Optimizing Geometry Convergence Thresholds for Molecular Stiffness: A Practical Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive framework for computational chemists and drug development researchers to master geometry optimization by strategically selecting convergence thresholds tailored to molecular stiffness.

Optimizing Geometry Convergence Thresholds for Molecular Stiffness: A Practical Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for computational chemists and drug development researchers to master geometry optimization by strategically selecting convergence thresholds tailored to molecular stiffness. It bridges foundational theory with practical application, explaining how stiffness influences the potential energy surface and how to adjust energy, gradient, and step criteria in popular software like xtb and AMS. The guide further offers advanced troubleshooting protocols for challenging systems and presents a rigorous methodology for validating optimization outcomes through frequency analysis and benchmark comparisons, ultimately enabling more reliable and efficient predictions of molecular behavior in drug discovery pipelines.

Understanding Molecular Stiffness and Its Impact on the Potential Energy Surface

Defining Molecular Stiffness in the Context of Potential Energy Surfaces

Troubleshooting Guide: Geometry Optimization and Stiffness Analysis

Q1: My geometry optimization is converging very slowly. How is this related to molecular stiffness? Slow convergence often occurs when optimizing "soft" molecules with shallow potential energy surfaces (PES) or when the initial Hessian (second derivative matrix) is a poor guess. The curvature of the PES, which defines stiffness, directly impacts the optimization path. Shallow, flat regions (low stiffness) cause small energy changes and gradient norms per step, leading to slower progress [1].

Q2: The optimizer finds a structure, but frequency calculations reveal imaginary vibrations. What went wrong? This indicates convergence to a transition state (saddle point) instead of a minimum. The optimization likely started with an inaccurate initial Hessian or used steps too large for the local PES topography. For stiff molecules with deep, narrow potential wells, this can happen if the initial model Hessian underestimates the true curvature [2].

Q3: How does molecular stiffness affect the choice of convergence thresholds? Stiffer molecules (with rapidly changing gradients) often require tighter convergence thresholds to accurately capture the equilibrium geometry, as small displacements cause large energy changes. Softer molecules may converge sufficiently with normal thresholds but risk stopping in shallow regions of the PES if thresholds are too loose [1] [2] [3].

The table below summarizes standard geometry convergence criteria from two computational chemistry packages, ORCA and xtb.

| Package | Threshold Level | Energy Convergence (Eh) | Gradient Norm Convergence (Eh/α) | Max Displacement (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA [2] | LooseOpt | 3e-5 | 5e-4 | 7e-3 |

| Normal (Default) | 5e-6 | 1e-4 | 2e-3 | |

| TightOpt | 1e-6 | 3e-5 | 6e-4 | |

| VeryTightOpt | 2e-7 | 8e-6 | 1e-4 | |

| xtb [3] | loose | 5e-5 | 4e-3 | - |

| normal (Default) | 5e-6 | 1e-3 | - | |

| tight | 1e-6 | 8e-4 | - | |

| vtight | 1e-7 | 2e-4 | - |

Q4: What is the best coordinate system for optimizing large, flexible molecules? For large, flexible (soft) molecules with many degrees of freedom, redundant internal coordinates are generally recommended as they provide a more natural description of molecular motions like bond stretching and angle bending. If this fails, Cartesian coordinates can be attempted, though convergence may be slower [2].

FAQ: Molecular Stiffness and Computational Protocols

Q: What is the fundamental definition of molecular stiffness on a PES? Molecular stiffness is determined by the curvature of the PES around a minimum. A steeper curvature corresponds to a higher force constant, leading to higher vibrational frequencies and a stiffer, less flexible molecular structure in that particular degree of freedom [1] [4].

Q: Which initial Hessian is recommended for optimizing a typical organic molecule to its minimum? For minimizing standard organic molecules, the Almlöf model Hessian is a good default choice. It provides a better approximation of the initial PES curvature than a unit matrix, leading to faster and more reliable convergence [2].

Q: How can I optimize a molecule in an excited state?

You can perform an excited-state geometry optimization using methods like TD-DFT. In packages like ORCA, this involves specifying the %tddft block to define the state of interest and then using a standard Opt keyword [2].

Q: My molecule has both rigid and flexible regions. How can I ensure the rigid parts are optimized correctly? For systems with mixed stiffness, using a tight optimization threshold ensures that the geometry of rigid, stiff parts (with deep potential wells) is precisely located. Using a better initial Hessian (e.g., from a lower-level frequency calculation) can also greatly help [2].

Experimental Protocol: Calculating and Analyzing Molecular Stiffness

Objective: To locate a minimum-energy molecular geometry and quantify its stiffness by analyzing the PES curvature.

Methodology:

System Setup

- Obtain an initial molecular geometry from a database or build it using chemical intuition.

- Select an appropriate computational method (e.g., DFT with a suitable functional and basis set) for your system [2].

Geometry Optimization

- Keyword: Use the

Optkeyword in your computational chemistry package. - Initial Hessian: For a minimum search, use a model Hessian like

Almlöf[2]. - Convergence Criteria:

- Coordinates: Perform the optimization in redundant internal coordinates.

- Output: The optimized geometry is typically written to a file like

xtbopt.xyzor similar [3].

- Keyword: Use the

Frequency Calculation

- Keyword: Perform a frequency (vibrational) analysis on the optimized geometry using the

Freqkeyword. - Purpose: This calculation computes the second derivatives of the energy (the Hessian matrix) at the minimum. The vibrational frequencies are the square roots of the Hessian's eigenvalues. The absence of imaginary frequencies confirms a true minimum was found [1] [4].

- Keyword: Perform a frequency (vibrational) analysis on the optimized geometry using the

Stiffness Analysis

- The magnitude of the vibrational frequencies is directly related to the stiffness. Higher frequencies indicate stiffer vibrational modes [1].

- The force constant for a specific bond or angle can often be approximated from the computed Hessian.

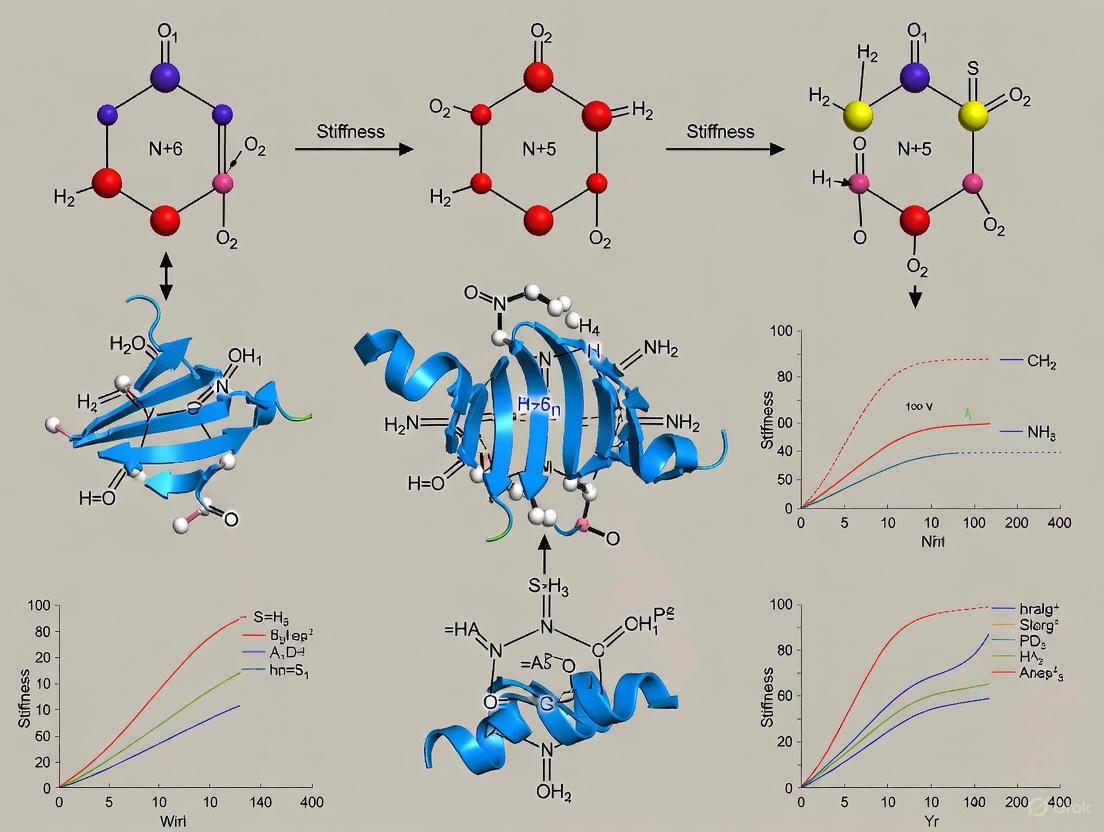

This workflow for determining molecular stiffness through geometry optimization and frequency analysis is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential computational tools and their functions for researching molecular stiffness.

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ORCA [2] | A versatile quantum chemistry package used for geometry optimizations, transition state searches, and frequency calculations via keywords like Opt and Freq. |

| xtb [3] | A software for fast semi-empirical quantum chemical calculations, useful for pre-optimizing geometries or studying large systems with its built-in --opt function. |

| Model Hessians (e.g., Almlöf, Lindh) [2] | An initial guess for the matrix of second energy derivatives, critical for guiding the optimization algorithm, especially in the first steps. |

| Convergence Thresholds (Loose, Normal, Tight) [2] [3] | Pre-defined sets of criteria (for energy, gradient, displacement) that determine when a geometry optimization is considered finished. |

| Redundant Internal Coordinates [2] | A coordinate system based on bonds, angles, and dihedrals that often leads to more efficient geometry optimizations for molecular systems. |

How Stiffness Influences Optimization Pathways and Convergence Behavior

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My geometry optimization is not converging. What should I check first?

Answer: First, verify that your convergence thresholds are appropriate for your system's stiffness. Excessively tight criteria can prevent convergence for "wobbly" or flexible molecules [5]. We recommend a tiered approach:

- For initial scans or less critical properties: Use

Convergence%Quality BasicorNormal[6]. - For final, publication-quality geometries: Use

Convergence%Quality GoodorVeryGood[6]. - For UV-Vis or fluorescence spectra: Standard convergence criteria are often sufficient, as errors from the subsequent spectral calculation (e.g., TD-DFT) typically outweigh minor geometrical inaccuracies [5].

FAQ 2: The optimization converged but found a saddle point (transition state) instead of a minimum. How can I fix this?

Answer: This indicates the optimizer settled in a region with a negative Hessian eigenvalue. Enable automatic restarts to guide the optimization toward a true minimum.

- Enable PES Point Characterization: This calculates the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to check the nature of the stationary point found [6].

- Configure Automatic Restarts: Set

MaxRestartsto a value greater than 0 (e.g., 5). The optimizer will then automatically displace the geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode and restart [6]. - Disable Symmetry: Ensure

UseSymmetry Falseis set, as the symmetry-breaking displacement is only applied when no symmetry operators are present [6].

FAQ 3: My system is large and the optimization is computationally expensive. What strategies can improve efficiency?

Answer: For large systems, a sequential optimization protocol significantly improves efficiency.

- Start with a lower level of theory: Begin optimization with a semi-empirical method or a lower-level DFT with a small basis set.

- Gradually increase precision: Use the geometry from the previous step as the starting point for a higher-level theory calculation [5].

- Consider the optimizer: For very large systems, the L-BFGS optimizer is often a good choice due to its memory efficiency.

FAQ 4: How accurate are the final optimized coordinates from a converged calculation?

Answer:

The convergence threshold for coordinates (Convergence%Step) provides only an order-of-magnitude estimate of coordinate precision. For accurate results, the gradient criterion (Convergence%Gradients) is more reliable. Tightening the gradient criterion will generally yield more accurate geometries than tightening the step criterion [6].

Understanding Convergence Criteria

A geometry optimization is considered converged only when multiple stringent conditions are simultaneously met [6].

Table 1: Standard Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria [6]

| Criterion | Description | Requirement for Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | Difference in total energy between successive steps | < Energy × Number of atoms |

| Maximum Gradient | Largest component of the Cartesian nuclear gradients | < Gradients |

| RMS Gradient | Root-mean-square of the Cartesian nuclear gradients | < 2/3 × Gradients |

| Maximum Step | Largest Cartesian displacement of any nucleus | < Step |

| RMS Step | Root-mean-square of the Cartesian displacements | < 2/3 × Step |

Note: If the maximum and RMS gradients are more than 10 times stricter than the Gradients criterion, the step-based criteria (4 and 5) are ignored [6].

You can set these criteria individually or use predefined quality levels.

Table 2: Predefined Convergence Quality Settings in AMS [6]

| Quality | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | Stress/Atom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide for Stiffness-Dependent Studies

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for optimizing molecular geometries with varying perceived stiffness.

Objective: To obtain a converged, minimum-energy geometry for a molecule, starting from an initial guess structure.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Initial Structure Preparation:

- Generate a reasonable 3D starting structure using a molecular builder. Ensure the structure is chemically plausible to avoid extreme initial forces.

Pre-Optimization Configuration:

- In your input file, set the task to

Task GeometryOptimization[6]. - Enable PES point characterization and automatic restarts to handle saddle points.

- In your input file, set the task to

Execute Tiered Optimization:

- Tier 1 (Coarse): Run an optimization with

Convergence%Quality Basicand a fast, low-level theoretical method (e.g., a semi-empirical method or a small basis set). This quickly refines the geometry. - Tier 2 (Intermediate): Use the output geometry from Tier 1 as the new input. Perform an optimization with

Convergence%Quality Normaland your intermediate method of choice (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*). - Tier 3 (Final): Use the output geometry from Tier 2 as the new input. Perform the final optimization with

Convergence%Quality Goodand your target high-level theory (e.g., B3LYP/6-311G*).

- Tier 1 (Coarse): Run an optimization with

Validate the Result:

- Run a frequency calculation on the final optimized geometry.

- Successful Outcome: All vibrational frequencies are real (positive). This confirms a local minimum has been found [5].

- Problematic Outcome: One or more imaginary (negative) frequencies are found. If

MaxRestartsis configured, the calculation will automatically displace the geometry and restart the optimization. Otherwise, you must manually perturb the geometry and restart.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Parameters for Geometry Optimization

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to Stiffness & Convergence |

|---|---|---|

Convergence Thresholds (Energy, Gradients, Step) |

Define the tolerances for ending the optimization [6]. | Looser thresholds (Basic) help with flexible, "wobbly" molecules. Tighter thresholds (Good) are for rigid, stiff systems near a minimum. |

| PES Point Characterization | Calculates Hessian eigenvalues to determine if a stationary point is a minimum or saddle point [6]. | Critical for diagnosing failed optimizations where a transition state is found instead of a minimum. |

| MaxRestarts | Maximum number of automatic restarts after finding a saddle point [6]. | Automates the process of escaping saddle points, which is common on complex, multi-modal potential energy surfaces. |

| L-BFGS / FIRE Optimizer | Efficient optimization algorithms for large systems with many degrees of freedom. | Preferred for large, complex molecules where computational cost is a primary concern. |

| Tiered Optimization Protocol | A strategy of starting with low-level theory and progressively increasing accuracy [5]. | Dramatically improves computational efficiency and convergence stability for challenging molecules. |

The Critical Link Between Flexibility, Binding Affinity, and Convergence Demands

Frequently Asked Questions

How does molecular flexibility influence binding affinity? Molecular flexibility is a crucial determinant of binding affinity, but its effect is not monotonic. Research shows that binding is strong for both highly rigid and highly flexible molecules. However, for molecules in the middle of the flexibility spectrum, the relationship is complex: small decreases in rigidity can markedly reduce affinity for highly rigid molecules, while precisely the opposite occurs for more flexible molecules, for which increasing flexibility leads to stronger binding [7]. This happens because flexibility affects the balance between the entropic cost and enthalpic gain of binding.

My geometry optimization won't converge. Could molecular flexibility be the cause? Yes. "Wobbly" or flexible molecules can be particularly difficult to optimize [5]. The potential energy surface of flexible molecules has many shallow minima, making it hard for the optimizer to find a true minimum. If an optimization fails, it is often more effective to start with a less accurate method or looser convergence criteria and incrementally increase the precision, rather than immediately using the tightest settings [5].

For spectroscopic calculations like UV-Vis, how critical is a tightly converged geometry? For properties like UV-Vis spectra calculated with Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT), the inherent errors of the TD-DFT method itself are often larger than those introduced by using standard instead of very tight geometry convergence criteria [5]. Therefore, a geometry optimized with standard convergence thresholds is typically sufficient, provided that the structure is a true minimum (all vibrational frequencies are positive) [5].

What is the difference between the 'induced-fit' and 'conformational selection' binding models? The 'induced-fit' model posits that the bound protein conformation forms only after interaction with a binding partner [8]. In contrast, the 'conformational selection' model postulates that the bound conformation pre-exists in an ensemble of protein conformations, and the binding partner selectively stabilizes it [8]. Most real-world binding events involve a combination of both mechanisms [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Geometry Optimization Failing for Flexible Molecules

Symptoms: The optimization calculation hits the maximum number of iterations without converging, or it oscillates between several structures. Solutions:

- Use a Stepped Optimization Protocol: Begin with a faster, less accurate method (e.g., a semi-empirical method or a small basis set) to get a rough geometry. Then, use this pre-optimized structure as the starting point for your target, more accurate method [5].

- Loosen Convergence Criteria Initially: Start with

Convergence%Quality BasicorNormalbefore moving toGoodorVeryGoodfor the final optimization [6]. - Enable Automatic Restarts: If your software supports it, use the PES point characterization and automatic restart feature. This can help if the optimization converges to a saddle point (transition state) instead of a minimum [6].

- Verify the Minimum: After a seemingly successful optimization, always calculate the vibrational frequencies to ensure all are positive, confirming you have found a local minimum and not a saddle point [5].

Problem: Inaccurate Prediction of Binding Affinity

Symptoms: Docking or binding free energy calculations yield poor correlation with experimental data. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Neglecting Protein Flexibility. Treating the receptor as completely static (rigid docking) ignores the thermodynamic consequences of molecular motion, which can generate large errors in binding entropy, enthalpy, and free energy [7] [8].

- Solution: Use methods that account for flexibility, such as molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, conformational ensemble docking, or normal mode analysis (NMA) [8].

- Cause: Insufficient Sampling. The conformational space of the flexible molecule or complex may not be adequately explored.

- Solution: For MD, use enhanced sampling techniques like temperature replica exchange MD (T-REMD) or Hamiltonian replica exchange MD (H-REMD) to achieve better convergence of the free energy landscape [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Methodology: Simulating the Role of Flexibility in Binding

This protocol is based on the coarse-grained molecular dynamics approach used to isolate the effect of flexibility [7].

- System Setup:

- Model Molecules: Use linear chains of coarse-grained beads. The minimum energy structure is set to be fully extended.

- Control Flexibility: Apply a harmonic bending potential, ( U = k{\text{bend}} (\theta - \theta0)^2 ), at each angle ( \theta ). The bending force constant ( k{\text{bend}} ) controls flexibility, with a range from ~0.3 (very flexible) to 1000 (nearly rigid). The equilibrium angle ( \theta0 ) is set to 180° for an extended chain.

- Interactions: Non-bonded bead-bead interactions are modeled with a generic Lennard-Jones potential (e.g., σ = 0.85, ε = 1.0), identical for all chain pairs to ensure differences arise purely from flexibility.

- Simulation Details:

- Software: Simulations can be performed using LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator).

- Ensemble: Canonical (NVT) ensemble using a Langevin thermostat for temperature control and implicit solvent.

- Analysis:

- Binding Constant: Calculate ( Ka = V \cdot t{\text{bound}} / t{\text{unbound}} ) by monitoring the fraction of simulation time the chains spend in a bound state (defined by a threshold number of inter-chain contacts).

- Energetics: Determine the free energy ( \Delta G = -RT \ln Ka ), enthalpy ( \Delta H ) as the energy difference between bound and unbound states, and entropy from ( -T\Delta S = \Delta G - \Delta H ).

Quantitative Data on Flexibility and Affinity

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from simulations of chain-like molecules with varying flexibility [7].

| Bending Force Constant (( k_{\text{bend}} )) | Relative Flexibility | Impact on Binding Affinity (( K_a )) | Energetic Driving Force |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~1000 | Nearly Rigid | Strong binding | Dominated by favorable enthalpy ((\Delta H)) |

| ~274 | Moderately Rigid | Affinity decreases with small increases in flexibility | Enthalpy decreases, entropy cannot compensate |

| ~5 | Moderately Flexible | Affinity increases with flexibility | Entropy becomes increasingly favorable |

| ~0.3 | Very Flexible | Strong binding | Favorable entropy and ability to form multiple contacts |

Geometry Optimization Convergence Criteria

The following table outlines standard convergence thresholds for geometry optimizations, which can be tightened or loosened depending on the flexibility of the system and the required accuracy [6].

| Convergence Criterion | Normal Quality |

Good Quality |

VeryGood Quality |

Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (( \times ) number of atoms) | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁷ | Hartree |

| Gradients | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.00001 | Hartree/Angstrom |

| Step | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | Angstrom |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Coarse-Grained (CG) Bead Model | Minimalist representation of molecular fragments; allows systematic study of flexibility by reducing computational cost and isolating key variables [7]. |

| Harmonic Bending Potential | A tunable parameter in simulations (( U = k{\text{bend}} (\theta - \theta0)^2 )) that directly controls the intrinsic flexibility of the model molecule [7]. |

| LAMMPS (Molecular Dynamics) | Open-source software for performing molecular dynamics simulations, used to simulate the binding interactions of flexible molecules over time [7]. |

| Langevin Thermostat | Provides temperature control and implicit treatment of solvent friction and random collisions in MD simulations [7]. |

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Advanced sampling technique that helps a simulation escape local energy minima, crucial for sampling the conformational space of flexible molecules [8]. |

Visualizing Key Concepts

Binding Affinity Relationship to Flexibility

Geometry Optimization Convergence

In computational chemistry and materials science, geometry optimization is a fundamental process. The goal is to find a stable molecular configuration where the net forces acting on all atoms are effectively zero, representing a local or global energy minimum. Determining when this process is complete relies on convergence criteria—numerical thresholds for energy changes, gradients (forces), and atomic displacements. Setting these thresholds is a critical balance between computational cost and result accuracy, particularly in stiffness research where precise energy landscapes are essential.

The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address the practical challenges researchers face when working with these criteria, framed within the context of molecular stiffness research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the default convergence criteria typically checked during a geometry optimization? Most computational software packages monitor three primary quantities by default. The specific active criteria often depend on the problem's degrees of freedom (e.g., translations, rotations, vibrations) [10]. The standard criteria are:

- Energy Change: The difference in total energy between successive optimization steps.

- Gradient (Force): The root-mean-square (RMS) or maximum value of the forces on the atoms. The force is the negative derivative of the energy with respect to atomic coordinates (-dE/dR).

- Displacement: The RMS or maximum change in atomic coordinates between steps.

Q2: My optimization is not converging. How do I determine if the problem is with the wavefunction or the geometry? This is a fundamental diagnostic question [11].

- Wavefunction (SCF) Convergence Issues: These occur during the single-point energy calculation at a fixed geometry. The self-consistent field procedure fails to find a stable electronic state.

- Geometry Optimization Convergence Issues: These occur when the algorithm cannot find a geometry where the forces are below the specified threshold, even if each single-point energy calculation completed successfully. The optimization may oscillate between structures or fail to lower the energy significantly.

Q3: Why should I avoid relying solely on Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) plots to judge convergence? Although intuitive, using RMSD plots is highly subjective and unreliable. A scientific survey demonstrated that when different scientists were shown the same RMSD plots, there was no mutual consensus on the point of equilibrium [12]. Their decisions were significantly biased by factors like the color and Y-axis scaling of the plot. A more robust approach combines quantitative convergence criteria with analysis of other properties.

Q4: What is the concept of "partial equilibrium," and why is it relevant to biomolecular simulations? A system can be in partial equilibrium when some properties have reached their converged values, while others have not [13]. This is common in complex biomolecules. For instance, average bond lengths or local side-chain angles (which depend on high-probability conformational regions) may stabilize quickly. In contrast, properties like the free energy or transition rates to rare conformations (which depend on full exploration of the conformational space) may require much longer simulation times to converge [13]. This is crucial for stiffness research, as different mechanical properties may converge at different rates.

Q5: How can I adjust convergence thresholds if my optimization is too slow or fails? Most software allows you to manually loosen or tighten the convergence criteria via keywords [11].

- To combat slow convergence, you can increase the tolerance (e.g.,

GRADIENTTOLERANCE=0.001instead of the default0.0001). This tells the algorithm to stop when the forces are smaller, which may be acceptable for preliminary scans. - If an optimization fails due to an excessive number of steps, you can increase the cycle limit (e.g.,

GEOMETRYCYCLES=500). However, first examine the molecule's geometry to ensure it is not undergoing an unexpected chemical reaction.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Geometry Optimization Failures

Problem: A geometry optimization job terminates without reaching the defined convergence criteria.

Diagnostic Workflow:

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Geometry Optimization Failures

Solutions:

- Poor Starting Geometry:

Poor Quality Hessian: The Hessian (matrix of second energy derivatives) guides the optimization direction. A bad guess can lead to slow or failed convergence.

Symmetry Problems: The default use of symmetry can sometimes interfere.

- Action: Use the

IGNORESYMMETRYorNOGEOMSYMMETRYkeyword to disable symmetry handling [11]. Physically breaking the molecular symmetry slightly can also help.

- Action: Use the

Optimization Ran Out of Cycles:

- Action: Use the

OPTCYCLEorGEOMETRYCYCLESkeyword to increase the maximum number of steps [11]. Before resubmitting, verify that the geometry is evolving as expected.

- Action: Use the

Guide 2: Ensuring Meaningful Convergence for Stiffness Research

Problem: The optimization met the technical criteria, but the resulting structure or properties (like stiffness) do not appear physically meaningful or reproducible.

Methodology:

Diagram Title: Protocol for Valid Convergence

Protocol:

- Go Beyond Technical Criteria: Do not rely solely on the software's "job completed" message. Visually inspect the convergence plots for energy, gradient, and displacement to ensure they have stabilized to a flat plateau [13].

- Monitor Relevant Properties: For stiffness research, define key structural properties a priori (e.g., hinge region dihedral angles, core residue distances). Plot these properties over the course of the simulation to ensure they have also converged [13].

- Check for Partial Equilibrium: Understand that your system may be in partial equilibrium. While the overall energy may be stable, the specific conformational mode governing molecular stiffness might require a longer simulation time to fully sample [13].

- Validate with Extended Sampling: After optimization, run a longer molecular dynamics simulation starting from the optimized geometry. Analyze the fluctuation of key properties to confirm they fluctuate around a stable average, indicating true convergence [13].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Standard Convergence Criteria and Adjustable Parameters

| Quantity | Common Default Threshold | Keyword Example (Spartan) | Purpose in Optimization | Impact of Loosening Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change | ~10-5 to 10-6 Hartree | ENERGYTOLERANCE (or TOLE) |

Determines if total energy is stable. | Faster termination, potentially less accurate final energy. |

| Gradient (RMS Force) | ~10-3 to 10-4 Hartree/Bohr | GRADIENTTOLERANCE (or TOLG) |

Primary indicator of a stationary point (zero force). | Major speed increase, but risk of stopping before true minimum. |

| Displacement (RMS Step) | ~10-3 to 10-4 Bohr | DISPLACEMENTTOLERANCE (or TOLD) |

Measures how much atoms move between steps. | Prevents excessive steps when energy and gradients are slow to change. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments

| Item / "Reagent" | Function in Experiment | Notes for Application |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Hessian | Provides an initial guess for the second derivative of the energy, guiding the optimization direction. | A poor Hessian is a common failure point. Use HESS=UNIT for stability or calculate at a lower theory level for speed and accuracy [11]. |

| Symmetry Control | Speeds up calculation by leveraging molecular symmetry but can cause convergence issues if symmetry is incorrectly assigned or meta-stable. | Use IGNORESYMMETRY to turn off if problems arise. Spartan's symmetry detection is numerically very precise [11]. |

| Internal Coordinates | A coordinate system (vs. Cartesian) that accounts for molecular bonding, often speeding up convergence for organic molecules. | Can cause issues in high-coordination systems; disable with NOGEOMSYMMETRY [11]. |

| Lower Theory/Basis Set | A simpler computational method (e.g., Semi-Empirical, HF/3-21G*) used to generate a better starting geometry for a high-level calculation. | A core strategy for complex systems: "start simple, then build up" [11]. |

| Convergence Keywords | Directly modify the thresholds (TOLG, TOLD) and cycle limits (OPTCYCLE) that control the optimization termination. |

Essential for troubleshooting. Loosen to overcome noise; tighten for high-precision results [11]. |

Setting Convergence Thresholds: A Practical Guide for Different Software Platforms

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What does the "geometry optimization did not converge" error mean and how can I fix it?

This error indicates that the xtb optimizer failed to find a minimum energy structure within the allowed number of cycles or encountered a problem in a single-point energy calculation during the optimization process [14]. The underlying cause is often a failure of the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure to converge [14]. To resolve this:

- Increase SCF iterations: Use a simpler GFN method (e.g., GFN0-xTB) to generate a better initial guess for the wavefunction, then restart the optimization with GFN2-xTB [15].

- Adjust electronic temperature: Use the

--etempflag to temporarily increase the electronic temperature, which can help SCF convergence, and then restart the calculation at normal temperature [15]. - Check geometry: Ensure your initial molecular geometry is reasonable, as problematic structures can prevent convergence [14].

2. My optimization converged but has small imaginary frequencies. What should I do? Small imaginary frequencies (e.g., below ~15 cm⁻¹) can be artifacts and are often straightforward to eliminate.

xtbhas an automatic feature to handle this. When an imaginary frequency is detected during a frequency calculation (--ohess), the program writes a distorted geometry file (xtbhess.coord) [15].- Simply use this distorted structure as a new starting point for another optimization and frequency calculation. This process usually requires only a few steps to remove the artificial imaginary mode [15].

3. How do I choose the right convergence level for my project? The choice depends on your specific accuracy requirements and computational resources.

- For preliminary screening or large systems: Use

looseornormalfor faster results [3]. - For final production geometries: Use

tightto ensure high accuracy for subsequent property calculations [3] [16]. - For benchmarking or sensitive properties:

vtightorextrememay be necessary, but these are computationally demanding and often represent a development feature more than a requirement for most applications [15].

Optimization Convergence Levels

The xtb program provides a built-in geometry optimizer, the approximate normal coordinate rational function optimizer (ANCopt), which is activated with the --opt [level] flag [3]. The following table summarizes the predefined convergence levels, which control the strictness of the optimization [3] [15].

| Level | Energy Convergence (Eₕ) | Gradient Convergence (Eₕ/Å) | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| crude | 5 × 10⁻⁴ | 1 × 10⁻² | 3.00 |

| sloppy | 1 × 10⁻⁴ | 6 × 10⁻³ | 3.00 |

| loose | 5 × 10⁻⁵ | 4 × 10⁻³ | 2.00 |

| lax | 2 × 10⁻⁵ | 2 × 10⁻³ | 2.00 |

| normal | 5 × 10⁻⁶ | 1 × 10⁻³ | 1.00 |

| tight | 1 × 10⁻⁶ | 8 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.20 |

| vtight | 1 × 10⁻⁷ | 2 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.05 |

| extreme | 5 × 10⁻⁸ | 5 × 10⁻⁵ | 0.01 |

- Energy Convergence: The threshold for the change in total energy between optimization cycles [3].

- Gradient Convergence: The threshold for the norm of the energy gradient (forces), which should be close to zero at a minimum [3].

- Accuracy: This value is automatically passed to the single-point calculations, tightening integral cutoffs and SCF convergence criteria to match the geometry optimization thresholds [3].

Experimental Protocol: GFN Method Benchmarking for Molecular Stiffness

This protocol outlines a methodology for benchmarking GFN methods against higher-level theories like Density Functional Theory (DFT) to assess their reliability for predicting molecular geometries, a crucial step in molecular stiffness research [16].

1. Dataset Curation

- Select a representative set of molecules relevant to your research domain. For organic semiconductors, this could involve filtering databases like QM9 based on HOMO-LUMO gaps (< 3 eV) to mimic semiconductor behavior, or using specialized datasets like the Harvard Clean Energy Project (CEP) database [16].

2. Computational Workflow

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize all molecular structures using various GFN methods (GFN0-xTB, GFN1-xTB, GFN2-xTB, GFN-FF) and a reference method (e.g., DFT with a specific functional and basis set).

- Frequency Analysis: Perform a frequency calculation on the optimized geometry to confirm it is a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies) and to obtain thermochemical corrections.

- Property Calculation: Calculate key properties from the optimized geometries for comparison.

3. Benchmarking Metrics Compare the GFN-optimized structures and properties against the reference DFT data using these metrics:

- Heavy-atom Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the overall geometric similarity [16].

- Bond Lengths and Angles: Quantifies deviations in specific structural parameters [16].

- Equilibrium Rotational Constants: A sensitive measure of the overall molecular structure [16].

- HOMO-LUMO Gap: Assesses the accuracy of electronic properties derived from the geometry [16].

- Computational CPU Time: Evaluates the efficiency of each method [16].

The diagram below illustrates the key decision points in a geometry optimization workflow, from method selection to verifying a successful result.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and concepts used in xtb geometry optimizations for molecular stiffness research.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| GFN2-xTB | A semi-empirical quantum mechanical method offering a favorable balance of accuracy and speed; ideal for geometry optimizations of medium-to-large systems in high-throughput screenings [16] [17]. |

| GFN1-xTB | An earlier GFN parametrization; demonstrates high structural fidelity in benchmarks, sometimes outperforming GFN2-xTB for specific organic systems [16]. |

| GFN0-xTB | A non-self-consistent, minimal basis semi-empirical method; useful as a robust initial optimizer for systems where GFN2-xTB fails to converge, providing a good starting structure for subsequent refinements [15] [16]. |

| GFN-FF | A fully automated force field; provides the fastest geometry optimizations and is particularly suited for very large systems or as part of multi-level screening pipelines where computational cost is a primary concern [16] [17]. |

| Convergence Thresholds | The user-defined criteria (energy and gradient) that determine when an optimization is considered complete; tighter thresholds (e.g., tight) are crucial for obtaining highly accurate geometries for property calculation [3] [6]. |

| ANCopt | The Approximate Normal Coordinate Rational Function Optimizer built into xtb; a robust algorithm designed for efficient geometry optimizations using internal coordinates and a model Hessian [3]. |

Configuring the GeometryOptimization Block in AMS for Stiff and Flexible Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I choose the right convergence criteria for my system?

The Convergence%Quality keyword offers a quick way to set thresholds. The default Normal settings are reasonable for many applications, but you may need to adjust them based on the stiffness of your molecule [6].

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | StressEnergyPerAtom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal (Default) | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

Table: Predefined convergence criteria sets in AMS, selected via the Convergence%Quality keyword [6].

My geometry optimization does not converge. What should I check first?

First, examine the energy changes over the last ten iterations [18]. A steady energy decrease suggests you should simply increase MaxIterations. If the energy oscillates, the gradients may be inaccurate, and you should increase the numerical quality or tighten the SCF convergence [18].

What can I do if my optimization converges to a saddle point instead of a minimum?

You can enable automatic restarts. Use the PESPointCharacter property in the Properties block to characterize the stationary point, and set MaxRestarts to a value >0 in the GeometryOptimization block. This will automatically displace the geometry along the imaginary mode and restart the optimization [6].

How can I optimize the lattice vectors of a periodic system?

Set OptimizeLattice Yes in the GeometryOptimization block. This is supported with the Quasi-Newton, FIRE, and L-BFGS optimizers [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Geometry Optimization Fails to Converge

Diagnosis: Check the optimization output. If the energy oscillates around a value and the gradient stops improving, the calculation setup may be the issue [18].

Solutions:

- Increase computational accuracy: The success of optimization depends on accurate forces [18].

- Check for small HOMO-LUMO gap: A small gap can indicate a changing electronic structure between steps. Verify you have the correct ground state and consider using an

OCCUPATIONSblock to freeze electrons per symmetry [18]. - Change optimization coordinates: If you are using Cartesian coordinates, try switching to delocalized internal coordinates, which often converge faster [18].

Example input with stricter accuracy settings [18]:

Problem: Optimization is Too Slow for a Large, Flexible Molecule

Diagnosis: Flexible systems with many degrees of freedom require many small steps. The default settings may be too strict for preliminary screening.

Solutions:

- Use looser convergence criteria: Start with

Convergence%Quality BasicorVeryBasicfor an initial, faster optimization. You can later restart the optimization from the resulting geometry with tighter criteria [6]. - Automate accuracy settings: Use the

EngineAutomationsblock to start with loose SCF and optimization settings, which automatically tighten as the geometry improves. This saves time in the initial stages [19].

Example automation for a flexible system [19]:

Problem: Optimized Bond Lengths Are Unrealistically Short

Diagnosis: This is often a basis set problem, particularly when using the Pauli relativistic method, or can be caused by large frozen cores overlapping [18].

Solutions:

- Switch relativistic method: Abandon the Pauli method and use the ZORA approach for heavy elements [18].

- Adjust the frozen core: If you must use the Pauli formalism, apply larger frozen cores. If you suspect your frozen cores are already too large, use smaller ones, but be wary of using the Pauli formalism in this case [18].

Problem: SCF Convergence Issues During Geometry Optimization

Diagnosis: An unconverged SCF leads to noisy gradients, preventing geometry convergence. Some systems (e.g., metallic slabs) are inherently harder to converge [19].

Solutions:

- Use conservative SCF settings: Decrease the SCF mixing and/or use a more conservative DIIS strategy [19].

- Employ a finite electronic temperature: This can help initial convergence. Use

EngineAutomationsto start with a higher temperature and reduce it as the optimization progresses [19]. - Try a different SCF algorithm: The MultiSecant method can be a robust alternative to DIIS [19].

Example SCF configuration for difficult cases [19]:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Convergence Quality Presets | Provides balanced sets of thresholds (Energy, Gradients, Step) for different optimization goals, from quick scans to high-precision work [6]. |

| NumericalQuality Keyword | Controls the accuracy of numerical integration. Crucial for achieving accurate gradients, especially for systems with heavy elements [18]. |

| PES Point Characterization | Determines the nature (minimum, transition state) of the located stationary point, enabling automatic recovery from saddle points [6]. |

| EngineAutomations Block | Dynamically adjusts key parameters (e.g., electronic temperature, SCF cycles) during the optimization, balancing efficiency and final accuracy [19]. |

| Initial Model Hessian | Provides a reasonable starting estimate for the second derivatives, significantly improving convergence speed compared to a unit matrix [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization for Stiff Systems

This protocol is designed for optimizing stiff molecular systems where high accuracy is required.

- Initial Setup: Begin with your initial molecular geometry in the

Systemblock and selectTask GeometryOptimization. - Configure Convergence: In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setConvergence%QualitytoGoodorVeryGoodto ensure tight thresholds [6]. - Ensure Gradient Accuracy: In the engine-specific block (e.g.,

BAND,ADF), setNumericalQuality Goodand consider tightening the SCF convergence criterion to1e-7or1e-8to provide low-noise gradients [18]. - Characterize the Result: In the

Propertiesblock, setPESPointCharacter Trueto confirm the optimization has found a true minimum and not a saddle point [6]. - Run and Analyze: Execute the calculation and check the output file to verify that all convergence criteria were met and the PES point is a minimum.

Workflow for Geometry Optimization Configuration

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for configuring the GeometryOptimization block based on your system's characteristics and research goals.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I choose the right optimizer for my molecular system? The optimal choice depends on your primary goal. For general-purpose use and robust performance, L-BFGS is often recommended and is considered the best general-purpose quasi-Newton method in some packages [20] [21]. If you are optimizing on a potentially noisy potential energy surface, FIRE may be more tolerant [22]. For the fastest convergence to a minimum when using internal coordinates is feasible, Sella (internal) shows exceptional speed [22].

My optimization is not converging. What should I check first?

First, verify that your convergence criteria are appropriate for your system. Excessively tight criteria may require an impractical number of steps [6]. Ensure that the maximum force component (fmax) is set to a reasonable value (e.g., 0.01 eV/Å) [22] [21]. Second, confirm that your calculator provides gradients that are accurate and noise-free enough for the chosen optimizer, as this is critical for quasi-Newton methods [6].

The optimization finished, but my molecule has imaginary frequencies. What went wrong? This indicates that the optimization converged to a saddle point (transition state) rather than a local minimum [6]. Some optimizers are more prone to this than others. You can address this by:

- Using an optimizer with better performance for finding minima, such as Sella with internal coordinates or L-BFGS, which tend to find more true minima [22].

- Enabling automatic restarts in your optimization software (if available), which can displace the geometry along the imaginary mode and restart the optimization [6].

Can I use L-BFGS as a steepest-descent optimizer?

Yes. If you set the memory_size parameter to zero, the L-BFGS optimizer will behave like a steepest descent optimizer [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Convergence or Slow Performance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization exceeds step limit [22] | Convergence criteria too tight [6] | Loosen fmax or other thresholds [6]. |

| Noisy potential energy surface | Switch to a more noise-tolerant optimizer like FIRE [22]. | |

| Slow progress in initial steps | Poor initial Hessian guess | Use a better initial guess or replay a previous trajectory to build the Hessian [21]. |

| L-BFGS stops at a fixed iteration count | Default iteration limit reached [23] | Increase the maxiter parameter. |

Convergence to Incorrect Stationary Points

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Imaginary frequencies in final structure | Converged to saddle point [6] | Use Sella (internal) or L-BFGS; enable automatic restarts [22] [6]. |

| High number of imaginary frequencies (e.g., with FIRE) | Optimizer less effective at finding true minima [22] | Switch to L-BFGS or Sella [22]. |

| Inaccurate final geometry | Loose convergence on gradients [6] | Tighten the gradient convergence criterion (Gradients or fmax) [6]. |

Experimental Benchmarking Data

The following data, adapted from a benchmark study on 25 drug-like molecules, compares the performance of various optimizers when paired with different Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) and a semiempirical method (GFN2-xTB). Convergence was determined by a maximum force threshold of 0.01 eV/Å [22].

Table 1: Number of Successful Optimizations (out of 25)

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 22 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 24 |

| ASE/FIRE | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 15 |

| Sella | 15 | 24 | 25 | 15 | 25 |

| Sella (internal) | 20 | 25 | 25 | 22 | 25 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 8 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 9 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 20 | 14 | 1 | 25 |

Table 2: Average Number of Steps for Successful Optimizations

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 108.8 | 99.9 | 1.2 | 112.2 | 120.0 |

| ASE/FIRE | 109.4 | 105.0 | 1.5 | 112.6 | 159.3 |

| Sella | 73.1 | 106.5 | 12.9 | 87.1 | 108.0 |

| Sella (internal) | 23.3 | 14.9 | 1.2 | 16.0 | 13.8 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 182.1 | 158.7 | 13.6 | 175.9 | 195.6 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 11.0 | 114.1 | 49.7 | 13.0 | 103.5 |

Table 3: Number of True Local Minima Found (No Imaginary Frequencies)

| Optimizer | OrbMol | OMol25 eSEN | AIMNet2 | Egret-1 | GFN2-xTB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS | 16 | 16 | 21 | 18 | 20 |

| ASE/FIRE | 15 | 14 | 21 | 11 | 12 |

| Sella | 11 | 17 | 21 | 8 | 17 |

| Sella (internal) | 15 | 24 | 21 | 17 | 23 |

| geomeTRIC (cart) | 6 | 8 | 22 | 5 | 7 |

| geomeTRIC (tric) | 1 | 17 | 13 | 1 | 23 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

1. Benchmarking Optimizer Performance

- Objective: Systematically evaluate the efficiency and robustness of different geometry optimizers on a set of drug-like molecules.

- System Setup:

- Optimization Execution:

- Post-Optimization Analysis:

2. Protocol for a Standard Geometry Optimization

- Initialization:

- Define the initial atomic structure and set up the calculator (e.g., LCAO Calculator in QuantumATK, EMT in ASE, or an NNP) [20] [21].

- Choose an optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS) and set its parameters (e.g.,

memory_size=20,finite_difference=0.01*Angstrom) [20]. - Set convergence thresholds. A common choice is to base convergence solely on the maximum force

fmax[22] [21]. For more control, you can set multiple criteria including energy change, gradients, and step size [6].

- Execution:

- Validation:

- Always check the output to confirm that convergence was achieved and not just the step limit exceeded.

- Perform a frequency calculation to confirm the nature of the stationary point found [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| L-BFGS Optimizer | A quasi-Newton optimizer that approximates the Hessian to achieve superlinear convergence; recommended for general use [20] [21]. |

| FIRE Optimizer | A first-order, dynamics-based optimizer known for fast initial relaxation and tolerance to noisy potential energy surfaces [22] [21]. |

| Sella Optimizer | An optimizer using internal coordinates and a rational function approach, excellent for efficiently finding local minima, especially in internal coordinate mode [22]. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer | An optimizer implementing advanced internal coordinates (TRIC), often requiring careful configuration of multiple convergence criteria [22]. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) | A machine-learning model that provides DFT-level potential energy surfaces at a fraction of the computational cost for running optimizations [22]. |

| Vibrational Frequency Analysis | A required post-optimization procedure to verify that the optimized structure is a minimum (all real frequencies) and not a saddle point [22] [6]. |

Workflow Visualization

Optimizer Selection and Validation Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Geometry Optimization Convergence

FAQ: My optimization fails with a "Back transformation failed" error. What should I do?

Problem: This error indicates a failure in converting between internal and Cartesian coordinates, often accompanied by a "Cartesian Step size too large" message. This is frequent in flexible molecules with constrained dihedrals [24].

Solutions:

- Stabilize the Optimization: Use settings like

ENSURE_BT_CONVERGENCE TrueandDYNAMIC_LEVEL 1.0to increase the robustness of the coordinate transformation process [24]. - Adjust Coordinate System: Switch the optimization coordinate system. While redundant internal coordinates are often recommended, trying Cartesian coordinates (

coordsys cartesian) can sometimes resolve convergence issues in difficult cases [2]. - Review Constraints: For very flexible molecules, an excessive number of frozen dihedral angles can sometimes lead to this error. Check if all applied constraints are necessary.

FAQ: How do I select the right convergence thresholds for my system?

Problem: Using default convergence criteria may be inefficient (too loose) or computationally expensive (too tight). The optimal settings depend on molecular stiffness and research goals [6].

Solutions:

- Follow Presets: Start with standard convergence profiles.

!Opt(Normal) is a good default, while!TightOptis for high-precision results.!LooseOptcan be used for initial scans [2]. - Tune for Stiffness: For rigid, drug-like molecules, standard or tight thresholds are appropriate. For flexible chains, looser thresholds may be needed initially, with tightening in later stages [6].

- Prioritize Gradients: For an accurate final geometry, tightening the gradient convergence criterion (

TolMaxG,TolRMSG) is more reliable than tightening the step size criterion [6].

FAQ: My flexible molecule optimization is slow. How can I speed it up?

Problem: Flexible molecules with many rotatable bonds have a complex energy landscape, causing optimizations to require many steps or get stuck.

Solutions:

- Improve the Initial Hessian: A better initial guess for the Hessian (force constant matrix) significantly speeds up convergence. For the first optimization, use a model Hessian like

Almloef(default in ORCA) orSchlegelinstead of a unit matrix [2]. - Use a Multi-Step Protocol:

- Perform an initial, fast optimization with a low-level method (e.g., semi-empirical like AM1) or a loose convergence threshold to generate a good Hessian.

- Use the resulting Hessian as the starting point (

InHess Read) for a high-level optimization [2].

- Employ Specialized Optimizers: For very large systems, use optimizers designed for efficiency, such as the L-BFGS algorithm [2].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Comparative Optimization Protocol

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for comparing the optimization behavior of rigid and flexible molecules.

1. System Preparation:

- Rigid Drug-like Molecule: Select a fragment-like molecule adhering to the "Rule of Three" (MW ≤ 300, HBD ≤ 3, HBA ≤ 3, cLogP ≤ 3) for efficient binding [25].

- Flexible Chain Fragment: Select a linear molecule with multiple rotatable bonds (e.g., >5).

2. Computational Setup:

- Method and Basis Set: Use a consistent level of theory (e.g.,

! B3LYP def2-SVP Optin ORCA). - Initial Geometry: Generate a reasonable 3D structure for both molecules.

3. Optimization Execution:

- Run geometry optimizations for both molecules using the same convergence criteria (e.g., the default

!Optsettings). - Monitor the number of optimization cycles, total computation time, and whether convergence is achieved.

4. Analysis:

- Compare the number of steps and time to convergence.

- Analyze the final geometries and energy changes during the optimization process.

Optimization Thresholds and Convergence Criteria

The tables below summarize standard convergence criteria across computational packages, providing a reference for designing experiments.

Table 1: Standard geometry optimization convergence thresholds in ORCA (in atomic units) [2].

| Criterion | Description | LooseOpt | Normal (!Opt) | TightOpt | VeryTightOpt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TolE | Max energy change | 3e-5 | 5e-6 | 1e-6 | 2e-7 |

| TolMaxG | Max gradient component | 2e-3 | 3e-4 | 1e-4 | 3e-5 |

| TolRMSG | RMS gradient | 5e-4 | 1e-4 | 3e-5 | 8e-6 |

| TolMaxD | Max displacement | 1e-2 | 4e-3 | 1e-3 | 2e-4 |

| TolRMSD | RMS displacement | 7e-3 | 2e-3 | 6e-4 | 1e-4 |

Table 2: Convergence quality settings in the AMS package [6].

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha/atom) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Geometry Optimization Decision Workflow

This diagram outlines the key decision points during a geometry optimization, including the critical check for unintended transition states and the subsequent restart procedure [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential computational tools and methods for geometry optimization studies.

| Item / Method | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| BFGS / L-BFGS | Quasi-Newton optimization algorithms that efficiently update an approximate Hessian. | L-BFGS is recommended for very large systems due to its memory efficiency [2]. |

| Redundant Internal Coordinates | A coordinate system based on bonds, angles, and dihedrals. | Generally recommended for faster convergence in most molecular systems [2] [26]. |

| Model Hessians (Almloef, Schlegel) | Empirical estimates of the initial force constant matrix. | Crucial for fast convergence; Almloef is the default for minimizations in ORCA [2]. |

| Nudged-Elastic Band (NEB) | A method for finding the minimum energy path and transition states. | Essential for locating complicated transition states between reactant and product structures [2]. |

| ModRedundant | A method to define frozen or scanned coordinates in the input. | Used to apply constraints, for example, to fix dihedral angles during an optimization [26] [24]. |

| PES Point Characterization | Calculation of the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to determine the nature of a stationary point. | Used to identify if an optimization converged to a minimum or a saddle point, triggering automatic restarts [6]. |

The Role of Internal vs. Cartesian Coordinates in Efficient Convergence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between internal and Cartesian coordinates in geometry optimization?

Cartesian coordinates define the position of each atom in a molecule using its absolute (x, y, z) coordinates in space. In contrast, internal coordinates describe the molecular structure based on the relative positions of atoms, using bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles. Internal coordinates directly represent the natural vibrational modes of a molecule, which often leads to more efficient convergence on the potential energy surface, especially for systems with complex bonding patterns [22].

2. When should I prioritize using internal coordinates over Cartesian coordinates?

Internal coordinates are generally preferred for optimizing isolated molecules, particularly when significant structural changes involving bond stretching or angle bending are expected. They are highly effective for avoiding convergence issues related to rotational and translational degrees of freedom. Cartesian coordinates may be more suitable for periodic systems (e.g., crystals), complex constraints, or when using certain force fields where the coordinate transformation is computationally expensive [22].

3. A key benchmark study reported that "Sella (internal)" successfully optimized 20 out of 25 drug-like molecules, while "geomeTRIC (tric)" only optimized 1 for the OrbMol neural network potential. Why such a large discrepancy despite both using internal coordinates?

This significant performance difference, as observed in a 2025 benchmark, highlights that the type of internal coordinate system is critical [22]. The "Sella" optimizer uses a standard internal coordinate system, while "geomeTRIC (tric)" employs a specific scheme called "translation–rotation internal coordinates" (TRIC). The implementation details, such as how the coordinate system handles molecular translations and rotations, can drastically affect performance with different potential energy surfaces. This suggests that researchers should test multiple optimizers tailored to their specific computational method (e.g., the NNP or quantum chemistry method) rather than assuming all internal coordinate methods are equivalent [22].

4. My geometry optimization is not converging. How can I adjust my convergence thresholds?

Most computational packages allow you to adjust convergence criteria. Tightening these thresholds leads to a more precise optimization but requires more computational steps. The Convergence%Quality setting in the AMS package, for example, offers a quick way to change these thresholds [6]. The following table summarizes standard convergence criteria for different quality levels:

Table: Standard Geometry Convergence Thresholds (AMS Package) [6]

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | Stress Energy Per Atom (Ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VeryBasic | 10⁻³ | 10⁻¹ | 1 | 5×10⁻² |

| Basic | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻² | 0.1 | 5×10⁻³ |

| Normal | 10⁻⁵ | 10⁻³ | 0.01 | 5×10⁻⁴ |

| Good | 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ | 0.001 | 5×10⁻⁵ |

| VeryGood | 10⁻⁷ | 10⁻⁵ | 0.0001 | 5×10⁻⁶ |

5. What are the key performance differences between optimizers using internal and Cartesian coordinates?

The choice of optimizer and coordinate system significantly impacts the efficiency and success rate of geometry optimizations. Benchmark studies on drug-like molecules provide quantitative comparisons. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different optimizer and coordinate system combinations when used with Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) and a traditional GFN2-xTB method.

Table: Optimizer Performance Comparison (25 Drug-like Molecules Benchmark) [22]

| Optimizer / Coordinate System | Average Successful Optimizations (out of 25) | Average Steps for Convergence | Average Minima Found (out of 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASE/L-BFGS (Cartesian) | 22 - 25 | ~100 - 120 | 16 - 21 |

| ASE/FIRE (Cartesian) | 15 - 25 | ~105 - 160 | 11 - 21 |

| Sella (Internal) | 20 - 25 | ~14 - 23 | 15 - 24 |

| geomeTRIC (Cartesian) | 7 - 25 | ~160 - 195 | 5 - 22 |

| geomeTRIC (TRIC) | 1 - 25 | ~11 - 115 | 1 - 23 |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow or Non-Converging Optimization

Symptoms:

- The optimization exceeds the maximum number of steps (e.g., 250) without meeting convergence criteria [22].

- The energy, gradients, or step size oscillate without a clear downward trend.

Solutions:

- Switch the Coordinate System: If you are using Cartesian coordinates, try switching to an optimizer that uses internal coordinates, such as Sella, or vice versa. Internal coordinates can be particularly effective for flexible molecules [22].

- Adjust Convergence Criteria: Loosen the convergence thresholds (e.g., from "Good" to "Normal" or "Basic") if high precision is not critical for your immediate goal. This is controlled by the

Convergence%Qualitykeyword or similar in your software [6]. - Select a Different Optimizer: If one optimizer fails, try another. Benchmark data shows that success rates vary significantly. For example, if "geomeTRIC (tric)" fails, "Sella (internal)" might succeed on the same system [22].

- Increase Maximum Iterations: If the optimization is progressing steadily but slowly, increase the

MaxIterationsparameter to allow more steps [6].

Problem: Optimization Converges to a Saddle Point (Not a Minimum)

Symptoms:

- Frequency calculations on the optimized structure reveal one or more imaginary frequencies, indicating a transition state or higher-order saddle point [22].

Solutions:

- Enable Automatic Restarts: Some software, like AMS, can automatically restart optimizations if a saddle point is detected. This requires enabling the

PESPointCharacterproperty and settingMaxRestartsto a value greater than 0 (e.g., 5) [6]. - Use an Optimizer with Better Minima-Finding Performance: Refer to benchmark data. For instance, "Sella (internal)" consistently finds more true minima than its Cartesian counterparts for many NNPs [22].

- Apply a Small Displacement: Manually distort the molecular geometry along the normal mode of the imaginary frequency and restart the optimization.

Problem: Noisy Gradients from Neural Network Potentials (NNPs)

Symptoms:

- Unstable optimization steps, even with robust optimizers.

- Inconsistent performance across different NNP architectures.

Solutions:

- Use a Noise-Tolerant Optimizer: First-order methods like FIRE are often more robust against noise on the potential energy surface compared to second-order methods like L-BFGS [22].

- Employ Internal Coordinates: Optimizers using internal coordinates, such as Sella, have demonstrated faster and more reliable convergence with various NNPs, as they are less sensitive to the pathologies of the potential energy surface [22].

- Verify NNP Precision: Ensure the NNP is running at sufficient numerical precision (e.g.,

float32-highest), as lower precision can cause convergence failures that are resolvable by increasing the allowed steps [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Optimizer Performance

Objective: To systematically evaluate the performance of different geometry optimizers and coordinate systems for a set of molecular structures.

Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a diverse set of molecular structures (e.g., 25 drug-like molecules) representing different chemistries and conformational flexibility [22].

- Optimizer Setup: Select a range of optimizers (e.g., L-BFGS, FIRE, Sella, geomeTRIC) with both Cartesian and internal coordinate options.

- Convergence Criteria: Define a consistent convergence threshold for all tests, typically based on the maximum force component (e.g.,

fmax= 0.01 eV/Å or 0.231 kcal/mol/Å). Disable other convergence criteria to ensure a fair comparison if necessary [22]. - Execution: Run each optimizer on each molecular system with a fixed maximum step limit (e.g., 250 steps).

- Data Collection: Record for each run:

- Success/Failure status.

- Number of steps to convergence.

- Final energy.

- Post-Processing Analysis: Perform frequency calculations on all successfully optimized structures to determine if they are true local minima (zero imaginary frequencies) or saddle points (one or more imaginary frequencies) [22].

Workflow: Benchmarking Optimizer Performance

Protocol 2: Transition State Restart Procedure

Objective: To automatically recover from a geometry optimization that has converged to a saddle point.

Methodology:

- Enable Characterization: In the

Propertiesblock, setPESPointCharacter = Trueto calculate the lowest Hessian eigenvalues after optimization [6]. - Configure Restarts: In the

GeometryOptimizationblock, setMaxRestartsto a value greater than 0 (e.g., 5) to enable the automatic restart feature [6]. - Disable Symmetry: For the restart mechanism to work correctly, disable symmetry using

UseSymmetry False. The displacement is often symmetry-breaking [6]. - Displacement: If a saddle point is found, the algorithm will automatically displace the geometry along the imaginary vibrational mode. The displacement size can be controlled with the

RestartDisplacementkeyword (default: 0.05 Å) [6]. - Re-optimization: The optimization is automatically restarted from the displaced geometry. This process repeats until a minimum is found or the maximum number of restarts is reached.

Workflow: Automatic Restart for Saddle Points

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Geometry Optimization Studies

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sella Optimizer | An open-source package for geometry optimization and transition state location using internal coordinates. It employs rational function optimization and a quasi-Newton Hessian update [22]. |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer | A general-purpose optimization library that uses translation–rotation internal coordinates (TRIC) and standard L-BFGS for robust convergence [22]. |

| L-BFGS Optimizer | A quasi-Newton algorithm that approximates the Hessian matrix. Often efficient but can be sensitive to noisy potential energy surfaces [22]. |

| FIRE Optimizer | A first-order, molecular-dynamics-based minimization method designed for fast structural relaxation and known for noise tolerance [22]. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) | A machine-learned potential, such as OrbMol or AIMNet2, that provides DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling faster optimization cycles [22]. |

| PESPointCharacter | A computational property keyword that triggers the calculation of the lowest Hessian eigenvalues to determine the character (minimum, transition state) of an optimized structure [6]. |

Diagnosing and Solving Common Convergence Failures in Stiff Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary convergence criteria in a geometry optimization, and how do I interpret them? A geometry optimization is considered converged when several conditions are met simultaneously [6]:

- The energy change between subsequent steps is smaller than the

Energythreshold (in Hartree) multiplied by the number of atoms in the system. - The maximum Cartesian nuclear gradient is below the

Gradientsthreshold (in Hartree/Å). - The root mean square (RMS) of the Cartesian nuclear gradients is below 2/3 of the

Gradientsthreshold. - The maximum Cartesian step is smaller than the

Stepthreshold (in Ångstrom). - The root mean square (RMS) of the Cartesian steps is smaller than 2/3 of the

Stepthreshold. If the maximum and RMS gradients are 10 times stricter than the convergence criterion, the step criteria (the last two points) are ignored [6].

Q2: My optimization is oscillating between two similar energy values. What does this mean and how can I address it? Oscillation in the energy or coordinates often indicates that the optimization process is struggling to find a clear downhill path on the potential energy surface. This can be due to a poorly conditioned Hessian (an approximation of the second derivative matrix) or the optimizer taking steps that are too large for the region of the surface it is in [27] [28]. To address this:

- Tighten Convergence Criteria: Switching from

NormaltoGoodorVeryGoodquality can force the optimization to take smaller, more precise steps [6]. - Improve the Hessian: A better initial Hessian can dramatically improve convergence. Some software packages can compute an initial Hessian using faster, approximate methods (e.g., neural network potentials or GFN2-xTB) to guide the optimization [29].

- Change Coordinates: Using delocalized internal coordinates instead of Cartesians can often enhance convergence rates by an order of magnitude for molecular systems [27].

Q3: The optimization is making very slow progress, with minimal energy change over many steps. What should I do? Slow progress, or a "plateau" in the energy, suggests the optimizer is in a very flat region of the potential energy surface. This can be addressed by:

- Checking Gradient Values: If the gradients are also very small, the optimization may be close to convergence, and you should simply allow it to continue or slightly tighten the gradient convergence threshold [6].

- Restarting with a Better Hessian: In a flat region, the optimizer's internal Hessian may be inaccurate. Restarting the optimization from the current geometry with a recalculated Hessian can provide a better direction for the next step [27].

- Using Advanced Optimizers: Algorithms like Adam or RMSProp, common in machine learning, use adaptive moment estimation to navigate flat regions and noisy gradients more effectively. Similar principles are embedded in advanced optimizers like the eigenvector-following (EF) algorithm or GDIIS for molecular systems [28] [27].

Q4: The optimization converged, but a frequency calculation reveals an imaginary mode. What happened? This indicates that the optimization has likely converged to a saddle point (like a transition state) rather than a local minimum [29]. Many optimization algorithms can automatically handle this if configured correctly:

- Enable Automatic Restarts: You can configure the optimizer to perform a PES point characterization upon convergence. If a transition state is found, it can automatically restart the optimization after a small displacement along the imaginary mode. This requires setting

MaxRestartsto a value >0 and ensuring symmetry is disabled withUseSymmetry False[6]. - Transition State Optimization: If you intentionally suspect a transition state, use a dedicated transition-state optimization task (

optimize_ts), which is designed to walk uphill along the lowest Hessian mode and downhill along all others [29] [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Oscillating Optimizations

Problem: The total energy, gradients, or coordinates show a clear oscillatory pattern over successive optimization steps.

Methodology for Diagnosis:

- Plot the Data: Generate plots of the total energy and the maximum gradient versus optimization cycle.

- Identify the Pattern: Visually confirm an oscillatory pattern (values going up and down) instead of a steady decrease.

- Check the Coordinate System: Consult your output files to determine which coordinate system (Cartesian, Z-matrix, delocalized internals) is being used.

Resolution Protocol:

- Primary Action: Reduce the maximum step size allowed by the optimizer. This prevents it from "jumping over" the minimum.

- Secondary Action: If using a quasi-Newton method, request a Hessian update or recomputation. An improved second-derivative matrix provides a better estimate of the curvature, leading to more rational step directions [27].

- Advanced Action: Consider switching optimizers. An algorithm that incorporates momentum, analogous to SGD with Momentum in machine learning, can help smooth out oscillations and push through noisy regions [28].

Resolving Slow or Stalled Optimizations

Problem: The optimization is proceeding with a very small energy decrease per step, and convergence seems unlikely within the maximum number of steps.

Methodology for Diagnosis:

- Check Convergence Criteria: Review the convergence thresholds currently in use (e.g.,

Basic,Normal). Excessively loose criteria can make an optimization appear stalled when it is simply "close enough" by its own standards [6]. - Examine Gradient Norms: If the energy change is small but the gradients remain large, the system may be on a shallow but sloping potential energy surface. This is a genuine slow convergence issue.

- Review the Initial Geometry: Ensure the starting structure is chemically reasonable. A poor initial guess can lead to long, slow journeys across flat potential energy surfaces.

Resolution Protocol:

- Primary Action: Tighten the convergence criteria, particularly for the energy and gradients. Using the

Qualitysetting to switch fromNormaltoGoodwill reduce all thresholds by an order of magnitude [6]. - Secondary Action: Change the optimization coordinate system to delocalized internal coordinates, which are often more efficient for molecular systems [27] [29].

- Advanced Action: For molecular systems, consider using an optimizer that employs the GDIIS algorithm, which can often accelerate convergence compared to standard quasi-Newton methods [27].

Data Tables for Convergence Criteria

Table 1: Standard Convergence Quality Settings

This table summarizes the predefined convergence criteria in Hartree (Ha) and Ångstrom (Å). The Quality keyword offers a quick way to change all thresholds [6].

| Quality Setting | Energy (Ha) | Gradients (Ha/Å) | Step (Å) | StressEnergyPerAtom (Ha) |