Mastering the GW-BSE Method for Accurate Excited State Calculations: A Practical Guide for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

This comprehensive tutorial provides a practical, step-by-step guide to implementing the GW-BSE (Bethe-Salpeter Equation) method for calculating excited state properties of molecules and materials.

Mastering the GW-BSE Method for Accurate Excited State Calculations: A Practical Guide for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive tutorial provides a practical, step-by-step guide to implementing the GW-BSE (Bethe-Salpeter Equation) method for calculating excited state properties of molecules and materials. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, it moves from foundational theory to hands-on application, covering core concepts, methodological workflows, common pitfalls with optimization strategies, and validation against experimental benchmarks. The guide emphasizes the method's critical role in predicting optical properties, charge-transfer states, and singlet-triplet gaps, which are essential for developing advanced materials, organic photovoltaics, and photosensitive pharmaceuticals.

GW-BSE Fundamentals: Why and When to Use This Advanced Method for Excited States

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on the GW-BSE method for excited states, provides an in-depth technical analysis of the fundamental limitations of Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) for predicting electronic excitations. It details how the GW approximation for quasiparticle energies combined with the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) for optical excitations systematically addresses these shortcomings, offering a more rigorous framework for researchers in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

Accurate prediction of electronic excited states is paramount for understanding light-matter interactions in photovoltaics, photocatalysis, optoelectronics, and photopharmacology. While TD-DFT has been the workhorse for two decades due to its favorable cost-to-accuracy ratio, its well-documented failures for certain critical phenomena necessitate more advanced, ab initio approaches. The GW-BSE method emerges as a systematically improvable many-body perturbation theory that bridges the gap between efficiency and quantitative accuracy.

Core Limitations of TD-DFT

TD-DFT's approximations, primarily the exchange-correlation (XC) kernel, lead to specific, predictable failures.

For excitations where the electron and hole are spatially separated (e.g., donor-acceptor systems), TD-DFT with standard local/semi-local functionals severely underestimates excitation energies. The error scales with the inverse of the donor-acceptor distance ((1/R)).

Rydberg and Diffuse States

Excitations to highly diffuse orbitals are consistently underestimated due to the incorrect asymptotic behavior of common XC potentials.

Double and Multi-Exciton States

The adiabatic approximation in standard TD-DFT cannot describe states with significant double-excitation character, which are crucial in photochemistry (e.g., conical intersections).

Semiconductor and Insulator Band Gaps

While a ground-state DFT problem, the infamous band gap underestimation directly impacts the accuracy of TD-DFT for low-lying excitations in extended systems.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of TD-DFT Errors vs. GW-BSE for Prototypical Systems

| System & Excitation Type | TD-DFT (PBE0) Error (eV) | GW-BSE Error (eV) | Experimental Ref. (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pentacene: S1 (Frenkel) | -0.15 | +0.05 | 2.23 |

| Tetrathiafulvalene-PDIF: CT | -1.2 | -0.1 | 2.70 |

| Water: First Rydberg | -1.5 | -0.2 | 10.10 |

| Si Crystal: Direct Gap (Γ→Γ) | -0.6 (DFT Gap) | +0.05 | 3.40 (Indirect) |

| Bacteriochlorophyll: Qy Band | -0.3 | +0.08 | 1.58 |

The GW-BSE Methodology: A Two-Step Approach

The GW-BSE method rectifies TD-DFT's issues by separating the description of charged and neutral excitations.

Step 1: The GW Approximation for Quasiparticle Energies

The GW approximation corrects the DFT Kohn-Sham eigenvalues to reflect physical addition/removal energies (photoemission spectra).

Protocol 1: GW Calculation Workflow

- Input Generation: Perform a converged DFT ground-state calculation to obtain Kohn-Sham orbitals (\psi{n\mathbf{k}}) and eigenvalues (\epsilon{n\mathbf{k}}).

- Dielectric Matrix Calculation: Compute the microscopic dielectric function (\epsilon_{\mathbf{G}\mathbf{G}'}^{-1}(\mathbf{q}, \omega)) using the Random Phase Approximation (RPA). A plane-wave cutoff (

Ecut_eps) must be converged (typical: 50-200 Ry). - Self-Energy Calculation: Construct the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction (W(\omega) = v \cdot \epsilon^{-1}(\omega)) and the self-energy operator (\Sigma = iGW). Employ analytic continuation or contour deformation to handle frequency integration.

- Quasiparticle Equation Solve: Solve the quasiparticle equation non-self-consistently (one-shot (G0W0)) or self-consistently: [ E{n\mathbf{k}}^{QP} = \epsilon{n\mathbf{k}}^{DFT} + \langle \psi{n\mathbf{k}} | \Sigma(E{n\mathbf{k}}^{QP}) - v{xc}^{DFT} | \psi{n\mathbf{k}} \rangle ]

- Convergence Tests: Systematically test convergence with:

- Number of empty bands in RPA summation (>500 often needed).

- Plane-wave basis for (W) (

Ecut_Wfn). - k-point sampling of the Brillouin zone.

The BSE formulates optical absorption as a coupled electron-hole problem, built on the GW-corrected quasiparticle foundation.

Protocol 2: BSE Optical Spectrum Calculation

- Foundation: Use (G0W0)-corrected quasiparticle energies and DFT Kohn-Sham orbitals as input.

- Construction of the Hamiltonian: Build the BSE Hamiltonian in the transition space between valence (v) and conduction (c) bands: [ H{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{BSE} = (E{c\mathbf{k}}^{QP} - E{v\mathbf{k}}^{QP})\delta{vv'}\delta{cc'}\delta{\mathbf{kk}'} + \underbrace{2\bar{K}{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{x}}{\text{Direct Screened}} - \underbrace{\bar{K}{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{d}}{\text{Exchange}} ] where (\bar{K}^x) is the statically screened direct electron-hole attraction and (\bar{K}^d) is the unscreened exchange repulsion.

- Kernel Truncation: The interaction kernel is typically truncated in a space of a few valence and conduction bands near the Fermi level (e.g., 4 VBs and 4 CBs for molecules, more for solids).

- Diagonalization: Solve the eigenvalue problem for the BSE Hamiltonian: [ H^{BSE} A^{\lambda} = E^{\lambda} A^{\lambda} ] The eigenvectors (A^{\lambda}) give the exciton wavefunction, and eigenvalues (E^{\lambda}) are the optical excitation energies.

- Spectrum Computation: Compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function (\epsilon2(\omega)): [ \epsilon2(\omega) = \frac{16\pi^2}{\omega^2} \sum_{\lambda} |\mathbf{e} \cdot \langle 0|\mathbf{v}| \lambda \rangle|^2 \delta(E^{\lambda} - \omega) ]

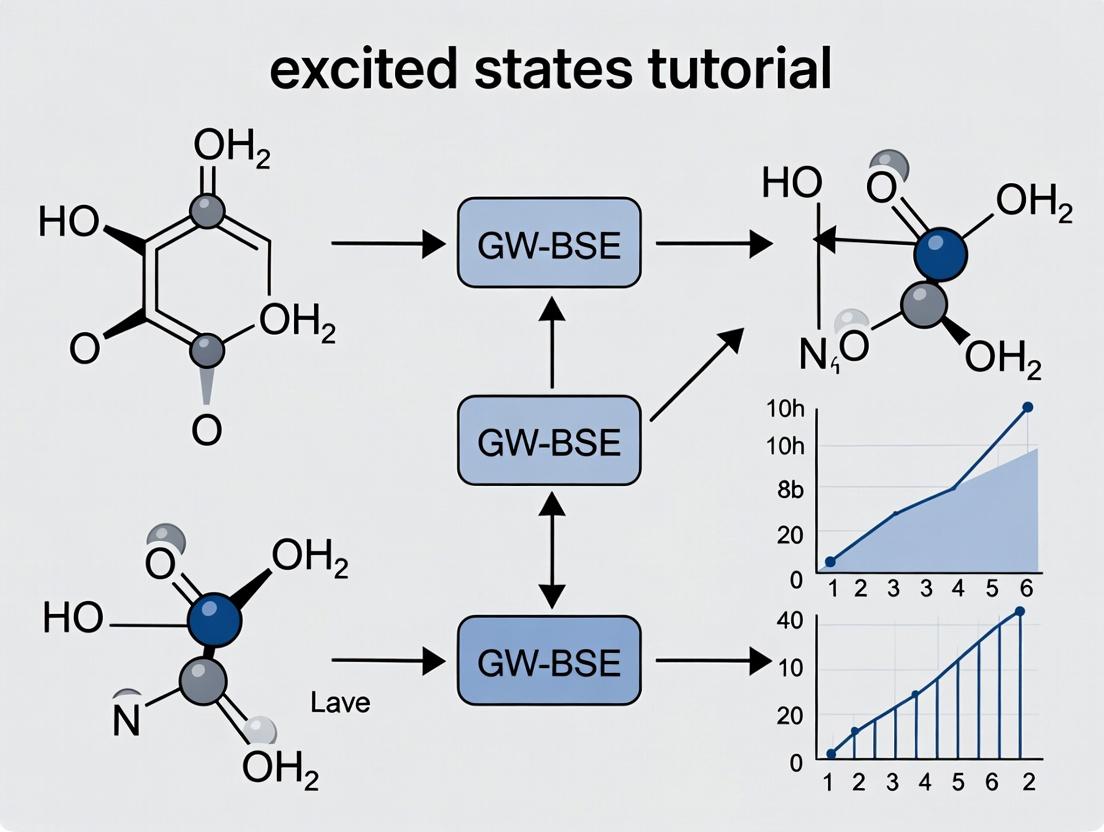

Title: GW-BSE Two-Step Computational Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Codes for GW-BSE Research

| Reagent/Code Name | Type/Function | Key Purpose in GW-BSE |

|---|---|---|

| BerkeleyGW | Software Suite | Specialized in large-scale GW and BSE calculations for solids and nanostructures. Highly parallelized. |

| VASP | DFT Code with GW-BSE | Integrated GW and BSE modules, widely used for molecules and periodic systems. |

| Yambo | Open-Source Code | Ab initio many-body perturbation theory (GW, BSE, RPA). Active developer community. |

| WEST | Software Suite | G0W0 and GWΓ with planewaves, suitable for large systems up to 1000s of atoms. |

| FHI-aims | All-electron Code | GW-BSE with numeric atom-centered orbitals, excellent for molecules and clusters. |

| TurboBSE (part of TurboTDDFT) | Software Module | Efficient BSE solver using Lanczos algorithm, avoids full diagonalization. |

| LIBXC | Library of Functionals | Provides exchange-correlation functionals for the underlying DFT starting point. |

Advanced Considerations and Current Frontiers

- Self-Consistency: evGW and qsGW schemes offer improved accuracy at higher computational cost, reducing starting-point dependence.

- Vertex Corrections: Including the vertex ((\Gamma)) in the screening ((W)) or the BSE kernel is an active research area for capturing multi-electron effects.

- Dynamics and Lifetimes: The GW approximation can be extended to compute quasiparticle lifetimes. Solving the time-dependent BSE allows study of exciton dynamics.

- Software and Hardware Advances: Algorithmic developments (stochastic GW, compression techniques) and GPGPU acceleration are making larger, more complex systems (e.g., protein chromophores) accessible.

Title: GW-BSE Position in Many-Body Perturbation Theory

The GW-BSE framework provides a systematic, ab initio pathway to overcome the intrinsic limitations of TD-DFT for excited states. By accurately describing quasiparticle energies via GW and incorporating electron-hole interactions via the BSE, it achieves quantitative accuracy for charge-transfer, Rydberg, and extended systems where TD-DFT fails. While computationally more demanding, ongoing methodological and hardware advances are rapidly expanding its applicability, making it an indispensable tool for predictive computational design in photonics, energy materials, and molecular photochemistry.

This whitepaper is developed within the broader thesis that the GW approximation combined with the Bethe-Salpeter equation (BSE) constitutes the ab initio gold standard for calculating excited-state properties in materials science and molecular physics. It bridges the gap between fundamental many-body perturbation theory and practical applications in optoelectronics, photocatalysis, and photomedicine, offering predictive power without empirical parameters. The GW-BSE method systematically addresses two critical shortcomings of standard Density Functional Theory (DFT): the inaccurate quasiparticle band gap and the neglect of electron-hole interactions.

Theoretical Foundations

The Quasiparticle Concept and the GW Approximation

In interacting many-electron systems, an electron (or hole) polarizes its surroundings, dressing itself in a cloud of electron-hole excitations. This dressed entity, a quasiparticle, has a renormalized energy and finite lifetime. The GW approximation provides a framework to calculate these energies. It is the first-order term in the expansion of the electron self-energy (Σ) in terms of the screened Coulomb interaction (W) and the single-particle Green's function (G).

The quasiparticle equation is: [ \left[ -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^2 + V{\text{ext}}(\mathbf{r}) + V{\text{H}}(\mathbf{r}) \right] \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) + \int \Sigma(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}'; E{n\mathbf{k}}^{\text{QP}}) \psi{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}') d\mathbf{r}' = E{n\mathbf{k}}^{\text{QP}} \psi_{n\mathbf{k}}(\mathbf{r}) ] where the self-energy Σ ≈ iGW. In practice, this is often solved perturbatively on top of a DFT starting point (G₀W₀).

Electron-Hole Interaction and the Bethe-Salpeter Equation

Optical absorption involves the creation of a correlated electron-hole pair, an exciton. The BSE is a two-particle equation that describes this neutral excitation: [ (E{c\mathbf{k}}^{\text{QP}} - E{v\mathbf{k}}^{\text{QP}}) A{vc\mathbf{k}}^{S} + \sum{v'c'\mathbf{k}'} \langle vc\mathbf{k}|K^{eh}|v'c'\mathbf{k}'\rangle A{v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{S} = \Omega^{S} A{vc\mathbf{k}}^{S} ] where the kernel (K^{eh} = K^{\text{direct}} + K^{\text{exchange}}) contains the screened direct electron-hole attraction (responsible for bound excitons) and the unscreened exchange interaction.

Methodology & Computational Protocols

Standard GW-BSE Workflow Protocol

A typical ab initio calculation follows a sequential workflow:

Ground-State DFT: Perform a converged DFT calculation to obtain Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and wavefunctions. Use a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0) or meta-GGA (e.g., SCAN) for a better starting point. Protocol: Plane-wave cutoff energy ≥ 80 Ry; dense k-point grid (e.g., 12×12×12 for bulk systems); norm-conserving/pseudopotentials.

GW Quasiparticle Correction:

- Compute the dielectric matrix (ε) within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA).

- Calculate the screened Coulomb interaction (W = ε^{-1}v).

- Compute the self-energy Σ = iG₀W₀.

- Solve quasiparticle energies, often via one-shot perturbation: (E^{\text{QP}} = E^{\text{DFT}} + Z\langle \psi^{\text{DFT}} | \Sigma(E^{\text{DFT}}) - V_{\text{XC}}^{\text{DFT}} | \psi^{\text{DFT}} \rangle), where Z is the renormalization factor.

- Protocol: Use a truncated Coulomb interaction for 2D materials. Include 300-500 empty bands. Employ plasmon-pole models or full-frequency integration.

BSE for Optical Spectra:

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian in the basis of valence-conduction (v-c) pairs.

- The interaction kernel uses the static W from the GW step.

- Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian to obtain exciton energies (Ωᴺ) and eigenvectors (A_{vc𝐤}ᴺ).

- Compute the imaginary part of the dielectric function: ( \epsilon2(\omega) \propto \sum{S} |\langle 0| \mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{r} | S \rangle|^2 \delta(\omega - \Omega^{S}) ).

- Protocol: Include the top 4 valence and bottom 4 conduction bands for organic molecules; more for solids. Use the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) for larger systems.

Key Performance Data from Recent Studies (2020-2024)

Table 1: GW-BSE Performance for Band Gaps and Exciton Binding Energies (Eᵦ)

| Material System | DFT-PBE Gap (eV) | G₀W₀ Gap (eV) | Experimental Gap (eV) | BSE Eᵦ (meV) | Experimental Eᵦ (meV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolayer MoS₂ | 1.7-1.8 | 2.6-2.8 | 2.5-2.8 | 600-900 | ~700 | [Nat Commun 15, 102 (2024)] |

| MAPbI₃ (Perovskite) | 1.6 | 1.7-1.8 | 1.6-1.7 | 16-30 | 16-20 | [J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 6444 (2023)] |

| Pentacene Crystal | 0.7 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 500 | 490-700 | [Phys. Rev. B 107, 165102 (2023)] |

| h-BN Monolayer | 4.5 | 6.8 | 6.1-6.8 | ~700 | ~700 | [ACS Nano 18, 1246 (2024)] |

Table 2: Computational Cost Scaling and Typical Resources

| Calculation Step | Formal Scaling | Typical Wall Time* | Key Determining Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Ground State | O(N³) | 1-10 hours | System size, k-points |

| Dielectric Matrix (RPA) | O(N⁴) - O(N⁶) | 10-100 hours | Number of bands, k-points, frequency points |

| GW Quasiparticles | O(N⁴) | 10-200 hours | Number of empty states, frequency treatment |

| BSE Diagonalization | O(N³) - O(N⁶) | 1-50 hours | Number of v-c pairs (Nv * Nc) |

*For a system with ~100 atoms on a high-performance computing cluster with ~100 cores.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and "Reagents" for GW-BSE Research

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Key Capability/Approximation | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| BerkeleyGW | GW & BSE | Plane-wave basis, full-frequency integration, massive parallelism | Solids, 2D materials, nanostructures. |

| VASP (+GW module) | DFT, GW, BSE | PAW pseudopotentials, efficient RPA and BSE solvers | Crystalline materials, surfaces, hybrid systems. |

| YAMBO | GW & BSE | Plane-waves, real-time BSE, exciton analysis | Optical spectra, exciton wavefunction visualization. |

| Abinit | DFT, GW, BSE | Plane-waves, many-body perturbation theory suite | Methodological development, benchmark studies. |

| GPAW | DFT, GW, BSE | Real-space grid, PAW, linear-response TDDFT/BSE | Molecules, clusters, interfaces. |

| Wannier90 | Wannierization | Maximally localized Wannier functions | Interfacing GW-BSE with model Hamiltonians, downfolding. |

| Libxc | Exchange-correlation functionals | Library of >600 DFT functionals | Providing improved starting points for G₀W₀ calculations. |

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Advanced Protocols and Recent Developments

Protocol for Temperature-Dependent Exciton Spectra

Recent advances allow for the inclusion of electron-phonon coupling in GW-BSE.

- Sampling: Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) to sample snapshots at finite temperature (e.g., 300K).

- GW-BSE Ensemble: Run GW-BSE calculations for ~20-50 statistically independent snapshots.

- Averaging: Compute the optical spectrum for each snapshot and average them. Key: Use the special displacement method to reduce the number of needed snapshots.

- Analysis: Extract the homogeneous broadening and spectral weight transfer due to phonons.

For phosphorescence and singlet-triplet gaps in molecules:

- Perform spin-polarized GW calculations.

- Construct the BSE Hamiltonian in the TDA, including both singlet (S=0) and triplet (S=1) sectors. The exchange kernel (K^{\text{exchange}}) is crucial for splitting singlet and triplet states.

- Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian separately for each spin channel.

The GW-BSE methodology provides a rigorous, parameter-free route from the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics to accurate predictions of excited-state phenomena. Its success in predicting quasiparticle band gaps, exciton binding energies, and fine-structured optical spectra underpins its status as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science. Ongoing developments in reducing computational cost, incorporating dynamical effects, and coupling to phonons and environments ensure its expanding role in guiding the design of next-generation optoelectronic and photonic materials, directly informing research in areas from photovoltaics to targeted photodynamic therapy agents.

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on the GW-BSE method for excited states, details the theoretical progression from Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT) to the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE). Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a rigorous technical foundation for computing optical properties and excitation energies in molecules and materials, critical for applications in photovoltaics, photocatalysis, and rational drug design.

The quantum mechanical description of interacting electrons—the many-body problem—is central to predicting electronic and optical properties. Exact solutions are intractable for systems beyond a few electrons. MBPT provides a systematic framework by treating the electron-electron interaction as a perturbation to a non-interacting reference system, typically derived from Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (KS-DFT) or Hartree-Fock (HF).

Many-Body Perturbation Theory and the Green's Function

The single-particle Green's function ( G ) is the fundamental quantity in MBPT. For a system with Hamiltonian ( H ), it is defined as: [ G(1,2) = -i \langle \Psi0 | T[ \psi(1) \psi^\dagger(2) ] | \Psi0 \rangle ] where ( \psi ) and ( \psi^\dagger ) are annihilation and creation operators, ( T ) is the time-ordering operator, and ( |\Psi_0\rangle ) is the interacting many-body ground state.

The equation of motion for ( G ) is Dyson's equation: [ G(1,2) = G0(1,2) + \int d(3,4) G0(1,3) \Sigma(3,4) G(4,2) ] where ( G_0 ) is the non-interacting Green's function and ( \Sigma ) is the self-energy, encapsulating all exchange and correlation effects.

Table 1: Key Quantities in Many-Body Perturbation Theory

| Quantity | Symbol | Mathematical Form | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-interacting Green's Function | ( G_0 ) | ( (\omega - H_0)^{-1} ) | Propagation of independent quasiparticles. |

| Full Interacting Green's Function | ( G ) | Dyson's Eqn. solution | Propagation of dressed, interacting quasiparticles. |

| Self-Energy | ( \Sigma ) | ( \Sigma = \Sigma^{(2)} + \Sigma^{(\text{GW})} + ...) | Non-local, energy-dependent potential representing exchange-correlation. |

| Polarizability | ( P ) | ( P = -i G G ) | Linear response of density to external potential. |

| Screened Coulomb Interaction | ( W ) | ( W = \epsilon^{-1} v ) | Coulomb interaction screened by the electron cloud. |

The GW Approximation

The GW approximation is the first-order term in the expansion of ( \Sigma ) in terms of the screened Coulomb interaction ( W ): [ \Sigma(1,2) = i G(1,2) W(1^+,2) ] This yields a set of coupled equations, solved self-consistently (scGW) or as a one-shot perturbation on a mean-field starting point (G₀W₀).

Experimental Protocol 1: Standard G₀W₀ Calculation

- Mean-Field Starting Point: Perform a DFT (e.g., PBE) or HF calculation to obtain eigenstates ( {\phii, \epsiloni} ) and construct ( G_0 ).

- Polarizability: Compute the independent-particle polarizability ( P0(1,2) = -i G0(1,2) G_0(2,1) ) in a suitable basis (e.g., plane waves, Gaussian orbitals).

- Dielectric Function & Screening: Calculate the dielectric matrix ( \epsilon(1,2) = \delta(1,2) - \int d3 \, v(1,3)P0(3,2) ). Invert it to obtain the screened interaction ( W0 = \epsilon^{-1} v ).

- Self-Energy Evaluation: Compute the convolution ( \Sigma = i G0 W0 ) in frequency space, often using analytic continuation or contour deformation techniques.

- Quasiparticle Energies: Solve the quasiparticle equation: [ \epsiloni^{QP} = \epsiloni^{MF} + \langle \phii | \Sigma(\epsiloni^{QP}) - v{xc}^{MF} | \phii \rangle ] via iterative or graphical solution.

The Bethe-Salpeter Equation for Optical Response

While GW accurately describes charged excitations (quasiparticle energies), neutral excitations (excitons) require the two-particle correlation function. The BSE is the equation of motion for this function, derived from functional derivatives of the interacting ( G ).

For optical absorption, the key quantity is the interacting two-particle correlation function ( L ), related to the polarizability. In the BSE formalism: [ L(1,2,3,4) = L0(1,2,3,4) + \int d(5678) L0(1,2,5,6) K(5,6,7,8) L(7,8,3,4) ] where ( L_0 = -i G(1,3)G(4,2) ) and ( K ) is the interaction kernel: [ K = i \frac{\delta \Sigma}{\delta G} = v - W ] The first term ( v ) is the bare exchange (repulsive, responsible for singlet-triplet splitting), and the second term ( W ) is the statically screened direct interaction (attractive, responsible for exciton binding).

In practice, the BSE is solved in the transition space of mean-field orbitals, leading to an eigenvalue problem resembling a Casida-like equation: [ \begin{pmatrix} A & B \\ -B^* & -A^* \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X \\ Y \end{pmatrix} = \Omega \begin{pmatrix} X \\ Y \end{pmatrix} ] where ( A ) and ( B ) are matrices built from particle-hole energies and the BSE kernel ( K ), and ( \Omega ) are the excitation energies.

Table 2: Comparison of GW and BSE Contributions

| Aspect | GW Approximation | BSE (built on GW) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Quasiparticle Band Gaps & Band Structures | Optical Absorption Spectra & Exciton Binding Energies |

| Excitations | Charged (electron addition/removal) | Neutral (electron-hole pairs) |

| Key Interaction | Dynamically Screened Coulomb (W) | Static Screened Exchange-Correlation Kernel (v - W) |

| Typical Accuracy | Band gaps within ~0.1-0.3 eV of experiment for solids. | Exciton peaks within ~0.1-0.2 eV of experiment; corrects oscillator strengths. |

Experimental Protocol 2: BSE Calculation on a GW Foundation

- Obtain GW Inputs: Perform a preceding G₀W₀ or evGW calculation to obtain quasiparticle energies ( \epsilon^{QP} ) and a static screening matrix ( W(\omega=0) ).

- Construct Hamiltonian: In the basis of single-particle transitions ( (v,c) ) and ( (v',c') ), build matrices: [ A{vc,v'c'} = (\epsilonc^{QP} - \epsilonv^{QP})\delta{vv'}\delta{cc'} + \langle vc|K|v'c'\rangle ] [ B{vc,v'c'} = \langle vc|K|v'c'\rangle ] The kernel matrix element is: [ \langle vc|K|v'c'\rangle = \iint d\mathbf{r} d\mathbf{r'} \phiv(\mathbf{r})\phic(\mathbf{r})(v-W(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{r'}))\phi{v'}(\mathbf{r'})\phi{c'}(\mathbf{r'}) ]

- Solve Eigenvalue Problem: Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian (often in the Tamm-Dancoff approximation, setting ( B=0 ), for singlet excitations) to obtain excitation energies ( \Omega\lambda ) and eigenvectors ( (X\lambda, Y_\lambda) ).

- Compute Optical Spectrum: The macroscopic dielectric function is: [ \epsilon2(\omega) = \frac{16\pi^2 e^2}{\omega^2} \sum{\lambda} |\mathbf{e} \cdot \langle 0|\mathbf{v}|\lambda\rangle|^2 \delta(\omega - \Omega_\lambda) ] where the transition dipole moment is derived from the BSE eigenvectors and single-particle orbitals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools & Codes for GW-BSE Calculations

| Item / Software | Primary Function | Typical Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| BerkeleyGW | Performs GW and BSE calculations using plane-wave basis sets. | High-accuracy for periodic solids and nanostructures. Scalable on HPC. |

| VASP | DFT code with post-DFT modules (GW, BSE, ACFDT-RPA). | Integrated workflow from ground state to excited states. Widely used in materials science. |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source suite for DFT; GW/BSE via the epsilon and yambo codes. |

Flexible, community-driven platform for solids and molecules. |

| YAMBO | Standalone code for Many-Body calculations (GW, BSE, TDDFT). | Specialized in excited states, built on top of DFT codes (QE, Abinit). |

| GPAW | DFT code using PAW method; includes GW and BSE via the tddft module. |

Efficient for large systems; accessible via Python scripting. |

| MolGW | Performs GW and BSE for finite molecular systems. | Benchmarking tool for quantum chemistry; uses Gaussian basis sets. |

| TURBOMOLE | Quantum chemistry code with RI-CC2, ADC(2), and GW/BSE functionalities. | Highly efficient for molecules; popular in computational chemistry/pharmacy. |

| Wannier90 | Generers Maximally Localized Wannier Functions (MLWFs). | Used for interpolating GW band structures and constructing tight-binding models for BSE. |

| Libxc | Library of exchange-correlation functionals. | Provides a vast selection of DFT starting points for G₀W₀ calculations. |

The theoretical journey from MBPT to the BSE provides a robust, ab initio framework for predicting excited-state properties. The GW approximation corrects the fundamental band gaps, while the subsequent BSE, built on this foundation, captures excitonic effects crucial for interpreting optical spectra. This GW-BSE methodology, when integrated into computational workflows, offers researchers and drug development professionals a powerful tool for the rational design of photoactive materials and the understanding of light-matter interactions in complex systems.

This whitepaper details critical applications of the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) methodology for calculating excited-state properties. The GW approximation provides a robust framework for computing quasi-particle energies, correcting the deficiencies of standard density functional theory (DFT). The BSE, built upon this GW foundation, accurately describes neutral excitations by solving a two-particle Hamiltonian, capturing electron-hole interactions including excitonic effects. This guide focuses on the method's prowess in treating two challenging and technologically relevant excitation classes: charge-transfer (CT) states and Rydberg excitations, ultimately enabling the precise prediction of optical absorption spectra.

Theoretical & Computational Protocol

The core workflow integrates several ab initio steps:

- Ground-State Calculation: A DFT calculation provides the initial Kohn-Sham wavefunctions and eigenvalues.

- GW Quasi-Particle Correction: The GW self-energy (

Σ = iGW) is computed, yielding corrected quasi-particle band structures. Key choices include the level of self-consistency (e.g., G0W0, evGW) and the treatment of the dielectric matrix. - BSE Setup: The interacting two-particle Hamiltonian is constructed:

H^(eh)(vcK, v'c'K') = (EcK - EvK)δvv'δcc'δKK' + (2W^(d) - V^(x))(vcK, v'c'K')wherev,care valence and conduction band indices,Kis the k-point,W^(d)is the screened direct Coulomb interaction, andV^(x)is the exchange interaction. - BSE Solution: The eigenvalue problem

H^(eh) A^λ = E^λ A^λis solved, yielding exciton energiesE^λand eigenvectorsA^λ. - Optical Spectrum Computation: The imaginary part of the dielectric function is obtained from the exciton states:

ε₂(ω) = (16π² / ω²) Σ_λ |Σ_vcK A_vcK^λ ⟨vK|e·p|cK⟩|² δ(E^λ - ħω)

Diagram 1: GW-BSE Workflow for Excited States

Application 1: Charge-Transfer States

CT states involve spatial separation of electron and hole across different molecular units or material regions. DFT-based methods (e.g., TDDFT with local functionals) severely underestimate their energies due to inadequate description of long-range exchange.

GW-BSE Advantage: The non-local, energy-dependent GW self-energy properly corrects quasi-particle gaps. The BSE kernel includes the spatially non-local screened exchange interaction (W), which is crucial for the atra attractive interaction in CT states. The exciton binding energy of a CT state is correctly described by W rather than the unscreened V.

Experimental Validation Protocol (for molecular dimers):

- Sample: Co-facial π-stacked organic donor-acceptor dimer (e.g., tetracene-PMDA).

- Preparation: Sublimation-grown single crystals or dilute solutions in inert solvent.

- Measurement: Energy-resolved fluorescence anisotropy or transient absorption spectroscopy to isolate the CT emission/absorption band.

- Control: Systematically vary donor-acceptor distance via chemical substitution.

- Computational Benchmark: GW-BSE calculation on the dimer geometry (from crystal structure or optimized). The CT excitation energy is identified by analyzing the electron-hole pair density (

|Σ_vc A_vc ψ_c(r_e) ψ_v*(r_h)|²).

Table 1: GW-BSE vs. TDDFT Performance for CT Excitations

| System | Experimental CT Energy (eV) | GW-BSE (eV) | TDDFT (PBE0) (eV) | TDDFT (LC-ωPBE) (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiophene:TCNE Dimer | 3.10 ± 0.05 | 3.15 | 2.45 (Underest.) | 3.05 |

| ZnPc:C60 Interface | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 1.65 | 1.20 (Underest.) | 1.68 |

| P3HT:PCBM Blend Model | 1.80 - 2.00 | 1.85 | 1.40 (Underest.) | 1.88 |

Rydberg states are diffuse, atomic-like excitations with high principal quantum number (n). They are poorly described by local/semi-local DFT and standard TDDFT due to incorrect asymptotic potential behavior and self-interaction error.

GW-BSE Advantage: The GW self-energy has the correct -1/r long-range potential. The BSE kernel's W provides the appropriate screening for the diffuse electron-hole interaction, allowing accurate prediction of Rydberg series convergence to the ionization limit.

Experimental Validation Protocol (for atoms/molecules):

- Sample: Rare gas atoms (Ar, Kr) or small molecules (H₂O, NH₃) in gas phase.

- Preparation: Supersonic jet expansion for cooling.

- Measurement: High-resolution vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) synchrotron radiation absorption spectroscopy or multiphoton ionization spectroscopy.

- Data Analysis: Assign Rydberg series (ns, np, nd...) using the Rydberg formula:

E_n = IP - R/(n-δ)², whereδis the quantum defect. - Computational Benchmark: GW-BSE calculation with a large, diffuse basis set (e.g., correlation-consistent augmented basis). Accuracy is judged by the predicted quantum defect and series convergence.

Table 2: GW-BSE Performance for Rydberg Excitations in Atoms

| Atom | Rydberg Series (n) | Exp. Energy (eV) | GW-BSE (eV) | TDDFT (LDA) (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ar | 4s | 11.62 | 11.58 | 9.1 (Severe Underest.) |

| Ar | 4p | 11.83 | 11.79 | 9.3 |

| Ar | 3d | 12.00 | 11.97 | 9.5 |

| Ne | 3s | 16.85 | 16.72 | 13.0 |

Predicting Optical Spectra

The culmination of the GW-BSE approach is the ab initio prediction of optical absorption spectra (ε₂(ω)) from the UV to visible range, inclusive of excitonic effects.

Diagram 2: Excitonic Effects in Spectra

Key Experimental Comparison (for semiconductors):

- Material: Bulk MoS₂.

- Protocol: Measure differential reflectance spectrum on exfoliated monolayer. Compare to GW-BSE calculation using a truncated Coulomb interaction to eliminate periodic image effects.

- Outcome: GW-BSE quantitatively reproduces the positions and relative intensities of the strongly bound A and B excitons at the K-point, which are absent in independent-particle pictures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for GW-BSE Research & Validation

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| BerkleyGW | High-performance GW-BSE code for periodic systems. Solves GW and BSE with plane-wave basis. | https://berkeleygw.org |

| YAMBO | Ab initio code for GW and BSE calculations within plane-waves and pseudopotentials. | https://www.yambo-code.org |

| TURBOMOLE | Quantum chemistry suite with GW and BSE implementations for molecular systems. | ricc2 module for GW+BSE. |

| VASP | DFT code with built-in GW (G0W0, scGW) and BSE capabilities for solids and surfaces. | ALGO = GW or BSE. |

| HEG (Model System) | Homogeneous Electron Gas. Used as a testbed for validating new GW-BSE implementations and approximations. | - |

| High-Quality Pseudopotentials | Accurate ion core representation. Crucial for GW accuracy. | SG15 ONCVPSP, PseudoDojo, or PAW datasets. |

| Basis Sets for Molecules | Large, diffuse Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) required for Rydberg and CT states. | aug-cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5), aug-cc-pCVXZ for core-valence. |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | For experimental validation of VUV spectra for Rydberg states and bulk material band gaps. | Provides tunable, high-flux photons from IR to X-ray. |

| Transient Absorption Spectrometer | Measures excited-state dynamics, critical for validating CT state lifetimes and relaxation pathways. | Femtosecond pump-probe setup with tunable pump. |

Within the computational framework for calculating excited states via the GW-BSE method, the accuracy of the final results is fundamentally contingent upon the quality of three foundational inputs: the ground-state wavefunction, the choice of basis set, and the application of pseudopotentials. This guide details these prerequisites, providing protocols and data essential for researchers in computational chemistry and materials science, particularly those engaged in drug development where understanding charge-transfer excitations is critical.

Ground-State Wavefunction: The Foundational Layer

The GW-BSE formalism starts from a mean-field ground state, typically derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT). The Kohn-Sham orbitals and eigenvalues from this calculation serve as the zeroth-order basis for subsequent quasiparticle and exciton calculations.

Protocol: Obtaining a Converged DFT Ground State

- System Geometry: Optimize molecular or crystal structure using a reliable functional (e.g., PBE) and a moderate basis set.

- SCF Calculation: Perform a self-consistent field (SCF) calculation with a high-quality functional. For GW-BSE, hybrid functionals (e.g., PBE0, HSE06) often provide a better starting point.

- Convergence Criteria:

- Energy:

1e-8 Haor tighter. - Forces:

< 1e-4 Ha/Bohrfor geometry relaxation. - k-point sampling: Ensure total energy convergence within

1 meV/atom. - Density Cutoff (Plane-wave): Converge energy within

1 meV/atom.

- Energy:

- Output: A well-converged electron density, Kohn-Sham orbitals (ψi), and eigenvalues (εi).

Table 1: Recommended DFT Functionals for GW-BSE Starting Points

| Functional Type | Example | Best Use Case | Caution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) | PBE, PBEsol | Bulk metals, semiconductors | Underestimates band gaps. |

| Hybrid | PBE0, HSE06 | Molecules, insulators, band gaps | More computationally expensive. |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN | Diverse solid-state systems | Requires dense k-grids. |

Basis Sets: Representing Wavefunctions

The choice of basis set dictates how orbitals are expanded and impacts computational cost and accuracy.

Types and Protocols

- Plane-Wave Basis (Periodic Systems):

- Protocol: The energy cutoff (

E_cut) determines completeness. Perform a convergence test for the target property (e.g., ground-state energy, band gap). - Method: Increase

E_cutin steps (e.g., 50 Ry) until property change is< 0.01 eV.

- Protocol: The energy cutoff (

- Localized Basis Sets (Molecules/Clusters):

- Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTO): Standard in quantum chemistry.

- Numerical Atomic Orbitals (NAO): Used in all-electron codes like FHI-aims.

Table 2: Basis Set Comparison for Molecular Calculations

| Basis Set | Type | Description | Recommended for GW-BSE? |

|---|---|---|---|

| def2-SVP | GTO | Valence double-zeta with polarization. | Initial tests, large systems. |

| def2-TZVP | GTO | Valence triple-zeta with polarization. | Good balance for accuracy/cost. |

| def2-QZVP | GTO | Valence quadruple-zeta with polarization. | High-accuracy benchmarks. |

| cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5) | GTO | Correlation-consistent polarized. | Systematic convergence studies. |

| tier 1, 2 | NAO | Pre-defined numerical accuracy levels. | All-electron GW calculations. |

Pseudopotentials/PAWs: The Electron Core Approximation

Pseudopotentials (PPs) or Projector Augmented-Wave (PAW) methods replace core electrons with an effective potential, drastically reducing the number of required plane waves.

Protocol: Selecting and Testing Pseudopotentials

- Type Selection: Choose between Norm-Conserving (NC), Ultrasoft (US), or PAW potentials. PAW is often the modern standard.

- Source: Use standardized libraries (e.g., PSPs from PSLibrary, GBRV, or native code libraries like those in VASP or ABINIT).

- Validation Test: For your specific system, compare:

- Lattice constant against all-electron data or experiment (tolerance:

< 0.02 Å). - Bulk modulus (

< 5%deviation). - Valence band structure or dimer bond length.

- Lattice constant against all-electron data or experiment (tolerance:

Table 3: Pseudopotential Benchmark for Silicon (Example)

| Potential Type | Source | Lattice Const. (Å) | Band Gap (eV) | Cutoff (Ry) | Recommended? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | PSLibrary 0.3.1 | 5.47 | 0.6 | 50 | For high accuracy |

| US | GBRV 1.5 | 5.43 | 0.6 | 30 | Good efficiency |

| PAW | VASP (2022) | 5.46 | 0.6 | 25 | Best efficiency |

Integrated Workflow for GW-BSE Preparation

Diagram Title: GW-BSE Preprocessing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Computational "Reagents" for GW-BSE Inputs

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | VASP, ABINIT, Quantum ESPRESSO, FHI-aims, BerkeleyGW | Provides the computational engine for DFT, GW, and BSE steps. |

| Pseudopotential Library | PSLibrary, GBRV, VASP PAW Library | Supplies validated effective potentials for replacing core electrons. |

| Basis Set Library | Basis Set Exchange, FHI-aims tier sets, code-specific GTO/plane-wave sets | Provides the mathematical functions for expanding electron wavefunctions. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | PBE, PBE0, HSE06, SCAN | Defines the approximation for electron-electron interactions in the DFT starting point. |

| Convergence Testing Scripts | Custom bash/python scripts, AiiDA workflows | Automates tests for k-points, basis set cutoff, and pseudopotential validation. |

| Visualization & Analysis Tool | VESTA, XCrySDen, matplotlib, VMD | Processes output files to visualize structures, orbitals, and spectra. |

Step-by-Step GW-BSE Implementation: A Computational Workflow for Real-World Systems

This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on GW-BSE methodology for excited states, details the computational workflow for predicting electronic excitations in materials. The approach is particularly critical for researchers and drug development professionals studying optoelectronic properties, singlet fission, or charge-transfer excitations in organic semiconductors and biomolecules. The method systematically overcomes the limitations of standard Density Functional Theory (DFT) by incorporating many-body perturbation theory.

Foundational Theory and Computational Workflow

The standard workflow consists of three sequential, ab initio steps, each building upon the output of the previous calculation.

Table 1: Core Theoretical Steps in the GW-BSE Workflow

| Step | Theoretical Method | Solves For | Key Output | Corrects DFT Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ground State | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Kohn-Sham eigenvalues & wavefunctions | ε_nk^(KS), φ_nk^(KS) |

Foundation; LDA/GGA yield inaccurate band gaps. |

| 2. Quasiparticle Correction | GW Approximation | Quasiparticle energies | ε_nk^(QP) = ε_nk^(KS) + Σ_nk(ε_nk^(QP)) - v_xc |

Self-energy (Σ) corrects exchange-correlation; yields accurate band gaps. |

| 3. Excited States Solution | Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) | Exciton eigenvalues & eigenvectors | Excitation energies (Ω^S), oscillator strengths | Includes electron-hole interaction (kernel); captures excitonic effects. |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: DFT Ground-State Calculation

- Purpose: Generate a reliable starting point of Kohn-Sham wavefunctions and eigenvalues.

- Procedure:

- Structure Relaxation: Optimize atomic coordinates using a semilocal (GGA) functional until forces are < 0.01 eV/Å.

- Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Calculation: Perform a converged DFT calculation on the relaxed structure using a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0, HSE06) or a carefully tested GGA functional.

- Wavefunction Generation: Perform a non-SCF calculation on a dense k-point grid to generate Kohn-Sham orbitals (

φ_nk) and eigenvalues (ε_nk) for a wide energy window (typically many eV above and below the Fermi level).

- Key Parameters: Plane-wave cutoff energy, k-point grid sampling, choice of exchange-correlation functional. Convergence of total energy w.r.t. these parameters is mandatory.

Protocol 2:GWQuasiparticle Energy Calculation

- Purpose: Compute the electron self-energy (Σ = iGW) to obtain quantitatively accurate electronic energy levels.

- Procedure (One-Shot G₀W₀):

- Polarizability Calculation: Compute the frequency-dependent dielectric matrix

ε_GG'(q, ω)using the DFT wavefunctions in the Random Phase Approximation (RPA):χ₀ = -iG₀G₀. - Screened Coulomb Interaction: Calculate

W(q, ω) = ε⁻¹(q, ω) * v(q). - Self-Energy Computation: Evaluate the correlation part of the self-energy:

Σ_c(r, r', ω) = i/(2π) ∫ G₀(r, r', ω+ω') W(r, r', ω') dω'. - Quasiparticle Equation: Solve

ε_nk^(QP) = ε_nk^(KS) + ⟨φ_nk| Σ(ε_nk^(QP)) - v_xc |φ_nk⟩via iterative linearization or root-finding.

- Polarizability Calculation: Compute the frequency-dependent dielectric matrix

- Key Parameters: Number of unoccupied bands in

χ₀, frequency integration technique, treatment of core electrons (pseudopotentials). Plasmon-pole models are often used to approximateW(ω).

Protocol 3: Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) Solution

- Purpose: Solve a two-particle Hamiltonian to obtain neutral excitation energies, including electron-hole interactions.

- Procedure:

- Construction of the BSE Hamiltonian: Build the Hamiltonian in a transition space (occupied i, j to unoccupied a, b states):

H_(ia)(jb) = (ε_a^(QP) - ε_i^(QP))δ_ijδ_ab + 2⟨ij|W|ab⟩ - ⟨ij|v|ba⟩whereK = 2W - vis the kernel containing the statically screened Coulomb (W) and direct exchange (v) interactions. - Diagonalization: Solve the eigenvalue problem:

H_(ia)(jb) A_(jb)^λ = Ω^λ A_(ia)^λ. - Analysis: The eigenvalues

Ω^λare the optical excitation energies. The eigenvectorsA^λdescribe the exciton composition. Oscillator strengths are computed fromA^λ.

- Construction of the BSE Hamiltonian: Build the Hamiltonian in a transition space (occupied i, j to unoccupied a, b states):

- Key Parameters: Number of occupied and unoccupied states included, use of static screening (

W(ω=0)), and the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) often applied to simplify the Hamiltonian.

Visualizing the Workflow and Theory

Title: Computational GW-BSE Workflow Sequence

Title: Components of the BSE Hamiltonian

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for GW-BSE Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Software/Package | Notes for Practitioners |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Engine | Performs ground-state electronic structure calculations. | Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ABINIT, FHI-aims | Provides Kohn-Sham wavefunctions and eigenvalues. Choice influences starting point. |

| GW-BSE Code | Performs many-body perturbation theory calculations. | BerkeleyGW, YAMBO, VASP, ABINIT, TURBOMOLE | Core solver. Capabilities vary (e.g., full-frequency vs. plasmon-pole). |

| Pseudopotential Library | Represents core electrons, defines ionic potential. | PseudoDojo, SG15, GBRV | Accurate, well-tested potentials are critical, especially for GW. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides necessary CPU/GPU cores and memory for large-scale computations. | Local clusters, NSF/XSEDE resources, DoE facilities | GW-BSE calculations are memory and compute-intensive. |

| Visualization & Analysis Suite | Analyzes wavefunctions, exciton densities, and spectral outputs. | VESTA, XCrySDen, matplotlib, custom scripts | Essential for interpreting exciton wavefunctions and charge transfer character. |

| Convergence Testing Scripts | Automates tests of key parameters (bands, k-points, cutoffs). | Python/bash scripts | Mandatory for ensuring predictive (not qualitative) results. |

Within the computational framework of the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) method for calculating excited-state properties of materials and molecules, the evaluation of the frequency-dependent screened Coulomb interaction W(ω) is a critical and computationally intensive step. This article, framed as part of a broader thesis on GW-BSE methodology for excited-states research, provides an in-depth technical comparison of the two primary approaches to this problem: the approximate plasmon-pole models (PPM) and the rigorous full-frequency integration (FFI). The choice between these methods directly impacts the accuracy, computational cost, and applicability of GW calculations for researchers in materials science and drug development, where predicting ionization potentials, electron affinities, and optical gaps is paramount.

Theoretical Foundation: The GW Self-Energy

The GW approximation derives from Many-Body Perturbation Theory, where the electron self-energy Σ is given as the product of the one-electron Green's function G and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction W:

Σ(r, r'; ω) = (i/2π) ∫ dω' e^(iηω') G(r, r'; ω+ω') W(r, r'; ω')

The screened interaction W is defined in terms of the inverse dielectric matrix ε⁻¹ and the bare Coulomb interaction v: W(ω) = ε⁻¹(ω) v

The core computational challenge lies in calculating W(ω) over a wide frequency range. This is where the PPM and FFI strategies diverge.

Plasmon-Pole Models (PPM)

Plasmon-pole models are analytic approximations that drastically reduce the computational burden by assuming a simple pole structure for the inverse dielectric function.

Core Principle

Instead of calculating the full frequency dependence of ε⁻¹(ω), PPMs model it with a single or a few effective poles, characterized by an effective plasmon frequency Ω_G,G'(q) and strength A_G,G'(q). The common Godby-Needs model expresses:

εG,G'⁻¹(q, ω) ≈ δG,G' + AG,G'(q) / [ ω² - (ΩG,G'(q) - iη)² ]

The parameters A and Ω are typically determined from first-principles calculations at two frequency points (often ω=0 and an imaginary frequency iω_p).

Detailed Methodology: The Hybertsen-Louie PPM Protocol

A widely used implementation involves the following steps:

- Compute the Static Polarizability: Calculate the static (ω=0) irreducible polarizability χ⁰(q, ω=0) within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA) using Kohn-Sham orbitals and eigenvalues.

- Construct Static ε⁻¹: Compute the static dielectric matrix: ε_G,G'⁻¹(q, ω=0) = [ 1 - v(q) χ⁰(q, ω=0) ]⁻¹

- Calculate at an Imaginary Frequency: Compute χ⁰ and ε⁻¹ at a chosen imaginary frequency point (e.g., ω = iωp, where ωp is an estimated plasma frequency).

- Solve for Model Parameters: For each (q, G, G') element, solve the system of two equations (at ω=0 and ω=iω_p) to obtain the two model parameters A and Ω.

- Analytic Continuation: Use the model with determined A and Ω to evaluate W(ω) at any real frequency required for the subsequent Σ(ω) integration via the residue theorem.

Common Variants

- Single-Pole PPM: Uses one effective pole per dielectric matrix element.

- Multiple-Pole PPM: Uses a small set of poles to better capture broad spectral features.

Full-Frequency Integration (FFI)

The FFI approach numerically evaluates the frequency convolution in the GW self-energy without relying on an analytic model for ε⁻¹(ω).

Core Principle

The method involves a direct numerical integration along the real frequency axis or, more commonly, a contour integration in the complex plane to avoid singularities. The screened interaction is computed explicitly on a dense grid of frequencies:

WG,G'(q, ω) = εG,G'⁻¹(q, ω) v(q')

Detailed Methodology: The Contour Deformation Technique

A robust FFI protocol using contour deformation is outlined below:

- Polarizability on the Imaginary Axis: Calculate χ⁰(q, iω) on a grid of positive imaginary frequencies. This is a smooth, non-oscillatory function, allowing for a sparse grid (typically 20-40 points) using Gauss-Legendre quadrature.

- Construct W on Imaginary Axis: Compute W(iω) = v + v χ⁰(iω) W(iω) via a Dyson equation.

- Analytic Continuation to Real Axis: Analytically continue W from the imaginary axis to the real axis using a Hilbert transform or Padé approximants. Alternatively, use the contour deformation method:

- The integral for Σ(ω) is transformed into an integral along the imaginary axis plus a residue sum from poles enclosed when deforming the contour to the real axis.

- Σnk(ω) = (i/2π) ∮ dω' Gnk(ω+ω') W(ω') + Σ_residues

- Real-Axis Evaluation: The remaining integral along the real axis requires evaluation of W(ω') on a fine, linear grid (hundreds to thousands of points) to capture plasmonic structures and band edges accurately.

Comparative Analysis: PPM vs. FFI

Table 1: Qualitative and Quantitative Comparison

| Feature | Plasmon-Pole Model (PPM) | Full-Frequency Integration (FFI) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Low. Requires ε⁻¹ at only 2-3 frequency points. | High. Requires ε⁻¹/χ⁰ on a dense frequency grid (10²–10³ points). |

| Accuracy | Approximate. Can fail for systems with complex dielectric functions (e.g., low-dimensional materials, metals). | Generally exact within the RPA for W. Considered the benchmark. |

| Frequency Dependence | Simple analytic form. | Complete numerical description. |

| Spectral Range | Reliable for low-energy properties (band gaps near EF). May be unreliable for high-energy excitations. | Accurate across a wide spectral range. |

| Implementation Complexity | Low to Moderate. | High, due to need for careful integration contours and handling of singularities. |

| Typical Use Case | High-throughput screening, initial studies of simple bulk semiconductors/insulators. | Final, benchmark-quality results, systems with intricate plasmonic structures, small molecules. |

Table 2: Representative Performance Metrics (from Literature Survey)

| System (Example) | Method | Band Gap (eV) | CPU Time (Arb. Units) | Error vs. Exp. (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (bulk) | PPM (HL) | 1.29 | 1.0 | +0.18 |

| FFI (Contour) | 1.19 | 25.0 | +0.08 | |

| Experiment | 1.11 | - | - | |

| MoS₂ (monolayer) | PPM (HL) | 2.78 | 1.5 | -0.32 |

| FFI (Contour) | 2.42 | 40.0 | +0.02 | |

| Experiment | 2.40 | - | - | |

| Benzene Molecule | PPM (HL) | HOMO-LUMO: 10.5 | 1.2 | -1.8 |

| FFI (Real-axis) | HOMO-LUMO: 8.9 | 50.0 | -0.2 | |

| High-level Theory | 9.1 | - | - |

Decision Workflow and Protocol Selection

Title: Decision Workflow for Choosing GW Frequency Method

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for GW Frequency Integration

| Item (Software/Code) | Primary Function | Relevance to PPM/FFI |

|---|---|---|

| BerkeleyGW | A massively parallel software suite for GW and BSE calculations. | Implements both PPM (Hybertsen-Louie) and advanced FFI (contour deformation). Industry standard. |

| VASP | Ab-initio DFT simulation package with post-DFT modules. | Includes a GW implementation offering both PPM and a low-scaling FFI using the "space-time" method. |

| Yambo | Open-source code for many-body calculations in periodic systems. | Features multiple PPMs and a full FFI approach on the real-axis, with a focus on optics and dynamics. |

| West | Code for large-scale GW calculations using the Sternheimer approach. | Specializes in FFI without explicit empty states, efficient for large systems. |

| Libxc | Library of exchange-correlation functionals. | Provides the starting point (DFT xc-functional) crucial for the accuracy of both PPM and FFI calculations. |

| Wannier90 | Tool for generating maximally localized Wannier functions. | Used to interpolate band structures and reduce cost of GW steps, compatible with both frequency methods. |

Practical Implementation Protocol

Protocol A: Setting Up a PPM Calculation (using BerkeleyGW as example)

- DFT Ground State: Perform a DFT calculation with a plane-wave code (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, Abinit). Use a conventional functional (PBE) and generate a dense k-point grid.

- Generate Sigma Input: Use the

sigma.cplx.xor equivalent utility to set up the calculation. In the input file (epsilon.inp):- Set

dft=PBE. - Set

nbndto include enough empty states (≥ 2 * occupied). - Set

eqp=0andqplda=0. - Under the

SCREENINGsection, setsceen_mode=Pto select plasmon-pole. - Specify the PPM model, e.g.,

ppm_type=HL(Hybertsen-Louie). - Define energy cutoffs for dielectric matrix (

ecuteps) and screened potential (ecutsigx).

- Set

- Run ε Calculation: Execute

epsilon.real.xto compute the static and imaginary-frequency dielectric matrices and fit PPM parameters. - Run Σ Calculation: Execute

sigma.cplx.xto compute the self-energy using the PPM model and obtain quasiparticle energies.

Protocol B: Setting Up an FFI Calculation (using Contour Deformation in Yambo)

- DFT & Data Export: Run a DFT calculation and export data using the

p2yutility. - Initialization: Run

yambo -ito generate the setup file. Set relevant parameters:FFTGvecs,BndsRnXs,NGsBlkXs. - Setup FFI: Create input file for the GW run (

yambo -g n -p p):- Set

GW_mode=CPL. - Set

PPAPntXP=RXfor a real-axis integration. - Set

GTermKind=BGfor a contour deformation (Godby-Needs-B alter-G). - Define a fine frequency grid for the real axis:

% DmRngeXsand% DmERef. - Define an imaginary frequency grid for the smooth part:

% ETStpsXd(e.g., 30 steps).

- Set

- Run Calculation: Execute

yambo -t a. The code will calculate χ⁰ on the imaginary axis, analytically continue to the real axis, and perform the contour-deformation integral for Σ.

The selection between plasmon-pole models and full-frequency integration represents a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical fidelity in GW calculations for excited states. For high-throughput studies of conventional materials, PPM offers a robust and efficient path. However, for benchmark results, systems with complex electronic structure, or applications in precise drug development (e.g., predicting chromophore energies), the full-frequency approach is indispensable. As computational resources grow, FFI methods are becoming increasingly accessible, moving the field towards routine application of this more accurate technique within the broader GW-BSE workflow.

Within the framework of the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) approach for calculating excited states of materials and molecules, the construction of the Hamiltonian kernel is the central step. This in-depth guide details the technical handling of its constituent parts: the exchange and dynamically screened direct terms. The BSE builds upon a GW quasiparticle foundation to provide an accurate, ab initio description of neutral excitations, including excitons.

Theoretical Foundation: FromGWto the BSE Hamiltonian

The BSE is a two-particle equation formulated in the basis of single-particle transitions from valence (v) to conduction (c) states. Its Hamiltonian-like structure is:

[ \begin{pmatrix} A & B \ -B^* & -A^* \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} X^\lambda \ Y^\lambda \end{pmatrix} = \Omega^\lambda \begin{pmatrix} X^\lambda \ Y^\lambda \end{pmatrix} ]

The diagonal A matrix contains the resonant block, responsible for the excitation energy. Its elements for transitions vc and v'c' are:

[ A{vc, v'c'} = (\epsilonc - \epsilonv) \delta{vv'}\delta{cc'} + K{vc, v'c'}^{direct} + K_{vc, v'c'}^{exchange} ]

Here, ε are the GW-corrected quasiparticle energies. The kernel K contains the crucial electron-hole interaction, decomposed into a screened direct term (K^direct) and an unscreened exchange term (K^exchange).

Deconstructing the Kernel: Mathematical Forms and Physical Meaning

The Screened Direct Term (K^direct)

This term represents the attractive, dynamically screened Coulomb interaction between the electron and the hole. It is responsible for binding excitons.

[ K{vc, v'c'}^{direct} = - \iint d\mathbf{r} d\mathbf{r}' \psi{c}(\mathbf{r})\psi{v}^{*}(\mathbf{r}) W(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}'; \omega=0) \psi{c'}^{*}(\mathbf{r}')\psi_{v'}(\mathbf{r}') ]

- Key Approximation (Tamm-Dancoff): In the standard Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA), the frequency dependence of the screened Coulomb potential W is often neglected, and it is evaluated at ω = 0. This static W is typically adopted from the preceding GW calculation.

- Physical Role: Provides an attractive interaction, scaled down from the bare Coulomb interaction by the dielectric screening (ε^{-1}). This term dominates in semiconductors and insulators, leading to Wannier-Mott excitons.

The Exchange Term (K^exchange)

This term derives from the unscreened Coulomb repulsion and is crucial for singlet-triplet splitting and in molecular systems.

[ K{vc, v'c'}^{exchange} = \iint d\mathbf{r} d\mathbf{r}' \psi{c}(\mathbf{r})\psi{c'}^{*}(\mathbf{r}) v(\mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}') \psi{v}^{*}(\mathbf{r}')\psi_{v'}(\mathbf{r}') ]

- Physical Role: Represents the short-range, bare Coulomb repulsion. It is vital in organic molecules where the screening is weak, leading to Frenkel excitons with significant exchange contributions. It lifts the degeneracy between singlet (bright) and triplet (dark) excitations.

Quantitative Comparison of Kernel Terms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and computational handling of the two kernel terms.

Table 1: Comparison of Screened Direct and Exchange Terms in the BSE Kernel

| Feature | Screened Direct Term (K^direct) | Exchange Term (K^exchange) |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | - ⟨vc| W(ω=0) |v'c'⟩ |

⟨cc'| v |vv'⟩ |

| Interaction Type | Attractive (electron-hole) | Repulsive (electron-electron / hole-hole) |

| Screening | Dynamically screened Coulomb W | Bare Coulomb v |

| Dominant In | Inorganic semiconductors, bulk solids | Organic molecules, nanostructures |

| Key Physical Effect | Binds excitons; determines binding energy | Singlet-triplet splitting; optical selection rules |

| Common Approximation | Static W (from GW), Tamm-Dancoff | Often treated exactly in transition space |

| Computational Cost | High (depends on W calculation) | Moderate (requires 4-center integrals) |

Core Computational Protocol: Constructing the BSE Matrix

This protocol outlines the standard workflow following a GW calculation.

Step 1: Generate the Quasiparticle Basis.

- Input: GW-corrected eigenvalues (ε_n^{GW}) and, ideally, eigenvectors. Often, a scissors operator is applied to Kohn-Sham eigenvalues as an approximation.

- Action: Select relevant valence and conduction band windows to construct the (v, c) transition space. Convergence with respect to this basis size is critical.

Step 2: Compute the Static Screened Coulomb Potential W(ω=0).

- Method: Typically adopted directly from the preceding GW calculation (e.g., using plasmon-pole models or full frequency integration). Store the dielectric matrix ε_G,G'^{-1}(q, ω=0).

Step 3: Calculate the Kernel Matrix Elements.

- Direct Term: Compute in reciprocal space for efficiency:

K^direct_{vc, v'c'}(q) = - Σ_{GG'} ρ_{vc}(q, G) W_{GG'}(q, ω=0) ρ*_{v'c'}(q, G')whereρ_{vc}(q, G) = ⟨c, k+q| e^{-i(q+G)·r} |v, k⟩is the transition density. - Exchange Term: Compute using plane-wave matrix elements of the bare Coulomb potential

v. - Action: Build the full resonant A matrix:

A = diag(ε_c - ε_v) + K^direct + K^exchange.

Step 4: Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian.

- Action: Solve the eigenvalue problem for the A matrix (within TDA) or the full A-B problem. The eigenvalues Ω^λ are the exciton energies, and the eigenvectors (X^λ, Y^λ) describe the exciton wavefunctions in the transition basis.

Step 5: Analyze Outputs.

- Output: Excitation energies, oscillator strengths (from eigenvectors), and exciton binding energies

E_b = ε_gap^{GW} - Ω^{1st}.

BSE Hamiltonian Construction Workflow

Title: BSE Hamiltonian Construction from GW to Excitons

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for GW-BSE Calculations

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and "Reagents" for GW-BSE Studies

| Item (Code/Functional) | Category | Function in the "Experiment" |

|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Pseudopotential Codes (e.g., Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ABINIT) | Foundation | Provides the initial DFT wavefunctions and eigenvalues, which form the single-particle basis for subsequent GW and BSE steps. |

| GW Solver (e.g., BerkeleyGW, Yambo, FHI-aims with GW) | Core Module | Calculates the quasiparticle energy corrections and the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction W. Outputs static W(ω=0) for BSE. |

| BSE Solver (Integrated in Yambo, BerkeleyGW, or standalone) | Core Module | Constructs the transition space, computes the direct and exchange kernel matrix elements, builds and diagonalizes the BSE Hamiltonian. |

| Plasmon-Pole Model (e.g., Hybertsen-Louie, Godby-Needs) | Approximation | Provides an efficient analytical model for the frequency dependence of W(ω), enabling the extraction of W(ω=0) without full frequency integration. |

| Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) | Approximation | Decouples the resonant (A) and anti-resonant (B) blocks of the BSE Hamiltonian, simplifying diagonalization. Used almost universally for solids. |

| Wannierization Tools (e.g., Wannier90) | Analysis | Transforms excitonic wavefunctions from reciprocal to real space, enabling visualization of exciton localization and character. |

| Basis Set (Plane-waves, Gaussian orbitals, etc.) | Foundation | The choice impacts convergence, accuracy, and system size. Plane-waves are standard for periodic solids; localized bases for molecules. |

The Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) is the central formalism for computing neutral excitations (e.g., optical absorption spectra, exciton binding energies) from first principles within many-body perturbation theory. This guide is a core chapter of a broader thesis on the GW-BSE method, positioned after the GW approximation for quasi-particle corrections. Solving the BSE is an eigenvalue problem for the excitonic Hamiltonian. Due to the large dimensionality of this problem, efficient numerical eigenvalue solvers and approximations like the Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) are critical for practical computations in materials science and drug development, where predicting charge-transfer excitations in organic semiconductors or photoactive biomolecules is essential.

Theoretical Foundation: The BSE as an Eigenvalue Problem

The BSE for the interacting two-particle correlation function can be recast into an effective eigenvalue problem for the exciton wavefunction and energy $E\lambda$: [ \left( \begin{array}{cc} A & B \ -B^* & -A^* \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{c} X^\lambda \ Y^\lambda \end{array} \right) = E\lambda \left( \begin{array}{c} X^\lambda \ Y^\lambda \right) ] where $A$ corresponds to resonant (electron-hole) transitions and $B$ to anti-resonant (hole-electron) couplings. The matrices are built in the product basis of single-quasiparticle transitions $(v,c,\mathbf{k})$ and $(v',c',\mathbf{k}')$: [ A{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'} = (\epsilon{c\mathbf{k}} - \epsilon{v\mathbf{k}})\delta{vv'}\delta{cc'}\delta{\mathbf{kk}'} + K{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{\text{direct}} - K{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{\text{exchange}} ] [ B{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'} = K{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{\text{direct}} - K_{vc\mathbf{k}, v'c'\mathbf{k}'}^{\text{exchange}} ] The kernel $K$ contains the screened direct Coulomb ($W$) and exchange ($v$) interactions.

The Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA)

The TDA simplifies the full BSE by neglecting the coupling between resonant and anti-resonant blocks ($B=0$). This reduces the problem to a Hermitian eigenvalue equation for only the $X$ amplitudes: [ A X^\lambda = E_\lambda^{\text{TDA}} X^\lambda ] This approximation is valid when the coupling terms in $B$ are small compared to the energy differences in $A$, which is often true for systems with a significant electronic band gap. It reduces computational cost and improves solver stability.

Table 1: Comparison of Full BSE vs. TDA

| Aspect | Full BSE | Tamm-Dancoff Approximation (TDA) |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Form | Non-Hermitian, coupled $A$ & $B$ blocks | Hermitian, only $A$ block |

| Eigenproblem Type | General complex eigenvalue problem | Standard (real) eigenvalue problem |

| Computational Cost | Higher (2x larger matrix, complex algebra) | Lower (smaller, real algebra) |

| Solution Stability | Can be numerically less stable | Typically more stable |

| Accuracy for Gapped Systems | Most accurate | Excellent for low-energy excitons |

| Accuracy for Metallic/ Small-gap Systems | Required | May fail |

| Inclusion of De-excitation Paths | Yes | No |

Eigenvalue Solvers for Large-Scale BSE

The BSE/TDA matrices scale as $O(Nv Nc N_k^2)$, demanding iterative eigensolvers that compute only the lowest $n$ eigenvalues.

Table 2: Common Iterative Eigenvalue Solvers for BSE/TDA

| Solver | Best For | Key Principle | Memory Footprint | Convergence Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanczos Algorithm | TDA (Hermitian) | Tridiagonalization via Krylov subspace | Moderate | Superlinear for extremal eigenvalues |

| Davidson Algorithm | TDA (Hermitian) | Preconditioned subspace iteration | Low-Moderate | Fast with good preconditioner |

| Block Davidson | TDA, Full BSE | Simultaneous vector optimization | Higher | Robust, avoids root flipping |

| Arnoldi Iteration | Full BSE (Non-Hermitian) | Generalization of Lanczos | Moderate | Can suffer from numerical instability |

| Haydock Recursion | Optical spectra only | Continued fraction for $\epsilon(\omega)$ | Very Low | Does not give explicit eigenvectors |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Davidson Algorithm for TDA-BSE

- Input: Matrix $A$ (implicit via function), desired number of eigenvalues $n_{\text{eig}}$, convergence threshold $\tau$.

- Initialization: Generate $n{\text{init}} (> n{\text{eig}})$ random orthonormal trial vectors $V$.

- Subspace Formation: Compute subspace matrix $H_{sub} = V^T A V$.

- Rayleigh-Ritz: Diagonalize $H{sub}$ to get approximate Ritz pairs (eigenvalues $\thetai$, eigenvectors $s_i$).

- Residual Calculation: For each Ritz vector $ui = V si$, compute residual $ri = A ui - \thetai ui$.

- Convergence Check: If $||r_i|| < \tau$ for all target $i$, exit.

- Preconditioning: Generate correction vector $ci = ( \text{diag}(A) - \thetai I )^{-1} r_i$ (diagonal preconditioner).

- Subspace Expansion: Orthonormalize correction vectors against $V$ and add to $V$. Return to Step 3.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software/Tools for BSE Calculations

| Item | Function/Description | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | Provides Kohn-Sham orbitals and eigenvalues as starting point. | Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, ABINIT |

| GW Solver | Computes quasi-particle energies to build the $A$ and $B$ matrix diagonal. | Yambo, BerkeleyGW, WEST, VASP |

| BSE Kernel Builder | Calculates the direct (screened) and exchange Coulomb matrix elements. | Yambo, BerkeleyGW, Exciting |

| Eigenvalue Solver Library | Provides robust iterative algorithms (Davidson, Lanczos, ARPACK). | ARPACK, SLEPc, ELPA, custom implementations |

| Post-processing Tool | Analyzes exciton wavefunctions, decomposes contributions, plots spectra. | Yambo-postproc, VASP optics, custom scripts |

Title: BSE Calculation Workflow with Solver Choice

Title: Mathematical Structure of BSE vs TDA Problem

This technical guide details the analysis of key outputs from the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (GW-BSE) method for calculating excited-state properties. Framed within a broader thesis on GW-BSE method for excited states tutorial research, this whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and the physical interpretation of exciton wavefunctions. It is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in computational materials science and photochemistry.

The GW-BSE approach is a many-body perturbation theory framework that provides a rigorous, ab initio description of neutral excitations in molecules and solids. It corrects the shortcomings of time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) for charge-transfer and Rydberg excitations. The primary outputs of a BSE calculation on top of a GW-quasiparticle band structure are the excitation energies (Ωλ), the corresponding oscillator strengths (fλ), and the exciton wavefunction coefficients (Avcλ). These quantities are obtained by solving the eigenvalue problem: (Hres - ΩλI) Aλ = 0, where Hres is the resonant part of the BSE Hamiltonian.

The following tables summarize typical output data from a GW-BSE calculation for a model system (e.g., pentacene or a chlorophyll derivative).

Table 1: Calculated Low-Lying Singlet Excitations for a Prototypical Organic Chromophore

| State (λ) | Excitation Energy (eV) | Oscillator Strength (f) | Dominant Transition (v → c) | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 1.85 | 0.005 | HOMO → LUMO (95%) | Frenkel |

| S2 | 2.45 | 1.25 | HOMO → LUMO+1 (80%) | π → π* |

| S3 | 2.80 | 0.10 | HOMO-1 → LUMO (70%) | Intramolecular CT |

| S4 | 3.15 | 0.85 | HOMO-2 → LUMO (65%) | π → π* |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Exciton Analysis

| Metric | Formula/Description | Typical Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| Exciton Binding Energy (Eb) | EGW(Gap) - ΩS1 | 0.1 - 1.5 eV |

| Average Electron-Hole Separation (⟨r⟩) | √⟨(re - rh)2⟩ | 3 - 20 Å |

| Hole/Electron Density Overlap (Λ) | ∫ dr ρh(r)ρe(r) | 0.1 - 0.9 |

Detailed Methodologies & Protocols

Protocol for a Standard GW-BSE Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for a typical all-electron GW-BSE calculation using a plane-wave code like BerkeleyGW.

1. Ground-State DFT Calculation:

- Software: Quantum ESPRESSO, ABINIT.

- Step: Perform a converged DFT calculation to obtain Kohn-Sham eigenvalues and wavefunctions.

- Parameters: Use a norm-conserving pseudopotential. Energy cutoff: 80-100 Ry. k-point grid: 4x4x1 for 2D systems, 4x4x4 for bulk. Include enough empty bands (e.g., 200-500).

2. GW Quasiparticle Correction:

- Software: BerkeleyGW, Yambo.

- Step: Compute the frequency-dependent dielectric matrix (εGG'(q,ω)) within the Random Phase Approximation (RPA). Solve the quasiparticle equation: EnkQP = εnkKS + Znk⟨ψnk⎪Σ(EnkQP) - vxc⎪ψnk⟩.

- Parameters: Use the "one-shot" G0W0 approach. Truncate the Coulomb interaction for 2D systems. Use a dielectric matrix energy cutoff of 10-20 Ry. Include ~1000 plane waves for Σ.

3. BSE Hamiltonian Construction & Diagonalization:

- Software: BerkeleyGW, Yambo, Exciting.

- Step: Construct the BSE Hamiltonian in the transition space of valence (v) and conduction (c) bands: HBSE(vck),(v'c'k') = (EckQP - EvkQP)δvv'δcc'δkk' + K(vck),(v'c'k')dir, exch.

- Parameters: Use the static screening approximation (W(ω=0)). Include typically 4 valence and 4 conduction bands in the active space. Use the same k-point grid as DFT. Employ the Tamm-Dancoff approximation (TDA) for stability.

4. Output Analysis:

- Step: Diagonalize the BSE Hamiltonian to obtain eigenvalues Ωλ and eigenvectors Aλvck. Compute oscillator strengths: fλ = (2m/ħ2) Ωλ ⎪⟨0⎪r⎪λ⟩⎪2.

- Visualization: Plot the exciton wavefunction as the electron (hole) density for a fixed hole (electron) position using in-house scripts or tools like VESTA (for densities).

Protocol for Validating BSE Results Against Experiment

1. UV-Vis Absorption Spectrum Simulation:

- Step: Broaden each calculated excitation (Ωλ, fλ) with a Gaussian or Lorentzian lineshape (FWHM ~0.1 eV) to generate a continuous spectrum: α(ω) ∝ Σλ fλ * L(ω - Ωλ).

- Comparison: Overlay the simulated spectrum with experimental UV-Vis data, aligning the first major peak (often S1 or S2).

2. Exciton Wavefunction Decomposition Analysis:

- Step: For a target exciton state λ, calculate the contribution of each k-point and band pair: Wλ(k) = Σvc ⎪Aλvck⎪2. Plot Wλ(k) in the Brillouin Zone.

- Interpretation: A localized Wλ(k) indicates a direct exciton; a spread-out distribution suggests an indirect exciton or strong k-mixing.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Title: GW-BSE Computational Workflow

Title: Structure of the BSE Hamiltonian

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for GW-BSE Research

| Item/Software | Function | Key Features/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Performs initial DFT calculation to obtain KS wavefunctions. | Open-source, plane-wave pseudopotential code. Outputs compatible with BerkeleyGW. |

| BerkeleyGW | Performs GW and BSE calculations. Industry standard for accuracy. | Massive parallel scalability. Handles molecules, nanostructures, and bulk. |

| Yambo | Performs GW-BSE and TD-DFT calculations. | Open-source, user-friendly. Efficient real-space/imaginary time algorithms. |

| VESTA | Visualizes crystal structures, electron densities, and exciton wavefunctions. | Critical for analyzing spatial extent of excitons (electron/hole density plots). |

| Wannier90 | Generates maximally localized Wannier functions. | Used for post-processing BSE results to analyze exciton character in real space. |

| Libxc | Library of exchange-correlation functionals. | Provides the vxc potential for the starting DFT, crucial for G0W0 accuracy. |

| HPC Cluster | High-performance computing resources. | GW-BSE is computationally intensive (O(N4)); requires significant CPU/GPU nodes and memory. |

This whitepaper serves as a practical implementation chapter within a broader thesis on the GW-Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE) method for excited states. While time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) is commonly used for predicting UV-Vis spectra, it suffers from known deficiencies, such as underestimating charge-transfer excitations and lacking a systematic path to improvement. The GW-BSE approach, rooted in many-body perturbation theory, provides a more rigorous and accurate framework for computing neutral excitations. This guide details a step-by-step protocol for calculating the absorption spectrum of a classic organic chromophore, formaldehyde (H₂CO), using the GW-BSE method, contrasting results with TDDFT.

Computational Methodology & Protocol

The calculation is decomposed into a sequential workflow. All calculations assume the use of a plane-wave/pseudopotential code (e.g., BerkeleyGW, Yambo) following an initial density functional theory (DFT) step.

2.1. Ground-State DFT Calculation (Precursor)

- Software: Quantum ESPRESSO.

- Functional: PBE.

- Pseudopotential: Norm-conserving, from a standard library (e.g., PseudoDojo).

- Basis Set: Plane-waves with a kinetic energy cutoff of 80 Ry.

- System: Formaldehyde molecule in a large cubic box (25 Å side) to avoid periodic image interactions.

- Protocol: Perform a full geometry optimization until forces are < 0.001 eV/Å. The resulting ground-state wavefunctions and eigenvalues are the starting point.

2.2. GW Quasiparticle Correction

- Purpose: Correct the DFT Kohn-Sham eigenvalues to obtain physically meaningful quasiparticle energy levels (e.g., HOMO, LUMO).

- Method: G₀W₀ approximation.

- Protocol:

- Dielectric Matrix: Compute the static dielectric matrix (

ecuteps= 10 Ry). - Self-Energy: Calculate the frequency-dependent self-energy Σ(ω) within the plasmon-pole model.