Revolutionizing Computational Chemistry: How Deep Learning Unlocks Hybrid DFT Accuracy

This article explores the transformative integration of deep learning with hybrid Density Functional Theory (DFT), a development poised to overcome the long-standing accuracy-cost trade-off that has limited computational chemistry and...

Revolutionizing Computational Chemistry: How Deep Learning Unlocks Hybrid DFT Accuracy

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of deep learning with hybrid Density Functional Theory (DFT), a development poised to overcome the long-standing accuracy-cost trade-off that has limited computational chemistry and drug discovery. We detail the foundational principles, including the critical challenge of the 'band-gap problem' in semi-local DFT and how hybrid functionals provide a solution. The article surveys cutting-edge deep learning methodologies, from equivariant neural networks for learning Hamiltonian matrices to end-to-end models for the exchange-correlation functional. For practitioners, we provide insights into troubleshooting data generation, model generalization, and computational bottlenecks. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of the new approaches against traditional methods, validating their performance on real-world applications in material science and drug design, and concluding with the profound implications for accelerating the discovery of new materials and therapeutics.

The Quantum Leap: From DFT's Band-Gap Problem to Hybrid Functionals

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as the most widely used computational method for predicting the ground-state energies, electron densities, and equilibrium structures of molecules and solids [1]. However, despite its widespread success, DFT suffers from a fundamental limitation known as the band-gap problem, which systematically underestimates the fundamental energy gap of semiconductors and insulators [2] [1]. This gap distinguishes insulators from metals and characterizes low-energy single-electron excitations, making its accurate prediction crucial for electronic and optoelectronic applications [1].

In theoretical terms, the fundamental band gap (G) is defined as a difference of ground-state energies: G = I(N) - A(N) = [E(N-1) - E(N)] - [E(N) - E(N+1)], where I(N) is the first ionization energy and A(N) is the first electron affinity of the neutral solid [1]. Within the Kohn-Sham (KS) formulation of DFT, the band gap (g) is calculated as the difference between the lowest-unoccupied (LU) and highest-occupied (HO) one-electron energies: g = εLU - εHO [1]. For the exact KS potential, these quantities differ by an exchange-correlation discontinuity: Gexact = gexact + Δxc [1]. However, commonly used local and semi-local approximations (LDA, GGA) lack this discontinuity, resulting in Gapprox = g_approx and a significant underestimation of experimental band gaps [1].

Table 1: Theoretical Framework of the DFT Band-Gap Problem

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Relationship | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Gap (G) | G = I(N) - A(N) = [E(N-1) - E(N)] - [E(N) - E(N+1)] | Represents true quasiparticle gap | Requires costly ΔSCF calculations |

| Kohn-Sham Gap (g_KS) | gKS = εLU - ε_HO | gKS = G - Δxc | Underestimates fundamental gap |

| XC Discontinuity (Δ_xc) | Δxc = δExc/δn │N+ - δExc/δn │_N- | Missing in LDA/GGA | Cause of systematic underestimation |

The band-gap problem has profound implications for materials research. It hinders the reliable application of DFT to predict electronic properties and is intimately related to self-interaction and delocalization errors, which complicate the study of charge transfer mechanisms [3]. Overcoming this limitation is essential for advancing computational materials design, particularly for electronic materials, photovoltaic applications, and semiconductor devices.

Quantitative Analysis of Band-Gap Performance

The performance of various DFT approximations can be quantitatively assessed by comparing their predicted band gaps against experimental measurements. Hybrid functionals, which incorporate a portion of non-local Fock exchange, have demonstrated remarkable improvements in band gap accuracy across diverse classes of materials.

Table 2: Performance of Computational Methods for Band Gap Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Typical RMSE/MAE (eV) | Computational Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE/GGA | Semi-local functional, gapprox = Gapprox | ~1.0 eV (severe underestimation) | Low | No derivative discontinuity, delocalization error |

| DFT+U | Adds Hubbard correction to specific orbitals | Varies by material (requires parameter tuning) | Low to moderate | System-dependent U parameters, empirical nature |

| HSE Hybrid | Screened hybrid functional (25% HF exchange) | ~0.3 eV [2] | High | Still expensive for large systems |

| B3LYP Hybrid | Global hybrid functional (20% HF exchange) | Close to experimental gaps [4] | High | Performance varies across material classes |

| G0W0@PBE | Many-body perturbation theory | 0.24-0.45 eV [2] | Very high | Computational cost prohibitive for high-throughput |

Extensive benchmarking studies have established the superior performance of hybrid functionals. The B3LYP hybrid functional has demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting band gaps for a wide variety of materials including semiconductors (Si, diamond, GaAs), semi-ionic oxides (ZnO, Al2O3, TiO2), sulfides (FeS2, ZnS), and transition metal oxides (MnO, NiO), with agreement typically within experimental uncertainty margins [4]. The HSE functional has also shown excellent performance, becoming the standard for accurate band gap prediction in solid-state systems [2].

The accuracy of hybrid functionals stems from their operation within the generalized Kohn-Sham (gKS) framework, where the band gap of an extended system equals the fundamental gap for the approximate functional if the gKS potential operator is continuous and the density change is delocalized when an electron or hole is added [1]. This theoretical foundation explains why hybrid functional band gaps can be more realistic than those from GGAs or even from the exact KS potential [1].

Protocols for Hybrid Functional Band Structure Calculations

Workflow for Hybrid Functional Band Structure Calculations

Step-by-Step Protocol for VASP Calculations

Step 1: Initial DFT Calculation

- Run a self-consistent field (SCF) calculation using a standard GGA functional (e.g., PBE) to obtain a converged WAVECAR file [5].

- Use a regular k-mesh (e.g., Monkhorst-Pack 3×3×3 for silicon) specified in the KPOINTS file [5].

- This step provides the initial wavefunctions necessary for the subsequent hybrid calculation.

Step 2: Determine High-Symmetry Path

- Identify high-symmetry points in the first Brillouin zone appropriate for your crystal structure [5].

- Define the connecting path along which the band structure will be calculated [5].

- External tools such as SeekPath or VASPKIT can help generate the appropriate k-path [5].

Step 3: KPOINTS File Preparation Two methods are available for supplying k-points:

Method A: Explicit List with Zero-Weighted K-Points

- Copy the irreducible k-points from the IBZKPT file of the SCF calculation [5].

- Add k-points along the high-symmetry path with weights set to zero [5].

- Example for silicon Γ to X path:

Method B: KPOINTS_OPT File

- Keep the regular k-mesh in the KPOINTS file [5].

- Create a separate KPOINTS_OPT file specifying the high-symmetry path in line-mode [5].

- Example KPOINTS_OPT for silicon:

Step 4: Hybrid Functional Settings

- Set HFRCUT = -1 in the INCAR file for Coulomb truncation, which prevents discontinuities in band structure calculations [5].

- Critical: Never set ICHARG = 11 for hybrid calculations, as the electronic charge density must not be fixed [5].

- Restart the hybrid calculation from the DFT WAVECAR file [5].

Step 5: Band Structure Plotting

- After convergence, plot the band structure using tools like py4vasp [5]:

Technical Recommendations

- Computational Efficiency: For systems with many k-points along the high-symmetry path, use the KPOINTSOPTNKBATCH tag to control memory usage, or split the calculation with subsets of zero-weighted k-points [5].

- Convergence: When using the explicit k-points list method, avoid restarting from a converged hybrid WAVECAR file to ensure proper convergence of all k-points [5].

- Validation: Test your workflow with a DFT calculation first to familiarize yourself with the process before proceeding to more computationally expensive hybrid calculations [5].

Machine Learning Approaches to Overcome Computational Limitations

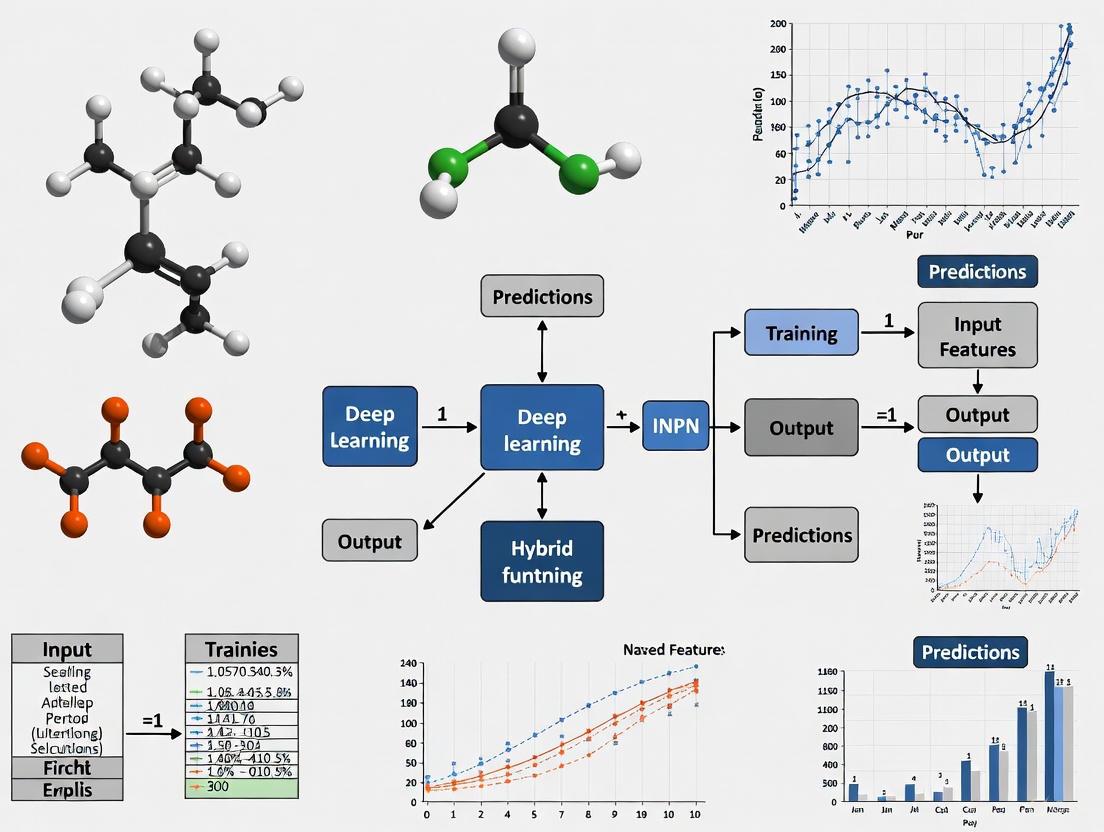

Conceptual Framework of ML-Enhanced Electronic Structure

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful approach to overcome the computational limitations of hybrid functional calculations while maintaining accuracy [6] [2]. The DeepH-hybrid method exemplifies this approach, using deep equivariant neural networks to learn the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian as a function of material structure, circumventing the expensive self-consistent field iterations [6]. This enables large-scale materials studies with hybrid-functional accuracy, as demonstrated in applications to Moiré-twisted materials like magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene [6].

ML Correction Methods for Band Gaps

Various ML approaches have been developed to correct DFT band gaps:

Feature-Based Band Gap Correction

- Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models can correct PBE band gaps to G0W0 accuracy using a minimal set of five features: Eg_PBE, 1/r (volume per atom measure), average oxidation states, electronegativity, and minimum electronegativity difference [2].

- These models achieve test RMSE of ~0.25 eV, effectively bridging the gap between DFT and more accurate methods [2].

Machine-Learned Density Functionals

- ML can design functionals based on Gaussian processes explicitly fitted to single-particle energy levels [3].

- Incorporating nonlocal features of the density matrix enables accurate prediction of molecular energy gaps and reaction energies in agreement with hybrid DFT references [3].

- Such models demonstrate transferability, predicting reasonable formation energies of polarons in solids despite being trained solely on molecular data [3].

Integration with DFT+U Framework

- ML models can identify optimal (Up, Ud/f) parameter pairs for DFT+U calculations that closely reproduce experimental band gaps and lattice parameters [7].

- Simple supervised ML models can reproduce DFT+U results at a fraction of the computational cost and generalize well to related polymorphs [7].

Protocol for ML-Based Band Gap Correction

Data Collection and Feature Engineering

- Collect a diverse dataset of materials with known experimental or high-accuracy computational band gaps [2].

- Compute PBE band gaps and structural properties for all materials [2].

- Calculate or obtain elemental features: oxidation states, electronegativity, minimum electronegativity difference [2].

- Compute volume-related feature: 1/r, where r relates to volume per atom [2].

Model Training and Validation

- Select appropriate ML model: Gaussian Process Regression with Matern 3/2 kernel has shown excellent performance [2].

- Implement cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) to prevent overfitting and ensure model generalizability [2].

- For neural network approaches, utilize E(3)-equivariant architectures to preserve physical constraints [6].

Application to New Materials

- For new materials, perform standard PBE calculation to obtain Eg_PBE and structural information [2].

- Compute additional features from composition and structure [2].

- Apply trained ML model to predict corrected band gap [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Advanced Electronic Structure Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Software | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | VASP, CRYSTAL, Quantum ESPRESSO | Solve Kohn-Sham equations with various functionals | Ground-state calculations, band structures, density of states |

| Hybrid Functionals | HSE, B3LYP, PBE0 | Mix Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation | Accurate band gaps, improved electronic properties |

| Beyond-DFT Methods | GW, BSE, DMFT | Many-body perturbation theory, dynamical mean-field theory | Quasiparticle excitations, strongly correlated systems |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | DeepH-hybrid, Gaussian Process Regression | Learn electronic structure from reference calculations | Large-scale screening, band gap correction, Hamiltonian prediction |

| Post-Processing & Visualization | py4vasp, VESTA, p4vasp | Analyze and visualize computational results | Band structure plots, charge density visualization |

The development of DeepH-hybrid represents a significant advancement in this toolkit, generalizing deep-learning electronic structure methods beyond conventional DFT and facilitating the development of deep-learning-based ab initio methods [6]. This approach benefits from the preservation of the nearsightedness principle on a localized basis, enabling accurate modeling of hybrid functional Hamiltonians while maintaining computational efficiency [6].

For researchers investigating the band-gap problem, the integration of traditional electronic structure methods with modern machine learning approaches provides a powerful framework for achieving both accuracy and computational efficiency. The protocols outlined in this document offer practical guidance for implementing these advanced methods in materials research, particularly in the context of deep learning for hybrid density functional calculations.

Hybrid density functionals represent a pivotal advancement in density functional theory (DFT) by incorporating a fraction of exact, nonlocal Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange into semi-local exchange-correlation functionals. This integration directly addresses one of the most significant limitations of traditional DFT: the band gap problem, where local (LDA) and semi-local (GGA) approximations systematically underestimate the band gaps of semiconductors and insulators [8]. The general formula for hybrid functionals can be expressed as:

Exchybrid = aSR Ex,SRHF(μ) + aLR Ex,LRHF(μ) + (1 - aSR)Ex,SRSL(μ) + (1 - aLR)Ex,LRSL(μ) + EcSL

where aSR and aLR are mixing parameters for the short-range (SR) and long-range (LR) HF exchange, μ is a screening parameter, and SL denotes the semilocal functional [9]. The inclusion of exact exchange within the generalized Kohn-Sham framework reduces the self-interaction error and provides a more physically grounded description of electronic structure, making hybrid functionals indispensable for reliable predictions in (opto-)electronics, spintronics, and drug discovery [6].

Key Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Quantum Computing in Prodrug Activation

In pharmaceutical research, hybrid functionals and quantum computing methods are applied to model critical reaction pathways. A prominent example is the study of a carbon-carbon (C–C) bond cleavage prodrug strategy for β-lapachone, an anticancer agent. Accurate calculation of the Gibbs free energy profile for this covalent bond cleavage is crucial to determine if the reaction proceeds spontaneously under physiological conditions, guiding molecular design and evaluating dynamic properties [10].

The quantum computational protocol for this involves:

- Active Space Approximation: The complex molecular system is simplified to a manageable two-electron/two-orbital model for simulation on quantum devices.

- Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm employs a hardware-efficient ( R_y ) ansatz with a single layer as a parameterized quantum circuit.

- Solvation Effects: Single-point energy calculations incorporate water solvation effects using models like the polarizable continuum model (PCM) to mimic the physiological environment [10].

This application demonstrates the potential of quantum computing to enhance the accuracy of reaction modeling in drug design, moving beyond classical DFT limitations.

Electronic Properties of Alkaline-Earth Metal Oxides

Hybrid functionals provide superior accuracy for materials with strongly correlated and localized electrons, such as alkaline-earth metal oxides (MgO, CaO, SrO, BaO). These materials, with their rock-salt crystal structure and localized d-orbitals, are poorly described by conventional LDA or GGA functionals due to significant self-interaction error [8].

Table 1: Performance of Hybrid Functionals for Alkaline-Earth Metal Oxides

| Functional | Performance for Lattice Constant | Performance for Band Gap |

|---|---|---|

| PBE0 | Best functional for estimation | Best functional for estimation |

| B3PW91 | Best functional for estimation | Excellent |

| LDA-HF (α = 0.35) | Slight increase over LDA | Significant improvement over LDA |

| LDA-Fock (α = 0.5) | Slight increase over LDA | Further improvement, may overcorrect |

Extensive first-principles calculations show that hybrid functionals like PBE0 and B3PW91 yield excellent agreement with experimental data for both lattice constants and band gaps, successfully overcoming the limitations of semi-local functionals [8].

Deep Learning for Accelerating Hybrid Functional Calculations

The primary drawback of hybrid functionals is their substantial computational cost, which traditionally restricts their application to systems containing hundreds of atoms. The computation of the non-local exact-exchange potential is particularly demanding, involving two-electron Coulomb repulsion integrals over quartets of basis functions [6].

The DeepH-Hybrid Method

The DeepH-hybrid method represents a groundbreaking approach that uses deep equivariant neural networks to learn the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian as a function of atomic structure, bypassing the need for costly self-consistent field (SCF) iterations [6].

The methodology leverages the nearsightedness principle, which holds even for the non-local exchange potential. On a localized basis, the Hamiltonian matrix element between atoms i and j is predominantly determined by the local atomic environment within a cutoff radius, making it amenable to machine learning [6] [11].

Table 2: Key Components of the DeepH-Hybrid Workflow

| Component | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Equivariant Neural Networks | Map atomic structure {R} to Hamiltonian H({R}) |

Preserves geometric symmetries (E(3) equivariance) |

| Localized Basis Set | Basis for Hamiltonian representation (e.g., pseudo-atomic orbitals) | Ensures nearsightedness and efficient learning |

| Cutoff Radius (R_c) | Defines the local atomic environment for each matrix element | Transforms global problem into localized learning tasks |

This approach has been successfully applied to study Moiré-twisted materials like magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene, enabling hybrid-functional accuracy for systems exceeding 10,000 atoms [6] [11].

Diagram 1: Traditional vs. DeepH-Hybrid Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Quantum Computing for Prodrug Activation Energy

Objective: Calculate the Gibbs free energy profile for C–C bond cleavage in a β-lapachone prodrug using a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm [10].

System Preparation:

- Select key molecular structures along the reaction coordinate for bond cleavage.

- Perform conformational optimization using classical methods.

- Define the active space (2 electrons in 2 orbitals) for the quantum computation.

Quantum Computation Setup:

- Ansatz Preparation: Employ a hardware-efficient ( R_y ) ansatz with a single layer.

- VQE Execution: Use the Variational Quantum Eigensolver to find the ground state energy.

- The quantum processor prepares and measures the trial state.

- A classical optimizer minimizes the energy expectation value.

- Error Mitigation: Apply readout error mitigation techniques.

Solvation Energy Calculation:

- Perform single-point energy calculations on the optimized structures.

- Incorporate solvation effects using a polarizable continuum model (PCM) to simulate water.

Energy Profile Construction:

- Compute the energy difference between reactants, transition states, and products.

- The energy barrier is derived from the difference between the transition state and reactant energies.

Diagram 2: Quantum Chemistry in Drug Discovery

Protocol: DeepH-Hybrid for Large-Scale Materials

Objective: Perform electronic structure calculation for a large-scale material (e.g., twisted bilayer graphene) with hybrid-functional accuracy [6] [11].

Dataset Generation:

- Use an ab initio code (e.g., HONPAS with HSE06 functional) to compute Hamiltonians for a diverse set of small, representative atomic structures.

- The dataset should encompass various chemical environments expected in the target large system.

Model Training:

- Train an equivariant neural network (DeepH-hybrid) to predict the Hamiltonian

H({R})from the atomic structure{R}. - The training loss function minimizes the difference between the predicted and ab initio Hamiltonian matrices.

- Train an equivariant neural network (DeepH-hybrid) to predict the Hamiltonian

Inference for Large Systems:

- Input the atomic structure of the large-scale system (e.g., a Moiré supercell with >10,000 atoms) into the trained DeepH-hybrid model.

- The model directly outputs the Hamiltonian without SCF iterations.

Property Calculation:

- Diagonalize the predicted Hamiltonian to obtain the band structure and density of states.

- Analyze electronic properties such as band gaps and orbital projections.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Hybrid Functional Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Planewave-based DFT code with hybrid functional support [9] | Materials science simulations for periodic systems |

| HONPAS | DFT software with efficient HSE06 implementation and NAO2GTO method [11] | Large-scale hybrid functional calculations for materials |

| TenCirChem | Quantum computational chemistry package [10] | Quantum computing simulations for drug discovery (e.g., VQE) |

| IonQ Forte (Amazon Braket) | Trapped-ion quantum computer [12] | Hardware for running quantum circuits in hybrid algorithms |

| NVIDIA CUDA-Q | Hybrid quantum-classical computing platform [12] | Integration and execution of quantum-classical workflows |

| 6-311G(d,p) Basis Set | High-accuracy Gaussian basis set [10] | Quantum chemistry calculations for molecular systems |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) | Implicit solvation model [10] | Simulating solvent effects in biochemical reactions |

| DeepH-Hybrid Software | Machine learning for Hamiltonian prediction [6] | Bypassing SCF iterations in large-scale hybrid DFT calculations |

In the pursuit of accurate materials discovery and drug development, hybrid density functional theory (DFT) has emerged as a crucial methodological advancement beyond generalized gradient approximation (GGA). While standard GGA functionals like PBE provide reasonable computational efficiency, they face severe accuracy limitations for systems with localized electronic states, particularly transition-metal oxides that are ubiquitous in catalytic and energy applications. Hybrid functionals, such as HSE06, incorporate a portion of exact Hartree-Fock exchange, significantly improving predictive accuracy for electronic properties critical to materials science and molecular chemistry. However, this increased accuracy comes at a substantial computational premium—often one to two orders of magnitude greater than standard GGA calculations. This application note examines the precise origins of this computational bottleneck, provides quantitative assessment data, and outlines protocols for researchers navigating this challenging landscape within deep learning frameworks for materials informatics.

Table: Comparative Analysis of DFT Functional Performance and Computational Demand

| Functional Type | Representative Functional | Band Gap MAE (eV) | Relative Computational Cost | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE | 1.35 (Borlido et al. benchmark) | 1× (baseline) | High-throughput screening, structural properties |

| Hybrid | HSE06 | 0.62 (Borlido et al. benchmark) | 10-100× | Accurate electronic properties, band gaps, catalytic materials |

Quantitative Analysis of the Hybrid Functional Computational Burden

Fundamental Algorithmic Complexities

The prohibitive cost of hybrid functional calculations stems from intrinsic algorithmic complexities that fundamentally differ from semilocal functionals:

Non-local Exchange Computation: Unlike GGA functionals that depend only on local electron density and its gradient, hybrid functionals incorporate Hartree-Fock exchange that requires evaluation of electronic interactions across all space. This transformation of the computational problem from O(N) to O(N²–N⁴) depending on implementation creates an immense scaling penalty for large systems.

Basis Set Requirements: All-electron hybrid calculations with numerical atomic orbitals require sophisticated "tier" basis sets to achieve convergence, with the "light" settings providing only a compromise between accuracy and computational feasibility [13]. More accurate "tight" or "really tight" settings can increase computational load by additional factors of 3-10×.

Convergence Challenges: Hybrid functional calculations, particularly for systems containing 3d- or 4f-elements, exhibit notoriously difficult convergence behavior due to heightened sensitivity to localized states. In high-throughput studies, approximately 2.8% of materials (167 of 7,024) failed HSE06 convergence entirely, necessitating case-specific parameter tuning that defies automation [13].

Empirical Benchmarking Data

Recent benchmarking of the FHI-aims code reveals the concrete performance implications of hybrid functional adoption:

Processor Performance Variance: Comparative analysis across modern processor architectures demonstrates significant performance differentials, with AMD EPYC, NVIDIA GRACE, and Intel processors performing similarly while the A64FX lagged by nearly an order of magnitude for equivalent calculations [14].

Memory and Scaling Limitations: The memory footprint of hybrid calculations grows quadratically with system size, creating practical limits on investigable system sizes. For the 7,024-material database generation, unit cells up to 616 atoms required substantial computational resources despite efficiency compromises [13].

Table: Hardware Performance Benchmark for Hybrid DFT Calculations (FHI-aims Code)

| Processor | Compiler | Relative Performance | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD EPYC | GNU/Intel | Baseline (1×) | General high-throughput workflows |

| NVIDIA GRACE | GNU | Comparable to AMD EPYC | Emerging hybrid architectures |

| A64FX | ARM/GNU | 0.1× (order of magnitude slower) | Specialized applications only |

Experimental Protocols for Hybrid Functional Calculations

Workflow for High-Throughput Hybrid Database Generation

The creation of reliable training data for deep learning models requires meticulous protocol design to balance accuracy with computational feasibility:

Figure 1: High-throughput computational workflow for hybrid functional materials database generation.

Step 1: Initial Structure Selection and Filtering

- Query initial crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD, v2020)

- Filter duplicate entries or polymorphs by associating each ICSD-id with a Materials Project ID (MP-id)

- Apply lowest energy/atom criteria according to MP (GGA/GGA+U) data for structure selection

- For formulas without MP-id, select the ICSD entry with the fewest atoms in the unit cell

- Impose no restrictions on unit cell sizes, accommodating structures with up to 616 atoms/unit cell

Step 2: Geometry Optimization Protocol

- Perform structural relaxation using the PBEsol functional

- Utilize "light" numerical atomic orbital (NAO) basis sets in FHI-aims

- Set force convergence criterion to 10⁻³ eV/Å

- Conduct spin-polarized calculations for all potentially magnetic structures (labeled magnetic in MP or containing Fe, Ni, Co, etc.)

- Employ Taskblaster framework for workflow automation

Step 3: Hybrid Functional Electronic Structure Calculation

- Execute single-point HSE06 energy evaluations on PBEsol-optimized structures

- Compute electronic properties: band structure, density of states, Hirshfeld charges

- Maintain consistent "light" NAO basis set configuration

- For non-convergent systems (particularly with 3d-/4f-elements), implement denser k-point sampling or manual parameter adjustment

Validation and Quality Control Measures

Data Validation Protocol:

- Compare formation energies and band gaps between PBEsol and HSE06 functionals

- Calculate mean absolute deviation (MAD) metrics: target ~0.15 eV/atom for formation energies, ~0.77 eV for band gaps

- Construct convex hull phase diagrams for representative binary (Li-Al) and ternary (Co-Pt-O) systems

- Benchmark against experimental data where available (e.g., Borlido et al. dataset)

Error Handling:

- Document convergence failures explicitly (198 materials in reference database)

- Flag materials with discrepant magnetic ordering or spin configurations between functionals

- Implement fallback procedures for problematic systems, potentially reverting to GGA+U approaches

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for Hybrid Calculations

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | FHI-aims | All-electron DFT code with hybrid functional capability | Electronic structure calculation with NAO basis sets [13] |

| Workflow Tools | Taskblaster Framework | Automation of high-throughput calculation workflows | Orchestrates geometry optimization and property calculation steps [13] |

| Computational Resources | NVIDIA CUDA-Q Platform | Hybrid quantum-classical computing environment | Integration of quantum-ready methods into HPC workflows [15] |

| Data Management | NOMAD Archive | Repository for electronic structure data | FAIR data sharing and dissemination [13] |

| Analysis Frameworks | SISSO Approach | AI model training for material properties | Symbolic regression for interpretable structure-property relationships [13] |

Emerging Strategies: Mitigating the Hybrid Functional Bottleneck

Deep Learning Surrogate Models

The integration of deep learning with hybrid functional data represents the most promising path toward overcoming current computational limitations:

Transfer Learning Approaches: Utilize the substantial GGA-calculated materials databases (Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW) as pretraining foundations, with fine-tuning on targeted hybrid functional data for improved accuracy.

Multi-fidelity Learning: Develop models that incorporate both low-fidelity (GGA) and high-fidelity (hybrid) data to reduce the required number of expensive hybrid calculations while maintaining predictive accuracy.

SISSO Implementation: Apply the Sure-Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator approach to identify compact, interpretable descriptors derived from hybrid functional data, enabling rapid materials screening without continual DFT reevaluation [13].

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computational Strategies

Recent advances in quantum computing offer potential long-term solutions to the hybrid functional bottleneck:

Figure 2: Hybrid quantum-classical computational workflow for electronic structure problems.

Variational Quantum Linear Solver (VQLS): Implementation that reduces quantum circuit size, optimizes qubit usage, and decreases trainable parameters for matrix-based problems in computational fluid dynamics and digital twin applications [15].

Error-Mitigated Dynamic Circuits: Combination of multiple quantum processors via real-time classical links to create effectively larger quantum systems, recently demonstrated with 142 qubits across two quantum processing units [16].

Quantum Subspace Methods: Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) and Quantum Self-Consistent Equation-of-Motion (q-sc-EOM) protocols for molecular excited state calculations, with demonstrated robustness to sampling errors inherent in quantum measurements [17].

The computational expense of hybrid density functional calculations remains a significant bottleneck in the development of accurate deep learning models for materials science and drug discovery. While the superior accuracy of hybrid functionals for critical electronic properties is unequivocal, their widespread application is presently constrained by computational demands that are 10-100× greater than standard GGA approaches. Strategic pathways forward include the careful construction of targeted hybrid functional databases for specific materials classes, the development of sophisticated multi-fidelity machine learning models that maximize information extraction from limited high-quality data, and continued investment in emerging computational paradigms such as hybrid quantum-classical algorithms. Through coordinated application of these strategies, the materials research community can progressively overcome the current limitations and realize the full potential of predictive computational materials design.

The accuracy of density functional theory (DFT) is paramount for reliable material predictions, particularly in fields like electronics and drug development where understanding electronic properties is crucial. While conventional DFT methods are computationally efficient, they suffer from a well-documented band-gap problem, systematically underestimating band gaps and limiting their predictive power for electronic materials. Hybrid density functionals, which incorporate a portion of exact (Hartree-Fock) exchange, largely resolve this issue but introduce a significant computational bottleneck: the treatment of the non-local exchange potential [6].

This non-local potential, defined in real space as ( V_{\text{Ex}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}') ), fundamentally differs from the local potentials found in semi-local DFT. In a localized basis set representation, the calculation of this exact exchange term involves computationally expensive four-center integrals, (( \mathbf{ik} | \mathbf{lj} )), whose number grows rapidly with system size. This makes hybrid functional calculations considerably more expensive than their semi-local counterparts, restricting their application in large-scale materials simulations such as complex molecular systems or extended solid-state materials relevant to pharmaceutical and materials development [6]. This application note details how deep learning methods are overcoming this fundamental challenge, enabling hybrid-functional accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost.

Quantitative Comparison of Computational Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of traditional and emerging deep-learning approaches for handling the non-local exact-exchange potential, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for Exchange-Correlation Potentials

| Method | Form of Exchange Potential | Computational Scaling | Band Gap Accuracy | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-Local DFT (LDA/GGA) | Local: ( V_{\text{xc}}(\mathbf{r})\delta(\mathbf{r}-\mathbf{r}') ) | Favorable | Poor (Systematic underestimation) | Delocalization error, band-gap problem [6] |

| Traditional Hybrid DFT (HSE) | Non-local: ( V_{\text{xc}}^{\text{hyb}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{r}') ) [6] | High (4-center integrals) | High | Prohibitive cost for large systems [6] |

| Kernel Density Functional (KDFA) | Pure, non-local [18] | Mean-field cost (like semi-local DFT) | High (for molecules) | Validation in solid-state systems ongoing [18] |

| DeepH-hybrid | Learned non-local ( H_{\text{DFT}}^{\text{hyb}}({\mathcal{R}}) ) [6] | Low (once model is trained) | Hybrid-DFT accuracy | Requires training data and model development [6] |

| NextHAM | Learned correction ( \Delta \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{H}^{(T)} - \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ) [19] | Low (once model is trained) | DFT-level precision | Generalization across diverse elements and structures [19] |

Deep Learning Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The DeepH-hybrid Workflow for Non-Local Hamiltonian Learning

The DeepH-hybrid method generalizes the deep-learning Hamiltonian approach to achieve hybrid-functional accuracy. The following protocol outlines the key steps for model development and application [6].

Step 1: Data Generation and Hamiltonian Target Definition

- Perform self-consistent hybrid-DFT calculations (e.g., using HSE functional) on a diverse set of training material structures using ab initio codes.

- Extract the target Hamiltonian, ( H_{\text{DFT}}^{\text{hyb}}({\mathcal{R}}) ), which includes the non-local exact-exchange component, from the converged calculations.

- The training dataset must encompass a variety of atomic structures and chemical environments to ensure model transferability.

Step 2: Input Feature Engineering with Nearsightedness Principle

- For a given atomistic structure ( {\mathcal{R}} ), the Hamiltonian matrix block ( H_{ij} ) between atoms i and j is constructed.

- Adhere to the nearsightedness principle: ( H{ij} ) is non-zero only if the atomic distance ( r{ij} ) is below a cutoff radius ( R_C ).

- The value of ( H{ij} ) is determined solely by the local atomic environment within a nearsightedness length ( RN ) from atoms i and j. This drastically reduces the complexity of the learning problem by leveraging the locality of electronic interactions, even for the non-local exact exchange [6].

Step 3: Model Training with E(3)-Equivariant Neural Networks

- Employ a deep E(3)-equivariant neural network to model the Hamiltonian as a function of the material structure. This architecture ensures that model predictions are invariant to translations, rotations, and inversions of the input structure, a fundamental physical requirement.

- The network learns the mapping:

Atomic Structure → Hamiltonian Matrix \( H_{\text{DFT}}^{\text{hyb}} \). - The loss function is designed to minimize the difference between the predicted and ab initio computed Hamiltonian matrices.

Step 4: Model Validation and Application

- Validate the trained model on unseen test structures by comparing its predicted electronic structures (band gaps, densities of states) and energies with hybrid-DFT results.

- Apply the model to large-scale systems (e.g., Moiré-twisted bilayers), directly predicting the Hamiltonian without self-consistent field iterations, thus bypassing the most computationally expensive step of traditional hybrid-DFT [6].

Figure 1: The DeepH-hybrid workflow for learning the non-local hybrid-functional Hamiltonian from material structures, enabling large-scale simulations.

Protocol 2: The NextHAM Correction Scheme for Universal Prediction

The NextHAM framework introduces a correction-based approach to simplify the learning task and improve generalization across the periodic table, which is critical for simulating diverse molecular systems in drug development [19].

Step 1: Compute Zeroth-Step Hamiltonian as a Physical Descriptor

- For a given atomic structure, compute the zeroth-step Hamiltonian, ( \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ).

- This quantity is constructed efficiently from the initial electron density, ( \rho^{(0)}(\mathbf{r}) ), which is typically a simple sum of isolated atomic charge densities. Its calculation does not require the expensive matrix diagonalization of a self-consistent field procedure [19].

Step 2: Define the Learning Target as a Correction

- Instead of learning the final, self-consistent Hamiltonian ( \mathbf{H}^{(T)} ) directly, the neural network is trained to predict the correction term ( \Delta \mathbf{H} = \mathbf{H}^{(T)} - \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ).

- This strategy significantly reduces the complexity and dynamic range of the model's output space, facilitating more accurate and stable learning [19].

Step 3: Implement an Expressive E(3)-Equivariant Transformer

- Utilize a neural Transformer architecture that strictly enforces E(3)-symmetry (equivariance to rotations, etc.) while maintaining high non-linear expressiveness.

- The model takes the atomic structure and the ( \mathbf{H}^{(0)} ) descriptor as input and outputs the predicted ( \Delta \mathbf{H} ).

Step 4: Joint Optimization in Real and Reciprocal Space

- Train the model using a joint loss function that optimizes the accuracy of the Hamiltonian in both real space (R-space) and reciprocal space (k-space).

- This dual-space optimization is critical for preventing error amplification and ensuring the accuracy of derived electronic properties like band structures, which are calculated in k-space. It specifically mitigates issues caused by the large condition number of the overlap matrix [19].

Figure 2: The NextHAM correction framework, using a physically-informed initial Hamiltonian to simplify the learning of the target electronic structure.

This section catalogues the essential computational tools, data, and models that form the modern toolkit for developing deep learning solutions to the non-local exchange challenge.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Deep-Learning Hybrid-DFT Research

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Training Datasets (e.g., Materials-HAM-SOC) | Benchmark Data | Provides diverse, high-quality Hamiltonian data spanning many elements for training and evaluating generalizable models [19]. |

| E(3)-Equivariant Neural Networks (e.g., DeepH-E3, QHNet) | Algorithm/Model | Core architecture for learning Hamiltonian mappings; ensures predictions respect physical symmetry laws [19]. |

| Density-Fitting (DF) Basis Sets | Computational Method | Enables a compact, atom-centered representation of the electron density, crucial for efficient ML-based density functionals [18]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | Machine Learning Method | A data-efficient ML approach used to learn non-local correlation energy functionals from wavefunction reference data [18]. |

| Zeroth-Step Hamiltonian (( \mathbf{H}^{(0)})) | Physical Descriptor | An efficient-to-compute initial guess of the Hamiltonian that provides rich physical prior knowledge, simplifying the neural network's learning task [19]. |

| Transfer Learning & Pre-trained Models (e.g., DP-GEN) | Methodology/Model | Leverages knowledge from pre-trained models on large datasets, allowing for accurate new models with minimal additional data [20]. |

| Ab Initio Software (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, etc.) | Software | Generates the ground-truth data (Hamiltonians, energies, forces) required for supervised learning of neural network potentials and models [6]. |

Deep Learning Architectures for Hybrid DFT: From Theory to Practice

Hybrid density functional theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone for accurate electronic structure prediction, indispensable for research in (opto-)electronics, spintronics, and topological electronics [6]. Its primary advantage over conventional semi-local DFT is the significant mitigation of the "band-gap problem," achieved by incorporating a fraction of non-local, exact Hartree-Fock exchange [6]. However, the formidable computational cost associated with calculating this exact exchange has severely restricted its application to large-scale materials [6] [11].

The DeepH-hybrid method represents a transformative approach to this long-standing challenge. By leveraging deep equivariant neural networks, it learns the mapping from a material's atomic structure directly to its hybrid-functional Hamiltonian [6] [21]. This bypasses the computationally expensive self-consistent field (SCF) iterations that dominate the cost of traditional hybrid-DFT calculations [11]. The method generalizes the successful deep-learning Hamiltonian (DeepH) approach, previously confined to conventional Kohn-Sham DFT, to the generalized Kohn-Sham (gKS) scheme of hybrid functionals [6]. This advancement facilitates highly efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations for large-scale systems, opening new avenues for material simulation with hybrid-functional accuracy.

Computational Methodology

Core Theoretical Foundation

The DeepH-hybrid method is grounded in the fundamental theorem of DFT, which states that the external potential, and hence the Hamiltonian, is uniquely determined by the material structure ({{{{\mathcal{R}}}}}) [6] [11]. The goal is to model the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian ({H}_{{{{\rm{DFT}}}}}^{{{{\rm{hyb}}}}}({{{{\mathcal{R}}}}})) using a neural network.

A critical consideration for the feasibility of this approach is the nearsightedness principle. In localized basis sets, the Hamiltonian matrix element (H{ij}) between atoms (i) and (j) becomes non-zero only within a certain cutoff radius (RC) [6]. DeepH-hybrid leverages this locality by formulating the problem as learning the Hamiltonian matrix blocks for local atomic environments. Specifically, the matrix block (H{ij}) connecting atoms (i) and (j) is learned as a function of the structural information within a neighborhood defined by a nearsightedness length (RN), encompassing all atoms (k) where (r{ik}, r{jk} < R_N) [6]. This transforms a global quantum mechanical problem into a series of tractable local learning tasks.

Neural Network Architecture and Equivariance

DeepH-hybrid employs E(3)-equivariant neural networks [6]. Equivariance is a fundamental property ensuring that the model's predictions transform consistently with the symmetries of Euclidean space—translations, rotations, and reflections. When the input atomic structure is rotated or translated, the output Hamiltonian transforms predictably and correctly without the need to learn these symmetries from data. This inductive bias drastically improves the data efficiency, reliability, and physical consistency of the model [6].

The model is trained on a dataset comprising material structures and their corresponding Hamiltonian matrices, typically computed using a reference hybrid functional like HSE06 [22]. The training process involves minimizing the difference between the Hamiltonian predicted by the neural network and the one obtained from costly ab initio self-consistent field calculations.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of DeepH-hybrid

| System Type | Key Result | Computational Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Materials | Demonstrates good reliability, transferability, and efficiency | Bypasses SCF iterations; enables large-scale hybrid-DFT calculations | [6] |

| Large-Supercell Moiré Materials | Applied to magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene | Makes study of complex, large-scale systems feasible | [6] [21] |

| Twisted van der Waals Heterostructures | Accurate electronic structure for systems with >10,000 atoms | Reduces computation time for HSE06 functional significantly | [11] |

Application Notes and Protocols

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end DeepH-hybrid protocol for efficient electronic structure calculation.

Protocol 1: Model Training and Validation

This protocol details the creation and validation of a DeepH-hybrid model.

1. Dataset Preparation:

- Software Requirements: Utilize an atomic-orbital based DFT package that supports hybrid functionals, such as ABACUS [22] or HONPAS [11].

- Structure Selection: Curate a diverse set of material structures (e.g., bulk crystals, surfaces, molecules) relevant to the target application. The training set should encompass a wide range of chemical environments and bonding patterns.

- Reference Calculations: Perform self-consistent field (SCF) calculations with a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06) for all structures in the dataset. The primary output is the resulting Hamiltonian matrix for each structure.

- Data Export: Extract and preprocess the Hamiltonian matrices and corresponding atomic structures into the format required by the DeepH-hybrid code [22].

2. Neural Network Training:

- Codebase: Use the DeepH-hybrid package, which builds upon the DeepH-E3 framework [22].

- Input Features: The model takes the local atomic environment within the specified cutoff radius (R_N) as input.

- Training Loop: The model is trained to minimize the loss function, which measures the difference between the predicted and ab initio Hamiltonian matrix blocks. The E(3)-equivariant architecture ensures physical correctness.

- Validation: The trained model's accuracy is validated on a held-out test set of structures not seen during training. Metrics include the error in predicted Hamiltonian matrix elements and derived properties like band energies.

3. Application to Large-Scale Systems:

- Input: Provide the atomic structure of the large-scale system of interest.

- Inference: The trained DeepH-hybrid model processes the structure and predicts the complete Hamiltonian matrix without performing SCF iterations.

- Post-Processing: Diagonalize the predicted Hamiltonian to obtain the electronic wavefunctions and eigenvalues, from which properties like the density of states and band structure are computed.

Protocol 2: Interface with HONPAS for Large-Scale Calculations

This protocol describes a specific implementation combining DeepH with the HONPAS software to handle systems with over ten thousand atoms [11].

1. Prerequisites:

- Software: DeepH code and HONPAS DFT package.

- Basis Set: Typically, a double-zeta polarized (DZP) basis set is used for accurate results [11].

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: The DeepH method, with its pre-trained model, is used to predict the Hamiltonian matrix (H) for the large-scale atomic structure.

- Step 2: An interface passes this precomputed Hamiltonian to HONPAS, bypassing its internal SCF procedure.

- Step 3: HONPAS utilizes the provided Hamiltonian to compute the electronic structure and related properties.

3. Key Outcomes:

- This combined approach demonstrates a massive reduction in computation time for the HSE06 functional.

- It enables the study of complex systems like twisted bilayer graphene and twisted bilayer MoS₂ with hybrid-functional accuracy, revealing, for instance, that the HSE06 functional predicts a larger band gap than PBE in gapped MoS₂ and at the Γ point in graphene systems [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ABACUS DFT Package | Performs reference hybrid-DFT calculations for dataset generation. | Uses atomic orbital basis sets; supports HSE06 functional [22]. |

| HONPAS DFT Package | Specialized software for large-scale hybrid-DFT calculations. | Implements HSE06; efficient for systems >10,000 atoms [11]. |

| DeepH-hybrid Code | Core neural network framework for learning the Hamiltonian. | Built on DeepH-E3; uses equivariant neural networks [6] [22]. |

| HSE06 Functional | Target hybrid functional for accuracy. | Mixes GGA exchange with screened Hartree-Fock exchange [6] [11]. |

| DeepH-hybrid Dataset | Curated data for training and validation. | Contains material structures and precomputed HSE06 Hamiltonians [22]. |

Key Applications and Case Studies

Twisted Moiré Materials

A landmark application of DeepH-hybrid is the study of Moiré-twisted materials, such as magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (MATBG) [6] [21]. These systems form large supercells containing thousands of atoms, making conventional hybrid-DFT calculations prohibitively expensive. DeepH-hybrid enabled the first case study on how the inclusion of exact exchange influences the famous flat bands in MATBG, providing new insights that were previously inaccessible [6] [21].

Broad Material Design

The method is generalizable and can be applied to a wide range of material classes. By providing hybrid-level accuracy at a computational cost comparable to semi-local DFT, it dramatically accelerates high-throughput material screening and the accurate prediction of electronic properties for disordered systems, defects, and interfaces [6] [11].

The workflow below summarizes the logical progression of the DeepH-hybrid method from its theoretical foundation to its scientific impact.

The nearsightedness of electronic matter (NEM) is a fundamental principle in quantum physics that states local electronic properties, such as electron density, depend significantly on the effective external potential only at nearby points [23]. This principle provides the theoretical foundation for efficient electronic structure calculations by demonstrating that local electronic properties remain largely unaffected by distant changes in potential. For a given point in space, perturbations beyond a certain distance R have limited effects on local electronic properties, with these effects rapidly decaying to zero as R increases [23]. This physical insight enables the development of linear-scaling algorithms and forms the cornerstone of modern deep-learning approaches to electronic structure calculation.

In the context of density functional theory (DFT), the nearsightedness principle manifests in the sparse structure of the Hamiltonian matrix when expressed in a localized basis. The matrix element Hᵢⱼ between atoms i and j becomes negligible when their separation exceeds a cutoff radius R_C, typically on the order of angstroms [24]. This locality is preserved even in advanced hybrid density functionals that incorporate non-local exact exchange, despite initial theoretical concerns [6]. The preservation of nearsightedness in hybrid functionals enables the development of accurate deep-learning models that can efficiently handle the computational challenges posed by non-local exchange potentials.

Theoretical Foundation and Physical Principles

Mathematical Formulation of Nearsightedness

The nearsightedness principle can be quantified mathematically by considering how a perturbing potential w(r') of finite support affects the electron density n(r) at a reference point. For a system with chemical potential μ, the density change Δn(r₀) at point r₀ due to any perturbation w(r') beyond a sphere of radius R centered at r₀ has a finite maximum magnitude that decays with increasing R [23]. The decay behavior depends on the electronic structure of the system:

- For insulators and gapped systems, the decay is exponential: Δn(r₀) ∼ e^(-qR) where q is proportional to the band gap [23]

- For metals and gapless systems, the decay follows a power law: Δn(r₀) ∼ 1/R^α where α depends on dimensionality [23]

This mathematical formulation enables the definition of a nearsightedness range R(r₀, Δn), which represents the minimum distance beyond which any perturbation produces density changes smaller than Δn at point r₀ [23].

Nearsightedness in Hybrid Density Functionals

Hybrid density functionals incorporate a fraction of exact exchange from Hartree-Fock theory, leading to a non-local potential operator V_EX(r,r'). The practical application of nearsightedness to hybrid functionals relies on representing this non-local operator in a localized basis set of atomic-like orbitals [6]. In this representation, the exact exchange matrix elements can be expressed as:

Vᴱˣᵢⱼ = -ΣₖₗΣₙ cₙₖcₙₗ*(ik|lj) [6]

where (ik|lj) represents four-center electron repulsion integrals. Although mathematically complex, these matrix elements remain numerically local, satisfying the nearsightedness principle when the Kohn-Sham wavefunctions are localized [6]. This preservation of locality enables the extension of deep-learning Hamiltonian approaches from conventional DFT to the more accurate but computationally demanding hybrid functionals.

Table 1: Nearsightedness in Different Electronic Systems

| System Type | Decay Behavior | Governing Parameters | Nearsightedness Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulators | Exponential | Band gap (G), Effective mass (m*) | R ∼ 1/q, q ∝ G |

| Metals | Power law (Friedel oscillations) | Fermi wavevector (k_F) | R ∼ 1/k_F |

| Disordered Systems | Exponential | Localization length | R ∼ localization length |

| Hybrid Functional DFT | Exponential | Basis set localization, Screening length | R ∼ localization radius of Wannier functions |

DeepH Methodology: Implementing Nearsightedness in Neural Networks

Neural Network Architecture and Equivariance

The DeepH method implements the nearsightedness principle through a message-passing neural network (MPNN) architecture that naturally respects the physical constraints of electronic systems [24]. The network represents crystalline materials as graphs where atoms correspond to vertices and interatomic connections within a cutoff radius R_C form edges. This graph structure explicitly encodes the nearsightedness principle by limiting interactions to physically relevant atomic neighbors.

A critical innovation in DeepH is handling the gauge covariance of the DFT Hamiltonian matrix. The Hamiltonian transforms covariantly under rotations of the local basis functions, requiring special architectural considerations [24]. DeepH addresses this challenge by transforming the Hamiltonian into local coordinate systems where the matrix blocks become rotation-invariant, then applying inverse transformations to obtain the globally covariant Hamiltonian [24]. This approach ensures that the neural network learns fundamental physical relationships rather than spurious coordinate-dependent correlations.

The DeepH-hybrid Extension for Hybrid Functionals

DeepH-hybrid extends the original DeepH method to handle hybrid density functionals, which incorporate non-local exact exchange [6]. This extension demonstrates that the generalized Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian of hybrid functionals can be represented by neural networks while preserving the nearsightedness principle. The key insight is that although hybrid functionals introduce a non-local potential, the overall Hamiltonian remains short-ranged when represented on a localized basis [6].

The DeepH-hybrid method leverages E(3)-equivariant neural networks to model the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian as a function of material structure [6]. This approach bypasses the expensive self-consistent field iterations traditionally required for hybrid functional calculations, reducing the computational cost while maintaining high accuracy. The method has been successfully applied to complex materials systems, including twisted van der Waals heterostructures with supercells containing over 10,000 atoms [25].

Diagram 1: DeepH Workflow. The DeepH method transforms the atomic structure into a graph representation, processes it within a nearsightedness region using equivariant neural networks, and produces the full DFT Hamiltonian for property calculations.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol 1: Training DeepH-hybrid Models

Objective: Train a DeepH-hybrid model to predict hybrid-functional Hamiltonians from atomic structures.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Training structures: Diverse set of material configurations (100-10,000 structures)

- Reference data: DFT Hamiltonian matrices computed with hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06)

- Software: DeepH package [26], DFT codes (e.g., FHI-aims, HONPAS) [25] [13]

Procedure:

- Data Generation:

- Perform structural sampling using active learning or molecular dynamics trajectories [27]

- Run hybrid functional DFT calculations with appropriate numerical settings

- Extract Hamiltonian matrices in a localized basis representation

Network Training:

Model Evaluation:

- Compare predicted vs. DFT-calculated band structures (target: <50 meV error) [24]

- Test on larger supercells to verify scaling and nearsightedness

- Validate derived properties (density of states, band gaps)

Table 2: Performance Metrics of DeepH-hybrid Methods

| Method | System Type | Hamiltonian Error (meV) | Band Gap Error (eV) | Speedup Factor | System Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepH (PBE) | Twisted bilayer graphene | 1-10 [24] | 0.05-0.1 [24] | 10³-10⁴ [24] | >10,000 atoms [24] |

| DeepH-hybrid | Moiré materials | 1-20 [6] | 0.1-0.2 [6] | 10²-10³ [6] | >10,000 atoms [25] |

| DeepH-r | Various materials | Improved accuracy [28] | N/A | Similar to DeepH [28] | N/A |

Protocol 2: Applying DeepH-hybrid to Moiré Materials

Objective: Study the effect of exact exchange on flat bands in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene.

Materials:

- Structure generation: Create moiré superlattices with twist angles 1.0°-1.2°

- Software: DeepH-hybrid, post-processing tools for electronic properties

- Computational resources: GPU clusters for inference, standard workstations for analysis

Procedure:

- Supercell Construction:

- Generate twisted bilayer graphene structures with supercells >10,000 atoms [25]

- Relax atomic positions using classical potentials or DFT with semilocal functionals

Hamiltonian Prediction:

- Load pre-trained DeepH-hybrid model [6]

- Process structure through neural network to obtain hybrid-functional Hamiltonian

- For comparison, perform same calculation with semilocal DeepH model

Electronic Structure Analysis:

- Compute band structures focusing on flat bands near charge neutrality

- Calculate density of states with hybrid vs. semilocal functionals

- Analyze how exact exchange modifies band gaps and band widths

Validation:

- Compare with available experimental data (ARPES, transport)

- Verify consistency with smaller-scale direct hybrid functional calculations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Computational Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepH Package [26] | Software | Deep-learning DFT Hamiltonian | Core implementation of DeepH and DeepH-hybrid methods |

| HONPAS [25] | Software | Density functional theory code | Hybrid functional calculations, interface with DeepH |

| FHI-aims [13] | Software | All-electron DFT code | Hybrid functional database generation, all-electron calculations |

| Message-Passing Neural Network [24] | Algorithm | Equivariant neural network architecture | Learning Hamiltonian from atomic structures |

| Localized Atomic Orbitals [24] | Basis Set | Representation of electronic states | Sparse Hamiltonian representation enabling nearsightedness |

| Hybrid Functionals (HSE06) [13] | Methodology | Beyond-GGA density functional | Accurate electronic structure including band gaps |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Twisted Van der Waals Materials

The application of DeepH-hybrid to twisted van der Waals materials represents a landmark achievement in computational materials science. These systems, particularly magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene, feature moiré superlattices with unit cells containing thousands of atoms, making direct hybrid functional calculations prohibitively expensive [6] [25]. DeepH-hybrid enables the first systematic study of how exact exchange influences the famous flat bands in these systems [6].

The calculations reveal that the inclusion of exact exchange modifies band widths and gaps, potentially affecting the correlated electron physics in these materials [6]. This application demonstrates the power of combining nearsightedness with deep learning to address previously intractable problems in quantum materials research.

Large-Scale Materials Databases

The nearsightedness principle facilitates the creation of large-scale materials databases with hybrid-functional accuracy. Traditional high-throughput DFT screening has relied predominantly on semilocal functionals due to computational constraints [13]. DeepH-hybrid enables the efficient generation of hybrid-functional quality data for thousands of materials, as demonstrated by databases containing 7,024 inorganic materials with HSE06 calculations [13].

These databases reveal significant differences in formation energies and band gaps compared to semilocal functionals, with a mean absolute deviation of 0.15 eV/atom for formation energies and 0.77 eV for band gaps [13]. Such datasets provide crucial training data for machine learning models and enable more reliable predictions of material properties for applications in catalysis, electronics, and energy technologies.

Diagram 2: Database Generation Workflow. Leveraging nearsightedness enables efficient generation of hybrid-functional quality materials databases, accelerating materials discovery.

Future Perspectives and Methodological Evolution

The nearsightedness principle continues to inspire new methodological developments in deep-learning electronic structure. The recent DeepH-r method extends the approach by learning the real-space Kohn-Sham potential rather than the Hamiltonian matrix [28]. This approach offers several advantages, including simplified equivariance relationships and enhanced nearsightedness properties [28]. By learning a basis-independent quantity, DeepH-r potentially offers greater transferability across different computational settings.

Future research directions include developing "large materials models" pre-trained on extensive databases that can be fine-tuned for specific applications [28]. Such models would leverage the nearsightedness principle to achieve unprecedented accuracy and efficiency, potentially revolutionizing computational materials design. As these methods mature, they will enable reliable first-principles calculations for increasingly complex materials systems, from heterogeneous catalysts to biological molecules, all while maintaining the fundamental physical principle of nearsightedness that makes such calculations computationally feasible.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as the workhorse method for simulating matter at the atomic scale, but its predictive power has been fundamentally limited by approximations to the unknown exchange-correlation (XC) functional. For decades, the development of XC functionals has followed "Jacob's Ladder," a paradigm of adding increasingly complex, hand-crafted mathematical features to improve accuracy at the expense of computational efficiency [29]. Despite these efforts, no conventional functional has achieved consistent chemical accuracy—defined as errors below 1 kcal/mol—across broad chemical spaces [30]. This accuracy barrier has prevented computational simulations from reliably predicting experimental outcomes, instead relegating them mostly to interpreting laboratory results.

The emergence of deep learning is catalyzing a paradigm shift from this hand-crafted approach to an end-to-end data-driven methodology. This transformation mirrors the revolution that deep learning brought to computer vision and natural language processing [29]. In the specific context of hybrid density functional calculations, which mix semi-local DFT with non-local exact exchange, two groundbreaking approaches exemplify this shift: the Skala functional, which learns the XC functional directly from high-accuracy data, and the DeepH-hybrid method, which learns the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian itself [6] [21]. This application note examines these complementary approaches, their experimental validation, and practical implementation protocols, framing them within the broader thesis that deep learning can overcome long-standing trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost in electronic structure calculations.

Technical Breakdown of Data-Driven Approaches

The Skala Functional: Architecture and Training Methodology

Skala represents a fundamental reimagining of the XC functional as a deep neural network that learns directly from electron density features, bypassing the traditional constraints of Jacob's Ladder [31] [29]. Its architecture incorporates several key innovations designed to balance expressiveness with physical rigor and computational efficiency.

Input Representation and Feature Learning: Skala utilizes standard meta-GGA ingredients as inputs, which are evaluated on the numerical integration grid. However, unlike traditional functionals that apply hand-designed equations to these features, Skala employs a neural network to learn complex, non-local representations directly from data [32]. This allows it to capture electron correlation effects that have proven difficult to model with conventional mathematical forms.

Physical Constraints and Regularization: The architecture incorporates known exact constraints from DFT, including the Lieb–Oxford bound, size-consistency, and coordinate-scaling relations [32]. By embedding these physical priors into the model, Skala ensures physically plausible predictions while maintaining the flexibility to learn from data.

Two-Phase Training Protocol: The development of Skala followed a sophisticated training regimen:

- Pre-training Phase: The model was initially pre-trained on B3LYP densities with XC labels extracted from high-level wavefunction energies [32].

- SCF-in-the-Loop Fine-Tuning: The pre-trained model underwent further refinement using self-consistent field (SCF) calculations with Skala's own densities, without backpropagation through the SCF cycle [32]. This crucial step ensures stability in production use.

Computational Implementation: Skala maintains computational scaling comparable to meta-GGA functionals and is engineered for GPU execution through integration with the GauXC library [32]. This represents a critical advantage over hybrid functionals, which typically exhibit 5-10× higher computational cost due to the non-local exact exchange term [6].

DeepH-Hybrid: Learning the Hybrid-Functional Hamiltonian

While Skala focuses on learning the XC functional, the DeepH-hybrid approach addresses the hybrid-DFT challenge from a different angle: learning the entire Hamiltonian as a function of material structure using deep equivariant neural networks [6] [21]. This method is particularly valuable for studying complex materials where the non-local exact exchange potential plays a crucial role in electronic properties.

Equivariant Architecture: DeepH-hybrid employs E(3)-equivariant neural networks that respect the Euclidean symmetries of 3D space (translations, rotations, and reflections) [6]. This architectural choice ensures that predictions transform correctly under these operations, significantly improving data efficiency and physical consistency.

Nearsightedness Principle: A fundamental theoretical insight enabling DeepH-hybrid is the preservation of the "nearsightedness" principle even for hybrid functionals with their non-local exchange potentials [6]. The method leverages this by representing the Hamiltonian matrix element between atoms i and j as dependent only on the local atomic environment within a cutoff radius, making the learning problem tractable.

Application to Complex Materials: This approach has demonstrated particular value for studying moiré-twisted materials like magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene, where it enabled the first case study on how inclusion of exact exchange affects flat bands—a calculation that would be prohibitively expensive with conventional hybrid-DFT methods [6] [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Driven Approaches for Hybrid-DFT Calculations

| Feature | Skala Functional | DeepH-Hybrid Method |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Target | Exchange-Correlation Functional | Hybrid-Functional Hamiltonian |

| Architecture | Neural XC functional with meta-GGA inputs | E(3)-equivariant neural networks |

| Key Innovation | Learned non-local representations from data | Structure-to-Hamiltonian mapping |

| Computational Cost | Semi-local DFT cost [33] | Empirical tight-binding cost [6] |

| Primary Application | Molecular chemistry [32] | Materials science [6] |

| Physical Constraints | Embedded via architecture [32] | Embedded via equivariance [6] |

Experimental Validation and Performance Benchmarks

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The validation of Skala followed rigorous benchmarking protocols against established standard datasets. The functional was evaluated on W4-17 (a comprehensive set of atomization energies) and GMTKN55 (a diverse collection of chemical reaction energies), with both sets carefully excluded from training to prevent data leakage [32].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of Skala on Standard Datasets

| Benchmark Dataset | Skala Performance (MAE) | Best Conventional Functional (MAE) | Chemical Accuracy Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| W4-17 (full set) | 1.06 kcal/mol [32] | ~2× higher error [34] | 1 kcal/mol |

| W4-17 (single-reference subset) | 0.85 kcal/mol [32] | Not reported | 1 kcal/mol |

| GMTKN55 (WTMAD-2) | 3.89 kcal/mol [32] | Competitive with best hybrids [32] | Varies by reaction type |

These results demonstrate that Skala achieves chemical accuracy for atomization energies, a fundamental thermochemical property, while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to semi-local DFT [33]. Independent assessments note that Skala's prediction error is approximately half that of ωB97M-V, considered one of the most accurate conventional functionals available [34].

Application to Twisted Bilayer Graphene

The DeepH-hybrid method enabled a previously infeasible study of how exact exchange inclusion affects the flat bands in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene [6] [21]. Conventional hybrid-DFT calculations for these large moiré supercells would be computationally prohibitive, but DeepH-hybrid made such investigations tractable by learning the hybrid-functional Hamiltonian from smaller systems and transferring it to larger structures. This application exemplifies the method's potential to overcome scale limitations in materials research.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Skala for Molecular Energy Calculations

Purpose: To calculate atomization energies and reaction barriers for main-group molecules with hybrid-DFT accuracy at semi-DFT cost.

Materials and Software:

- Computational Environment: Azure AI Foundry instance or local HPC cluster with GPU acceleration [33]

- Software Dependencies: PySCF/ASE with microsoft-skala PyPI package or GauXC integration for production calculations [32]

- Dispersion Correction: D3(BJ) empirical dispersion correction (applied as post-processing) [32]

Procedure:

- Molecular Structure Preparation

- Generate initial molecular geometry using chemical sketching tools or database retrieval

- Perform preliminary geometry optimization with semi-local functional (r²SCAN recommended)

- Verify structure convergence (force thresholds < 0.01 eV/Å)

Skala Single-Point Energy Calculation

- Initialize Skala functional via PySCF interface:

- For batch processing of multiple molecules, utilize GauXC GPU acceleration [32]

Result Analysis

- Extract total energy from SCF calculation

- Apply D3(BJ) dispersion correction if not included automatically

- Calculate atomization energies via isodesmic reactions or direct atomic separation

Troubleshooting:

- SCF convergence issues: Employ damping or DIIS mixing techniques

- For radicals or open-shell systems: Use unrestricted Skala implementation

- Memory limitations: Reduce grid size or employ batch processing

Protocol 2: DeepH-Hybrid for Materials Hamiltonian Learning

Purpose: To predict hybrid-DFT electronic structures for complex materials using neural network representation of the Hamiltonian.

Materials and Software:

- DeepH-Hybrid Codebase: Available from original publication repositories [6]

- Training Data: Small-scale hybrid-DFT calculations for target material class

- Equivariant Neural Network Framework: Custom implementation following published architecture [6]

Procedure:

- Training Data Generation

- Perform self-consistent hybrid-DFT calculations for varied atomic configurations of target material

- Extract Hamiltonian matrix elements in localized basis set representation

- Apply data augmentation using symmetry operations

Network Training

- Configure E(3)-equivariant network architecture with appropriate cutoff radius

- Train model to predict Hamiltonian matrix elements from atomic structure

- Validate on held-out configurations to ensure transferability

Large-Scale Prediction

- Apply trained model to large-scale structure (e.g., moiré superlattices)

- Solve eigenvalue problem using predicted Hamiltonian

- Analyze electronic properties (band structures, density of states)

Validation:

- Compare band gaps and band structures with available hybrid-DFT benchmarks

- Verify consistency across different supercell sizes

- Check fulfillment of physical constraints and symmetries

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Data-Driven XC Development

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|