The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Quantum Mechanics for Molecular Structure in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive guide explores the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, the fundamental quantum mechanical principle enabling modern computational chemistry.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Quantum Mechanics for Molecular Structure in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, the fundamental quantum mechanical principle enabling modern computational chemistry. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we detail the theory's core concept of separating nuclear and electronic motion, its mathematical formulation, and its critical role in molecular modeling. We then examine practical implementations in computational drug design, common limitations and breakdown scenarios (e.g., conical intersections), optimization strategies for accurate simulations, and validation through comparisons with higher-level theories and experimental data. The article concludes with the approximation's enduring impact on biomolecular simulation and future directions for addressing its limitations in next-generation therapeutics development.

What is the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation? Quantum Foundations for Molecular Modeling

This technical whitepaper explicates the core physical principle enabling the separation of fast electron dynamics from slow nuclear motion. This separation is the foundational axiom of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) Approximation, a cornerstone concept in quantum chemistry, molecular physics, and computational drug design. The broader thesis posits that the BO approximation is not merely a computational convenience but a physically robust framework whose validity and breakdown conditions are critical for accurate predictions in molecular spectroscopy, reaction dynamics, and biomolecular interaction modeling—areas of direct relevance to rational drug development. This document provides a rigorous technical guide to the principle, its experimental validation, and modern computational methodologies.

Theoretical Foundation: The BO Approximation

The BO approximation arises from the significant disparity in mass (and hence velocity and kinetic energy) between electrons (mass mₑ) and atomic nuclei (mass M, typically >1800mₑ). The full, time-independent Schrödinger equation for a molecule is: ĤΨtot(R, r) = Etot Ψtot(R, r) where R and r denote nuclear and electronic coordinates, respectively.

The Hamiltonian is separated as: Ĥ = Tn(R) + Te(r) + Vne(R, r) + Vee(r) + V_nn(R)

The core principle is that electrons adjust instantaneously to any nuclear configuration. This allows the wavefunction to be factored: Ψtot(R, r) ≈ χ(R) · ψR(r). Here, ψR(r) is the electronic wavefunction solved for a *clamped* nuclear configuration, giving a potential energy surface (PES) Eel(R) upon which nuclei move: [Tn(R) + Eel(R)] χ(R) = E_tot χ(R).

Quantitative Justification: Mass & Energy Scales

The validity of the separation rests on quantifiable differences in energy and time scales.

Table 1: Comparative Mass, Energy, and Time Scales for Electrons and Nuclei

| Property | Electrons | Protons/Nuclei (e.g., Carbon-12) | Ratio (Nuclei/Electron) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rest Mass (kg) | 9.109 × 10⁻³¹ | 1.673 × 10⁻²⁷ (proton) | ~1836 |

| Typical Kinetic Energy Scale | 1-10 eV (Valence) | ~0.025 eV (Room T vib.) | ~40-400 |

| Characteristic Motion Timescale (fs) | ~0.1 (orbital period) | ~10-100 (vibration period) | ~100-1000 |

| De Broglie Wavelength (in molecule) | Comparable to bond lengths | Much smaller, classical path | — |

Table 2: Key Non-Dimensional Parameters Validating the BO Approximation

| Parameter | Formula | Physical Meaning | Typical Order | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Ratio | κ = (mₑ / M)^1/4 | Expansion parameter in perturbation theory. | ~0.1 | Small parameter justifies adiabatic separation. |

| Energy Gap Ratio | ΔE_el / |

Electronic vs. nuclear vibrational energy spacing. | >10 | Ensures negligible non-adiabatic coupling for ground state. |

| Non-Adiabatic Coupling | <ψi|∇Rψ_j> | Coupling between electronic states i and j. | Small for large ΔE_ij | Large when PESs approach or cross (BO breakdown). |

Experimental Protocols for Validation & Probing

Ultrafast Spectroscopy to Probe Time-Scale Separation

Protocol: Femtosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

- Pump Pulse: An ultrashort (~10-50 fs) laser pulse (pump) promotes the molecule to an excited electronic state.

- Nuclear Motion: Nuclei begin to move on the new Potential Energy Surface (PES).

- Probe Pulse: A delayed, broad-band white-light pulse (probe) measures the time-dependent absorption spectrum.

- Analysis: The spectral evolution reveals distinct timescales: instantaneous electronic response (sub-10 fs) followed by slower vibrational wavepacket dynamics (10s-100s fs) and finally thermalization/relaxation (ps-ns).

High-Resolution Vibrational-Rotational Spectroscopy

Protocol: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) or Cavity Ring-Down Spectroscopy

- Sample Preparation: Isolate molecule in gas phase or inert matrix to minimize intermolecular interactions.

- Scanning: Measure absorption/emission across infrared region with high resolution (<0.01 cm⁻¹).

- Spectral Fitting: Analyze fine structure of vibrational bands. The presence of clean, well-defined rotational fine structure for each vibrational level confirms that the vibrational Hamiltonian (nuclear motion on a single E_el(R)) accurately describes the system, validating the BO separation for that state.

Photoelectron Spectroscopy to Map the PES

Protocol: Angle-Resolved Photoelectron Spectroscopy (ARPES) for Molecules

- Photoionization: A monochromatic VUV/X-ray photon ionizes the molecule, ejecting an electron: M → M⁺ + e⁻.

- Kinetic Energy Analysis: The kinetic energy of the ejected electron is measured with high precision: KEe = hν - (Ebind + E_vib⁺).

- Mapping: By varying photon energy or detecting electron angle, one can reconstruct the vibrational energy levels (E_vib⁺) of the molecular ion. The pattern of these levels directly maps the PES of the ion, a result of the BO separation for M⁺.

Computational Methodologies

Ab Initio Electronic Structure Calculation Protocol

Objective: Solve for ψR(r) and Eel(R) at a single nuclear geometry.

- Input: Define nuclear charges and coordinates (R). Choose a basis set (e.g., cc-pVTZ).

- Mean-Field Solution: Perform a Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation to obtain an initial guess for the electron density.

- Electron Correlation: Apply a post-HF method (e.g., Coupled-Cluster Singles and Doubles - CCSD) or Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a selected functional (e.g., ωB97X-D) to account for electron-electron correlation.

- Output: Obtain total electronic energy (E_el), electron density, and wavefunction derivatives. Repeat over a grid of R to construct the PES.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Protocols

A. Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD):

- At each MD time step (≈0.5-1 fs), perform a full electronic structure calculation (as in 5.1) to compute forces on nuclei from E_el(R).

- Integrate Newton's equations for nuclei using these forces.

- Advantage: Fully consistent with BO approximation. Disadvantage: Computationally expensive.

B. Ehrenfest Dynamics (Beyond BO):

- Propagate nuclei on a time-dependent potential that is an average over multiple electronic states, weighted by their instantaneous population.

- Used when non-adiabatic couplings are strong (e.g., conical intersections in photochemical reactions).

- Application: Models breakdown of the BO approximation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational & Experimental Reagents

| Item/Category | Example/Product | Function & Relevance to BO Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Software | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, NWChem | Solves the electronic Schrödinger equation at fixed R, providing E_el(R) and forces. Core to implementing the BO approximation. |

| Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Suite | CP2K, VASP (for solids), TERACHEM (GPU) | Performs BOMD simulations, explicitly separating electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom. |

| Non-Adiabatic Dynamics Code | SHARC, MCTDH, Tully's fewest-switches surface hopping | Models dynamics when BO approximation fails, treating electron-nuclei coupling explicitly. |

| Ultrafast Laser System | Ti:Sapphire amplifier (e.g., Coherent Libra) | Generates <50 fs pulses to experimentally resolve the temporal separation of electronic and nuclear motion. |

| Quantum Chemistry Basis Set | Dunning's cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q), Pople's 6-31G* | Mathematical functions representing atomic orbitals. Critical for accurate calculation of E_el(R). |

| Density Functional (DFT) | ωB97X-D, B3LYP, PBE0 | Approximate functionals for electron exchange-correlation. Balance of accuracy/cost for large systems (e.g., drug molecules). |

| Pseudopotential/PP | Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH), Norm-Conserving PPs | Replaces core electrons with an effective potential, reducing computational cost while maintaining valence electron accuracy (relies on BO). |

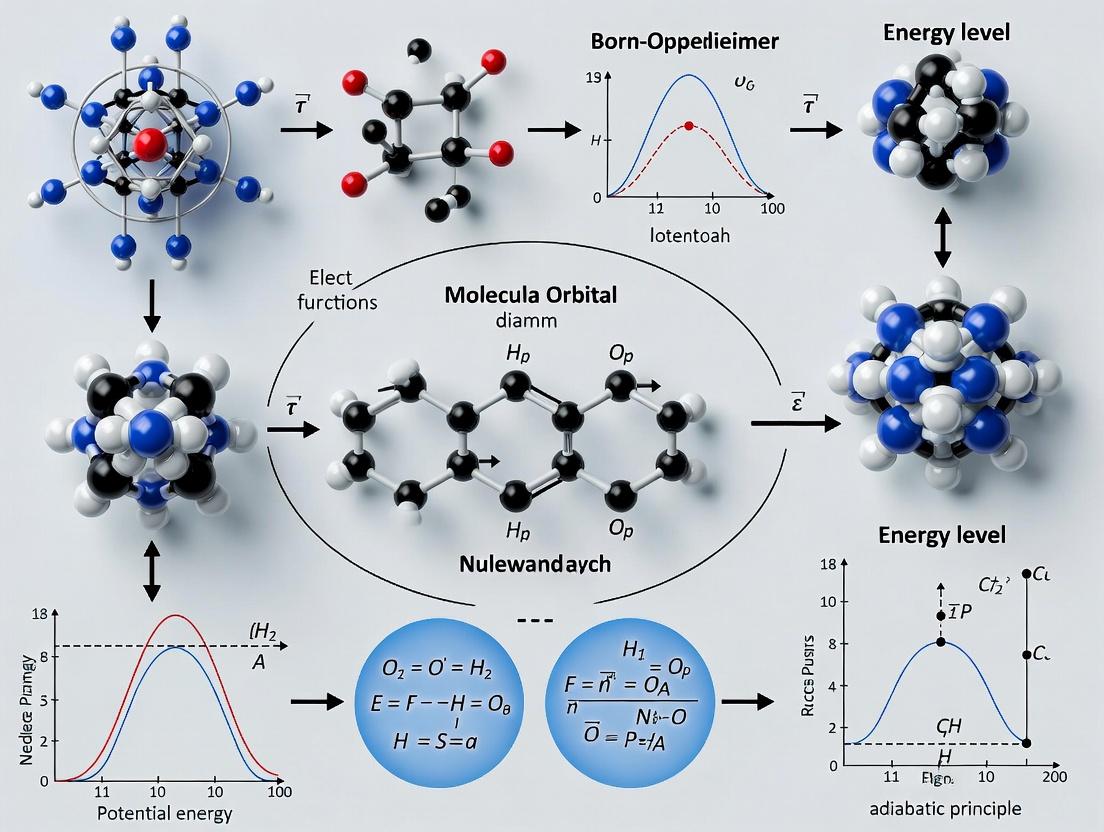

Visualization of Concepts & Workflows

This whitepaper explores the evolution of quantum chemistry from the foundational Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation to contemporary computational methodologies. The core thesis posits that the BO approximation is not merely a historical simplification but the essential theoretical scaffold enabling the entire edifice of ab initio electronic structure calculations and molecular dynamics simulations. Its separation of electronic and nuclear motion remains the critical first step in solving the molecular Schrödinger equation, directly impacting fields from catalyst design to computer-aided drug discovery.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Core Theory

The BO approximation addresses the complexity of the molecular Schrödinger equation: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) ] where (\mathbf{r}) and (\mathbf{R}) denote electronic and nuclear coordinates, respectively. The Hamiltonian is: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} = -\sum{i} \frac{\hbar^2}{2me} \nablai^2 -\sum{A} \frac{\hbar^2}{2MA} \nablaA^2 - \sum{i,A} \frac{ZA e^2}{|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{R}A|} + \sum{i>j} \frac{e^2}{|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}j|} + \sum{A>B} \frac{ZA ZB e^2}{|\mathbf{R}A - \mathbf{R}_B|} ]

The BO approximation exploits the significant mass disparity ((me \ll MA)), leading to a two-step solution:

- Electronic Structure Problem: Treat nuclei as fixed at position (\mathbf{R}), solve for electronic wavefunction (\psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r})) and energy (E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R})): [ \hat{H}{\text{el}} \psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) = \left( \hat{T}e + \hat{V}{eN} + \hat{V}{ee} + \hat{V}{NN} \right) \psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) = E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \psi_{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) ]

- Nuclear Motion Problem: Use (E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R})) as the potential energy surface (PES) for nuclear motion: [ \left[ \hat{T}N + E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \right] \chi(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \chi(\mathbf{R}) ]

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of the BO Approximation

| Parameter | Without BO Separation | With BO Approximation | Computational Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupled Variables | ~3(Nelec + Nnuc) | 3Nelec and then 3Nnuc | Dimensionality reduced from ~103 to tractable separate problems |

| Wavefunction Form | (\Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R})) | (\Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) \approx \psi_{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) \cdot \chi(\mathbf{R})) | Enables variational methods for electrons |

| Timescale Decoupling | ~1 fs (electronic) & ~10-100 fs (nuclear) | Electronic solved for static nuclei | Allows geometry optimization, MD on single PES |

Evolution of Computational Methods Post-BO

The BO approximation enabled the development of hierarchical computational methods, each with varying fidelity and cost.

Table 2: Hierarchy of Quantum Chemical Methods Enabled by the BO Approximation

| Method Class | Theoretical Foundation | Typical System Size | Accuracy (Energy) | Scaling (O(N^k)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Mean-field, single determinant | 10-100 atoms | ±50-100 kcal/mol | N4 |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Kohn-Sham equations, functional approximation | 100-1000 atoms | ±5-20 kcal/mol | N3 |

| Post-Hartree-Fock (MP2, CCSD(T)) | Electron correlation, perturbative/CI methods | 10-50 atoms | ±1-5 kcal/mol (CCSD(T)) | N5-N7 |

| Semi-empirical | Parametrized integrals | 1000-10,000 atoms | Variable, system-dependent | N2-N3 |

| Force Fields (Classical MD) | Newtonian mechanics, empirical potentials | 10,000-1,000,000 atoms | Not applicable for electronic properties | N2 |

Title: Evolution of Computational Methods from BO Approximation

Experimental Protocols in Modern Computational Chemistry

Protocol 1: Ab Initio Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Calculation (using DFT)

- System Preparation: Obtain 3D structures of protein and ligand from PDB or docking. Add hydrogen atoms and assign protonation states at physiological pH using software like

PDB2PQRorH++. - Geometry Optimization: Isolate the ligand and a defined binding site (e.g., residues within 5-10 Å of ligand). Perform full geometry optimization using a DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP, ωB97X-D) and a basis set (e.g., 6-31G*) with an implicit solvation model (e.g., PCM, SMD) to relax the structure to the nearest local minimum on the BO PES.

- Single-Point Energy Calculation: Using the optimized geometry, perform a higher-accuracy single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and a dispersion-corrected functional. Calculate the energy for the complex (Ecomplex), the protein (Eprotein), and the ligand (Eligand).

- Binding Energy Calculation: Compute ΔEbind = Ecomplex - (Eprotein + Eligand). Apply thermodynamic corrections (from frequency calculations) to approximate ΔGbind.

Protocol 2: Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) Simulation

- Initial Configuration: Build or obtain a solvated system (e.g., protein in a water box with ions) using tools like

CHARMM-GUIortleap. - Electronic Structure Setup: Choose a fast, ab initio electronic structure method applicable to dynamics, typically Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a plane-wave basis set (e.g., in

CP2K,VASP) or a tight-binding method (DFTB). - Dynamics Propagation: At each molecular dynamics step (Δt ≈ 0.5-1.0 fs): a. With nuclei fixed at position R(t), solve the electronic Schrödinger equation to obtain the ground-state energy Eel(R) and wavefunction. b. Calculate the Hellmann-Feynman forces on nuclei: F = -∇REel(R). c. Propagate nuclei to time t+Δt using Newton's equations (MA d²RA/dt² = FA) via integrators like Verlet or Velocity Verlet.

- Analysis: Analyze the generated trajectory for structural stability, dynamics, and spectroscopic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources for BO-Based Research

| Item (Software/Resource) | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4 | Electronic Structure | Solves the BO electronic problem via HF, DFT, and post-HF methods. Provides energies, geometries, and molecular properties. |

| CP2K, VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO | Ab Initio MD | Performs Born-Oppenheimer or Car-Parrinello MD using DFT, calculating forces on-the-fly from the electronic structure. |

| AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS | Classical MD | Propagates nuclear dynamics on a single, pre-defined BO PES described by a classical force field. |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling | Adds algorithms (metadynamics, umbrella sampling) to classical or ab initio MD to efficiently explore the BO PES. |

| basis set exchange | Basis Set Library | Repository of Gaussian-type orbital basis sets essential for defining the wavefunction expansion in BO calculations. |

| Molpro, Q-Chem | High-Accuracy Quantum Chemistry | Implements advanced correlated methods (e.g., CCSD(T), MRCI) for benchmarking on the BO PES. |

Title: Workflow for Drug Discovery Calculations Using BO Framework

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is a cornerstone of molecular quantum mechanics, enabling the separation of electronic and nuclear motion. Its validity hinges critically on the adiabatic theorem, which states that a physical system remains in its instantaneous eigenstate if a given perturbation is acting on it slowly enough. In molecular systems, the "slow" perturbation is the nuclear kinetic energy operator. This whitepaper provides a rigorous derivation of the adiabatic theorem's role in justifying the neglect of specific nuclear kinetic energy terms within the standard BO framework, a fundamental concept for researchers in quantum chemistry and molecular modeling for drug development.

Foundational Theory and Mathematical Framework

The total molecular Hamiltonian for a system with nuclei (N) and electrons (e) is: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} = \hat{T}N(\mathbf{R}) + \hat{T}e(\mathbf{r}) + \hat{V}{eN}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) + \hat{V}{NN}(\mathbf{R}) + \hat{V}{ee}(\mathbf{r}) ] where (\mathbf{R}) and (\mathbf{r}) denote nuclear and electronic coordinates, respectively.

The BO approximation posits a wavefunction of the form (\Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \chi(\mathbf{R}) \psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r})), where (\psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r})) is the electronic eigenfunction for clamped nuclei: [ \left[ \hat{T}e + \hat{V}{eN} + \hat{V}{ee} + \hat{V}{NN} \right] \psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) = E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \psi{\mathbf{R}}(\mathbf{r}) ] The nuclear wavefunction (\chi(\mathbf{R})) is then a solution to: [ \left[ \hat{T}N + E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \right] \chi(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \chi(\mathbf{R}) ] This simple separation neglects the action of the nuclear kinetic energy operator (\hat{T}N) on the parametric (\mathbf{R})-dependence of the electronic wavefunction. A full treatment reveals the coupled nature of the equations.

Mathematical Derivation of the Non-Adiabatic Couplings

Acting with the full Hamiltonian on the product ansatz: [ \hat{H}{\text{total}} [\chi \psi{\mathbf{R}}] = \psi{\mathbf{R}} \hat{T}N \chi + \chi \hat{T}N \psi{\mathbf{R}} + \chi \hat{H}{\text{el}} \psi{\mathbf{R}} ] Since (\hat{H}{\text{el}} \psi{\mathbf{R}} = E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \psi{\mathbf{R}}), we focus on the term (\hat{T}N (\chi \psi{\mathbf{R}})). The nuclear kinetic energy operator is (\hat{T}N = -\sum{k} \frac{\hbar^2}{2Mk} \nabla{\mathbf{R}_k}^2).

Applying the Laplacian: [ \nabla^2{\mathbf{R}k} (\chi \psi{\mathbf{R}}) = \chi \nabla^2{\mathbf{R}k} \psi{\mathbf{R}} + 2 (\nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \chi) \cdot (\nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \psi{\mathbf{R}}) + \psi{\mathbf{R}} \nabla^2{\mathbf{R}k} \chi ] Substituting back, the full Schrödinger equation becomes: [ \left[ \hat{T}N + E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \right] \chi \psi{\mathbf{R}} - \sum{k} \frac{\hbar^2}{2Mk} \left[ 2 (\nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \chi) \cdot (\nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \psi{\mathbf{R}}) + \chi (\nabla^2{\mathbf{R}k} \psi{\mathbf{R}}) \right] = E{\text{total}} \chi \psi_{\mathbf{R}} ]

Multiplying from the left by (\psi{\mathbf{R}}^*) and integrating over electronic coordinates yields the equation for the nuclear wavefunction: [ \left[ \hat{T}N + E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) + \hat{T}N^{\text{(BO)}} \right] \chi(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \chi(\mathbf{R}) ] where the *Born-Oppenheimer correction terms* are: [ \hat{T}N^{\text{(BO)}} = \langle \psi{\mathbf{R}} | \hat{T}N | \psi{\mathbf{R}} \ranglee + \sumk \frac{\hbar^2}{Mk} \langle \psi{\mathbf{R}} | \nabla{\mathbf{R}k} | \psi{\mathbf{R}} \ranglee \cdot \nabla{\mathbf{R}_k} ] The first term is the adiabatic diagonal correction (small but non-zero). The second, first-derivative term is the non-adiabatic coupling vector. Its magnitude dictates the validity of the BO approximation.

The Adiabatic Theorem and Its Quantitative Criterion

The adiabatic theorem provides the condition for neglecting the non-adiabatic coupling. Consider two electronic eigenstates (m) and (n). The coupling between them is proportional to the matrix element: [ \mathbf{F}{mn}^{(k)}(\mathbf{R}) = \langle \psim(\mathbf{R}) | \nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \psin(\mathbf{R}) \rangle = \frac{\langle \psim | \nabla{\mathbf{R}k} \hat{H}{\text{el}} | \psin \rangle}{En(\mathbf{R}) - Em(\mathbf{R})}, \quad m \neq n ] The BO approximation is valid when the nuclear motion is too slow to induce transitions between electronic states. The quantitative condition is: [ \frac{\hbar |\mathbf{v}k \cdot \mathbf{F}{mn}^{(k)}|}{|En - Em|} \ll 1 ] where (\mathbf{v}_k) is the nuclear velocity. This states that the energy gap between electronic states must be large compared to the coupling strength induced by nuclear motion.

Table 1: Characteristic Energy Scales and Coupling Strengths in Molecular Systems

| System / Molecule | Typical Electronic Gap ΔE (eV) | Representative Non-Adiabatic Coupling (ℏv·F) (eV) | BO Validity Ratio (ℏv·F / ΔE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ (Ground State) | ~10 | ~0.001 | ~10⁻⁴ (Excellent) |

| Organic Molecule (S₀/S₁) | 3.0 - 5.0 | ~0.01 - 0.1 (near conical intersection) | ~0.003 - 0.03 (Valid away from CI) |

| Transition Metal Complex | 1.0 - 2.0 | ~0.05 - 0.2 | ~0.025 - 0.2 (Conditional) |

| Biological Chromophore (e.g., GFP) | 2.5 | Can approach ~0.5 near funnels | Can approach ~0.2 (Requires NA-MD) |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Non-Adiabaticity

Protocol 1: Ultrafast Spectroscopy for Non-Adiabatic Coupling Measurement

- Sample Preparation: Purify target molecule (e.g., a photopharmacological agent). Prepare solution in appropriate solvent, degas to prevent quenching.

- Pump-Probe Setup: Use a femtosecond laser system (Ti:Sapphire amplifier, 800 nm, 100 fs pulses). Generate pump pulse at absorption maximum (via OPA/DFG). Probe pulse is a broadband white-light continuum.

- Data Acquisition: Excite sample with pump pulse. Measure transient absorption spectra at delayed time intervals (0-10 ps). Track decay of excited-state absorption and rise of ground-state bleach/stimulated emission.

- Analysis: Fit time traces at key wavelengths. Multi-exponential decay reveals timescales. Deviations from single-exponential behavior, especially sub-100 fs components, indicate strong non-adiabatic coupling, often due to conical intersections. Map observed rates against energy gaps computed via TD-DFT or CASSCF.

Protocol 2: Cryogenic Matrix Isolation Spectroscopy for Adiabatic Potential Validation

- Matrix Deposition: Co-deposit vaporized target molecule with large excess of inert gas (Ar or Ne) onto a cryogenically cooled (10 K) CsI window in a high-vacuum chamber.

- Slow Energy Relaxation: Allow the trapped molecules to relax adiabatically to their vibrational ground state on the electronic potential energy surface.

- Spectral Measurement: Record high-resolution FTIR and electronic absorption spectra. Narrow, vibrationally resolved bands confirm the system is in the adiabatic ground state.

- Perturbation: Gradually warm the matrix or introduce a slow, coordinated perturbation (e.g., polarized light). Monitor spectral changes. Minimal band broadening or shifting indicates the system remains in its instantaneous eigenstate, a direct observation of adiabatic following.

Diagram Title: The Adiabatic Criterion Decision Workflow in the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Reagents for Adiabaticity Research

| Item Name | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| High-Level Electronic Structure Software (e.g., Molpro, OpenMolcas, MOLPRO) | Performs multireference calculations (CASSCF, MRCI) to accurately map adiabatic PESs and compute non-adiabatic coupling vectors, especially near conical intersections. |

| Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics (NAMD) Suite (e.g., SHARC, Newton-X) | Propagates nuclear motion on multiple coupled PESs using surface hopping or other mixed quantum-classical algorithms, essential when the BO approximation fails. |

| Femtosecond Laser System with OPA/DFG | Generates tunable ultrafast pulses to initiate and probe non-adiabatic dynamics (e.g., internal conversion, intersystem crossing) on the timescale of nuclear motion (fs-ps). |

| Cryostat (Liquid He) with Vacuum Chamber | Enables matrix isolation spectroscopy, creating a near-perfect adiabatic environment by minimizing thermal perturbations and allowing observation of pristine eigenstates. |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (¹³C, ¹⁵N, D) | Simplifies complex vibrational spectra, allowing precise tracking of nuclear motion on adiabatic surfaces and deconvolution of kinetic isotope effects in reaction rates. |

| Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) Software (e.g., CP2K, FHI-aims) | Computes on-the-fly electronic structure forces for nuclear trajectories, capable of capturing adiabatic dynamics and, with extensions, non-adiabatic effects. |

The adiabatic theorem provides the rigorous mathematical underpinning for separating electronic and nuclear dynamics. The neglect of the nuclear kinetic energy term's off-diagonal action is justified only when electronic energy gaps are large relative to the non-adiabatic coupling. In drug development, this justifies the widespread use of molecular mechanics force fields (which assume a single, adiabatic PES) for simulating protein-ligand binding. However, processes like photodynamic therapy, redox reactions, or interactions with transition metals often involve closely spaced electronic states, requiring non-adiabatic methodologies for accurate modeling. Understanding these limits is crucial for predicting reaction pathways, designing photopharmaceuticals, and interpreting spectroscopic data in complex biological environments.

Within the foundational framework of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, the concept of the Potential Energy Surface (PES) emerges as the central result. The BO approximation posits a separation between fast-moving electrons and slow-moving nuclei due to their significant mass disparity. Mathematically, the total molecular wavefunction is factorized: Ψtotal(r, R) ≈ ψel(r; R) χ_nuc(R). Here, r and R denote electronic and nuclear coordinates, respectively.

The key outcome is that for each fixed nuclear geometry R, one solves the electronic Schrödinger equation: Ĥel ψel(r; R) = Eel(R) ψel(r; R). The resulting eigenvalue, Eel(R), when combined with the nuclear repulsion energy Vnn(R), defines the potential energy surface: V(R) = Eel(R) + Vnn(R). This V(R) governs nuclear motion, serving as the potential term in the nuclear Schrödinger equation. Thus, the multi-dimensional PES is the effective landscape upon which nuclei move, enabling the prediction of molecular structure, stability, reactivity, and spectroscopic properties.

Computational Methodologies for PES Mapping

Mapping the PES requires calculating V(R) at many points. The choice of method balances accuracy and computational cost.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Electronic Structure Methods for PES Computation

| Method | Key Theory | Computational Scaling | Typical Accuracy (Energy) | Best For PES Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Kohn-Sham equations with approximate exchange-correlation functional. | O(N³) | ~5-10 kcal/mol | Equilibrium geometries, transition states. |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Mean-field approximation, includes exchange but not correlation. | O(N⁴) | ~50-100 kcal/mol (error large) | Not recommended for quantitative PES; baseline. |

| Møller-Plesset Perturbation (MP2) | Post-HF method; 2nd-order perturbation theory for correlation. | O(N⁵) | ~5-10 kcal/mol (if HF good) | Non-covalent interactions, single-reference regions. |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | "Gold standard"; includes single, double, perturbative triple excitations. | O(N⁷) | ~1-2 kcal/mol | Highly accurate benchmarks, small systems. |

| Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) | Multi-configurational SCF within an active orbital space. | Exponential with active space size | Variable; qualitative shapes | Bond breaking, excited states, near-degeneracies. |

Experimental Protocol: Ab Initio PES Mapping for a Triatomic Molecule (e.g., H₂O)

- System Definition: Define internal coordinates (e.g., two O-H bond lengths, R1, R2, and the H-O-H bond angle, θ).

- Grid Generation: Create a 3D grid over relevant ranges (e.g., R1, R2: 0.7-1.5 Å; θ: 80°-120°). Step size determines resolution (e.g., 0.05 Å, 5°).

- Single-Point Calculation: For each geometry point Ri on the grid: a. Input Ri to the electronic structure code (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem). b. Specify method and basis set (e.g., CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ). c. Execute calculation to obtain total electronic energy Eel(Ri) and Vnn(Ri). d. Compute V(Ri) = Eel(Ri) + Vnn(R_i).

- Surface Fitting: Fit computed points to an analytic function (e.g., polynomial, neural network potential) for continuous representation.

- Critical Point Location: Use algorithms (e.g., quasi-Newton) to find stationary points where ∇V(R)=0:

- Minima: Stable isomers (all vibrational frequencies real).

- First-Order Saddle Points: Transition states (one imaginary frequency).

- Validation: Compare harmonic frequencies at minima with experimental spectroscopic data. Check reaction path connectivity via intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations.

Workflow for Computational PES Mapping

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for PES Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Software (Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, PySCF) | Core engines to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation at specified geometries and theory levels. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the necessary computational power for expensive ab initio calculations over many grid points. |

| Basis Set Libraries (cc-pVXZ, def2-TZVP, 6-31G*) | Sets of mathematical functions (atomic orbitals) used to expand molecular orbitals; directly impact accuracy and cost. |

| Automation & Scripting Tools (Python, Bash) | For automating grid generation, job submission, data extraction, and surface fitting. |

| PES Visualization/Analysis Software (Matplotlib, VMD, Jmol) | To generate 2D/3D contour and surface plots from multi-dimensional energy data. |

| Global Optimization Packages (GLOW, OPTIM) | Specialized algorithms for efficiently locating minima and saddle points on complex, high-dimensional PESs. |

| Machine Learning Potential Libraries (PyTorch, TensorFlow, AmpTorch) | Frameworks to train neural network potentials on ab initio data, enabling rapid PES evaluation for molecular dynamics. |

Advanced Concepts: Beyond the Basic BO PES

The BO approximation breaks down when electronic states become close in energy (near-degeneracies), leading to conical intersections and non-adiabatic coupling. Here, the single-surface picture fails, and multiple PESs must be considered simultaneously.

Table 3: Scenarios Requiring Beyond-Born-Oppenheimer Treatments

| Scenario | Physical Consequence | Required Computational Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Photochemical Reactions | Ultrafast radiationless decay via conical intersections. | Multi-reference methods (CASSCF/CASPT2, MRCI) to map coupled PESs. |

| Jahn-Teller Distortions | Spontaneous symmetry breaking in degenerate electronic states. | Calculation of adiabatic PESs for split components. |

| Spin-Orbit Coupling | Mixing of different spin multiplicities (e.g., singlet-triplet). | Relativistic quantum chemistry methods (e.g., DFT with SOC). |

| Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics | Electronic transitions during nuclear motion (e.g., electron transfer). | Surface hopping or Ehrenfest dynamics on multiple PESs. |

PES Coupling at Conical Intersections

The Potential Energy Surface, as directly furnished by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, remains the central unifying concept for understanding and predicting molecular behavior. Its accurate computation enables rational design in catalysis and drug development—by identifying transition states for kinetic modeling or protein-ligand binding landscapes for free energy calculations. Ongoing advances in machine-learned interatomic potentials and explicit beyond-BO dynamics ensure the PES paradigm will continue to underpin molecular simulation, connecting quantum mechanics to observable chemical phenomena.

This document constitutes a core chapter of a comprehensive thesis on the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation. The broader research investigates the foundational theory, historical development, and modern computational applications of this cornerstone concept in quantum chemistry. Herein, we dissect the key physical and chemical assumptions underpinning the BO approximation and provide a rigorous analysis of why, and under what precise conditions, these assumptions remain valid for the vast majority of molecular systems in their electronic ground state. This validity is the bedrock upon which modern computational drug discovery and materials science are built.

Foundational Assumptions of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The BO approximation separates the total molecular wavefunction into a product of electronic and nuclear components: Ψtotal(r, R) ≈ ψel(r; R) χ_nuc(R). This separation rests on three critical, interconnected assumptions.

The Mass Disparity Assumption

The core physical rationale is the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei (me << mnuc). This leads to a disparate timescale of motion: electrons, being light, adjust almost instantaneously to any change in nuclear configuration. Nuclei, therefore, experience an average potential field generated by the rapidly-moving electrons.

Quantitative Justification: The validity can be assessed by comparing characteristic energy scales.

Table 1: Characteristic Energy Scales in Molecules

| Energy Term | Typical Magnitude (cm⁻¹) | Physical Origin | Implication for BO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy (E_el) | 10⁴ - 10⁶ | Electronic transitions | Large separation from nuclear energies. |

| Vibrational Energy (E_vib) | 10² - 10³ | Nuclear vibration | Small compared to E_el. |

| Rotational Energy (E_rot) | 1 - 10² | Molecular rotation | Negligible on electronic scale. |

| Non-Adiabatic Coupling | < 10² (usually) | Derivative coupling ⟨ψel∣∇R ψ_el⟩ | Measures BO breakdown; small for ground states. |

The Adiabaticity Assumption

The system remains on a single adiabatic electronic potential energy surface (PES). This assumes no coupling between electronic states induced by nuclear motion. The electronic wavefunction is parametrically dependent on R, meaning it changes smoothly with nuclear positions without undergoing transitions.

The Neglect of Non-Adiabatic Couplings

The approximation explicitly neglects the derivative coupling terms, ⟨ψel∣∇R ψel⟩ and ⟨ψel∣∇²R ψel⟩, which represent the dynamical interaction between electronic and nuclear motion. Their magnitude is inversely proportional to the energy gap between electronic states.

Experimental Validation Methodologies

Verifying the BO approximation involves probing the separation of electronic and nuclear dynamics and quantifying non-adiabatic effects.

High-Resolution Vibrational Spectroscopy

Protocol: Use Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) or Raman spectroscopy to measure vibrational frequencies of isotopologues (e.g., H₂O vs. D₂O). Rationale: Under the BO approximation, the electronic potential is isotope-independent. Observed isotopic shifts in vibrational levels are purely due to changes in reduced nuclear mass. Agreement between calculated (using BO-derived potentials) and observed isotope shifts validates the approximation for the ground-state PES. Workflow: 1) Synthesize/purity isotopologues. 2) Acquire high-resolution IR/Raman spectra under controlled pressure/temperature. 3) Fit spectra to extract precise vibrational constants. 4) Compare experimental shifts with ab initio predictions from BO-based electronic structure calculations.

Femtosecond Pump-Probe Spectroscopy

Protocol: Employ ultrafast laser pulses to track wavepacket dynamics on potential energy surfaces. Rationale: A femtosecond "pump" pulse excites a molecule. A delayed "probe" pulse interrogates the system. For molecules where BO holds strongly in the ground state, wavepacket motion on an excited PES is coherent and can be modeled using BO surfaces. Observing predicted recurrence times validates the model. Breakdown manifests as rapid dephasing or population transfer at conical intersections. Workflow: 1) Generate sub-50-fs laser pulses. 2) Split into pump and probe beams with variable time delay. 3) Focus beams onto molecular jet sample. 4) Detect ion or fluorescence signal as a function of delay. 5) Reconstruct nuclear dynamics and compare to quantum dynamics simulations with/without BO.

Precision Measurement of Dissociation Energies

Protocol: Measure bond dissociation energies (D₀) via velocity-map imaging of photofragment spectroscopy or threshold ionization. Rationale: The BO approximation provides adiabatic dissociation curves. Highly accurate experimental D₀ values can be compared to values computed by solving the nuclear Schrödinger equation on a high-level ab initio BO potential. Agreement within computational error bars supports the fidelity of the BO PES.

Validation Pathways for the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Experimental BO Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function in Validation | Critical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents/Compounds (e.g., D₂O, CDCl₃) | Provide isotopologues for vibrational spectroscopy to test mass-disparity assumption. | Isotopic purity > 99.8% D. |

| Molecular Beam Source | Produces cold, isolated gas-phase molecules to eliminate solvent effects and simplify spectra. | Rotational temperature < 10 K. |

| Femtosecond Ti:Sapphire Laser System | Generates ultrafast pulses to initiate and probe nuclear dynamics on femtosecond timescales. | Pulse width < 100 fs, tunable wavelength. |

| Velocity Map Imaging (VMI) Detector | Measures speed and angular distribution of photofragments for precise dissociation energy mapping. | Position-sensitive delay-line anode. |

| High-Precision Wavelength Meter | Calibrates laser wavelengths for accurate determination of transition energies and gaps. | Absolute accuracy < 0.0001 nm. |

| Cryogenic Spectroscopy Cell | Cools samples to reduce thermal broadening of spectral lines for higher resolution. | Temperature stability ±0.1 K at 10 K. |

Conditions for Breakdown and Ground-State Resilience

The BO approximation fails when its core assumptions are violated. Notably, most ground-state molecules are resilient.

Table 3: Conditions for BO Breakdown vs. Ground-State Resilience

| Condition for Breakdown | Typical Molecular Scenario | Why Most Ground States Are Robust |

|---|---|---|

| Small Electronic Energy Gaps | Conical intersections, near-degeneracies in transition metals or excited states. | Ground states typically have a large HOMO-LUMO gap (> several eV) to the first excited state. |

| Light, Fast-Moving Nuclei | Hydrogen tunneling, reactions involving proton-coupled electron transfer. | While protons are light, in stable ground-state geometries, the potential wells are deep and coupling terms remain small. |

| High Kinetic Energy of Nuclei | High-temperature plasmas, extreme photodissociation. | Ground-state molecules at equilibrium or thermal energies have nuclear velocities where the adiabatic following holds. |

| Strong Spin-Orbit Coupling | Heavy elements (e.g., lanthanides, actinides). | For organic molecules and first/second-row elements prevalent in drug design, spin-orbit effects are minimal in the ground state. |

BO Assumptions, Violations, and Ground-State Shielding

Within the framework of our thesis, this analysis substantiates that the Born-Oppenheimer approximation's enduring success for ground-state molecules is not accidental but a direct consequence of well-understood physical principles. The significant mass disparity, combined with the typically large energy gap between the ground and first excited electronic state in stable molecules, ensures the smallness of non-adiabatic coupling terms. This allows for the reliable construction of adiabatic potential energy surfaces, which form the computational backbone for quantum chemistry, molecular dynamics simulations, and structure-based drug design. The approximation's limits are clearly marked by conditions of degeneracy, involving very light nuclei, or high energy—conditions often avoided in the stable ground-state systems central to pharmaceutical research.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation is a cornerstone of quantum chemistry and molecular physics, enabling the separation of electronic and nuclear motion. This approximation rests on the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei, allowing the electronic Schrödinger equation to be solved for fixed nuclear positions. The resulting electronic energy acts as a potential energy surface (PES) upon which nuclei move. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to visualizing the core concepts of electronic and nuclear dynamics within this fundamental theory, which is critical for research in molecular spectroscopy, reaction dynamics, and computational drug design.

Core Theoretical Principles and Quantitative Data

The BO approximation introduces a separation of variables based on the ratio of electron mass (m_e) to nuclear mass (M). The key quantitative relationships are summarized below.

Table 1: Fundamental Mass and Energy Scales in the BO Approximation

| Parameter | Typical Value/Scale | Implication for Motion Separation |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Ratio (m_e / M_proton) | ~ 1 / 1836 | Nuclei are ~10³ times slower than electrons. |

| Electronic Motion Timescale | Attoseconds (10⁻¹⁸ s) | Electrons instantaneously adjust to nuclear position. |

| Nuclear Vibration Timescale | Femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) | Nuclei move on a pre-computed electronic PES. |

| Typical Electronic Energy Gap | 1 - 10 eV (HOMO-LUMO) | Defines the adiabatic condition. |

| Typical Vibrational Quantum (ħω) | 0.05 - 0.5 eV | Energy scales are often separable. |

| BO Approximation Breakdown | ~0.1 - 1.0 eV (e.g., conical intersections) | Non-adiabatic coupling becomes significant. |

The total molecular wavefunction is written as: Ψ_total(r, R) = χ(R) · φ_R(r) where r and R denote electronic and nuclear coordinates, *φ_R(r) is the electronic wavefunction for fixed R, and *χ(R) is the nuclear wavefunction on the PES E(R).

Experimental & Computational Protocols for Visualization

Protocol 3.1: Ab Initio Calculation of a Diatomic Potential Energy Curve

- Objective: Compute the electronic energy E(R) for a diatomic molecule (e.g., H₂) across a range of internuclear distances R.

- Methodology:

- Geometry Definition: Choose a series of internuclear distances, Ri, from 0.3 Å to 3.0 Å.

- Electronic Structure Calculation: At each fixed Ri, perform a Hartree-Fock or DFT (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) calculation to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation. This yields the electronic energy *Eelec*(Ri).

- Add Repulsion: Add the nuclear-nuclear repulsion term ZAZB/Ri to obtain the total potential energy E(Ri).

- Plotting: Plot E(R) vs. R to visualize the PES (bonding curve, equilibrium geometry Re, dissociation energy De).

- Key Visualization: The resulting curve is the central schematic for nuclear motion.

Protocol 3.2: Time-Dependent Nuclear Wavepacket Propagation

- Objective: Visualize nuclear motion (vibration) on the computed PES.

- Methodology:

- PES Grid: Use the E(R) from Protocol 3.1 as the potential V(x) in the nuclear Schrödinger equation.

- Initial Wavepacket: Define a Gaussian wavepacket, χ(x, t=0), centered at a non-equilibrium position (e.g., stretched bond).

- Propagation: Employ a time-propagation algorithm (e.g., Split-Operator, Chebyshev) to solve iħ ∂χ/∂t = [ - (ħ²/2μ) ∇² + V(x) ] χ.

- Analysis: Plot the probability density |χ(x, t)|² at sequential time steps to show wavepacket oscillation (vibration) and, potentially, dephasing.

Protocol 3.3: Non-Adiabatic Dynamics at a Conical Intersection

- Objective: Probe the breakdown of the BO approximation where electronic and nuclear motion couple.

- Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a model system (e.g., the 2D linear vibronic coupling model for pyrazine).

- PES Calculation: Compute two (or more) coupled electronic states, E1(Q) and E2(Q), as a function of nuclear coordinates Q. Identify the seam of degeneracy (conical intersection).

- Initial Conditions: Place a nuclear wavepacket on the upper electronic state E1.

- Coupled Propagation: Propagate the coupled electron-nuclear system using the Multi-Configuration Time-Dependent Hartree (MCTDH) method or surface hopping (e.g., Tully's fewest-switches).

- Observable: Track the population transfer from E1 to E_2 as the wavepacket passes through the intersection region.

Schematic Visualizations

Diagram 1: Born-Oppenheimer separation flow (67 chars)

Note: A full PES plot requires external graphics. The DOT script above provides a structured legend. The implied schematic shows the red PES curve E(R) with a green electronic cloud at fixed R₁ and a yellow nuclear vibrational probability distribution centered at Rₑ. Diagram 2: Diatomic PES with distributions (54 chars)

Diagram 3: Conical intersection-mediated dynamics (58 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in BO/Visualization Research |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Software | Perform ab initio or DFT calculations to solve the electronic problem and generate PESs. |

| MCTDH Package | Dynamics Software | Propagate coupled electron-nuclear wavepackets for exact or multi-configurational dynamics. |

| Terahertz/Femtosecond Laser Pulses | Experimental Probe | Initiate and track nuclear motions (vibrations, rotations) on the PES in real time. |

| Transient Absorption Spectroscopy | Experimental Method | Monitor electronic state populations and coherences as nuclei move, detecting non-adiabatic events. |

| Cryogenic Ion Traps | Experimental Apparatus | Isolate and cool molecular ions to simplify vibrational spectra and compare with BO calculations. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Resource | Provides the processing power for high-level electronic structure calculations and quantum dynamics. |

| VMD, Jmol, Matplotlib | Visualization Software | Render molecular orbitals, PESs, and nuclear probability distributions from computational output. |

| Model Hamiltonian Parameters (e.g., Vibronic Coupling Constants) | Theoretical Construct | Parameterize coupled PESs for non-adiabatic dynamics simulations in model systems. |

Implementing BO: From Theory to Computational Drug Design Applications

The efficacy of modern ab initio quantum chemical methods is predicated on the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation. This cornerstone concept separates the motions of nuclei and electrons due to their significant mass disparity, allowing the molecular Hamiltonian to be simplified. The electronic Schrödinger equation is solved for a series of fixed nuclear configurations, generating a potential energy surface (PES) upon which nuclei move. All methods discussed herein—Hartree-Fock (HF), Density Functional Theory (DFT), and post-Hartree-Fock (post-HF)—are electronic structure theories that operate within this BO framework, seeking approximate solutions to the electronic problem.

The Central Role of the Basis Set

A basis set is a set of mathematical functions, typically centered on atomic nuclei, used to expand the molecular orbitals (MOs) or the electron density. The choice of basis set is a critical determinant of the accuracy and computational cost of any ab initio calculation. The expansion is expressed as:

ψi(1) = Σμ c{μi} φμ(1)

where ψi is a molecular orbital, φμ are the basis functions (atomic orbitals), and c_{μi} are the expansion coefficients determined by the specific electronic structure method.

Basis Set Types and Their Evolution

Slater-Type Orbitals (STOs) and Gaussian-Type Orbitals (GTOs)

STOs resemble the exact hydrogenic atomic orbitals but are computationally expensive for integral evaluation. In practice, GTOs are used, where each function is of the form exp(-αr²). Their product is another Gaussian, simplifying integrals. Multiple GTOs are contracted to approximate STO behavior.

Basis Set Families and Key Attributes

Modern basis sets are characterized by several attributes, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Common Basis Set Families

| Basis Set Family | Key Characteristics | Typical Number of Functions per Atom (Light Element) | Primary Use Case | Relative Computational Cost (vs. STO-3G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G*) | Split-valence, polarization functions (d on heavy atoms). | 9-15 functions | Routine HF, DFT geometry optimizations. | 5-10x |

| Correlation-consistent (cc-pVXZ) | Systematic convergence to CBS limit; includes diffuse functions in aug- versions. | X=D: ~14, X=T: ~30, X=Q: ~55 | High-accuracy post-HF (e.g., CCSD(T)). | 10x (D) to 100x (Q) |

| Karlsruhe (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP) | Balanced for DFT, systematically constructed. | SVP: ~15-20, TZVP: ~30-40 | General-purpose DFT, especially for transition metals. | 7-15x |

| Plane Waves (Periodic) | Defined by a kinetic energy cutoff (E_cut). | N/A (System-dependent) | Periodic systems, plane-wave DFT. | Depends on E_cut |

| Minimal (STO-3G) | 3 GTOs per STO; minimal size. | 5 functions | Very large systems, qualitative mapping. | 1x (Baseline) |

Note: Function counts are for a first-row atom (e.g., Carbon). CBS = Complete Basis Set limit.

Method-Specific Basis Set Requirements

Basis for Hartree-Fock Theory

HF seeks the best single Slater determinant. Basis set requirements:

- Minimum: Double-zeta (DZ) quality to describe orbital relaxation.

- Quality: Polarization functions (e.g., d on C, p on H) are essential for describing bond bending and breaking.

- Diffuse Functions: Required for anions, excited states, or properties like dipole moments (e.g., aug-cc-pVDZ).

Basis for Density Functional Theory (DFT)

DFT uses an electron density functional. Requirements are similar to HF but often more forgiving due to empirical exchange-correlation functionals.

- Standard: Triple-zeta valence with polarization (TZVP) is a robust standard for accuracy and cost.

- Dispersion: Specialized basis sets (e.g., def2-TZVP with appropriate auxiliary basis for RI-J) are optimized for modern DFT functionals, including dispersion corrections.

Basis for Post-Hartree-Fock Methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T))

These methods account for electron correlation. They have more stringent demands:

- Correlation Consistency: The cc-pVXZ (X=D,T,Q,5,...) family is explicitly designed to converge smoothly to the CBS limit for correlated calculations. Larger X values (more functions) recover more correlation energy.

- Diffuse Functions: Absolutely critical for weak interactions (hydrogen bonds, van der Waals) and electron affinities (aug-cc-pVXZ).

- Core Correlation: For highest accuracy, core electrons can be correlated using cc-pCVXZ basis sets.

Experimental Protocol: A Basis Set Convergence Study for Drug-Receptor Binding Energy

This protocol outlines a standard computational experiment to determine an appropriate basis set for calculating intermolecular interaction energies, a key task in drug development.

Objective: Calculate the binding energy (ΔE_bind) of a ligand (L) with a protein active site model (P) at various levels of theory and basis sets to assess convergence.

System Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structures of ligand (L) and receptor model (P) from crystallography (PDB) or docking.

- Perform geometry optimization of L, P, and the complex (L---P) using a reliable DFT functional (e.g., ωB97X-D) with a medium basis set (e.g., def2-SVP). Apply implicit solvation (e.g., PCM for water).

- Freeze optimized geometries for the subsequent single-point energy calculations.

Single-Point Energy Calculations:

- Methodology Levels:

- Level 1: DFT (e.g., ωB97X-D, B3LYP-D3(BJ))

- Level 2: MP2

- Level 3: "Gold Standard" CCSD(T) (for small models only)

- Basis Set Sequence: Perform calculations on L, P, and L---P using a systematically improving series:

def2-SVP→def2-TZVP→def2-QZVPcc-pVDZ→cc-pVTZ→cc-pVQZ(for correlated methods)- Include

aug-cc-pVTZfor Level 2 and 3 to assess non-covalent interaction accuracy.

- Counterpoise Correction: Apply Boys-Bernardi counterpoise correction to all calculations to correct for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate ΔE_bind = E(L---P) - [E(L) + E(P)] for each method/basis set pair.

- Plot ΔE_bind vs. basis set size (number of basis functions).

- Identify the point of diminishing returns where the energy converges (changes by < ~1 kcal/mol). This defines the sufficient basis set for that methodology.

- For the target method (e.g., MP2), extrapolate to the CBS limit using a two-point formula (e.g., 1/X^3 for MP2) with the two largest basis sets.

Diagram Title: Basis Set Convergence Study Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Computational Experiments

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ab Initio Calculations

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, Q-Chem, PySCF) | The primary "laboratory" environment. Provides implementations of HF, DFT, post-HF algorithms, integral evaluation, and basis set libraries. |

| Standardized Basis Set Libraries (e.g., Basis Set Exchange, EMSL) | Repositories providing formatted basis set definitions (Gaussian94 format) for all elements, ensuring reproducibility and correct usage. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for all but the smallest calculations. Post-HF methods and large basis sets require significant CPU cores, memory, and fast interconnects. |

| Geometry Visualization & Analysis (e.g., VMD, PyMOL, Jmol, Molden) | Used to prepare input structures (e.g., from PDB), visualize optimized geometries, molecular orbitals, and electron density surfaces. |

| Wavefunction Analysis Tools (e.g., Multiwfn, NBO) | Perform advanced analysis on calculation outputs: population analysis, bond orders, energy decomposition, topology of electron density (QTAIM). |

| Implicit Solvation Model Parameters (e.g., PCM, SMD, COSMO) | Define the dielectric and probe parameters to simulate solvent effects, crucial for biochemical applications where water is the medium. |

| Reference Datasets (e.g., S66, GMTKN55) | Benchmark databases of highly accurate experimental or calculated thermodynamic/kinetic data. Used to validate and benchmark new method/basis set combinations. |

Advanced Considerations and Current Trends

- Implicit vs. Explicit Solvation: For drug-binding, a hybrid QM/MM approach or a QM cluster model embedded in a MM point-charge field is often necessary.

- Density Fitting (RI) and Resolution-of-the-Identity: Uses auxiliary basis sets to approximate four-center electron repulsion integrals, drastically speeding up DFT and MP2 calculations with negligible accuracy loss.

- Linear-Scaling Methods and Fragmentation: For very large systems (e.g., full proteins), methods like FMO (Fragment Molecular Orbital) divide the system, perform calculations on fragments, and correct for interactions, relying on robust basis sets for each fragment.

- Machine Learning (ML) Basis Sets: Emerging research focuses on using ML to generate optimized, system-specific compact basis sets, potentially revolutionizing the cost-accuracy trade-off.

Diagram Title: Logical Relationship from BO Approximation to Properties

The selection and systematic use of an appropriate basis set is not a mere technical step but a fundamental aspect of enabling reliable ab initio predictions. Within the fixed-nuclei framework provided by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the basis set controls the expressiveness of the electronic wavefunction or density. As computational drug discovery pushes towards larger and more complex systems, the intelligent choice of basis set—balancing chemical accuracy against computational feasibility—remains a critical skill for the computational researcher. Convergence studies, as outlined, provide the empirical evidence necessary to make this choice defensible for a given target property.

Within the theoretical framework established by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the potential energy surface (PES) emerges as a central concept. This approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motion due to their significant mass difference, allows for the calculation of molecular properties by treating nuclei as moving on a PES defined by the electronic energy. This whitepaper details the core computational methodologies for exploring this surface: geometry optimization to locate minima and transition states, vibrational frequency analysis to characterize stationary points, and reaction path following to map chemical transformations.

Foundational Theory: The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is the cornerstone for calculating molecular properties. Its premise allows the total molecular wavefunction Ψ(r, R) to be separated into an electronic component ψ*e*(*r*; *R*) and a nuclear component χ(*R*): Ψ(*r*, *R*) ≈ ψe(r; R) χ(R) Here, r and R denote electronic and nuclear coordinates, respectively. The electronic Schrödinger equation is solved for fixed nuclear positions, yielding the electronic energy E_e(R), which becomes the potential energy for nuclear motion. All subsequent calculations of molecular properties operate on this PES.

Geometry Optimization

Geometry optimization algorithms locate stationary points (zero gradient) on the PES.

Core Methodology

The objective is to find a nuclear configuration R where the gradient of the energy, g = ∇E(R), is zero. Most algorithms are iterative:

- Initial Guess: Provide an initial molecular geometry.

- Energy & Gradient Calculation: Compute E(Rk) and gk at the current step k.

- Step Determination: Use the gradient and (approximate) Hessian (second derivative matrix, H) to compute a step direction (ΔR).

- Update & Convergence Check: Update the geometry: Rk+1 = Rk + ΔR. Check if |g| < threshold.

Common algorithms include Steepest Descent, Conjugate Gradient, and quasi-Newton methods like Berny or Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS), which build an approximate H.

Experimental/Computational Protocol

Diagram Title: Geometry Optimization Algorithm Flow

Vibrational Frequency Analysis

Vibrational analysis confirms the nature of a stationary point and provides spectroscopic data.

Core Methodology

The harmonic approximation is used. The mass-weighted Hessian matrix H^(m) is constructed from the Cartesian second derivatives. Diagonalization yields eigenvalues λi and eigenvectors: H^(m)L = LΛ The vibrational frequencies ωi (in cm⁻¹) are: ωi = sqrt(λi) / (2πc) where c is the speed of light. The number of imaginary frequencies (negative λ_i) determines the stationary point character: 0 for a minimum (equilibrium structure), 1 for a first-order saddle point (transition state).

Experimental/Computational Protocol

Reaction Path Following

These methods map the minimum energy path (MEP) connecting reactants and products via a transition state.

Core Methodologies

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC): Follows the steepest descent path in mass-weighted coordinates from the transition state down to the connected minima. The path is traced by solving: dR(s)/ds = -∇E(R(s)) / |∇E(R(s))| where s is the reaction coordinate.

- Nudged Elastic Band (NEB): A series of images (structures) connect reactant and product. Images are connected by springs and optimized while being "nudged" to follow the true path, preventing collapse to the minima.

- String Method: Similar to NEB, but images are reparametrized along the path during optimization to maintain equal spacing.

Diagram Title: Stationary Points and Reaction Path on a PES

Experimental/Computational Protocol for IRC

Table 1: Comparison of DFT Methods for Geometry and Frequency of Water Molecule

| Method (Basis Set) | O-H Bond Length (Å) | H-O-H Angle (°) | Symmetric Stretch (cm⁻¹) | Asymmetric Stretch (cm⁻¹) | Bending (cm⁻¹) | CPU Time (s)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP/6-31G(d) | 0.963 | 104.5 | 1648 | 3832 | 3799 | 12 |

| ωB97X-D/6-311++G(d,p) | 0.961 | 104.2 | 1655 | 3845 | 3812 | 47 |

| M06-2X/aug-cc-pVTZ | 0.959 | 104.0 | 1662 | 3858 | 3820 | 189 |

| Experimental Ref. | 0.958 | 104.5 | ~1648 | ~3832 | ~3799 | N/A |

*Approximate timings for a single-point + gradient on a standard CPU core.

Table 2: Key Properties for SN2 Reaction: Cl⁻ + CH₃Cl → ClCH₃ + Cl⁻

| Stationary Point | Method (Basis) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) | Imaginary Freq (cm⁻¹) | Key Geometry Parameter (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactant Complex | MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ | 0.0 | 0 | Cl---C: 3.12 |

| Transition State | MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ | +15.2 | -464 (C-Cl sym str) | C-Cl: 2.15 (both) |

| Product Complex | MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ | -2.5 | 0 | Cl---C: 3.12 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources

| Item/Category | Function & Purpose | Example Vendors/Packages |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Software | Solves the electronic Schrödinger equation to compute energy, gradient, Hessian. Core engine for all properties. | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem, GAMESS, NWChem, CP2K, PySCF, PSI4 |

| Force Field Software | Performs optimization and dynamics using empirical potentials for large systems (proteins, materials). | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS, OpenMM, LAMMPS |

| Visualization & Analysis | Prepares input structures, visualizes outputs (geometries, vibrations, paths), and analyzes results. | Avogadro, GaussView, VMD, PyMOL, Jmol, Multiwfn |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the necessary computational power for expensive quantum chemical calculations. | Local clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, GCP, Azure), National supercomputing centers |

| Basis Set Libraries | Collections of mathematical functions (basis sets) used to construct molecular orbitals. | Basis Set Exchange (repository), EMSL basis set library |

| Reaction Path Tools | Specialized packages for advanced path searching and following. | ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment), geomeTRIC, GRRM |

Within the thesis on Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation basic concepts and theory, its most direct and powerful application is in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) is the foundational computational method where the electronic structure problem is solved at each MD step to obtain forces on the nuclei, assuming the electrons are in their ground state for the instantaneous nuclear configuration. This approach strictly adheres to the BO approximation, separating electronic and nuclear motions.

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Workflow

The BOMD algorithm is a direct numerical implementation of the BO approximation. The nuclei evolve on a single potential energy surface (PES), which is the electronic ground state energy obtained by solving the time-independent electronic Schrödinger equation.

Governing Equations

The classical equations of motion for the nuclei are:

[ MI \ddot{\mathbf{R}}I = -\nablaI \min{\Psi0} E[{\mathbf{R}I}, \Psi0] = \mathbf{F}I ]

where ( MI ) and ( \mathbf{R}I ) are the mass and position of nucleus ( I ), and the force ( \mathbf{F}I ) is derived from the electronic ground state energy ( E0 ).

Table 1: Core Components of the BOMD Force Calculation

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Computational Task | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy | ( E0({\mathbf{R}I}) = \langle \Psi_0 | \hat{H}_e | \Psi_0 \rangle ) | Solve electronic structure |

| Hellmann-Feynman Force | ( \mathbf{F}I = -\langle \Psi0 | \nablaI \hat{H}e | \Psi_0 \rangle ) | Calculate force from converged wavefunction |

| Orthogonality/Pulay Force | ( -\sumi \epsiloni \langle \frac{\partial \psii}{\partial \mathbf{R}I} | \psi_i \rangle + c.c. ) | Account for basis set dependence (if present) |

Core Iterative BOMD Cycle

The workflow is a sequential, iterative loop.

Diagram Title: The BOMD Iterative Algorithm Cycle (Max 760px)

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: A Standard BOMD Simulation Run

Aim: To simulate the time evolution of a molecular system with forces derived from ab initio electronic structure calculations.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Define initial atomic positions ( {\mathbf{R}I(t=0)} ) from crystallographic data or optimized geometry.

- Assign initial nuclear velocities ( {\mathbf{V}I(t=0)} ) from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature.

- Select the electronic structure method (e.g., DFT functional, basis set, convergence criteria).

Single MD Step Execution:

- Electronic Minimization: For the current ( {\mathbf{R}I} ), perform a self-consistent field (SCF) cycle to solve the electronic Hamiltonian. Iterate until the total energy ( E0 ), density matrix, or wavefunction converges below a predefined threshold (e.g., ( \Delta E < 10^{-6} ) Ha).

- Force Evaluation: Using the converged electronic ground state, compute the forces on all nuclei. This requires calculating the Hellmann-Feynman terms. If using atomic orbital basis sets, include Pulay corrections.

- Nuclear Propagation: Feed the forces into a numerical integrator (e.g., Velocity Verlet): [ \mathbf{V}I(t+\Delta t/2) = \mathbf{V}I(t) + (\mathbf{F}I(t)/MI) \cdot (\Delta t/2) ] [ \mathbf{R}I(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{R}I(t) + \mathbf{V}I(t+\Delta t/2) \cdot \Delta t ] *Recalculate forces at new positions*, then: [ \mathbf{V}I(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{V}I(t+\Delta t/2) + (\mathbf{F}I(t+\Delta t)/M_I) \cdot (\Delta t/2) ]

Sampling and Analysis:

- Record the trajectory (positions, velocities), energies, and forces at a specified frequency.

- Run for a sufficient number of steps (N) to achieve statistically meaningful sampling of the phase space (( \text{Total Time} = N \times \Delta t )).

- Analyze trajectories for properties: radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, vibrational spectra, reaction mechanisms.

Table 2: Typical BOMD Simulation Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Purpose/Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Time Step (Δt) | 0.5 - 1.0 fs | Must be shorter than fastest nuclear vibration (~10 fs for H motion). |

| Electronic Energy Convergence | (10^{-5} - 10^{-8}) Ha | Ensures accurate forces; stricter than single-point calculations. |

| Thermostat Coupling Time | 50 - 200 fs | Controls the rate of temperature stabilization (NVT ensemble). |

| Total Simulation Time | 1 - 100+ ps | Determines the observable phenomena; chemical reactions may require >10 ps. |

| SCF Iterations per MD Step | 10 - 50 | Highly system-dependent; initial steps may require more iterations. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key "Reagents" for a BOMD Simulation

| Item | Function in BOMD |

|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Code | Core engine for solving the quantum electronic problem at each step (e.g., CP2K, Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP, Gaussian). |

| Pseudopotentials/PAWs | Replace core electrons to reduce computational cost while accurately modeling valence electron interactions. |

| Basis Set | Set of functions (e.g., plane waves, Gaussian orbitals) to expand the electronic wavefunction. Choice balances accuracy and speed. |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional (DFT) | Approximates quantum mechanical exchange and correlation effects. Critical for accuracy of forces and system properties. |

| Numerical Integrator | Propagates nuclei classically (e.g., Velocity Verlet). Must be time-reversible and symplectic for energy conservation. |

| Thermostat/Barostat | Algorithm (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Langevin) to control temperature/pressure, simulating specific thermodynamic ensembles. |

| Analysis Software Suite | Tools to process trajectory data (e.g., VMD, MDAnalysis, in-house scripts) to compute physical observables. |

Performance Characteristics and Optimization

The computational cost of BOMD is dominated by the electronic structure calculation at each step. The force evaluation is formally an ( O(N^3) ) operation for exact diagonalization methods, though this can be reduced with linear-scaling techniques for large systems.

Diagram Title: Primary Cost Factors in BOMD Simulations (Max 760px)

Applications and Context in Drug Development

For drug development professionals, BOMD provides unparalleled accuracy for studying mechanisms where electronic structure changes are paramount.

Table 4: Application Comparison in Drug Development

| Application | BOMD Role | Advantage over Classical MD |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Mechanism Elucidation | Models bond breaking/forming in enzyme active sites or drug metabolism. | Describes electronic rearrangements; impossible with fixed-force-field MD. |

| Metal-Containing Protein Dynamics | Accurately treats transition metals with complex electronic states (e.g., zinc fingers, hemoglobin). | Correctly captures ligand-field effects, spin states, and charge transfer. |

| Proton Transfer & Polarization | Models Grotthuss mechanism proton hopping and strong polarization effects. | Electron density responds instantaneously to proton motion. |

| Spectroscopic Property Prediction | Trajectories provide time-dependent data for calculating IR, NMR, UV-Vis spectra. | Includes electronic excitation information and anharmonic effects. |

Protocol: Studying a Ligand-Protein Covalent Binding Event with BOMD

Aim: To simulate the nucleophilic attack of a cysteine residue on an electrophilic warhead of a drug candidate.

Procedure:

- Model Setup: Cut a QM region (~50-100 atoms) encompassing the warhead, reacting cysteine (including thiolate), and key catalytic residues. Embed in a larger MM environment of the solvated protein.

- Enhanced Sampling: Use an umbrella sampling or metadynamics protocol along a pre-defined reaction coordinate (e.g., C–S bond distance).

- BOMD Production: For each window along the coordinate, run BOMD (typically with DFT) for 100-500 fs per window to sample the local dynamics and obtain the free energy profile.

- Analysis: Identify transition states, calculate activation free energy, and analyze electronic density differences to map electron flow during the reaction.

BOMD represents the rigorous application of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, offering a first-principles, parameter-free approach to molecular dynamics. Its workflow, while computationally demanding, is essential for investigating chemical reactions, electronically complex systems, and processes where force fields lack reliability. Within the ongoing thesis on BO theory, BOMD stands as its most computationally intensive and scientifically rewarding validation, directly translating quantum mechanical principles into predictive simulations of nuclear motion.

The accurate prediction of ligand-protein interactions is a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. This process fundamentally relies on the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, which decouples electronic and nuclear motion, allowing for the separate calculation of the electronic energy for a fixed nuclear configuration. This approximation enables the computation of a Potential Energy Surface (PES), upon which all molecular docking and scoring functions are implicitly or explicitly built. The rapid evaluation of these interactions through virtual screening (VS) is only possible because the BO framework permits the pre-calculation or parameterization of energy terms, turning an intractable quantum many-body problem into a computationally feasible scoring exercise.

Theoretical Foundation: The BO Approximation in Molecular Recognition

The BO approximation is the critical first step in simplifying the Schrödinger equation for a molecular system. It states that due to the significant mass difference, electrons can instantaneously adjust to the motion of nuclei. This allows the total wavefunction to be separated: [ \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \psi{\text{electronic}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \cdot \chi{\text{nuclear}}(\mathbf{R}) ] Where r and R represent electronic and nuclear coordinates, respectively. The electronic Schrödinger equation is solved for a clamped nuclear configuration, yielding the electronic energy ( Ee(\mathbf{R}) ), which becomes the potential energy for nuclear motion.

In the context of docking and scoring:

- The "ligand-protein complex" represents a specific nuclear configuration (R).

- The scoring function is an approximation of ( E_e(\mathbf{R}) ) or the associated free energy of binding.

- Docking algorithms navigate the PES (a function of ligand translation, rotation, and conformation) to find minima corresponding to putative binding poses. The BO approximation makes defining this surface conceptually possible.

Core Methodologies for Rapid Interaction Evaluation

Molecular Docking Protocols

Docking predicts the preferred orientation (pose) and affinity (score) of a small molecule within a protein's binding site.

Typical Docking Workflow:

- Preparation: Protein and ligand 3D structures are prepared (adding hydrogens, assigning partial charges, removing water molecules except key ones).

- Binding Site Definition: The spatial coordinates of the binding pocket are identified, often from a co-crystallized ligand or via prediction tools.

- Conformational Sampling: The ligand's degrees of freedom (position, orientation, rotatable bonds) are systematically, randomly, or incrementally varied within the defined site.

- Scoring & Ranking: Each generated pose is evaluated using a scoring function. The top-scoring poses are output as predictions.

Virtual Screening Protocols

VS computationally "screens" large libraries of compounds (10^4 - 10^7 molecules) against a target to identify potential hits.

Typical VS Workflow:

- Library Preparation: Compound libraries are curated, standardized, and energetically minimized. Multi-conformer databases may be pre-generated.

- Molecular Docking: Each compound in the library is docked against the prepared protein target using a defined protocol.

- Post-Processing: Top-ranked compounds are clustered, visually inspected, and often re-scored with more rigorous methods (e.g., MM-GBSA).

- Hit Selection: A subset of compounds (50-500) is selected for in vitro experimental validation.

Scoring Functions: The Engine of Rapid Evaluation

Scoring functions are mathematical models that approximate the binding affinity. Their speed relies on the BO-derived concept of a pre-computable energy landscape.

Table 1: Major Classes of Scoring Functions

| Class | Description | Typical Components | Speed | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field-Based | Sums of classical energy terms. | Van der Waals (Lennard-Jones), Electrostatics (Coulomb), Bonded terms. | Fast | Moderate; depends on solvation treatment. |

| Empirical | Linear regression of experimentally determined binding energies. | Hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, rotatable bond penalty, clash terms. | Very Fast | Good for pose prediction; can be system-dependent. |

| Knowledge-Based | Statistical potentials derived from observed atom-pair frequencies in known structures. | Inverse Boltzmann analysis of protein-ligand complex databases. | Fast | Good for ranking; requires large training sets. |

| Machine Learning | Non-linear models trained on binding data. | Descriptors from structures fed into RF, NN, or SVM algorithms. | Fast (after training) | High for training domain; transferability can be limited. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol A: Retrospective Virtual Screening (Validation)

- Target & Decoys: Select a protein target with known active ligands. Generate a library containing these actives mixed with many presumed inactives ("decoys" from databases like DUD-E or DEKOIS).

- Docking Run: Perform a virtual screen of the entire library against the target's binding site using standardized docking parameters.

- Analysis: Calculate enrichment metrics (e.g., EF1% - enrichment factor at 1% of the screened library, ROC-AUC - Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) to assess the method's ability to prioritize known actives over decoys.

Protocol B: Pose Prediction Validation

- Dataset Curation: Compile a set of high-resolution protein-ligand co-crystal structures from the PDB.

- Re-docking: Separate the ligand from the protein, then use the docking program to re-predict the binding pose.