Troubleshooting Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Convergence: A Practical Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence in ab initio electronic structure calculations.

Troubleshooting Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Convergence: A Practical Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence in ab initio electronic structure calculations. It covers foundational SCF principles, advanced convergence acceleration algorithms like DIIS and LSMO, and systematic troubleshooting protocols for challenging systems, including multireference cases. A comparative analysis of self-consistent versus non-self-consistent methods highlights their impact on the accuracy of computed properties, such as magnetic exchange parameters. The content is tailored to support reliable simulations in biomedical research, including drug design and materials discovery.

Understanding SCF Convergence: Core Principles and Common Pitfalls

FAQ: Understanding SCF Convergence

What is the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure?

The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure is an iterative method in quantum chemistry where the Kohn-Sham equations in Density Functional Theory (DFT) must be solved self-consistently. The Hamiltonian depends on the electron density, which in turn is obtained from the Hamiltonian. This creates an iterative loop (the SCF cycle) starting from an initial guess for the electron density. The cycle involves computing the Hamiltonian, solving the Kohn-Sham equations to obtain a new density matrix, and repeating until convergence is reached [1].

What error metric is used to define SCF convergence?

The specific error metric used to monitor convergence can vary between different computational chemistry packages. Common metrics include:

- Density Matrix Change: The maximum absolute difference (dDmax) or the root-mean-square change between the output and input density matrices from one cycle to the next [2] [1].

- Commutator-based Error: The commutator of the Fock matrix (F) and the density matrix (P), [F,P]. Convergence is often considered reached when the maximum element of this commutator falls below a specified threshold [3].

- Hamiltonian Change: The maximum absolute difference in the Hamiltonian matrix (dHmax) between SCF cycles [1].

- Energy Change: The change in the total SCF energy between successive iterations [4].

Most programs employ a combination of these metrics to determine convergence.

What are typical numerical values for SCF convergence criteria?

Convergence criteria are not universal; they depend on the software and the desired precision. The tables below summarize typical values.

Table 1: ORCA SCF Convergence Tolerances (in Hartree) [4]

| Criterion | Description | Loose | Medium (Default) | Tight | VeryTight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

TolE |

Energy change between cycles | 1e-5 | 1e-6 | 1e-8 | 1e-9 |

TolMaxP| Maximum density change |

1e-3 | 1e-5 | 1e-7 | 1e-8 | |

TolRMSP |

RMS density change | 1e-4 | 1e-6 | 5e-9 | 1e-9 |

TolErr |

DIIS error | 5e-4 | 1e-5 | 5e-7 | 1e-8 |

Table 2: BAND Default Convergence Criterion [2]

The default criterion is scaled with system size: Criterion = 1e-6 * sqrt(N_atoms) for "Normal" numerical quality.

What are the physical reasons for SCF convergence failures?

Several physical and numerical factors can prevent SCF convergence:

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: This is a primary physical reason [5]. A small gap can cause:

- Occupation Oscillations: Frontier orbital occupation numbers may change repetitively between cycles if their energies are very close [5].

- Charge Sloshing: Long-wavelength oscillations of the electron density can occur due to small changes in the input density, leading to slow convergence or divergence [6] [5].

- Metallic and Magnetic Systems: Systems with delocalized electrons (like metals) or complex magnetic states (especially antiferromagnetism and noncollinear magnetism) are often challenging due to the presence of many states near the Fermi level [6] [1].

- Poor Initial Guess: A poor starting guess for the electron density can lead the SCF procedure down a path to divergence or slow convergence [7].

- Numerical Issues: An insufficiently accurate integration grid, a basis set that is close to linear dependence, or an integral cutoff threshold that is too loose can introduce noise that prevents convergence [5].

What practical steps can I take to improve SCF convergence?

When facing SCF convergence problems, a systematic approach is best. The following workflow outlines a practical troubleshooting methodology adapted from expert recommendations [5] [3] [1].

Detailed Protocols:

- Improve the Initial Guess: If a simple superposition of atomic densities fails, consider using fragment orbitals or molecular orbital projection methods. Machine learning models are also emerging to provide better initial guesses [7].

- Apply Smearing: Using a finite electronic temperature (e.g., Fermi-Dirac smearing) to fractionally occupy orbitals around the Fermi level can stabilize convergence for systems with small gaps [2] [5].

- Adjust the Mixing Scheme:

- Increase History: For Pulay/DIIS or Broyden methods, increase the number of previous cycles stored (

SCF.Mixer.Historyin SIESTA,DIIS Nin ADF) [3] [1]. For difficult systems, values between 12 and 20 can be effective [3]. - Change the Algorithm: If Pulay/DIIS fails, try Broyden mixing, which can be more effective for metallic and magnetic systems [1]. Alternatively, algorithms like ADIIS or LIST methods can be more robust [3].

- Increase History: For Pulay/DIIS or Broyden methods, increase the number of previous cycles stored (

- Use Damping and Level Shifting:

- Reduce Mixing Weight: Using a smaller damping factor (e.g.,

Mixing 0.1orSCF.Mixer.Weight 0.1) can prevent oscillations, though it may slow convergence [3] [1]. - Level Shifting: Applying level shifting (in codes that support it) raises the energy of virtual orbitals, which can prevent charge sloshing between near-degenerate orbitals [3].

- Reduce Mixing Weight: Using a smaller damping factor (e.g.,

- Check Numerical Settings: Ensure the integral evaluation threshold and the DFT integration grid are sufficiently tight. If the numerical error is larger than the SCF convergence criterion, convergence is impossible [4] [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential SCF Aids

Table 3: Key Solutions for SCF Convergence Problems

| Solution | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pulay/DIIS | Accelerates convergence by building an optimized linear combination of previous Fock/Density matrices. | Default in many codes. Sensitive to the number of history vectors stored [3] [1]. |

| Broyden Mixing | A quasi-Newton scheme that updates mixing using approximate Jacobians. | Often performs similarly to Pulay; can be superior for metallic/magnetic systems [1]. |

| Fermi-Dirac Smearing | Applies a finite electronic temperature to fractionally occupy orbitals near the Fermi level. | Smoothens energy landscape, resolving oscillations from near-degenerate states [2] [5]. |

| Level Shifting | Artificially raises the energy of unoccupied (virtual) orbitals. | Prevents charge sloshing by stabilizing the orbital energy hierarchy [3]. |

| ADIIS | An energy-based DIIS variant that is often more robust than standard Pulay DIIS. | Can be combined with Pulay DIIS (e.g., ADIIS+SDIIS). Effective for difficult initial convergence [3]. |

# Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure and why does convergence matter? The Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure is an iterative method used in quantum chemistry calculations, such as Hartree-Fock and Density Functional Theory, to find a consistent electronic density. It works by repeatedly solving the Fock (or Kohn-Sham) equations until the input and output densities stop changing significantly [2] [8]. Convergence is crucial because a non-converged SCF calculation means the electronic ground state has not been found, and the resulting energies and properties are unreliable and potentially meaningless [9].

2. How does Numerical Quality directly influence my SCF convergence? Numerical Quality settings control the accuracy of various numerical integrations and approximations in the calculation. Higher numerical quality typically leads to more accurate results but at a greater computational cost. Crucially, these settings directly determine the default convergence criterion for the SCF procedure. Using a "Basic" numerical quality will result in a looser convergence threshold, while "VeryGood" will enforce a much stricter one, impacting both the required number of iterations and the final accuracy of your result [2].

3. My SCF calculation won't converge. What are the first things I should check? Start with these fundamental steps:

- Verify your initial guess: A poor initial density guess is a common culprit. Try switching from a simple atomic superposition (

rho) to one constructed from atomic orbitals (psi) or, if available, use a previously converged calculation as a restart [2] [8]. - Inspect your system: Check for issues with your molecular structure, such as unrealistic geometries or incorrect charge/spin states, which can make convergence difficult [10].

- Adjust basic SCF parameters: You can often help convergence by increasing the maximum number of SCF cycles (

Iterations) [2] or relaxing the convergence criterion (CriterionorSCF_CONVERGENCE), though the latter should be done with caution [2] [10] [11].

4. What advanced SCF algorithms can I use to overcome convergence problems? If basic fixes fail, consider changing the SCF optimization algorithm [11]:

- DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace): This is the default in many codes and is highly efficient but can sometimes fail or oscillate [8] [11].

- Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM): A robust alternative to DIIS, often recommended as a fallback. A hybrid

DIIS_GDMmethod uses DIIS initially and then switches to GDM for stable convergence [11]. - Second-Order SCF (SOSCF): Methods like Newton's method can provide quadratic convergence but are more computationally expensive per iteration [8].

- Level Shifting: Artificially increases the energy of virtual orbitals, widening the HOMO-LUMO gap to prevent oscillation in systems with small gaps [8] [12].

5. For a system with a small HOMO-LUMO gap, what specific techniques can help? Metallic systems or those with near-degenerate frontier orbitals are notoriously challenging. Specific strategies include:

- Fermi Broadening / Smearing: Applying a finite electronic temperature to fractionally occupy orbitals around the Fermi level, which stabilizes the SCF procedure [2] [8].

- Level Shifting: As mentioned above, this is particularly effective for small-gap systems [8] [12].

- Damping: Mixing a small fraction of the new Fock matrix with the old one (

Mixing) can slow down updates and prevent oscillations in the early stages of the SCF cycle [2] [8].

# Troubleshooting Guide: Solving SCF Convergence Failures

Initial Assessment and Basic Checks

- Confirm the Problem: Check your output log for explicit warnings about SCF non-convergence [9].

- System Geometry: Ensure your molecular geometry is physically reasonable. Slight distortions can sometimes hinder convergence [10].

- Charge and Spin: Verify that the specified charge and spin multiplicity of your system are correct.

Systematic Protocol for Remediation

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and fix SCF convergence issues. Begin with the initial assessment and proceed to more advanced techniques as needed.

Step 1: Improve the Initial Guess

The initial electron density guess is critical for a stable SCF process.

- Default Methods: The

minaoor atomic superposition (rho) guesses work well for standard systems [8] [2]. - Advanced Methods: For difficult cases, try the

huckelguess or theatom-based superposition scheme [8]. - Restart from Calculation: The most effective method is often to use a converged density from a previous calculation on the same or a similar system as the new initial guess (

guess=readorinit_guess=chk) [8] [10]. You can also use a calculation from a smaller basis set or a different charge state as a starting point [8].

Step 2: Adjust the SCF Algorithm and Convergence Parameters

If an improved guess does not suffice, modify the SCF solution procedure itself.

- Switch Algorithms: If the default

DIISmethod fails, tryMultiSecantorMultiStepperalternatives [2], or switch to the more robustGDM(Geometric Direct Minimization) [11]. - Use Hybrid Methods: Employ a hybrid approach like

DIIS_GDM, which uses fast DIIS initially and then switches to stable GDM as convergence is approached [11]. - Control DIIS Manually: You can reduce the size of the DIIS subspace (

DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZE) or adjust damping parameters within the DIIS algorithm to improve stability [2] [11]. - Increase Iterations: Simply increasing the

MAX_SCF_CYCLESorIterationslimit can sometimes resolve slow convergence [12] [2].

Step 3: Advanced Techniques for Difficult Cases

- For Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps: Employ

Fermismearing orDegenerateoccupation number smoothing [8] [2]. TheLEVEL_SHIFTkeyword can also be used to artificially increase the energy gap [12] [11]. - Final Numerical Precision: For publication-quality results, use a

NumericalQualityofGoodorVeryGoodand a tightSCF_CONVERGENCEcriterion (e.g., 1e-7 or 1e-8) [2] [11].

# The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Parameters for SCF Control

The following table summarizes critical parameters available in major computational codes that you can adjust to manage SCF convergence.

| Parameter Name | Function / Purpose | Typical Code Availability |

|---|---|---|

| NumericalQuality | Sets the overall accuracy of numerical integration and the default SCF convergence criterion. Directly impacts cost/accuracy [2]. | BAND, SCM |

| SCF_CONVERGENCE / Criterion | The target threshold for the SCF error. Reaching this threshold means the calculation is converged [2] [11]. | Q-Chem, BAND, CP2K, Gaussian |

| SCF_ALGORITHM / Method | Chooses the algorithm for converging the density (e.g., DIIS, GDM, MultiStepper) [11] [2]. |

Q-Chem, BAND, PySCF |

| Initial Guess (init_guess) | Method to generate the starting density (e.g., minao, huckel, atomic, from chkfile) [8]. |

PySCF, CP2K, Gaussian |

| Mixing / Damp | The fraction of the new Fock matrix mixed into the old one for the next iteration. A lower value can stabilize shaky convergence [2] [8]. | BAND, PySCF |

| Level_Shift | Increases the energy of virtual orbitals to suppress mixing with occupied ones, helping convergence in small-gap systems [12] [11]. | CP2K, Q-Chem |

| DIISSUBSPACESIZE / MAX_DIIS | Controls the number of previous steps used in the DIIS extrapolation. A smaller subspace can be more stable [11]. | Q-Chem, CP2K |

| Electronic Temperature | Smears orbital occupations via a finite temperature, stabilizing metallic and small-gap systems [2] [9]. | BAND, QuantumATK |

# The Interplay of Numerical Quality and Convergence

The NumericalQuality keyword is a master setting that governs multiple numerical aspects of a calculation. Its direct link to the SCF convergence threshold is detailed in the table below, which is based on the implementation in the BAND code. Other codes use similar logic, though the exact values may differ [2].

Table: Default SCF Convergence Criterion vs. Numerical Quality (BAND code)

| Numerical Quality Setting | Default Convergence Criterion | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Basic | 1e-5 × √Natoms | Initial tests, very large systems |

| Normal | 1e-6 × √Natoms | Standard single-point calculations |

| Good | 1e-7 × √Natoms | Geometry optimizations, finer properties |

| VeryGood | 1e-8 × √Natoms | High-precision work, frequency analysis |

This multiplicative formulation means that the convergence criterion automatically becomes stricter for larger systems, ensuring consistent overall accuracy. When reporting results, it is essential to state the NumericalQuality and SCF convergence criteria used to allow for proper reproducibility [2] [11].

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common symptoms of SCF convergence failure? The most obvious sign is that the SCF iterations reach the maximum cycle limit without meeting the convergence criteria. The SCF energy may oscillate between values, diverge to infinity, or get trapped in a cyclic pattern without settling to a minimum. In ORCA, calculations are categorized as "complete SCF convergence," "near SCF convergence," or "no SCF convergence," and the program will typically stop to prevent using unreliable results [13].

Which types of chemical systems are most prone to SCF convergence problems? Convergence problems are frequently encountered in systems with:

- Very small HOMO-LUMO gaps, such as metallic systems or large conjugated molecules [14].

- Localized open-shell configurations, often found in systems with d- and f-elements [14].

- Transition metal complexes, particularly open-shell species [13].

- Transition state structures with dissociating bonds [14].

- Systems calculated with large, diffuse basis sets, which can lead to linear dependencies [13].

My calculation is oscillating wildly. What should I try first? For oscillating behavior, increasing the damping is a common first step. This can be done by using the

! SlowConvor! VerySlowConvkeywords in ORCA [13] or by reducing theMixingparameter in ADF (e.g., to 0.015) to make the convergence more stable and less aggressive [14].What can I do if my initial guess is poor? You can generate a better initial guess by:

- Performing a calculation with a simpler, more robust method (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP or HF/def2-SVP) and reading its orbitals into the more complex calculation using the

! MOReadkeyword [13]. - Trying alternative initial guesses like

PAtom,Hueckel, orHCoreinstead of the defaultPModelguess [13]. - For open-shell systems, try converging a closed-shell, oxidized state first and then using those orbitals as a starting point [13].

- Performing a calculation with a simpler, more robust method (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP or HF/def2-SVP) and reading its orbitals into the more complex calculation using the

When should I consider using electron smearing or level shifting? Electron smearing is particularly helpful in larger systems with many near-degenerate levels, as fractional orbital occupancies can help overcome convergence barriers. The smearing value should be kept as low as possible [14]. Level shifting can also overcome convergence issues but should be used with caution as it artificially raises the energy of virtual orbitals and can give incorrect results for properties like excitation energies or NMR shifts [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Approach

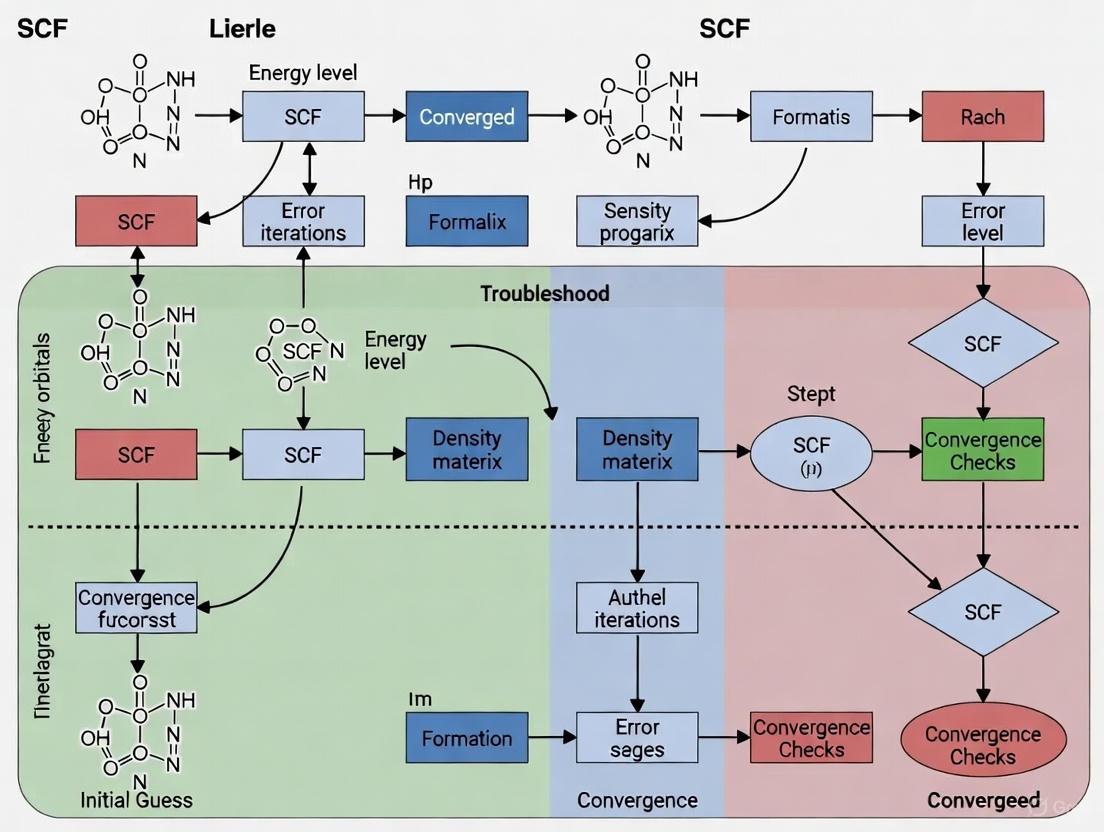

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for diagnosing and resolving SCF convergence issues.

Foundational Checks

Before adjusting advanced settings, always verify the basics.

- Input Geometry: Ensure bond lengths and angles are realistic and that no atoms are missing from the input structure [14]. A high-energy or non-physical geometry is a common root cause.

- Spin and Multiplicity: Confirm that the correct spin multiplicity is used for open-shell systems. An improper description can lead to strong fluctuations in the SCF error [14].

Algorithm Switching

If foundational checks pass, try a more robust SCF algorithm. The default DIIS method is efficient but not always reliable.

- For difficult systems like open-shell transition metal complexes, use built-in keywords like

! SlowConvin ORCA [13] or switch to alternative accelerators like MESA or LISTi in ADF [14]. - For pathological cases, second-order convergence methods are recommended. The Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) in ORCA is robust but more expensive [13]. Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM), particularly the

DIIS_GDMhybrid algorithm in Q-Chem, is also highly recommended for robustness [11].

Parameter Tuning

Fine-tuning SCF parameters can stabilize convergence. The table below summarizes key parameters for a "slow but steady" convergence strategy.

| Parameter | Software | Standard Value | Adjusted Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DIIS Subspace Size (N, DIIS_SUBSPACE_SIZE) |

ADF [14], Q-Chem [11] | 5-15 | 25-40 | Increases stability by using more previous Fock matrices for extrapolation. |

Mixing Factor (Mixing) |

ADF [14] | 0.2 | 0.015 | Reduces the fraction of the new Fock matrix, increasing damping and stability. |

Max SCF Iterations (MAX_SCF_CYCLES, MaxIter) |

Q-Chem [11], ORCA [13] | 50-125 | 500-1500 | Allows more iterations for very slow-converging systems. |

DIIS Start Cycle (Cyc) |

ADF [14] | 5 | 30 | Delays the start of aggressive DIIS, allowing for more initial equilibration. |

Advanced Techniques

For persistently problematic cases, these techniques can help, but they may slightly alter the final result and require careful testing.

- Electron Smearing: Applies a finite electronic temperature, using fractional occupation numbers to populate near-degenerate orbitals. This is very effective for systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps [14].

- Level Shifting: Artificially raises the energy of unoccupied orbitals to facilitate convergence. This technique is not recommended for calculations of properties that involve virtual orbitals, such as excitation energies [14].

- Improved Initial Guess: Using the converged orbitals from a previous calculation as a starting point (

MORead) is often one of the most effective strategies [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential SCF Convergence Aids

The following table catalogs key software options and algorithmic "reagents" used to diagnose and remedy SCF convergence problems.

| Tool / Option | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS (Default) | Standard acceleration method; extrapolates a new Fock matrix from a linear combination of previous ones. [11] | Fast convergence for well-behaved, closed-shell organic molecules. |

| TRAH / GDM | Robust, second-order convergence algorithms. They are more expensive per iteration but far more stable for difficult cases. [13] [11] | Primary fallback when DIIS fails; recommended for restricted open-shell and transition metal systems. |

| Mixing Factor | Controls the fraction of the new Fock matrix used in the next iteration. Lower values increase damping. [14] | Stabilizes oscillating SCF procedures. |

| Electron Smearing | Smears electrons over orbitals with a finite temperature, helping to occupy near-degenerate levels. [14] | Converging metallic systems, radicals, and molecules with small HOMO-LUMO gaps. |

| MORead / Restart | Uses orbitals from a previous calculation as the initial guess, providing a better starting point. [13] | Restarting a failed calculation or beginning a high-level computation with a low-level guess. |

| SlowConv / VerySlowConv | Keywords that automatically apply stronger damping parameters. [13] | Standard first attempt for converging transition metal complexes and other difficult open-shell systems. |

Advanced Algorithms and Techniques for Accelerating SCF Convergence

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My SCF calculation is oscillating and won't converge. What is happening and which accelerator should I use?

A: Oscillations often occur when the system has a small HOMO-LUMO gap, leading to "charge sloshing" where the electron density changes significantly between iterations [5]. In such cases:

- Initial Stages: Use EDIIS or ADIIS to drive the energy down and bring the calculation into a convergent region [15].

- Near Convergence: Switch to the standard DIIS method for fine-tuning, as it excels at minimizing the orbital gradient once the density is close to the solution [15].

- Recommended Strategy: Implement a combined "ADIIS+DIIS" or "EDIIS+DIIS" approach, which is highly reliable and efficient [15].

Q2: What are the main physical reasons that cause an SCF calculation to fail entirely?

A: Beyond numerical issues, the primary physical reasons are [5]:

- Small or Zero HOMO-LUMO Gap: This makes the system highly polarizable and prone to large density oscillations. It can be caused by stretched molecular geometries, incorrect spin states, or artificially imposed high symmetry [5].

- Poor Initial Guess: An initial density matrix that is too far from the true solution, especially for systems with unusual charge, spin states, or metal centers, can prevent convergence [5].

- Incorrect System Setup: A molecular geometry that is chemically nonsensical (e.g., atoms too close or too far apart) or an incorrect total charge can lead to failure [5].

Q3: How does the ODA method fit in with DIIS-based approaches?

A: The Optimal Damping Algorithm (ODA) is a direct minimization approach that guarantees convergence to the energy minimum by updating the density matrix with an optimal step size [15]. The energy function used in EDIIS is derived from the ODA formalism [15]. While ODA is robust, DIIS-based methods are often faster. ODA can be a valuable fallback when DIIS-based methods struggle.

Troubleshooting Guide: SCF Non-Convergence

Use this workflow to diagnose and resolve common SCF convergence problems:

Comparison of SCF Convergence Accelerators

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different convergence accelerators for easy comparison.

| Method | Full Name | Objective Function | Key Principle | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS [15] | Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace | Commutator of Fock & Density Matrices ([F, D]) | Minimizes the orbital rotation gradient | Fast convergence when close to the solution |

| EDIIS [15] | Energy-DIIS | Quadratic Energy Function | Directly minimizes an approximate energy expression | Bringing the calculation from a poor guess into a convergent region |

| ADIIS [15] | Augmented DIIS | Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) Energy Function | Minimizes a robust quadratic energy function based on a Taylor expansion | Robust convergence for challenging cases; often combined with DIIS |

| ODA [15] | Optimal Damping Algorithm | Total Energy | Uses optimal step size to ensure monotonic energy decrease | A robust fallback when other methods diverge |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for SCF Calculations

| Item / Concept | Function / Role in SCF |

|---|---|

| Fock Matrix (F) [15] | The central matrix in SCF, representing the effective one-electron operator. It is built from the current electron density. |

| Density Matrix (P) [15] | Describes the electron distribution. It is constructed from the molecular orbital coefficients and must satisfy idempotency, trace, and symmetry constraints. |

| Overlap Matrix (S) | Accounts for the non-orthogonality of atomic basis functions. Essential for solving the generalized eigenvalue problem. |

| HOMO-LUMO Gap [5] | The energy difference between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals. A small gap is a common physical cause of convergence difficulties. |

| Initial Guess [5] | The starting point for the electron density (e.g., from a superposition of atomic densities). A poor guess is a major cause of non-convergence. |

| Basis Set | A set of basis functions (e.g., Gaussian-Type Orbitals) used to expand the molecular orbitals. A nearly linearly dependent set can cause numerical instability [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary advantages of using the LSMO and MultiStepper methods for ab initio molecular dynamics? The primary advantage is a significant reduction in computational cost while maintaining accuracy comparable to conventional electronic structure methods. The LSMO method acts as a computationally efficient surrogate, predicting the one-electron reduced density matrix (1-RDM) with an accuracy that deviates from fully converged results by no more than a standard self-consistent field (SCF) threshold [16]. When combined with a force-correction algorithm, this enables stable ab initio molecular dynamics for larger molecules, such as biphenyl [16].

2. My SCF calculations using these advanced methods fail to converge. What are the first parameters I should check? Initial troubleshooting should focus on the foundational aspects of your SCF calculation. First, verify the quality and size of your atomic basis set, as linear dependencies within it can lead to convergence difficulties [17]. Second, analyze your initial guess for the density matrix; a poor initial guess can prevent the iterative process from finding the energy minimum [17]. Finally, ensure that your direct minimization or iterative diagonalization routines are properly configured, as the method of solution impacts stability [17].

3. How does the LSMO method achieve faster convergence compared to traditional SCF solvers? The LSMO method bypasses the traditional iterative SCF process altogether. Instead of solving the SCF equations repeatedly, a machine-learned model directly maps the electron-nuclear interaction potential to the 1-RDM [16]. This surrogate model is trained to produce 1-RDMs that are already at SCF convergence thresholds, effectively eliminating the convergence loop and its associated computational expense [16].

4. When should a researcher consider using the MultiStepper technique? The MultiStepper technique is particularly valuable in systems where the SCF energy landscape is complex and riddled with multiple local minima, which can trap standard solvers. It is a system-specific approach designed to navigate this challenging landscape more effectively than generic convergence accelerators [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving SCF Convergence Failures in MultiStepper Simulations

The MultiStepper approach is designed for difficult systems, but it can still encounter convergence failures. Below is a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving these issues.

Recommended Actions:

- Check Initial Guess Density: A poor initial guess is a common culprit. For complex systems, do not rely on a default guess. Use a superposition of atomic densities or a result from a lower level of theory (e.g., semi-empirical methods) to provide a better starting point for the MultiStepper algorithm [17].

- Analyze Basis Set for Linear Dependencies: Overly large or poor-quality basis sets can contain linear dependencies, making the SCF equations ill-conditioned and difficult to solve. Employ canonical orthogonalization to eliminate these dependencies and create a more stable numerical foundation for the calculation [17].

- Inspect SCF Energy Stability: Perform a stability analysis on the converged wavefunction. If an unstable state is found, it indicates the calculation has settled in a local minimum or saddle point, not the true ground state. Use this unstable solution as a new initial guess and restart the SCF procedure to guide it toward the true ground state [17].

- Adjust MultiStepper Internal Parameters: The MultiStepper method likely has internal parameters controlling its step size and tolerance. If the system is particularly stiff or the energy landscape is very rough, tightening the convergence thresholds for the inner loops or reducing the maximum step size can prevent the solver from overshooting the minimum [18].

Guide 2: Implementing and Validating the LSMO Method for MD

Successfully using the Machine-Learned 1-RDM for dynamics requires careful validation.

Implementation Protocol:

- Obtain/Generate a Targeted Training Set: Contrary to using massive datasets, recent optimizations show that smaller, targeted training sets are sufficient. Focus on generating a set that maps a diverse range of electron-nuclear interaction potentials to their fully converged 1-RDMs for molecules relevant to your study [16].

- Train Model to SCF Convergence Threshold: The key performance metric for the model is its deviation from the fully converged 1-RDM. The model must be trained to an accuracy where this deviation is within standard SCF convergence thresholds (e.g., 10⁻⁶ a.u. for energy), ensuring it is a valid surrogate for the true SCF solution [16].

- Validate on Hold-Out Molecular Systems: Before proceeding to dynamics, rigorously validate the machine-learned 1-RDM on molecular structures not seen during training. Compare properties like dipole moments, orbital energies, and reaction energies against conventional SCF results to ensure transferability [16].

- Apply Force-Correction Algorithm: Raw forces derived from the machine-learned 1-RDM may contain small errors that lead to unstable molecular dynamics trajectories. Implement a force-correction algorithm to compensate for these errors, which is crucial for achieving stable, long-time-scale simulations [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key computational "reagents" and their functions in the featured methodologies.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Targeted Training Set | A curated set of molecular examples used to train the LSMO model. Its function is to enable high accuracy with fewer data points by focusing on chemically relevant configurations [16]. |

| Force-Correction Algorithm | A necessary post-processing step for dynamics. It corrects small errors in the forces predicted by the machine-learned 1-RDM, ensuring energy conservation and stable molecular dynamics trajectories [16]. |

| Stability Analysis | A diagnostic procedure applied to a converged wavefunction. Its function is to determine if the SCF solution is a true ground state or an unstable state, guiding further optimization efforts [17]. |

| Canonical Orthogonalization | A mathematical procedure using the overlap matrix eigenvalues. Its function is to eliminate linear dependencies in the atomic basis set, improving the numerical conditioning of the SCF equations [17]. |

| Initial Guess Density | The starting point for the SCF iterative procedure. A better guess, such as from a superposition of atomic densities, functions to precondition the calculation and guide it more efficiently toward convergence [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my SCF calculation for an open-shell transition metal complex fail to converge?

SCF convergence in open-shell transition metal complexes is challenging due to their complex electronic structure. The primary reasons include:

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: This can cause oscillations in orbital occupation numbers or "charge sloshing," where the electronic density oscillates between iterations [5].

- Poor Initial Guess: The default initial guess may be inadequate for systems with significant electron correlation or unusual spin states [13] [5].

- High Symmetry: Imposing incorrect or artificially high symmetry can sometimes lead to a zero HOMO-LUMO gap, preventing convergence [5].

Q2: What is a "multireference" system, and why does it require special treatment?

A multireference system is one where the electronic wavefunction cannot be accurately described by a single Slater determinant (e.g., the Hartree-Fock state). This is common in strongly correlated systems, such as molecules with stretched bonds, diradicals, or some transition metal complexes [19]. Standard single-reference error mitigation and computational methods become unreliable in these cases because they assume the reference state has good overlap with the true ground state [19]. Specialized methods, like those using multireference states, are needed to capture the correct physics.

Q3: My calculation using a large, diffuse basis set won't converge. What should I check?

Diffuse basis sets increase the risk of two specific problems:

- Linear Dependence: The basis functions can become nearly linearly dependent, leading to numerical instability and convergence failure [5].

- Numerical Noise: An integration grid that is too small or loose integral cutoffs can introduce numerical noise that prevents convergence [10] [5]. Symptoms include energy oscillations with a very small magnitude (<10⁻⁴ Hartree) [5].

Q4: Are there specific strategies for converging metallic systems?

Metallic systems are characterized by a very small or zero HOMO-LUMO gap, which makes the SCF procedure highly susceptible to charge sloshing [5]. Convergence can often be achieved by:

- Using Fermi broadening (

SCF=Fermiin Gaussian) to smear the orbital occupations [10]. - Employing damping or mixing schemes to suppress oscillations in the density [20].

- Utilizing robust second-order convergence algorithms like the Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) available in ORCA [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

A Systematic Workflow for SCF Convergence

When your SCF calculation fails to converge, follow this logical troubleshooting pathway. The diagram below outlines the key steps, from simple checks to advanced techniques.

Troubleshooting Specific System Types

Different types of complex systems require targeted strategies. The table below summarizes common issues and recommended solutions for open-shell, metallic, and multireference cases.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Complex Systems

| System Type | Common Convergence Issues | Recommended Strategies & Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| Open-Shell Systems | Small HOMO-LUMO gap; oscillating spin density [5]. | - Level Shift: SCF=vshift=300 (Gaussian) [10].- Damping: Use !SlowConv or !VerySlowConv in ORCA [13].- Initial Guess: Converge a closed-shell cation first, then read orbitals with guess=read [10]. |

| Metallic Systems | Vanishing HOMO-LUMO gap leading to severe "charge sloshing" [5]. | - Fermi Smearing: SCF=Fermi (Gaussian) or !Fermi (ORCA) [10] [13].- Mixing/Damping: Increase damping factors or use specialized mixing algorithms [20].- KDIIS Algorithm: Try !KDIIS in ORCA [13]. |

| Multireference Systems | Single-determinant reference state is a poor approximation, making error mitigation and energy convergence difficult [19]. | - Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM): Use a linear combination of Slater determinants as a reference [19].- Specialized Methods: Utilize CASSCF or other multiconfigurational approaches. |

| Systems with Diffuse Functions | Near-linear dependence in the basis set; numerical noise [5]. | - Integration Grid: Use a finer grid (int=ultrafine in Gaussian) [10].- SCF Settings: SCF=NoVarAcc to stop grid reduction (Gaussian) [10].- Linear Dependence: Remove redundant basis functions. |

Advanced Protocol: Multireference State Error Mitigation (MREM)

For strongly correlated systems where single-reference methods fail, Multireference State Error Mitigation (MREM) offers a advanced solution, particularly in quantum computing algorithms like VQE [19].

Objective: To systematically capture quantum hardware noise in strongly correlated ground states by utilizing multireference states, thereby improving computational accuracy [19].

Methodology:

- State Selection: Generate an approximate multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants from inexpensive conventional methods. These states are engineered to have substantial overlap with the target ground state [19].

- State Preparation: Use Givens rotations to efficiently construct quantum circuits that prepare the selected multireference states on quantum hardware. This method is chosen for its efficiency, symmetry preservation (particle number, spin), and controlled expressivity [19].

- Error Mitigation: Execute the error mitigation protocol by leveraging the prepared multireference states to systematically capture and correct for hardware noise, significantly improving the accuracy of computed energies compared to single-reference REM [19].

Validation: This protocol has been demonstrated to yield significant improvements for molecular systems like H₂O, N₂, and F₂ in their bond-stretching regions, where electron correlation is pronounced [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for handling complex systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Keyword | Software | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

SCF=vshift=x |

Gaussian | Applies an energy level shift to virtual orbitals, increasing the HOMO-LUMO gap to aid convergence in systems with small gaps (e.g., containing transition metals) [10]. |

SCF=QC |

Gaussian | Uses a more robust but computationally expensive quadratic convergence method to overcome difficult SCF convergence [10]. |

SCF=Fermi |

Gaussian | Introduces Fermi broadening, smearing orbital occupations to help converge metallic systems or those with a very dense density of states [10]. |

guess=read |

Gaussian, ORCA (!MORead) |

Reads the molecular orbitals from a previous calculation, providing a high-quality initial guess to overcome poor convergence [10] [13]. |

!SlowConv / !VerySlowConv |

ORCA | Increases damping parameters to suppress large fluctuations in the initial SCF iterations, crucial for transition metal complexes and other difficult cases [13]. |

!KDIIS |

ORCA | Employs the KDIIS algorithm as an alternative to DIIS, which can sometimes lead to faster and more reliable convergence [13]. |

| Givens Rotations | Quantum Algorithms | A circuit primitive used to efficiently prepare multireference states (linear combinations of Slater determinants) on quantum hardware for error mitigation in strongly correlated systems [19]. |

| Multireference States | General | A wavefunction composed of multiple Slater determinants, used as a superior reference for error mitigation and correlation treatment in systems where a single determinant fails [19]. |

A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Protocol for Stubborn SCF Cases

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General SCF Convergence Questions

Q1: What are the most common physical reasons for SCF convergence failures? SCF convergence failures typically occur due to several physical and numerical factors:

- Small HOMO-LUMO gap: This can cause oscillations in frontier orbital occupation numbers as electrons transfer between nearly degenerate orbitals [5].

- Charge sloshing: In systems with high polarizability, small errors in the Kohn-Sham potential cause large density distortions, leading to oscillatory behavior [5].

- Poor initial guess: Starting with a molecular geometry or electron density that is too far from the true solution [5].

- Incorrect symmetry: Imposing artificially high symmetry can lead to zero HOMO-LUMO gaps and convergence problems [5].

- Numerical issues: These include basis set linear dependence or insufficient integration grids [5].

Q2: How can I identify the specific type of convergence problem I'm experiencing? Different convergence failures exhibit distinct signatures:

- Oscillating energy (10⁻⁴ to 1 Hartree amplitude) with wrong occupation pattern: Indicates small HOMO-LUMO gap and occupation switching [5].

- Oscillating energy with smaller amplitude but correct occupation: Suggests charge sloshing with orbital shape oscillations [5].

- Very small energy oscillations (<10⁻⁴ Hartree) with correct occupation: Points to numerical noise from insufficient grids or integral cutoffs [5].

- Wildly oscillating or unrealistically low energy: Often caused by basis set linear dependence [5].

Initial Guess Strategies

Q3: What initial guess strategies are available for challenging systems? For systems where standard atomic superposition guesses fail:

- Semiempirical methods: Perform cheap semiempirical calculations to generate improved starting densities, adding significant level shifts (e.g., 1.0 au) to ensure convergence [5].

- Mixed references: For open-shell systems, mixed-reference approaches can provide better starting points [21].

- Complex orbital coefficients: In some challenging cases, using complex rather than real orbital coefficients can improve convergence, even without magnetic fields [17].

Q4: How does molecular geometry affect initial guess quality? Molecular geometry critically impacts initial guess effectiveness:

- Stretched bonds: Excessively long bonds reduce orbital overlap, making atomic superposition guesses less effective and decreasing HOMO-LUMO gaps [5].

- Compressed bonds: Too-short bonds increase the risk of basis set linear dependence [5].

- Coordinate systems: The choice of coordinate system can significantly affect convergence, with mixed Cartesian and redundant coordinates sometimes performing better for molecular complexes [5].

Spin-Related Strategies

Q5: What are SpinFlip strategies and when should I use them? SpinFlip strategies address specific electronic structure challenges:

- Open-shell singlets: Effectively describes diradicals and bond-breaking situations where single-reference methods struggle [21].

- Conical intersections: Properly describes topological features where potential energy surfaces meet [21].

- Doubly-excited states: Accounts for excitation types missing in conventional linear-response TDDFT [21].

- High-spin triplet references: Uses MS = ±1 triplet references to generate ground singlet states as response states [21].

Q6: What spin contamination problems can occur and how are they addressed? Traditional SpinFlip methods can introduce significant spin contamination:

- Unequal contributions: From distinct spin-flip transitions leading to spin contamination [21].

- Mixed-reference solution: Averages contributions from MS = +1 and -1 components to nearly eliminate spin contamination [21].

- Decoupled equations: Mixed-reference spin-flip TDDFT yields separate equations for singlet and triplet states, reducing contamination [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Initial Guess Optimization Protocol

Diagnosing and resolving initial guess problems:

Initial Guess Optimization Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Diagnose oscillation pattern: Examine SCF energy convergence behavior and orbital occupations to identify the failure type [5].

- Verify molecular geometry: Check for unrealistic bond lengths, angles, or incorrect units (e.g., Ångstroms instead of Bohr) [5].

- Assess basis set quality: Check for linear dependencies, especially with compressed bonds or large basis sets [5].

- Implement alternative initial guess:

- For stretched molecules: Use semiempirical methods with large level shifts [5]

- For metal complexes: Consider fragment guesses or broken-symmetry approaches

- Apply convergence helpers: Use damping, DIIS, or level shifting as needed [5]

- Verify final convergence: Check density matrix stability and energy consistency

SpinFlip Implementation Guide

Implementing SpinFlip strategies for challenging systems:

SpinFlip Strategy Selection Guide

Implementation Protocol:

- System assessment: Identify which electronic structure challenge is present:

Method selection:

Reference state preparation: Use appropriate high-spin triplet reference states (MS = ±1) [21]

Response calculation: Perform linear response with spin-flip excitations [21]

Result analysis: Verify spin purity and state character

Research Reagent Solutions

Computational Tools for Initial Guess Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Methods | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Guess Generators | Superposition of Atomic Potentials [5] | Creates initial density from isolated atoms | Standard molecular systems |

| Semiempirical Methods [5] | Provides improved starting orbitals | Systems with stretched bonds or small gaps | |

| Fragment Approaches | Uses molecular fragments for large systems | Biomolecules or coordination complexes | |

| SpinFlip Methods | Traditional SF-TDDFT [21] | Handles open-shell singlet cases | Diradicals, bond breaking |

| Mixed-Reference SF-TDDFT [21] | Reduces spin contamination | Challenging multireference cases | |

| High-spin triplet references [21] | Provides reference for spin-flip | Open-shell systems | |

| Convergence Accelerators | Damping/DIIS [5] | Stabilizes SCF iterations | Oscillatory convergence |

| Level Shifting [5] | Increases HOMO-LUMO gap | Near-degenerate systems | |

| Adaptive Damping [22] | Automatically adjusts step size | Problem-specific optimization |

Advanced SCF Algorithms

| Algorithm Type | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Minimization [17] | Energy minimization with orbitals | Gapped systems |

| Potential Mixing [22] | Mixing potentials with preconditioning | Metals, charge-sloshing |

| Optimal Damping (ODA) [22] | Ensures monotonic energy decrease | Guaranteed convergence |

| Adaptive Damping [22] | Automatic step size selection | High-throughput workflows |

Diagnostic Tables

SCF Failure Symptoms and Solutions

| Symptom Pattern | Probable Cause | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Large energy oscillations (10⁻⁴-1 Hartree) with occupation switching | Small HOMO-LUMO gap | Level shifting, improved initial guess, damping [5] |

| Medium energy oscillations with correct occupation | Charge sloshing | Preconditioning, density damping, DIIS [5] [22] |

| Small energy oscillations (<10⁻⁴ Hartree) | Numerical noise | Tighter integration grids, integral cutoffs [5] |

| Wild energy oscillations or unrealistic energies | Basis set linear dependence | Basis set pruning, improved basis [5] |

| Convergence to wrong state | Poor initial guess | Alternative guess strategies, fragment approaches [5] |

Mixed-Reference SpinFlip Advantages

| Aspect | Traditional SF-TDDFT | Mixed-Reference SF-TDDFT |

|---|---|---|

| Spin contamination | Significant [21] | Nearly eliminated [21] |

| Reference states | Single high-spin triplet [21] | Mixed MS = +1 and -1 components [21] |

| Configuration space | Limited [21] | Expanded [21] |

| Computational cost | Moderate | Slightly higher but practical [21] |

| Black-box applicability | Limited | High [21] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the main physical reasons an SCF calculation fails to converge? SCF failures are often not just numerical issues but are rooted in the physical nature of the system being studied. The primary physical reasons include:

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gap: Systems with a small energy difference between the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals are highly polarizable. This can lead to large oscillations in the electron density (known as "charge sloshing") or oscillations in the orbital occupation patterns, preventing convergence [5].

- Incorrect Initial Guess: A poor starting point for the electron density or density matrix can lead the SCF procedure down a path toward divergence rather than convergence. This is particularly common for systems with unusual charge or spin states, or those containing metal centers [8].

- Incorrect Symmetry: Imposing an incorrectly high symmetry on the molecular structure can sometimes lead to a zero HOMO-LUMO gap, making convergence impossible [5].

2. When should I adjust the mixing scheme and what are my options? You should consider adjusting the mixing scheme when you observe slow convergence, oscillation of the SCF energy, or outright divergence. Mixing strategies extrapolate a better input for the next SCF iteration to accelerate convergence. The main options are:

- Linear Mixing: A simple approach controlled by a single damping factor. It is robust but can be slow for difficult systems [1].

- Pulay (DIIS) Mixing: This is the default in many codes. It uses information from previous iterations to build an optimized extrapolation, which is more efficient than linear mixing for most systems [8] [11] [1].

- Broyden Mixing: A quasi-Newton scheme that updates the mixing using approximate Jacobians. It can sometimes outperform Pulay mixing, especially for metallic or magnetic systems [1].

3. What does the 'damping' parameter do and how do I choose a value? Damping is a technique used to stabilize the SCF cycle. It works by mixing a fraction of the previous iteration's input with the new output to create the input for the next step. This prevents large, unstable jumps in the density or potential [8] [11]. A higher damping factor (closer to 1.0) makes the calculation more stable but can slow down convergence; a lower factor (closer to 0.1) can speed up convergence but risks instability or divergence [1]. The optimal value is system-dependent.

4. How can electronic temperature (smearing) help with convergence? For systems with a small or zero HOMO-LUMO gap, such as metals or near-degenerate systems, fractional occupancy (smearing) is a key tool. It works by assigning fractional occupations to orbitals around the Fermi level according to a temperature-dependent function (e.g., Fermi-Dirac). This artificially increases the HOMO-LUMO gap, dampening "charge-sloshing" instabilities and smoothing the energy landscape, which often allows the SCF procedure to converge [8] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Systematic Workflow

Follow this decision tree to diagnose and fix common SCF convergence problems.

Quantitative Parameter Tables

Table 1: SCF Mixing Algorithm Comparison

| Mixing Method | Typical Mixer.Weight |

Mixer.History |

Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear [1] | 0.1 - 0.3 | N/A | Simple, robust fallback | Inefficient for difficult systems; low weight for stability, high for speed. |

| Pulay (DIIS) [1] [11] | 0.1 - 0.9 | 2 - 8 | Most molecular systems, gapped insulators | Default in many codes. Efficient but can diverge if initial guess is poor. |

| Broyden [1] | 0.1 - 0.9 | 4 - 10 | Metallic systems, magnetic systems | Similar performance to Pulay; can be more robust for specific cases. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Parameters and Values

| Symptom | Primary Tuning Parameter | Typical Value Range | Supporting Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscillating Energy [5] | SCF.Damp / Damping Factor |

0.2 - 0.5 | Use Level_Shift to increase virtual-orbital energy gap [8]. |

| Charge Sloshing (Metals) [22] [1] | SCF.Mixer.Method / Smearing |

Broyden / Fermi-Dirac (100-500 K) | Use Kerker preconditioner for long-range divergence [22]. |

| Slow Convergence [1] | SCF.Mixer.History |

4 - 10 | Increase from default (often 2) to use more past information. |

| Small-Gap Oscillations [5] [8] | Smearing / Fractional Occupancy |

Fermi-Dirac, Methfessel-Paxton | Artificially occupies virtual orbitals to stabilize convergence. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential SCF Convergence Reagents

This table lists the key computational "reagents" and their functions for resolving SCF convergence issues.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in SCF Convergence | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS/Pulay Accelerator [11] [8] | Extrapolates a better input for the next SCF cycle. | Uses a linear combination of Fock matrices from previous iterations to minimize the commutator error, dramatically speeding up convergence. |

| Damping Factor [8] [11] | Stabilizes iterative updates. | Blends the new output density (or potential) with the old input, preventing large, destabilizing steps. |

| Level Shifter [8] | Increases HOMO-LUMO gap. | Artificially raises the energy of virtual (unoccupied) orbitals to prevent oscillatory occupation of near-degenerate orbitals. |

| Electronic Smearing [8] [5] | Treats fractional orbital occupation. | Smears orbital occupations near the Fermi level using an electronic temperature, crucial for converging metallic and small-gap systems. |

| Preconditioner [22] | Rescales long-wavelength updates. | Counteracts the "charge-sloshing" instability in metals by damping long-range density oscillations in the SCF update. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why does my SCF calculation fail to converge, and how can I fix it?

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures are common in ab initio methods research. The table below outlines symptoms, their physical or numerical causes, and recommended last-resort measures.

| Symptom | Probable Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Last-Resort Algorithmic Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large, oscillating energy changes (10⁻⁴–1 Hartree) with changing orbital occupations [5] | Vanishing HOMO-LUMO Gap: Leads to electrons oscillating between frontier orbitals [5]. | Check orbital energies and occupation numbers in the output file. | 1. Apply a Level Shift: Artificially increase the HOMO-LUMO gap by 0.1–0.5 Hartree.2. Use Fermi Smearing: Smears orbital occupations to break symmetry and prevent oscillation.3. Switch to a Direct Minimizer (e.g., geometric direct minimization [17]). |

| Oscillating energy with stable occupations ("Charge Sloshing") [5] | High System Polarizability: A small error in the potential causes a large density distortion [5]. | Monitor for consistent orbital occupations but oscillating density. | 1. Enable Damping: Use strong damping (mixing parameter < 0.1) on the density matrix.2. Switch Mixing Algorithms: Change from DIIS to a simple, damped linear mixer for stability.3. Use a Better Initial Guess: Start from a superposition of atomic potentials or a converged calculation of a similar system [5]. |

| Wildly oscillating or unrealistically low energy | Near-Linear Basis Set Dependence: Basis functions are too similar, causing numerical instability [5]. | Check for basis set warnings and condition number of the overlap matrix (S) [17]. | 1. Remove Linear Dependencies: Use a built-in procedure to purge redundant basis functions.2. Employ a Less-Diffuse Basis Set: Reduces overlap between functions on different atoms. |

| Failure to converge despite standard fixes | Poor Initial Guess & Pathological Systems: The starting density is too far from the solution [5]. | Verify the initial guess (e.g., core Hamiltonian vs. extended Hückel). | 1. Fallback to Robust Algorithms: Use the Optimal Damping Algorithm (ODA) or Direct Minimization (DM). These methods guarantee convergence but are slower than DIIS [17].2. Loosen Convergence Criterion (ModestCriterion) as an interim measure to obtain a qualitatively correct solution. |

How do I implement a fallback strategy when standard solvers fail?

A robust fallback workflow ensures you obtain a result, even if not fully converged to the default threshold.

SCF Fallback Strategy

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Fallback Strategy

- Initial Failure: The standard DIIS algorithm fails to converge after the maximum number of cycles (e.g., 100).

- First Fallback (Robust Solver): Switch to a guaranteed-convergence algorithm like the Optimal Damping Algorithm (ODA) or a Direct Minimization method. These avoid the oscillations that plague DIIS but require more computational time [17].

- Second Fallback (

ModestCriterion): If the robust solver is unavailable or too slow, loosen the convergence threshold. For example, change the energy convergence criterion from1.0e-8to1.0e-5. ThisModestCriterioncan provide a qualitatively correct density for subsequent analysis (like a geometry optimization) where a tighter convergence can be re-attempted [5]. - Final Check: Use the resulting wavefunction or density, even if loosely converged, to diagnose the problem or as a starting point for a new calculation with a modified setup.

FAQs

What are the physical reasons an SCF calculation won't converge?

The primary physical reasons are related to the electronic structure of the system itself [5]:

- Small or Zero HOMO-LUMO Gap: Systems with nearly degenerate frontier orbitals (e.g., transition metal complexes, diradicals, stretched bonds) are inherently difficult. The SCF procedure struggles to decide which orbitals to occupy, leading to oscillation [5].

- High Polarizability ("Charge Sloshing"): In metallic systems or large conjugated molecules, the electron density is easily displaced. Small errors in the iterative potential can lead to large, oscillating changes in the computed density [5].

- Incorrect Spin or Charge State: Providing an incorrect initial guess for the multiplicity or total charge can place the system in an unstable region of the electronic potential energy surface, preventing convergence.

When should I loosen the convergence criterion (ModestCriterion) as a last resort?

Loosening the convergence criterion is a pragmatic last resort when:

- All Other Measures Fail: After trying level shifts, damping, robust solvers, and improving the initial guess.

- A Qualitative Result is Sufficient: The goal is to generate a reasonable starting orbital for a geometry optimization or a molecular dynamics simulation, where the wavefunction will be re-optimized in the next step.

- System Diagnostics: A loosely converged result can help you diagnose the issue (e.g., by examining the resulting orbitals) before investing more computational resources.

How do level shift and damping algorithms work as last-resort measures?

These algorithms stabilize the SCF cycle by modifying the Fock matrix or density mixing.

Level Shift and Damping

Mechanisms:

- Level Shift: Artificially increases the orbital energies of the virtual (unoccupied) orbitals. This widens the HOMO-LUMO gap, preventing electrons from oscillating between them and breaking the cyclic instability [5].

- Damping: Mixes the new density matrix from the current iteration with the density from the previous iteration. A high damping factor (e.g., α = 0.9) heavily relies on the old density, preventing large, unstable changes from one cycle to the next [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Level Shift Algorithm | A numerical stabilizer that artificially increases the energy of virtual orbitals to prevent occupation oscillation in systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps [5]. |

| Damping / Linear Mixing | A simple mixing scheme of old and new density matrices to dampen large oscillations in the SCF cycle, trading stability for slower convergence [5]. |

| Direct Minimization (DM) | An alternative to the standard SCF procedure that minimizes the total energy directly with respect to the orbital coefficients. It is more robust and guaranteed to converge but is often computationally slower than DIIS [17]. |

| Optimal Damping Algorithm (ODA) | An advanced form of damping that finds the optimal mixing parameter at each iteration to minimize the energy. It guarantees convergence but is more complex to implement [17]. |

ModestCriterion |

A pragmatic, loosened convergence threshold (e.g., 1e-5 instead of 1e-8) used to obtain a qualitatively correct result when tight convergence is impossible, allowing the research to proceed [5]. |

Validating SCF Results and Comparing Methodological Approaches

A technical support guide for researchers validating self-consistent field calculations in computational chemistry and materials science.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What does it mean if my calculation completes without error, but the output states "SCF not fully converged!"?

This indicates a state of near convergence. The calculation was stopped after reaching the maximum number of cycles, but one or more convergence criteria were not fully met. The results, particularly the final single point energy, should be treated with caution as they may be unreliable [13]. For single-point calculations, ORCA and other packages will typically not proceed to subsequent property calculations by default when this occurs [13].

Q2: How can I verify that my converged SCF solution is a true ground state and not a saddle point?

You should perform a stability analysis [8]. A wave function can be stable or unstable with respect to two types of perturbations: internal (orbital rotations within the current ansatz) and external (breaking constraints like spin symmetry) [8]. PySCF and other codes provide tools for this. If an instability is found, you should follow the unstable mode to reconverge the SCF, often leading to a lower-energy, stable solution [8].

Q3: My finite-bias NEGF calculation won't converge, but the zero-bias case was fine. What should I do?

Finite-bias calculations are inherently more challenging. The best practice is to restart from a converged calculation at a lower, or zero, bias [9]. If a 0.4 V calculation fails, try achieving convergence in smaller incremental steps (e.g., 0.1 V, then 0.2 V, etc.) [9]. All the standard troubleshooting for zero-bias cases, such as ensuring your central region is long enough for proper screening, also applies [9].

Q4: Why do my results differ when I perform a calculation on the same structure from a VC-RELAX and a standalone SCF?

First, verify the structures are identical by comparing their Ewald energies [23]. The plane-wave basis set in variable-cell calculations is determined by the cutoff and the initial cell geometry. Running the final geometry with the same cutoff but a different basis set can lead to slight numerical differences [23]. Newer versions of codes like Quantum ESPRESSO often perform a final SCF step with the basis for the final geometry to check for this [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Verifying SCF Convergence and Solution Quality

A converged SCF calculation must satisfy multiple quantitative criteria. The following table summarizes standard convergence metrics and their interpretations.

Table: Standard SCF Convergence Criteria and Troubleshooting Actions

| Metric | Description | Converged Threshold (Example) | Action if Not Met |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Change (ΔE) | Change in total energy between cycles [4]. | < 1x10⁻⁸ Eh (TightSCF) [4] | Increase MaxIter; Check integral threshold [11] [4]. |

| Density Change (RMS) | Root-mean-square change in density matrix [2] [4]. | < 5x10⁻⁹ (TightSCF) [4] | Tighten convergence criteria; Switch to a more robust algorithm (GDM, TRAH) [11] [13] [4]. |

| Density Change (Max) | Maximum change in density matrix [4]. | < 1x10⁻⁷ (TightSCF) [4] | Tighten convergence criteria; Switch algorithm [11] [4]. |

| Orbital Gradient | Gradient of energy with respect to orbital rotations [4]. | < 1x10⁻⁵ (TightSCF) [4] | Activate or configure second-order convergers (SOSCF, TRAH) [13] [8]. |

| DIIS Error | Norm of the commutator [F, P S] [11] [8]. |

< 5x10⁻⁷ (TightSCF) [4] | Increase DIIS subspace size; Use damping/level shift [2] [8] [14]. |

Verification Protocol:

- Check Multiple Criteria: Do not rely on a single metric. Confirm that energy, density, and orbital gradients have all met their thresholds [4].

- Perform Stability Analysis: After convergence, run a stability check to ensure the solution is a true minimum and not a saddle point. If unstable, follow the unstable mode to reconverge the SCF [8].

- Verify Physical Properties: Calculate dipole moments, orbital populations (e.g., Löwdin charges), and spin densities. Compare these to expected values or literature to catch physically unreasonable solutions [23] [8].

Achieving Robust SCF Convergence

When facing convergence failures, follow this systematic workflow to identify and resolve the issue.

Step 1: Initial Checks

- Geometry: Ensure atomic coordinates and bond lengths are realistic and units are correct [14].

- Spin State: Verify the calculated spin multiplicity matches the expected electronic state of your system [14].

- Initial Guess: Improve the starting guess. Use a superposition of atomic densities (

minao/atom), read orbitals from a previous calculation (chkfile), or use a guess from a simpler method or oxidation state [13] [8].

Step 2: Algorithm and Parameter Tuning

- Switch Algorithms: If DIIS fails, try more robust alternatives like the geometric direct minimization (GDM) [11], the Trust Radius Augmented Hessian (TRAH) method in ORCA [13] [4], or the ARH method in ADF [14].

- Use Damping and Level Shifting: Apply damping (mixing) with a low value (e.g., 0.015) in early cycles to stabilize wild oscillations [8] [14]. Level shifting artificially increases the HOMO-LUMO gap, which can prevent variational collapse in systems with small gaps [8] [14].

- Adjust DIIS Parameters: For difficult cases, increase the number of DIIS expansion vectors (e.g., from 10 to 25) and delay the start of DIIS to allow for initial equilibration [13] [14].

Step 3: Advanced Techniques for Pathological Cases

- Fractional Occupations & Smearing: Use electronic temperature or smearing to assign fractional occupations to orbitals near the Fermi level. This is particularly helpful for metallic systems or those with many near-degenerate states [2] [23] [8].

- Increase Computational Parameters: For systems suspected of having numerical noise, increase the density mesh cut-off [9], use a larger integration grid [13], or increase the number of k-points in periodic calculations [23] [9].

- System-Specific Settings: For open-shell transition metal complexes, use dedicated keywords like

SlowConvand increaseDIISMaxEqto 15-40. Settingdirectresetfreqto 1 (rebuilding the Fock matrix every cycle) can eliminate numerical noise at high computational cost [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for SCF Calculations

| Item | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| DIIS (Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) | Extrapolates a new Fock matrix using a linear combination of previous matrices to accelerate convergence [11] [8]. | Default algorithm in many codes for well-behaved systems [11]. |

| GDM (Geometric Direct Minimization) | A robust minimizer that accounts for the curved geometry of orbital rotation space; excellent fallback when DIIS fails [11]. | Set SCF_ALGORITHM=GDM in Q-Chem [11]. |

| TRAH (Trust Region Augmented Hessian) | A robust second-order converger that automatically activates in ORCA if the default procedure struggles [13] [4]. | Default safety net in ORCA; can be manually disabled with !NoTRAH [13]. |

| Level Shifting | Stabilizes convergence by artificially increasing the energy of virtual orbitals, widening the HOMO-LUMO gap [8] [14]. | mf.level_shift = 0.3 in PySCF for systems with small gaps [8]. |

| Electron Smearing | Aids convergence in metallic/small-gap systems by applying a finite electronic temperature to fractional occupy orbitals [2] [23] [8]. | Convergence ElectronicTemperature 0.001 in BAND (value in Hartree) [2]. |

| Stability Analysis | Checks if a converged wavefunction is a true minimum or an unstable saddle point [8]. | Run after SCF convergence to validate the solution's stability [8]. |

FAQs on SCF Convergence in Magnetic Systems

Q1: Why do my self-consistent field (SCF) calculations frequently fail to converge when modeling magnetic systems, particularly those containing transition metals?

Magnetic systems, especially open-shell transition metal complexes, are notoriously challenging for SCF convergence due to the presence of unpaired electrons and complex potential energy surfaces [13]. The primary reasons for failure include:

- Numerical Instability: The default convergence algorithms (e.g., DIIS) can oscillate wildly when dealing with the near-degenerate states common in magnetic materials [13] [24].

- Insufficient Initial Guess: The starting electron density or wavefunction is too far from the ground state, particularly for complex magnetic configurations [24].

- Inaccurate Integration: For Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations, an insufficiently precise numerical integration grid (e.g., for exchange-correlation or density fitting) can introduce noise that prevents convergence [25] [13].

- Insufficient Basis Set or Bands: Using a basis set that is too small or having too few electronic bands (

NBANDS) can lead to an incomplete description of the electron states, hindering convergence. This is critical for systems with f-orbitals or meta-GGA functionals [24].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between a self-consistent and a single-shot (non-self-consistent) calculation?

The difference lies in whether the electronic structure is iterated to achieve a consistent solution.

- A Self-Consistent calculation is an iterative process. It starts with an initial guess for the electron density or wavefunction, constructs the Hamiltonian, solves for new orbitals, and generates a new density. This cycle repeats until the input and output densities/wavefunctions are consistent (converged) according to a predefined threshold [26]. This is necessary for obtaining a correct, variational total energy and electron density for a given geometry [26].

- A Single-Shot (Non-Self-Consistent) calculation is a one-step evaluation. It takes a pre-converged charge density (or wavefunction) from a previous SCF calculation and uses it to compute properties like the band structure or energy for a different configuration (e.g., a new magnetic moment orientation) without re-iterating to self-consistency [26]. This is faster but yields non-variational energies and is only reliable if the fixed density is a good approximation for the new configuration [26].

Q3: When calculating magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE), is it acceptable to use a non-self-consistent approach?

Yes, a non-self-consistent approach is a standard and efficient method for calculating MAE, based on the force theorem (also known as the magnetic force theorem) [26]. The workflow is as follows:

- Perform a fully self-consistent calculation for an initial magnetic moment orientation (e.g., along the z-axis). This yields a converged charge density.

- Without updating this charge density, perform a single-shot calculation for a different magnetic orientation (e.g., in the x-y plane).

- The MAE is approximated by the difference in the band energies (or one-electron energies) from the two non-self-consistent calculations [26].

This method is valid because the MAE is a small energy difference largely determined by the changes in occupied orbital energies at the Fermi level, while the total charge density remains relatively unchanged by the spin-orbit coupling responsible for MAE.

Troubleshooting Guide: SCF Convergence for Magnetic Materials

This guide provides specific protocols to overcome SCF convergence failures.

Protocol 1: Systematic SCF Parameter Adjustment

Begin with these adjustments to stabilize the SCF cycle, applicable across various computational codes (VASP, ORCA, BAND).

Table 1: Key SCF Parameters for Troubleshooting Magnetic Systems

| Parameter / Keyword | Typical Default | Troubleshooting Adjustment | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing Parameter | Varies (~0.05) | Decrease (e.g., to 0.02) | Reduces step size between cycles, damping oscillations [25]. |

| DIIS Dimension | 5-10 | Increase (e.g., to 15-40) | Uses more history for extrapolation, improving stability in difficult cases [13]. |

| Algorithm (ALGO) | DIIS/Normal | Switch to All (Conjugate Gradient) or DAMPED |

More robust, second-order algorithms can converge where DIIS fails [24]. |

| Fock Matrix Rebuild | ~15 iterations | Increase frequency (e.g., directresetfreq 1) |

Reduces numerical noise from integral approximations, aiding convergence [13]. |

| Level Shifting | Off | Apply a small shift (e.g., 0.1 eV) | Shifts unoccupied states higher, improving stability by preventing charge sloshing [13]. |

| Electronic Smearing | ISMEAR = 0 | Use ISMEAR = -1 (Fermi) or 1 (Methfessel-Paxton) |

Helps converge metallic systems with states at the Fermi level [24]. |

Protocol 2: Advanced Multi-Step Workflow for Pathological Cases (e.g., VASP)

For systems that remain unstable, such as magnetic calculations with LDA+U, a segmented approach is recommended [24].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Step 1: Generate a Stable Initial Guess

- Use a non-spin-polarized or coarse calculation to generate a preliminary charge density (

ICHARG=12in VASP). - Run with a standard algorithm (

ALGO=Normal) and without theLDA+Ucorrection to find a stable starting point [24].

- Use a non-spin-polarized or coarse calculation to generate a preliminary charge density (

Step 2: Converge Spin-Polarized State

- Restart from the

WAVECARof Step 1. - Switch to a more stable algorithm (

ALGO=Allin VASP, conjugate gradient). - Crucially, reduce the

TIMEparameter (e.g., to 0.05) to lower the energy change per step, preventing divergence [24]. - Keep

LDA+Udisabled.

- Restart from the

Step 3: Introduce LDA+U

- Restart from the

WAVECARof Step 2. - Now, add the

LDA+Uparameters to the input. - Maintain the stable algorithm and reduced

TIMEsetting from Step 2. - Complete the final SCF cycle to convergence [24].

- Restart from the

Protocol 3: Alternative Guess and Convergence Strategies

- Change the Initial Guess: If the default guess (e.g.,