Density Functional Theory: A Quantum Leap in Predicting Molecular Properties for Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in predicting molecular properties for pharmaceutical research and development.

Density Functional Theory: A Quantum Leap in Predicting Molecular Properties for Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in predicting molecular properties for pharmaceutical research and development. It covers the foundational quantum mechanical principles of DFT, its practical applications in drug formulation design and reaction mechanism studies, and addresses current computational challenges. The content further examines innovative optimization strategies, including machine learning-augmented functionals and multiscale modeling, which significantly enhance predictive accuracy. By validating DFT's performance against experimental data and comparing it with emerging machine learning models, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive understanding of how computational advancements are accelerating data-driven, precise molecular design.

Quantum Foundations: The Core Principles of DFT for Molecular Prediction

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science, providing a powerful framework for predicting molecular properties from first principles. This quantum mechanical method has revolutionized researchers' ability to elucidate electronic structures and molecular interaction mechanisms with precision reaching approximately 0.1 kcal/mol, making it indispensable for drug development professionals seeking to understand complex biological systems [1]. Unlike wavefunction-based methods that suffer from exponential computational complexity with increasing numbers of particles, DFT offers a computationally tractable alternative that maintains quantum mechanical accuracy [2].

The theoretical foundation of DFT rests upon two pivotal achievements: the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, which establishes the fundamental principle that electron density alone determines all ground-state properties, and the Kohn-Sham equations, which provide a practical computational scheme for implementing this theory [3] [4]. These developments have transformed DFT from a theoretical curiosity into the most widely used electronic structure method across diverse fields including pharmaceutical sciences, materials research, and drug design [5] [6].

For researchers engaged in predicting molecular properties, DFT offers unprecedented insights into drug-receptor interactions, reaction mechanisms, and electronic properties of complex biological molecules. This technical guide examines the quantum mechanical foundations of DFT, focusing on the formal theoretical framework and its practical implementation for molecular property prediction in pharmaceutical and biomedical contexts.

Theoretical Foundations

The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorem represents the formal cornerstone of Density Functional Theory, establishing the theoretical basis for using electron density as the fundamental variable in quantum mechanical calculations. This theorem consists of two essential components that together provide a rigorous foundation for DFT.

The first theorem demonstrates that the external potential v_ext(r) acting on a system of interacting electrons is uniquely determined by the ground-state electron density Ï(r). Since the external potential in turn determines the Hamiltonian, all properties of the system are uniquely determined by the ground-state density [3]. This represents a significant conceptual advancement over wavefunction-based methods because the electron density depends on only three spatial coordinates, regardless of system size, whereas the wavefunction depends on 3N coordinates for an N-electron system.

The second theorem defines a universal energy functional E[Ï] that attains its minimum value at the exact ground-state density for a given external potential. The energy functional can be expressed as:

where F[Ï] is a universal functional of the density that encompasses the electron kinetic energy and electron-electron interactions [3]. The proof of this theorem, particularly through the constrained search formulation introduced by Levy, provides a constructive method for defining the density functional [3] [2].

For research scientists working in molecular property prediction, the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem provides the crucial theoretical justification for using electron density as the fundamental variable, enabling the determination of all ground-state molecular properties from this quantity alone. This principle is particularly valuable in drug design, where understanding electron density distributions facilitates predictions of reactive sites and molecular interaction patterns [1].

The Kohn-Sham Equations

While the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem establishes the theoretical possibility of calculating all ground-state properties from the electron density, it does not provide a practical computational scheme. This limitation was addressed by Kohn and Sham through the introduction of an ingenious approach that constructs a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that generates the same electron density as the real, interacting system [3] [4].

The Kohn-Sham approach partitions the universal functional F[Ï] into three computationally tractable components:

where T_s[Ï] represents the kinetic energy of the non-interacting reference system, E_H[Ï] is the classical Hartree (Coulomb) energy, and E_xc[Ï] encompasses the exchange-correlation energy that accounts for all remaining electron interaction effects [4].

The minimization of the total energy functional with respect to the electron density leads to a set of one-electron equations known as the Kohn-Sham equations:

where φ_i(r) are the Kohn-Sham orbitals and ε_i are the corresponding orbital energies. The effective potential v_eff(r) is given by:

In this formulation, v_ext(r) represents the external potential (typically electron-nuclear attraction), the second term denotes the Hartree potential, and the final term v_xc(r) is the exchange-correlation potential [4]. The electron density is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals:

These equations must be solved self-consistently because the effective potential depends on the density, which in turn depends on the Kohn-Sham orbitals [7]. This self-consistent field (SCF) procedure forms the computational backbone of Kohn-Sham DFT calculations and enables the determination of molecular properties with quantum mechanical accuracy [1].

Table 1: Components of the Kohn-Sham Energy Functional

| Energy Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Energy | `Ts[Ï] = ∑⟨φi | -½∇² | φ_i⟩` | Kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons |

| Hartree Energy | `E_H[Ï] = ½∫∫Ï(r)Ï(r')/ | r-r' | drdr'` | Classical electron-electron repulsion |

| Exchange-Correlation | E_xc[Ï] = ∫f(Ï,∇Ï,...)Ï(r)dr |

Quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects | ||

| External Potential | E_ext[Ï] = ∫v_ext(r)Ï(r)dr |

Electron-nuclear attraction |

Computational Methodology

Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The accuracy of Kohn-Sham DFT calculations critically depends on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional E_xc[Ï], as the exact form of this functional remains unknown. Several classes of functionals have been developed with varying levels of complexity and accuracy, each with specific strengths for particular applications in molecular property prediction.

The Local Density Approximation (LDA) represents the simplest approach, deriving the exchange-correlation energy from the known results for a uniform electron gas:

where ε_xc(Ï(r)) is the exchange-correlation energy per particle of a uniform electron gas with density Ï(r) [3]. While LDA performs adequately for metallic systems and provides reasonable structural parameters, it significantly overbinds molecular complexes and provides poor descriptions of hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions, limiting its utility in pharmaceutical applications [3] [1].

The Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) improves upon LDA by incorporating the density gradient as an additional variable:

This approach more accurately describes molecular properties, particularly hydrogen bonding and surface phenomena, making it widely applicable to biomolecular systems [1]. Popular GGA functionals include PBE and BLYP, which have demonstrated excellent performance for geometric parameters and reaction barriers in drug-like molecules.

Hybrid functionals incorporate a portion of exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory alongside DFT exchange and correlation. The most widely used hybrid functional, B3LYP, employs a parameterized mixture of exact exchange with GGA exchange and correlation:

where a, b, and c are empirical parameters [5]. Hybrid functionals typically provide superior accuracy for reaction barriers, molecular energies, and electronic properties, making them particularly valuable for drug design applications where precise energy differences are critical [1] [5].

Table 2: Classification of Exchange-Correlation Functionals in DFT

| Functional Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Drug Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | Local density dependence | Computational efficiency; good for metals | Poor for weak interactions; overbinding | Limited use for molecular systems |

| GGA | Adds density gradient dependence | Improved molecular properties; hydrogen bonding | Underestimates dispersion forces | Biomolecular structure optimization |

| Meta-GGA | Adds kinetic energy density dependence | Better atomization energies and bond properties | Increased computational cost | Complex molecular systems |

| Hybrid | Mixes exact Hartree-Fock exchange | Accurate barriers and energetics | High computational cost | Reaction mechanisms; molecular spectroscopy |

Basis Sets and Pseudopotentials

The practical implementation of Kohn-Sham DFT requires the expansion of molecular orbitals in terms of basis functions, typically chosen as Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) or plane waves. The selection of an appropriate basis set represents a critical compromise between computational efficiency and accuracy, particularly for large biological molecules where resource constraints are significant.

In drug discovery applications, Gaussian-type basis sets offer advantages for molecular systems due to their efficient evaluation of multi-center integrals. Popular choices include Pople-style basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) and correlation-consistent basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ), with the selection dependent on the specific molecular properties under investigation [1].

Pseudopotentials (or effective core potentials) provide a methodological approach for reducing computational cost by replacing core electrons with an effective potential, thereby focusing computational resources on valence electrons that primarily determine chemical behavior [8]. Recent advances in pseudopotential development have addressed historical accuracy limitations, with modern approaches demonstrating improved performance for semiconductor bandgaps and molecular properties [8].

For researchers investigating periodic systems or surface phenomena, plane-wave basis sets offer advantages through their inherent completeness and efficiency in evaluating Fourier transforms, particularly when combined with pseudopotentials to describe core-valence interactions.

Computational Workflow and Protocol

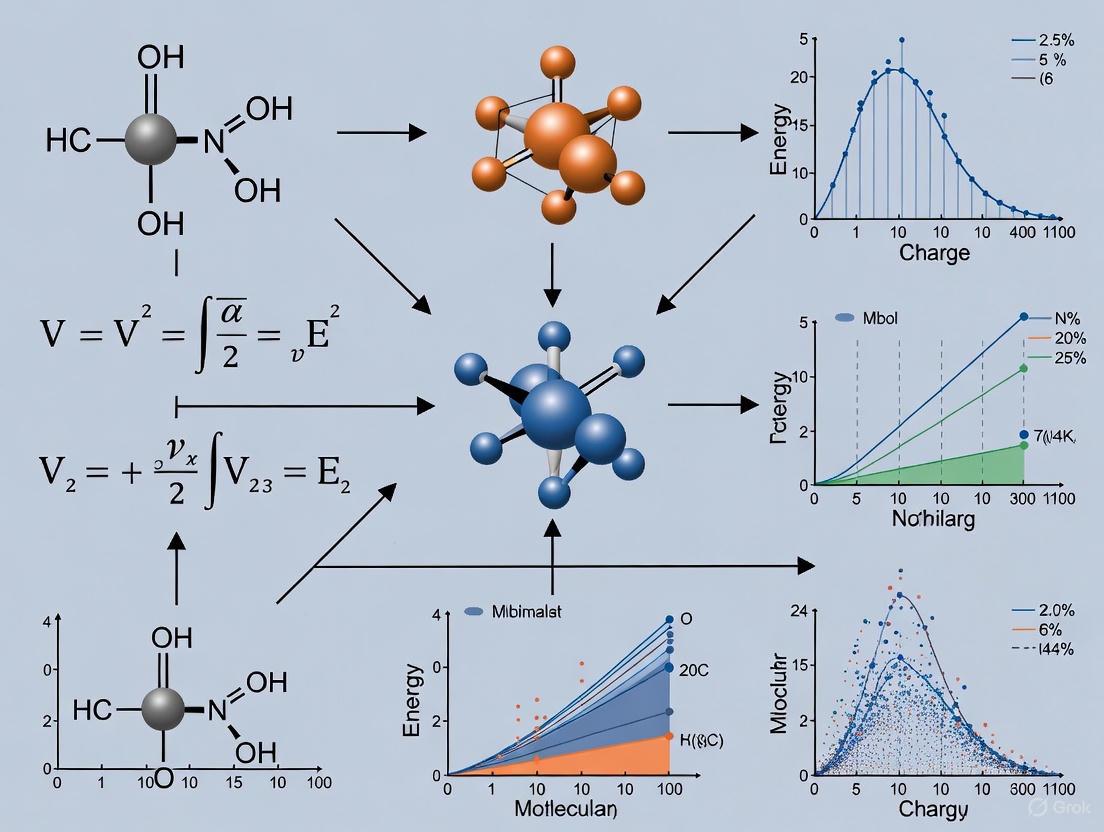

The standard computational workflow for Kohn-Sham DFT calculations follows a well-defined self-consistent field procedure that iteratively determines the electron density and effective potential until convergence criteria are satisfied. The diagram below illustrates this fundamental computational cycle:

Figure 1: SCF Computational Workflow in Kohn-Sham DFT

A detailed protocol for DFT calculations in molecular property prediction includes the following steps:

System Preparation and Initialization

- Obtain molecular geometry from experimental data or preliminary calculations

- Select appropriate exchange-correlation functional based on research objectives

- Choose basis set considering balance between accuracy and computational cost

Self-Consistent Field Calculation

- Generate initial electron density guess using superposition of atomic densities

- Construct the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian including effective potential

- Solve the Kohn-Sham equations to obtain orbitals and orbital energies

- Form new electron density from occupied Kohn-Sham orbitals

- Evaluate convergence criteria (typically density change or energy change between iterations)

- Repeat until convergence thresholds are met (usually 10â»â¶ to 10â»â¸ Hartree for energy)

Property Calculation and Analysis

- Compute molecular properties from converged density and orbitals

- Perform population analysis (Mulliken, Natural Bond Order) to understand electronic structure

- Calculate vibrational frequencies for thermodynamic properties and stationary point characterization

- Analyze molecular electrostatic potential surfaces for reactivity predictions

For drug design applications, additional specialized analyses include Fukui function calculations to identify nucleophilic and electrophilic sites, binding energy computations for drug-receptor interactions, and solvation modeling using implicit solvent models such as COSMO to simulate physiological environments [1].

Applications in Molecular Property Prediction and Drug Design

Molecular Interactions in Drug Formulation

DFT has emerged as a transformative tool in pharmaceutical formulation design, enabling researchers to elucidate the electronic driving forces governing drug-excipient interactions at unprecedented resolution. By solving the Kohn-Sham equations with quantum mechanical precision, DFT facilitates accurate reconstruction of molecular orbital interactions that determine stability, solubility, and release characteristics of drug formulations [1].

In solid dosage forms, DFT calculations clarify the electronic factors controlling active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)-excipient co-crystallization, enabling rational design of co-crystals with enhanced stability and bioavailability. The method employs Fukui functions and Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps to predict reactive sites and interaction patterns, providing theoretical guidance for stability-oriented formulation design [1]. For nanodelivery systems, DFT enables precise calculation of van der Waals interactions and π-π stacking energies, facilitating optimization of carrier surface charge distribution to improve targeting efficiency [1].

The combination of DFT with solvation models such as COSMO (Conductor-like Screening Model) has proven particularly valuable for simulating physiological conditions, allowing quantitative evaluation of polar environmental effects on drug release kinetics and providing critical thermodynamic parameters (e.g., ΔG) for controlled-release formulation development [1].

Drug-Receptor Interactions and Mechanism Studies

DFT provides unparalleled insights into drug-receptor interactions by modeling the electronic structure of binding sites and quantifying interaction energies with quantum mechanical accuracy. This capability enables researchers to understand the fundamental mechanisms of drug action and rationally design more effective therapeutic agents.

The methodology employs several key approaches for studying drug-receptor interactions:

Transition State Modeling: DFT replicates transition states between potential drugs and their receptors, enabling the design of mechanism-based inhibitors that mimic these transition states to decrease activation barriers and enhance drug efficacy [5]. This approach has been successfully applied to neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza treatment and protease inhibitors for HIV therapy.

Electronic Structure Analysis: Calculations of Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps and Average Local Ionization Energy (ALIE) provide critical parameters for predicting drug-target binding sites. MEP maps visualize electron-rich (nucleophilic) and electron-deficient (electrophilic) regions on molecular surfaces, while ALIE quantifies the energy required for electron removal, identifying sites most susceptible to electrophilic attack [1].

Organometallic Drug Modeling: DFT efficiently characterizes metal-containing drug systems and inorganic therapeutics, providing insights into structure-activity relationships that guide the design of metallopharmaceuticals with improved therapeutic profiles [5].

Recent applications include DFT studies of COVID-19 therapeutics, where researchers investigated amino acids as potential immunity boosters, analyzed tautomerism in viral RNA bases, and evaluated metal-containing compounds for antiviral activity [5]. These studies demonstrate DFT's capability to accelerate drug discovery during global health emergencies by providing rapid theoretical guidance for experimental validation.

Accuracy and Validation in Pharmaceutical Applications

The reliability of DFT predictions for molecular properties has been extensively validated through comparison with experimental data and high-level theoretical methods. Understanding the accuracy limitations of different functionals is essential for proper application in drug design projects.

Table 3: Accuracy Assessment of DFT (B3LYP Functional) for Molecular Properties

| Property Category | Estimated Accuracy | Recommended for Drug Design | Applications in Pharmaceutical Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomization Energies | 2.2 kcal·molâ»Â¹ | No | Limited use for absolute binding energies |

| Transition Barriers | 1 kcal·molâ»Â¹ | Yes | Reaction mechanism studies |

| Molecular Geometry | Bond angle: 0.2°Bond length: 0.005 Å | Yes | Conformational analysis, pharmacophore modeling |

| Ionization Energies & Electron Affinities | 0.2 eV | Yes | Redox properties, metabolic stability prediction |

| Metal-Ligand Bonding | 4-5 kcal·molâ»Â¹ | Yes | Metallodrug design, enzyme cofactor interactions |

| Hydrogen Bonding | 1-2 kcal·molâ»Â¹ | Yes | Supramolecular chemistry, protein-ligand interactions |

| Conformational Energies | 1 kcal·molâ»Â¹ | Yes | Polymorph prediction, receptor binding affinity |

The tabulated data demonstrates that DFT provides sufficient accuracy for many pharmaceutical applications, particularly those involving relative energies, molecular geometries, and non-covalent interactions [5]. Hybrid functionals such as B3LYP generally outperform LDA and GGA for most molecular properties, though specialized applications may benefit from more recent functional developments including double-hybrid functionals and range-separated hybrids [1] [5].

For drug development professionals, these accuracy assessments provide practical guidance for selecting computational methods appropriate to specific research questions, enabling effective integration of DFT predictions into the drug discovery pipeline.

Successful implementation of DFT calculations for molecular property prediction requires careful selection of computational tools and methodologies. The following table summarizes key resources and their functions in DFT-based drug research:

Table 4: Essential Computational Resources for DFT Studies in Drug Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange-Correlation Functionals | B3LYP, PBE0, M06-2X | Determine accuracy for specific molecular properties | Hybrid functionals for reaction mechanisms; GGA for geometry optimization |

| Basis Sets | 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ, def2-TZVP | Expand molecular orbitals; balance accuracy and cost | Polarized basis sets for organic molecules; diffuse functions for anions |

| Solvation Models | COSMO, PCM, SMD | Simulate physiological environments; estimate solvation free energies | Prediction of solubility, pKa, and partition coefficients |

| Software Packages | Q-Chem, Gaussian, VASP | Implement SCF procedure; calculate molecular properties | Q-Chem for comprehensive molecular analysis [7] |

| Analysis Methods | Fukui functions, MEP, ALIE | Predict reactive sites; map molecular recognition | Identification of nucleophilic/electrophilic centers in drug molecules |

| Multiscale Methods | ONIOM, QM/MM | Combine DFT with molecular mechanics for large systems | Enzyme active site studies; protein-ligand binding calculations |

Future Perspectives and Methodological Developments

The ongoing evolution of DFT methodology continues to expand its applications in molecular property prediction and drug design. Several promising directions represent the frontier of DFT development for pharmaceutical research.

Machine learning-enhanced DFT frameworks are emerging as transformative approaches for accelerating calculations while maintaining quantum mechanical accuracy. These methods employ machine-learned potentials to approximate kinetic energy density functionals or predict molecular properties, significantly reducing computational costs for complex systems [2] [1]. For example, the M-OFDFT approach uses deep learning models to approximate kinetic energy density functionals, improving the accuracy of binding energy calculations in aqueous environments [1].

Multiscale modeling approaches that integrate DFT with molecular mechanics (QM/MM methods) enable realistic simulations of drug-receptor interactions in biologically relevant environments. The ONIOM framework, for instance, employs DFT for high-precision calculations of drug molecule core regions while using molecular mechanics force fields to model protein environments, achieving an optimal balance between accuracy and computational feasibility [1].

Advanced functionals continue to address historical limitations of DFT, with double hybrid functionals incorporating second-order perturbation theory corrections to improve excited-state energies and reaction barriers [1]. Range-separated hybrids provide more accurate descriptions of charge-transfer processes, while self-interaction corrections address delocalization errors that affect redox potential predictions.

These methodological advances, combined with increasing computational resources and algorithmic improvements, ensure that DFT will remain an indispensable tool for molecular property prediction in drug development, enabling researchers to address increasingly complex biological questions with quantum mechanical precision.

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorem and Kohn-Sham equations together provide a rigorous quantum mechanical foundation for predicting molecular properties using electron density as the fundamental variable. This theoretical framework has evolved from a formal mathematical proof to an indispensable tool in pharmaceutical research, enabling drug development professionals to understand molecular interactions, predict reactive sites, and optimize drug properties with unprecedented accuracy.

The continued development of exchange-correlation functionals, basis sets, and computational protocols ensures that DFT remains at the forefront of molecular modeling, with applications spanning from fundamental mechanistic studies to practical formulation design. As methodological advances address current limitations and computational resources expand, DFT promises to play an increasingly central role in accelerating drug discovery and development through rational molecular design.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the computational cornerstone for predicting fundamental molecular properties, enabling advancements in drug discovery, materials science, and energy research. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three critical outputs of DFT calculations: molecular orbital energies, geometric configurations, and vibrational frequencies. We summarize key quantitative benchmarks, detail standardized computational protocols, and visualize complex workflows to equip researchers with the methodologies needed for robust and reproducible simulations. The integration of these outputs provides a comprehensive picture of molecular structure, stability, and reactivity, forming the basis for rational design across scientific disciplines.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as a foundational pillar in computational chemistry, biochemistry, and materials science. Its unique value lies in providing an extraordinarily efficient reduction in the computational cost of calculating the electron glue in an exact manner, from exponential to cubic, making it possible to perform atomistic calculations of practical value within seconds to hours [9]. The method revolves around solving for the electron density of a system to determine its ground-state energy and properties. This capability is paramount for predicting whether a chemical reaction will proceed, whether a candidate drug molecule will bind to its target protein, or if a material is suitable for carbon capture [9]. However, the accuracy of DFT is fundamentally governed by the choice of the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, an unknown term for which approximations must be designed. For decades, the limited accuracy of these functionals has been a significant barrier, but recent breakthroughs involving large-scale datasets and deep learning are poised to revolutionize the predictive power of DFT, potentially bringing errors with respect to experiments within the threshold of chemical accuracy (around 1 kcal/mol) [9]. This guide details the protocols for obtaining and validating three key outputs that are central to this revolution: molecular orbital energies, geometric configurations, and vibrational frequencies.

Molecular Orbital Energies

Molecular orbital (MO) energies are eigenvalues derived from the Kohn-Sham equations in DFT. They provide critical insight into a molecule's electronic structure, dictating its reactivity, optical properties, and charge transport behavior.

Computational Protocols and Methodologies

The accuracy of calculated MO energies, particularly the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), is highly sensitive to the computational setup.

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: The choice of XC functional is paramount. Global hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP) often provide a better balance for orbital energies compared to pure generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals. Recent machine-learned functionals, such as Skala, show promise in reaching experimental accuracy by learning the XC functional directly from highly accurate data [9].

- Basis Set: A polarized triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) is typically the minimum recommended for reliable orbital energy calculations. Diffuse functions are essential for accurately modeling anions, excited states, and non-covalent interactions.

- System Charge and Multiplicity: The molecular charge and spin multiplicity must be correctly specified to match the electronic state of the system under investigation.

- Convergence Criteria: Tight convergence criteria for the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure and the geometry optimization are necessary to ensure the calculated orbital energies are physically meaningful.

Table 1: Standard Protocol for Molecular Orbital Energy Calculations

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Notes and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| XC Functional | B3LYP, PBE0, or modern ML functionals (e.g., Skala) | Hybrid functionals mix in exact exchange; ML functionals offer a path to higher accuracy [9]. |

| Basis Set | def2-TZVP or 6-311+G(d,p) | Provides a good balance of accuracy and cost; diffuse functions are key for LUMO energies. |

| Dispersion Correction | D3(BJ) | Empirically accounts for long-range van der Waals interactions. |

| SCF Convergence | "Tight" (e.g., 10-8 Eh) | Ensures electronic energy and eigenvalues are fully converged. |

| Integration Grid | "FineGrid" or equivalent | A denser grid is critical for accurate numerical integration of the XC energy. |

Quantitative Data and Benchmarking

HOMO-LUMO gaps are a quintessential property derived from MO energies. Reproducible procedures for DFT are well-established for molecules, but complexities in materials properties like bandgaps present significant challenges. Standard protocols can lead to a ~20% occurrence of significant failures during bandgap calculations for 3D materials, highlighting the need for careful optimization of pseudopotentials, plane-wave basis-set cutoff energies, and Brillouin-zone integration grids [10].

Geometric Configurations

The geometric configuration of a molecule—the optimized positions of its nuclei—represents a local or global minimum on the potential energy surface (PES). This is a prerequisite for all subsequent property calculations.

Optimization Workflow and Convergence

Geometry optimization is an iterative process that searches for nuclear coordinates where the forces (the negative gradient of the energy) are zero.

Diagram 1: Geometry optimization and frequency validation workflow.

Advanced Techniques and Datasets

For complex systems, traditional optimization can be computationally prohibitive. The Mobile Block Hessian (MBH) method is a powerful alternative for large molecules or clusters. It treats parts of the system as rigid blocks, using the block's position and orientation as coordinates. This is ideal for partially optimized structures, such as those from a constrained geometry optimization, and prevents non-physical imaginary frequencies arising from internal block forces [11]. Furthermore, large-scale datasets like Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) are revolutionizing the field. OMol25 contains over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots with properties calculated by DFT, including configurations ten times larger (up to 350 atoms) and more chemically diverse than previous datasets. This enables the training of accurate Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) that can provide DFT-level accuracy 10,000 times faster [12] [13].

Vibrational Frequencies

Vibrational spectroscopy, primarily Infrared (IR) and Raman, is a key experimental tool for molecular identification. DFT calculates these spectra by analyzing the system's energy curvature at its optimized geometry.

Fundamental Principles and Calculation Setup

The starting point for vibrational analysis is the Hessian matrix, the second derivative of the energy with respect to atomic coordinates. The eigenvalues of the mass-weighted Hessian are the frequencies, and the eigenvectors are the normal modes [11]. The calculation of the full Hessian can be expensive, as it typically requires 6N single-point calculations if done numerically [11]. Vibrational spectra are obtained by differentiating a property (like the dipole moment for IR) along the normal modes at a local minimum on the PES; therefore, a geometry optimization must be performed first to avoid negative frequencies [11].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Vibrational Frequency Calculations

| Parameter | Setting | Purpose and Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Task | GeometryOptimization |

Ensures frequencies are calculated at a minimum-energy structure. |

| Properties | NormalModes Yes |

Triggers the calculation of frequencies and IR intensities. |

| Raman | Yes (if needed) |

Calculates Raman intensities; requires more computational effort. |

| Numerical Hessian | Automatic in most engines | Constructs the force constant matrix via finite differences of analytical gradients. |

| Line Broadening | 10-20 cm-1 (Lorentzian) | Converts discrete stick spectra into a continuous, experimentally comparable spectrum. |

Specialized Methods for Large Systems

For very large systems, calculating the full Hessian is inefficient. Several methods can be employed to obtain partial or approximate vibrational data:

- Symmetric Displacements: For symmetric molecules, the Hessian can be calculated using symmetry-adapted displacements. This allows for the calculation of only those irreps that result in non-zero IR or Raman intensities, saving significant time [11].

- Mobile Block Hessian (MBH): As mentioned for geometries, MBH is also used for frequency calculations on partially optimized structures or systems where only the low-frequency, large-amplitude motions of blocks are of interest [11].

- Mode Selective Methods: Techniques like mode scanning, mode refinement, and mode tracking can be used to calculate specific vibrational modes of interest without computing the entire spectrum, offering a fast alternative to the full numerical Hessian [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This section details the key computational "reagents" and tools required for conducting state-of-the-art DFT research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DFT Simulations

| Item / Software | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [12] [13] | Dataset | A massive repository of DFT-calculated molecular structures and properties for training and benchmarking MLIPs. |

| Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) [13] | Machine Learning Model | A foundational MLIP trained on billions of atoms, offering accurate, generalizable predictions for molecular behavior. |

| ORCA (v6.0.1) [13] | Quantum Chemistry Software | A high-performance program package used for advanced quantum chemistry calculations, including wavefunction methods and DFT. |

| AMS (with ADF, BAND engines) [11] | Modeling Suite | A comprehensive software platform for DFT calculations, offering robust modules for geometry optimization and vibrational spectroscopy. |

| Skala Functional [9] | Exchange-Correlation Functional | A machine-learned density functional that achieves high accuracy for main group molecules, competitive with the best existing functionals. |

| Pseudopotentials / PAWs | Computational Resource | Pre-defined potentials that replace core electrons, reducing computational cost while maintaining accuracy for valence properties. |

| Octaprenyl-MPDA | Octaprenyl-MPDA, MF:C40H67O4P, MW:642.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 16:0-10 Doxyl PC | 16:0-10 Doxyl PC, MF:C46H90N2O10P, MW:862.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow for Molecular Property Prediction

The individual key outputs are not isolated; they form a cohesive workflow for comprehensive molecular analysis. The following diagram illustrates how these components integrate, from initial structure to final prediction, and how new data-driven approaches are enhancing this pipeline.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow from DFT calculation to property prediction.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone of modern computational quantum chemistry, offering a practical balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for predicting molecular properties. Its success hinges on two critical approximations: the exchange-correlation functional and the basis set. The functional encapsulates complex quantum many-body effects, while the basis set provides the mathematical functions to represent molecular orbitals. Within the context of molecular properties research, particularly for drug development, these choices directly determine the reliability of predictions for drug-target interactions, solubility, and toxicity. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of how these selections impact computational outcomes, equipping researchers with the knowledge to make informed decisions in their computational workflows.

Theoretical Foundations of DFT

DFT simplifies the complex many-electron problem by using electron density, rather than the wavefunction, as the fundamental variable. The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish that the ground-state energy of a system is a unique functional of its electron density ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) [14]. The Kohn-Sham framework implements this theory by introducing a system of non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the true interacting system. The total energy is expressed as:

[ E[\rho] = Ts[\rho] + V{\text{ext}}[\rho] + J[\rho] + E_{\text{xc}}[\rho] ]

where ( Ts[\rho] ) is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, ( V{\text{ext}}[\rho] ) is the external potential energy, ( J[\rho] ) is the classical Coulomb repulsion, and ( E_{\text{xc}}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation energy [14]. This last term contains all the intricate quantum many-body effects and must be approximated, as its exact form remains unknown. The pursuit of better functionals represents a central challenge in DFT development.

The Hierarchy of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

The accuracy of DFT calculations is primarily governed by the choice of the exchange-correlation functional. These functionals are systematically improved by incorporating more physical information and parameters, often described as climbing "Jacob's Ladder" towards chemical accuracy [14].

Functional Types and Characteristics

Local Density Approximation (LDA) uses only the local electron density ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) at each point in space, modeled after the uniform electron gas. While simple and computationally efficient, LDA tends to overbind, predicting bond lengths that are too short and binding energies that are too large [14]. Its limitations make it generally unsuitable for molecular chemistry applications.

Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) improves upon LDA by incorporating the gradient of the electron density ( \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r}) ) to account for inhomogeneities in real systems. Popular GGA functionals include BLYP, PBE, and B97. GGAs generally provide better geometries than LDA but often show deficiencies in energetic predictions [14].

meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation (meta-GGA) introduces additional information through the kinetic energy density ( \tau(\mathbf{r}) ) or the Laplacian of the density ( \nabla^2\rho(\mathbf{r}) ). Functionals like TPSS, M06-L, and r2SCAN offer significantly improved energetics at only slightly increased computational cost compared to GGAs [15] [14]. Meta-GGAs can be more sensitive to integration grid size, potentially requiring larger grids for converged results.

Hybrid Functionals mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange. Global hybrids like B3LYP and PBE0 use a fixed ratio (e.g., 20% HF exchange in B3LYP) throughout space [14]. The inclusion of HF exchange mitigates self-interaction error and improves the description of molecular properties, particularly reaction energies and band gaps, but substantially increases computational cost due to the need to evaluate non-local exchange.

Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH) employ a distance-dependent mixing of HF and DFT exchange, typically with more HF exchange at long range. Functionals such as CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X, and ωB97M are particularly valuable for describing charge-transfer excitations, stretched bonds in transition states, and systems with non-homogeneous electron distributions [14].

Table 1: Classification of Select Density Functionals

| Type | Ingredients | Examples | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ) | SVWN | Simple, fast | Severe overbinding, poor accuracy |

| GGA | ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ), ( \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r}) ) | BLYP, PBE | Better geometries | Poor energetics |

| meta-GGA | ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ), ( \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r}) ), ( \tau(\mathbf{r}) ) | TPSS, r2SCAN | Good energetics, balanced | Grid sensitivity |

| Global Hybrid | GGA + HF exchange | B3LYP, PBE0 | Improved reaction energies | High computational cost |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | GGA + distance-dependent HF | ωB97X, CAM-B3LYP | Charge-transfer, excited states | Parameter dependence, cost |

Basis Sets in DFT Calculations

Basis sets form the mathematical foundation for expanding Kohn-Sham orbitals, and their choice profoundly impacts both the accuracy and computational cost of DFT calculations.

Basis Set Types and Quality Levels

Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs) are the standard choice in molecular quantum chemistry due to their computational efficiency in evaluating multi-center integrals [16]. The quality of a basis set is often described by its zeta (ζ) rating:

Minimal Basis Sets (e.g., STO-3G) use a single basis function per atomic orbital. While computationally inexpensive, they suffer from significant basis set incompleteness error (BSIE) and are generally insufficient for quantitative predictions [15].

Double-Zeta (DZ) Basis Sets (e.g., 6-31G*, def2-SVP) employ two basis functions per orbital, offering improved flexibility at moderate cost. However, they can still exhibit substantial BSIE and basis set superposition error (BSSE), where fragments artificially "borrow" basis functions from adjacent atoms [15].

Triple-Zeta (TZ) Basis Sets (e.g., 6-311G, def2-TZVP) provide three functions per orbital, significantly reducing BSIE and often yielding results close to the complete basis set (CBS) limit. This improvement comes at a substantial computational cost, with calculations typically taking five times longer than with double-zeta basis sets [15].

Specialized Basis Sets like the vDZP basis set developed for the ωB97X-3c composite method use effective core potentials and deeply contracted valence functions to minimize BSSE almost to the triple-zeta level while maintaining double-zeta computational cost [15]. Recent research shows vDZP can be effectively paired with various functionals like B97-D3BJ and r2SCAN to produce accurate results without method-specific reparameterization [15].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The practical performance of functional and basis set combinations can be evaluated through comprehensive benchmarking on well-established datasets like GMTKN55, which covers diverse aspects of main-group thermochemistry.

Table 2: Performance of Various Functional/Basis Set Combinations on GMTKN55 Benchmark (WTMAD2 Values) [15]

| Functional | Basis Set | Basic Properties | Isomerization | Barrier Heights | Inter-NCI | Overall WTMAD2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B97-D3BJ | def2-QZVP | 5.43 | 14.21 | 13.13 | 5.11 | 8.42 |

| vDZP | 7.70 | 13.58 | 13.25 | 7.27 | 9.56 | |

| r2SCAN-D4 | def2-QZVP | 5.23 | 8.41 | 14.27 | 6.84 | 7.45 |

| vDZP | 7.28 | 7.10 | 13.04 | 9.02 | 8.34 | |

| B3LYP-D4 | def2-QZVP | 4.39 | 10.06 | 9.07 | 5.19 | 6.42 |

| vDZP | 6.20 | 9.26 | 9.09 | 7.88 | 7.87 | |

| M06-2X | def2-QZVP | 2.61 | 6.18 | 4.97 | 4.44 | 5.68 |

| vDZP | 4.45 | 7.88 | 4.68 | 8.45 | 7.13 |

The data reveals several key trends. First, the specialized vDZP basis set generally maintains respectable accuracy compared to the much larger def2-QZVP basis, despite its significantly lower computational cost. Second, the performance gap between basis sets varies by functional; for isomerization energies, r2SCAN-D4/vDZP actually outperforms its def2-QZVP counterpart. Finally, modern meta-GGA functionals like r2SCAN and M06-2X show particularly strong performance with appropriate basis sets.

Selection Protocol for Molecular Properties Research

Choosing the optimal functional and basis set requires balancing accuracy needs with computational constraints, guided by the specific molecular properties of interest.

Workflow for Functional and Basis Set Selection

This workflow provides a systematic approach for researchers to navigate the critical choices in DFT calculations. The decision process begins with clearly defining the calculation's purpose and identifying which molecular properties are most important, as different properties have varying sensitivities to functional and basis set choices.

For functional selection, the target properties should guide the choice:

- Geometries and vibrational frequencies often perform well with GGA or meta-GGA functionals like PBE or r2SCAN [14].

- Reaction energies and barrier heights typically benefit from hybrid functionals like B3LYP or PBE0 that include exact exchange [14].

- Band gaps, charge-transfer excitations, and excited states usually require range-separated hybrids like ωB97X or CAM-B3LYP for quantitatively accurate results [14].

- Weak interactions (van der Waals complexes, π-π stacking) necessitate functionals with explicit dispersion corrections (e.g., -D3, -D4) [15] [1].

For basis set selection, computational resources and accuracy requirements must be balanced:

- Rapid screening of large molecular systems may employ minimal basis sets or double-zeta sets with effective core potentials (ECPs) [16].

- Standard accuracy for drug discovery applications can be achieved with quality double-zeta basis sets like vDZP, which nearly matches triple-zeta accuracy at significantly lower cost [15].

- High-accuracy benchmarking requires triple-zeta basis sets or larger, particularly for properties like dipole moments that converge slowly with basis set size [17].

Experimental Protocol for Functional/Basis Set Validation

When applying DFT to new chemical systems, a systematic validation protocol is essential:

Select Reference Data: Identify high-quality experimental or theoretical data for key properties relevant to your system (e.g., bond lengths, reaction energies, spectroscopic properties).

Choose Test Set: Create a representative set of molecular structures spanning the chemical space of interest.

Compute Benchmark Properties: Run calculations with multiple functional/basis set combinations:

- Geometry Optimizations: Compare molecular structures with experimental crystallographic or spectroscopic data.

- Energy Calculations: Evaluate reaction energies, binding affinities, or barrier heights against reference values.

- Electronic Properties: Calculate dipole moments, orbital energies, or excitation energies if relevant.

Statistical Analysis: Quantify performance using root-mean-square errors (RMSE), mean absolute errors (MAE), and maximum deviations for each property.

Select Optimal Combination: Choose the functional/basis set pair that provides the best balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for your specific application.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of computational chemistry is rapidly evolving, with several emerging trends impacting functional and basis set development:

Machine Learning-Enhanced DFT: Recent research demonstrates that machine learning models trained on high-quality quantum data can discover more universal exchange-correlation functionals. By incorporating not just interaction energies but also potentials that describe how energy changes at each point in space, these models achieve striking accuracy while maintaining manageable computational costs [18]. This approach has shown promise in generating functionals that transfer well beyond their training set.

Large-Scale Datasets for ML Potentials: Initiatives like the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset provide over 100 million molecular configurations with DFT-calculated properties, enabling the training of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that can deliver DFT-level accuracy thousands of times faster [12]. These resources facilitate the development of models that can handle complex chemical spaces including biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes.

Basis Set Corrections for Quantum Computing: As quantum computing emerges for chemical applications, density-based basis-set correction (DBBSC) methods are being integrated with quantum algorithms to accelerate convergence to the complete-basis-set limit, potentially enabling chemically accurate results with fewer qubits [17]. This approach shows particular promise for improving ground-state energies, dissociation curves, and dipole moments.

Specialized Basis Sets for Specific Frameworks: The development of compact, optimized basis sets continues, with recent work focused on creating Gaussian basis sets that maintain accuracy while being less sensitive to grid coarsening, thus enhancing computational efficiency in specific computational frameworks [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for DFT Calculations

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMTKN55 Database | Benchmark Dataset | Comprehensive test set for evaluating method performance across diverse chemical properties | Validation of functional/basis set combinations for main-group thermochemistry [15] |

| vDZP Basis Set | Basis Set | Double-zeta quality basis with minimal BSSE, enables near triple-zeta accuracy at lower cost | General-purpose molecular calculations with various functionals [15] |

| OMol25 Dataset | Training Data | 100M+ molecular configurations with DFT properties for training ML potentials | Developing transferable machine learning force fields [12] |

| Dispersion Corrections (D3/D4) | Empirical Correction | Accounts for van der Waals interactions missing in standard functionals | Non-covalent interactions, supramolecular chemistry, drug binding [15] [1] |

| DBBSC Method | Basis Set Correction | Accelerates convergence to complete-basis-set limit | Improving accuracy of quantum computations and classical calculations [17] |

| Pseudopotentials/ECPs | Effective Core Potentials | Replaces core electrons, reduces basis set size | Systems with heavy elements, large molecular systems [16] |

The critical choices of functionals and basis sets in Density Functional Theory fundamentally determine the reliability and computational feasibility of molecular properties research. As this guide has detailed, these selections must be aligned with specific research goals, whether optimizing drug formulations through API-excipient interactions [1], predicting metabolic stability via cytochrome P450 interactions [19], or designing novel materials with targeted electronic properties. The emerging synergy between traditional DFT, machine learning approaches [18] [12], and quantum computing techniques [17] promises to further expand the boundaries of computational chemistry. By making informed decisions regarding these fundamental computational parameters and leveraging the latest developments in the field, researchers can maximize the predictive power of DFT calculations in drug development and materials science.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as a cornerstone of modern computational quantum chemistry, offering a practical balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for predicting molecular and material properties. Unlike wavefunction-based methods that explicitly solve the complex Schrödinger equation for many-electron systems, DFT simplifies the problem by using the electron density, a function of only three spatial coordinates, as the fundamental variable [20]. The success of DFT hinges entirely on the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which encapsulates all quantum many-body effects [14]. The central challenge in DFT is that the exact form of this functional remains unknown, necessitating various approximations. The journey from the simplest Local Density Approximation (LDA) to sophisticated hybrid functionals represents a continuous effort to improve accuracy while managing computational cost. For researchers, particularly in fields like drug development where predicting molecular interactions is crucial [20], selecting the appropriate functional is not merely a technical step but a fundamental determinant of the reliability and predictive power of their computational models. This guide provides a structured framework for navigating this complex decision-making process, grounded in both theoretical principles and empirical performance.

The Theoretical Landscape: Climbing Jacob's Ladder

The progression of XC functionals is often metaphorically described as "climbing Jacob's Ladder," moving from simple to more complex approximations, with each rung incorporating more physical information to achieve better accuracy [14].

Local Density Approximation (LDA) and Basic Generalizations

The simplest practical starting point is the Local Density Approximation (LDA). LDA assumes that the exchange-correlation energy at any point in space depends only on the electron density at that point, treating the electron density as a uniform gas [20] [14]. Its form is given by: [ E\text{XC}^\text{LDA}[\rho] = \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \epsilon\text{XC}^\text{LDA}(\rho(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ] where ( \epsilon_\text{XC}^\text{LDA} ) is the XC energy density of a homogeneous electron gas [14]. While computationally efficient and historically important, LDA has significant limitations: it systematically overestimates binding energies and predicts shorter bond distances due to its inadequate description of exchange and correlation [14]. This makes it generally unsuitable for quantitative predictions in molecular systems.

The Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) constitutes the next rung on the ladder by introducing a correction for inhomogeneous electron densities. GGA functionals include the gradient of the density (( \nabla \rho )) in addition to the density itself [20] [14]: [ E\text{XC}^\text{GGA} [\rho] = \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \epsilon\text{XC}^\text{GGA}(\rho(\mathbf{r}), \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ] This simple addition leads to substantial improvements. Seminal GGA functionals like BLYP (Becke-Lee-Yang-Parr) and PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) provide much better molecular geometries and atomization energies compared to LDA [14] [21]. PBE, in particular, is widely used as a standard in solid-state physics due to its theoretical foundation [21].

Incorporating Exact Exchange and Addressing Long-Range Interactions

Meta-Generalized Gradient Approximations (meta-GGAs) like TPSS and SCAN incorporate the kinetic energy density (( \tau )) as an additional variable, providing more accurate energetics at a slightly increased computational cost [20] [14]: [ E\text{XC}^\text{mGGA} [\rho] = \int \rho(\mathbf{r}) \epsilon\text{XC}^\text{mGGA} (\rho(\mathbf{r}), \nabla\rho(\mathbf{r}), \tau(\mathbf{r})) d\mathbf{r} ]

A major evolutionary step was the introduction of hybrid functionals, which mix a portion of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange with DFT exchange. This combination helps cancel out the self-interaction error (SIE) inherent in pure DFT functionals, which leads to underestimated band gaps and HOMO-LUMO gaps [14]. The general form of a global hybrid functional is: [ E\text{XC}^\text{Hybrid}[\rho] = a E\text{X}^\text{HF}[\rho] + (1-a) E\text{X}^\text{DFT}[\rho] + E\text{C}^\text{DFT}[\rho] ] where ( a ) is the mixing parameter. A classic example is B3LYP, which uses ( a=0.2 ) (20% HF exchange) and has become a workhorse in computational chemistry for molecular systems [14].

For systems with specific electronic challenges, such as charge-transfer excitations or stretched bonds, Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH) like CAM-B3LYP and ωB97X are particularly effective. These functionals use a distance-dependent mixing scheme, applying more HF exchange at long range to correct the improper asymptotic behavior of pure DFT functionals [14]. This makes them superior for modeling excited states, charge-transfer processes, and zwitterionic systems.

Table 1: Hierarchy of Common Density Functional Approximations

| Functional Type | Key Variables | Representative Examples | Typical Use Cases & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | ( \rho ) | SVWN | Uniform electron gas; historical benchmark; overbinds. |

| GGA | ( \rho, \nabla \rho ) | PBE, BLYP [14] [21] | Standard for solid-state geometry; poor for dispersion. |

| meta-GGA | ( \rho, \nabla \rho, \tau ) | TPSS, SCAN [14] | Improved energetics; sensitive to integration grid. |

| Global Hybrid | Mix of HF & DFT exchange | B3LYP, PBE0 [14] | General-purpose for molecules; improved band gaps. |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | Distance-dependent HF mix | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X [14] | Charge-transfer, excited states, transition states. |

Functional Selection in Practice: A Structured Workflow

Selecting the right functional requires a systematic approach that balances the scientific question, system properties, and computational constraints. The following workflow provides a logical pathway for this decision.

This workflow emphasizes that the primary division in functional selection often lies between molecular systems and extended solids. For molecules, the choice between global and range-separated hybrids is paramount, while for solids, the presence of strong electron correlation becomes a critical deciding factor.

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Modeling a Strongly Correlated Solid (ZnO)

A detailed study on zinc oxide (ZnO) compared the performance of numerous LDA and GGA-based functionals for predicting electronic band structure and optical properties [21]. Standard semilocal functionals like LDA and PBE systematically underestimate the band gap (experimentally ~3.4 eV) due to self-interaction error and the derivative discontinuity of the XC functional. For instance, LDA predicted a band gap of only 0.73 eV, while PBE yielded 1.6 eV [21]. Introducing a Hubbard U parameter to correct for strong electron correlation (LDA+U, PBE+U) significantly improved the band gap prediction. Furthermore, the study highlighted that hybrid functionals, which mix exact HF exchange, provide the most significant improvement in band gap accuracy, closely aligning with experimental values [21].

Protocol for Solid-State Band Gap Calculation:

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain the crystal structure (e.g., from the ICDD database). For ZnO, this is wurtzite with lattice parameters a = 3.2495 Ã… and c = 5.2069 Ã… [21].

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization of the unit cell using a GGA functional like PBE. A plane-wave basis set with pseudopotentials is standard. A kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV and a k-point mesh of 6x6x4 are typical starting points.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the optimized geometry, perform a single-point energy calculation with the target functional (e.g., a hybrid like HSE06 or a GGA+U approach).

- Electronic Structure Analysis: Calculate the electronic density of states (DOS) and band structure along high-symmetry paths in the Brillouin zone. The fundamental band gap is the energy difference between the valence band maximum (VBM) and the conduction band minimum (CBM).

Case Study 2: Benchmarking Functionals for Iron Pnictides

A comparative DFT study of FeAs, a parent compound for iron-pnictide superconductors, evaluated LDA, GGA, LDA+U, GGA+U, and hybrid functionals [22]. The study assessed their performance against experimental data for structural, magnetic, and electronic properties, investigating the origin of a magnetic spiral. The results demonstrated that the choice of functional profoundly impacts the predicted electronic ground state and magnetic ordering. Hybrid functionals and DFT+U methods were essential for correctly describing the localized electronic states in the 3d electrons of iron, which are poorly treated by standard semilocal functionals. This case underscores that for systems with localized d or f electrons, moving beyond standard GGA or LDA is not just beneficial but necessary [22] [23].

Protocol for Functional Benchmarking:

- Property Selection: Define a set of target properties for benchmarking (e.g., lattice constants, bond lengths, band gap, magnetic moment, reaction energy).

- Computational Consistency: Perform all calculations with the same computational parameters (basis set, k-point mesh, convergence criteria) to isolate the effect of the XC functional.

- Multi-Functional Comparison: Calculate the target properties across a range of functionals, from LDA/GGA to hybrids and DFT+U.

- Statistical Validation: Quantify the error for each functional against a reliable reference, which can be high-level quantum chemistry results or experimental data. The mean absolute error (MAE) is a common metric.

Table 2: Performance of Various Functionals for ZnO and FeAs Systems

| System / Property | LDA | GGA (PBE) | GGA+U | Hybrid (HSE) | Experimental Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO Band Gap (eV) [21] | 0.73 eV | 1.60 eV | ~2.7 eV | ~3.4 eV | 3.4 eV |

| ZnO:Mn Band Gap (eV) [21] | — | 1.55 eV | — | — | — |

| FeAs Electronic Structure [22] | Poor for localized d-states | Poor for localized d-states | Improved description | Improved description | — |

| General Cost | Low | Low | Medium | High | — |

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| QM7-X Dataset [24] | Benchmark Dataset | A comprehensive dataset of 42 quantum-mechanical properties for ~4.2 million organic molecules, ideal for training and validating machine learning models and DFT methods. |

| DeepChem [25] | Software Library | An open-source Python library that provides infrastructure for scientific machine learning, including tools for differentiable DFT and training neural network XC functionals. |

| DFTB+ [24] | Software Package | A computational package for performing fast, approximate DFT calculations using a tight-binding approach, useful for pre-screening and large-scale systems. |

| ANI-1x Dataset [24] | Benchmark Dataset | Contains millions of molecular structures and computed properties at the DFT level, serving as a resource for force field and model development. |

The journey from LDA to hybrid functionals represents a continuous refinement in the pursuit of chemical accuracy within Density Functional Theory. There is no single "best" functional for all scenarios. The optimal choice is a sophisticated compromise, dictated by the system under investigation (molecule vs. solid, presence of strong correlation), the properties of interest (ground state geometry vs. band gap vs. reaction energy), and available computational resources. As a rule of thumb, global hybrids like B3LYP or PBE0 are excellent for molecular properties, range-separated hybrids are superior for electronic excitations and charge-transfer, while GGA+U or HSE+U are often necessary for strongly correlated solids [22] [23] [14].

The future of functional development is being shaped by machine learning and differentiable programming. Efforts are underway to create open-source infrastructures, like those in DeepChem, that use machine learning to learn the exchange-correlation functional directly from data [25]. These approaches, trained on comprehensive datasets like QM7-X [24], promise the development of next-generation functionals that are both highly accurate and computationally efficient, potentially overcoming the limitations of traditional approximations. For the practicing researcher, staying informed of these advancements while mastering the current hierarchy of functionals is key to leveraging the full power of DFT in predictive molecular modeling.

From Theory to Therapy: DFT Applications in Drug Design and Formulation

Predicting Drug-Target Binding Sites with Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) Maps

Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) maps provide powerful visual representations of the electrostatic potential created by nuclei and electrons of molecules, projected onto the electron density surface. These maps are indispensable computational tools in structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to predict and analyze non-covalent binding interactions between drug candidates and their protein targets. MEP calculations allow medicinal chemists to visualize regions of molecular surfaces that are electron-rich (partial negative charge, typically colored red) or electron-deficient (partial positive charge, typically colored blue), providing critical insights into potential intermolecular interaction sites such as hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and charge-transfer complexes. When integrated with Density Functional Theory (DFT) for predicting molecular properties, MEP analysis forms a foundational component of modern computational drug discovery pipelines, particularly for identifying and characterizing binding sites in target proteins.

The theoretical foundation of MEP rests on the principles of quantum mechanics, where the electrostatic potential at a point ( r ) in space around a molecule is defined as ( V(r) = \sumA \frac{ZA}{|RA - r|} - \int \frac{\rho(r')}{|r' - r|} dr' ), where ( ZA ) is the charge of nucleus A located at ( R_A ), and ( \rho(r') ) is the electron density function. This equation represents the interaction energy between the molecular charge distribution and a positive unit point charge placed at position ( r ). In drug design contexts, MEP maps help identify complementary electrostatic patterns between ligands and their binding pockets, serving as a critical bridge between quantum mechanical calculations and practical pharmaceutical applications.

Theoretical Foundations: DFT-Generated MEPs

Density Functional Theory Fundamentals

Density Functional Theory has established itself as a practical and versatile method for efficiently studying molecular properties [26]. Unlike wavefunction-based methods that explicitly solve for the electronic wavefunction, DFT focuses on the electron density, ( \rho(r) ), to predict the properties and energies of molecular systems [14]. The success of DFT hinges on the exchange-correlation functional, ( E_{xc}[\rho] ), which incorporates all quantum many-body effects. The exact form of this functional is unknown, necessitating approximations that have evolved through increasing levels of sophistication often described as "climbing Jacob's ladder" [14].

The Kohn-Sham extension of DFT introduced non-interacting electrons that reproduce the same density as the interacting system. The total energy functional in Kohn-Sham DFT is expressed as: [ E[\rho] = Ts[\rho] + V{ext}[\rho] + J[\rho] + E_{xc}[\rho] ] where:

- ( T_s[\rho] ) is the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons

- ( V_{ext}[\rho] ) is the external potential energy

- ( J[\rho] ) is the classical Coulomb energy

- ( E_{xc}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation energy [14]

Table 1: Evolution of DFT Exchange-Correlation Functionals for Molecular Property Prediction

| Functional Type | Description | Representative Functionals | Typical Use Cases in Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/LSDA | Local (Spin) Density Approximation; uniform electron gas model | SVWN | Historical reference; limited accuracy for molecular systems |

| GGA | Generalized Gradient Approximation; includes first derivative of density | BLYP, BP86, PBE | Geometry optimizations; moderate accuracy for energetics |

| mGGA | meta-GGA; includes kinetic energy density | TPSS, M06-L, r²SCAN, B97M | Improved energetics; reaction barriers |

| Global Hybrids | Mix DFT exchange with Hartree-Fock exchange | B3LYP, PBE0, B97-3 | Balanced accuracy for diverse molecular properties |

| Range-Separated Hybrids | Non-uniform mixing of HF and DFT exchange based on interelectronic distance | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X, ωB97M | Charge-transfer species; excited states; systems with stretched bonds |

Calculating MEP from DFT-Generated Electron Density

Once a DFT calculation converges to provide the ground-state electron density, the MEP can be computed directly using the fundamental equation ( V(r) ) mentioned previously. The accuracy of the resulting MEP maps depends critically on the choice of exchange-correlation functional. "Pure" density functionals suffer from self-interaction error (SIE), where each electron erroneously interacts with its own contribution to the electron cloud [14] [26]. This results in excessive delocalization of electron density and affects the accuracy of computed electrostatic potentials, particularly in the asymptotic regions where the potential should decay as ( 1/r ) but instead decays exponentially [26].

Hybrid functionals that incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange partially mitigate these issues by reducing self-interaction error. Range-separated hybrids, which employ a higher fraction of HF exchange at long range, are particularly effective for producing accurate MEP maps in regions relevant to molecular recognition, as they properly describe the electrostatic potential decay at molecular surfaces and interfaces [14]. For drug-target binding predictions, where accurate representation of intermolecular electrostatic interactions is crucial, the use of range-separated hybrid functionals with sufficient basis set flexibility is generally recommended.

Computational Workflow for MEP-Based Binding Site Prediction

Integrated Protocol for Binding Site Analysis

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for predicting drug-target binding sites using DFT-generated MEP maps:

Diagram 1: MEP-Based Binding Site Prediction Workflow - This flowchart outlines the comprehensive process from initial target preparation through to drug design applications, highlighting the central role of DFT calculations and MEP analysis.

Target Preparation and System Setup

The initial phase involves preparing the protein target and ligand molecules for quantum chemical calculations. For protein targets, this typically begins with selecting a high-resolution crystal structure from the Protein Data Bank, followed by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning appropriate protonation states to ionizable residues at physiological pH, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks. For the MEP pathway targets like DXS, DXR, and IspF in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, researchers often rely on homology models when experimental structures are unavailable, leveraging known structures from orthologous organisms like Deinococcus radiodurans or Escherichia coli [27] [28]. Small molecule ligands require geometry optimization at an appropriate DFT level, typically using hybrid functionals like B3LYP with triple-zeta basis sets.

System setup for DFT calculations requires careful selection of computational parameters. The trade-off between accuracy and computational cost must be balanced, particularly for large systems like protein binding pockets. For comprehensive binding site analysis, a multi-scale approach is often employed where the entire protein is treated with molecular mechanics methods, while the binding pocket with key residues and ligand is subjected to higher-level DFT calculations—a strategy known as Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM). This approach maintains quantum mechanical accuracy where it matters most for electrostatic interactions while maintaining computational tractability.

DFT Calculation Specifications for MEP Mapping

The core DFT calculations for generating accurate MEP maps require careful functional and basis set selection. The following technical specifications represent current best practices:

Table 2: DFT Calculation Parameters for MEP-Based Binding Site Prediction

| Calculation Phase | Recommended Functional | Basis Set | Solvation Model | Grid Settings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Pre-optimization | B3LYP | 6-31G(d) | IEFPCM (Water) | FineGrid (Lebedev 110) |

| Protein Binding Pocket | ωB97X-D | 6-31G(d) | COSMO (ε=4) | UltraFineGrid (Lebedev 290) |

| Single-Point MEP Calculation | ωB97M-V | def2-TZVP | SMD (Water) | UltraFineGrid (Lebedev 590) |

| High-Accuracy Validation | Double-Hybrid Functionals (e.g., DSD-BLYP) | aug-cc-pVTZ | Explicit Solvent Shell + SMD | Pruned (99,590) |

For MEP visualization, the electrostatic potential is typically mapped onto the electron density surface with an isovalue of 0.001 a.u. (electrons/bohr³), which corresponds approximately to the van der Waals surface. The color scheme follows the convention: red (negative potential, nucleophilic regions), blue (positive potential, electrophilic regions), and green/white (neutral potential). These visualizations enable immediate identification of potential interaction hotspots where complementary electrostatic patterns between ligand and protein could drive binding affinity.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for MEP Analysis

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MEP-Based Binding Site Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application in MEP Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, PSI4 | DFT Calculations | Perform electronic structure calculations to generate electron densities for MEP mapping |

| Molecular Visualization | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera, GaussView | MEP Visualization & Analysis | Visualize 3D MEP maps on molecular surfaces and analyze complementary binding regions |

| Docking & Binding Analysis | AutoDock, GOLD, Schrodinger Suite | Binding Pose Prediction | Generate putative binding modes for MEP complementarity analysis |

| Force Field Parameterization | CGenFF, ACPYPE, MATCH | MM Parameter Generation | Create parameters for QM/MM simulations of protein-ligand complexes |

| Binding Affinity Prediction | MM/PBSA, LIE, FEP | Affinity Estimation | Quantify binding energies after MEP-guided pose selection |

The computational tools listed in Table 3 represent the essential software ecosystem for implementing MEP-based binding site prediction. These tools interface to create an integrated workflow where DFT calculations provide the fundamental electronic structure information, visualization tools enable intuitive interpretation of MEP maps, and docking/binding affinity tools translate these insights into quantitative predictions of binding energetics. The message passing neural networks and other deep learning approaches emerging in drug-target binding affinity prediction can complement these traditional physical-based methods by learning complex patterns from large datasets [29] [30].

Advanced Methodologies: Integrating MEP with Machine Learning

The integration of MEP analysis with machine learning represents a cutting-edge advancement in binding site prediction. Deep learning models for drug-target binding affinity (DTA) prediction, such as those using message passing neural networks (MPNN) for molecular embedding and self-supervised learning for protein representation, can be enhanced by incorporating MEP-derived features as physical descriptors [29]. These hybrid approaches leverage both the quantum mechanical accuracy of MEP analysis and the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning.

For example, the undirected cross message passing neural network (undirected-CMPNN) framework improves molecular representation by enhancing information exchange between atoms and bonds [29]. When MEP-derived atomic features supplement traditional atom and bond descriptors, the model gains direct access to quantum mechanical electrostatic information that drives molecular recognition. Similarly, protein representation learning using methods like CPCProt and Masked Language Modeling can benefit from MEP-based pocket descriptors that capture the electrostatic landscape of binding sites [29].

The attention mechanisms in these deep learning architectures can highlight regions of strong electrostatic complementarity, providing both predictive accuracy and interpretability. By visualizing attention weights alongside MEP maps, researchers can identify which electrostatic interactions the model deems most important for binding, creating a powerful feedback loop between physical theory and data-driven pattern discovery.

Case Study: MEP Pathway Targets in Antitubercular Drug Discovery

MEP Pathway as a Therapeutic Target

The methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis represents an excellent case study for MEP-based binding site prediction. This pathway is absent in humans but essential for Mtb, making its enzymes promising targets for novel antitubercular agents [28]. Among the seven MEP pathway enzymes, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS), DXR, and IspF are considered the most promising drug targets [28]. The following diagram illustrates the MEP pathway and its key targets:

Diagram 2: MEP Pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis - This metabolic pathway shows the sequence of enzymatic reactions for isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis, highlighting DXS, DXR, and IspF as the most promising drug targets.

Application to DXPS Inhibitor Design

DXS presents particular challenges for inhibitor design due to its large, hydrophilic binding site that accommodates the cofactor thiamine diphosphate (ThDP) and substrates pyruvate and D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [27] [28]. Standard structure-based virtual screening approaches often fail for such targets, necessitating innovative strategies like the "pseudo-inhibitor" concept that combines ligand-based and structure-based methods [27].

Researchers successfully applied MEP analysis to identify key anchor points in the DXS binding site, particularly focusing on His304 in Deinococcus radiodurans DXS (analogous to His296 in Mtb DXS) [27]. By generating MEP maps for weak inhibitors like deazathiamine (DZT) and comparing them with the MEP of the native cofactor ThDP, they identified conserved electrostatic complementarity patterns that guided ligand-based virtual screening. This approach led to the identification of novel drug-like antitubercular hits with submicromolar inhibition constants against Mtb DXS [27] [31].