Multireference Perturbation Methods for Bond Breaking: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multireference perturbation theory (MRPT) methods for accurately modeling chemical bond breaking, a critical process in catalysis and drug discovery.

Multireference Perturbation Methods for Bond Breaking: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multireference perturbation theory (MRPT) methods for accurately modeling chemical bond breaking, a critical process in catalysis and drug discovery. We explore the foundational principles that make single-reference methods fail for bond dissociation and introduce key MRPT approaches like CASPT2 and NEVPT2. The article delves into methodological advancements, including state-specific and multi-state formulations, and offers practical troubleshooting for common challenges like intruder states and size-consistency. Finally, we present a comparative validation of various MRPT methods against benchmark full configuration interaction data, assessing their performance for single, double, and triple bond breaking in hydrocarbons, providing crucial insights for researchers in biomedical and clinical research.

Why Single-Reference Methods Fail: The Fundamental Need for MRPT in Bond Breaking

The Quantum Mechanical Challenge of Bond Dissociation

Accurate simulation of chemical bond dissociation represents one of the most persistent challenges in quantum chemistry and computational materials science. While conventional electronic structure methods provide reasonable accuracy for molecules near their equilibrium geometries, these methods progressively lose accuracy as bonds are stretched toward dissociation [1]. This fundamental limitation has profound implications across chemical sciences, particularly in catalysis, materials design, and drug development where understanding bond-breaking processes is essential for predicting reaction mechanisms and material properties.

The core of the challenge lies in the phenomenon of strong electron correlation, which emerges when multiple orbital energy levels converge in energy at stretched bond lengths [1]. This convergence yields exponentially many Slater determinants in the ground state with large coefficients, creating a computational complexity that overwhelms traditional single-reference quantum chemistry methods. This seems counter-intuitive, as one might assume that electrons associated with different nuclei would interact less as the bond is stretched, making the Hamiltonian easier to simulate. In reality, the opposite occurs because at large interatomic distances, the Coulomb repulsion becomes significant compared to the translational symmetry that creates the bond, leading to strongly correlated behavior that cannot be captured by single-reference methods [1].

Quantum Mechanical Foundations of the Challenge

The Strong Correlation Problem

At the heart of the bond dissociation problem is the failure of the independent-electron approximation. In quantum mechanical terms, as a bond stretches, the electronic wavefunction undergoes a fundamental transformation from a single-determinant dominated description to a multi-determinant state where multiple electronic configurations contribute significantly. This transition manifests mathematically as the inability of methods like Hartree-Fock, MP2, CISD, and CCSD to accurately describe the ground state energy as bond length increases, as famously demonstrated in N₂ dissociation curves [1].

The non-relativistic electronic molecular Hamiltonian in second quantization is:

Ĥ = ∑ₚqᴺ hₚqÊₚq + ½∑ₚqrsᴺ Vₚqrŝeₚqrs + Vₙₙ

Where Êₚq and eₚqrs are spin-summed one- and two-electron excitation operators, hₚq and Vₚqrs are one- and two-electron integrals, and Vₙₙ is the nuclear repulsion energy [2]. Accurately solving this Hamiltonian using standard electronic structure methods scales either polynomially 𝒪(Nˣ) or exponentially 𝒪(eᴺ) with system size, creating an intractable computational problem for strongly correlated systems [2].

Failure of Single-Reference Methods

Single-reference quantum chemistry methods fail dramatically at dissociation limits because they cannot adequately describe the degenerate or near-degenerate electronic states that emerge. As bonds stretch, the energy gap between highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals decreases, leading to near-degeneracy effects that require a multi-reference treatment. The mean-field potential approximation, which works reasonably well when the electronic distribution doesn't vary significantly, breaks down completely at large interatomic distances where the electronic distribution undergoes substantial reorganization [1].

Table 1: Performance Degradation of Quantum Chemistry Methods at Bond Dissociation

| Computational Method | Performance at Equilibrium | Performance at Dissociation | Primary Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Reasonable for stable molecules | Severe energy error | Missing electron correlation |

| Møller-Plesset (MP2) | Good for weak correlation | Qualitative failure | Diverges due to near-degeneracy |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD) | Excellent near equilibrium | Progressive deterioration | Inadequate for strong correlation |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Variable depending on functional | Systematic error | Self-interaction error |

Computational Methodologies for Bond Dissociation

Multireference Wavefunction Methods

Multireference methods provide the most mathematically rigorous approach to strong correlation by explicitly treating multiple electronic configurations simultaneously. The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) method forms the foundation of modern multireference quantum chemistry, providing a variational treatment of static correlation within a selected active space of orbitals and electrons. However, CASSCF and related methods face exponential scaling with active space size, limiting practical applications to approximately 20 electrons in 20 orbitals—the so-called "CAS(20,20) limit" [2].

The exponential scaling arises from the factorial growth of the number of configuration state functions with system size. For a CASSCF calculation with N electrons in M orbitals, the number of configurations scales as the number of ways to distribute N electrons among M orbitals, creating a computational bottleneck that has driven the development of alternative approaches including selective configuration interaction, density matrix renormalization group, and quantum Monte Carlo methods.

Embedding and Fragmentation Strategies

Quantum embedding theories have emerged as powerful strategies for overcoming the scaling limitations of multireference methods by partitioning complex systems into smaller, more manageable subsystems. These approaches leverage the locality of strong correlation, where chemically interesting phenomena are often confined to specific regions of a larger molecular system [2].

Table 2: Quantum Embedding Methods for Strong Correlation

| Embedding Method | Quantum Variable | Partitioning Scheme | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) | Density Matrix | Fock Space | Point defects, transition metal complexes [2] |

| Dynamical Mean Field Theory (DMFT) | Green's Function | Real Space | Solid-state systems, extended materials [2] |

| Self-Energy Embedding Theory (SEET) | Self-Energy | Fock Space | Molecular systems, correlated materials [2] |

| Wavefunction-in-DFT | Electron Density | Real Space | Reactions in complex environments [2] |

Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) has shown particular promise for chemical applications, providing a conceptually simpler and computationally efficient alternative to DMFT [2]. In DMET, the system is partitioned into fragments, and each fragment is embedded in a bath constructed from the environment, yielding a significantly reduced quantum problem that can be solved with high-level methods. Recent applications have demonstrated DMET's effectiveness for challenging problems including point defects in solids, spin-state energetics in transition metal complexes, magnetic molecules, and molecule-surface interactions [2].

Force Field and Machine Learning Approaches

Classical molecular dynamics with reactive force fields provides an alternative strategy for simulating bond dissociation, particularly for large systems and extended timescales inaccessible to quantum methods. Traditional fixed-bond force fields like CHARMM, CVFF, and PCFF use harmonic bonding potentials that prevent bond dissociation, while reactive force fields like ReaxFF implement bond-order concepts that allow bonds to break and form during simulation [3].

Recent innovations have integrated complete bond dissociation into Class II force fields by replacing harmonic bonding terms with Morse potentials and deriving compatible cross-term interactions. This reformulation, termed "ClassII-xe," combines the stability of fixed-bond models with the reactive capabilities of bond-breaking force fields, enabling accurate molecular dynamics predictions across crystalline, semi-crystalline, and amorphous organic systems [3].

Machine learning, particularly quantum machine learning (QML), offers emerging capabilities for bond dissociation energy prediction. Recent benchmarking studies have shown that quantum models like Quantum Convolutional Neural Networks (QCNN) and Quantum Random Forests (QRF) can achieve accuracy comparable to classical machine learning for mid-range bond dissociation energies (70-100 kcal/mol) relevant to practical chemistry [4]. These approaches leverage quantum feature maps to capture complex, high-dimensional relationships that may remain elusive to classical kernels, potentially providing advantages for modeling molecular properties governed by quantum effects.

Quantum Computing Approaches

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms

The emergence of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers has stimulated development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms for electronic structure problems. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has shown particular promise for quantum chemistry applications, using a parameterized quantum circuit to prepare trial wavefunctions and classical optimization to minimize the energy expectation value [2].

In the context of bond dissociation, VQE and related algorithms face significant challenges including barren plateaus, optimization difficulties, and hardware limitations. However, their theoretical polynomial scaling for strongly correlated systems provides motivation for continued development. Recent work has integrated DMET with active-space multireference quantum eigensolvers, creating pathways for quantum advantage in chemical simulation [2].

Resource Requirements and Limitations

Current quantum computing approaches face substantial resource constraints for bond dissociation problems. The number of qubits required scales with the size of the active space, while circuit depth depends on the complexity of the ansatz and the number of optimization steps. For near-term applications, active spaces of 10-20 orbitals represent a realistic target, sufficient for many single-bond dissociation processes but inadequate for complex molecular systems with extended conjugation or multiple correlated regions.

Error mitigation techniques including zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, and symmetry verification are essential for obtaining meaningful chemical accuracy on current hardware. The integration of quantum error correction represents a longer-term goal that will eventually enable arbitrarily accurate quantum chemical calculations.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Density Matrix Embedding Theory Protocol

System Preparation:

- Molecular Geometry Input: Provide Cartesian coordinates for all atoms in the system

- Basis Set Selection: Choose appropriate atomic orbital basis set (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ)

- Mean-Field Calculation: Perform Hartree-Fock or DFT calculation to obtain initial orbitals

- Localization: Transform canonical orbitals to localized basis (e.g., Boys, Pipek-Mezey)

Fragment Definition:

- Active Space Selection: Identify chemically relevant fragments based on atomic composition

- Bath Construction: Compute bath orbitals from environment using singular value decomposition of the fragment-environment block of the density matrix

- Embedded Hamiltonian Construction: Project full system Hamiltonian into fragment-plus-bath space

High-Level Calculation:

- Wavefunction Solution: Solve embedded Hamiltonian using high-level method (CASSCF, DMRG, VQE)

- Self-Consistency Loop: Iteratively update the embedding potential until fragment density matrices converge

- Property Evaluation: Compute energies, densities, and other properties from converged solution

This protocol enables accurate treatment of strong correlation in bond dissociation while maintaining computational feasibility for large systems [2].

Classical Force Field with Bond Dissociation

Force Field Reformulation:

- Bond Potential Replacement: Substitute harmonic bonding terms with Morse potential: V(r) = Dₑ[1 - exp(-α(r - r₀))]²

- Cross-Term Modification: Reformulate bond/bond, bond/angle, and angle/angle cross-terms to exponential form compatible with Morse potential

- Parameter Derivation: Extract parameters (Dₑ, α, r₀) from quantum chemical calculations or experimental data

- Validation: Benchmark against crystalline, semi-crystalline, and amorphous systems

Molecular Dynamics Protocol:

- System Equilibration: Perform NPT equilibration to target temperature and pressure

- Mechanical Deformation: Apply strain or deformation to induce bond dissociation

- Property Monitoring: Track stress, energy, and bonding topology during simulation

- Analysis: Compute mechanical properties, failure mechanisms, and damage propagation [3]

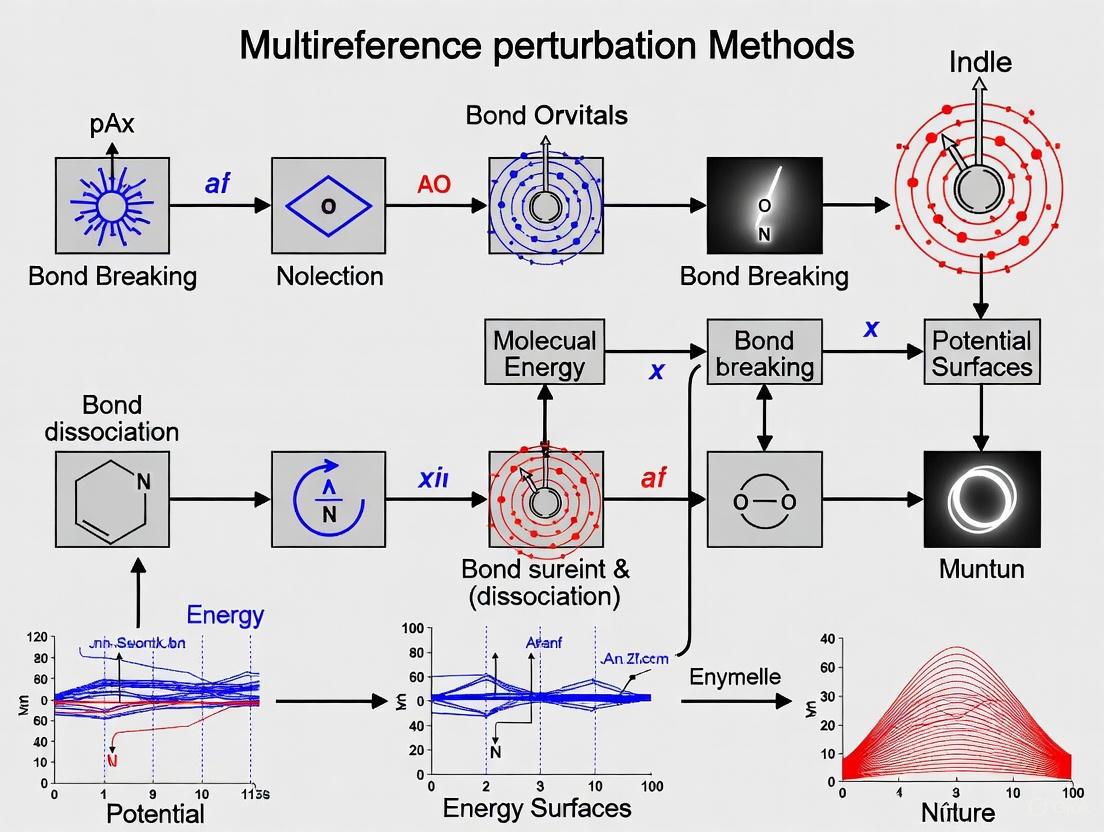

Visualization of Methodologies

Diagram 1: Computational ecosystem for bond dissociation challenges, showing the relationship between fundamental quantum mechanical problems and computational solutions with their applications.

Diagram 2: Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) self-consistent workflow for bond dissociation problems, showing the iterative process between quantum mechanical regions and their environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Bond Dissociation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Software | PySCF, Molpro, ORCA, Q-Chem | Multireference wavefunction calculations | Method development, benchmark studies |

| Embedding Implementations | DMET, Vayesta, PyEmbedding | Quantum embedding calculations | Large system multireference problems |

| Quantum Computing Platforms | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Quantum algorithm implementation | Quantum advantage exploration |

| Force Field Packages | LAMMPS, GROMACS, AMBER | Molecular dynamics with bond dissociation | Large-scale reactive simulations |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow Quantum, Scikit-Learn | QML model development | Bond dissociation energy prediction |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, Jupyter Notebooks | Data analysis and visualization | Results interpretation and presentation |

The quantum mechanical challenge of bond dissociation remains a vibrant research area at the intersection of quantum chemistry, materials science, and computer science. While multireference methods provide the most rigorous theoretical foundation, their computational cost has driven innovation in embedding theories, force field development, and quantum algorithms. The integration of these approaches—particularly through quantum-classical hybrid algorithms—represents the most promising path forward for achieving both accuracy and scalability.

Future progress will likely come from several directions: improved active space selection algorithms for multireference calculations, more efficient quantum embeddings with reduced double-counting errors, better integration of machine learning with quantum chemistry, and advances in quantum hardware that enable larger, more accurate simulations. Each of these developments will expand our ability to model bond dissociation processes, ultimately enabling more accurate predictions of chemical reactivity, material properties, and biological function across the molecular sciences.

The accurate computational description of chemical bonds, particularly their formation and breaking, represents a fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry. This challenge is central to research on reaction mechanisms, transition metal catalysts, and molecular magnetism. The Hartree-Fock method, which approximates the many-electron wavefunction as a single Slater determinant, provides a foundational model. However, it fails dramatically in cases of bond dissociation and systems with near-degenerate electronic states, where the true wavefunction is a superposition of multiple electronic configurations [5]. This failure originates from the neglect of static (or non-dynamical) electron correlation.

Static correlation is a "permanent" electron correlation effect associated with electrons occupying different spatial orbitals to avoid each other [5]. It becomes critically important when different orbital configurations have similar energies (near-degeneracy), making it impossible to describe the system with a single dominant determinant. This article explores the concept of static correlation within the context of advanced multireference perturbation methods, providing a technical guide for researchers investigating complex electronic structures in bond-breaking processes.

Theoretical Foundation: Defining Static and Dynamic Correlation

The Physical Meaning of Static Correlation

In single-reference systems like the water molecule near its equilibrium geometry, the Hartree-Fock determinant typically accounts for over 95% of the exact wavefunction. In contrast, for multi-reference systems, the weight of the leading determinant (C₀²) can become very small. A classic example is the Cr₂ molecule, where the Hartree-Fock determinant weight is only about 10⁻⁸, indicating a strongly correlated system dominated by static correlation [5].

The wavefunction for such a system is a superposition of multiple configurations: |Ψ⟩ = ∑ᵢ Cᵢ |i⟩, where the sum of squared coefficients (Cᵢ²) equals 1 [5]. This superposition does not mean that some molecules in an ensemble are in one configuration and others in another. Rather, each individual molecule exists in a quantum-mechanical mixture of these configurations simultaneously [5]. This mixed character has direct physical consequences:

- Fractional Orbital Occupations: When the one-electron density matrix is diagonalized to yield natural orbitals, these orbitals possess fractional occupation numbers, not integers close to 2 or 0 [5].

- Electron Avoidance: The multi-configurational description allows electrons to avoid each other more effectively on a "permanent" basis, rather than just through instantaneous dynamical correlations [5].

Contrasting Correlation Types

Table 1: Key Differences Between Static and Dynamic Correlation

| Feature | Static Correlation | Dynamic Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Origin | Near-degeneracy of electronic configurations | Instantaneous electron-electron Coulomb repulsion |

| Electron Behavior | "Permanent" avoidance by occupying different orbitals | Short-range correlated motion |

| Dominant in | Bond breaking, diradicals, transition metal complexes | Closed-shell molecules at equilibrium geometry |

| Wavefunction | Requires multiple determinants | Single determinant often sufficient |

| Treatment | MCSCF, CASSCF, VB | MP2, CCSD(T), DFT |

Computational Methods for Static Correlation

Multi-Configurational Self-Consistent Field (MCSCF)

The MCSCF method extends beyond Hartree-Fock by expressing the wavefunction as a linear combination of multiple determinants. The Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) approach is a specific flavor where the multi-configurational wavefunction is defined by partitioning molecular orbitals into inactive (doubly occupied), active (partially occupied), and virtual (unoccupied) spaces [6]. A CASSCF calculation is defined by its active space, denoted as CAS(n,m), where n is the number of active electrons and m is the number of active orbitals [6].

In CASSCF, both the configuration interaction (CI) coefficients and the molecular orbitals are optimized simultaneously to minimize the energy [6]. In contrast, a CASCI calculation keeps the orbitals fixed (typically from a Hartree-Fock calculation) and only optimizes the CI coefficients [6].

The Active Space Selection Challenge

Selecting an appropriate active space is arguably the most critical step in a CASSCF calculation. The active space must be large enough to capture the essential static correlation but small enough to be computationally tractable. The exponential scaling of the method limits practical calculations to active spaces of roughly 18 electrons in 18 orbitals [7]. Common strategies include:

- Default Selection: Choosing orbitals and electrons around the Fermi level matching the specified (n,m) numbers [6].

- Manual Selection: Specifying molecular orbital indices based on chemical intuition and visualization [6].

- Automated Schemes: Using algorithms like AVAS or DMET_CAS that select active spaces based on atomic orbital targets [6].

Table 2: Common Active Space Strategies for Different System Types

| System Type | Recommended Active Space | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Diradical | CAS(2,2) in π system | Include nearly degenerate frontier orbitals |

| Transition Metal Complex | Metal d-orbitals and key ligand orbitals | Metal oxidation state determines electron count |

| Bond Breaking | CAS(2,2) for one bond | Include bonding and antibonding orbital pair |

Incorporating Dynamic Correlation via Perturbation Theory

While CASSCF captures static correlation, it lacks dynamic correlation. This is addressed by multireference perturbation theory methods that use the CASSCF wavefunction as a reference:

- N-Electron Valence State Perturbation Theory (NEVPT): Uses the Dyall Hamiltonian, which partially incorporates two-body terms, as its zeroth-order Hamiltonian [8] [9]. This approach is size-consistent and generally free from intruder state problems [9].

- Complete Active Space Perturbation Theory (CASPT2): Employs a one-body zeroth-order Hamiltonian [9].

Recent developments include partial fourth-order NEVPT (NEVPT4(SD)), which offers improved accuracy over second-order methods for challenging systems like transition metal multiplets and bond dissociation curves [9].

Quantum Embedding for Large Systems

The steep scaling of multireference methods prohibits their application to large molecules and materials. Quantum embedding methods address this by partitioning the system into a small, strongly correlated fragment treated with high-level multireference methods, and a larger environment treated with more affordable methods [7].

Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) is one prominent approach that begins with a converged mean-field wavefunction, localizes the orbitals, and then embeds a fragment in a bath constructed from the environment [7]. This allows the application of multireference methods like CASSCF to the embedded fragment, capturing local static correlation effects at a feasible computational cost [7].

Practical Protocols and Applications

Example Protocol: CASSCF/NEVPT2 Calculation for Bond Dissociation

- Initial Calculation: Perform a Hartree-Fock or DFT calculation to obtain initial orbitals.

- Active Space Selection: For a single bond A-B, typically select CAS(2,2) including the bonding (σ) and antibonding (σ*) orbitals.

- Orbital Localization (Optional): Use localization schemes (Pipek-Mezey) to generate chemically intuitive orbitals [7].

- CASSCF Optimization: Run CASSCF calculation to optimize orbitals and CI coefficients simultaneously.

- Dynamic Correlation: Perform NEVPT2 single-point energy calculation on the CASSCF reference wavefunction.

- Property Analysis: Calculate properties of interest (spin densities, population analysis) from the converged wavefunction.

Case Study: Trichromium Extended Metal Atom Chains

Transition metal systems exemplify the challenges of static correlation. A study on trichromium extended metal atom chains (EMACs) revealed that density functional theory failed to locate unsymmetric minima observed experimentally for NO₃⁻-capped systems [10]. In contrast, CASPT2 successfully reproduced the asymmetric Cr–Cr bond lengths, with values of 1.950 Å and 2.640 Å matching experimental trends [10]. This demonstrates the critical importance of properly balancing static and dynamic correlation for accurate prediction of molecular structure in strongly correlated systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Methods for Multireference Calculations

| Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CASSCF | Handles static correlation via active space optimization | Primary method for strongly correlated systems |

| NEVPT2 | Adds dynamic correlation to CASSCF wavefunction | Post-CASSCF energy correction |

| DMET | Embeds high-level method in mean-field environment | Large systems with local correlation |

| AVAS | Automates active space selection | Systems where manual selection is difficult |

| VQE | Quantum algorithm for ground state energy | Potential quantum advantage for active space CI |

Methodological Workflows and Relationships

Future Perspectives: Quantum Computing and Beyond

The integration of quantum embedding methods with quantum algorithms represents a promising future direction. Hybrid approaches using the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) for the subsystem and classical methods for the environment may extend the reach of multireference calculations beyond the limitations of classical computers [7]. Meanwhile, developments in higher-order perturbation theory (e.g., NEVPT4) continue to push the boundaries of accuracy for classical computational methods [9].

Understanding and applying the concept of static correlation through multi-configurational wavefunctions is essential for accurate quantum chemical investigations of bond breaking processes and strongly correlated molecular systems. The CASSCF method provides the foundation for capturing static correlation, while perturbation theories like NEVPT2 incorporate crucial dynamic correlation effects. For complex systems in drug development and materials science, embedding techniques enable the targeted application of these computationally demanding methods. As methodology continues to advance, particularly through integration with quantum computing, the scope and accuracy of multireference calculations for bond breaking research will continue to expand.

In multireference perturbation theory (MRPT) for bond breaking research, the choice of reference wavefunction is critical. The Complete Active Space (CAS) approach provides a robust framework for generating reference wavefunctions that accurately capture the "static correlation" essential for describing bond dissociation processes. This guide details the core components of CAS and its role within MRPT calculations.

# Theoretical Foundation of Complete Active Spaces

In quantum chemistry, a Complete Active Space (CAS) is a classification scheme for molecular orbitals that partitions them into three distinct, continuous, and non-overlapping classes [11] [12]:

- Core (or Inactive) Orbitals: These orbitals are always fully occupied by two electrons each. They typically represent the inner-shell electrons of the atoms and are treated at a mean-field level [11] [13].

- Active Orbitals: These are partially occupied orbitals where a Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) calculation is performed. Electrons are distributed in all possible ways (configurations) within this set of orbitals, allowing the wavefunction to be a linear combination of multiple Slater determinants. This space is designed to capture the static correlation that is dominant in bond breaking, transition metal complexes, and diradicals [11] [13] [12].

- Virtual (or External) Orbitals: These orbitals are always unoccupied in the reference wavefunction and represent higher-energy orbitals [11] [13].

A CAS wavefunction is denoted as CAS(n, m), where n is the number of active electrons and m is the number of active orbitals [12]. The combinatorial growth of the FCI problem within the active space is a primary computational bottleneck. The total number of Slater determinants for a CAS with M spatial orbitals, N↑ up-spin electrons, and N↓ down-spin electrons is given by [13]:

NTotal = [ M! / (N↑! (M - N↑)!) ] * [ M! / (N↓! (M - N↓)!) ]

Table 1: Computational Scaling of Active Spaces

| Active Electrons (n) | Active Orbitals (m) | Approximate Number of Determinants | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | ~4 | Trivial |

| 8 | 8 | ~20 million | Routine |

| 12 | 12 | ~1 billion | Demanding |

| 18 | 18 | ~2 billion | Limit of modern computing [13] |

The primary purpose of a CASSCF (Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field) calculation is to optimize both the molecular orbitals spanning the three spaces and the CI coefficients of the FCI wavefunction simultaneously. This provides an optimal reference wavefunction that incorporates static correlation [13].

# The CASSCF/MRPT Workflow for Bond Breaking

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating a CASSCF reference with MRPT to accurately model a chemical process like bond breaking.

Workflow: CASSCF/MRPT for Bond Breaking

# A Practical Protocol: MRPT Study of the RaCl Molecule

A study on the radium chloride (RaCl) molecule provides a concrete example of applying this methodology to a system relevant for laser cooling and precision spectroscopy [14].

Study Objective

To calculate the potential energy curves (PECs) of the ground and low-lying excited states of RaCl, determine its spectroscopic constants, and evaluate its suitability for direct laser cooling [14].

Computational Methodology

- Multireference Perturbation Theory: The calculations were performed at the CASSCF/XMCQDPT2 (Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field / Extended Multi-Configuration Quasi-Degenerate 2nd Order Perturbation Theory) level, a specific flavor of MRPT [14].

- Spin-Orbit Coupling (SOC): The influence of SOC was included due to the presence of the heavy radium atom, which is critical for accurately predicting the energy levels [14].

- Basis Sets and Effective Core Potentials (ECPs):

Active Space Selection for RaCl

The electronic structure of alkaline earth monohalides like RaCl is largely ionic (Ra⁺Cl⁻). The low-lying excited states arise from exciting the valence electron on Ra⁺. The active space was constructed based on this physical picture [14]:

- Active Orbitals: The molecular orbitals derived from the valence 7s, 7p, and 6d atomic orbitals of radium were included.

- Active Electrons: The single valence electron from Ra⁺ (forming the ionic bond with Cl⁻) was distributed among these active orbitals. This setup allows the MRPT calculation to accurately describe the various electronic states resulting from promotions of this electron within the active space.

Key Parameters for Accuracy

The study highlighted several parameters that must be carefully tuned for high accuracy [14]:

- The number and qualitative composition (Σ, Π, Δ) of the states included in the perturbation treatment.

- The "energy denominator shift" parameter to avoid intruder state problems.

- The effective charge value used in the ECP.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for MRPT

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| CASSCF | Generates the multiconfigurational reference wavefunction by optimizing orbitals and CI coefficients within the active space. |

| XMCQDPT2 | A multi-reference perturbation theory method that recovers dynamic electron correlation based on a CASSCF reference. |

| Effective Core Potential (ECP) | Replaces core electrons for heavy atoms, simplifying the calculation and incorporating relativistic effects. |

| Correlation-Consistent Basis Set | A family of Gaussian-type orbital basis sets designed for systematic convergence towards the complete basis set limit. |

| Active Space (CAS(n, m)) | The heart of the method, defining the orbitals and electrons where electron correlation is treated exactly. |

# Advanced Developments: Analytical Gradients in MRPT

For MRPT methods to be widely applicable in exploring potential energy surfaces (e.g., for geometry optimization or molecular dynamics), efficient computation of analytical nuclear gradients (energy first derivatives) is essential. Recent theoretical advances have made this possible for various MRPT methods [15]. The development of analytical gradient and derivative coupling theories allows researchers to perform:

- Efficient geometry optimizations for molecules with strong static correlation.

- Nonadiabatic dynamics simulations, which are crucial for studying photochemical processes where bond breaking occurs [15]. These developments bridge the gap between obtaining accurate single-point energies for a fixed molecular geometry and performing practical computations on molecular structures and dynamics in bond breaking research.

The accurate computational description of quantum mechanical systems, particularly in chemistry and physics, requires sophisticated treatment of electron correlation. This challenge becomes particularly acute in systems with near-degeneracies, such as those encountered in bond-breaking reactions, excited states, and open-shell systems containing transition metals or actinides. Single-reference methods, including standard coupled-cluster and perturbation theory approaches, often fail for these systems because they assume a single dominant electronic configuration. Multireference methods address this limitation by considering multiple configurations simultaneously. Among the most powerful strategies are those that bridge two foundational pillars of quantum chemistry: Configuration Interaction (CI), which provides a systematic variational framework for capturing static correlation, and Perturbation Theory (PT), which efficiently recovers dynamic correlation. This technical guide examines the theoretical underpinnings, modern implementations, and practical applications of methods that unite these approaches to tackle the bond-breaking problem and other strongly correlated phenomena.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Frameworks

The Core Hybrid Approach: CI+PT

The combination of Configuration Interaction and Perturbation Theory aims to leverage the respective strengths of each method. CI, particularly in its multireference forms (MRCI), provides a robust treatment of static correlation (or near-degeneracy effects) by diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in a selected space of configuration state functions (CSFs). However, its computational cost scales steeply, and it is not size-consistent. Perturbation Theory, on the other hand, offers an efficient, size-consistent framework for capturing dynamic correlation, which arises from the instantaneous Coulombic repulsion between electrons.

The hybrid CI+PT approach typically follows a two-step procedure:

- A reference wavefunction is first obtained via a multireference CI calculation within an active space of orbitals (e.g., CASSCF). This wavefunction, often comprising multiple electronic states, accounts for static correlation.

- The effect of excitations outside this active space (the "external" space) is then incorporated using Rayleigh-Schrödinger Perturbation Theory. This step accounts for dynamic correlation, dramatically improving accuracy without the prohibitive cost of a full CI.

This paradigm is instantiated in methods like CI+MBPT (Configuration Interaction plus Many-Body Perturbation Theory), which has proven highly successful in atomic physics and quantum chemistry for systems with complex electronic structures [16] [17]. The primary challenge lies in the formulation of the effective Hamiltonian for the perturbation step, ensuring balanced treatment of the various reference states and avoiding intruder state problems.

Quantum Computing and Error Mitigation with MREM

The advent of quantum computing introduces new dimensions to these classical methods. On Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading algorithm for quantum chemistry simulations. However, its results are susceptible to hardware noise. Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM) is a cost-effective technique that calibrates out noise by using a classically solvable reference state (like Hartree-Fock) to estimate the hardware error [18].

For strongly correlated systems where a single-determinant reference is inadequate, this approach has been extended to Multireference-state Error Mitigation (MREM). MREM utilizes a multireference state—a linear combination of Slater determinants engineered to have substantial overlap with the true ground state [18]. These states are prepared on quantum hardware using techniques like Givens rotations, which preserve physical symmetries. By quantifying and mitigating noise on this more physically relevant reference state, MREM significantly improves the accuracy of VQE calculations for molecules like N₂ and F₂ in bond-stretching regions, effectively bridging the concepts of multireference theory and error correction for quantum computation [18].

Embedding and Fragmentation for Complex Systems

To apply multireference methods to large molecules and extended materials, embedding and fragmentation strategies are essential. Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) and related approaches partition a system into a strongly correlated fragment and a mean-field environment [7]. A high-level multireference method (e.g., CASSCF) is applied to the fragment, while the environment is treated with a lower-level method (e.g., Hartree-Fock). The fragment and environment are coupled self-consistently via a one-body embedding potential. This allows for the application of accurate CI+PT solvers to the specific region of interest, making realistic applications to catalysis and materials science feasible [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Methods Bridging CI and PT

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Primary Application Domain | Key Advantage | Notable Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI+MBPT [16] [17] | Perturbative correction to a multireference CI wavefunction. | Atomic spectra (e.g., Pu II), molecular bond breaking. | High accuracy for systems with many valence electrons. | Accuracy depends on the choice of active space; intruder state problems. |

| MREM [18] | Error mitigation using a multireference state on a quantum computer. | Strongly correlated molecules on NISQ devices. | Mitigates quantum hardware noise without exponential overhead. | Requires classical generation of a compact multireference state. |

| DMET [7] | Embedding a high-level fragment in a low-level environment. | Transition metal complexes, extended materials. | Applies high-level methods to large systems via fragmentation. | Double-counting of correlation can be an issue; self-consistent convergence. |

| NEVPT2 [19] | Internally contracted perturbation theory on a CASSCF reference. | General quantum chemistry for strongly correlated systems. | Size-consistent and avoids intruder states; often the recommended choice. | More complex formalism than traditional, uncontracted approaches. |

Computational Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Traditional MR-PT for Molecular Bond Breaking

This protocol outlines the steps for performing a multireference perturbation theory calculation to map a bond dissociation potential energy surface, a classic example of the bond-breaking problem where single-reference methods like CCSD(T) fail.

System Preparation and Active Space Selection:

- Molecular Geometry: Define the initial molecular geometry at equilibrium. The calculation will be repeated along the reaction coordinate of the stretching bond.

- Active Space Selection: This is the most critical step. For a single bond A-B, a minimal active space is CAS(2,2), comprising the bonding (σ) and antibonding (σ*) orbitals and two electrons. For higher accuracy, especially with participating lone pairs or additional bonds, a larger active space like CAS(n,m) must be carefully chosen based on chemical intuition and preliminary calculations [20] [19].

Reference Wavefunction Calculation:

- Method: Perform a CASSCF calculation.

- Objective: Optimize both the CI coefficients (wavefunction) and the orbital shapes for the selected active space. This provides the multireference wavefunction that correctly describes the static correlation upon bond dissociation.

Dynamic Correlation with Perturbation Theory:

- Method: Apply a second-order perturbation theory method on top of the CASSCF reference. The N-Electron Valence Perturbation Theory (NEVPT2) is highly recommended for its size-consistency and robustness [19]. Alternatively, the CASPT2 method can be used.

- Input: The orbitals and reference wavefunction from the CASSCF calculation.

- Output: The final, corrected energy that includes both static and dynamic correlation effects.

Potential Energy Surface Mapping:

- Procedure: Repeat steps 1-3 for a series of fixed bond lengths for A-B to map the dissociation curve. The result will be a smooth, quantitatively accurate curve from equilibrium to the dissociation limit.

Protocol 2: CI+MBPT for Atomic Spectra

This protocol is tailored for calculating energy levels and properties of complex atoms and ions, such as actinides, with high spectral accuracy [17].

Relativistic Treatment and Basis Sets:

- Method: Employ relativistic Hamiltonian (e.g., Dirac-Coulomb) or relativistic pseudopotentials (effective core potentials) to account for relativistic effects, which are crucial for heavy elements.

- Basis Sets: Use specialized, correlating basis sets designed for actinide or lanthanide atoms [17].

Configuration Interaction with Valence Electrons:

- Approach: Perform a large-scale CI calculation considering only the valence electrons (e.g., 7 for Pu II), while the core electrons are frozen.

- Goal: Generate a set of low-energy eigenstates that form the reference for subsequent perturbation theory.

Many-Body Perturbation Theory Correction:

- Method: Apply MBPT to account for the core-valence and core-core correlations. This step calculates an effective Hamiltonian for the valence electrons that incorporates the screening and polarization effects of the frozen core.

- Implementation: As detailed in [16], this "CI+MBPT" approach combines the complex valence CI with an ab initio account of core correlation, enabling accurate predictions for levels that can be matched to experimental spectra.

Workflow Visualization: CI+PT Integration

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow common to many methods that bridge Configuration Interaction and Perturbation Theory.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The computational study of bond breaking and strong correlation requires a suite of "research reagents" – software tools, basis sets, and active spaces. The table below details key resources for conducting reliable simulations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for Multireference Calculations

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS(n, m) Active Space | Methodological Core | Defines the orbital space for static correlation treatment. | CAS(2,2) for single bond dissociation; larger spaces (e.g., CAS(12,12) for Fe-S clusters) for complex metals [20] [19]. |

| NEVPT2 Module | Software Algorithm | Adds dynamic correlation to a CASSCF reference; size-consistent. | Preferred over uncontracted MR-PT in packages like ORCA for its robustness and performance [19]. |

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Quantum Algorithm | Prepares multireference states on quantum hardware for MREM. | Preserves particle number and spin; used for error mitigation in VQE [18]. |

| Correlating Basis Sets | Basis Function Set | Provides flexibility for electrons to correlate motion. | e.g., cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ for molecules; specialized ANO/relativistic sets for heavy atoms [17]. |

| Density Matrix Embedding (DMET) | Embedding Framework | Enables high-accuracy calculation on a fragment of a large system. | Crucial for applying multireference methods to biological systems or materials [7]. |

The strategic integration of Configuration Interaction and Perturbation Theory represents a cornerstone of modern computational science for tackling strong electron correlation. From the highly accurate CI+MBPT method for atomic spectra to the robust NEVPT2 for molecular bond breaking, and the innovative MREM for quantum hardware, this hybrid paradigm demonstrates both maturity and adaptability. As computational challenges move towards larger and more complex systems in drug discovery and materials science, the continued evolution of these methods—particularly through embedding techniques and quantum hybrid algorithms—will be essential for achieving predictive accuracy in the description of chemical bonding and reactivity.

A Practical Guide to Key MRPT Methods: CASPT2, NEVPT2, and Beyond

Multireference Perturbation Theory (MRPT) provides a robust framework for accurately describing the electronic structure of molecular systems where single-reference methods, such as standard density functional theory (DFT) or coupled-cluster theory, are inadequate. This challenge is particularly prevalent in the study of bond-breaking processes, transition metal complexes, open-shell systems, and excited states, where strong electron correlation and near-degeneracy effects dominate. These scenarios require a multiconfigurational treatment to correctly capture the static correlation, upon which dynamical correlation can be built. Among the various MRPT approaches, the Complete Active Space Perturbation Theory, second-order (CASPT2) and the N-Electron Valence State Perturbation Theory, second-order (NEVPT2) have emerged as the dominant "workhorse" methods for computational chemists, each with distinct theoretical foundations and performance characteristics [7]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these two core methodologies, detailing their theoretical underpinnings, practical implementation, performance benchmarks, and protocols for their application in challenging research areas such as bond dissociation energetics.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Structures

The CASPT2 Methodology

CASPT2 builds upon a Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) reference wavefunction, which provides a qualitatively correct description of static correlation within a user-defined active space of electrons and orbitals. The CASSCF wavefunction serves as the zeroth-order approximation in Rayleigh-Schrödinger perturbation theory. The first-order wavefunction is expanded in a basis of internally contracted configuration state functions, which are generated by applying excitation operators to the complete multiconfigurational reference. This internal contraction significantly reduces the computational cost by utilizing the full symmetry of the reference wavefunction.

A critical aspect of conventional CASPT2 is its vulnerability to the "intruder state" problem, where the presence of near-singularities in the denominator of the perturbation expansion leads to erratic behavior and unphysical energies. To mitigate this, an empirical real-valued shift parameter (often denoted as ϵ) is typically applied to the Hamiltonian's diagonal elements. Furthermore, the widely-used Ionization Potential-Electron Affinity (IPEA) shift introduces an additional empirical correction to improve the balance between states of different character, particularly for organic molecules and excited states [21]. While these shifts enhance stability and accuracy, they also introduce a degree of parameter dependence that requires careful validation.

The NEVPT2 Methodology

NEVPT2 represents an alternative perturbative approach that addresses several theoretical shortcomings of CASPT2. Its fundamental distinction lies in the use of the Dyall Hamiltonian as the zeroth-order operator [22] [23]. The Dyall Hamiltonian effectively separates the active electron system from the inactive (core and virtual) spaces, providing a more physically justified partitioning that inherently includes the effect of the active space on the dynamic correlation energy.

This theoretical foundation grants NEVPT2 several advantageous properties:

- Intruder-State Free: The structure of the Dyall Hamiltonian naturally avoids the singularities that plague CASPT2, eliminating the need for empirical real or imaginary shift parameters [22] [23].

- Strict Size-Consistency: The method is strictly size-consistent, ensuring that the total energy of non-interacting fragments equals the sum of their individual energies [22].

- Internal Contraction: NEVPT2 is implemented in an internally contracted formalism, preserving the spatial and spin symmetry of the reference wavefunction.

NEVPT2 exists in two primary variants [24] [22] [23]:

- Strongly-Contracted (SC-NEVPT2): In this approach, each excitation class (e.g., V0ijab, V1i) is represented by a single perturber function. This creates a very compact perturber space with orthogonal subspaces, leading to high computational efficiency.

- Partially-Contracted (PC-NEVPT2/FIC-NEVPT2): Also termed Fully Internally Contracted (FIC-NEVPT2) in some implementations, this variant employs a more complete basis of perturber functions within each excitation class. While computationally more demanding, it typically provides slightly more accurate results, particularly for systems with complex electronic structures [21].

Table 1: Core Theoretical Differences Between CASPT2 and NEVPT2

| Feature | CASPT2 | NEVPT2 |

|---|---|---|

| Zeroth-Order Hamiltonian | Møller-Plesset-type (Fock operator) | Dyall Hamiltonian |

| Intruder State Handling | Requires empirical (real/imaginary) shifts | Intrinsically avoided; no shifts needed |

| Size-Consistency | Formal size-consistency can be affected by approximations | Strictly size-consistent |

| Contraction Scheme | Internally contracted | Strongly- or Partially-Contracted |

| IPEA Shift | Often required for quantitative accuracy | Not applicable |

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow common to both methods, highlighting the shared initial steps and the point of theoretical divergence.

Performance Benchmarking and Accuracy Assessment

Spin-State Energetics in Transition Metal Complexes

Quantitative accuracy in predicting spin-state energy splittings is a rigorous test for quantum chemical methods, especially for iron-containing complexes relevant in catalysis and biochemistry. A benchmark study comparing multiple methods against experimental data for octahedral iron complexes revealed critical performance differences [25].

Table 2: Performance of Quantum Chemistry Methods for Spin-State Energetics of Iron Complexes (Mean Absolute Error in kcal mol⁻¹) [25]

| Method | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | < 1.0 | Gold-standard accuracy, particularly with Kohn-Sham orbitals. |

| CASPT2 | ~5.5 | Systematic overstabilization of higher-spin states. |

| CASPT2/CC | Improved | Partially remedies CASPT2's systematic error. |

| NEVPT2 | Up to 7.0 | Worse than CASPT2 for these systems. |

| MRCISD+Q | < 3.0 (Davidson-Silver/Pople) | Accuracy highly dependent on size-consistency correction. |

| B2PLYP-D3/OPBE (DFT) | Variable | Few DFT functionals provided balanced description for all complexes. |

The study concluded that CCSD(T) delivered exceptional accuracy, while both CASPT2 and NEVPT2 exhibited significant deviations. CASPT2 consistently overstabilized higher-spin states, while NEVPT2 performed even less accurately in this specific domain [25]. This highlights the context-dependent performance of these methods and underscores the necessity of method validation for specific chemical applications.

The accuracy of CASPT2 and NEVPT2 has been extensively evaluated for vertical excitation energies. A large-scale benchmarking on the QUESTDB database, which contains 542 vertical excitation energies for small and midsize organic molecules, provides statistically robust performance metrics [21] [26].

For a diverse set of 284 excited states (including singlets, triplets, valence, Rydberg, n→π, π→π, and double excitations), the following performance was observed [21]:

- PC-NEVPT2 achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.13 eV.

- CASPT2 with IPEA shift achieved a similar MAE of 0.11 eV.

- Both methods demonstrated relatively uniform performance across different transition subgroups (valence, Rydberg, etc.).

- The accuracy of NEVPT2 was found to be more sensitive to the size of the basis set used to converge the underlying wavefunction compared to multi-configuration pair-density functional theory (MC-PDFT) alternatives [26].

This demonstrates that when properly configured (i.e., CASPT2 with an IPEA shift), both methods can deliver highly reliable vertical excitation energies for main-group organic molecules, performing on par with single-reference methods like ADC(2) and CCSD for singly-excited states [21].

Practical Protocols and Implementation

General Workflow and Active Space Selection

The successful application of either CASPT2 or NEVPT2 hinges on a properly converged CASSCF reference wavefunction. The most critical and often challenging step is the selection of an appropriate active space, denoted as CAS(n, m), where 'n' is the number of active electrons and 'm' is the number of active orbitals.

Protocol for Active Space Selection:

- Chemical Intuition: For well-localized systems (e.g., the bonding region in a bond-breaking study, d-orbitals in a transition metal complex, or the π-system in an organic chromophore), the active space can be selected based on chemical knowledge. For example, simulating the nitrogen vacancy (NV⁻) center in diamond utilizes a CAS(6,4) space comprising the four defect-localized orbitals arising from the dangling bonds of the atoms adjacent to the vacancy [27].

- Automated Selection: For complex systems, automated active space selection algorithms are recommended to reduce human bias. The Approximate Pair Coefficient (APC) scheme is one such method, which ranks localized orbitals by their approximated orbital entropies and selects the most correlated ones to form an active space up to a predefined limit on the number of configuration state functions [26].

- Convergence Testing: The sensitivity of the final results (e.g., reaction energies, excitation energies) to the size of the active space should be tested systematically, for example, by increasing the number of orbitals and electrons in the active space until the property of interest converges.

Detailed NEVPT2 Calculation Protocol

The following protocol, based on the implementation in the OpenMolcas and ORCA software packages, outlines the steps for a typical NEVPT2 calculation [24] [22].

A. Reference Wavefunction Generation with DMRG-SCF

For larger active spaces, a Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) solver may be used instead of a conventional full configuration interaction (FCI) solver.

B. Integral Transformation with MOTRA

The two-electron integrals must be transformed into the molecular orbital basis obtained from the DMRG-SCF calculation.

- The

MOTRAmodule performs this transformation. - Key keywords include

HDF5(for output format),CTOnlyandKpq(if using Cholesky decomposition), andFrozen=0(if Cholesky is used with frozen orbitals) [24]. - Cholesky decomposition is strongly recommended for performance.

C. Distributed 4-RDM Evaluation (For Large Active Spaces)

The evaluation of the 4-particle reduced density matrix (4-RDM) scales as N⁸ with the number of active orbitals. For active spaces larger than 12 orbitals, a distributed computation is necessary [24].

- Run the

prepare_rdm_template.shscript in the OpenMolcas scratch directory to create subdirectories for each electronic state. - Use the (experimental)

jobmanager.pyPython utility to split the 4-RDM calculation into four-index subblocks and submit them as separate batch jobs. - Once all jobs complete, the subblocks are merged into the full matrix.

D. Final NEVPT2 Energy Computation

The NEVPT2 module is called to compute the final energy correction. The DISTributedRDM keyword must be used to point to the directories containing the distributed 4-RDM data [24].

In the ORCA software suite, the process is more streamlined. The NEVPT2 calculation is initiated by adding a single keyword (!SC-NEVPT2, !FIC-NEVPT2, or !DLPNO-NEVPT2) to a working CASSCF input. The calculation can be run in a single step or split into separate CASSCF and NEVPT2 steps for better control [22] [23]. For very large systems, the DLPNO-NEVPT2 method is recommended, which recovers 99.9% of the FIC-NEVPT2 correlation energy with significantly reduced computational cost [22] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Protocols for MRPT Calculations

| Tool / Protocol | Function / Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Active Space Selector | Identifies the most correlated orbitals to define the CAS. | APC (Approximate Pair Coefficient) scheme [26], DMRG-SCF [24] |

| 4-RDM Evaluator | Computes the 4-particle reduced density matrix, required for NEVPT2. | Distributed evaluation with jobmanager.py [24] |

| Perturbation Theory Solver | Computes the second-order energy correction. | SC-NEVPT2, PC/FIC-NEVPT2, CASPT2 modules in OpenMolcas, ORCA [24] [22] |

| Integral Transformer | Transforms two-electron integrals to the MO basis. | MOTRA module in OpenMolcas [24] |

| Localization Scheme | Generates localized orbitals for automated active space selection. | Boys localization [26] |

| DLPNO Approximation | Dramatically reduces computational cost for large molecules. | DLPNO-NEVPT2 in ORCA [22] [23] |

Applications in Bond Breaking and Strong Correlation

The primary strength of CASPT2 and NEVPT2 lies in their ability to handle systems with strong multireference character. This is exquisitely demonstrated in the calculation of potential energy surfaces for bond breaking. As a bond stretches, the electronic wavefunction transitions from a single-reference character near the equilibrium geometry to a multiconfigurational character at dissociation. Single-reference methods like MP2 or CCSD fail dramatically in this regime, while MRPT methods provide a qualitatively and quantitatively correct description. For example, tracking the energy of the N₂ molecule along the dissociation coordinate is a standard test, which both CASPT2 and NEVPT2 can handle successfully [22].

Beyond bond breaking, these methods are indispensable for [27] [7]:

- Excited State Chemistry: Accurate modeling of photochemical reactions and excitation spectra, particularly for states with double-excitation character or charge-transfer nature.

- Transition Metal Complexes: Modeling spin-state energetics, reaction mechanisms in catalysis, and spectroscopic properties of metal-containing systems.

- Point Defects in Solids: Calculating the accurate energetics of in-gap states in solid-state color centers (e.g., the NV⁻ center in diamond), which often exhibit strong multideterminant character [27].

- Molecular Magnetism: Studying the electronic structure and magnetic interactions in polynuclear transition metal complexes and single-molecule magnets.

CASPT2 and NEVPT2 stand as the two cornerstone methods of modern multireference perturbation theory. While NEVPT2 offers a more robust theoretical foundation by being intruder-state free and not requiring empirical shifts, CASPT2 (with the IPEA shift) often delivers comparable, and in some cases superior, quantitative accuracy for specific properties like excitation energies and spin-state splittings. The choice between them is not absolute and must be guided by the specific chemical problem, the system under investigation, and the need for methodological purity versus benchmarked performance. Future developments are likely to focus on increasing the scalability of these methods through advanced approximations like DLPNO, their integration with quantum embedding schemes (e.g., Density Matrix Embedding Theory) [7], and their adaptation for emerging quantum computing algorithms, thereby expanding their applicability to larger and more complex molecular systems in drug development and materials science.

The accurate description of electron correlation is a central challenge in quantum chemistry, particularly for processes like bond breaking and reactions involving open-shell transition metal complexes. In these scenarios, the electronic wavefunction becomes multiconfigurational, meaning it cannot be accurately described by a single Slater determinant. Correlated wave function methods are broadly divided into single-reference and multi-reference approaches, with the latter being essential for systems with strong electron correlation [28].

Multireference perturbation theories, such as Complete Active Space Second-Order Perturbation Theory (CASPT2), are pivotal for recovering missing dynamical electron correlation from multiconfigurational zeroth-order wavefunctions [29]. These methods combine a multiconfigurational reference with perturbative treatment of dynamic correlation. However, a critical methodological choice arises: whether to apply the perturbation theory to each electronic state individually (State-Specific, SS) or to a manifold of states simultaneously (Multi-State, MS). This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these approaches within the context of bond-breaking research, offering protocols and data to inform researchers' computational strategies.

Theoretical Foundations: SS and MS Formulations

The Multireference Starting Point

Multireference methods address static electron correlation by constructing wavefunctions as linear combinations of multiple electronic configurations, optimizing both the many-body expansion coefficients and the molecular orbitals simultaneously [28]. The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) method is a widely successful approach for this, providing a qualitatively correct wavefunction [30].

However, CASSCF often fails to capture all dynamic electron correlation. To regain quantitative accuracy, post-SCF approaches are employed. Among these, CASPT2 is a benchmark method, while Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT) offers a computationally efficient alternative that computes the energy using a functional form inspired by Kohn-Sham DFT [30].

State-Specific (SS) Formulation

In the SS approach, perturbation theory is applied separately to each electronic state. The dynamical correlation is captured for one state at a time, based on its own reference wavefunction. The data-driven CASPT2 (DDCASPT2) method, for example, is a machine learning-based alternative that captures dynamical electron correlation with near-CASPT2 quality in a state-specific manner [29].

- Key Advantage: The description is tailored to a single state, which can be advantageous for states that are well-separated in energy.

- Key Limitation: The process can lead to an inconsistent treatment of different states, particularly when they exhibit strong mixing or lie close in energy.

Multi-State (MS) Formulation

The MS approach, such as multi-state CASPT2 (MS-CASPT2) or quasi-degenerate extensions, applies perturbation theory to a manifold of states simultaneously. It combines MC reference states with a perturbative treatment of the dynamic correlation and effective Hamiltonian theory [28]. This provides a coupled treatment of the states, ensuring a balanced description.

- Key Advantage: It provides a balanced treatment of mixed electronic states, which is crucial for describing conical intersections, avoided crossings, and systems with near-degenerate electronic states [28].

- Key Limitation: It is computationally more demanding than the SS approach and can be overkill for systems where states are not interacting strongly.

The following workflow outlines the critical decision points when choosing between SS and MS approaches for a typical research project investigating mixed electronic states.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for choosing between SS and MS approaches.

Quantitative Comparison: Accuracy and Performance

The choice between SS and MS formulations has direct implications for computational accuracy and resource requirements. The following table summarizes key performance metrics based on recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of SS and MS Formulations in Representative Studies

| Method | System Studied | Key Performance Metric | Result | Protocol Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Driven CASPT2 (SS) [29] | Diverse small molecules | Accuracy vs traditional CASPT2 | Near-CASPT2 quality | Machine learning can reduce cost while maintaining SS accuracy. |

| MC-PDFT (inherently SS) [30] | TiC+-catalyzed CH4 activation | Reaction barrier height | Superior to KS-DFT for multireference reaction | SS methods reliable for ground-state reaction barriers. |

| Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM) [18] | H2O, N2, F2 bond stretching | Error mitigation effectiveness | MREM outperforms single-reference REM for strong correlation | Multi-configurational treatments essential for bond dissociation. |

Beyond absolute accuracy, the consistency of the active space is a critical factor for both SS and MS methods, especially when generating data for machine learning interatomic potentials (MLPs). The Weighted Active Space Protocol (WASP) was introduced to systematically assign consistent active spaces across uncorrelated nuclear configurations, which is a prerequisite for obtaining continuous potential energy surfaces with either SS or MS approaches [30].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Consistent Active Space Selection with WASP

A major challenge in any multireference calculation is ensuring a consistent active space across different molecular geometries. The WASP protocol enables the training of MLPs on multireference data.

- Objective: To assign a consistent active space for a given system across uncorrelated nuclear configurations, enabling stable energies and gradients for MLP training [30].

- Procedure:

- Initialization: For a set of initial geometries, perform a reference CASSCF calculation with a well-defined active space (e.g., 7 electrons in 9 orbitals for TiC+ systems).

- Orbital Analysis: For each new geometry, analyze the orbitals (e.g., using atomic valence rules or orbital entanglement metrics) to define a candidate active space.

- Consistency Check: Ensure the candidate active space is adiabatically connected to the reference by comparing orbital characters and occupation numbers.

- Wavefunction Convergence: Use the consistent active space to converge the CASSCF wavefunction, avoiding local minima by using the previous geometry's orbitals as an initial guess.

- Applications: Essential for dynamics simulations and for constructing MLPs for catalytic systems like TiC+-catalyzed methane C-H activation [30].

Protocol 2: Data-Driven CASPT2 for Dynamical Correlation

The DDCASPT2 framework provides a machine-learning pathway to capture dynamical correlation, which can be applied in either an SS or MS context.

- Objective: To capture dynamical electron correlation using features from lower-level electronic structure methods (HF, CASSCF) with near-CASPT2 accuracy [29].

- Procedure:

- Feature Generation: For a small, diverse set of molecules, generate physics-based features from HF and CASSCF calculations. Features can include system size, basis set size, and information on two-electron excitations.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., neural network) to predict the correlation energy from the generated features, using high-level CASPT2 data as the target.

- Feature Analysis: Use SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) analysis to interpret the contribution of each feature to the model's prediction.

- Deployment: Apply the trained model to new systems to predict the correlation energy at a fraction of the computational cost of a full CASPT2 calculation.

- Applications: Offers a rapid alternative to traditional CASPT2 for high-throughput screening or when integrated into dynamics simulations [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Multireference Perturbation Studies

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CASSCF Solver | Generates multiconfigurational reference wavefunction by optimizing orbitals and configuration coefficients. | Provides zeroth-order wavefunction for subsequent CASPT2 or MC-PDFT calculations. |

| Active Space Orbitals | A set of molecular orbitals and electrons treated with full configuration interaction; defines the static correlation. | Selecting (7e,9o) active space for TiC+ to describe catalytic C-H activation [30]. |

| Perturbative Method (CASPT2/NEVPT2) | Recovers dynamic electron correlation missing from CASSCF. | Calculating accurate reaction barriers and excitation energies. |

| On-Top Functional (for MC-PDFT) | Density functional that uses the on-top pair density to compute correlation energy. | Key ingredient in MC-PDFT for computational efficiency comparable to KS-DFT [30]. |

| Quantum Embedding Scheme (e.g., DMET) | Partitions a large system into smaller, manageable fragments for high-accuracy treatment. | Enabling multireference calculations on extended systems like molecules on surfaces [7]. |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Integration with Quantum Computing

Quantum computing presents a promising avenue for overcoming the exponential scaling of classical multireference methods. Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) has been developed as an extension of reference-state error mitigation (REM) for quantum hardware. It uses compact multireference states, prepared via Givens rotations, to effectively mitigate errors in the calculation of strongly correlated ground states on noisy quantum devices [18]. This is particularly relevant for the bond-breaking regions where single-reference REM fails.

Quantum Embedding for Complex Systems

To apply multireference methods to large molecules and extended materials, quantum embedding strategies like Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) are being advanced. These methods partition a system into a fragment, treated with a high-level multireference method, and an environment, treated with a lower-level method [7]. This allows for the accurate description of strong correlation localized to a specific region, such as an active site in a catalyst, making SS and MS studies of biologically relevant systems more feasible.

The logical relationships between traditional methods and these emerging frontiers can be visualized as an integrated research ecosystem.

Diagram 2: The research ecosystem connecting core problems with emerging solutions.

The choice between state-specific and multi-state formulations is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the specific electronic structure of the system under investigation.

Use State-Specific (SS) approaches when studying a single, well-isolated electronic state (e.g., the ground state away from degeneracies), for computing properties like ground-state reaction barriers, or when computational efficiency is a primary concern. SS methods like MC-PDFT and DDCASPT2 have proven highly effective in these contexts [29] [30].

Use Multi-State (MS) approaches when the system involves near-degenerate electronic states, such as when modeling photochemical processes, conical intersections, or systems with significant state mixing. The simultaneous treatment of states in MS-CASPT2 is crucial for obtaining a balanced and accurate description of potential energy surfaces in these regions [28].

As computational methods evolve, the integration of machine learning, quantum embedding, and error-mitigated quantum computing will continue to expand the boundaries of both SS and MS methods, making them more applicable and accurate for the complex systems encountered in drug development and materials science.

A fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry is the accurate and efficient description of bond dissociation processes in chemical reactions. Traditional quantum chemical methods, particularly those based on a single reference determinant such as standard coupled-cluster theory or density functional theory, fail dramatically when chemical bonds break because multiple electronic configurations become near-degenerate in energy [20]. This bond-breaking problem necessitates more sophisticated approaches that can handle this strong electron correlation.

Multireference methods address this challenge by simultaneously considering multiple electronic configurations. This technical guide focuses on three advanced frameworks for treating multireference problems: JM-MRPT2 (Jeziorski-Monkhorst Multireference Perturbation Theory, of which DSRG-MRPT2 is a modern implementation), SS-MRCC (State-Specific Multireference Coupled Cluster), and Spin-Flip methods. These approaches represent the cutting edge in quantum chemistry for modeling chemical reactions, excited states, and complex electronic structures found in transition metal complexes and diradicals, with implications for accurate drug design and materials development.

Theoretical Foundations

The Bond Breaking Problem

When a chemical bond breaks, the electronic wavefunction undergoes a fundamental transformation. Consider the dissociation of the H₂ molecule into two hydrogen atoms. The Hartree-Fock (HF) method places both electrons in the same σ bonding orbital, which is delocalized over both atoms. At large separation, this single-determinant wavefunction contains unphysical ionic terms (H⁻ + H⁺), dramatically increasing the energy and providing a qualitatively wrong description [20]. This failure stems from the restricted HF framework which forces electrons to be paired in the same molecular orbital.

Multiconfigurational approaches resolve this issue by using a wavefunction that is a linear combination of multiple determinants. The Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) method provides the conceptual foundation, where electrons are distributed in a carefully selected active space of orbitals. However, CASSCF only recovers static correlation (essential for qualitative correctness at dissociation) but misses dynamical correlation effects crucial for quantitative accuracy [20].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Advanced Multireference Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Key Strength | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| JM-MRPT2 | Jeziorski-Monkhorst ansatz + perturbation theory | Size-extensivity, systematic improvability | Dependence on active space selection |

| SS-MRCC | State-specific coupled cluster expansion | High accuracy for target state, intensive correlation recovery | Intrusive singularities, computational cost |

| Spin-Flip | High-spin reference + spin-flip excitations | Black-box single-reference formalism, diradical handling | Limited to certain spin states, reference dependence |

Driven Similarity Renormalization Group (DSRG-MRPT2)

The Driven Similarity Renormalization Group implementation of second-order multireference perturbation theory represents a modern evolution of JM-MRPT2 principles.

Theoretical Framework and Implementation

The DSRG-MRPT2 approach avoids the intruder state problems that plague conventional multireference perturbation theories by using a continuous, flow-based transformation of the Hamiltonian that gradually introduces dynamical correlation. A key innovation in modern implementations is the use of factorized two-electron integrals, which avoids storage of large four-index intermediates and significantly reduces computational memory requirements [31].

The method exploits the block structure of reference density matrices to reduce computational cost to that of second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory, enabling applications to larger molecular systems. The DSRG flow equations ensure that the transformation is finite and well-behaved even near degeneracies where traditional theories diverge [31].

Performance and Applications

DSRG-MRPT2 has been benchmarked on challenging systems including ten naphthyne isomers using basis sets up to quintuple-ζ quality. These studies reveal that singlet-triplet splittings (Δ_ST) strongly depend on equilibrium structures, and for consistent geometries, DSRG-MRPT2 predictions show good agreement with those from reduced multireference coupled cluster theory with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples [31].