core premise of DFT is that all properties of a molecular system in its ground state can be determined from its electron density distribution—reducing the computational variables from three times the number of electrons to just three spatial coordinates [2] [9]. This revolutionary approach, pioneered by Walter Kohn and Pierre Hohenberg, earned Kohn the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1998 and has enabled researchers to study systems that would be prohibitively expensive with other quantum chemical methods.

However, despite its tremendous success and versatility, DFT faces fundamental challenges that limit its reliability for certain chemical systems. The theory requires approximations for the exchange-correlation functional—the component that accounts for quantum mechanical effects not captured by simple electrostatic interactions—and the quality of these approximations varies significantly across different chemical contexts [2]. This article examines DFT's performance limitations through systematic comparisons with higher-accuracy methods like coupled cluster theory, focusing on quantitative benchmark studies that reveal systematic errors in DFT predictions, particularly for transition metal complexes and chemical reactions where electron correlation effects are pronounced.

Theoretical Foundations and Systematic Limitations

The Fundamental Approximations of Practical DFT

In the Kohn-Sham formulation of DFT, the intractable many-body problem of interacting electrons is reduced to a tractable problem of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential [2]. This effective potential includes the external potential (from atomic nuclei), the Coulomb interaction between electrons, and the exchange-correlation potential, which encompasses all non-classical electron interactions. The exact form of this exchange-correlation functional remains unknown, requiring approximations that introduce varying degrees of error:

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): Uses the exchange-correlation energy of a uniform electron gas, functioning well for solids but overbinding molecules.

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): Incorporates the gradient of the electron density, improving molecular properties but struggling with dispersion forces.

- Hybrid Functionals: Mix in exact Hartree-Fock exchange, offering better performance for molecular systems but at increased computational cost.

- Double-Hybrid Functionals: Include both Hartree-Fock exchange and a perturbative correlation contribution, offering the highest accuracy among DFT approximations [10].

The development of new functionals has traditionally focused on improving energy predictions, but recent research highlights a concerning trend: many modern functionals produce accurate energies from flawed electron densities [9]. This represents a fundamental problem, as the electron density is the central variable in DFT, and obtaining correct energies from incorrect densities suggests a fortunate error cancellation that may not transfer reliably across the chemical space.

Density-Driven Errors and the "DFT Midlife Crisis"

A critical examination of DFT's theoretical foundations reveals that the energy error in any approximate DFT calculation can be separated into two components: a functional-driven error and a density-driven error [11]. The theory of density-corrected DFT (DC-DFT) aims to address this separation, often by using Hartree-Fock densities instead of self-consistent DFT densities—a method known as HF-DFT. This approach has been shown to reduce energetic errors in several classes of chemical problems [11].

However, this promising direction faces implementation challenges. Recent analysis indicates that proxy densities proposed in literature are often too inaccurate for practical DC-DFT applications [11]. More fundamentally, there is growing concern that DFT development is "straying from the path toward the exact functional" [9], as many modern functionals with adjustable parameters sacrifice theoretical rigor for empirical accuracy, potentially limiting transferability across diverse chemical systems.

Quantitative Benchmarks: DFT Versus Wavefunction Methods

Performance on Transition Metal Spin-State Energetics

Transition metal complexes present a particular challenge for DFT due to their complex electronic structures with closely spaced energy states. The accurate prediction of spin-state energetics is crucial for modeling catalytic mechanisms, interpreting spectroscopic data, and computational discovery of materials [10]. A recent benchmark study on the SSE17 dataset (17 transition metal complexes with reference spin-state energetics derived from experimental data) provides quantitative insights into the performance gap between DFT and coupled cluster methods:

Table 1: Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods on SSE17 Benchmark (Mean Absolute Errors in kcal mol⁻¹)

| Method Category | Specific Method | Mean Absolute Error | Maximum Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled Cluster | CCSD(T) | 1.5 | -3.5 |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | PWPB95-D3(BJ) | <3.0 | <6.0 |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | B2PLYP-D3(BJ) | <3.0 | <6.0 |

| Standard Hybrid DFT | B3LYP*-D3(BJ) | 5-7 | >10.0 |

| Standard Hybrid DFT | TPSSh-D3(BJ) | 5-7 | >10.0 |

| Multireference Methods | CASPT2 | >1.5 | Not reported |

| Multireference Methods | MRCI+Q | >1.5 | Not reported |

The data reveals CCSD(T) as the most accurate method, outperforming all tested multireference approaches and DFT functionals [10]. Double-hybrid DFT functionals show the best performance among DFT approximations, but still exhibit significantly larger errors compared to CCSD(T). Standard hybrid functionals like B3LYP* and TPSSh, which are often recommended for spin-state energetics, demonstrate substantially worse performance with mean absolute errors of 5-7 kcal mol⁻¹ and maximum errors exceeding 10 kcal mol⁻¹ [10].

Reaction Energy Benchmarks

The performance of DFT for chemical reaction energies varies significantly depending on the functional and chemical system. A benchmark study of the reaction between ferrocenium and trimethylphosphine provides specific insights into functional performance for organometallic reactions:

Table 2: DFT Functional Performance for Ferrocenium Reaction (in Order of Decreasing Accuracy)

| DFT Functional | Relative Accuracy |

|---|---|

| M06-L | Highest |

| TPSS | ↓ |

| M06 | ↓ |

| BLYP | ↓ |

| PBE | ↓ |

| PBE0 | ↓ |

| B3LYP | ↓ |

| PWPB95 | ↓ |

| DSD-BLYP | Lowest |

The study found that empirical dispersion corrections (such as Grimme's D3) are essential for all functionals except M06 and M06-L [12]. The accuracy ranking reveals that the performance of DFT functionals is highly system-dependent, with no single functional dominating across all chemical domains.

The Gold Standard: CCSD(T) and Its Theoretical Foundations

Why CCSD(T) Works

The coupled cluster method with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) has earned its reputation as the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry due to its systematic approach to capturing electron correlation effects. The theoretical foundation of CCSD(T)'s success stems from its balanced treatment of excitation effects [13]. Unlike simpler approximations that tend to overestimate triple excitation effects, CCSD(T) includes a second term containing contributions from fifth and higher-order terms in the perturbation expansion. This additional term is nearly always positive, counterbalancing the characteristic overestimation found in methods like CCSD+T(CCSD) [13].

The non-iterative treatment of triple excitations in CCSD(T) maintains computational feasibility while delivering accuracy comparable to the much more expensive full CCSDT approach. This balance between accuracy and computational cost has made CCSD(T) the method of choice for benchmark calculations where chemical accuracy (∼1 kcal/mol) is required.

Practical Performance in Benchmark Studies

In the SSE17 benchmark, CCSD(T) demonstrated remarkable accuracy with a mean absolute error of 1.5 kcal mol⁻¹ and a maximum error of -3.5 kcal mol⁻¹ across 17 diverse transition metal complexes [10]. This performance consistently outperformed all tested multireference methods, including CASPT2, MRCI+Q, CASPT2/CC, and CASPT2+δMRCI. Interestingly, the study found that switching from Hartree-Fock to Kohn-Sham orbitals did not consistently improve CCSD(T) accuracy [10], suggesting that the method's robustness stems from its wavefunction-based treatment of correlation rather than the quality of the reference orbitals.

For the ferrocenium-phosphine reaction benchmark, DLPNO-CCSD(T) (a local approximation that reduces computational cost) served as the reference method for evaluating DFT performance [12]. The study confirmed that the systems exhibited no significant multireference character, making them well-suited for single-reference methods like CCSD(T).

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflows for Quantum Chemical Methods

The accurate assessment of quantum chemical methods requires carefully designed benchmarking protocols. The SSE17 study employed experimental reference data derived from two primary sources: spin-crossover enthalpies and energies of spin-forbidden absorption bands [10]. These experimental values were appropriately corrected for vibrational and environmental effects to isolate the electronic contributions to spin-state energetics. The benchmarking workflow can be summarized as follows:

Computational Benchmarking Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Computational Methods and Their Applications

| Method/Software | Category | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Wavefunction Theory | High-accuracy reference calculations | Gold standard for single-reference systems |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | Wavefunction Theory | Large-system coupled cluster | Reduced computational cost via localization |

| CASPT2 | Multireference Theory | Systems with strong static correlation | Handles multireference character |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | Density Functional Theory | Accurate DFT calculations | Includes HF exchange and perturbative correlation |

| SMD Model | Solvation Method | Implicit solvation in DFT | Accounts for solvent effects |

| D3 Dispersion | Empirical Correction | London dispersion in DFT | Adds missing dispersion interactions |

Density Functional Theory remains an indispensable tool in computational chemistry, physics, and materials science—the popular workhorse for routine calculations on medium to large systems where coupled cluster methods remain computationally prohibitive. Its favorable scaling with system size (typically N³ compared to N⁷ for CCSD(T)) ensures its continued relevance for practical applications.

However, the benchmark data clearly reveals DFT's systemic limitations. For transition metal spin-state energetics, even the best-performing double-hybrid functionals show errors approximately double those of CCSD(T), while commonly used hybrid functionals perform significantly worse [10]. For chemical reactions, DFT functional performance shows strong system dependence, with accuracy varying unpredictably across different chemical domains [12].

These limitations necessitate a careful, context-dependent approach to computational chemistry. For systems where high accuracy is critical—such as reaction barrier predictions, spin-state ordering in transition metal catalysts, or non-covalent interactions—CCSD(T) remains the benchmark method when computationally feasible. For larger systems, the selection of DFT functionals should be guided by benchmark studies on chemically similar systems, with double-hybrid functionals generally providing superior accuracy when affordable.

The future of computational chemistry likely lies not in a single method dominating all others, but in the thoughtful integration of multiple approaches: leveraging DFT's efficiency for exploratory studies and larger systems, while relying on wavefunction methods like CCSD(T) for final accuracy on key chemical questions. This balanced approach, informed by systematic benchmark studies, will continue to drive computational discovery across chemical domains.

In the realm of computational chemistry, predicting molecular properties with high accuracy is paramount for advancing research in drug development, materials science, and catalysis. For decades, two dominant theoretical frameworks have existed: the highly accurate but computationally expensive coupled-cluster theories, particularly CCSD(T), often called the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry, and the more computationally efficient but sometimes less reliable density functional theory (DFT). The CCSD(T) method, which includes single and double excitations with a perturbative treatment of triple excitations, provides benchmark-quality results that can reliably predict experimental outcomes and validate more approximate methods [14]. This comparison guide examines the performance characteristics of CCSD(T) versus various DFT functionals across multiple chemical domains, providing researchers with objective data to inform their methodological selections.

Theoretical Background and Methodological Comparison

Fundamental Computational Approaches

The fundamental difference between these methods lies in their theoretical foundations. CCSD(T) is a wavefunction-based ab initio method that systematically approaches the exact solution of the Schrödinger equation for many-electron systems. Its accuracy stems from a rigorous treatment of electron correlation effects, making it particularly valuable for systems where electron interactions play a critical role. However, this accuracy comes at a significant computational cost, scaling to the seventh power with system size (O(N⁷)), which limits its application to relatively small molecules or requires sophisticated fragmentation approaches for larger systems [14].

In contrast, DFT operates on the principle that the ground-state energy of a many-electron system can be determined from its electron density rather than its wavefunction. While formally offering better computational scaling (typically O(N³)), practical DFT implementations rely on approximate exchange-correlation functionals, which vary widely in their accuracy and applicability [15]. The development of these functionals has evolved through several "rungs" of increasing complexity, from local spin density approximations (LSDA) to generalized gradient approximations (GGA), meta-GGAs, and hybrid functionals that incorporate some exact Hartree-Fock exchange.

Key Methodological Considerations for Researchers

When selecting a computational method, researchers must consider several critical factors:

Target Accuracy: CCSD(T) typically achieves "chemical accuracy" (≈1 kcal/mol error) for many properties, while DFT errors can be substantially larger and less predictable [15] [5].

System Size: CCSD(T) is generally applicable to systems with up to 20-50 atoms (depending on basis set), while DFT can handle hundreds to thousands of atoms.

Property Type: CCSD(T) provides uniformly high accuracy across diverse molecular properties, while DFT performance varies significantly across different functional classes and chemical systems [15] [16] [5].

Computational Resources: CCSD(T) calculations require substantial computational resources and time compared to DFT calculations of similar systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of CCSD(T) and DFT Approaches

| Characteristic | CCSD(T) | DFT (Hybrid Functionals) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Wavefunction theory | Density functional theory |

| Treatment of Electron Correlation | Systematic, increasingly complete | Approximate, functional-dependent |

| Typical Computational Scaling | O(N⁷) | O(N³) to O(N⁴) |

| System Size Limit (Practical) | Small to medium molecules | Small to large molecules |

| Basis Set Dependence | High | Moderate |

| Systematic Improvability | Yes (through higher excitations) | Limited (functional development) |

Comparative Performance Across Chemical Systems

Singlet-Triplet Energy Separation in Carbenes

Carbenes represent important reactive intermediates in organic synthesis and catalysis, with their electronic structure dictating reactivity patterns. The energy separation between singlet and triplet states (ΔES–T) is a critical property that differentiates their chemical behavior. A comprehensive comparative study evaluated multiple DFT functionals against CCSD(T) benchmarks for nine carbene molecules, including CH₂, CHF, CHCl, CF₂, and larger derivatives [15].

The research revealed significant variability in DFT performance, with pure functionals associated with the LYP correlation functional (particularly BLYP) showing closest agreement with CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ results. Hybrid functionals like B3LYP consistently overestimated ΔES–T values across the tested carbenes. The study also identified that basis set selection played a crucial role in achieving converged results, with correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVXZ) providing systematic convergence to the complete basis set limit [15].

Table 2: Performance of DFT Functionals for Singlet-Triplet Energy Gaps in Carbenes

| DFT Functional | Mean Absolute Error (kcal/mol) | Error Trend | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLYP | Smallest | Minimal systematic error | Best agreement with CCSD(T) |

| B3LYP | Moderate | Systematic overestimation | Most widely used functional |

| BP86 | Moderate | Varies | Pure functional |

| MPW1PW91 | Moderate | Varies | Hybrid functional performance close to B3LYP |

The experimental protocol for these comparisons involved geometric optimization at the B3LYP/cc-pVTZ level followed by single-point energy calculations using various DFT functionals and CCSD(T) with the same basis set. The CCSD(T) results served as reference values when experimental data were unavailable or questionable, demonstrating the method's role as a theoretical benchmark [15].

Transition Metal Complexes and Catalytic Properties

In organometallic chemistry and catalysis research, accurate prediction of molecular properties is essential for catalyst design. A focused study on zirconocene polymerization catalysts evaluated DFT performance against CCSD(T) for ionization potentials, redox potentials, and bond dissociation energies (BDEs) [5].

While DFT generally reproduced ionization and redox potentials with reasonable accuracy, significant deviations emerged for BDEs, with errors substantially larger than typical chemical accuracy thresholds. Crucially, CCSD(T) calculations revealed potential inaccuracies in experimental BDE values, highlighting the method's value for validating and correcting experimental measurements. This study underscores CCSD(T)'s role in providing reliable reference data for systems where experimental characterization is challenging [5].

The computational methodology employed large basis sets (cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ) with effective core potentials for zirconium, with careful attention to basis set superposition errors. The CCSD(T) calculations provided benchmark-quality predictions that questioned the accuracy of previously accepted experimental values, demonstrating how high-level theory can drive reinterpretation of chemical data [5].

Non-Covalent Interactions in Charged Systems

Non-covalent interactions (NCIs) play crucial roles in biological recognition, supramolecular chemistry, and materials science. Accurate modeling of NCIs, particularly in charged systems, remains a significant challenge for DFT. Recent research highlights systematic errors of up to tens of kcal/mol in standard dispersion-enhanced DFT methods for these systems [16].

The introduction of the (r²SCAN+MBD)@HF method, which combines the r²SCAN functional with many-body dispersion evaluated on Hartree-Fock densities, represents a significant advancement. This parameter-free approach demonstrates improved accuracy for NCIs involving charged species while maintaining robust performance for neutral systems. Nevertheless, CCSD(T) continues to serve as the reference method for developing and validating such new functionals, particularly through its application to carefully designed benchmark sets [16].

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

Extension to Excited States and Molecular Materials

While CCSD(T) excels at ground-state properties, its extension to excited states through methods like CC2, CCSD, and CC3 provides similar benchmarking capabilities for electronic excitation energies. The QUEST database represents a major effort to compile highly accurate vertical transition energies for a large number of excited states, with 1,489 reference values for molecules containing up to 16 non-hydrogen atoms [17].

This comprehensive database includes singlet, doublet, triplet, and quartet states across both valence and Rydberg transitions, with particular attention to challenging cases with double-excitation character. The reference values, deemed chemically accurate (within ±0.05 eV of the full configuration interaction estimate), enable balanced assessment of popular excited-state methodologies, including time-dependent DFT approaches [17].

Fragment-Based Approaches for Extended Systems

A significant innovation enabling CCSD(T) application to larger systems is the development of fragment-based methods. The fragment-based ab initio Monte Carlo (FrAMonC) technique allows thermodynamic simulations of amorphous molecular materials (liquids and glasses) using direct ab initio sampling with CCSD(T) quality potentials [14].

This approach focuses on individual cohesive interactions within the bulk material, employing a many-body expansion scheme that enables the use of accurate electron-structure methods for the most important cohesive features. The incorporation of coupled-cluster theory in Monte Carlo simulations promises unprecedented accuracy for predicting bulk-phase equilibrium properties at finite temperatures and pressures, including density, vaporization enthalpy, thermal expansivity, and heat capacity [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how this fragment-based approach enables CCSD(T) accuracy for extended systems:

Fragment-Based Approach for Extended Systems: This workflow demonstrates how fragmentation schemes enable CCSD(T) application to large systems by decomposing them into manageable fragments.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Standard Benchmarking Methodology

The standard protocol for benchmarking DFT functionals against CCSD(T) involves several systematic steps:

System Selection: Curate a diverse set of molecules representing the chemical space of interest, including various bonding types and electronic environments [15] [17].

Geometry Optimization: Perform structural optimization at a reliable level of theory (often B3LYP/cc-pVTZ or similar) to establish consistent molecular geometries [15].

Reference Calculations: Conduct single-point CCSD(T) calculations with correlation-consistent basis sets (preferably triple-zeta or higher quality) to establish benchmark energies [15] [5].

DFT Evaluations: Compute the same properties with various DFT functionals using identical geometries and comparable basis sets.

Error Analysis: Quantify deviations between DFT and CCSD(T) results using statistical measures (mean absolute error, root mean square error, maximum error).

Assessment: Evaluate functional performance across different chemical systems and property types to identify systematic strengths and weaknesses.

Essential Research Toolkit for High-Accuracy Calculations

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for CCSD(T) and DFT Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | CFOUR, MRCC, NWChem, ORCA | Implement CCSD(T) and DFT methods with various basis sets |

| Basis Sets | Dunning's cc-pVXZ series, Pople-style basis sets | Provide systematic description of molecular orbitals |

| Reference Databases | QUEST database, GMTKN55, S22 | Offer benchmark data for method validation [17] |

| Visualization Software | GaussView, Avogadro, VMD | Facilitate molecular structure analysis and result interpretation |

| Fragment-Based Methods | FrAMonC, FMO, MFCC | Enable CCSD(T) application to larger systems [14] |

The comprehensive comparison between CCSD(T) and DFT methodologies reveals a nuanced landscape where theoretical sophistication, computational cost, and target accuracy must be carefully balanced. CCSD(T) remains the undisputed gold standard for chemical accuracy across diverse molecular properties and systems, providing essential benchmark values for method development and validation. Its systematic improvability and well-defined hierarchy offer theoretical advantages that approximate methods cannot match.

For practical applications, particularly with larger systems, DFT offers an indispensable balance between computational cost and reasonable accuracy, though with significant functional-dependent variability. Emerging approaches like fragment-based methods and machine learning potentials promise to extend CCSD(T) quality accuracy to larger systems while maintaining computational feasibility [14]. Similarly, new DFT functionals designed for specific challenges, such as non-covalent interactions in charged systems, continue to narrow the performance gap for particular applications [16].

The optimal research strategy leverages the complementary strengths of both approaches: using CCSD(T) to establish reliable reference values and validate methodologies for specific chemical systems, while employing carefully benchmarked DFT functionals for broader exploratory studies and larger systems. This synergistic approach continues to drive advances across computational chemistry, drug discovery, and materials design.

In computational chemistry and materials science, predicting the properties and behaviors of molecules from first principles is fundamental to advancements in drug discovery and materials design. This endeavor is dominated by two primary methodological approaches: Density Functional Theory (DFT) and the coupled cluster method with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)). The choice between them almost always involves a central, inescapable trade-off: computational cost versus accuracy. CCSD(T) is often lauded as the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its high accuracy, particularly for single-reference systems, but this comes at a steep computational price that limits its application to small or medium-sized molecules [3] [18]. In contrast, DFT is vastly more computationally efficient and can be applied to systems containing thousands of atoms, but its accuracy is inherently dependent on the choice of the exchange-correlation functional, which is not systematically improvable and can be unreliable for certain critical properties [2] [19]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, focusing on their performance in practical research scenarios, to help scientists select the appropriate tool for their specific challenges.

Density Functional Theory (DFT)

DFT is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used to investigate the electronic structure of many-body systems. Its fundamental premise, derived from the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, is that the ground-state properties of a system are uniquely determined by its electron density, a function of only three spatial coordinates. This simplifies the many-electron problem to a problem of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential [2]. In practice, DFT calculations involve solving the Kohn-Sham equations, which are computationally less expensive than wavefunction-based methods like coupled cluster theory. The primary challenge in DFT is the exchange-correlation functional, which encapsulates electron-electron interactions and must be approximated. Common approximations include the Local Density Approximation (LDA) and Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), with more sophisticated hybrid functionals (e.g., PBE0, M06) mixing in exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory [2] [4]. The computational cost of DFT typically scales as O(N³), where N is proportional to the number of electrons, making it suitable for large systems, though it can become impractical for systems approaching 1,000 atoms [19].

Coupled Cluster Theory (CCSD(T))

Coupled cluster theory is a wavefunction-based method that systematically approaches the exact solution of the Schrödinger equation. The CCSD(T) method, in particular, includes all single and double excitations from a reference wavefunction (usually Hartree-Fock) and incorporates a perturbative treatment of triple excitations. This level of theory is renowned for its high accuracy in describing dynamic electron correlation, making it a benchmark for predicting reaction energies, interaction energies, and molecular properties [3] [18]. However, this accuracy comes with a much higher computational burden. The computational cost of CCSD(T) scales as O(N⁷), where N is a measure of the system size, severely limiting its application to systems with more than a few dozen atoms when using the canonical, non-local implementation [3]. To extend its reach, approximations such as the Domain-Based Local Pair Natural Orbital (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) method have been developed, which can reduce the scaling to near O(N) for large systems, making it applicable to molecules with hundreds of atoms while retaining near-chemical accuracy [12].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between computational cost and system size for these core quantum chemical methods, highlighting the "wall" that limits their application.

Comparative Performance in Benchmark Studies

Accuracy in Energetics and Molecular Properties

Quantitative benchmarks against reliable experimental data or higher-level theories are essential for evaluating the performance of computational methods. The following table summarizes key findings from several such studies, comparing the accuracy of DFT and CCSD(T) for various molecular properties.

Table 1: Benchmark Accuracy of DFT and CCSD(T) for Molecular Properties

| System / Property | Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Reference Method/Data | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Clusters (Alₙ, n=2-9): Electron Affinities & Ionization Potentials [4] | PBE0 | 0.14 eV & 0.15 eV | Experimental Data | DFT shows good but not perfect agreement. |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | 0.11 eV & 0.13 eV | Experimental Data | Higher accuracy than DFT, establishing benchmark quality. | |

| Organic Molecules: Isomerization & Torsion Profiles [3] | DFT (ωB97X) | 5.0 kcal/mol (RMSD) | CCSD(T)/CBS | Good performance but with significant errors for some cases. |

| ANI-1ccx (ML trained on CCSD(T)) | 3.2 kcal/mol (RMSD) | CCSD(T)/CBS | Approaches CCSD(T) accuracy, outperforming the underlying DFT. | |

| Ferrocenium + PMe₃ Reaction [12] | Various DFT | Varies Widely | DLPNO-CCSD(T) | Performance highly functional-dependent; dispersion corrections essential. |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | (Benchmark) | N/A | Provides reliable benchmark for reaction mechanism where DFT struggles. |

Performance for Non-Covalent Interactions

Non-covalent interactions (NCI), such as dispersion forces, are critical in biomolecular recognition and materials science. Their description requires a high-level treatment of electron correlation. CCSD(T) is generally considered the most reliable method for NCIs in small to medium-sized systems [18]. However, a recent and critical area of investigation concerns its performance for large, conjugated systems like polyaromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) dimers. Some studies have reported discrepancies between CCSD(T) and alternative high-level methods like Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) for these systems, raising questions about a potential breakdown of CCSD(T)'s perturbative triples treatment as system size increases and the HOMO-LUMO gap narrows [18]. A 2024 study using the Pariser-Parr-Pople (PPP) model to benchmark CCSD(T) against higher-order coupled cluster methods (CCSDTQ) found that CCSD(T) demonstrates no signs of systematically overestimating interaction energies for systems up to the size of a dibenzocoronene dimer [18]. This suggests that for system sizes relevant to many practical applications in drug development (though not for near-metallic systems), CCSD(T) remains robust.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of computational research, it is vital to document the protocols used in benchmark studies. Below are detailed methodologies for two types of common benchmarks.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Reaction Energies and Barriers

This protocol is based on studies like the one investigating the reaction between ferrocenium and trimethylphosphine [12].

- System Selection: Choose a chemically relevant reaction with available experimental or reliable theoretical data for validation. The reaction should probe the electronic effects of interest (e.g., redox activity, bond formation/cleavage).

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometries of all reactants, products, and transition states. This can be performed using a robust DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP or PBE0) with a medium-sized basis set (e.g., 6-31G*).

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: Perform high-level single-point energy calculations on the optimized geometries using:

- Target Method: DLPNO-CCSD(T) with a large basis set (e.g., aug-cc-pVTZ) and tight SCF/PNO settings.

- Comparison Methods: A range of DFT functionals (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0, M06, TPSS) with the same large basis set.

- Error Correction:

- Apply counterpoise correction to account for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) in interaction energy calculations.

- Include empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., D3) for all DFT calculations.

- Use continuum solvation models (e.g., SMD) if the reaction occurs in solution.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the reaction energy and barrier height for each method. Compute the mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the DFT functionals relative to the DLPNO-CCSD(T) benchmark.

Protocol 2: Assessing Performance for Non-Covalent Interactions

This protocol is informed by studies that assess the accuracy of methods for dispersion-bound complexes [3] [18].

- Dimer Construction: Select a series of non-covalently bound complexes (e.g., benzene dimer, nucleic acid base pairs, or larger PAH dimers like coronene). Generate multiple representative geometries (e.g., stacked, T-shaped, parallel-displaced).

- Benchmark Interaction Energy: For each geometry, calculate the benchmark interaction energy (( \Delta E_{int} )) as the difference between the dimer energy and the sum of the monomer energies, all computed at the CCSD(T)/CBS (Complete Basis Set) limit. This often involves extrapolation from calculations with a series of correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVDZ, aug-cc-pVTZ).

- Test Method Calculations: Compute the interaction energy using:

- Various DFT functionals, with and without dispersion corrections.

- Lower-cost wavefunction methods (e.g., MP2).

- Local CCSD(T) approximations (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)).

- Error Calculation: For each test method and complex, determine the error relative to the CCSD(T)/CBS benchmark (( \Delta E{test} - \Delta E{CCSD(T)/CBS} )). Report statistical measures like MAE and RMSD across the set of complexes.

- System Size Analysis: Systematically increase the size of the monomers (e.g., from benzene to coronene to circumcoronene) to investigate the scaling of method accuracy with system size and decreasing HOMO-LUMO gap [18].

The workflow for a comprehensive benchmark study, integrating both protocol types, is visualized below.

When conducting research in this field, a suite of computational "reagents" and resources is required. The following table details key software, methodologies, and data types that form the essential toolkit.

Table 2: Key Resources for Computational Quantum Chemistry Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to CCSD(T) vs. DFT Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) [12] | Computational Method | Approximates canonical CCSD(T) energies with near-chemical accuracy and reduced cost. | Enables benchmarking on larger molecules (100s of atoms) that are intractable for canonical CCSD(T). |

| Composite Methods (e.g., CBS-QB3) | Computational Method | Achieves high accuracy by combining calculations with different methods and basis sets. | Provides an alternative route to high-accuracy energetics without a single CCSD(T)/CBS calculation. |

| Empirical Dispersion Corrections (e.g., D3) [12] | Computational Add-on | Adds dispersion interactions to DFT, which are often poorly described by standard functionals. | Essential for obtaining qualitatively correct results with DFT for non-covalent interactions and reaction energies. |

| ANI-1ccx Potential [3] | Machine Learning Potential | A neural network potential trained to achieve CCSD(T)-level accuracy. | Allows for molecular dynamics simulations and energy evaluations at CCSD(T) quality for billions of times less computational cost. |

| Complete Basis Set (CBS) Extrapolation | Computational Technique | Estimates the energy at an infinite basis set limit from a series of finite basis set calculations. | Critical for obtaining results free from basis set error, which is necessary for definitive benchmarks. |

| Active Space Selection (for MR Methods) | Computational Protocol | Defines the orbital space for multi-reference calculations (e.g., CASSCF, NEVPT2). | Required for systems with strong static correlation where both DFT and CCSD(T) may fail. |

The fundamental trade-off between computational cost and accuracy in quantum methods is a defining feature of computational chemistry. DFT remains the workhorse for high-throughput screening, large systems (proteins, materials surfaces), and molecular dynamics simulations due to its favorable O(N³) scaling. However, its accuracy is variable and functional-dependent. CCSD(T) is the benchmark for highest achievable accuracy in systems of tractable size, providing reliable data for reaction thermochemistry, spectroscopy, and non-covalent interactions, but its O(N⁷) scaling is a severe limitation.

The future of the field lies in breaking this traditional trade-off through emerging methodologies. Machine-learning potentials like ANI-1ccx demonstrate that it is possible to achieve coupled-cluster accuracy at a fraction of the cost, opening the door to high-accuracy molecular dynamics on complex systems [3]. Furthermore, the development of advanced local correlation methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T) is steadily pushing the system size limit for which near-CCSD(T) accuracy is feasible [12]. As quantum computing hardware matures, it may also provide a new paradigm for solving electronic structure problems, particularly for strongly correlated systems that challenge both DFT and CCSD(T) [20] [21]. For now, the informed researcher must continue to weigh the demands of their specific problem—system size, property of interest, and required accuracy—against the computational cost of the available methods.

Accurately predicting key electronic properties is fundamental to advancements in drug design, materials science, and catalysis. For decades, computational chemists have relied on two primary theoretical frameworks: the highly accurate but computationally expensive coupled cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T) (coupled cluster with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations), and the more efficient but sometimes less reliable Density Functional Theory (DFT). The choice between these methods represents a critical trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy for properties such as excitation gaps, which determine a molecule's optical behavior and reactivity, and polarizability, which governs its response to electric fields and intermolecular interactions. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of their performance, empowering researchers to select the optimal method for their specific investigative needs.

CCSD(T) is often termed the "gold standard of quantum chemistry" for its proven ability to deliver results as trustworthy as experiments for many molecular systems [1]. However, its severe computational scaling has traditionally restricted its application to small molecules. Conversely, DFT offers dramatically lower computational cost, enabling the study of larger, more chemically relevant systems, but its accuracy is heavily dependent on the chosen functional and can be unreliable for properties demanding precise electron correlation treatment. Recent innovations, including machine-learning accelerated CCSD(T) and advanced diagnostic tools, are reshaping this landscape, making high-fidelity calculations more accessible than ever before [1] [22].

Performance Comparison: CCSD(T) vs. DFT for Core Electronic Properties

Direct, quantitative comparisons reveal significant differences in the ability of CCSD(T) and DFT to predict essential electronic properties. The following tables synthesize experimental data from benchmark studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Method Performance for Excitation Gaps and Reaction Barriers

| Property / System | CCSD(T) Result | DFT Result (Functional) | Experimental Data | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Gap Prediction [1] | Closely matches experimental results | Varies significantly; often less accurate | Reference value | CCSD(T) provides chemical accuracy; DFT performance is functional-dependent |

| Reaction Barrier Heights (Organic Molecules) [22] | Gold standard reference | Error > 0.1 eV common (Various) | N/A | Training machine learning potentials on CCSD(T) data improves force accuracy by >0.1 eV/Å |

| Si–O–C–H Enthalpy of Formation [23] | ~1-2 kJ/mol error | M06-2X: Lowest MAE; others vary widely | Reference value | CCSD(T) sets the benchmark; M06-2X is the best-performing functional for this property |

Table 2: Comparison of Method Performance for Polarizability and Other Properties

| Property / System | Computational Method | Key Advantage | Limitation / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excited-State Polarizabilities [24] | TD-DFT with ITA | Good correlation with density-based descriptors | Accuracy is system-dependent; can struggle with charge-transfer states |

| Multi-Property Evaluation (Polarizability, Dipole Moment) [1] | MEHnet (CCSD(T)-trained) | Single model evaluates multiple properties | Outperforms DFT counterparts; generalizes to larger molecules |

| Infrared Absorption Spectra [1] | MEHnet (CCSD(T)-trained) | Predicts vibrational spectra | Closely matches experimental literature data |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

A critical understanding of the data in Section 2 requires insight into the rigorous experimental protocols used to generate it.

High-Accuracy Protocol for Si–O–C–H Systems

A 2025 benchmark study established a rigorous methodology for evaluating silicon-containing compounds, highly relevant to semiconductor and materials research [23].

- Geometry Optimization & Frequencies: Structures and vibrational frequencies were initially calculated at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level.

- Energy Extrapolation: Total energies were extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) limit using calculations with triple, quadruple, and pentuple-zeta basis sets.

- Core-Valence Correlation: Core-electron correlation effects were included via separate calculations with the cc-pwCVXZ basis set series.

- Relativistic Corrections: Scalar relativistic corrections were added using second-order Douglas-Kroll-Hess Hamiltonian calculations.

- DFT Comparison: The resulting benchmark values were used to evaluate the performance of nine common DFT functionals (e.g., M06-2X, SCAN, B3LYP) for enthalpies of formation, reaction energies, and vibrational frequencies.

Machine Learning Workflow for CCSD(T)-Level Properties

MIT researchers developed a novel protocol to achieve CCSD(T)-level accuracy at a fraction of the cost [1].

- Training Data Generation: Standard CCSD(T) calculations are performed on conventional computers for a set of small molecules.

- Neural Network Training: Results train a specialized E(3)-equivariant graph neural network (MEHnet), where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds.

- Physics-Informed Learning: The model incorporates fundamental physics principles from quantum mechanics directly into its architecture.

- Property Prediction: The trained network can predict a wide range of properties—including total energy, dipole moments, polarizability, and excitation gaps—for molecules much larger than those in the training set, maintaining high accuracy.

Figure 1: Workflow for machine learning acceleration of CCSD(T) calculations.

Protocol for Excited-State Polarizability

A combined DFT and Information-Theoretic Approach (ITA) study focused on the challenging task of calculating excited-state polarizabilities [24].

- State Calculation: Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations, using functionals like CAM-B3LYP, are performed to obtain both ground-state (S₀) and the first excited-state (S₁) electron densities.

- ITA Quantity Calculation: Information-theoretic quantities (e.g., Shannon entropy, Fisher information, Rényi entropy) are computed using the S₀, S₁, or transition densities as input.

- Linear Regression: These ITA quantities are then used in linear regression models to predict the S₁ polarizabilities, offering a potentially efficient path to a property that is difficult to measure or compute with high-level methods.

Diagnostic Tools for Computational Quality Control

For practicing computational chemists, diagnosing the reliability of a calculation is as important as the result itself. Several diagnostics have been developed, particularly for CCSD(T).

Table 3: Key Diagnostics for CCSD(T) Calculation Reliability

| Diagnostic Name | What It Measures | Interpretation Guide | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| T₁ Diagnostic | Norm of single excitation amplitudes | > 0.02 suggests potential multi-reference character & reduced CCSD(T) reliability | [25] |

| D₁ Diagnostic | Matrix 2-norm of T₁ amplitudes | Resists "dilution" in large molecules; better for systems with reaction centers in large structures | [25] |

| Density Matrix Asymmetry | Non-Hermitian character of 1-particle reduced density matrix | Larger values indicate the wavefunction is farther from exact (FCI) limit; indicates "how well the method works" | [26] |

| %TAE[(T)] | Percentage of correlation energy from (T) correction | Very high or very low values can indicate breakdown of error cancellation in CCSD(T) | [25] |

| ΔIₙ₍ₜ₎ & rᵢ[(T)] | Change in static correlation diagnostic between CCSD and CCSD(T) | Small ΔI suggests converged density; large ΔI suggests remaining static correlation | [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful computational research relies on a suite of software, hardware, and theoretical "reagents."

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T)-Level Dataset | Provides gold-standard data for training machine learning potentials or benchmarking. | UCCSD(T) dataset of 3119 organic molecule configurations for reactive chemistry [22]. |

| E(3)-Equivariant Graph Neural Network | Machine learning architecture that respects physical symmetries (rotation, translation). | MEHnet for multi-property prediction at CCSD(T) accuracy [1]. |

| Information-Theoretic Approach (ITA) | Uses electron density-derived functions to predict properties like polarizability. | Predicting excited-state (S₁) polarizabilities from S₀ densities [24]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power for CCSD(T) calculations and neural network training. | Running calculations on the MIT SuperCloud and National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center [1]. |

| Diagnostic Scripts (T₁, D₁, etc.) | Automates the analysis of calculation reliability and detects problematic systems. | Assessing multi-reference character in a transition metal complex before trusting CCSD(T) results [25]. |

The comparative analysis between CCSD(T) and DFT reveals a nuanced landscape. CCSD(T) remains the unequivocal champion for achieving the highest possible accuracy for excitation gaps, polarizabilities, and reaction barriers, particularly for small- to medium-sized molecules. Its primary limitation, extreme computational cost, is being actively addressed by innovative machine-learning approaches that distill its accuracy into scalable models [1] [22]. DFT, in contrast, offers unparalleled efficiency and is indispensable for studying very large systems, but its performance is inconsistent and functional-dependent, necessitating careful benchmarking and validation against reliable data, especially for challenging electronic structures.

The future of electronic structure calculation lies not in a single method dominating, but in a synergistic multi-method workflow. The emerging paradigm involves using DFT for initial exploration and geometry optimization of large systems, leveraging machine-learning potentials trained on CCSD(T) data for high-throughput screening and molecular dynamics, and applying canonical CCSD(T) calculations for final validation and benchmarking of the most critical candidates. As machine learning architectures continue to evolve and computational power grows, the boundary of what constitutes a "computationally feasible" system for CCSD(T)-level accuracy will continue to expand, enabling more reliable and predictive computational design across chemistry, biology, and materials science [1].

Practical Applications and Cutting-Edge Methodological Advances

In computational chemistry, the pursuit of chemical accuracy—typically defined as being within 1 kcal/mol of experimental reference values—represents a fundamental challenge for predictive science. For decades, two predominant methodologies have dominated this landscape: the highly accurate but computationally expensive coupled cluster theory, particularly CCSD(T), and the more efficient but sometimes inconsistent density functional theory (DFT). The CCSD(T) method (coupled-cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations) is widely regarded as the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its systematic approach to capturing electron correlation effects [27]. In contrast, DFT provides a more computationally efficient pathway for studying larger systems but faces challenges in achieving consistent, reliable accuracy across diverse chemical spaces [28]. This comparison guide examines the respective domains where each method excels, supported by experimental data and methodological insights to inform researchers in selecting appropriate tools for their specific applications in drug development and materials science.

The CCSD(T) Framework

The CCSD(T) method represents a sophisticated wavefunction-based approach that systematically accounts for electron correlation through a hierarchical treatment of electron excitations. The method iteratively solves for single and double excitation amplitudes before incorporating triple excitations via perturbation theory, achieving an excellent balance between accuracy and computational feasibility for systems tractable with this approach [27]. This rigorous mathematical foundation enables CCSD(T) to provide controlled accuracy with well-defined convergence properties, making it particularly valuable for benchmarking and parameterizing less complete models, including DFT functionals and machine learning potentials [27].

Recent algorithmic advances have significantly enhanced the applicability of CCSD(T). Cost-reducing approaches such as frozen natural orbitals (FNO) and natural auxiliary functions (NAF) can reduce computational expenses by up to an order of magnitude while maintaining accuracy within 1 kJ/mol of canonical CCSD(T) results [27]. These developments have extended the reach of FNO-CCSD(T) to systems containing 50-75 atoms with triple- and quadruple-ζ basis sets, considerably expanding the chemical space accessible to gold-standard computations [27].

The DFT Framework

Density functional theory operates on the fundamental principle that the ground-state energy of a many-electron system can be uniquely determined by its electron density, dramatically reducing the computational complexity compared to wavefunction-based methods that depend on 3N spatial coordinates for N electrons [2]. The Kohn-Sham approach, which forms the basis for most modern DFT calculations, replaces the interacting system of electrons with an auxiliary system of non-interacting particles moving in an effective potential, with the challenge shifted to approximating the exchange-correlation functional [2].

The versatility of DFT has made it enormously popular across physics, chemistry, and materials science, though its practical accuracy depends critically on the chosen exchange-correlation functional. Different functionals exhibit varying performance across chemical domains, with systematic limitations observed in treating dispersion interactions, charge transfer excitations, transition states, and strongly correlated systems [2]. The development of new functionals designed to overcome these deficiencies remains an active research area, though approaches incorporating adjustable parameters raise theoretical concerns by straying from the search for the exact functional [2].

Quantitative Accuracy Comparison: Benchmark Data

The performance divergence between CCSD(T) and DFT becomes evident when examining benchmark data across key chemical properties. The following tables summarize comparative results from systematic studies, highlighting the consistent accuracy of CCSD(T) against the variable performance of DFT functionals.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Glycine Conformational Properties [29]

| Method | Property | Value (Form A) | Value (Form B) | Deviation from CCSD(T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | ΔE (kJ/mol) | 0.0 | 1.9 | Reference |

| CAM-B3LYP | ΔE (kJ/mol) | 0.0 | ~2.0 | < 0.1 |

| B3LYP | ΔE (kJ/mol) | 0.0 | ~1.5 | ~0.4 |

| CCSD(T) | μ (D) | 1.11 | 4.82 | Reference |

| CAM-B3LYP | μ (D) | 1.12 | 4.76 | 0.01-0.06 |

| B3LYP | μ (D) | 1.08 | 4.64 | 0.03-0.18 |

Table 2: Dataset Availability for Method Benchmarking

| Dataset | Content | System Size | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSR-ACC/TAE25 [30] | 76,879 TAEs | Elements up to Ar | Broad chemical space coverage |

| A24 [31] | 24 small complexes | CCSD(T)/CBS + corrections | Noncovalent interactions |

| S66 [31] | 66 complexes | Balanced interaction types | Biomolecular structures |

| L7 [31] | 7 large complexes | 48-112 atoms | Large system benchmarks |

Table 3: Performance for Electric Properties (OVOS-CCSD(T) vs Full CCSD(T)) [32]

| Molecule | Property | Full CCSD(T) | OVOS-CCSD(T) | Basis Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | Dipole Moment (D) | 0.115 | 0.115 | aug-cc-pVQZ |

| Formaldehyde | Polarizability (a.u.) | 23.22 | 23.22 | aug-cc-pVQZ |

| Thiophene | Dipole Moment (D) | 0.587 | 0.587 | aug-cc-pVDZ |

| F⁻ Anion | Polarizability (a.u.) | 13.27 | 13.27 | d-aug-cc-pV5Z |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

High-Accuracy Thermochemical Protocol

The Microsoft Research Accurate Chemistry Collection (MSR-ACC) exemplifies rigorous benchmarking protocols with its TAE25 dataset of 76,879 total atomization energies obtained at the CCSD(T)/CBS level via the W1-F12 thermochemical protocol [30]. This approach employs coupled cluster theory with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations extrapolated to the complete basis set limit, delivering sub-chemical accuracy (within ±1 kcal/mol of reference data) across a broadly sampled chemical space. The dataset was constructed to exhaustively cover chemical space for all elements up to argon by enumerating and sampling chemical graphs, deliberately avoiding bias toward any particular subspace such as drug-like, organic, or experimentally observed molecules [30]. This unbiased sampling enables data-driven approaches for developing predictive computational chemistry methods with unprecedented accuracy and scope.

Electric Property Evaluation Methodology

The assessment of electronic (hyper)polarizabilities follows a systematic protocol comparing high-level correlated ab initio methods with traditional and long-range corrected DFT approaches [29]. For glycine conformers, researchers typically optimize molecular structures using DFT methods with polarized and diffuse basis sets (e.g., B3LYP/6-311++G), confirming true minima through vibrational frequency analysis. Electric properties including dipole moment (μ), static electronic dipole polarizability (α), first- (β) and second-order hyperpolarizability (γ) are then computed using progressively higher levels of theory: HF → MPn → CCSD(T) → DFT with various functionals [29]. This tiered approach allows for systematic benchmarking of less complete methods against CCSD(T) reference data, revealing functional-specific performance patterns for electric response properties.

Cost-Reduced CCSD(T) Implementation

Modern implementations of CCSD(T) employ sophisticated algorithms to extend its applicability while maintaining accuracy. The combination of frozen natural orbital (FNO) and natural auxiliary function (NAF) approaches with integral-direct density-fitting algorithms, checkpointing, and hand-optimized memory management has enabled accelerated computations with minimal accuracy sacrifice [27]. These implementations typically employ conservative FNO and NAF truncation thresholds benchmarked for challenging reaction, atomization, and ionization energies of both closed- and open-shell species, maintaining 1 kJ/mol accuracy against canonical CCSD(T) even for systems of 31-43 atoms with large basis sets [27]. The resulting computational savings of up to an order of magnitude dramatically expand the practical application domain for gold-standard quantum chemical calculations.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Computational Resources for High-Accuracy Chemistry

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MSR-ACC/TAE25 [30] | Dataset | 76,879 CCSD(T)/CBS atomization energies for broad chemical space |

| BEGDB [31] | Database | Benchmark Energy & Geometry Database for method validation |

| S66 Dataset [31] | Benchmark Set | Interaction energies for 66 noncovalent complexes relevant to biomolecules |

| FNO-CCSD(T) [27] | Method | Cost-reduced CCSD(T) via frozen natural orbitals |

| OVOS Technique [32] | Method | Optimized virtual orbital space for accelerated property calculations |

| CAM-B3LYP/ωB97X-D [29] | DFT Functional | Long-range corrected functionals for improved response properties |

Decision Framework: Method Selection Guidelines

The choice between CCSD(T) and DFT methodologies involves careful consideration of multiple factors including target accuracy, system size, property type, and computational resources. The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting between these methods in traditional computational chemistry applications:

Computational Method Selection Workflow

This decision pathway highlights several key considerations:

CCSD(T) excels when sub-chemical accuracy (±1 kcal/mol) is required for systems tractable with current computational resources (typically up to 75 atoms using FNO methods) [27]. Its systematic improvability and controlled accuracy make it indispensable for benchmarking and parameterizing other methods [30].

DFT provides a practical alternative for larger systems or high-throughput screening where moderate errors (1-3 kcal/mol) are acceptable, though functional performance must be validated for specific chemical systems [28].

Composite approaches leverage CCSD(T) for benchmarking key systems while employing validated DFT methods for broader exploration, creating a balanced strategy for comprehensive chemical investigation [31].

The comparative analysis of CCSD(T) and DFT reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological selection must align with specific research objectives. CCSD(T) maintains its position as the gold standard for achieving high accuracy across diverse chemical domains, particularly for thermochemical properties, noncovalent interactions, and electric response properties where its systematic convergence provides reliable reference data [30] [29]. Recent algorithmic advances have substantially expanded its applicability to medium-sized systems of 50-75 atoms through cost-reduced implementations [27]. DFT remains indispensable for studying larger systems and high-throughput screening, though its performance varies significantly across chemical space and functional choice [28]. Strategic computational chemistry workflows increasingly leverage the strengths of both approaches, utilizing CCSD(T) for benchmark-quality reference data and method validation while employing carefully validated DFT functionals for broader exploration [31]. This integrated approach enables researchers to balance accuracy and computational efficiency while advancing predictive capabilities in drug development and materials design.

Computational modeling stands as a cornerstone of modern chemical and pharmaceutical research, enabling scientists to predict molecular behavior, reaction pathways, and material properties before laboratory synthesis. For decades, the quantum chemistry landscape has been divided between two approaches: highly accurate but computationally prohibitive coupled-cluster methods, particularly CCSD(T) (coupled cluster with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations), and efficient but sometimes unreliable density functional theory (DFT). CCSD(T) is widely regarded as the "gold standard" of computational chemistry, capable of achieving chemical accuracy of approximately 1 kcal/mol, yet its formidable O(N⁷) scaling restricts routine application to systems of only a few dozen atoms [33] [3]. In contrast, DFT offers broader applicability but suffers from transferability issues and limitations in capturing delicate electronic effects like van der Waals interactions [33] [34].

The emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) has inaugurated a revolutionary synthesis of these approaches. By training neural networks on high-quality quantum chemical data, researchers have created models that approach CCSD(T) accuracy while maintaining the computational efficiency of classical force fields [33] [3]. This comparison guide examines the current landscape of ML-accelerated quantum chemistry, focusing on the MEHnet architecture and alternative approaches, providing researchers with objective performance data and methodological insights to inform their computational strategies.

Key Methodological Frameworks

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Approaches for Quantum Chemical Accuracy

| Method | Architectural Approach | Target Accuracy | Chemical Space |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEHnet | E(3)-equivariant neural network applying learned CCSD(T)-level correction to DFT Hamiltonian [33] | CCSD(T) | Hydrocarbon molecules |

| ANI-1ccx | Transfer learning from DFT to CCSD(T)/CBS data using ensemble neural networks [3] | CCSD(T)/CBS | Organic molecules (CHNO) |