QM/MM in Biology: A Practical Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Simulation

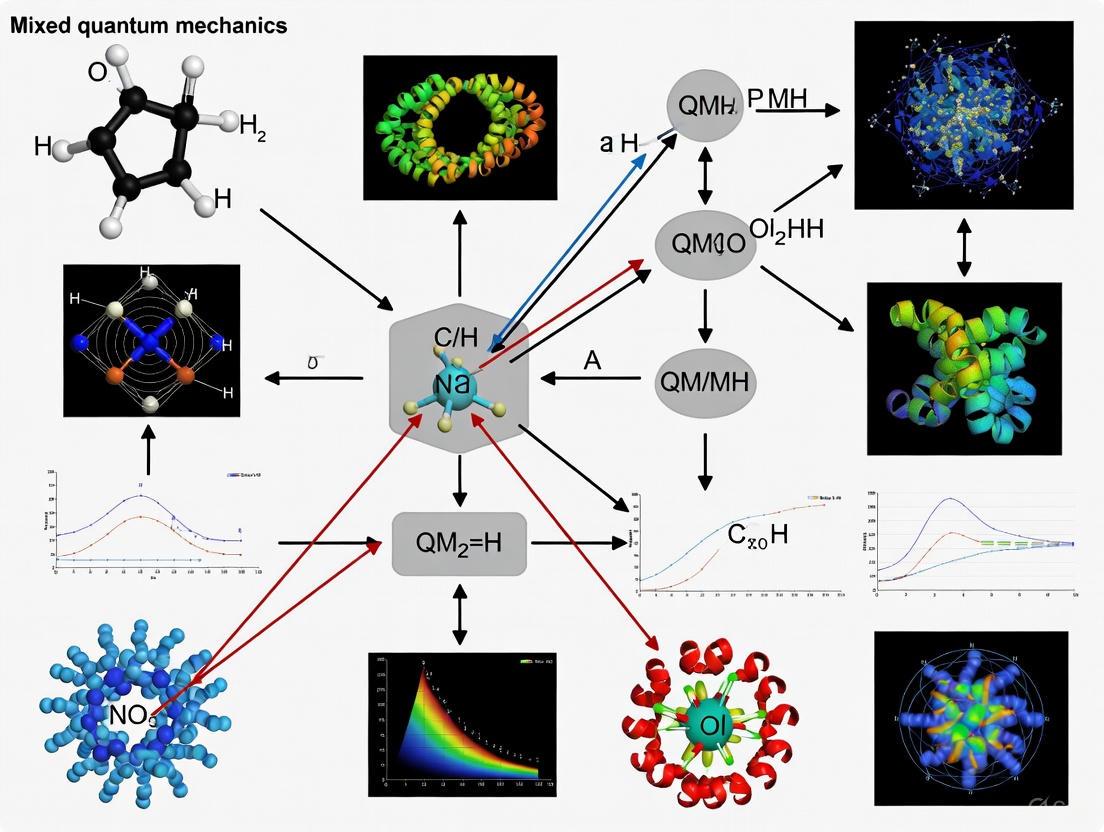

This comprehensive review explores the foundational principles, diverse methodologies, and cutting-edge applications of mixed Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) in biological systems.

QM/MM in Biology: A Practical Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Simulation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the foundational principles, diverse methodologies, and cutting-edge applications of mixed Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) in biological systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the article demystifies how QM/MM bridges the gap between electronic-level accuracy and macromolecular simulation, enabling the study of enzyme mechanisms, drug-receptor interactions, and excited-state dynamics. It provides a practical framework for selecting methods like DFT and SCC-DFTB, troubleshooting common optimization issues in software like Q-Chem and Amber, and validating results against experimental data. By synthesizing recent advances and future directions, including the role of AI and quantum computing, this guide serves as an essential resource for leveraging QM/MM to tackle challenging biological problems and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Quantum Leap: Why QM/MM is Essential for Modern Biological Simulation

The quest to understand biological processes at the atomistic level presents a unique challenge: the systems are vast, comprising millions of atoms, yet the crucial chemical events—such as bond breaking and formation—are governed by quantum mechanical (QM) effects. The hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) approach, introduced in the seminal 1976 paper of Warshel and Levitt, elegantly bridges this scale gap [1] [2]. This methodology combines the accuracy of ab initio QM calculations for the reactive center with the computational speed of molecular mechanics (MM) for the surrounding environment, enabling realistic simulations of chemical processes in proteins and solution [1] [3]. The profound impact of this "multiscale modeling" was recognized with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Karplus, Levitt, and Warshel [1] [3].

For drug development professionals and researchers, QM/MM has become an indispensable tool for investigating phenomena that escape purely experimental probes. Its applications are versatile, spanning the determination of enzymatic reaction mechanisms and transition states, understanding the effects of point mutations on catalysis, refining crystal structures with exotic co-factors, and studying ligand-protein interactions for binding affinity estimations [4]. By treating the electronic structure of the active site quantum mechanically, while accounting for the electrostatic and steric influence of the protein matrix, QM/MM simulations provide unprecedented insights into the inner workings of biological macromolecules.

Foundational QM/MM Methodologies

The core principle of QM/MM is the division of the total system into a QM region, treated with a quantum chemical method, and an MM region, described by a classical force field. The total energy of the system is calculated through one of two principal schemes: the additive or subtractive method [1] [4].

Additive and Subtractive Schemes

In the additive scheme, the total energy is expressed as a sum of three distinct components [5] [2]: ( E{total} = E{QM} + E{MM} + E{QM/MM} ) Here, ( E{QM} ) is the energy of the quantum region, ( E{MM} ) is the energy of the classical region, and ( E_{QM/MM} ) is the coupling term that describes the interactions between the two regions. This coupling term typically includes electrostatic, van der Waals, and bonded interactions [5]. The additive scheme is widely used in biological applications because it does not require MM parameters for the QM atoms, as their energy is computed quantum mechanically [4].

The subtractive scheme, famously implemented in the ONIOM method, involves three separate calculations [1] [5]: ( E{total} = E{MM}(Total) + E{QM}(QM) - E{MM}(QM) ) An MM calculation is performed on the entire system, a QM calculation on the QM region, and another MM calculation on the QM region alone. The final MM term is subtracted to avoid double-counting the interactions within the QM subsystem. While simpler to implement, a key disadvantage is its reliance on MM parameters for the QM region, which can be problematic for reacting molecules or transition states [5].

Electrostatic Embedding Schemes

The treatment of electrostatic interactions between the QM and MM regions is critical and is handled at different levels of sophistication [1].

- Mechanical Embedding: This is the simplest scheme, where the QM-MM electrostatic interaction is calculated at the MM level. The QM region's electron density is computed in isolation, without being polarized by the MM environment. This approach is no longer recommended for modeling biochemical reactions because the charge distribution in the QM region changes during the reaction, making a fixed set of MM parameters inadequate [1] [4].

- Electrostatic Embedding: This is the most common and recommended approach for state-of-the-art biomolecular simulations. The partial charges of the MM atoms are included directly in the QM Hamiltonian, meaning the electronic wave function of the QM region is polarized by the classical environment. This is achieved by adding one-electron integrals to the Hamiltonian [1] [5]. This scheme provides a more realistic description but can lead to overpolarization issues near the QM/MM boundary.

- Polarized Embedding: This is the most advanced scheme, allowing for mutual polarization between the QM and MM regions. The MM force field itself becomes polarizable, responding to the changing charge distribution of the QM region. Although more accurate, polarizable force fields for biomolecules are not yet in widespread use, making this scheme less common in practical applications [1] [4].

Handling the QM/MM Boundary

A common challenge arises when the boundary between the QM and MM regions cuts through a covalent bond (e.g., including a side chain in the QM region while the backbone is in the MM region). Special techniques are required to saturate the dangling valence of the QM atom [1] [5].

- Link Atom Method: An additional atom (usually hydrogen) is introduced to cap the QM atom. While simple, this can cause overpolarization as the link atom is spatially very close to the highly charged MM boundary atom [5].

- Boundary Atom Schemes: The MM atom at the boundary is replaced with a special atom that participates in both the QM and MM calculations, mimicking the electronic character of the original group [1].

- Localized-Orbital Schemes (e.g., GHO): Hybrid orbitals are placed at the boundary, with some kept frozen to cap the QM region and satisfy its valency without introducing fictitious atoms [1] [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and steps involved in setting up a QM/MM simulation:

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Selecting the appropriate level of theory is a critical step in QM/MM simulation design, as it directly governs the balance between computational cost and accuracy. The following tables summarize key choices and their trade-offs.

Table 1: Comparison of QM Methods for Biological Applications

| QM Method | Typical Accuracy | Computational Cost | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [4] [3] | Good for structures, variable for energies | Medium | Good cost/accuracy trade-off; includes electron correlation | Not systematically improvable; performance depends on functional | Large QM regions (>100 atoms); routine reaction modeling |

| B3LYP (Hybrid GGA) [3] | Good for organic molecules | Medium-High | Widely used and tested; reliable for many systems | Poor for dispersion interactions; requires corrections | General-purpose enzyme mechanism studies |

| M06/M06-2X (Meta-GGA) [3] | High for main-group thermochemistry | Medium-High | Good for non-covalent interactions; broad applicability | Parameterized nature can limit transferability | Reactions where dispersion is critical |

| Second-Order Møller-Plesset (MP2) [4] | High | High | More accurate than DFT; systematically improvable | High cost; fails for some electronic structures | High-accuracy single-point energies |

| Spin-Component Scaled MP2 (SCS-MP2) [4] | Very High | High | Improved accuracy over MP2 | Computationally expensive | Benchmarking and validation |

| Semi-Empirical Methods (PM6, DFTB) [6] [3] | Low to Medium | Very Low | Enable long timescale simulations; good for sampling | Parametric; can have large errors for specific reactions | Initial sampling, very large systems, QM/MM MD |

| Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) [4] | Gold Standard | Prohibitive for most systems | Highest achievable accuracy | Extreme computational cost | Not yet feasible for standard bio-QM/MM |

Table 2: QM/MM Technical Schemes and Performance

| Scheme / Treatment | Accuracy | Computational Cost | Implementation Complexity | Recommended Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Scheme [4] | High | Medium | Medium | Standard for most biomolecular simulations; no need for MM parameters for QM region |

| Subtractive Scheme (ONIOM) [5] [4] | Medium | Low | Low | Simple systems; when MM parameters for QM region are reliable |

| Electrostatic Embedding [1] [4] | High | Medium | Medium | Default choice; accounts for polarization of QM region by MM environment |

| Mechanical Embedding [1] [4] | Low | Low | Low | Mostly deprecated for reactions; potential use for ground-state properties |

| Link Atoms [1] [5] | Medium (with risks) | Low | Low | Simple boundaries; can cause overpolarization artifacts |

| Generalized Hybrid Orbitals (GHO) [5] | High | Low-Medium | High | Robust treatment for covalent boundaries; avoids fictitious atoms |

Application Notes: Protocol for Enzymatic Reaction Mechanism Investigation

This protocol outlines the key steps for employing QM/MM to elucidate an enzymatic reaction mechanism, using best practices curated from the literature [4].

System Setup and Preparation

- Initial Structure Selection: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure of the enzyme, preferably with a bound substrate or inhibitor. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the primary source.

- System Assembly: Use molecular modeling software (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, GROMACS) to prepare the system. This involves:

- Adding missing hydrogen atoms and resolving any missing loops.

- Parameterizing the substrate and any cofactors for the MM force field.

- Solvating the enzyme in a water box, ensuring a sufficient buffer (e.g., 10 Ã…) around the protein.

- Adding counterions to neutralize the system's total charge.

- MM Equilibration: Perform extensive classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to relax the system, relieve steric clashes, and sample a representative configuration. This typically involves energy minimization, gradual heating to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K), and equilibration under constant pressure and temperature (NPT) conditions.

QM/MM Region Selection and Method Choice

- Defining the QM Region: The QM region should include the substrate, catalytic cofactors (e.g., FAD, NADH), and amino acid side chains directly involved in the reaction (e.g., proton donors, nucleophiles, residues stabilizing transition states). A typical QM region ranges from 50 to 200 atoms. Care must be taken to avoid cutting through conjugated systems or charged groups [1].

- Choosing the QM Method and Basis Set:

- QM Method: Density Functional Theory (DFT) is the most common choice. Select a functional validated for similar chemical reactions (e.g., B3LYP with dispersion corrections (D3), M06-2X for non-covalent interactions). Always add dispersion corrections for biomolecular systems [4].

- Basis Set: Use a polarized double-zeta basis set (e.g., 6-31G) as a minimum. Polarization functions are essential. Diffuse functions are generally avoided near the QM/MM boundary to prevent artifacts but can be used on atoms in the central QM region if necessary for anions or excited states [4].

- Selecting the QM/MM Scheme: Employ an additive scheme with electrostatic embedding for the most realistic description of the system's electronics [4].

Simulation, Optimization, and Validation

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the structure of the entire system to a local minimum (reactant, intermediates, product) using QM/MM. This involves iteratively updating the QM wavefunction and MM coordinates until the forces on all atoms are minimized.

- Transition State Optimization: Locate the transition state(s) connecting minima. Techniques include the growing string method, synchronous transit methods (e.g., QST2, QST3), or using an eigenvector-following algorithm. The nature of the transition state should be confirmed by a frequency calculation, which should yield a single imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

- Energy Validation and Mechanism Discrimination:

- Calculate the reaction energy profile (activation barriers, reaction energies).

- Plausibility Check: Compare calculated activation barriers (typically 14-20 kcal/mol for enzymes) against experimental ranges. A value outside 5-25 kcal/mol should be re-examined [4].

- Environmental Validation: A key test for a correct mechanism and level of theory is to demonstrate a clear catalytic effect. Compare the reaction profile in the enzyme to the profile of the same QM system in the gas phase or water. The enzyme environment should significantly stabilize the transition state relative to the reactant [4].

- If possible, validate the chosen DFT functional against a higher-level method (e.g., SCS-MP2, CCSD(T)) on a small model of the active site.

The logical flow of this validation process is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Software and Force Fields

A range of software packages enables QM/MM simulations, from monolithic suites to flexible interface-based tools.

Table 3: Key Software Solutions for QM/MM Simulations

| Software / Tool | Type | Key Features | Licensing | Relevance to QM/MM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER [5] [7] | MM/MD Suite with QM/MM | Includes SQM (semi-empirical QM); interfaces with ab initio packages like GAMESS [5] | Proprietary, Free open source | Widely used in academia for biomolecular QM/MM; well-documented |

| CHARMM [7] | MM/MD Suite with QM/MM | Native QM/MM capabilities; supports various QM methods | Proprietary, Commercial | Pioneer in QM/MM; strong tradition in biomolecular simulations |

| CP2K [7] | Atomistic Simulation | Fast QM methods (DFT); excellent scaling for large systems | Free open source (GPL) | Powerful for QM/MM MD with large QM regions; popular for materials and bio |

| GAMESS [5] | QM Package | Versatile ab initio methods; frequently used as QM engine in QM/MM | Free for academics | Common choice when interfaced with AMBER or other MM engines |

| ChemShell [5] | Hybrid Scripting Environment | Flexible interface between various QM and MM packages (e.g., DL_POLY, GAMESS) | Free open source | High flexibility; for experts who need to combine specific codes |

| TeraChem [8] [7] | QM/MM Package | Extremely fast GPU-accelerated ab initio calculations (DFT, HF, CASSCF) | Proprietary, Trial available | "Apex predator" for speed; ideal for large QM regions and excited states |

| pDynamo [8] | Program/Library | Python-based; developed specifically for hybrid QC/MM potentials | Free open source | Designed for QM/MM; good balance of usability and performance |

| QSite (Schrödinger) [9] | QM/MM Program | Integrated with Jaguar QM code; user-friendly GUI via Maestro; local MP2 | Proprietary, Commercial | Optimized for drug discovery workflows; robust for metalloproteins |

| GROMACS [7] | MD Engine | High-performance MD; supports QM/MM via interfaces | Free open source (GPL) | Increasingly used for QM/MM MD due to its superior MD performance |

| Homosalate-d4 | Homosalate-d4, MF:C16H22O3, MW:266.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Colistin adjuvant-2 | Colistin Adjuvant-2|Potentiates Colistin Activity | Colistin adjuvant-2 is a research compound that enhances colistin efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Concluding Remarks

The QM/MM methodology has firmly established itself as a cornerstone of modern computational biochemistry and drug discovery. By bridging the scales from the quantum world of electrons to the macro world of proteins, it provides a physically rigorous framework to interrogate biological mechanisms that are otherwise inaccessible. As summarized in this application note, its successful implementation requires careful attention to system setup, method selection, and, crucially, result validation.

The future of QM/MM is bright, with trends pointing towards increased use of ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics for enhanced sampling, the incorporation of more accurate polarizable force fields, the application of high-level wavefunction methods like coupled cluster, and the integration of machine learning potentials to further push the boundaries of system size and simulation time [6] [3]. For researchers and drug developers, mastering these protocols empowers a deeper, atomic-level understanding of function, mechanism, and inhibition, directly informing the rational design of new experiments and therapeutics.

The application of quantum mechanics to biological systems has opened new frontiers in understanding molecular-scale processes underlying life itself. At the heart of this intersection stand two fundamental principles: the Schrödinger equation, which describes the quantum behavior of particles, and the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which makes computational tractability possible for complex biomolecules. These principles form the theoretical foundation for mixed quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches that enable researchers to study biological phenomena with quantum mechanical accuracy where it matters most.

The Schrödinger equation provides the fundamental framework for describing how electrons and nuclei behave in molecules. For any molecular system, the time-independent Schrödinger equation HΨ = EΨ describes the wavefunction (Ψ) and energy (E) of the system, where H represents the Hamiltonian operator encompassing all kinetic and potential energy contributions [10]. In biological systems, exact solutions to this equation remain impossible for all but the simplest molecular models due to the computational complexity involved [11].

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation (BOA) resolves this challenge by exploiting the significant mass difference between electrons and atomic nuclei. Since nuclei are thousands of times heavier than electrons, they move correspondingly slower [12]. The BOA therefore assumes that for any fixed nuclear configuration, electrons rearrange themselves instantaneously [13]. This allows separation of the molecular wavefunction into electronic and nuclear components: Ψtotal = ψelectronic · ψnuclear [13]. This separation creates a potential energy surface on which nuclei move, making computational analysis of biological molecules feasible [14].

Theoretical Foundation

The Mathematical Framework

The complete molecular Hamiltonian encompasses all energy contributions for a biological system:

Htotal = Tn + Te + Ven + Vee + Vnn

Where Tn represents nuclear kinetic energy, Te represents electronic kinetic energy, and the V terms denote potential energy operators for electron-nucleus (Ven), electron-electron (Vee), and nucleus-nucleus (Vnn) interactions [13].

Applying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation simplifies this Hamiltonian by effectively removing the nuclear kinetic energy term (Tn) when solving for electronic motion. The remaining electronic Hamiltonian becomes:

He = Te + Ven + Vee + Vnn

This allows solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclear positions:

Heχ(r,R) = Ee(R)χ(r,R)

Here, χ(r,R) represents the electronic wavefunction depending on both electron (r) and nuclear (R) coordinates, and Ee(R) gives the electronic energy as a function of nuclear configuration [13]. The resulting potential energy surface enables subsequent analysis of nuclear motion through a separate Schrödinger equation:

[Tn + Ee(R)]φ(R) = Eφ(R)

This separation dramatically reduces computational complexity. For example, a benzene molecule (12 nuclei, 42 electrons) would require solving one equation with 162 coordinates without the BOA. With the BOA, researchers solve one equation for 126 electronic coordinates multiple times across different nuclear configurations, then one equation for 36 nuclear coordinates [13].

Table 1: Key Components of the Molecular Hamiltonian in Biological Systems

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Physical Significance | Role in BOA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Kinetic Energy | Tn = -∑A(1/2MA)∇A² | Energy from nuclear motion | Neglected in electronic SE |

| Electronic Kinetic Energy | Te = -∑i(1/2)∇i² | Energy from electron motion | Retained in electronic SE |

| Electron-Nucleus Potential | Ven = -∑i,A(ZA/riA) | Coulomb attraction between electrons and nuclei | Retained in electronic SE |

| Electron-Electron Potential | Vee = ∑i>j(1/rij) | Coulomb repulsion between electrons | Retained in electronic SE |

| Nucleus-Nucleus Potential | Vnn = ∑B>A(ZAZB/RAB) | Coulomb repulsion between nuclei | Retained in electronic SE |

Breakdown Conditions in Biological Systems

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation remains valid when electronic energy surfaces are well-separated: Eâ‚€(R) ≪ Eâ‚(R) ≪ Eâ‚‚(R) ≪ ... for all nuclear configurations R [13]. However, this condition fails at conical intersections where electronic states become degenerate, making non-adiabatic transitions between states possible. Such breakdowns are particularly relevant in biological photochemistry, including:

- Photosynthesis: Energy transfer in light-harvesting complexes

- Vision: Photoreception in retinal pigments

- DNA Repair: Photodamage and repair mechanisms [14]

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual separation of electronic and nuclear motions underlying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation:

Application Notes for Biological Systems

QM/MM Methodologies for Biological Macromolecules

Mixed quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches represent the primary computational framework implementing Born-Oppenheimer-based quantum methods for biological systems. These methods partition the system into a QM region (typically the active site) treated with quantum chemistry, and an MM region (protein scaffold and solvent) treated with molecular mechanics [11] [15].

Table 2: QM/MM Partitioning Strategies for Biological Systems

| System Type | QM Region | MM Region | Key Interactions | Computational Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Catalysis | Active site residues, cofactors, substrate | Protein scaffold, solvent waters | Covalent bond cutting, electrostatic | DFT (50-100 atoms) |

| Membrane Protein Function | Ligand binding pocket, key residues | Lipid bilayer, protein transmembrane domains | Electrostatic, hydrophobic | Semiempirical (100-200 atoms) |

| Photosynthetic Complexes | Chromophore, nearby residues | Protein environment, membrane | Electronic excitation, energy transfer | TD-DFT (100-300 atoms) |

| Nucleic Acid Processing | Reactive nucleotides, catalytic ions | DNA/RNA backbone, solvation shell | Electron transfer, protonation | DFTB (200-500 atoms) |

Biological Phenomena Accessible Through QM/MM Approaches

Enzyme Catalysis: QM/MM methods elucidate reaction mechanisms in enzymatic catalysis by modeling bond breaking/formation in active sites. For example, ATP hydrolysis in motor proteins like PcrA helicase involves sequential bond rearrangements that can be tracked at femtosecond resolution using QM/MM dynamics [11]. The QM region (ATP, Mg²⺠ions, key amino acids) undergoes electronic structure analysis while the MM region (protein scaffold, solvent) provides electrostatic stabilization.

Biological Energy Transduction: Photosynthetic reaction centers and respiratory chain complexes involve electron transfer processes requiring quantum mechanical treatment. The BOA enables calculation of electronic coupling elements and reorganization energies governing electron transfer rates through the protein matrix [11].

Signal Transduction and Sensing: Photoreception processes in vision and magnetoreception in migratory birds involve quantum effects. In retinal rhodopsin, photoisomerization occurs through conical intersections where the BOA may break down, requiring specialized non-adiabatic dynamics methods [11] [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: QM/MM Simulation of Enzymatic Reaction

Objective: Characterize the reaction mechanism and energy profile for a bond cleavage/catalysis event in a biological macromolecule.

Principle: Combine accurate quantum chemical treatment of the reactive region with efficient molecular mechanics description of the protein environment to simulate chemical transformations in biological systems [11] [15].

System Setup Requirements:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with minimum 32 cores, 128GB RAM

- Software: QM/MM package (e.g., CP2K, Q-Chem, GAMESS), molecular visualization

- Initial Structure: High-resolution crystal structure (≤2.0Å) from PDB

Procedure:

System Preparation (2-4 days)

- Obtain protein-ligand complex structure from PDB

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and protonation states appropriate for physiological pH

- Solvate the system in explicit water molecules (minimum 10Ã… padding)

- Apply physiological ion concentration (0.15M NaCl)

MM Equilibration (1-2 days)

- Perform energy minimization (5,000 steps steepest descent)

- Gradually heat system from 0K to 310K over 100ps NVT simulation

- Equilibrate density with 100ps NPT simulation at 1 atm

- Conduct production MD (1-5ns) for conformational sampling

QM/MM Partitioning (1 day)

- Select QM region: substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors, metal ions (typically 50-150 atoms)

- Treat QM/MM boundary with link atoms or pseudopotentials

- Define electrostatic embedding scheme for polarization effects

QM Method Selection (1 day)

- Choose DFT functional (B3LYP, ωB97X-D) with double-zeta basis set for geometry optimization

- Select higher-level method (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) with triple-zeta basis for single-point energies

- Apply dispersion correction for van der Waals interactions

Reaction Pathway Characterization (5-10 days)

- Identify reactant, product, and putative transition state structures

- Perform QM/MM geometry optimization for stationary points

- Validate transition states with frequency analysis (exactly one imaginary mode)

- Conduct potential energy surface scans for difficult reactions

Free Energy Calculation (7-14 days)

- Employ umbrella sampling along reaction coordinate

- Utilize 10-20 windows with 20-50ps sampling per window

- Construct potential of mean force using WHAM method

- Estimate quantum tunneling contributions where appropriate

Troubleshooting:

- Energy Drift: Check QM/MM electrostatic interactions; adjust embedding scheme

- Convergence Failure: Increase QM convergence criteria; improve initial guess

- Boundary Artifacts: Extend QM region size; apply improved boundary treatment

Protocol: Non-Adiabatic Dynamics for Biological Photochemistry

Objective: Simulate photoinduced processes in biological systems where the BOA breaks down, such as vision or photosynthetic energy transfer.

Specialized Requirements:

- Software: Non-adiabatic dynamics package (e.g., SHARC, Newton-X)

- Electronic Structure: Multireference methods (CASSCF, CASPT2) for excited states

Procedure:

- Prepare chromophore-protein complex using standard QM/MM protocols

- Compute excited state potential energy surfaces using TD-DFT or multireference methods

- Identify conical intersection seams and minimum energy crossing points

- Initiate trajectory surface hopping dynamics from Franck-Condon point

- Statistical analysis of quantum yields and time constants from ensemble (100-1000 trajectories)

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Biological QM/MM Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Key Features | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM/MM Software Packages | CP2K, Amber, GROMACS-QM/MM, CHARMM | Integrated workflows, Force field compatibility | Enzyme catalysis, Drug binding |

| Electronic Structure Methods | DFT (B3LYP, ωB97X-D), CASSCF, DFTB | Accuracy/efficiency balance, Excited states | Reaction mechanisms, Photobiology |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Umbrella sampling, Metadynamics, Replica exchange | Free energy calculation, Barrier crossing | Reaction rates, Conformational changes |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, PyMOL, MDAnalysis | Reaction coordinate analysis, Trajectory visualization | Data interpretation, Publication figures |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU clusters, Quantum processors (emerging) | Accelerated computation, Novel algorithms | Large-scale systems, Future applications |

| Egfr-IN-47 | Egfr-IN-47, MF:C29H35N7, MW:481.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| TrxR-IN-4 | TrxR-IN-4|Thioredoxin Reductase Inhibitor | TrxR-IN-4 is a potent thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Directions

Quantum Biology Phenomena

The BOA framework enables investigation of genuinely quantum phenomena in biological systems:

Magnetoreception: Migratory birds employ two complementary magnetoreception mechanisms: the radical-pair mechanism and magnetite-based mechanism [11]. The radical-pair mechanism involves light-induced electron transfer creating pairs of excited electrons whose magnetic orientation (quantum spin state) is affected by Earth's magnetic field, altering color perception in retinal receptors [11].

Enzymatic Quantum Tunneling: Hydrogen transfer reactions in enzymes often exhibit significant quantum tunneling contributions that can be quantified through QM/MM calculations with instanton corrections.

Quantum Computing Interfaces

Emerging approaches integrate quantum computing with QM/MM simulations through quantum embedding techniques like projection-based embedding (PBE) and density matrix embedding theory (DMET) [16]. These methods enable:

- Quantum processor treatment of active regions (20+ qubits currently feasible)

- Classical MD description of biomolecular environment

- Multi-scale simulation of proton transfer mechanisms (demonstrated for water molecules) [16]

The following workflow illustrates the integration of quantum computing with classical simulation for biological systems:

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Computational Constraints

Current QM/MM implementations face significant constraints:

System Size Limitations: QM regions typically limited to 100-300 atoms even with hybrid approaches [11]. This restricts analysis of long-range electronic effects in large biological complexes.

Timescale Challenges: QM/MM dynamics simulations rarely exceed nanosecond timescales, while many biological processes (enzyme turnover, conformational changes) occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales [11].

Accuracy Trade-offs: DFT functionals struggle with charge transfer states, dispersion forces, and transition metal coordination chemistry common in metalloenzymes.

Methodological Advances

Recent developments address these limitations:

Linear-Scaling Quantum Chemistry: Methods like molecular fragmentation (MFCC) enable quantum treatment of entire proteins by dividing them into smaller fragments with quantum-mechanically computed electrostatic properties [17].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques: Advanced free energy methods accelerate convergence by several orders of magnitude, making nanosecond simulations sufficient for thermodynamic property prediction [17].

Multiscale Embedding: Quantum-classical embedding techniques combine high-level quantum methods for active regions with lower-level methods for the environment, balancing accuracy and computational cost [16].

Combined Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) is a versatile computational tool for modeling biomolecular systems, providing an ab initio description of the most critical regions while treating the surrounding environment with molecular mechanics. This methodology is particularly valuable for investigating enzymatic reaction mechanisms, ligand-protein interactions, and crystal structure refinement, especially for systems with exotic co-factors [4]. The fundamental principle of QM/MM involves dividing the system into a QM region, typically containing the chemically active site, and an MM region comprising the remaining structural framework and solvent environment [5]. Proper execution of this partitioning is crucial for achieving accurate results while maintaining computational feasibility.

The QM/MM approach has revolutionized computational biochemistry by enabling realistic descriptions of chemical processes in biologically relevant environments. Since its introduction in 1976 by Warshel and Levitt, and its widespread adoption in the 1990s, QM/MM has become an indispensable tool for simulating complex biomolecular processes [3]. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for the development of multiscale models underscores the transformative impact of this methodology [3].

System Partitioning Strategies

Defining the QM and MM Regions

The initial and most critical step in any QM/MM study is the appropriate partitioning of the system into quantum and classical regions. The QM region should encompass all molecular entities directly involved in the chemical process under investigation, typically including substrate molecules, catalytic residues, cofactors, and key solvent molecules [4] [5]. The MM region includes the remaining protein scaffold, bulk solvent, and ions, which primarily provide structural context and electrostatic stabilization [4].

When defining the QM region, several strategic considerations must be addressed:

Size versus accuracy trade-off: Larger QM regions provide more chemically complete descriptions but dramatically increase computational costs [4] [18]. A balanced approach typically includes 100-300 atoms in the QM region for enzymatic systems [4].

Chemical completeness: The QM region must include all groups participating in bond-breaking and bond-forming events, as well as those experiencing significant electronic reorganization during the reaction [4].

Charge balance: The QM region should be electrically neutral unless studying charged processes explicitly, as net charges can introduce artifacts [4].

Boundary placement: Covalent bonds crossing the QM/MM boundary require special treatment to maintain proper valence and avoid unphysical polarization [5].

Table 1: Criteria for Selecting Atoms in the QM Region

| Criterion | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Involvement | Atoms directly participating in bond breaking/forming | Catalytic residues, substrate functional groups |

| Electronic Effects | Groups experiencing significant electron density changes | Conjugated systems, metal ions, redox centers |

| Electrostatic Influence | Species providing key stabilization to transition states | Polar residues, specifically bound water molecules |

| Prosthetic Groups | Non-protein components essential to function | Heme, FeMo-cofactor, flavin, metal ions |

Advanced Partitioning Schemes

Conventional QM/MM methods assign atoms to either QM or MM regions at the beginning of simulations without allowing reclassification. While computationally efficient, this static approach presents limitations for processes involving molecular diffusion, such as solvent exchange, substrate uptake, or product release [18] [19].

Adaptive partitioning (AP) schemes address these limitations by allowing on-the-fly reclassification of atoms as QM or MM based on their positions during simulations [18] [19]. These methods employ a buffer zone between the active (QM) and environmental (MM) zones, typically defined as concentric spherical shells (Figure 1). The PAP (permuted adaptive partitioning) and SAP (sorted adaptive partitioning) algorithms smoothly interpolate energies and gradients as molecules move across zones, maintaining energy conservation and numerical stability [19].

Figure 1: Adaptive partitioning scheme using distance-based criteria with buffer zone for smooth QM/MM transitions.

Managing the QM/MM Interface

QM/MM Coupling Schemes

The interaction between QM and MM regions can be handled through different coupling schemes, each with distinct advantages and limitations (Table 2).

Subtractive schemes (e.g., ONIOM) perform three separate calculations: (1) MM calculation on the entire system, (2) QM calculation on the QM region, and (3) MM calculation on the QM region [4] [5]. The total energy is computed as Etotal = EMM(entire system) + EQM(QM region) - EMM(QM region) [5]. While simple to implement and avoiding double-counting issues, subtractive schemes describe QM-MM electrostatic interactions at the MM level and cannot represent polarization of the QM region by its environment [5].

Additive schemes explicitly calculate QM-MM interaction energy terms: Etotal = EMM(MM region) + EQM(QM region) + EQM/MM(QM,MM) [4] [5]. The coupling term includes electrostatic, bonded, and van der Waals interactions [5]. Additive schemes are currently preferred for biological applications as they allow polarization of the QM region by including MM partial charges in the QM Hamiltonian [4] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of QM/MM Embedding Schemes

| Embedding Type | Electrostatic Treatment | Polarization Effects | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Embedding | QM-MM interaction at MM level | None | Low | Systems with minimal electronic polarization |

| Electrostatic Embedding | MM point charges included in QM Hamiltonian | QM region polarized by MM region | Moderate | Most biological applications, reaction mechanisms |

| Polarized Embedding | Mutual polarization between QM and MM regions | Both regions mutually polarized | High | Systems where MM polarization critical |

Boundary Treatments

When covalent bonds cross the QM/MM boundary, special treatments are required to saturate the valency of the QM region. The link atom method is the most common approach, where hydrogen atoms are added along the bond vector between QM and MM atoms [5] [20]. While simple to implement, this method can cause overpolarization issues when the link atom is spatially close to highly charged MM atoms [5].

Advanced boundary treatments include:

Generalized hybrid orbitals (GHO): Creates hybrid orbitals on boundary atoms to maintain proper valence without introducing artificial atoms [5].

Charge scaling schemes: MM charges near the boundary are scaled to reduce overpolarization artifacts [20].

Pseudopotential methods: Use customized potentials to represent the boundary region [5].

The GROMOS implementation offers charge scaling based on distance to the closest QM atom: q'MM = qMM × (2/π) × arctan(s×d), where s is a scaling factor and d is the distance [20].

Practical Implementation Protocols

QM Method Selection

Density functional theory (DFT) represents the most common QM method for biomolecular QM/MM simulations, offering an optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost [4] [3]. Key considerations for DFT functional selection include:

Hybrid functionals (e.g., B3LYP, M06) incorporate exact Hartree-Fock exchange and typically provide improved accuracy for reaction barriers and electronic properties [3].

Dispersion corrections are essential for biomolecular systems, as standard DFT functionals provide incomplete treatment of dispersion interactions [4].

Long-range corrections are necessary for charge transfer processes or non-covalent interactions; functionals like CAM-B3LYP, ωB97XD, or LC-ωPBE are recommended for these cases [3].

Basis set selection requires careful validation through convergence tests. Polarization functions are essential, while diffuse functions should be used cautiously as they may cause artifacts near QM/MM boundaries [4]. For enzymatic reactions, comparing reaction energetics between gas phase, water solvation, and complete enzyme environments provides a valuable test of the methodology - adequate theory levels should show clear catalytic effects in the protein environment [4].

QM/MM Software and Interfaces

Several software packages facilitate QM/MM simulations through interfaces connecting specialized QM and MM programs:

ChemShell: A computational chemistry environment that interfaces with multiple QM (including Molpro) and MM packages (CHARMM, GROMOS, GULP) [21].

GROMOS: Includes interfaces to multiple QM packages (MNDO, Turbomole, MOPAC, DFTB+, xtb, Gaussian, ORCA) and supports various embedding schemes [20].

QMMM: Implements adaptive partitioning schemes and interfaces with NAMD or Tinker for MM calculations and MNDO, Gaussian, or ORCA for QM calculations [18] [19].

Custom interfaces: Specialized interfaces like the AMBER-GAMESS connection enable sophisticated QM/MM molecular dynamics simulations [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QM/MM Simulations

| Software Tool | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAMESS | QM Program | Ab initio quantum calculations | Versatile QM methods, QM/MM compatibility |

| AMBER | MM Package | Molecular dynamics simulations | Biomolecular force fields, QM/MM extensions |

| CHARMM | MM Package | Molecular mechanics simulations | Comprehensive biomolecular modeling |

| ChemShell | QM/MM Environment | Multiscale simulation platform | Integration of multiple QM/MM codes |

| GROMOS | MM Package with QM/MM | Molecular dynamics with embedding | Multiple QM program interfaces, link atom scheme |

Validation and Best Practices

Before embarking on production QM/MM simulations, thorough validation is essential:

Literature survey: Investigate previous computational and experimental studies of similar systems to inform method selection [4].

Functional validation: Compare DFT functionals against high-level calculations (e.g., CCSD(T)) or experimental data for model systems representing the chemistry of interest [4].

Convergence testing: Validate basis set size, QM region size, and boundary treatments through systematic testing [4].

Energetic plausibility: Activation energies for enzymatic reactions typically fall between 14-20 kcal/mol; values outside this range may indicate methodological issues [4].

The following workflow (Figure 2) outlines a comprehensive protocol for QM/MM studies of enzymatic systems:

Figure 2: Comprehensive QM/MM workflow for enzymatic systems from initial setup to reaction analysis.

Application Notes for Biological Systems

For metalloenzymes such as nitrogenase with its FeMo-cofactor, the QM region must include the entire metal cluster, substrates, and surrounding residues that may participate in catalysis [3]. The large size of these clusters (often 70-100 atoms) necessitates careful balance between chemical completeness and computational feasibility [3].

In simulations of enzymatic reactions like the hydrolysis in leucyl-tRNA synthetase, QM/MM molecular dynamics can reveal novel mechanisms inaccessible to pure MM methods [5]. For these systems, electrostatic embedding is essential to capture polarization effects on the reacting species [4] [5].

Adaptive QM/MM methods are particularly valuable for processes with significant molecular diffusion, such as ion transport through channels or substrate binding and release [18] [19]. These methods ensure that species entering the active site are automatically treated at the appropriate QM level without manual redefinition of regions [19].

When setting up QM/MM simulations, researchers should carefully consider the trade-offs between different methodologies and validate their choices against available experimental data or higher-level calculations. With proper implementation, QM/MM simulations provide powerful insights into biological mechanisms at an atomic level of detail.

The development of hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methodologies represents one of the most significant advancements in computational chemistry and biology, creating an essential bridge between quantum physics and classical molecular simulation. This approach enables researchers to study chemical reactions within biologically relevant environments, such as enzyme active sites, while accounting for the surrounding protein matrix and solvent. The 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Martin Karplus, Michael Levitt, and Arieh Warshel for "the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems" formally recognized the transformative impact of this methodology [22] [23] [24]. The honored work, primarily conducted between 1968 and 1976, established the theoretical foundation that today supports widespread activities in modeling biomolecular systems [22]. This framework has become indispensable for understanding enzymatic reaction mechanisms, designing drugs, and probing energy transduction processes in biomolecular machines, making the journey from its conceptual origins to modern implementations a critical narrative in computational biochemistry.

Historical Trajectory of QM/MM Development

The evolution of QM/MM methodologies reflects a continuous pursuit to balance computational accuracy with practical feasibility for studying larger and more complex biological systems.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in QM/MM Development

| Time Period | Key Milestone | Primary Contributors | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1970s | Molecular Mechanics (MM) Force Fields | Lifson, Levitt, Warshel, Allinger | Established "consistent force field" (CFF) using classical physics; enabled first energy-minimizations of entire proteins [22]. |

| 1972 | First Hybrid QM/MM Approach | Warshel & Karplus | Combined PPP QM treatment of π-electrons with MM treatment of σ-framework for conjugated molecules; pioneered hybrid approach [22]. |

| 1976 | First QM/MM Treatment of an Enzyme | Warshel & Levitt | Studied lysozyme mechanism; created modern QM/MM framework with QM region (substrate), MM region (protein), and electrostatic embedding [22] [25] [26]. |

| 1990+ | Methodological Refinement & Mainstream Adoption | Field, Bash, Karplus & others | Integrated QM/MM into geometry optimizations and molecular dynamics (MD); spurred broad community adoption [2]. |

| 2000s-Present | Expansion to Excited States & Complex Biomachines | Multiple research groups | Applied QM/MM to excited states, long-range proton/electron transfer, and mechanochemical coupling in biomolecular machines [27]. |

The Pre-QM/MM Landscape

Before QM/MM emerged, computational chemists faced a stark choice between two approaches. For small systems, quantum mechanical (QM) calculations could provide high accuracy for properties like molecular structure and interaction energies but were computationally prohibitive for large molecules [22]. Alternatively, molecular mechanics (MM) used classical force fields with terms for bond stretching, angle bending, torsional energetics, and non-bonded interactions (e.g., Lennard-Jones potentials and Coulomb's Law) to model much larger systems like proteins [22]. The MM approach was pioneered in the 1960s by groups including Shneior Lifson's at the Weizmann Institute, where Arieh Warshel (a graduate student) and Michael Levitt (a visiting researcher) made seminal contributions to developing "consistent force field" (CFF) methods [22]. This work directly enabled Levitt and Lifson's landmark 1969 energy minimization of entire proteins (myoglobin and lysozyme), demonstrating the potential of computational methods to assist in protein structure refinement [22].

The Seminal 1970s: Bridging the Quantum and Classical Worlds

The critical innovation came from combining these two disparate approaches. In 1972, Martin Karplus and Arieh Warshel, building on Karplus's work with Barry Honig on retinal chromophores, published a hybrid study that treated the π-electrons of a conjugated molecule quantum mechanically (using Pariser-Parr-Pople theory) while the σ-framework was handled with a molecular mechanics force field [22]. This demonstrated the power of a hybrid approach but was still applied to isolated molecules.

The definitive foundational paper for modern QM/MM came in 1976 from Arieh Warshel and Michael Levitt, "Theoretical Study of Enzymatic Reactions: Dielectric, Electrostatic and Steric Stabilization of the Carbonium Ion in the Reaction of Lysozyme" [22] [25] [26]. This work was groundbreaking because it represented the first application of a hybrid QM/MM method to an entire enzyme-substrate complex in solution [26] [2]. Their model treated the catalytic glutamic acid side chain and part of the sugar substrate quantum mechanically, while the rest of the protein and solvent environment was treated with molecular mechanics [22]. This allowed them to evaluate the catalytic effect of the full enzymatic environment. A key scientific insight from this study was that electrostatic stabilization of the transition state was more important for catalytic acceleration than ground-state destabilization, revising the previously held mechanistic understanding of lysozyme [22] [2].

Methodological Evolution and Mainstream Adoption

Following the pioneering work of the 1970s, the subsequent decades saw significant refinement of QM/MM techniques. A pivotal moment for widespread adoption came in 1990 with the publication of a paper by Field, Bash, and Karplus that described the combination of the semiempirical AM1 QM method with the CHARMM MM force field [2]. This integration facilitated the use of QM/MM in geometry optimizations, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and Monte Carlo simulations, making the technique more accessible and practical for a broader scientific community [2]. Since then, development has continued, addressing challenges such as the treatment of covalent bonds at the QM/MM boundary (via link atoms, generalized hybrid orbitals, etc.) [5] [2], the incorporation of MM region polarization [27], and the expansion of the methodology to study excited electronic states using methods like time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) [27].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Modern QM/MM Study of an Enzymatic Reaction

This protocol outlines the general workflow for investigating an enzymatic reaction mechanism using an additive QM/MM approach, inspired by pioneering studies but incorporating contemporary methodologies.

System Preparation

- Initial Coordinate Setup: Obtain the atomic coordinates of the enzyme-substrate complex from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). If an experimental structure is unavailable, a modeled complex may be created via molecular docking.

- System Solvation: Embed the protein-ligand complex in a box of explicit water molecules (e.g., using TIP3P water model) to simulate the aqueous cellular environment. The box size should ensure a sufficient solvent shell (e.g., ≥ 10 Å) around the protein.

- Neutralization and Ionization: Add counterions to neutralize the system's net charge. Further, add physiological salt concentrations (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) to mimic biological conditions more realistically.

Classical Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent and conjugate gradient minimizations to remove any bad steric contacts introduced during the solvation and ionization steps.

- Thermalization and Equilibration: Run a series of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using a classical MM force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM):

- Gradually heat the system from 0 K to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) over 50-100 ps under constant volume (NVT) conditions.

- Subsequently, equilibrate the system under constant pressure (NPT) conditions for at least 100 ps to achieve the correct solvent density.

QM/MM Setup and Simulation

- QM Region Selection: This is a critical step. The QM region should encompass the substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors, and key ions/water molecules directly involved in the chemical reaction. A typical QM region ranges from 50 to 300 atoms [27]. The boundary between QM and MM regions should ideally not cut across highly polar covalent bonds [27].

- Boundary Treatment: For covalent bonds cut by the QM/MM partition, employ a boundary scheme such as the link atom method (capping with hydrogen atoms) or the more advanced Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO) method to saturate the valency of the QM region [5] [2].

- Electrostatic Embedding: In the additive scheme, the total energy is calculated as:

E_Total = E_QM + E_MM + E_QM/MM[26] [27]. The coupling termE_QM/MMincludes electrostatic, van der Waals, and bonded interactions. For the electrostatic component, the MM point charges are incorporated into the QM Hamiltonian, allowing the QM electron density to be polarized by the classical environment [5] [2]. This is a key feature of the method. - Selection of QM Method: Choose an appropriate QM method based on the reaction under study. Density Functional Theory (DFT) with functionals like B3LYP is a popular choice for ground-state reactions. For larger systems or when extensive sampling is required, semi-empirical methods (e.g., AM1, PM3) or density-functional tight-binding (DFTB) may be used [27].

- Geometry Optimization and Reaction Path Analysis:

- Optimize the structures of reactants, products, and putative intermediates.

- Locate the transition state(s) connecting these stationary points using techniques like the nudged elastic band (NEB) or quadratic synchronous transit (QST) methods.

- Validate transition states by confirming they have exactly one imaginary vibrational frequency along the reaction coordinate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software for QM/MM

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QM/MM Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MM Software Packages | AMBER [5], CHARMM [5], GROMOS | Provides force fields and engines for simulating the molecular mechanics (MM) region, including the protein scaffold and solvent. |

| QM Software Packages | GAMESS [5], Gaussian [5], CP2K, ORCA | Performs quantum mechanical calculations on the reactive region (e.g., active site). Handles electronic structure methods (DFT, HF, etc.). |

| Integrated QM/MM Suites & Interfaces | ChemShell [5], QoMMM [5], PUPIL [5] | Interface programs that connect standalone QM and MM packages, enabling complex multi-scale simulations. |

| Specialized QM/MM Modules | Built-in QM/MM in AMBER/CHARMM, ONIOM (in Gaussian) | Integrated environments within a single software package that simplify the setup and execution of QM/MM calculations. |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS [22] | Parameter sets defining MM energies (bond, angle, dihedral, non-bonded interactions) for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. |

| Analysis & Visualization | VMD, PyMOL, Jupyter Notebooks | Software for visualizing molecular structures, trajectories, and analyzing simulation data (e.g., energy components, reaction paths). |

| Aniline-MPB-amino-C3-PBD | Aniline-MPB-amino-C3-PBD, MF:C42H46N8O6, MW:758.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Axl-IN-5 | Axl-IN-5, MF:C31H35N5O2S, MW:541.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Contemporary Applications and Future Outlook

QM/MM methods have moved far beyond their initial application to lysozyme and are now routinely applied to a vast array of complex problems in biochemistry and drug discovery.

A major area of application is in understanding the mechanisms of enzymatic reactions, including the study of metalloenzymes like azurin, where the electronic structure of the metal active site is sensitive to its protein environment [5]. The approach is also critical for investigating energy transduction in biomolecular machines, such as long-range proton transport, electron transfers, and the coupling of nucleotide hydrolysis (e.g., in ATPase) to mechanical motion [27]. Furthermore, QM/MM has become a powerful tool in structure-based drug design, particularly for tackling "undruggable" targets and for designing covalent inhibitors where understanding the reaction mechanism is essential [28] [2]. It allows researchers to discriminate between alternative reaction mechanisms, understand the effects of mutations, and simulate free energies of enzyme-catalyzed reactions [2].

Future developments are poised to make QM/MM analyses even more quantitative and applicable to increasingly complex biological problems. Key areas of focus include:

- Integration of Polarizable Force Fields: Moving beyond fixed-charge MM models to explicitly include electronic polarization in the MM region, which is critical for accurately modeling buried charges and ion pairs [27].

- Balancing Cost and Sampling: Developing and applying efficiently calibrated semi-empirical QM methods (e.g., DFTB) and leveraging emerging quantum computing technologies to accelerate QM calculations, thereby enabling adequate conformational sampling for free energy calculations [28] [27].

- Machine Learning Potentials: Utilizing machine learning (ML) techniques to create accurate and highly efficient potential energy surfaces, which could dramatically accelerate QM/MM simulations [27].

QM/MM in Action: Methods, Software, and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

The application of quantum mechanical (QM) methods to biological systems represents a powerful approach for investigating phenomena that escape purely classical descriptions. Within the framework of mixed quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM), the accurate selection of the QM component is paramount to the success of the simulation. QM/MM methods have become indispensable tools for modeling enzymatic reaction mechanisms, ligand-protein interactions, and electronic properties of biomacromolecules where processes like charge transfer, bond breaking/formation, and electronic polarization are central [5] [4]. This application note provides a practical comparison of prevalent QM methods—Density Functional Theory (DFT), Hartree-Fock (HF), Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding (SCC-DFTB), and Semi-Empirical Molecular Orbital (SEMO) methods—focusing on their performance, limitations, and implementation protocols for biological systems research.

Theoretical Background and Key Performance Metrics

Fundamental Method Characteristics

Each QM method offers a distinct balance of computational cost and accuracy, rooted in its theoretical approximations.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) operates on the principle that the properties of a many-electron system can be determined via functionals of the electron density, thereby reducing the computational complexity associated with the many-electron wavefunction [29]. Modern DFT approaches, particularly Kohn-Sham DFT, map the system of interacting electrons onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons moving in an effective potential, which includes the external potential and the effects of electron-electron interactions (exchange and correlation) [29]. The accuracy of DFT hinges almost entirely on the approximation used for the exchange-correlation functional.

Hartree-Fock (HF) theory provides a wavefunction-based approach where the electron-electron repulsion is treated in an average way, neglecting instantaneous electron correlation effects. The HF method is the foundation for more accurate post-Hartree-Fock methods like Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) and coupled-cluster (CC) theory, which add electron correlation but at significantly increased computational cost [30] [4].

Semiempirical Methods (SEMO) of the Neglect of Diatomic Differential Overlap (NDDO) type, such as AM1, PM3, PM6, and PM7, use approximations to the HF method parameterized against experimental and high-level ab initio reference data [31] [32]. These methods are considerably faster than DFT or HF but their accuracy is contingent on the quality of their parameterization and the similarity of the system under study to the reference data used in parameterization.

Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding (SCC-DFTB) is an iterative extended Hückel theory method that utilizes a tight-binding approach to DFT, offering a compromise between semiempirical methods and full DFT [31].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The selection of an appropriate QM method requires a clear understanding of its performance for specific chemical properties. The following table summarizes quantitative data for geometry prediction, a critical property for biomolecular structure refinement and drug design.

Table 1: Performance of QM Methods for Geometric Parameter Prediction (Bond Lengths) in a Creatininium Model System

| Method Type | Specific Method | Mean Unsigned Error in Bond Length (Ã…) | Relative Performance Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Tier DFT | MPW1B95 | 0.0126 | 1 |

| PBEh | 0.0129 | 2 | |

| mPW1PW | 0.0133 | 3 | |

| Local DFT | SVWN5 | 0.0142 | 4 |

| Popular DFT | B3LYP | 0.0178 | 16 |

| Semiempirical | PM6 | >0.0178 | Less Accurate than 81% of DFT |

| Tight-Binding | SCC-DFTB | >0.0178 | Less Accurate than 81% of DFT |

Data adapted from a systematic validation study on creatininium cation geometries [31]. The study evaluated 21 density functionals and several SEMO methods against experimental X-ray structures. DFT significantly outperformed semiempirical methods for this dataset. The popular B3LYP functional was less accurate than the best local functional (SVWN5), which is computationally less expensive [31].

Practical Protocols for Method Selection and Application

Workflow for QM Method Selection and Validation

Implementing a QM/MM study requires a structured workflow to ensure reliability and mechanistic soundness. The following diagram outlines the critical decision points.

Detailed Protocol for QM/MM Setup and Execution

The protocol below details the steps for setting up and running a QM/MM simulation, with particular emphasis on the QM region treatment.

System Preparation and QM/MM Partitioning

- Obtain the initial structure from a reliable source (e.g., Protein Data Bank). Prepare the system using standard molecular modeling tools, adding missing atoms, hydrogen atoms, and solvating in a water box.

- Critical Step: Partition the system into QM and MM regions. The QM region should include the chemically active part (e.g., substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors). Care must be taken at the boundary where a covalent bond is cut. Use a link atom scheme (typically hydrogen atoms) to cap the valency of the QM region [5]. To mitigate overpolarization artifacts, ensure the MM partial charges of atoms adjacent to the link atoms are set to zero or handled with a specialized scheme like Generalized Hybrid Orbitals (GHO) [5].

Selection of QM Method and Basis Set

- Method Selection: Consult literature benchmarks for the specific chemistry involved (e.g., barrier heights, interaction energies).

- For general-purpose use where a good balance of cost and accuracy is needed, DFT with a hybrid functional like PBEh or B3LYP is a common starting point [31] [4].

- If dispersion interactions are critical, select a functional with empirical dispersion corrections (e.g., DFT-D3) [4].

- For very large systems requiring rapid sampling, consider Semiempirical Methods (PM6, PM7) or SCC-DFTB, but be aware of their lower general accuracy and validate their performance for your specific system [31] [32].

- Basis Set Selection: Use a polarized valence double-zeta basis set as a minimum requirement (e.g., 6-31G*). Diffuse functions are used less frequently in QM/MM due to potential artifacts from interactions with the MM environment; if needed, apply them only to atoms in the central QM region, far from the QM/MM boundary [4].

- Method Selection: Consult literature benchmarks for the specific chemistry involved (e.g., barrier heights, interaction energies).

Selection of QM/MM Scheme and Electrostatic Embedding

- Prefer additive QM/MM schemes for biological applications, as they do not require MM parameters for the QM region and offer a more explicit treatment [4]. The total energy is calculated as:

E_total = E_QM + E_MM + E_QM/MM. - The coupling term,

E_QM/MM, includes electrostatic, bonded, and van der Waals interactions [5]. - Employ electrostatic embedding, where the MM partial charges are included in the QM Hamiltonian. This allows the electron density of the QM region to be polarized by the classical environment, a critical effect for realism [4]. Avoid mechanical embedding for reactive processes.

- Prefer additive QM/MM schemes for biological applications, as they do not require MM parameters for the QM region and offer a more explicit treatment [4]. The total energy is calculated as:

Energy Minimization and Transition State Optimization

- Perform a careful minimization of the MM region, then the entire QM/MM system, before any dynamics or transition state search.

- For enzymatic reactions, locate the transition state using appropriate algorithms (e.g., micro-iterations, climbing-image Nudged Elastic Band). Validate transition states by confirming the existence of one imaginary frequency in the Hessian matrix.

Validation and Analysis

- Compare reaction energetics in the gas phase, aqueous solution, and the full enzyme environment. A competent level of theory should clearly show the catalytic effect of the protein environment [4].

- Analyze the electronic structure (e.g., via charge distributions, orbital interactions) to glean novel insights into the mechanism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Tools for QM/MM Simulations in Biomolecular Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAMESS | QM Software | Ab initio QM calculations (HF, DFT, MP2, CC) | Often coupled with MM packages via interfaces [5]. |

| Gaussian | QM Software | QM calculations, includes built-in MM capabilities | Widely used, but license is proprietary [5]. |

| AMBER | MM Software | Molecular dynamics with biomolecular force fields | Includes components for QM calculation; can be interfaced with GAMESS [5]. |

| CHARMM | MM Software | Molecular dynamics with biomolecular force fields | Comparable to AMBER in scope and application [5]. |

| ChemShell | QM/MM Interface | Environment for scripting QM/MM simulations | Connects various QM and MM packages (e.g., DL_POLY, GAMESS) [5]. |

| PUPIL | QM/MM Interface | Interface for multi-scale simulations | Enables interoperability between different simulation codes [5]. |

| PM7 | Semiempirical Method | Fast QM calculations for large systems | Improved for non-covalent interactions and solids vs. PM6 [32]. |

| MsbA-IN-4 | MsbA-IN-4|MsbA Inhibitor|Research Compound | MsbA-IN-4 is a potent MsbA transporter inhibitor for research use. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Trk-IN-11 | Trk-IN-11|Potent TRK Inhibitor|For Research Use | Trk-IN-11 is a potent TRK inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The choice of a QM method for biological applications is a trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy. DFT, particularly with carefully selected functionals and dispersion corrections, currently offers the best practical balance for modeling enzyme active sites and reaction mechanisms [31] [4]. Semiempirical methods and SCC-DFTB provide a necessary pathway for modeling very large systems or for extensive conformational sampling, though their results should be interpreted with caution and validated against higher-level theories or experiment [30] [31] [32].

Future developments in this field are poised to address several key challenges. The accurate and efficient inclusion of electron correlation effects, particularly for modeling dispersive interactions, remains a major hurdle [30]. Furthermore, while QM models excel at static modeling, incorporating QM-based sampling over biologically relevant timescales is an area of active research. Advances in linear-scaling algorithms and fragment-based methods (e.g., Divide-and-Conquer, FMO) will continue to push the boundaries of system size and complexity that can be treated with fully QM or QM/MM models, solidifying their role in biological and drug development research [30].

The integration of quantum mechanics (QM) with molecular mechanics (MM) has revolutionized computational studies of biological systems by combining the accuracy of electronic structure calculations with the efficiency of classical force fields. This hybrid approach is particularly valuable for investigating enzymatic reactions, drug-binding mechanisms, and spectroscopic properties of biomolecules where explicit treatment of electron transfer, bond breaking/formation, or excitation processes is essential. The QM/MM methodology enables researchers to study chemical reactions within their biological environments with unprecedented detail, providing insights that would be inaccessible through purely classical simulations.

The fundamental theoretical framework for QM/MM implementations partitions the system into a QM region, treated with quantum chemical methods, and an MM region, described by a molecular mechanics force field. The effective Hamiltonian for the combined system is generally expressed as:

[ H{eff} = H{QM} + H{MM} + H{QM/MM} ]

where (H{QM}) describes the quantum mechanical particles, (H{MM}) represents the molecular mechanical Hamiltonian independent of QM atoms, and (H{QM/MM}) accounts for interactions between the QM and MM regions [33] [34]. The (H{QM/MM}) term typically includes both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions, with the electrostatic component being particularly critical as it can polarize the QM electron density [35] [34].

Theoretical Foundations and Implementation Variants

Embedding Schemes and Electrostatic Coupling

Two primary embedding schemes dominate QM/MM implementations: mechanical embedding and electronic embedding. In mechanical embedding schemes, such as the ONIOM model implemented in Q-Chem, the total energy is calculated as:

[ E{total} = E{total}^{MM} - E{QM}^{MM} + E{QM}^{QM} ]

where (E{total}^{MM}) is the MM energy of the entire system, (E{QM}^{MM}) is the MM energy of the QM subsystem, and (E_{QM}^{QM}) is the QM energy of the QM subsystem [35]. While computationally efficient, this approach neglects polarization of the QM region by the MM environment.

Electronic embedding schemes, such as the Janus model in Q-Chem, provide a more physically realistic treatment by including MM point charges directly in the QM Hamiltonian:

[ E{total} = E{MM} + E_{QM} ]

where (E_{QM}) now includes the Coulomb potential between QM electrons/nuclei and MM atoms as external charges, allowing polarization of the QM electron density [35]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying excited states and charge transfer processes in biological environments.

Boundary Treatments and Link Atoms

A significant technical challenge in QM/MM simulations involves treating covalent bonds that cross the QM/MM boundary. Two predominant solutions exist: link atoms and the Generalized Hybrid Orbital (GHO) method. Link atoms, typically hydrogen atoms, are introduced to cap unsaturated valencies in the QM region [35]. The YinYang atom method extends this concept by creating a special atom that functions as a hydrogen cap in the QM calculation while participating in MM interactions, with a modified nuclear charge (q{nuclear} = 1 + q{MM}) to maintain charge neutrality [35].

Table 1: Comparison of QM/MM Boundary Treatments

| Method | Implementation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Link Atoms | CHARMM, Q-Chem | Simple implementation; Widely tested | Potential overpolarization; Artificial forces near boundary |

| YinYang Atoms | Q-Chem (Janus) | Charge conservation; Better boundary behavior | Limited to carbon link atoms in current implementations |

| GHO Method | CHARMM | More quantum mechanically rigorous | Increased computational complexity |

Software-Specific Implementations and Capabilities

CHARMM QM/MM Framework

CHARMM provides a robust QM/MM implementation with support for semi-empirical methods (AM1, PM3, MNDO) through its interface with MOPAC [33] [34]. The CHARMM implementation includes all essential components of the hybrid Hamiltonian: (H{QM}) for quantum particles, (H{MM}) for molecular mechanical atoms using CHARMM22 force field, (H{QM/MM}) for QM-MM interactions (electrostatic and van der Waals), and (H{brdy}) for boundary conditions [34].

Key features of CHARMM's QM/MM module include support for both mechanical and electronic embedding, options for configuration interaction calculations for excited states and biradicals, and flexibility in handling boundary conditions [34]. The software also implements the GHO method for more seamless treatment of covalent bonds crossing the QM/MM boundary.

Q-Chem's QM/MM Ecosystem

Q-Chem offers comprehensive QM/MM capabilities through both ONIOM (mechanical embedding) and Janus (electronic embedding) models [35]. The software supports a wide range of QM methods, from density functional theory (DFT) and Hartree-Fock to post-HF correlated wavefunctions and excited-state methods such as CIS and TDDFT [36] [35]. For the MM component, Q-Chem provides compatibility with AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA force fields [35].

A distinctive feature of Q-Chem's implementation is the availability of analytic QM/MM gradients for DFT and HF methods, enabling efficient geometry optimization and molecular dynamics simulations [35]. The software also supports implicit solvation using Polarizable Continuum Models (PCMs) within QM/MM calculations, Gaussian blurring of MM external charges to mitigate overpolarization issues, and periodic boundary conditions with Ewald summation [35].

AMBER and NAMD Integration

While the search results do not provide extensive details about AMBER and NAMD-specific implementations, both packages support QM/MM simulations through interfaces with external quantum chemistry codes. These implementations typically leverage the extensive classical force fields available in these packages while incorporating QM treatments for chemically active regions. The integration often focuses on enabling ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) and quasi-classical molecular dynamics (QMD) simulations for larger biological systems [36].

Practical Protocols for QM/MM Simulations

System Preparation and Partitioning

The initial and most critical step in any QM/MM simulation is the partitioning of the system into QM and MM regions. The QM region should include all chemically active components—reactive substrates, catalytic residues, cofactors, and key ligands—while the MM region encompasses the remaining protein scaffold and solvent environment. For CHARMM implementations, this partitioning is achieved through atom selection syntax:

For Q-Chem, the Janus model automatically handles YinYang atoms when bonds are cut, with carbon atoms (types 26, 35, and 47 in CHARMM27) recommended as optimal link atoms [35].

Electrostatic Embedding Protocol

For electronically embedded simulations in Q-Chem, the following protocol ensures proper polarization of the QM region:

- Specify the Janus model for electronic embedding

- Define MM atom types and parameters (AMBER, CHARMM, or OPLS-AA)

- Enable Gaussian blurring of MM external charges to prevent overpolarization

- Apply additional repulsive Coulomb potential between YinYang atoms and connecting QM atoms to maintain appropriate bond lengths [35]

Dynamics and Optimization Procedures

For QM/MM molecular dynamics simulations using CHARMM:

- Set SCF convergence criteria (SCFCriteria) appropriate for property accuracy

- Select analytical derivatives for efficiency (ANALYTical keyword)

- Disable QM/MM cutoffs if full electrostatic interactions are desired (NOCUtoff)

- Implement boundary conditions through pBOUNd or periodic options [34]

For geometry optimizations in Q-Chem:

- Utilize analytic QM/MM gradients for DFT or HF methods

- Employ appropriate implicit solvation models if reduced explicit solvent is used

- Verify convergence through multiple initial conditions for complex systems

Diagram 1: QM/MM Simulation Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the sequential steps for setting up and running QM/MM simulations across different software platforms.

Performance Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Computational Scaling and Efficiency