MP2 vs DFT for Noncovalent Interactions: A Researcher's Guide to Accuracy and Efficiency in Drug Discovery

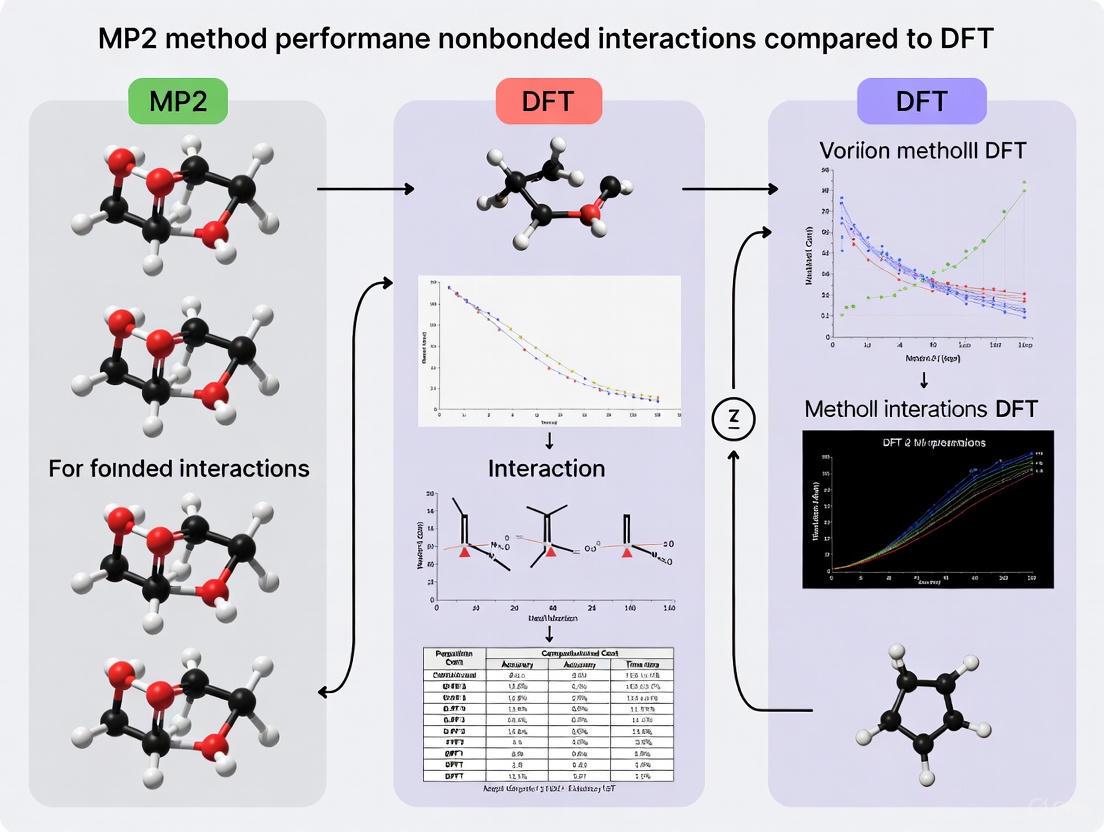

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) and Density Functional Theory (DFT) for modeling noncovalent interactions, which are critical in biochemical processes...

MP2 vs DFT for Noncovalent Interactions: A Researcher's Guide to Accuracy and Efficiency in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) and Density Functional Theory (DFT) for modeling noncovalent interactions, which are critical in biochemical processes and drug design. We explore the foundational principles of both methods, highlighting MP2's inherent ability to capture dispersion forces and the empirical corrections required for DFT. The discussion covers advanced methodological variants like spin-component-scaled MP2 and dispersion-corrected double-hybrid DFT, offering practical guidance for their application to biological systems. We address common challenges such as MP2's overestimation of π-π stacking and the system-dependent performance of DFT, presenting optimization strategies and cost-reduction techniques. Finally, we benchmark these methods against high-accuracy 'gold standard' coupled-cluster calculations and emerging machine learning potentials, synthesizing key takeaways to inform reliable protocol selection for pharmaceutical research.

The Quantum Chemical Foundation of Noncovalent Interactions

Why Noncovalent Interactions are the 'Invisible Architects of Life' in Biochemistry

In the intricate world of biochemistry, the stability, structure, and function of biomolecules are governed not only by strong covalent bonds but predominantly by a symphony of subtle, reversible attractive forces known as noncovalent interactions. With energies typically ranging from -0.5 to -50 kcal mol⁻¹, these interactions include hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, π-stacking, halogen bonds, and various other electrostatic forces [1]. Unlike covalent bonds, noncovalent interactions do not involve shared electron pairs; instead, they arise from electrostatic interactions, polarization, dispersion, and charge transfer effects [1]. This review examines why these interactions are rightfully termed the "invisible architects of life," focusing particularly on the computational challenge of accurately modeling them and providing a detailed performance comparison between modern MP2 and Density Functional Theory (DFT) methodologies.

The Biological Significance of Noncovalent Interactions

Fundamental Roles in Biomolecular Systems

Noncovalent interactions perform critical architectural and functional roles throughout biological systems:

- Protein Folding and Stability: The precise three-dimensional structures of proteins, essential for their function, are sculpted and stabilized by the collective effect of numerous noncovalent interactions that fold the polypeptide chain into its native conformation [1].

- Molecular Recognition: Processes such as enzyme-substrate binding, antibody-antigen complexation, and signaling pathways rely on specific noncovalent interactions that enable selective molecular recognition [1].

- Nucleic Acid Structure: The double-helical structure of DNA is maintained by π-π stacking between base pairs and hydrogen bonding, while RNA folding involves various noncovalent forces [2].

- Dynamic Functionality: The reversible nature of noncovalent interactions allows biomolecules to transition between conformational states, a property essential for allosteric regulation, catalytic activity, and cellular adaptability [2].

Unconventional Noncovalent Interactions

Beyond conventional hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic effects, research over the past decade has revealed the importance of numerous specialized interactions:

Table: Unconventional Noncovalent Interactions in Proteins

| Interaction Type | Chemical Description | Approximate Strength (kcal mol⁻¹) | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-barrier H-bonds (LBHB) | Short, strong H-bonds with symmetric H placement | -12 to -24 | Catalysis in serine proteases, ligand binding |

| C–H···π interactions | H to π-system attraction | -0.5 to -3 | Protein structure stabilization |

| n → π* interactions | Carbonyl O lone pair donation to adjacent carbonyl π* | -0.5 to -1.0 | Protein backbone organization |

| Halogen bonds | R-X···O/N (X = Cl, Br, I) | -1 to -5 | Molecular recognition, ligand design |

| Chalcogen bonds | R-Y···O/N (Y = S, Se, Te) | -1 to -4 | Protein structure and function |

The Computational Challenge: Accuracy vs. Efficiency

Accurately modeling noncovalent interactions represents one of the most pressing challenges in computational chemistry and biology. The subtle energetic contributions of these interactions fall within the accuracy limits of even sophisticated quantum chemical methods [2]. This creates a paradox where the collective influence of these interactions is decisive for biological function, yet their individual weakness makes precise calculation demanding.

Key Methodological Considerations

The accurate prediction of interaction energies requires careful attention to several factors:

- Electron Correlation: Noncovalent interactions, particularly dispersion forces, are correlation effects not captured by Hartree-Fock theory, requiring methods that account for electron-electron correlations [2].

- Basis Set Requirements: Adequate basis sets with diffuse functions are necessary to describe the electron density in the intermolecular region, though this increases computational cost [3].

- Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE): This artificial lowering of energy due to incomplete basis sets must be corrected, typically via the counterpoise method [3].

- Balanced Treatment: Methods must simultaneously handle various interaction types (electrostatic, dispersion, charge-transfer) without bias toward specific categories [2].

Performance Comparison: MP2 vs. DFT Methodologies

Traditional Methods and Their Limitations

Traditional second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) provides a reasonable description of electron correlation at moderate computational cost but tends to overestimate dispersion interactions and performs poorly for certain π-systems [2]. Standard DFT functionals, particularly popular ones like B3LYP, fail to accurately represent London dispersion interactions, a serious limitation for modeling biomolecular systems [3].

Advanced MP2 Approaches

Significant improvements to MP2 have been developed through empirical scaling and algorithmic acceleration:

Table: Performance of Advanced MP2 Methods for Noncovalent Interactions

| Method | Description | Key Innovations | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCS-MP2 | Spin-component-scaled MP2 | Separate scaling of same-spin and opposite-spin correlation components | Improved accuracy for various weak interactions |

| RI-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ | Resolution-of-identity accelerated SCS-MP2 | RI approximation for Coulomb integrals; parameters optimized for biological weak interactions | Errors <1 kcal/mol vs. CCSD(T)/CBS; exceptional for π-π stacking |

| RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ | Combined RI and COSX (chain-of-spheres) acceleration | Fast exchange via numerical integration | High accuracy with efficiency superior to hybrid DFT |

| MP2C | MP2 with coupled dispersion correction | Adds coupled dispersion energy correction in monomer-centered basis | Addresses MP2 dispersion overestimation |

These MP2 variants demonstrate exceptional performance in benchmarking against CCSD(T)/CBS reference data, with particularly impressive accuracy for biological systems including DNA base pairs, halogen-bonded complexes, and large biomolecular dimers [2].

DFT-Based Correction Schemes

To address the limitations of standard DFT, several correction schemes have been developed:

- B3LYP-D3: Adds semiempirical dispersion corrections with damping functions to B3LYP, significantly improving performance for dispersion-bound complexes [3].

- B3LYP-MM: A novel, empirically parameterized correction specifically designed for B3LYP, incorporating a Lennard-Jones potential, specialized hydrogen bonding, and cation-π correction terms [3].

- Double-Hybrid Functionals: Approaches like B2PLYP and DSD-BLYP with empirical dispersion corrections (D3BJ) have demonstrated superior performance for describing weak interactions [2].

- Range-Separated Hybrids: Functionals such as ωB97M-V, ωB97X-V, and ωB97X-D3 show excellent predictive capabilities for noncovalent interactions [2].

Comparative Performance Data

Table: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Noncovalent Interactions (kcal/mol)

| Method | Dispersion/Dipole-Dipole Complexes (aug-cc-pVDZ) | Overall Performance (LACVP* basis, no CP) | Hydrogen-Bonded Systems | Cation-π Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP-MM | 0.27 (MUE) | 0.41 (MUE) | Major improvements | Major improvements |

| B3LYP-D3 | 0.32 (MUE) | 2.11 (MUE) | Moderate accuracy | Moderate accuracy |

| M06-2X | 0.47 (MUE) | 1.20 (MUE) | Good accuracy | Good accuracy |

| RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ | <1.0 (vs. CCSD(T)/CBS) | Highly accurate | High accuracy | High accuracy |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

High-Level Reference Data

The development of reliable computational methods depends on accurate benchmark data. The field has been advanced significantly by carefully curated datasets:

- The S22 Dataset: A standard test set of 22 noncovalent interaction energies pioneered by Hobza and coworkers [3].

- Extended Benchmark Sets: Larger datasets including 2027 CCSD(T) interaction energies have been assembled to provide diverse training and testing data [3].

- Biological Conformer Databases: CCSD(T) level conformational energies of di- and tripeptides, sugars, and cysteine provide relevant benchmarks for biological systems [3].

Workflow for Method Validation

The following diagram illustrates a rigorous protocol for validating computational methods for noncovalent interactions:

Validation Workflow for Noncovalent Interaction Methods

Specialized Treatment for Specific Interactions

Advanced correction schemes incorporate specialized treatments for particular interaction types:

- Hydrogen Bonding: The B3LYP-MM scheme excludes Lennard-Jones dispersion corrections for hydrogen-heavy atom pairs involved in hydrogen bonds and applies a linear repulsive correction term to address BSSE, which is particularly strong for hydrogen bonds due to short interatomic distances [3].

- Cation-π Interactions: Specialized approaches exclude Lennard-Jones terms for positively charged metal ions and ammonium hydrogens, instead applying linear repulsive correction terms for cation-π interactions [3].

- Halogen Bonding: Specifically parameterized methods such as SCS-MP2-hal have been developed for accurate treatment of halogen-containing compounds [2].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Noncovalent Interaction Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, PSI4 | Perform quantum chemical calculations (DFT, MP2, CCSD(T)) |

| Wavefunction Analysis | Multiwfn, AIMAll, NBO | Analyze electron density, bond critical points, orbital interactions |

| Visualization & Packing Analysis | CrystalExplorer, VMD, GaussView | Generate Hirshfeld surfaces, RDG analyses, molecular graphics |

| Force Field Packages | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecular systems |

| Benchmark Databases | S22, A24, HB300SPX, BEGDB | Reference data for method validation and training |

The computational study of noncovalent interactions requires careful method selection based on the specific research problem:

- For maximum accuracy with small to medium systems, RI-accelerated SCS-MP2 variants (RI-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ, RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ) currently provide the best combination of reliability and computational feasibility [2].

- For large systems requiring DFT, dispersion-corrected functionals (B3LYP-D3, B3LYP-MM, ωB97M-V) offer the best balance of accuracy and computational efficiency [3] [2].

- For specific applications involving hydrogen bonding or ionic interactions, specialized correction schemes like B3LYP-MM show clear advantages [3].

The ongoing development of more accurate and efficient computational methods continues to enhance our understanding of the invisible forces that shape life at the molecular level, enabling advances in drug design, materials science, and fundamental biology. As method development progresses, the integration of machine learning approaches with traditional quantum chemistry shows promise for further accelerating the reliable prediction of these essential interactions in increasingly complex biological environments [5].

MP2's Inherent Treatment of Electron Correlation and Dispersion

Accurately modeling nonbonded interactions, such as dispersion forces, is a central challenge in computational chemistry with significant implications for drug development and materials science. Two predominant theoretical frameworks are employed: post-Hartree-Fock wave function theories, led by Møller-Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2), and the diverse family of Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods. These approaches offer fundamentally different solutions for incorporating electron correlation, the key to describing weak intermolecular forces. MP2 inherently accounts for dispersion through its wave function-based formalism, treating electron correlation as a perturbation to the Hartree-Fock solution [6]. In contrast, standard DFT approximations suffer from a well-documented inability to describe long-range electron correlations, which are responsible for dispersive forces, necessitating the addition of empirical corrections [6]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of the performance of MP2 and DFT for nonbonded interactions, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal method for their systems.

Theoretical Foundations and inherent Treatment of Dispersion

The MP2 Approach: A Natural Description of Dispersion

The MP2 method is the simplest and most economical approach among post-Hartree-Fock wave function-based theories. Its principal advantage for nonbonded interactions lies in its natural inclusion of dispersion energy. MP2 is free from the spurious self-interaction of electrons that plagues many DFT functionals and inherently accounts for long-range electron correlation effects that give rise to dispersion forces [6]. However, this description is not perfect; the method can overestimate interaction energies because it utilizes the uncoupled Hartree-Fock dispersion energy, which lacks a repulsive intramolecular correlation correction [6].

The DFT Approach: A Patchwork of Solutions

Density Functional Theory methods excel in their favorable computational cost-to-accuracy ratio, scaling formally between O(N3) and O(N4). However, they struggle with two key issues: self-interaction error, leading to excessive electron delocalization, and a fundamental inability to describe long-range dispersion forces [6]. The DFT community has addressed these weaknesses through various strategies. Self-interaction can be partially mitigated by including long-range correction or a significant portion of exact exchange. The lack of dispersion is typically compensated by empirical corrections, such as the DFT-D2 and later methods, which add an attractive energy term that decays with R⁻⁶ [6]. This makes the accuracy of a DFT calculation highly dependent on the chosen functional and the quality of its empirical dispersion correction.

Performance Comparison: MP2 vs. DFT for Nonbonded Complexes

Benchmark Study: Stannylene-Aromatic Complexes

A comprehensive benchmark study assessed the performance of six MP2-type methods and 14 DFT functionals for investigating interactions between stannylenes (SnX₂) and aromatic molecules (benzene and pyridine) [6]. The study used CCSD(T)-level interaction energies and CCSD-optimized structures as reference data, providing a high-quality benchmark for evaluation.

Table 1: Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods for SnH₂-Benzene and SnH₂-Pyridine Complexes

| Method | Category | Performance for SnH₂-Benzene | Performance for SnH₂-Pyridine | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS-MP2 | MP2-type | Accurate interaction energy | Most accurate structure prediction | Best overall for interaction energies |

| SOS-MP2 | MP2-type | Most accurate structure prediction | Good performance | Excellent for geometries |

| ωB97X | DFT (RSH) | Good accuracy for structure & energy | Good accuracy for structure & energy | Best tested DFT functional |

| B3LYP | DFT (GH) | Poor without dispersion correction | Poor without dispersion correction | Requires empirical dispersion |

Quantitative Data on Interaction Energies and Structures

The benchmark study yielded specific quantitative results on the capabilities of different methods. Among the MP2-type methods, SCS-MP2 performed best in predicting the interaction energy for both the SnH₂-benzene and SnH₂-pyridine complexes [6]. For the geometry of the SnH₂-benzene complex, SOS-MP2 most accurately reproduced the reference structure, while SCS-MP2 was the most accurate for the SnH₂-pyridine structure [6]. When evaluating DFT methods, the range-separated hybrid functional ωB97X provided structures and interaction energies for both complexes with good accuracy, though it was not as effective as the best-performing MP2-type methods [6]. The study concluded that range-separated hybrid (e.g., ωB97X) or dispersion-corrected density functionals are necessary to describe the interactions in stannylene-aromatic complexes with reasonable accuracy [6].

Table 2: Overall Comparison of MP2 and DFT Characteristics

| Aspect | MP2 & Variants | Standard DFT (e.g., B3LYP) | Advanced DFT (ωB97X, DFT-D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersion Treatment | Inherent, physically grounded | Lacking, requires empirical add-ons | Empirical or range-separated correction |

| Self-Interaction Error | Free from spurious self-interaction | Suffers from self-interaction error | Partially corrected |

| Computational Cost | O(N⁵), more expensive [6] | O(N³) to O(N⁴), more efficient [6] | O(N³) to O(N⁴), efficient [6] |

| Accuracy for Nonbonded Interactions | Generally high, but can overbind [6] | Poor without dispersion correction [6] | Good to very good with proper correction [6] |

| System Dependence | Performance consistent | Performance varies greatly with functional | Performance varies with functional/correction |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow for Method Assessment

The following diagram outlines the standard protocol for benchmarking computational methods, as employed in the stannylene-aromatic complexes study [6]:

Detailed Computational Methodology

The benchmark study provides specific details on its computational approach [6]:

- Reference Methods: CCSD was used to provide reference geometries for the non-covalently interacting complexes, while CCSD(T), considered the "gold standard" for intermolecular interaction energies, provided reference interaction energies [6].

- MP2-type Methods: The assessment included the conventional MP2 method and five of its modifications: SCS-MP2, SOS-MP2, FE2-MP2, SCS(MI)-MP2, and S2-MP2. These methods employed the Resolution of the Identity (RI) technique and the frozen core approximation to improve computational efficiency [6].

- DFT Methods: The tested functionals represented multiple generations of DFT, including GGA (e.g., BLYP, BP86), global hybrids (e.g., B3LYP, B98), meta-GGA (TPSS), and range-separated hybrids (e.g., ωB97X, M11). The dispersion correction D2 was applied to some older functionals to evaluate its impact on performance [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function in Research | Example Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Reference Method | Provides "gold standard" energies for benchmarking | TURBOMOLE, Gaussian |

| MP2 & Variants | Wave Function Method | Economical post-HF method with inherent dispersion | TURBOMOLE, Gaussian, ORCA |

| Density Functionals | DFT Method | Efficient electronic structure calculation | All major QC packages |

| RI / DF Technique | Computational Accelerator | Speeds up MP2/DFT calculations via integral approximation [7] | TURBOMOLE, ORCA |

| Basis Sets | Mathematical Basis | Set of functions to represent molecular orbitals | aug-cc-pVnZ, cc-pVnZ |

| Basis Set Extrapolation | Accuracy Enhancement | Estimates complete basis set (CBS) limit result [8] | Custom scripts |

This comparison demonstrates that MP2 possesses a fundamental, inherent strength in its treatment of electron correlation and dispersion forces, making it a robust choice for investigating nonbonded interactions. While it carries a higher computational cost than DFT, its performance is generally more predictable and does not rely on system-specific empirical corrections. For drug development professionals, this reliability is crucial when studying ligand-receptor interactions dominated by dispersion. The ongoing development of MP2 variants like SCS-MP2 continues to refine its accuracy. Conversely, modern, dispersion-corrected, or range-separated hybrid DFT functionals can provide a highly efficient and often accurate alternative, though their performance must be validated for the specific system of interest. The choice between MP2 and DFT ultimately hinges on the trade-off between computational cost, required accuracy, and the specific nature of the chemical system being investigated.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become the predominant method for first-principles modeling of complex molecular systems across chemistry, materials science, and drug development due to its favorable balance of computational cost and accuracy. [9] However, conventional DFT approaches suffer from a well-documented failure: their inability to adequately describe dispersion forces, also known as van der Waals (vdW) interactions or weak non-covalent interactions. [9] These forces arise from non-local, non-classical electron correlations across regions of sparse electron density, which local (LDA) and semi-local (GGA) exchange-correlation functionals cannot capture. [9] This represents a critical limitation because despite being classified as "weak" forces, non-covalent interactions play a fundamental role in numerous physicochemical processes, including biomolecular folding, supramolecular assembly, and molecular recognition—processes central to rational drug design. [9]

This guide objectively compares the empirical strategies developed to overcome this challenge, benchmarking their performance against wavefunction-based methods like Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2), which naturally accounts for dispersion. The analysis is situated within broader research on the performance of MP2 versus DFT for characterizing nonbonded interactions, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting appropriate computational tools.

Methodological Approaches: DFT Corrections vs. Wavefunction Methods

Empirical Dispersion Corrections for DFT

The most computationally efficient solution to DFT's dispersion problem has been the semi-empirical DFT-D approach, which adds a dispersion term to the density functional. [9] This correction typically takes the form of a long-range attractive pair-potential (proportional to R⁻⁶) multiplied by a damping function that deactivates it at short range where standard functionals behave correctly. [9] While this approach often provides qualitative and even quantitative improvements for non-polar molecules interacting primarily through dispersion, it can overbind systems where other interactions like hydrogen bonding are significant, potentially due to double-counting of correlation effects. [9]

Wavefunction-Based Alternatives

In contrast to empirically-corrected DFT, the MP2 method naturally includes dispersion interactions without empirical parameters as it incorporates electron correlation through perturbation theory. [6] However, MP2's dispersion energy can be overestimated because it uses the uncoupled Hartree-Fock dispersion energy that lacks repulsive intramolecular correlation correction. [6] Modern variants address this limitation:

- SCS-MP2: Spin-Component Scaled MP2 uses separate scaling factors for parallel- and anti-parallel-spin correlation energy components. [6]

- SOS-MP2: Scaled Opposite-Spin MP2 includes only the opposite-spin component with a scaling factor. [6]

These advanced wavefunction methods serve as valuable benchmarks for assessing empirically-corrected DFT approaches.

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Specialized benchmark databases have been developed to evaluate computational methods for nonbonded interactions. One study testing 44 DFT methods against databases for hydrogen bonding, charge transfer, dipole interactions, and weak interactions found that the MPWB1K functional delivered the best overall performance with an average relative error of 11%. [10]

Table 1: Best-Performing Methods for Different Interaction Types (Relative Errors)

| Interaction Type | Best-Performing Methods | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonding | PBE, PBE1PBE, B3P86, MPW1K, B97-1, BHandHLYP [10] | Combination of GGA and hybrid functionals |

| Charge Transfer | MPWB1K, MP2, MPW1B95, MPW1K, BHandHLYP [10] | MP2 and specialized hybrid functionals |

| Dipole Interactions | MPW3LYP, B97-1, PBE1KCIS, B98, PBE1PBE [10] | Primarily hybrid density functionals |

| Weak Interactions | MP2, B97-1, MPWB1K, PBE1KCIS, MPW1B95 [10] | MP2 outperforms most DFT approaches |

For high-accuracy reference data, the database of Jurečka et al. provides CCSD(T) complete basis set limit interaction energies and geometries for more than 100 DNA base pairs and amino acid pairs, serving as a gold standard for method validation. [11]

Case Study: Stannylene-Aromatic Complexes

A comprehensive benchmark study compared the performance of MP2-type methods and 14 DFT functionals for modeling interactions between stannylenes (SnX₂) and aromatic molecules (benzene and pyridine). [6] The study used CCSD and CCSD(T) results as reference data, providing stringent validation.

Table 2: Method Performance for Stannylene-Aromatic Complexes (Structures and Interaction Energies)

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Performance Assessment | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP2-Type Methods | SCS-MP2, SOS-MP2 [6] | Best overall performance; most accurate for structures and interaction energies [6] | Higher computational cost than DFT [6] |

| Range-Separated Hybrid DFT | ωB97X [6] | Good accuracy for structures and interaction energies [6] | Not as accurate as best MP2-type methods [6] |

| Dispersion-Corrected DFT | B3LYP-D2 [6] | Improved performance over uncorrected functionals [6] | Accuracy depends on system and correction parameters [6] |

| Standard Hybrid DFT | B3LYP, B98 [6] | Insufficient accuracy without dispersion correction [6] | Fails to describe dispersion-dominated interactions [6] |

The study concluded that range-separated hybrid or dispersion-corrected density functionals are necessary to describe interactions in stannylene-aromatic complexes with reasonable accuracy, though the best MP2-type methods still outperformed them. [6]

Case Study: Anisole Complexes in Ground and Excited States

Research on anisole complexes with water and ammonia highlights the challenging situation where hydrogen bonding and dispersive forces are both significant. [9] For the anisole-ammonia complex, the most stable structure is non-planar with ammonia interacting with the π-electron density of the aromatic ring (H⋯π complex). In this system, hydrogen bonding and dispersive forces provide comparable stabilization energy in the ground state. [9]

Standard B3LYP calculations predicted the H⋯π complex as most stable but with significant structural differences compared to MP2. When the dispersion correction was added to B3LYP (B3LYP-D), the computed structure became similar to its MP2 counterpart, though both placed ammonia slightly too close to anisole. [9] The best predictions were obtained using the computationally expensive counterpoise-corrected MP2 potential energy surface. [9]

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Benchmarking Workflow for Method Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the standardized protocol for assessing computational methods, as employed in rigorous benchmarking studies:

Diagram 1: Workflow for computational method validation, integrating high-level theoretical and experimental reference data.

Computational Details for Reliable Results

Based on the examined studies, proper benchmarking requires attention to several technical aspects:

Reference Data: High-level ab initio methods like CCSD(T) at the complete basis set (CBS) limit or experimental gas-phase data (rotational constants, vibrational spectra) provide reliable benchmarks. [11] [9]

Basis Set Selection: Moderately-sized basis sets with polarization functions are typically used, but Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) must be addressed through counterpoise correction, especially for weak interactions. [9]

Geometry Optimization: Full geometry optimizations should be performed at each level of theory being assessed, followed by frequency calculations to confirm true minima and provide zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) corrections. [9]

Energy Calculations: Single-point calculations at optimized geometries with higher-level methods or larger basis sets may improve accuracy, particularly when interaction energies are of primary interest.

Table 3: Key Computational Resources for Non-Covalent Interaction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Databases | GSCDB138, MGCDB84, Jurečka Database [11] [12] | Provide gold-standard reference data for method validation and development |

| Wavefunction Methods | MP2, SCS-MP2, CCSD(T) [6] [11] | High-accuracy reference methods that naturally include dispersion |

| Density Functionals | ωB97X, B3LYP-D, MPWB1K, PBE1PBE [6] [10] | Empirically-corrected DFT methods balancing cost and accuracy |

| Dispersion Corrections | Grimme D2, D3, D4 [6] [12] | Semi-empirical additions that improve DFT performance for weak interactions |

| Specialized Basis Sets | Correlation-consistent basis sets, Polarized basis sets | Atomic orbital sets providing accuracy for interaction energies |

The empirical treatment of dispersion in DFT remains an active field of research, with ongoing efforts focused on improving the accuracy and transferability of corrections while maintaining computational efficiency. [12] The development of new benchmark databases like the "Gold Standard Chemical Database 138" (GSCDB138) expands the chemical space for functional assessment, now including transition metal compounds and properties relevant to excited states. [12]

For researchers studying nonbonded interactions in drug development and materials science, the evidence suggests a tiered approach: dispersion-corrected DFT methods (particularly range-separated hybrids like ωB97X) offer the best compromise for screening and studying large systems, while MP2-type methods (especially SCS-MP2) provide higher accuracy for smaller systems where computational cost is manageable. As functional development continues and computational hardware advances through GPU acceleration and specialized algorithms, [13] the performance gap between empirically-corrected DFT and wavefunction methods will likely narrow, further expanding the capabilities available to the scientific community.

Noncovalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and halogen bonding, are fundamental forces governing molecular recognition, self-assembly, and stability in chemical and biological systems. Accurate prediction of their strength and nature is crucial for advancements in drug design, materials science, and catalysis. This guide objectively compares the performance of two prominent computational quantum chemistry methods—Møller-Plesset perturbation theory to second order (MP2) and Density Functional Theory (DFT)—in characterizing these interactions. The evaluation is framed within the broader thesis of identifying robust, accurate, and efficient protocols for modeling weak intermolecular forces, providing researchers with a clear comparison based on recent experimental and benchmark studies.

Performance Comparison of MP2 and DFT Methods

The performance of computational methods varies significantly across different types of nonbonded interactions. The following tables summarize key quantitative data from recent studies, comparing the accuracy of MP2 and various DFT functionals against high-level reference calculations.

Table 1: Performance on Radical and Multireference Systems (Verdazyl Radicals)

| Method | Type | Performance Notes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| M11 | DFT (Range-separated hybrid meta-GGA) | Top-performing for verdazyl radical dimer interaction energies [14] | Accurate description of multireference character |

| MN12-L | DFT (Local meta-GGA) | Top-performing for verdazyl radical dimer interaction energies [14] | Good performance at lower computational cost |

| M06 | DFT (Hybrid meta-GGA) | Top-performing for verdazyl radical dimer interaction energies [14] | Balanced accuracy for organics |

| M06-L | DFT (Local meta-GGA) | Top-performing for verdazyl radical dimer interaction energies [14] | Good performance without exact exchange |

| NEVPT2(14,8) | ab initio Multireference | Reference method for benchmarking [14] | High-accuracy benchmark for radical systems |

Table 2: Performance on Halogen and π-π Stacking Interactions

| Method | Interaction Type | Performance / Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| MP2 | General Noncovalent | Known to overestimate interaction energies, especially for π-π stacking [15] |

| DFT (with appropriate functional) | Halogen vs. π-π Stacking | Accurately identifies that π-stacked complexes are more stable than halogen-bonded ones for TMPD with IDNB [16] |

| SAPT0 | General Noncovalent | Used for large-scale generation of benchmark interaction energies (e.g., DES370K dataset) [17] |

Table 3: Performance for Thermochemical Properties (Enthalpies of Formation)

| Method | Basis Set | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) from Experiment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP2 | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | 18.3 kJ/mol [18] | Systematically overestimates stability (more negative ∆fH°) |

| B3LYP | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | 6.5 kJ/mol [18] | More accurate than MP2 for this property |

| M06-2X | 6-311+G(3df,2p) | 4.5 kJ/mol [18] | Top-performing DFT functional for this test |

| G4 (Composite) | - | ~1-4 kJ/mol [18] | High-accuracy reference |

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the data, this section outlines the key methodological details from the cited studies.

Benchmarking Multireference Verdazyl Radicals

The assessment of DFT functionals for verdazyl radical dimers followed a rigorous protocol [14]:

- Reference Method: The NEVPT2 method with an active space of 14 electrons in 8 orbitals ((14,8)) was used to generate benchmark interaction energies. This active space encompasses the verdazyl π orbitals critical for accurate description.

- System Preparation: Calculations were performed on verdazyl radical dimers extracted from crystalline structures.

- Benchmarked Methods: A range of DFT functionals, primarily from the Minnesota family, were evaluated against the NEVPT2 reference. Their performance was assessed by calculating interaction energies and singlet-triplet gaps.

- Additional Considerations: The study also explored the effects of using restricted open-shell Hartree-Fock (ROHF) and the addition of empirical dispersion corrections.

Distinguishing Halogen Bonds from π-π Stacking

The competition between halogen bonding and π-π stacking was deciphered through a combined experimental and theoretical approach [16]:

- Synthesis and Crystallization: Co-crystals of electron donors (TMPD, DHDAP) with halogenated acceptors (IDNB, DITFB, IPFB) were grown via slow evaporation from solvent mixtures.

- X-ray Crystallography: The solid-state structures of the co-crystals were determined to unambiguously identify the predominant intermolecular interaction mode (π-stacked or halogen-bonded).

- Computational Analysis (DFT): The interaction energies of the different possible 1:1 complexes (both π-stacked and halogen-bonded) were computed using DFT. The functionals used (e.g., M06-2X) were chosen for their good performance for noncovalent interactions. These calculations confirmed that the observed crystal structure corresponded to the more stable complex in each case.

Assessing Thermochemical Properties via Isodesmic Reactions

The accuracy of MP2 and DFT for enthalpies of formation was tested using isodesmic reaction schemes [18]:

- Reaction Design: The enthalpy of formation of a target molecule (e.g., CH₃ONO₂) is calculated using a balanced "work reaction" where the number and types of bonds are conserved. This allows for systematic error cancellation.

- Quantum Chemical Calculations: Single-point energy calculations are performed on all species in the isodesmic reaction using the method and basis set of interest (e.g., MP2/6-311+G(3df,2p)).

- Energy and Enthalpy Derivation: The electronic energy difference of the reaction (ΔE) is computed and converted to a reaction enthalpy (ΔH) at 298 K by incorporating thermal corrections from frequency calculations. The enthalpy of formation of the target is then derived using known experimental enthalpies of formation for the other molecules in the reaction.

- Error Analysis: The calculated enthalpies of formation are compared against reliable experimental data to determine the mean absolute deviation (MAD) and other error statistics.

Method Selection Workflow

The decision-making process for selecting an appropriate computational method is summarized in the workflow below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

This section lists key software, methods, and conceptual tools used in the featured studies for researching nonbonded interactions.

Table 4: Key Computational Reagents and Resources

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Functionals (e.g., M06-2X, M11) | DFT Functional | Accurate treatment of diverse noncovalent interactions and thermochemistry [14] [18] [19] | Predicting interaction energies in radical dimers [14] |

| SAPT (Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory) | Ab Initio Method | Decomposes interaction energy into physical components (electrostatics, dispersion, etc.) [17] | Generating benchmark data for force-field training [17] |

| Isodesmic/Homodesmotic Reactions | Computational Scheme | Cancels systematic errors in quantum chemistry calculations for accurate thermochemistry [18] | Calculating enthalpies of formation with near-chemical accuracy [18] |

| NEVPT2 (n-electron valence state perturbation theory) | Ab Initio Multireference Method | Provides high-accuracy reference data for systems with strong static correlation [14] | Benchmarking DFT performance for radical systems [14] |

| Machine Learning Potentials (e.g., CLIFF kernel) | Emerging Tool | Models ab initio data into continuous force fields for molecular dynamics simulations [17] | Creating accurate non-bonded force fields for organic polymers [17] |

Advanced MP2 Variants and DFT Corrections for Biological Systems

The accurate computation of noncovalent interactions is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, with profound implications for understanding molecular recognition in drug design, materials science, and supramolecular chemistry. For decades, second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) has served as a workhorse method for capturing electron correlation effects at a reasonable computational cost. However, standard MP2 suffers from systematic limitations, including an overestimation of dispersion interactions and an unbalanced treatment of electron pairs with different spin configurations. The advent of Spin-Component Scaled MP2 (SCS-MP2) methodologies has fundamentally addressed these shortcomings through empirical refinement of MP2's energy components. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of SCS-MP2 variants against standard MP2 and density functional theory (DFT) alternatives, demonstrating how these scalable, efficient methods deliver quantitative accuracy for nonbonded interactions critical to pharmaceutical research and development.

Theoretical Foundation: Rebalancing MP2's Spin Components

The fundamental innovation of SCS-MP2 lies in its separate scaling of the parallel-spin (same-spin, SS) and antiparallel-spin (opposite-spin, OS) contributions to the MP2 correlation energy [20] [21]. The standard MP2 correlation energy is expressed as:

[ E{c}^{\text{MP2}} = E{c}^{\text{OS}} + E_{c}^{\text{SS}} ]

The SCS-MP2 method modifies this expression by introducing two distinct scaling parameters [21]:

[ E{c}^{\text{SCS-MP2}} = c{\text{OS}}E{c}^{\text{OS}} + c{\text{SS}}E_{c}^{\text{SS}} ]

where (c{\text{OS}}) and (c{\text{SS}}) are empirically determined coefficients. The original SCS-MP2 parameterization proposed by Grimme used (c{\text{OS}} = 6/5) and (c{\text{SS}} = 1/3) [20] [21]. This approach corrects for the biased treatment of electron pairs at the Hartree-Fock level, where Fermi correlation between parallel-spin pairs is already incorporated, while Coulomb correlation between antiparallel spins is neglected [20]. The scaling procedure specifically reduces the often overestimated correlation of αα and ββ electron pairs, which primarily represent static (long-range) electron correlation effects [20].

Table 1: Fundamental SCS-MP2 Parameterizations

| Method Variant | (c_{\text{OS}}) | (c_{\text{SS}}) | Key Application Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard SCS-MP2 | 6/5 (1.2) | 1/3 (~0.333) | General chemistry applications [20] [21] |

| SOS-MP2 | 1.3 | 0 | Computational efficiency [21] |

| SCS-MP2 for Noncovalent Interactions | Varies by specific parametrization | Varies by specific parametrization | Weak intermolecular forces [2] |

Performance Benchmarking: SCS-MP2 vs Standard MP2 and DFT

Accuracy for Biomolecular Interaction Motifs

Recent comprehensive benchmarking against the gold-standard CCSD(T)/CBS (coupled cluster with complete basis set) method has demonstrated the superior performance of SCS-MP2 approaches. For a diverse set of 274 molecular systems encompassing hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking, halogen bonding, and dispersion-dominated interactions, specially calibrated SCS-MP2 methods achieved quantitative accuracy with errors below 1 kcal/mol [2]. This exceptional performance surpasses many non-dynamical electronic structure techniques and widely used hybrid and meta-GGA density functional approximations (DFAs). In drug design applications, where accurately modeling protein-ligand interactions is crucial, SCS-MP2 methods have proven particularly valuable for capturing the subtle energetics of CH-π, π-π stacking, cation-π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and salt bridges [22].

Quantitative Comparison with DFT Functionals

While DFT offers a favorable computational cost profile for large systems, its accuracy for noncovalent interactions varies dramatically based on the chosen functional. A systematic benchmarking study of nine widely used DFT functionals for protein kinase inhibitor interactions found that only the best-performing functionals (B3LYP/def2-TZVP and RI-B2PLYP/def2-QZVP with D3BJ dispersion correction) approached the reliability of high-level wavefunction methods [22]. Standard MP2 consistently overestimates interaction energies for π-system interactions, while SCS-MP2 corrects this systematic error without the parametrization challenges of dispersion-corrected DFT [20] [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Noncovalent Interactions (Mean Absolute Error in kcal/mol)

| Method | Hydrogen Bonding | π-π Stacking | Dispersion-Dominated | Mixed Interactions | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCS-MP2 (calibrated) | <1.0 [2] | <1.0 [2] | <1.0 [2] | <1.0 [2] | Medium-High |

| Standard MP2 | ~1.5-2.5 | ~2.0-4.0 | ~2.0-4.0 | ~2.0-3.5 | Medium |

| B3LYP-D3BJ/def2-TZVP | ~1.0-2.0 [22] | ~1.5-3.0 [22] | ~1.5-3.0 [22] | ~1.5-2.5 [22] | Low-Medium |

| Double-Hybrid DFT (B2PLYP) | ~0.8-1.8 [22] | ~1.0-2.0 [22] | ~1.0-2.0 [22] | ~1.0-1.8 [22] | Medium-High |

Geometries and Vibrational Frequencies

Beyond interaction energies, SCS-MP2 significantly improves the prediction of molecular geometries and harmonic vibrational frequencies compared to standard MP2. For a benchmark set of 29 small molecules, SCS-MP2 demonstrated uniform improvements over MP2 for equilibrium geometries, without deteriorating performance for systems already well-described by standard MP2 [20]. The method also successfully handles challenging cases such as transition metal compounds, weakly bonded complexes, and transition states, where standard MP2 often proves inadequate [20].

Computational Efficiency and Accelerated Implementations

While SCS-MP2 inherits the formal computational scaling of standard MP2 (O(N⁵)), modern implementations utilizing resolution-of-the-identity (RI) approximations dramatically enhance efficiency without sacrificing accuracy [2]. The RI-JK and RIJCOSX approaches apply the RI approximation to Coulomb (J) and exchange (K) integrals, with the latter combining RI treatment of Coulomb terms with numerical integration of exchange contributions [2]. These accelerated methods achieve substantial time savings while maintaining compatibility with spin-component scaling strategies.

For particularly large systems, the SOS-MP2 (Scaled-Opposite-Spin) variant reduces computational cost to O(N⁴) or less by completely neglecting the same-spin component [21]. This approximation is theoretically justified by the observed proportionality between OS and SS parts of MP2 correlated densities [21]. The development of linearly scaling local correlation implementations further extends the applicability of SCS-MP2 to biomolecular systems of relevant size [2].

SCS-MP2 Computational Evolution Diagram

Methodologies and Protocols for SCS-MP2 Implementation

Standard SCS-MP2 Calculation Workflow

Implementing SCS-MP2 calculations requires careful attention to methodological details. The following protocol ensures reliable results for noncovalent interaction energies:

Geometry Optimization: Begin with initial geometry optimization at the MP2/def2-SVP or DFT-D3 level to establish reasonable starting structures [23].

Single-Point Energy Calculations: Perform single-point energy calculations using the SCS-MP2 method with an appropriate basis set (recommended: def2-TZVP or def2-QZVP) [2] [22].

Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) Correction: Apply the counterpoise correction method to eliminate BSSE by calculating monomer energies using the dimer basis set [23].

Spin-Component Scaling: Apply the appropriate scaling parameters ((c{\text{OS}}) and (c{\text{SS}})) to the opposite-spin and same-spin correlation energy components [21].

Interaction Energy Calculation: Compute the interaction energy as: ∆E = Edimer - EmonomerA - E_monomerB + BSSE

For studies requiring maximum accuracy, the continued-fraction extrapolation scheme of Goodson can further refine results toward the Schrödinger limit [23].

Specialized Parametrizations for Specific Interactions

Recent advances have produced SCS-MP2 parametrizations tailored to specific interaction types:

- SCS-MP2-vdW: Optimized for van der Waals complexes [2]

- SCS(MI)-MP2: Designed for molecular interactions [2]

- SCS-MP2-hal: Specialized for halogen-containing compounds [2]

- SCSN-MP2: Another variant for noncovalent interactions [2]

These specialized methods often outperform the original SCS-MP2 parametrization for their target applications, demonstrating the flexibility of the spin-component scaling approach.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SCS-MP2 Calculations

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RI Approximation | Accelerates Coulomb integral evaluation | RI-MP2, RI-JK-MP2 [2] |

| Auxiliary Basis Sets | Enables density fitting in RI methods | def2 auxiliary sets [22] |

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Sets | Systematic basis set convergence | cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5) [2] [22] |

| Dunning's Basis Sets | Balanced accuracy/efficiency | cc-pVXZ series [22] |

| Counterpoise Correction | Eliminates basis set superposition error | Standard BSSE correction protocol [23] |

| Composite Methods | Approaches complete basis set limit | CBS extrapolations [23] [2] |

Spin-Component Scaled MP2 methods represent a significant advancement in the accurate computation of noncovalent interactions, effectively bridging the gap between standard MP2 and more computationally demanding coupled-cluster methods. The empirical scaling of opposite-spin and same-spin correlation energy components corrects systematic errors in standard MP2 while maintaining its computational efficiency and size-consistency. For drug discovery professionals and computational chemists, SCS-MP2 offers a practical compromise between the accuracy of CCSD(T) and the computational feasibility of DFT, particularly for applications involving π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and dispersion-driven molecular recognition. As accelerated implementations continue to evolve, SCS-MP2 methodologies are poised to become increasingly valuable tools for modeling the complex nonbonded interactions that underwrite biomolecular structure and function.

Quantum chemical calculations are fundamental to modern research in drug development and materials science, providing insights into molecular structure, reactivity, and noncovalent interactions. Among the most computationally demanding aspects of these calculations is the evaluation of two-electron integrals, which formally scales as O(N⁴) with system size. The Resolution-of-the-Identity (RI) approximation, also known as density fitting, has emerged as a powerful technique to accelerate these calculations dramatically while introducing only minimal errors [24] [25]. This method approximates the electron repulsion integrals by expanding products of basis functions in an auxiliary basis set, reducing the formal scaling and storage requirements [25].

Within the context of studying noncovalent interactions – crucial in drug binding and molecular recognition – the MP2 method has historically served as a principal quantum chemical method, though it suffers from strong basis set dependence and can overestimate dispersion interactions [26] [6]. The RI technique is particularly valuable in this context as it makes more accurate (but computationally expensive) wavefunction methods like MP2 and coupled-cluster theory practically applicable to larger systems relevant to pharmaceutical research [24] [6]. This guide provides an objective comparison of RI approximations, their performance characteristics, and implementation protocols to assist researchers in selecting optimal computational strategies.

Understanding RI Approximation Methods

The fundamental principle behind the RI approximation is the expansion of products of atomic orbital basis functions in an auxiliary basis set. Mathematically, this is represented as:

[\phi{i} \left({ \vec{{r} }} \right)\phi{j} \left({ \vec{{r} }} \right)\approx \sum\limitsk { c{k}^{ij} \eta_{k} (\mathrm{\mathbf{r} }) } ]

where φᵢ and φⱼ are orbital basis functions, ηₖ are auxiliary basis functions, and cₖⁱʲ are expansion coefficients determined by minimizing the residual repulsion [25]. This approximation allows the two-electron integrals to be expressed in terms of two- and three-index integrals rather than the conventional four-index integrals, leading to tremendous reductions in computational time and storage requirements [25].

Several variants of RI approximations have been developed, each optimized for different types of quantum chemical methods:

- RI-J: Accelerates only Coulomb integrals; default for non-hybrid DFT in ORCA [24] [25]

- RIJONX: Uses RI for Coulomb integrals but no approximation for exchange integrals [24]

- RI-JK: Applies RI to both Coulomb and exchange integrals; preferred for smaller systems requiring high accuracy [24] [27]

- RIJCOSX: Combines RI for Coulomb integrals with numerical integration for exchange; default for hybrid DFT in ORCA and more efficient for larger molecules [24] [27]

- RI-MP2: Specifically accelerates MP2 correlation energy calculations [24]

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the appropriate RI approximation based on the computational task and system size:

Comparative Performance Analysis of RI Methods

Performance Benchmarks Across Method Types

The performance characteristics of different RI approximations vary significantly based on the electronic structure method, system size, and desired accuracy. The following table summarizes key performance metrics for the main RI variants:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RI Approximation Methods

| RI Method | Primary Application | Speedup Factor | Auxiliary Basis | Typical Error | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI-J | GGA DFT | 10-100x | def2/J | < 0.1 mEh | Default for non-hybrid DFT [24] [25] |

| RI-JK | HF, Hybrid DFT | 10-50x | def2/JK | < 1 mEh | Small-medium molecules, high accuracy [24] [27] |

| RIJCOSX | HF, Hybrid DFT | 10-100x | def2/J | ~1 mEh | Large molecules, default for hybrid DFT [24] [27] |

| RI-MP2 | MP2 | 10-100x | def2-TZVP/C | Basis set dependent | All MP2 calculations [24] [6] |

| RIJONX | HF, Hybrid DFT | Moderate | def2/J | Coulomb only | When exchange must be exact [24] |

Accuracy Assessment for Different Molecular Properties

The errors introduced by RI approximations are generally systematic, making them particularly suitable for relative energy calculations such as binding energies, conformational energies, and reaction barriers where error cancellation occurs. For the S66 database of noncovalent interactions, which is highly relevant to drug development, RI-MP2 methods have demonstrated excellent performance when proper auxiliary basis sets are employed [26].

For RIJCOSX, the total error comprises both the RI error (dependent on auxiliary basis size) and the COSX error (dependent on integration grid size) [24]. Comparative studies between RI-JK and RIJCOSX have shown that both methods are efficient and accurate, with RI-JK potentially preferable for large-scale calculations on smaller molecules, while RIJCOSX excels for larger systems [27].

In the context of MP2 calculations for noncovalent interactions, which is particularly relevant for drug development, the RI approximation enables the application of more accurate variants such as SCS-MP2 (spin-component scaled MP2) that improve upon conventional MP2's tendency to overestimate dispersion interactions [26] [6]. The RI error in these methods is generally smaller than the basis set error, making it possible to achieve excellent accuracy with appropriate computational protocols [24].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard Implementation in ORCA

The following protocols describe the implementation of various RI approximations in the ORCA computational chemistry package, widely used in research environments:

Table 2: Implementation Protocols for RI Methods in ORCA

| Method | Keyword | Auxiliary Basis | Sample Input |

|---|---|---|---|

| RI-J | !RI (default for GGA) | def2/J | ! BP86 def2-TZVP def2/J |

| RI-JK | !RIJK | def2/JK | ! B3LYP def2-QZVP def2/JK RIJK |

| RIJCOSX | !RIJCOSX (default for hybrids) | def2/J | ! B3LYP def2-QZVP def2/J RIJCOSX |

| RI-MP2 | !RI-MP2 | def2-TZVP/C | ! RI-MP2 def2-TZVP def2-TZVP/C |

| RI-MP2 with RIJCOSX | !RI-MP2 RIJCOSX | Multiple | ! RI-MP2 def2-TZVP def2-TZVP/C RIJCOSX def2/J |

Assessment of RI Errors and Accuracy Verification

To ensure computational results are not adversely affected by RI approximations, the following verification protocol is recommended:

- Perform test calculations with and without the RI approximation (if computationally feasible) using the

!NORIkeyword for GGA DFT calculations [24] - Increase auxiliary basis set size using the

!AutoAuxkeyword or by selecting a larger predefined auxiliary basis [24] - Use decontracted auxiliary basis sets with the

!DecontractAuxkeyword, particularly for core properties [24] - For RIJCOSX, test different grid sizes using

!defgrid1(lowest) to!defgrid5(highest) to assess COSX grid sensitivity [24]

The memory requirements of RI implementations are significantly lower than canonical implementations, as demonstrated in recent complex-variable equation-of-motion coupled-cluster implementations where RI reduced memory demands while maintaining accuracy [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of RI approximations requires careful selection of computational "reagents" – the basis sets and auxiliary basis sets that define the computational model:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RI Calculations

| Reagent | Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| def2/J | Auxiliary basis | RI-J and RIJCOSX calculations | General purpose for Coulomb integrals [24] |

| def2/JK | Auxiliary basis | RI-JK calculations | Larger than def2/J; required for accurate exchange [24] |

| def2-TZVP/C | Auxiliary basis | RI-MP2 calculations | Specific to orbital basis set; multiple /C sets available [24] |

| SARC/J | Auxiliary basis | ZORA/DKH relativistic calculations | Decontracted for relativistic methods [24] |

| AutoAux | Algorithm | Automatic auxiliary basis generation | Creates customized auxiliary basis; improved in ORCA 4.0+ [24] |

Resolution-of-the-Identity approximations represent an essential tool for computational chemists and drug development researchers, enabling accurate quantum chemical calculations on biologically relevant systems with significantly reduced computational resources. The systematic comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that:

- RI-J should be the default choice for non-hybrid DFT calculations

- RIJCOSX provides the best balance of efficiency and accuracy for hybrid DFT on large systems

- RI-JK offers superior accuracy for smaller systems where computational cost is less critical

- RI-MP2 makes correlated wavefunction methods practically applicable to noncovalent interactions of relevance to pharmaceutical research

The errors introduced by RI approximations are generally systematic and smaller than basis set incompleteness errors, making them highly suitable for calculating relative energies such as binding affinities and conformational energies. With the ongoing development of more efficient algorithms and optimized auxiliary basis sets, RI methodologies continue to expand the scope of quantum chemical applications in drug discovery and materials science.

The accurate computational description of noncovalent interactions—such as van der Waals forces, π-π stacking, and hydrogen bonding—is fundamental to progress in drug development and materials science. These interactions, with energies typically ranging from 0.1 to 5.0 kcal/mol, govern molecular recognition, protein folding, and the stability of biological complexes [2]. For years, Density Functional Theory (DFT) has been the predominant quantum mechanical method for modeling such systems due to its favorable cost-to-accuracy ratio. However, standard DFT approximations fail to describe dispersion interactions, necessitating the development of dispersion-corrected methods [6].

This landscape has evolved from simple empirical corrections like Grimme's D2 and D3 applied to popular functionals such as B3LYP, to more sophisticated approaches like double-hybrid (DH) functionals that incorporate wavefunction-based correlation energy [29] [30]. Concurrently, wavefunction-based methods, particularly Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2) and its spin-scaled variants, have remained important benchmarks, offering a theoretically distinct path for capturing electron correlation effects crucial for nonbonded interactions [2] [6].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the modern dispersion-corrected DFT landscape, frames their performance against MP2-based methods, and details the experimental protocols used for their validation, providing drug development scientists with the tools to select the optimal method for their research.

The Jacob's Ladder of Density Functionals

Density functionals are often classified via "Jacob's Ladder," a metaphor ranking approximations from simple to complex based on their ingredients [30]. The progression toward chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol) is achieved by climbing the rungs:

- Rung 1 (LDA): Uses only the local electron density. Not suitable for molecular chemistry.

- Rung 2 (GGA): Incorporates the density gradient. Examples include PBE and BLYP.

- Rung 3 (meta-GGA): Adds the kinetic energy density. Examples include SCAN and TPSS.

- Rung 4 (Hybrid): Mixes in a portion of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange. B3LYP is the iconic functional of this class.

- Rung 5 (Double-Hybrid): Incorporates both HF exchange and a perturbative correlation energy term from MP2. B2PLYP and PBE-DH-INVEST are key examples [29] [30].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these method classes and their connection to wavefunction-based approaches.

The Role of MP2 and Spin-Component Scaling

Second-order Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2) is the simplest post-Hartree-Fock method that accounts for electron correlation. It is free from spurious self-interaction error and naturally captures dispersion interactions, but it often overestimates their strength [2] [6].

To correct this, Spin-Component Scaled MP2 (SCS-MP2) was introduced, applying separate empirical scaling factors to the same-spin (SS) and opposite-spin (OS) components of the MP2 correlation energy [2] [6]. This approach significantly improves accuracy for noncovalent interactions and thermochemistry. Further refinements have led to highly efficient and accurate methods like RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ, which uses the Resolution of the Identity (RI) and "chain-of-spheres" exchange (COSX) approximations for speed, and is specifically calibrated for biological weak interactions (BWI) [2].

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Data

Performance on Transition Metal Complexes: The Porphyrin Case Study

Metalloporphyrins are biologically critical complexes (e.g., heme in hemoglobin) and are notoriously challenging for computational methods due to nearly degenerate spin states [31]. A 2023 benchmark study of 250 electronic structure methods on the Por21 database revealed several key trends [31].

Table 1: Top-Performing Density Functionals for the Por21 Database (Metalloporphyrins)

| Functional Name | Type | Grade | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE, kcal/mol) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAM | GGA | A | < 15.0 | Overall best performer |

| revM06-L | meta-GGA (Local) | A | < 15.0 | Best compromise for general properties & porphyrins |

| M06-L | meta-GGA (Local) | A | < 15.0 | Good performance for transition metals |

| r2SCAN | meta-GGA (Local) | A | < 15.0 | Modern, non-empirical functional |

| HCTH | GGA | A | < 15.0 | Multiple parameterizations performed well |

| B3LYP-D3 | Hybrid GGA + Dispersion | C | ~23.0 | Popular but moderately accurate |

The study concluded that local functionals (GGAs and meta-GGAs) and global hybrids with a low percentage of exact exchange were the least problematic. In contrast, functionals with high percentages of exact exchange, including range-separated and double-hybrid functionals, often led to "catastrophic failures" for these systems [31]. This is a critical consideration for researchers modeling catalysts or metalloenzymes in drug discovery.

Performance on Noncovalent Interactions and Excited States

For noncovalent interactions in organic systems, double-hybrid functionals and scaled MP2 methods excel. A 2025 study introduced PBE-DH-INVEST and its spin-scaled variant SOS1-PBE-DH-INVEST, which are tailored for predicting singlet-triplet energy gaps (ΔEST) in "INVEST" molecules—systems where the singlet excited state is lower in energy than the triplet state, which is relevant for OLED development [29].

These functionals overcome a key limitation of standard time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) by naturally incorporating contributions from double excitations, allowing for the correct prediction of negative ΔEST values. They offer an accurate alternative to more costly wavefunction methods for high-throughput screening of emissive materials [29].

For ground-state weak interactions in biological systems, scaled MP2 methods are highly competitive. The RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ method was benchmarked on a dataset of 274 dimerization energies and achieved quantitative accuracy with errors below 1 kcal/mol compared to CCSD(T)/CBS reference data, surpassing many state-of-the-art density functional approximations [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Weak Noncovalent Interactions

| Method | Type | Key Features | Reported Error vs. CCSD(T) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ | Scaled WFT | Optimized for biological weak interactions | < 1.0 kcal/mol [2] | High, but efficient vs. canonical MP2 |

| Double-Hybrids (e.g., DSD-BLYP-D3) | DH DFT + Dispersion | High-accuracy for main-group thermochemistry | Low (Recommended) [30] | High (O(N⁵)) |

| Range-Separated Hybrids (e.g., ωB97M-V) | Hybrid DFT + Dispersion | Good balance of cost/accuracy | Excellent [2] | Medium-High |

| B3LYP-D3 | Hybrid GGA + Dispersion | Widely used, general purpose | Moderate [6] | Medium |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of benchmark results, the following section details the standard computational protocols employed in the cited literature.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking on the Por21 Database

This protocol is designed for assessing methods on transition metal porphyrin spin states and binding energies [31].

- System Preparation: The Por21 database is used, which contains high-level CASPT2 reference energies for iron, manganese, and cobalt porphyrins.

- Geometry and Single-Point Calculations: Molecular geometries are typically taken from literature or optimized at a lower level of theory. Single-point energy calculations are then performed with the method(s) being tested.

- Error Calculation: The key metric is the Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) in kcal/mol, calculated against the CASPT2 reference data for spin-state energy differences (PorSS11 subset) and binding energies (PorBE10 subset). The overall grade is based on the MUE for the combined Por21 database.

- Analysis: Functionals are ranked and graded (A-F), with an MUE of 23.0 kcal/mol representing the threshold for a passing grade (D). The chemical accuracy target is 1.0 kcal/mol.

Protocol 2: Assessing Weak Interactions in Biological Dimers

This protocol validates methods for predicting dimerization energies, crucial for biomolecular modeling [2].

- Reference Data Curation: A diverse set of 274 molecular dimers is compiled, encompassing hydrogen bonds, π-π stacking, halogen bonding, and dispersion-dominated interactions. The reference interaction energies are computed at the CCSD(T)/CBS level (the gold standard).

- Geometry Optimization: Dimer and monomer geometries are optimized at a reliable level of theory, such as DFT with a medium-sized basis set.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: The interaction energy is calculated as the difference between the dimer energy and the sum of the isolated monomer energies, using the target method (e.g., RI-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ, double-hybrid DFT). The counterpoise correction is applied to account for basis set superposition error (BSSE).

- Validation: The calculated interaction energies are compared to the CCSD(T)/CBS benchmark. Methods with MUEs below 1 kcal/mol are considered quantitatively accurate.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Singlet-Triplet Energy Gaps in INVEST Systems

This protocol tests methods for predicting excited-state properties relevant to photophysical applications [29].

- Dataset Selection: The NAH159 dataset is used, which includes 159 derivatives of azulene, heptazine, cyclazine, and other scaffolds known to exhibit inverted singlet-triplet gaps (ΔEST < 0).

- Excitation Energy Calculation: The vertical excitation energies for the first singlet (S₁ ← S₀) and triplet (T₁ ← S₀) states are computed. For double-hybrid functionals, this involves a correction to standard TD-DFT energies to account for double excitations: Ω = Ω′ + aₐΔ(D), where Ω′ is the TD-DFT energy and Δ(D) is the double excitation contribution.

- Gap Calculation and Validation: The singlet-triplet gap is calculated as ΔEST = E(S₁) - E(T₁). The sign and magnitude of the predicted ΔEST are compared against high-level wavefunction reference data or experimental results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

The following table details key "research reagents"—software, basis sets, and dispersion corrections—essential for conducting the types of studies described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dispersion-Corrected Simulations

| Reagent / Solution | Type | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aug-cc-pVNZ (aVNZ) | Basis Set Family | Correlation-consistent basis sets for accurate post-HF and DFT calculations. The "aug-" prefix adds diffuse functions, vital for anions and noncovalent interactions [2] [32]. |

| def2 Basis Sets | Basis Set Family | Popular, efficient basis sets for DFT calculations across the periodic table. Often used with matching auxiliary basis sets for RI approximations [6]. |

| Grimme's D3/D3(BJ) | Dispersion Correction | Adds semi-empirical dispersion energy to DFT. D3(BJ) includes Becke-Johnson damping, improving performance at short ranges. A mandatory addition for most non-hybrid and hybrid functionals [30] [6]. |

| Resolution of Identity (RI) | Computational Acceleration | Approximates four-center electron repulsion integrals using an auxiliary basis set, dramatically speeding up MP2 and DH-DFT calculations with minimal accuracy loss [2] [30] [6]. |

| COSMO | Solvation Model | A continuum solvation model that approximates the solvent as a polarizable continuum, allowing for more realistic simulations in biological environments [32]. |

The landscape of dispersion-corrected DFT is rich and varied, with no single functional dominating all application areas. For transition metal systems like metalloporphyrins, modern local meta-GGAs (e.g., revM06-L, r2SCAN) are the most robust, while standard double-hybrids often fail [31]. In contrast, for organic noncovalent interactions and excited states, the latest double-hybrid functionals (PBE-DH-INVEST) and efficiently accelerated SCS-MP2 methods (RIJCOSX-SCS-MP2BWI-DZ) achieve near-quantitative accuracy, rivaling and sometimes surpassing the best DFAs [29] [2].

For drug development professionals, the choice of method must balance accuracy, system size, and chemical composition. This guide provides the comparative data and detailed protocols needed to make an informed decision, underscoring that the ongoing dialogue between DFT and wavefunction-based MP2 methods continues to drive the field toward greater predictive power.

Predicting the behavior of complex biological systems, such as a drug molecule binding to its protein target or the stacking of DNA base pairs, requires quantum mechanical (QM) methods that can accurately describe noncovalent interactions (NCIs). These interactions, including dispersion forces, hydrogen bonding, and π-π stacking, are fundamental to structural biology and drug design, yet they pose a significant challenge for computational methods. Among wave function theory (WFT) approaches, second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) has long been a principal method for treating NCIs at a reasonable computational cost. However, its performance must be critically evaluated against higher-level benchmarks and compared to modern density functional theory (DFT) alternatives, especially in the context of biologically relevant systems like ligand-pocket complexes and nucleic acids. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of MP2 and its variants against DFT and higher-level coupled cluster methods, supplying researchers with the data and protocols needed to select the most appropriate method for their specific application.

Performance Comparison: MP2 vs. DFT and CCSD(T) Benchmarks

Quantitative Performance Assessment for Noncovalent Interactions

Table 1: Overall Performance of Quantum Chemical Methods for Noncovalent Interactions

| Method | Class | Typical Error vs. CCSD(T) | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2 | WFT | ~35% overestimation for dispersion [26] [33] | Medium | Good for H-bonding, reasonable cost | Systematic overestimation of dispersion |

| SCS-MP2 | WFT (Scaled) | Significant improvement over MP2 (1.5-2x error reduction) [26] | Medium-High | Reduced basis set dependence, balanced performance | Parameterization may affect transferability |

| LMP2/SCS-LMP2 | WFT (Local) | Comparable to (SCS-)MP2 [34] | Lower than canonical MP2 | Applicable to larger systems | Additional approximations in localization |

| Double-Hybrid DFT | DFT (e.g., DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ)) | High accuracy, often most reliable [35] | High (MP2-like) | Excellent for thermochemistry & NCIs | Highest cost among DFT methods |

| Hybrid DFT | DFT (e.g., ωB97X-V, PW6B95-D3(BJ)) | Good accuracy with dispersion correction [35] | Medium | Good balance of accuracy/cost for large systems | Performance varies with functional |

| Meta-GGA DFT | DFT (e.g., SCAN-D3(BJ)) | Moderate accuracy [35] | Low-Medium | Lower cost than hybrids | Less reliable than hybrids/double-hybrids |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | WFT | Gold Standard (reference) | Very High | Highest achievable accuracy | Prohibitive for most biomolecular systems |

Specific Performance in Biological Contexts

Table 2: Performance for Specific Biological Interaction Types

| System Type | MP2 Performance | SCS-MP2 Improvement | Recommended DFT Alternatives | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene Dimers (π-π Stacking) | Overestimates attraction by 21-31% vs. CCSD(T) [33] | Not specifically reported for this system | Double-hybrid functionals with dispersion corrections [35] | [33] |

| Naphthalene Dimers (Larger π-Systems) | Overestimates attraction by 29-38% vs. CCSD(T) [33] | Not specifically reported for this system | Double-hybrid functionals with dispersion corrections [35] | [33] |

| DNA Base Pair Stacking | Overestimation similar to benzene/naphthalene systems | SCSN-MP2 (nucleic acid-optimized) shows improved performance [34] | DFT methods with explicit dispersion corrections | [36] [34] |

| General Organic/Biomolecular Motifs | Errors generally below ~35% but systematic [26] | Overall errors reduced by factors of 1.5-2 [26] | ωB97X-V, M052X-D3(0), PW6B95-D3(BJ) [35] | [26] [35] |

| Ligand-Pocket Interactions | Not specifically benchmarked in QUID | Not specifically benchmarked in QUID | Several dispersion-inclusive DFAs perform well in QUID benchmark [37] | [37] |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Standard Benchmarking Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure reliable assessments of quantum chemical methods, researchers have established rigorous benchmarking protocols:

Database Validation Using S66 and Related Datasets: The S66 database of interaction energies provides reference data for assessing methodological performance on biologically relevant binding motifs [26]. This database contains 66 biologically relevant noncovalent complexes with accurate reference interaction energies. Standard protocol involves:

- Single-point energy calculations at optimized geometries using the method of interest

- Comparison with CCSD(T)/CBS reference values from the database

- Statistical analysis of errors (MAE, RMSD) across the entire dataset

- Separate analysis of different interaction types (hydrogen bonding, dispersion-dominated, mixed)

The QUID Benchmark Framework for Ligand-Pocket Interactions: The recently developed "QUID" (QUantum Interacting Dimer) benchmark framework addresses the need for robust QM benchmarks specifically for ligand-pocket systems [37]. This protocol involves:

- Selection of 170 chemically diverse molecular dimers (42 equilibrium, 128 non-equilibrium) modeling ligand-pocket motifs

- Establishment of a "platinum standard" through agreement between LNO-CCSD(T) and FN-DMC methods, reducing uncertainty to ~0.5 kcal/mol

- Analysis across equilibrium and non-equilibrium geometries to assess method transferability