Unraveling Complexity: A Practical Guide to Handling Factor Interactions in Chemical Screening Experiments

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing factor interactions in chemical screening experiments.

Unraveling Complexity: A Practical Guide to Handling Factor Interactions in Chemical Screening Experiments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing factor interactions in chemical screening experiments. It covers foundational concepts of experimental designs like Plackett-Burman and fractional factorial approaches, explores advanced computational methods for interaction detection, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and presents validation frameworks. By integrating both traditional statistical designs and modern computational approaches, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of chemical screening in biomedical research, ultimately leading to more accurate drug discovery outcomes.

Understanding Factor Interactions: Why Screening Designs Aren't as Simple as They Seem

The Critical Role of Factor Interactions in Chemical Screening

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unreliable or Inconsistent Screening Results

Problem: Your screening experiment identifies certain factors as "significant," but these results are not reproducible in subsequent validation experiments. The identified optimal conditions do not yield the expected performance.

Explanation: This is a classic symptom of confounded factor interactions. In screening designs, especially highly fractional ones, the effect of a single factor can be entangled (confounded) with the interaction effect of two or more other factors. If these interactions are strong, you may mistakenly attribute the effect to the wrong factor [1].

Solution:

- Analyze the Design Resolution: Before running the experiment, check the resolution of your screening design. A design of Resolution III confounds main effects with two-factor interactions, which is the primary cause of this problem. If you suspect significant interactions, use a design of Resolution IV or higher, where main effects are confounded with three-factor interactions (which are often negligible) and not with two-factor interactions [1].

- Apply the Steepest Ascent/Descent Method: Use the initial screening results to guide a follow-up investigation along the path of steepest ascent (for maximizing a response) or descent (for minimizing a response). This allows you to quickly move to a more promising region of the factor space and verify the initial findings [2].

- Perform a Fold-Over Design: If you have a Resolution III design and encounter this issue, you can "fold over" the entire design by reversing the signs of all factors. Combining the original and the new experimental data will break the confounding between main effects and two-factor interactions, allowing you to de-alias them and identify the true active factors [1].

Issue 2: Missed Critical Interactions Between Factors

Problem: Your process or product performs well at the lab scale but fails during scale-up or technology transfer. A critical interaction between factors was not identified during the initial screening phase.

Explanation: Some screening designs, like Plackett-Burman designs, are not capable of estimating interaction effects at all. They are constructed to only evaluate main effects [2]. If you use such a design in a system where interactions are present, they will go completely undetected and can cause major failures later.

Solution:

- Select an Appropriate Design: If prior knowledge or mechanistic understanding suggests interactions are likely, avoid Plackett-Burman designs. Opt for a Fractional Factorial Design with sufficient resolution (IV or V) that allows for the estimation of at least some two-factor interactions [2] [1].

- Include Potential Interactions in Data Analysis: Even if your design confounds certain interactions, use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab) to perform a full analysis of variance (ANOVA). Examine the interaction plots and Pareto charts of effects. Large, statistically significant interaction effects will often be evident, even if they are confounded with other effects, signaling the need for a more detailed follow-up experiment [2].

Issue 3: High Variation in Response Measurements Obscures Factor Effects

Problem: The "noise" in your response data is so high that it becomes difficult to distinguish the real "signal" (the effect of a factor). No factors appear statistically significant.

Explanation: All experimental data has inherent random variation. If this variation is too large, the effects of factors, which might be important, will not be statistically significant. This can be due to measurement error, process instability, or uncontrolled environmental factors [2].

Solution:

- Implement Replication: Repeating experimental runs under identical conditions is the most direct way to quantify and account for random error. Replication provides a more reliable estimate of the pure error, which allows for a more sensitive statistical test to detect significant factor effects [2].

- Increase Effect Size: If possible, widen the range between the low and high levels of your factors. A larger level spread will produce a larger factor effect, making it easier to detect over the background noise. Ensure the chosen ranges are practical and do not lead to process failure or unsafe conditions [2].

- Control Extraneous Variables: Review your experimental procedure to identify and control sources of variation. This could include calibrating equipment more frequently, using reagents from the same batch, or conducting the experiment in a controlled environment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a Screening Design and an Optimization Design?

Answer: The goals of these designs are distinct. A Screening Design is a preliminary tool used to efficiently sift through a large number of potential factors to identify the few vital ones that have a significant impact on the response. Its primary goal is factor selection. In contrast, an Optimization Design (e.g., a Response Surface Methodology design) is used after the key factors are known. It aims to model the response in detail to find the precise factor settings that achieve an optimal outcome, often exploring curvature in the response surface [2].

FAQ 2: When should I use a Plackett-Burman design over a Fractional Factorial design?

Answer: Use a Plackett-Burman design when you need to screen a very large number of factors with an extremely economical number of runs and you have a strong prior belief that interaction effects are negligible. Use a Fractional Factorial design when you want to screen a moderate number of factors and you need the ability to estimate at least some two-factor interactions or you want to avoid confounding main effects with two-factor interactions by using a higher-resolution design [2] [1].

FAQ 3: What does "Design Resolution" mean, and why is it critical for interpreting my results?

Answer: Design Resolution (labeled with Roman numerals III, IV, V, etc.) is a key property that tells you the pattern of confounding in your fractional factorial design.

- Resolution III: Main effects are confounded with two-factor interactions. Use with caution.

- Resolution IV: Main effects are confounded with three-factor interactions, and two-factor interactions are confounded with each other. This is better for screening.

- Resolution V: Main effects are confounded with four-factor interactions, and two-factor interactions are confounded with three-factor interactions. This provides very clear information on main effects and some two-factor interactions [1]. Choosing a design with insufficient resolution is a major source of error in interpreting screening experiments.

FAQ 4: How can I identify and handle a significant interaction effect from my screening data?

Answer: A significant interaction between Factor A and Factor B means that the effect of Factor A depends on the level of Factor B. You can identify it in two ways:

- Statistical Output: Look at the ANOVA table from your statistical software. A low p-value for the interaction term (e.g., A*B) indicates statistical significance.

- Interaction Plot: Graphically, a significant interaction is indicated when the lines on an interaction plot are not parallel. To handle it, you must choose the level of one factor based on the level of the other. You cannot set them independently [2] [1].

FAQ 5: Our drug discovery pipeline involves many factors. How do intrinsic/extrinsic patient factors interact with experimental parameters?

Answer: In drug development, intrinsic factors (e.g., genetics, age, organ function) and extrinsic factors (e.g., diet, concomitant medications) can have profound interactions with a drug's formulation and dosage parameters [3]. For example, a drug's absorption (an experimental response) might be influenced by an interaction between the drug's formulation (an experimental factor) and the patient's gastric pH (an intrinsic factor) [4]. Furthermore, a concomitant medication (extrinsic factor) can inhibit a metabolic enzyme, interacting with the drug's metabolic pathway and drastically altering its exposure [4] [3]. A robust screening strategy should consider these biological factors as critical components to be included in the experimental design.

Experimental Protocols for Key Screening Designs

Protocol 1: Fractional Factorial Screening Design

Objective: To identify the critical factors affecting yield and purity in a chemical synthesis process.

Methodology:

- Define the Problem: Clearly state the goal: "Identify which of 5 factors (A: Temperature, B: Catalyst Concentration, C: Reaction Time, D: Solvent Ratio, E: Mixing Speed) most significantly impact reaction yield."

- Select Factors and Levels: Choose a low (-1) and high (+1) level for each factor.

- Choose the Design: A half-fraction for 5 factors is a 2^(5-1) design, requiring 16 experiments. Use a generator (e.g., E = ABCD) to create a Resolution V design, which ensures no main effects or two-factor interactions are confounded with each other [1].

- Conduct the Experiment: Randomize the run order of the 16 experiments to avoid bias. Perform the synthesis and measure the yield for each run.

- Analyze the Data:

- Use statistical software to perform an ANOVA.

- Construct a Pareto Chart of the standardized effects to visually identify which factors exceed the statistical significance threshold.

- Examine Normal Probability Plots of the effects; significant effects will deviate from the straight line formed by null effects.

- Interpret the Results: Identify the factors with large, significant main effects. Also, check for any significant two-factor interactions. The results will guide further optimization studies on the vital few factors.

Protocol 2: Plackett-Burman Screening Design

Objective: To rapidly screen 11 potential factors in a cell-based assay to identify those affecting target protein expression.

Methodology:

- Define the Problem: "Screen 11 cell culture conditions (e.g., media components, growth factors, CO₂ levels) to find those that influence protein expression levels."

- Select Factors and Levels: Define two levels for each of the 11 factors.

- Choose the Design: A Plackett-Burman design for 11 factors can be conducted in only 12 experimental runs, making it highly efficient [2].

- Conduct the Experiment: Set up the 12 different cell culture conditions as per the design matrix in a randomized order. Harvest and measure protein expression.

- Analyze the Data:

- Since Plackett-Burman designs do not estimate interactions, the analysis focuses solely on main effects.

- Perform a multiple linear regression analysis on the data.

- Rank the factors based on the magnitude of their main effects and statistical significance (p-values).

- Interpret the Results: Select the top 3-4 factors with the largest significant main effects for further, more detailed investigation in a subsequent optimization study.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Screening Designs

| Design Type | Number of Factors | Minimum Number of Runs | Can Estimate Interactions? | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | k | 2^k | Yes, all | Comprehensive data on all effects | Number of runs grows exponentially | Small number of factors (typically <5) for full characterization [1] |

| Fractional Factorial (Resolution III) | k | 2^(k-1) | No | High efficiency for many factors | Main effects confounded with 2-factor interactions | Initial screening of many factors where interactions are assumed negligible [2] [1] |

| Fractional Factorial (Resolution IV) | k | 2^(k-1) or more | Some | Main effects not confounded with 2-factor interactions | 2-factor interactions confounded with each other | Screening when some interaction effects are suspected [1] |

| Plackett-Burman | N | N+1 | No | Extreme efficiency for very large factor sets | Cannot estimate any interactions | Very early-stage screening of a large number of factors [2] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cellular Target Engagement Screening

| Item | Function/Explanation | Application in Screening |

|---|---|---|

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | A method to directly confirm drug-target engagement in intact cells or tissues by measuring thermal stabilization of the target protein [5]. | Validates that a screened compound actually binds to its intended protein target in a physiologically relevant environment, de-risking the screening hit [5]. |

| P-glycoprotein (P-gp) Inhibitors | Compounds that inhibit the P-gp efflux pump protein. P-gp can significantly alter the absorption and distribution of drugs [4]. | Used in screening assays to understand if a compound's permeability is limited by active efflux, a key factor in bioavailability [4]. |

| CYP450 Isozyme Assays | Assays to measure the interaction of compounds with Cytochrome P450 enzymes, which are critical for drug metabolism [4] [3]. | Screens for potential drug-drug interactions and identifies compounds with high metabolic clearance via a single pathway, a risk factor for variability [3]. |

| Defined Media Formulations | Cell culture media with precisely controlled concentrations of components, eliminating variability from serum [5]. | Ensures consistency and reproducibility in cell-based screening assays by controlling extrinsic nutritional factors. |

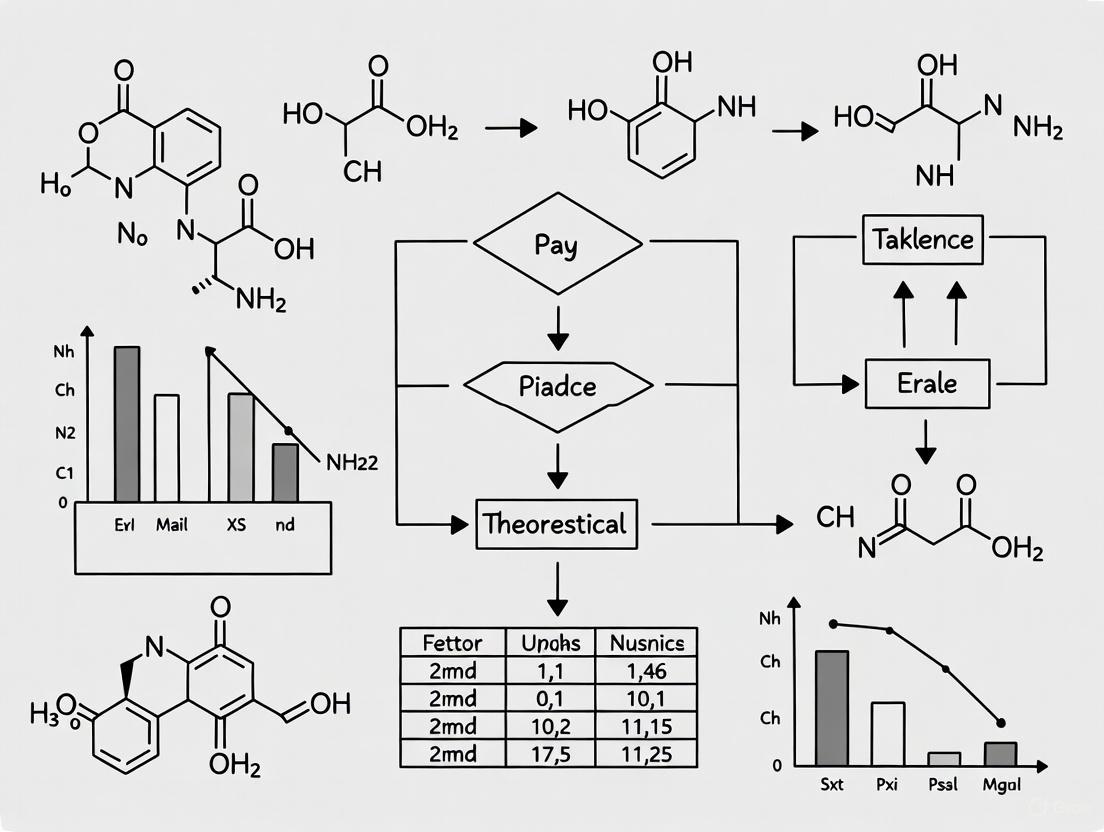

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Screening Design Selection Logic

Factor Interaction Analysis Workflow

Plackett-Burman (PB) Designs are a class of highly efficient, two-level screening designs used in the Design of Experiments (DoE) [6] [7]. Developed by statisticians Robin Plackett and J.P. Burman in 1946, their primary purpose is to screen a large number of factors to identify the "vital few" that have significant main effects on a response variable, while assuming that interactions among factors are negligible [8] [9]. This makes them invaluable in the early stages of research, such as in pharmaceutical development or process optimization, where many potential factors exist but resources for experimentation are limited [10] [11].

The core strength of PB designs is their economic use of experimental runs. They allow the study of up to N-1 factors in only N experimental runs, where N is a multiple of 4 (e.g., 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24) [6] [12]. This economy, however, comes with a critical hidden complexity: PB designs are Resolution III designs [6] [8]. This means that while main effects are not confounded with each other, they are partially confounded with two-factor interactions [8] [13]. If significant interactions are present, they can distort the estimate of main effects, leading to incorrect conclusions about which factors are important [8] [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Navigating Common Issues

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when using PB designs. The following guide addresses these common pitfalls and provides solutions.

| Common Issue | Symptoms | Underlying Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Misleading Significant Factors | A factor shows as significant, but its effect disappears or reverses in follow-up experiments. | Confounding: The main effect is aliased with one or more two-factor interactions [8] [1]. | Assume interactions are negligible; use a foldover design to de-alias specific effects [6] [13]. |

| High Prediction Error | The model fits the experimental data poorly and fails to predict new outcomes accurately. | Omitted Variable Bias or Curvature. The model may miss an important active factor or the system may have a non-linear relationship [14]. | Add center points to detect curvature; conduct a follow-up optimization design (e.g., Response Surface Methodology) [14]. |

| Inability to Find Optimal Settings | The screening identifies active factors, but the best combination of settings remains unknown. | Screening Limitation. PB designs identify active factors but are not intended for finding optimum settings [7] [14]. | Use the PB results to run a full factorial or optimization design (e.g., Central Composite Design) with the 3-5 vital factors found [8] [14]. |

| Unclear or "Noisy" Effects | The analysis does not show clear, statistically significant effects; the normal probability plot is messy. | High Random Error or Too Many Inactive Factors. The experimental error may be large, or the significance level may be too strict [8]. | Use a higher alpha level (e.g., 0.10) for screening [8]; increase replication to better estimate error. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I use a Plackett-Burman design instead of a fractional factorial design?

The choice depends on your goals, the number of factors, and assumptions about interactions. The table below outlines the key differences.

| Feature | Plackett-Burman Design | Fractional Factorial Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Screening a large number of factors to find the vital few [11]. | Screening, but with better ability to deal with some interactions. |

| Run Numbers | Multiples of 4 (e.g., 12, 16, 20, 24) [8] [12]. | Powers of 2 (e.g., 8, 16, 32, 64) [8] [13]. |

| Confounding | Main effects are partially confounded with many two-factor interactions [8]. | Main effects are completely confounded with specific higher-order interactions [1]. |

| Best Use Case | Many factors (e.g., >5), limited runs, assumption of negligible interactions [13]. | A smaller number of factors where some interaction information is needed, and run numbers fit a power of two [13]. |

2. How do I handle the confounding between main effects and two-factor interactions?

First, you must rely on process knowledge to assume that two-factor interactions are weak compared to main effects [8] [9]. If this assumption is questionable, you can use a foldover design [6]. This involves running a second set of experiments where the signs of all factors are reversed, which combines the original and foldover designs into a higher-resolution design that can separate main effects from two-factor interactions [6] [13].

3. What is the "projectivity" of a Plackett-Burman design and why is it useful?

Projectivity is a valuable property of screening designs. A design with projectivity p means that for any p factors in the design, the experimental runs contain a full factorial in those factors [13]. For example, if a PB design has projectivity 3 and you later find that only three factors are active, you can re-analyze your data as if you had run a full factorial design for those three factors without needing additional experiments [13].

4. My factors have more than two levels (e.g., three different types of catalyst). Can I use a Plackett-Burman design?

Standard PB designs are for two-level factors only [7] [9]. While multi-level PB designs exist, they are less common [9]. For categorical factors with more than two levels, other designs like General Full Factorial or Definitive Screening Designs (DSDs) may be more appropriate [8].

Experimental Protocol: Executing a Plackett-Burman Screening Design

The following workflow outlines the key steps for planning, executing, and analyzing a Plackett-Burman experiment.

1. Define Objective and Factors

- Objective: Clearly state the goal of identifying which factors significantly impact a specific response (e.g., yield, purity, hardness) [14].

- Factor Selection: Brainstorm and select all potential factors (k) [11]. For each, define a practical high (+1) and low (-1) level that spans a range of interest [8].

2. Select Design Size

- Determine the number of experimental runs (N) based on the number of factors (k). The rule is N ≥ k + 1, and N must be a multiple of 4 [6] [12]. Standard sizes are shown below.

| Number of Factors (k) | Minimum PB Runs (N) | Common Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| 4 - 7 | 8 | 8-run Fractional Factorial |

| 8 - 11 | 12 | 16-run Fractional Factorial [8] |

| 12 - 15 | 16 | 16-run Fractional Factorial |

| 16 - 19 | 20 | 32-run Fractional Factorial [12] |

| 20 - 23 | 24 | 32-run Fractional Factorial [12] |

3. Generate Design Matrix

- Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, R) to generate the design matrix [8]. This matrix specifies the factor levels (+1 or -1) for each experimental run [6].

- Consider Center Points: Adding 3-5 center points (all factors set to 0) is highly recommended to check for curvature in the response, which a two-level design cannot model [14].

4. Randomize and Execute Runs

- Randomize the run order provided by the software to protect against the effects of lurking variables and systematic noise [6].

- Execute the experiments and carefully measure the response for each run.

5. Analyze Main Effects

- Calculate Main Effects: For each factor, the main effect is the difference between the average response at its high level and the average response at its low level [6] [14].

- Identify Significant Effects:

- Normal Probability Plot: Plot the calculated main effects. Significant effects will deviate from the straight line formed by the negligible effects [6] [14].

- Pareto Chart or Hypothesis Tests: Use these to see which effects are statistically significant. In screening, it is common to use a higher significance level (α = 0.10) to avoid missing active factors [8].

6. Plan Follow-up Experiments

- A PB design is a starting point. The identified "vital few" factors (typically 3-5) should be investigated further using more detailed experiments, such as full factorial or Response Surface Methodology (RSM) designs, to model interactions and find optimal settings [8] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The specific reagents will vary by application, but the following table lists common categories used in experiments where PB designs are applied, such as in polymer science or biotechnology [8] [10].

| Category / Item | Function in the Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Components | The fundamental building blocks of a formulation or reaction mixture whose concentrations are often studied as factors. | Resin, Monomer, Plasticizer, Filler in a polymer hardness experiment [8]. |

| Chemical Inducers | Used to precisely control the timing and level of gene expression in metabolic engineering experiments. | Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) [10]. |

| Defined Media Components | Nutrient sources (e.g., carbon, nitrogen) whose concentrations can be optimized as factors in fermentation or cell culture. | Succinate, Glucose [10]. |

| Biological Parts (Cis-regulatory) | Genetic elements that control the strength of gene expression; their selection is a categorical factor in genetic optimization. | Promoters, Ribosome-Binding Sites (RBSs) [10]. |

| Analytical Standards | Essential for calibrating equipment and ensuring the accuracy and precision of response measurements (e.g., yield, concentration). | Not specified in search results, but critical for data quality. |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in effectively implementing fractional factorial designs for chemical screening experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Under what circumstances should I choose a fractional factorial design over a full factorial design?

You should consider a fractional factorial design in the early stages of experimentation, or for screening purposes, when you have a large number of factors to investigate and a full factorial design is too costly, time-consuming, or otherwise infeasible [15] [16]. The primary advantage is efficiency; these designs allow you to screen many factors with a significantly reduced number of experimental runs [17]. For example, studying 8 factors at 2 levels each would require 256 runs for a full factorial, but a fractional factorial can reduce this to 16 or 32 runs [17]. They are ideal when you operate under the sparsity of effects principle, which assumes that only a few factors and low-order interactions will have significant effects [18].

FAQ 2: The term "design resolution" is frequently used. What does it mean for my experiment, and how do I choose?

Design resolution, indicated by Roman numerals (e.g., III, IV, V), is a critical classification that tells you how effects in your design are aliased, or confounded [18] [16]. It measures the design's ability to separate main effects from interactions. The choice involves a direct trade-off between experimental economy and the clarity of the information you obtain.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different design resolutions:

| Resolution | Aliasing Pattern | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution III | Main effects are confounded with 2-factor interactions [18] [16]. | Preliminary screening of a large number of factors when you can assume 2-factor interactions are negligible [16]. |

| Resolution IV | Main effects are not confounded with any 2-factor interactions, but 2-factor interactions are confounded with each other [18] [15]. | Screening when you need clear estimates of main effects and can assume that only some 2-factor interactions are important [16]. |

| Resolution V | Main effects and 2-factor interactions are not confounded with other main effects or 2-factor interactions (though 2-factor interactions may be confounded with 3-factor interactions) [18] [16]. | When you need to estimate both main effects and 2-factor interactions clearly, and your resources allow for more runs [16]. |

FAQ 3: I've run my screening experiment and identified significant effects, but some are aliased. How can I resolve this ambiguity?

This is a common situation. The primary method for de-aliasing significant effects is to conduct a foldover experiment [18] [16]. A foldover involves running a second fraction of the original design where the levels of some or all factors are reversed [16]. This process combines data from both fractions to break the aliasing between certain effects, effectively increasing the resolution of the combined design. For example, folding over a Resolution III design typically results in a combined design of Resolution IV, thereby separating the previously confounded main effects and two-factor interactions [18].

FAQ 4: My fractional factorial design is "saturated," meaning I have no degrees of freedom to estimate error. How can I analyze it?

For saturated designs, you cannot use standard p-values from an ANOVA table. Instead, you must rely on graphical methods and the sparsity of effects principle [15]. The recommended technique is to create a half-normal plot of the estimated effects [15]. In this plot, negligible effects, which are assumed to be random noise, will fall along a straight line. Significant effects will deviate noticeably from this line. You can use these significant effects to build a model, and then use the remaining, non-significant effects to estimate the error variance [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpected or Inconclusive Results After Analysis

- Potential Cause 1: Confounding of Significant Interactions. A significant effect you attributed to a main factor might actually be caused by a confounded two-factor interaction.

- Potential Cause 2: Violation of the Sparsity-of-Effects Principle. Your assumption that higher-order interactions are negligible may be incorrect.

- Solution: If resources allow, augment your design with additional runs (e.g., a foldover or adding center points) to estimate error and de-alias effects [15]. Consider using a higher-resolution design in the next phase of experimentation.

- Potential Cause 3: Presence of Lurking Variables. An uncontrolled background variable is influencing your response.

Problem: Managing Complex Experiments with Multiple Factors

- Potential Cause: The number of factors makes even a fractional factorial too large.

- Solution: For a very high number of factors (e.g., more than 8), consider other screening designs like Plackett-Burman designs (a type of non-regular fractional factorial) or Definitive Screening Designs [19] [17]. These can handle many factors with an even more economical run size, though their alias structure can be more complex [19] [17].

Experimental Protocol: Screening Synthesis Parameters with a 26-2FFD

The following protocol is adapted from a published study on screening process parameters for the synthesis of gold nanoparticles (GNPs) [20].

1. Objective: To identify the critical process parameters (factors) that significantly impact the particle size (PS) and polydispersity index (PDI) of gold nanoparticles.

2. Experimental Design Selection:

- Design Type: 2-level, 6-factor, Fractional Factorial Design (26-2).

- Runs Required: 16 (one-quarter fraction of the full 64-run factorial) [20].

- Resolution: The design is Resolution IV, meaning main effects are not aliased with two-factor interactions, but two-factor interactions are aliased with each other [20] [18].

3. Factors and Levels: The table below details the independent variables (factors) and their assigned high and low levels [20].

| Factor | Name | Low Level (-1) | High Level (+1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Reducing Agent Type | Chitosan | Trisodium Citrate |

| X2 | Concentration of Reducing Agent (mg) | 10 | 40 |

| X3 | Reaction Temperature (°C) | 60 | 100 |

| X4 | pH | 3.5 | 8.5 |

| X5 | Stirring Speed (rpm) | 400 | 1200 |

| X6 | Stirring Time (min) | 5 | 15 |

4. Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Gold Chloride Trihydrate (HAuCl₄) | Precursor for gold nanoparticle synthesis [20]. |

| Chitosan (Low MW) | Natural, biocompatible polymer; acts as a reducing and stabilizing agent for positively charged GNPs [20]. |

| Trisodium Citrate | Versatile and safer reagent; acts as a reducing and stabilizing agent for negatively charged GNPs [20]. |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | Used to create an acidic environment for chitosan dissolution and to adjust pH [20]. |

| Ultrapurified Water (Milli-Q) | Used for all reaction preparations to minimize contamination and ensure reproducible results [20]. |

5. Workflow Diagram

6. Procedure:

- Design Generation: Use statistical software (e.g., Design Expert, JMP, R) to generate the 16-run, randomized 26-2 design matrix [20].

- Synthesis: For each run in the randomized order, synthesize GNPs by adhering precisely to the factor levels specified in the design matrix.

- Characterization: For each synthesized GNP sample, measure the particle size (PS) and polydispersity index (PDI) using a dynamic light scattering instrument (e.g., Malvern Zetasizer) [20].

- Data Analysis:

- Input the response data (PS and PDI) for each run into the software.

- Fit a linear model to estimate the main effects of all six factors.

- Use a half-normal plot or Pareto chart to visually identify which main effects are significant [15].

- Examine the model to see which two-factor interactions are significant, keeping in mind the alias structure (e.g., the effect for X1X2 is confounded with X3X4) [18].

Design Selection Logic

What are Confounding and Aliasing?

In the context of screening experiments, aliasing (also called confounding) is a statistical phenomenon where the independent effects of two or more experimental factors become indistinguishable from one another based on the collected data [21] [22]. Think of it as having two different names for the same person; in your data, one calculated effect estimate is assigned to multiple potential causes [23].

This occurs because screening designs, such as fractional factorial designs, do not test all possible combinations of factor levels due to practical constraints. This intentional reduction in experimental runs creates an aliasing structure, where the effect of one factor is "aliased" with the effect of another [24] [21].

Why are Confounding and Aliasing a Problem in Screening Experiments?

Confounding is the core trade-off in efficient screening. Its primary problem is that it can lead to incorrect conclusions about which factors truly influence your process or product.

- Biased Effect Estimates: A significant effect might be due to factor A, its aliased interaction (e.g., BC), or a combination of both. You cannot determine the true source [24] [23].

- Hidden Important Effects: A crucial two-factor interaction might be missed because it is aliased with a main effect, and its impact is incorrectly attributed to that single factor.

- Wasted Resources: Basing process improvements or further experimentation on confounded results can lead to failed verification experiments and wasted time and materials.

The diagram below illustrates how aliasing leads to ambiguous conclusions.

A single estimated effect can result from multiple underlying sources.

How Can I Identify the Alias Structure of My Design?

Before conducting your experiment, it is critical to know the aliasing pattern of your chosen design. The alias structure defines how effects are combined [23].

- Use Statistical Software: Tools like Minitab, JMP, or Design-Expert will generate and display the complete alias structure for your design. This is the most reliable method [24].

- Interpret the Alias Table: The output will often list terms and their aliases. For example, in a resolution III design, you might see

[A] = A + BC, meaning the estimate for factor A is confounded with the BC interaction [23]. - Understand Resolution: The resolution of a design is a summary metric that indicates the severity of aliasing [21] [22]. The table below explains common resolution levels.

| Resolution | Meaning | Alias Pattern | Safe Use For |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Main effects are aliased with two-factor interactions. | e.g., A = BC |

Screening when assuming interactions are negligible [23] [22]. |

| IV | Main effects are aliased with three-factor interactions. Two-factor interactions are aliased with each other. | e.g., A = BCD, AB = CD |

Screening to get unbiased main effects, even if some 2FI exist [23]. |

| V | Main effects and two-factor interactions are aliased with higher-order interactions (three-factor or greater). | e.g., A = BCDE, AB = CDE |

Characterization/Optimization to clearly model main effects and 2FI [23]. |

What Practical Strategies Can Prevent Serious Confounding Issues?

Preventing confounding starts at the design stage. The goal is to manage aliasing, as it cannot be entirely avoided in fractional designs.

- Select a Design with Higher Resolution: If you suspect two-factor interactions (2FI) are important, choose a Resolution IV or V design. This ensures main effects are not aliased with any 2FI, protecting your conclusions about individual factors [23] [22].

- Use Sequential Experimentation: Start with a screening design to identify vital few factors. Then, run a follow-up experiment focusing on those factors with a larger design that can de-alias the important effects [25].

- Leverage Domain Knowledge: Use your process knowledge to choose a design where factors with potential interactions are not aliased with each other. If factors A and B are likely to interact, ensure the

ABinteraction is not aliased with the main effect of a third factor C [19]. - Consider Definitive Screening Designs (DSDs): DSDs are a modern class of designs that offer unique aliasing properties. In a DSD, all main effects are unaliased with any two-factor interaction, though two-factor interactions may be partially aliased with each other [24] [19].

The workflow below outlines a robust strategy to manage confounding.

A sequential approach to manage aliasing throughout an experimental program.

A Case Study: Managing Aliasing in Antiviral Drug Screening

A study investigating six antiviral drugs against Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) provides an excellent real-world example. Researchers used a Resolution VI fractional factorial design to screen the drugs in only 32 experimental runs (a half-fraction of the full 2^6=64 run design) [25].

- The Aliasing Structure: In this design:

- Main effects were aliased with five-factor interactions (e.g.,

A = BCDEF). - Two-factor interactions were aliased with four-factor interactions (e.g.,

AB = CDEF).

- Main effects were aliased with five-factor interactions (e.g.,

- The Assumption: The team assumed that fourth-order and higher interactions were negligible. This allowed them to clearly estimate all main effects and two-factor interactions from the data [25].

- The Outcome: The design successfully identified Ribavirin as the most influential drug and TNF-alpha as the least effective, guiding further research efficiently [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Design Concepts

The table below summarizes essential "reagents" for designing effective screening experiments and mitigating confounding bias.

| Concept | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Fractional Factorial Design (2^(k-p)) | Reduces the number of experimental runs by testing only a fraction of the full factorial combinations, making screening of many factors feasible [19] [22]. |

| Alias Structure | A table or equation that defines which effects are confounded with one another. It is the key to correctly interpreting results from a fractional design [24] [21]. |

| Design Resolution (III, IV, V) | A classification system that summarizes the aliasing pattern. It is the primary tool for selecting a design that provides the required level of effect separation [21] [23] [22]. |

| Sparsity of Effects Principle | A working assumption that systems are primarily driven by main effects and low-order interactions, while higher-order interactions are negligible. This justifies the use of fractional designs [22]. |

| Definitive Screening Design (DSD) | A modern three-level design that provides unaliased estimates of all main effects from any two-factor interactions, offering a robust screening option [24] [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a factor interaction, and why is it important in screening? A factor interaction occurs when the effect of one factor on the response depends on the level of another factor. In screening experiments, failing to identify significant interactions can lead to incomplete models and poor process optimization. Ignoring them may mean you miss the optimal combination of factor levels for your desired outcome [26] [27].

My screening design is of low resolution. What are the risks? Low-resolution designs (e.g., Resolution III) deliberately confound main effects with two-factor interactions. The primary risk is that you might mistakenly attribute an effect to a single factor when it is actually caused by an interaction between factors, or vice-versa. This can lead to incorrect conclusions about which factors are truly significant [27].

How can I investigate a suspected interaction after my initial screening? If your initial screening suggests that interactions may be present, you can refine your design. Techniques include:

- Folding: Adding a second experimental block that reverses the signs of the factors in the original design. This can help de-alias confounded effects.

- Adding Axial Runs: Introducing points along the axes of the factors to check for curvature or higher-order effects.

- Transitioning to a Full Factorial Design: If resources allow, running a full factorial design for the few critical factors will provide unambiguous estimates of all main effects and interactions [27].

What is the difference between a screening DOE and a full factorial DOE? A screening DOE (or fractional factorial DOE) uses a carefully selected subset of runs from a full factorial design to efficiently identify the most critical main effects. A full factorial DOE tests every possible combination of all factor levels, providing comprehensive information on all main effects and interactions but requiring more resources [27].

Can definitive screening designs detect interactions? Yes, definitive screening designs are a more advanced type of screening design that allow you to estimate not only main effects but also two-way interactions and quadratic effects, providing a more comprehensive understanding than traditional screening designs like Plackett-Burman [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Warning Signs of Potential Interactions

Use this guide to diagnose potential factor interactions in your screening data.

| Warning Sign | Description | Recommended Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Main Effects | The estimated effect of a factor changes dramatically when another factor is added to or removed from the model. | Conduct a factorial analysis for the suspected factors to isolate the interaction effect [26]. |

| Poor Model Fit | Your model shows a significant lack of fit, or the residuals (differences between predicted and actual values) are high and non-random. | Analyze the residual plots for patterns and consider adding interaction terms to the model [27]. |

| Factor Significance Conflicts | A factor is deemed insignificant in the screening model, but prior knowledge or mechanistic understanding suggests it should be important. | Suspect that the factor's effect is being confounded by an interaction. Use a higher-resolution design or a foldover to break the confounding [27]. |

| Non-Parallel Lines in Interaction Plots | When plotting the response for one factor across the levels of another, the lines are not parallel. Significant non-parallelism is a classic visual indicator of an interaction [26]. | Quantify the interaction effect by including the relevant two-factor interaction term in a new model. |

| Unexplained Response Variance | A large portion of the variation in your response data remains unexplained by the main effects alone (e.g., low R-squared value). | Include potential interaction terms in the model to see if they account for a significant portion of the previously unexplained variance [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing for Interactions After a Screening DOE

Objective: To confirm and quantify two-factor interactions suspected from an initial screening design.

Methodology:

- Identify Critical Factors: From your screening design, select the 2-4 most significant main factors for further investigation.

- Select a Design:

- For 2 or 3 factors, a Full Factorial Design is recommended to obtain clear estimates of all main effects and interactions [26].

- For 4 or more factors, a Higher-Resolution Fractional Factorial (e.g., Resolution V or higher) or a Definitive Screening Design can be used to estimate interactions without the full run count of a full factorial [27].

- Execute the Experiment: Run the selected design, randomizing the order of experimental runs to avoid confounding with lurking variables.

- Analyze the Data:

- Fit a model that includes the main effects and the two-factor interaction terms.

- Use ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) to test the statistical significance of the interaction terms.

- A low p-value (typically <0.05) for an interaction term indicates it is statistically significant.

- Interpret the Results:

- Create interaction plots to visualize how the effect of one factor changes across the levels of another.

- Use the model to understand the nature of the interaction and determine optimal factor level settings.

The logical workflow for this protocol is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Concepts for Interaction Analysis

This table details essential methodological concepts for designing experiments and diagnosing interactions.

| Concept / Tool | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Factorial Design | An experimental design that allows concurrent study of several factors by testing all possible combinations of their levels. It is the fundamental framework for estimating main effects and interactions [26]. |

| Screening DOE (Fractional Factorial) | An efficient experimental design that uses a subset of a full factorial to identify the most significant main effects. Its primary purpose is to reduce the number of experimental runs, but this comes at the cost of confounding interactions with main effects [27]. |

| Resolution | A property of a fractional factorial design that describes the degree to which estimated effects are confounded (aliased). Resolution III designs confound main effects with two-factor interactions, while Resolution IV designs confound two-factor interactions with each other [27]. |

| Interaction Plot | A line graph that displays the mean response for different levels of one factor, with separate lines for each level of a second factor. Non-parallel lines provide a clear visual signal of a potential interaction [26]. |

| Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | A statistical method used to analyze the differences among group means in a sample. In the context of factorial designs, ANOVA partitions the total variability in the data into components attributable to each main effect and interaction, testing them for statistical significance [26]. |

Understanding how design resolution affects what you can learn from an experiment is critical. The following diagram illustrates the key confounding patterns in common design types.

Advanced Methods for Detecting and Modeling Interactions in Screening Experiments

Core Concepts and Relevance

What is Bayesian-Gibbs Analysis and why is it crucial for detecting interactions in chemical screening?

Bayesian-Gibbs analysis, specifically Gibbs sampling, is a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm used to sample from complex multivariate probability distributions when direct sampling is difficult. It works by iteratively sampling each variable from its conditional distribution given the current values of all other variables [28].

In chemical screening experiments, such as Plackett-Burman (PB) designs, this method is vital because it enables researchers to detect significant factor interactions that traditional screening methods often miss. PB designs are highly economical but typically confound main effects with two-factor interactions, making it impossible to distinguish true interactions using standard analysis. Bayesian-Gibbs sampling overcomes this limitation by allowing for the estimation of both main effects and interaction terms from limited experimental data [29].

Workflow and Implementation

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Implementing Bayesian-Gibbs Analysis

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Design Selection: Choose a Plackett-Burman design matrix suitable for your number of factors (e.g., a 12-run design for up to 11 factors) [29].

- Experimental Execution: Conduct the experiments precisely as dictated by the design matrix, randomizing the run order to minimize bias.

- Data Recording: Record the response measurement for each experimental run.

Phase 2: Model Specification

- Define the Statistical Model: For a screening design with

kfactors, specify a model that includes main effects and two-factor interactions:y = β₀ + ∑βᵢxᵢ + ∑∑βᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + e[29] - Set Prior Distributions: Assign prior distributions for all model parameters (β coefficients, error variance). Weakly informative or conjugate priors are often used to facilitate computation [30] [28].

Phase 3: Gibbs Sampling Execution

- Algorithm Initialization: Choose starting values for all parameters, either randomly or based on a preliminary model fit [28].

- Iterative Sampling Cycle: For a large number of iterations (e.g., 10,000+), repeatedly sample each parameter from its full conditional distribution:

- Sample

β₁fromP(β₁ | β₂, β₃, ..., σ², y) - Sample

β₂fromP(β₂ | β₁, β₃, ..., σ², y) - ...

- Sample

σ²fromP(σ² | β₁, β₂, ..., y)[28]

- Sample

- Convergence Monitoring: Check that the Markov chain has converged to the target posterior distribution using diagnostic tools like trace plots and the Gelman-Rubin statistic.

Phase 4: Posterior Analysis and Inference

- Burn-in Removal: Discard the initial samples from the "burn-in" period before the chain converged [28].

- Calculate Posterior Summaries: Compute the posterior mean, median, and credible intervals for each β coefficient from the remaining samples.

- Identify Significant Effects: Factors and interactions whose credible intervals exclude zero are deemed statistically significant.

Workflow Visualization

Troubleshooting Common Issues

What should I do if my Gibbs sampler shows poor convergence or high autocorrelation?

- Problem: The trace plots for parameters show a "random walk" or high autocorrelation between successive samples, indicating slow mixing.

- Solution:

- Increase the number of iterations and burn-in period.

- Apply thinning by saving only every

n-thsample (e.g., every 5th or 10th) to reduce autocorrelation [28]. - Consider using advanced techniques like simulated annealing during the early sampling phase or collapsed Gibbs sampling to improve efficiency [28].

How do I validate that the identified interactions are statistically significant and not artifacts?

- Problem: Uncertainty in distinguishing true interactions from random noise or model artifacts.

- Solution:

- Check the posterior probability or 95% credible intervals for the interaction coefficients. Effects where the interval excludes zero provide strong evidence [29] [28].

- Validate the model using a heredity principle. Strong heredity requires that an interaction

x₁x₂is only considered if both main effectsx₁andx₂are also significant, which can be incorporated as a prior constraint [30] [29]. - Run the analysis on simulated data with known effects to verify the method's performance.

The model is too complex, and I have limited data. How can I simplify it?

- Problem: With many factors, the number of possible interactions is large, leading to a model that is too complex for the available data.

- Solution:

- Incorporate the sparsity principle (most effects are negligible) and the heredity principle (interactions are only possible if parent main effects are active) into the model priors [30] [29].

- Use a Bayesian variable selection approach that allows coefficients to be shrunk towards zero or excluded from the model.

Key Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Interaction Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Technical Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plackett-Burman Design Matrix | Defines the factor level combinations for each experimental run. | An orthogonal 2-level design. A 12-run matrix can screen up to 11 factors [29]. |

| Bayesian Statistical Software | Platform for implementing Gibbs sampling and posterior analysis. | Common choices include R with packages like R2OpenBUGS, rstan, or MCMCpack; Python with PyMC3; or dedicated software like OpenBUGS/WinBUGS [29]. |

| Weakly Informative Priors | Regularize parameter estimates, preventing overfitting, especially for complex interaction models. | Common choices: Normal priors for β coefficients (mean=0), Gamma or Inverse-Gamma priors for precision (1/σ²) [30] [28]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay | Measures the chemical or biological response for each experimental run. | Must be robust, reproducible, and have a sufficient signal window to detect changes across factor settings [31]. |

Advanced Analysis and Interpretation

How do I interpret the final output and what are the logical next steps?

Phase 5: Interpretation and Reporting

- Effect Size Evaluation: The magnitude of the posterior mean for a β coefficient indicates the strength of the main effect or interaction.

- Practical Significance: Combine statistical significance with domain knowledge to assess the practical importance of the detected interactions.

- Model Validation: If resources allow, run a small set of confirmation experiments at factor levels predicted by the model to validate the findings.

Analysis Results Visualization

Table 2: Key Diagnostic Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Target Value/Range | Interpretation & Action |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Sample Size (ESS) | > 400 per parameter | A low ESS indicates high autocorrelation; consider increasing iterations or thinning [28]. |

| Gelman-Rubin Statistic (R-hat) | ≈ 1.0 (e.g., < 1.1) | Values significantly >1 suggest the chains have not converged; run more iterations [28]. |

| 95% Credible Interval | Does not contain zero | The factor or interaction has a statistically significant effect on the response. |

| Posterior Probability | > 0.95 (for inclusion) | Strong evidence that the effect is real and not zero. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a Genetic Algorithm over traditional screening methods for uncovering factor interactions?

Traditional methods like full factorial designs become computationally prohibitive as the number of factors increases, as the number of experiments required grows exponentially [1]. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are powerful combinatorial optimization tools that do not need to test every possible combination [32]. Instead, they start with a population of random solutions and use selection, crossover, and mutation to evolve increasingly fit solutions over generations [33]. This allows them to efficiently navigate vast experimental spaces and naturally uncover complex, non-linear interactions between factors that traditional methods might miss, as the effect of one variable depends on the level of another [32] [34] [1].

FAQ 2: How do I interpret a statistically significant interaction effect identified by my model?

A significant interaction effect means the effect of one independent variable on your response depends on the value of another variable [34]. It is an "it depends" effect [34]. For example, in a regression model with an interaction term (e.g., Height = B0 + B1*Bacteria + B2*Sun + B3*Bacteria*Sun), you cannot interpret the main effects (B1 or B2) in isolation [35]. The unique effect of Bacteria is given by B1 + B3*Sun [35]. This means you have different slopes for the relationship between Bacteria and Height at different levels of Sun. The best way to interpret a significant interaction is to visualize it using an interaction plot [34] [36].

FAQ 3: Our GA is converging too quickly to a solution and lacks diversity. What parameters can we adjust?

Premature convergence is a common challenge where the population becomes homogeneous too early, potentially trapping the algorithm in a local optimum [37]. To encourage greater exploration:

- Increase Mutation Rates: Introduce more random tweaks to create new genetic diversity [32] [38].

- Modify Selection Pressure: Adjust your selection criteria to allow some less-fit individuals to contribute to the next generation, preserving potentially useful genetic material [32] [38].

- Introduce Specific Mutation Steps: As done in the REvoLd protocol, you can add a mutation step that switches single fragments to low-similarity alternatives, keeping well-performing parts intact but enforcing significant changes in small areas [38].

- Implement a Second Round of Crossover: Allow worse-scoring ligands to improve and carry their molecular information forward, which can help escape local optima [38].

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations for designing a fitness function in a GA for chemical screening?

The fitness function is critical as it guides the evolutionary search.

- Define a Clear Objective: The function should directly reflect the primary goal of your screen, such as binding affinity, selectivity, or a desired physicochemical property [38] [33].

- Incorporate Multiple Objectives: If needed, the function can be designed to handle multiple, competing objectives simultaneously (e.g., optimizing potency while minimizing toxicity) [32].

- Ensure Computational Efficiency: Since the fitness function will be evaluated thousands of times, it must be computationally efficient. In drug discovery, this often involves a scoring function from a molecular docking simulation [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: The Algorithm Fails to Find Improved Solutions Over Generations

This issue, known as stagnation, can occur when the GA is trapped in a local optimum or lacks the diversity to find better paths.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Premature Convergence | Plot the fitness of the best solution per generation. If the fitness curve flattens early, convergence is likely premature. | Increase the population size and adjust the mutation rate. Introduce nicheing or crowding techniques to maintain population diversity [37]. |

| Insufficient Exploration | Analyze the diversity of the population's genetic material over time. | Incorporate specific mutation operators that promote exploration, such as switching fragments to low-similarity alternatives [38]. Run multiple independent GA runs with different random seeds to explore different paths [38]. |

| Poorly Calibrated Parameters | Systematically test different combinations of population size, mutation rate, and crossover rate. | Use experimental design and parameter tuning studies to find a robust configuration [37]. For example, one benchmark found a population of 200, with 50 individuals advancing, over 30 generations was effective [38]. |

Issue 2: Difficulty in Validating and Interpreting Identified Factor Interactions

Once a GA suggests that certain factor interactions are important, you need to statistically validate and understand these relationships.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Confounding of Effects | In highly fractional designs, main effects and interactions can be confounded (aliased), making it difficult to isolate the true cause [1]. | Verify the resolution of your experimental design. A higher resolution (e.g., Resolution V) ensures that main effects and two-factor interactions are not confounded with each other [1]. |

| Complex Higher-Order Interactions | A three-factor interaction indicates that the two-factor interaction itself depends on the level of a third variable [26]. This is challenging to interpret. | Use visualization tools. Create interaction plots for the key factors identified by the GA. For continuous variables, plot the relationship at different levels (e.g., low, medium, high) of the moderator variable [34] [36]. |

| Lack of Statistical Significance | The interaction may be suggested by the GA's fitness function but not be statistically significant in a formal model. | After the GA narrows the field, conduct a follow-up confirmatory experiment or analysis. Fit a traditional statistical model (like ANOVA or regression) with the relevant interaction terms and test their p-values [34]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Grouping Genetic Algorithm (GGA) for Complex Optimization

Grouping Genetic Algorithms are a variant of GAs specifically designed for problems where the solution involves partitioning a set of items into groups [37].

1. Problem Definition and Representation:

- Define the set of items

Vthat need to be partitioned. - Design a grouping-based representation for the genome. Each individual in the population represents a candidate grouping of the items.

- Formulate the objective function (fitness function) that evaluates the quality of a grouping, such as minimizing the makespan in a machine scheduling problem [37].

2. Initialization:

- Generate an initial population of candidate groupings. This can be done randomly or using a heuristic that incorporates domain-specific knowledge to create better starting solutions [37].

3. Selection and Reproduction:

- Selection: Select parent solutions for reproduction based on their fitness. Common methods include tournament selection or roulette wheel selection.

- Crossover (Grouping-Specific): Implement a crossover operator that works at the group level. For example, the "cross" operator selects random groups from two parents and injects them into the offspring, then repairs the solution to ensure it is valid [37].

- Mutation: Apply mutation operators that alter the group structure, such as moving an item from one group to another or swapping items between groups [37].

4. Evaluation and Termination:

- Evaluate the fitness of the new offspring population.

- Check for termination criteria (e.g., a maximum number of generations, convergence of the fitness score).

- If criteria are not met, return to Step 3.

The workflow for this GGA is as follows:

Protocol: Screening for False Positives in Hit Identification

In chemical screening, it is critical to filter out compounds that appear active due to assay interference mechanisms rather than genuine biological activity [39].

1. Data Preparation:

- Collect the chemical structures of hit compounds identified from your primary screen (e.g., from a GA-driven docking study).

- Standardize the molecular structures (e.g., remove salts, neutralize charges, add explicit hydrogens) using cheminformatics software like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [39].

2. In-silico Screening with ChemFH Platform:

- Submit the standardized structures to the ChemFH online platform.

- ChemFH uses a Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) model trained on over 800,000 compounds to predict various interference mechanisms, including:

- Colloidal aggregators

- Fluorescent compounds

- Firefly luciferase (FLuc) inhibitors

- Chemically reactive compounds

- Promiscuous compounds [39]

- The platform also screens against a library of 1,441 representative alert substructures and ten commonly used frequent hitter rules (e.g., PAINS) [39].

3. Results Interpretation and Triage:

- Review the ChemFH report. Compounds flagged as potential false positives should be considered lower priority for follow-up.

- For the remaining compounds, consider conducting experimental counter-screens to confirm activity, such as adding non-ionic detergents to test for aggregation [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Relevance to Genetic Algorithms & Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| RosettaEvolutionaryLigand (REvoLd) | An evolutionary algorithm for optimizing entire molecules from ultra-large "make-on-demand" chemical spaces (like Enamine REAL) using flexible protein-ligand docking in Rosetta [38]. | Directly implements a GA for chemical screening. It efficiently explores combinatorial libraries to find high-scoring ligands, naturally accounting for complex interactions between molecular fragments. |

| ChemFH Platform | An integrated online tool that uses a Directed Message-Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) to screen compounds and identify frequent false positives caused by various assay interference mechanisms [39]. | A crucial post-screening validation tool. After a GA identifies potential hits, ChemFH helps triage them by flagging compounds whose "fitness" may be due to experimental artifacts rather than true interactions. |

| Plackett-Burman Designs | A type of highly fractional factorial design used for screening a large number of factors with a very small number of experimental runs [1]. | Useful for the initial phase of experimental design to identify a subset of important factors from a large pool, which can then be optimized in more detail using a GA. |

| Fractional Factorial Designs | Experimental designs that consist of a carefully chosen fraction of the runs of a full factorial design, used to screen many factors efficiently [1]. | Helps estimate main effects and lower-order interactions when resources are limited. Understanding their properties (like resolution and confounding) is key to designing the experiments a GA might optimize. |

| Directed Message Passing Neural Network (DMPNN) | A graph-based machine learning architecture that learns molecular encodings for property prediction, often outperforming traditional descriptors [39]. | Can be used as a highly accurate and computationally efficient fitness function within a GA framework, evaluating the properties of candidate molecules without requiring physical synthesis or testing. |

Integrating Computational Screening with Experimental Design

FAQs: Navigating Computational-Experimental Integration

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of integrating machine learning with DNA-encoded library (DEL) screening in early drug discovery?

Integrating ML with DEL screening solves a key paradox in drug discovery: the most novel drug targets typically have the least amount of historical chemical data, which is precisely what ML models need to be effective. DEL screening rapidly generates millions of chemical data points through DNA sequencing, creating a substantial data resource from a single experiment. This provides the critical mass of data needed to train effective ML models, even for unprecedented targets, significantly accelerating the identification of binders for novel proteins [40].

FAQ 2: How can we account for factor interactions in screening experiments when the number of potential interactions is vast compared to the number of experimental runs?

Traditional methods that consider all possible two-factor interactions simultaneously can struggle with this complexity. A modern approach is GDS-ARM (Gauss-Dantzig Selector–Aggregation over Random Models). This method applies a variable selection algorithm multiple times, each time with a randomly selected subset of two-factor interactions. It then aggregates the results across these many models to identify the truly important factors and interactions, effectively managing complexity without requiring an impractically large number of experimental runs [41].

FAQ 3: When is it better to use a physics-based modeling tool like Rosetta versus an AI-based predictor like AlphaFold for protein therapeutic design?

The choice depends on the specific engineering goal:

- AlphaFold excels at predicting the static, native structures of monomeric proteins with high accuracy and is superb for assessing natural sequence variations [42].

- Rosetta is often more suitable for tasks requiring the modeling of conformational changes, protein complexes, and the structural consequences of point mutations. Its physics-based energy functions and flexibility make it particularly valuable for de novo protein design, enzyme engineering, and predicting the stability of designed protein variants [42].

FAQ 4: What is "shift-left accessibility" in the context of computational experimental design, and why is it important?

"Shift-left accessibility" is a principle that advocates for integrating essential checks and tools directly into the early development workflow, rather than addressing them as an afterthought. In computational-experimental integration, this means generating critical metadata (like alt-text for UI icons in an automated assay analysis app) during the development phase itself. This practice reduces technical debt, prevents omissions, and is more efficient than post-development fixes, ensuring the final tool is robust and compliant from the start [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Positive Rates in Factor Screening

Problem: Your screening experiment is identifying too many factors as "important," leading to wasted resources in follow-up experiments.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unaccounted Interactions | Analyze residuals for patterns. Are effects not explained by the main-effects model? | Use a screening method like GDS-ARM that explicitly accounts for two-factor interactions without requiring a full-model analysis [41]. |

| Overly Sensitive Selection Threshold | Check if the tuning parameter (e.g., δ in GDS) is too low, including negligible effects. | Implement a cluster-based tuning method. Apply k-means clustering (with k=2) on the absolute values of the effect estimates to separate active effects from noise automatically [41]. |

| Effect Sparsity Violation | The number of active effects may be too high for the screening design used. | Re-evaluate the experimental system. Re-run the screening with more runs or a different design if the process is not sparse. |

Issue 2: Poor Performance of Machine Learning Models on Novel Targets

Problem: Predictive models for a new drug target are inaccurate due to a lack of training data.

| Symptom | Underlying Issue | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| No known ligands or chemical data for the target. | ML models cannot be trained effectively, creating a discovery bottleneck. | Integrate DNA-encoded library (DEL) screening to rapidly generate a large dataset of binding compounds. Use the sequencing data from the DEL output to train the ML model, creating a powerful discovery cycle [40]. |

| Models trained on limited HTS data fail to generalize. | The dataset is too small and lacks the diversity needed for a robust model. | Leverage the large and diverse chemical space explored by a DEL (billions of compounds) to produce a rich and informative dataset for ML training [40]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the GDS-ARM Method for Factor Screening

Objective: To identify important main effects and two-factor interactions in a screening experiment with a large number of factors (m) and a limited number of runs (n).

Materials:

- Experimental data (response measurements for each run).

- Design matrix of factor settings.

- Statistical software with GDS and k-means clustering capabilities.

Methodology:

- Model Setup: Define the full model containing all

mmain effects and allk = m(m-1)/2two-factor interactions. - Random Subset Generation: For

t = 1toT(e.g., T=1000) iterations, generate a random subset that includes all main effects and a random selection of the two-factor interactions. - GDS Application: For each random subset, apply the Gauss-Dantzig Selector over a range of tuning parameters (δ) to obtain estimates of the coefficients,

βˆ(δ). - Cluster-Based Tuning: For each

βˆ(δ), apply k-means clustering with two clusters to the absolute values of the estimates. Refit a model using ordinary least squares (OLS) containing only the effects in the cluster with the larger mean. - Model Selection: Choose the value of δ that minimizes a model selection criterion (e.g., AIC or BIC) from the OLS models.

- Aggregation: Aggregate the results across all

Titerations. Calculate the frequency with which each effect was selected. Declare effects with a selection frequency above a chosen threshold as "active."

Diagram: GDS-ARM Workflow

Protocol 2: Integrating DEL Screening with Machine Learning for Novel Target Hit Identification

Objective: To rapidly discover binders for a novel protein target with no prior chemical data by combining DEL screening with machine learning.

Materials:

- Purified target protein.

- DNA-encoded chemical library (DEL).

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform.

- ML modeling software/environment.

Methodology:

- DEL Selection: Incubate the purified target protein with the DEL. Perform rigorous washing to remove non-binders and elute specifically bound compounds.

- DNA Sequencing & Data Generation: Isolate the DNA tags from the enriched compounds and sequence them using NGS. Map the DNA sequences back to the corresponding chemical structures, generating a list of millions of enriched compounds and their relative frequencies.

- Model Training: Use the DEL enrichment data (compounds and their counts) to train a machine learning model. The model learns to distinguish structural features that correlate with binding to the target.

- Virtual Screening: Use the trained ML model to screen a large, virtual chemical library (e.g., a commercial vendor's catalog). The model predicts and ranks compounds based on their likelihood of binding.

- Validation: Purchase the top-ranked compounds from the virtual screen and test them experimentally in a binding assay (e.g., SPR) to validate the ML predictions.

Diagram: DEL + ML Hit Identification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Computational-Experimental Integration |

|---|---|

| DNA-Encoded Library (DEL) | A vast collection of small molecules, each tagged with a unique DNA barcode, enabling highly parallelized binding assays and the generation of massive datasets for machine learning [40]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive macromolecular modeling software for de novo protein design, predicting the effects of mutations on stability, and engineering protein-protein interactions [42]. |

| AlphaFold & RoseTTAFold | Deep learning systems that provide highly accurate protein structure predictions from amino acid sequences, serving as critical starting points for structure-based design efforts [42]. |

| Gauss-Dantzig Selector (GDS) | A statistical variable selection method used in screening experiments to identify important factors from a large set of candidates under sparsity assumptions [41]. |

| Pix2Struct / PaliGemma | Vision-Language Models (VLMs) fine-tuned for UI widget captioning; can be adapted to interpret and label graphical data from automated assay systems, though they perform best on complete screens [43]. |

Factor Analysis for Interactions (FIN) is a Bayesian latent factor regression framework designed to reliably infer interactions in high-dimensional data where predictors are moderately to highly correlated. It is particularly valuable in chemical screening experiments, where exposures are often correlated within blocks due to co-occurrence in the environment or because measurements consist of metabolites from a parent compound [30].

Traditional quadratic regression, which includes all pairwise interactions, becomes computationally prohibitive as the number of parameters scales with (2p + \binom{p}{2}). FIN overcomes this by modeling the observed data (chemical exposures) and the response (health outcome) as functions of a shared set of latent factors. Interactions are then modeled within this reduced latent space, inducing a flexible dimensionality reduction [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using FIN over standard regression for detecting interactions in chemical mixtures?

FIN offers several key advantages [30]:

- Handles Correlated Predictors: It is designed for scenarios where chemical exposures are highly correlated, avoiding the problems of collinearity that plague standard regression.

- Dimensionality Reduction: By working in a lower-dimensional latent space, it makes the estimation of interactions tractable even for a moderate number of chemicals (p between 20 and 100).

- Uncertainty Quantification: As a Bayesian method, it provides full posterior distributions for parameters, allowing for natural uncertainty quantification on the estimated interactions.

- No Strict Sparsity Needed: It does not rely on strong sparsity assumptions, which is appropriate when blocks of correlated chemicals are likely to have effects.

Q2: How does FIN relate to other Bayesian factor models for multi-study or multi-omics data?

FIN is part of a family of advanced Bayesian factor models. While FIN specifically focuses on modeling interactions via quadratic terms in the latent factors, other models are designed for different integration tasks. The table below summarizes some related methods [44]:

| Model Acronym | Full Name | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| FIN | Factor analysis for INteractions | Modeling interactions in high-dimensional, correlated data (e.g., chemical mixtures). |

| PFA | Perturbed Factor Analysis | Multi-study integration to disentangle shared and study-specific signals. |

| BMSFA | Bayesian Multi-study Factor Analysis | Integrating multiple related studies to find shared and individual factor structures. |