Wavefunction vs. Density Functional Theory: A Practical Guide for Quantum Methods in Drug Discovery

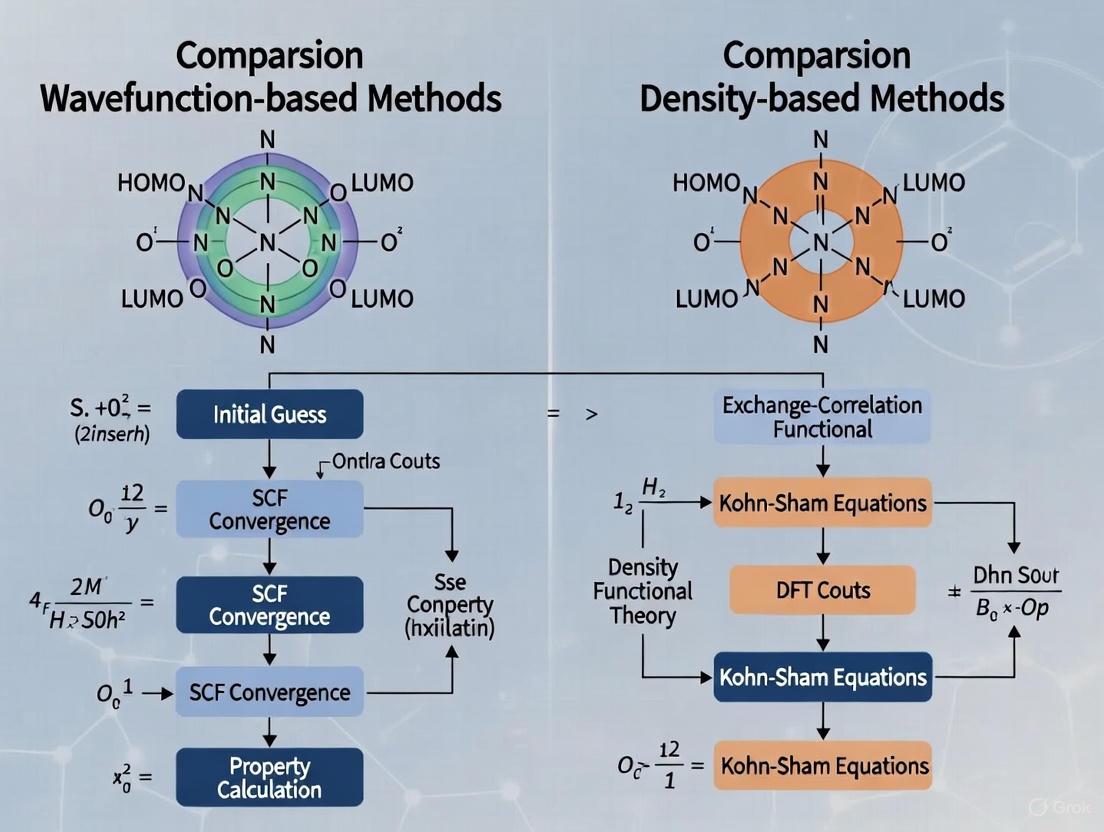

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of wavefunction-based and density-based quantum mechanical methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Wavefunction vs. Density Functional Theory: A Practical Guide for Quantum Methods in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of wavefunction-based and density-based quantum mechanical methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, from the complex coupled electron-photon wavefunctions in QED to the electron density focus of DFT. The scope extends to their practical applications in simulating protein-ligand interactions, predicting drug properties, and optimizing discovery workflows. The content addresses key challenges such as computational cost and system size limitations, offering insights into hybrid strategies and error-correction techniques. Finally, it delivers a validated comparative analysis of accuracy, scalability, and resource requirements, serving as a strategic guide for method selection in biomedical research.

Quantum Foundations: From First Principles to Computational Reality in Chemistry

The Schrödinger Equation and the Fundamental Quantum Many-Body Problem

The Schrödinger equation is the fundamental cornerstone of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, providing a mathematical framework for describing the behavior of quantum systems [1] [2]. This partial differential equation, formulated by Erwin Schrödinger in 1926, represents the quantum counterpart to Newton's second law in classical mechanics, enabling predictions of how quantum systems evolve over time [1]. While the equation can be written compactly as iℏ∂Ψ/∂t = ĤΨ, its analytical solution remains intractable for most multi-particle systems due to the exponential scaling of complexity with particle number [3] [4]. The wave function Ψ for an N-particle system exists in a 3N-dimensional configuration space, making exact numerical solutions computationally prohibitive for all but the simplest systems [3]. This fundamental limitation, often termed the "quantum many-body problem," represents one of the most significant challenges in modern theoretical physics and quantum chemistry, driving the development of numerous approximation strategies that form the basis of contemporary electronic structure theory [4].

The computational burden of the quantum many-body problem dramatically exceeds that of its classical counterpart. While classical N-body problems require tracking O(2^N) possible states, quantum systems necessitate O(2^(2^N)) variables to represent due to the need to capture all possible superpositions and associated phase information [3]. This double exponential complexity means that simulating quantum systems exactly is believed to be impossible for large N, in contrast to classical systems which can be simulated in polynomial time [3]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of the two dominant families of approaches developed to overcome this challenge: wavefunction-based methods and density-based methodologies, examining their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and applicability across different scientific domains.

Methodological Approaches: A Comparative Framework

Wavefunction-Based Methods

Wavefunction-based approaches directly approximate the many-body wavefunction Ψ, employing various strategies to manage its computational complexity:

Hartree-Fock (HF) and Post-HF Methods: The Hartree-Fock method represents the simplest wavefunction approach, expressing the many-body wavefunction as a single Slater determinant of molecular orbitals [4]. While computationally efficient, HF fails to capture electron correlation effects, leading to the development of post-Hartree-Fock methods including Configuration Interaction (CI), Perturbation Theory (MP2, MP4), and Coupled-Cluster (CC) techniques [4]. These methods systematically improve upon the HF solution by introducing excited configurations, with coupled-cluster singles and doubles with perturbative triples (CCSD(T)) often considered the "gold standard" for molecular energy calculations when computationally feasible.

Compressed Wavefunction Representations: More advanced wavefunction methods employ compressed representations to reduce computational demands. The Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) represents the wavefunction as a matrix product state, particularly effective for one-dimensional quantum lattice systems [5]. Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) methods use stochastic sampling to estimate wavefunction properties, while tensor network states provide efficient representations for weakly entangled systems [5] [4].

Time-Dependent Formulations: For dynamical properties, time-dependent variants of these methods have been developed, including time-dependent coupled-cluster (TD-CC) and multiconfigurational time-dependent Hartree-Fock (MCTDHF) approaches [6]. These enable the study of quantum dynamics following external perturbations, though their accuracy depends strongly on the level of correlation included and the strength of the external driving fields [7].

Density-Based Methods

Density-based approaches circumvent the direct calculation of the wavefunction by focusing on the electron density as the fundamental variable:

Density Functional Theory (DFT): Founded on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that all ground-state properties are uniquely determined by the electron density [3] [4]. In practice, DFT employs the Kohn-Sham scheme, which introduces a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that reproduces the same density as the real interacting system [3]. The critical challenge in DFT is the exchange-correlation functional, which must approximate all non-classical electron interactions. Popular functionals include the Local Density Approximation (LDA), Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), meta-GGAs, and hybrid functionals that incorporate exact exchange [4].

Green's Functions Methods (GW): The GW approximation provides a powerful approach for calculating excited-state properties, particularly quasiparticle energies as measured in photoemission spectroscopy [7] [6]. Named for its mathematical form (G for the Green's function, W for the screened Coulomb interaction), this method has become the method of choice for band structure calculations in materials science [6]. The approach can be formulated as an effective downfolding of the many-body Hamiltonian into a single-particle picture with dynamically screened interactions [7].

Time-Dependent Extensions: Time-Dependent DFT (TDDFT) and non-equilibrium Green's functions (NEGF) extend these approaches to dynamical situations, enabling the study of spectroscopic properties, transport phenomena, and real-time evolution of quantum systems under external drives [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Quantum Many-Body Approaches

| Characteristic | Wavefunction-Based Methods | Density-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Variable | Many-body wavefunction Ψ | Electron density n(r) or Green's function G |

| Theoretical Foundation | Variational principle | Hohenberg-Kohn theorems (DFT), Many-body perturbation theory (GW) |

| Systematic Improvability | Yes (with increasing excitation level) | Limited by functional development |

| Computational Scaling | HF: O(N⁴), MP2: O(N⁵), CCSD(T): O(N⁷) | DFT: O(N³), GW: O(N⁴) |

| Treatment of Correlation | Explicit (but approximate) | Implicit via exchange-correlation functional |

| Strong Correlation Handling | Challenging but possible with sophisticated methods | Generally poor with standard functionals |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Assessment

Equilibrium Properties and Ground-State Accuracy

For weakly correlated systems at equilibrium, both methodological families can achieve impressive accuracy, though with different computational costs and limitations:

Weak Correlation Regime: Coupled-cluster methods (particularly CCSD(T)) typically provide exceptional accuracy for molecular geometries, reaction energies, and interaction energies, often achieving chemical accuracy (errors < 1 kcal/mol) for systems where they are computationally feasible [4]. Density-based methods with sophisticated hybrid functionals can also achieve good accuracy at lower computational cost, though with less systematic improvability [3].

Strong Correlation Regime: Systems with strong electron correlation, such as transition metal complexes, frustrated magnetic systems, and high-temperature superconductors, present significant challenges for both approaches. Wavefunction methods require high levels of excitations or specialized coupled-cluster variants, dramatically increasing computational cost [7] [6]. Standard DFT functionals often fail qualitatively for strongly correlated systems, though approaches like DFT+U and range-separated functionals can provide partial solutions [4].

Extended Systems: For periodic solids and extended systems, DFT with plane-wave basis sets has become the dominant approach due to its favorable scaling and reasonable accuracy for ground-state properties like lattice constants, bulk moduli, and phonon spectra [3]. The GW method provides more accurate band gaps and quasiparticle excitations, bridging the gap between wavefunction and density-based approaches [6].

Non-Equilibrium Dynamics and Driven Systems

Recent advances in ultrafast spectroscopy and quantum control have heightened interest in non-equilibrium quantum dynamics, where the performance characteristics of different methods diverge more significantly:

Weak Driving Fields: Under weak external perturbations, time-dependent coupled-cluster methods demonstrate practically exact performance for weakly to moderately correlated systems, accurately capturing the coherent evolution of the many-body wavefunction [7] [6]. Linear-response TDDFT also performs reasonably well for calculating excitation energies and weak field responses, though with known limitations for charge-transfer states and double excitations [6].

Strong Driving Fields: Under intense external drives that push systems far from equilibrium, both methodologies face significant challenges. Coupled-cluster methods struggle as the system develops strong correlations, measured by increased von Neumann entropy of the single-particle density matrix [7] [6]. The GW approximation, while less accurate than coupled-cluster in weak fields, shows improved performance relative to mean-field results in strongly driven regimes [7]. The breakdown of methods under strong driving is often associated with the development of entanglement patterns and correlation structures not captured by the approximations [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Under Non-Equilibrium Conditions

| Condition | Wavefunction Methods | Density-Based Methods | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Perturbations | Excellent performance for weak to moderate correlation | Good performance with modern functionals | Linear response functions, excitation energies |

| Strong Driving Fields | Performance degrades with increasing correlation strength | GW improves upon mean-field, limited by approximation | Von Neumann entropy, natural orbital populations [7] |

| Long-Time Dynamics | Challenges with wavefunction propagation | Dephasing and memory issues in NEGF | Thermalization, relaxation timescales |

| Computational Cost | High for correlated methods, steep scaling | Moderate for DFT, higher for GW | Scaling with system size and simulation time |

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

The practical application of these theoretical approaches requires specialized computational tools and "research reagents" that form the essential toolkit for quantum many-body simulations:

Electronic Structure Codes: Software packages such as VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, and GPAW implement density-based methods with periodic boundary conditions, essential for materials modeling [3]. For molecular systems, NWChem, PySCF, and Q-Chem provide comprehensive implementations of both wavefunction and density-based methods [4].

Wavefunction Solvers: Specific tools like ChemShell and Molpro offer sophisticated wavefunction-based approaches including high-level coupled-cluster methods and multi-reference techniques for challenging electronic structures [4]. The ALPS (Algorithms and Libraries for Physics Simulations) package provides implementations of DMRG and other tensor network methods for strongly correlated lattice systems [5].

Quantum Dynamics Packages: The TTM (Transport and Thermalization Methods) library and specialized codes for the Kadanoff-Baym equations enable the study of non-equilibrium dynamics using Green's functions techniques [6]. The MCTDH (Multi-Configurational Time-Dependent Hartree) package offers powerful tools for wavefunction-based quantum dynamics [6].

Benchmark Datasets: Carefully constructed benchmark sets like the GMTKN55 database for molecular energies and the CMT-Benchmark for condensed matter problems provide essential validation for methodological development [5]. These datasets, often featuring numerically exact results for small systems or high-quality experimental data, enable objective performance comparisons between methodologies [7].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum Many-Body Research

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Application | Methodological Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Platforms | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, NWChem | Materials and molecular modeling | DFT, GW, Wavefunction methods |

| High-Performance Computing | CPU/GPU hybrid algorithms, Tensor network libraries | Large-scale simulations | Scalable implementations for complex systems |

| Benchmarking Resources | GMTKN55, CMT-Benchmark | Method validation and development | Performance assessment across diverse systems |

| Visualization & Analysis | VESTA, ChemCraft, VMD | Structure-property relationships | Data interpretation and presentation |

Experimental Protocols: Methodological Details

Performance Assessment Methodology

Recent systematic comparisons between wavefunction and density-based methods employ rigorous protocols to ensure meaningful performance assessments:

Reference Data Generation: For non-equilibrium dynamics, numerically exact results are generated for small systems using full configuration interaction (FCI) or exact diagonalization where feasible [7]. These serve as benchmarks for assessing approximate methods. For larger systems, quantum Monte Carlo with controlled approximations or experimental results from ultrafast spectroscopy provide reference data [6].

Correlation Strength Quantification: The performance of different methodologies is correlated with quantitative measures of electron correlation, particularly the von Neumann entropy of the one-particle density matrix, which provides a robust metric for correlation strength [7]. Natural orbital occupation numbers further characterize correlation patterns, with significant deviations from 0 or 1 indicating strong correlation [6].

Dynamical Propagation Protocols: For time-dependent comparisons, standardized excitation protocols are employed, such as sudden quenches of system parameters or controlled external field drives with specific amplitudes and durations [7]. The evolution of observables like double occupancies, momentum distributions, and spectral functions are tracked across multiple timescales to assess method performance [6].

Convergence and Error Analysis

Robust methodological comparisons require careful attention to convergence metrics and systematic error analysis:

Basis Set Convergence: Both wavefunction and density-based methods require complete basis set extrapolations to eliminate basis set artifacts from performance assessments [4]. Correlation-consistent basis sets (cc-pVXZ) with systematic improvement provide a structured approach for this extrapolation.

Finite-Size Effects: For extended systems, finite-size scaling analysis is essential, particularly for methods employing periodic boundary conditions [3]. Twisted boundary conditions and specialized k-point meshes help mitigate finite-size errors in spectroscopic properties.

Approximation Hierarchies: Methods are evaluated across their natural approximation hierarchies: in coupled-cluster theory through the sequence CCSD → CCSD(T) → CCSDT; in many-body perturbation theory through the ladder of approximations from GW to GF2 and beyond; and in DFT through the Jacob's ladder of density functionals [4] [6].

Future Directions and Emerging Approaches

The rapidly evolving landscape of quantum many-body simulations includes several promising directions that may transcend the traditional wavefunction versus density dichotomy:

Machine Learning Augmentations: Machine learning techniques are being integrated into both methodological families, from neural network quantum states for wavefunction parameterization to machine-learned density functionals [4]. These approaches leverage pattern recognition to capture complex correlation effects that challenge traditional approximations [5].

Quantum Computing Algorithms: Quantum algorithms for electronic structure problems, such as variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) and quantum phase estimation, offer the potential for exact solution of the Schrödinger equation on fault-tolerant quantum computers, potentially revolutionizing the field in the long term [5].

Multi-scale Methodologies: Hybrid approaches that combine different methodologies across scales are becoming increasingly sophisticated, such as embedding high-level wavefunction methods within DFT environments or combining non-equilibrium Green's functions with classical molecular dynamics [6].

Information-Theoretic Frameworks: Concepts from quantum information theory, including entanglement spectra, operator space entanglement, and complexity measures, are providing new insights into the fundamental limitations of approximate methods and guiding the development of more efficient representations of quantum states [8].

The continued development of both wavefunction-based and density-based methods remains essential for advancing our ability to solve the quantum many-body problem across different regimes of correlation, system size, and dynamical conditions. Rather than a competition between paradigms, the most productive path forward appears to be their thoughtful integration, leveraging the respective strengths of each approach to address the exponentially complex challenge posed by the Schrödinger equation for many-particle systems.

Understanding electron correlation—the subtle interactions between electrons that cannot be described by mean-field approximations—represents a central challenge in computational chemistry and materials science. This comprehensive guide examines how wavefunction-based methods model electron correlation through increasingly complex mathematical representations of the many-electron wavefunction, contrasting their capabilities with the more computationally efficient density-based methods. The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their treatment of the electronic structure: wavefunction-based methods explicitly describe the positions of electrons through multi-configurational expansions, while density-based methods utilize electron density as the fundamental variable, offering different trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost.

As computational demands grow across fields ranging from drug discovery to materials design, researchers face critical decisions in selecting appropriate quantum chemical methods. Wavefunction-based approaches like coupled cluster theory provide high accuracy for molecular systems but scale poorly with system size, creating practical limitations for biological applications. Density-based methods like density functional theory (DFT) offer better computational efficiency but struggle with certain electronic phenomena such as strong correlation and van der Waals interactions. Recent methodological advances, including hybrid approaches and quantum computing integrations, are progressively blurring the boundaries between these paradigms while expanding their collective applicability.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Approaches

Wavefunction-Based Electron Correlation Methods

Wavefunction-based methods constitute a hierarchy of approaches that systematically improve upon the Hartree-Fock approximation by introducing explicit descriptions of electron correlation. These methods expand the many-electron wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants, with increasing accuracy achieved through more complete inclusion of excited configurations. The coupled cluster (CC) method, particularly with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)), is often regarded as the "gold standard" in quantum chemistry for its exceptional accuracy in predicting molecular properties and interaction energies [9]. This method employs an exponential ansatz of cluster operators to model electron correlation effects, providing results that often approach chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol of experimental values).

For systems requiring multiconfigurational descriptions, multiconfigurational self-consistent field (MCSCF) methods offer a robust framework, particularly for bond-breaking processes and excited states. The multiconfiguration pair-density functional theory (MC-PDFT) represents a recent hybrid advancement that combines the strengths of wavefunction and density-based approaches [10]. MC-PDFT calculates the total energy by splitting it into classical energy components obtained from a multiconfigurational wavefunction and nonclassical energy components approximated using a density functional based on electron density and on-top pair density. The newly developed MC23 functional incorporates kinetic energy density to enable more accurate description of electron correlation, particularly for challenging systems like transition metal complexes [10].

For periodic systems, many-body perturbation theory in the GW approximation has emerged as a powerful approach for calculating electronic band structures [11]. This method addresses the limitations of DFT in describing quasiparticle excitations by computing electron self-energies from the single-particle Green's function (G) and the screened Coulomb interaction (W). Different GW flavors offer varying balances between accuracy and computational cost, with quasiparticle self-consistent GW with vertex corrections (QSGŴ) providing exceptional accuracy for band gap predictions in solids [11].

Density-Based Methods and Their Limitations

Density functional theory has become the workhorse of computational materials science and biochemistry due to its favorable scaling and reasonable accuracy across diverse chemical systems. The Kohn-Sham formulation of DFT revolutionized quantum simulations by providing a practical framework that balances accuracy and computational efficiency [10]. Modern DFT employs increasingly sophisticated exchange-correlation functionals, progressing through "Jacob's Ladder" from local density approximations to meta-generalized gradient approximations and hybrid functionals that incorporate exact exchange mixing.

Despite its widespread success, DFT faces fundamental limitations in systems with strong electron correlation, multiconfigurational character, and van der Waals interactions. Traditional functionals struggle with transition metal complexes, bond-breaking processes, molecules with near-degenerate electronic states, and magnetic systems [10]. The band gap problem in solids represents another significant challenge, where DFT systematically underestimates band gaps due to the inherent limitations of Kohn-Sham eigenvalues in describing fundamental gaps [11]. While advanced functionals like mBJ and HSE06 can reduce this underestimation, such improvements often stem from semi-empirical adjustments rather than rigorous theoretical foundations [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Accuracy Benchmarks Across Chemical Systems

Table 1: Accuracy Comparison of Quantum Chemistry Methods for Molecular Systems

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Accuracy for Halogen-π Interactions (RMSD vs CCSD(T)) | Computational Scaling | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCSD(T) | Wavefunction | Reference (0.0 kJ/mol) | O(N⁷) | Benchmark calculations |

| MP2/TZVPP | Wavefunction | ~1.5 kJ/mol [9] | O(N⁵) | Non-covalent interactions |

| MC-PDFT(MC23) | Hybrid | Comparable to advanced DFT [10] | O(N⁴-N⁵) | Multiconfigurational systems |

| HSE06 | Density | Varies (5-30% error band gaps) [11] | O(N³-N⁴) | Solids, band structures |

| mBJ | Density | Varies (10-35% error band gaps) [11] | O(N³) | Solid-state properties |

For molecular systems requiring high accuracy in non-covalent interactions, wavefunction-based methods demonstrate superior performance. In benchmark studies of halogen-π interactions—critical in drug design and molecular recognition—MP2 with TZVPP basis sets provides excellent agreement with CCSD(T) reference data while maintaining reasonable computational efficiency [9]. This balance makes it suitable for generating large, reliable datasets for machine learning applications in medicinal chemistry. The high accuracy of wavefunction methods stems from their systematic treatment of electron correlation through well-defined excitation hierarchies, though this comes at significantly increased computational cost compared to density-based approaches.

For systems with strong static correlation, the MC-PDFT method represents a significant advancement, achieving accuracy comparable to advanced wavefunction methods at substantially lower computational cost [10]. The recently developed MC23 functional further improves performance for spin splitting, bond energies, and multiconfigurational systems compared to previous MC-PDFT and Kohn-Sham DFT functionals [10]. This hybrid approach effectively addresses one of the most persistent challenges in density-based methods while retaining much of their computational efficiency.

Table 2: Band Gap Prediction Accuracy for Solids (472 Materials Benchmark)

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Mean Absolute Error (eV) | Systematic Error Trend | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSGŴ | Wavefunction (MBPT) | Smallest [11] | Minimal systematic bias | Very High |

| QSGW | Wavefunction (MBPT) | Moderate [11] | ~15% overestimation | High |

| QP G₀W₀ (full-frequency) | Wavefunction (MBPT) | Moderate [11] | Small systematic error | Medium-High |

| G₀W₀-PPA | Wavefunction (MBPT) | Moderate [11] | Varies with starting point | Medium |

| HSE06 | Density (Hybrid DFT) | Larger than QSGŴ [11] | Underestimation | Medium |

| mBJ | Density (meta-GGA DFT) | Larger than QSGŴ [11] | Underestimation | Medium-Low |

Performance for Solid-State Systems

In condensed matter physics, predicting band gaps of semiconductors and insulators represents a critical test for electronic structure methods. Large-scale benchmarking across 472 non-magnetic materials reveals that many-body perturbation theory in the GW approximation significantly outperforms the best density-based functionals for band gap prediction [11]. The most advanced wavefunction-based methods, particularly quasiparticle self-consistent GW with vertex corrections (QSGŴ), achieve exceptional accuracy that can even identify questionable experimental measurements [11].

The benchmark study demonstrates a clear hierarchy in methodological accuracy: simpler G₀W₀ calculations using plasmon-pole approximations offer only marginal improvements over the best DFT functionals, while full-frequency implementations and self-consistent schemes provide dramatically better accuracy [11]. Importantly, self-consistent GW approaches effectively eliminate starting-point bias—the dependence on initial DFT calculations—but systematically overestimate experimental gaps by approximately 15%. Incorporating vertex corrections in the screened Coulomb interaction (QSGŴ) essentially eliminates this overestimation, producing the most accurate band gaps across diverse materials [11].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

FreeQuantum Pipeline for Binding Energy Calculations

An international research team has developed FreeQuantum, a comprehensive computational pipeline that integrates wavefunction-based correlation methods into binding energy calculations for biochemical systems [12]. This framework combines machine learning, classical simulation, and high-accuracy quantum chemistry in a modular system designed to eventually incorporate quantum computing for computationally intensive subproblems.

Figure 1: FreeQuantum workflow for binding energy calculations

The protocol begins with classical molecular dynamics simulations using standard force fields to sample structural configurations of the molecular system [12]. A subset of these configurations undergoes refinement using hybrid quantum/classical methods, progressing from DFT-based calculations to wavefunction-based techniques like NEVPT2 and coupled cluster theory for higher accuracy. These results train machine learning potentials at multiple levels, ultimately enabling binding free energy predictions with quantum-level accuracy [12].

When tested on a ruthenium-based anticancer drug (NKP-1339) binding to its protein target GRP78, the FreeQuantum pipeline predicted a binding free energy of −11.3 ± 2.9 kJ/mol, substantially different from the −19.1 kJ/mol predicted by classical force fields [12]. This discrepancy highlights the critical importance of accurate electron correlation treatment in biochemical simulations, where even small energy differences can determine drug efficacy.

Benchmarking Protocol for Halogen-π Interactions

The benchmarking of quantum methods for halogen-π interactions follows a rigorous protocol to identify optimal methods for high-throughput data generation [9]. The study systematically evaluates multiple combinations of quantum mechanical methods and basis sets, assessing both accuracy relative to CCSD(T)/CBS reference calculations and computational efficiency.

Figure 2: Method benchmarking workflow for molecular interactions

The protocol employs CCSD(T) with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation as the reference method, representing the most reliable accuracy standard for molecular interactions [9]. Tested methods include various density functionals and wavefunction-based approaches like MP2 with different basis sets. Performance evaluation quantifies both accuracy through root-mean-square deviations from reference data and computational efficiency through timing studies [9]. This comprehensive assessment identified MP2 with TZVPP basis sets as optimal for balancing accuracy and efficiency in high-throughput applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Electron Correlation Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | Quantum ESPRESSO [11], Yambo [11], Questaal [11] | Implement advanced electronic structure methods | Solid-state calculations, GW methods |

| Wavefunction Codes | CFOUR, MRCC, ORCA, BAGEL | High-level wavefunction calculations | Molecular systems, coupled cluster |

| Hybrid Method Implementations | FreeQuantum [12], MC-PDFT codes [10] | Combine multiple methodological approaches | Biochemical binding, multiconfigurational systems |

| Benchmark Databases | Borlido et al. dataset [11], Halogen-π benchmarks [9] | Provide reference data for method validation | Method development, accuracy assessment |

| Basis Sets | TZVPP [9], CBS limits, correlation-consistent basis sets | Define mathematical basis for wavefunction expansion | Molecular calculations, benchmark studies |

Computational Resource Requirements

The computational demands of wavefunction-based electron correlation methods vary dramatically across the methodological spectrum. Second-order Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) scales as O(N⁵) with system size, making it applicable to medium-sized molecular systems but challenging for extended systems [9]. Coupled cluster methods with full treatment of single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) scale as O(N⁷), restricting their application to small molecules but providing exceptional accuracy [9].

For solid-state systems, GW calculations exhibit varying computational costs depending on the specific implementation. Simple G₀W₀ calculations using plasmon-pole approximations offer reasonable computational requirements, while full-frequency implementations and self-consistent schemes demand significantly greater resources [11]. The most accurate QSGŴ methods with vertex corrections remain computationally intensive but provide exceptional accuracy for band structure predictions [11].

The emerging FreeQuantum pipeline demonstrates how strategic integration of computational methods can optimize resource utilization [12]. By employing high-accuracy wavefunction methods only for critical subsystems and leveraging machine learning for generalization, this approach achieves quantum-level accuracy while maintaining computational feasibility for biologically relevant systems.

Future Directions and Emerging Paradigms

Quantum Computing Integration

The FreeQuantum pipeline represents a groundbreaking approach to preparing for quantum advantage in biochemical simulations [12]. This framework is explicitly designed to incorporate quantum computing resources for the most computationally challenging subproblems once fault-tolerant quantum hardware becomes available. Resource estimates suggest that a fully fault-tolerant quantum computer with approximately 1,000 logical qubits could compute the required energy data within practical timeframes—potentially enabling full binding energy simulations within 24 hours for systems that are currently intractable [12].

The quantum-ready architecture employs quantum phase estimation (QPE) algorithms with techniques like Trotterization and qubitization to compute electronic energies for chemically important subregions [12]. These quantum-computed energies would then train machine learning models within the larger classical simulation framework, creating a hybrid quantum-classical workflow that maximizes the strengths of both computational paradigms.

Methodological Hybridization and Machine Learning

The boundaries between wavefunction and density-based methods are increasingly blurring through methodological hybridization. Approaches like MC-PDFT combine multiconfigurational wavefunctions with density functional components, achieving high accuracy for challenging systems without prohibitive computational cost [10]. These hybrid methods effectively address the strong correlation problem that plagues conventional DFT while avoiding the steep scaling of pure wavefunction approaches.

Machine learning is revolutionizing electron correlation studies through multiple pathways. The FreeQuantum pipeline employs ML potentials trained on high-accuracy quantum chemistry data to generalize quantum-mechanical accuracy across larger systems [12]. In materials science, machine learning models trained on advanced GW calculations offer promising alternatives to direct simulation, though their reliability depends critically on the quality of training data [11]. The systematic benchmarking of wavefunction and density-based methods provides essential guidance for generating high-fidelity datasets for machine learning applications across chemical and materials spaces.

Addressing Current Limitations and Challenges

Despite significant advances, substantial challenges remain in electron correlation methodology. Traditional wavefunction methods still struggle with systems exhibiting extensive dynamic correlation or very large quantum cores [12]. Quantum computing, while promising, likely remains years away from achieving the scale and fidelity required for routine applications in drug discovery and materials design [12].

The targeted deployment of high-level methods represents a pragmatic path forward. Rather than pursuing quantum supremacy across entire molecular systems, approaches like FreeQuantum employ advanced correlation methods surgically where classical approaches fail [12]. This strategy acknowledges the continuing value of established computational methods while progressively extending the boundaries of quantum mechanical accuracy to increasingly complex and biologically relevant systems.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a foundational pillar in computational quantum mechanics, enabling the investigation of electronic structure in atoms, molecules, and condensed phases. Its versatility makes it a dominant method across physics, chemistry, and materials science. [13] The core of DFT's appeal lies in its use of the electron density—a function of only three spatial coordinates—as the fundamental variable, in stark contrast to the many-body wavefunction, which depends on 3N variables for an N-electron system. [13] [14] This drastic simplification is formally justified by the Hohenberg-Kohn (HK) theorems, which established the theoretical bedrock upon which all modern DFT developments are built. [13]

This guide objectively situates DFT within the broader landscape of quantum chemical methods, primarily comparing it with traditional wavefunction-based approaches. We will dissect the theoretical underpinnings, performance metrics, and practical considerations, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting the appropriate computational tool for specific applications, particularly in fields like drug development where predicting molecular behavior is critical.

Theoretical Foundations: The Hohenberg-Kohn Theorems

The 1964 work of Walter Kohn and Pierre Hohenberg provided the rigorous justification for using electron density as the sole determinant of a system's properties. [14] The two Hohenberg-Kohn theorems can be summarized as follows:

The First Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the external potential (e.g., the potential created by the nuclei) acting on a system and its ground-state electron density, ( n(\mathbf{r}) ). [13] A direct consequence is that the ground-state density uniquely determines all properties of the system, including the total energy and the wavefunction itself. [13] [14] This reduces the complex many-body problem of N interacting electrons to a problem involving just three spatial coordinates.

The Second Hohenberg-Kohn Theorem provides the variational principle for the energy functional. It defines a universal energy functional, ( E[n] ), whose minimum value, obtained by varying over all valid ground-state densities, is the exact ground-state energy. The density that minimizes this functional is the exact ground-state density, ( n_0(\mathbf{r}) ). [13]

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and profound implications of these theorems for simplifying quantum mechanical calculations.

While the HK theorems prove the existence of a universal functional, they do not specify its exact form. [14] This was addressed by the subsequent Kohn-Sham formulation, which introduced a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that has the same density as the real, interacting system. [13] This ingenious approach maps the intractable problem of interacting electrons onto a tractable one-electron problem, with all the complexities of electron interactions buried in the exchange-correlation functional. The accuracy of a DFT calculation thus hinges entirely on the quality of the approximation used for this unknown functional. [13] [14]

Comparative Analysis: DFT vs. Wavefunction-Based Methods

The choice between density-based (DFT) and wavefunction-based methods involves a fundamental trade-off between computational cost and accuracy, guided by the specific needs of the research problem.

Methodological Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between DFT and wavefunction-based methods.

| Feature | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Wavefunction-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Variable | Electron density, ( n(\mathbf{r}) ) (3 variables) | Many-electron wavefunction, ( \Psi(\mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, ..., \mathbf{r}_N) ) (3N variables) |

| Theoretical Basis | Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, Kohn-Sham equations | Variational principle, Hartree-Fock theory |

| Treatment of Electron Correlation | Approximate, via the exchange-correlation functional | Can be treated systematically and exactly (in principle) |

| Computational Scaling | Favorable (typically ( N^3 ) to ( N^4 )), suitable for large systems (100s of atoms) | Unfavorable (e.g., CCSD(T) scales as ( N^7 )), limited to smaller systems |

| Key Unknown | Exact form of the exchange-correlation functional | Need for infinite basis set and complete correlation treatment |

Performance Benchmarking Across Molecular Properties

The theoretical differences manifest distinctly in practical calculations. The performance of these methods varies significantly across different molecular properties, as benchmarked against experimental data or highly accurate theoretical results.

Table 2: Performance comparison for key molecular properties. [14]

| Property | DFT Performance | Wavefunction-Based Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometries | Excellent, often within 2-5 pm of experiment. GGA functionals are efficient and reliable. [14] | Good, but requires high levels of theory (e.g., CCSD(T)) with large basis sets for comparable accuracy. | DFT geometries converge quickly with basis set size. |

| Reaction Energies | Variable; highly dependent on the functional. Can show large errors (10s of kcal/mol) for certain systems. [15] | High accuracy possible with methods like CCSD(T), often considered the "gold standard". | DFT is unreliable for strongly correlated systems, anions, and dispersion-dominated interactions. [13] [15] |

| Spectroscopic Properties | Good for a wide range (IR, optical, XAS, EPR parameters). [14] | Can be very accurate but often prohibitively expensive for large systems, especially those with transition metals. | DFT is invaluable for interpreting spectra of bioinorganic systems. [14] |

| Weak Interactions | Poor with standard functionals; requires empirical dispersion corrections. [13] [14] | Good performance with methods like CCSD(T) or MP2, but size of system is a limitation. | A key weakness of standard DFT approximations. [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Computational Workflows

Implementing these methods requires careful attention to computational protocols. The workflow for a typical DFT study, and its comparison to a high-level wavefunction-based approach, can be visualized as follows.

Detailed DFT Protocol for Geometry Optimization and Energy Calculation

The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for a DFT calculation, as might be used to study a drug-like molecule or a catalytic site. [14]

System Preparation and Initial Coordinates: Obtain a reasonable initial geometry from crystallographic databases (e.g., Cambridge Structural Database), molecular building software, or a lower-level of theory calculation.

Functional and Basis Set Selection:

- Functional: For general-purpose use on organic molecules or transition metal complexes, a hybrid functional like B3LYP is a common starting point. However, modern meta-GGA (e.g., TPSSh) or range-separated hybrid functionals may offer better performance for specific properties. It is critical to test multiple functionals to gauge the sensitivity of the results. [15] [14]

- Basis Set: A valence triple-zeta basis set with polarization functions (e.g., def2-TZVP) is recommended for good accuracy. Pople-style basis sets (e.g., 6-31G*) are historically common but are considered less robust for publication-level work today. [15]

Geometry Optimization: The molecular structure is iteratively refined to find the nearest local minimum on the potential energy surface. Key considerations include:

- Convergence Criteria: Tightening the default thresholds for energy change, force, and displacement to ensure a fully optimized geometry.

- Grid Accuracy: Using a finer integration grid (e.g., "UltraFine" in Gaussian) is crucial for achieving rotational invariance and accuracy, especially for meta-GGA functionals or property calculations like NMR. [15]

Property Calculation: Once an optimized geometry is obtained, single-point energy calculations or specific property calculations (e.g., vibrational frequencies, UV-Vis spectra, NMR chemical shifts) are performed. This step may use a higher-level functional or a larger basis set than the optimization.

Result Analysis and Validation: Analyze the results to compute reaction energies, barrier heights, or spectroscopic parameters. Where possible, results should be validated against experimental data or higher-level ab initio calculations on a smaller model system. [15]

Protocol for High-Level Wavefunction-Based Benchmarking

When high accuracy is required for energies, a protocol using the "gold standard" CCSD(T) method can be employed:

- Geometry: Use a geometry optimized at a reliable DFT level (e.g., with a hybrid functional and a triple-zeta basis set).

- Single-Point Energy: Perform a CCSD(T) energy calculation on this geometry using a correlation-consistent basis set (e.g., cc-pVTZ).

- Basis Set Extrapolation: To approach the complete basis set (CBS) limit, perform calculations with a series of increasingly large basis sets (e.g., cc-pVDZ, cc-pVTZ, cc-pVQZ) and extrapolate.

- Error Analysis: Compare the CCSD(T) results with those from various DFT functionals to assess the accuracy of the DFT methods for the system at hand.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

In computational chemistry, the "reagents" are the software, functionals, and basis sets used to perform the calculations.

Table 3: Key research reagents in computational quantum chemistry.

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| B3LYP | DFT Functional (Hybrid) | A historically dominant functional; good for organic molecules and transition metal complexes, but can produce large errors for reaction energies and is not recommended as the sole functional for research. [15] [14] |

| PBE, BP86 | DFT Functional (GGA) | Efficient and often excellent for geometry optimizations, especially in solid-state physics. Less accurate for energies. [14] |

| def2-TZVP | Basis Set | A valence triple-zeta basis set with polarization, considered a robust standard for accurate molecular calculations. [15] |

| CCSD(T) | Wavefunction Method | The "gold standard" for quantum chemistry, providing highly accurate energies for small to medium-sized molecules. Used for benchmarking. [15] |

| Dispersion Correction | Add-on for DFT | Empirical corrections (e.g., DFT-D3) that must be added to most functionals to accurately model van der Waals forces. [13] [14] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The field of DFT is far from static, with active research aimed at overcoming its fundamental limitations.

Machine-Learning Assisted Functionals: Recent advances involve training machine learning (ML) models on high-quality quantum many-body data to discover more universal exchange-correlation functionals. A 2025 study demonstrated that training on both energies and potentials leads to highly accurate functionals that generalize well beyond their training set, bridging the accuracy gap between DFT and more expensive methods while keeping computational costs low. [16]

Beyond the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: New formulations of time-dependent DFT are being developed to handle the coupled dynamics of electrons and nuclei beyond the static Born-Oppenheimer approximation. This is crucial for accurately modeling photochemical processes and nonadiabatic phenomena like conical intersections. [17]

Addressing Strong Correlation: The development of functionals for strongly correlated systems (e.g., those with transition metals or frustrated magnetic interactions) remains a major challenge. Approaches like density-corrected DFT and double-hybrid functionals, which incorporate a fraction of nonlocal perturbation theory, are promising areas of development. [13] [14]

Density Functional Theory, grounded by the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, offers an powerful and efficient computational framework that is unparalleled for studying the electronic structure of large and complex systems. Its primary advantage over wavefunction-based methods is its superior computational scalability. However, this efficiency comes at the cost of inherent, and sometimes unpredictable, inaccuracies due to the approximate nature of the exchange-correlation functional.

The choice between DFT and wavefunction-based methods is not a matter of declaring a universal winner but of selecting the right tool for the problem. For geometry optimizations and screening studies of large systems, including those relevant to drug discovery (e.g., protein-ligand interactions), DFT is an indispensable workhorse. For achieving high quantitative accuracy in reaction energies or for modeling systems with strong electron correlation, high-level wavefunction-based methods like CCSD(T) remain the benchmark, despite their cost. A robust research strategy often involves using both paradigms in a complementary fashion, leveraging the strengths of each to validate findings and push the boundaries of computational prediction.

Quantum mechanical modeling of molecular systems is a foundational tool in modern chemical research and drug discovery, enabling scientists to predict molecular structure, reactivity, and interactions with unprecedented accuracy [18]. The inherent complexity of solving the Schrödinger equation for multi-particle systems necessitates strategic approximations that make computations tractable while preserving physical realism [19]. Two such foundational approximations are the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) principle, which separates electronic and nuclear motion, and the use of basis sets, which provide a mathematical framework for describing electron distribution [20] [19]. These approximations form the cornerstone upon which both wavefunction-based and density-based quantum chemical methods are built, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and domains of applicability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key approximations within the context of modern quantum chemical research, with particular emphasis on their implementation across methodological divides and their critical role in drug discovery applications.

Theoretical Foundation: The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Conceptual Framework and Mathematical Basis

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation addresses the fundamental challenge of coupled electron-nuclear dynamics in molecular systems. As articulated in the seminal work of Born and Oppenheimer, this approximation exploits the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei, which causes nuclei to move on timescales that are orders of magnitude slower than electronic motion [20]. This separation permits the molecular wavefunction to be factorized into distinct nuclear and electronic components. Formally, the approximation leads to an electronic Schrödinger equation that is solved for a fixed nuclear configuration:

$$ \hat{H}e \psie(r; R) = Ee(R) \psie(r; R) $$

where $\hat{H}e$ is the electronic Hamiltonian, $\psie$ is the electronic wavefunction, $r$ and $R$ represent electron and nuclear coordinates respectively, and $E_e(R)$ is the potential energy surface governing nuclear motion [18]. This separation creates a hierarchy in electron-nuclear interactions, effectively allowing chemists to visualize molecules as nuclei connected by electrons that generate a potential governing nuclear behavior [20].

Contrary to common misconceptions, the BO approximation does not require nuclei to be frozen or treated classically [20]. Rather, it enables the calculation of a potential energy surface on which nuclei can move quantum mechanically, though this surface is often subsequently used in classical molecular dynamics simulations. The approximation breaks down in specific chemical phenomena such as conical intersections, photochemical processes, and systems involving light atoms (especially hydrogen), where non-Born-Oppenheimer effects become significant [20] [21] [17].

Methodological Implementation Across Quantum Chemical Methods

The BO approximation serves as the starting point for virtually all practical quantum chemical methods, though its implementation manifests differently across the methodological spectrum.

In wavefunction-based methods like Hartree-Fock (HF) and post-HF approaches, the BO approximation allows for the solution of the electronic wavefunction for fixed nuclear positions through the self-consistent field procedure [18] [19]. The nuclear coordinates appear as parameters in the electronic Hamiltonian, and the resulting energy $E_e(R)$ facilitates geometry optimization and transition state location.

Density-based methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) similarly rely on the BO framework, with the electron density $\rho(r)$ being determined for each nuclear configuration [18] [19]. The Kohn-Sham equations, which are solved self-consistently, depend parametrically on nuclear positions through the external potential [18].

For advanced molecular dynamics simulations, Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) utilizes the BO approximation by recalculating the electronic structure at each time step, enabling accurate modeling of chemical reactions and liquid-phase properties [22].

The following workflow illustrates how the Born-Oppenheimer approximation is operationalized in typical quantum chemical calculations:

Basis Sets: Mathematical Representation of Electronic Structure

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

Basis sets provide the mathematical foundation for representing the spatial distribution of electrons in molecular systems [19]. In practical implementations, molecular orbitals ($\phii$) are constructed as linear combinations of atom-centered basis functions ($\chi\mu$), an approach known as the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals:

$$ \phii(1) = \sum{\mu} c{\mu i} \chi\mu(1) $$

The choice of basis set involves critical tradeoffs between computational cost and accuracy, with more complete basis sets providing better resolution of electron distribution at increased computational expense [19]. Standard basis set classifications include:

- Minimal/single-zeta: Contain the minimum number of basis functions required for each atom

- Double-zeta: Include twice as many basis functions as minimal sets

- Triple-zeta: Provide three times the minimal number for higher accuracy

- Polarized: Add higher angular momentum functions to better describe electron distortion

- Diffuse: Include spatially extended functions for accurate treatment of anions and weak interactions

The computational cost of quantum chemical calculations scales dramatically with basis set size. For a system with N basis functions, the number of electron repulsion integrals that must be computed scales approximately as $N^4$, making method selection a crucial consideration in research planning [19].

Basis Set Implementation in Wavefunction vs. Density Methods

While both methodological families employ similar basis set formulations, their computational demands and accuracy implications differ significantly, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Basis Set Implementation in Wavefunction vs. Density-Based Methods

| Aspect | Wavefunction Methods (HF, MP2, CCSD(T)) | Density Methods (DFT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Molecular orbitals $\phi_i$ | Electron density $\rho(r)$ |

| Integral Computation | Required for 1- and 2-electron integrals | Required for Kohn-Sham potential |

| Basis Set Sensitivity | High - particularly for electron correlation | Moderate - depends on functional |

| Typical Applications | High-accuracy thermochemistry, spectroscopy | Medium-large systems, material properties |

| Cost Scaling with Basis | $O(N^4)$ for HF to $O(N^7)$ for CCSD(T) | $O(N^3)$ to $O(N^4)$ |

The relationship between basis set quality, methodological approach, and computational cost creates a complex optimization landscape for researchers, illustrated below:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Methodological Benchmarks Across Chemical Systems

The performance characteristics of quantum chemical methods employing the BO approximation and basis sets vary significantly across different chemical systems and target properties. The table below summarizes key benchmarking data for methods relevant to drug discovery applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Quantum Chemical Methods in Drug Discovery [18]

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Optimal System Size | Computational Scaling | Basis Set Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Fast convergence; reliable baseline; well-established theory | Neglects electron correlation; poor for weak interactions | ~100 atoms | $O(N^4)$ | High |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Good accuracy for ground states; handles electron correlation; wide applicability | Functional dependence; delocalization error; expensive for large systems | ~500 atoms | $O(N^3)$ | Moderate |

| QM/MM | Combines QM accuracy with MM efficiency; handles large biomolecules | Complex boundary definitions; method-dependent accuracy | ~10,000 atoms | $O(N^3)$ for QM region | Moderate |

| Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) | Scalable to large systems; detailed interaction analysis | Fragmentation complexity; approximates long-range effects | Thousands of atoms | $O(N^2)$ | Moderate-High |

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery

Quantum chemical methods leveraging these approximations provide critical insights for drug discovery, including binding affinity prediction, reaction mechanism elucidation, and spectroscopic property calculation [18]. Specific applications include:

- Kinase inhibitor design: DFT calculations provide accurate molecular orbitals and electronic properties for optimizing binding interactions [18]

- Metalloenzyme inhibition: QM/MM approaches enable modeling of transition metal active sites within protein environments [18]

- Covalent inhibitor development: Potential energy surface scans along reaction coordinates predict reactivity and selectivity [18]

- Fragment-based drug design: DFT evaluates fragment binding energies and interaction patterns [18]

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol 1: Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics of Liquid H₂S

This protocol exemplifies the application of the BO approximation in molecular dynamics simulations with a non-local density functional [22].

Objective: To investigate the structure, dynamics, and electronic properties of liquid hydrogen sulfide using Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics.

Methodology:

- Functional Selection: Employ the VV10 (Vydrov and Van Voorhis) exchange-correlation functional including non-local correlation for dispersion interactions

- Basis Set: Utilize a polarized triple-zeta basis set for balanced accuracy and computational efficiency

- System Preparation: Initialize 64 H₂S molecules in a cubic simulation box with periodic boundary conditions at experimental density

- Dynamics Protocol:

- Temperature control: Nosé-Hoover thermostat at 200K

- Time step: 0.5 fs for numerical integration

- Total simulation time: 50 ps after equilibration

- Analysis Metrics:

- Radial distribution functions for structural characterization

- Dipole moment distributions to quantify polarization effects

- Electronic absorption spectra via time-dependent DFT

- Exciton binding energy calculations

Key Findings: The VV10 functional accurately predicted the (H₂S)₂ dimer binding energy versus experiment. Liquid H₂S showed a 0.2D dipole moment increase versus gas phase, with significantly smaller polarization effects than water. The first absorption peak shifted minimally (~0.1 eV) compared to substantial blue shifts in liquid water [22].

Protocol 2: Hamiltonian Matrix Prediction with Machine Learning

This innovative protocol from recent literature demonstrates how machine learning can leverage the BO approximation and basis set concepts for accelerated electronic structure prediction [23].

Objective: To predict Hamiltonian matrices directly from atomic structures using equivariant graph neural networks, enabling rapid property calculation.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation: "OMolCSH58k" dataset with 58 elements, molecules up to 150 atoms, and def2-TZVPD basis set

- Architecture: HELM ("Hamiltonian-trained Electronic-structure Learning for Molecules") model with symmetry-constrained graph neural networks

- Representation: Decompose Hamiltonian submatrices between atomic orbitals of angular momentum l₁ and l₂ into irreducible representations using Clebsch-Gordan coefficients

- Training: Hamiltonian pretraining on diverse molecular structures followed by fine-tuning for energy prediction

- Validation: Benchmark against DFT calculations for energy and property prediction

Key Findings: Hamiltonian pretraining provided rich atomic environment representations, yielding 2× improvement in energy prediction accuracy in low-data regimes compared to training on energies alone [23].

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Resources for Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Tool | Category | Primary Function | Methodological Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | Electronic Structure Package | General-purpose quantum chemistry | HF, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T) |

| SIESTA | DFT Code | Periodic pseudopotential calculations | DFT, beyond-BO methods |

| Qiskit | Quantum Computing | Quantum algorithm development | Hybrid quantum-classical methods |

| AMBER/CHARMM | Molecular Mechanics | Force field-based simulations | QM/MM interface |

| def2-TZVPD | Basis Set | Balanced accuracy for main group elements | Wavefunction and DFT methods |

Emerging Directions and Future Outlook

The continuing evolution of quantum chemical methodologies addresses limitations in both the BO approximation and basis set representations. Promising directions include:

- Beyond-BO DFT: New formulations that treat electron-nuclear correlations explicitly while maintaining computational tractability [21] [17]

- Machine-Learned Interatomic Potentials: Hamiltonian matrix prediction models that bypass explicit SCF calculations while maintaining quantum accuracy [23]

- Quantum Computing: Hybrid algorithms that leverage quantum processing for electron correlation problems intractable to classical computation [18]

- Universal MLIPs: Machine learning potentials trained on diverse datasets spanning chemical space for transferable accuracy [23]

These advances aim to expand the accessible chemical space while improving accuracy for challenging systems such as conical intersections, charge transfer states, and systems with strong electron-phonon coupling [17].

Bridging Quantum Physics and Pharmaceutical Application

The accurate simulation of molecules is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict the behavior, efficacy, and safety of potential therapeutic compounds before costly laboratory synthesis. In computational chemistry, two primary families of quantum mechanical methods have emerged: wavefunction-based theories and density-based theories, known as Density Functional Theory (DFT). Wavefunction-based methods, such as Configuration Interaction (CI) and coupled-cluster theory, explicitly describe the complex many-body interactions of electrons by solving the Schrödinger equation for a system's wavefunction. In contrast, DFT dramatically simplifies the problem by using the electron density as the fundamental variable, making it computationally more efficient but reliant on approximations for the exchange-correlation energy [24].

The pharmaceutical industry faces a critical trade-off: wavefunction methods offer high accuracy for challenging systems like transition metal complexes but are often prohibitively expensive for large biological molecules. DFT provides the scalability needed for drug-sized systems but can struggle with accuracy in cases involving significant electron correlation, such as bond-breaking, excited states, and interactions with transition metals—precisely the scenarios common in drug-target interactions [10] [24]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these methodologies, equipping researchers with the data and protocols needed to select the optimal tool for their specific pharmaceutical challenges.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Developments

The Fundamentals of Density Functional Theory (DFT)

DFT is founded on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which establish that the ground-state energy of an electron system is uniquely determined by its electron density, ρ(r) [24]. The practical implementation, Kohn-Sham DFT, calculates the total energy through a functional that combines the kinetic energy of non-interacting electrons, the external potential energy, the classical Coulomb energy, and the critical exchange-correlation energy (EXC) [24]. The accuracy of DFT hinges entirely on the approximation used for EXC, whose exact form is unknown. The evolution of these functionals is often visualized as "Jacob's Ladder," climbing from simple to increasingly sophisticated approximations [24].

- Local Density Approximation (LDA): The simplest functional, LDA evaluates the exchange-correlation energy at each point as if the electron density were uniform. It tends to overbind, predicting bond lengths that are too short and binding energies that are too large [24].

- Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): GGA functionals improve upon LDA by incorporating the gradient of the density (∇ρ), accounting for inhomogeneity. Functionals like BLYP and PBE offer better accuracy for molecular geometries but can be unreliable for energetics [24].

- meta-GGA (mGGA): This class includes the kinetic energy density (τ) as an additional ingredient, leading to significantly more accurate energetics. Examples include TPSS and M06-L [24].

- Hybrid Functionals: To address self-interaction error and incorrect asymptotic behavior, hybrid functionals like B3LYP mix a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange. This improves accuracy at a higher computational cost [24].

- Range-Separated Hybrids (RSH): These functionals, such as CAM-B3LYP, use a higher proportion of HF exchange at long range, which is beneficial for modeling charge-transfer excited states, a common scenario in photochemical drug interactions [24].

A recent and significant advancement is Multiconfiguration Pair-Density Functional Theory (MC-PDFT), which hybridizes wavefunction and density-based ideas. MC-PDFT uses a multiconfigurational wavefunction to capture static correlation and then employs a density functional to calculate the energy based on the electron density and the on-top pair density. The newly developed MC23 functional, which incorporates kinetic energy density, has demonstrated high accuracy for complex systems like transition metals and multiconfigurational systems without the steep computational cost of advanced wavefunction methods, positioning it as a potential game-changer for pharmaceutical simulations [10].

The Fundamentals of Wavefunction-Based Theory

Wavefunction-based methods tackle the electronic Schrödinger equation directly. They begin with a Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation, which provides a mean-field description but neglects electron correlation—the instantaneous adjustment of electrons to each other's positions. Post-HF methods systematically recover this correlation.

- Configuration Interaction (CI): CI expands the molecular wavefunction as a linear combination of Slater determinants (configurations) generated by exciting electrons from occupied to unoccupied molecular orbitals. While flexible, traditional CI calculations using HF orbitals can suffer from slow convergence [25].

- CI/DFT Method: An innovative hybrid approach uses molecular orbitals obtained from a DFT calculation as the basis for the CI expansion. This CI/DFT framework leverages the ability of DFT orbitals to account for electron correlation, which can improve the modeling of core- and valence-excited states, particularly in systems with strong electron-correlation effects like CO₂ [25].

- Multi-Reference Methods: For systems where a single determinant is insufficient (e.g., bond-breaking, diradicals), methods like Multi-Configurational Self-Consistent Field (MCSCF) or Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) use multiple reference configurations. While highly accurate, they are computationally expensive and require significant user input to define the active space [25].

- Coupled-Cluster (CC) Theory: Often considered the "gold standard" for single-reference systems, coupled-cluster with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) provides exceptional accuracy but scales very poorly (e.g., N⁷ for CCSD(T)), limiting its application to small molecules [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Quantum Chemical Method Foundations

| Feature | Density-Based Methods (DFT) | Wavefunction-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Quantity | Electron Density, ρ(r) | Many-Electron Wavefunction, Ψ |

| Handles Electron Correlation | Via approximate exchange-correlation functional | Explicitly, via excitations or multi-reference treatments |

| Typical Scaling with System Size | N³ to N⁴ | N⁵ to N⁷+ (e.g., N⁵ for MP2, N⁷ for CCSD(T)) |

| Key Strength | Computational efficiency for large systems | High, systematically improvable accuracy |

| Key Limitation | Accuracy limited by functional choice; can fail for strongly correlated systems | Prohibitive computational cost for large molecules |

Performance Comparison in Pharmaceutical-Relevant Applications

Accuracy and Computational Cost Benchmarking

A critical challenge in pharmaceutical research is selecting a method that provides sufficient accuracy without intractable computational demands. A 2025 benchmark study on halogen-π interactions—pivotal for molecular recognition and drug design—provides a clear quantitative comparison [9]. The study evaluated various methods against the high-accuracy CCSD(T)/CBS reference level.

Table 2: Benchmarking Quantum Methods for Halogen-π Interactions [9]

| Method | Accuracy vs. CCSD(T)/CBS | Computational Efficiency | Suitability for High-Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| MP2/TZVPP | Excellent agreement | High (faster than CCSD(T)) | Highly suitable |

| CCSD(T)/CBS | Reference (Highest Accuracy) | Very Low (Computationally intensive) | Not suitable |

| Various DFT Functionals | Variable; dependent on functional | Very High | Suitable, but accuracy may be insufficient |

The study concluded that MP2 with a TZVPP basis set offers an optimal balance, enabling the generation of large, reliable datasets for training machine-learning models in medicinal chemistry [9]. This highlights a pragmatic approach: using a robust wavefunction method (MP2) for targeted data generation to power more scalable AI and classical models.

For systems beyond the reach of single-reference methods, the choice becomes more complex. The CI/DFT approach has shown promise for modeling core-excited states, which are critical for interpreting X-ray spectroscopy in drug-protein complexes. In molecules with strong electron correlation but weak multi-reference character (e.g., CO₂), CI/DFT can outperform standard CI on HF orbitals and compete with more expensive multi-reference methods [25]. However, for molecules with significant multi-reference character (e.g., N₂), the choice of orbital basis (HF vs. DFT) becomes less relevant, and a proper multi-configurational treatment is essential [25].

Application to Real-World Drug Discovery Problems

The real-world limitations of classical computational methods are driving the exploration of quantum computing for pharmaceutical problems. A prominent example is the FreeQuantum pipeline, a modular framework designed to eventually incorporate quantum computers for calculating molecular binding energies with quantum-level accuracy [12].

In a test case simulating the binding of a ruthenium-based anticancer drug (NKP-1339) to its protein target (GRP78), classical force fields and DFT faced significant challenges due to the ruthenium atom's open-shell electronic structure and multiconfigurational character [12]. The pipeline embedded high-accuracy wavefunction-based methods (like NEVPT2 and coupled cluster theory) within a classical molecular simulation, using machine learning as a bridge. The result was a predicted binding free energy of -11.3 ± 2.9 kJ/mol, a substantial deviation from the -19.1 kJ/mol predicted by classical force fields [12]. A difference of this magnitude (several kJ/mol) can determine the success or failure of a drug candidate, underscoring the critical need for high-accuracy methods for complex pharmaceutical targets involving transition metals.

The MC-PDFT method addresses similar challenges. It is specifically designed for systems where traditional Kohn-Sham DFT fails, such as transition metal complexes, bond-breaking processes, and molecules with near-degenerate electronic states—common in catalysis and photochemistry. The developers report that the new MC23 functional "achieves high accuracy without the steep computational cost of other advanced methods," making it feasible to study larger systems that are prohibitively expensive for traditional wavefunction methods [10].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Binding Free Energy Calculation for a Transition Metal Drug Complex

This protocol is derived from the FreeQuantum pipeline study on the ruthenium-based drug NKP-1339 [12].

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein (GRP78) and the ruthenium-containing ligand (NKP-1339). Parameterize the system using a classical force field, assigning charges and bonding parameters suitable for the transition metal center.

- Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) Sampling: Run classical MD simulations to sample the thermodynamic configurations of the protein-ligand complex in explicit solvent. This generates an ensemble of structural snapshots.

- Configuration Selection and Refinement: Select a representative subset (e.g., hundreds to thousands) of snapshots from the MD trajectory. For these snapshots, define a "quantum core" region encompassing the ligand and key protein residues from the binding pocket.

- High-Accuracy Quantum Chemical Single-Point Calculations: For each selected snapshot's quantum core:

- Perform a geometry refinement using a hybrid quantum/classical (QM/MM) method with a DFT functional.

- Subsequently, compute the electronic energy using a high-level wavefunction-based method such as NEVPT2 or coupled-cluster theory (e.g., CCSD(T)) with a sufficiently large basis set. This step provides the benchmark-quality energy data.

- Machine Learning Potential (MLP) Training: Use the high-accuracy energies from Step 4 to train a machine-learning potential (MLP). This MLP learns the relationship between the structure of the quantum core and its accurate energy.

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Use the trained MLP to evaluate the energies across a much larger set of configurations from the MD simulation. Employ statistical mechanical methods (e.g., free energy perturbation or thermodynamic integration) to compute the final binding free energy.

Diagram 1: FreeEnergy Pipeline Workflow. A hybrid quantum-classical workflow for calculating binding free energies with quantum accuracy [12].

Protocol 2: Modeling Core-Excited States with CI/DFT

This protocol outlines the CI/DFT method for modeling valence and core-excited states, as applied to molecules like CO₂ and N₂ [25].

- Molecular Orbital Generation: Perform a preliminary ground-state DFT calculation for the target molecule. This calculation provides a set of molecular orbitals. The choice of DFT functional (e.g., a GGA or hybrid) and atomic basis set should be appropriate for the system and property of interest.

- Configuration Selection: Define the active space for the CI calculation. This involves selecting a set of occupied and virtual molecular orbitals from the DFT calculation to include in the excitation process. The number of electrons and orbitals in the active space determines the level of theory (e.g., CIS, CISD, CASCI).

- CI Hamiltonian Construction: Construct the Configuration Interaction Hamiltonian matrix. The matrix elements ( H{\mathbf{k},\mathbf{k'}} ) are computed as ( \langle \psi{\mathbf{k}} | \hat{H} | \psi{\mathbf{k'}} \rangle ), where ( | \psi{\mathbf{k}} \rangle ) and ( | \psi_{\mathbf{k'}} \rangle ) are Slater determinants from the configuration basis set, and ( \hat{H} ) is the full molecular Hamiltonian [25].

- Diagonalization and Property Calculation: Diagonalize the CI Hamiltonian matrix to obtain the energies (eigenvalues) and wavefunctions (eigenvectors) for the ground and excited states.

- Analysis: Analyze the resulting states to determine vertical excitation energies, oscillator strengths, and the character of the excitations (e.g., single vs. double excitations).

Diagram 2: CI/DFT Calculation Workflow. A workflow for calculating excited states using a CI expansion on a basis of DFT molecular orbitals [25].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Quantum Pharmaceutical Research

| Tool Name / Category | Type / Function | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|