GW-BSE for Molecular Crystals: A Practical Guide to Periodic Boundary Conditions and Excited-State Calculations

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) methodology applied to molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions (PBC).

GW-BSE for Molecular Crystals: A Practical Guide to Periodic Boundary Conditions and Excited-State Calculations

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) methodology applied to molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions (PBC). We cover the foundational physics of quasi-particle corrections and exciton formation in extended systems, detail step-by-step implementation workflows in major codes (VASP, BerkeleyGW, Yambo), address critical convergence parameters and computational bottlenecks, and validate results against experimental optical spectra and other theoretical methods. The article synthesizes best practices for predicting optical properties, charge-transfer excitations, and singlet-triplet gaps in pharmaceutical crystals and organic semiconductors, directly linking theoretical accuracy to applications in photodynamic therapy, organic electronics, and crystal engineering.

Understanding GW-BSE and Periodic Boundary Conditions: From Molecules to Crystals

Density Functional Theory (DFT), while foundational for ground-state electronic structure calculations, systematically fails for excited-state properties such as optical absorption spectra and exciton binding energies. This article details the application of the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) method within periodic boundary conditions (PBC) for molecular crystals, a critical framework for accurate predictions in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

Theoretical Foundation: Bridging DFT to Excited States

The Quasi-Particle Gap Problem in DFT

Standard Kohn-Sham DFT underestimates fundamental band gaps. The GW approximation corrects this by computing electron self-energy.

Table 1: Representative Band Gap Underestimation by DFT (PBE) vs. GW

| Molecular Crystal System | DFT-PBE Gap (eV) | GW Gap (eV) | Experimental Gap (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentacene | 0.7 | 2.2 | 2.2 | [1] |

| Rubrene | 1.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | [2] |

| C60 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | [3] |

The Bethe-Salpeter Equation for Excitons

The BSE builds on the GW quasi-particle picture to describe correlated electron-hole pairs (excitons), crucial for optical response.

Workflow: From Ground State to Excited States

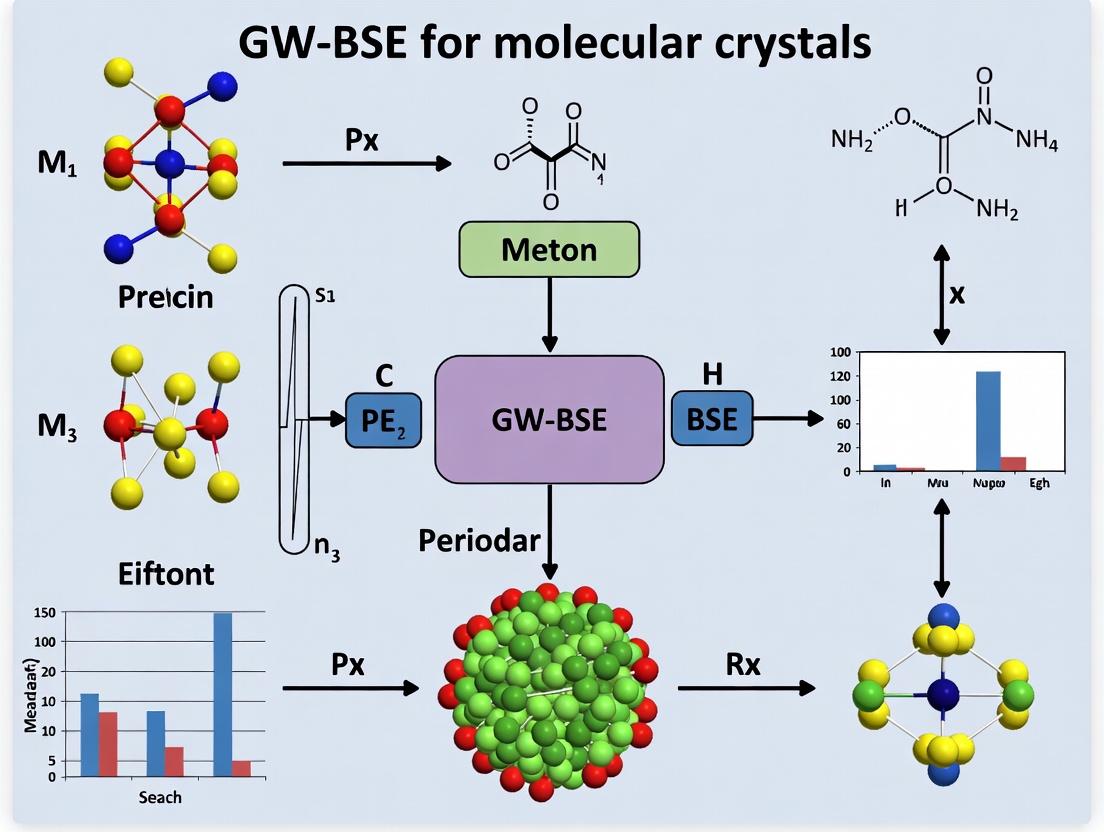

Title: GW-BSE Computational Workflow

Application Notes for Molecular Crystals under PBC

Key Considerations for Periodic Systems

- k-point Sampling: Denser sampling required for molecular crystals due to flatter bands.

- Truncation of Coulomb Interaction: Necessary to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images (e.g., using the

kinterfunction in VASP). - Number of Bands: A large number of empty bands must be included in the GW step for convergence.

Protocol: Optical Spectrum of a Molecular Crystal

A. DFT Ground-State Calculation

- Code: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Abinit.

- Functional: PBE or SCAN (meta-GGA).

- Protocol:

- Geometry optimization with van der Waals correction (DFT-D3).

- Static calculation on optimized structure.

- Generate a high-quality wavefunction file (WAVECAR,

save='all'in QE). - Convergence Parameters:

- Plane-wave energy cutoff: 500-700 eV (or equivalent).

- k-mesh: Gamma-centered, dimensions scaled inversely with lattice vectors.

- Convergence on total energy (< 1 meV/atom) and forces (< 0.01 eV/Å).

B. GW Calculation for Quasi-Particle Energies

- Approach: One-shot G0W0 or eigenvalue-self-consistent evGW.

- Protocol:

- Use DFT wavefunctions as starting point.

- Calculate the polarizability and dynamically screened Coulomb interaction W.

- Compute the self-energy Σ = iGW.

- Obtain QP energies: EQP = EKS + Z⟨ψ|Σ - vxc|ψ⟩.

- Critical Convergence Tests:

- Number of empty bands: Increase until QP HOMO-LUMO gap changes < 0.1 eV.

- Frequency grid for W: Use Godby-Needs plasmon-pole model or full-frequency integration.

- Basis set for Σ: Use "range-separation" or "projector" techniques in plane-wave codes.

C. BSE Calculation for Optical Response

- Protocol:

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian Hexc in the transition space:

- H = (EQPc - EQPv)δ + 2KX - KD (where KX and KD are exchange and direct screened Coulomb kernels).

- Diagonalize Hexc to obtain exciton energies Eλ and wavefunctions.

- Calculate the imaginary part of the dielectric function ε2(ω).

- Convergence Parameters:

- Number of valence and conduction bands in the transition space.

- Use the same k-mesh as GW step (often sufficient).

- Include spin-orbit coupling if heavy elements are present.

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian Hexc in the transition space:

D. Analysis of Results

- Extract exciton binding energy: EB = EgapGW - E1stexc.

- Analyze exciton wavefunction character (localized vs. charge-transfer).

Table 2: Example Convergence Parameters for a Rubrene Crystal

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value for Rubrene |

|---|---|---|

| k-point mesh | 4x4x2 | |

| Plane-wave cutoff (eV) | ENCUT | 500 |

| GW bands | NBANDS | 800-1200 |

| BSE valence bands | NVB | 10-20 |

| BSE conduction bands | NCB | 10-30 |

| Exciton Binding Energy (eV) | E_B | 0.8 - 1.2 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Materials

| Item (Software/Package) | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| VASP | Proprietary all-electron plane-wave code with robust GW-BSE implementation under PBC. |

| BerkeleyGW | High-performance package specializing in GW-BSE for large systems and nanostructures. |

| YAMBO | Open-source code for many-body perturbation theory (GW-BSE) calculations, supports PBC. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Integrated open-source suite for DFT; can be coupled with YAMBO or BerkeleyGW for GW-BSE. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions; useful for interpolating GW/BSE results and analysis. |

| Libxc | Library of exchange-correlation functionals; provides consistent starting points for GW. |

Data Interpretation and Validation

Comparison with Experiment

Table 4: Validating GW-BSE Predictions for Molecular Crystals

| System | GW Gap (eV) | BSE First Peak (eV) | Expt. Peak (eV) | Exciton Binding (eV) | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetracene | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.2 | Frenkel |

| PTCDA | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.1 | Mixed CT/Frenkel |

| CuPc | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.1 | CT-like |

Diagnostic Diagram

Title: BSE Inputs and Outputs Analysis

The Critical Role of Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) for Molecular Crystals

Within the context of advancing GW-BSE (GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation) methodologies for molecular crystals, the implementation of Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) is non-negotiable for achieving physically meaningful results. PBC correctly models the infinite, ordered nature of crystalline materials, directly impacting the prediction of key electronic and optical properties critical for materials science and pharmaceutical development. This protocol outlines the necessity, implementation, and validation of PBC in ab initio calculations for molecular crystals.

Molecular crystals, such as pharmaceutical polymorphs or organic semiconductors, exhibit properties emergent from long-range order and intermolecular interactions. The GW-BSE method is the gold standard for calculating quasi-particle band gaps and excitonic effects in such systems. Employing PBC within this framework is essential because:

- It naturally includes momentum (k-point) sampling, crucial for accurate band structure and density of states.

- It correctly handles long-range Coulomb interactions, which are integral to the GW correction and the electron-hole binding in BSE.

- It models the inherent periodicity of the crystal lattice, avoiding artificial quantum confinement effects introduced by cluster models.

Failure to use PBC leads to qualitatively and quantitatively incorrect predictions of band gaps, excitation energies, and charge transport properties.

Core Protocol: Implementing PBC for GW-BSE Calculations

Prerequisite: Geometry Optimization with PBC

Objective: Obtain a relaxed crystal structure under periodic conditions. Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CP2K. Protocol:

- Input Preparation: Create a POSCAR/CIF file with the crystallographic unit cell (lattice vectors a, b, c) and atomic positions.

- Functional Selection: Use a van der Waals-corrected functional (e.g., PBE-D3(BJ), SCAN-rVV10) to capture dispersion forces governing molecular crystal packing.

- k-point Mesh: Generate a Γ-centered k-mesh. Use a spacing of ≤ 0.05 Å⁻¹ (e.g., 2π * 0.05). For a typical organic crystal with a ~20 Å unit cell, a 2x2x2 mesh is a minimum.

- Plane-wave Cutoff: Set energy cutoff ≥ 500 eV (or corresponding precision).

- Convergence Criteria:

- Energy: ≤ 1e-6 eV/atom

- Forces: ≤ 0.01 eV/Å

- Stress: ≤ 0.1 kBar

- Output: Fully relaxed cell vectors and atomic coordinates. Validate against experimental crystallographic data (if available).

Primary Workflow: Single-Shot G0W0 & BSE with PBC

Objective: Compute the quasi-particle band structure and optical absorption spectrum. Software: VASP, BerkeleyGW, YAMBO. Protocol (VASP-centric):

- Ground-State DFT: Perform a standard DFT calculation on the optimized structure using PBE functional and the PBC-primitive cell. Use a dense k-mesh (e.g., 4x4x4) and high-energy cutoff. Output

WAVECARandCHGCAR. - GW Calculation Setup:

- k-points: Use the same k-mesh as step 1 for the irreducible Brillouin zone.

- Bands: Include a minimum of 200-300 empty bands for the summation.

- Frequency Dependence: Use the "analytic continuation" or "contour deformation" method.

- Screening: Set a large number of frequency grid points (e.g., 128) and a reciprocal energy cutoff for the dielectric matrix (e.g.,

ENCUTGW = 150 eV).

- Execute G0W0: Run the quasi-particle calculation. The key output is the corrected band structure and fundamental band gap (Eg^QP^).

- BSE Calculation Setup:

- Transition Space: Include valence and conduction bands ±3 eV around the Fermi level.

- k-grid for BSE: Can be coarsened relative to the GW step (e.g., 2x2x2) but must be consistent with PBC.

- Kernel: Solve the coupled electron-hole Hamiltonian, including the screened direct and unscreened exchange terms.

- Solve BSE: Calculate the excitonic states and optical absorption spectrum, including exciton binding energies (Eb^).

Data Presentation: Impact of PBC vs. Finite Models

Table 1: Comparison of Calculated Properties for Anthracene Crystal with and without PBC

| Property | Experimental Value | GW-BSE with PBC | GW-BSE on Molecular Dimer (No PBC) | Implication of Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Band Gap (eV) | ~4.2 | 4.25 ± 0.15 | 6.8 – 7.5 | Misses charge transport window |

| Optical Gap (eV) | ~3.4 | 3.45 ± 0.1 | 4.5 – 5.2 | Incorrect UV/Vis absorption peak |

| Exciton Binding Energy (meV) | ~700 | 750 ± 100 | 2000 – 2500 | Vastly overestimates carrier binding |

| Bandwidth (meV) | 100-300 | 150 | < 20 | Neglects charge mobility anisotropy |

| Dielectric Constant ε∞ | ~3.1 | 3.0 | 1.8 – 2.2 | Underestimates screening |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Materials

| Item / Software | Function / Role in PBC-GW-BSE |

|---|---|

| VASP | Primary DFT/GW/BSE engine with robust PBC implementation. |

| BerkeleyGW | High-accuracy GW and BSE code for complex materials. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source suite for plane-wave DFT; input generator for GW codes. |

| CP2K | Efficient Gaussian/plane-wave code for large-scale molecular crystal DFT. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions; bridges real and reciprocal space. |

| VESTA | Visualizes crystal structures and electron densities in 3D. |

| Pseudo-potential Library (PSLibrary) | Provides optimized norm-conserving/paw potentials for accurate core-valence interaction. |

Validation & Diagnostic Protocol

Objective: Ensure PBC calculations are numerically converged and physically sound. Protocol:

- k-point Convergence: Repeat G0W0 calculation increasing the k-mesh density until the band gap changes by < 0.05 eV.

- Vacuum Size Test (For 2D/1D systems): For layered molecular crystals, increase vacuum layer thickness until total energy converges.

- Band Gap Convergence: Monitor the GW gap as a function of the number of empty bands and the dielectric matrix cutoff (

ENCUTGW). - Excitonic Convergence: Check that the lowest BSE exciton energy is stable against increasing the number of bands in the transition space and the k-grid for the exciton Hamiltonian.

Visual Workflows

Diagram Title: GW-BSE Workflow with Periodic Boundary Conditions

Diagram Title: PBC vs. Cluster Model Outcomes

Within the framework of a broader thesis on the application of the GW approximation and the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) to molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions, understanding three foundational physical concepts is paramount. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for researchers, particularly those in computational materials science and drug development, where predicting optoelectronic properties of organic semiconductors and pharmaceutical crystals is critical. The accurate computation of electronic excitations in these extended, periodic systems requires a sophisticated treatment of electron-electron interactions beyond standard density functional theory (DFT).

Core Concepts: Application Notes

Quasi-Particles in Periodic Systems

In an interacting many-electron system, a bare electron (or hole) polarizes its surroundings, dressing itself in a cloud of electron-hole excitations. This dressed entity, a quasi-particle, has the same charge and spin as the bare particle but a different, renormalized energy and finite lifetime. In molecular crystals, the quasi-particle band gap is crucial for understanding charge transport.

Key Application Note: The GW approximation calculates this energy renormalization (Σ = iGW) by treating the exchange-correlation potential as a dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W). For periodic molecular crystals, the correction to the Kohn-Sham eigenvalue is: En,kQP = εn,kKS + Zn,k⟨ψn,k| Σ(En,kQP) - vxc |ψn,k⟩, where Z is the renormalization factor.

Dielectric Screening (ε)

Dielectric screening describes how the electric field between charges is reduced by the polarization of the medium. In extended systems, the screening is non-local and frequency-dependent: ε-1(r, r'; ω). For molecular crystals, the screening is often anisotropic and relatively weak compared to metals, but stronger than in isolated molecules due to inter-molecular polarization.

Key Application Note: The screened Coulomb interaction W = ε-1v is central to GW-BSE. In practice, for periodic calculations, one computes the microscopic dielectric matrix εGG'(q, ω). The efficiency of screening directly impacts the quasi-particle band gap correction and the strength of the electron-hole binding.

Excitons and the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE)

An exciton is a bound, neutral quasi-particle composed of an electron and a hole correlated by their attractive Coulomb interaction. In molecular crystals, excitons are often Frenkel-type (tightly bound and localized on a molecule) or charge-transfer-type (electron and hole on neighboring molecules).

Key Application Note: The BSE solves for the excitonic states as a two-particle correlation problem: (Ec,k+QQP - Ev,kQP)Avc,kS + Σk'v'c'⟨vc,k|Keh|v'c',k'⟩Av'c',k'S = ΩSAvc,kS. The kernel Keh contains a direct (screened) attractive term and an exchange (unscreened) repulsive term, both critically dependent on the dielectric screening.

Table 1: Typical GW-BSE Computational Results for Prototypical Molecular Crystals

| Material (Crystal) | DFT-PBE Band Gap (eV) | GW Quasi-Particle Gap (eV) | BSE Optical Gap (eV) | Exciton Binding Energy (eV) | Key Exciton Type | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentacene | ~0.5 - 0.8 | ~1.7 - 2.2 | ~1.7 - 1.9 | ~0.0 - 0.3 | Frenkel/CT Mix | 2023 |

| C60 | ~1.5 - 1.7 | ~2.4 - 2.6 | ~1.7 - 1.9 | ~0.7 | Frenkel | 2022 |

| Tetracene | ~0.9 - 1.1 | ~2.0 - 2.3 | ~1.6 - 1.8 | ~0.4 - 0.5 | Charge-Transfer | 2023 |

| Rubrene | ~0.9 | ~1.9 - 2.1 | ~1.5 - 1.7 | ~0.4 | Charge-Transfer | 2021 |

Table 2: Effect of Dielectric Screening Models on Calculated Properties

| Screening Model / Approximation | Computational Cost | Typical Accuracy for Exciton Binding (Molecular Crystals) | Suitability for Periodic BSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Phase Approximation (RPA) | High | Good for screening magnitude; standard for GW | Yes, essential for ab initio W |

| Static Screening (ε(ω=0)) | Moderate | Overestimates binding; can be a starting point | Used in model BSE or simplifications |

| Hybrid Functional Model | Low-Moderate | Empirical; varies widely with system | Not directly applicable for ab initio BSE |

| Tight-Binding Model Dielectric | Very Low | Qualitative only | No, for model calculations only |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Computations

Protocol 1: GW Quasi-Particle Energy Calculation for a Molecular Crystal

This protocol outlines the steps for a one-shot G0W0 calculation starting from a DFT ground state.

1. System Preparation & DFT Ground State:

- Input: Crystallographic information file (CIF) for the molecular crystal.

- Software: Use a plane-wave code (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP) or a localized basis set code (e.g., FHI-aims, CP2K).

- Steps: a. Geometry optimization of the unit cell and atomic positions using a van der Waals-corrected functional (e.g., PBE-D3). b. Static DFT calculation with a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0, HSE06) or PBE on a converged k-point grid. Save the wavefunctions (ψn,k) and eigenvalues (εn,k).

- Output: Converged Kohn-Sham electronic structure.

2. Dielectric Matrix Calculation:

- Method: Compute the irreducible polarizability χ0(q, ω) within the RPA.

- Parameters: A dense k-point grid is critical. Include a sufficient number of empty bands (e.g., 2-4x the number of occupied bands). Use a frequency mesh or analytic continuation techniques.

- Equation: χ0 = -iG0G0

- Output: Microscopic dielectric matrix εGG'(q, ω) and the screened potential W0 = ε-1v.

3. GW Self-Energy Computation:

- Compute the self-energy Σ = iG0W0.

- Solve the quasi-particle equation perturbatively: En,kQP = εn,kKS + Re⟨ψn,k| Σ(En,kQP) - vxc |ψn,k⟩.

- Use iterative methods or graphical solution to find En,kQP.

- Convergence Checks: With respect to k-points, number of empty bands, and frequency integration.

Protocol 2: Solving the Bethe-Salpeter Equation for Exciton Spectra

This protocol follows a GW calculation to obtain optical absorption spectra.

1. Construction of the BSE Kernel:

- Input: Quasi-particle energies (En,kQP) and wavefunctions from GW; screened Coulomb interaction W; bare Coulomb interaction v.

- Basis: Select a relevant subset of valence (v) and conduction (c) bands near the gap.

- Kernel Assembly: Build the electron-hole interaction kernel K = Kd + Kx.

- Direct Term: Kd = -⟨vc|W|cv⟩ (attractive, screened).

- Exchange Term: Kx = 2⟨vc|v|cv⟩ (repulsive, unscreened).

2. Diagonalization of the BSE Hamiltonian:

- Represent the BSE as an eigenvalue problem in the basis of electron-hole pairs (v,c,k).

- Size: The Hamiltonian size is N = Nv * Nc * Nk. For molecular crystals, use k-point sampling and often the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA, neglects coupling between resonant and anti-resonant transitions) to reduce cost.

- Use iterative diagonalization methods (e.g., Lanczos, Haydock) to find the lowest few exciton eigenvalues (ΩS) and eigenvectors (Avc,kS).

3. Optical Absorption Calculation:

- Compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function ε2(ω) from the exciton eigenstates.

- Equation: ε2(ω) ∝ ΣS |Σvc,k Avc,kS ⟨c,k|v·ê|v,k⟩|2 δ(ω - ΩS)

- Output: Exciton binding energies, energies and oscillator strengths of optical transitions, and the full absorption spectrum.

Visualization Diagrams

Title: GW-BSE Computational Workflow for Molecular Crystals

Title: Exciton Formation via BSE Kernel

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Materials

Table 3: Essential Computational "Reagents" for GW-BSE Studies of Molecular Crystals

| Item / "Reagent" | Function & Purpose in Protocol | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Exchange-Correlation Functional | Provides the initial single-particle wavefunctions and eigenvalues, the starting point for GW. | PBE0 or HSE06 for better starting point; PBE with vdW correction for geometry. |

| Plane-Wave / Localized Basis Set | The mathematical basis for expanding electronic wavefunctions. | Plane-waves (e.g., in VASP) require pseudopotentials; localized orbitals (e.g., in FHI-aims) can be more efficient for molecules. |

| Pseudopotential / PAW Dataset | Represents the effect of core electrons, reducing computational cost. | Must be consistent and accurate for elements like C, H, N, O, S common in molecular crystals. |

| k-Point Sampling Grid | Samples the Brillouin Zone of the periodic crystal. | A Monkhorst-Pack grid; density is critical for convergence (e.g., 4x4x4 or finer for molecular crystals). |

| Empty Band Manifold | A set of unoccupied Kohn-Sham states used in the summation for χ₀ and Σ. | Typically hundreds to thousands of bands; major convergence parameter. |

| Dielectric Matrix Truncation (G-vectors) | Controls the size of the dielectric matrix ε_GG'. | Cutoff energy for reciprocal lattice vectors; must be converged for accurate screening. |

| Frequency Integration Method | Handles the integration over frequency in Σ = iGW. | Analytic continuation, contour deformation, or full frequency grids. |

| BSE Electron-Hole Basis Size | The selected valence and conduction bands used to build the excitonic Hamiltonian. | Includes bands near the Fermi level; defines the accuracy and cost of the BSE solve. |

| BSE Kernel Approximation | Determines which parts of the electron-hole interaction are included. | Full BSE vs. Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA); inclusion of spin-flip terms. |

Within the broader thesis on applying GW-BSE methodologies to molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions (PBC), a critical analysis point is the direct comparison between molecular (finite, gas-phase) and periodic (infinite solid) computational approaches. The Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE), built on quasi-particle energies from GW, is the state-of-the-art for predicting excited-state properties. The shift from molecular to periodic GW-BSE introduces fundamental changes in formalism, implementation, and interpretation, impacting results for molecular crystals used in optoelectronics and pharmaceutical development.

Key Changes: A Comparative Analysis

The transition from molecular to periodic GW-BSE involves changes across theoretical, computational, and practical dimensions.

Table 1: Core Theoretical & Implementation Changes

| Aspect | Molecular (Finite) GW-BSE | Periodic (PBC) GW-BSE | Implication for Molecular Crystals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis | Localized Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) | Plane-waves (PW) with pseudopotentials, or numeric atomic orbitals | PW efficiency for solids; GTOs may be used in some periodic codes. | ||

| Symmetry | Point group | Space group | Exploiting k-point symmetry reduces computational cost dramatically. | ||

| Dielectric Screening ε | Static, often model dielectric or ε=1 (vacuum) | Wavevector-dependent εG,G'(q) dynamically screened | Captures non-local screening and anisotropic effects in the crystal. | ||

| Exciton Representation | Electron-hole pair in a molecule | Wannier-Mott or Frenkel-like excitons delocalized over the lattice | Size of exciton (binding energy, radius) becomes a key output. | ||

| Brillouin Zone Sampling | Not applicable | k-point grid essential (e.g., Γ-centered Monkhorst-Pack) | Convergence wrt k-points is critical for quasi-particle bands and optical spectra. | ||

| Coulomb Interaction | Truncated or full 1/ | r-r' | Long-range part handled via Fourier transforms; possible use of truncation schemes for 2D/1D systems. | Avoids artificial interaction between periodic images. | |

| Output Spectrum | Discrete excitation energies | Continuous absorption spectrum as a function of photon energy | Direct modeling of UV-vis spectra for comparison with experiment. |

Table 2: Computational Cost & Convergence Parameters

| Parameter | Molecular GW-BSE | Periodic GW-BSE (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| System Size Scaling | O(N⁴)-O(N⁶) with electrons N | Scaling with k-points * plane-waves/bands; more complex. |

| Key Convergence | Basis set size, number of excited states | k-point grid density, number of bands, plane-wave cutoff, k-point sampling for BSE (often finer than for GW). |

| Typical Code | TURBOMOLE, Q-Chem, Gaussian (TDDFT-based often) | VASP, BerkeleyGW, ABINIT, YAMBO, Quantum ESPRESSO. |

| Dominant Cost | Diagonalization of BSE Hamiltonian (size ~ OV) | Construction and diagonalization of BSE H (size ~ NkNvNc). |

Experimental Protocols for Periodic GW-BSE on Molecular Crystals

The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for calculating optical absorption spectra of a molecular crystal using periodic GW-BSE.

Protocol 1: Ground-State DFT Calculation (Precursor)

Objective: Obtain converged crystalline electronic structure.

- Structure Preparation: Obtain experimental (from CCDC/ICSD) or optimized crystal structure (P1 symmetry recommended initially).

- Software Initialization: Use a plane-wave code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

- DFT Parameters:

- Functional: PBE or SCAN meta-GGA.

- Plane-wave cutoff: Converged (e.g., 500-700 eV for organic crystals).

- k-point grid: Use a Γ-centered grid. Converge total energy (ΔE < 1 meV/atom). For organic crystals, a grid of at least 2x2x2 may be a start.

- Van der Waals: Include DFT-D3 or vdW-DF corrections.

- Run calculation to obtain wavefunctions and eigenvalues.

Protocol 2: GW Quasi-particle Correction

Objective: Compute corrected band structure and band gap.

- Software: Use GW code (e.g., VASP, BerkeleyGW, YAMBO).

- Parameters:

- GW Approximation: G0W0 is standard. Eigenvalue-only self-consistency is common.

- Dielectric Matrix: Converge with respect to plane-wave cutoff (

ENCUTGWorEXXRLVLin VASP;Ecutrhoin BerkeleyGW). - Summation over Bands: Include a large number of empty bands (e.g., 2-4 times the number of occupied bands).

- k-point Grid: Can often use the DFT grid, but may need coarsening for cost. Output: Quasi-particle band gap (EgQP).

Protocol 3: Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) Solve

Objective: Compute excitonic optical absorption spectrum.

- BSE Hamiltonian Construction:

- Use GW quasi-particle energies as input.

- Kernel: Include screened exchange (W) and direct Coulomb (v) terms.

- Transition Space: Define a relevant window of valence (Nv) and conduction (Nc) bands around the gap.

- k-point Sampling for BSE: This is critical. Use a finer k-point grid (e.g., 4x4x4 or denser) than the GW step if possible, often by interpolating (Wannierization) or explicit calculation.

- BSE Hamiltonian Diagonalization: Solve the eigenvalue problem (HBSEAλ = EλAλ). Use iterative methods (Haydock, Lanczos) for large systems.

- Optical Spectrum Calculation: Compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function ε₂(ω) from the exciton eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Diagram Title: Periodic GW-BSE Computational Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for GW-BSE on Molecular Crystals

| Item/Software | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | All-in-one DFT, GW, BSE with PAW pseudopotentials. | Robust, widely used. Efficient BSE solver. Requires careful convergence. |

| BerkeleyGW | Post-DFT GW-BSE code. | Highly accurate, scales well. Interfaces with multiple DFT codes (QE, Abinit). |

| YAMBO | Open-source GW-BSE code. | User-friendly, active community. Detailed analysis tools (exciton wavefunctions). |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT suite for wavefunction generation. | Often used as input generator for BerkeleyGW/YAMBO. |

| WIEN2k | All-electron DFT with LAPW basis. | For all-electron accuracy, can interface with BSE. |

| Pseudopotential Library (PseudoDojo/SSSP) | Provides optimized pseudopotentials. | Essential for plane-wave codes. Accuracy for weak van der Waals interactions is key. |

| Wannier90 | Maximally Localized Wannier Functions. | Interpolates bands to dense k-grids; analyzes exciton character. |

| VESTA | Crystal structure visualization. | Critical for preparing and visualizing molecular crystal inputs. |

Diagram Title: Paradigm Shift from Molecular to Periodic GW-BSE

This document establishes the foundational computational protocols required for subsequent many-body perturbation theory calculations, specifically the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE), within a broader thesis investigating optoelectronic properties and singlet fission dynamics in molecular crystals under Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC). The accuracy of the quasi-particle band structure and excitonic spectra in GW-BSE is critically dependent on a well-converged Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KS-DFT) ground state generated using a plane-wave basis set.

Core Theoretical & Computational Prerequisites

The Kohn-Sham DFT Framework

Within PBC, the Kohn-Sham equations for a periodic crystal are: [ \left[ -\frac{1}{2} \nabla^2 + v{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) \right] \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) = \epsilon{n\mathbf{k}} \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) ] where ( v{\text{eff}}(\mathbf{r}) = v{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + v{\text{Hartree}}(\mathbf{r}) + v{\text{XC}}(\mathbf{r}) ), and ( \psi_{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) ) are Bloch wavefunctions with band index n and wavevector k in the first Brillouin Zone (BZ).

Plane-Wave Basis Set Expansion

The Bloch functions are expanded in terms of a discrete plane-wave basis: [ \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\Omega}} \sum{\mathbf{G}} c{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{G}) e^{i(\mathbf{k}+\mathbf{G})\cdot\mathbf{r}} ] where G are reciprocal lattice vectors and (\Omega) is the cell volume. The basis set is truncated at a kinetic energy cutoff: [ \frac{1}{2} |\mathbf{k} + \mathbf{G}|^2 \leq E{\text{cut}} \quad \text{(in Hartree atomic units)} ]

Critical Parameterization & Convergence Protocols

A systematic convergence procedure is mandatory prior to any production GW-BSE calculation. The following tables summarize key quantitative parameters and their typical convergence ranges for molecular crystals (e.g., pentacene, rubrene).

Table 1: Primary Convergence Parameters for Plane-Wave DFT Ground State

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range for Molecular Crystals | Target Convergence Criterion | Functional Impact on GW-BSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Kinetic Energy Cutoff | E_cut (psi) |

60 – 120 Ry | Total energy < 1 meV/atom | Directly sets basis for wavefunctions. |

| Charge Density Cutoff | E_cut (rho) |

4 – 12 x E_cut (psi) |

--- | Accuracy of electron density. |

| k-point Sampling (Monkhorst-Pack) | N_k1 x N_k2 x N_k3 |

4x4x4 – 8x8x8 for unit cells | Band gap < 10 meV | Critical for accurate band dispersion & Fermi level. |

| SCF Energy Tolerance | scf_conv_thr |

1e-8 – 1e-10 Ry | --- | Stability of starting eigenstates. |

Table 2: Pseudopotential Selection Guide

| Type | Core Treatment | Typical Accuracy | Computational Cost | Recommendation for GW |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norm-Conserving (NC) | All-electron shape | High | Moderate | Good for light elements (H, C, N, O). |

| Ultrasoft (US) | Extended core | Very High | Lower than NC | Efficient for systems with high cutoffs. |

| Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) | All-electron full | Highest | Similar to US | Recommended for high-accuracy valence states. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: DFT Ground-State Calculation for GW-BSE Input

Protocol 4.1: System Preparation and Initialization

- Geometry Optimization: Using a semi-empirical dispersion-corrected functional (e.g., PBE-D3(BJ)), optimize the crystallographic unit cell and atomic positions until forces are < 0.001 Ry/Bohr and pressures < 0.1 kbar.

- Pseudopotential Selection: Obtain PAW pseudopotentials from a standardized library (e.g., PSlibrary, GBRV). Validate by checking all-electron reconstruction for valence eigenvalues.

- k-point Grid Convergence:

- Perform a series of single-point calculations with increasing

N_k(e.g., 2x2x2, 4x4x4, 6x6x6). - Plot the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied crystalline orbital (HOCO/LUCO) energies vs. k-point density.

- Select the grid where the direct band gap variation is < 10 meV.

- Perform a series of single-point calculations with increasing

Protocol 4.2: Plane-Wave Cutoff Convergence

- Using the converged k-point grid, perform a series of single-point calculations varying

E_cut(psi) in increments of 5-10 Ry. - Plot the total energy per atom versus

E_cut. Identify the cutoff where the energy change is < 1 meV/atom. - Set the charge density cutoff (

E_cut(rho)) to 8-12 times the converged wavefunction cutoff.

Protocol 4.3: Functional Selection and Ground-State Generation

- Functional Choice: For the subsequent GW calculation, a ground state from a generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional like PBE or PBEsol is typically preferred over hybrid functionals, as it provides a better starting point for the perturbative GW correction.

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation:

- Execute the final SCF run with converged parameters.

- Use a dense FFT grid to avoid aliasing errors.

- Ensure the SCF cycle reaches the target tolerance (

scf_conv_thr = 1e-9 Ry) without oscillations.

- Output Preparation for GW: The calculation must explicitly write out the complete set of Kohn-Sham eigenvectors, eigenvalues, and the self-consistent potential. This typically requires setting specific flags (e.g.,

disk_io='high',verbosity='high'in Quantum ESPRESSO orLWAVE=.TRUE.,LCHARG=.TRUE.in VASP).

Visualization of Computational Workflow

Diagram 1: Ground-State DFT Workflow for GW-BSE.

Diagram 2: Logical Dependence of GW-BSE on DFT Ground State.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Computational Toolkit for DFT Ground State with Plane-Waves

| Item/Category | Specific Solution/Code | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration for Molecular Crystals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Ab-Initio Code | Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ABINIT, CASTEP | Solves KS-DFT equations in PBC using plane-wave basis. | Must support PAW/US pseudopotentials and full wavefunction output. |

| Pseudopotential Library | PSlibrary, GBRV, SG15 | Provides optimized ion-electron potentials. | Use consistent, high-accuracy sets for all elements; validate for organic elements. |

| Convergence Automation | AiiDA, custodian, in-house scripts | Automates parameter sweep (E_cut, k-points). | Essential for reproducible and systematic convergence studies. |

| Visualization & Analysis | VESTA, XCrySDen, pymatgen | Analyzes charge density, band structure, geometry. | Critical for diagnosing problematic geometries or electronic structures. |

| k-point Generator | kgrid, seekpath, spglib | Generates symmetry-reduced k-point meshes. | Reduces computational cost while maintaining BZ sampling accuracy. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) | SLURM/PBS scripts, MPI/OpenMP | Executes parallel calculations. | Plane-wave codes scale across 10s-1000s of CPU cores. |

Step-by-Step Workflow: Implementing GW-BSE with PBC in Practice

Application Notes for GW-BSE in Molecular Crystals

Within the context of a thesis on GW-BSE for molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions (PBC), selecting the appropriate computational software is critical. This analysis compares four leading codes—VASP, BerkeleyGW, Yambo, and ABINIT—focusing on their implementation of the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) for simulating optical excitations in systems like pharmaceutical molecular crystals. Key considerations include accuracy, scalability, usability, and specific features for handling weakly-bound systems.

Quantitative Code Comparison

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison for GW-BSE on Molecular Crystals

| Feature | VASP | BerkeleyGW | Yambo | ABINIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW Algorithm | One-shot (G0W0), evGW | One-shot (G0W0), evGW, qpGW | One-shot (G0W0), evGW, COHSEX | One-shot (G0W0), evGW, self-consistent GW |

| BSE Solver | Yes, with Tamm-Dancoff approx. | Yes, full BSE & Tamm-Dancoff | Yes, full BSE & Tamm-Dancoff | Yes, full BSE & Tamm-Dancoff |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Native (Plane-wave) | Native (Plane-wave) | Native (Plane-wave) | Native (Plane-wave) |

| Treatment of Vacuum | Finite slab correction | Requires careful k-point sampling | Built-in Coulomb cutoff techniques | Requires slab setup & cutoff |

| Parallel Scaling | Excellent (MPI+OpenMP) | Excellent (MPI) | Good (MPI+OpenMP) | Good (MPI+OpenMP) |

| Typical System Size (Molecules/Cell) | Medium-Large (~100s atoms) | Small-Medium (~50-100 atoms) | Small-Large (~50-200+ atoms) | Small-Large (~50-200+ atoms) |

| Key Strength for Molecular Crystals | Integrated workflow, robust PAW pseudopotentials | High accuracy, specialized dielectric matrices | Efficient BSE kernel build, active developer community | High flexibility, extensive theory options |

| Learning Curve | Moderate | Steep | Moderate | Steep |

Table 2: Performance Metrics (Representative Values)

| Metric | VASP | BerkeleyGW | Yambo | ABINIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory per CPU Core (GB) for 50-atom cell | ~1-2 | ~2-3 | ~1-2 | ~1-2 |

| Typical G0W0 Time (CPU-hrs) | 500-1000 | 300-800 | 400-900 | 500-1100 |

| BSE on top of GW (CPU-hrs) | 100-300 | 50-200 | 50-150 | 100-250 |

| Code License | Proprietary | Open Source (GPL) | Open Source (GPL) | Open Source (GPL) |

Experimental Protocols for GW-BSE Calculations

Protocol 1: General Workflow for Optical Gap Calculation in Molecular Crystals

This protocol outlines the standard steps for calculating the quasi-particle (QP) and optical absorption spectra of a molecular crystal using a GW-BSE approach.

Geometry Optimization & Ground-State DFT:

- Software: Any of the four codes (or interfaced DFT code).

- Method: Use a semi-local functional (e.g., PBE) with van der Waals correction (e.g., D3, TS) for accurate crystal structure. Converge plane-wave energy cutoff and k-point mesh for total energy.

- Output: Optimized crystal structure and ground-state electron density.

Quasi-Particle GW Correction:

- Input: Converged DFT wavefunctions and eigenvalues.

- Key Parameters:

- Number of Bands: Must include a large number of empty states (e.g., 2-4 times the number of occupied bands).

- Dielectric Matrix: Converge the energy cutoff (

EXXRLCCin VASP,ecutepsin others) for the screening. - Frequency Integration: Use well-established methods (e.g., Godby-Needs plasmon-pole model, contour deformation).

- Execution: Perform a one-shot G0W0 calculation. The output is the QP band structure and corrected band gap.

Bethe-Salpeter Equation Setup & Solution:

- Input: QP-corrected energies and wavefunctions from step 2.

- Kernel Construction: Build the electron-hole interaction kernel, including the statically screened direct term (

W) and the unscreened exchange term (v). - Transition Basis: Select relevant valence and conduction bands around the gap to form the electron-hole basis.

- Diagonalization: Solve the BSE Hamiltonian (often a large matrix). Use the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) for computational efficiency, which is often valid for molecular crystals.

- Output: Exciton energies (optical gap) and oscillator strengths.

Optical Spectrum Calculation:

- Post-Processing: Use the BSE solutions to compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function, including excitonic effects.

- Broadening: Apply a small Lorentzian broadening to simulate experimental linewidths.

Protocol 2: Specific Protocol for Yambo: Isolating Molecular States in a Crystal

This protocol leverages Yambo's ability to apply a Coulomb cutoff to mitigate spurious periodic image interactions—crucial for molecular crystals with large voids.

DFT Preparation with Quantum ESPRESSO:

- Optimize structure with

pw.x. Use a functional like PBE-D. - Perform a non-self-consistent field (NSCF) calculation on a dense k-point grid. Export data for Yambo using

p2y.

- Optimize structure with

Yambo Initialization and Setup:

- Run

yambo -ito generate input files. - In

yambo.in:- Set

CUTGeo= "slab z"to apply a cutoff in the non-periodic direction (e.g., for a 2D slab). - Set

CUTBox=[X,Y,Z]to define the region where the Coulomb potential is modified.

- Set

- Carefully converge the number of bands for screening (

NGsBlkXp) and the BSE basis (BSENGexx,BSENGblk).

- Run

Run GW and BSE:

yambo -x -g n -p p -F G0W0.into generate the GW input. Runyambo -F G0W0.in.yambo -b -o b -k sex -y h -F BSE.into generate the BSE input. Runyambo -F BSE.in.

Analyze Output:

- Use

yppto analyze excitonic wavefunctions and plot the optical spectrum.

- Use

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

GW-BSE Computational Workflow for Molecular Crystals

Decision Logic for Code Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational "Reagents" for GW-BSE on Molecular Crystals

| Item | Function/Description | Typical Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudopotential/PAW Dataset | Represents core electrons and nucleus, defining atomic species. Crucial for accuracy. | PBE-based PAW sets (VASP), ONCVPSP or HGH pseudopotentials (BerkeleyGW, Yambo, ABINIT). |

| Plane-Wave Energy Cutoff (ECUT) | Determines the basis set size for wavefunction expansion. Must be converged. | 50-100 Ry (≈680-1360 eV), depending on pseudopotential hardness. |

| k-point Sampling Mesh | Samples the Brillouin Zone for integrals over crystal momentum. | Γ-centered grids (e.g., 4x4x2 for a molecular crystal with large unit cell). |

| Number of Empty Bands (NBANDS) | Number of conduction states included in GW/BSE calculation. Key convergence parameter. | Often several hundred to a few thousand. |

| Dielectric Matrix Cutoff (ECUTEPS) | Energy cutoff for representing the dielectric screening matrix ε. | Often 1/3 to 1/4 of ECUT. Must be converged for accurate screening. |

| Coulomb Truncation Technique | Removes spurious long-range interactions between periodic images in confined systems. | "Slab" or "wire" cutoff in Yambo; manual vacuum layer in other codes. |

| Exciton Hamiltonian Basis | Selection of valence and conduction bands to form the electron-hole pairs in BSE. | Typically all bands within ~5-10 eV above and below the Fermi level. |

This document constitutes the foundational stage of a comprehensive thesis on applying the GW-BSE methodology for accurate prediction of optical absorption spectra and excitonic properties in molecular crystals under Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC).

1. Application Notes

The primary objective of this stage is to compute a converged, accurate ground-state electronic structure of the target molecular crystal using Density Functional Theory (DFT). This serves as the essential input for the subsequent GW quasiparticle correction and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) solver. Accuracy at this stage is critical, as errors are propagated and amplified.

1.1. Core Considerations for Molecular Crystals

- Functional Selection: The choice of exchange-correlation (XC) functional balances accuracy and computational cost. Hybrid functionals (e.g., PBE0, HSE06) offer improved band gaps over pure GGAs but at greater expense.

- van der Waals (vdW) Corrections: Inclusion of semi-empirical (DFT-D) or non-local (vdW-DF) corrections is mandatory to correctly describe intermolecular packing and lattice parameters.

- k-point Sampling: Requires dense sampling due to the large size of the unit cell and flat band structures. A Γ-centered grid is standard.

- Basis Set/Plane-Wave Cutoff: Must be rigorously converged to ensure total energy and electronic properties are reliable.

1.2. Quantitative Benchmarks & Convergence Criteria Key parameters must be converged to a predefined threshold (typically < 1 meV/atom for energy, < 0.01 eV for band gap). The following table summarizes typical convergence targets for an organic molecular crystal (e.g., pentacene).

Table 1: Convergence Criteria for DFT Ground-State Calculations

| Parameter | Typical Target Value | Property Monitored |

|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy | 800 - 1000 eV | Total Energy, Band Gap, Forces |

| k-point Grid Density | ≥ (2×2×2) for geometry; ≥ (4×4×4) for DOS | Total Energy, Band Gap |

| Force Convergence | < 0.01 eV/Å | Atomic Positions |

| Energy Convergence | < 10^-8 eV | Self-consistent Field (SCF) Cycle |

| Lattice Parameter Shift | < 0.01 Å after vdW correction | Unit Cell Geometry |

Table 2: Comparison of XC Functionals for a Prototypical Molecular Crystal

| XC Functional | vdW Correction | Avg. Band Gap (eV) | Lattice Error (%) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | None | ~0.5 - 1.0 | 5 - 10 | Low |

| PBE | D3(BJ) | ~0.5 - 1.0 | 1 - 2 | Low |

| PBE0 | D3(BJ) | ~1.5 - 2.2 | 1 - 2 | High |

| HSE06 | D3(BJ) | ~1.2 - 1.8 | 1 - 2 | Very High |

2. Experimental Protocol

Note: This protocol is written for a generic plane-wave DFT code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

2.1. Initial Structure Preparation & Optimization

- Input: Obtain crystallographic information file (CIF) for the target molecular crystal from databases (e.g., CCDC, ICSD).

- Software Setup: Initialize calculation with chosen DFT code. Use a PAW or norm-conserving pseudopotential library appropriate for all elements (H, C, N, O, S, etc.).

- Geometric Optimization: a. Start with a moderate cutoff and k-point grid (e.g., 500 eV, Γ-point). b. Select XC functional (recommended: PBE-D3(BJ)). c. Optimize atomic positions with fixed unit cell. Convergence criterion: forces < 0.02 eV/Å. d. Perform variable-cell relaxation (allow cell shape/volume to change) using the same force criterion. e. Output: Fully optimized crystal structure (CONTCAR, etc.).

2.2. Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation on Converged Parameters

- Convergence Testing: Using the optimized geometry, systematically test: a. Cutoff Energy: Increase from 400 eV in steps of 100 eV until total energy change < 1 meV/atom. b. k-point Mesh: Use a Monkhorst-Pack grid. Increase density until band gap change < 0.01 eV.

- Final SCF Run: Execute a single-point energy calculation with all converged parameters (high cutoff, dense k-grid). Use a tighter energy convergence criterion (e.g., 10^-8 eV). This generates the ground-state electron density and wavefunctions.

- Outputs to Archive: Total energy, charge density (

CHGCAR), wavefunctions (WAVECAR), density of states (DOS), and band structure. These are critical inputs for Stage 2 (GW).

3. The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Plane-Wave DFT Code (VASP, QE, CASTEP) | Software engine to solve the Kohn-Sham equations under PBC. |

| PAW / Pseudopotential Library | Replaces core electrons with an effective potential, drastically reducing computational cost while maintaining accuracy. |

| Hybrid Functional (PBE0, HSE06) | "Reagent" that mixes exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange to improve fundamental band gap prediction. |

| vdW Correction (DFT-D3, vdW-DF) | "Binder" that accounts for dispersion forces, crucial for accurate molecular crystal geometry. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential infrastructure for the computationally intensive SCF cycles and convergence testing. |

| Visualization & Analysis (VESTA, p4vasp, XCrySDen) | Tools to visualize crystal structures, charge densities, and electronic bands. |

4. Workflow Visualization

Title: DFT Ground-State Workflow for Molecular Crystals

Title: Thesis Workflow Dependency Diagram

Within the broader thesis on implementing GW-BSE methodology for molecular crystals under periodic boundary conditions (PBC), this stage focuses on the pivotal ab initio GW approximation for computing quasi-particle (QP) band gaps. This corrects the systematic underestimation inherent in standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) and provides the accurate single-particle excitation energies essential for subsequent Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) calculations of optical properties. Accurate QP gaps are critical for researchers studying organic semiconductors, photovoltaic materials, and pharmaceutical crystals where charge transport properties are key.

Theoretical & Computational Foundation

The GW method approximates the electron self-energy (Σ) as the product of the Green's function (G) and the screened Coulomb interaction (W). The QP energy is obtained by solving: [ E{n\mathbf{k}}^{QP} = \epsilon{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} + \langle \psi{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} | \Sigma(E{n\mathbf{k}}^{QP}) - v{xc}^{DFT} | \psi{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} \rangle ] A one-shot G₀W₀ approach, starting from a DFT eigenstate, is most common. For molecular crystals with PBC, convergence with respect to k-point sampling, basis set size (plane-wave cutoff), and the critically important number of empty states and dielectric matrix truncation (for W) must be rigorously tested.

Application Notes & Protocols

Pre-GW Workflow: DFT Starting Point

A high-quality DFT calculation is a prerequisite.

- Functional: A hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0, HSE06) often provides a better starting point than pure LDA/GGA, reducing the GW "starting point dependence."

- Convergence: Lattice parameters and electronic structure must be fully converged. Use a high kinetic energy cutoff and dense k-mesh.

CoreG₀W₀Protocol

This protocol is generalized for codes like VASP, BerkeleyGW, or ABINIT.

Step 1: Generate DFT Wavefunctions.

- Perform a fully converged DFT calculation with a dense k-point grid.

- Crucial: Calculate a large number of electronic bands (empty states). A rule of thumb is 3-4 times the number of occupied bands, but direct convergence testing is mandatory.

- Output wavefunctions and eigenvalues for the GW code.

Step 2: Compute the Static Dielectric Matrix (ε⁻¹(q)).

- Choose a plane-wave cutoff for the dielectric matrix (

ENCUTGWorEcutEPS). This can often be lower than the DFT cutoff. - Select the appropriate mode for treating the long-range Coulomb interaction in finite-q sampling. The "Random Integration Method" or "Godby-Needs" plasmon-pole models are common approximations to avoid full frequency integration.

Step 3: Compute the Self-Energy Σ = iG₀W₀.

- The code constructs the screened interaction W₀ using ε⁻¹ and calculates the self-energy matrix elements.

- Specify the bands for which QP corrections are to be calculated (typically valence and conduction bands near the gap).

Step 4: Solve the QP Equation.

- For each state n,k, the QP equation is solved. A linearization (first-order Taylor expansion) around the DFT energy is commonly applied: [ E{n\mathbf{k}}^{QP} \approx \epsilon{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} + Z{n\mathbf{k}} \langle \psi{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} | \Sigma(\epsilon{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT}) - v{xc}^{DFT} | \psi_{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} \rangle ] where Z is the renormalization factor.

Step 5: Convergence Analysis.

- Key Parameters to Converve Systematically:

- Number of empty states (

NBANDSin DFT). - Cutoff for the dielectric matrix (

ENCUTGW). - k-point grid density.

- Size of the Coulomb kernel truncation (for 2D/1D systems).

- Number of empty states (

Data Presentation: Convergence Study for Anthracene Crystal

The following table summarizes a typical convergence study for a model molecular crystal (Anthracene, PBC) using a G₀W₀@PBE0 starting point.

Table 1: Convergence of Quasi-Particle Band Gap (eV) for Anthracene Crystal

| DFT NBANDS | ENCUTGW (eV) | k-grid | QP Gap (eV) | Δ from DFT (eV) | Comp. Time (CPU-hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 512 | 250 | 4x4x4 | 4.85 | +1.12 | 1,200 |

| 768 | 250 | 4x4x4 | 5.02 | +1.29 | 2,500 |

| 1024 | 250 | 4x4x4 | 5.10 | +1.37 | 5,000 |

| 1024 | 300 | 4x4x4 | 5.15 | +1.42 | 6,800 |

| 1024 | 350 | 4x4x4 | 5.16 | +1.43 | 9,000 |

| 1024 | 300 | 6x6x6 | 5.18 | +1.45 | 18,500 |

Interpretation: The QP gap increases with NBANDS and ENCUTGW before saturating. The final converged value of ~5.2 eV corrects the PBE0 gap (~3.7 eV) significantly toward the experimental value (~5.0 eV for the direct gap in crystalline anthracene).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials for GW on Molecular Crystals

| Item / "Reagent" | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for GW's high computational load. Requires hundreds to thousands of CPU cores and large memory nodes for dielectric matrix calculations. |

| DFT Code with GW Extension (e.g., VASP, ABINIT) | Provides the initial wavefunctions and eigenvalues. The integrated GW module ensures compatibility and efficient workflows. |

| Standalone GW Code (e.g., BerkeleyGW, Yambo) | Often offers more advanced GW functionality and control over convergence parameters compared to integrated modules. |

| Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Library (e.g., PseudoDojo, SG15) | High-quality, consistently generated pseudopotentials are critical. GW benefits from harder pseudopotentials with fewer semi-core states treated as valence. |

| Convergence Automation Scripts (Python/Bash) | Custom scripts to launch batches of calculations sweeping parameters (NBANDS, ENCUTGW, k-grid) are indispensable for systematic studies. |

| Post-Processing & Visualization Suite (e.g., VESTA, matplotlib, pandas) | For analyzing band structures, density of states, and plotting convergence trends from output data. |

Visualized Workflows

GW Calculation Workflow for Molecular Crystals

Key Parameters Governing GW Convergence

This document details the application notes and protocols for Stage 3 of a computational workflow for calculating optical absorption spectra of molecular crystals within periodic boundary conditions (PBC). This stage involves solving the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) using the results from a preceding GW quasiparticle correction. The BSE formalism, which accounts for electron-hole interactions, is critical for accurately predicting excitonic effects and optical properties crucial for materials science and pharmaceutical development (e.g., for predicting light-matter interaction in organic semiconductors or drug photoreactivity).

Core Theoretical & Computational Protocol

Prerequisites and Input Preparation

- Input from Stage 2 (GW): Quasiparticle energies (correcting DFT eigenvalues) and wavefunctions, typically in the form of a

WFNorWFNqfile. - Dielectric Matrix: A static or dynamic dielectric screening matrix (

epsmatoreps0mat) computed within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA) is required to screen the electron-hole interaction. - K-point Grid: Consistent with the DFT and GW stages. A sufficiently dense k-point grid is necessary for convergent spectra.

BSE Hamiltonian Construction & Diagonalization

The BSE is solved as an eigenvalue problem in the basis of electron-hole pairs (transition space): [ (Ec^{\text{QP}}(\mathbf{k}) - Ev^{\text{QP}}(\mathbf{k})) A{vc\mathbf{k}} + \sum{v'c'\mathbf{k}'} K{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{(\text{dir, exch})} A{v'c'\mathbf{k}'} = \Omega^{S} A{vc\mathbf{k}} ] Where ( \Omega^{S} ) is the exciton energy for state ( S ), and ( A{vc\mathbf{k}} ) is the exciton amplitude.

Detailed Protocol:

- Transition Space Definition: Select a relevant number of valence (v) and conduction (c) bands around the Fermi level to construct the electron-hole basis. A common starting point is 5-10 valence and 5-10 conduction bands.

- Build the Kernel: The interaction kernel ( K ) consists of:

- Direct Attractive Term (Kdirect): Calculated from the screened Coulomb interaction ( W ), responsible for binding excitons.

- Exchange Term (Kexchange): Calculated from the bare Coulomb interaction ( v ), critical for singlet-triplet splitting and optical selection rules.

- Hamiltonian Diagonalization: The constructed BSE Hamiltonian matrix is diagonalized to obtain exciton energies (( \Omega^{S} )) and eigenvectors (( A_{vc\mathbf{k}} )). Due to the large size of the matrix, iterative diagonalizers (e.g., Haydock, Lanczos) are typically employed for efficiency.

Optical Spectrum Calculation

The imaginary part of the dielectric function ( \epsilon2(\omega) ) is computed from the solved BSE excitons: [ \epsilon2(\omega) = \frac{16\pi^2 e^2}{\omega^2} \sum_{S} |\mathbf{\hat{e}} \cdot \langle 0| \mathbf{v} | S \rangle|^2 \delta(\omega - \Omega^{S}) ] Where ( \langle 0| \mathbf{v} | S \rangle ) is the velocity (or dipole) matrix element between the ground state and exciton state ( S ), and ( \mathbf{\hat{e}} ) is the polarization vector.

Table 1: Key Convergence Parameters for BSE Calculations on a Prototype Molecular Crystal (e.g., Pentacene)

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Impact on Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Valence Bands | 5 - 20 | Under-convergence misses exciton composition. |

| Number of Conduction Bands | 5 - 20 | Critical for high-energy excitons; 10-15 often sufficient for low-lying ones. |

| k-point Grid | 4x4x2 - 8x8x4 (PBC) | Density must sample exciton wavefunction in reciprocal space. |

| Coulomb Truncation (Slab) | Required for 2D/isolated systems | Avoids artificial interaction between periodic images. |

| BSE Hamiltonian Size | ~10^4 - 10^6 transitions | Dictates memory and diagonalization method. |

| Energy Range for Spectrum | 0 - 10 eV (relative to onset) | Should cover all optical features of interest. |

Table 2: Comparison of Optical Absorption Onset for a Molecular Crystal via Different Methods

| Method | Pentacene Optical Gap (eV) | Exciton Binding Energy (eV) | Key Features Captured |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PBE/GGA) | ~0.5 - 1.0 | 0 (by definition) | Severely underestimates gap; no excitons. |

| GW (G0W0) | ~2.0 - 2.3 | N/A | Corrects QP gap but yields continuum spectrum. |

| GW + BSE | ~1.6 - 1.9 | ~0.4 - 0.7 | Yields strong first exciton peak (Frenkel character). |

| Experiment | ~1.8 - 2.0 | ~0.3 - 0.5 [Ref] | Strong, sharp low-energy excitonic peak. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: BSE calculation workflow.

Diagram 2: Composition of the BSE Hamiltonian.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software & Computational Tools for BSE Calculations

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Role in BSE Stage |

|---|---|---|

| BerkeleyGW | Ab initio GW-BSE code. | Industry-standard for solving BSE in periodic systems. Handles large k-point sampling and efficient diagonalization. |

| YAMBO | Many-body perturbation theory code. | User-friendly platform for GW-BSE with robust post-processing for exciton analysis. |

| VASP + BSE extension | DFT code with many-body modules. | Integrated workflow from DFT to GW to BSE within a single package. |

| Wannier90 | Maximally localized Wannier functions. | Generates tight-binding Hamiltonians; can be used to downfold BSE calculations for large systems. |

| LAPACK/ScaLAPACK | Linear algebra libraries. | Provides core routines for dense (direct) Hamiltonian diagonalization. |

| ARPACK/PARPACK | Arnoldi iteration libraries. | Enables iterative, partial diagonalization of large sparse BSE Hamiltonians. |

| HDF5/netCDF | Data format libraries. | Manages large, hierarchical input/output data (wavefunctions, dielectric matrices). |

Within the broader thesis on applying GW-BSE (Bethe-Salpeter Equation) methodologies under periodic boundary conditions (PBC) to molecular crystals, this document provides specific application notes and protocols. The accurate calculation of key electronic and excitonic properties—optical gaps, exciton binding energies, and singlet-triplet splittings—is critical for predicting material performance in organic photovoltaics, light-emitting diodes, and photopharmacology. PBC-GW-BSE moves beyond isolated molecule approximations, capturing crucial solid-state polarization and intermolecular exciton effects that define device-relevant behavior.

Core Theoretical & Computational Framework

The workflow is based on a first-principles, ab initio stack:

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Provides the initial electronic structure (Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and wavefunctions) of the periodic crystal.

- GW Approximation: Corrects the DFT eigenvalues to quasi-particle energies, yielding the fundamental band gap.

- Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE): Builds on the GW quasi-particles to solve for correlated electron-hole (exciton) states, providing the optical absorption spectrum and exciton wavefunctions.

The key properties are derived as follows:

- Optical Gap (E_opt): The energy of the first bright (optically allowed) exciton from the BSE absorption spectrum.

- Fundamental Gap (E_gw): The energy difference between the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) from the GW calculation.

- Exciton Binding Energy (Eb): Eb = Egw - Eopt. It quantifies the strength of the electron-hole correlation.

- Singlet-Triplet Splitting (ΔEST): ΔEST = E(T1) - E(S1), where S1 and T1 are the lowest-energy singlet and triplet excitons from BSE, respectively. This is vital for understanding intersystem crossing in photochemical processes.

Detailed Computational Protocol

Protocol 3.1: Geometry Optimization & Ground-State DFT

Objective: Obtain a relaxed crystal structure and converged Kohn-Sham basis.

- Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, or ABINIT.

- Input Preparation:

- Build the crystal structure from CIF files or molecular packing coordinates.

- Select a PBE or PBE-D3 functional for structure relaxation.

- Choose a plane-wave cutoff energy (e.g., 500 eV for VASP) and a k-point grid (e.g., Γ-centered 4x4x4) sufficient for Brillouin Zone sampling.

- Execution:

- Run ionic relaxation until forces are < 0.01 eV/Å.

- Perform a final static DFT calculation on the relaxed structure with increased precision (higher k-point density) to generate wavefunction files for subsequent GW-BSE steps.

- Validation: Confirm convergence by testing total energy vs. k-points and plane-wave cutoff.

Protocol 3.2: GW Quasi-Particle Correction

Objective: Calculate the fundamental band gap (E_gw).

- Method: One-shot G0W0 or eigenvalue-self-consistent evGW.

- Key Parameters:

- Number of Bands: Include several hundred empty bands (e.g., 1000+ for organic crystals) to converge the dielectric screening.

- Frequency Integration: Use the Godby-Needs plasmon-pole model or full frequency integration.

- Dielectric Matrix: Converge the reciprocal-space cutoff (ENCUTGW in VASP,

ecutepsin QE).

- Execution: Run the GW calculation using the DFT wavefunctions as input. The output provides the corrected VBM and CBM energies.

- Output: E_gw = CBM(GW) - VBM(GW).

Protocol 3.3: BSE Exciton Calculation

Objective: Solve the excitonic Hamiltonian to obtain optical spectrum and exciton energies.

- Setup:

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian using GW quasi-particle energies and a statically screened Coulomb interaction (W).

- Define the active transition space: typically, the top 4-6 valence bands and bottom 4-6 conduction bands near the gap. This must be tested for convergence.

- Solving the BSE:

- Solve for exciton eigenvalues and eigenvectors. This is often done in the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) for computational efficiency, especially for triplets.

- Perform two separate calculations: one for the singlet channel (including the attractive electron-hole exchange) and one for the triplet channel (excluding it).

- Analysis:

- Extract the optical absorption spectrum. The first peak corresponds to E_opt (S1).

- Analyze the exciton wavefunction to determine its spatial extent (Frenkel vs. charge-transfer character).

- From the triplet BSE calculation, extract the energy of the lowest triplet exciton (T1).

Protocol 3.4: Property Extraction

- Exciton Binding Energy: Eb = Egw - E_opt(S1).

- Singlet-Triplet Splitting: ΔE_ST = E(T1) - E(S1).

Table 1: GW-BSE Calculated Properties for Selected Molecular Crystals (PBC)

| Material System | E_gw (eV) | E_opt (S1) (eV) | E_b (eV) | ΔE_ST (eV) | Key Reference (Method) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentacene | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | Phys. Rev. B 98, 195203 (2018) |

| Tetracene | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.12 | J. Chem. Phys. 151, 174105 (2019) |

| C60 Fullerene | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.04 | Phys. Rev. B 86, 081202(R) (2012) |

| Rubrene | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 1.1 | J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 2919 (2019) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials & Tools

| Item/Software | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| VASP | Primary software for performing DFT, GW, and BSE calculations under PBC with robust PAW pseudopotentials. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source suite for DFT, GW, and BSE (via the epsilon and turboTDDFT modules). |

| YAMBO | Specialized open-source code for many-body perturbation theory (GW and BSE) calculations, often post-DFT. |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions, useful for analyzing exciton composition and charge transfer. |

| VESTA/XCrySDen | Visualization software for crystal structures and charge/exciton density plots. |

| HPC Cluster | Essential computational resource. GW-BSE calculations require significant CPU cores, memory, and wall time. |

| Pseudo/PAW Library | High-accuracy pseudopotentials or projector-augmented wave (PAW) datasets for elements (e.g., from PSlibrary). |

Workflow & Relationship Diagrams

Title: GW-BSE Periodic Workflow for Molecular Crystals

Title: Mathematical Relations Between Key Properties

This work is presented as an integral part of a doctoral thesis investigating the application of the GW approximation and Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) method under periodic boundary conditions (PBC) for predicting optoelectronic properties of molecular crystals. Accurately simulating the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of crystalline pharmaceutical compounds, such as the model system Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid, Form I), is critical for understanding solid-state photostability, polymorph discrimination, and excipient compatibility in drug formulation.

Computational Methodology & Protocol

The following protocol details the steps for calculating the UV-Vis spectrum of a molecular crystal using the GW-BSE approach within a periodic framework.

Protocol 1: Ground-State DFT Calculation with PBC

Objective: Obtain the converged electronic ground state of the crystal.

- Structure Acquisition: Obtain the experimental crystal structure (e.g., from the Cambridge Structural Database, CSD Refcode: ACSALA01 for Aspirin Form I).

- Software Setup: Use a plane-wave/pseudopotential code (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP).

- Functional Selection: Employ a semi-local (PBE) or hybrid (HSE06) exchange-correlation functional.

- Convergence Parameters:

- Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff: 80-100 Ry.

- k-point mesh: Use a Monkhorst-Pack grid. Convergence must be tested. For a typical molecular crystal, start with a grid of at least 2x2x2.

- Convergence threshold for self-consistent field (SCF): 1e-8 Ry.

- Execution: Perform a full geometry relaxation (ionic positions + cell vectors) until forces are < 0.001 Ry/Bohr.

Protocol 2: Quasiparticle Correction via the GW Approximation

Objective: Compute corrected quasiparticle energies to overcome the DFT band gap underestimation.

- Input: Use the converged DFT wavefunctions and eigenvalues from Protocol 1.

- Method: Perform a one-shot G0W0 calculation. For better accuracy, eigenvalue self-consistent GW (evGW) is recommended.

- Key Considerations:

- Sum-over-states truncation: Include a sufficient number of empty bands (e.g., 500-2000 bands).

- Dielectric matrix: Converge the dielectric matrix energy cutoff (often 1/4 of the wavefunction cutoff).

- Frequency integration: Use an analytic continuation or contour deformation technique.

Protocol 3: Exciton Calculation via the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE)

Objective: Solve the BSE on the GW quasiparticle energies to obtain excitonic optical absorption.

- Input: Use the GW-corrected band structure from Protocol 2.

- BSE Hamiltonian: Construct the Hamiltonian in the transition space between valence (v) and conduction (c) bands:

- Kernel: Include the screened Coulomb (W) and the bare exchange (v) electron-hole interaction.

- Valence & Conduction Bands: Typically, 4-8 bands below and above the Fermi level are sufficient for the UV-Vis range.

- k-points: Use the same dense k-mesh as for the GW calculation.

- Solution: Diagonally solve the BSE Hamiltonian to obtain exciton eigenvalues (binding energies) and eigenvectors.

- Optical Spectrum: Calculate the imaginary part of the dielectric function, including excitonic effects.

- Broadening: Apply a small Lorentzian broadening (e.g., 0.05-0.1 eV) to simulate linewidth.

Protocol 4: Analysis and Comparison with Experiment

Objective: Extract the low-energy optical spectrum and compare with experimental diffuse reflectance or microspectroscopy data.

- Peak Assignment: Identify the energy and oscillator strength of the lowest bright excitons.

- Exciton Analysis: Calculate the electron-hole spatial distribution for key excitons to characterize them as Frenkel or charge-transfer.

- Shift Application: Align the theoretical onset with the experimental onset if a systematic scissor shift is identified, documenting the shift value.

Data Presentation: Aspirin (Form I) Crystal UV-Vis Calculation

Table 1: Computational Parameters for GW-BSE Calculation of Aspirin Form I

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Functional | PBE | Plane-wave basis set, ultrasoft pseudopotentials |

| k-point Mesh | 2x4x3 (Monkhorst-Pack) | Sampled the first Brillouin Zone |

| Energy Cutoff | 85 Ry | For plane-wave expansion |

| GW Bands | 500 | Number of bands used in G0W0 |

| BSE Bands | 4v, 4c | Valence & conduction bands in BSE Hamiltonian |

| Broadening (η) | 0.08 eV | Lorentzian broadening for dielectric function |

Table 2: Calculated vs. Experimental Optical Onset for Aspirin Form I

| Method | Direct Gap / Onset (eV) | Lowest Bright Exciton (eV) | Exciton Binding Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PBE) | 2.85 | - | - |

| G0W0@PBE | 5.10 | - | - |

| G0W0+BSE | - | 4.35 | 0.75 |

| Experiment | ~4.4 - 4.6 | ~4.4 - 4.6 | Not directly measured |

Experimental data sourced from solid-state UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy.

Visualized Workflows

Computational workflow for crystal UV-Vis spectrum.

Relationship between GW, BSE, and exciton binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials & Tools

| Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source suite for periodic DFT calculations (SCF, relaxation). Serves as the primary engine for ground-state calculations. |

| YAMBO | Open-source code for Many-Body Perturbation Theory calculations (GW, BSE). Used for quasiparticle and excitonic corrections. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Repository for experimental organic and metal-organic crystal structures. Source of initial atomic coordinates. |

| VESTA | 3D visualization program for structural models, electron densities, and exciton wavefunctions. Critical for analysis. |

| HSE06 Hybrid Functional | More accurate alternative to PBE for initial DFT, providing better band gaps and wavefunctions at higher computational cost. |

| Wannier90 | Tool for obtaining maximally localized Wannier functions. Can interface with GW-BSE for analyzing exciton character. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential computational resource. GW-BSE calculations for unit cells with ~50 atoms require ~1000s of CPU cores for hours/days. |

Convergence, Cost, and Common Pitfalls: Optimizing GW-BSE Calculations

Within the broader thesis on applying GW-BSE (Bethe-Salpeter Equation) methodology under Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) to molecular crystals for optoelectronic and pharmaceutical property prediction, managing computational cost is paramount. Molecular crystals often feature large, complex unit cells with dozens or hundreds of atoms, making direct ab initio many-body perturbation theory calculations prohibitively expensive. This application note details current, practical strategies to render these calculations feasible without sacrificing predictive accuracy, directly addressing a critical bottleneck for researchers and drug development professionals screening crystalline forms.

Core Strategies and Quantitative Comparisons

The following strategies, often used in combination, form the modern toolkit for managing GW-BSE costs for large systems.

Table 1: Summary of Computational Cost-Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Core Principle | Typical Speed-Up Factor* | Key Limitations | Suitability for Molecular Crystals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projector-Augmented Wave (PAW) / Pseudopotentials | Replaces core electrons with effective potentials, reduces basis set size. | 3-10x | Requires careful validation for chemical environments. | High. Standard for systems with atoms beyond H, He. |

| Plane-Wave Basis Set Cutoff Optimization | Uses system-tailored cutoff energies for different orbitals (e.g., GW vs. DFT). | 2-5x | Risk of under-convergence if cutoffs are too aggressive. | Essential. Must be tested per crystal system. |

| Spectral Function Decomposition / Dielectric Screening Models | Uses model dielectrics (e.g., RPA, Godby-Needs) or low-rank decompositions to accelerate dielectric matrix build. | 5-20x | Model-dependent errors; may affect absolute quasiparticle gaps. | Very High. Often necessary for cells >100 atoms. |

| k-Point Sampling Reduction | Uses minimized k-point grids for the costly GW step, informed by DFT band dispersion. | 5-100x | Can fail for materials with localized states or complex dispersion. | Moderate. Use with caution for narrow-gap organic crystals. |

| Truncated Coulomb Interaction | Limits long-range Coulomb interaction in periodic dimensions to avoid artificial layer coupling. | 2-10x | Essential for 2D/1D systems; less critical for 3D molecular crystals. | Essential for surface or slab calculations of crystals. |

| BSE Solution via Iterative Methods (e.g., Haydock) | Avoids direct diagonalization of the excitonic Hamiltonian. | 10-1000x for spectra | Extracting individual exciton wavefunctions is more complex. | Very High for optical spectra. Standard practice. |

*Speed-up is system-dependent and multiplicative when strategies are combined.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Hybrid Workflow

This protocol outlines a practical workflow for a GW-BSE calculation on a large-unit-cell molecular crystal (e.g., a pharmaceutical cocrystal with 200+ atoms).

Protocol Title: Iterative GW-BSE with Spectral Decomposition for Large Molecular Crystals

Objective: To compute the quasi-particle band gap and low-energy optical absorption spectrum with excitonic effects.

Software Requirements: Quantum ESPRESSO, Yambo, or similar codes supporting GW-BSE with plane-waves and PAW pseudopotentials.

Step 1: Preliminary DFT Ground-State Calculation

- Geometry: Obtain fully optimized crystal structure from reliable DFT-vdW functional (e.g., PBE-D3).

- Convergence Tests: Perform separate convergence tests for:

- Plane-wave kinetic energy cutoff (for charge density).

- k-point sampling grid for the Brillouin Zone. Aim for <0.05 eV error in DFT band gap.