Molecular Similarity Measures: Navigating Chemical Space for Smarter Drug Design

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular similarity measures, a cornerstone concept in modern computational drug discovery.

Molecular Similarity Measures: Navigating Chemical Space for Smarter Drug Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular similarity measures, a cornerstone concept in modern computational drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of chemical space and the similarity-property principle, detailing the evolution from traditional descriptor-based methods to advanced AI-driven representation learning. The content covers key applications in virtual screening, scaffold hopping, and drug repurposing, while also addressing critical challenges such as the similarity paradox, data reliability, and metric selection. By comparing the performance of different similarity approaches against biological ground truths and clinical trial data, this review offers actionable insights for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize their strategies for navigating the vast chemical universe and accelerating the identification of novel therapeutics.

The Principles of Molecular Similarity and the Vastness of Chemical Space

The concept of chemical space provides a foundational framework for modern drug discovery and materials science. In cheminformatics, chemical space is defined as the property space spanned by all possible molecules and chemical compounds that adhere to a given set of construction principles and boundary conditions [1]. This conceptual space contains millions of compounds readily accessible to researchers, serving as a crucial library for methods like molecular docking [1]. The immense scale of theoretical chemical space presents both extraordinary opportunity and significant challenge for scientific exploration.

The size of drug-like chemical space is subject to ongoing debate, with estimates ranging from 10^23 to 10^180 compounds depending on calculation methodologies [2]. A frequently cited middle-ground estimate places the number of synthetically accessible small organic compounds at approximately 10^60 [3] [2]. This astronomical figure is based on molecules containing up to 30 atoms of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur, with a maximum of 4 rings and 10 branch points, while adhering to the molecular weight limit of 500 daltons as suggested by Lipinski's rule of five [1] [3]. To contextualize this scale, 10^60 is double the number of stars estimated in the universe, so large that it might as well be infinite for practical screening purposes [3].

The disconnect between this theoretical vastness and practical limitations is stark. As of October 2024, only 219 million molecules had been assigned Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Numbers, while the ChEMBL Database contained biological activities for approximately 2.4 million distinct molecules [1]. This represents less than a drop of water in the vast ocean of chemical space, highlighting the critical need for intelligent navigation strategies to explore these uncharted territories efficiently [3].

Quantifying the Challenge: From Theoretical to Empirical Spaces

Key Concepts and Definitions

The exploration of chemical space relies on several key concepts that help researchers navigate its complexity:

- Theoretical Chemical Space: The complete set of all possible molecules that could theoretically exist, estimated at 10^60 for drug-like compounds [1] [3] [2]

- Empirical Chemical Space: The subset of theoretically possible compounds that have actually been synthesized or characterized experimentally [1]

- Known Drug Space (KDS): The region of chemical space defined by molecular descriptors of marketed drugs, helping predict boundaries for chemical spaces in drug development [1]

- Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS): Comprises molecules with biological activity—both beneficial and detrimental—spanning drug discovery, agrochemistry, and other domains [4]

- Chemical Multiverse: Refers to the comprehensive analysis of compound data sets through several chemical spaces, each defined by a different set of chemical representations [5]

Comparative Scales of Chemical Space Exploration

Table 1: Comparing Scales of Chemical Space Exploration

| Space Category | Estimated Size | Examples/Resources | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Drug-like Space | 10^60 compounds [3] [2] | GDB-17 (166 billion molecules) [1] | All possible molecules under constraints; computationally explorable |

| Synthesized & Registered | 219 million compounds [1] | CAS Registry | Experimentally confirmed existence |

| Biologically Characterized | 2.4 million compounds [1] | ChEMBL Database | Annotated with bioactivity data |

| Marketed Drugs | Thousands | Known Drug Space (KDS) [1] | Proven therapeutic efficacy and safety |

The Exploration Gap

The disparity between theoretical and empirical chemical spaces creates what is known as the exploration gap. Traditional drug discovery approaches can synthesize and test approximately 1,000 compounds per year for analysis, while advanced computational platforms can evaluate billions of molecules per week through virtual screening [3]. This 6-order magnitude difference in throughput underscores why computational methods have become indispensable for modern chemical space exploration. The challenge lies in developing strategies to navigate this immense space efficiently while maximizing the probability of discovering compounds with desired properties.

Methodological Framework: Mapping the Uncharted

Molecular Representation: The Foundation of Chemical Space

The construction of navigable chemical spaces begins with the fundamental step of molecular representation. Molecules must be translated into mathematical representations that computers can process and compare. The most basic representation is the molecular graph, where atoms are represented as nodes and bonds as edges [6]. This graph-based understanding of organic structure, first introduced approximately 150 years ago, enables the capture of structural elements that generate chemical properties and activity [6].

Molecular fingerprints represent one of the most systematic and broadly used molecular representation methodologies for computational chemistry workflows [7]. These are descriptors of structural features and/or properties within molecules, determined either by predefined features or mathematical descriptors of molecular features [7]. Structurally, molecules are represented with fixed-dimension vectors (most often binary), which can then be compared using distance metrics [7].

Table 2: Major Categories of Molecular Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Category | Key Examples | Representation Method | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substructure-Preserving | PubChem (PC), MACCS, BCI, SMIFP [7] | Predefined library of structural patterns; binary bits indicate presence/absence | Substructure searches, similarity assessment based on structural motifs |

| Linear Path-Based Hashed | Chemical Hashed Fingerprint (CFP) [7] | Exhaustively identifies all linear paths in a molecule up to predefined length | Balanced structural representation, general similarity assessment |

| Radial/Circular | ECFP, FCFP, MHFP, Molprint2D/3D [7] | Iteratively focuses on each heavy atom capturing neighboring features | Activity-based virtual screening, machine learning applications |

| Topological | Atom Pair, Topological Torsion (TT), Daylight [7] | Represents graph distance between atoms/features in the molecule | Larger systems including biomolecules, scaffold hopping |

| Specialized | Pharmacophore, Shape-based (ROCS, USR) [7] | Incorporates 3D structure, physicochemical properties | Target-specific screening, binding affinity prediction |

Similarity Assessment: Quantifying Molecular Relationships

Once molecular fingerprints are generated, similarity metrics provide quantitative measures to compare compounds. The choice of similarity expression significantly influences which compounds are identified as similar [7]. According to the Similarity Principle, compounds with similar structures should have similar properties, though exceptions known as "activity cliffs" exist where similar compounds exhibit drastically different properties [6] [7].

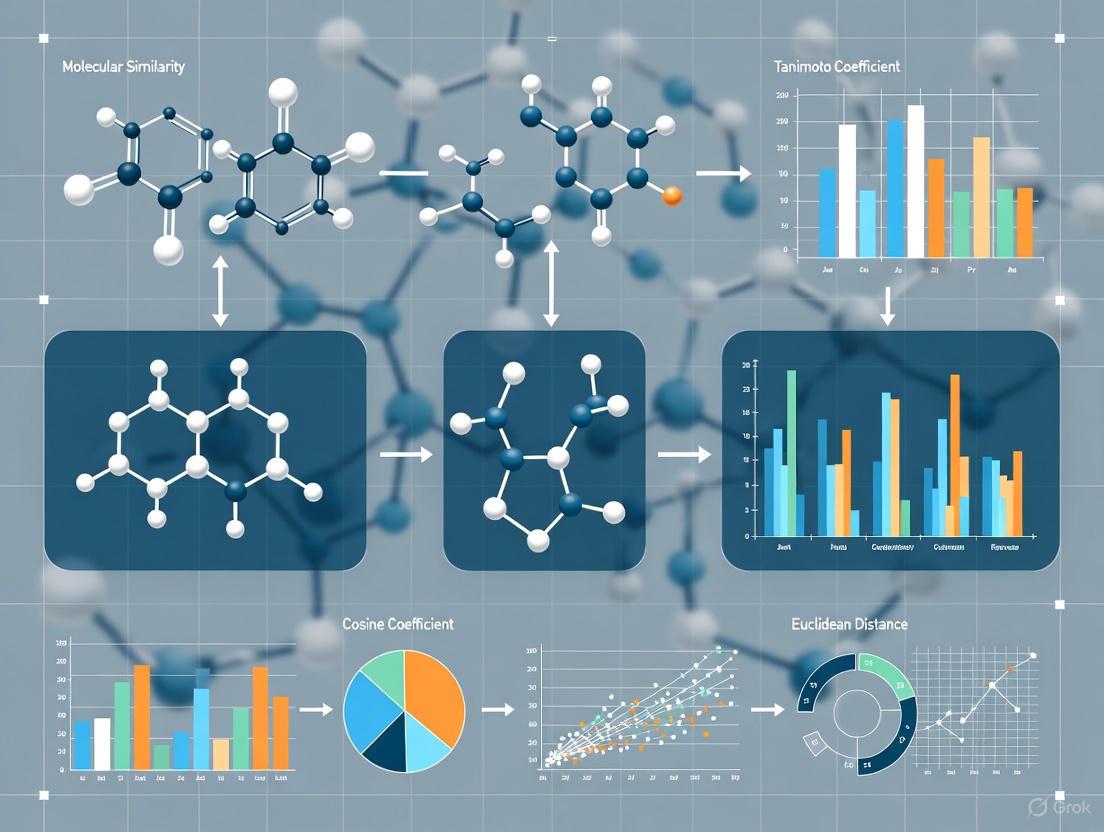

The most commonly used similarity expressions include:

- Tanimoto Coefficient:

T = c/(a + b - c)where a and b are on bits in molecules A and B, and c is common on bits [7] - Euclidean Distance: Straight-line distance between points in multidimensional space [7]

- Dice Coefficient:

2c/(a + b)giving more weight to common features [7] - Cosine Similarity: Measures the cosine of the angle between two vectors [7]

- Tversky Similarity: Asymmetric measure allowing different weights for each molecule [7]

The selection of both fingerprint method and similarity metric should align with the specific goals of the analysis. For instance, structure-preserving fingerprints are preferable when substructure features are important, while feature fingerprints perform better when similar activity is the primary concern [7].

Dimensionality Reduction: Visualizing Multidimensional Spaces

Chemical spaces often comprise hundreds or thousands of dimensions, necessitating dimensionality reduction techniques to create interpretable visualizations. These methods project high-dimensional data into two or three dimensions while preserving as much structural information as possible [8] [5].

Common dimensionality reduction approaches include:

- t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding): Effective for visualizing cluster patterns in high-dimensional data [5]

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis): Linear transformation that identifies directions of maximum variance [5]

- TMAP (Tree MAP): Recently developed algorithm for visual representation of large datasets through distance between clusters and detailed branch structures [9]

- Self-Organizing Maps (SMs): Neural network-based approach that produces low-dimensional representation [5]

- Chemical Space Networks: Graph-based representations where nodes represent compounds and edges represent similarity relationships [5]

These visualization methods enable researchers to identify clusters, outliers, and patterns that might indicate promising regions for further exploration [8].

Experimental Protocols: Practical Approaches to Chemical Space Navigation

Protocol 1: Chemical Space Mapping Using TMAP

Objective: Generate a visual representation of chemical space for a set of compounds using the TMAP algorithm [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound dataset (e.g., from ChEMBL, PubChem, or corporate collection)

- Computing environment with Python/R and necessary libraries

- TMAP implementation (available through public repositories)

- Fingerprint generation tools (RDKit, ChemAxon, or similar)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Curate and standardize molecular structures from source datasets

- Fingerprint Generation: Compute Morgan fingerprints with radius 2 (1024-bits) for each compound [9]

- LSH Forest Indexing: Index fingerprints in a locality-sensitive hashing forest data structure to enable c-approximate k-nearest neighbor search

- MinHash Encoding: Apply MinHash algorithm to encode fingerprints

- Graph Construction: Build undirected weighted c-approximate k-nearest neighbor graph using parameters k=50 and kc=10 [9]

- Visualization: Generate TMAP visualization displaying compound relationships through branch and cluster patterns

Interpretation: In the resulting visualization, closely clustered compounds represent structural neighbors, while branching patterns indicate relationships between clusters. This facilitates identification of scaffold families and activity cliffs [9].

Protocol 2: Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

Objective: Identify potential hit compounds from large chemical libraries using similarity-based approaches [7] [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Reference compound(s) with established desired activity

- Screening library (commercial catalog, corporate database, or public collection)

- Cheminformatics toolkit with fingerprint and similarity calculation capabilities

- High-performance computing resources for large library screening

Procedure:

- Reference Compound Preparation: Select and prepare 1-3 reference compounds with confirmed biological activity and desirable properties

- Fingerprint Selection: Choose appropriate fingerprint method based on screening goals:

- Similarity Threshold Definition: Establish appropriate similarity cutoff (typically Tanimoto >0.6-0.8 for close analogs)

- Library Screening: Compute similarity between reference compound(s) and all library compounds

- Hit Selection: Apply similarity threshold and select top-ranking compounds for further evaluation

- Diversity Assessment: Ensure selected hits cover diverse structural space to avoid redundancy

Interpretation: The resulting hit list provides candidates with high probability of similar activity to the reference compound. These can be prioritized for experimental testing or further computational analysis [7].

Protocol 3: Chemical Space Docking of Ultra-Large Libraries

Objective: Perform structure-based screening of trillion-sized compound collections using Chemical Space Docking approaches [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein target structure (experimental or homology model)

- Ultra-large chemical library (e.g., Enamine's REAL Space)

- Docking software (e.g., SeeSAR, AutoDock, or similar)

- Specialized docking platforms (e.g., BioSolveIT's infiniSee)

Procedure:

- Target Preparation: Prepare protein structure through protonation, optimization, and binding site definition

- Library Access: Access synthetically accessible chemical space (e.g., >20 billion compounds in REAL Space)

- Focused Library Creation: Apply ligand-based or pharmacophore-based filters to create target-focused libraries

- High-Throughput Docking: Perform molecular docking of focused library against target

- Post-Docking Analysis: Analyze binding poses, interaction patterns, and consensus scoring

- Compound Prioritization: Select top-ranking compounds considering both docking scores and synthetic accessibility

Interpretation: This protocol enables exploration of vastly larger chemical spaces than traditional docking, identifying novel chemotypes with predicted binding affinity to the target [10].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Chemical Space Exploration

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, CAS Registry [1] [4] | Source of known compounds with bioactivity data | Publicly available |

| Ultra-Large Screening Libraries | Enamine REAL Space, ZINC [10] [5] | Trillions of synthetically accessible compounds | Commercial and public access |

| Fingerprint Generation | RDKit, ChemAxon, OpenBabel [7] | Molecular representation for similarity calculations | Open source and commercial |

| Chemical Space Visualization | TMAP, t-SNE, PCA implementations [9] [5] | Dimensionality reduction and mapping | Mostly open source |

| Similarity Search Platforms | BioSolveIT infiniSee, OpenEye tools [10] | Navigate large chemical spaces | Commercial |

| Structure-Based Design | SeeSAR, Schrödinger Suite, AutoDock [10] | Docking and interaction analysis | Commercial and academic |

| Specialized Descriptors | MAP4, ECFP, FCFP, Pharmacophore [7] [4] | Molecular representation for specific applications | Various implementations |

Advanced Concepts: Navigating the Chemical Multiverse

The concept of chemical multiverse has emerged as an important framework for comprehensive chemical space analysis. This approach recognizes that unlike physical space, chemical space is not unique—each ensemble of descriptors defines its own chemical space [5]. The chemical multiverse refers to the group of numerical vectors that describe the same set of molecules using different types of descriptors, acknowledging that no single representation can capture all relevant aspects of molecular similarity [5].

Implementing a Multiverse Analysis

Protocol: Comprehensive Chemical Multiverse Assessment

- Multiple Representation Generation: Calculate at least three different descriptor types for the target compound set (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS keys, and MAP4 fingerprint)

- Individual Space Construction: Build separate chemical spaces for each descriptor set using dimensionality reduction

- Comparative Analysis: Identify consistent patterns and discrepancies across different chemical spaces

- Consensus Scoring: Develop integrated metrics that combine information from multiple representations

- Visualization: Create parallel coordinate plots or other multiview visualizations to showcase the multiverse

Applications: The chemical multiverse approach is particularly valuable for challenging tasks such as scaffold hopping, where different descriptor types may capture complementary aspects of molecular similarity, and for complex target classes where multiple interaction modes are possible [5].

The journey from 10^60 theoretical possibilities to navigable chemical regions represents one of the most significant challenges and opportunities in modern drug discovery. By implementing the methodologies and protocols outlined in this application note—from molecular fingerprinting and similarity assessment to advanced chemical multiverse analysis—researchers can transform the impossibly vast chemical space into strategically navigable territories. The integration of computational efficiency with chemical intelligence enables meaningful exploration of previously inaccessible regions, dramatically increasing the probability of discovering novel bioactive compounds with desired properties.

As chemical space exploration continues to evolve, emerging approaches including deep learning-based representation learning [8], integrated biological descriptor spaces [4], and automated multiverse analysis [5] will further enhance our ability to map the uncharted regions of chemical space. These advances promise to accelerate the discovery of new therapeutic agents while providing deeper insights into the fundamental relationships between molecular structure and biological function.

The Similarity-Property Principle (SPP) is a foundational concept in cheminformatics and medicinal chemistry which posits that structurally similar molecules tend to exhibit similar properties [11] [12]. This principle underpins much of modern drug discovery and chemical research, serving as the theoretical basis for predicting the behavior of novel compounds without exhaustive experimental testing. The most frequent application and validation of this principle lies in the realm of biological activity, where structurally similar compounds are expected to display similar activities against pharmaceutical targets [13] [14]. However, the principle extends beyond biological activity to encompass physical properties such as boiling points, solubility, and other physicochemical characteristics [11].

The origins of this concept are deeply rooted in medicinal chemistry practice, though it was formally articulated in the context of computational approaches. A seminal 1990 book, Concepts and Applications of Molecular Similarity, is often cited as the locus where the "similarity property principle emerged" [13]. As noted in historical analyses, the editors Johnson and Maggiora did not claim to invent the concept but sought to unify scattered research and establish a rigorous mathematical and conceptual footing for the pervasive idea that "similar compounds have similar properties" [13] [12]. This principle provides the logical foundation for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships (QSPR), which use statistical models to relate molecular descriptors to observed biological or physical properties [11].

Fundamental Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Defining Molecular Similarity

Molecular similarity is a subjective and multifaceted concept, inherently dependent on the context and the chosen method of quantification [15]. At its core, assessing similarity requires answering two questions: "What is being compared?" and "How is that comparison quantified?" [15]. Molecules can be perceived as similar through different "filters" or perspectives, including their two-dimensional (2D) structural connectivity, three-dimensional (3D) shape, surface physicochemical properties, or specific pharmacophore patterns [15].

- 2D-Structure Similarity: This is one of the most straightforward approaches, comparing molecules based on their atomic connectivity and bonding patterns. Chemists, being familiar with structural formulas, can readily identify analogs with similar 2D scaffolds [15].

- Shape Similarity: Molecular shape is a critical determinant of biological activity. In some cases, molecules with divergent 2D structures can adopt similar 3D conformations, leading to similar biological profiles [15].

- Surface Physicochemical Similarity: Properties such as atomic charges, electrostatic potentials, and hydrophobicity, represented on the molecular surface, directly influence interactions with biological targets. Similar surface properties can result in similar activities even among structurally diverse compounds [15].

- Pharmacophore Similarity: A pharmacophore defines the essential 3D arrangement of functional features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions) responsible for a ligand's biological activity. Comparing molecules based on their pharmacophore patterns focuses on these critical interaction elements, often revealing similarities between otherwise distinct scaffolds [15].

The Chemical Space Paradigm

The concept of chemical space provides a powerful framework for understanding and applying the Similarity-Property Principle [16]. Chemical space can be conceptualized as a multidimensional landscape where each molecule occupies a unique position, and the distance between molecules represents their degree of similarity [16]. In this paradigm, the Similarity-Property Principle translates to the observation that molecules located close together in this space will likely share similar properties.

The sheer vastness of chemical space, estimated to contain up to 10⁶⁰ small molecules, makes comprehensive experimental exploration impossible [16] [17]. Cheminformatics tools, particularly molecular fingerprints and similarity metrics, allow researchers to navigate this space efficiently, identifying promising regions for exploration based on the principle that neighborhoods of interesting molecules are likely to contain other interesting compounds [16]. This approach transforms the search for new drugs or materials from a blind hunt into an informed exploration of chemical lands of opportunity [16].

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery

The Similarity-Property Principle is the engine behind several critical workflows in modern drug discovery. Its application enables more efficient and targeted research and development.

Table 1: Key Drug Discovery Applications of the Similarity-Property Principle

| Application | Description | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based Virtual Screening [15] [12] | Identifying potential active compounds in large databases by their similarity to a known active molecule. | Accelerates hit identification without requiring target structure information. |

| Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis [7] | Systematically modifying a lead compound's structure and analyzing how changes affect biological activity. | Guides lead optimization by highlighting structural features critical for activity. |

| Bioisosteric Replacement [15] | Replacing a functional group with another that has similar physicochemical properties and biological activity. | Improves drug properties (e.g., metabolic stability, solubility) while maintaining efficacy. |

| Chemical Space Exploration [16] [4] | Mapping and analyzing collections of molecules to understand coverage, diversity, and identify unexplored regions. | Informs library design and target selection, helping to prioritize novel chemistries. |

| Scaffold Hopping [12] | Discovering new chemotypes (core structures) with similar biological activity to a known active. | Identifies novel patent space and can overcome limitations of original scaffold. |

Virtual Screening and Similarity Searching

Virtual screening is one of the most direct applications of the SPP. The underlying assumption is that molecules structurally similar to a known active compound are likely to share its biological activity [12]. This ligand-based approach involves searching large chemical databases using a query compound and a computational similarity measure. The output is a ranked list of "hits" deemed most similar to the query, which are then prioritized for experimental testing [15] [7]. This method is particularly valuable when the 3D structure of the biological target is unknown.

Structure-Activity Relationships and Activity Cliffs

In lead optimization, medicinal chemists systematically create and test analogs of a lead compound. The SPP guides the expectation that small, incremental structural changes will lead to small, incremental changes in potency or other properties [7]. Analyzing these Structure-Activity Relationships allows chemists to deduce which parts of the molecule are essential for activity (the pharmacophore) and which can be altered to improve other properties like solubility or metabolic stability.

Deviations from the SPP, known as activity cliffs, are equally informative. An activity cliff occurs when a small structural modification results in a dramatic change in biological activity [7]. Identifying such cliffs reveals that the modified region is critically important for the target interaction, providing key insights for further design.

Quantitative Methods and Experimental Protocols

Molecular Fingerprints and Similarity Metrics

To computationally apply the SPP, molecules must be translated into a numerical representation. Molecular fingerprints are the most common solution—they are fixed-length bit vectors that encode a molecule's structural or functional features [7].

Table 2: Common Types of Molecular Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Type | Description | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Substructure-Preserving (e.g., MACCS, PubChem) [7] | A predefined library of structural patterns; each bit indicates the presence or absence of a specific pattern. | Substructure searching, rapid similarity assessment. |

| Hashed Path-Based (e.g., Daylight, CFP) [7] | Enumerates all linear paths or branched subgraphs up to a certain length; hashed into a fixed-length bit vector. | General-purpose similarity searching, especially for close analogs. |

| Circular (e.g., ECFP, FCFP) [14] [7] | Starts from each atom and iteratively captures circular neighborhoods of a given diameter. Excellent for capturing "functional environments". | Ligand-based virtual screening, SAR analysis, machine learning. |

| Topological (e.g., Atom Pairs, Topological Torsions) [14] [7] | Encodes the topological distance between features or atoms in the molecular graph. | Virtual screening, and particularly effective for ranking very close analogues [14]. |

Once fingerprints are generated, a similarity metric is used to quantify the resemblance between two molecules. The Tanimoto coefficient is the most widely used metric for binary fingerprints [7] [12]. It is calculated as:

T = c / (a + b - c)

where c is the number of bits common to both molecules, and a and b are the number of bits set in molecules A and B, respectively. The Tanimoto coefficient ranges from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical fingerprints). While a common rule of thumb is that compounds with T > 0.85 are similar, this is a simplification, and the optimal threshold can vary significantly depending on the fingerprint and context [12].

Benchmarking Fingerprint Performance

Selecting the right fingerprint is critical, as performance is context-dependent. A 2016 benchmark study using real-world medicinal chemistry data from ChEMBL provides guidance [14]. The study created two benchmarks: one for ranking very close analogs and another for ranking more diverse structures.

Table 3: Fingerprint Performance in Benchmark Studies [14]

| Similarity Context | High-Performing Fingerprints | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ranking Diverse Structures (Virtual Screening) | ECFP4, ECFP6, Topological Torsions | ECFP fingerprints performed significantly better when the bit-vector length was increased from 1,024 to 16,384. |

| Ranking Very Close Analogues | Atom Pair Fingerprint | The Atom Pair fingerprint outperformed others in this specific task. |

Protocol: Conducting a Similarity-Based Virtual Screen

- Define Query: Select a known active compound with desirable properties as the query molecule.

- Select Database: Choose a chemical database (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL, an in-house corporate library) to screen.

- Generate Representations:

- Generate molecular fingerprints for both the query and every molecule in the database. Common choices include ECFP4 or ECFP6 with a sufficiently long bit-length (e.g., 16,384) [14].

- Ensure standardized representation (e.g., neutralize charges, remove counterions) prior to fingerprint generation.

- Calculate Similarity:

- For each database molecule, calculate its similarity to the query molecule using the Tanimoto coefficient and the chosen fingerprint.

- Rank and Analyze:

- Rank the entire database in descending order of similarity score.

- Visually inspect the top-ranked hits (e.g., 100-1000 compounds) to confirm structural reasonableness.

- Experimental Validation:

- Procure or synthesize the top-ranked compounds.

- Test them in a relevant biological assay to confirm activity.

Virtual Screening Workflow

Table 4: Essential Resources for Molecular Similarity Research

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [14] [4] | Public Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing binding, functional and ADMET information. Essential for training and benchmarking. |

| PubChem [4] [12] | Public Database | A vast repository of chemical substances and their biological activities, providing a key resource for similarity searching and data mining. |

| RDKit [14] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | An open-source software suite for cheminformatics and machine learning. Used for generating fingerprints, calculating similarity, and molecular visualization. |

| ECFP/FCFP Fingerprints [14] [7] | Computational Descriptor | The standard vector representations for molecules in many drug discovery tasks, enabling quantitative similarity assessment and machine learning. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient [7] [12] | Similarity Metric | The most prevalent mathematical measure for comparing binary molecular fingerprints and ranking compounds by structural similarity. |

| Enamine REAL Space [17] | Commercial Database | A vast collection of easily synthesizable compounds, representing a large region of commercially accessible chemical space for virtual screening. |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

Limitations and Exceptions to the Principle

The Similarity-Property Principle is a guiding heuristic, not an immutable law. Its most notable exceptions are activity cliffs, where minimal structural changes lead to drastic activity differences [14]. Furthermore, the principle's applicability depends on the chosen representation of similarity. Two molecules may be similar in one descriptor space (e.g., 2D structure) but dissimilar in another (e.g., 3D shape), leading to different property predictions [15]. This underscores that no single, "absolute" measure of molecular similarity exists; it is always a tunable tool that must be adapted to the specific problem [18].

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Foundation Models

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of advanced AI. Foundation models like MIST (Molecular Insight SMILES Transformers) represent a paradigm shift [17]. These models are pre-trained on massive, unlabeled datasets of molecular structures (e.g., billions of molecules) to learn generalizable representations of chemistry. They can then be fine-tuned with small labeled datasets to predict a wide range of properties with high accuracy [17]. This approach leverages a generalized understanding of chemical space, moving beyond traditional fingerprints to capture deeper patterns that underlie the Similarity-Property Principle, potentially enabling more robust predictions for novel chemotypes.

Exploring Underexplored Chemical Space

Most cheminformatics tools and historical data are biased toward small, organic, drug-like molecules. Significant regions of chemical space remain underexplored, including metal-containing compounds, macrocycles, peptides, and PROTACs [4]. Applying the SPP to these areas requires developing new, universal molecular descriptors that can handle their structural complexity [4]. Initiatives to characterize the Biologically Relevant Chemical Space (BioReCS) aim to map these territories, integrating diverse compound classes to fully leverage the SPP for innovative drug discovery [4].

Molecular similarity provides the foundational framework for modern computational drug discovery, extending far beyond simple structural comparisons to encompass a multi-faceted paradigm including shape, pharmacophore features, and even biological outcomes such as side effects. This holistic approach enables researchers to navigate chemical space more efficiently, identifying promising therapeutic candidates while anticipating potential liabilities earlier in the development process. The evolution from structure-based to effect-aware similarity measures represents a paradigm shift in medicinal chemistry, allowing for the design of compounds with optimized efficacy and safety profiles [19] [20].

The concept of molecular similarity has become particularly crucial in the current data-intensive era of chemical research, where it serves as the backbone for many machine learning procedures and chemical space exploration initiatives [19]. By integrating multiple dimensions of similarity, researchers can develop more predictive models and make more informed decisions throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from initial hit identification to lead optimization and beyond.

Multi-faceted Similarity Approaches in Drug Design

2D Molecular Similarity

2D similarity methods, based on molecular fingerprints and topological descriptors, remain workhorse tools for rapid virtual screening and chemical space analysis. These approaches leverage structural frameworks and atomic connectivity patterns to identify potential lead compounds. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a powerful application of 2D similarity, where molecular descriptors including SlogP, molar refractivity, molecular weight, atomic polarizability, polar surface area, and van der Waals volume are correlated with biological activity [21].

In practice, 2D-QSAR models are constructed using training sets of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ values). The resulting models can predict activities for novel compounds and identify key descriptors governing selectivity and potency. These descriptors prove invaluable for predicting activity enhancement during lead optimization campaigns [21]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) further aids in visualizing and interpreting these descriptor relationships within chemical space.

3D Shape and Electrostatic Similarity

3D similarity methods incorporate molecular shape and electrostatic properties, providing a more physiologically relevant representation of molecular interactions. Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA) represents one advanced 3D-QSAR approach that effectively predicts activity using shape and electrostatic potential fields [22]. These methods recognize that molecules with similar shapes and electrostatic characteristics often share similar biological activities, even in the absence of obvious 2D structural similarity.

Molecular docking simulations extend 3D similarity principles by evaluating complementarity between ligands and target proteins. These approaches assess binding modes and affinities, providing atomic-level insights into molecular recognition events. For instance, docking studies with cyclophilin D (CypD) have successfully identified novel inhibitors by evaluating their binding orientations and scores within the predicted binding domain [21].

Pharmacophore Similarity

Pharmacophore modeling captures the essential molecular features responsible for biological activity, including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, aromatic centers, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups. Ligand-based pharmacophore generation involves creating queries from active molecules and screening compound databases to identify those sharing critical pharmacophore elements [21] [22].

Studies on indole-based aromatase inhibitors demonstrated that optimal activity requires one hydrogen bond acceptor and three aromatic rings, providing a clear template for designing novel inhibitors [22]. Similarly, CypD inhibitor development utilized pharmacophore queries to separate active compounds from inactive ones in screening databases [21]. The emerging concept of the "informacophore" extends traditional pharmacophore thinking by incorporating data-driven insights from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations [20].

Side Effect and Phenotypic Similarity

Beyond target-focused approaches, similarity based on side effect profiles and phenotypic responses provides valuable insights for drug safety assessment and repurposing opportunities. This effect-based similarity recognizes that compounds producing similar phenotypic outcomes or adverse effect profiles may share common mechanisms of action or off-target interactions.

The importance of biological functional assays in validating computational predictions underscores the value of phenotypic similarity measures [20]. These assays provide empirical data on compound behavior in biological systems, creating feedback loops that refine computational models and guide structural optimization. Case studies like baricitinib, halicin, and vemurafenib demonstrate how computational predictions require experimental validation through appropriate functional assays to confirm therapeutic potential [20].

Quantitative Comparison of Similarity Methods

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Similarity Approaches

| Similarity Type | Key Descriptors/Features | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Similarity | Molecular fingerprints, SlogP, molar refractivity, molecular weight, polar surface area [21] | Virtual screening, QSAR, scaffold hopping [21] [20] | Fast computation, easily interpretable, works with 2D structures | Misses 3D effects, limited to structural analogs |

| 3D Shape Similarity | Molecular shape, steric fields, electrostatic potentials [22] | 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, scaffold hopping [21] [22] | Captures shape complementarity, identifies non-obvious similarities | Conformational flexibility, computational cost |

| Pharmacophore Similarity | H-bond donors/acceptors, aromatic centers, hydrophobic centroids [21] [22] | Pharmacophore screening, lead optimization [21] [22] | Feature-based rather than structure-based, target mechanism insight | Dependent on conformation, may miss key interactions |

| Side Effect Similarity | Adverse event profiles, phenotypic responses [20] | Safety assessment, drug repurposing, polypharmacology [20] | Clinical relevance, accounts for complex biology | Limited by available data, complex interpretation |

Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive Protocol for 2D-QSAR and 3D Pharmacophore Modeling

Application Note: This protocol describes the integrated application of 2D-QSAR and 3D pharmacophore modeling for the design of Cyclophilin D (CypD) inhibitors as potential Alzheimer's disease therapeutics [21].

Materials and Software:

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software suite

- Training set of 40 compounds with known IC₅₀ values against CypD

- Test set of 20 newly designed compounds based on pyrimidine and sulfonamide scaffolds

Procedure:

Compound Preparation and Energy Minimization

- Build 3D models for all compounds in both training and test sets

- Energy minimize structures to an RMS gradient of 0.01 kcal/mol and RMS distance of 0.1 Å using MMFF94x force field

2D-QSAR Model Development

- Calculate molecular descriptors for training set compounds including SlogP, density, molar refractivity, molecular weight, atomic polarizability, logP(o/w), logS, polar surface area, van der Waals volume, and radius of gyration

- Set $PRED descriptor as dependent variable and activity field

- Perform regression analysis to derive RMSE and R² values from the fit of $PRED values vs SlogP

- Apply QSAR model to predict activities of test set compounds

- Eliminate outliers with Z-score above 1.5 from correlation plot

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) using first three components (PCA1, PCA2, PCA3) to visualize descriptor relationships

Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Generate pharmacophore query from training set molecules considering annotation points: aromatic centers, H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centroids

- Search query against test set molecule database to identify compounds with similar pharmacophore features

- Refine query by excluding external volumes not matching the query

- Align test set conformations with similar pharmacophore models for visualization

Molecular Docking Validation

- Obtain CypD 3D coordinates (PDB ID: 2BIT) and prepare protein structure by removing water molecules/heteroatoms and adding polar hydrogens

- Energy minimize CypD structure in MMFF94x force field to RMS gradient of 0.05

- Perform 10 ns molecular dynamics simulations at 300 K

- Identify binding residues (His 54, Arg 55, Phe 60, Gln 111, Phe 113, Trp 121) through similarity search against PDB

- Dock test set compounds into predicted binding domain, generating 30 conformations per molecule

- Select conformation with lowest docking score to study binding orientations

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables prediction of CypD inhibitory activity for novel compounds and identification of key structural features responsible for binding affinity and selectivity. The integrated approach has successfully identified promising candidates satisfying Lipinski's rule-of-five while maintaining potent inhibitory activity [21].

Protocol for SOMFA-Based 3D-QSAR and Pharmacophore Mapping of Aromatase Inhibitors

Application Note: This protocol details the combined use of SOMFA-based 3D-QSAR, pharmacophore mapping, and molecular docking for identifying binding modes and key pharmacophoric features of indole-based aromatase inhibitors for ER+ breast cancer treatment [22].

Materials and Software:

- Molecular docking software

- SOMFA-based 3D-QSAR implementation

- Pharmacophore mapping tools

- MD-simulation capabilities (100 ns)

Procedure:

Molecular Docking Studies

- Dock most potent compound (compound 4) into aromatase binding pocket

- Compare binding affinity with reference compound (letrozole)

- Analyze binding modes and interactions

SOMFA-Based 3D-QSAR Model Development

- Develop 3D-QSAR model using shape and electrostatic potential fields

- Validate model effectiveness in predicting activity

- Correlate field features with biological activity

Pharmacophore Mapping

- Identify essential pharmacophoric features: one hydrogen bond acceptor (A) and three aromatic rings (R)

- Confirm these features as essential for optimum aromatase inhibitory activity

Molecular Dynamics Validation

- Perform 100 ns MD-simulation studies

- Confirm stable binding of compound 4 in aromatase binding pocket

- Validate binding modes and interactions identified through docking

Compound Design and Activity Prediction

- Design novel compound S8 based on model insights

- Predict pIC₅₀ value (0.719 nM) comparable to most active compound 4

Expected Outcomes: This protocol enables medicinal chemists to develop new indole-based aromatase inhibitors with optimized binding affinity and specificity, leveraging the essential pharmacophore features identified through the comprehensive modeling approach [22].

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for multi-faceted similarity in drug discovery, illustrating how different similarity approaches converge to identify lead candidates through experimental validation.

Diagram 2: STELLA framework architecture for fragment-based chemical space exploration and multi-parameter optimization, demonstrating superior performance compared to REINVENT 4.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Molecular Similarity Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type/Description | Key Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite | Comprehensive platform for QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and simulation [21] | Integrated molecular modeling and drug design |

| STELLA | Metaheuristics-based Generative Framework | Fragment-based chemical space exploration and multi-parameter optimization [23] | De novo molecular design with balanced property optimization |

| REINVENT 4 | Deep Learning-based Generative Framework | Molecular generation using reinforcement learning and transformer models [23] | AI-driven chemical space exploration and optimization |

| GOLD Docking Software | Molecular Docking Platform | Protein-ligand docking with genetic algorithm optimization [23] | Binding pose prediction and affinity estimation |

| CypD (PDB: 2BIT) | Protein Target | Cyclophilin D mitochondrial protein linked to Alzheimer's disease [21] | Target for Alzheimer's drug development |

| Informacophore Concept | Computational Approach | Data-driven identification of essential features for biological activity [20] | Machine learning-enhanced pharmacophore modeling |

| SOMFA (Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis) | 3D-QSAR Method | 3D-QSAR using shape and electrostatic potential fields [22] | Structure-activity relationship modeling |

| Ultra-large Chemical Libraries | Data Resource | Billions of make-on-demand compounds from suppliers (Enamine: 65B, OTAVA: 55B) [20] | Virtual screening and hit identification |

Molecular representations are foundational to modern computational drug discovery, serving as the bridge between chemical structures and machine-readable data for analysis and prediction. These representations translate the physical and chemical properties of molecules into mathematical formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior and properties [24] [25]. The choice of representation significantly influences the success of various drug discovery tasks, including virtual screening, activity prediction, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, and scaffold hopping [24] [7].

The evolution of these representations has progressed from simple string-based notations to complex, high-dimensional descriptors learned by deep learning models [24]. In the context of molecular similarity measures, the principle that structurally similar molecules often exhibit similar biological activity underpins many approaches, though nuances like the "similarity paradox" and "activity cliffs" present ongoing challenges [6]. Effective molecular representation is thus critical for accurately navigating chemical space in drug design and chemical space research.

Types of Molecular Representations

Molecular representations can be broadly categorized into molecular descriptors, molecular fingerprints, and string-based encodings. Each category offers distinct advantages and is suited to specific applications in cheminformatics and drug discovery.

Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that quantify specific physical, chemical, or topological characteristics of a molecule. They can be simple, such as molecular weight or count of hydrogen bond donors, or complex, such as topological indices derived from the molecular graph [24] [25]. Descriptors can be calculated using various software packages and are often used as input features for QSAR and machine learning models.

Table 1: Categories of Molecular Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Describes basic molecular composition, such as atom and bond counts, molecular weight. | Initial profiling, filtering [26] |

| Topological | Encodes connectivity and branching patterns within the molecular graph. | QSAR, similarity searching [6] |

| Geometric | Relates to the 3D shape and size of the molecule. | Shape-based virtual screening |

| Electronic | Describes electronic properties like polarizability and orbital energies. | Reactivity prediction, quantum mechanical studies [6] |

Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints are high-dimensional vector representations where each dimension corresponds to the presence, absence, or count of a specific structural pattern or chemical feature [27] [7]. They are one of the most widely used molecular representations for similarity searching, clustering, and virtual screening due to their computational efficiency.

Table 2: Major Types of Molecular Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Type | Basis of Generation | Key Characteristics | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substructure-based | Predefined library of structural patterns or functional groups. | Easily interpretable, fixed length. | MACCS, PubChem [27] |

| Circular | Atomic environments generated by iteratively exploring neighborhoods around each atom. | Captures local structure, excellent for activity prediction. | ECFP, FCFP [27] [7] |

| Path-based | All linear paths or atom pairs within the molecular graph. | Comprehensive encoding of molecular connectivity. | Daylight, Atom Pairs [27] |

| Pharmacophore-based | Presence of 2D or 3D pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors). | Focuses on bioactive features, facilitates scaffold hopping. | TransPharmer fingerprints, PH2, PH3 [28] [27] |

| String-based | Fragmentation of SMILES strings into fixed-size substrings. | Operates directly on string representation. | LINGO, MHFP [27] |

String Encodings

String-based representations provide a compact, line notation for molecular structures, making them easy to store, share, and use in sequence-based machine learning models.

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System): A string notation that uses a small alphabet of characters to represent a molecular graph as a sequence of atoms, bonds, branches, and ring closures [24] [25]. While highly compact and human-readable, its primary limitation is that small changes in the string can correspond to large changes in the molecular structure, and not all randomly generated strings correspond to valid molecules.

- SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings): A newer string-based representation designed to generate 100% syntactically valid molecules, making it particularly valuable for generative chemistry and de novo molecular design using deep learning models [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Representation Performance

The effectiveness of a molecular representation is highly dependent on the specific task and the chemical space being explored. Benchmarking studies provide crucial insights for selecting the most appropriate representation.

Table 3: Fingerprint Performance on Natural Product Bioactivity Prediction This table summarizes the performance (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve, AUC) of selected fingerprint types on 12 bioactivity prediction tasks involving natural products. The results demonstrate that performance is task-dependent [27].

| Fingerprint | Average AUC | Best Performance (Task) | Worst Performance (Task) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | 0.79 | 0.92 (Antifouling) | 0.63 (Antiviral) |

| MACCS | 0.76 | 0.89 (Antifouling) | 0.60 (Antiviral) |

| PH2 | 0.77 | 0.91 (Antifouling) | 0.62 (Antiviral) |

| MHFP | 0.80 | 0.93 (Antifouling) | 0.65 (Antiviral) |

| MAP4 | 0.81 | 0.94 (Antifouling) | 0.66 (Antiviral) |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that leverage molecular representations in drug discovery.

Protocol: Implementing a Pharmacophore-Conditioned Generative Model

This protocol outlines the methodology based on the TransPharmer model for generating novel molecules constrained by desired pharmacophoric features [28].

1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Materials for Pharmacophore-Conditioned Generation

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Database | Source of structures for training the generative model. | ChEMBL, ZINC, or corporate database. |

| Fingerprinting Software | Generates ligand-based pharmacophore fingerprints. | RDKit, proprietary implementations per TransPharmer [28]. |

| Generative Model Architecture | GPT-based framework for molecule generation. | Transformer model conditioned on fingerprint prompts [28]. |

| Validation Assays | Tests bioactivity of generated compounds. | In vitro kinase assay (e.g., for PLK1 inhibition) [28]. |

2. Procedure

- Pharmacophore Fingerprint Extraction: For each molecule in the training set, compute a multi-scale, interpretable pharmacophore fingerprint. This fingerprint abstracts structural information while preserving fine-grained topological and pharmaceutical feature data (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic regions) [28].

- Model Training: Train a Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) model to establish a connection between the pharmacophore fingerprints (used as prompts) and molecular structures represented as SMILES strings. The training objective is for the model to learn the distribution of molecules in the training data and their corresponding pharmacophoric properties [28].

- Conditional Generation: To generate new molecules, provide the trained TransPharmer model with a target pharmacophore fingerprint that embodies the desired pharmaceutical profile. The model will then generate novel SMILES strings that conform to these pharmacophoric constraints.

- Scaffold Hopping Exploration: Utilize the model's unique exploration mode to probe the chemical space around a reference active compound. By using the reference compound's pharmacophore fingerprint as a condition, the model can generate structurally distinct molecules (new scaffolds) that maintain the core pharmaceutical features, enabling scaffold hopping [28].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize the top-generated compounds and validate their bioactivity and potency experimentally. For example, in the PLK1 case study, four generated compounds were synthesized, and three showed submicromolar activity, with the most potent (IIP0943) achieving 5.1 nM potency [28].

Protocol: Building a QSAR Model using Machine Learning

This protocol describes the steps for creating a global QSAR model to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) properties, applicable even to complex modalities like Targeted Protein Degraders (TPDs) [26].

1. Research Reagent Solutions Table 5: Essential Materials for QSAR Modeling

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| ADME Dataset | Curated experimental data for model training and testing. | In-house data, public sources; should include diverse chemistries [26]. |

| Molecular Representation Tool | Generates feature vectors for molecules. | RDKit, alvaDesc, or other software for fingerprints/descriptors. |

| Machine Learning Library | Provides algorithms for model training. | Scikit-learn, Deep Graph Library (for MPNNs) [26]. |

| Model Evaluation Framework | Assesses model performance and generalizability. | Temporal validation setup; metrics: MAE, F1-score, misclassification rate [26]. |

2. Procedure

- Data Curation and Standardization: Collect a large dataset of compounds with experimentally measured properties (e.g., permeability, metabolic clearance). Apply chemical standardization: remove salts, neutralize charges, and check for errors using a tool like the ChEMBL structure curation package [26] [27].

- Molecular Representation: Encode each standardized molecule using a selected representation. For global models, circular fingerprints (ECFP) or molecular descriptors are common choices. For TPDs, which often lie beyond the Rule of 5, ensure the representation can capture their complex features [26].

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model on the encoded molecular data. Modern approaches often use multi-task learning, where a single model (e.g., a Message Passing Neural Network coupled with a Deep Neural Network) is trained to predict several related ADME endpoints simultaneously, which can improve generalization [26].

- Temporal Validation: Evaluate model performance using a temporal split, where the model is trained on data from before a certain date and tested on the most recent data. This simulates real-world deployment and provides a realistic estimate of predictive accuracy on new chemical series [26].

- Error Analysis: Calculate performance metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for regression or misclassification rates for categorical predictions. Specifically analyze errors for sub-modalities of interest (e.g., heterobifunctional TPDs vs. molecular glues) to identify potential model biases or applicability domain limitations [26].

Application in Scaffold Hopping

Scaffold hopping—discovering new core structures with similar biological activity—is a critical application of advanced molecular representations in lead optimization [24]. It helps improve pharmacokinetic properties, reduce off-target effects, and design novel patentable compounds.

Pharmacophore-based fingerprints, like those used in TransPharmer, are particularly powerful for this task. By focusing on the arrangement of functional groups essential for biological activity rather than the exact atomic scaffold, these representations enable generative models to propose structurally diverse compounds that maintain key interactions with the target protein [28] [24]. For instance, TransPharmer successfully generated a potent PLK1 inhibitor featuring a novel 4-(benzo[b]thiophen-7-yloxy)pyrimidine scaffold, which was structurally distinct from known inhibitors yet retained high potency and selectivity [28]. This demonstrates how abstract, feature-based representations can effectively guide exploration to novel regions of chemical space while preserving desired bioactivity.

In computational drug discovery, molecular similarity is a foundational concept used for virtual screening, scaffold hopping, and lead optimization. The core hypothesis—that structurally similar molecules exhibit similar biological activities—has driven research and development for decades. However, this principle is deceptively simple. Similarity is not an intrinsic molecular property but a subjective measure that is highly dependent on the choice of molecular representation and the biological or chemical context of interest [24] [4]. Different representations highlight distinct aspects of molecular structure, leading to varying outcomes in similarity assessment and subsequent virtual screening hits.

This article explores the profound impact of representation and context on molecular similarity measures, framed within the broader thesis of drug design and chemical space research. We provide application notes and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting and applying these methods effectively, enabling more nuanced and successful navigation of the biologically relevant chemical space (BioReCS) [4].

The translation of a molecular structure into a computer-readable format is the critical first step that dictates what patterns and relationships a model can learn. The choice of representation implicitly defines the "lens" through which similarity is viewed.

Traditional Representations

Traditional methods rely on hand-crafted features or string-based notations.

- Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP): Encode the presence of molecular substructures as fixed-length bit vectors. Similarity is typically computed using the Tanimoto coefficient, which measures the overlap of "on" bits between two molecules [24].

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System): A string-based notation that represents molecular structure as a sequence of characters using a compact grammar of atomic symbols and connectivity indicators [24]. While simple, its primary limitation is that small changes in the string can represent the same molecule or lead to invalid structures.

Modern AI-Driven Representations

Modern approaches use deep learning to automatically learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings from data.

- Language Model-based: Models like Transformer networks treat SMILES strings as a specialized chemical language. Through pre-training tasks like masked atom prediction, they learn embeddings that capture syntactic and semantic relationships between molecular substructures, going beyond simple string matching [24].

- Graph-based: Represent molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) learn embeddings by passing and transforming information between connected nodes. This naturally captures the topological structure of the molecule, which string-based methods can miss [24] [29].

- Multimodal-based: These methods, such Asymmetric Contrastive Multimodal Learning (ACML), aim to create more holistic representations by jointly learning from multiple modalities of data (e.g., molecular graph, SMILES, NMR spectra, images). By aligning information from different sources, the model learns a richer, more robust representation that captures a wider array of chemical semantics [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Molecular Representation Methods

| Representation Type | Key Example(s) | Underlying Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Fingerprint | ECFP, ECFP [24] | Predefined dictionary of structural keys or hashed substructures. | Computationally efficient, highly interpretable, excellent for similarity search. | Relies on expert-defined features, may miss complex or novel structural patterns. |

| String-Based | SMILES [24] | Line notation describing atom connectivity. | Simple, compact, human-readable. | Sensitive to syntax; small string changes can alter molecular identity or validity. |

| AI-Language Model | SMILES-based Transformers [24] | Treats SMILES as a language; learns embeddings via self-supervision. | Captures complex, non-linear relationships in chemical "syntax". | Can be data-hungry; potential for generating invalid structures. |

| AI-Graph-Based | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [24] [29] | Directly models molecular graph structure. | Captures intrinsic topology and connectivity; powerful for property prediction. | Computationally intensive; complex training. |

| AI-Multimodal | ACML [29] | Aligns information from multiple modalities (e.g., graph, SMILES, spectra) into a joint embedding. | Comprehensive; captures complementary information; can reveal hierarchical features. | High data and computational requirements; complex implementation. |

Application Notes: The Impact of Representation on Similarity and Scaffold Hopping

The theoretical differences between representations have tangible, significant consequences in practical drug discovery tasks.

Case Study: Scaffold Hopping with STELLA

A recent case study demonstrates the power of advanced, representation-aware generative models. The STELLA framework, which uses a metaheuristic algorithm for fragment-level chemical space exploration, was benchmarked against the deep learning-based REINVENT 4 in a task to generate novel PDK1 inhibitors [23].

The results were striking. STELLA, by leveraging a more flexible fragment-based representation and a clustering-based selection mechanism to maintain diversity, generated 217% more hit candidates with 161% more unique scaffolds than REINVENT 4 [23]. This underscores that the method of representing and exploring chemical space (e.g., fragment-based vs. SMILES-based generation) directly dictates the diversity and novelty of the resulting scaffolds, a core objective in scaffold hopping.

The Multimodal Advantage

The ACML framework provides a clear example of how combining multiple "lenses" or representations improves the model's fundamental understanding. By performing asymmetric contrastive learning between molecular graphs and other modalities like SMILES, NMR, or mass spectra, ACML forces the graph encoder to learn a representation that assimilates coordinated chemical semantics from all modalities [29].

This results in a model with enhanced capabilities in challenging tasks like isomer discrimination, where distinguishing molecules with the same atoms but different connectivities or spatial arrangements is critical. A model using only a single representation might struggle, but a multimodal model can leverage complementary information to make finer distinctions [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Generative Models in a Multi-parameter Optimization Task

| Model | Architecture | Key Representation | Number of Hit Candidates | Unique Scaffolds Generated | Performance in 16-property Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REINVENT 4 [23] | Deep Learning (Transformer) | SMILES-based | 116 | Baseline | Lower average objective scores |

| MolFinder [23] | Metaheuristics | SMILES-based | Not Specified | Not Specified | Lower average objective scores |

| STELLA [23] | Metaheuristics (Evolutionary Algorithm) | Fragment-based | 368 | +161% vs. REINVENT 4 | Superior average objective scores & broader chemical space exploration |

Experimental Protocols

Below are detailed methodologies for implementing and evaluating molecular similarity approaches.

Protocol: Implementing a Multimodal Contrastive Learning Framework (e.g., ACML)

Purpose: To train a molecular representation model by integrating information from multiple chemical modalities, enhancing performance on downstream tasks like property prediction and cross-modal retrieval [29].

Materials:

- Software: Python, deep learning framework (PyTorch/TensorFlow), chemoinformatics toolkit (RDKit).

- Data: Paired molecular datasets including graphs, SMILES strings, and optionally, spectral data (1H NMR, 13C NMR, GCMS/LCMS).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Graph Modality: For each molecule, generate a molecular graph with nodes (atoms) and edges (bonds). Node and edge features should be initialized (e.g., atom type, degree, hybridization).

- Other Modalities: For SMILES, use standard string representation. For spectral data, convert spectra into a standardized vector or image format.

Encoder Setup:

- Utilize a frozen, pretrained unimodal encoder for the chemical modality (e.g., a trained CNN for SMILES or spectra).

- Initialize a trainable graph encoder (e.g., a 5-layer GNN) with random weights [29].

Projection and Training:

- Project the embeddings from both encoders into a joint latent space of the same dimension using separate Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs).

- For a minibatch of N molecules, construct a similarity matrix. The diagonal elements (graphi, modalityi) are positive pairs; off-diagonals are negative pairs.

- Optimize the graph encoder and projection modules using a contrastive loss (e.g., InfoNCE) to maximize agreement for positive pairs and minimize it for negative pairs.

Downstream Task Evaluation:

- Use the trained graph encoder's embeddings for tasks like molecular property prediction on benchmarks like MoleculeNet or cross-modality retrieval.

Protocol: Conducting a Scaffold Hopping Study with a Generative Model

Purpose: To generate novel molecular scaffolds with retained biological activity using a generative molecular design framework, demonstrating the practical outcome of different similarity measures embedded in the model's exploration logic.

Materials:

- Software: STELLA, REINVENT 4, or other generative model software.

- Data: A seed molecule with known biological activity.

- Property Prediction Tools: Docking software (e.g., GOLD), QED calculator.

Procedure:

- Initialization: Provide a known active molecule as the seed for the generative model.

- Molecule Generation:

- In STELLA, an evolutionary algorithm generates new molecules via fragment-based mutation, maximum common substructure (MCS)-based crossover, and trimming [23].

- In REINVENT 4, a deep learning model (e.g., Transformer) generates new SMILES strings.

Scoring: Evaluate generated molecules using an objective function. For example:

Objective Score = w1 * Docking_Score + w2 * QED, where w1 and w2 are weights. This defines the "context" for optimization.Selection and Iteration:

- STELLA: Employs a clustering-based conformational space annealing method. It clusters all molecules and selects the top-scoring molecule from each cluster, progressively reducing the distance cutoff to transition from diversity (exploration) to pure optimization (exploitation) [23].

- REINVENT 4: Uses reinforcement learning to update the model, reinforcing the generation of molecules with high objective scores.

Analysis: After a set number of iterations, analyze the output. Compare the number of hit candidates, the diversity of scaffolds (e.g., via Bemis-Murcko scaffolds), and the Pareto front of optimized properties against a baseline model [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Datasets for Molecular Similarity and Generation Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Similarity & Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics and machine learning. | Standard for handling molecular representations (SMILES, graphs, fingerprints); essential for data preprocessing and feature calculation. |

| ChEMBL [4] | Public Database | Curated database of bioactive molecules. | Source of annotated bioactivity data for training and benchmarking similarity-based and AI models; defines regions of BioReCS. |

| PubChem [4] | Public Database | Repository of chemical substances and their biological activities. | Provides a vast chemical space for similarity searching and contains negative bioactivity data crucial for defining non-active chemical space. |

| STELLA [23] | Generative Framework | Metaheuristics-based molecular design. | Demonstrates the application of fragment-based representations and clustering for diverse scaffold hopping in a multi-parameter context. |

| ACML Framework [29] | AI Model | Asymmetric contrastive multimodal learning. | Tool for learning unified molecular embeddings from multiple data modalities, enhancing model robustness and task performance. |

| ECFP/ FCFP [24] | Molecular Fingerprint | Fixed-length vector representation of substructures. | Classic, interpretable representation for rapid similarity searching and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models. |

From Theory to Practice: Methods and Applications in Drug Discovery

Molecular similarity serves as a cornerstone of modern cheminformatics and drug design, enabling researchers to predict biological activity, navigate chemical space, and identify novel therapeutic candidates [19]. The principle that structurally similar molecules often exhibit similar properties or biological activities underpins many computational approaches in drug discovery [6]. Traditional similarity metrics—including Tanimoto, Jaccard, Dice, and Cosine coefficients—provide the mathematical foundation for quantifying these structural relationships, forming an essential component of the virtual screening toolkit [30]. These metrics, when applied to molecular fingerprints, allow for efficient comparison of chemical structures across large compound databases, facilitating tasks ranging from hit identification to scaffold hopping [24]. This application note details the theoretical basis, practical implementation, and experimental protocols for utilizing these fundamental similarity measures in drug discovery research.

Comparative Analysis of Similarity Metrics

Mathematical Foundations

Traditional similarity metrics operate primarily on binary molecular fingerprints, which encode the presence or absence of structural features as bit vectors [31] [30]. The following table summarizes the key mathematical properties of these fundamental coefficients:

Table 1: Fundamental Similarity and Distance Metrics for Binary Molecular Fingerprints

| Metric Name | Formula for Binary Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanimoto (Jaccard) | ( T = \frac{x}{y + z - x} ) | 0 | 1 | Similarity |

| Dice (Hodgkin index) | ( D = \frac{2x}{y + z} ) | 0 | 1 | Similarity |

| Cosine (Carbo index) | ( C = \frac{x}{\sqrt{y \cdot z}} ) | 0 | 1 | Similarity |

| Soergel distance | ( S = 1 - T ) | 0 | 1 | Distance |

| Euclidean distance | ( E = \sqrt{(y - x) + (z - x)} ) | 0 | N(_{\alpha}) | Distance |

| Hamming distance | ( H = (y - x) + (z - x) ) | 0 | N(_{\alpha}) | Distance |

Where: x = number of common "on" bits in both fingerprints; y = total "on" bits in fingerprint A; z = total "on" bits in fingerprint B; N(_{\alpha}) = length of the fingerprint [31].

The Tanimoto coefficient (also known as Jaccard coefficient) remains the most widely used similarity measure in cheminformatics, calculating the ratio of shared features to the total number of unique features present in either molecule [31] [30]. Its dominance stems from consistent performance in ranking compounds during structure-activity studies, despite a known bias toward smaller molecules [30].

The Dice coefficient (also called Hodgkin index) similarly measures feature overlap but gives double weight to the common features, making it less sensitive to the absolute size difference between molecules [31] [32].

The Cosine coefficient (Carbo index) measures the angle between two fingerprint vectors in high-dimensional space, effectively capturing directional agreement regardless of vector magnitude [31] [32].

Distance metrics like Soergel, Euclidean, and Hamming quantify dissimilarity rather than similarity. The Soergel distance represents the exact complement of the Tanimoto coefficient (their sum equals 1), while Euclidean and Hamming distances require normalization when converted to similarity scores [31].

Performance Considerations in Virtual Screening

Systematic benchmarking studies have revealed significant performance variations among similarity metrics depending on fingerprint type and biological context. One comprehensive evaluation using chemical-genetic interaction profiles in yeast as a biological activity benchmark found that the optimal pairing of fingerprint encodings and similarity coefficients substantially impacts retrieval rates of functionally similar compounds [30].

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Molecular Fingerprints and Similarity Coefficients

| Fingerprint Type | Description | Optimal Similarity Coefficient | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASP (All-Shortest Paths) | Encodes all shortest topological paths between atoms | Braun-Blanquet | Robust performance across diverse compound collections |

| ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints) | Circular fingerprints capturing atom environments | Tanimoto, Dice | Structure-activity relationship studies |

| MACCS Keys | 166 structural keys based on functional groups | Tanimoto | Rapid similarity screening |

| RDKit Topological | Daylight-like fingerprint based on molecular paths | Various | General-purpose similarity searching |

The Braun-Blanquet similarity coefficient ((x/max(y,z))), though less commonly discussed, demonstrated superior performance when paired with all-shortest path (ASP) fingerprints in large-scale benchmarking, offering robust retrieval of biologically similar compounds across multiple compound collections [30].

For researchers applying these metrics, a Tanimoto coefficient threshold of 0.85 has historically indicated a high probability of two compounds sharing similar biological activity [31]. However, this threshold is fingerprint-dependent; 0.85 computed from MACCS keys represents different structural similarity than the same value computed from ECFP fingerprints [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Fingerprint Generation and Similarity Calculation

This protocol describes the standard workflow for generating molecular fingerprints and calculating similarity coefficients using open-source cheminformatics tools.