Mastering Geometry Optimization Convergence: A Practical Guide for Computational Chemists and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to geometry optimization convergence criteria in computational chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mastering Geometry Optimization Convergence: A Practical Guide for Computational Chemists and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to geometry optimization convergence criteria in computational chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of energy, gradient, and step convergence criteria, explores their implementation across major software packages and modern neural network potentials, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for stubborn optimization failures. The guide also details validation protocols to ensure optimized structures represent true minima and includes comparative benchmarks of popular optimizers, empowering scientists to achieve reliable and efficient results in their molecular modeling workflows.

Understanding the Core Principles: What Are Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria?

In computational chemistry, geometry optimization is the process of iteratively adjusting a molecule's nuclear coordinates to locate a local minimum on the potential energy surface (PES). A converged optimization signifies that the structure has reached a stationary point characterized by balanced forces and minimal energy, providing a reliable geometry for subsequent analysis. This application note details the fundamental principles, quantitative convergence criteria, and practical protocols for achieving robust geometry convergence, with specific emphasis on applications in drug development and molecular research.

The Potential Energy Surface and Optimization Fundamentals

Understanding the Potential Energy Surface

The Potential Energy Surface (PES) describes the energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates [1]. Under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates electronic and nuclear motion, the PES allows for the exploration of molecular geometry and reaction pathways [2] [3].

- Energy Landscape: The PES can be visualized as a multidimensional landscape where energy corresponds to height and geometrical parameters (e.g., bond lengths, angles) define the terrain [1]. A molecule with N atoms has 3N-6 internal degrees of freedom (3N-5 for linear molecules), resulting in a complex, multidimensional surface [2].

- Stationary Points: Key features on the PES include local minima (stable molecular configurations) and saddle points (transition states between minima) [1] [2]. A local minimum, the target of geometry optimization, is characterized by positive curvature in all directions, while a first-order saddle point (transition state) has negative curvature in exactly one direction along the reaction coordinate [2] [3].

The Goal of Geometry Optimization

Geometry optimization is an iterative algorithm that "moves downhill" on the PES from an initial guessed structure toward the nearest local minimum [4]. The optimization is considered converged when the structure satisfies specific numerical criteria, confirming it has reached a stationary point [4] [5]. A converged result ensures that the geometry resides in a low-energy, stable configuration, which is critical for calculating accurate molecular properties, predicting spectroscopic data, and rational drug design [5].

Quantitative Convergence Criteria

Convergence in geometry optimization is typically determined by simultaneously satisfying multiple thresholds related to energy changes, forces (gradients), and structural steps [4]. The following tables summarize standard criteria.

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization

| Criterion | Physical Meaning | Common Default Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | Change in total energy between optimization cycles | 1 × 10⁻⁵ [4] | Hartree |

| Maximum Gradient | Largest force on any nucleus | 1 × 10⁻³ [4] | Hartree/Bohr |

| RMS Gradient | Root-mean-square of all nuclear forces | 6.67 × 10⁻⁴ [4] | Hartree/Bohr |

| Maximum Step | Largest displacement of any nucleus between cycles | 0.01 [4] | Angstrom |

| RMS Step | Root-mean-square of all nuclear displacements | 6.67 × 10⁻³ [4] | Angstrom |

Table 2: Predefined Convergence Quality Settings in AMS [4]

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 |

Implementation Note: Most quantum chemistry packages like PySCF (using geomeTRIC or PyBerny optimizers) use similar, slightly different default values (e.g., convergence_gmax ≈ 4.5×10⁻⁴ Ha/Bohr) [6]. Tighter convergence is essential for frequency calculations, while looser criteria may suffice for preliminary conformational scans.

Experimental Protocol for Geometry Optimization

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for performing a geometry optimization, from initial setup to verification of convergence.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Input Preparation

- Initial Coordinates: Generate a reasonable 3D molecular structure using a builder tool or from a crystal structure database. Avoid severe steric clashes.

- Computational Method: Select an appropriate electronic structure method (e.g., DFT with a specific functional, HF, MP2) and basis set suited to your system and accuracy requirements.

- Software Input: Prepare the input file specifying the geometry, charge, multiplicity, method, basis set, and the geometry optimization task.

Configuration of Optimization Parameters

- Optimizer Selection: Choose an optimization algorithm (e.g., Quasi-Newton, L-BFGS, FIRE) [4]. Berny and geomeTRIC are common choices in packages like PySCF [6].

- Convergence Thresholds: Set the convergence criteria based on the required precision (see Table 2). For final published structures, 'Good' or 'VeryGood' settings are recommended.

- Additional Settings: For periodic systems, enable

OptimizeLatticeto optimize unit cell parameters [4]. UseMaxIterationsto set a limit on the number of steps (e.g., 100-200).

Execution and Monitoring

- Run the optimization job.

- Monitor the output log to observe the energy, gradients, and step sizes decreasing over iterations. Most software provides real-time feedback on which criteria are satisfied.

Post-Optimization Verification

- Convergence Status: Confirm the job terminated normally and all convergence criteria were met. A non-converged result is non-optimal and should not be used for comparative analysis [5].

- Frequency Calculation: Perform a vibrational frequency calculation on the optimized geometry. A true local minimum will have no imaginary frequencies (all vibrational frequencies are real and positive). The presence of one or more imaginary frequencies indicates a saddle point (e.g., a transition state) [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Methods for Geometry Optimization

| Tool / Component | Function / Role | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Method | Calculates the energy and forces for a given nuclear configuration. | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Hartree-Fock (HF) |

| Basis Set | A set of mathematical functions used to represent molecular orbitals. | Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G*), Dunning's correlation-consistent (e.g., cc-pVDZ) |

| Optimization Algorithm | The numerical method that decides how to update the geometry to minimize energy. | Berny, L-BFGS, geomeTRIC [6] |

| Convergence Criteria | User-defined thresholds that determine when the optimization is complete. | Predefined settings (e.g., 'Good') or custom values for energy, gradient, and step [4] |

| Hessian | The matrix of second derivatives of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates; informs the optimizer about the curvature of the PES. | Calculated exactly, updated numerically, or read from a file |

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Handling Non-Convergence and Saddle Points

Optimizations may fail to converge within the allowed number of steps or may converge to a saddle point. Several strategies can address this:

- Automatic Restarts: Some software, like AMS, can automatically restart an optimization if characterization (

PESPointCharacter) reveals a saddle point. This requires disabled symmetry (UseSymmetry False) and is enabled by settingMaxRestarts> 0. The geometry is displaced along the imaginary mode before restarting [4]. - Hessian Updating: For difficult optimizations, providing a more accurate initial Hessian or requesting more frequent Hessian recalculations can improve convergence, especially for transition state searches [6].

- Trust Region Control: In transition state optimizations, parameters like

trustandtmaxin the geomeTRIC optimizer control the step size, which can be tuned to improve stability [6].

Excited State and Constrained Optimizations

- Excited States: Optimizations for excited states require specifying the electronic state in the gradient object (e.g.,

state=2for the second excited state) to ensure the correct PES is being minimized [6]. Caution is advised due to potential state flipping during the optimization. - Constraints: It is possible to optimize a structure while holding specific coordinates (e.g., a bond length or dihedral angle) fixed. The

geomeTRIClibrary supports this via a constraints file [6].

Achieving a converged geometry is a cornerstone of reliable computational chemistry. It ensures that resulting structures and their derived properties correspond to stable, physically meaningful states on the potential energy surface. By understanding and correctly applying the quantitative convergence criteria and protocols outlined in this document, researchers can produce consistent, high-quality results. This rigor is paramount in fields like drug development, where comparing the energies and properties of different molecular conformers or complexes forms the basis for rational design and discovery.

Geometry optimization is a foundational process in computational chemistry, essential for locating local minima on the potential energy surface (PES) to determine stable molecular structures. The reliability of these optimized geometries critically depends on establishing appropriate convergence criteria for four key parameters: energy change, gradient magnitude, step size, and for periodic systems, stress. These parameters collectively determine whether an optimization has successfully reached a stationary point where the molecular structure corresponds to a local energy minimum. Setting these criteria requires balancing computational cost with desired precision—overly strict thresholds demand excessive resources, while overly loose thresholds yield geometries far from the true minimum. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for configuring these essential convergence parameters within the context of computational chemistry research, particularly supporting drug development workflows where accurate molecular structures underpin property prediction and reactivity analysis.

Quantitative Convergence Criteria

Convergence criteria define the thresholds at which an optimization is considered complete. The most common criteria and their quantitative values, as implemented in the AMS software package, are summarized below [4].

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization

| Criterion | Default Value | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1×10⁻⁵ | Hartree | Change in energy per atom between successive optimization steps. |

| Gradients | 0.001 | Hartree/Angstrom | Maximum component of the Cartesian nuclear gradient. |

| Step | 0.01 | Angstrom | Maximum component of the Cartesian step in nuclear coordinates. |

| StressEnergyPerAtom | 0.0005 | Hartree | Maximum value of (stresstensor * cellvolume) / numberofatoms (for lattice optimization). |

A geometry optimization is considered converged only when all the following conditions are simultaneously met [4]:

- The energy change between successive steps is smaller than

Convergence%Energy× number of atoms. - The maximum Cartesian nuclear gradient is smaller than

Convergence%Gradients. - The root mean square (RMS) of the Cartesian nuclear gradients is smaller than 2/3 ×

Convergence%Gradients. - The maximum Cartesian step is smaller than

Convergence%Step. - The RMS of the Cartesian steps is smaller than 2/3 ×

Convergence%Step.

A notable exception is that if the maximum and RMS gradients are both 10 times smaller than the Convergence%Gradients criterion, the step-based criteria (4 and 5) are ignored [4].

Pre-Defined Quality Settings

To simplify the selection process, many computational packages offer pre-defined quality levels that simultaneously adjust all convergence thresholds. The table below outlines these settings for the AMS package [4].

Table 2: Convergence Thresholds by Quality Level

| Quality Level | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | StressEnergyPerAtom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

Experimental Protocols for Convergence Analysis

Protocol 1: Systematic Convergence Testing for a Molecule

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal convergence parameters for a specific molecular system by systematically varying criteria and assessing their impact on geometry and computational cost.

Initial Setup:

- Select a target molecule and generate an initial 3D structure.

- Choose a computational method (e.g., DFT functional and basis set) appropriate for your system.

- Begin with a

Normalquality pre-defined setting to establish a baseline [4].

Systematic Variation:

- Perform a series of geometry optimizations on the same initial structure.

- In each subsequent calculation, tighten one convergence parameter (e.g.,

Gradients) by an order of magnitude while keeping the others at theNormallevel. - Repeat this process for each of the four key parameters.

Result Analysis:

- Computational Cost: Record the number of optimization cycles and total CPU time for each calculation.

- Geometry Comparison: For each optimized structure, calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic coordinates relative to the structure obtained with the tightest (

VeryGood) criteria. - Energy Comparison: Compare the final total energy with the

VeryGoodbenchmark.

Interpretation:

- Plot the RMSD and computational cost against the stringency of each parameter.

- The optimal parameter is one beyond which further tightening yields negligible improvement in geometry (< 0.01 Å RMSD) or energy (< 1 kJ/mol) but significantly increases computational cost.

Protocol 2: Lattice Parameter Optimization for a Periodic Solid

Objective: To obtain a converged crystal structure for a solid-state material, which requires optimizing both atomic positions and lattice vectors.

Initialization:

- Build the initial crystal structure with approximate lattice parameters.

- In the input, enable the

OptimizeLatticekeyword in the geometry optimization block [4].

Parameter Selection:

Execution and Monitoring:

- Run the optimization. The algorithm will now minimize the energy with respect to nuclear coordinates and lattice vectors.

- Monitor the stress tensor components; they should approach zero as the optimization converges.

Validation:

- Upon convergence, calculate the elastic constants or phonon dispersion to confirm the structure is at a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

- Compare the calculated lattice parameters with known experimental or high-level theoretical values to validate the chosen convergence criteria.

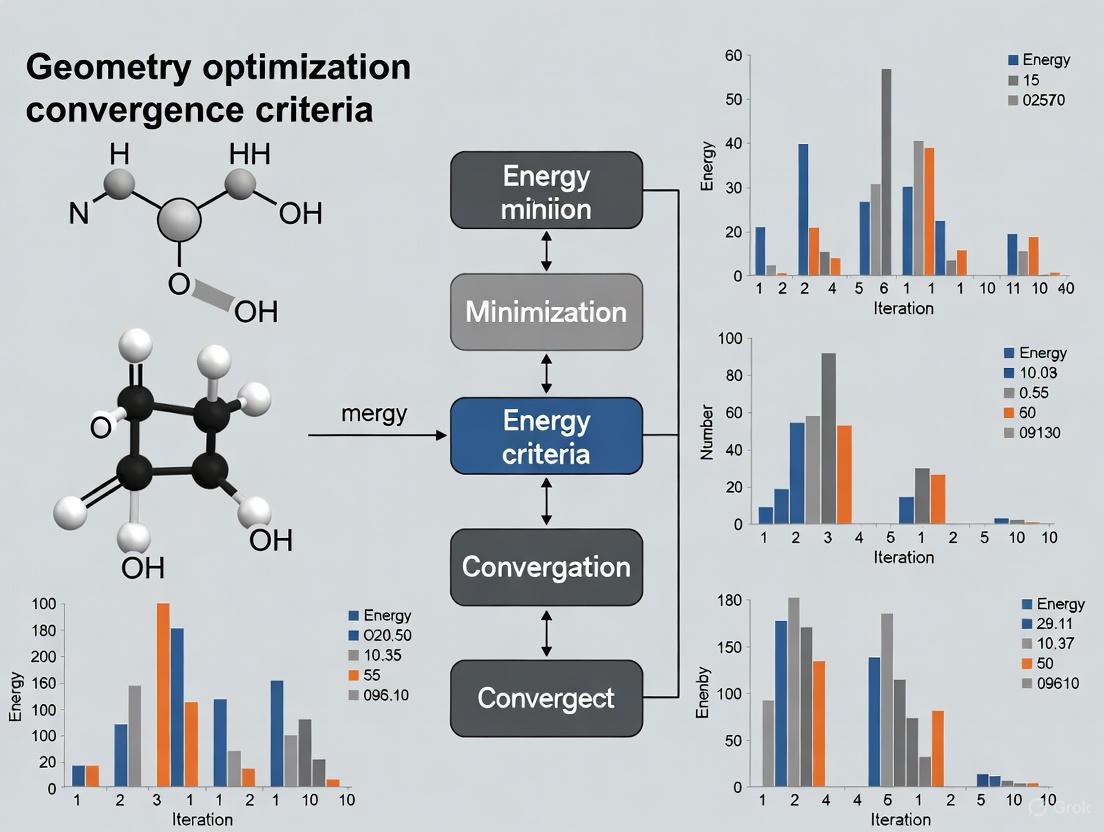

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive geometry optimization study, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This section details the key computational "reagents" — software, algorithms, and data — required for conducting robust geometry optimizations.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization

| Tool Category | Example | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Engines | ADF, BAND, VASP, Gaussian, ORCA | Provides the fundamental quantum mechanical method (e.g., DFT, HF) to calculate the system's energy and nuclear gradients for a given geometry. |

| Optimization Algorithms | L-BFGS, FIRE, Quasi-Newton | The core algorithm that uses energy and gradient information to iteratively update the atomic coordinates towards a minimum [4] [7]. |

| Specialized Optimizers | Sella, geomeTRIC | Advanced optimizers that often use internal coordinates, which can be more efficient for complex molecular systems and help avoid false minima [7]. |

| Benchmark Datasets | GMTKN55, Wiggle150 | Curated sets of molecules with reference data for validating the accuracy and transferability of a chosen method and its convergence settings [7]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | AIMNet2, OrbMol, EMFF-2025 | Machine-learning models trained on DFT data that can provide energies and forces at a fraction of the cost, enabling faster optimizations for large systems [8] [7]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Tools | pyiron, DP-GEN | Automated workflows that help determine optimal numerical parameters (e.g., plane-wave cutoff, k-points) to control the error in the underlying single-point calculations [9]. |

Best Practices and Troubleshooting

- Prioritize Gradient Convergence: For accurate final geometries, tightening the gradient criterion (

Convergence%Gradients) is generally more reliable than tightening the step criterion. The estimated uncertainty in coordinates is tied to the Hessian, which may be inaccurate during optimization, making the step criterion a less precise measure [4]. - Increase Numerical Accuracy for Tight Criteria: When using very tight convergence thresholds (e.g.,

VeryGood), ensure the underlying quantum chemistry engine (e.g., ADF, BAND) is also configured for high numerical precision to provide noise-free gradients [4]. - Handle Saddle Points with Care: If an optimization converges to a saddle point (indicated by imaginary frequencies), enable PES point characterization and automatic restart. This feature, when combined with

UseSymmetry FalseandMaxRestarts > 0, can displace the geometry along the imaginary mode and restart the optimization to find a true minimum [4]. - Optimizer Selection for Noisy Potentials: When using machine-learned interatomic potentials, which can have slightly noisy potential energy surfaces, first-order methods like FIRE or robust quasi-Newton methods like L-BFGS can be more effective and stable than some higher-order methods [7].

Geometry optimization is a fundamental computational procedure in theoretical chemistry that refines molecular structures to locate local minima on the potential energy surface (PES). This process iteratively adjusts nuclear coordinates until the system reaches a stationary point where the energy gradient approaches zero, indicating an equilibrium geometry. The accuracy and efficiency of these optimizations are governed by convergence criteria—numerical thresholds that determine when the iterative process can be terminated while ensuring reliable results. These criteria represent a critical balance between computational expense and chemical accuracy, making their appropriate selection essential for meaningful research outcomes.

Within computational chemistry frameworks, convergence parameters are often grouped into predefined quality levels that systematically control multiple threshold values simultaneously. These settings range from loose "VeryBasic" criteria intended for preliminary scanning to tight "VeryGood" thresholds for high-precision work. The strategic selection of appropriate convergence levels directly impacts both the reliability of optimized structures and the computational resources required, making this choice particularly relevant for researchers in drug development who must balance accuracy with practical constraints.

Theoretical Framework and Threshold Values

Core Convergence Criteria

Geometry optimization algorithms assess convergence through multiple complementary criteria that collectively ensure the molecular structure has reached a genuine local minimum. The primary metrics include:

- Energy Change: The difference in total energy between successive optimization cycles, indicating whether the system is still progressing toward lower energy regions of the PES.

- Gradient Norm: The magnitude of the first derivative of energy with respect to nuclear coordinates, which should approach zero at stationary points.

- Step Size: The change in nuclear coordinates between iterations, which diminishes as the optimizer approaches convergence.

- Stress Energy per Atom: Specifically for periodic systems, this measures the convergence of lattice parameters during optimization.

These criteria work synergistically to prevent premature convergence and ensure the optimized structure represents a true local minimum rather than a region with shallow gradient [4].

Standardized Quality Settings

The AMS computational package implements a tiered system of convergence thresholds through its "Quality" parameter, which simultaneously adjusts all individual criteria to predefined values. This systematic approach ensures internal consistency across convergence metrics and simplifies protocol selection for users. The specific threshold values associated with each quality level are detailed in Table 1 [4].

Table 1: Standard Convergence Thresholds for Geometry Optimization

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | StressEnergyPerAtom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

These predefined settings provide a progressive series of accuracy levels, with "Normal" representing a balanced default suitable for many applications. The "VeryGood" setting imposes thresholds approximately 100 times stricter than "Normal" for energy convergence and 100 times stricter for gradient convergence, resulting in significantly higher computational demands but potentially more reliable structures for sensitive applications [4].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Optimization Workflow

The geometry optimization process follows a systematic workflow that integrates the convergence criteria at each iterative cycle. The complete procedure, from initial coordinates to converged structure, can be visualized as a cyclic process of coordinate updating, property calculation, and convergence checking, as illustrated below:

Diagram 1: Geometry optimization workflow with convergence checking

This workflow implements the fundamental optimization cycle where each iteration updates the molecular structure based on the current energy landscape, calculates new electronic properties, and assesses whether convergence thresholds have been met. The process continues until all specified criteria are simultaneously satisfied or until a maximum iteration limit is reached [4] [10].

Practical Implementation Guidelines

Successful implementation of geometry optimization requires careful consideration of both the molecular system and research objectives. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach:

Initial Structure Preparation

- Generate reasonable starting coordinates from molecular building or previous calculations

- For drug development applications, ensure stereochemistry and functional group orientations are chemically plausible

Quality Level Selection

- Choose "VeryBasic" for preliminary scanning of conformational space

- Select "Normal" for most routine optimizations of drug-like molecules

- Reserve "Good" or "VeryGood" for final production calculations where high precision is required

- Consider that tighter criteria require more computational resources and may reveal convergence difficulties in certain electronic structure methods [4] [11]

Methodology Considerations

- Ensure the electronic structure method (DFT, HF, etc.) and basis set are appropriate for the molecular system

- Verify that the chosen computational method can deliver gradients with sufficient numerical accuracy for the selected convergence thresholds

- For large systems, consider fragmentation methods or multilayer approaches that can maintain accuracy with looser convergence criteria [12]

Convergence Monitoring

- Track all convergence criteria throughout the optimization process

- For stubborn optimizations, consider restarting with improved initial coordinates or adjusted methodology

- Implement characterization calculations (e.g., frequency analysis) to verify the nature of stationary points [4]

This protocol emphasizes that convergence threshold selection is not merely a technical detail but a strategic decision that should align with the overall research goals and computational constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of geometry optimization with appropriate convergence criteria requires specific computational tools and methodologies. Table 2 summarizes key components of the researcher's toolkit for managing convergence in computational chemistry:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Geometry Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Convergence Management |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Methods | DFT (B3LYP, ωB97X-D), HF, MP2, CCSD(T) | Provide energy and gradient calculations with varying accuracy/cost tradeoffs [11] [13] |

| Basis Sets | def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ | Balance computational cost with description of electron distribution [11] |

| Dispersion Corrections | D3, D4 | Account for weak interactions crucial for molecular complexes [11] |

| Solvation Models | COSMO, PCM, SMD | Incorporate environmental effects on molecular structure [11] |

| Fragmentation Methods | EE-GMFCC, FMO | Enable calculations on large systems (e.g., protein-ligand complexes) [12] |

| Optimization Algorithms | L-BFGS, conjugate gradient, Newton-Raphson | Efficiently navigate potential energy surface [10] |

These tools form the foundation for managing the relationship between convergence criteria and research outcomes. For drug development applications, the combination of robust density functionals with adequate basis sets and solvation models is particularly important for achieving chemically meaningful results [11].

Decision Framework for Threshold Selection

Selecting appropriate convergence criteria requires consideration of multiple factors, including system size, computational methodology, and research objectives. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach to threshold selection:

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for convergence threshold selection

This decision framework emphasizes that system size often dictates practical constraints, with larger systems typically requiring more relaxed convergence criteria due to computational limitations. Similarly, the choice of electronic structure method imposes inherent limitations on achievable precision, as some methods may not be able to reliably compute gradients below certain thresholds [4] [12].

Applications in Drug Development and Research

Structure-Based Drug Design

In drug development, accurate molecular geometries are crucial for predicting binding affinities and interaction patterns. Convergence criteria directly impact the reliability of these predictions:

- Ligand Structure Optimization: Tight convergence criteria ("Good" to "VeryGood") ensure accurate representation of ligand geometry before docking studies, particularly for flexible molecules with multiple rotatable bonds.

- Protein-Ligand Complexes: For full quantum treatment of binding interactions, balanced convergence criteria ("Normal" to "Good") provide sufficient accuracy while maintaining computational feasibility.

- Conformational Analysis: Looser criteria ("Basic" to "Normal") can efficiently scan conformational space, with selected minima subsequently refined with tighter thresholds [14].

Recent studies demonstrate that inadequate convergence can lead to significant errors in predicted binding energies, sometimes exceeding chemical significance thresholds (>1 kcal/mol). This emphasizes the importance of threshold selection in computational drug design workflows [12].

Machine Learning Integration

Emerging approaches combine traditional optimization with machine learning to enhance efficiency. For instance, machine-learned density matrices can achieve accuracy comparable to fully converged self-consistent field calculations while potentially reducing computational cost. These methods can predict one-electron reduced density matrices (1-RDMs) with deviations within standard SCF convergence thresholds, demonstrating how hybrid approaches can maintain accuracy while optimizing computational resources [15].

Similarly, Bayesian optimization methods provide statistical frameworks for assessing convergence, monitoring both expected improvement and local stability of variance to determine when further optimization is unlikely to yield significant gains. These approaches offer promising alternatives to fixed threshold-based convergence criteria, particularly for complex systems with rough potential energy surfaces [16].

Convergence criteria represent a fundamental aspect of computational chemistry that directly influences the reliability and efficiency of molecular geometry optimizations. The standardized quality settings from "VeryBasic" to "VeryGood" provide researchers with a systematic approach to controlling computational accuracy, with each level offering distinct tradeoffs between precision and resource requirements. For drug development researchers, appropriate threshold selection must consider both the specific research objectives and practical computational constraints, with the understanding that different stages of investigation may benefit from different convergence criteria. As computational methodologies continue to evolve, particularly through integration with machine learning approaches, the management of convergence thresholds will remain an essential consideration for generating chemically meaningful results in computational chemistry research.

In computational chemistry, geometry optimization is the process of iteratively adjusting a molecule's nuclear coordinates to locate a stationary point on the potential energy surface—typically a local minimum corresponding to a stable conformation. The success of this process hinges on accurately determining when this point has been reached, making the interpretation of convergence metrics critical for producing reliable, publishable results. Two complementary metrics form the cornerstone of this assessment: the maximum (Max) residual and the root-mean-square (RMS) residual.

The RMS residual provides a measure of the typical magnitude of the forces acting on atoms by calculating the square root of the average of the squared residuals across all degrees of freedom. In contrast, the Maximum residual identifies the single largest force component in the system. Within the context of drug development, where subtle conformational differences can dramatically impact binding affinity and selectivity, a rigorous understanding of these metrics ensures that optimized ligand and protein structures are physically meaningful and not artifacts of incomplete convergence.

Theoretical Foundation of RMS and Maximum Metrics

Mathematical Definitions and Formulations

The Root-Mean-Square (RMS) and Maximum (Max) metrics are derived from the gradients of the energy with respect to the nuclear coordinates—the forces acting on the atoms. For a system with N degrees of freedom, the force components (e.g., along x, y, z for each atom) can be denoted as F₁, F₂, ..., Fₙ.

- RMS (Root-Mean-Square): The RMS value is calculated as the square root of the mean of the squares of all individual force components. This provides a measure of the average force magnitude across the entire system.

RMS = √[ (F₁² + F₂² + ... + Fₙ²) / N ][17] - Maximum (Max): The Max value is simply the largest absolute value among all the individual force components.

Max = max(|F₁|, |F₂|, ..., |Fₙ|)[18]

The RMS metric is inherently a global measure, as it incorporates data from every degree of freedom in the system. Its value is influenced by the entire set of forces, making it a good indicator of the overall convergence of the molecular structure. Conversely, the Maximum metric is a local measure, sensitive only to the single largest force component. It is possible for the RMS value to appear satisfactory while the Max value remains high if most atoms have converged but one or a few atoms are still experiencing significant forces. [17] [18]

The Role of Metrics in Convergence Criteria

Most computational chemistry packages do not rely on a single metric but define convergence as a set of conditions that must be satisfied simultaneously. A common and robust approach involves four criteria, as exemplified by software like Gaussian: [18]

- The maximum force must be below a specified threshold.

- The RMS force must be below a specified threshold.

- The maximum displacement (change in atomic coordinates between iterations) must be below a threshold.

- The RMS displacement must be below a threshold.

Some packages include an alternative convergence condition: if the maximum and RMS forces are two orders of magnitude (100 times) tighter than the default thresholds, the displacement criteria may be ignored. This acknowledges that extremely low forces are a definitive sign of convergence, even if the coordinates are still shifting slightly. [18]

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria for Geometry Optimization in Different Software Packages

| Software Package | Convergence Quality | Maximum Force (Hartree/Bohr) | RMS Force (Hartree/Bohr) | Maximum Displacement (Bohr/Angstrom) | RMS Displacement (Bohr/Angstrom) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMS | Normal | 10⁻³ | 6.67×10⁻⁴ | 0.01 Å | 0.0067 Å |

| Good | 10⁻⁴ | 6.67×10⁻⁵ | 0.001 Å | 0.00067 Å | |

| Very Good | 10⁻⁵ | 6.67×10⁻⁶ | 0.0001 Å | 0.000067 Å | |

| Gaussian | Default | 0.000450 | 0.000300 | 0.001800 | 0.001200 |

Practical Application and Protocol Design

A Standard Protocol for Monitoring and Verifying Convergence

A robust workflow is essential to ensure that a geometry optimization has genuinely converged to a valid stationary point. The following protocol integrates best practices from multiple computational chemistry communities.

Step 1: Pre-Optimization Checks

- Initial Structure: Begin with a reasonable initial geometry, ideally from experimental data or a pre-optimization with a lower-level theory.

- Method and Basis Set: Select a method (e.g., DFT, MP2) and basis set appropriate for your system. Remember that tighter convergence requires more accurate gradients. [19]

- Software Settings: Choose an appropriate optimizer (e.g., GDIIS, L-BFGS) and set convergence criteria. Starting with the "Normal" or "Good" preset is advisable. [4] [20]

Step 2: Active Monitoring During Optimization

- Monitor History: Track the evolution of the energy, RMS, and Max forces (and displacements) across optimization cycles. Look for a monotonic decrease or stable oscillation around a low value. [19] [21]

- Correlation of Metrics: Do not rely on a single metric. Confirm that both RMS and Max values are trending toward zero. Be wary of cases where RMS is low but Max remains high, indicating a localized problem. [22]

Step 3: Post-Optimization Verification (Critical Step)

- Frequency Calculation: Always perform a frequency calculation on the optimized geometry. This is a non-negotiable step for validation. [18]

- Validate Stationary Point: The frequency job will also calculate the gradients. Check its output to ensure that the structure still satisfies the convergence criteria. A "Stationary point found" message and zero imaginary frequencies (for a minimum) confirm success. If the frequency job fails the convergence test, the structure is not a true stationary point and the optimization must be continued. [18]

Step 4: Troubleshooting and Restarting

- If Convergence is Slow/Oscillatory: Increase the numerical integration grid size (e.g., to

Int=UltraFinein Gaussian), tighten the SCF convergence, or use a higher numerical quality setting. [18] [19] - If Verification Fails: Restart the optimization from the last geometry, using the Hessian (force constants) from the frequency calculation (

Opt=ReadFC) to guide the final steps to convergence. [18]

Interpreting Metric Behavior and Troubleshooting

Understanding the different behaviors of RMS and Max metrics is key to diagnosing problems during optimization.

- RMS is Low, Max is High: This indicates a localization problem. A single atom, or a small group of atoms, may be experiencing a strong force due to a steric clash, an incorrect bonding assignment, or the molecule being trapped in a very flat region of the potential energy surface near the minimum. Inspect the geometry visually and check for unrealistic bond lengths or angles. [22] [19]

- Both RMS and Max Oscillate: This often suggests numerical instability in the energy or gradient calculations. For DFT methods, switching to a finer integration grid (

Int=UltraFine) is the most common fix. Tightening the SCF convergence criterion can also help. [18] [19] - Energy is Flat but Forces are Not: In very flat regions of the PES, the energy change between steps may be negligible, but the forces might not have reached the convergence threshold. This requires patience, as the optimizer may need many steps to "roll downhill" on a very shallow slope. [18]

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Convergence Problems Based on Metric Behavior

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Max Force, Good RMS Force | Localized strain; steric clash; incorrect connectivity. | Visually inspect geometry; check bonding; consider constraints. |

| Oscillating Energies & Metrics | Numerical noise; inadequate SCF convergence; poor integration grid. | Use finer integration grid; tighten SCF convergence; increase numerical quality. |

| Slow Convergence in Flat PES | Very shallow potential energy surface. | Use a tighter gradient convergence criterion; employ a more robust optimizer (e.g., GDM). |

| Failed Frequency Verification | Estimated Hessian in optimization is inaccurate. | Restart optimization with ReadFC to use analytical Hessian from frequency job. |

Successful geometry optimization relies on a combination of software, hardware, and methodological "reagents." The following table details key components of a computational researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for Geometry Optimization Studies

| Item Name/Software | Type | Primary Function in Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Software Package | Performs optimization and frequency analysis; implements well-established convergence criteria. [18] |

| AMS | Software Package | Features the ADF module for DFT, with configurable convergence thresholds via the Quality keyword. [4] |

| PSI4/optking | Software Package | Provides a modern, open-source optimization module supporting multiple algorithms (RFO, GDM) and convergence sets. [23] |

| Q-Chem | Software Package | Offers advanced SCF algorithms (DIIS, GDM) for robust wavefunction convergence, which underpirds accurate gradients. [20] |

| UltraFine Grid | Numerical Setting | A dense integration grid in DFT that reduces numerical noise in gradients, aiding stable convergence. [18] |

| Initial Hessian | Computational Object | The starting guess for second derivatives; can be calculated or empirical. A good guess accelerates convergence. [23] |

| ReadFC | Keyword/Restart Option | Instructs the optimizer to use the Hessian from a previous frequency calculation, improving final steps. [18] |

| Square Integrable Wavefunction | Mathematical Criterion | A fundamental requirement for the validity of the quantum chemical calculation, ensuring energies and properties are well-defined. [24] |

The path to a reliably optimized molecular structure is navigated using both the RMS and Maximum convergence metrics as complementary guides. The RMS value assures the global quality of the structure, while the Maximum value guards against localized errors that could invalidate the result. By adhering to a rigorous protocol that includes post-optimization frequency verification and a structured troubleshooting approach, researchers can have high confidence in their computational structures. This disciplined methodology is indispensable in drug development, where the quantitative interpretation of molecular interactions—from docking poses to free-energy perturbations—depends entirely on the foundation of a correctly optimized geometry.

Geometry optimization in computational chemistry is an iterative process that adjusts a molecule's nuclear coordinates to locate a local minimum on the potential energy surface (PES). This minimum represents a stable molecular structure where the net forces on atoms approach zero. Convergence criteria are the thresholds that determine when this process successfully terminates, balancing computational efficiency against structural accuracy. Understanding the physical meaning behind these numerical thresholds is essential for researchers interpreting computational results and ensuring their molecular structures possess the precision required for subsequent property calculations and scientific publication.

The fundamental challenge lies in selecting criteria stringent enough to yield chemically meaningful structures without incurring excessive computational cost. Different research objectives—from high-throughput virtual screening to precise spectroscopic property prediction—demand different levels of structural precision. This application note explores the quantitative relationship between convergence thresholds and the resulting geometric precision of optimized molecular structures, providing protocols for selecting appropriate criteria within drug development workflows.

Theoretical Foundation: The Physical Interpretation of Convergence Parameters

Core Convergence Criteria and Their Structural Significance

Geometry optimization convergence is typically assessed through multiple, complementary criteria that monitor changes in energy, forces, and atomic displacements between iterations. Each criterion provides distinct insights into the quality of the optimized structure.

The energy change criterion (Convergence%Energy) monitors the difference in total electronic energy between successive optimization steps. When the energy change falls below a threshold normalized per atom (e.g., 10⁻⁵ Hartree for "Normal" quality), the structure is considered stable within the PES minimum. Tighter thresholds (10⁻⁶–10⁻⁷ Hartree) are necessary for predicting subtle energy-dependent properties like conformational energies or binding affinities [4].

The gradient criterion (Convergence%Gradients) directly measures the maximum Cartesian force on any atom. A threshold of 0.001 Hartree/Å ("Normal" quality) typically ensures bond lengths are precise to approximately 0.001 Å and angles to 0.1°. Importantly, when gradients become sufficiently small (10 times lower than the threshold), the step size criteria are often waived, as the structure is confirmed to be near the minimum [4].

The step size criterion (Convergence%Step) monitors the maximum displacement of any atom between iterations. While useful for detecting ongoing structural changes, it is considered less reliable than gradients for assessing final structural precision because it depends on the optimization algorithm's internal step control. For precise structural determinations, tightening the gradient criterion provides more reliable control than tightening step sizes alone [4].

Practical Implications for Molecular Structure

The selected convergence criteria directly influence key structural parameters critical to drug discovery:

- Bond lengths: Loose criteria (10⁻² Ha/Å gradients) may yield errors up to 0.01 Å, significant when analyzing metalloprotein active sites or covalent inhibitor complexes.

- Bond angles: "Normal" criteria (10⁻³ Ha/Å) typically preserve angles within 0.1–0.5°, while "Good" criteria (10⁻⁴ Ha/Å) improve precision to 0.05–0.1°, important for predicting protein-ligand interactions.

- Dihedral angles: Torsional degrees of freedom require tighter convergence (10⁻⁵ Ha/Å) for reliable conformational analysis, particularly for flexible linkers in drug-like molecules.

- Reaction coordinates: Transition state optimizations and reaction pathway calculations demand the strictest criteria to accurately characterize saddle points on the PES.

For periodic systems, additional criteria for stress tensor components (StressEnergyPerAtom) control lattice parameter precision during crystal structure optimizations [4].

Quantitative Data: Convergence Thresholds and Structural Precision

Standard Convergence Presets and Their Applications

Table 1: Standard Convergence Quality Settings in AMS and Their Structural Implications

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | Recommended Applications | Expected Bond Length Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | Preliminary screening, crude scans | >0.01 Å |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | Initial optimization steps | ~0.01 Å |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | Standard drug discovery workflows | 0.001–0.005 Å |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | Spectroscopy, conformational analysis | 0.0005–0.001 Å |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | High-precision reference data | <0.0005 Å |

These quality presets provide predefined combinations of thresholds for different research needs. The "Normal" setting offers a practical balance for most drug discovery applications, while "Good" or "VeryGood" are recommended for calculating molecular properties that depend on fine structural details [4].

Optimizer Performance Across Convergence Criteria

Recent benchmarking studies reveal significant performance differences among common optimization algorithms when converging molecular structures with neural network potentials (NNPs). These differences impact both computational efficiency and the quality of final structures.

Table 2: Optimizer Performance with Neural Network Potentials (25 Drug-like Molecules)

| Optimizer | Successful Optimizations (OrbMol/OMol25 eSEN) | Average Steps to Convergence | Minima Found (%) | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 22/23 | 108.8/99.9 | 64%/64% | Balanced performance for diverse systems |

| ASE/FIRE | 20/20 | 109.4/105.0 | 60%/56% | Noisy PES, initial relaxation |

| Sella (internal) | 20/25 | 23.3/14.9 | 60%/96% | Efficient convergence to minima |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1/20 | 11/114.1 | 4%/68% | Systems with internal coordinates |

The data demonstrates that Sella with internal coordinates achieves the fastest convergence (fewest steps) while maintaining high success rates for locating true minima. In contrast, Cartesian coordinate methods like geomeTRIC (cart) require significantly more steps and may fail to locate minima despite achieving gradient convergence [7]. This highlights that meeting formal convergence criteria does not guarantee a structure is at a true minimum—vibrational frequency analysis remains essential for confirmation.

Experimental Protocols for Convergence Assessment

Protocol 1: Systematic Convergence Testing for Method Validation

Purpose: To establish appropriate convergence criteria for a specific research project, molecular system, and computational method.

Materials and Software:

- Molecular structure files (XYZ, PDB, or other format)

- Computational chemistry software (AMS, ORCA, Gaussian, etc.)

- Sufficient computational resources (CPU/GPU hours)

Procedure:

- Initial Preparation:

- Select 3–5 representative molecular structures from your research domain

- Choose a computational method appropriate for your system (DFT functional, basis set, NNP)

- Define a range of convergence criteria to test (e.g., Basic to VeryGood)

Optimization Series:

- For each test structure, perform geometry optimizations with each convergence setting

- Use identical initial structures and computational methods across all tests

- Record the number of optimization steps, computational time, and final energy for each run

Structural Analysis:

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between structures optimized with different criteria

- Compare key structural parameters (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals) against experimental data or high-level reference calculations

- Perform vibrational frequency analysis on optimized structures to confirm minima

Convergence Assessment:

- Identify the point of diminishing returns where tighter criteria yield negligible structural improvement

- Select the most efficient criteria that provide sufficient precision for your research goals

Expected Outcomes: A project-specific convergence protocol that balances computational cost with required structural accuracy, documented with comparative structural metrics.

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Problematic Optimizations

Purpose: To address common optimization failures including oscillation, slow convergence, or convergence to saddle points.

Materials and Software:

- Problematic molecular structure

- Computational chemistry software with advanced SCF and optimization controls

Procedure:

- Diagnosis:

- Examine optimization history for oscillatory behavior or slow progress

- Check for molecular symmetry that might maintain degeneracies

- Identify potential mixing of electronic states in open-shell systems

SCF Convergence Improvements:

- Increase maximum SCF iterations (

MaxIter 500in ORCA) [25] - Implement damping or level shifting for oscillatory systems (

SlowConvin ORCA) [25] - Use quadratic convergence methods (

SCF=QCin Gaussian) for pathological cases [26] - Improve initial guess via smaller basis set calculation or closed-shell analog

- Increase maximum SCF iterations (

Optimization Algorithm Adjustments:

Structural Modifications:

- Slightly distort symmetric structures to break degeneracies

- Manually adjust problematic torsion angles or bond lengths

- For transition metals, consider different spin state initializations

Validation:

Expected Outcomes: Successful optimization of challenging molecular systems with verified minimum structures suitable for further analysis.

Visualization of Optimization Workflows

Geometry Optimization Decision Pathway

Diagram 1: Geometry Optimization Decision Pathway. This workflow illustrates the iterative optimization process with critical decision points for convergence assessment and saddle point recovery.

Convergence Criteria Interrelationships

Diagram 2: Convergence Criteria Interrelationships. This diagram illustrates how different convergence criteria predominantly control specific aspects of molecular structure precision and property accuracy.

Research Reagent Solutions for Geometry Optimization

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Quality Presets | Predefined threshold combinations | Rapid setup for standard applications | Convergence%Quality Good [4] |

| PES Point Characterization | Stationary point identification | Detecting minima vs. saddle points | PESPointCharacter True [4] |

| Automatic Restart | Saddle point recovery | Continuing from displaced geometry | MaxRestarts 5, RestartDisplacement 0.05 [4] |

| Lattice Optimization | Periodic cell parameter optimization | Crystal structure refinement | OptimizeLattice Yes [4] |

| SCF Convergence Accelerators | Overcoming wavefunction convergence issues | Difficult electronic structures | SlowConv, DIISMaxEq 15 [25] |

| Alternative Optimizers | Algorithm switching for problematic cases | Specific molecular challenges | Sella, geomeTRIC, FIRE, L-BFGS [7] |

The numerical thresholds defining geometry optimization convergence criteria possess direct physical meaning for the precision of resulting molecular structures. Gradient thresholds around 10⁻³ Hartree/Å ("Normal" quality) typically ensure bond length precision of 0.001–0.005 Å, sufficient for most drug discovery applications, while stricter thresholds (10⁻⁵ Hartree/Å) may be necessary for spectroscopic property prediction. The relationship between criteria and structural precision is not merely algorithmic but fundamentally connected to the topography of the potential energy surface and the sensitivity of molecular properties to geometric parameters. By implementing the systematic assessment protocols and visualization workflows outlined in this application note, researchers can make informed decisions about convergence criteria selection, ensuring their computational methodologies yield structures with precision appropriate to their scientific objectives in pharmaceutical development.

Implementation in Practice: Software, Optimizers, and Workflows

A Comparative Look at Convergence Settings in AMS, PySCF, and CRYSTAL

Geometry optimization, the process of finding a stable atomic configuration corresponding to a local minimum on the potential energy surface (PES), is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and materials science [4]. The accuracy and efficiency of these optimizations are critically dependent on the convergence criteria, which determine when the iterative process can be terminated reliably. Modern computational packages offer sophisticated control over these settings, yet the specific parameters and their default values vary significantly between software implementations. This application note provides a detailed, comparative analysis of the convergence settings and optimization methodologies in three prominent computational chemistry packages: the Amsterdam Modeling Suite (AMS), PySCF, and CRYSTAL. Framed within a broader thesis on computational efficiency and reliability, this work aims to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select and fine-tune settings for their specific applications, from molecular drug design to crystalline material discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Convergence Criteria

The convergence of a geometry optimization is typically judged by simultaneous satisfaction of multiple criteria, commonly including thresholds for energy change, nuclear gradients (forces), and the step size in coordinate space. The definitions and default values for these criteria, however, are not uniform across different software packages.

AMS (Amsterdam Modeling Suite)

In the AMS driver, a geometry optimization is considered converged only when a set of comprehensive conditions are met [4]. The key convergence criteria are configured in the GeometryOptimization%Convergence block and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Default Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria in AMS

| Criterion | Keyword | Default Value | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | Convergence%Energy |

1×10⁻⁵ | Hartree | Change in energy between steps < (Value) × (Number of atoms) |

| Max Gradient | Convergence%Gradients |

0.001 | Hartree/Å | Maximum Cartesian nuclear gradient must be below this value. |

| RMS Gradient | (Automatic) | 0.00067 | Hartree/Å | RMS of Cartesian nuclear gradients must be below ⅔ of Gradients. |

| Max Step | Convergence%Step |

0.01 | Å | Maximum Cartesian step must be below this value. |

| RMS Step | (Automatic) | 0.0067 | Å | RMS of Cartesian steps must be below ⅔ of Step. |

| Lattice Stress | StressEnergyPerAtom |

0.0005 | Hartree | Threshold for lattice optimization (max stresstensor * cellvolume / numberofatoms). |

A notable feature in AMS is the Convergence%Quality keyword, which provides a quick way to uniformly tighten or relax all thresholds. The "Normal" quality corresponds to the default values, while "Good" and "VeryGood" tighten them by one and two orders of magnitude, respectively [4]. Furthermore, AMS includes an advanced automatic restart mechanism. If a system with disabled symmetry converges to a transition state, the optimization can automatically restart from a geometry displaced along the imaginary mode, provided MaxRestarts is set above zero and the PES point characterization is enabled [4].

PySCF

PySCF, a Python-based quantum chemistry package, leverages external optimizers like geomeTRIC and PyBerny. Consequently, its convergence parameters are specific to these backends, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Default Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria in PySCF

| Criterion | geomeTRIC Default | PyBerny Default | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Energy | 1×10⁻⁶ | - | Hartree |

| Max Gradient | 4.5×10⁻⁴ | 0.45×10⁻³ | Hartree/Bohr |

| RMS Gradient | 3.0×10⁻⁴ | 0.15×10⁻³ | Hartree/Bohr |

| Max Step | 1.8×10⁻³ | 1.8×10⁻³ | Å (geomeTRIC), Bohr (PyBerny) |

| RMS Step | 1.2×10⁻³ | 1.2×10⁻³ | Å (geomeTRIC), Bohr (PyBerny) |

PySCF offers two primary ways to invoke optimization: by using the optimize function from pyscf.geomopt.geometric_solver or pyscf.geomopt.berny_solver, or by creating an optimizer directly from the Gradients class [6] [27]. The package also supports constrained optimizations and transition state searches via the geomeTRIC backend, which can be activated by passing 'transition': True in the parameters [6].

CRYSTAL

The search results do not provide specific, detailed convergence criteria for the CRYSTAL package. CRYSTAL is a well-established code for ab initio calculations of crystalline systems, and its geometry optimization algorithm is known to involve careful control of the root-mean-square (RMS) and absolute maximum of the gradient and nuclear displacements. However, for precise, comparative default values and keywords, users are advised to consult the official CRYSTAL manual.

Optimization Protocols and Methodologies

AMS Optimization Protocol

The AMS driver provides a robust and feature-rich environment for geometry optimization. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for a molecular system, with notes for periodic calculations.

Diagram 1: Workflow for geometry optimization in the AMS driver, highlighting the automatic restart feature for saddle points.

- System and Engine Definition: In the

Systemblock, define the initial atomic coordinates and, for periodic systems, the lattice vectors. Select a quantum engine (e.g., ADF, BAND, DFTB) to calculate energies and forces [28]. - Task and Convergence Setup: Set

Task GeometryOptimization. In theGeometryOptimizationblock, specify convergence criteria. For high-precision results, useQuality Goodor define custom thresholds in theConvergencesub-block [4]. - Advanced Configuration (Recommended): To enable the robust automatic restart feature for finding true minima:

- Set

UseSymmetry False. - In the

Propertiesblock, setPESPointCharacter True. - In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setMaxRestartsto a small number (e.g., 3-5) [4].

- Set

- Lattice Optimization: For periodic systems, set

OptimizeLattice Yesto optimize both nuclear coordinates and lattice vectors [4]. - Execution and Analysis: Run the job. Upon convergence, analyze the output geometry and verify the PES point character is a minimum.

PySCF Optimization Protocol

PySCF offers flexibility through its Python API and integration with external optimizers. This protocol is suitable for both molecular and periodic boundary condition (PBC) systems.

Diagram 2: Geometry optimization workflow in PySCF, showing the two primary pathways using the geomeTRIC or PyBerny backend solvers.

- System Definition:

- Mean-Field Calculation: Create a mean-field object, such as

scf.RHF(mol)for molecules orscf.KRHF(cell)for periodic systems [6] [30]. - Optimizer Selection and Setup: Choose between the geomeTRIC or PyBerny backend.

- Method A (Function Call):

- Method B (Gradients Optimizer):

- Transition State Optimization: To search for a transition state with geomeTRIC, add

'transition': Truetoconv_params[6]. - Execution: The

optimizefunction returns the optimized molecule or cell object.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization

| Tool / Package | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMS Driver [28] [4] | Software Suite | Manages PES traversal for multiple engines. | Provides a unified, powerful environment with advanced features like automatic restarts and lattice optimization. |

| PySCF [6] [31] | Python Package | Electronic structure calculations. | Offers API flexibility for custom workflows and integrates with Python's scientific ecosystem (e.g., JIT, auto-diff). |

| geomeTRIC [6] | Optimizer Library | Internal coordinate-based optimization. | PySCF backend; handles constraints and transition state searches efficiently. |

| PyBerny [6] [27] | Optimizer Library | Cartesian coordinate-based optimization. | Lightweight PySCF backend for standard optimizations. |

| GPU4PySCF [31] | PySCF Extension | GPU acceleration for quantum chemistry methods. | Drastically speeds up energy and force calculations, the bottleneck in optimization. |

| PySCFAD [31] | PySCF Extension | Automatic Differentiation. | Enables efficient computation of higher-order derivatives (Hessians) for transition state searches. |

The choice of computational package and its convergence settings has a profound impact on the success and efficiency of geometry optimization tasks in research and development. AMS provides a comprehensive, "batteries-included" approach with sophisticated features like automatic PES point characterization and restarts, making it highly robust for complex molecular and material systems. In contrast, PySCF offers unparalleled flexibility and integration within a modern Python ecosystem, ideal for prototyping new methods and building complex, automated workflows. While CRYSTAL remains a powerful tool for solid-state systems, a direct comparison of its convergence parameters requires further consultation of its dedicated documentation. Ultimately, understanding these nuanced differences empowers scientists to make informed decisions, optimizing not only molecular structures but also their computational strategies for accelerated discovery in fields ranging from drug design to materials science.

In computational chemistry, geometry optimization is the process of iteratively adjusting a molecular structure's nuclear coordinates to locate a stationary point on the potential energy surface (PES), typically a local minimum corresponding to a stable conformation or a saddle point representing a transition state. The efficiency and reliability of this process are fundamentally governed by two factors: the choice of optimization algorithm and the stringency of the convergence criteria. Convergence criteria are the predefined thresholds that determine when an optimization is considered complete, ensuring that the structure has reached a point where energy changes, forces (gradients), and displacements are sufficiently small. Proper configuration of these criteria is essential for obtaining chemically meaningful results without expending excessive computational resources.

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of four prominent optimization algorithms—L-BFGS, FIRE, Sella, and geomeTRIC—framed within the critical context of convergence criteria. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it presents quantitative performance data, detailed application protocols, and strategic recommendations to guide the selection and application of these tools in modern computational workflows, including those employing neural network potentials (NNPs).

Theoretical Framework: Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria

A geometry optimization is considered converged when the structure satisfies a set of conditions that indicate it is sufficiently close to a stationary point. The most common convergence criteria monitor changes in energy, the magnitude of forces (gradients), and the size of the optimization step. As defined by the AMS package, a optimization is typically converged when all the following conditions are met [4]:

- Energy Change: The difference in the bond energy between the current and previous geometry step is smaller than a defined threshold (e.g.,

Convergence%Energy) multiplied by the number of atoms in the system. - Maximum Gradient: The maximum component of the Cartesian nuclear gradient is smaller than the

Convergence%Gradientsthreshold. - Root Mean Square (RMS) Gradient: The RMS of the Cartesian nuclear gradients is smaller than 2/3 of the

Convergence%Gradientsthreshold. - Maximum Step: The maximum Cartesian displacement in the nuclear coordinates is smaller than the

Convergence%Stepthreshold. - RMS Step: The RMS of the Cartesian steps is smaller than 2/3 of the

Convergence%Stepthreshold.

It is important to note that if the maximum and RMS gradients are an order of magnitude stricter (10 times smaller) than the convergence criterion, the step-based criteria are often ignored [4]. For lattice vector optimization in periodic systems, an additional criterion based on the stress energy per atom is used [4].

The Convergence%Quality setting in AMS offers a convenient way to simultaneously tighten or loosen all thresholds [4]:

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | StressEnergyPerAtom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

Table 1: Standard convergence quality settings as defined in the AMS documentation [4].

The choice of criteria involves a trade-off between computational cost and structural accuracy. Overtightening can lead to an excessive number of steps with minimal chemical improvement, while overly loose criteria may yield structures that are far from the true minimum [4]. For optimizations using noisy potential energy surfaces, such as those from NNPs or quantum calculations, tighter numerical accuracy and stricter gradient thresholds are often required.

Optimizer Benchmarking and Performance Analysis

A recent benchmark study evaluated the performance of L-BFGS, FIRE, Sella, and geomeTRIC when combined with various neural network potentials for optimizing 25 drug-like molecules [7]. The convergence was determined solely by the maximum gradient component (fmax) being below 0.01 eV/Å (~0.231 kcal/mol/Å), with a maximum of 250 steps [7]. The following tables summarize the key quantitative results, which are critical for informed optimizer selection.

Optimization Success Rate and Efficiency

| Optimizer \ Method | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 22 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 24 |

| ASE/FIRE | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Sella | 15 | 24 | 25 | 15 | 25 |

| Sella (internal) | 20 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 25 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 8 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 9 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 25 |

Table 2: Number of successful optimizations (out of 25). AIMNet2 demonstrated robust performance across all optimizers, while performance for other NNPs was highly optimizer-dependent [7].

| Optimizer \ Method | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 108.8 | 99.9 | 1.2 | 112.2 | 120.0 |

| ASE/FIRE | 109.4 | 105.0 | 1.5 | 112.6 | 159.3 |

| Sella | 73.1 | 106.5 | 12.9 | 87.1 | 108.0 |

| Sella (internal) | 23.3 | 14.88 | 1.2 | 16.0 | 13.8 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 182.1 | 158.7 | 13.6 | 175.9 | 195.6 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 11 | 114.1 | 49.7 | 13 | 103.5 |

Table 3: Average number of steps required for successful optimizations. Sella with internal coordinates and L-BFGS with AIMNet2 were among the most efficient [7].

Quality of the Optimized Structures

A critical metric for success is whether the optimizer locates a true local minimum (with no imaginary frequencies) rather than a saddle point.

| Optimizer \ Method | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 16 | 16 | 21 | 18 | 20 |

| ASE/FIRE | 15 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 12 |

| Sella | 11 | 17 | 21 | 8 | 17 |

| Sella (internal) | 15 | 24 | 21 | 17 | 23 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 6 | 8 | 22 | 5 | 7 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 17 | 13 | 1 | 23 |

Table 4: Number of optimized structures that were true local minima (zero imaginary frequencies) [7].

Key Performance Insights

- L-BFGS demonstrates robust performance and high success rates across multiple NNPs, confirming its status as a reliable default choice. The QuantumATK documentation also recommends L-BFGS for its superior performance over FIRE for nearly every optimization problem [32].

- Sella shows a dramatic performance improvement when using internal coordinates, becoming one of the fastest and most reliable optimizers in this benchmark. This highlights the critical importance of coordinate system choice.

- FIRE, while noise-tolerant, often exhibited lower success rates and located fewer true minima compared to L-BFGS and Sella (internal), suggesting it may be less suitable for complex molecular systems [7].

- geomeTRIC performance was highly variable. While generally slower in Cartesian coordinates, its TRIC coordinate system can be very efficient for specific methods like GFN2-xTB, but success is highly potential-dependent [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Geometry Optimization with PySCF

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for optimizing a molecular structure using the PySCF environment, which provides interfaces to both geomeTRIC and PyBerny optimizers [6].

Convergence Control in PySCF/geomeTRIC: The convergence criteria for geomeTRIC in PySCF can be controlled via a dictionary for more precise results [6]:

Protocol 2: Transition State Optimization with geomeTRIC

Locating transition states requires specialized algorithms. This protocol describes how to perform a TS search using geomeTRIC through the PySCF interface [6].

Key Considerations:

- Initial Guess: The success of a TS optimization is highly dependent on the quality of the initial structure, which should be close to the saddle point.

- Hessian: Providing an initial Hessian can significantly improve convergence. In geomeTRIC, this can be enabled by setting

'hessian': Truein the parameters if the underlying method provides analytical Hessians [6]. - Characterization: Always perform a frequency calculation on the optimized TS to confirm exactly one imaginary frequency.

Protocol 3: Optimization with Custom Convergence and Constraints

For advanced applications, custom constraints and convergence thresholds are often necessary.

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for selecting and applying a geometry optimizer, incorporating convergence diagnostics and restart procedures.

Figure 1: Geometry optimization workflow with convergence checking and automatic restart logic for saddle points [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table lists key software tools and "reagents" essential for implementing the protocols discussed in this note.

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| geomeTRIC | General-purpose optimization library using translation-rotation internal coordinates (TRIC). | Molecular and transition state optimizations; supports constraints [6]. |

| Sella | Optimization package for both minima and transition states using internal coordinates. | Particularly efficient for finding local minima when using internal coordinates [7]. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python package for atomistic simulations; includes L-BFGS and FIRE optimizers. | Provides a unified interface for various optimizers and calculators [7]. |

| PySCF | Quantum chemistry package with optimizer interfaces. | Provides Python interfaces to geomeTRIC and PyBerny for ab initio optimizations [6]. |

| AMS | Multiscale modeling platform with detailed convergence control. | Offers configurable convergence criteria and automatic restart features [4]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Surrogate models for rapid energy/force evaluation (e.g., OrbMol, AIMNet2). | Accelerate optimization by replacing expensive quantum calculations [7]. |

Table 5: Essential software tools for geometry optimization workflows.

Based on the benchmark data and practical experience, the following recommendations can guide the selection of optimizers:

- For General-Purpose Molecular Optimization: L-BFGS is a robust and reliable default choice, offering a good balance of success rate and efficiency across diverse chemical systems and in combination with various NNPs [7] [32].

- For Maximum Efficiency with NNPs: Sella with internal coordinates demonstrated superior speed in recent benchmarks. It is an excellent choice when optimization step count is a primary concern [7].

- For Transition State Searches: geomeTRIC or Sella are the recommended tools, as they implement specialized algorithms for locating first-order saddle points [6].

- For Noisy Potential Energy Surfaces or Complex Relaxation: FIRE can be a viable option due to its inherent noise tolerance, though its ability to locate true minima may be lower than that of Hessian-based methods [7].

- Always Verify Results: Regardless of the optimizer, always confirm that a minimum has no imaginary frequencies and that a transition state has exactly one. Utilize automatic restart features (e.g.,

MaxRestartsin AMS) if a saddle point is accidentally found during a minimum search [4].

The interplay between optimizer, convergence criteria, and the underlying PES is complex. The optimal configuration is often system-dependent. The protocols and data provided here offer a foundation for developing efficient and reliable geometry optimization strategies to support robust computational research and drug development.

Configuring Optimizations for Molecules, Periodic Systems, and Transition States

Geometry optimization, the process of finding a stable molecular configuration on the potential energy surface (PES), represents a cornerstone calculation in computational chemistry with profound implications for drug discovery and materials design [33]. The configuration of optimization convergence criteria directly determines the reliability, accuracy, and computational efficiency of these calculations, forming an essential component of any computational research workflow. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate convergence parameters requires balancing numerical precision with practical computational constraints—a decision that varies significantly across different chemical systems including isolated molecules, periodic structures, and transition states [4] [33].

The fundamental challenge in geometry optimization lies in navigating the complex, high-dimensional PES to locate stationary points corresponding to stable molecular structures or reaction pathways [33]. Local optimization methods efficiently locate the nearest local minimum, making them invaluable for refining known structures, but their success hinges upon properly configured convergence criteria that ensure structural stability without excessive computational cost [4]. This technical note establishes comprehensive protocols for configuring these optimizations across diverse chemical contexts, providing researchers with practical guidance grounded in current computational methodologies.

Convergence Criteria Fundamentals

Core Convergence Parameters

Geometry optimization convergence is typically evaluated through multiple complementary criteria that monitor different aspects of the optimization process. According to the AMS documentation, a geometry optimization is considered converged only when all the following conditions are satisfied [4]:

- The energy change between consecutive optimization steps falls below a threshold defined as