Gradient-Corrected vs Hybrid Density Functionals: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Development

This article provides a detailed comparison between gradient-corrected (GGA) and hybrid density functionals, essential tools in Density Functional Theory (DFT) for computational chemistry and drug discovery.

Gradient-Corrected vs Hybrid Density Functionals: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison between gradient-corrected (GGA) and hybrid density functionals, essential tools in Density Functional Theory (DFT) for computational chemistry and drug discovery. It covers the foundational theory behind these functionals, explores their methodological applications in predicting molecular properties relevant to biomedicine, addresses common computational challenges and optimization strategies, and presents a validation framework based on performance benchmarks. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current knowledge to inform functional selection for accurate and efficient electronic structure calculations.

The Theoretical Landscape: From LDA to Meta-GGAs and Hybrids

Theoretical Foundations of Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a foundational computational method used extensively in chemistry, physics, and materials science for investigating electronic structure. In principle, DFT is an exact theory; however, its practical implementation within the Kohn-Sham (KS) framework requires approximation of the exchange-correlation (XC) energy functional, which accounts for quantum mechanical electron interactions. The accuracy of any DFT calculation is therefore intrinsically tied to the quality of the chosen XC functional approximation [1].

The Kohn-Sham approach defines the total energy of a system through several components [2]: [ E{DFT}[{}^{1}D] = Ts[{}^{1}D] + V[\rho] + F{xc}[\rho] ] where ( Ts ) represents the non-interacting kinetic energy, ( V[\rho] ) encompasses electron-electron, electron-nuclei, and nuclei-nuclei Coulomb interactions, and ( F{xc}[\rho] ) is the exchange-correlation functional, which captures all remaining quantum mechanical effects. The primary challenge in modern DFT development stems from the fact that the exact form of ( F{xc}[\rho] ) remains unknown, necessitating increasingly sophisticated approximations [2].

Classification of Exchange-Correlation Functionals

Jacob's Ladder of DFT

XC functionals are systematically classified using "Jacob's Ladder," a conceptual framework introduced by Perdew that categorizes functionals based on the physical information they incorporate, with ascending rungs theoretically offering improved accuracy [2]:

- Local Spin Density Approximations (LSDA): The first rung, depending solely on the local electron density at each point in space [2] [3].

- Generalized Gradient Approximations (GGA): The second rung, incorporating both the electron density and its gradient to account for inhomogeneities [2] [3].

- Meta-GGAs (mGGAs): The third rung, adding dependence on the kinetic energy density for improved accuracy [2] [3].

- Hybrids and Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH): The fourth rung, mixing exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation [2] [1].

- Double Hybrids: The fifth rung, incorporating both exact exchange and perturbative correlation corrections from wavefunction theory [3].

Functional Development Philosophies

Two distinct philosophical approaches guide XC functional development [2]:

- Empirical Functionals: Parameterized to reproduce accurate experimental or theoretical reference data for chemical systems (e.g., Minnesota functionals like M06-L, M11-L).

- Non-Empirical (Ab-Initio) Functionals: Constructed to obey known physical constraints and mathematical conditions of the exact functional (e.g., TPSS, revTPSS, SCAN).

Comparative Analysis: Gradient-Corrected vs. Hybrid Functionals

Fundamental Formulations

Gradient-Corrected Functionals (GGA) build upon LDA by incorporating the gradient of the electron density (( \nabla\rho )), enabling them to respond to inhomogeneities in the electron distribution. Common GGA functionals include BP86 (Becke exchange + Perdew correlation), PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof), and BLYP (Becke exchange + Lee-Yang-Parr correlation) [3].

Hybrid Functionals combine a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange and correlation components, theoretically justified through the adiabatic connection formula [1]. The general form for global hybrids is: [ E^{\text{hyb}}{xc} = a E^{\text{HF}}x + (1-a) E^{\text{DFT}}x + E^{\text{DFT}}c ] where ( a ) represents the mixing coefficient for exact exchange. Range-separated hybrids further refine this concept by using exact exchange for long-range interactions while maintaining DFT exchange for short-range interactions [1].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Recent comprehensive studies have systematically evaluated the performance of hundreds of XC functionals. One benchmark assessed 155 hybrid functionals available in the LIBXC library, comparing them against high-accuracy reference methods like FCI and CCSD(T) [1]. Another study evaluated nearly 200 different XC functionals within both unrestricted Kohn-Sham (UKS) DFT and a hybrid 1-electron Reduced Density Matrix Functional Theory (1-RDMFT) framework [2].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Selected XC Functional Types

| Functional Type | Representative Examples | Exact Exchange % | Key Strengths | Known Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE, BLYP, BP86 | 0% | Computational efficiency, acceptable for metallic systems | Systematic errors in band gaps, self-interaction error |

| Meta-GGA | TPSS, SCAN, M06-L | 0% | Improved accuracy for geometries and bond energies | More parameterized, potential overfitting |

| Global Hybrid | B3LYP, PBE0 | 20-27% | Balanced performance for diverse chemical properties | Remaining delocalization error |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | ωB97, LC-ωPBE | Varies with distance | Accurate for charge-transfer excitations, band gaps | Parameter dependence, system-specific tuning |

| Double Hybrid | B2PLYP, DSD-BLYP | MP2 correlation correction | High accuracy for thermochemistry | High computational cost |

Table 2: Error Analysis for Key Chemical Properties Across Functional Types

| Functional Type | Atomization Energies (kcal/mol) | Bond Lengths (Å) | Band Gaps (eV) | Reaction Barriers (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | 10-25 | 0.01-0.02 | ~1-2 (underestimated) | 5-10 (underestimated) |

| Meta-GGA | 5-15 | 0.005-0.015 | ~0.5-1.5 (underestimated) | 3-8 (improved) |

| Global Hybrid | 3-8 | 0.003-0.010 | ~0.3-1.0 (improved) | 2-5 (more accurate) |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | 2-7 | 0.002-0.008 | ~0.1-0.5 (significantly improved) | 2-4 (accurate) |

Methodological Protocols for Functional Assessment

Standardized evaluation methodologies enable meaningful comparisons between functional types:

Reference Data Generation: High-accuracy reference data is obtained from wavefunction-based methods including Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) for small systems and CCSD(T) for larger molecules. Ionization Potential Equation-of-Motion Coupled Cluster (IP-EOM-CCSD) provides reference values for ionization potentials [1].

Error Metrics: Quantitative assessment utilizes several error measures [1]:

- Relative errors of XC potential: ( \Delta v{xc} = \frac{\|\delta v{xc}\|{L2}}{\|v{xc}^{ref}\|{L_2}} )

- Relative errors of electron density: ( \Delta\rho = \frac{\|\delta\rho\|{L2}}{\|\rho^{ref}\|{L2}} )

- Absolute relative errors for total energies and ionization potentials

Potential Inversion Procedures: For hybrid functionals, KS XC potentials are obtained through Wu-Yang inversion of self-consistently obtained generalized Kohn-Sham density matrices, enabling comparison with reference potentials [1].

Addressing Theoretical Challenges: Strong Correlation

A significant challenge for conventional DFT approximations remains the accurate description of strongly correlated systems characterized by multi-reference states, where multiple Slater determinants contribute significantly to the wavefunction [2]. Both gradient-corrected and standard hybrid functionals struggle with these systems due to the inherently non-local nature of strong correlation effects [2].

Advanced methodologies have emerged to address these limitations:

Unrestricted Kohn-Sham (UKS): Allows alpha and beta electrons to occupy different spatial orbitals, breaking spin symmetry to mimic strong correlation effects [2].

Fractional Occupation Approaches: Enforce Perdew-Parr-Levy-Balduz (PPLB) conditions with fractional spins and charges to recover piecewise linearity between integer electron numbers [2].

1-electron Reduced Density Matrix Functional Theory (1-RDMFT): An alternative approach that captures strong correlation through fractional occupations of the 1-RDM. Recent developments combine 1-RDMFT with standard XC functionals in a hybrid framework (DFA 1-RDMFT) that maintains computational efficiency while improving accuracy for strongly correlated systems [2].

Research Workflow and Computational Tools

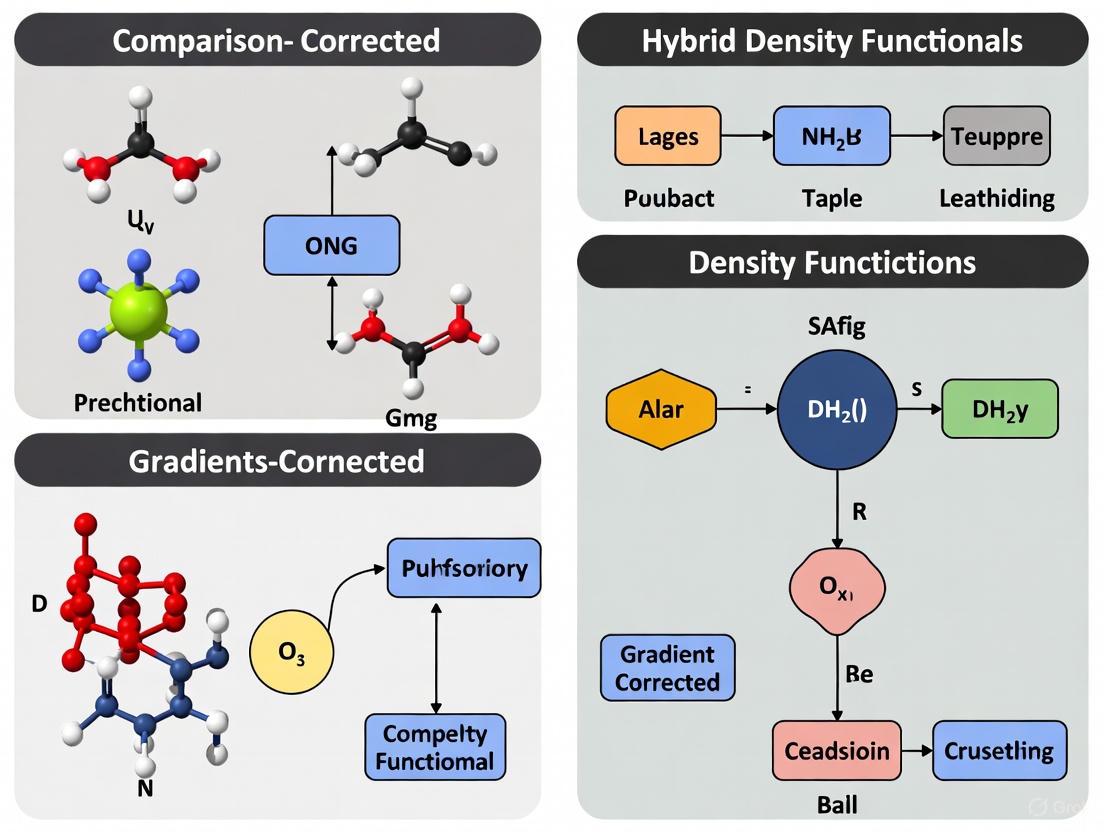

Diagram 1: DFT Research Workflow for Functional Comparison

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| LIBXC Library | Provides standardized implementation of ~200 XC functionals for systematic benchmarking | Used in studies evaluating 155 hybrid and 200 total functionals [2] [1] |

| Wavefunction Theory Methods | Generate reference data for functional validation (FCI, CCSD(T), IP-EOM-CCSD) | Reference methods in functional assessment studies [1] |

| Potential Inversion Algorithms | Obtain XC potentials from electron densities for functional quality assessment | Wu-Yang inversion procedure [1] |

| Error Metrics | Quantify deviations from reference data for systematic functional comparison | L2 norm relative errors, absolute relative errors [1] |

| Strong Correlation Diagnostics | Identify multi-reference character and assess functional performance for challenging systems | Fractional occupation numbers, 1-RDMFT corrections [2] |

The comparative analysis between gradient-corrected and hybrid density functionals reveals a complex trade-off between computational efficiency, theoretical rigor, and application-specific accuracy. While gradient-corrected functionals like GGAs remain valuable for high-throughput screening and metallic systems, hybrid functionals generally provide superior accuracy for molecular properties, band gaps, and reaction barriers.

Future functional development is increasingly focusing on addressing fundamental limitations through approaches like 1-RDMFT for strong correlation [2], systematic assessment of XC potentials beyond energy evaluations [1], and machine-learning assisted functional design. The optimal choice between gradient-corrected and hybrid functionals ultimately depends on the specific chemical system, property of interest, and available computational resources, with the ongoing benchmarking efforts providing essential guidance for researchers across chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

Understanding the 'Jacob's Ladder' of DFT Functionals

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as one of the most widely used computational methods in quantum chemistry and materials science, enabling researchers to predict molecular structures, energies, and properties. The framework of "Jacob's Ladder," introduced by John Perdew, provides a systematic classification of exchange-correlation functionals, organizing them into ascending rungs of increasing sophistication and accuracy. Each rung incorporates more physical ingredients, moving from local electron density to occupied and unoccupied orbitals, thereby offering improved descriptions of electronic interactions. This guide objectively compares the performance of functionals from different rungs, specifically examining gradient-corrected (lower rungs) versus hybrid (higher rungs) functionals, with a focus on applications relevant to drug development and materials science.

The fundamental challenge in DFT is the exchange-correlation functional, which describes how electrons interact with each other. While a universal functional exists in theory, its exact form remains unknown, forcing researchers to use approximations. As one ascends Jacob's Ladder, these approximations become more sophisticated and potentially more accurate, but often at increased computational cost. Understanding the performance trade-offs between different rungs is essential for researchers selecting methods for specific applications, particularly in fields like drug development where reliable predictions of molecular properties can accelerate discovery processes.

The Theoretical Framework of Jacob's Ladder

Anatomizing the Rungs

Jacob's Ladder categorizes functionals into five distinct rungs, each adding complexity to better approximate the exact exchange-correlation functional:

LDA (Local Density Approximation) represents the first rung, using only the local electron density at each point in space. While simple and computationally inexpensive, it often provides limited accuracy due to its oversimplified treatment of electron interactions.

GGA (Generalized Gradient Approximation) forms the second rung, incorporating both the local electron density and its gradient. This accounts for inhomogeneities in the electron density, offering significant improvements over LDA. Common GGA functionals include PBE and PW91.

meta-GGA constitutes the third rung, adding the kinetic energy density or the Laplacian of the electron density. This provides information about orbital kinetics, further improving accuracy. Examples include SCAN and its variant r2SCAN-3c.

Hybrid functionals define the fourth rung, mixing a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange. This addresses systematic errors in pure DFT descriptions of electron exchange. Popular hybrids include B3LYP, PBE0, and HSE06.

Double Hybrid functionals represent the fifth and highest rung, incorporating both exact exchange and perturbative correlation. These methods offer high accuracy but at substantially increased computational cost. Examples include DSD-BLYP-D3BJ.

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical structure of Jacob's Ladder and the key ingredients added at each level:

Functional Classification in Research

Table: Classification of Common DFT Functionals by Rung

| Rung | Functional Type | Key Ingredients | Example Functionals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | GGA | Electron density, density gradient | PBE, PW91, BLYP |

| 3 | meta-GGA | Electron density, density gradient, kinetic energy density | SCAN, r2SCAN-3c, mBJ |

| 4 | Hybrid | GGA/meta-GGA + exact Hartree-Fock exchange | B3LYP, PBE0, HSE06, ωB97M-D3BJ |

| 5 | Double Hybrid | Hybrid + perturbative correlation | DSD-BLYP-D3BJ |

Comparative Performance Analysis Across Chemical Properties

Band Gap Predictions in Solids

Accurate prediction of band gaps is crucial for semiconductor research and optoelectronic applications. A systematic benchmark study comparing many-body perturbation theory (MBPT) with DFT functionals revealed significant performance differences across rungs [4]. The study evaluated 472 non-magnetic materials and found that meta-GGA and hybrid functionals substantially reduce the systematic band gap underestimation common with lower-rung functionals.

Table: Band Gap Prediction Performance for Solids [4]

| Method | Functional Type | RMSE (eV) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| mBJ | meta-GGA (Rung 3) | 0.45 | Medium |

| HSE06 | Hybrid (Rung 4) | 0.41 | High |

| QSGW^ | Many-Body Perturbation | 0.21 | Very High |

The benchmark demonstrated that while hybrid functionals like HSE06 offer improved accuracy over meta-GGA functionals like mBJ, the best MBPT methods (QSGW^) provide superior performance, nearly matching experimental accuracy and even flagging questionable experimental measurements [4]. This illustrates the continued trade-off between computational cost and accuracy even at the higher rungs of Jacob's Ladder.

Bond Dissociation Enthalpy (BDE) Prediction

Bond strength prediction is fundamental for understanding chemical reactivity, particularly in drug metabolism studies. The ExpBDE54 benchmark, comprising 54 experimental gas-phase BDEs, provides a slim benchmark for evaluating computational methods [5]. The study compared various DFT functionals alongside semiempirical methods and neural network potentials, offering insights into the accuracy-speed tradeoff.

Table: BDE Prediction Performance (RMSE in kcal·mol⁻¹) [5]

| Method | Functional Type | RMSE | Relative Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| r2SCAN-D4/def2-TZVPPD | meta-GGA (Rung 3) | 3.6 | 1.0x |

| ωB97M-D3BJ/def2-TZVPPD | Hybrid (Rung 4) | 3.7 | 0.5x |

| B3LYP-D4/def2-TZVPPD | Hybrid (Rung 4) | 4.1 | 2.0x |

| r2SCAN-3c | meta-GGA (Rung 3) | ~4.0 | 2.5x |

Notably, the specially constructed r2SCAN-3c meta-GGA functional offered the best speed-accuracy tradeoff, being more accurate than any double-zeta basis set method while providing a 2.5x speedup over r2SCAN-D4 with a larger basis set [5]. This demonstrates that meta-GGA functionals can sometimes outperform more computationally expensive hybrid functionals for specific applications like BDE prediction.

Surface Adsorption and Catalytic Properties

The adsorption of CO on the Pt(111) surface represents a classic case where traditional DFT functionals fail to predict the correct adsorption site. Experimental evidence clearly shows CO prefers top sites, but early DFT calculations with local-density or generalized gradient approximation functionals incorrectly favored high-coordination fcc hollow sites [6]. This failure was attributed to incorrect description of the HOMO-LUMO gap by standard functionals.

A comparative study using PW91 (GGA) and B3LYP (hybrid) revealed that hybrid functionals can correct this deficiency. While PW91 calculations maintained the incorrect site preference (fcc > hcp > bridge > top), B3LYP correctly identified the top site as most stable, aligning with experimental observations [6]. This improvement was linked to the inclusion of exact exchange in hybrid functionals, which provides a better description of the HOMO-LUMO gap and electronic interactions at surfaces.

Excited-State Properties

Excited-state calculations present particular challenges for DFT methods. A benchmark study of excited-state dipole moments compared ΔSCF methods with TDDFT and wavefunction-based approaches [7]. The study found that while ΔSCF methods offer technical advantages for property calculations and can access certain doubly-excited states inaccessible to conventional TDDFT, they don't necessarily improve systematically on TDDFT results across all cases.

For excited-state dipole moments, range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP produced the lowest average relative errors (~28%), significantly outperforming standard hybrids like PBE0 and B3LYP (~60% error) [7]. This highlights the importance of functional selection for specific electronic properties, with range-separated hybrids offering particular advantages for charge-transfer states and excited-state properties.

Another benchmark focusing on dark transitions in carbonyl-containing compounds found that coupled-cluster methods (particularly CC3) provide the most reliable description of excitation energies and oscillator strengths for these challenging states [8]. While hybrid functionals in TDDFT calculations offer reasonable performance for many excited states, their accuracy diminishes for dark transitions with near-zero oscillator strengths, which are particularly important in atmospheric chemistry and photochemical applications.

Magnetic Properties

The calculation of magnetic exchange coupling constants in transition metal complexes presents another challenging test case for DFT functionals. A study evaluating twelve range-separated hybrid functionals found that Scuseria functionals with moderately less short-range Hartree-Fock exchange and no long-range Hartree-Fock exchange outperformed other functionals with higher Hartree-Fock exchange percentages [9]. This demonstrates that simply increasing exact exchange content doesn't systematically improve performance across all chemical properties, and careful parameterization is essential for specific applications.

Emerging Methods and Future Directions

Machine-Learning Enhanced Functionals

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) are opening new possibilities for developing more accurate exchange-correlation functionals. Researchers at the University of Michigan have demonstrated that ML models trained on quantum many-body data can discover more universal XC functionals [10] [11]. By including both interaction energies of electrons and the potentials describing how that energy changes at each point in space, their approach achieved third-rung DFT accuracy at second-rung computational cost [11].

This ML approach represents a potential paradigm shift in functional development. Rather than manually constructing functionals based on physical ingredients, ML models can learn the functional form directly from high-accuracy quantum many-body calculations. The method has shown promising transferability, working accurately for systems beyond the small set of atoms and molecules it was trained on [10]. This approach may eventually help bridge the gap between DFT and more accurate but computationally expensive quantum many-body methods.

Neural Network Potentials

Neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on large quantum chemical datasets are emerging as powerful alternatives to traditional DFT for specific applications. The OMol25 dataset has enabled the creation of pretrained NNPs that can predict molecular energies in various charge and spin states [12]. Surprisingly, these models can match or exceed the accuracy of low-cost DFT and semiempirical quantum mechanical methods for predicting experimental reduction-potential and electron-affinity values, despite not explicitly considering charge- or spin-based physics [12].

For BDE prediction, OMol25's eSEN Conserving Small neural network potential demonstrated competitive performance with an RMSE of 3.6 kcal·mol⁻¹, defining the Pareto frontier for accuracy-speed tradeoffs alongside semiempirical methods [5]. This suggests that NNPs may soon challenge traditional DFT functionals for high-throughput screening applications in drug discovery and materials science.

Experimental Protocols & Computational Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a typical computational workflow for benchmarking DFT functionals, synthesized from multiple studies cited in this guide:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Benchmarking

| Research Tool | Type | Function/Role | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical Method | Initial geometry optimization | Provides starting structures for higher-level calculations [5] |

| def2-TZVPPD | Gaussian Basis Set | Describes molecular orbitals | Balanced accuracy/efficiency for molecular calculations [5] |

| D3BJ/D4 | Dispersion Correction | Accounts for van der Waals interactions | Improves accuracy for non-covalent interactions [5] |

| r2SCAN-3c | Composite Method | All-electron calculation with corrections | "Swiss-army knife" for molecular properties [5] |

| OMol25 | Neural Network Potential | Machine-learning energy prediction | Rapid screening of molecular properties [12] |

The evidence from current benchmarking studies reveals that the choice between gradient-corrected and hybrid functionals depends critically on the target property and application context:

For solid-state band gaps, hybrid functionals like HSE06 provide significant improvements over meta-GGA functionals, though many-body perturbation methods remain the gold standard for highest accuracy [4]. For bond dissociation enthalpies, meta-GGA functionals like r2SCAN-3c and r2SCAN-D4 offer the best accuracy-speed tradeoff, sometimes outperforming more expensive hybrid functionals [5]. For surface adsorption and catalytic properties, hybrid functionals correct systematic errors present in GGA functionals, as demonstrated by the CO/Pt(111) test case [6]. For excited-state properties, range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP show particular advantages, though coupled-cluster methods remain most reliable for challenging cases like dark transitions [7] [8].

The emergence of machine-learning enhanced functionals and neural network potentials promises to further reshape the computational landscape, potentially bypassing some limitations of traditional DFT approximations [10] [11]. As these methods mature, they may provide researchers with new tools that combine the accuracy of high-level quantum chemistry with the computational efficiency of semiempirical methods.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, strategic functional selection requires careful consideration of target properties, system size, and computational resources. While hybrid functionals generally offer improved accuracy across diverse chemical systems, meta-GGA functionals can provide the best balance of performance and computational cost for specific applications like high-throughput screening of molecular properties.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a fundamental computational method in quantum chemistry and materials science for studying the electronic structure of molecules and materials. Within this framework, the exchange-correlation functional is crucial, accounting for quantum mechanical effects not captured by the classical electron-electron repulsion. The Gradient-Corrected Approximation (GGA) represents a significant advancement over the initial Local Density Approximation (LDA). While LDA treats the electron density as a uniform gas, GGA introduces an explicit dependence on the density gradient, dramatically improving the accuracy of calculated molecular properties [13] [14].

This guide objectively compares the performance of GGA functionals against other classes of functionals, particularly hybrid and meta-GGA. Understanding GGA's core concepts, capabilities, and inherent limitations is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the appropriate functional for their specific applications, from predicting molecular properties to designing novel pharmaceutical formulations [15].

Core Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Principles of GGA

The central idea behind GGA is to correct the inaccuracies of LDA by incorporating the electron density's gradient. Mathematically, the GGA exchange-correlation energy is expressed as:

[ E{XC}^{GGA}[n] = \int \varepsilon{X}^{LDA}(n(\vec{r})) F_{XC}(n(\vec{r}), \nabla n(\vec{r})) d^3r ]

Here, (n(\vec{r})) is the electron density, (\nabla n(\vec{r})) is its gradient, and (F_{XC}) is a enhancement factor that introduces the gradient dependence [14]. This formulation allows GGA to account for the realistic inhomogeneity of electron density in molecules and materials, which LDA fails to describe adequately [16].

GGA within Jacob's Ladder Classification

DFT functionals are often organized using John Perdew's "Jacob's Ladder" classification, which arranges functionals in order of increasing complexity and accuracy. On this ladder, GGA occupies the second rung, above LDA (first rung) and below meta-GGA (third rung), hybrid (fourth rung), and double-hybrid (fifth rung) functionals [13]. Each successive rung incorporates more intricate information about the electron density, improving accuracy at the cost of increased computational expense. GGA's position represents a critical balance, offering substantial improvement over LDA while remaining computationally efficient compared to higher-rung methods [17].

Common GGA Functionals and Their Composition

GGA functionals are typically constructed from separate exchange and correlation components. Researchers can use standardized pairings or create their own combinations. The table below summarizes some of the most widely used GGA functionals and their components.

Table 1: Common GGA Functionals and Their Components

| Functional Name | Exchange Functional | Correlation Functional | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBE [14] [3] | PBEx | PBEc | Non-empirical; widely used in solid-state and materials science. |

| BLYP [14] [18] | Becke 88 | LYP | Popular in quantum chemistry for molecular properties. |

| BP86 [3] | Becke 88 | Perdew 86 | Often used for geometric optimization and molecular structures. |

| PW91 [14] [3] | PW91x | PW91c | An earlier Perdew-Wang functional that preceded PBE. |

Performance Comparison: GGA vs. Other Functional Types

Comparison of Theoretical Ingredients and Computational Cost

The different rungs of Jacob's Ladder incorporate increasingly complex ingredients to model exchange and correlation effects. This directly impacts their computational cost and typical application areas.

Table 2: Functional Classes Compared by Ingredients, Cost, and Typical Use

| Functional Class | Key Ingredients | Computational Cost | Typical Application Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | Local Spin Density ((n\uparrow), (n\downarrow)) [13] | Very Low | Uniform electron gas, simple metals [15] |

| GGA | Density + Density Gradient ((\nabla n)) [13] [14] | Low | Molecular geometries, hydrogen bonds, general-purpose [19] [15] |

| meta-GGA | Density Gradient + Kinetic Energy Density ((\tau)) [13] [17] | Moderate | Atomization energies, band gaps, reaction barriers [17] [20] |

| Hybrid | GGA/meta-GGA + Exact (HF) Exchange [13] [18] | High | Thermochemistry, reaction mechanisms, spectroscopy [18] [15] |

| Double Hybrid | Hybrid + MP2 Correlation [13] | Very High | High-accuracy energetics, non-covalent interactions [13] |

Figure 1: Jacob's Ladder of DFT Functionals. Each rung adds new ingredients to improve accuracy: the electron density gradient (∇n) for GGA, the kinetic energy density (τ) for meta-GGA, exact Hartree-Fock exchange for hybrids, and second-order perturbation theory (MP2) for double hybrids [13].

Quantitative Benchmarking on Molecular Properties

The performance of different functionals is quantitatively assessed using standardized benchmark databases like GMTKN55, which contains over 1500 reference energies for various chemical reactions [21]. The following table summarizes benchmark data, illustrating the progressive improvement in accuracy from GGA to hybrid and meta-GGA functionals.

Table 3: Benchmark Performance of Different Functional Types (WTMAD-2 in kcal/mol)

| Functional Type | Example Functional | WTMAD-2 | Key Improvement Over GGA |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | BLYP [21] | ~12-24 (est.) | Baseline |

| meta-GGA | SCAN [17] | Improved over GGA | Better treatment of kinetic energy density [20] |

| Hybrid GGA | B3LYP [21] | ~8-12 (est.) | Incorporation of exact exchange |

| Advanced Hybrid | DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ) [21] | 3.08 | High-accuracy design for diverse chemistry |

| Functional Ensemble | DENS24 [21] | 1.62 | Combines predictions from multiple functionals |

The data shows that while GGA functionals like BLYP provide a solid foundation, they are systematically outperformed by more modern functionals. Hybrids and meta-GGAs can reduce the error (WTMAD-2) by a factor of two or more. Notably, the recently developed DENS24 ensemble of functionals demonstrates that combining multiple functionals can achieve record-low errors, significantly surpassing even the best individual functionals [21].

Limitations of GGA Functionals

Despite their utility, GGA functionals possess several well-documented limitations:

Systematic Underestimation of Band Gaps: In materials science, GGA functionals like PBE are notorious for significantly underestimating the band gaps of semiconductors and insulators compared to experimental values. This "band gap problem" is attributed to the delocalization error of pure functionals [20]. For example, while hybrid functionals like HSE06 can achieve a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.687 eV for band gaps, GGA functionals like PBE exhibit a much larger MAE of 1.184 eV [20].

Poor Description of Dispersion Interactions: Standard GGA functionals do not adequately capture long-range, non-covalent van der Waals (dispersion) forces [13] [15]. This makes them unreliable for simulating processes like molecular crystal formation, adsorption on surfaces, or protein-ligand binding without explicit empirical corrections [13] [18].

Inaccurate Prediction of Magnetic Properties: For systems with complex electronic structures, such as diradicals, the performance of GGA can be inconsistent. Studies on azulene-bridged diradicals show that while local and GGA functionals can correctly predict antiferromagnetic coupling, they often fail to predict ferromagnetic coupling due to the lack of Hartree-Fock exchange [16].

Over-reliance can Hinder High-Accuracy Studies: In pharmaceutical formulation design, while GGA is useful for initial screening, its limitations in describing weak interactions and reaction barriers mean that higher-level methods (e.g., hybrid functionals or double hybrids) are often necessary for reliable thermodynamic parameter prediction, such as binding free energies (ΔG) [15].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Benchmarking on the GMTKN55 Database

The GMTKN55 database, developed by Grimme and colleagues, is the gold standard for assessing the general accuracy of DFT methods in main-group chemistry [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Dataset Acquisition: The GMTKN55 database comprises 55 subsets with 1505 reference energy points, including fundamental properties like atomization energies, reaction energies and barrier heights, and non-covalent interactions [21].

- Computational Settings:

- Software: Standard quantum chemistry packages like Gaussian [18], Q-Chem [13], or ADF [3] are used.

- Basis Set: A large, triple-zeta basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) is typically employed to minimize basis set error [16].

- Integration Grid: Use of a fine integration grid (e.g., "UltraFine" in Gaussian) is critical for numerical accuracy in DFT calculations [18].

- Dispersion Correction: Apply a consistent, modern dispersion correction (e.g., D3(BJ)) to all functionals, as pure GGA lacks this physics [13] [18].

- Error Calculation: For each of the 55 subsets, the mean absolute deviation (MAD) is calculated. These are then combined into a single metric, the weighted total mean absolute deviation (WTMAD-2), which accounts for the different energy scales of the various chemical problems [21].

Figure 2: Workflow for GMTKN55 Benchmarking. This protocol standardizes the evaluation of DFT functionals across a diverse set of chemical problems [21].

Protocol 2: Band Gap Calculation for Semiconductors

Accurately predicting band gaps is a key challenge where GGA's limitations are most apparent.

Detailed Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a set of semiconducting or insulating materials with well-established experimental band gaps ((E_{g}^{EXP})) [20].

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the crystal structure of each material using a GGA functional (e.g., PBE) to ensure consistent and relaxed geometries [20].

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Perform a single-point electronic structure calculation on the optimized geometry using:

- The GGA functional (e.g., PBE) to obtain (E{g}^{GGA}).

- A higher-level method, such as a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06) to obtain (E{g}^{HSE}), for comparison [20].

- Band Gap Extraction: Determine the band gap from the calculated electronic band structure as the difference between the valence band maximum and the conduction band minimum.

- Error Analysis: Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) and mean signed error (MSE) for (E{g}^{GGA}) and (E{g}^{HSE}) against the experimental data. This quantitatively demonstrates GGA's systematic underestimation (negative MSE) and the improvement offered by hybrid functionals [20].

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Resources for DFT Research

| Tool/Resource | Function/Description | Relevance to GGA & Beyond |

|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | ||

| Gaussian [18] | General-purpose quantum chemistry software. | Wide support for GGA, hybrid, and double-hybrid functionals. |

| Q-Chem [13] | Comprehensive quantum chemistry package. | Extensive library of functionals across Jacob's Ladder. |

| ADF [3] | DFT-specific software for molecules and materials. | Supports LDA, GGA, meta-GGA, hybrid, and double-hybrid. |

| Benchmark Databases | ||

| GMTKN55 [21] | Database of 1505 reference energies for main-group chemistry. | Essential for validating and comparing functional accuracy. |

| Materials Project [20] | Database of computed material properties (e.g., band gaps). | Allows assessment of functional performance for solids. |

| Key Concepts & Corrections | ||

| Empirical Dispersion [13] [18] | Adds van der Waals interactions (e.g., Grimme's D3). | Critical add-on for GGA to describe non-covalent forces. |

| Integration Grid [18] | Numerical grid for evaluating the XC functional. | "UltraFine" grid is default for accuracy in production calculations. |

| Basis Set [15] | Set of functions to represent molecular orbitals. | Triple-zeta quality (e.g., def2-TZVP) recommended for benchmarks. |

GGA functionals represent a pivotal step in the evolution of DFT, successfully addressing many of the deficiencies of LDA and establishing a favorable balance between computational cost and accuracy for routine studies. Their ability to model molecular geometries and hydrogen bonding makes them a viable tool for initial screening and studies of large systems where higher-level calculations are prohibitive [19] [15].

However, objective benchmarking reveals clear limitations: GGA systematically underestimates band gaps, poorly describes dispersion forces and certain magnetic phenomena, and is consistently less accurate than modern hybrid and meta-GGA functionals for thermochemical properties [20] [21] [16]. For research requiring high predictive accuracy—such as drug design, catalysis, and advanced materials development—the use of hybrid meta-GGAs, double hybrids, or even the emerging paradigm of functional ensembles (e.g., DENS24) is increasingly necessary [21] [15].

The future of functional development and application lies in the intelligent selection and combination of methods. GGA will remain a foundational tool, but researchers must be aware of its limitations and be prepared to employ more advanced, and computationally expensive, functionals to achieve chemically accurate results for challenging problems.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the predominant quantum mechanical framework for molecular and materials simulations, accounting for the overwhelming majority of all quantum chemistry calculations due to its proven chemical accuracy at relatively low computational expense [22]. The fundamental challenge in DFT lies in approximating the exchange-correlation functional, which represents the quantum mechanical effects not captured by the classical electrostatic and kinetic energy terms [23]. Within this challenge exists a fundamental division between pure density functionals, which depend only on the electron density and its derivatives, and hybrid functionals, which integrate exact Hartree-Fock exchange with density-dependent approximations [24].

The integration of exact exchange represents a pivotal development in functional design, first proposed in the early 1990s and revolutionizing the application of DFT to chemical systems [25]. This integration addresses a fundamental limitation of pure density functionals: the self-interaction error, where electrons incorrectly interact with themselves [23]. By blending the exact, non-local exchange from Hartree-Fock theory with approximate DFT exchange, hybrid functionals provide a more physically realistic description of electron behavior, particularly in systems where electron localization is important [24] [25].

This guide examines the theoretical foundation, performance characteristics, and practical applications of hybrid density functionals in comparison to gradient-corrected alternatives, providing researchers with evidence-based recommendations for functional selection across diverse chemical systems.

Theoretical Foundation and Functional Classification

The Kohn-Sham Formalism and Exchange-Correlation Hole

In the Kohn-Sham DFT framework, the ground state electronic energy is expressed as:

[ E{\text{electronic}} = T{\text{non-int.}} + E{\text{estat}} + E{\text{xc}} ]

where (T{\text{non-int.}}) represents the kinetic energy of a fictitious non-interacting system, (E{\text{estat}}) encompasses electrostatic interactions, and (E{\text{xc}}) is the exchange-correlation energy that captures all quantum mechanical effects [23]. The exact form of (E{\text{xc}}) remains unknown, and its approximation constitutes the central challenge in DFT development.

The exchange-correlation energy can be understood in terms of the exchange-correlation hole, a conceptual region around each electron where the probability of finding another electron is reduced [26]. Accurate functionals must satisfy numerous physical constraints, including proper scaling properties, sum rules for the exchange-correlation hole, correct asymptotic behavior, and recovery of the uniform electron gas limit [26]. The asymptotic behavior is particularly important, as the exact exchange-correlation potential should decay as (-1/r) far from the nucleus, a condition that many approximate functionals fail to satisfy [26].

Jacob's Ladder: A Classification Scheme

Density functionals are commonly classified using "Jacob's Ladder," a conceptual hierarchy introduced by John Perdew that organizes functionals by their theoretical sophistication and accuracy [22]:

Table: Jacob's Ladder Classification of Density Functionals

| Rung | Functional Type | Key Ingredients | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Spin Density Approximation (LSDA) | Local density ρ | SVWN, VWN5 |

| 2 | Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | ρ, ∇ρ | BLYP, PBE, BP86 |

| 3 | Meta-GGA | ρ, ∇ρ, τ | TPSS, SCAN, M06-L |

| 4 | Hybrid | ρ, ∇ρ, τ, exact exchange | B3LYP, PBE0, SOGGA11-X |

| 5 | Double Hybrid | ρ, ∇ρ, τ, exact exchange, virtual orbitals | B2PLYP, DSD-BLYP |

This ladder represents increasing theoretical complexity, with each rung incorporating additional physical information to improve accuracy [22]. Hybrid functionals occupy the crucial fourth rung, introducing exact exchange to improve performance for molecular properties.

The Hybrid Functional Formalism

Hybrid functionals mix a percentage of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange. The general formula for global hybrids can be represented as [24]:

[ E{\text{xc}} = a{\text{x}}E{\text{x}}^{\text{HF}} + (1-a{\text{x}})E{\text{x}}^{\text{DFT}} + E{\text{c}}^{\text{DFT}} ]

where (a_{\text{x}}) represents the fraction of Hartree-Fock exchange. For example, the popular B3LYP functional uses the specific formulation [24]:

[ E{\text{xc}} = 0.2E{\text{x}}^{\text{HF}} + 0.8E{\text{x}}^{\text{LSDA}} + 0.72\Delta E{\text{x}}^{\text{B88}} + 0.81E{\text{c}}^{\text{LYP}} + 0.19E{\text{c}}^{\text{VWN}} ]

The Hartree-Fock exchange energy is calculated using the occupied Kohn-Sham orbitals, providing an exact treatment of the Fermi hole and eliminating self-interaction error [25]. This integration significantly improves the description of molecular systems where electron localization is important, such as in transition states, radicals, and systems with stretched bonds.

Diagram: Evolutionary progression of density functional approximations along Jacob's Ladder, highlighting the key advancement of incorporating exact exchange at the hybrid functional level.

Comparative Performance Analysis

General Main-Group Thermochemistry and Kinetics

For general main-group chemistry, hybrid functionals typically outperform their pure DFT counterparts. The development of SOGGA11-X exemplifies the advantages of hybrid construction, showing better overall performance for a broad chemical database than any previously available global hybrid GGA [25]. This functional satisfies an extra physical constraint by being correct to second order in the density-gradient expansion while incorporating 40.15% Hartree-Fock exchange [25].

Table: Performance Comparison of Selected Functionals on GMTKN55 Database

| Functional | Type | % HF Exchange | WTMAD-2 (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DENS24 ensemble | Ensemble | Variable | 1.62 |

| DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ) | Double Hybrid | Partial | 3.08 |

| SOGGA11-X | Hybrid GGA | 40.15 | ~4.0 (estimated) |

| B3LYP | Hybrid GGA | 20 | ~8.0 (estimated) |

| PBE | GGA | 0 | ~12.0 (estimated) |

| BP86 | GGA | 0 | ~14.0 (estimated) |

Recent research demonstrates that ensembles of density functionals (DENS24) can achieve record-low weighted errors of 1.62 kcal/mol on the GMTKN55 benchmark, significantly outperforming even the best individual functionals [21]. This ensemble approach combines predictions from multiple density functionals using machine learning techniques to generate more robust and accurate predictive models [21].

Transition Metal Complexes and Challenging Systems

For transition metal systems, particularly challenging cases like metalloporphyrins, the performance trends differ notably from main-group chemistry. A comprehensive assessment of 240 density functional approximations for iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins revealed that current approximations fail to achieve "chemical accuracy" of 1.0 kcal/mol by a considerable margin [27].

In these systems, semilocal functionals and global hybrids with low percentages of exact exchange generally perform better than high-exchange hybrids [27]. Functionals with high percentages of exact exchange, including range-separated and double hybrids, can lead to catastrophic failures for spin state energies and binding properties [27]. The best-performing functionals for porphyrin chemistry include GAM (a meta-GGA), revM06-L, M06-L, MN15-L, r2SCAN, and r2SCANh, with mean unsigned errors around 15.0 kcal/mol [27].

For magnetic exchange coupling constants of di-nuclear first-row transition metal complexes, range-separated hybrid functionals with moderately less Hartree-Fock exchange in the short-range and no Hartree-Fock exchange in the long-range perform better than functionals with higher exact exchange percentages [9].

Non-Covalent Interactions and Dispersion Effects

Non-covalent interactions present particular challenges for density functionals. GGAs and meta-GGAs often require empirical dispersion corrections to properly describe van der Waals interactions. The MCML functional, a machine-learned meta-GGA, shows significantly improved performance for surface chemistry, providing the lowest mean absolute error for both chemisorption- and physisorption-dominated binding energies to transition metal surfaces [23].

Hybrid functionals like SOGGA11-X demonstrate improved performance for noncovalent complexation energies compared to their pure DFT counterparts, though careful parameterization is essential [25]. For systems where dispersion forces are crucial, the VCML-rVV10 functional, which simultaneously optimizes semi-local exchange and a non-local van der Waals part, shows improved description of dispersion energetics [23].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Databases and Protocols

Reliable assessment of functional performance requires standardized databases and protocols. The GMTKN55 database, encompassing 1505 reference energies for reactions and barrier heights in main-group and organic chemistry, has become the gold standard for functional evaluation [21]. This database includes 55 subsets categorized into five groups representing various chemical reaction types: fundamental properties, reactions and isomerizations involving larger systems, barrier heights, and inter- and intramolecular noncovalent interactions [21].

The figure of merit in GMTKN55 benchmarks is the weighted total mean absolute deviation-2 (WTMAD-2), which accounts for different scales of various reaction energy types [21]:

[ \text{WTMAD-2} = \frac{1}{\sum{i}^{55}Ni} \sum{i}^{55} \frac{Ni}{56.84\ \text{kcal/mol}/|\Delta E|i} \cdot \text{MAD}i ]

For transition metal systems, specialized databases like Por21 provide reference data for spin states and binding properties of metalloporphyrins, with reference energies obtained from high-level CASPT2 calculations [27].

Computational Implementation Details

Accurate benchmarking requires careful attention to computational details. Key considerations include:

Integration grids: For hybrid functional calculations, the ultrafine (99,590) Lebedev grid is generally recommended, though a fine (75,302) grid often provides sufficient convergence and numerical stability for most applications [25].

Basis sets: Appropriate polarized triple-zeta basis sets (e.g., def2-TZVP) are typically employed for benchmarking studies to minimize basis set superposition errors [27].

Dispersion corrections: Empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., D3, D4) are commonly added to account for missing van der Waals interactions in pure and hybrid functionals [3].

Stability analysis: Wave function stability checks should be performed, particularly for systems with possible multireference character, using keywords like STABLE=OPT in Gaussian implementations [25].

Diagram: Standardized benchmarking workflow for evaluating density functional performance, highlighting key stages from database selection to statistical validation.

Table: Essential Resources for Hybrid Functional Calculations

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software Package | Provides DFT implementation and hybrid functionals | Q-Chem, Gaussian, ADF, ORCA |

| Standard Databases | Benchmark Data | Validation and parameterization | GMTKN55, Por21, BC317 |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical Basis | Expands molecular orbitals | def2-TZVP, 6-311+G(d,p), cc-pVTZ |

| Dispersion Corrections | Empirical Additions | Account for van der Waals interactions | D3(BJ), D4, dDsC, VV10 |

| Integration Grids | Numerical Integration | Integrate exchange-correlation potential | (75,302), (99,590) Lebedev grids |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Surface Chemistry and Catalysis

In surface chemistry, accurately modeling adsorption energies is crucial for catalyst design. The MCML meta-GGA functional demonstrates exceptional performance for both chemisorption and physisorption energies on transition metal surfaces, achieving mean absolute errors below 0.2 eV compared to experimental benchmarks [23]. For the interaction of graphene with Ni(111), the VCML-rVV10 functional shows excellent agreement with experimental estimates for the chemisorption minimum while correctly describing long-range van der Waals behavior [23].

Hybrid functionals generally provide improved descriptions of surface reactions compared to pure GGAs. For D₂ sticking probabilities on Cu(111), the MS-B86bl meta-GGA shows particularly good agreement with experiment, significantly outperforming standard GGAs like PBE and RPBE [23].

Organometallic and Bioinorganic Chemistry

Transition metal complexes, particularly metalloporphyrins, represent particularly challenging cases for DFT. The best-performing functionals for these systems include both meta-GGAs (GAM, M06-L, revM06-L) and hybrids with low exact exchange (r2SCANh, B98, O3LYP) [27]. These functionals achieve mean unsigned errors of approximately 15.0 kcal/mol for the Por21 database, roughly half the error of mediocre performers but still far from chemical accuracy [27].

For magnetic properties of transition metal complexes, range-separated hybrids with specific attenuation parameters provide the best balance for calculating magnetic exchange coupling constants [9]. The Scuseria functionals with moderately less Hartree-Fock exchange in the short-range and no exact exchange in the long-range perform particularly well for these challenging electronic properties [9].

Reaction Kinetics and Barrier Heights

Reaction barrier heights represent one of the most significant advantages of hybrid functionals over pure DFT approximations. The development of specialized hybrids like MPW1K, which uses 42.8% Hartree-Fock exchange, demonstrates the importance of exact exchange for kinetic applications [24]. This functional was specifically optimized for reaction and activation energies of free radical reactions, showing significant improvements over standard hybrids like B3LYP [24].

The SOGGA11-X functional provides excellent across-the-board performance for both thermochemistry and kinetics, achieving good accuracy for hydrogen transfer barrier heights (HTBH38/08) and non-hydrogen transfer barrier heights (NHTBH38/08) while maintaining high accuracy for main-group thermochemistry [25].

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

Machine-Learned Functionals and Uncertainty Quantification

Machine learning techniques are increasingly employed to develop next-generation exchange-correlation functionals [23]. The MCML and VCML-rVV10 functionals demonstrate how machine learning can optimize functional forms against higher-level theory data and experimental benchmarks simultaneously [23]. These approaches also enable uncertainty quantification through Bayesian ensemble methods, providing error estimates for computed energy differences [23].

Challenges remain in developing functionals that perform well for both molecular systems and extended solids. The DM21 functional, trained on quantum chemistry molecular data, shows limitations for solid-state applications like band structure predictions for silicon [23]. However, the modified DM21mu functional, which incorporates the homogeneous electron gas as a physical constraint, demonstrates reasonable band gaps and improved performance for extended systems [23].

Ensemble Approaches and Multi-Functional Strategies

The DENS24 ensemble approach represents a paradigm shift in functional development, combining predictions from multiple density functionals to achieve accuracy superior to any individual constituent functional [21]. This approach acknowledges that no single functional may be optimal for all chemical systems and instead leverages the complementary strengths of multiple functionals [21].

Ensemble methods can be implemented in two ways: (1) combining final properties calculated independently by individual functionals, or (2) creating mixed exchange-correlation functionals inspired by earlier works mixing up to two functionals [21]. The linear regression approach used in DENS24 ensures size-consistency and straightforward calculation of energy derivatives for geometry optimizations and molecular dynamics [21].

Range Separation and Beyond-Hybrid Approaches

Range-separated hybrids (RSH) represent a sophisticated evolution beyond global hybrids, splitting the exact exchange contribution into short-range and long-range components [22]. The general RSH formula can be expressed as:

[ E{\text{xc}}^{\text{RSH}} = E{\text{x}}^{\text{DFT,SR}} + E{\text{x}}^{\text{HF,LR}} + E{\text{c}}^{\text{DFT}} ]

where the range separation is typically accomplished using the error function: (1/r = \text{erf}(\omega r)/r + \text{erfc}(\omega r)/r) [22]. The parameter (\omega) controls the range separation, with small values (0.2-0.3 bohr) being most common in semi-empirical RSH functionals [22].

Double hybrid functionals, occupying the fifth rung of Jacob's Ladder, incorporate both exact exchange and perturbative correlation, providing higher accuracy at increased computational cost [22]. The basic form of a double hybrid can be expressed as [22]:

[ E{\text{xc}}^{\text{DH}} = a{\text{x}}E{\text{x}}^{\text{HF}} + (1-a{\text{x}})E{\text{x}}^{\text{DFT}} + (1-a{\text{c}})E{\text{c}}^{\text{DFT}} + a{\text{c}}E_{\text{c}}^{\text{PT2}} ]

where PT2 represents second-order perturbation theory contributions calculated using virtual orbitals [22].

The integration of exact Hartree-Fock exchange into density functional approximations represents a crucial advancement in DFT development. Based on comprehensive benchmarking studies, we provide the following evidence-based recommendations:

For general main-group thermochemistry and kinetics: Global hybrid GGAs like SOGGA11-X and B3LYP provide good performance, with modern parameterizations generally outperforming older functionals. For highest accuracy, consider ensemble approaches like DENS24.

For transition metal systems and spin state energies: Semilocal functionals and global hybrids with low percentages of exact exchange (e.g., r2SCANh, GAM, M06-L) generally perform better than high-exchange hybrids, which can lead to catastrophic failures.

For non-covalent interactions and surface chemistry: Meta-GGAs with machine-learned parameters (MCML, VCML-rVV10) or empirically dispersion-corrected hybrids provide the best balance for both chemisorption and physisorption energies.

For magnetic properties and transition metal complexes: Range-separated hybrids with moderate short-range exact exchange and no long-range exact exchange (Scuseria functionals) perform well for magnetic exchange coupling constants.

The optimal choice of functional ultimately depends on the specific chemical system and properties of interest. Researchers should consider the theoretical foundation, benchmarking performance for similar systems, and computational cost when selecting functionals for their applications. As functional development continues, machine-learned and ensemble approaches show particular promise for achieving unprecedented accuracy across diverse chemical spaces.

Density functional theory (DFT) has become a cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the study of electronic structures in molecules and materials. The accuracy of DFT calculations critically depends on the exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which approximates the complex quantum mechanical effects not captured by the basic theory. The development of XC functionals has evolved through several generations, from the Local Density Approximation (LDA) to Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), and subsequently to the more sophisticated meta-Generalized Gradient Approximation (meta-GGA) and hybrid functionals. This progression represents a continuous effort to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy, particularly for challenging applications in drug discovery and materials science.

Meta-GGA functionals occupy a crucial position in this hierarchy, offering improved accuracy over GGAs without the computational cost of hybrid functionals. Their development and application are particularly relevant for modeling complex molecular systems where electronic structure details and reaction mechanism insights are paramount. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of meta-GGA functionals against other functional classes, focusing on their theoretical foundation, performance metrics, and practical applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

Theoretical Foundation: What Makes Meta-GGA Unique

Key Differentiators and Computational Formalism

Meta-GGA functionals represent a significant advancement beyond GGA by incorporating additional physical variables into the exchange-correlation functional. While GGA functionals depend on the electron density (ρ) and its gradient (∇ρ), meta-GGAs introduce the kinetic energy density (τ) or the Laplacian of the electron density (∇²ρ) as additional variables [17] [28]. This fundamental extension provides a more sophisticated mathematical framework for describing electron correlation effects.

The kinetic energy density is defined as: [ τ(𝐫) = \frac{1}{2} ∑{i} |∇ψi(𝐫)|^2 ] where ψ_i are the Kohn-Sham orbitals. This quantity provides crucial information about the local behavior of electrons, including their rate of change across space, which significantly improves the functional's ability to describe different chemical environments [17].

The inclusion of these additional variables allows meta-GGA functionals to achieve better compliance with numerous physical constraints and exact conditions that are challenging for simpler functionals. This theoretical improvement translates to practical advantages in predicting molecular properties, reaction energies, and electronic structures with higher fidelity [17] [28].

The Functional Hierarchy in Density Functional Theory

The relationship between different classes of density functionals can be visualized as a progressive incorporation of physical variables, each adding complexity and potentially improving accuracy:

Performance Comparison: Meta-GGA vs. Other Functionals

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Chemical Properties

Extensive benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of meta-GGA functionals against other functional classes across various chemical properties. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for representative functionals from different categories:

Table 1: Benchmarking Accuracy of DFT Functional Classes for Molecular Properties

| Functional | Functional Type | Atomization Energies | Reaction Barrier Heights | Non-covalent Interactions | Electronic Properties | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | GGA | Moderate | Moderate | Poor | Moderate | Low |

| SCAN | Meta-GGA | Good | Good | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Good | Good | Good | Good | High |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | Good | Good | Good | Good | Very High |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | Good | Good | Moderate | Good | High |

Meta-GGA functionals typically demonstrate improved accuracy over GGAs for predicting atomization energies, reaction barrier heights, and electronic properties such as band gaps [17] [29]. For example, the SCAN (Strongly Constrained and Appropriately Normed) functional has shown particular promise in accurately describing both molecules and solids, addressing a limitation that plagues many GGAs and hybrid functionals [17].

Performance in Specific Chemical Applications

Table 2: Functional Performance in Specific Chemical Applications

| Application Domain | Recommended Meta-GGA | Key Advantage | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Geometry Optimization | SCAN, TPSS | Accurate bond lengths and angles | Outperforms GGA, comparable to hybrids [17] |

| Reaction Mechanism Studies | SCAN, M06-L | Improved barrier heights | Superior to GGA, competitive with hybrids [17] [29] |

| Electronic Excitations (TD-DFT) | TPSS, τHCTH | Accurate excitation energies | Comparable to PBE0 hybrid for anions [30] |

| Catalytic Systems | SCAN, BEEF-vdW | Surface and adsorbate energies | Models RPA closely for hydrocarbon systems [29] |

| Transition Metal Complexes | TPSS, M06-L | Description of metal-ligand bonding | Addresses overbinding issues of LDA [31] |

For excitation energy calculations of anionic drug molecules, meta-GGA functionals like TPSS and τHCTH have demonstrated performance comparable to the hybrid functional PBE0, with mean absolute errors of approximately 0.225 eV and 0.23 eV, respectively [30]. This makes them valuable tools for studying the photochemical properties of pharmaceutical compounds in their deprotonated forms, which is relevant for understanding their stability and light-induced degradation pathways.

Experimental Protocols: Methodology for Functional Assessment

Standard Benchmarking Workflow

The assessment of density functional performance follows established computational protocols that systematically evaluate accuracy across diverse chemical systems. The typical workflow involves:

The assessment of density functionals for predicting excitation energies of anionic pharmaceuticals follows a specific protocol [30]:

Conformational Sampling: Explore the conformational space using molecular mechanics approaches (e.g., MMFF94 force field) to identify low-energy conformers.

Geometry Optimization: Re-optimize the most stable conformers in solution using the target density functionals (e.g., PBE0, TPSS, τHCTH) with appropriate basis sets and solvation models.

Solvation Treatment: Employ implicit solvation models (e.g., COSMO, SMD) to account for solvent effects, crucial for accurately modeling anionic species.

Boltzmann Averaging: Calculate Boltzmann-population averaged excitation energies at room temperature (298 K) based on the relative energies of different tautomers and conformers.

Experimental Validation: Compare computed excitation energies with experimental UV-Vis absorption data to determine mean signed errors (MSE), mean absolute errors (MAE), and root mean square (RMS) deviations.

This protocol ensures a comprehensive assessment of functional performance that accounts for the complexities of anionic drug molecules in biologically relevant environments.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

COVID-19 Antiviral Drug Research

Meta-GGA functionals have played significant roles in the molecular modeling of SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Specifically, they have been applied to study the main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) - two crucial viral targets [28]. For these systems, meta-GGAs provide a balanced approach for studying enzyme catalytic mechanisms and inhibitor binding interactions at electronic structure level detail, which is essential for understanding the fundamental chemical processes involved in viral replication and inhibition.

The ability of meta-GGAs to accurately describe reaction pathways and transition states makes them particularly valuable for investigating the covalent inhibition mechanisms of drugs targeting the cysteine-histidine catalytic dyad in Mpro. These studies provide insights that complement molecular mechanics approaches, which cannot adequately describe bond formation and cleavage processes [28].

Pharmaceutical Formulation Design

In pharmaceutical development, meta-GGA functionals contribute to the molecular engineering of drug formulations by [15]:

Elucidating API-Excipient Interactions: Providing insights into the electronic driving forces governing active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)-excipient co-crystallization through Fukui function analysis and molecular electrostatic potential mapping.

Optimizing Nanocarrier Systems: Enabling precise calculation of van der Waals interactions and π-π stacking energies to engineer drug delivery vehicles with tailored surface properties.

Predicting Solid-State Properties: Accurately describing the electronic structure of molecular crystals to predict stability, solubility, and bioavailability of pharmaceutical formulations.

The application of meta-GGAs in these areas helps reduce experimental validation cycles by providing reliable theoretical guidance at the molecular design stage, ultimately accelerating the development of effective drug products.

Practical Implementation Considerations

The Researcher's Toolkit for Meta-GGA Calculations

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Meta-GGA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Role in Meta-GGA Calculations | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Psi4, Q-Chem, Gaussian, ORCA | Provide computational engines for SCF calculations | Check functional availability and implementation efficiency |

| Atomic Orbital Basis Sets | def2-TZVP, 6-311+G(d,p), NAOs | Expand molecular orbitals as linear combinations | Ensure sufficient flexibility for accurate τ representation |

| Solvation Models | COSMO, SMD, PCM | Account for solvent effects on electronic structure | Particularly important for pharmaceutical applications |

| Dispersion Corrections | D3, D4, vdW-surf | Add missing non-covalent interactions | Often necessary for complete physical description |

| Pseudopotentials/PAWs | GTH, SG15, PAW datasets | Replace core electrons in heavy elements | Ensure compatibility with meta-GGA functionals |

Numerical Stability and Basis Set Requirements

The implementation of meta-GGA functionals presents specific computational challenges that researchers must address:

Integration Grid Quality: Meta-GGAs typically require higher-quality integration grids than GGA functionals to achieve numerical convergence, as the kinetic energy density term is more sensitive to grid resolution [17].

Basis Set Truncation Errors: The accuracy of meta-GGA calculations shows strong functional dependence on basis set size, with some functionals exhibiting unusual behavior for specific atomic systems (e.g., Li and Na atoms) [32].

Density Thresholding: Implementing appropriate density thresholds (e.g., screening out densities smaller than 10^(-11) a₀^(-3)) can improve numerical stability without sacrificing accuracy [32].

Self-Consistent Field Convergence: The more complex functional form of meta-GGAs can sometimes lead to SCF convergence difficulties, which may require advanced convergence accelerators or damping techniques.

Emerging computational platforms, such as the Rowan cloud-based quantum chemistry environment, address these challenges by providing robust infrastructure specifically designed for advanced DFT calculations, making meta-GGA simulations more accessible to pharmaceutical researchers [17].

Meta-GGA functionals represent a significant advancement in the hierarchy of exchange-correlation approximations, offering a balanced compromise between computational cost and accuracy for pharmaceutical applications. Their unique incorporation of kinetic energy density enables improved performance for predicting molecular properties, reaction mechanisms, and electronic structures compared to GGA functionals, while remaining less computationally demanding than hybrid approaches.

The continuing development of meta-GGA functionals, coupled with advances in computational infrastructure and integration with machine learning approaches, promises to further expand their role in drug discovery and development. As these functionals become more sophisticated and numerically robust, they are poised to make increasingly significant contributions to the molecular-level understanding of pharmaceutical systems, ultimately accelerating the design of more effective therapeutics.

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Selecting Functionals for Molecular Geometry Optimization and Energetics

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as a cornerstone of modern computational quantum chemistry, offering a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for predicting molecular properties. The core challenge in DFT lies in selecting the appropriate exchange-correlation (XC) functional, which encapsulates all quantum many-body effects. The scientific community is broadly divided between two principal approaches: gradient-corrected functionals (also known as Generalized Gradient Approximation, GGA) and hybrid functionals, which incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange. GGA functionals, which depend on the electron density and its gradient, are often praised for their computational efficiency and reliability for geometry optimizations. In contrast, hybrid functionals, which blend GGA exchange with exact Hartree-Fock exchange, are frequently championed for their superior accuracy in predicting electronic properties and reaction energies, albeit at a significantly higher computational cost. This guide provides an objective comparison of these functional classes, drawing on current research and benchmark studies to inform researchers in fields ranging from materials science to drug development.

The fundamental distinction arises from their treatment of exchange energy. "Pure" density functionals suffer from self-interaction error (SIE) and incorrect asymptotic behavior, leading to systematic underestimation of HOMO-LUMO gaps. Hybrid functionals mitigate this by combining DFT exchange, which performs well for short-range interactions, with Hartree-Fock exchange, which correctly describes long-range behavior, thus achieving beneficial error cancellation [33].

Theoretical Framework and Functional Evolution

The "Jacob's Ladder" of Density Functionals

DFT functionals are often conceptualized as existing on a hierarchy of accuracy and complexity, known as "Jacob's Ladder". The foundational Rung 1 is the Local Density Approximation (LDA), which models the XC energy at each point in space as that of a homogeneous electron gas with the same density. LDA tends to overbind, predicting bond lengths that are too short [33]. Ascending to Rung 2, the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) introduces a dependence on the gradient of the density (∇ρ), leading to improved geometries. Popular GGA functionals include PBE and BLYP [3] [33].

Rung 3 introduces meta-GGA (mGGA) functionals, which additionally depend on the kinetic energy density (τ) or the Laplacian of the density (∇²ρ). This allows for more accurate descriptions of energetics, with prominent examples being TPSS and SCAN [34] [33]. The transition to Rung 4 marks the arrival of hybrid functionals, which mix in a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange. Global hybrids like B3LYP and PBE0 apply a constant HF exchange fraction, while Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH) like CAM-B3LYP and ωB97X use a distance-dependent mixing to better handle charge-transfer and excited states [33]. The pinnacle, Rung 5, is occupied by double-hybrid functionals, which incorporate both HF exchange and a perturbative correlation contribution, such as in the PBE-DH-INVEST functionals [35].

Computational Workflow for Functional Assessment

The following diagram illustrates a standardized computational workflow for benchmarking the performance of different density functionals, as employed in high-throughput studies and detailed benchmark papers.

Performance Comparison of Density Functionals

Quantitative Benchmarking for Key Properties

The selection of a functional must be guided by its demonstrated performance for specific properties. The table below summarizes benchmark data for geometry optimization, energetics, and non-covalent interactions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Select Density Functionals

| Functional | Type | Formation Energy MAE (eV/atom) | Band Gap MAE (eV) | Hydrogen Bonding Energy MAE (kcal/mol) | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBEsol | GGA | Benchmark [36] | 1.35 (Binary Solids) [36] | Not Benchmarked | Low | Geometry Optimization [36] |

| PBE | GGA | Not Benchmarked | Not Benchmarked | Moderate to High [37] | Low | General Solid-State Physics |

| HSE06 | Hybrid | -0.15 vs PBEsol [36] | 0.62 (Binary Solids) [36] | Not Benchmarked | High | Electronic Properties, Oxides [36] |

| B3LYP | Hybrid | Not Benchmarked | Not Benchmarked | Moderate [37] | High | Molecular Thermochemistry |

| B97M-V | mGGA | Not Benchmarked | Not Benchmarked | ~0.3 (Top Performer) [37] | Moderate | Non-Covalent Interactions [37] |

| PBE0 | Hybrid | Not Benchmarked | Not Benchmarked | Low [37] | High | General Purpose Hybrid |

| SCAN | mGGA | Not Benchmarked | Not Benchmarked | Low [37] | Moderate | Solid-State Energetics [36] |

Analysis of Comparative Data

Geometry Optimization: GGA functionals, particularly PBEsol, are often the workhorses for geometry optimization. PBEsol is a GGA functional designed for solids, providing an accurate estimation of lattice constants. High-throughput studies often employ a workflow where structures are first optimized with PBEsol, followed by single-point energy calculations with a more accurate hybrid functional like HSE06 to obtain electronic properties [36]. This combination leverages the geometric accuracy of GGA with the superior energetics of hybrids.

Formation Energies and Thermodynamic Stability: The choice of functional significantly impacts predicted thermodynamic stability. When comparing the GGA functional PBEsol to the hybrid HSE06, a systematic shift is observed: HSE06 typically provides lower formation energies [36]. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) between these functionals can be around 0.15 eV/atom. This discrepancy directly alters convex hull phase diagrams. For instance, in the Li-Al system, the compound Li₂Al is predicted to be stable by PBEsol but is slightly unstable (by 4 meV/atom) according to HSE06 [36]. This level of accuracy is critical for predicting the stability of new materials.

Electronic Properties (Band Gaps): The improvement offered by hybrid functionals is most dramatic for electronic properties. GGAs like PBEsol are notorious for underestimating band gaps. As shown in Table 1, the mean absolute error (MAE) for PBEsol on binary solids is 1.35 eV. Hybrid functionals like HSE06 correct this underestimation, reducing the MAE by over 50% to 0.62 eV [36]. In some cases, the difference is even more pronounced, with PBEsol predicting a metal while HSE06 correctly identifies a semiconductor with a band gap ≥ 0.5 eV [36].