Navigating Noise: Advanced Strategies for Adjusting Convergence Criteria in Biomedical Optimization

This article addresses the critical challenge of optimizing computational models in the presence of noisy gradients, a pervasive issue in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research.

Navigating Noise: Advanced Strategies for Adjusting Convergence Criteria in Biomedical Optimization

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of optimizing computational models in the presence of noisy gradients, a pervasive issue in pharmaceutical development and biomedical research. We explore the fundamental impact of noise—from finite-shot sampling and model-plant mismatch—on optimization landscapes, transforming smooth convex basins into rugged, complex terrains. The content provides a methodological guide to resilient algorithms, advanced gradient techniques, and robust optimization frameworks tailored for drug substance and process development. Furthermore, we present troubleshooting protocols for parameter tuning and early stopping, alongside a rigorous validation framework for benchmarking optimizer performance in noisy environments. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes cutting-edge strategies to enhance the reliability, efficiency, and regulatory compliance of computational optimization in critical biomedical applications.

The Noise Problem: Understanding How Stochasticity Distorts Optimization Landscapes and Challenges Convergence

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Gradient Issues

Why do my model's gradients vanish or explode when training on noisy biological data?

Gradient issues are common when training models on biomedical datasets, which often have high levels of technical and biological noise [1].

- Problem: Vanishing gradients occur when gradients become exponentially smaller during backpropagation, halting learning in early layers. This happens when the product of weight matrices and activation function derivatives is less than 1 [2].

- Problem: Exploding gradients occur when gradients grow exponentially, causing large parameter updates, loss spikes, and model divergence. This happens when the product of weight matrices and activation function derivatives exceeds 1 [2].

- Solution: Implement gradient norm tracking to monitor L2 norms per layer throughout training. Use experiment trackers like Neptune.ai for real-time monitoring [2].

- Solution: Apply gradient clipping to cap maximum gradient values, preventing explosions [3].

- Solution: Use hybrid dynamical systems that combine known biological terms with neural networks to approximate unknown dynamics, making learning more robust to noise [1].

How can I improve model convergence with noisy single-cell RNA sequencing data?

Single-cell transcriptomics data is inherently sparse and noisy, presenting challenges for differential equation model discovery [1].

- Problem: SINDy (Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics) struggles with realistic biological noise levels and cannot easily incorporate prior knowledge [1].

- Solution: Employ a two-step model discovery framework [1]:

- Fit unknown dynamics using a neural network for smoothing and interpolation

- Use the trained neural network as input to SINDy-like sparse regression

- Solution: Perform model selection at both steps to search hyperparameter space with unbiased evaluation criteria [1].

- Protocol: For single-cell data analysis of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [1]:

- Convert raw data to batch training data using a sliding window

- Train hybrid dynamical models with different hyperparameters

- Use dynamics from the best model for sparse regression

- Evaluate inferred ODE models on fit and extrapolation

What optimizer modifications help with noisy gradient estimation?

Standard optimizers like Adam can suffer from biased gradient estimation and training instability, especially during early stages with noisy data [4].

- Problem: Adam's moment estimates become biased with noisy gradients, causing oscillations and slow convergence [4].

- Solution: Implement BDS-Adam, which integrates adaptive variance rectification with semi-adaptive gradient smoothing [4].

- Solution: Use a dual-path framework with nonlinear gradient mapping and adaptive momentum smoothing [4].

- Solution: Apply adaptive second-order moment correction to mitigate cold-start effects from inaccurate variance estimates [4].

- Experimental Validation: BDS-Adam showed test accuracy improvements of 9.27% on CIFAR-10, 0.08% on MNIST, and 3.00% on a gastric pathology dataset compared to standard Adam [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Biological systems exhibit multiple noise sources that impact computational gradients [1]:

- Technical noise: Measurement errors from sequencing technologies or instrumentation

- Biological intrinsic noise: Stochastic cellular processes

- Biological extrinsic noise: Cell-to-cell variability and environmental fluctuations

What practical techniques can stabilize training with noisy biomedical data?

Several empirically validated techniques can improve stability [2] [3]:

- Gradient Clipping: Caps gradient values to prevent explosion

- Batch Normalization: Reduces internal covariate shift

- Learning Rate Scheduling: Adapts learning rates during training

- Appropriate Activation Functions: Using ReLU instead of sigmoid to mitigate vanishing gradients

- Data Normalization: Ensuring input features are similarly scaled

How do I monitor gradient behavior during training?

Implement layer-wise gradient norm tracking [2]:

Are there domain-specific approaches for biological systems?

Yes, hybrid dynamical systems are particularly effective for biological data [1]:

- Combine partial known biological mechanisms with neural networks

- Use neural networks to approximate unknown system dynamics

- Apply sparse regression to infer interpretable model terms from fitted networks

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Two-Step Model Discovery for Noisy Biological Data

This methodology enables robust model discovery from sparse, noisy biological data [1].

Step 1: Hybrid Dynamical System Training

- Formulate system as:

x′ = g(x) + NN(x)whereg(x)represents known biology andNN(x)approximates unknown dynamics [1] - Generate training batches using sliding window over time series data

- Train neural network component to minimize prediction error

- Use model selection to choose optimal hyperparameters

Step 2: Sparse Regression for Model Inference

- Use trained neural network to estimate derivatives

- Apply SINDy with sequential thresholded least squares (STLSQ)

- Select model using information criteria or cross-validation

- Validate on held-out data and assess extrapolation capability

Experimental Validation: Applied to Lotka-Volterra and repressilator models with realistic noise levels, correctly inferring models despite high noise [1].

Protocol 2: Gradient Stability Assessment and Optimization

Systematic approach to diagnose and address gradient issues [2].

Monitoring Setup:

- Implement layer-wise gradient norm calculation every n steps

- Track norms for key components (attention weights, embeddings, layer outputs)

- Use asynchronous logging to avoid training slowdown

- Visualize gradient flow across network architecture

Intervention Protocol:

- If vanishing gradients detected: Modify activation functions, add batch normalization, adjust initialization

- If exploding gradients detected: Implement gradient clipping, reduce learning rate, adjust optimizer parameters

- Validate interventions by comparing pre/post gradient distributions

Table 1: Optimizer Performance Comparison on Noisy Datasets

| Optimizer | CIFAR-10 Accuracy | MNIST Accuracy | Gastric Pathology Accuracy | Stability Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGD | - | - | - | Medium |

| Adam | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Low |

| AMSGrad | - | - | - | Medium |

| RAdam | - | - | - | High |

| BDS-Adam | +9.27% | +0.08% | +3.00% | High |

Note: Accuracy improvements for BDS-Adam are relative to standard Adam [4]

Table 2: Noise Types in Biological Systems and Their Impact

| Noise Type | Source | Effect on Gradients | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Measurement instruments | Increased variance | Data preprocessing, smoothing |

| Biological intrinsic | Stochastic cellular processes | Biased moment estimates | Hybrid dynamical systems [1] |

| Biological extrinsic | Cell-to-cell variability | Training instability | Adaptive optimizers [4] |

| Computational | Numerical approximation | Exploding/vanishing gradients | Gradient clipping, monitoring [2] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Gradient Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SINDy Algorithm | Sparse nonlinear dynamics identification | Discovering ODE models from data [1] |

| Neptune.ai | Experiment tracking and gradient monitoring | Real-time gradient norm visualization [2] |

| BDS-Adam Optimizer | Adaptive variance rectification | Stabilizing training with noisy gradients [4] |

| Hybrid Dynamical Systems | Combining known and unknown dynamics | Biological system modeling with partial knowledge [1] |

| Phase Gradient Metamaterials | Wavefront manipulation | Acoustic silencing applications [5] |

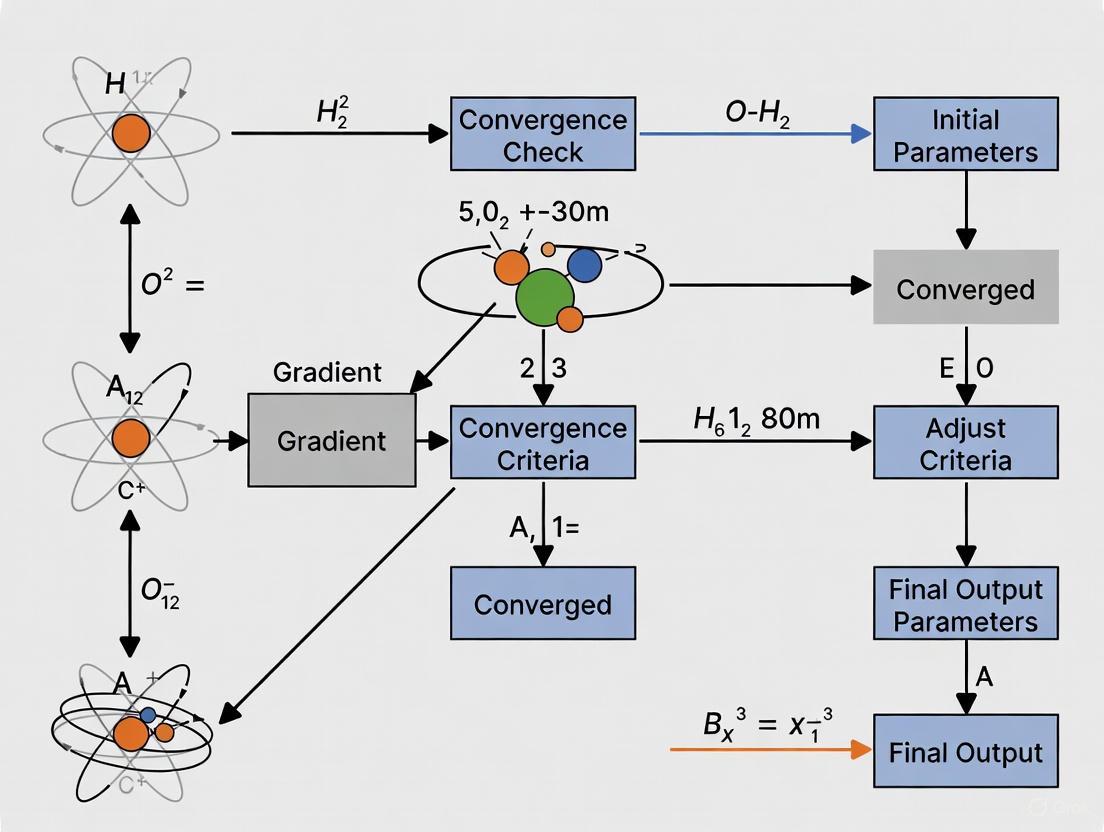

Workflow Visualization

Model Discovery Workflow

Gradient Monitoring System

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why would I intentionally add noise to my gradient descent optimizer? A1: Introducing controlled noise is a strategic method to prevent optimization algorithms from becoming trapped in shallow local minima or saddle points, which are prevalent in complex, non-convex loss landscapes. The noise facilitates exploration of the parameter space, enabling the discovery of wider, flatter minima that often generalize better to unseen data [6]. In the context of noisy computational gradients, this practice can effectively transform a smooth, convex-looking basin into a more navigable, albeit rugged, landscape that reveals deeper minima [7].

Q2: What is the difference between Gaussian and heavy-tailed (Lévy) noise in optimizers? A2: The core difference lies in the structure and behavior of the injected noise, which directly impacts exploration capabilities.

| Noise Type | Distribution Properties | Exploration Behavior | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Noise | Light-tailed; samples are tightly clustered around the mean [6]. | Many small, local steps; limited ability to escape deep, sharp minima. | Stable convergence in relatively smooth regions. |

| Heavy-tailed (Lévy) Noise | Heavy-tailed; allows for rare, large jumps in parameter space [6]. | A mix of local steps and long-range jumps; can efficiently escape sharp minima. | Exploring rugged landscapes and escaping poor local optima. |

Q3: My optimizer with injected noise has become unstable and diverges. What is the likely cause? A3: Divergence is often linked to the Edge of Stability (EoS) phenomenon [7]. Gradient descent dynamics can push the sharpness (the largest eigenvalue of the Hessian) to a stability threshold around ( 2 / \eta ), where ( \eta ) is the learning rate [7]. If this threshold is exceeded, the optimization process can become unstable. This is particularly sensitive when heavy-tailed noise induces a large jump. To mitigate this, consider reducing your learning rate or implementing an adaptive method that modulates the noise based on the current sharpness [6].

Q4: How does the concept of a "multifractal loss landscape" relate to my experiments? A4: A multifractal landscape model captures the complex, multi-scale geometry often found in deep learning and other complex optimization problems. This framework unifies key observed properties like clustered degenerate minima and rich optimization dynamics [7]. If your experiments involve high-dimensional, non-convex problems (e.g., drug discovery via deep learning), your optimizer is likely navigating a multifractal landscape. Understanding this can inform your choice of optimizer, as methods designed for enhanced exploration (e.g., those with heavy-tailed noise) are better suited for such terrains [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Optimizer Trapped in a Suboptimal Local Minimum

- Problem Statement: The optimization process has converged to a solution with an unacceptably high loss value and shows no signs of further improvement, suggesting it is stuck in a local minimum or a saddle point.

- Symptoms & Error Indicators:

- The loss curve plateaus at a high value over many iterations.

- Norm of the gradient approaches zero prematurely.

- The solution demonstrates poor generalization on validation datasets.

- Possible Causes:

- The loss landscape is highly non-convex with many sharp minima.

- The optimizer lacks sufficient exploration capability.

- The learning rate is too small, leading to convergence in the first minimum encountered.

- Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

- Verify the Issue: Confirm that the loss has truly stopped decreasing by running for more iterations and on different random seeds.

- Introduce Isotropic Gaussian Noise: Add Gaussian noise to your gradient updates, as in Stochastic Gradient Langevin Dynamics (SGLD). This can help jiggle the optimizer out of very shallow minima [6]. The update rule is: ( \theta{t+1} = \thetat - \eta \nabla\theta \mathcal{L}(\thetat) + \sqrt{2\eta} \epsilont ) where ( \epsilont \sim \mathcal{N}(0, I) ).

- Switch to Heavy-Tailed Noise: If Gaussian noise is insufficient, employ heavy-tailed Lévy noise, which is more effective for escaping sharper minima due to its long-range exploration characteristics [6]. The update rule becomes: ( \theta{t+1} = \thetat - \eta \nabla\theta \mathcal{L}(\thetat) + \eta^{1/\alpha} \cdot \xit ) where ( \xit \sim \mathcal{S}_\alpha(0, 1, 0) ) and ( \alpha < 2 ).

- Implement an Adaptive Strategy: Use an algorithm like Adaptive Heavy-Tailed SGD (AHTSGD), which starts with a low ( \alpha ) (heavier tails) for exploration and gradually increases it to 2 (Gaussian) as sharpness stabilizes, balancing exploration and convergence [6].

- Validation or Confirmation Step: After applying the fix, monitor the loss curve for a significant drop from the previous plateau. The optimizer should converge to a new, lower loss value.

Issue: Instability and Oscillations Near presumed Minimum

- Problem Statement: The loss curve exhibits large oscillations or shows signs of divergence after a period of stable convergence.

- Symptoms & Error Indicators:

- Large, non-decaying oscillations in the loss value.

- The sharpness (( \lambda_{\text{max}} ) of the Hessian) is consistently at or above ( 2 / \eta ) [7].

- Possible Causes:

- The learning rate is too high for the current curvature of the loss landscape.

- The noise injection, particularly heavy-tailed noise, is causing large jumps that the optimizer cannot recover from.

- Step-by-Step Resolution Process:

- Measure Sharpness: Estimate the leading eigenvalue of the Hessian (( \lambda_{\text{max}} )) to confirm you are operating at the Edge of Stability [7].

- Reduce Learning Rate: Decrease the learning rate ( \eta ). This raises the stability threshold and can dampen the oscillations.

- Adapt Noise Tails: If using heavy-tailed noise, dynamically increase the tail index ( \alpha ) towards 2 (making the noise more Gaussian) as the optimizer approaches convergence. This reduces the probability of destabilizing large jumps in flatter regions [6].

- Validation or Confirmation Step: The loss curve should stabilize, showing small, decaying oscillations as convergence is achieved. The sharpness should settle near the new, higher stability threshold.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Noise Types on a Multimodal Landscape

This protocol provides a methodology for comparing the performance of different noise types on a controlled, synthetic landscape like the Ackley function, a canonical benchmark for optimizer robustness [6].

- Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the ability of Gaussian vs. Lévy noise to escape local minima and find the global optimum.

- Experimental Setup:

- Function: Use the 2-D Ackley function.

- Initialization: Initialize parameters at a fixed point known to be in a deep local minimum, not the global minimum.

- Optimizers: Run three optimizers from the same initialization:

- Standard Gradient Descent (GD).

- GD with Gaussian noise injection.

- GD with Lévy noise (( \alpha = 1.5 )) injection.

- Hyperparameters: Use the same learning rate for all methods. Scale the noise appropriately for fair comparison [6].

- Data Collection:

- Record the full optimization trajectory (parameter values over time).

- Record the final loss value achieved.

- Count the number of iterations to reach a loss value within 1% of the global minimum.

- Expected Outcome: The Lévy-driven optimizer should demonstrate a higher success rate in escaping the local minimum and finding the global optimum, while the Gaussian optimizer may show improved exploration over standard GD but may still get trapped in some scenarios [6].

The logical relationship between noise injection and its effects on optimization is summarized in the following workflow:

Protocol 2: Tracking Sharpness Dynamics with AHTSGD

This protocol outlines how to investigate the interaction between adaptive heavy-tailed noise and the sharpness of the loss landscape during neural network training [6].

- Objective: To demonstrate how AHTSGD uses the evolving sharpness to modulate its noise distribution and how this correlates with convergence to a flat minimum.

- Experimental Setup:

- Model & Data: Train a small convolutional neural network (CNN) on a benchmark dataset like CIFAR-10.

- Optimizers: Compare SGD, SGD with fixed Lévy noise (( \alpha = 1.5 )), and AHTSGD.

- Sharpness Calculation: Periodically compute (or estimate) the largest eigenvalue of the Hessian of the loss (( \lambda_{\text{max}} )) throughout training.

- Data Collection:

- Record the training and test loss/accuracy.

- Record the trajectory of ( \lambda{\text{max}} ) (sharpness) over training steps.

- For AHTSGD, record the adaptive tail index ( \alphat ) over time.

- Expected Outcome: The sharpness for SGD and fixed-noise SGD will rise and stabilize near the Edge of Stability. AHTSGD will show a similar sharpness trajectory, but its ( \alpha_t ) will start low and increase towards 2 as sharpness stabilizes, resulting in improved generalization performance, especially with poor initializations or on noisy datasets [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" essential for experiments in noisy optimization and landscape analysis.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Lévy α-Stable Distribution | A family of probability distributions used to generate heavy-tailed noise. The tail index ( \alpha ) (where ( 0 < \alpha \leq 2 )) controls how "heavy" the tails are; lower ( \alpha ) allows for rarer but larger jumps [6]. |

| Sharpness ( ( \lambda_{\text{max}}) ) | The largest eigenvalue of the Hessian matrix of the loss function. It is a local measure of curvature and is a key metric for understanding optimizer stability and the width of a minimum [7]. |

| Hölder Exponent ( H(\theta) ) | A measure of the local roughness or regularity of a function at a point ( \theta ). A heterogeneous Hölder exponent across the landscape is a hallmark of a multifractal structure [7]. |

| Fractional Diffusion Theory | A mathematical framework used to model the dynamics of optimizers on complex, multifractal landscapes. It generalizes the standard diffusion theory (Brownian motion) to account for anomalous, non-stationary behaviors observed in deep learning [7]. |

The diagram below illustrates the core adaptive noise adjustment mechanism used in algorithms like AHTSGD, linking sharpness dynamics to noise modulation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do my optimization runs converge quickly but to a poor solution? This is a classic sign of premature convergence, where algorithms like standard PSO get trapped in a local optimum. In noisy environments, this risk increases as noise can create deceptive local minima that trick the optimizer [8] [9].

My gradient-based optimizer fails even when I increase sampling to reduce noise. Why? In high-dimensional problems, you may be encountering the barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially. The signal from the true gradient can become so small that it is impossible to distinguish from the statistical noise, even with extensive sampling, making gradient-based descent ineffective [8].

Which optimizers should I consider for noisy, high-dimensional problems? Recent benchmarking on Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), which feature extremely noisy and complex landscapes, has identified CMA-ES and iL-SHADE (an advanced Differential Evolution variant) as consistently top-performing and robust algorithms [8].

Besides the optimizer itself, what can I adjust to improve results? A key strategy is to adjust your convergence criteria. In noisy regimes, standard tolerance-based criteria can cause premature stopping. Consider implementing more robust criteria, such as requiring a consistent improvement trend over a longer window of iterations or using statistical tests to confirm stagnation.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Premature Convergence in Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Description The swarm's particles quickly cluster around a suboptimal point in the search space, resulting in a final solution that is not the global best. This is a well-known issue with standard PSO, particularly when solving complex, multimodal problems [9].

Diagnosis Checklist

- Early Stagnation: The swarm's global best fitness shows little to no improvement after the initial iterations.

- Loss of Diversity: The particles' positions become very similar, and the swarm behaves almost as a single point.

- Sensitivity to Initial Conditions: Different random seeds lead to convergence on different, suboptimal fitness values.

Solutions

- Adopt Advanced PSO Variants: Use modern PSO algorithms designed to maintain diversity.

- Teaming Behavior PSO (TBPSO): Particles are divided into teams with leaders, creating a more nuanced search dynamic that helps avoid local optima [9].

- Topological Variations: Switch from a global-best (gbest) topology to a local-best (lbest) or Von Neumann topology. These structures slow down information propagation, maintaining swarm diversity for longer and improving the chances of finding the global optimum [10].

- Implement Adaptive Parameters: Replace fixed parameters with adaptive strategies.

- Adaptive Inertia Weight: Use a time-varying inertia weight (e.g., linearly decreasing) or a performance-based adaptive weight. A higher inertia encourages exploration early on, while a lower inertia facilitates fine-tuning exploitation later [10].

- Adaptive Acceleration Coefficients: Dynamically tune the cognitive (

c1) and social (c2) parameters to balance the influence of a particle's own experience versus the swarm's collective knowledge [10].

Problem: Failure of Optimizers in Noisy Quantum Landscapes

Description Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) present a extreme case of noisy optimization due to measurement uncertainty and the barren plateau phenomenon. Benchmarks show that standard PSO, Genetic Algorithms (GA), and basic DE variants "degrade sharply" in these conditions [8].

Diagnosis Checklist

- Exponential Cost Scaling: The number of measurement shots required to resolve a descent direction becomes prohibitively large as the problem size (qubit count) increases.

- Rugged Landscape Visualization: Analysis shows that a smooth, convex basin in a noiseless setting becomes distorted and filled with spurious local minima under finite-shot sampling [8].

Solutions

- Select Noise-Resilient Metaheuristics: Prefer algorithms known for their robustness in noisy, multimodal landscapes.

- Reframe the Problem: Acknowledge that the landscape is inherently stochastic. Techniques from noisy optimization, such as fitness reevaluation or estimation-of-distribution algorithms, can be more appropriate than treating the noise as a simple nuisance.

Experimental Performance Data

The following table summarizes quantitative evidence from a systematic benchmark of over 50 metaheuristics on Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) problems, which are characterized by noisy, multimodal landscapes [8].

Table 1: Optimizer Performance in Noisy VQE Landscapes

| Optimizer | Performance in Noisy Regimes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Consistently best performance | Evolution strategy, adapts its search distribution. |

| iL-SHADE | Consistently best performance | Advanced Differential Evolution with success-based parameter adaptation. |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Robust | Physics-inspired, probabilistically accepts worse solutions. |

| Harmony Search | Robust | Music-inspired, balances memory usage and pitch adjustment. |

| Symbiotic Organisms Search | Robust | Biology-inspired, based on organism interactions. |

| Standard PSO | Degrades sharply | Prone to premature convergence in complex landscapes [8] [9]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Degrades sharply | Standard selection, crossover, and mutation may be insufficient. |

| Standard DE | Degrades sharply | Basic DE variants lack adaptive mechanisms for noise. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Algorithms and Software for Noisy Optimization Research

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| CMA-ES | A state-of-the-art evolutionary algorithm for difficult non-convex and noisy optimization problems. Considered a default choice for robust global optimization. |

| iL-SHADE | A top-performing Differential Evolution variant; ideal for benchmarking when DE is a baseline algorithm. |

| TBPSO (Teaming Behavior PSO) | An improved PSO variant that uses a team-based structure to maintain diversity and avoid local optima [9]. |

| Fitness Variance Sampling | A strategy (e.g., from noisy DE research) that adaptively increases sample size for uncertain solutions, improving fitness estimate accuracy without excessive cost [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Optimizers in Noisy Environments

Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the performance of different optimization algorithms on a noisy, multimodal benchmark problem.

Methods: Based on protocols used for evaluating optimizers for Variational Quantum Algorithms [8].

Problem Selection:

- Primary Benchmark: Use the 1D Transverse-Field Ising model. It provides a well-characterized, multimodal landscape that challenges optimizers.

- Advanced Benchmark: Scale up to a more complex model like the 192-parameter Fermi-Hubbard model to test scalability and performance under extreme ruggedness.

Noise Introduction:

- Simulate the effect of finite-shot quantum measurement by adding Gaussian noise with a standard deviation proportional to

1/sqrt(N), whereNis the number of measurements (shots).

- Simulate the effect of finite-shot quantum measurement by adding Gaussian noise with a standard deviation proportional to

Algorithm Configuration:

- Select a suite of optimizers to test, including standard methods (PSO, GA, DE) and more robust ones (CMA-ES, iL-SHADE).

- Use standard parameter settings for each algorithm as recommended in their respective literature to ensure a fair comparison.

Evaluation Metrics:

- Convergence Accuracy: Record the best-found fitness value after a fixed budget of function evaluations.

- Convergence Reliability: For each algorithm, run multiple trials (e.g., 50) with different random seeds and report the success rate (number of times it finds a solution within a specified tolerance of the global optimum).

- Convergence Speed: Track the number of function evaluations required to reach a target fitness value.

How Noise Distorts Optimization Landscapes

The diagram below illustrates the core challenge of optimization in noisy regimes, transforming a tractable problem into a deceptive one.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What do "intensional" and "extensional" mean in the context of convergence? In the semantics of nondeterministic programs, the intensional characterization describes the internal structure of a computation, such as the step-by-step actions of a sequential algorithm. In contrast, the extensional characterization describes the external, input-output behavior of a program, often represented as structure-preserving functions between mathematical orders. A key result establishes that for bounded nondeterminism, these two representations are equivalent [12].

2. My distributed gradient descent is stuck; could it be at a saddle point? Yes, a common limitation of first-order methods in non-convex optimization is that they can take exponential time to escape saddle points. First-order stationary points include both local minimizers and saddle points, and standard gradient updates can become trapped [13].

3. How can I help my optimization algorithm escape saddle points? Introducing random perturbations to the gradient is a proven method. For a variant of Distributed Gradient Descent (DGD), it has been established that adding a carefully controlled random noise term can help the iterates of each agent converge with high probability to a neighborhood of a common local minimizer, rather than a saddle point [13].

4. What is the "bounded" framework referred to in the title? This framework applies to scenarios where nondeterministic choice is limited, as opposed to "unbounded" choice. Research has shown that for bounded choice operators, continuous semantic models can be constructed that are fully abstract for testing denotational semantics, a property that does not always hold in the unbounded case [12].

5. Why does my simulation fail to converge even with small voltage steps? Convergence failures in solver physics often stem from the complex coupling of equations. Even with an appropriate voltage step, other factors can prevent convergence. Recommendations include switching the solver type (e.g., from Newton to Gummel), enabling gradient mixing models, and reducing the maximum solution update allowed for the drift-diffusion and Poisson equations between iterations [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Convergence Failure in Noisy Gradient Experiments

Common Symptoms and Causes

This section addresses convergence issues in the context of research on noisy computational gradients, particularly for non-convex problems like those encountered in drug development.

| Symptom | Potential Cause |

|---|---|

| Algorithm stalls indefinitely; no progress in loss value. | Trapped near a saddle point [13]. |

| Large consensus error between agents in distributed learning. | The fixed step-size is too large for the network topology [13]. |

| Solver fails to find a self-consistent solution for coupled physics. | High field mobility or impact ionization models are enabled without appropriate stabilizers [14]. |

| Iterations hit the limit without meeting tolerance, but appear close. | The global iteration limit is set too low [14]. |

| Convergence fails immediately at the first increment or time step. | Poor initial guess or requires initialization from equilibrium [14]. |

Step-by-Step Diagnostic and Solution Protocol

Step 1: Establish a Baseline and Simplify

- Action: Before introducing noise or tackling a complex problem, perform an analysis on a simple, well-understood test case to verify the integrity and basic behavior of your model and algorithm [15].

- Thesis Context: This helps isolate whether convergence issues are inherent to the problem's complexity or a flaw in the experimental setup.

Step 2: Systematically Introduce Complexity

- Action: Add nonlinearities and noise one by one. Start with a static, convex problem. Then introduce the non-convexity, then the distributed consensus aspect, and finally the gradient noise [15].

- Thesis Context: This phased approach allows you to pinpoint which specific element (e.g., non-convexity, noise variance) is the source of instability, providing valuable data for adjusting convergence criteria.

Step 3: Fine-Tune Algorithmic Hyperparameters

- Action: Adjust the following parameters, which are critical for noisy, non-convex optimization:

- Noise Variance: Ensure the noise variance is sufficiently small relative to the step size to facilitate convergence to a minimizer's neighborhood [13].

- Fixed Step-Size (

α): Use a sufficiently small fixed step-size. This simplifies theoretical analysis and provides clear control over descent dynamics and perturbation effects, though it typically ensures convergence only to a neighborhood of a solution [13]. - Iteration Limit: Increase the global iteration limit, especially if the solver is slowly approaching the tolerance threshold [14].

Step 4: Implement Advanced Stabilization Techniques

- Action: Based on your problem, apply one of the following:

- For solver physics (e.g., coupled Poisson-drift-diffusion): Change the solver type (Newton/Gummel) or enable a gradient mixing model to stabilize calculations when complex physical models are active [14].

- For gradient-based optimization: If using a full Newton-Raphson solver, ensure it is used with a line search method rather than a modified version for better convergence properties [15].

Step 5: Analyze the Output and Refine the Model

- Action: If a step fails to converge, force the solver to continue and generate an output for the unconverged state. Visualizing these results can reveal localized issues like stress singularities or element distortions, guiding mesh refinement or model correction [15].

Experimental Protocols for Cited Works

Protocol 1: Noisy Distributed Gradient Descent (NDGD) for Saddle Point Escape This protocol is based on the methods described for NDGD to evade saddle points in non-convex optimization [13].

- 1. Objective: Minimize a finite sum of smooth, potentially non-convex functions ( f(\mathbf{x}) = \sum{i=1}^m fi(\mathbf{x}) ) using ( m ) agents over a network graph ( \mathcal{G}(\mathcal{V},\mathcal{E}) ).

- 2. Algorithm: The core update for each agent ( i ) at iteration ( k ) is: ( \hat{\mathbf{x}}^{k+1}i = \sum{j=1}^m w{ij} \hat{\mathbf{x}}^kj - \alpha(\nabla fi(\hat{\mathbf{x}}^ki) + \mathbf{n}^ki) ) where ( \mathbf{n}^ki ) is an injected random perturbation.

- 3. Key Parameters:

- Mixing Matrix (

W): Defined by the network graph, must be doubly stochastic. - Step-size (

α): A fixed, sufficiently small value. - Noise (

n): Random perturbation with controlled, sufficiently small variance.

- Mixing Matrix (

- 4. Success Metrics:

- Convergence of all agents to a specified radius near a common second-order stationary point (local minimizer) with high probability.

- Consensus error among agents below a defined threshold.

Protocol 2: Gradient Descent Noise Reduction for Perfect Models This protocol outlines the gradient descent algorithm for reducing noise in observations of a chaotic dynamical system, assuming a perfect model is known [16].

- 1. Objective: Recover a clean trajectory ( {yi} ) from a noisy observed sequence ( {xi} ), where ( xi = yi + ηi ) and ( ηi ) is observational noise.

- 2. System Dynamics: The underlying clean system is a known, discrete-time map: ( y{i+1} = f(yi) ).

- 3. Algorithm: Minimize the cost function ( F({\hat{y}i}) = \sumi \|xi - \hat{y}i\|^2 + \kappa \sumi \|\hat{y}{i+1} - f(\hat{y}i)\|^2 ) with respect to the estimated trajectory ( {\hat{y}i} ), where ( \kappa ) is a weighting parameter. This is typically done by solving the associated set of differential equations.

- 4. Key Theoretical Insight: The algorithm is guaranteed to converge to the true trajectory for uniformly hyperbolic systems where the angle between stable and unstable manifolds is bounded away from zero, provided the noise level is sufficiently small.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

Consensus Network Graph (𝒢(𝒱,ℰ)) |

Defines the communication topology between computational agents in distributed optimization [13]. |

Mixing Matrix (W) |

A doubly stochastic matrix encoding the network graph; used to compute weighted averages of neighbor states in DGD [13]. |

Fixed Step-Size (α) |

A constant learning rate that provides stability and predictable descent dynamics, crucial for theoretical analysis of convergence under noise [13]. |

Gradient Perturbation (n) |

Injected random noise (e.g., Gaussian) to actively push iterates away from saddle points and towards local minimizers [13]. |

| Lifted Centralized Form | A reformulation technique where all agent variables are stacked into a single high-dimensional vector, enabling the use of classical gradient dynamics for analysis [13]. |

| High Field Mobility Model | A physical model that, when enabled in a solver, can cause convergence difficulties without stabilizers like gradient mixing [14]. |

| Gradient Mixing | A solver option (fast or conservative) that stabilizes convergence when advanced physical models (e.g., high field mobility) are active [14]. |

Decision Workflow for Convergence Problems

The following diagram outlines a systematic diagnostic process for resolving convergence failures.

Intensional vs. Extensional Semantics of Nondeterminism

This diagram illustrates the relationship between the intensional and extensional views of computation and their semantic equivalence in the bounded framework.

Resilient Algorithms and Robust Frameworks: Methodologies for Noisy Gradient Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are CMA-ES and iL-SHADE recommended over standard gradient-based optimizers for VQEs?

Variational Quantum Algorithm (VQA) landscapes, especially under finite sampling noise, become distorted and rugged, causing the gradients used by classical methods to vanish or become unreliable [8]. This is compounded by the barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with the number of qubits [8]. CMA-ES and iL-SHADE are population-based metaheuristics that do not rely solely on local gradient information. They maintain a diverse set of candidate solutions, enabling them to navigate these noisy, multimodal landscapes and avoid getting trapped in spurious local minima [17].

Q2: What is the 'winner's curse' in noisy VQE optimization and how can it be mitigated?

The "winner's curse" is a statistical bias where the lowest observed energy value in an optimization run is artificially low due to random sampling noise, not because it represents a better solution [17]. This can cause the optimizer to converge prematurely to a false minimum. When using population-based optimizers like CMA-ES or iL-SHADE, a robust mitigation strategy is to track the population mean energy instead of just the best individual's energy. This provides a more stable and reliable convergence criterion that is less sensitive to stochastic fluctuations [17].

Q3: My optimizer is converging prematurely. How can I improve its exploration capability?

Premature convergence often indicates an imbalance between exploration and exploitation. For iL-SHADE, consider implementing an external archive mechanism to preserve elite individuals and maintain population diversity, preventing the algorithm from collapsing to a local optimum too quickly [18]. Another general strategy is the Heterogeneous Perturbation–Projection (HPP) method, which adds stochastic noise to a portion of the swarm agents and then projects them back onto the feasible solution space. This has been shown to enhance exploration and help algorithms escape local traps [19].

Q4: How do I set the convergence criteria for a noisy optimization?

In noisy environments, standard tolerance-based criteria can be triggered by noise rather than true convergence. It is often more effective to implement a statistical stopping rule. One can monitor a rolling average of the best energy over a window of iterations and stop when the improvement falls below a statistically significant threshold relative to the observed noise level. Another method is to set a maximum budget of iterations or function evaluations based on prior benchmarking [8] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Runs Issue: Significant variation in the final energy or parameters across different runs of the same experiment.

- Solution 1: Increase the population size. A larger population improves the algorithm's sampling of the landscape and makes it more resilient to noise. For CMA-ES, the population size is a key hyperparameter that can be adjusted from its default [8].

- Solution 2: Use a fixed random seed for the classical optimizer. This ensures reproducibility during the development and debugging phases.

- Solution 3: Conduct multiple independent runs and report the mean and standard deviation of the results, as is standard practice in benchmarking studies [8].

Problem: Excessive Resource Consumption Issue: The optimizer is taking too long per iteration or requires an infeasible number of measurement shots.

- Solution 1: For iL-SHADE, leverage its linear population size reduction feature. This strategy starts with a larger population for broad exploration and gradually reduces it to focus computational resources on promising regions, improving efficiency [18].

- Solution 2: Optimize the shot allocation strategy. Instead of using a fixed number of shots for all energy evaluations, consider dynamic strategies that allocate more shots only when the algorithm is nearing convergence or when it needs to resolve small energy differences.

Problem: Failure to Find the Known Ground State Issue: The optimizer consistently returns an energy higher than the known theoretical ground state.

- Solution 1: Visually inspect the optimization landscape, if possible (e.g., for a 2-parameter slice). This can reveal if the problem is ruggedness or a barren plateau [8].

- Solution 2: Re-evaluate the final best parameters with a very large number of shots. This averages out the sampling noise and provides a less biased estimate of the true energy, helping to confirm if the "winner's curse" is at play [17].

- Solution 3: Check the ansatz design. An ansatz that is not expressive enough or is prone to barren plateaus will limit the achievable accuracy regardless of the optimizer's performance [17].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for benchmarking metaheuristic optimizers on VQA problems, based on established methodologies in the field [8] [17].

Summary of a Typical Benchmarking Protocol [8] [17]:

| Phase | Objective | Model Example | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Screening | Filter a large set of algorithms under high-noise conditions. | 1D Ising Model (3 Qubits) | Convergence speed, success rate. |

| 2. Scaling Tests | Evaluate how performance degrades with problem size. | Ising Model (3 to 9 Qubits) | Scaling of evaluations-to-solution, success rate. |

| 3. Advanced Models | Validate top performers on realistic, complex problems. | Hubbard Model / Quantum Chemistry (e.g., LiH) | Final accuracy (error from true ground state), reliability. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key components for a VQE optimization experiment.

| Item / "Reagent" | Function / Explanation | Example Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Testbed Models | Well-understood physical systems used as benchmarks to evaluate optimizer performance. | 1D Ising Model, Fermi-Hubbard Model, H₂/LiH molecules [8] [17]. |

| Ansatz Circuit | The parameterized quantum circuit that prepares the trial wavefunction. Its structure is critical for trainability. | Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), Variational Hamiltonian Ansatz (VHA) [17]. |

| Noise Model | A computational model that emulates the statistical noise from a finite number of quantum measurements. | Finite-shot sampling noise (Gaussian with variance ~ $1/N_{\text{shots}}$) [8] [17]. |

| Classical Optimizer (Metaheuristic) | The algorithm that adjusts the ansatz parameters to minimize the energy. | CMA-ES, iL-SHADE, Simulated Annealing (Cauchy), Harmony Search [8]. |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifiable measures used to compare the effectiveness and efficiency of different optimizers. | Mean best fitness, convergence rate, success probability, number of function evaluations [8]. |

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes findings from recent studies that benchmarked various optimizers, highlighting the robust performance of CMA-ES and iL-SHADE.

Table: Benchmarking results of metaheuristics on noisy VQE landscapes [8] [17].

| Optimizer | Type | Performance on Noisy VQE Landscapes | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMA-ES | Evolution Strategy | Consistently ranked among the best performers [8] [17]. | Adapts its search distribution; excellent for rugged, ill-conditioned landscapes. |

| iL-SHADE | Differential Evolution | Consistently ranked among the best performers [8] [17]. | Features linear population size reduction; history-based parameter adaptation. |

| Simulated Annealing (Cauchy) | Physics-inspired | Showed robustness and good performance [8]. | Uses a Cauchy distribution for exploration; good at escaping local minima. |

| Harmony Search (HS) | Music-inspired | Showed robustness and good performance [8]. | Mimics musical improvisation; balances memory usage and pitch adjustment. |

| Symbiotic Organisms Search (SOS) | Bio-inspired | Showed robustness and good performance [8]. | Models symbiotic interactions; no algorithm-specific parameters to tune. |

| Particle Swarm Opt. (PSO) | Swarm-based | Performance degraded sharply with noise [8]. | Can suffer from premature convergence in noisy, multimodal settings. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Evolutionary | Performance degraded sharply with noise [8]. | Standard crossover and mutation operators may not be sufficiently adaptive. |

Workflow for Reliable VQE Optimization

The following diagram integrates the core components—ansatz, quantum computer, and classical optimizer—into a robust workflow that includes specific strategies for handling noise.

Gradient Descent with Backtracking Line Search (GD-BLS) for Noisy Convex Functions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using GD-BLS over standard GD in a noisy setting? GD-BLS does not require pre-knowledge of the smoothness constant (L) and automates the step-size selection. For noisy convex optimization, it provides guaranteed convergence rates even when the expected objective function ( F(\theta) := \mathbb{E}[f(\theta,Z)] ) is not necessarily L-smooth, a scenario where standard stochastic gradient descent may fail to converge [20] [21].

Q2: My convergence seems slow. How can I improve the error rate with a fixed computational budget?

The convergence rate can be significantly improved by using an iterative refinement strategy. Instead of running a single long optimization, the process is stopped early when the gradient is sufficiently small. The residual budget is then used to optimize a finer approximation of the objective function. Repeating this J times improves the error from ( \mathcal{O}{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-0.25}) ) to ( \mathcal{O}{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-\frac{1}{2}(1-\delta^{J})}) ) for a user-specified parameter δ [20] [21].

Q3: What should I do if the gradient noise is heavy-tailed?

The algorithm and its convergence guarantees can be adapted if you have knowledge of the parameter α where ( \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla\theta f(\theta\star,Z)\|^{1+\alpha}] < \infty ). In this case, the iterative refinement strategy can achieve an error of size ( \mathcal{O}_{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-\frac{\alpha}{1+\alpha}(1-\delta^{J})}) ) [20].

Q4: How does GD-BLS help with saddle points in non-convex problems? While GD-BLS is discussed here for convex problems, the principle of injecting noise can evade saddle points. In non-convex settings, perturbed gradient steps can help escape saddle points and converge to a local minimizer, as shown in analyses of noisy distributed gradient descent [13].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow convergence | Single optimization run without iterative refinement | Implement multi-stage optimization with iterative refinement (J > 1) [20] [21]. |

| High final error | Insufficient computational budget (B) for desired accuracy |

Increase budget B; validate against theoretical convergence bounds [20]. |

| Algorithm not converging | Function violates strict convexity assumption; gradient noise violates finite moment assumptions | Verify problem convexity; check if ( \mathbb{E}[|\nabla\theta f(\theta\star,Z)|^2] < \infty ) [20]. |

| Difficulty tuning parameters | Manual tuning for specific functions F and f |

Use GD-BLS; beyond knowing α, it does not require tuning parameters for specific functions [20]. |

Theoretical Convergence Rates & Parameters

The tables below summarize the key convergence rates and parameters for GD-BLS in noisy convex optimization, providing a reference for setting experimental expectations.

Table 1: Convergence Rates for GD-BLS with Computational Budget B

| Condition | Strategy | Convergence Rate | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( \mathbb{E}[|\nabla f(\theta_\star,Z)|^2] < \infty ) | Single Run | ( \mathcal{O}_{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-0.25}) ) | Budget B [20] |

| ( \mathbb{E}[|\nabla f(\theta_\star,Z)|^2] < \infty ) | Iterative (J stages) |

( \mathcal{O}_{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-\frac{1}{2}(1-\delta^{J})}) ) | δ ∈ (1/2, 1) [20] [21] |

| ( \mathbb{E}[|\nabla f(\theta_\star,Z)|^{1+\alpha}] < \infty ) | Iterative (J stages) |

( \mathcal{O}_{\mathbb{P}}(B^{-\frac{\alpha}{1+\alpha}(1-\delta^{J})}) ) | δ ∈ (2α/(1+3α), 1) [20] |

Table 2: Key Algorithm Parameters and Their Roles

| Parameter | Description | Role in Convergence |

|---|---|---|

B |

Total computational budget (e.g., gradient evaluations) | Directly controls final error rate [20]. |

J |

Number of iterative refinement stages | Improves exponent in convergence rate [20] [21]. |

δ |

Tuning parameter for budget allocation across stages | Balances resource allocation between initial and refinement stages [20]. |

α |

Moment parameter for gradient noise | Tailors algorithm to heavy-tailed noise distributions [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating GD-BLS Performance

This protocol outlines the key steps for empirically validating the convergence of GD-BLS on a noisy convex optimization problem, aligning with the thesis context of adjusting convergence criteria.

Problem Formulation:

- Define a strictly convex, but not necessarily L-smooth, objective function ( F(\theta) ).

- Identify a noise model

Zsuch that the unbiased gradient oracle∇f(θ, Z)satisfies ( \mathbb{E}[\|\nabla\theta f(\theta\star,Z)\|^2] < \infty ) or a similar moment condition.

Baseline Establishment:

- Run the standard GD-BLS algorithm (without iterative refinement) with a fixed total budget

B. - Record the final error ( \|\hat{\theta} - \theta_\star\| ) over multiple independent trials.

- Plot the average error against

Bon a log-log scale and verify it aligns with the ( B^{-0.25} ) rate.

- Run the standard GD-BLS algorithm (without iterative refinement) with a fixed total budget

Iterative Refinement Implementation:

- Allocation: Divide the total budget

BacrossJstages. The budget for stagejcan be proportional to ( \delta^j ) for a chosenδ. - Stage 1: Run GD-BLS on the original problem until the gradient norm is below a threshold or the allocated budget for this stage is exhausted.

- Stage 2 to J: Using the solution from the previous stage as the initial point, run GD-BLS again on a finer approximation of

F(e.g., using a larger sample size for the SAA) with the new allocated budget. - The final solution is the output from the last stage,

J.

- Allocation: Divide the total budget

Performance Comparison:

- Compare the error of the iteratively refined solution against the baseline single-run solution.

- Empirically demonstrate the improved convergence rate, aiming for ( B^{-\frac{1}{2}(1-\delta^{J})} ).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the iterative refinement process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Components for Noisy GD-BLS Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Strictly Convex Test Function | Serves as the ground-truth objective ( F(\theta) ) to validate convergence properties and error calculations [20] [21]. |

| Unbiased Gradient Oracle (∇f(θ, Z)) | A computational procedure that provides noisy gradients; its statistical properties (e.g., finite variance) are critical for theoretical guarantees [20]. |

| Backtracking Line Search Routine | An algorithm that automatically determines an appropriate step size at each iteration, eliminating the need for Lipschitz constant knowledge [20] [21]. |

| Computational Budget (B) | A fixed limit on the total number of gradient evaluations or iterations, central to the finite-budget convergence analysis [20]. |

| Iterative Refinement Scheduler | A script that manages the multi-stage optimization process, including budget allocation across stages and stopping criteria [20] [21]. |

Epoch Mixed Gradient Descent (EMGD) is a hybrid optimization algorithm designed to minimize smooth and strongly convex functions by strategically combining full gradient and stochastic gradient computations. This approach addresses a key challenge in large-scale machine learning: reducing the computational burden of frequent full gradient calculations while maintaining linear convergence rates. EMGD achieves this through an epoch-based structure where each epoch computes only one full gradient but performs numerous cheaper stochastic gradient steps [22] [23].

The fundamental innovation of EMGD lies in its mixed gradient descent steps, which use a combination of a single full gradient (computed at the start of an epoch) and multiple stochastic gradients to update intermediate solutions. Through a fixed number of these mixed steps, EMGD improves solution suboptimality by a constant factor each epoch, achieving linear convergence without the typical condition number dependence in full gradient evaluations [22]. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that EMGD finds an ε-optimal solution by computing only O(log 1/ε) full gradients and O(κ² log 1/ε) stochastic gradients, where κ represents the condition number of the optimization problem [23].

Table: Key Characteristics of EMGD Algorithm

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Problem Domain | Smooth and strongly convex optimization [22] [23] |

| Gradient Types Used | Full gradients and stochastic gradients [22] [23] |

| Key Innovation | Mixed gradient descent steps combining both gradient types [23] |

| Full Gradient Complexity | O(log 1/ε) (condition number independent) [23] |

| Stochastic Gradient Complexity | O(κ² log 1/ε) [23] |

| Convergence Rate | Linear convergence [22] [23] |

Implementation Guide and Workflow

Implementing EMGD effectively requires careful attention to its algorithmic structure and parameter configuration. The method operates through distinct epochs, each consisting of an initial full gradient calculation followed by a series of mixed gradient descent steps. This architecture strategically interleaves computationally expensive but accurate full gradients with cheaper stochastic approximations to optimize the trade-off between convergence speed and computational cost [22] [23].

Algorithm Parameters and Configuration

EMGD depends on three crucial parameters: the stepsize (h), the maximum number of stochastic steps per epoch (m), and a strong convexity parameter (ν) which can be set to zero if no strong convexity information is available [22] [24]. The number of mixed gradient steps within each epoch is determined by a geometric law, with the expected number of iterations ξ(m,h) bounded between (m+1)/2 and m [24]. Proper tuning of these parameters is essential for achieving the theoretical computational advantages.

Computational Advantages

The primary computational benefit of EMGD emerges from its condition number-independent access to full gradients. For ill-conditioned problems where traditional gradient descent requires O(√κ log 1/ε) full gradient evaluations, EMGD maintains the same convergence rate with only O(log 1/ε) full gradient computations [22] [23]. This makes it particularly advantageous in scenarios where full gradient calculations are prohibitively expensive, such as training models on massive datasets where computing gradients across all training examples requires substantial computational resources [25] [26].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: Why does EMGD require advance knowledge of the condition number for parameter tuning, and how can I estimate this in practice?

EMGD's parameter settings, particularly the number of mixed gradient steps, theoretically depend on the problem's condition number κ to achieve optimal convergence [22]. In practice, if the condition number is unknown, you can implement an adaptive strategy: begin with a conservative estimate and monitor convergence patterns. For ill-conditioned problems common in drug development datasets, consider diagnostic techniques such as eigenvalue analysis of the Hessian matrix or progressive condition number estimation through limited singular value computations [22].

Q2: How does EMGD compare to other variance-reduced stochastic methods like SAG and SVRG, particularly for regularized empirical risk minimization?

EMGD occupies a distinct position in the landscape of stochastic optimization algorithms. Compared to SAG, EMGD offers theoretical advantages for constrained optimization problems and provides a substantially simpler convergence proof [22]. However, for the typical regularized empirical risk minimization where the condition number κ ≈ n/C′ (with n being the number of training examples), SAG may outperform EMGD [22]. Unlike SVRG, which achieves linear dependence on the condition number, EMGD exhibits quadratic dependence (O(κ² log 1/ε)) in its stochastic gradient count [24]. The method works best when κ ≤ n^(2/3), where it can theoretically outperform Nesterov's accelerated gradient descent [22].

Q3: What are the practical limitations of fixing the number of inner loop steps in advance, and can this be made adaptive?

The requirement to preset the number of mixed gradient steps (m) based on the condition number represents a significant practical limitation [22]. This fixed approach cannot exploit potentially more favorable local curvature or adaptive step sizes during optimization [22]. For dynamic adjustment, you can implement heuristic monitoring of stochastic gradient variance or solution improvement per step, modifying m adaptively. In drug development applications with non-stationary data streams, consider implementing a progressive tuning strategy where you periodically reassess and adjust m based on recent convergence behavior [22].

Q4: What convergence diagnostics are most appropriate for monitoring EMGD progress in noisy environments?

When applying EMGD in environments with substantial gradient noise, such as in stochastic simulation models for drug response, traditional convergence measures can be misleading. Implement multiple complementary diagnostics: (1) monitor the norm of the full gradient at epoch boundaries, (2) track objective function values using a held-out validation set, and (3) compute moving averages of stochastic gradient variances [22] [27]. For the high-noise scenarios common in biochemical assay data, consider implementing the normalization techniques similar to those used in GT-NSGDm for heavy-tailed noise distributions [27].

Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Protocol: Comparative Convergence Analysis

Objective: Evaluate EMGD performance against baseline optimizers (SGD, SAG, full GD) on a regularized logistic regression problem simulating drug response prediction [22] [24].

Procedure:

- Dataset Preparation: Utilize a standardized benchmark dataset with n = 10,000 samples and d = 500 features, incorporating synthetic noise with heavy-tailed characteristics to emulate biological variability [27].

- Parameter Initialization: For EMGD, set stepsize h = 0.1/L (where L is the Lipschitz constant), number of epochs = 20, and inner iterations m = 20κ² [22] [23].

- Convergence Monitoring: At each epoch, compute and record full objective value, gradient norm, and wall-clock time [22].

- Termination: Execute all algorithms until they reach ε = 10^(-6) accuracy or complete 50 epochs [24].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experiment | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth Strongly Convex Test Functions | Benchmarking convergence properties | Generate with controllable condition number κ [22] [23] |

| Regularized Logistic Regression | Empirical risk minimization prototype | L2-regularization with tunable parameter λ [24] |

| Stochastic Gradient Oracle | Provides noisy gradient estimates | Implement with controlled variance settings [22] [23] |

| Full Gradient Computator | Benchmark for accuracy assessment | Vectorized for performance [25] [26] |

| Condition Number Estimator | Parameter tuning guidance | Power iteration for largest eigenvalue [22] |

Protocol: Condition Number Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: Characterize how EMGD performance scales with increasing condition number κ and compare with theoretical predictions [22] [23].

Procedure:

- Problem Generation: Create a test suite of quadratic functions with condition numbers systematically varying from 10¹ to 10⁶ [22].

- Fixed Budget Evaluation: Execute EMGD for exactly 20 epochs across all conditions, measuring final accuracy [22].

- Workload Measurement: Record the total number of stochastic and full gradient computations required to reach ε = 10^(-6) accuracy [23].

- Comparison Framework: Evaluate against SAG and SVRG using standardized implementations from optimization libraries [24].

Advanced Technical Considerations

Within the broader thesis context of adjusting convergence criteria for noisy computational gradients, EMGD provides a compelling case study in algorithm design that explicitly accounts for gradient uncertainty. The method's theoretical foundation demonstrates that careful orchestration of high-accuracy (full gradient) and low-accuracy (stochastic gradient) computational primitives can yield superior overall efficiency [22] [23]. This principle extends beyond optimization to other computational domains in scientific research where heterogeneous computational resources must be strategically allocated.

For drug development professionals working with particularly noisy gradient estimates from biological assays or stochastic simulations, consider enhancing EMGD with normalization techniques inspired by recent methods for heavy-tailed noise distributions [27]. These modifications can improve robustness when the gradient noise characteristics deviate from standard assumptions, a common scenario in real-world biochemical data. The integration of gradient clipping or adaptive batch sizes within the EMGD framework may further stabilize convergence for challenging optimization landscapes encountered in molecular design and dose-response modeling [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind DF-GDA's improved convergence speed? DF-GDA enhances convergence through a Dynamic Fractional Parameter Update (DAFPU) mechanism. Instead of updating all parameters in every iteration, it selectively updates a fraction of model parameters based on the current training status and the rate of change in the loss function. This adaptive approach manages the high-dimensional parameter space more efficiently than traditional methods that update all parameters simultaneously, leading to faster and more stable convergence [28].

Q2: How does DF-GDA improve robustness against noisy or mislabeled data? The algorithm incorporates several features to handle annotation noise:

- Fractional Parameter Updates: By updating only a subset of parameters per iteration, it limits the influence of individual noisy data samples.

- Soft Quantization: This smoothes parameter transitions, maintaining stability despite data inconsistencies.

- Adaptive Temperature Control: An entropy-driven schedule encourages broader exploration early in training, helping the model avoid overfitting to suboptimal solutions caused by mislabeled data [28].

Q3: In what scenarios does DF-GDA particularly outperform optimizers like SGD and Adam? DF-GDA demonstrates superior performance in complex, non-convex optimization landscapes prone to local minima. This is particularly evident in high-dimensional tasks such as image classification (e.g., on ImageNet), video understanding (e.g., on Kinetics-700), natural language processing, and bioinformatics. Its ability to balance global exploration with precise local refinement makes it advantageous for these challenging domains [28].

Q4: What is the computational overhead of DF-GDA, and is it suitable for large-scale models? DF-GDA is designed for large-scale applications. The DAFPU mechanism itself reduces computational cost by selectively ignoring a large portion of parameters during each update. Extensive experiments on large-scale datasets like ImageNet (with 1.28 million training images) and Kinetics-700 (with approximately 650,000 video clips) validate its scalability and efficiency [28].

Q5: How does the "temperature" parameter function in DF-GDA? The temperature parameter originates from deterministic annealing and controls the exploration-exploitation trade-off. It starts high, promoting exploration of the loss landscape to escape poor local minima. As training progresses, the temperature adaptively decreases, shifting the focus to precise refinement and convergence. This schedule is autonomously managed based on the optimization trajectory [28] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow initial convergence | Temperature schedule is too aggressive, forcing exploitation too early. | Adjust the annealing schedule to allow for a longer, higher-temperature exploration phase. |

| Model getting stuck in suboptimal solutions | The fraction of parameters updated per iteration is too low. | Increase the base value for the dynamic fractional parameter update to encourage more widespread exploration. |

| Unstable training loss | Learning rate is too high for the chosen temperature schedule. | Decay the learning rate in conjunction with the decreasing temperature to maintain stability [28]. |

| Poor generalization despite low training loss | Model is over-exploiting and converging to a sharp minimum. | Leverage the entropy-driven guidance to navigate towards smoother, flatter minima known to generalize better [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking DF-GDA Performance

For researchers aiming to validate DF-GDA against other optimizers, the following methodology, derived from established experimental setups, is recommended [28]:

Dataset Selection: Employ a diverse set of benchmarks. Core large-scale datasets should include:

- ImageNet: For image classification (1.28M training images, 1000 classes).

- Kinetics-700: For video action recognition (~650,000 video clips, 700 classes).

- Supplementary datasets can include MNIST, CIFAR variants, and domain-specific data from healthcare or biology.

Model Architecture: Choose standard deep networks (e.g., ResNet, Vision Transformers) relevant to your task to ensure fair comparison.

Optimizer Configuration:

- DF-GDA: Implement the adaptive temperature schedule and DAFPU algorithm.

- Baselines: Compare against state-of-the-art optimizers including SGD with momentum, Adam, and Shampoo.

Evaluation Metrics: Track and compare the following quantitative metrics throughout training:

- Training and validation loss/accuracy over epochs.

- Time (or number of iterations) to reach a target accuracy.

- Final performance on a held-out test set.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential computational "reagents" for implementing DF-GDA in experimental studies.

| Research Reagent | Function in the DF-GDA Framework |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Fractional Parameter Update (DAFPU) | Core algorithm that selects a subset of model parameters for update each iteration, balancing exploration and computational cost [28]. |

| Adaptive Temperature Schedule | An entropy-based controller that manages the exploration-exploitation trade-off, analogous to the cooling schedule in physical annealing [28]. |

| Mean Field Gradient Estimates | Provides a probabilistic framework for estimating variable values, guiding the parameter updates under the current temperature regime [28]. |

| Soft Quantization Mechanism | Ensures that parameter updates remain within feasible ranges, enhancing the stability of the optimization process [28]. |

| Multifractal Loss Landscape Model | A theoretical framework modeling complex loss landscapes, explaining GD dynamics and their navigation toward flat minima [7]. |

Comparative Performance of Optimizers

The following table summarizes quantitative results from benchmarking DF-GDA against other standard optimizers across key performance metrics [28].

| Optimizer | Convergence Speed | Robustness to Noise | Escape from Local Minima | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF-GDA | Superior | Superior | Superior | Medium |

| SGD | Medium | Low | Low | High |

| Adam | High | Medium | Medium | High |

| Simulated Annealing | Low | Medium | High | Low |

| Shampoo | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

DF-GDA Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines a high-level workflow for implementing and testing the DF-GDA optimizer in a research setting.

Core Concepts: Design Space and Robust Optimization

What is a Design Space?

The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Q8 guideline defines a Design Space as "The multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables (e.g., material attributes) and process parameters that have been demonstrated to provide assurance of quality. Working within the design space is not considered as a change. Movement out of the design space is considered to be a change and would normally initiate a regulatory post-approval change process." [30] [31]

In practical terms, the design space is the established range of process parameters and material attributes that consistently produces a product meeting its Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs). Knowledge of product or process acceptance criterion is crucial in design space generation and use. [31]

What is Robust Optimization?

Robust optimization is an advanced technique used to find the optimal process set points within the design space where the process is least sensitive to inherent noise and variation.

- Standard Optimization works to find a solution that meets all CQA requirements.

- Robust Optimization does the same but also works to find the point in the design space where the process is most stable. Mathematically, this "sweet spot" is often found where the first derivative of each response with respect to each noise factor is zero. [30]

The core relationship between process parameters and quality is often described by the transfer function: CQAs = f(CPPs, CMAs) [32] Where CPPs are Critical Process Parameters and CMAs are Critical Material Attributes.

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Design Space Development

FAQ 1: My process model passes validation, but my real-world failure rates are high. Why?

Issue: This is a classic sign of a model that describes the average response well but does not adequately account for the inherent variation in process parameters and noise factors.

Solution:

- Implement Monte Carlo Simulation: Use the mathematical model from your characterization studies and inject variation for each factor at its targeted set point. Include the residual variation (Root Mean Squared Error - RMSE) from the model, which accounts for analytical method variation and other uncontrolled factors. [30]

- Target Appropriate PPM Rates: The simulation should target an out-of-specification (OOS) capability in parts per million (PPM) of less than 100 for each CQA. [30]

- Visualize with Edge-of-Failure Graphs: These graphs help visualize the design margin and failure rates, showing where OOS events (red dots) begin to occur. [30]

FAQ 2: How do I handle the "Noisy Gradients" in my optimization algorithm during process characterization?

Issue: In computational optimization, gradient noise can destabilize the convergence of algorithms, especially when dealing with complex, non-linear process models. This is directly relevant to research on adjusting convergence criteria for noisy computational gradients.

Solution:

- Leverage Advanced Algorithmic Strategies: Research in nonconvex stochastic optimization under heavy-tailed noise conditions suggests that techniques like gradient normalization, gradient tracking, and momentum can be used to cope with heavy-tailed noise on distributed nodes, ensuring optimal convergence rates. [27] While originating from machine learning, these principles are applicable to stabilizing optimization in pharmaceutical process models.

- Incorurate Realistic Noise Conditions: Ensure your experimental design (DoE) and subsequent model building include realistic noise factors and that your robust optimization algorithm is configured to directly manage key uncertainties (e.g., material attribute variation, sensor precision). [33]

FAQ 3: Is my design space visualization the same as my "Safe Operating Region"?

Issue: A common misconception is that any combination of parameters within the white space of a 2D contour plot is safe to operate. The visualization often represents the mean response, not the variation of individual batches. [30]

Solution:

- Differentiate between Mean Response and Unit-to-Unit Variation: The visualized design space (e.g., contour plot) shows where the average response meets CQAs. It does not guarantee that every single batch, vial, or syringe will be in specification. [30]

- Define an Effective Design Space: The region you file with health authorities and use for process control (the Effective Design Space) is typically much smaller than the full visualized space. It is the region where no OOS events occur or where you have defined adjustments to correct for processing conditions. [30]

- Use Simulation to Define Safe Ranges: Use Monte Carlo simulation to determine Normal Operating Ranges (NOR) and Proven Acceptable Ranges (PAR) that keep PPM failure rates below your target. [30]

FAQ 4: My robust optimization requires too many experimental runs. How can I be more efficient?

Issue: A full robust optimization that includes two-factor interactions and quadratic terms can be resource-intensive.

Solution:

- Conduct a High-Level Risk Assessment First: Use a risk assessment to identify which process parameters and material attributes are likely to have the greatest impact on drug substance quality. This prioritizes factors for your DoE. [30]

- Adopt a Phase-Appropriate Approach: Preliminary understanding of the design space can occur early, but it should be well-defined by the end of Phase II development, prior to Process Validation Stage 1. This ensures process and specification stability before committing to large-scale studies. [31]

- Consider Alternative Representations: For highly multidimensional spaces, using a convex hull or cluster-based representation of the design space, instead of simple independent ranges for each variable, can be a more efficient way to define the operable region without over-restricting it. [32]

Experimental Protocols for Robust Optimization

A 12-Step Workflow for Building a Robust Design Space

The following workflow integrates steps from established industry practices for building a process model and using it for development. [30]

Key Steps in the Robust Optimization Workflow

Protocol: Conducting Robust Optimization (Step 7)

Objective: To find the process set points that not only meet all CQA targets but also minimize the transmitted variation, thereby achieving a "sweet spot."

Methodology: